Page 1

Page 2

Tutorial

There are six commands on the reference card indented one

level under NEW: UP, DOWN, LEFT, RIGHT, PARAGRAPH, and MODE.

They correspond to six of the options on ThinkTank’s NEW Com—

mand menu and they allow you to specify what kind of new

material to add and where. Press N (the command key for NEW)

to display this menu, which is shown in Figure 3—5.

There is a seventh option on the NEW Command Menu ——

ESCAPE —— that’s not listed under NEW on your reference card.

That’s because ThinkTank’s escape valve, which stops whatever

you’re doing, is always an option. It’s listed separately on

the reference card under “Notes.”

You can reach these NEW options only by selecting the NEW

command first. In ThinkTank terminology, these options are

beneath or under NEW; they are one level deeper or subordinate

to NEW in ThinkTank’s command structure. On the reference

card, and in ThinkTank in general, this relationship is expressed by levels of indentation from left to right.

The reference card is a map of ThinkTank

in which one level of indentation corresponds to

one level deeper in the command structure.

Now press N to select the NODE option from the NEW Com-

mand Menu. MODE disappears from the menu but a new option,

EDIT, replaces it as shown in Figure 4—1. The explanation

line reads TEXT EDITOR FOR HEADLINES. On the reference card,

EDIT is indented one level under NODE (which is indented one

level under NEW). In other words, to reach the “headline

editor” from the NEW Command Menu, you must go through NODE

first.

Notice that EDIT appears twice under “Adding Information”

on the reference card, once under MODE and once under

PARAGRAPH. As you can see from the two entries, each EDIT has

a different meaning; EDIT under PARAGRAPH gets you to the TEXT

EDITOR FOR PARAGRAPHS. Some other commands (such as DELETE

and COPY) also have more than one meaning in ThinkTank, depending on the context in which they appear. In all cases, the appropriate meaning will be clear from the screen, the reference

card, and the reference guide.

—45—

Page 3

Living Videotext, Inc.

ThinkTank Manual

Program by: David Winer

with assistance from: Jonathan Liewellyn

Manual by: John Unger Zussman

with assistance from: David Greene

Page 4

Software:

Copyright Cc) 1983

Living Videotext. Inc.

All rights reserved

Copyright (c) 1981

Apple Computer, Inc.

Parts of this software are copyrighted by

The Regents of the University of California, 1979

Manual:

Copyright (c) 1983

Living Videotext, Inc.

All rights reserved

Living Videotext, Inc.; Apple Computer, Inc.; and the Regents

of the University of California make no warranties, either express or implied, regarding the enclosed computer software

package, its merchantability or its fitness for any particular

purpose. The exclusion or implied warranties is not permitted

by some states. The above exclusion may not apply to you.

This warranty provides you with specific legal rights. There

may be other rights that you have which vary from state to

state.

Page 5

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PART I: LEARNING ABOUT THINKTANK 1

Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION TO THINKTANK 1

Box 1—1: Sample Uses of ThinkTank 2

The Outline Approach 3

Overview of the ThinkTank Manual 5

Support 6

Copy Protection and Software Piracy 7

Chapter 2: THINKTANK ON APPLE PERSONAL COMPUTERS 9

System Requirements 9

Tour of the Apple Keyboards 11

Starting Up ThinkTank 14

Don’t Write—Protect Your Working Disks 25

Exiting From ThinkTank 25

Special Considerations 26

Summary 28

Chapter 3: A BRIEF TOUR OF THINKTANK 29

Getting Synchronized 29

The ThinkTank Screen 30

The Text Area 31

Expanding a Headline 31

The Command Area 33

Command Menus 33

Adding a New Headline 36

Deleting a Headline 38

Correcting Mistakes 38

Leave Disks in Place 39

Backing Up 40

Summary 41

Chapter 4: USING THINKTANK: A TUTORIAL 43

Learning More About ThinkTank 43

The ThinkTank Reference Guide 44

The ThinkTank Reference Card 44

ThinkTank’ s Command System 47

Putting It All Together 51

A Comprehensive Example 53

Getting Around 54

Adding and Editing 57

-i-

Page 6

ThinkTank Manual

Reorganizing an Outline 63

Printing an Outline 66

Creating a New Outline 66

Concluding Note 68

Box 4-1: Printing with 'Uppercase Computers 69

Chapter 5: USING THINKTANK: NOTES AND SUGGESTIONS 71

General Advice 71

Getting Started 72

Getting Around 73

Adding Information 74

Reorganizing 76

Printing and Porting 77

Editing Text 80

Special Features 82

Summary 86

Appendix A: GLOSSARY 87

Appendix B: INTRODUCTION TO THE PASCAL OPERATING SYSTEM 93

What is an Operating System? 93

Files 93

Disks and Devices 94

PASCAL Commands and Programs 95

Appendix C: DISK MANAGEMENT 97

Disk Management Tasks 97

Apple II Series: Floppy Disk Systems 98

Apple II Series: Hard Disk Systems 104

Apple III Systems 104

Appendix D: TECHNICAL INFORMATION 107

Installing ThinkTank on a Hard Disk 107

ASCII Conversion Table 109

ThinkTank Technical Notes 110

PART II: REFERENCE GUIDE 113

THINKTANK COMMANDS 113

ERROR MESSAGES 197

INDEX 217

-ii-

Page 7

Table of Contents

LIST OF FIGUKES AND TABLES

Figure 1—1: Product Plan Outline 4

Figure 1—2: ThinkTank Product Plan Outline 6

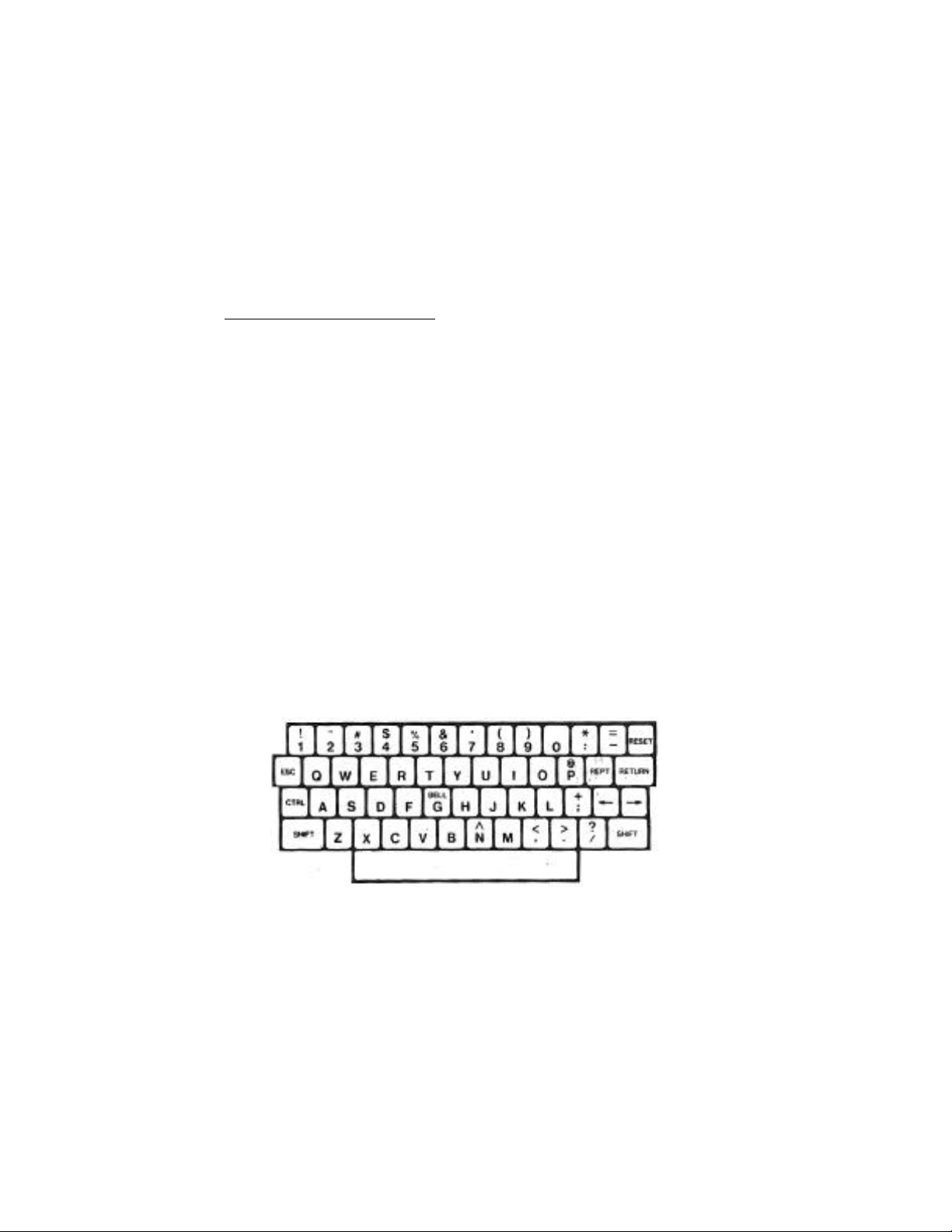

Figure 2—1: Apple II Keyboard Figure 2—2: 11

Figure 2—2: Apple IIe Keyboard 12

Figure 2—3: Apple III Keyboard 13

Figure 2—4: ThinkTank Date Display 16

Figure 2—5: Setting the Date 17

Figure 2—6: ThinkTank Sample Outline 19

Figure 2—7: FILES Command Menu 20

Figure 2—8: EXISTING FILE Menu 21

Figure 2—9: Exit Screen 26

Figure 3—1: ThinkTank Screen 30

Figure 3—2: Expanding a Headline 32

Figure 3—3: Main Command Menu 34

Figure 3—4: Secondary Command Menu 35

Figure 3—5: NEW Command Menu 36

Figure 3—6: Mding a New Headline 37

Figure 4—1: NEW Command Menu Mter Selecting MODE 46

Figure 4—2: Reviewing the Port Format Settings 52

Figure

Figure 4—4: Searching for a Keyword 56

Figure 4—5: Entering a New Paragraph 57

Figure 4—6: Top Level of the Paragraph Editor 58

Figure 4—7: EDIT Command Menu 59

Figure 4—8: Editing a Paragraph 61

Figure 4—9: Defining a Selection 61

Figure 4—10: Moving a Selection 62

Figure 4—11: New Headlines 63

Figure 4—12: Reorganizing an Outline 64

Figure 4—13: Merged Paragraphs 65

Figure 4—14: Creating a New Outline 67

Figure 5—1: Translating Your Commands 84

Figure C—i: SPECIAlIST Command Menu 99

Figure 0—2: DISK MANAGER Command Menu 100

Figure 0—3: Listing a Disk Directory 103

Figure R—1: ThinkTank Screen 113

Table R—1: Minimal Port Format Settings 169

4-3: Expanding and Collapsing 55

—iii—

Page 8

PART I

LEARNING ABOUT THINKTANK

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION TO THINKTANK

ThinkTank (tm) is a visual tool for working with ideas

and information on your personal computer. The ThinkTank

program uses the familiar format of an outline to help you

generate, organize, store, and retrieve ideas with remarkable

ease and efficiency. It is the first idea processor.

