Soundtrack

User Manual

K

Apple Computer, Inc.

© 2006 Apple Computer, Inc. All rights reserved.

Under the copyright laws, this manual may not be

copied, in whole or in part, without the written consent

of Apple. Your rights to the software are governed by

the accompanying software license agreement.

The Apple logo is a trademark of Apple Computer, Inc.,

registered in the U.S. and other countries. Use of the

“keyboard” Apple logo (Option-Shift-K) for commercial

purposes without the prior written consent of Apple

may constitute trademark infringement and unfair

competition in violation of federal and state laws.

Every effort has been made to ensure that the

information in this manual is accurate. Apple Computer,

Inc. is not responsible for printing or clerical errors.

Apple Computer, Inc.

1 Infinite Loop

Cupertino, CA 95014-2084

408-996-1010

www.apple.com

Apple, the Apple logo, Final Cut, FireWire, iTunes, Logic,

Mac, Mac OS, Macintosh, QuickTime, and Soundtrack are

trademarks of Apple Computer, Inc., registered in the

U.S. and other countries.

Finder is a trademark of Apple Computer, Inc.

AppleCare is a service mark of Apple Computer, Inc.,

registered in the U.S. and other countries.

Production stills from the films “Koffee House Mayhem”

and “A Sus Ordenes” provided courtesy of Refuge Films.

“Koffee House Mayhem”

“A Sus Ordenes”

http://www.refugefilms.com

Other company and product names mentioned herein

are trademarks of their respective companies. Mention

of third-party products is for informational purposes

only and constitutes neither an endorsement nor a

recommendation. Apple assumes no responsibility with

regard to the performance or use of these products.

© 2005 Jean-Paul Bonjour;

© 2005 Eric Escobar.

1

Contents

Preface 7 An Introduction to Soundtrack

7

What Is Soundtrack?

9

Creating Music with Soundtrack

10

Resources for Learning About Soundtrack

11

Soundtrack Onscreen User Manual

11

Apple Websites

Chapter 1 13 Audio and Music Basics

13

Basic Audio Concepts

18

Basic Music Concepts

Chapter 2 21 Setting Up Your System

21

System Considerations

23

Connecting Audio Equipment

27

Example Hardware Setups

Chapter 3 31 The Soundtrack Interface

32

Project Window

37

Media and Effects Manager

42

Utility Window

Chapter 4 47 Getting Started with Soundtrack

47

Overview

48

Setting Up Your Workspace

51

Playing Projects

57

Locating and Adding Audio Files

66

Previewing Audio Files

69

Using Undo and Redo

70

Using Snap

72

Reconnecting Media Files

73

Setting Soundtrack Preferences

3

Chapter 5 77 Working with Projects

77

Creating and Opening Projects

78

Closing Projects

78

Setting Project Properties

82

Setting the Project Length

82

Saving Projects

83

Adding Audio Files to a Project

85

Viewing and Editing Clip Properties

86

Tracks, Busses, and Outputs

Chapter 6 89 Working in the Timeline

89

Moving Around in the Timeline

94

Working with Tracks, Busses, and Outputs

101

Editing Audio Clips

111

Working with Markers

Chapter 7 115 Working with Video in Soundtrack

11 5

Supported Video File Formats

11 6

Adding a Video to a Project

117

Playing the Video

11 9

Viewing Video Details

12 0

Working with a Video’s Audio

12 0

Using the Time Display and Time Ruler with Video

121

Using Markers with Video

12 4

Removing a Video from a Project

Chapter 8 125 Working with Audio Effects

12 6

Audio Effects Included with Soundtrack

13 4

Working with Effects

141

Working with Effect Presets

Chapter 9 143 Working with Automation

14 3

Working with Envelopes

151

Recording Automation Data

15 3

Working with Timeslices

Chapter 10 159 Recording Audio in Soundtrack

15 9

Getting Ready to Record

15 9

Recording Audio in the Timeline

163

Saving Recorded Clips

4

Contents

Chapter 11 165 Distributing Soundtrack Projects

166

Exporting a Project Mix

167

Exporting Selected Tracks, Busses, and Outputs

168

Exporting to QuickTime

168

Roundtrips Between Final Cut Express and Soundtrack

17 0

Exporting Audio to Final Cut Express

17 0

Distributing a Project and Its Media Files Together

Appendix A 173 Using Apple Loops Utility

17 3

What Is Apple Loops Utility?

174

The Apple Loops Utility Interface

17 9

Opening Files in Apple Loops Utility

18 0

Tagging Files in Apple Loops Utility

181

Working with Transients

183

Saving Changes to Files

18 4

Removing Files from the Assets Drawer

18 4

Apple Loops Utility Preferences

185

Apple Loops Utility Keyboard Shortcuts

Appendix B 189 Soundtrack Keyboard Shortcuts

18 9

General and File

18 9

Windows, Tabs, and Layouts

19 0

Project Playback and Setting the Playhead

191

General Editing

191

Editing Audio Clips in the Timeline

19 2

Adjusting Audio Clips in the Timeline

19 2

Navigating in the Timeline

19 3

Tracks and Markers

Recording

19 4

Appendix C 195 Solutions to Common Problems and Customer Support

19 5

Solutions to Common Problems

19 7

Calling AppleCare Support

Index 19 9

Contents

5

An Introduction to Soundtrack

Soundtrack gives you the tools you need to create

high-quality soundtracks for your video productions.

Music projects that until recently would have required an array of professional studio

equipment can now be completed in a home or project studio, using a personal

computer and readily available resources. A computer with a fast processor and

enough RAM can serve as a workstation for recording, arranging, mixing, and

producing complete music projects that can be played back on the computer, burned

on a CD or DVD, or distributed over the Internet.

For digital video editors, this development allows unprecedented opportunities for

increasing creative control over the music for video projects. Currently, most video

projects either use stock music clips from music libraries or rely on outside music

production houses to create original scores. Now, using digital music tools and

applications, video editors, including those with no musical training or experience, can

create high-quality soundtracks for their video projects with the same computer they

used to assemble and edit their video.

Preface

What Is Soundtrack?

Soundtrack is a music application built specifically for Mac OS X. Using Soundtrack,

even non-musicians can create professional-sounding, royalty-free soundtracks for

Final Cut Express video projects.

Soundtrack lets you build musical arrangements using prerecorded audio files called

loops.

Loops contain rhythmic patterns that you can extend to fill any amount of time.

In a Soundtrack project, you can combine and arrange loops and non-looping audio

files, add professional-quality effects, mix your music in stereo, and export the final mix

to a standard audio file that can be played on any multimedia-equipped computer or

imported into Final Cut Express.

7

Soundtrack includes the following features:

Â

Work in real time:

You can work on Soundtrack projects in real time, adding and editing

audio while the project is playing, and hear the results of your changes immediately.

Â

Use existing loop libraries:

Soundtrack includes a large collection of Apple Loops and

is compatible with a wide variety of existing loop libraries, including those created

for use with Sonic Foundry’s ACID.

Â

Mix loops recorded at different tempos and keys:

Soundtrack automatically matches

loops to the project tempo and key, allowing you to freely combine loops from

different sources in a single project.

Â

Locate and preview files easily:

The Media and Effects Manager, a part of the Soundtrack

interface, provides powerful file browsing and search features, making it easy to locate

loops and one-shots by instrument, genre, mood, or other search criteria.

Â

Add professional-quality effects:

Soundtrack includes high-quality effects plug-ins that

you can use in your projects. You can also install third-party effects in the Audio Units

plug-in format.

Â

Use Final Cut Express scoring markers:

When using Soundtrack to score a video that

includes Final Cut Express scoring markers, Soundtrack recognizes and displays the

scoring markers in the Timeline. You can also add time markers and use them as cue

points to precisely synchronize the music to the action.

Â

Edit nondestructively:

All of the edits you make in Soundtrack are nondestructive,

allowing you to freely try out changes to audio files without altering the original file

and to use the same file in multiple projects.

Â

Record and edit automation:

You can record movements to sliders and other

onscreen controls, play back the automation, and edit it in the Timeline.

Â

Audio recording capability:

You can record audio directly in tracks in the Soundtrack

Timeline, including recording multiple takes.

8 Preface

An Introduction to Soundtrack

Creating Music with Soundtrack

Making use of the advanced digital audio capabilities of Macintosh computers and

Mac OS X, Soundtrack gives you a simple way to create music: After preparing the

video in Final Cut Express, you add media (audio and video files) to tracks in the

Soundtrack Timeline, edit and adjust your audio, and then add effects and automation

to create a final mix that you can export and distribute.

To create your Soundtrack projects, you use prerecorded loops and other audio files.

You can choose the style, tempo, and instrumentation of your music, and arrange

musical events in time, even with no musical experience or training. In short,

Soundtrack gives you greater creative control over the sound of your music than you

would get using stock music libraries or relying on an outside music production facility.

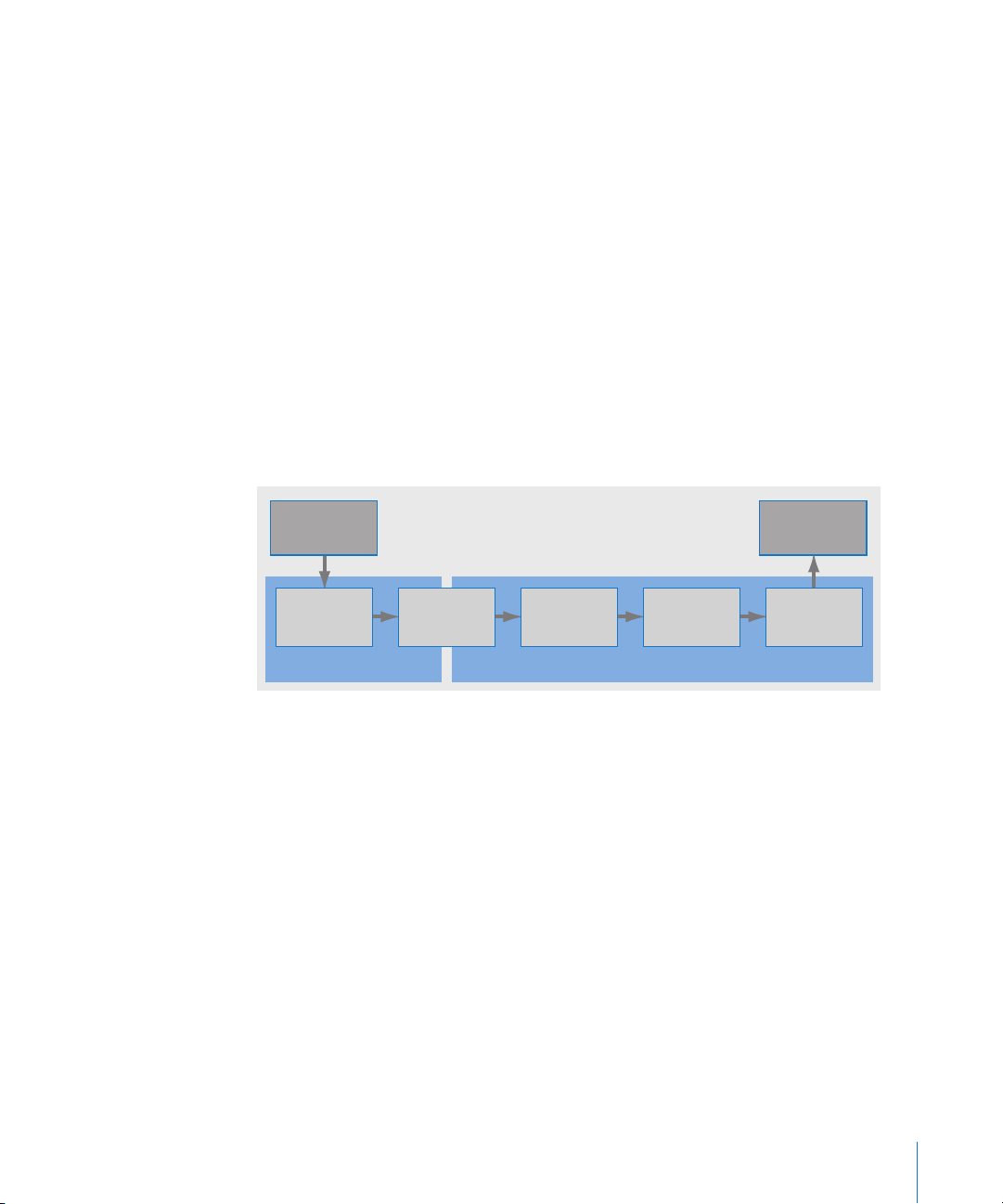

The following steps outline a typical Soundtrack work session. You won’t always

proceed in a strict linear order, and you may choose to overlap some steps. For

example, you may add more audio after starting to build your arrangement in the

Timeline, or you may make changes to the arrangement after you begin mixing.

Prepare

media

Locate and

preview media

Media Manager Project workspace

Creating Music with Soundtrack

Add

media

Build

arrangement

Mix Export

Import to

Final Cut Express

Step 1: Prepare the video

If you’re scoring a video, you’ll want to determine the length of the scenes to be scored,

what mood and style of music are appropriate for the video, and how the music will be

synchronized with the action at specific points. You can prepare the video in

Final Cut Express by adding scoring markers, which appear when you import the video

into Soundtrack.

Step 2: Add media

Once you’re ready, you begin by selecting the audio files you want to use in your

project. You can preview audio files in the Media and Effects Manager, and then add

them to the project Timeline. If you’re scoring a video, you import the video file into

the project so that you can view it as you create your score, and synchronize the music

with the video.

Preface

An Introduction to Soundtrack

9

Step 3: Build the arrangement

You build the arrangement by continuing to add audio clips to the Timeline, moving

and resizing them to create rhythmic patterns and define sections, and editing them in

a variety of ways. You can build drum and rhythm tracks to lay out the form and set the

basic mood, and then layer additional parts over the rhythm tracks to fill out the

arrangement. You can alter the mood and add interest to your music by changing the

instrumentation, changing tempo and key, and adding lead parts or sound effects to

create moments of tension and release.

