Page 1

Page 2

GAMEMASTER'S INTRODUCTION

The gamemaster has three tasks in STAR TREK: The

Role Playing Game. He must design the encounters, present

them to players, and judge the resulting action. This book

contains information to help him with these tasks.

Included here is a chapter giving information for designing encounters. In this chapter are systems allowing the

gamemaster to design encounters in "space... the final frontier." The gamemaster will be able to design "strange new

worlds" for the players to explore and "new life and new

civilizations" for them to seek out. Included is a section giving

new gamemasters hints to help them with their own designs.

There is a chapter giving hints on presenting scenarios,

on the art, if you will, of being a gamemaster. This includes

how to create descriptions that will excite players and how

to use all types of game aids, including maps.

In the chapters giving information on judging the action,

the gamemaster will learn how to interpret and judge the

rules. Some of this information will be repeated from the

player book so that the gamemaster does not have to flip

back and forth, but much of it will be new. In this section are

given the tables and specific rules on how to judge tactical

movement and combat, injury and recovery, creation and

use of attributes and skills, and use of equipment. The information in these chapters is presented in the same order as

in the player book, for easy cross-reference.

STAR TREK: THE ROLE PLAYING GAME

SECOND EDITION

Concept

First Edition Game Design And Writing

Second Edition Game Design And Development

Jordan K. Weisman

Fantasimulations Associates

Guy W. McLimore, Jr.

Greg K. Poehlein

David F. Tepool

FASA Product Design Staff

Wm. John Wheeler

Jordan K. Weisman

Michael P. Bledsoe

Forest Brown

L Boss Babcock, III

Fantasimulations Associates

Copyright© 1966,1983 Paramount Pictures Corporation

All Rights Reserved

Printed in the United States of America

STAR TREK® is a trademark of Paramount Pictures Corporation

No part of this book or the contents of the basic game may be reproduced

in any form, or by any means without permission in writing from the

publisher.

STAR TREK®: The Role Playing Game is manufactured by FASA Corporation under exclusive license from Paramount Pictures Corporation, the

trademark owner.

Second Edition Writing

Wm. John Wheeler

with Fantasimulation Associates

Production

Graphics And Layout

Dana Knutson

Jordan Weisman

Typesetting

Karen Vander Mey

Proofreading

The Companions, Inc.

Cover Art:

Rowena

1

Page 3

GAME OPERATIONS MANUAL

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DESIGNING ADVENTURES ......................................................................

Encounters, Scenarios, And Campaigns .................................................

Encounters

................................................................

Encounter Types ...................................................

Adventure

Scenarios

.........................................................

Linear

Scenarios

Free-Form

The Best Of Both .................................................

Campaigns ................................................................

Steps In Adventure Scenario Design .......................:............................

Adapting Published Adventures ..............................................

..................................................

Scenarios

..............................................

Planetside Adventuring ...............................................................

Strange New Worlds .................................................................

World Log .................................................................

Designing

Class M Planets

Number

Position

Number

Planetary

Planetary

Land

Planetary

Atmospheric

General

New

Life

New

Civilizations

Designing

PRESENTING

SCENARIOS

Seeing

The

Creating Vibrant Descriptions .........................................................

Using Game Aids ....................................................................

Stretching

Mineral

............................................................................

Alien

Creature

Designing

Alien

Dominant

Alien

Attribute

Attribute

MENT

Modifiers

Tactical

Fleshing

Attribute

Scores

....................................................................

Life

And

Civilization

The

Technological

Technological

Creating

Creating

Creating

Creating

Creating

Creating

The

Sociopolitical

Social

Creating

Cultural

Creating

NPCs

......................................................................

Detailed

Officer

Detailed

Enlisted

Quick

NPC

Design

Star

Klingons

Romulans

Orions

Corn

Tholians .........................................................

......................................................................

Picture

...................................................................

