Page 1

F A I T H • P O W E R • W E A L T H

GLOBAL CONQUEST AND DIPLOMACY

FROM COLUMBUS TO NAPOLEON

1 4 9 2 - 1 7 9 2

Page 2

Europa Universalis

Table of Contents:

Installation 2

Introduction

A Simulated Europe 3

What is Europa Universalis? 3

Why is the Clock Ticking? 3

What is the Goal of the Game? 4

The Game - An Overview 5

How do I Play? 5

How is the Map Designed? 6

Geography and Weather 7

Learning Scenario

General 8

The Top Line above the Map Window 8

The Top Line above the Info. Window 8

The Information Window - a Province 8

Army Units and Battles 9

Choosing Army Units 9

Movement of Troops 9

Discovered and Undiscovered Terrain 9

Occupied and Non-Occupied Terrain 9

Colonization and Economy 10

To Colonize a Province 10

From HMS Mayflower to Cities 10

The Financial Summary 11

The Budget Window 11

Trade and Merchants 12

Placing Merchants 12

The Economical Effects of Trade 12

Fleets and Sea Transport 12

Loading of Army Units 13

Unloading of Army Units from a Fleet 13

Trading Posts 13

How to Establish a Trading Post 14

Neighboring Countries 14

Diplomacy 15

War 15

To Prepare for War 15

To Declare a War 16

To Win a War 16

Offers of Peace 16

Activities

Countries 17

Provinces 17

Sea Zones 19

Cities and Capitals 20

Trading Posts and Colonies 20

Terra Incognita and

Permanent Terra Incognita 21

Stability and the Wrath of Your Subjects 22

What is Stability? 22

Things that Lower Stability 22

Things that Increase Stability 23

What is Affected by Stability? 24

Rebellions and the Risk of Rebellion 25

Liberation Movements 27

Religion and Tolerance 28

State Religion and Provincial Religion 29

Religious Tolerance 31

Four Important Events 31

The Foreign Policy Consequences

of Religion 32

The Effects of Religion on

Domestic Politics 33

Converting by Peaceful or

Violent Means 33

Page 3

Politics and Diplomacy 34

Diplomacy as a Political Weapon 35

Diplomats and Relations 35

Royal Marriages 37

Alliances 38

Vassalage 39

Annexation 40

Refusal to Trade 40

War Affects Your Relations 41

Tolerance Affecting Your Relations 41

The Holy Roman Empire 42

War and Peace 42

Casus Belli and Declarations of War 42

Advantages and Disadvantages of War 43

Side Effects of War 44

Manpower and the Limitations

of Your Provinces 44

Pillaged Provinces 45

War Taxes 45

The Goal of War 45

Peace Treaties and War Damages 46

Movement and Battle 47

Army Units 48

Fleets 49

Commanders and Specialists 50

Movement Restrictions 50

Naval Supremacy and Interception 51

Naval Battles 52

Naval Blockades and Ports 53

Pitched Battles 54

Retreat 55

Fortifications, Sieges, and Assaults 55

Supply Lines 56

Attrition 57

Combat Morale 58

Economy and Infrastructure 59

Your Economy is Your Heart 59

Europa Universalis

Annual Income 59

Monthly Income 60

Other Income 60

Provinces and Population Growth 60

Level of Development Inhabitants 62

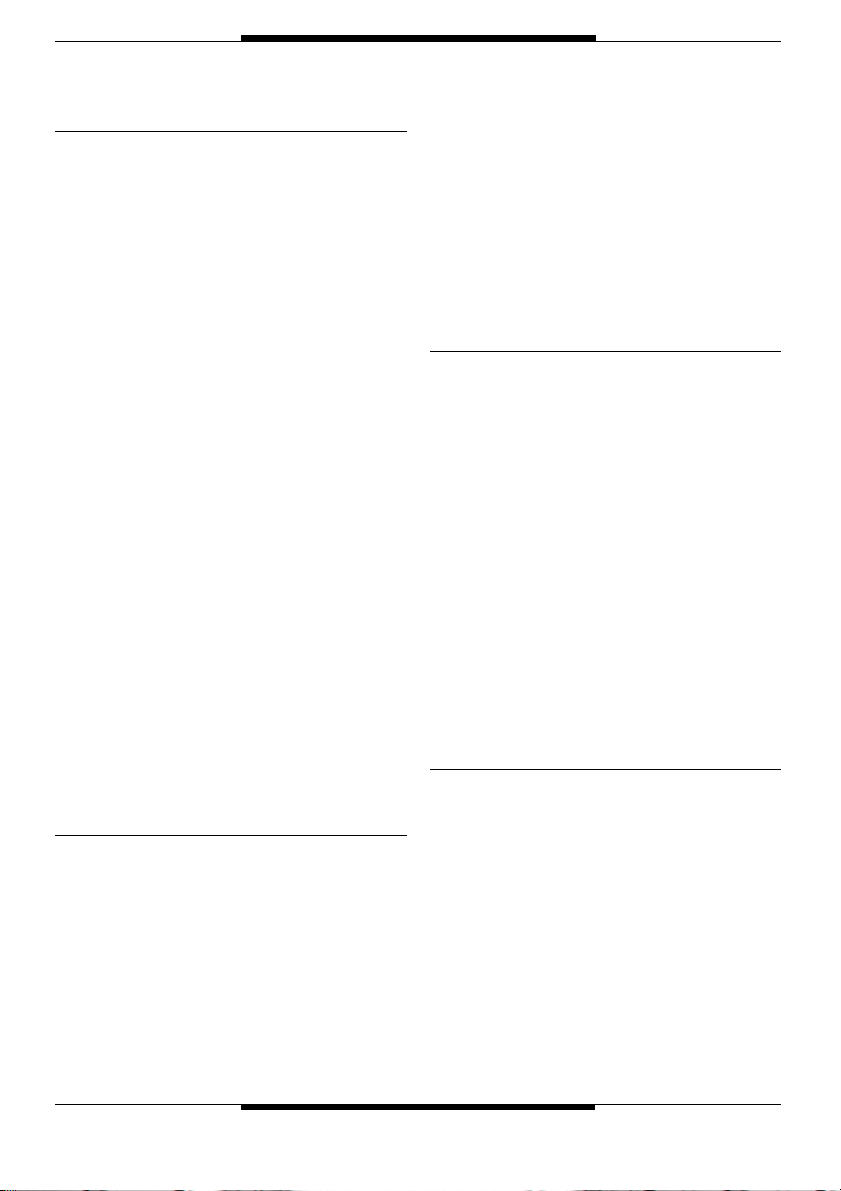

Production and Goods 63

External Factors 66

Loans 66

Inflation 68

Upgrading the Infrastructure 69

Managing Your Resources 69

Trade and Colonization 70

Supply, Demand and Market Prices 71

Centers of Trade, Merchants and

Trade Income 71

The Closing of Japan 74

Pirates 74

Trading Posts and Merchants 75

Colonization of the New World 76

The Treaty of Tordesillas 77

Explorers and Conquistadors 77

Colonial Growth and

Economic Consequences 78

Protecting Your Colonies 79

Technology and Development 79

To Develop Over Time 79

To Invest in Stability 80

Areas of Technology and Research 80

Cultural Technology Groups 81

Investing in Factories 81

Monarchs 83 - 94

The Archive 95 - 96

Historic Review 97 - 126

Technical Support 127

Credits 128

1

Page 4

Europa Universalis

Installing and uninstalling the game.

The installation program of Europa Universalis

starts automatically when the CD is inserted in

your CD player. If your CD-ROM unit does

not have the auto run function activated, you

may start the installation by double clicking

setup.exe, which you will find in the root directory of the CD.

As soon as the installation program has started, you may install Europa Universalis and, if

n e c e s s a ry, DirectX 7.0, which is included on

the CD. When the actual installation has begun, just follow the instructions on the screen.

If Europa Universalis is already installed on

your computer just press Play in the installation

program to start. You may also start the program from a suitable button in the Pro g r a m

menu under the Start menu. You may uninstall

Europa Universalis at any time by using either

the Installation program or using the Add and

Remove program of the Control Panel.

System requirements:

Pentium 200Mhz (PII 300Mhz recommended)

Windows 95/98/NT/2000 (Service pack 4).

2Mb of Video RAM ( S u p p o rting 800x600),

64Mb RAM (128 Mb RAM re c o m m e n d e d )

180Mb free hard drive space, 2x CD-ROM

drive, Mouse or equivalent input device DirectX

7.0 or higher (Included with the game).

Requirements for network games:

Bandwidth of at least 512 kb/s

TCP/IP protocol installed

Commands for the user interface

• "Shift" + "F12" opens the chat function of

the network game.

• "F11" saves a screenshot as a bitmap picture

on your hard disk.

• "P a u s e / B reak" pauses the game/Restart s

the game in progress.

• "Ctrl" + "+" increases game speed (not avail-

able in network games).

• "Ctrl" + "–" decreases game speed (not

available in network games).

• "+" increases map size.

• "–" decreases map size.

• "ESC" and "ENTER" often functions as

Yes/No in dialogue windows.

• "F12" opens the console. Press "F12" again

to close.

• "Home" centers the map on your capital.

• "F1" lets you view missions or victory points.

• E/P/N are quick commands for easy

switching of map views.

• "F10" opens the start menu for saving and

loading games, including settings.

Commands for Armies and Navies

• "PageUp/PageDown" for fast jumps between your various units.

• "Ctrl" + "[number]" associates the chosen

unit with that number.

• "[Number]" chooses the numbered unit,

p ress the number again, and the map will

center on the chosen unit.

• "s" divides the chosen unit into two equal

parts.

• "a" quick command during siege.

• "u" to unload armies from a chosen fleet, if

you have troops onboard.

• "g" forms selected units into a single unit.

How to join a pier-to-pier game

• Start Europa Universalis as normal

• Click the [multiplayer] button

• Enter your desired name and press [internet]

• Enter IP address of the host and press [join]

How to host a pier-to-pier game

• Inform players of game and your IP address

• Start Europa Universalis as normal

• Click the [multiplayer] button

• Press the [host] button to host your

own game

• Select the scenario you wish to play

• Specify Victory options by accessing the

Victory menu

• Specify Game options by accessing the

Option menu

• When all options are set press [Start]

2

Page 5

Europa Universalis

A) Introduction

A Simulated Europe

This game tries to simulate the interaction between the European countries during the period between 1492 and 1792 as realistically as

possible. This means that Europe is divided into provinces, which in turn make up the various countries. The provinces have populations

that produce goods, pay taxes, engage in trade,

and are recruited as soldiers and sailors. Each

population has a religion that incorporates

their view of the world and moral position. If

the monarch and the government act counter

to morally acceptable behavior, there is a risk of

rebellion. The monarch and the govern m e n t

(actually the player) are responsible for the

country and represent the country to the rest

of the world. In this way all of the European

nations are part of the same quarreling family,

where some co-operate and others fight.

As time goes by the European nations

change, both in political, economic, and milit a r y strength. Depending on how well your

country is able to manage its resources, defend

its provinces, and invest in technology, nations

will rise or fall in power and status. Historically

the Ottoman Empire peaked during the 16th

c e n t u ry, after which its power slowly waned,

until it was finally regarded as the "Sick Man of

Europe" in 1792. Sweden began the period as

a backwards place on the outer fringes, and

then gained status as a great power during the

17th century, only to lose that status at the beginning of the 18th, to slowly sink into a second-rate power during the latter half of the

18th century.

What is Europa Universalis?

E u ropa Universalis is a game where you can

choose a European nation and play its ups and

downs over 300 years. The game provides what

you could philosophically call a "God perspective;" that is, you lead the country through 300

years, having the opportunity to be at many

places at the same time in order to make decisions.

This is an extensive and advanced game, but

do take it easy. By playing the learning scenario

and reading all the tips included in the game,

and reading the "The Learning Scenario"

chapter in this manual, you will soon be able to

play the game. In order to master the more

subtle parts of the game, you need to play a lot

of games and read the rest of the manual.

The game does not pretend to be historically

accurate. This means that it does not follow the

historical textbooks, because if it had, you

would not be able to act differently from the

actual governments. Instead you should view

the game as an "alternate history," that is, the

historic individuals, the nations, and the resources are provided, but you have a chance to

act differently. In your game the Thirty Years

War perhaps will never break out, or maybe

France will conquer America, or PolandLithuania will never cease to exist as a nation.

You lead a country and have a great number

of choices re g a rding war and peace, politics,

economics, and religion, but at the same time

your resources are limited because of the size

and traditions of your nation. You are simply

"The Grey Eminence" behind all of the

monarchs of your country during the period of

the game.

The game contains a number of diff e re n t

scenarios, including the Grand Campaign. The

various scenarios usually cover shorter time periods, while the Grand Campaign will let you

take your countr y from 1492 until 1792.

When choosing a scenario or the Grand Campaign, you always have the choice of when the

game should end.

Why is the Clock Ticking?

In a game like this, which is about historical

change, it is not possible to be in every place at

the same time. Time in the game is ru n n i n g

forward like a clock in reality, providing a real

sense of the flow of time, because an English

king, for example, did not know how the bat-

3

Page 6

Europa Universalis

tles against the French in North America

turned out until months later. Even war in general was an activity with uncertain results; since

you are the one who is moving and controlling

all of your troops, you are forced to give priority to some while the clock is ticking away. It also simulates the difficulties of running a large

e m p i re in contrast to a small, land-locked

c o u n t ry. As a player of Spain, for example, it

could be difficult to wage a successful war in

Northern Italy, at the same time that you are

colonizing a new province in Mexico, and

making improvements to the infrastructure in

the Philippines.