ThinkTank is flexible; you can apply it in many ways. It

can serve as your:

* notebook

* address book

* appointment calendar

* card file

* file folder

* file cabinet

* secretary

* administrative assistant

* bulletin board

Because ThinkTank is electronic, you can examine, add, alter,

reorganize, print, or delete your information in seconds.

ThinkTank’s flexibility means that you can adapt it to

your needs and applications. You can choose what kind of in—

formation to store in ThinkTank and how to organize it. You

can use it to write a memo, store a customer list, look up a

telephone number, organize a report, record a family tree, or

catalogue a stamp-collection. Box 1—1, which lists representative uses of ThinkTank, contains just a fraction of its many

applications. ThinkTank is like having an administrative

genie at your beck and call.

—1—

Page 9

ThinkTank Manual

------------------------------------------------------------------

Box 1—1

Sample Uses of ThinkTank

The applications of ThinkTank are as unlimited as your

imagination. Here are a few of its many uses:

Business and Professional Scientific and Technical

* Action lists * Bibliographies

* Appointment calendars * Computer programs

* Business plans * Curriculum vitae

* Catalogues * Grant proposals

* Checklists * Journal articles

* Client records * Monographs

* Corporate reports * Research notes

* Correspondence * Research presentations

* Customer lists * Research reports

* Instruction manuals * Specifications

* Inventory lists

* Legal briefs Educational

* Marketing plans * Bulletins

* Medical records * Class notes

* Memos * Course catalogues

* Minutes * Course outlines

* Notices * Courseware

* Product analyses * Lesson plans

* Product plans * Heading lists

* Project plans * Student records

* Proposals * Test item files

* Personnel records

* Presentations Home

* Reports * Address books

* Resumes * Catalogues of collections

* Schedules * Appointment calendars

* Telephone directories * Correspondence

* To do lists * Genealogies

* Training manuals * Household records

* Word processing * Shopping lists

------------------------------------------------------------------

—2—

Page 10

Introduction

THE OUTLINE APPROACH

The key to the power and flexibility of ThinkTank is its

outline approach to organizing information. The outline approach mirrors our natural way of processing information. Suppose this morning when you came to work you learned that:

There is snow on the ground

Your car needs gas

The price of gas is up again

The stack market is down

It is cold

The consumer price index is up

Your boss is absent

When you think about this information, you don’t think of

it as seven separate, independent items. Instead, you group

related items together in organized categories:

Weather

Snow

Cold

Economy

Stock market down

Inflation

Consumer price index up

Price of gas up

Work

Boss absent

In other words, you organize the items very much like an

outline.

Let’s take a more practical example. Suppose you are a

corporate product manager developing a proposal for a new

product line. You might start by writing down your thoughts

as they occur to you, in random fashion:

—3—

Page 11

ThinkTank Manual

Product type: alcoholic beverage

Primary market: young adults

Taste: sweet and fruity

Position: high Status and sophisticated

But random thoughts do not make a product plan; they must

be arranged into a coherent, persuasive document. So you

might organize your thoughts into an outline as shown in

Figure 1—1. With an outline it is easy to find information.

For example, if you want to examine your ideas on product

positioning, you can go straight to the section on marketing

instead of searching through an unorganized list. You can see

at a glance how your ideas fit together, which sections are

solid and which need further thought. In addition, since the

outline is organized just like the product plan will be, it

makes the document much easier to write.

But it is difficult to work with an outline on paper.

Some sections always seem to end up cluttered and hard to

read, others sparse and empty. If you want to move an idea

from one section of the outline to another, or eliminate it altogether. you have to do a lot of erasing, crossing out, or

cutting and pasting. If you want to share the outline with a

Figure 1—1: Product Plan Outline

—4—

Page 12

Introduction

colleague, you may have to decipher your handwriting or

(worse) have it typed. Outlines on paper can be major

hassles.

Figure 1—2 shows the same outline as ThinkTank might

display it on your computer screen. (This is actually an excerpt from a larger outline included with the ThinkTank

program and used as an example in this manual.) Unlike a

paper outline, a ThinkTank outline is easy to work with

because it is freeform, flexible, and controllable. You can

readily:

* examine any part of it

* change any part of it

* add as many headings as you wish

* add as many levels of subheadings as you wish

* add paragraphs as well as headings

* copy any part of it

* delete any part of it

* move part of it from one section to another

* reorganize it

* search for specific information

* replace specific information

* print any part of the outline

* edit it with a word processor

* send it to other ThinkTank users

In other words, you have complete control over your outline.

You can personalize it to your own needs. And you can perform

all of these.operations with commands that are easy to learn

and easy to use.

As you can see, ThinkTank is an organizing tool that can help

you be more productive and efficient. There seems to be no limit

to its usefulness; the more you use it, the more uses you’ll find.

OVERVIEW OF THE TRINKTANK MANUAL

The ThinkTank manual is divided into two parts, the first

devoted to helping you learn ThinkTank, the second to helping

you use it.

—5—

Page 13

ThinkTank Manual

Figure 1—2: ThinkTank Product Plan Outline

The first part is called Learning About ThinkTank. Following this introduction, Chapter 2 describes how to start up

and begin to operate ThinkTank on your computer. Chapter 3

gives you a brief tour of ThinkTank and contains essential information about using it. Chapter 4 is a tutorial which shows

you how to learn about ThinkTank and introduces you to its

most important commands. Once you have learned the basics,

Chapter 5 contains notes and suggestions to help you get the

most out of ThinkTank. At the end of Part I is a set of appendices including a glossary, an introduction to the PASCAL

operating system, instructions for disk management, and technical information.

The second part of the manual is the Reference Guide,

which contains a comprehensive alphabetical summary of all

ThinkTank commands. The manual concludes with an index.

SUPPORT

The ThinkTank program and manual have been extensively

tested and refined to minimize problems. If a problem occurs,

ThinkTank generally displays an error message to help you diagnose it. There is a list of error messages and suggested solutions in the reference guide.

—6—

Page 14

Introduction

If you have questions or problems that the manual does

not resolve, check with your dealer. ThinkTank dealers are

trained to configure the program to your computer system,

provide guidance and information, solve problems, and help you

get the most out of ThinkTank.

Living Videotext, Inc., is committed to supporting Think—

Tank. If you have a question that your dealer can’t resolve,

or if you purchased your copy of ThinkTank directly from

Living Videotext, please feel free to call us for help. We

also welcome your comments and suggestions for improving subsequent versions of ThinkTank.

In this package you will find the ThinkTank license

agreement. Read it carefully, sign the attached card, and

fill in all requested information including your ThinkTank

serial number, which is displayed on your screen when you

start up the program or change outlines. Mail the card back

to Living Videotext (it is postage—free within the United

States). It registers you as a ThinkTank user and entitles

you to receive support and information about ThinkTank updates, applications, and new products.

Living Videotext maintains a library of ThinkTank

technical notes which contain technical information not

ordinarily required to operate the program. They are meant

for specialized uses and include such topics as custom installation on a hard disk system and how to use ThinkTank with compatible word processing programs. You can order these notes

from Living Videotext for a nominal cost of $5.00. Appendix D

of this manual contains a list of technical notes currently

available; others may be offered periodically.

COPY PROTECTION AND SOFTWARE PIRACY

The ThinkTank license agreement entitles you to use the

program personally or in your business. You may not give or

sell this program, or copies of it, to anyone else. Violation

of this agreement is sometimes called software piracy and it

is illegal.

—7—

Page 15

ThinkTank Manual

Some software companies have chosen to combat piracy by

making their programs impossible to copy. We decided against

such copy protection because it could prevent you from getting

the full benefit of ThinkTank. There are legitimate reasons

for you to make copies.of ThinkTank —— to back up your program

disk in case it becomes damaged, for example. Copy protection

also increases the cost of a program.

We believe strongly in this open policy, but it’s risky.

We will reevaluate it when we release future versions of Think—

tank and other products. If experience shows that our trust

was unwarranted, we will have to implement copy protection and

other defensive measures to protect our software.

We ask that you help us keep ThinkTank flexible, open,

and easy to use. Don't pirate our software!

-8—

Page 16

Apple Versions

Chapter 2

THINKTANK ON APPLE PERSONAL COMPUTERS

ThinkTank comes in three different versions for Apple computers: one for the Apple II and II Plus; one for the Apple

IIe; and one for the Apple III. This chapter contains information and instructions for each version. It covers:

* system requirements

* the Apple keyboards

* starting up ThinkTank

* exiting from ThinkTank

* special considerations for Apple computers

Make sure you have the right version of ThinkTank for your computer, and read the instructions below that apply to it.