Step 4: Mix

Once the arrangement is complete, you mix the project. Mixing involves shaping the

overall sound, balancing different parts of the music, and bringing focus to the key

moments in your project. You can further shape the sound of the project by adding

effects (such as EQ, reverb, delay, chorus, and distortion) and using automation to

create dynamic changes. When you finish mixing, you have one or more final mixes

that you can export and distribute.

Step 5: Export and distribute

When your project is complete, you export the final mix as a stereo audio file, which

can be played back on any multimedia-equipped computer. You can also export

individual tracks as audio files. Your exported audio files can be imported into

Final Cut Express or into another audio application such as Logic, burned on a CD or

DVD, and distributed in a variety of ways. You can also export a project containing a

video file as a QuickTime movie file.

Resources for Learning About Soundtrack

This manual describes the Soundtrack interface, commands, and menus, and gives stepby-step instructions for creating Soundtrack projects and for accomplishing specific tasks.

It also includes information on setting up your system and on audio basics. It is designed

to provide the information you need to get up to speed quickly so you can take full

advantage of the intuitive interface and powerful features of Soundtrack.

If you want to start by learning how to set up audio hardware to use with Soundtrack,

read Chapter 2, “Setting Up Your System,” on page 21. If you want to learn about the

features and controls in the Soundtrack interface, read Chapter 3, “The Soundtrack

Interface,” on page 31. If you want to jump right in and start using the application, skip

ahead to Chapter 4, “Getting Started with Soundtrack,” on page 47.

In addition to this manual, Soundtrack provides other sources of support.

10 Preface An Introduction to Soundtrack

Soundtrack Onscreen User Manual

The Soundtrack onscreen user manual allows you to access information directly

onscreen while you’re working in Soundtrack. To view this information, choose Help >

Soundtrack User Manual. The Soundtrack onscreen user manual is a fully hyperlinked

version of the Soundtrack User Manual, enhanced with many features that make

locating information quick and easy.

The homepage provides quick access to various features, including Late-Breaking

News, the index, and the Soundtrack website.

A comprehensive bookmark list allows you to quickly choose what you want to see

and takes you there as soon as you click the link.

In addition to these navigational tools, the Soundtrack onscreen user manual gives you

other means to locate information quickly:

All cross-references in the text are linked. You can click any cross-reference and jump

immediately to that location. Then, you can use the Preview Back button to return to

where you were before you clicked the cross-reference.

The table of contents and index are also linked. If you click an entry in either of these

sections, you jump directly to that section of the user manual.

You can also use the Find dialog to search the text for specific words or a phrase.

Apple Websites

There are a variety of Apple websites that you can visit to find additional information.

Soundtrack Website

For general information and updates, as well as the latest news on Soundtrack, go to:

http://www.apple.com/finalcutexpress/soundtrack.html

Apple Service and Support Website

For software updates and answers to the most frequently asked questions for all Apple

products, including Soundtrack, go to:

http://www.apple.com/support/soundtrack

You’ll also have access to product specifications, reference documentation, and Apple

and third-party product technical articles.

Preface An Introduction to Soundtrack 11

Other Apple Websites

Start at the Apple homepage to find the latest and greatest information about

Apple products:

Â

http://www.apple.com

QuickTime is industry-standard technology for handling video, sound, animation,

graphics, text, music, and 360-degree virtual reality (VR) scenes. QuickTime provides a

high level of performance, compatibility, and quality for delivering digital video. Go to

the QuickTime website for information on the types of media supported, a tour of the

QuickTime interface, specifications, and more:

Â

http://www.apple.com/quicktime

FireWire is one of the fastest peripheral standards ever developed, which makes it great

for use with multimedia peripherals, such as video camcorders and the latest highspeed hard disk drives. Visit this website for information about FireWire technology and

available third-party FireWire products:

Â

http://www.apple.com/firewire

For information about seminars, events, and third-party tools used in web publishing,

design and print, music and audio, desktop movies, digital imaging, and the media

arts, go to:

Â

http://www.apple.com/pro

For resources, stories, and information about projects developed by users in education

using Apple software, including Soundtrack, go to:

Â

http://www.apple.com/education

Go to the Apple Store to buy software, hardware, and accessories direct from Apple

and to find special promotions and deals that include third-party hardware and

software products:

Â

http://www.apple.com/store

12 Preface

An Introduction to Soundtrack

1

Audio and Music Basics

1

You can create professional-sounding music projects in

Soundtrack without any background or training in music.

This chapter describes the basic audio and music concepts

you need to know to get started.

Basic Audio Concepts

In order to understand how you can work with audio files and use the controls, effects,

and envelopes included in Soundtrack, it’s helpful to know some basic terms and

concepts about audio.

Sound Waves

What we hear as sounds are vibrations traveling through the air as

waves move through the air like ripples in a pond, radiating outward from the sound’s

source in a regular pattern of compression and rarefaction.

sound waves.

Sound

Amplitude

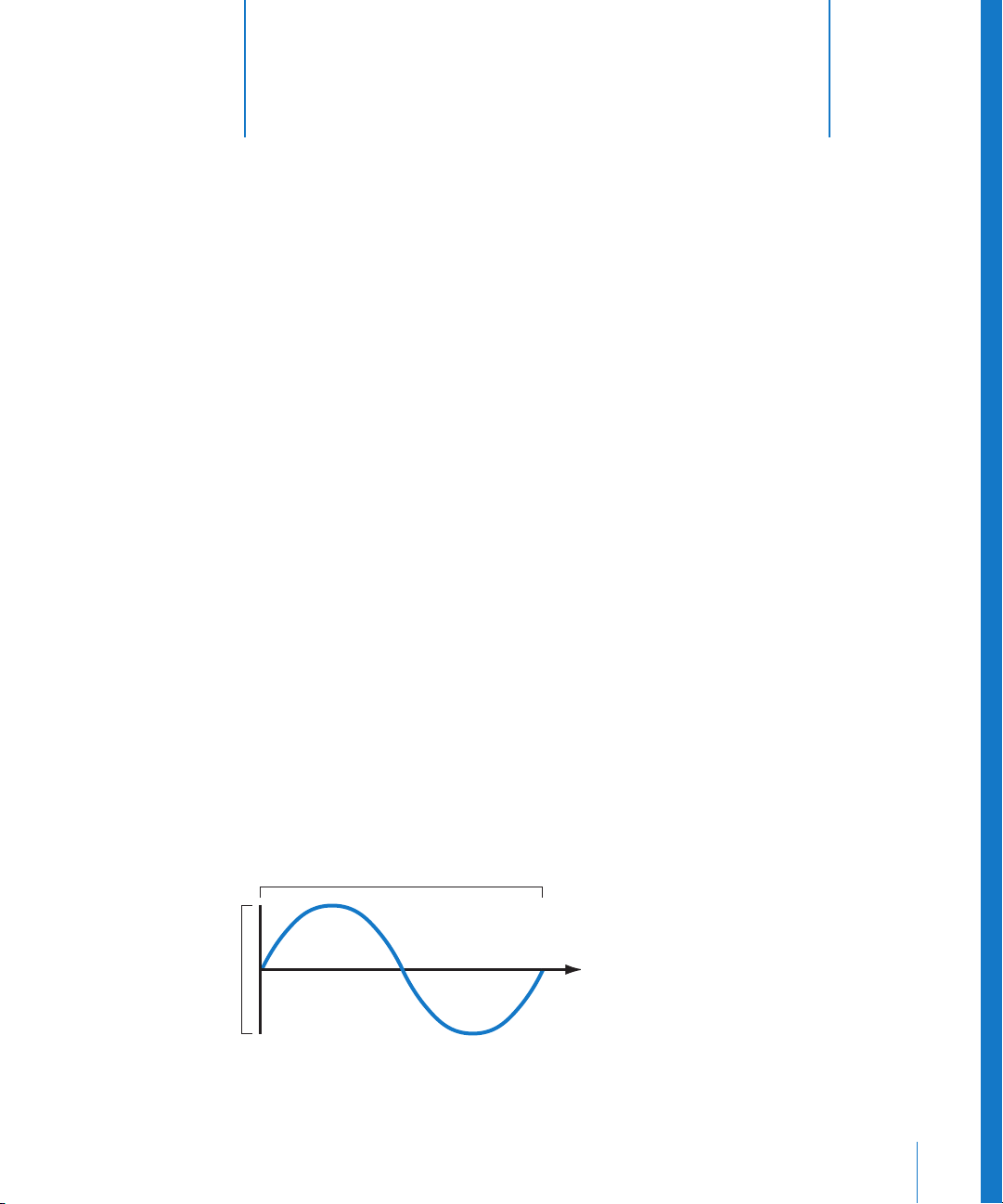

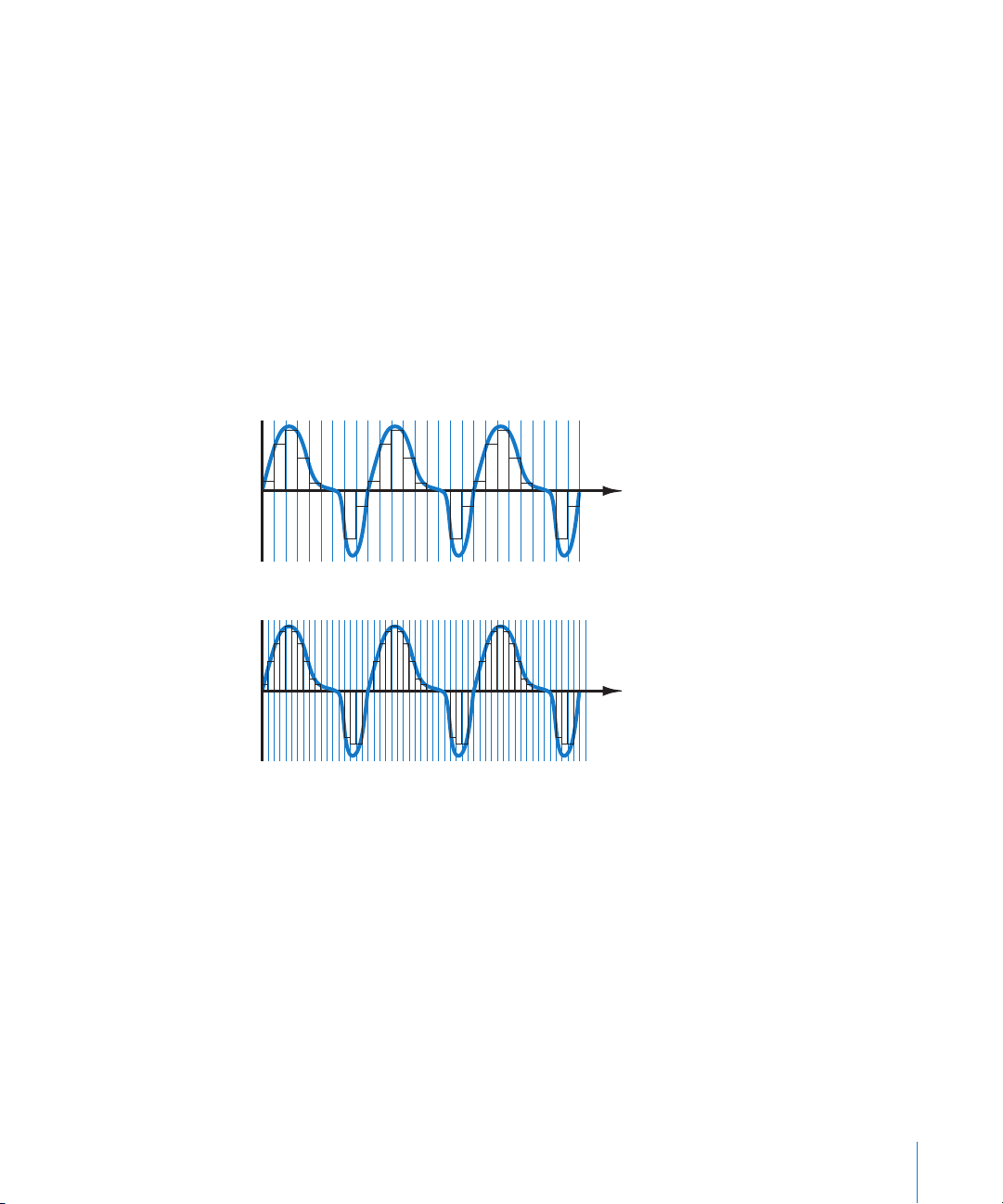

Frequency and Amplitude

The rate at which a sound wave repeats (the time between two peaks of the wave) is

called its

a sound’s frequency as being relatively high (like a flute, a child’s voice, or a train

whistle) or low (like a bass guitar, a man’s voice, or the rumble of a train on the tracks).

The range of frequencies audible to human beings is roughly 20 Hz–20 kilohertz (kHz).

frequency.

Frequency

Frequency is expressed in cycles per second, or Hertz (Hz). We hear

Time

13

The depth or intensity of a sound is called its amplitude, and is expressed in decibels

(dB). We hear amplitude as the volume or loudness of a sound. The range of audible

loudness is roughly 0–130 dB. Higher decibel levels are painful to human hearing.