What you should know and remember is that

you may pause the game at any time. The clock

stops and the game stands still. In this "pause

mode" you can order troops around (although

they will not start moving until the game resumes), build army units and fleets, deal with

diplomatic offers, make changes in your budget, etc. You may also change the speed of the

"clock" at any time, i.e. change the speed of

the game, as you perceive it. In the beginning it

is advisable that you keep game time at a relatively slow speed, when you are feeling your

way around the various parts of the game.

What Is the Goal of the Game?

The goal of the game may actually vary from

player to player. The basics for the game are to

receive as many victory points as possible. It is

meaningless, at this moment, to discuss in any

g reater detail exactly what provides victory

points throughout the game, as we have not

yet discussed that area of the game. Instead we

will direct you to the list of victory points at the

end of the manual. If you play using the "stand a rd" victory conditions, the player with the

highest total points becomes the winner, but

please note that at the end of the game you will

see how many victory points your country has

received, and its relative position. This means

that you can play a country you find difficult to

play just to try to get a better result from game

to game, which is also a way of "winning." Another approach is to play Denmark, for example, and try to get more victory points than its

perennial enemy Sweden.

You can also choose a couple of other victory

conditions other than the "standard" ones.

The first choice is "Power Struggle," which

means that the country that is first to reach a

predetermined number of victory points is the

winner. Power Struggle is a good choice if you

4

Page 7

Europa Universalis

want to play a quick game. The second choice

is "Conquest," which means that the country

conquering a pre d e t e rmined number of

p rovinces is the winner. You set the number

when you determine victory conditions. Conquest is the number one choice if you wish to

decide the outcome of the game on the battlefields. The third choice is "Mission," which

means that each country will receive a specific

difficult mission, and the player that succeeds

first is the winner. Various missions may include: Russia must conquer all ort h o d o x

provinces in the Balkans, or Spain must "conquer England." Mission is the choice for players who would like to try something random,

yet challenging.

E u ropa Universalis is about a number of

ways of changing history, and changing history

becomes a goal in itself in the game, besides

winning. How you do it is up to you.

The Game – An Overview

When you start playing you will have a map in

front of you. This is the "game board" of the

game; in the same way you have a game board

in front of you when you play Monopoly or

chess. You lead a country, or more exactly, you

are a country, and all of the provinces within

the borders of your country belong to you.

Provinces outside your country belong to other countries. You also have access to army units

(symbolized by little soldiers) and fleets (symbolized by small warships), which you can

move around on the map (just like in chess and

Monopoly). By clicking a province you get access to information about it in the "information window" on the left side of the scre e n .

Here you are able to construct army units and

fleets, invest in infrastructure, and many other

things. Exactly what you are able to do and

how to do it will be discussed in greater detail

later on.

How Do I Play?

Naturally, leading a country during 300 years is

not an easy task. To win the game you need to

collect as many victory points as possible. Starting the game by waging as many wars as possible may get your country a large number of victory points, but may also lead to quick ruin. It

is usually better to collect victory points at a

relatively normal pace during all of your 300

years, rather than gaining points quickly during

just 100.

The primary problem facing your country is

pure survival. The Prussian diplomat who was

5

Page 8

Europa Universalis

involved in the third partitioning of Poland supposedly

said: "A nation not able to defend itself has no right to exist." In game terms your neighbors will try to take advantage of your weaknesses, but will also shy away from your

strength. In order to survive you must upgrade your defenses, and have enough army units and well-arm e d

fleets, but you must also pay attention to the development of your nation.

The secondary problem facing your country is development over time. If your country lags behind in economic or military development this will show up in losses

on the battlefields. When you consider economic development over time, it helps to think about this simple

metaphor. In very simple terms it is like putting money in

the bank. If you deposit 100 dollars at 10% interest, you

will have 110 dollars one year later, and 121 dollars two

years later. You should be aware of the dynamic nature of

economic development.

The third problem facing your country is discovering

the unknown world beyond the boundaries of Europe.

The discovery of new areas, and establishment of trading

posts or colonies, is quite costly at the beginning, but will

provide a lot of revenue later. The heart of the matter is

balancing your country’s priorities and making your resources meet your needs. A colonial empire also needs to

be defended, which means you should give the whole

idea some thought before you start putting things in motion. You may have to consider matters for the next ten or

twenty years ahead if you do not want to lose all you

gained due to poor planning.

How Is the Map Designed?

The game is played on a world map. You can’t see everything on the map at the same time, but only the provinces

and sea zones familiar to you country. In order to find out

more you need to explore the unknown parts of the map,

which are called Terra Incognita. This map, which we will

call the normal map, shows each province with its name,

its type of terrain, whether it contains cities, colonies, or

trading posts. It will also show land boundaries between

countries. In the sea zones you will see what the weather

is like, and whether it is winter or summer in the

provinces. Note that a fog stopping you from discovering

any army units in the provinces, or fleets in the sea zones

covers parts of the map. Areas not covered by the fog include your own country, the countries of your allies,

countries in which your monarch has entered royal mar-

6

Page 9

Europa Universalis

riages, and finally countries with which you are

currently at war. In these countries nothing is

hidden.

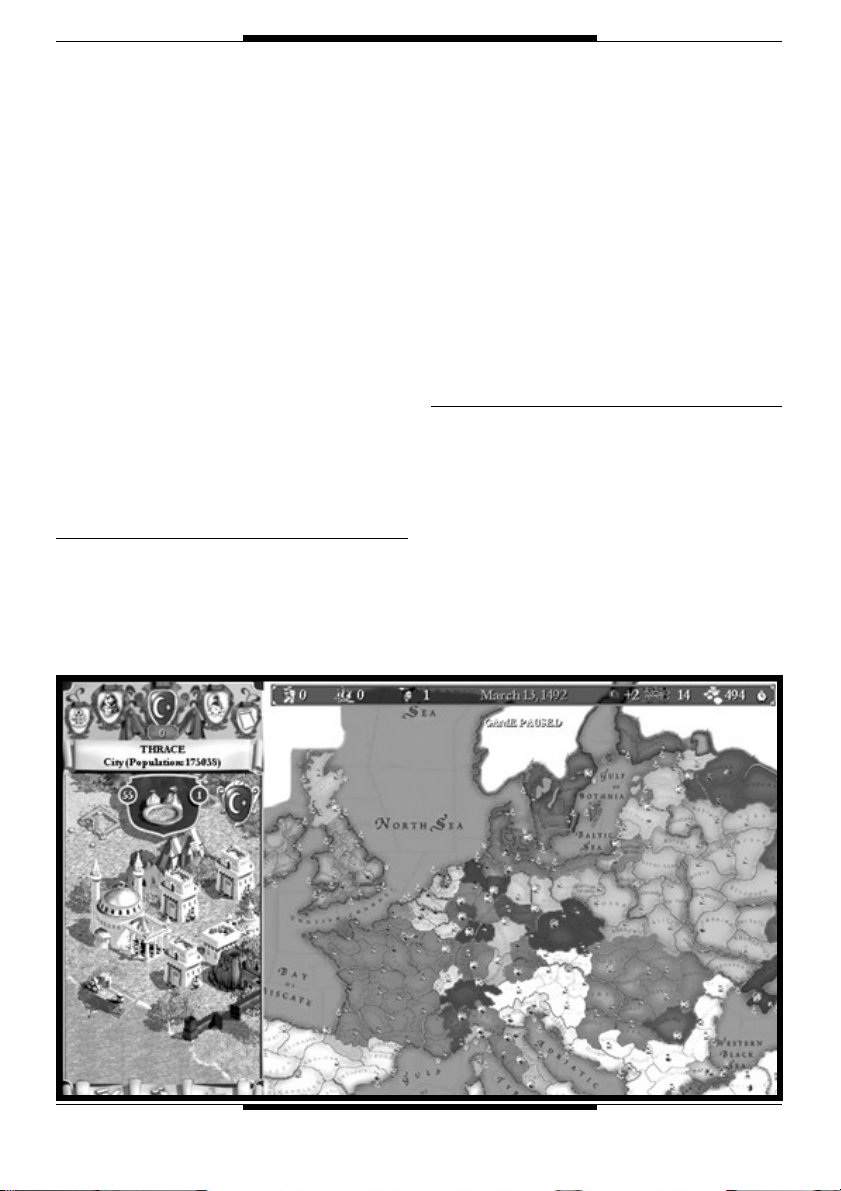

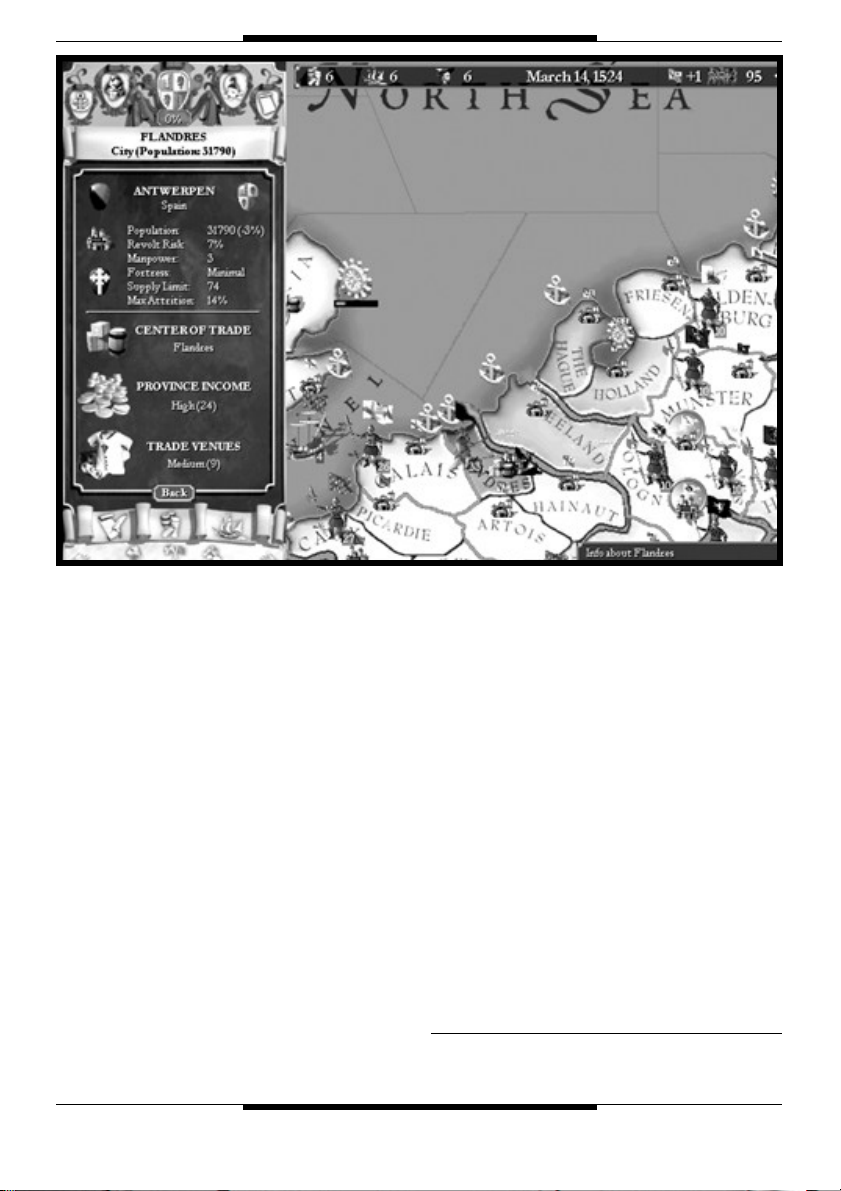

[screenshot of the "normal" map also showing

the fog of war]

You may also click on the button labeled the

"Political map" in order to view it. Here you

will find all of your foreign relations, and by

clicking a province in another country you are

shown the foreign relations of that country.

Note that this is the map you will be using

when you wish to perform diplomatic actions.

You may also click on the button labeled "Economic map," which shows the goods produced

in each province. There is also a "Trade map,"

showing the trade centers of the world, and

which provinces they control. The last map is

the "Colonial map," which you use when es-

tablishing trading posts or colonies. Note that

each map has a separate click able button,

which lets you view each one separately.