SYSTEM REQUIREMENTS

Your equipment should be set up according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Your dealer can provide any assistance

you need.

App1e II and App1e II Plus

To use the Apple II version of ThinkTank, you will need:

* an Apple II or Apple II Plus computer

* 48K bytes or more of internal (random access) memory

(RAM)

* a 16K Apple language or memory card

* two or more floppy disk drives; or one hard disk

drive with the PASCAL operating system

—9—

Page 17

ThinkTank Manual

* a video monitor (preferable) or television set (and

adapter)

* a printer (recommended but not required)

On the Apple II, ThinkTank uses the simple 40—column,

uppercase—only display. If you have an 80—column card, Think—

Tank will automatically switch it off or ask you to do so.

The Apple II version of ThinkTank will also run on an Apple IIe computer -in 40—column, uppercase mode. However, if

you have an Apple 80—Column Text Card in your Apple IIe, you

should obtain the version of ThinkTank specifically designed

for the Apple IIe.

Apple IIe

To use the Apple IIe version of ThinkTank, you will need:

* an Apple IIe computer

* an Apple 80—Column Text Card or Extended 80—Column

Text Card

* two or more floppy disk drives; or one hard disk

drive with the PASCAL operating system

* a video monitor (preferable) or television set (and

adapter)

* a printer (recommended but not required)

Apple III

To use the Apple III version of ThinkTank, you will need:

* an Apple III computer, which includes one floppy

disk drive

* one additional floppy disk drive, or a hard disk

drive

— 10—

Page 18

Apple Versions

* the video monitor supplied with the Apple III

* the System Utilities Disk supplied with the Apple

III

* a printer (recommended but not required)

TOUR OF THE APPLE KEYBOARDS

The keyboards of the Apple II, Apple IIe, and Apple III

computers are illustrated in Figures 2—1, 2—2, and 2—3. They

are very much like a typewriter

—— with some important excep-

tions. Apple computers have several keys. that are not found

on a standard typewriter, and ThinkTank uses some standard

keys in nonstandard ways. These special keys are highlighted

in the figures. Moving roughly counter—clockwise from the upper left, they include:

* ESCAPE OR ESC: The ESCAPE key, as its name implies,

is an all—purpose escape valve which is used to cancel, terminate, or conclude a ThinkTank command or

operation.

* CONTROL or CTRL: The CONTROL key has no effect by

“Reproduced by permission of Apple Computer, Inc. 1983”

Figure 2—1: Apple II Keyboard

—11—

Page 19

ThinkTank Manual

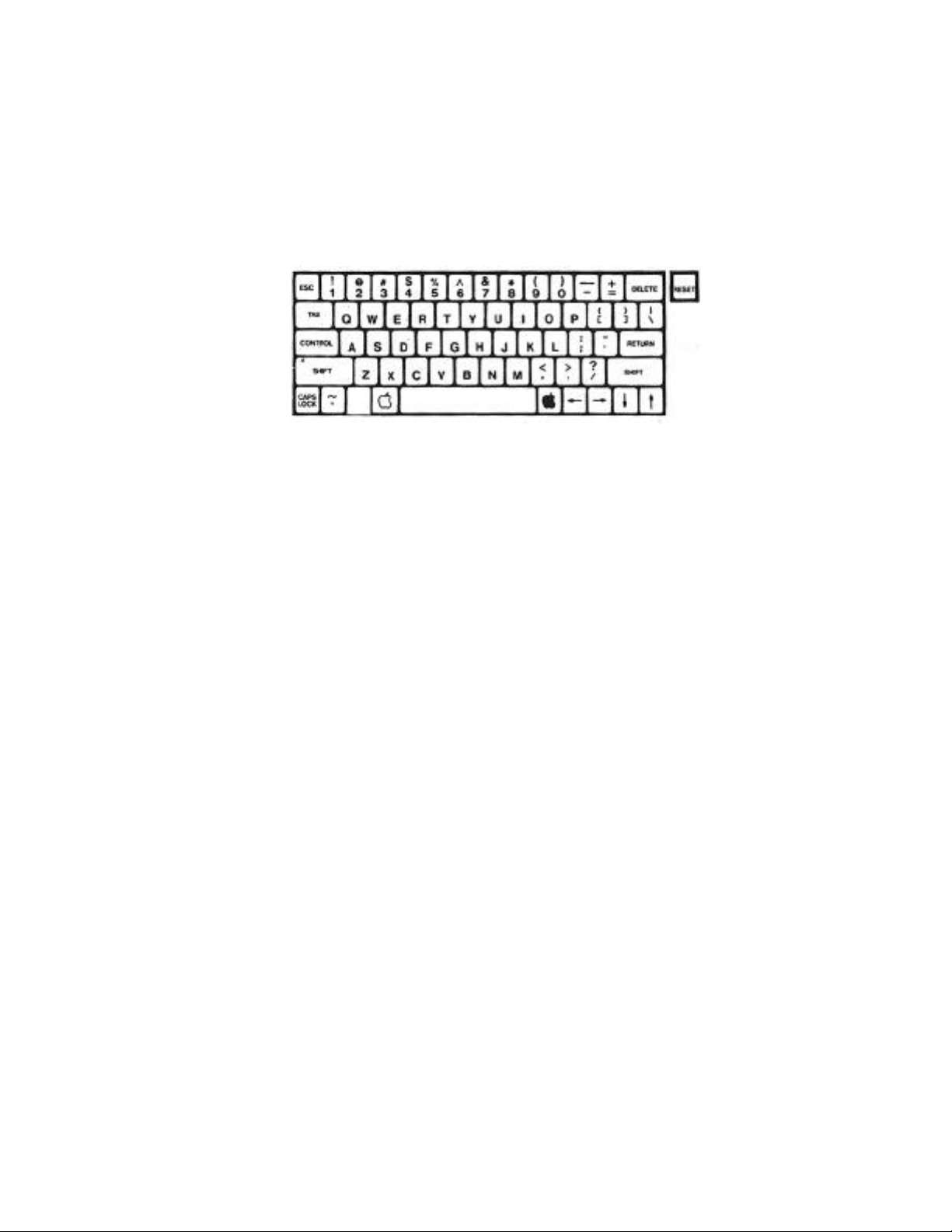

“Reproduced by permission of Apple Computer, Inc. 1983”

Figure 2—2: Apple IIe keyboard

itself, but it is often used with other keys to give

ThinkTank commands. For example, you give the command CTRL—D, which is used to delete text in Think—

Tank’s text editor, by holding down the CTRL key and

pressing D. You must press the CTRL key first and

must not release it before pressing D. The CTRL key

is sometimes abbreviated by the caret ("^“) symbol,

as in ^D.

* SHIFT: As on a typewriter, some Apple keys have two

characters printed on them, like “," (comma) and "<"

(less than) at the bottom right. You can enter the

lower character (",”) simply by pressing the key, or

the upper character (‘<“) by pressing it while holding down either SHIFT key.

On the Apple IIe and Apple III, you can hold down

the SHIFT key to capitalize letters that would otherwise be entered in lowercase. The Apple II SHIFT

key has no effect on letters. All letters are entered and displayed in uppercase regardless of

whether you press SHIFT.

—12—

Page 20

Apple Versions

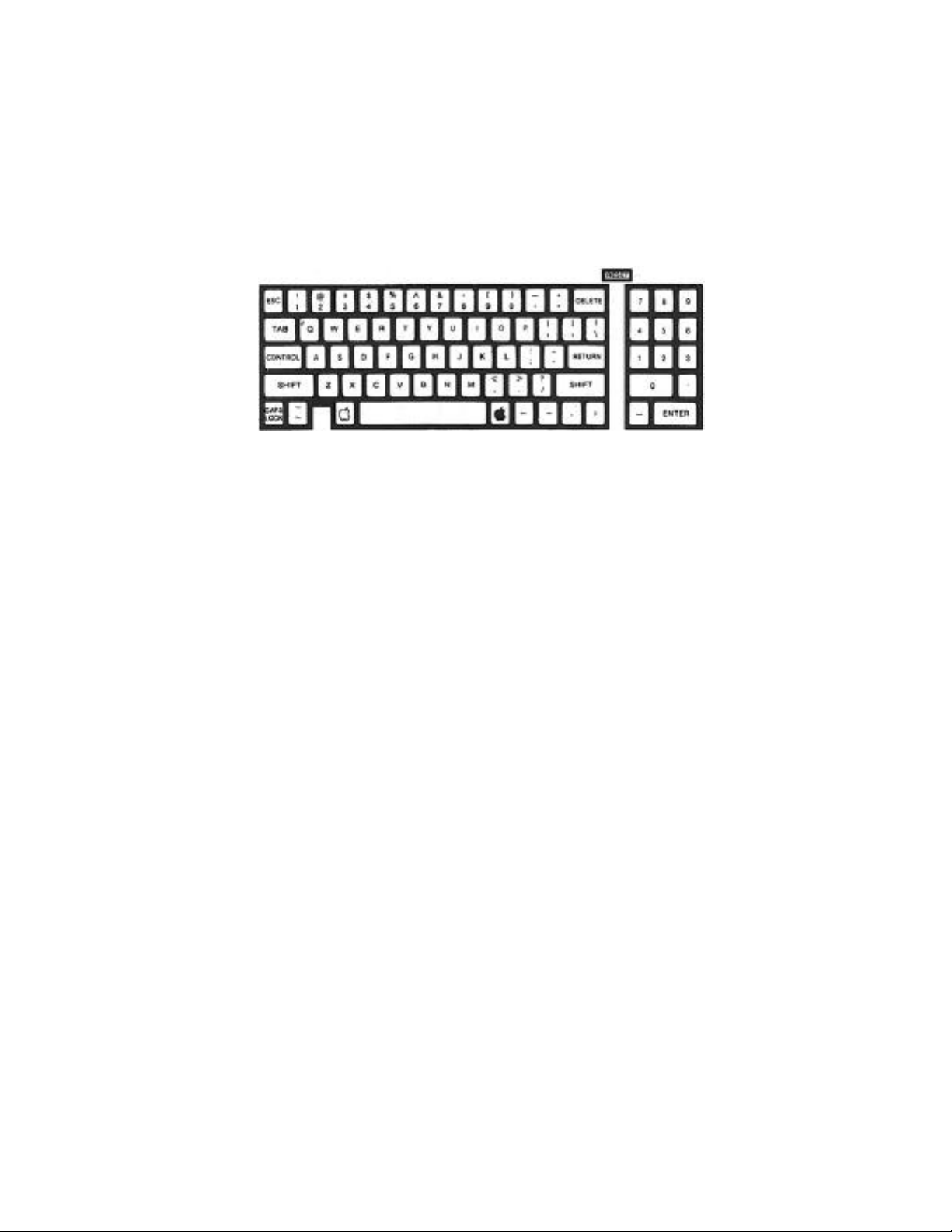

“Reproduced by permission of Apple Computer, Inc. 1983”

Figure 2—3: Apple III Keyboard

* CAPS LOCK or ALPHA LOCK: [Apple IIe and III only]

A shift lock key. Once you press it, all letters

are capitalized until you press it again.