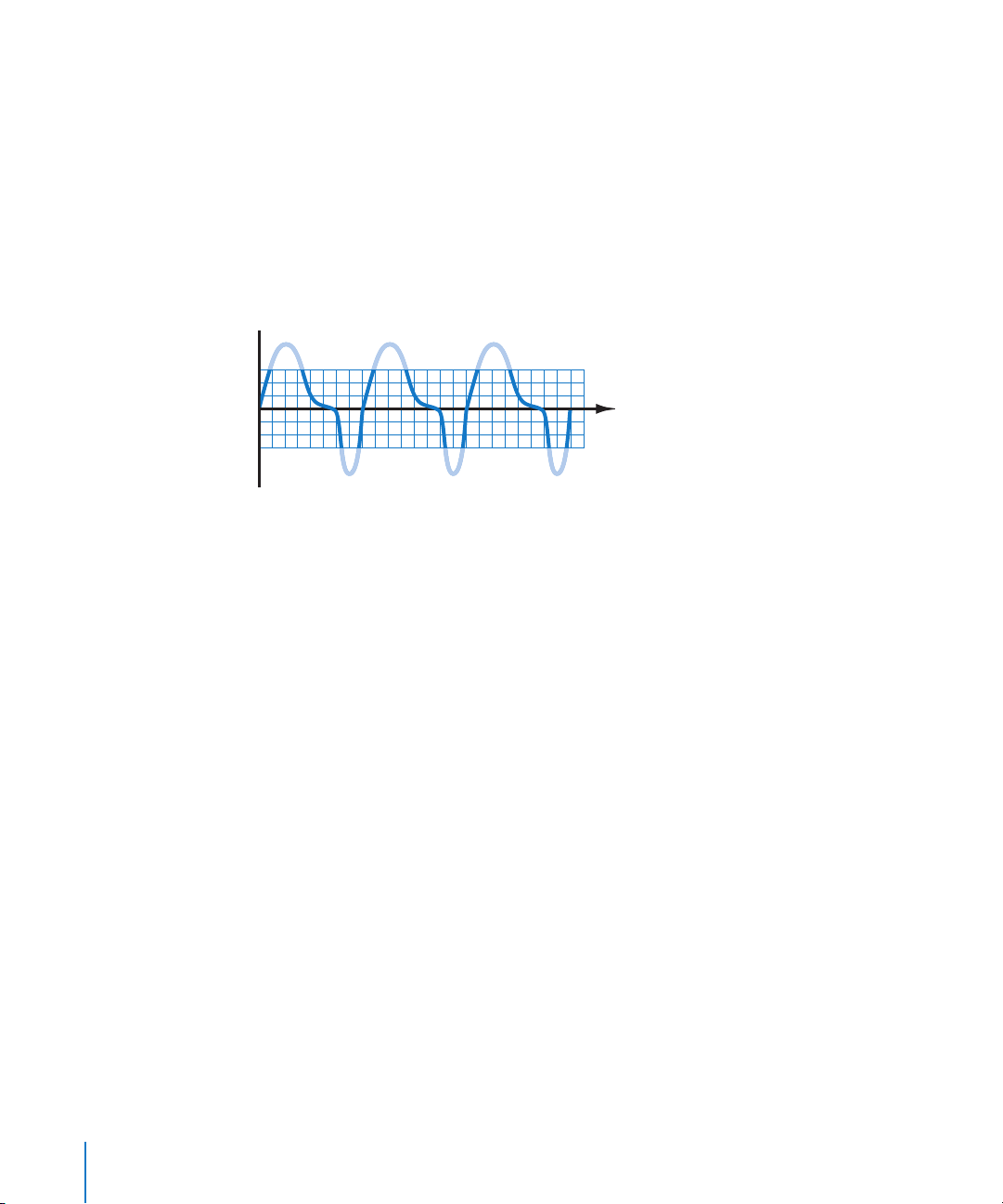

Musical Sounds

Musical sounds typically have a regular frequency, which we hear as the sound’s pitch.

Pitch is expressed using musical notes, such as C, Eb, and F#. What we hear as the pitch

is only the lowest, strongest part of the sound wave, called the fundamental. Every

musical sound also has higher, softer parts called overtones or harmonics, which occur

at regular multiples of the fundamental frequency. We don’t hear the harmonics as

distinct pitches, but rather as the tone color (also called the timbre) of the sound, which

lets us distinguish one instrument or voice from another, even when both are playing

the same pitch. When you turn up the treble on your stereo, or adjust an EQ effect, you

raise the volume of some of the harmonics in the music, but don’t change the

fundamental frequencies.

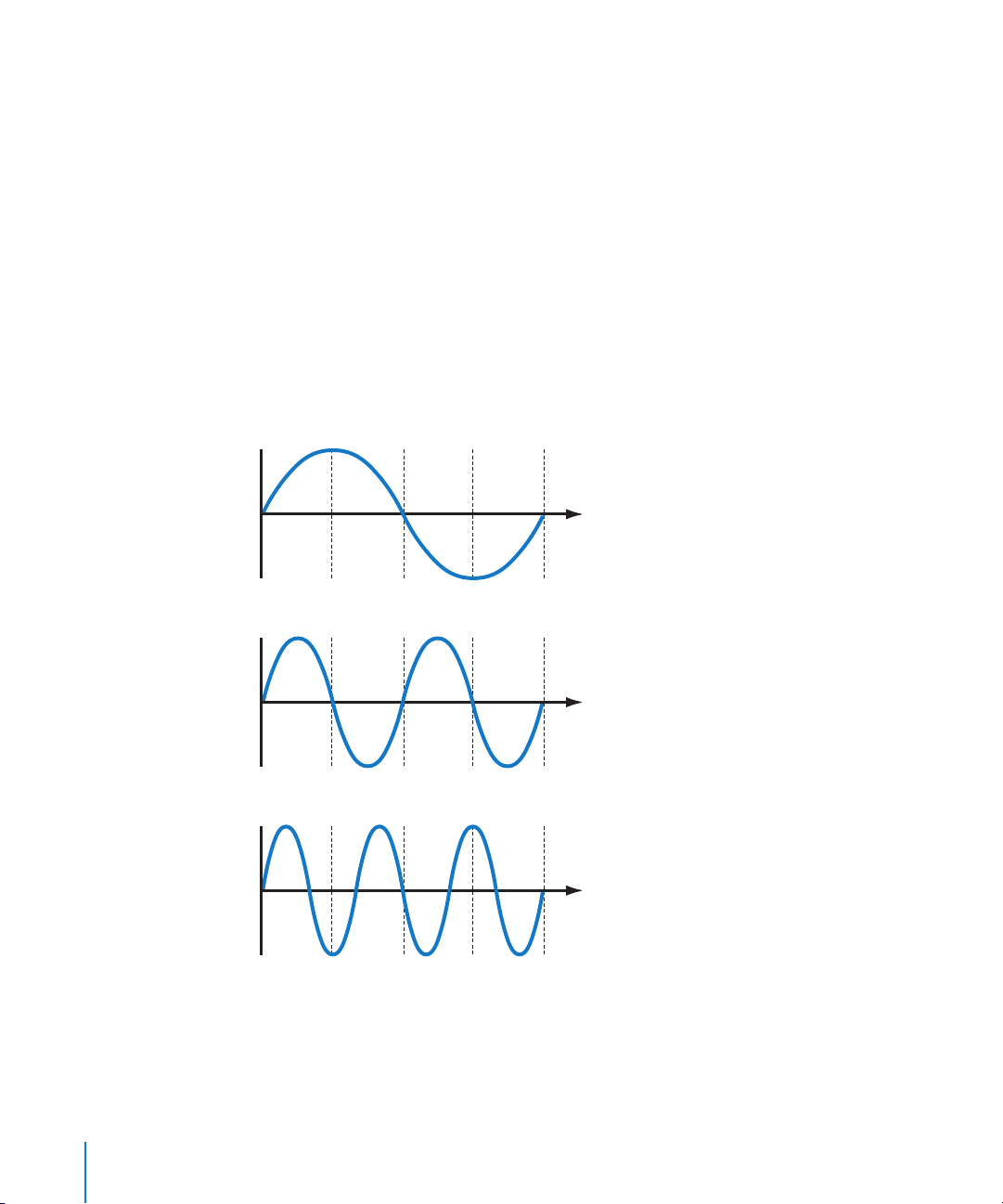

Time

Fundamental

First harmonic

Second harmonic

Time

Time

14 Chapter 1 Audio and Music Basics

Envelopes

Another aspect of sound that helps us to distinguish between instruments and voices

playing the same pitch is a sound’s envelope. Every note played on a musical

instrument has a distinct curve of rising and falling volume over time. Sounds

produced by some instruments, particularly drums and other percussion, start at a high

volume level but quickly decrease to a much lower level, and die away to silence

quickly. Sounds produced by other instruments, for example, a violin or a trumpet, can

be sustained at the same volume level, and can be raised or lowered in volume while

being sustained. This volume curve is called the sound’s envelope, and acts like a

signature to help our ears recognize what instrument is producing the sound.

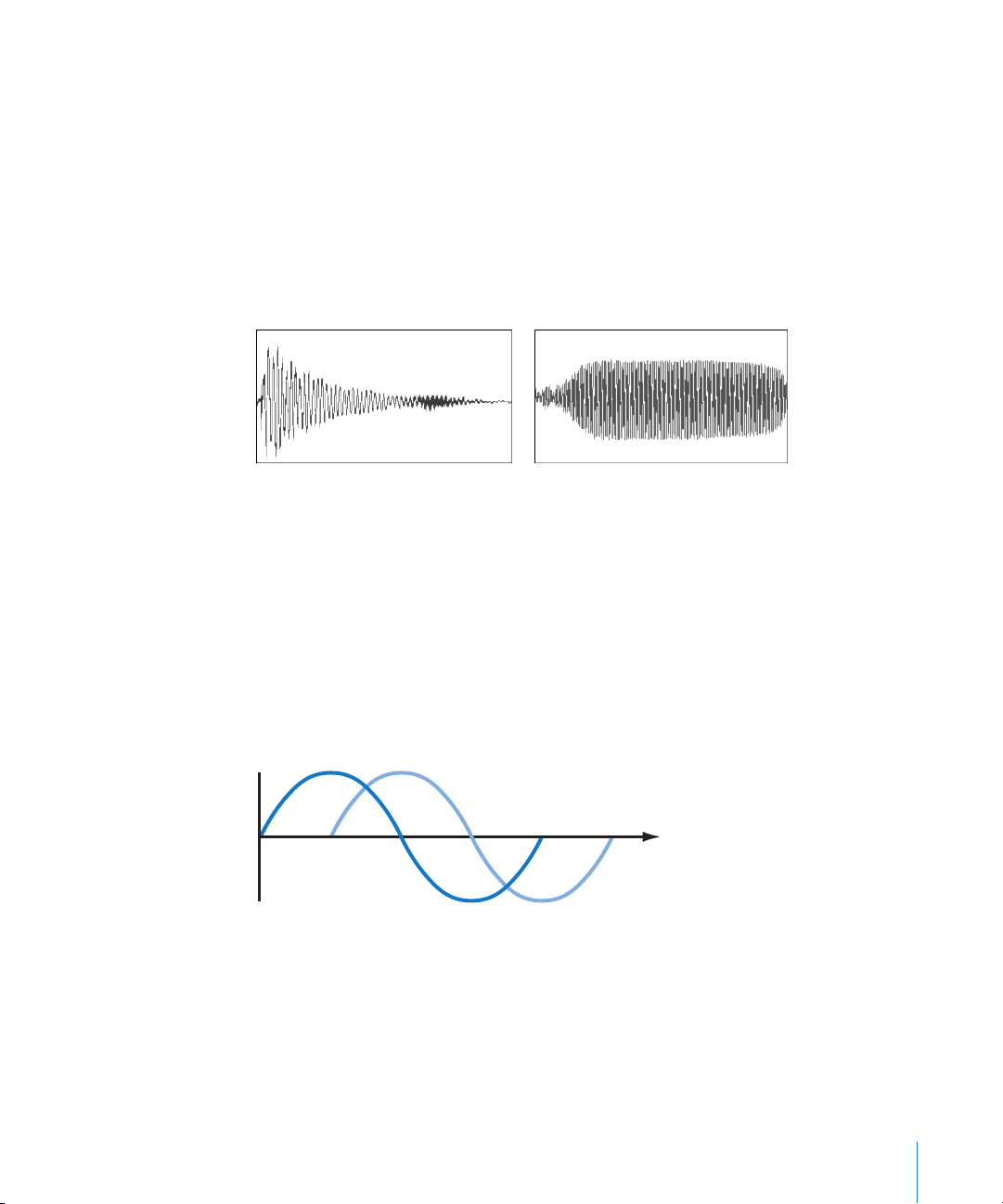

Sustained envelopePercussive envelope

Phase Relationships

When two instruments or voices are playing the same pitch, the sound waves may

have the exact same frequency and amplitude, but the peaks and troughs of the wave

reach our ears, or a microphone recording the sound, at slightly different times. This is

referred to as a difference in the phase of the sound waves. When two sound waves are

completely in phase, the volume of the sound is doubled. When two sound waves are

completely out of phase, they cancel each other out and we hear silence. Certain

effects, such as phase shifters, make use of these properties of phase relationships to

alter the sound of an audio signal.

Time

Recording Sound

When a sound is recorded, the sound waves traveling through the air are converted to

an electrical signal, using a device called a transducer. Sound can be recorded using

either analog or digital recording technology.

Chapter 1 Audio and Music Basics 15

Analog Recording

When a sound is recorded using analog technology, the sound waves are recorded as a

continuous electrical signal. Typically, the vibrations in the air contact the diaphragm of

a microphone, setting the diaphragm in motion. A transducer in the microphone

converts the diaphragm’s motion into an electric signal. The compressed parts of the

sound wave are recorded as positive electrical voltages, and the rarefied parts of the

wave are recorded as negative voltages. The voltage of the recorded signal is an analog

of the wave’s frequencies and their relative amplitudes at any point in time.

Time

Analog recording technology was originally developed using mechanical means to

etch the sound signal directly onto wax cylinders or lacquer disks. Its simplicity, and the

rapid development of electronics during the twentieth century, led to its widespread

use for recording music and for adding sound to motion pictures.

However, analog audio recording is subject to several problems in achieving high-fidelity

reproduction of sound. These include noise, distortion, and loss of quality each time the

audio signal is copied or reproduced.