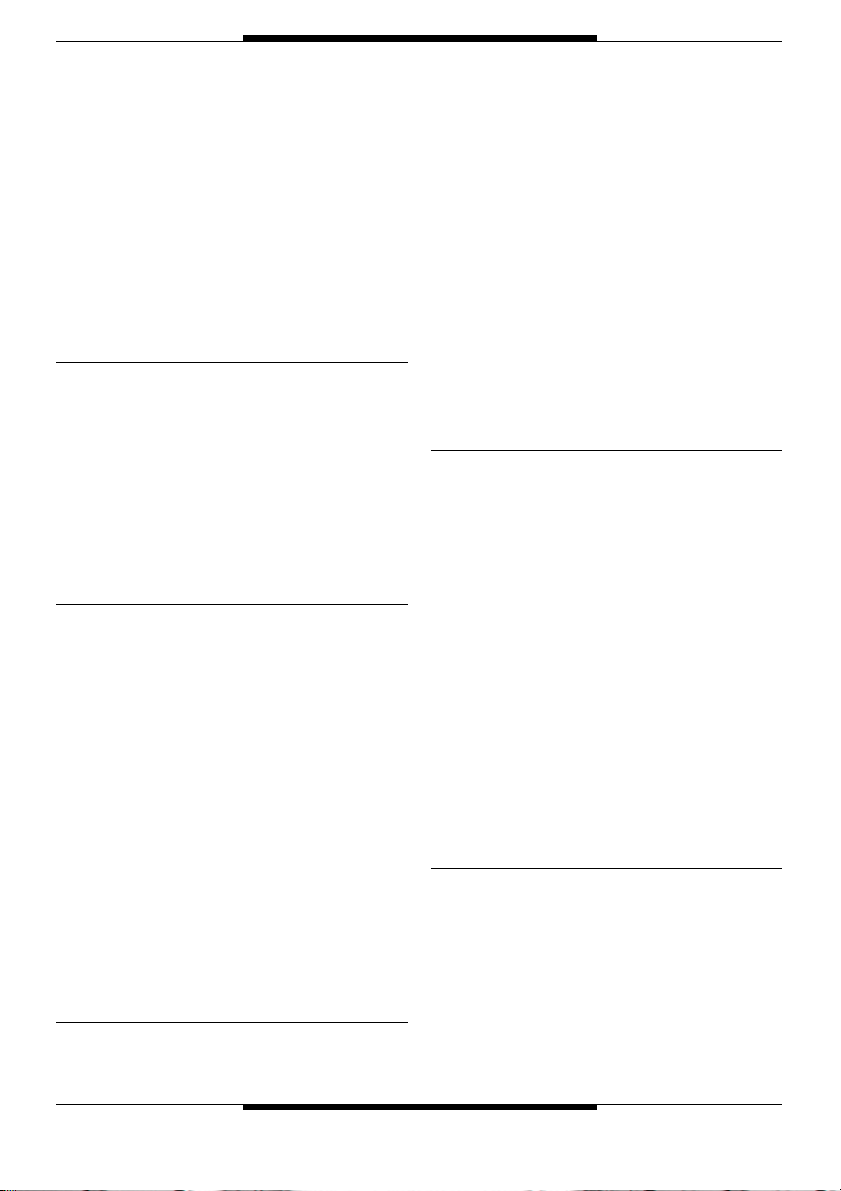

Geography and Weather

The game contains five different types of terrain: open terrain, forest, mountains, desert ,

and swamp. There is also one geographical obstacle: rivers. The terrain types affect the movement of army units, battles, and army unit attrition. Some provinces also suffer the effects of

winter, which in turn affect the various terrain

types.

Sea zones are also affected by the weather.

Certain sea zones may be ridden by storms, or

be covered by ice during parts of the year. Note

also that attrition is lower in sea zones next to

coastal provinces, compared with the open sea.

7

Page 10

Europa Universalis

B) Learning Scenario

General

The screen you see is divided into two fields, or

"windows." The larger window to the right is

the world map, of which you only see a very insignificant part. You will see more and more of

it as you discover the unknown areas. The

white and unknown parts of the map are called

"Terra Incognita," which is simply "The Unknown World" in Latin—the language of

knowledge and science during this age.

You will also see one pro v i n c e — U l s t e r,

which happens to be your only province, containing your capital. If you left click on Ulster

on the map, you will open a picture of your

capital in the other window. For the sake of

simplicity we call that window the Information

window.

The Info window will be described in full a

little later. Below the Info window you will find

the picture of a historical map, or more correctl y, an empty map. This is a world map in a

smaller format, which will aid you later in the

game when your knowledge of the world has

i n c reased. Note the appearance of "tips"

whenever a scenario is started. These tips provide quick and abbreviated information about

the most important functions of the game. We

recommend that you read these. You may also

access the "tips" by clicking the menu button

at the bottom of the Information window, and

then choosing "Tips."

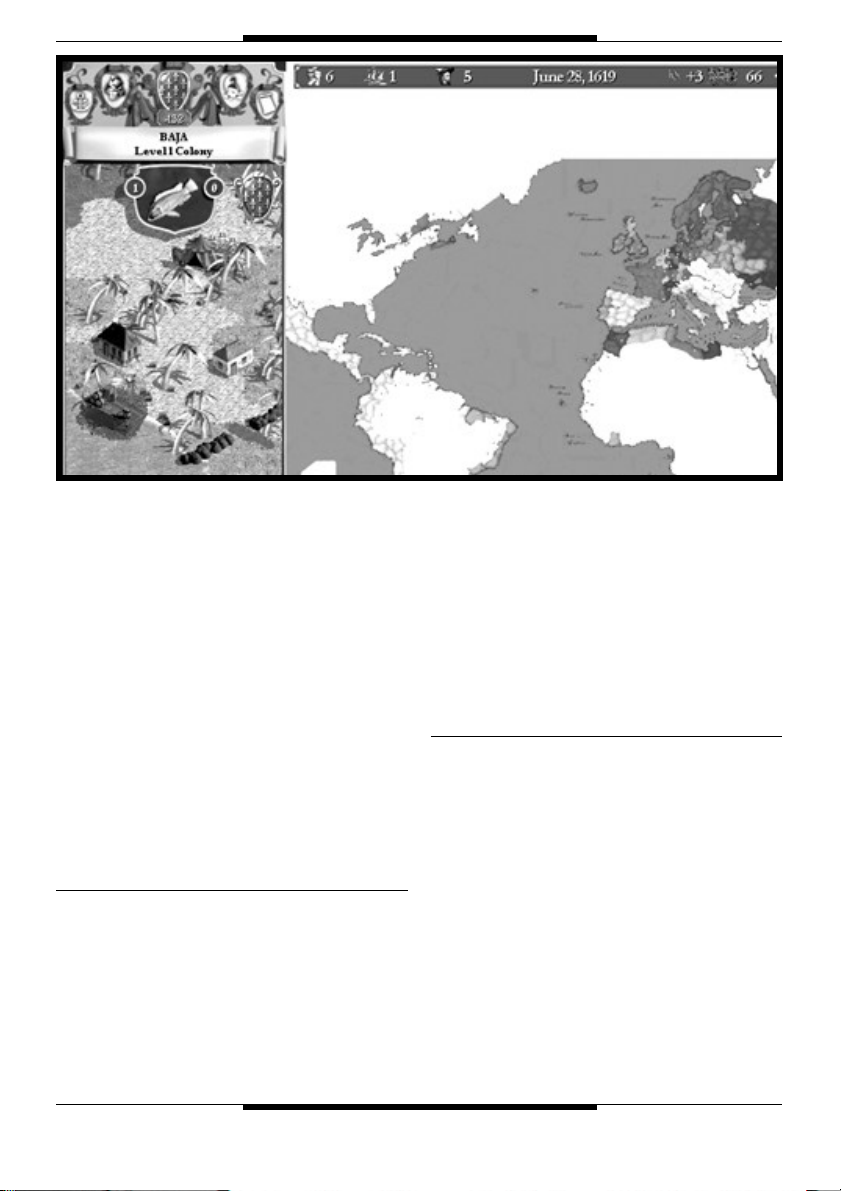

The Top Line above the Map Window

On the top line above the Map window, you

will find a border with three symbols and a

date—the game clock—followed by another

t h ree symbols. The first three show how many

M e rchants, Colonists, and Diplomats you have

available. If you place the pointer above any of

the symbols you get information about how often you receive new ones, and what generates

them. The clock is shadowed whenever you

pause the game, and white when time is ru nning. If you think that the "pro g ress of time" is

too fast or too slow, you may change it by click-

8

ing the menu button at the lower left of the Inf o rmation window, choosing Alternative, and

then following the instructions. The three symbols to the right of the clock show the Stability

level of your country, the Manpower in thousands of soldiers, and the contents of your tre as u ry expressed in Ducats, which was one of the

most common currencies during the historical

epoch. You will receive more background information if you point at the symbols.

The Top Line above the Information

Window

The embellished line above the Inform a t i o n

window contains five coats of arms. If you left

click any of these, specialized information will

be shown in the Information window. The

shields will provide the following inform a t i o n

( f rom left to right): naval information, land

a rmy information, general information about

the country and its monarch, the state budget,

and the Financial Summary. The military information shows your level of technology, your

upkeep costs, and your chances of changing the

wages and costs of your soldiers and sailors. The

economic information will show the income

and expenditures of your country, including

how they are allocated. You may also choose

how to allocate your re s e a rch investments in order to develop your technology levels.

The Information Window—a Province

When you left click on your only province, you

will see the city of the province of Ulster in the

Information window. By clicking on buildings

and objects in the Information window, you

get additional information about the objects.

The buildings are the places where the various

o fficials of your province work. The off i c i a l s

may be appointed to more qualified tasks by

clicking the buildings, which will give you

m o re advantages in the game. You may also

build fleets and recruit army units.

The church is a very important building. It

will be upgraded automatically when the population of the province increases. If you left click

the church you will find general inform a t i o n

Page 11

Europa Universalis

about the state of your province. If you click on

the text lines that appear when you click on the

c h u rch, you will get additional inform a t i o n .

You may also click on the symbols to get additional information about the economy and religion. In addition to the buildings of the

p rovince you also see another shield. The

shield shows the most important products of

the province, including provincial re v e n u e

from trade and taxes. When you appoint officials, for example, you will find that these revenues increase.

Army Units and Battles

Your first task is to recruit an army and fight a

battle. Note that there is a "Read more"-button in each "Mission window." We re c o mmend strongly that you read this additional information, as it provides both historical information and information about how the game

works. Please note also that by clicking anything under construction, you will find out

when the construction is due to be finished.

Choosing Army Units

Besides left clicking a unit, you may also keep

the left mouse button pressed and "circ l i n g "

the unit. You know that a unit is selected when

a green circle surrounds it, and you see an elongated rectangle at the base of the unit. The

morale of the unit is indicated by the colors

red, yellow, or green. A newly recruited unit always starts at the lowest possible morale. It will

then increase month by month to the maximum level allowed by your technology level.

The Information window provides additional

information about the chosen unit, such as unit

commander, strength, and attrition. You may

also split the unit into two parts, merge units

by first choosing all units in a province, and also reorganize – or customize – your units. Finally, you may opt to disband the unit.

Movement of Troops

When you have clicked the area you want to

move your army unit into, the troops will start

marching. You also see a green arrow showing

the direction of the march. If you wish to do

something else for a moment, such as take care

of your province, you will see the green arrow if

you choose the unit again. As you may have noticed, it will take a relatively long time to move

your troops to the new area. The movement of

troops takes a varying amount of time depending on the composition of the unit and the

state of the province to which you are moving

the unit. The province you moved your unit to

was undiscovered, giving you the maximum

t r a n s p o rtation time. In game time it takes at

least three months to move an army unit into

an undiscovered area. Note that you can reset

the speed of the game if you think the pace is

too slow at the beginning.

Discovered and Undiscovered Terrain

Discovered terrain is any terrain which is fully

disclosed on the map, while undiscovered terrain is only partly visible. The undiscovered terrain is partly covered by white, just like in old

maps, where any unknown terrain was represented in this fashion. Ulster was the only discovered terrain when you started the scenario.

Now you have discovered some more. Yo u

must discover any terrain that is only partly visible before you may conquer it. Normally you

need a Conquistador, or land military technology level of 11 in order to discover provinces.

Undiscovered sea zones usually require an Explorer or Naval technology level of 21. We have

made an exception from this rule in the learning scenario to let you discover provinces at an

earlier stage.

Occupied and Non-Occupied Terrain

"A nation always has an army, either its own or

somebody else’s," is a classical saying. This is

also correct in principle for this game. If you

see a province on the map containing a soldier,

it is an army unit occupying the province. If the

p rovince looks empty you may left click the

p rovince. If it belongs to somebody else you

will see the level of fortification. Fortifications

always have garrisons. Extremely few provinces

belonging to European nations completely

9

Page 12

Europa Universalis

lack fortifications, but there may be colonies

without them, or quite undeveloped provinces

at the very fringes of Europe. Fortifications are

not very common in the New World, but instead have loose confederations of tribes and

clans. This mean that somebody occupies almost every territory.

Strictly speaking, sea zones are not occupied.

Instead the struggle concerns the shipping

lanes. Anyone who is able to stop others from

using the shipping lanes therefore exerts a certain influence.

Colonization and Economy

The importance of a good economy cannot be

overrated. The economic wealth of your count ry determines how much of your re s o u rc e s

you can invest into various activities, from research to war. What then, are the cornerstones

of your economy? Most of your income will

come from production and taxes, which are

generated by your population. The population

lives in the provinces, which provides two main

paths that enable you to broaden your economic base: war and colonization.