* OPEN—APPLE: [Apple IIe and III only] Not used in

ThinkTank.

* SOLID—APPLE: [Apple IIe and III only] On the Apple

III, accelerates the repeating effect of holding

down a key. Not used in ThinkTank on the Apple IIe.

* SPACE BAR: The space bar is used to enter spaces in-

to your outline, to change lines in ThinkTank menus,

and to enter the SPACE conmmand.

* ARROW KEYS: The left, right, up, and down arrow

keys are used to move a pointer, or cursor, to dif—

ferent headlines, characters, or commands. The left

arrow key is also used as a backspace. Since the Apple II has no up and down arrow keys, we have configured CTRL—O and CTRL—K to substitute for them.

—13—

Page 21

ThinkTank Manual

* REPT: [Apple II only] The REPEAT key, when held

down simultaneously with another key, causes the

other key to repeat. On the Apple IIe and III, you

can repeat a key by simply holding it down.

* RETURN: The RETURN key enters a headline into Think—

Tank or selects a command. You use it to indicate

that you are satisfied with your current entry or

command and want the computer to accept it. Although it is sometimes called a carriage return, you

will generally not use it to move from the end of

one line to the beginning of the next, since Think—

Tank does this automatically.

* DELETE: [Apple IIe only] In ThinkTank’s text

editor, the DELETE key is used to erase characters

or selected blocks of text.

* RESET: The RESET key terminates whatever program is

running and causes your computer to act like it had

just been turned on. (Since this can be a rather

drastic measure, some computers require you to press

CTRL—RESET to minimize the chance of accidentally

resetting your computer.) You may use RESET to

start up ThinkTank (see below). However, DO NOT

PRESS THE RESET KEY while running ThinkTank except

in the rare case that your computer “hangs” and will

not respond to your commands. Pressing RESET causes

a premature exit from the program and you will lose

any information that hasn’t yet been recorded on

your data disk.

In addition to these special keys, the Apple III has a

numeric keypad on the right side of the keyboard. You can use

all of its keys in ThinkTank. The ENTER key is equivalent to

the RETURN key described above.

STARTING UP THINKTANK

This section is divided into two parts. If you have a

hard disk drive on your computer system, skip to the section

on “Hard Disk Systems” later in this chapter.

—14—

Page 22

Apple Versions

Floppy Disk Systems

If you are operating ThinkTank on a floppy disk system,

you will need at least two disk drives. Drive 1 is considered

your main disk drive and is used to load and hold the THINK—

TANK PROGRAM DISK. Drive 2 and other drives contain ThinkTank

data disks. Your drives and their controller should be installed in standard fashion (Slot 6, Drives 1 and 2 on the Apple II and IIe). Your dealer will normally take care of this

for you.

Step 1: INSERT PROGRAM AND DATA DISKS

Depending on your computer, the ThinkTank package may contain two or three disks. One is labelled THINKTANK PROGRAM

DISK and it contains the instructions your computer uses to

run ThinkTank. The second is labelled THINKTANK DATA DISK and

it contains the sample outlines discussed in this manual.

Once you learn how to use ThinkTank, you will create your own

data disks to store your own outlines. If you have an Apple

III, you have a third disk called the THINKTANK BOOT DISK; it

contains the instructions your computer uses to start up Think—

Tank.

(a) Apple II and IIe. Place the THINKTANK PROGRAM DISK

in Drive 1 of your machine and your ThinkTank data disk in

another drive. If this is your first time using ThinkTank,

use the THINKTANK( DATA DISK supplied with the program and insert it in Drive 2.

(b) Apple III. Place the THINKTANK BOOT DISK in the Apple III’s. built—in drive (Drive 1) and your ThinkTank data

disk in another drive. If this is your first time ~using Think—

Tank, use the THINKTANK DATA DISK supplied with ‘the program

and insert it in Drive 2.

Step 2: POWER UP OR RESET

(a)If power is off, turn it on. ThinkTank is designed

to start up automatically when you turn on your computer.

First turn on your monitor or television set if it has a

separate switch. Now simply turn on the power switch, which

is located on the back of your computer near the left—hand

corner.

—15—

Page 23

ThinkTank Manual

Your disk drives will whir and their lights will turn on

as your computer reads information from the disks. On the Apple II or IIe, you will soon see the ThinkTank date display

shown in Figure 2—4, which means that the program has loaded

successfully. Skip to Step 3.

Apple III. Before it loads the program, your com-

puter will display the message:

PUT PASCAL SYSTEM DISK IN BUILT—IN DRIVE. PRESS RETURN.

Remove the THINKTANK BOOT DISK from your built—in

disk drive (Drive 1) and replace it with the THINK—

TANK PROGRAM DISK. Then press RETURN. In a few sec-

onds you will see the date display; skip to Step 3.

(b)If power is on, reset your computer. Make sure you

have completed whatever program you were previously using.

Now simply press the BESET key (on some computers you may have

to press CTRL-~RESET). The program will start as described in

Step 2(a) above.

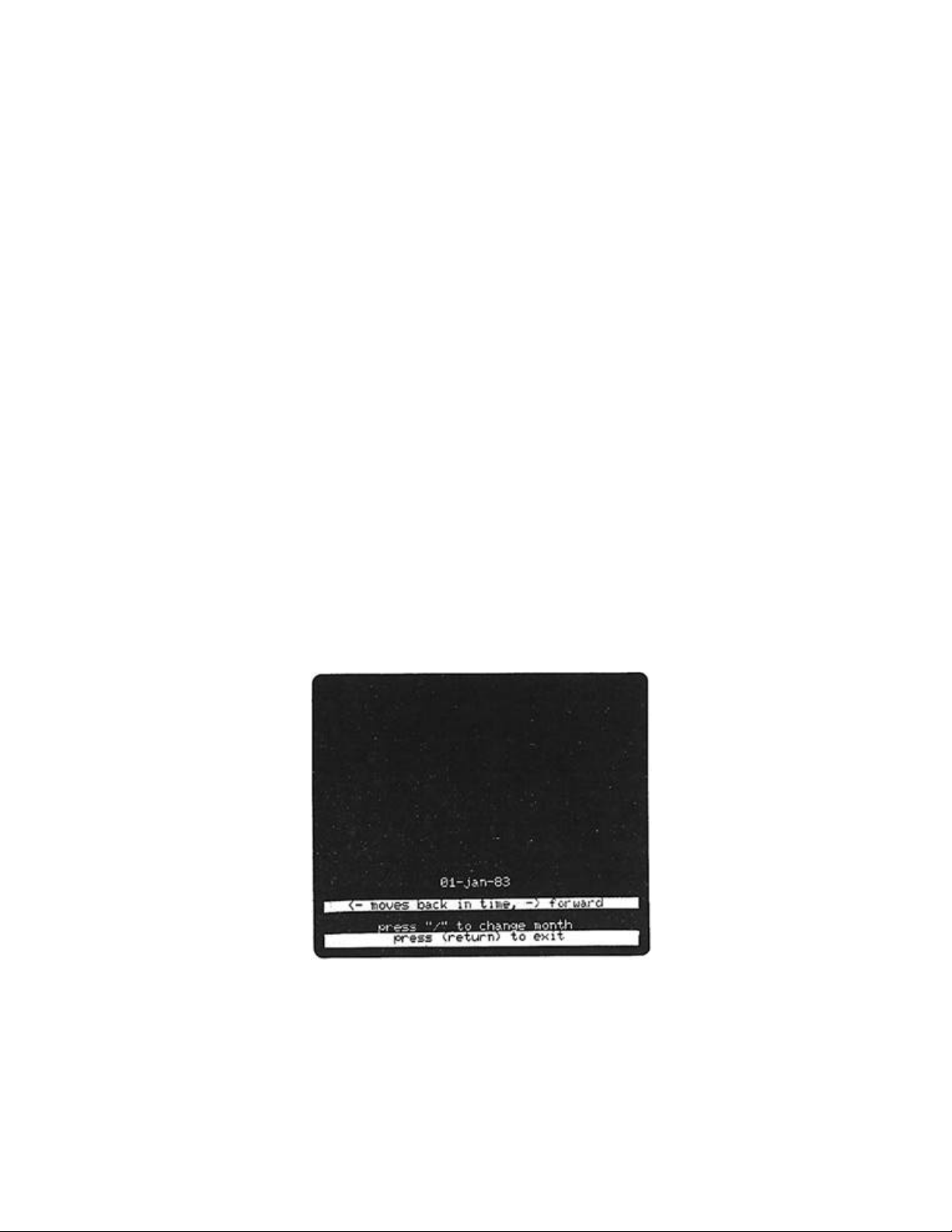

Figure 2—4: ThinkTank Date Display

— 16—

Page 24

Apple Versions

Step 3: SET THE DATE

ThinkTank keeps a record of the current date, which it

“stamps" on the outlines you create and print. Each time you

start up the program, ThinkTank displays the last date entered

and asks you if you want to change it, as shown in Figure 2—4.