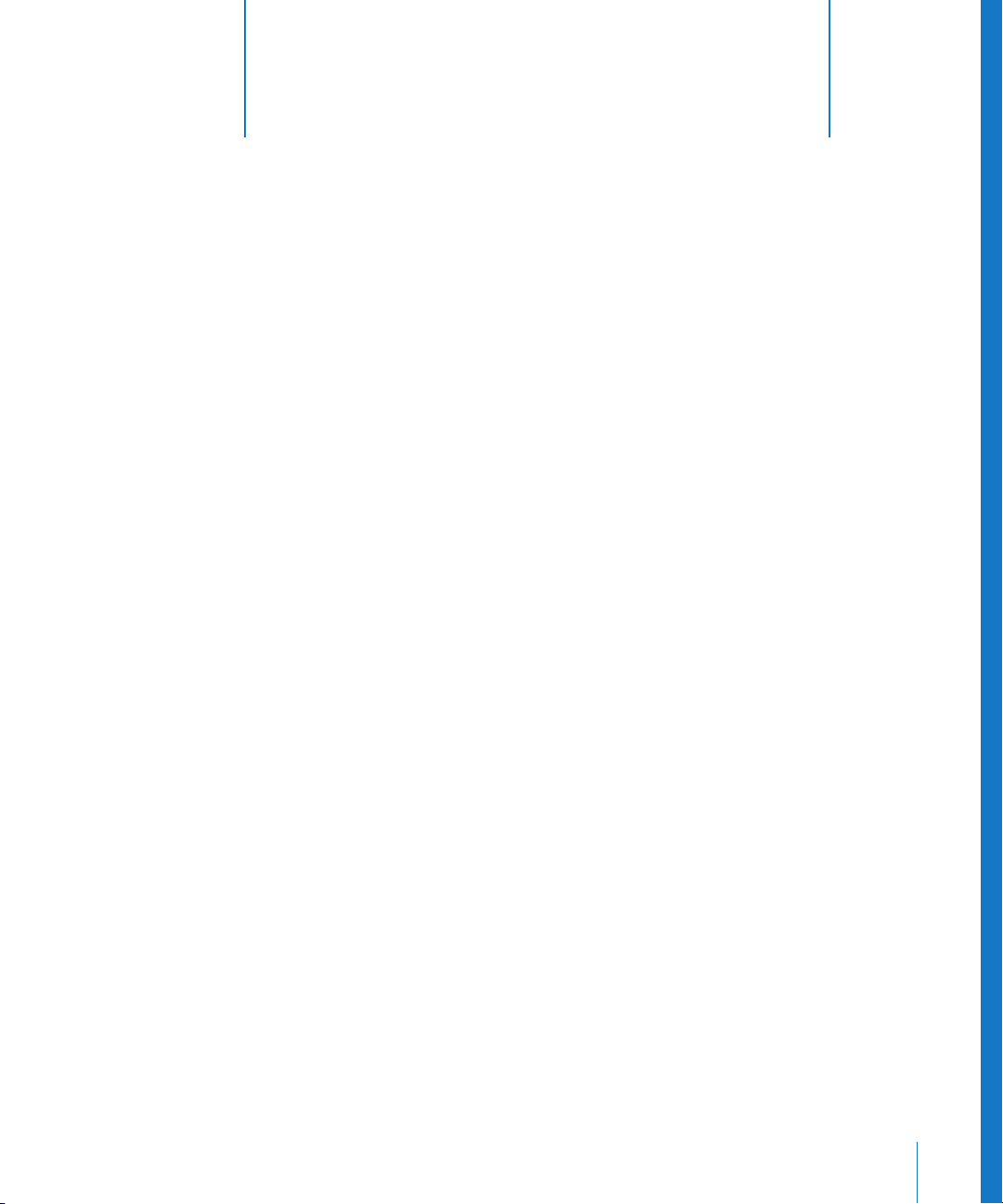

Digital Recording

When a sound is digitally recorded, the sound waves are recorded as a series of samples

onto a hard disk or other digital storage medium. A sample stores the voltages

corresponding to the wave’s frequencies and their relative amplitudes as a series of

binary numbers, or bits. Each sample is like a snapshot of the sound at a particular

instant in time.

Time

16 Chapter 1 Audio and Music Basics

Digital recording technology offers several advantages over analog technology for

recording sound, including lower noise, wider frequency response, and less distortion

(if the sound is recorded at the proper level). In addition, digital recordings can be

reproduced any number of times without any loss of audio quality. These advantages,

combined with the popularity of personal computers, have led to the rapid

development of digital audio as a leading technology for music production.

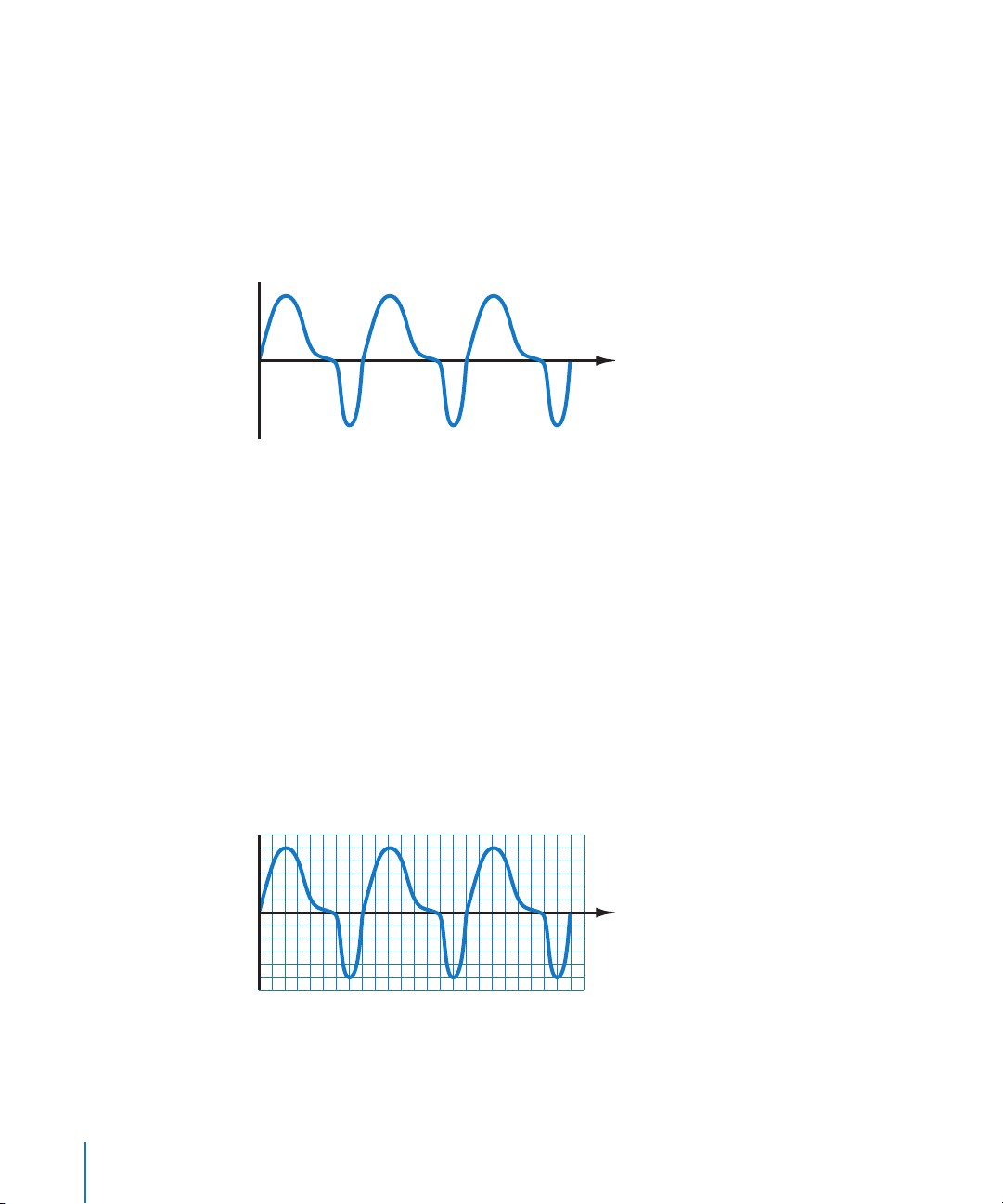

Sample Rate and Bit Depth

The audio quality of any digital recording depends on two factors: the sample rate and

the bit depth used to record the signal. The sample rate is the number of samples

recorded per second. The bit depth is the number of digital bits each sample contains.

Together, these two factors determine the amount of information contained in a digital

audio recording. The higher the sample rate and bit depth of a recording, the more

accurately the recording reproduces the original sound.

Time

Low sample rate

Time

High sample rate

Recording music digitally requires a very high sample rate and bit depth to reproduce

the nuances in the music satisfactorily. The Nyquist theorem states that sounds must be

recorded at no less than double the rate of the highest frequency being sampled to

accurately reproduce the original sound. Audio CDs are recorded at a sample rate of

44.1 kHz and a bit depth of 16 bits (some CDs use a higher 20- or 24-bit depth). Audio

for DVDs is often recorded using a slightly higher sample rate of 48 kHz. Soundtrack

lets you record and play back digital audio files at sample rates of up to 96 kHz, and at

bit depths of up to 24 bits.

Chapter 1 Audio and Music Basics 17

Digital Distortion

To record sound with the widest possible dynamic range, the input level must be set

high enough to capture the complete audio signal. When the input level of the signal is

set too high, however, the signal exceeds the maximum level that can be sampled or

reproduced accurately, resulting in digital distortion. Digital distortion is defined for

most digital audio applications, including Soundtrack, as any time the signal rises

above 0 dB. Even a single sample above 0 dB can produce noticeable distortion, which

you hear as a sharp crackling sound in the audio output. Digital distortion is nearly

always undesirable, and Soundtrack includes audio meters and other controls so that

you can identify and remove distortion from your projects.

Time

Basic Music Concepts

You can create professional-sounding music projects in Soundtrack without any

background or training in music. In order to understand how the different elements in

a piece of music work together, and how you can use them to plan and create projects

in Soundtrack, it’s helpful to know some basic concepts about music.

Rhythm and Tempo

Rhythm is the most essential of all elements of music. People respond to rhythm

unconsciously by tapping their feet or moving their bodies in time to the rhythm.

When the rhythm in a piece of music changes, most people feel a difference in the

character or mood of the music right away.

Rhythm defines the sense of time in music by creating a recurring pulse. The feeling of

rhythmic pulse in music can be subtle (for example, in classical music and some

electronic music), or it can dominate all other elements of the music (as in tribal

drumming or in dance music).

There are usually several layers of rhythm occurring simultaneously in a piece of music.

The strongest rhythmic layer occurs in regular units called measures. Falling within each

measure are a number of softer pulses called beats. The beat that coincides with the

beginning of the measure is called the downbeat. There can also be more subtle pulses

between beats. In the Soundtrack interface, the Beat ruler and Beat display show the

division of musical time into measures, beats, and beat divisions.

18 Chapter 1 Audio and Music Basics

Musicians use the concept of time signature to express the relationship between measures

and beats. The first, or upper, number of the time signature indicates the number of beats

in each measure, and the second, or lower, number indicates the basic beat value.

The rate at which beats occur in a piece of music is called its tempo. Tempo is measured

in beats per minute (bpm). Music with an active or upbeat feeling tends to use a faster

tempo, while music with a more relaxed or inward feeling tends to use a slower tempo.

You can control the tempo of a Soundtrack project, and change the tempo during the

course of a project.

Melody

Melody is often the most recognizable or memorable part of a piece of music. It’s the

part of the music you walk away singing, whistling, or humming, and the part you

usually think of when trying to identify the music or tell someone about it.

A melody is an arrangement of musical notes in a specific rhythmic pattern. Melodies

establish the character of a piece of music, and immediately evoke a feeling or mood.

In Soundtrack projects, you work with prerecorded loops, some of which contain

melodies or melodic phrases. If you sing or play an instrument, you can also record

original melodies in Soundtrack. Whether you use existing loops or your own

recordings, the most important thing to consider is whether a melody you want to use

is appropriate for the style and feeling of a particular project.

Harmony and Key

Harmony occurs when several musical notes are played simultaneously, typically in

groups of three or more notes called chords. The harmony of a piece of music is often

played by rhythm or accompanying instruments, and works with the rhythm and

melody to help establish the feeling of the music. As a piece of music progresses, the

harmony changes, often at the beginning of a measure or on a strong beat, creating

chord progressions that help give the music a sense of forward motion.

Most music makes use of groups of related notes called musical scales as the basis for

both melody and harmony. The most common scales are the major scale and the minor

scale. A scale centered around a particular musical pitch is called the key of a piece, and

the central note is called the root note or tonic of that key. You can set the key of a

Soundtrack project, and add key changes over the course of a project.

Some loops and one-shots you’ll use in your projects contain recordings with

harmonies and chords. Soundtrack automatically matches the key of each audio file

you add to a project to the project’s key. You can also transpose individual loops to

create chord progressions and achieve other harmonic effects.

Chapter 1 Audio and Music Basics 19

Instrumentation

The instruments used in any piece of music help define the style and the character of

the music. Because each instrument adds its own particular range of musical

expression to the piece, the choice of instrumentation is a crucial one in creating your

projects. If you’re working in a particular style, you should always consider whether an

instrument fits the sound of that style. If you’re going for something original, you can

try combining instruments in a unique or unusual way.

The art of arranging involves choosing the right instrumentation, and using changes in

the instrumentation over the course of the piece to create musical interest and drama.

The arrangement becomes an integral part of the character and expression of the music.

Musical Patterns and Form

Most styles of music engage their audience by building up repeating patterns, then

breaking or changing them after a number of repetitions. Larger musical compositions

are created out of a series of related patterns.

Musical patterns typically occur in groups of two or four, and changes from one pattern

to another typically occur at multiples of four. The form of a popular song provides a

simple example: Many pop songs consist of a short introduction followed by two main

sections, the verse and the chorus. The verse and chorus alternate several times, with

the melody either sung or played by the lead instruments.

The introduction typically lasts 8 or 16 measures; each verse lasts 16 or 32 measures,

and the chorus lasts for another 16 or 32 measures. In both the verse and chorus, the

harmony may change at the beginning of every measure, or every two or four

measures. Often the last chorus is repeated several times for a coda or “outro.”