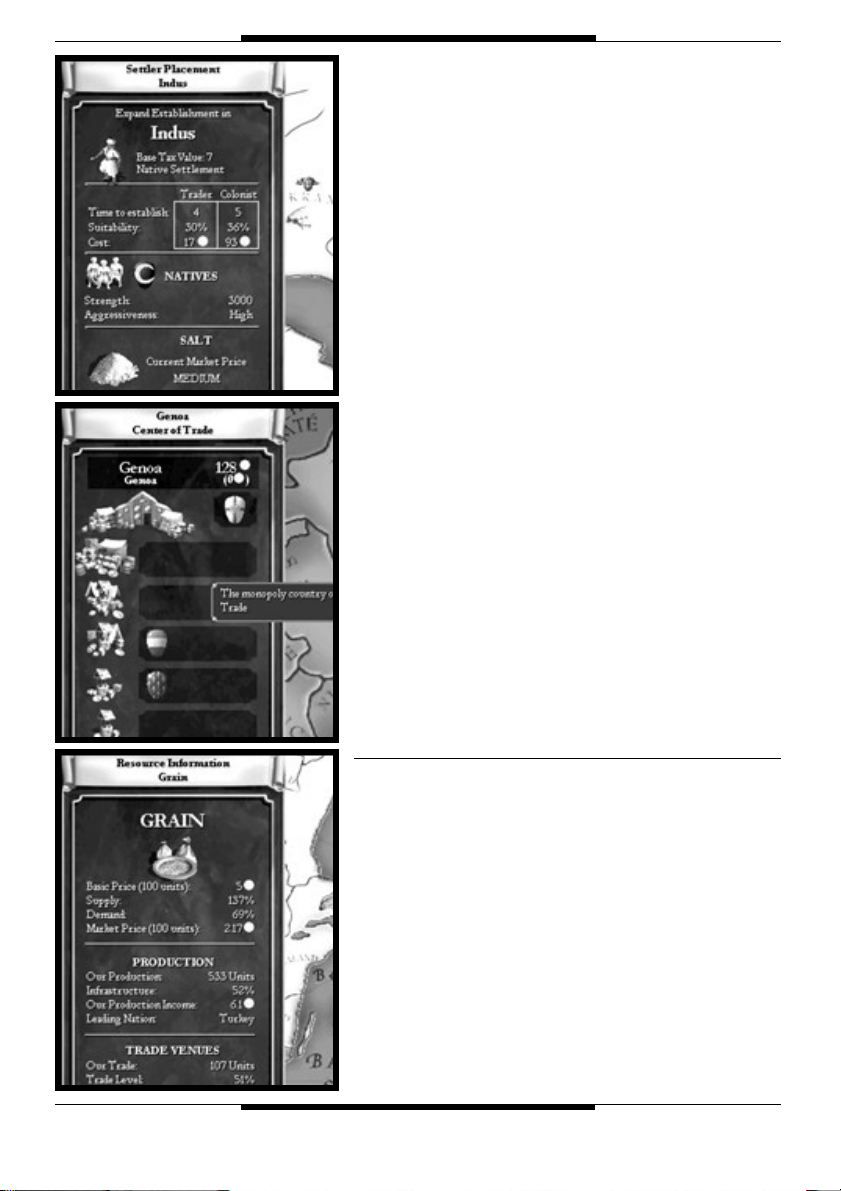

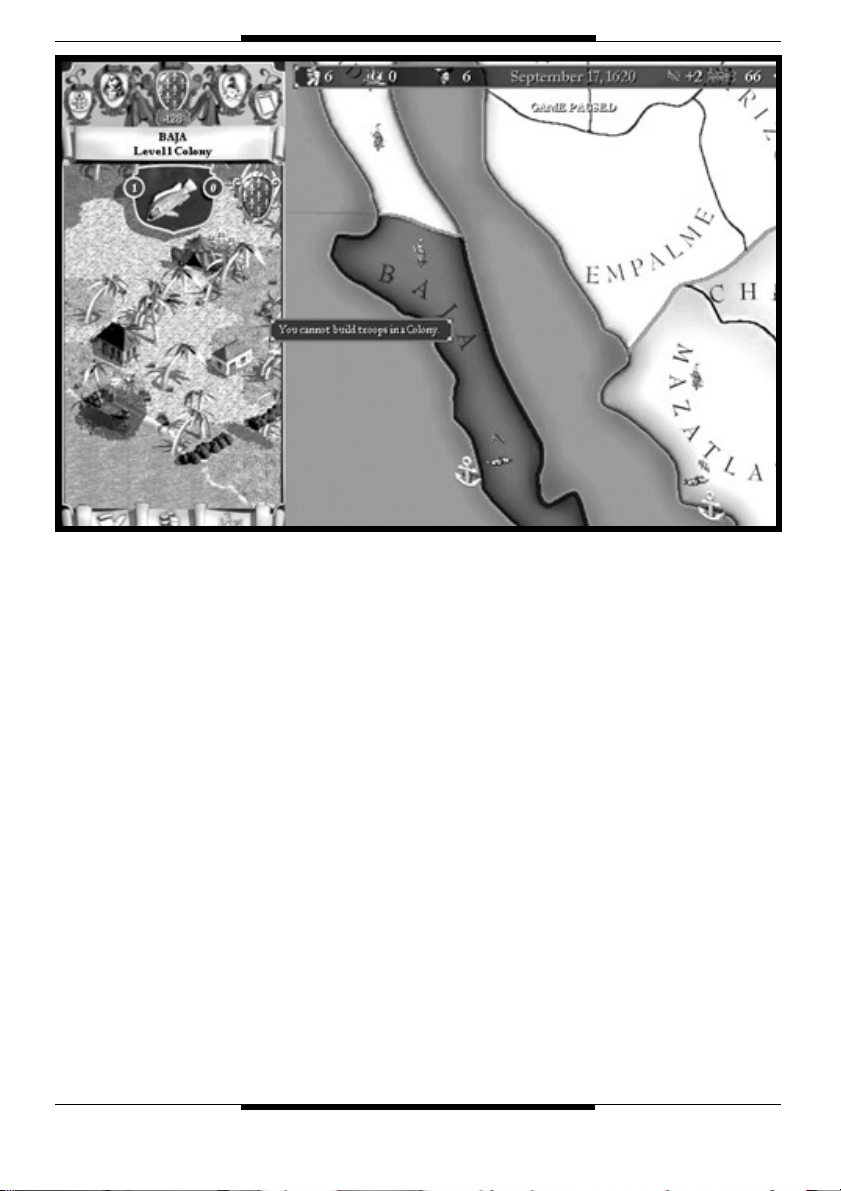

To Colonize a Province

When you click the colonization button (the

button that resembles a small, light blue ship),

the map changes to show which provinces you

can colonize (dark green) and which you cannot colonize (bone white). This is called the

Colonial map. When you choose a province to

colonize, information will appear in the Information window; that is where you choose

w h e re to send your colonists. Your colonists

may also be used as merchants, which will be

described later.

10

From HMS Mayflower to Cities

Colonies can be upgraded, and for each

colonist it is upgraded one level. A colony may

have up to six levels, where each level re p resents 100 inhabitants. When a colony reaches

700 inhabitants it is turned into a norm a l

province with a city. From then on you are able

to recruit troops and build fortifications in the

province.

Note that the economy of the province develops over time as the population grows. From the

moment you have established your colony, it ex-

Page 13

periences a monthly increase in population. It is

positive if the country has a high level of stabilit y, and negative if stability is low. This means that

a first level colony may develop into a pro v i n c e

with a city without you having to send more

colonists. Population growth will not be very

high, which means that such a development will

take a long time. A first level colony rarely produces any revenue, while a sixth level colony is

m o re or less a small province. Each colonist

brings along 100 people.

The colonist, the leader of the expedition

consisting of 100 people, always starts out

from your capital, and is portrayed as a horse

and carriage and as a small sailing ship. The further away from your capital, the longer it takes

to complete the actual colonization. When you

establish a colony it may happen that the

colony receives the state religion of your country, and that may be interpreted as the presence

of a number of priests among the colonists. It is

an advantage if the religion of the province is

the same as the state religion, as diff e re n c e s

may result in rebellions during times of unrest.

Europa Universalis

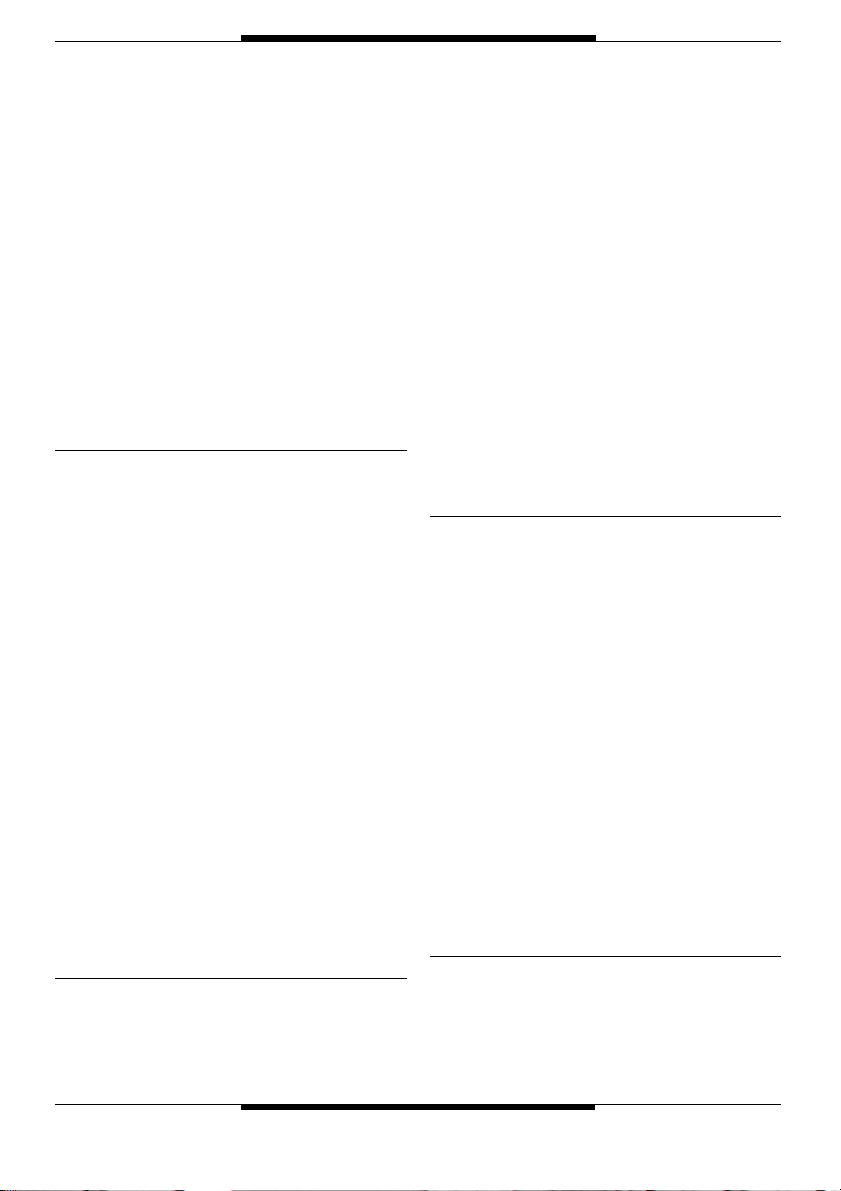

The Financial Summary

H e re you get an overview of the economic

state of your countr y. Remember that the entire economy is affected by the stability of your

c o u n t ry; low stability results in low re v e n u e s

and technology levels, while a high stability rating will optimize both revenues and development. You will also find that income will increase when you upgrade buildings and receive

higher technology levels in the areas of infrastructure and trade.

Be careful with inflation. Inflation increases

proportionally with the amount of money you

choose to receive each month (by minting

coins), and by taking loans from the citizens of

your country or from other countries. The

normal state, where inflation does not increase,

is when you do not take out a monthly income;

that is, by increasing the amount of coins in

your country. At that point you only have your

annual income available. Note also that gold

mines will increase inflation. If you have gold

mines you can never completely avoid inflation.

Your best cure against inflation is the Govern o r. By appointing mayors to governors you

lower the rate of inflation. Remember that inflation is relative—as long as the increases in

prices are lower than the increases in revenue, it

is not a bad thing, at least not in the short run.

The Budget Window

The state budget lets you decide on how to

manage your re s o u rces for development, investments in stability, and public consumption

in the form of appointments of officials, diplomacy, and the armed forces. This may be classified into three separate areas.

The first is research, which results in qualitative advantages. Military units get a higher

morale, better fire p o w e r, and greater impact.

M e rchants become more competitive and

make greater profits. Infrastructure provides a

higher degree of effectiveness in production.

11

Page 14

Europa Universalis

The second area is stability, which affects eve ry area of your country. Stability affects the

economy, troop morale, the risk of rebellion in

your provinces, and whether your vengeful

neighbors will think it wise to attack or not. If

anything is more important than other factors,

it must be stability. It also affects the total size

of your state budget, which means that total investments in technology will be lower over

time if you go along with a lower stability,

rather than investing in maximum stability.

Your third concern is public consumption,

or actually the expenditure of liquid assets from

your tre a s u ry on a monthly basis. You spend

these ducats on more troops, more war ships,

more colonists, and more merchants.