Suppose the date shown is incorrect-. Press Y (for YES)

to tell ThinkTank that you want to change it. The program now

displays the current date and your options as shown in Figure

2—5.

Look~at the message:

<— MOVES BACK IN TIME, —> FORWARD

<— and —> represent the left and right arrow keys

respectively. Press these keys and watch what happens to the

date. The right arrow key advances it, while the left arrow

key sets it back. Use the arrow keys to set the correct date.

Now look at the message:

PRESS "/” TO CHANGE MONTH

Figure 2—5: Setting the Date

— 17—

Page 25

ThinkTank Manual

Press the slash ("/“) key and notice that the month begins to

flash. You can now use the arrow keys to set the correct

month. When you’re finished, press the slash key again and

set the year. If you make a mistake, press the slash key

several times to cycle back to the incorrect component.

The message:

PRESS (RETURN) TO EXIT

tells you what to do when the date is correct: press the

RETURN key. The program registers the new date and displays

the ThinkTank title screen as it prepares to load in an

outline.

The process of setting the date is representative of

ThinkTank in general. The program always guides you through

the steps and lets you know what your major options are.

If the date shown in Figure 2—4 is correct, or if you’d

like to skip the date and go right into ThinkTank, just press

N (for NO) or the ESC key —— ThinkTank’s all—purpose escape

valve. ThinkTank will assume that the original date was correct and go directly to the title screen. No damage will be

done if the date is incorrect.

Step 4: LOAD YOUR THINKTANK OUTLINE

(a) Automatic Loading. If you are using ThinkTank for

the first time, it is set to load the sample outline from the

THINKTANK DATA DISK. As you continue to use ThinkTank, it

keeps a record of the last outline you worked on. If you insert the same disk in the same drive next time, ThinkTank will

automatically load it along with the program.

Thus, if you see the title of your outline at the top of

your screen, you have successfully started up ThinkTank. (The

title of the sample outline is THINKTANK( DEMONSTRATION, as

shown in Figure 2—6.) Skip the next section on “Operator

Loading” (as well as the following one on “Hard Disk Systems”)

and continue with “Don’t Write—Protect Your Working Disks.”

— 18—

Page 26

Apple Versions

Figure 2—6: ThinkTank Sample Outline

(b)Operator Loading. If you are not loading the sample

outline or the same one you used last time, you will see the

FILES Command Menu at the bottom of your screen as shown in

Figure 2—7. Press E to tell ThinkTank that you want to open

an existing outline, as indicated at the bottom of the screen.

ThinkTank’s response depends on how it has been

configured to your disk drives. (For more information on configuring ThinkTank, see the DISK command in the reference

guide.)

1. If ThinkTank displays the message:

PRESS (SPACEBAR)

AFTER INSERTING DISKETTE IN DRIVE 2

then it is configured for two floppy disk drives. Simply

place your data disk in Drive 2 and press the space bar. You

will see the title of the outline appear at the top of your

screen.

2. If ThinkTank displays an EXISTING FILE Menu like the one

shown in Figure 2—8, it is configured for more than two floppy

—19—

Page 27

ThinkTank Manual

Figure 2—7: FILES Command Menu

drives or a hard disk drive. Press ~ and ThinkTank will give

you a chance to browse through your outlines. It begins to

display the names or titles of the outlines it finds on your

disks. You can press RETURN to select an outline or the right

arrow key to display the next name. If you want to load the

sample outline, its title is THINKTANK DEMONSTRATION and the

file is called THINKTANK.DB.

When you press RETURN to select the outline you want,

ThinkTank will read it from your data disk and display its

title at the top of your screen. Skip the following section

on “Hard Disk Systems” and continue with "Don’t Write—Protect

Your Working Disks."

If your computer is set up correctly and you follow these

steps, you should have no trouble starting up ThinkTank. In

the rare case that a problem arises, ThinkTank will help to

diagnose it by displaying an error message at the bottom of the

screen. These messages are listed in the reference guide

along with their most likely causes and recommended courses of

action. If problems persist, consult your dealer or Living

Videotext.

—20—

Page 28

Figure 2—8: EXISTING FILE Menu

Apple Versions

Hard Disk Systems

If you have a hard disk drive, its increased capacity and

rapid access will make ThinkTank especially powerful and convenient. To use a hard disk with an Apple II or IIe, you will

need access to the PASCAL operating system (p—System) under

which ThinkTank runs, and you must format at least part of

your hard disk for this system. (For an introduction to the

PASCAL operating system, see Appendix B).

You will also need to install ThinkTank on your hard

disk. Your dealer can take care of this, or y~u can follow

the instructions in Appendix D. The instructions in this section assume that you have already installed ThinkTank on your

hard disk.

If you have floppy disk drives as well as a hard disk,

you may load the ThinkTank program and outlines from either

type of disk.

—21-

Page 29

ThinkTank Manual

Step 1: ENTER THE PASCAL OPERATING SYSTEM

There are several ways to do this, depending on your

system. You may simply have to turn on your computer or press

the RESET key (CTRL—RESET on some machines). If you are running a PASCAL program, simply exit from it. If you are using

another operating system, you may have to execute a program

which loads PASCAL. Your dealer can help you determine which

method to use.

When you enter the PASCAL system you will see the system

command prompt~

Command: E(dit, R(un, F(ile, C(omp,

L(ink, X(ecute, A(ssem, D(ebug, ?

(If you see only half of this prompt line, press CTRL—A to

switch from one half to the other.)

Step 2: SET SWAPPING’ OPTION (APPLE II and IIe ONLY)

Once the command prompt is displayed, turn on PASCAL’s

"swapping” option if you have an Apple II or IIe. Type S and

PASCAL will tell you whether swapping is on or off and ask you

whether you want to “toggle” (change) it. Assuming it’s cur-

rently off, type Y (for YES) PASCAL will activate swapping

mode and display the command prompt again. (If swapping is

currently on —— as it would be if you had already run Think—

Tank in the current PASCAL session —— type N for NO instead of

Y.)

Step 3: EXECUTE THINKTANK

When PASCAL displays the command prompt again, press X

(for execute). The computer will respond:

EXECUTE WHAT FILE?

Enter the program name TANK, preceded by its volume or device

number. Suppose you have installed the program on Drive I

(PASCAL device #4) in a volume called TANK:. Then you could

enter either of the following:

—22—

Page 30

Apple Versions

#4: TANK

TANK: TANK

and press RETURN. In a moment you will see the ThinkTank date

display (Figure 2—4 above), which indicates that you have successfully loaded ThinkTank. If you have any trouble, check

the installation information in Appendix D.

Step 4: SET THE DATE

Setting the date on a hard disk system is identical to

doing ‘so on a floppy disk system. Follow the instructions for

Step 3 under “Floppy Disk Systems” above. Then return here

for Step 5.

Step 5: LOAD YOUR THINKTANK OUTLINE

(a) Automatic Loading. If you are using ThinkTank for

the first time, it is set to load the sample outline from

Drive 2 (PASCAL device #5). As you continue to use ThinkTank,

it keeps a record of the last outline you worked on. If it’s

available in the same drive next time, ThinkTank will

automatically load it along with the program.

Thus, if you see the title of your outline at the top of

your screen, you have successfully started up ThinkTank. (The

title of the sample outline is THINKTANK DEMONSTRATION, as

shown in Figure 2—6 above.) Skip the next section on

“Operator Loading.”

(b) Operator Loading. If you are not loading the sample

outline or the same one you used last time, you will see the

PILES Command Menu at the bottom of your screen as shown in

Figure 2—7 above. Press E to tell ThinkTank that you want to

open an existing outline, as indicated at the bottom of the

screen.

ThinkTank’s response depends on how it has been

configured to your disk drives. (For more information on configuring ThinkTank, see the DISK command in the reference

guide.)

1. If ThinkTank displays an EXISTING FILE Menu like the one

—23—

Page 31

ThinkTank Manual

shown in Figure 2—8 above, it is correctly configured for a

hard disk drive (or possibly for more than two floppy

drives). Press B and ThinkTank will give you a chance to

browse through your outlines. It begins to display the names or

titles of the outlines it finds on your disks. You can

press RETURN to select an outline or the right arrow key to

display the next name. If you want to load the sample

outline, its title is THINKTANK DEMONSTRATION and the file is

called THINKTANK.DB.

When you press RETURN to select the outline you want,

ThinkTank will read it from your data disk and display its

title at the top of your screen.

2. If ThinkTank displays the message:

PRESS (SPACEBAR)

AFTER INSERTING DISKETTE IN DRIVE 2

then it is configured for two floppy disk drives. If Drive 2

(PASCAL device #5) on your system is a floppy disk drive,

simply place your data disk in Drive 2 and press the space

bar. If not, you (or your dealer) will have to reconfigure

ThinkTank as a hard disk system as described in Appendix D under “Installing ThinkTank on a Hard Disk.”

If your computer is set up correctly and you follow these

steps, you should have no trouble starting up ThinkTank. In

the rare case that a problem arises, ThinkTank will help to

diagnose it by displaying an error message at the bottom of

the screen. These messages are listed in the reference guide

along with their most likely causes and recommended courses of

action. -You should also recheck the instructions for installing ThinkTank on a-hard disk in Appendix D. If problems persist, consult your dealer or Living Videotext.

You may want to configure your hard disk system to start up

ThinkTank automatically when you turn on your computer, or

at least to set the swapping option when you enter PASCAL or

execute ThinkTank. Your dealer can help you do this or you

can do it yourself. Detailed technical information on this

topic is available from Living Videotext in a ThinkTank

technical note described in-Appendix D of this manual.