Most styles of contemporary music are based to some degree on song form. You can

easily create projects based on this form, using loops with drum beats and rhythmic

patterns to define each section of the form. Each repetition of the verse and chorus

sections can be set off using loops with vocals, or with varying lead or solo parts. You

can scale the length of the piece to fill a specific amount of time, such as the length of

a movie you want to score, by either adjusting the tempo or changing the number of

times the final section repeats.

Another typical feature of song-based music is that there is often a signal at the end of

each pattern that tells the audience that the pattern is about to change. Often this

occurs in the drums or rhythm section parts. For example, the drums may repeat the

same pattern for seven measures, but introduce slight changes in the eighth measure

that energize the music and signal that a new pattern is about to start. Musicians call

these signals fills, and loop libraries often contain several fills meant to be used with a

looped drum pattern.

20 Chapter 1 Audio and Music Basics

2 Setting Up Your System

2

The way you set up your system depends on the audio

equipment you plan to use.

You can use your computer’s speaker or headphone jack to monitor the audio output

from Soundtrack. For better results, you may want to connect external monitors or

speakers to your system, so that you can monitor the audio output at a higher level of

quality. You may want to connect other external audio equipment such as an audio

interface or a mixer, particularly if you plan to record your own audio in Soundtrack.

For information on system and hardware requirements, see the Read Before You

Install document on the installation DVD.

For information on installing the software, see the Installing Your Software booklet.

System Considerations

To achieve the most effective results, you should consider the following issues when

setting up your system.

Processor Speed and RAM

Digital audio files require intensive processing by your computer. If you plan to work on

longer or more complex projects, or use multiple effects plug-ins in your projects, a

computer with a faster processor can facilitate your productivity.

Soundtrack is optimized for use with computers that have a multiprocessor

architecture. Working with Soundtrack projects on a multiprocessor-equipped

computer can make your workflow more efficient, especially when creating longer or

more complex projects.

If you plan to work on large projects, it’s useful to have extra random-access memory,

or RAM, installed in your computer. Additional RAM allows you to play back more files

simultaneously, use a greater number of effects plug-ins, and keep several multimedia

applications open at the same time.

21

Hard Disk Space

It’s also a good idea to have a large hard disk with plenty of available space to store the

media (audio and video) files you use with Soundtrack. As you work with the

application, you’ll likely want to acquire a large collection of sounds to use in your

Soundtrack projects. You can use audio files stored on a CD-ROM disc or other external

media, but playback performance may not be as good as when the audio files are

installed on a local hard disk, especially when using a large number of files.

If you store media files on an external hard disk, make sure the disk has a fast enough

seek time and a high enough sustained data transfer rate for use with multimedia files.

Consult the manufacturer’s specifications.

Dedicated Hard Disk

If you plan to record your own audio in Soundtrack, remember that every minute of

stereo digital audio (recorded using a 44.1 kHz sample rate and 16-bit depth) requires

roughly 10 MB of hard disk space. If you plan to record large amounts of audio, you

may want to record to a dedicated hard disk.

Setting the Audio Input and Output

By default, Soundtrack uses the input and output devices set in your computer’s

System Preferences for audio input and output. You can set the default input and

output (for monitoring) devices for Soundtrack in the Recording pane of the

Soundtrack Preferences window, and change them for individual recording sessions in

the Recording tab. For information on changing the default input and output devices

Soundtrack uses, see “Setting Soundtrack Preferences” on page 73.

Adding Audio Units Plug-Ins to Your Computer

Soundtrack includes an extensive set of professional-quality effects plug-ins. Soundtrack

uses effects in the Audio Units plug-in format, the native plug-in format of Mac OS X.

Audio Units plug-ins are also available from third-party manufacturers. When adding

third-party effects to your computer, be sure to read the documentation, including any

Read Me and installation files, that came with the plug-in. Supported Audio Units

effects plug-ins appear in the Effects window under the manufacturer’s name.

Soundtrack does not support VST, ASIO, MAS, or RTAS effects plug-ins.

22 Chapter 2 Setting Up Your System

Connecting Audio Equipment

You can use a variety of audio equipment with Soundtrack for both recording and

playback. For information on connecting a specific piece of equipment to your

computer, read the documentation that came with the equipment.

When using external audio devices, it’s a good idea to connect them before

opening Soundtrack.

Soundtrack does not support video input from devices such as camcorders or

videocassette decks.

Audio Interfaces

You can connect an audio interface to your computer, and then connect microphones and

musical instruments to the audio interface for recording. You can also connect output

devices, such as monitors or speakers, a mixer, or an amplifier to the audio interface.

When choosing an audio interface, check the manufacturer’s specifications to make

sure the interface is compatible with Mac OS X v10.4 (Tiger). Some audio interfaces

require driver software, while others are supported without the need for a driver. If the

device requires a driver, make sure an up-to-date driver is included with the device, or

is available from the manufacturer.

All digital audio interfaces can be susceptible to latency, a noticeable delay between

the time the audio signal is produced and the time you hear it. When connecting an

audio interface, you should connect the interface directly to the computer, rather than

connecting it through a hub or daisy-chaining it through another device. Connecting

an audio interface through a hub or an intermediary device can cause an unacceptable

amount of latency, particularly with slower protocols such as USB.

Soundtrack supports input from digital audio interfaces up to a maximum sample rate of

96 kHz and a maximum bit depth of 24 bits. If you connect an interface that uses sample

rates or bit depths outside the range supported by Soundtrack, an alert message appears,

telling you that data from the audio interface is not compatible with the application.

Chapter 2 Setting Up Your System 23

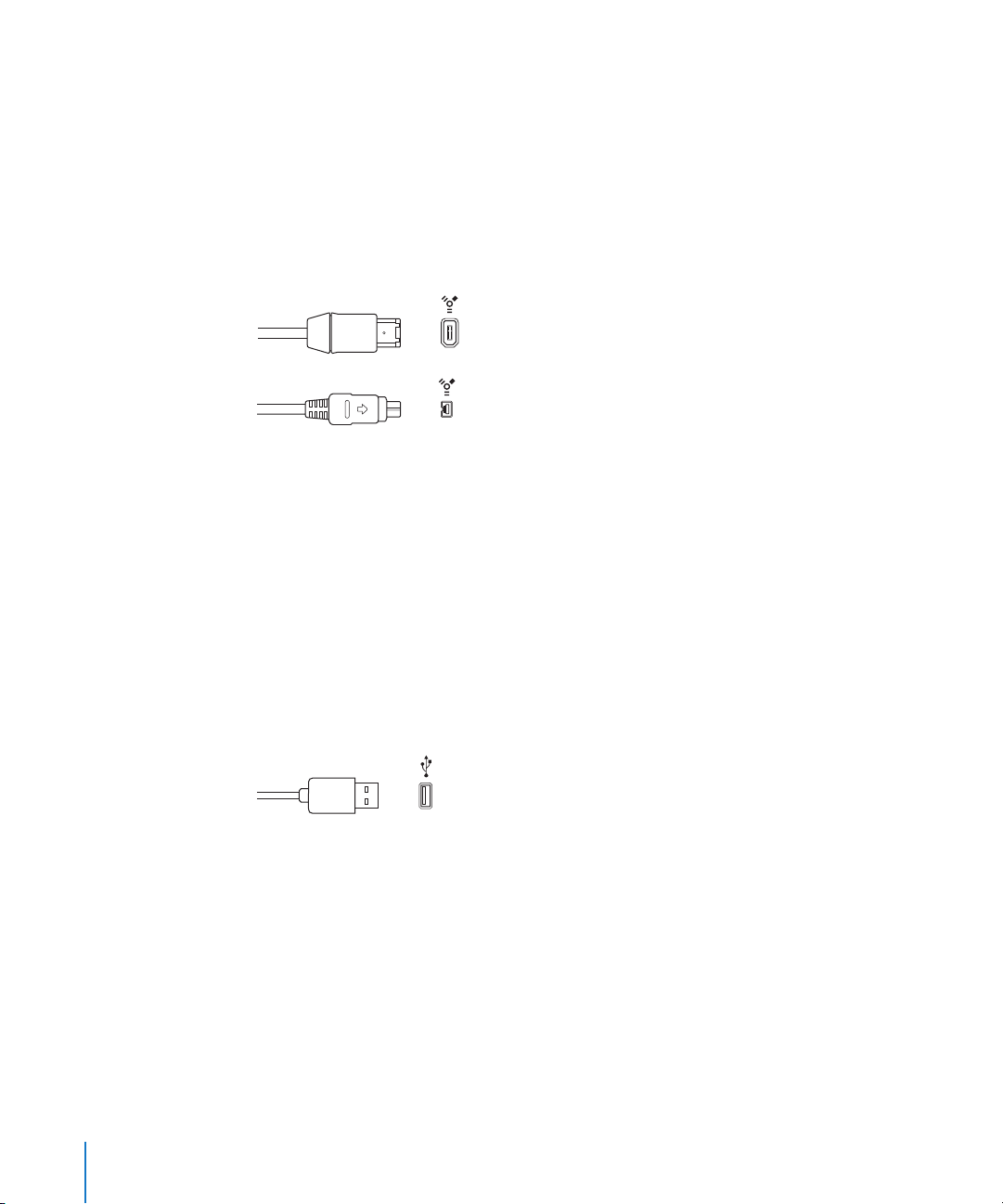

FireWire (IEEE 1394)

FireWire is a professional and consumer standard for both audio and video equipment.

The combination of fast data-transfer rates, high storage capacities, and plug-and-play

connection makes FireWire an attractive choice for working with digital audio files.

FireWire is included on all current Macintosh computers, and a number of FireWire

audio interfaces are available.

There are two kinds of FireWire connectors: a 4-pin connector (typically found on

video equipment) and a 6-pin connector (used for computer and audio equipment).

FireWire 400 (6-pin)

(Sometimes labeled iLINK)

FireWire 400 (4-pin)

USB (Universal Serial Bus)

USB is a consumer standard used on computer peripherals and other devices. USB

offers a lower data-transfer rate than FireWire, but supports plug-and-play operation

and the ability to connect several devices in sequence (daisy-chaining). Some USB

devices draw their power over the USB cable, while others require a separate power

connection. USB is included on all current Macintosh computers.

There are two kinds of USB connectors: an A connector, typically used to connect a

device to a USB hub, and a B connector, typically used to connect devices together, and

also to connect a device to a computer. USB audio interfaces should always be directly

connected to your computer, not connected via a hub or to the computer’s display,

keyboard, or another peripheral.

USB (Universal Serial Bus)

PCI (Peripheral Connect Interface)

PCI interfaces, unlike FireWire and USB interfaces, require that you install a dedicated

sound card in your computer. PCI provides high bandwidth and fast data-transfer rates,

allowing you to record and play back large numbers of files at the highest possible

sample rates and bit depths.

24 Chapter 2 Setting Up Your System

PCMCIA

PCMCIA is a consumer standard for connecting devices to a laptop computer. PCMCIA

provides a lower data-transfer rate than FireWire or USB, but provides a compact,

affordable solution for connecting an audio interface to your computer, while keeping

your USB and FireWire ports available for other devices. Most current Macintosh laptop

computers support PCMCIA connections via a built-in card slot.

Audio Cabling

There are several types of audio cables and connectors used on professional and

consumer audio equipment, at a range of prices and levels of quality. When connecting

microphones and musical instruments to an audio interface or a mixer, make sure the

interface has the proper input jacks for the type of connectors and cables you plan to use.

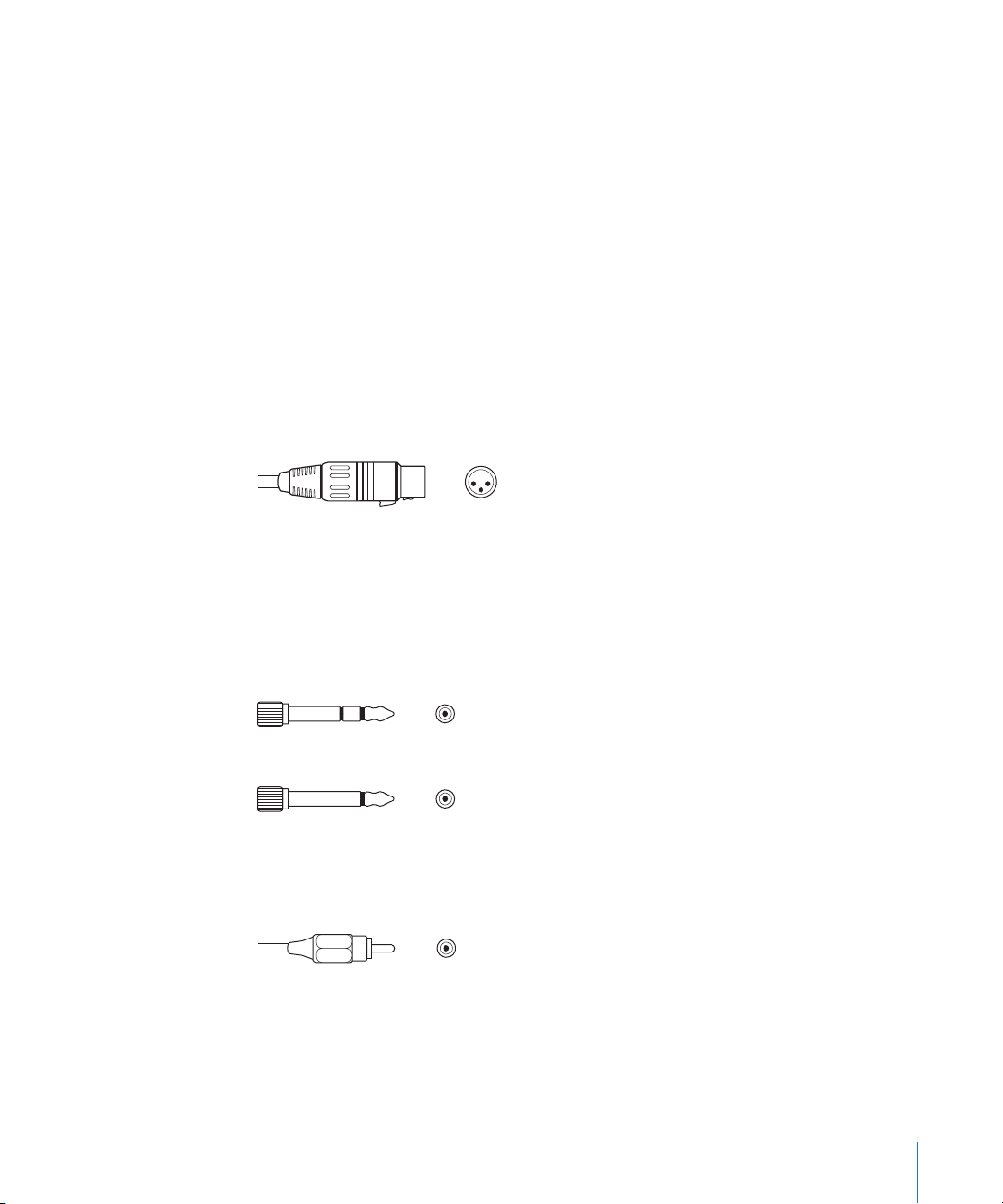

XLR

XLR cables and connectors are used on professional-quality microphones, monitors, and

other musical equipment. They provide a high-quality, balanced signal at +4 dB level.