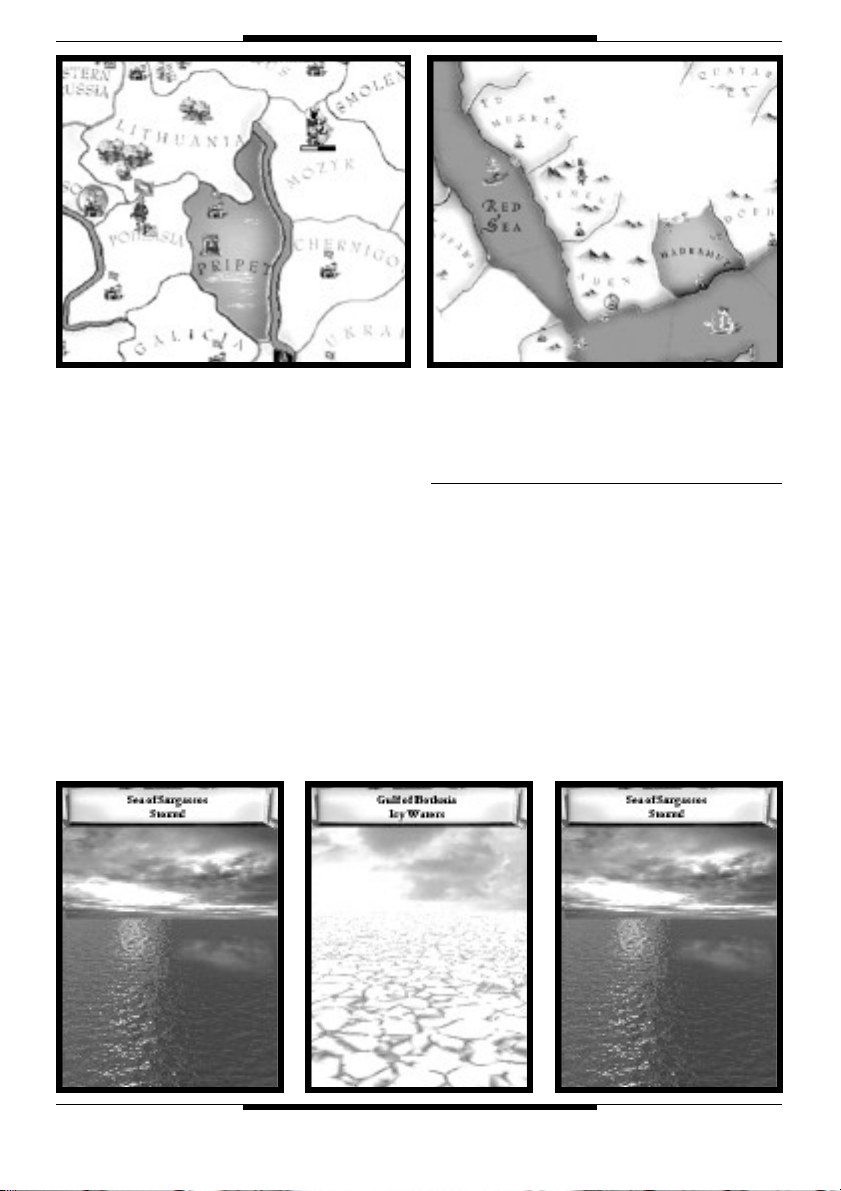

Trade and Merchants

Historically you could say that the global economy did not exist until the discovery of America. The easiest way of looking at the global

economy of that era is as a number of adjacent

local economies. These local economies were

connected to each other with sometimes weak,

and sometimes strong ties. The ties consisted

of course of the merchants, and the power connecting them was external trade. The greater

the number of local economies connected, the

m o re trade increased. When trade incre a s e d ,

both demand and supply increased, giving rise

to global trade over time.

Each province in the game belongs to a center of trade. Goods are exchanged at the center

of trade, prices are fixed, and profits and losses

are divided through the care of invisible hands.

Trade during the 1492–1792 period had much

stronger ties to the state and the monarch than

t o d a y. The merchants you send off into the

world probably belong to some public or semipublic trading company.

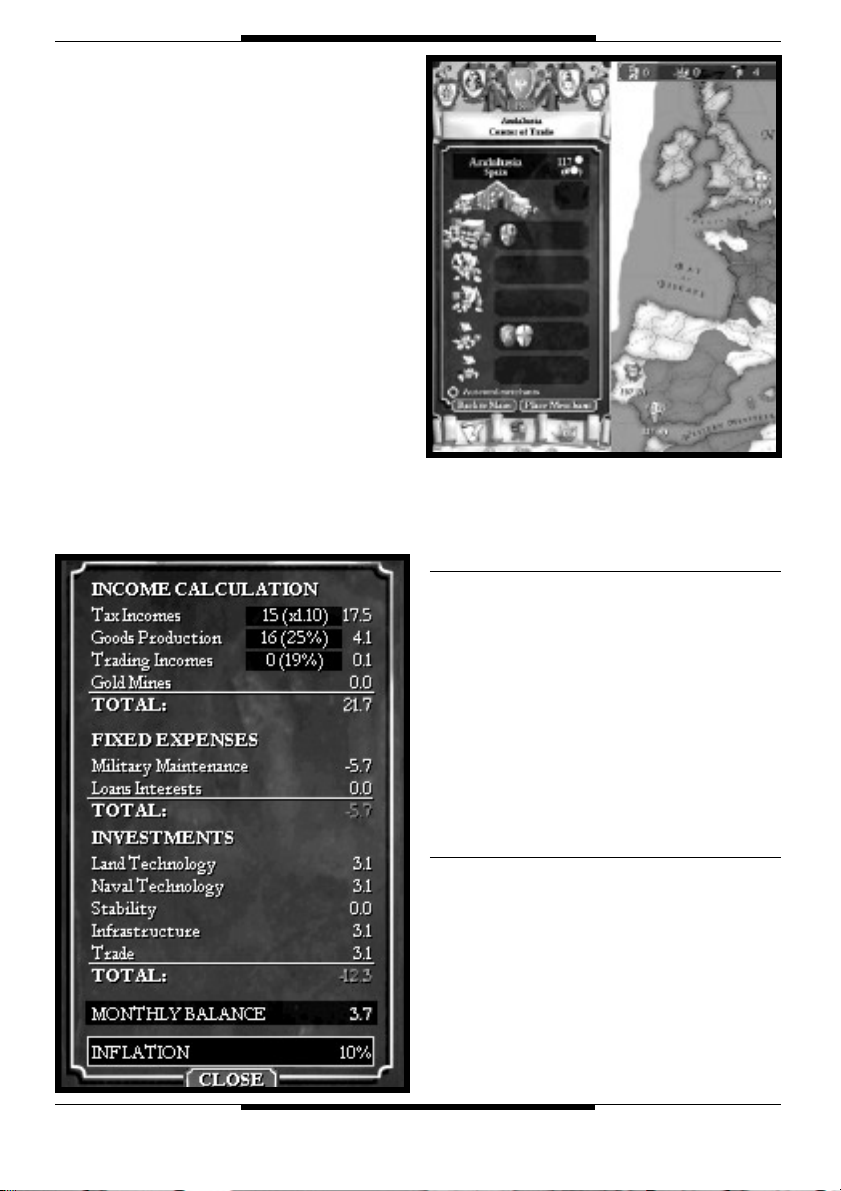

Placing Merchants

You may only set out merchants at your centers

of trading. In order to get there you click either

on the Trade button, or on the small trading

company in the province on your map. In this

case it’s Ulster.

Deploying merchants costs money, including their upkeep. It is more expensive to set out

and keep merchants abroad than in your own

country, and even more expensive the further

away from your own country you get. Each

m e rchant you have set out in the center of

trade provides a yearly income, depending on

the total trade value of each center of trade.

A center of trade covering a low number of

p rovinces, with commonly available goods

(such as fish, grain, and wool), has a lower trade

value and will provide lower revenues, than a

center of trade covering several provinces, trading with exotic goods such as ivory, slaves, and

spices. Your technological level will also aff e c t

the profitability and competitiveness of your

m e rchants. When many countries appoint merchants in the same center of trade a veritable

trade war may very well eru p t .

The Economical Effects of Trade

The economical effects of trade should not be

underestimated. A raised level in trading technology with lots of provinces and trading

posts, the trade centers will turn into veritable

gold mines for anyone managing to maintain a

monopoly. Additionally the effects of being the

leading producer of certain goods will provide

unimaginable profit, when war, rebellion, and

c a t a s t rophes strike the European continent,

changing all prices. Note also the importance

of having a center of trade within your own

c o u n t ry. New colonies and trading posts will

almost exclusively end up under the authority

of your own center of trade. This will increase

both your immediate profits, and also the trade

value of your center of trade. It is also easier to

be competitive in your own center of trade, but

more about that later.

Fleets and Sea Transport

The fleet is a military unit consisting of a vary i n g

number of ships in the same way that an arm y

unit consists of a varying number of tro o p s .

T h e re are three types of ship in the game: Wa rships, Galleys, and Tr a n s p o rt Vessels. Wa r s h i p s

have a transport capacity of 1; galleys have a

12

Page 15

Europa Universalis

t r a n s p o rt capacity of 0.5, and transport vessels a

capacity of 2. What is transport capacity? Each

a rmy unit has a weight; the transport capacity of

your fleet indicates how many troops you are

able to transport. Cavalry and art i l l e ry have

g reater weight than infantry. The total weight of

each army unit and the transport capacity of the

fleet can be found in the Information window

whenever you have selected a unit. War ships are

m o re effective in battle, galleys are the least expensive, and transport vessels have the larg e s t

t r a n s p o rt capacity. Galleys should be kept in the

Baltic Sea, the Mediterranean, and the Black

Sea, as this ship type is useless on the open sea.

All fleet units suffer "attrition" when at sea.

When you choose a fleet unit you will find the

current attrition speed in the Information wind o w. This is shown in connection with the

small skull. There is no attrition when a fleet is

in port, which means that you need to send

your fleets into port at regular intervals in order to maintain the ships. If a fleet transporting

army units is sent to port the army units will be

unloaded automatically in that pro v i n c e .

Merging, splitting, reorganizing, and dissolving fleets is done in exactly the same way as

army units are merged, etc.

Loading of Army Units

First you need to order your fleet into a sea

zone, and then order an army unit in an adjacent province to load onto the fleet. You cannot load the fleet unless it is in port.

When the troops are loaded you will find a

new button in the information window when

you choose the fleet. Click this button when

you want to unload the army unit in another

adjacent province.

Unloading an Army Unit from a Fleet

Choose the fleet and click the unloading button. You will now see the army unit on the

map. Now click the province where you wish to

unload your army unit. The troops will now

start marching to the province.