—24—

Page 32

Apple Versions

DON’T WRITE—PROTECT YOUR. WORKING DISKS

Most disks have a small notch on one edge called a

write—enable or write—protect notch. Only if your computer

senses that this notch is present will it record new information on the disk. Many programs.suggest that you protect them from

inadvertent erasure by covering this notch with a small

“write—protect tab.” DON’T do this with your ThinkTank working disks! ThinkTank is designed so that information must

often be stored on both the THINKTANK PROGRAM.DISK and your

data disks. They must not be write—protected.

For extra security, you may Want to write—protect your

backup copies of these disks -- the ones you don’t use from

day to day. You may cover the notch with one of the tabs supplied with most disks or with a piece of adhesive tape. Remember to remove it if you ever have to use one of your backup

disks in your computer.

EXITING FROM THINKTANK

Once you’ve loaded an outline, the ThinkTank screen looks

like Figure 2—6. Notice the message:

(ESC) TO EXIT THINKTANK

at the bottom of the screen. To exit from the program, you

simply press the ESC (ESCAPE) key -- ThinkTank’s all—purpose

escape valve.

Try it. ThinkTank asks you to confirm your intention as

shown in Figure 2—9. If you respond Y (for YES), ThinkTank

will close your files and return you to the PASCAL operating

system. (If you respond N for NO, ThinkTank will return you

to your outline.) When you see the PASCAL command prompt:

Command: E(dit, R(un, F(ile, C(omp,

L(ink, X(ecute, A(ssem, D(ebug, ?

(or at least part of it), you can run another program or turn

off your computer.

—25—

Page 33

ThinkTank Manual

Figure 2—9: Exit Screen

Always use this procedure to exit from the ThinkTank

program. DO NOT simply shut off or reset your computer; al-

though doing so will terminate the program without damage, you

always risk losing information that h~s not yet been recorded

on your data disk. The ESC procedure is the only method of

making sure your files are closed and all your information is

saved.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Except for this chapter, the ThinkTank manual is designed

to be used with many different computers. Because of this,

the screen illustrations may not look quite like your computer

screen when you operate ThinkTank.

Here are several points to keep in mind about Apple computers as you read the rest of this manual:

Apple II and Apple II Plus

* A few keys found on many computers are missing on

the Apple II. ThinkTank allows you to substitute

other keystrokes for them as follows:

—26—

Page 34

Apple Versions

Character Description Keystroke

-----------------------------------------------

Up arrow CTRL—O

Down arrow CTRL—K

\ Backslash CTRL—Y

_ Underscore CTRL—Z

[ Left square bracket CTRL—J

] Right square bracket SHIFT—M

For example, if you want to insert a backslash into

your outline, press CTRL—T instead.

* The Apple II can only display 40 characters on a

line and all letters are shown in uppercase. The Apple II version of ThinkTank does not support special

cards designed to circumvent these limits and will

turn them off (or ask you to do so) when you start

up the program. The limits are significant because

ThinkTank headlines and patterns must fit on one

line.

Apple

* The Apple IIe version of ThinkTank requires an Apple

* In the upper—right corner of the keyboard, the Apple

Apple III

* You will need the System Utilities Disk supplied

IIe

80—Column Text Card or Extended 80—Column Text

Card. If you don’t have one, use the Apple II version instead.

IIe has a special key called DELETE. You can use it

in ThinkTank’s text editor to erase characters or

selected blocks of text. See the EDIT listing in

the reference guide f or further information.

with the Apple III to format, copy, and list Think—

Tank disks.

—27-

Page 35

ThinkTank Manual

SUMMARY

This chapter has discussed the use of ThinkTank on Apple

computers. After reading it, you should know:

* what equipment is needed to run ThinkTank on the Ap-

ple II, Apple IIe, and Apple III

* how the Apple’s special keys are used

* how to start up the ThinkTank program

* how to exit from ThinkTank

* what features of your computer to keep in mind as

you read this manual

In Chapter 3 we will complete our discussion of the fundamentals of ThinkTank by taking you on a brief tour of its

features.

—28—

Page 36

Brief Tour

Chapter .3

A BRIEF TOUR OF THINKTANK

This chapter Contains a brief tour of the ThinkTank

program. Like a ten—day, seven—country European tour, it hits

only a few of the highlights. But it also introduces you to

the way ThinkTank works and presents essential information

about operating it. After reading it, you can readily master

the program by experimentation, guided by the ThinkTank tut-

orial in Chapter 4.

This chapter includes material on:

* the ThinkTank screen

* examining an outline

* using menus

* command keys

* adding and deleting headlines

* correcting mistakes

* inserting and removing disks

* backing up

GETTING SYNCHRONIZED

Start up the ThinkTank program, set the date, and load in

the sample outline from the THINKTANK DATA DISK, as described

in Chapter 2 of this manual. Your screen should look approximately like Figure 3—1; it may look slightly different depending on your computer system. If you have any trouble, review

the startup instructions in Chapter 2.

If you’ve loaded in the sample outline but your screen

doesn’t look like Figure 3—1, someone may already have examined it. To restore it to its original condition, follow

these three instructions:

—29—

Page 37

ThinkTank Manual

1. Type the number 1000 and press the left arrow key.

2. Type “." (period).

3. Press the RETURN key. When ThinkTank finishes

expanding, press it again.

Take note of this procedure; you’ll need it again later. By

the end of the tutorial you’ll know why it works.

There are actually four sample outlines on the THINKTANK

DATA DISK. You can see their titles —— PRODUCT PLAN, PERSONNEL RECORDS, LESSON PLANS, and CHRISTMAS LETTER in the top

part of your screen. Each represents a typical application of

ThinkTank. For example, the PRODUCT PLAN’~ outline is a hypothetical product plan for a fictional distiller of alcoholic

beverages called Stoned Soul, Inc.

THE THINKTANK SCREEN

While you operate the ThinkTank program, your computer

‘screen is divided into two parts. The upper part, which occupies most of the screen, is the Text Area. The lower four

lines comprise the Command Area. These areas are labelled in

Figure 3—1.

Figure 3—1: ThinkTank Screen

-30-

Page 38

Brief Tour

TEE TEXT AREA

The Text Area is where ThinkTank displays the outline

you’re working on, or as much of it as fits on the screen.

The entries you see are headlines and they are arranged in

outline form, with some indented under others. These headlines may represent the “surface” of a larger outline, with

more information hidden “beneath” them, at lower levels of the

outline. You can tell whether a headline contains additional

information by its leader or leading character. A “+“ leader

means that there is more material beneath the headline, a "-"

leader means there is none.

One line in the Text Area, PRODUCT PLAN, is highlighted.

The highlight is called the bar cursor, and the highlighted

headline is called the bar cursor headline. A cursor is a

pointer; you can move the bar cursor around your outline to

point to different headlines. Notice the message ARROW KEYS

MOVE BAR CURSOR near the bottom of the screen. Experiment

with the up and down (or left and right) arrow keys to see how

to move the bar cursor from one headline to another. When

you’ve finished experimenting, move the bar cursor to PRODUCT

CONCEPT, just below PRODUCT PLAN.

Moving the bar cursor is important because of a key Think—

Tank operating principle:

THE POSITION OF THE BAR CURSOR DETERMINES

WHERE YOUR COHMANDS WILL TAKE EFFECT.

Get in the habit of moving it before selecting commands.

EXPANDING A HEADLINE

You can see the information under a headline by expanding

it. If you press “<“ (or, without shifting, “,“), ThinkTank

displays the next lower level of the outline under the headline you expanded, as shown in Figure 3—2. You can see a new

paragraph and four new headlines under PRODUCT CONCEPT.

A paragraph is simply a block of text under a headline.

It need not literally be a paragraph; it may consist of

several phrases, sentences, or paragraphs up to a maximum of

2048 characters.

—31—

Page 39

ThinkTank Manual

Figure 3—2: Expanding a Headline

We’ve chosen the “<“ key to expand a headline because it

represents the command visually, going from small to

large.

In addition to pressing "<" or “,“, you can also expand a headline by pressing RETURN. Do so several times. Each time,

ThinkTank expands the next headline. We call RETURN a

“reading” key because you can use it to “read through” an

outline.

On most computers, expanding these headlines makes the

visible outline too big to fit on the screen, so ThinkTank

pushes part of it off. Don’t worry about that; it’s still

there, just not visible. You can think of the screen as a

window on your outline, displaying as much of it as fits. For

information about adjusting this window, see the SPACE and

WINDOW commands in the ThinkTank reference guide.

The outline is now fairly cluttered and it’s hard to see

exactly where you are. Press the left arrow key several times

to move the bar cursor back to PRODUCT CONCEPT. Now type “>“

(or, without shifting, “.“). ThinkTank collapses (hides) the

material that you expanded, and the outline is very nearly as

it was when you began.

—32—

Page 40

Brief Tour

THE COMMAND AREA

The Command Area occupies the bottom four lines of the

screen, the first and last of which are highlighted. This

area contains information about ThinkTank commands and about

the status of the program. When you first load an outline into ThinkTank, the top line of the Command Area contains the

name and version number of the program. The remaining lines

suggest actions you can take at this point. As shown in

Figure 3—1, they say that you can use the arrow keys to move

the bar cursor, you can press the slash (“/”) key to display

the “Command Menu”; and you can press ESC to exit from the

program. This represents the Top Level of the program, where

ThinkTank is simply waiting for you to tell it what to do.

COMMAND MENUS

The Main Command Menu

Press the slash (“/”) key. The initial instructions in

the Command Area are replaced by the Main Command Menu shown

in Figure 3—3. This display is called a menu because, like a

menu in a restaurant, it contains a list of choices: EXPAND,

COLLAPSE, NEW, and so on. The menu itself is displayed in the

middle two lines of the Command Area, and one item (in this

case, EXPAND) is highlighted by a pointer —— the menu cursor.

The top line of the Command Area identifies the menu, while

the bottom line (the explanation line) contains a brief explanation of the highlighted option. In this case, it says

that the EXPAND option will REVEAL HIDDEN TEXT under the bar

cursor headline.