XLR connector (balanced)

1/4-Inch Audio

1/4-inch connectors (sometimes called “phone plugs”) are used on a wide variety of

professional and consumer musical equipment, including musical instruments and

amplifiers, speakers, and external effects devices. They can be either balanced (+4 dB)

or unbalanced (–10 dB). Some devices require Tip-Ring-Sleeve (TRS) connectors to

transfer the audio signal.

1/4-inch Tip-Ring Sleeve (TRS) connector

1/4-inch Tip-Ring (TR) connector

RCA

RCA connectors are used on consumer audio equipment such as home stereo systems

and videocassette recorders.

RCA connector (unbalanced)

Chapter 2 Setting Up Your System 25

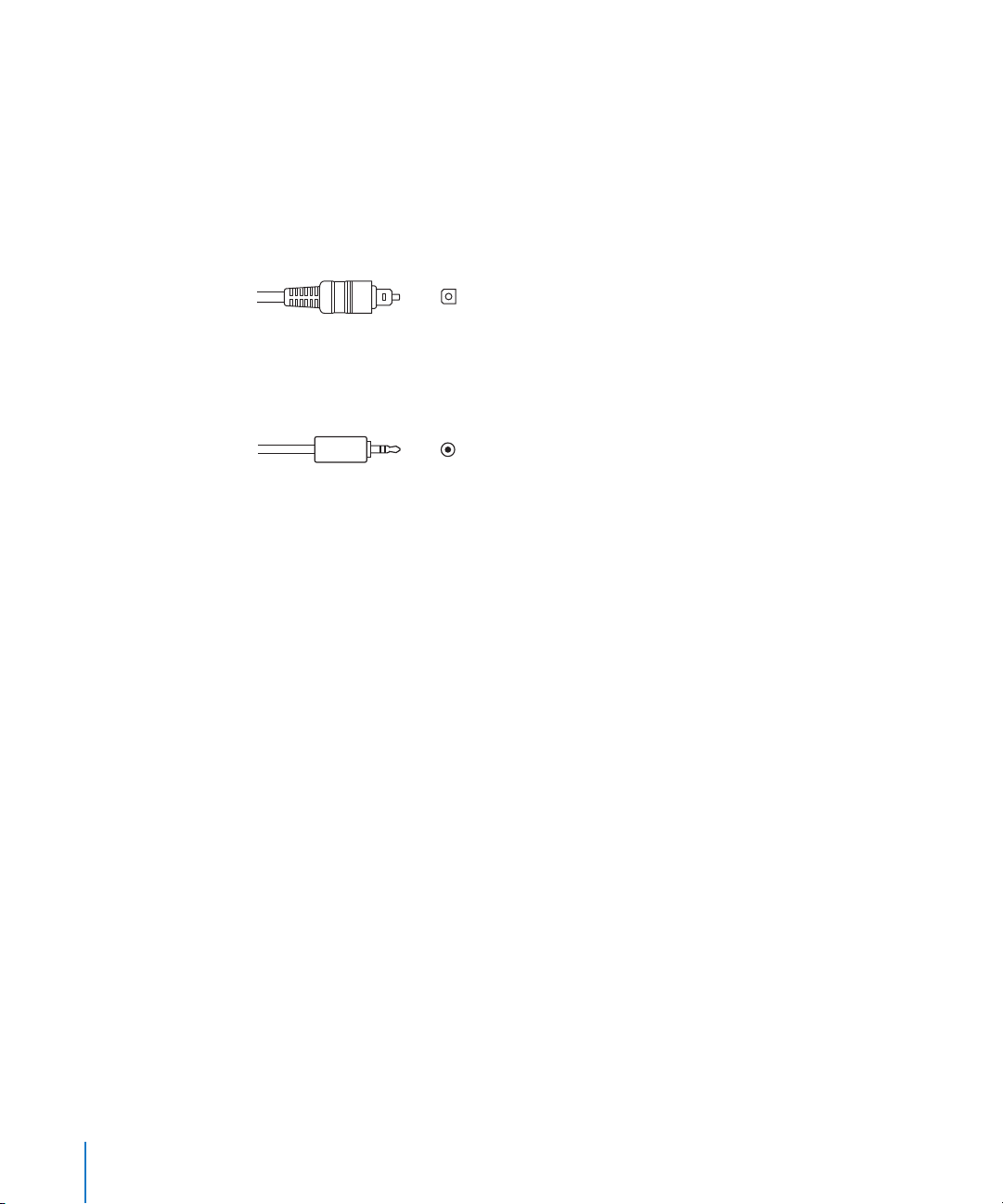

Optical Digital (AES-EBU and S/PDIF)

AES-EBU and S/PDIF are both used to provide an optical digital connection to

professional and consumer audio equipment, including audio interfaces, DAT (digital

audio tape) machines, and hardware samplers. Both carry a stereo digital signal. AESEBU is balanced, and has an operating level of 5 volts, while S/PDIF is unbalanced and

has an operating level of roughly 1/2 volt. There are adapter cables available to convert

between the two protocols. S/PDIF carries additional information with the audio signal,

including SCMS copy-protection information.

S/PIDF optical digital connector

1/8-Inch Miniplug

Miniplug connectors are used for audio input and output to computers and on some

consumer electronic devices, particularly portable ones.

Stereo miniplug connector (unbalanced)

Audio Output

Being able to monitor the audio output of your projects at a high level of quality is

crucial to achieving professional results. In general, you should use the best output

equipment your budget allows.

Speakers and Monitors

You can play back audio through your computer’s speakers or headphone jack, but the

audio output may not be high enough for you to evaluate your music at a professional

level of quality. Connecting external speakers or monitors to your system allows you to

hear the audio output with greater fidelity and a wider dynamic range. In general, you

should use the highest-quality speakers or monitors you can afford in order to hear

your projects at the highest level of audio quality.

For detailed information about connecting external speakers to your audio interface,

see the documentation that came with the speakers.

26 Chapter 2 Setting Up Your System

Amplifiers

If you are recording audio from microphones, and are not running the microphone’s

signal through a mixer with a microphone pre-amplifier, you need to connect an

amplifier to boost the microphone’s signal before sending it to the computer. If you are

connecting monitors or speakers that are not self-powered, you also need to connect

them through an amplifier.

Mixers

Connecting a mixer to your system allows you to record audio from multiple

microphones or instruments simultaneously, to play back the output from your

computer through connected monitors or speakers, and to control the volume levels of

both the audio input and output. Professional-quality mixers have a number of

additional features, including equalization (EQ) controls, auxiliary sends and returns for

adding external effects, and separate monitor and mix level controls. Mixers may also

include inboard pre-amplification for microphones, making the use of a separate

amplifier unnecessary.

Example Hardware Setups

The following sections provide several examples of different hardware setups.

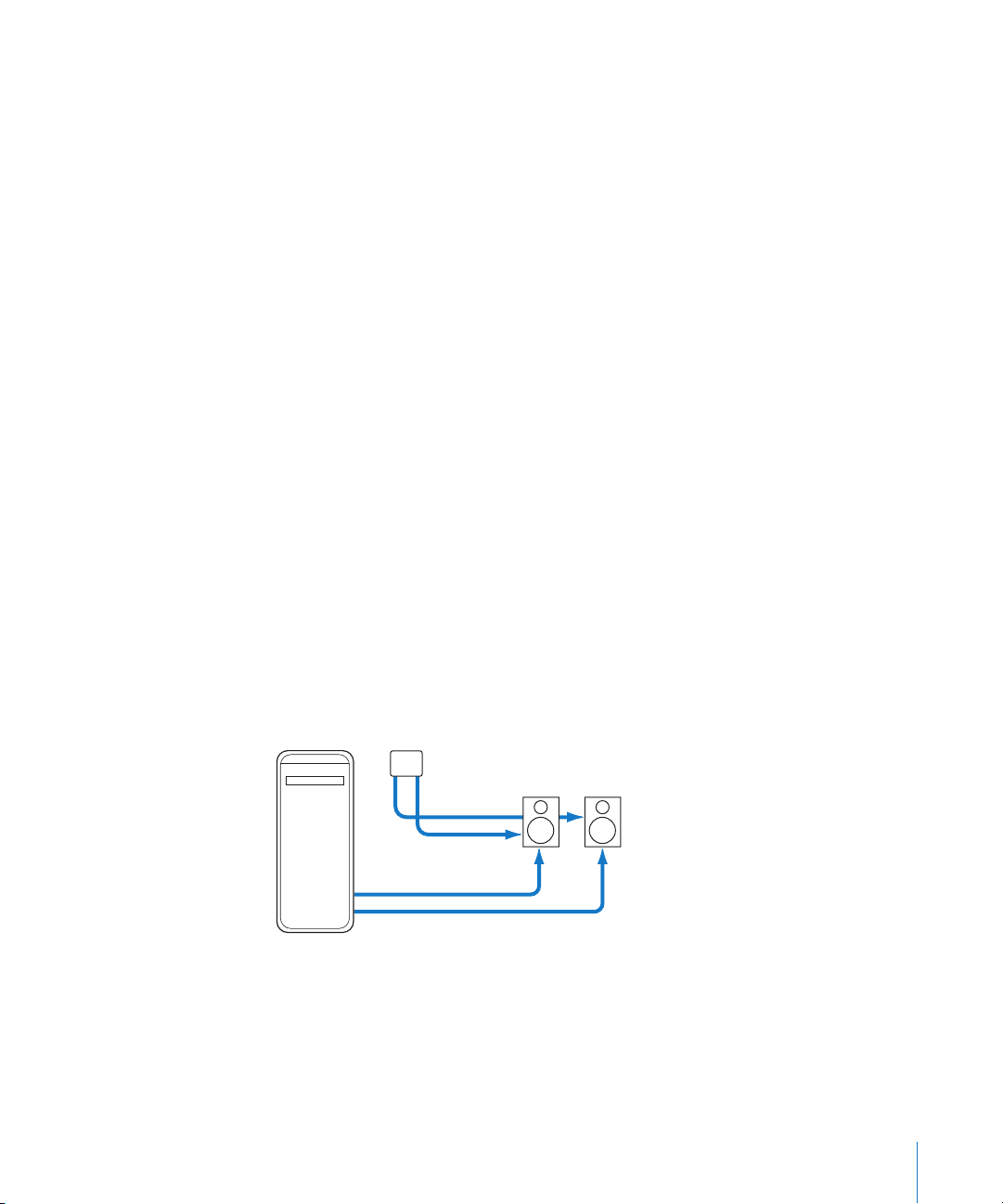

Setting Up a System Using Powered Speakers

With this setup, you can monitor the audio output through a set of connected

powered speakers.

This setup uses the following equipment:

Your computer and display

A set of powered speakers, including speaker wire and a power adaptor

Speakers

Power cables

Speaker cables

Computer

Chapter 2 Setting Up Your System 27

Setting Up a System Using a USB Audio Interface

With this setup, you can record audio input from microphones and musical

instruments, and monitor audio output, through a USB audio interface.