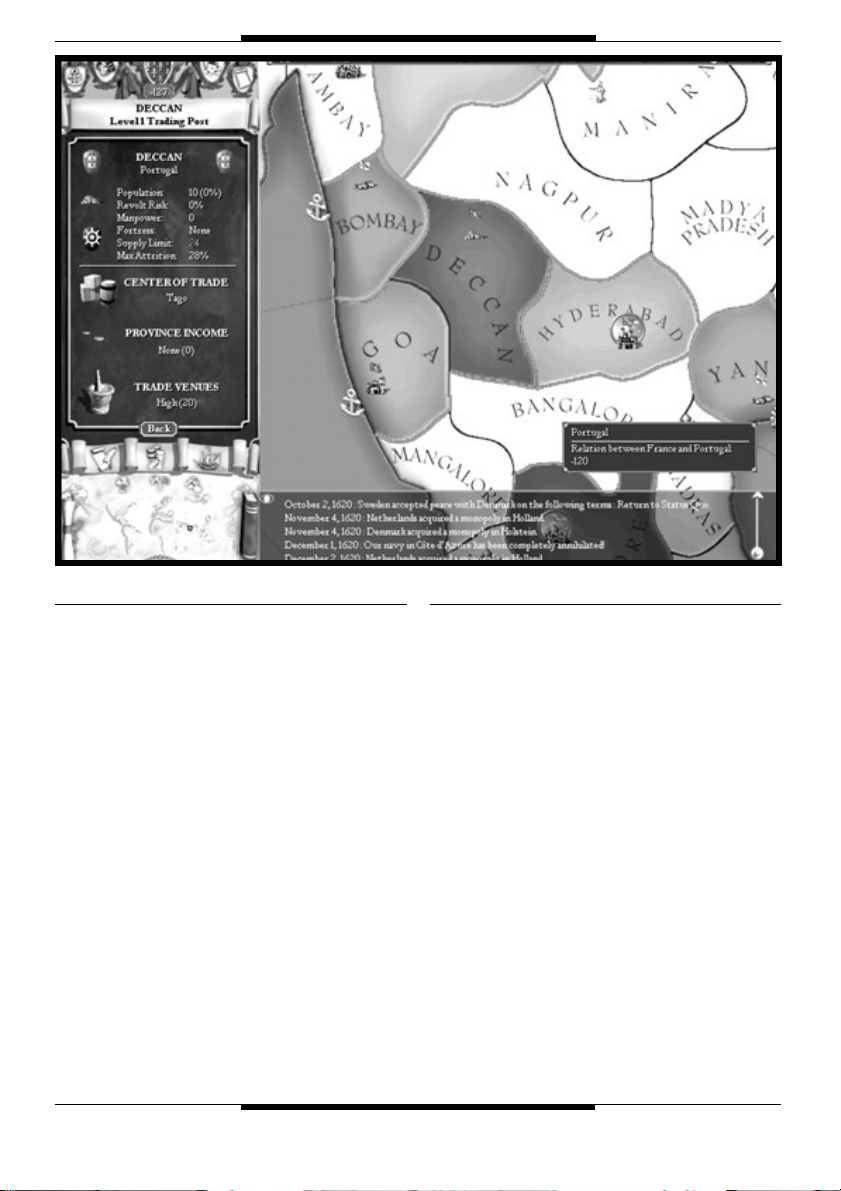

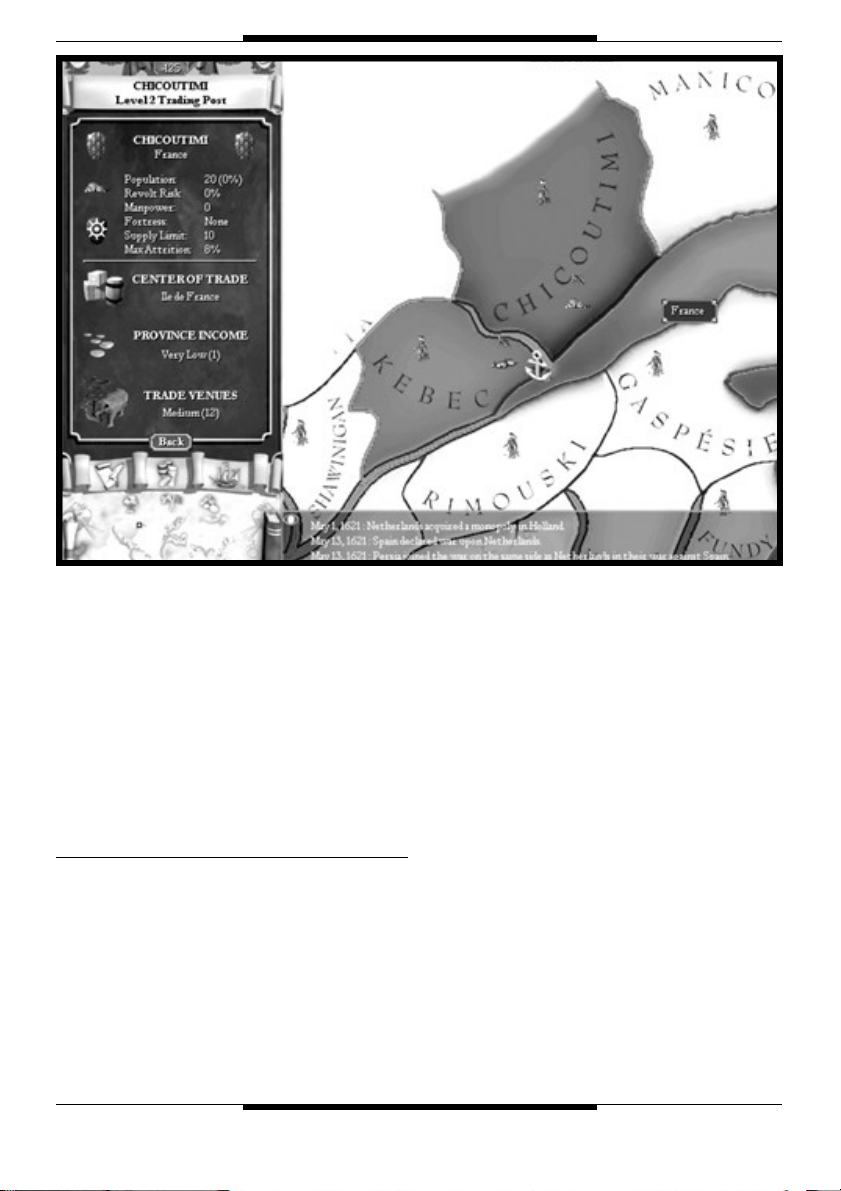

Trading posts

A colony is a province providing some produce

and a small amount of trade. Trading posts do

not provide any produce to speak of, but instead provide a better trade value affecting the

center of trade to which it belongs. By establishing many trading posts, preferably in

p rovinces producing unusual goods, you

quickly increase the trading value of the center

13

Page 16

Europa Universalis

of trade they belong to, and if you have a

monopoly or a large number of merc h a n t s

t h e re, you will receive good revenues fro m

your invested funds. The trading posts may be

improved up to six levels. At the higher levels

the trading posts have a great trading value.

You build trading posts by sending out merchants. Click the colonization button. As we

mentioned previously, you have some colonists

available—the number is shown in the line

above the map. These can be used either as

colonists or merchants. Historically the first

colonizations happened when the Euro p e a n

countries first established trading posts in an

area, and later on colonized it. Trading posts

are cheaper than colonies and are usually easier

to establish than colonies. It is also easier to

maintain a colony in a province where you already have a trading post, as compared with a

neutral and empty province.

How to Establish a Trading Post

Click the colonization button. Now you see

the map in its colonization view. Bone white

provinces are not available for colonization or

trading posts. They are either undiscovered, al-

ready fully developed provinces with more

than 5000 inhabitants, or belong to other

countries. Possible prospects are all of the

green colored provinces. If the province is dark

green, you already have a colony there, if the

color is medium green, you have a trading post,

and if the color is light green, you have neither.

Click the province where you wish to establish

a trading post, and then click the button "Send

merchant." You will now see a figure unpacking pots from a chest as a sign of work in

progress. When placing the pointer above the

merchant you will see how long it will take until the trading post is ready for business.

Neighboring Countries

Your neighbors are naturally of great interest to

you, whether they are your allies or your enemies. Normally you know about your European neighbors and their provinces, but usually you know nothing about the non-European

countries. You must discover them. You are also only able to send diplomats to a country if

you know about it, and diplomacy is one of

your most important tools for survival and expansion.

14

Page 17

Europa Universalis

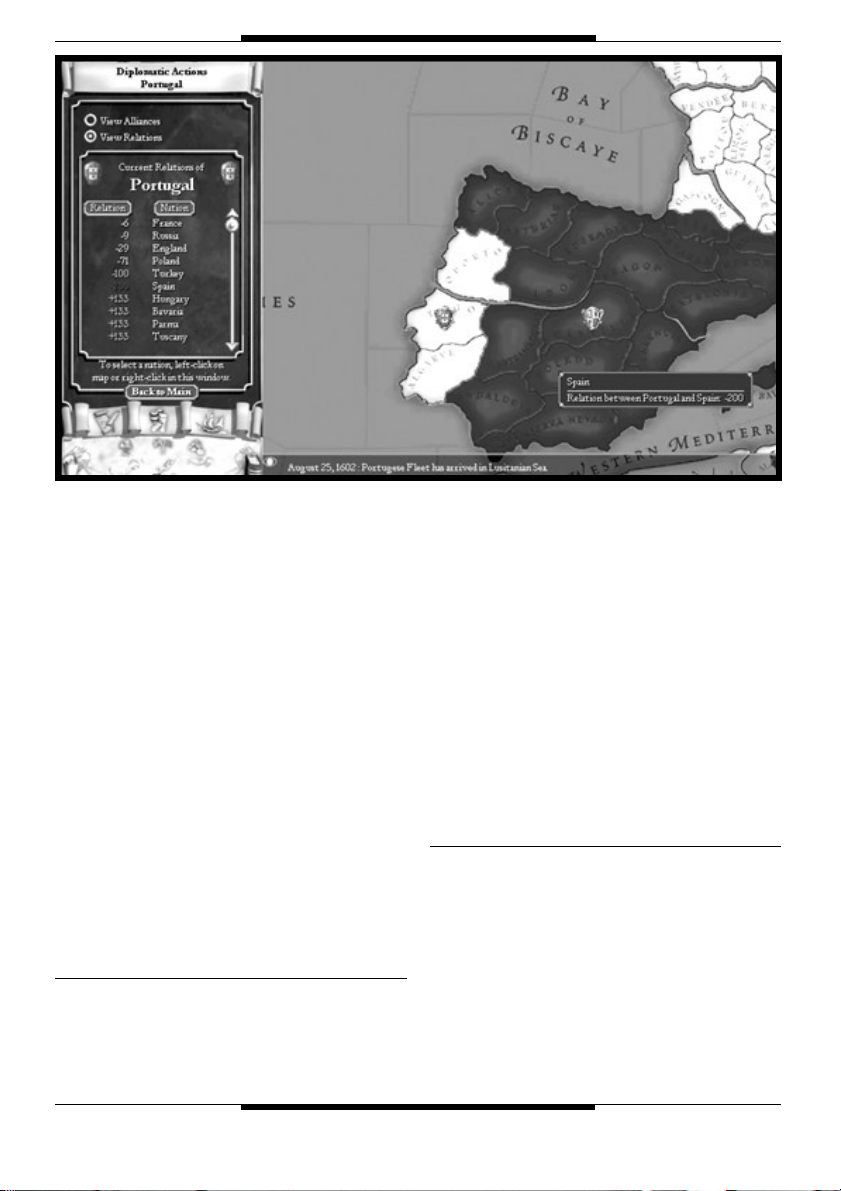

Diplomacy

Diplomacy can be used in many ways. The

diplomats you send out are your tools when

you want to achieve something. What is it you

want to achieve? You can offer royal marriages

or alliances, or take up such offers. You may dec l a re war or offer peace. You may try to exchange geographical knowledge, and you may

c reate better relations to other countries

through gifts and tokens of respect, or worsen

relations through insults and bans.

Royal marriages are a good thing. They imp rove relations and make it difficult to carry

out declarations of war. The alliances you enter

are also important, as you will easily fall prey to

other alliances if you do not belong to any. It is

quite possible to defend yourself against another power, but if three, or even four, other countries attack, you are in deep trouble.

In order to use diplomacy you click the

diplomacy button below the information wind o w. This opens a diplomacy menu for your

country. You may look at another country on

the map at any time. By clicking the "coat of

a rms" of that country you may review the

diplomatic situation of that country. You have

a number of choices in your diplomacy menu.

By clicking an option, that diplomatic mission

will be performed and you will have one diplomat less. Note that if you make an offer of royal marriage or an alliance the monarch will not

automatically accept the off e r. The deciding

factor for such a decision is your previous relations. If you have attacked and occupied a

number of small and innocent countries your

surroundings will naturally treat you like an international pariah.

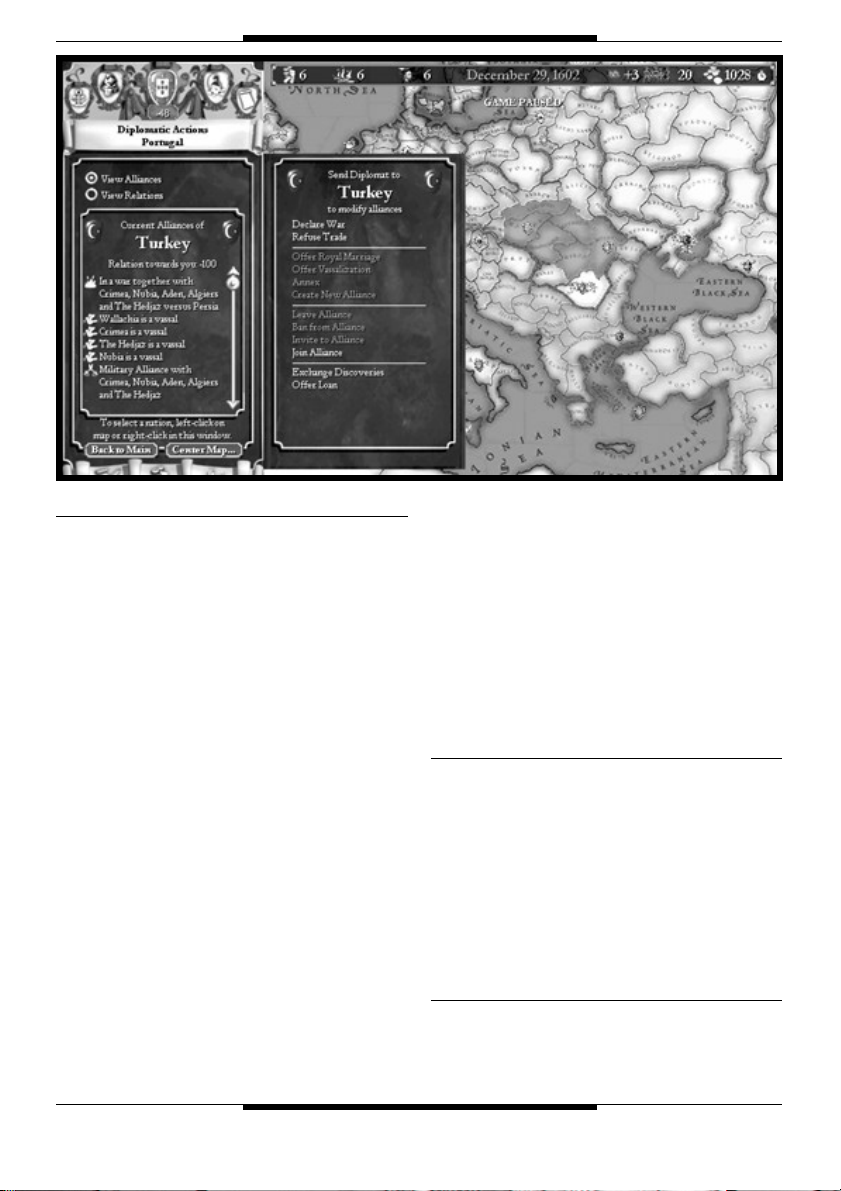

War

War is one of the fastest and best ways of expanding politically and economically. War also

has its share of disadvantages. Your re s e a rc h

will often suffer, as you probably need to invest

heavily in stability after each war. Wars almost

always destabilize your country. War also affects the risk of rebellion in your provinces. A

land with multiple religions often risks a "great

mess" each time a war drags out in time.

To Prepare for War

B e f o re you declare war you need to pre p a re .

This usually means that you expand your

a rmies and fleets in order to obtain local

s u p re m a c y. You should also compare your

15

Page 18

Europa Universalis

strength to the strength of your potential enemies. If you are well pre p a red you suffer less

risk of having to finance your war with war taxes and increased minting of coins. Note that attrition is higher for army units that are moved

during the winter months. Plan your war accordingly. It is also important to consider the

allies of your potential enemy, and trying to figure out how your own stability will be affected.