When a command menu is displayed, the right and left

arrow keys no longer move the bar cursor; they move the menu

cursor. As you try this, notice how the explanation line

changes to describe each new command. You can use this feature of ThinkTank to teach yourself about almost all of its

commands. (These brief explanations are also included on the

ThinkTank reference card.) The space bar moves the menu cursor from one line of the menu to the other. Once you have

moved the cursor to the command you want, you can press its

command key to execute it.

—33—

Page 41

ThinkTank Manual

Figure 3—3: Main Command Menu

Command Keys

Notice that there is a single character displayed at

either end of the explanation line. This character is the

command key for the highlighted option. For example, the command key for EXPAND (as shown in Figure 3—3) is “<“. That’s

why you could give the EXPAND command earlier by pressing

“C’. You don’t have to display the Main Command Menu to

select the commands on it; you can press their command keys at

Top Level.

Command keys allow you to speed through commands once you

know them. Since ThinkTank’s command keys may be changed,

remember that:

TEE CORRECT COMMAND KEY FOR AN OPTION IS

ALWAYS DISPLAYED ON THE BOTTOM LINE OF THE COMMAND AREA WHEN THE OPTION IS HIGHLIGHTED.

—34—

Page 42

Brief Tour

The Secondary Command Menu

Use the arrow keys to move the cursor to the last selec-

tion on the Main Command Menu, EXTRA. The explanation line

reads MORE THINKTANK COMMANDS. Press the slash key, its command key, and the Secondary Command Menu appears as shown in

Figure 3—4. The options include COPY, ALPHA, REVERSE, and so

on. These “secondary’ commands are used less often than those

on the Main Command Menu.

The last option on the Secondary Command Menu reads

ESCAPE. Its explanation line reads CANCEL THIS COMMAND and

its command key is ESC. When you press ESC, the menu disappears and ThinkTank returns to the Top Level.

It’s important to understand how menus work because most

ThinkTank commands appear on them. Many commands have options

which you can select from submenus. ThinkTank doesn’t actually execute these commands until you’ve progressed down a

“command tree” of options, telling it exactly what you want it

to do. The ThinkTank reference card shows the top levels of

these command trees, and the reference guide contains a complete list of ThinkTank commands in alphabetical order.

Figure 3—4: Secondary Command Menu

—35—

Page 43

ThinkTank Manual

ADDING A NEW HEADLINE

To see how this menu system works, let’s enter a new headline. You can’t just move the bar cursor where you want a new

headline and start typing. That’s because:

UNLESS YOU TELL IT OTHERWISE, THINKTANK INTERPRETS YOUR KEYSTROKES AS COMMANDS, NOT TEXT.

You tell it otherwise by giving the NEW command.

First move the bar cursor to PRODUCT PLAN and then press

N to select NEW. ThinkTank now displays a submenu called the

NEW Command Menu shown in Figure 3—5. From it you can choose

what kind of material to add and where. This menu is described fully in the reference guide; for now simply move the

menu cursor to RIGHT. The explanation line reads MAKE NEW

HEADLINE AT DEEPER LEVEL.

Press R (its command key) to select this option. Think—

Tank opens up a space for the new headline just below PRODUCT

PLAN and to the right, as shown in Figure 3—6. It displays a

“?“ in the leader position indicating that it is ready for

your new headline. In addition, ThinkTank displays a new

Figure 3—5: NEW Command Menu

—36—

Page 44

Brief Tour

pointer called the flashing cursor at the place where the new

headline will start. In the Command Area it tells you to:

TYPE NEW HEADLINE, THEN (RETURN)

(LEFT ARROW) ERASES LAST CHARACTER

Type the words:

This is a new headline

and watch them appear on the empty line. If you make a

mistake,..use the left arrow key to backspace over it. Press

RETURN to tell ThinkTank that you’re finished. ThinkTank

changes the leader to and returns to the Top Level where

no menu is displayed. The bar cursor points to your new headline.

What you’ve just done —— adding a new headline —— is

typical of the way you do most things with ThinkTank. In

general, using ThinkTank is a matter of selecting options from

menus until you specify exactly what you want to do. Think—

Tank always guides you through its menus with prompts and explanations.

Figure 3—6: Adding a New Headline

—37—

Page 45

ThinkTank Manual

DELETING A HEADLINE

You’ve just added a headline that doesn’t belong in this

outline; let’s delete it. First make sure the bar cursor

points to (is highlighting) the headline you want to delete.

Then press “ID” to select the DELETE command from the Main Command Menu. (Note that D, the DELETE command key, works only

within the Main Command Menu, not from Top Level.)

ThinkTank responds by displaying the DELETE Command

Menu. The option you want is OUTLINE and its command key is

0. When you press “0”, ThinkTank removes the new headline

from your screen and returns again to Top Level.

CORRECTING MISTAKES

Errors in Commands: ThinkTank’s Escape Valve

Earlier in this chapter you used the ESC (ESCAPE) key to

exit from the Secondary Command Menu and return to Top Level.

This illustrates an important ThinkTank operating principle:

WHENEVER YOU WANT TO STOP WHAT YOU’RE DOING,

USE THINKTANK’S “ESCAPE VALVE.”

For all practical purposes, you can always use the ESC

(ESCAPE) key to stop your current operation, even when this op-

tion isn’t specifically listed in the Command Area.

As you saw in the last chapter, ThinkTank’s escape valve

also functions to leave the program when you’re finished using

it. To exit from the Top Level of ThinkTank, simply press

ESC. If you are deeper within the program, you may need to

press ESC more than once. For example, from the Main Command

Menu, press ESC once to return to Top Level and once more to

exit from the program.

Errors in Text

There are two basic ways of correcting or revising the

text that makes up the headlines and paragraphs of an outline. First, you can use the left arrow key to backspace to

your mistake, and then retype. This is probably the best way

to correct errors made as you’re typing in new material.

—38—

Page 46

Brief Tour

ThinkTank also has two powerful text editors built into

it, which you can reach through the EDIT option on the Main

Command Menu. These editors, which are described fully in the

reference guide, enable you to insert, append, or delete sections of text; copy them or move them around; and search for

or replace key phrases. They are the best way to revise the

text of an outline once it’s been entered.

LEAVE DISKS IN PLACE

Most personal computers don’t have enough memory to hold

both the ThinkTank program and a typical outline. So Think—

Tank uses your program and data disks as ongoing storage

units. Besides increasing the size of the outlines you can

create, this minimizes data loss in the event of a power

failure or other error.

However, if one of the disks isn’t where the program expects it to be, an error will result. The error will not

damage your computer or your disks, but you may have to reload

the program and reenter some of your outline. Therefore, as a

general rule,

LEAVE BOTH YOUR PROGRAM DISK AND YOUR DATA

DISK IN THEIR DRIVES WHILE USING THINKTANK,

UNLESS THE PROGRAM SPECIFICALLY ALLOWS YOU TO

REMOVE THEM.

There are two times when you may need to take a disk out

of its drive. First, when you’re switching from one outline

to another or creating a new one, you nay need to change data

disks. You can’t just replace one data disk with another. Instead you should use the FILES command to “close” the current

outline and “open” the next. ThinkTank will tell you when

it’s OK to switch data disks. Be careful not to remove the

THINKTANK PROGRAM DISK at this time.

The second instance in which you may need to remove a

disk is when you’re porting (transferring) outline material into or out of a text file. To do this you may temporarily have

to replace the THINKTANK( PROGRAM DISK with a disk to contain

the ported material.. Again, ThinkTank will tell you when to

remove the program disk and when to replace it.

—39—

Page 47

ThinkTank Manual

BACKING UP

Since computer disks are fragile, you should always have

more than one copy of them. The basic rule of thumb for

backing up your disks is:

NEVER GET CAUGHT WITHOUT A BACKUP COPY OF ANY

INFORMATION YOU COULD NOT, OR WOULD NOT WANT

TO, RE—ENTER IF IT WERE LOST.

Backing Up Your ThinkTank Disks

You should make backup copies of your THINKTANK PROGRAM

DISK and THINKTANK DATA DISK as soon as you receive them. If

you haven’t done so already, back them up now. The simple

procedure is described in Appendix C under “Copying Disks.”

Depending on your computer, you may be able to back up your

disks without exiting from ThinkTank; or you may have to exit

and use your system disks.

Since backup procedures themselves occasionally fail, we

recommend that you use your copies of the THINKTANK PROGRAM

DISK and THINKTANK DATA DISK from day to day, storing the

originals in a secure place. That way, if you ever discover

an error in your working disk, you’ll be sure of having an intact copy available.

Both the original and backup copies of the THINKTANK

PROGRAM DISK are restricted to your own personal or business

use. According to the license agreement that you signed when

you purchased ThinkTank, you may not give copies of the program to

anyone else, and you may not resell the program to anyone else.

Backing Up Your Outlines

Once you create your own outlines, you should back them

up whenever you make a substantial change to the material on a

disk. This may mean each day an outline is used, or even more

often if it contains critical information. You may also want

to write—protect your backup disks for extra protection.

—40—

Page 48

Brief Tour

One way to back up a ThinkTank outline is to copy the entire disk, just as you backed up your ThinkTank disks. A better way is to use ThinkTank’s PORT command to transfer your

outline to a text file. The process is described in the

reference guide under PORT. Backing up your program and data

disks is a brief and convenient process, but you must do it

conscientiously. A few minutes spent today can save hours

tomorrow.

SUMMARY

You’ve just finished your brief tour of ThinkTank. It

covered the ThinkTank screen; moving the bar cursor; expanding, adding, and deleting a headline; command menus and command keys; correcting mistakes; and backing up. If you wish,

you can exit from ThinkTank now by pressing ESC at Top Level.

Or you may leave the program running and go on to the Think—

Tank tutorial in Chapter 4.

This chapter has emphasized several ThinkTank operating

rules, including:

1. The position of the bar cursor determines where your

commands will take effect.

2. The correct command key is always displayed on the

bottom line of the Command Area.