This setup uses the following equipment:

Your computer and display

USB audio interface (from 2 to 8 channels) with USB cable to connect to your computer

Microphone

Musical instruments (guitar, bass, and keyboard)

Cables to connect microphones and instruments to the audio interface

Set of monitors or speakers

Monitors

Microphone

Speaker

Computer

USB

cable

cables

Computer

Audio interface

Instrument

28 Chapter 2 Setting Up Your System

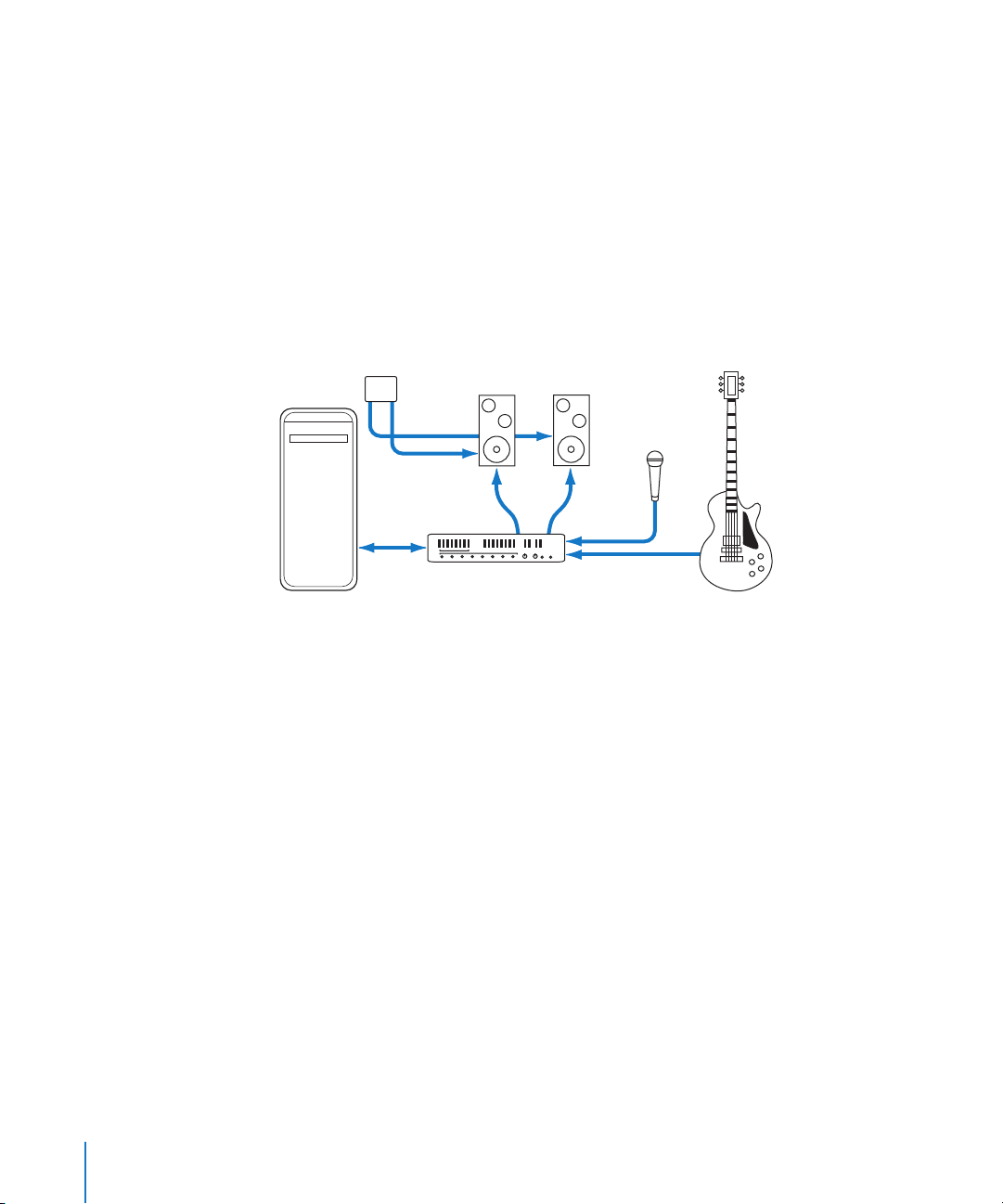

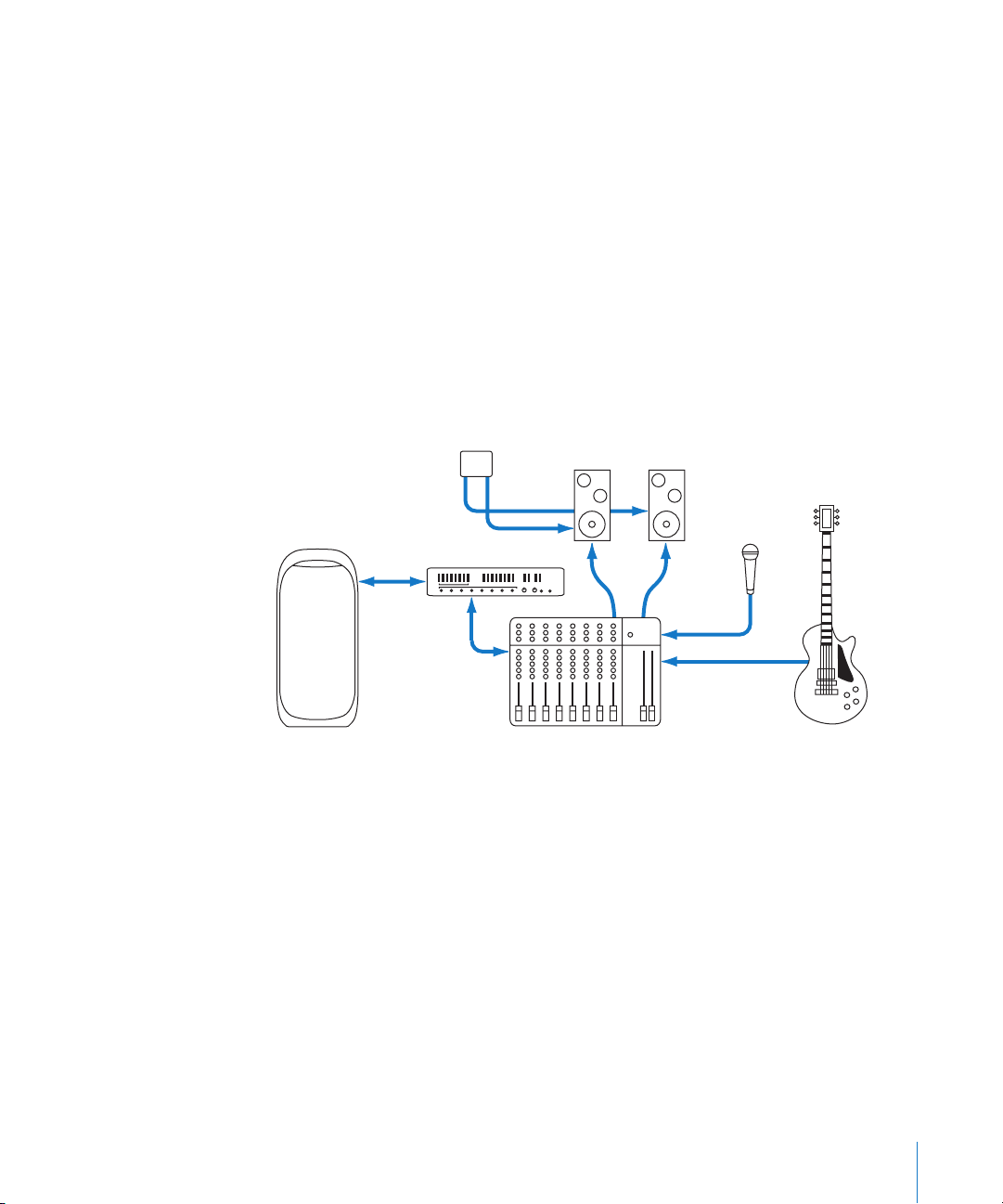

Setting Up a System Using a FireWire Audio Interface

With this setup, you can record audio input from several sources simultaneously, and

monitor audio output channels independently, through a mixer connected to a

FireWire audio interface.

This setup uses the following equipment:

Your computer and display

FireWire audio interface with FireWire cable to connect to your computer

Mixer (8 channels) with built-in pre-amplifier

Microphones

Musical instruments (guitars, bass, keyboards, and outboard effects units)

Set of powered monitors or speakers

Cables to connect microphones and instruments to the mixer and audio interface

Speaker cables

Monitors

Microphone

Audio interface

FireWire

cable

Computer

Speaker

cables

Mixer

Chapter 2 Setting Up Your System 29

Instrument

Utility window

3 The Soundtrack Interface

3

In Soundtrack, you work in three main windows:

the Project window, the Media and Effects Manager,

and the Utility window.

Project window

Media and Effects

Manager

The Project window includes the Timeline, where you arrange audio clips.

The Media and Effects Manager is where you locate and preview audio and video

files to add to your project, and also where you add and adjust realtime effects.

The Utility window has tabs where you can add and view a video in a project, see the

master level meters, get details on clips and other items, and set up recording.

31

Project Window

The Project window is the “canvas” where you work on your projects. The Timeline is

where you arrange and edit audio clips.

Tabs

Mono Mix button

Master volume slider

Playhead Position

value slider

Toolbar

Transport

controls

Selection Length

value slider

Toolbar: Includes tools for common functions. You can customize which tools appear

in the Toolbar.

Tabs: You can switch between any projects open in the Timeline.

Transport controls: Control playback and the position of the playhead, and turn

recording on or off. (For more information, see “Transport Controls” on page 33.)

Master volume slider: Adjusts the overall volume when you play the project. The

volume level defaults to 0 dB when you create a project. Adjusting the master

volume slider does not affect export volume.

Mono Mix button: Click to listen to a temporary mono mix of the project.

Playhead Position value slider: Displays the current playhead position. You can move

the playhead by clicking the arrows, dragging, or typing a value.

Selection Length value slider: Displays the length of the current Timeslice in the

Timeline. You can change the Timeslice or selection length by clicking the arrows,

dragging, or typing a value.

32 Chapter 3 The Soundtrack Interface

Toolbar

The Toolbar is located at the top of the Project window. When you first open

Soundtrack, the Toolbar includes buttons for creating a new project, managing layouts,

displaying the Utility window, adding markers, and other common functions. You can

customize the Toolbar, adding buttons for functions you want to access frequently. For

information about customizing the Toolbar, see “Customizing the Toolbar” on page 50.

Transport Controls

You use the transport controls to control playback, set the position of the playhead,

start recording, and activate the playback region.

Go to End

Cycle

MIDI Sync

Play from Beginning

Record

Go to Beginning

Play/Pause

Record button: Starts and stops the recording process.

Play from Beginning button: Starts playback from the beginning of the project.

Go to Beginning button: Moves the playhead to the beginning of the project, or to

the beginning of the playback region if it is active.

Play/Pause button: Starts playback at the current playhead position. If the project is

playing, stops playback.

Go to End button: Moves the playhead to the end of the project, or to the end of the

playback region if it is active.

Cycle button: Activates the playback region, if one is set in the Time ruler.

MIDI Sync button: Synchronizes playback with incoming MIDI Clock and MIDI

Timecode (MTC) signals.

For information on using the transport controls, see “Controlling Playback with the

Transport Controls” on page 56.

Chapter 3 The Soundtrack Interface 33

Timeline

The Timeline gives you a visual representation of a project, showing the position of

clips, the playhead, and other items in time. The Timeline is organized into three groups

of horizontal rows called tracks, busses, and outputs. You can add and arrange audio

clips in tracks, use busses to create submixes, and send audio to physical output

channels using outputs. You can control the sound of each track, bus, and output using

the controls in its header.

Timeline editing tools

Time display

Audio tracks

Automation Mode

pop-up menu

Timeline controls

Project

controls

Global Timeline view

Level meters

Time ruler

Track area

Scroll bar

Timeline editing tools: Select items using the Selection (arrow) tool, or split audio

clips using the Split (razor) tool.

Automation Mode pop-up menu: Choose the mode for recording automation using

the onscreen controls.

Project controls: Set the project’s time signature, tempo, key, sample rate, time

format, and other properties using these controls.

Show pop-up menu: Choose whether the video track, audio tracks, busses, outputs,

and master envelopes are visible in the Timeline.

Global Timeline view: Shows a miniature view of the entire Timeline and the playhead

position, and lets you move quickly to different parts of a project.

34 Chapter 3 The Soundtrack Interface

Time display: Shows the current playhead position in both Time-based and

Beats-based formats. You can set the playhead by typing a new playhead position

in the time display.

Level meters: As the project plays, the level meters show the volume level of the first

output (Output 1).

Time ruler: You can precisely position clips, the playhead, and other items to a specific

point in time (minutes, seconds, frames) or to a musical beat using the Time ruler.

Track area: Includes horizontal rows for tracks, busses, and outputs. Also includes the

playhead, envelopes, and markers.

Headers: Each track, bus, and output has a header with an icon, name, volume slider,

and other controls. (For more information, see “Headers” on page 35.)

Timeline controls: Includes controls to show the master envelopes, turn snap on or

off, set the track height, and zoom in or out. (For more information, see “Timeline

Controls” on page 36.)

Scroll bar: Moves the Timeline horizontally so you can see different parts of the project.

Headers

Each track, bus, and output in the Timeline has a header that includes the track name,

track icon, and a set of track controls.

Envelopes

disclosure triangle

Drag handle

Name field

Record Enable button

Volume sliderIcon

Effects button

Mute button

Solo button

Output

pop-up menu

Pan slider

Drag handle: Click to select the track, bus, or output and drag to reorder it in the Timeline.

Icon: You can choose an icon for the track, bus, or output, making it easy to quickly

distinguish them in a large project.

Name field: You can type a new name for the track, bus, or output in the name field.

Record Enable button: Enables (or disables) the track for recording when you click the

Record button. Only tracks have Record Enable buttons, not busses or outputs.

Mute button: Mutes (or unmutes) the track, bus, or output.

Solo button: Solos (or unsolos) the track, bus, or output. Soundtrack supports both

multiple solo and exclusive solo.

Effects button: Displays the Effects tab of the Media and Effects Manager with the

track, bus, or output effects settings.

Chapter 3 The Soundtrack Interface 35

Envelopes disclosure triangle: Shows the track, bus, or output envelopes in the area

directly below the track.

Volume slider: Sets the track, bus, or output relative volume in the overall mix.

Output pop-up menu: Choose an output for the track or bus, or choose the physical

output channels for the output from the menu.

Pan slider: Sets the pan position of the track or bus. Appears in track and bus

headers only, not in output headers.

For detailed information about using the track controls, see “Using the Track Controls”

on page 96.

Timeline Controls

The lower-left corner of the Timeline contains controls for various aspects of Timeline

display and operation.

Master Envelopes button

Snap button

Track Height control

Snap To Value

pop-up menu

Zoom control

Master Envelopes button: Shows or hides the master envelopes.

Snap button: Turns snap on or off.

Snap To Value pop-up menu: Sets the value to which items in the Timeline snap.

Track Height control: Sets the height of tracks, busses, and outputs to one of four

settings, from Reduced to Large.

Zoom control: Click the control or drag the slider to change the zoom level. You can

zoom in to edit clips precisely, or zoom out to display more of the Timeline.

For information about using master envelopes, see “Master Envelopes” on page 144. For

information about snap, see “Using Snap” on page 70. For information about using the

Track Height control and zoom control, see “Moving Around in the Timeline” on page 89.

36 Chapter 3 The Soundtrack Interface

Media and Effects Manager

The Media and Effects Manager is where you locate and preview media (audio and video)

to add to your project. It has five tabs: The Browser, Favorites, and Search tabs give you

three different ways to find media files; the Bin gives you quick access to media files for

the current project; and the Effects tab is where you add and adjust effects.