On the one hand you check to see if you have

any Casus Belli (Latin for "cause of war"),

which will decrease your loss of stability because of the declaration of war, and on the other hand by declaring war and then "regretting

the act." When you declare war you are informed of the size of your loss of stability and

what caused it.

To Declare a War

War can be declared either from the diplomacy

menu, where you go to the country in question

and click the line "declare war," or by honoring

an alliance where one of your allies either has

declared war on another country, or has been

attacked.

To Win a War

In order to win a war you must be victorious in

battles and naval engagements and/or capturing the provinces of the enemy. You capture a

p rovince by moving an army unit into a

p rovince, defeating any enemy units in the

province, and performing a successful siege or

assault. When your flag is waving above the

town, colony, or trading post of the province,

you control it and this will be counted to your

advantage during peace negotiations. Note

that the opposite is true for your opponent,

which means that you should try to avoid losses in battle and try to hang on to your

provinces. Extended wars lead to exhaustion,

which often results in rebellion in your various

provinces.

Offers of Peace

In order to make an offer of peace you click a

p rovince belonging to (or that has belonged

to) the enemy. Then click the diplomacy menu.

H e re you click on the line saying "Offer of

Peace." Here you see the results of the war,

through the number of stars or tombstones in

the information window. If you see tombstones you should consider offering a tribute

16

Page 19

Europa Universalis

and/or provinces in order to gain peace. If you

find stars you may often demand a tribute

and/or provinces. Each star or tombstone represents a province or 250 ducats, which you either may offer or demand. You may only offer

to give up provinces, which have belonged to

you, and are now controlled by the enemy, and

you may only demand provinces, which have

belonged to your enemy, and now are in your

c o n t rol. If you demand provinces that belonged to your enemy at the start of the scenario, that is, his or her core provinces, the enemy now has a Casus Belli (cause for going to

war) against your country.

C) Activities

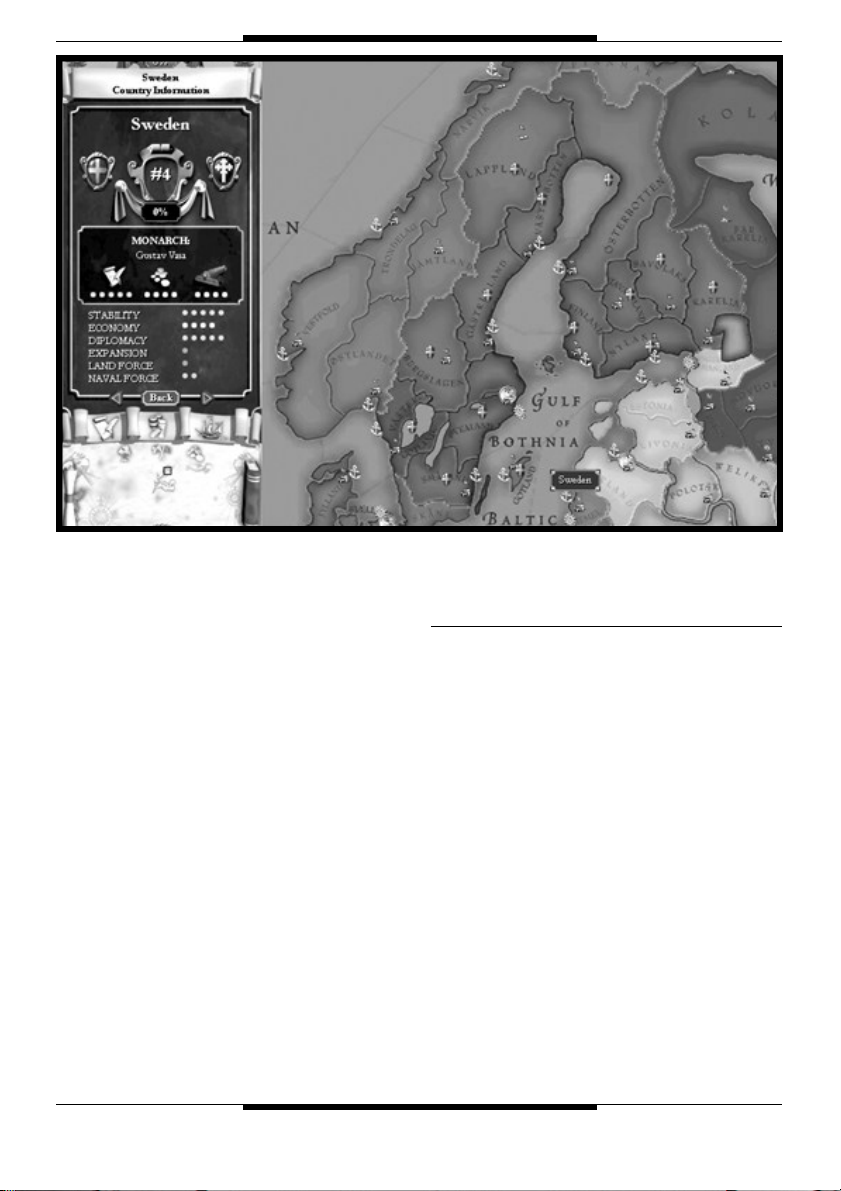

Countries

Each player runs a country. Each country consists of one or several provinces and possessions

(the diff e rence will be explained later). Yo u r

country has a border marked on the map, and if

you wish to view the political map, the

provinces of each country are marked with the

same color. Each country has a monarch and a

state religion. Most of the countries are located

in Europe, but there are a few non-European

countries spread out in the world that may be

included in the game. Certain countries have a

special political status - these countries may be

played. Each scenario defines the countries you

a re allowed to play. The diff e r ence between

player countries and other countries is that a

player country may not be occupied as the result of a peace treaty or through diplomatic

means (see Peace Treaties and War Damages).

Provinces

The province is the smallest geographical unit

of the game. There are two types of political

status for the provinces. They either belong to

a country, or they are independent. Your country consists of provinces belonging to you. The

p rovinces are fully developed, as opposed to

possessions. This means they have cities, where

you may appoint officials, and where you may

build ships and raise army units. Possessions

are provinces that lack a city, but have either a

colony or a trading post. Any province that

does not belong to a country is an independent

province. These provinces only exist outside of

Europe, and are populated by natives, organizing their societies through clan and tribal systems. The independent provinces do not have

17

Page 20

Europa Universalis

standing army units; instead native war bands

will meet you if you move an army unit into the

province. You may colonize or construct trading posts in independent provinces, there b y

gaining a certain level of control. Only countries may have a colony or a trading post in an

independent province. When a colony or a

trading post is established, the province is no

longer considered independent. A basic difference between a province with a city and a

p rovince with a colony is that you can build

ships and raise army units in the former, including appointing officials, and establishing factories. You may not do any of this in a province

with a colony.

A coastal province is a province with a port.

Note that in order to have a port the province

must either have a city or a colony. A province

with just a trading post may never have a port.

Having coastal provinces also affects the number of colonists and merchants your country

will receive each year. Also note that ships do

not suffer attrition when in port, because they

can be maintained. If you have a large country

with provinces on several continents, you will

18

do better if you have ports in as many places as

possible, in order to send your ships in to port

now and then, to avoid suffering attrition (See

Attrition). The provinces you start the game

with are your core provinces and your most imp o rtant ones. Core provinces are marked on

the political map with small shields. The country a province belongs to is noted by the flag

waving above the city, the colony, or the trading post. During times of peace you may only

move your army units from and to provinces

belonging to your own country, or into independent provinces. During times of war you

may also move army units into provinces belonging to allied countries and dependent

states, and into countries with which you are at

war. There is also one exception. The Emperor

of the Holy Roman Empire may freely move

his army units within the borders of the Empire

(see The Holy Roman Empire).

Note that a province may belong to one

c o u n t r y, but may be controlled by another.

This happens when two countries are at war

with each other, and one of the countries has

occupied a province belonging to the other

Page 21

Europa Universalis

c o u n t r y. When peace has been declared, all

c o n t rolled provinces re t u rn to the original

o w n e r, unless they have been surre n d e red as

part of the peace treaty. There are two exceptions. The first depends on whether you have

signed the Tordesilla Treaty or not (see The

Tordesilla Treaty), because you may then move

into and take control of the colonies or trading

posts of other countries, regardless of whether

you have been at war with these countries or

not. The other exception applies if rebels manage to seize one of your provinces. The

p rovince still belongs to you, but the re b e l s

control it. If another country controls any of

your provinces, you will not receive any income

f rom these provinces. You will see that a

province is controlled by another country if the

flag of another country is flying above the city,

the colony or the trading posts. (Rebels fly a

red flag.) In order to take control of a province

you must capture the city, either by storm or

siege. Provinces with cities lacking fort i f i c ations, and provinces with colonies or trading

posts are automatically controlled when you

move an army unit into it. Also note that

provinces under your control will be counted

to your advantage during peace negotiations.

Sea Zones

The seas are vast open areas. During this period

the chances of controlling the seas was limited

by the quality of the ships and their crews, the

basic resources, and of course the weather. The

sea is therefore divided into sea zones. Each sea

zone is an area where fleets have a limited influence. Each fleet actually consists of a main part

and several smaller patrols. When the patro l s

discovered enemy ships, the main part of the

fleet was assembled to deal with the enemy

fleet. This means that battles between fleets do

not occur automatically; this depends on the

quality of the fleets. The main problem was

finding the enemy and creating local superiority. If you did not succeed the engagement was

called off. Your territorial waters are the sea

zones off the coast from your coastal provinces.

Here you have several advantages, as you know

the waters, the weather, and you are close to

your bases for maintenance.

19

Page 22

Europa Universalis

Cities and Capitals

Your capital is shown on the map. This is the

city belonging to the province where you find

your shield. The province with your capital

may not be surrendered during peace negotiations other than by occupation (see Peace

Treaties and War Damages). The city shows a

graphic representation of the level of development of your province. What you see in the inf o rmation window is a picture of the city, as

you build ships, raise army units, upgrade

buildings, and build factories. The population

level of your city indicates the wealth of your

province. Normally the population of the city

will increase over time, but it may also drop because of war, rebellions, random events, and if

the city is situated in an area of adverse geographical conditions, for example in the

African tropics. When a colony has 700 inhabitants it develops into a city. The city is still colonial, and in order to become a real European

city with efficient production the pro v i n c e

must have at least 5000 inhabitants.

20

Trading posts and Colonies

When you have established a trading post or a

colony in a province you gain control of the

province. In other words, the province is now

yours. This means that no other country may

use the province for troop movements during

peace, and no other countr y may establish

trading posts or colonies in the province. You

may lose your province either through negative

population growth because of the geographic

conditions, which will make your population

drop to zero, or by ceding the province to another country as part of a peace treaty. You may

also lose a trading post either because an enemy

army unit burned it to the ground during war

(see Trading Posts and Merchants), or by ceding the province to another country as part of a

peace treaty.

Trading posts and colonies are called possessions, and are diff e rent from provinces with

cities, partly because of population levels, and

partly because of the development levels. The

difference between a trading post and a colony

Page 23

Europa Universalis

is that the trading post provides a low production value and a high trading value, while the

colony provides a high production value and a

low trading value. In addition the colony has

population growth and may be developed into

a city, while a trading post does not have population growth, nor may it be developed into a

province with a city. You may still develop your

trading posts into colonies by sending colonists

to your trading posts.

Terra Incognita and Permanent Terra

Incognita

Both "Terra Incognita" and "Permanent Terra

Incognita" are undiscovered areas. Te rr a

Incognita re p resents provinces and sea zones

not yet discovered by your countr y. When

these are discovered, either by moving arm y

units or ships through them, or by trading

maps with other countries, the areas cease to be

Terra Incognita and become part of the known

world, as your country knows it. Note that you

n o rmally need a Conquistador, or you must

have reached Land Military level 11 in order to

discover provinces. For undiscovered sea zones

you need an Explorer or you must have

reached Naval Technology level 21.

P e rmanent Te rra Incognita re p re s e n t s

undiscovered areas not consisting of provinces

or sea zones. Permanent Terra Incognita comprises the areas that were not explored at all at

this time. Historically, there were several areas

that were not discovered until after 1792 (such

as some parts of Siberia and Australia), or

which had been discovered earlier, but where

all knowledge about it had faded into legends

(such as the interior of Africa), and finally areas

which could not be explored using the technology of the times (such as certain Northern

sea routes).

21

Page 24

Europa Universalis

Stability and the Wrath of

Your Subjects

What is Stability?

The political culture of Europe during the period was not an isolated phenomenon. How

each country should behave in regards to both

domestic and foreign policy had already been

f o rmulated during the height of the Roman

Empire, and had later been developed during

the Middle Ages. The ideological start i n g point at the end of the 15th century was Christianity as a unit. Civilization was defined within

the framework of Christianity and consequently, what constituted civilized behavior between

countries. A similar starting-point existed in

the Moslem countries, where "country" was

not a properly recognized concept. Instead

they re g a rded all Moslems as part of the

Moslem Haram. Internally the division of society was frozen, partly because of the division of

power between various groups during the late

Middle Ages, but also through domestic policy, which could be described as a struggle or

game between various groups in society. The

monarch naturally played a large part.

You should also be aware of the advantages

associated with breaches against "the international rules." The princes of the Renaissance

were soon involved in a highly advanced game

of political struggle, where a European hegemony was the goal. In this aspect you should

consider the abstract concept of stability. If the

monarch broke the formal and informal rules,

both his foreign and domestic reputation fell,

including the status of his country. The response to declarations of war was often your

own declarations of war, which caused a spiral

of injustice, war, and revenge that affected all

of Europe.