3. Unless you are entering text, ThinkTank interprets

your keystrokes as commands.

4. Whenever you want to stop what you’re doing, use

ThinkTank’s escape valve (the ESC key).

5. Leave both your program disk and your data disk in

their drives while using ThinkTank, unless the

program specifically allows you to remove them.

6. Never get caught without a backup copy of any information you could not, or would not want to, re—enter

if it were lost.

—41—

Page 49

ThinkTank Manual

With the material in this chapter, you should be ready to

experiment with ThinkTank. The next chapter, the tutorial,

describes your primary resources for learning about ThinkTank

and introduces you to each of the major things you can do with

it.

—42—

Page 50

Tutorial

Chapter 4

USING THINKTANK: A TUTORIAL

ThinkTank’s extensive prompts, menus, and explanations on

the screen make it virtually self—teaching. This tutorial

will help you begin mastering the program.

We assume you have already spent some time browsing

through command menus, reading explanations of the options,

and selecting options with their command keys. If not, please

look over “Starting Up ThinkTank” and “Exiting from ThinkTank”

in Chapter 2, and the “Brief Tour of ThinkTank” in Chapter 3,

before plunging into this chapter.

This tutorial is meant to be read while sitting at your

computer, trying out the examples. If you are not already

operating ThinkTank, start it up and load in the sample

outline according to the instructions in Chapter 2. Then

restore it to its original condition as shown in Figure 3—1

and described under “Getting Synchronized” in Chapter 3.

At the end of this tutorial you will create a new

outline. You will need a formatted disk to store it; prepare

one now if you don’t have one. Instructions for formatting

disks are contained in Appendix C.

LEARNING MORE ABOUT THINKTANK

There are three important tools for learning about Think—

Tank. First, the reference guide provides a full description

of each command, arranged alphabetically. Second, the

reference card provides a concise summary of the entire Think—

Tank command structure, organized functionally. Third, Think—

Tank’s system of screen prompts, menus, explanations, cursors,

highlights, and keystrokes —— The command system —— allows you

to explore ThinkTank’s command structure directly. Let’s take

a closer look at each of these resources.

—43—

Page 51

ThinkTank Manual

THE THINKTANK REFERENCE GUIDE

Part II of this manual, the reference guide, contains a

full description of each ThinkTank command, including how it

works, where to find it, its command key(s), whether it takes

a command prefix, and cross—references to related entries.

Keep the reference guide handy as you begin to use Think—

Tank. When you want more information about an option than the

brief explanation on the screen provides, the reference guide

is the place to turn. The entries of this “dictionary” are arranged alphabetically.

The reference guide is the only place you will find information about five Top—Level commands that don’t appear on command menus (and whose functions, therefore, are never explained on the screen). These commands are PERCENT, RE—ENTER,

BACKGROUND, SPACE, and READ.

At the end of the reference guide is a list of error

messages that ThinkTank displays to help you when something

goes wrong.

THE THINKTANK REFERENCE CARD

The reference card provides a concise summary of Think—

Tank’s entire command structure, organized by function into

seven broad categories. The brief explanation for each command on the reference card is the same one you see on the

screen when the command is highlighted by the menu cursor.

If the reference guide is like a dictionary of ThinkTank

commands, the reference card is like a map of them. To see

this, press the slash (“/”) key from the Top Level of Think—

Tank to display the Main Command Menu, which is shown in

Figure 3—3. Now look at the reference card and compare the

two.

The NEW command under “Adding Information” on the reference card corresponds to the NEW command on the Main Command

Menu. Note that NEW appears at the leftmost edge of its panel

on the reference card. So do all commands on the Main Command

Menu.

—44—

Page 52

ThinkTank Manual

Figure 4—1: NEW Command Menu After Selecting MODE

As a general rule, there is only one “path” to each Think—

Tank command. The EDIT commands, however, are exceptions. If

you look under “Editing Text” on the reference card, you’ll

see that you can also get to either text editor by selecting

EDIT from the Main Command Menu. Then you can choose HEADLINE

or PARAGRAPH depending on which editor you want. Thus, each

editor is accessible in two different contexts: you may

select EDIT directly from the Main Command Menu or as an option under NEW.

On the back, the reference card includes a “Keystroke Con—

figuration Chart.” Many ThinkTank command keys are

configurable (changeable); this chart shows you how they are

configured in your version of ThinkTank. (See KEYS in the

reference guide for information on reconfiguring command

keys.) This panel also reminds you of several commands you

might otherwise overlook because they do not appear on Think—

Tank menus; they can all be found in the reference guide.

Like most maps, the reference card does not aim to be exhaustive. It is designed to orient you and head you in the

right direction. The reference guide is the place to look for

all the commands.

—46—

Page 53

Tutorial

THINKTANK’ S COMMAND SYSTEM

ThinkTank’s command system gives you “the best of both

worlds”; you can always choose to be prompted and guided or to

take a “fast path” to action. Let’s review the two different

ways to select a command, using NEW (again) for illustration.

We will contrast the most deliberate and the quickest way to

create a new headline.

The position of the bar cursor always determines where

the selected command will take effect. Press the ESC key to

return to Top Level (if necessary) and use the arrow keys to

move the bar cursor to PERSONNEL RECORDS.

The Deliberate Method

From Top Level, press “/” to display the Main Command

Menu and use the right arrow key to move the menu cursor to

NEW. On the bottom line of the Command Area you can see:

* the command key for NEW, N, on either end; and

* its brief explanation, ADD A HEADLINE OR PARAGRAPH,

in the middle

While a menu is displayed, pressing RETURN selects the highlighted option, in this case NEW. Do so; ThinkTank displays

the NEW Command Menu.

Suppose we want to create a new headline below the existing ones. Move the menu cursor to DOWN. Now, since we want

the new headline to be three lines down (rather than immediately below the bar cursor headline), type the command

prefix “3” before selecting the DOWN option. A “3” appears on

the right side of the top line of the Command Area. The command prefix tells ThinkTank how far away it should create the

new headline. (You must enter it just before selecting DOWN;

if you enter it before selecting NEW or moving the menu cursor, ThinkTank will “forget” it before creating the new headline.)

—47—

Page 54

ThinkTank Manual

Press RETURN to select DOWN, the highlighted option. As

it did in Chapter 3, ThinkTank opens up space for a new headline below CHRISTMAS LETTER and waits for you to enter one.

Instead of typing a new headline at this point, press the ESC

key to cancel this command.

The deliberate way to select a ThinkTank command is to (1) select a menu, (2) move the

menu cursor to the desired command, and (3)

press RETURN to select the highlighted option.

With this method, you can see a full range of information

about the command, including its command key, its brief explanation, and any command prefix you enter.

This is the best method to use while you are still learning about commands (or whenever you want to examine your options for any reason). You can also use it to study Think—

Tank’s command structure. You can always use the escape valve

(the ESC key) to interrupt or cancel a command, right up to

the last moment.

The Fast Path

Now let’s repeat this process as efficiently as possible. First move the bar cursor back to PERSONNEL RECORDS

and then type “N3D” (N for NEW, 3 for the command prefix, and

D for DOWN). Voila! ThinkTank is waiting for your new headline. Use ESC again to cancel the command.

The “fast path” to a ThinkTank command is to

bypass the menus and use its command keys.

Here is some general advice about selecting commands:

* Command keys always work “inside” menus. For exam-

ple, if the Main Command Menu is displayed, you can

always press N to select NEW and display the NEW Command Menu. The menu cursor doesn’t have to be on

NEW.

—48—

Page 55

Tutorial

* If a command is on the Main Command Menu, its com-

mand key will also work “outside” the menu —— from

the Top Level of ThinkTank. (Exceptions are DELETE

and EXTRA.) For commands on other menus, you must

display the .menu before you use their command keys.

However, you can use command keys to get to the

menu.

For example, from Top Level, the “fast path” to the

COPY command is “//C”. The first slash displays the

Main Command Menu, the second slash displays the

Secondary Command Menu (EXTRA command), and C is the

command key for COPY. You can press the keys as

quickly as you wish; you don’t have to wait for each

menu to appear before pressing the next command key.

* Command prefixes are helpful but never necessary.

If you don’t enter one, ThinkTank assumes its most

likely value (usually one). For example, if you

don’t precede a NEW option with a command prefix,

ThinkTank will create the new headline one position

away.

* The RETURN key works differently “inside” and “outside”

command menus. While a menu is displayed, the RETURN key

selects the highlighted option. From Top Level, you can use

it as a “reading” key (see READ in the reference guide).

At other times, you may be prompted to use the RETURN key

to tell ThinkTank that an entry is satisfactory.

* Executing EXPAND or COLLAPSE from Top Level bypasses

the command menu which is displayed when you select

either of these commands from the Main Command

Menu. The menu lets you choose whether to expand or

collapse headlines, paragraphs, or both. If you

don’t want both, which is what you get from Top

Level, you must go through the menu.

—49—

Page 56

ThinkTank Manual

The Escape Valve

ThinkTank’s command keys let you speed down a “command

tree”; the escape valve lets you speed back up. To illustrate, look at KEYWORD/SEARCH under “Getting Around” on the

reference card. You can use this command to search f or a

word, phrase, or pattern of characters. Suppose you want to

find the word “salary” in the PERSONNEL RECORDS outline.

First move the bar cursor to PERSONNEL RECORDS and then type

KS for KEYWORD/SEARCH (or proceed deliberately if you

prefer). ThinkTank asks for a:

PATTERN’~ TO SEARCH FOR?

Respond by typing:

salary

but then press ESC. (If you press RETURN before ESC, Think—

Tank will execute the SEARCH command.) This example illustrates two general rules:

* you can ESCAPE any time before the final keystroke;

and

* when you cancel a command, ThinkTank normally

returns you to Top Level.

ThinkTank departs from the second rule, however, when you

might reasonably prefer to back up less than all the way to

Top Level. For example, type KX (for KEYWORD/XCHANGE) from

Top Level. This command allows you to replace one word or