Browser Tab

The Browser tab displays the disks connected to your computer in a view similar to

the Finder’s list view. You can also preview files in the Browser tab, and drag them to

the Timeline.

Tabs

Back and Forward

buttons

File list

Preview controls

Computer and

Home buttons

Path pop-up menu

Media pop-up menu

Back and Forward buttons: Move through previously viewed levels of the folder hierarchy.

Computer button: Displays your computer’s hard disk and other storage media

connected to your computer.

Home button: Displays the contents of your home directory.

Path pop-up menu: Displays the levels of the file path to the current location, letting

you move back to a previous level.

File list: Displays the files and folders at the current location.

Preview controls: Include Play and Mute buttons and a volume slider. For information

about using the Preview controls, see “Using the Preview Controls” on page 67.

Media pop-up menu: Choose menu items to add a Favorite, add a file to the Bin, and

perform other functions.

Chapter 3 The Soundtrack Interface 37

Favorites Tab

You can store frequently used items in Favorites so that you can easily access them

directly. You can also preview files in Favorites, and drag them to the Timeline.

Favorites list

Preview controls

Media pop-up menu

Back and Forward buttons: Move through previously viewed levels of the folder hierarchy.

Path pop-up menu: Displays the levels of the file path to the current location, letting

you move back to a previous level.

Favorites list: Displays the files and folders at the current location.

Preview controls: Include Play and Mute buttons and a volume slider. For information

about using the Preview controls, see “Using the Preview Controls” on page 67.

Media pop-up menu: Choose menu items to remove a Favorite, add a file to the Bin,

and perform other functions.

38 Chapter 3 The Soundtrack Interface

Search Tab

The Search tab lets you locate audio and video files using a variety of criteria. You can

perform text searches and search for Apple Loops and other tagged file formats using

keywords for instrument, genre, mood descriptors, and other categories. Matching files

are displayed in the Search Results list. Once you locate the files you want to use, you

can preview them in the Search Results list or drag them to the Timeline.

Category pop-up menu

Button and Column

View buttons

Keywords list

Time Signature

pop-up menu

Search Text field

Search Results list

Preview controls

Setup button

Matches list

Scale Type pop-up menu

Nearby Keys button

File Type pop-up menu

Media pop-up menu

The Search tab has two views, Column view and Button view. Column view features a

Keywords list containing keywords, and a Matches list with subcategories you can use

to refine your searches. Button view displays a matrix of keyword buttons you can click

to see matching files.

Keyword buttons

Chapter 3 The Soundtrack Interface 39

Button and Column View buttons: Change the view to either Button or Column view.

Category pop-up menu: Restricts the available keywords to a particular category.

Setup button: Displays the Search Setup dialog, from which you add items to the

Search database.

Time Signature pop-up menu: Restricts search results to files with the selected

time signature.

File Type pop-up menu: Choose whether to display all files, or only looping or

non-looping files.

Scale Type pop-up menu: Restricts search results to audio files using the selected scale.

Keyword buttons (Button view only): Displays files matching the keyword in the

Results list.

Keywords list (Column view only): Displays files matching the keyword in the Results

list and displays subcategories in the Matches list.

Matches list (Column view only): Displays subcategories of the selected keywords.

Search Text field: Type text in the field to display matching files whose filename or

path contains the search text.

Nearby Keys button: Restricts search results to keys within two semitones above or

below the project key.

Search Results list: Displays the files matching the selected search criteria, in

alphabetical order. Includes columns displaying the tempo, key, and number of beats

of each file. You can click files to preview them.

Preview controls: Include Play and Mute buttons and a volume slider. For information

on using the Preview controls, see “Using the Preview Controls” on page 67.

Media pop-up menu: Choose menu items to add a Favorite, add a file to the Bin, and

perform other functions.

40 Chapter 3 The Soundtrack Interface

Bin Tab

The Bin tab lists the media files added to the project. You can drag files from the Bin

tab to the Timeline. You can also add files to the Bin for easy access in a project. Files

not currently added to the project appear dimmed, and offline files appear in red text.

File list

Preview controls

Category list

Show pop-up menu

Effect Parameters area

Media pop-up menu

File list: Displays the media files in the current project.

Preview controls: Include Play and Mute buttons and a volume slider. For information

about using the Preview controls, see “Using the Preview Controls” on page 67.

Media pop-up menu: Choose menu items to add a Favorite, add a file to the Bin, and

perform other functions.

Effects Tab

You add effects and sends to your project and adjust effect parameters in the Effects

tab. When you click the Effects button on a track, bus, or output, the Effects tab appears

showing the item’s current effects settings and sends.

Effect list

Add Effect button

Remove Effect button

Add Send button

Reset Effect button

Chapter 3 The Soundtrack Interface 41

Category list: Lists the categories of available effects, which are categorized by

manufacturer. Click a category to see the effects for that category in the Effect list.

Effect list: Lists the effects in the selected category. Double-click an effect to add it to

the track, bus, or output.

Show pop-up menu: Choose an item (a track, bus, or output) from the Show pop-up

menu to display its effects settings.

Add Effect (+) button: Adds the selected effect to the current effects chain.

Remove Effect (–) button: Removes the selected effect from the current effects chain.

Effect Parameters area: Displays the parameters for effects in the current effects

chain. Click an effect’s disclosure triangle to see its parameters. You can adjust effect

parameters using the controls in the Effect Parameters area.

Add Send button: Adds a send to the end of the current effects chain for the track.

You can add sends only to tracks, not to busses or outputs.

Reset Effect button: Resets the selected parameter or group of parameters to its

default value (or values).

Utility Window

The Utility window features tabs for viewing a video in a project, observing project

levels, viewing details, and setting up recording.

Video Playback

value slider

Video Tab

The Video tab is where you add a video to a project, view the video, and control

video playback.

Video Scale

pop-up menu

Video viewing area

Video transport controls

42 Chapter 3 The Soundtrack Interface

Video Playback value slider: Move the video to a specific frame by dragging, clicking

the left or right arrow, or double-clicking and typing a value in the value slider.

Video Scale pop-up menu: Choose the scale of the video in the Video tab from the

pop-up menu.

Video viewing area: Add a video by dragging it into the viewing area, and watch it

play in the viewing area.

Video transport controls: Control playback of the video with the project using the Play

from Beginning, Previous Frame, Play/Pause, Next Frame, and Cycle buttons.

Recording Tab

The Recording tab is where you edit a track’s recording settings. When you click a

track’s Record Enable button, the Recording tab appears, displaying the track’s current

recording settings.

Peak indicator

Level meters

Input pop-up menu

Gain slider and field

Stereo checkbox

Monitor pop-up menu

Mute Project checkbox

Disk space indicator

Peak indicator: Shows the highest level reached by the recording input signal. If the

level rises above 0 dB, the peak indicator becomes red to indicate clipping.

Level meters: Show the input volume for the selected track during recording.

Input pop-up menu: Choose the input device and input channel (or channels)

for recording.

Gain slider and field: Drag the slider or type a number in the field to set the input

gain for recording.

Stereo checkbox: Select to record to a stereo file, or deselect to record to a mono file.

Monitor pop-up menu: Choose the output device and output channel (or channels)

for monitoring during recording.

Mute Project checkbox: Select to mute the project during recording, so you hear only

the sound being recorded.

Disk space indicator: Shows the available disk space on the recording sessions

location set in Recording Preferences.

Chapter 3 The Soundtrack Interface 43

Meters Tab

The Meters tab displays stereo level meters that you can use to observe the volume of

the first output in a project.

Peak indicator

Level meters

Reset button

Go to Peak buttons

Peak Value and

Location display

Peak indicator: Shows the highest level reached as the project plays. If the level rises

above 0 dB, the peak indicator becomes red to indicate clipping.

Level meters: Show the output volume of the overall project as the project plays.

Peak Value and Location display: For each channel, displays the highest (peak) value

played, and its location.

Go to Peak buttons: Move the playhead to the channel’s peak.

Reset button: Resets the Peak Value and Location display and the peak indicator to

their default values.

44 Chapter 3 The Soundtrack Interface

Details Tab

The Details tab shows information about the currently selected media file, clip, marker,

or envelope point, and gives you a way to edit clip, marker, and envelope point details.

File Details

Clip Details

Audio File Details

When you select an audio file, the Details tab displays information about the file,

including the file icon, hints, tags for Apple Loops and other tagged audio files, sample

rate, bit depth, file size, and whether the file is a looping or non-looping file.

Video File Details

When you select a video file, the Details tab displays information about the file,

including the dimensions of the video, file size, length in seconds, frame rate, and other

information. You can preview the video file in the Details window by clicking the Play

button in the Media and Effects Manager preview controls.

Chapter 3 The Soundtrack Interface 45

Clip Details

Clip display: Displays the waveform of the selected clip.

Playback buttons: Set the clip playback mode to looping or non-looping.

Measure in pop-up menu: Sets the units shown in the Position, Duration, and Offset

value sliders.

Position value slider: Set the position (start point) of the selected clip.

Duration value slider: Set the duration (length) of the selected clip.

Offset value slider: Set the offset of the selected clip.

Transpose pop-up menu: Choose the number of semitones to transpose a looping

clip from the pop-up menu.

Clip Speed pop-up menu: Choose the clip playback speed for a looping clip from the

pop-up menu.

Marker Details

Type buttons: Select whether the marker is a Beat marker or a Time marker.

Name field: Type a name for the marker.

Position value slider: Set the time position of the selected marker.

Measure in pop-up menu: Choose the units for setting the marker position.

Envelope Point Details

Position value slider: Set the time position of the selected envelope point.

Value value slider: Set the value of the selected envelope point.

Measure in pop-up menu: Set the units shown in the Position value slider.

Copy from Previous Point button: Set the value of the selected envelope point to the

value of the preceding one in the envelope.

Copy from Next Point button: Set the value of the selected envelope point to the

value of the next one in the envelope.

46 Chapter 3 The Soundtrack Interface

4 Getting Started with Soundtrack

4

This chapter describes what projects you can create in

Soundtrack, and how to work with windows, use layouts,

play projects, and set Soundtrack preferences.

Overview

In Soundtrack, you create and work with multitrack projects. Multitrack projects let you

arrange audio clips in tracks in the Timeline and synchronize them to a video clip. You

add clips to the Timeline from the Media and Effects Manager or from the Finder, and

can also record audio directly into tracks. Each track has controls you can use to adjust

volume and pan, mute or solo the track, add effects, and adjust effect parameters. The

Timeline also includes busses and outputs with similar controls. You can mix a project

in the Timeline, and automate volume, pan, and other controls using envelopes in the

Timeline.

You can export a project mix to an audio file, which you can import into

Final Cut Express or another application. You can also export selected tracks, busses,

and outputs or export a project to a QuickTime movie.

For information about creating, saving, and working with projects, see Chapter 5,

“Working with Projects,” on page 77.

Note: The audio files used in a project are not stored as part of the project file. The

project file only saves references (pointers) to their location on disk. This keeps the size

of the project file relatively small, and lets you use an audio file in multiple projects.

47

Setting Up Your Workspace

There are several ways you can set up the Soundtrack workspace to suit your display

size and workflow. You can arrange windows, reorder and detach tabs in the Utility

window and the Media and Effects Manager, and add and reorder buttons in the

Toolbar. You can create layouts for different tasks and switch between them.

Basic Window Controls

You can move, resize, or minimize a project’s windows. Most windows feature tabs,

which give you flexibility in arranging the visual elements of a project.

To move a window:

m Drag the window by its title bar to a new location.

To resize a window, do one of the following:

m Drag the Size control in the lower-right corner of the window until the window is the

desired size.

m Hold the pointer near the edge of a window until it becomes a Resize Window pointer,

then drag the window edge left or right to resize adjacent windows together.

To minimize a window to the Dock:

m Click the minimize button in the window’s title bar.

To close a window:

m Click the window’s close button (or press Command-W with the window active).

Using Tabs

Soundtrack uses tabbed windows so you can quickly access different project views and

controls. You can switch between projects and between different controls in the Media

and Effects Manager and the Utility window. Clicking the tab you want makes it active

and brings it to the front. You can reorder the tabs in a window to easily access the tabs

you use frequently.

To reorder tabs:

m Drag a tab left or right in the window’s tab area.

You can also detach a tab from its docked position in the Utility window or the Media

and Effects Manager, which creates a separate draggable, resizeable window for the

tab. For example, you can drag the Bin tab to a new location so that you can easily

move items from the Browser tab to the Bin tab.

48 Chapter 4 Getting Started with Soundtrack

To detach a tab from the Utility window or the Media and Effects Manager:

m Drag the tab out of its docked position in the window to create a separate window for

the tab.

To reattach a tab:

m Drag the tab back to its original location at the top of its originating window.

Using Project Layouts

Soundtrack lets you save and recall preset window arrangements called layouts, so that

you can optimize your workspace for different tasks and different display sizes. You can

show, hide, and resize windows, then save each window arrangement as a layout.

To save a project layout:

1 Arrange the application windows as you want them to appear.

2 Choose Window > Save Layout.

3 In the Save dialog, type a name for the layout, then click Save.

The layout is saved, and appears in the Layouts submenu.

To switch to a saved project layout:

m Choose Window > Layouts, then choose the layout you want to use from the submenu.

To delete a saved layout:

1 Choose Window > Manage Layouts.

2 In the Manage Layouts dialog, select the layout you want to delete.

3 Click the – (minus) button to delete the layout, then click Done.

Chapter 4 Getting Started with Soundtrack 49

Customizing the Toolbar

The Toolbar at the top of the Project window contains buttons for frequently used

commands. You can customize the Toolbar, adding buttons for the actions you use

most often, and can return to the default set later.

The default set of Toolbar buttons includes buttons for creating new projects, opening

project windows and tabs, adding markers, and other common commands. You can

customize the Toolbar with additional buttons for other commands. You can also hide

the Toolbar to maximize available screen space. You customize the Toolbar by dragging