Stability is thus affected by both the international status of your country, and by the relations between your monarch and his subjects.

The stability of your country may vary on a seven-point scale from –3 to +3.

Things that Lower Stability

There are several reasons why stability may deteriorate, but the most important are definitely

declarations of war. Declarations of war were

not regarded lightly by anyone in Europe during the period, perhaps with the exception of

the issuer. In other countries the monarchs and

the governments viewed any declaration of war

with concern, because it might upset the balance of power of the region. You could say that

society viewed the country as a person and the

declaration of war as a physical attack. Yo u

could make this attack if you had good and

proper reasons (see Casus Belli), but uncalled

for wars were punished by force. As a result of a

declaration of war, you could lose prestige and

international honor. Add to this the quite negative reactions of the population, as war meant

levies, inflation, and raised taxes. A declaration

of war without Casus Belli lowers the stability

of your country by two steps (–2). A declaration of war with a proper Casus Belli does not

affect your stability at all. Religion was something that united and divided countries during

the epoch. It was thought of as an un-Christian

and therefore it was immoral to declare war on

a country with the same religion, which meant

that the population and the priests re a c t e d

quite negatively if any monarch chose that

route. A declaration of war against a country of

the same religion lowers your stability an additional step (–1). To declare war against an allied country was seen as truly degenerate behavior, lowering your stability yet another step

(–1) if the country under attack has ties

through a royal marriage with yours. If you declare war against your own vassal your stability

will drop another three steps (–3), while ending your vassal ties without a declaration of war

lowers stability by three steps (–3). If you dec l a re war against a country with which you

have a peace treaty, your stability will drop by

another five steps (–5); in effect, this means

that you will become an international pariah.

Peace treaties remain in effect for five years.

Some other important factors that lowered

stability during the period were various politi-

22

Page 25

Europa Universalis

cal acts of a dubious nature. Breaking your foreign promises immediately lowered the reputation of a country and its prestige. The principle

of "Pact Sund Servanda" (agreements are

binding) was a basic rule already in Roman law,

and had been incorporated in the diplomatic

life of the times. Annulling a royal marr i a g e

could be a good thing for your country in

many ways, but the stability of your country is

l o w e red by one step (–1). You are seen as

flighty and insecure in your foreign relations,

which is cause for strong irritation among any

groups of society with strong connections with

the country in question. If you decide to sack a

vassal your stability is lowered by three steps

(–3). Especially the nobility will question your

f o reign competence. A vassal has subjected

himself to your decisions, even though this is

mostly of a formal nature, which means that

dissolving the relationship is regarded as a sign

of your weakness. If you leave an alliance your

stability is lowered by one step (–1), which

means that many powerful men in the upper

levels of society probably have invested a lot of

prestige and friendship in the alliance that you

are leaving. The same thing occurs if you refuse

to honor an alliance; for example, if you do not

help a brother when a third country attacks

him. It will lower your stability by one step

(–1). Sharp foreign turns will create uncertainty about your future direction in the political

game. If you refuse a country the chance to

trade at your trade centers you also lower stability by one step (–1). Your neighbors will feel

threatened, because what you did against one

country may be repeated against another.

Finally, there are five general causes for lowered stability. The first occurs if your country

goes bankrupt. Bankruptcy occurs if you have

taken out five loans from the national treasury

(loans from other countries are not counted),

and you are unable to repay them when they

are due, or when you have taken out five loans,

and your monthly costs are higher than your

monthly income. With bankruptcy the stability

of your country is lowered by one step (–1).

The population has lost confidence in the abil-

ity of the monarch and the government when it

comes to handling your finances. The same

thing applies when you are unable to repay a

loan from another country, as your stability is

lowered by one step (–1). Stability is also lowered if you decide to raise war taxes (see War

Taxes), which means that you further increase

the burdens of your country while lowering

stability by one step (–1). The fourth reason is

a change of state religion. Changing state religion normally means a huge transformation of

society, affecting every level of society. Some of

your subjects will celebrate, while others will

stage a revolution. Changing the state religion

lowers your stability by five steps (–5), except if

you change from the Catholic Church to

Counter Reformed Catholicism. (For a longer

description, see Religion.) Finally some random events may lower the stability of your

country (see Random Events).

Please also note that all effects are cumulative; that is, if you have a stability of 0, and dec l a re war against a country without a Casus

Belli, and in addition you have ties to that

c o u n t ry through royal marriage, and a peace

t re a t y, this will lower your stability by eight

steps (–2–1–5=–8). As mentioned earlier, you

may not have a stability of less than –3, but for

each additional step you will suffer an automatic rebellion in each of your provinces. In this

case your stability will drop from 0 to –3, and

then you will have 5 rebellions in each of your

provinces.

Things that Increase Stability

You may increase the stability of your country by investing in stability in your state budget

(see Investing in Stability). This is handled as a

c e rtain sum set aside for this purpose each

month, which you may view in the information

window. Note that the cost of increasing stability is higher if you have a large country, as you

must appease more people. When the gre e n

line has reached its end the stability of your

country is increased by one step (+1), and the

green line starts anew at the beginning. This is

to be interpreted as the monarch and the gov-

23

Page 26

Europa Universalis

ernment making concessions to various groups

of society; for example, a temporary lowering

of taxes for the peasants, land grants for the nob i l i t y, trading rights for the townsmen, or

greater freedom for the serfs. You may also see

the cost as part of certain actions, like replacing

b a i l i f fs, changing the laws, etc. Finally they

may cover the cost of raising the prestige of

your country; for example, by holding splendid

weddings, raising the magnificence of the

court, etc. You cannot raise stability above +3

by investments. The rate of increases will be

lower if you are at war, for each quarter you

have been at war, and for each province cont rolled by the enemy (core provinces are

counted twice and the capital is counted as ten

normal provinces). All investments made when

your stability is at +3 will result in ducats for

24

your treasury. Note that certain random occurrences may raise stability (see Random Events).

When you are victorious at war, and have managed to annex formerly independent countries

(see Annexation), your stability will increase by

one step (+1), as your victory will increase your

international prestige and make a big impression on your subjects.

What Is Affected by Stability?

To begin with, all population levels of your

cities and your colonies and all your monthly

and annual income are affected. During bad

times with spreading unrest the population often decreases. If your stability is low you are

p robably at war with another country. Yo u r

population is decreasing through levies, people

running off into the woods, and because of

Page 27

Europa Universalis

plagues that were often a result of the wars. In

game terms you will be able to view the percentage of increase or decrease of your population by clicking the church of a province. If

conditions are really bad, cities and colonies

may have a negative growth, which means that

they are being depopulated. Population levels

d e t e rmine the production income of your

p rovinces, which means that stability will determine the long-term development of your income. The administrative system is also less effective when there is unrest. Bailiffs were not

obeyed, roads and communications deteriorated, and people evaded their taxes to a greater

extent, resulting in a higher cost of living with

l o w e red consumption and production. This

will mean that your tax income will incre a s e

and decrease in pro p o rtion to your stability.

You see this as changes in your annual income

and also by checking up on your Financial

Summary.

Trade is also affected by the same phenomena.

Declines in both domestic and foreign trade

were common during wars and during periods

of unrest in general. This is portrayed by a connection between your annual quota of merchants and your stability. If your stability is at

the lower end – that is, –3 or –2 – you will have

g reat difficulties getting the merchants to do

business; they will simply lack all incentive to

trade, which lowers your pool of merchants by

two (–2). If your stability is at –1, your pool is

lowered by only one merchant (–1). If stability

is at 0 or +1, you gain one (+1) or two (+2) extra merchants. If the stability of your country is

excellent, +2 or +3, you gain three extra merchants. In addition, stability affects the ability

of the merchants to get into the trade centers,

as well as their ability to compete with merchants who are already present. Note also that

the annual interest of your loans varies along

with your stability.

Your diplomatic skills and the risk of rebellion

are also affected by the stability of your count ry. When it comes down to your diplomatic

abilities, you may not declare wars if your stability is at the very bottom (at –3). This is part-

ly due to social unrest and the fact that court

intrigue is at such a high level that the monarch

and the government are unable to deal with

anything other than trying to keep the country

united. To fight a war at such a time is impossible. The risk of rebellion in your provinces is in

direct proportion to your stability. The lower

your stability is, the greater the risk of re b e llions, and vice versa. You can read more about

this later in the manual.

Rebellions and the Risk of Rebellion

Rebellions were fairly common during the period, primarily during the early part, the 16th

and 17th centuries, while decreasing in scope

and frequency during the later years. There are

several reasons for this. Normally re b e l l i o n s

w e re caused by social or religious injustices

against the broad base of society, known as

"peasant uprisings." A fortunate start of a rebellion re q u i red leaders and even administrators in order to compete with the governmental power, and this is where the nobility and

prominent townsmen entered the picture. Any

successful rebellion re q u i red that all levels of

society got involved if they wanted to change

social reality. A few such "successful" rebellions

are the war of liberation of Gustavus Vasa, and

the French Revolution, but even properly organized and solid rebellions could fail in the

end. The fewer rebellions at the end of the period were usually due to the fact that few rebels

had access to the modern weapons technologies available to the government, and the inc reasing difficulties in uniting diff e rent social

classes. The arm of the government had become longer, and its grip was also much

stronger.

The risk of rebellion varied from province to

province. In order to review the risk of rebellion as a percentage value, click the church of

the province and point at "Risk of Rebellion."

You will then see what the risk is, and what is

causing it. You may also look at the map showing religions, where you see all provinces with

various levels of shading. The darker the shad

is, the greater the risk of rebellion. The two

25

Page 28

Europa Universalis

most important causes for rebellion are the level of stability and the level of tolerance of the

monarch and the government toward the religion of the provincial population (note that a

p rovince may have another religion than the

"state religion" – see "State Religion and

Provincial Religion). The risk of rebellion is in

direct proportion to the stability and the level

of tolerance; that is, the lower the values, the

g reater the risk of rebellion, and vice versa.

T h e re are also a few general factors aff e c t i n g

the risk of rebellion. The risk is always lower in

the province with your capital, because the

monarch and the government have much better political control, compared with the other

p rovinces. If you have built a factory in the

province the risk is lower as the population has

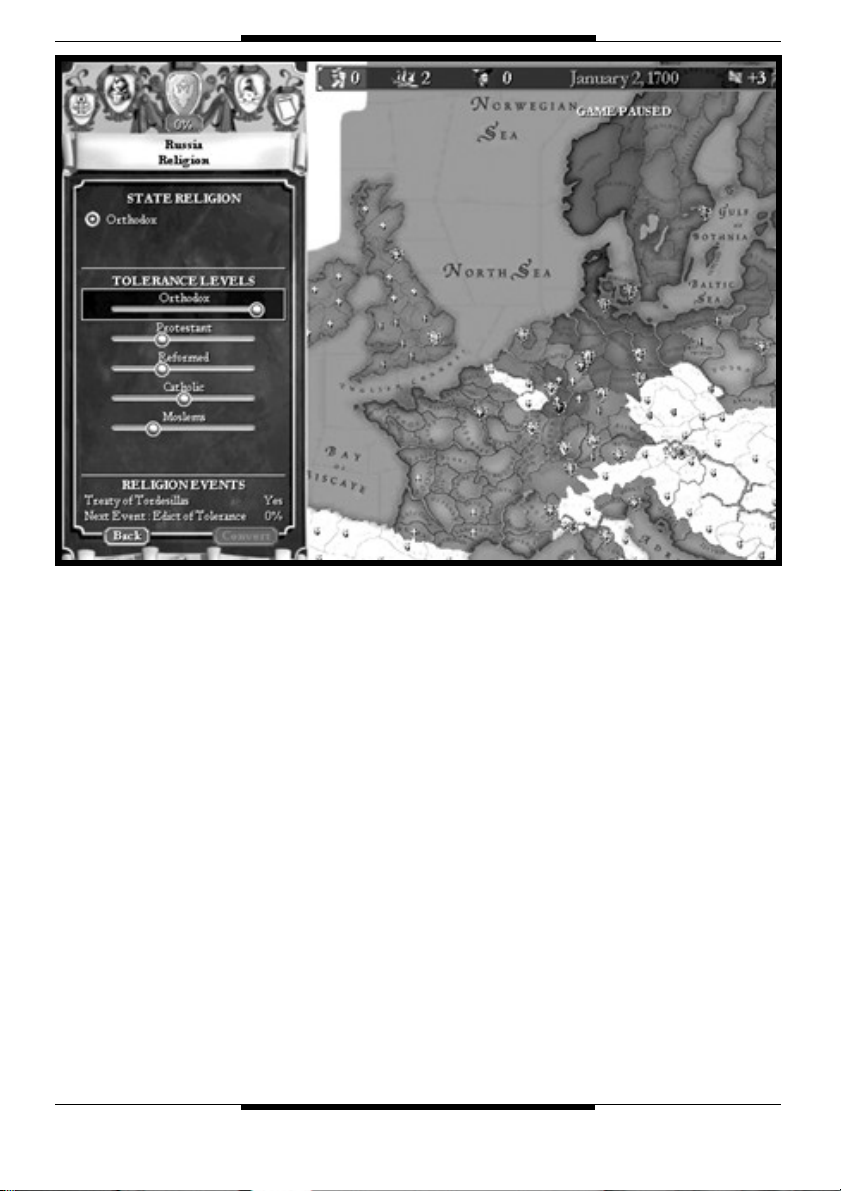

a higher production, which results in a higher