Making

The

Setting

Routes

Toward

The

Five

Senses

Doing

Your

Homework

A Thrill A Minute ...........................................................

Maps

And

Movement

Tactical

Map

Area

Map

Scale

Large Area Map Scale .......................................................

Region Map Scale ..........................................................

Mapping Space .............................................................

Other

Two-Dimensional

Miniature

Game

Props

And

Play-Acting

Warning:

Condition

The

Design

..................................:..........:..................

...................................................

Of

Class M Worlds

In

System

Of

Satellites

Gravity

Size

Area

.......................................................

Rotation

Density

Climate

Content

Record

.......................................................

Creatures

Life

Attributes

Scores

Scores

Scores

For

For

Movement

Out The

For

Individual

Log

Index

The

Space

The

Physical

The

Engineering

The

Planetary

The

Life/Medical

The

Psionics

Index

..............................:......................

Science

The

Social

Attitude

The

Cultural

Design

......................................................

Man

Design

..........................................................

Fleet

Personnel

.:.......................................................

........................................................

..........................................................

............................................................

Real

More

Appeal

In

Gaming

......................................................

.......................................................

Scale

..........................................................

...............................................

Game

Aids

........................

......................................................

Red

Present

................................................

..............................................

.................................................

....................................................

................................................

..............................................

..................................................

......................................

.....................................

Form

...............................................

...................................................

For

SIR, END,

For

INT, LUC,

Alien

Feeding

And

Numbers

Aliens

.........................................

.....................................................

Index

Classifications

Science

Index

Classifications

Science

Index

..........................

.................................

.......

.......

And

DEX

...............................

And PSI

Animals

Habits

Science

Index

Classifications

Attitude

................................

.....................................

.......................................

Combat

Statistics

.........................................

.........................................

Index

Science

Science

............................

..................................

Index

...................................

Index

.................................

.....................................

Index

................................

Index

..............................

........................................

..................................

Index

...................................

................................

Index

.................................

...

....................

...........

...............................................

.....................................................

.................................................

..................................................

. .

............

Aids

..........................................

.........

...........................................

.-.'.

.........:..................

OD-ing On Technique .................................................................

JUDGING

PLAYER

CHARACTER

CREATION

Assigned

Ship,

Rank,

Choosing A Ship

Choosing

Choosing

Choosing A Race

Creating

Creating

Character Aging .....................................................................

Notes

Pre-Academy

Star

Branch

.....................................................................

Attribute

Attribute

Attribute

Creating

Endurance

On

Skills

......................................................................

Skill

Rating

Skill

Descriptions

Master

Skill

Skill

Fleet

Academy

Outside

Advanced

School

Skill

Branch

Outside

Advanced

........................................................

And

Position

.....................................................

...........................................................

Player

Character

Rank

Player

Character

Scores

............................................... . ...........

Scores

............................................................

Descriptions

Attribute

Scores

Initial

Dice

Racial

Modifiers

Bonus

Points

Statistics

Definitions

Unskilled

Semiskilled

Qualified

Professionals

...........................................................

List

............................................................

List

................................................................

Skills

.................................

Electives

...........................................................

Study

............................................................

Lists

..............................................................

School

Curriculum

Electives

...........................................................

Training

..............................................

Positions

..........

. . ...

..... ....

...

...............

.......................................................

....................................................

Roll

...................................................

..................................................

.....................................................

..........................................................

......................................................

........................................................

......................................................

........................................................

And

Experts

...........'...............................

. .

.........................

Skills

..............................................

..........................................................

Cadet Cruise Assignment .............................................................

Department

Head

School

Skill

List

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

4

4

5

5

5

5

6

6

6

6

6

6

6

7

7

7

7

8

8

8

8

9

9

10

10

10

10

11

11

12

12

12

13

12

12

13

13

13

14

14

14

14

15

15

15

5

5

6

6

6

7

7

7

7

8

8

8

8

8

8

9

9

9

9

9

0

20

20

20

20

20

20

20

JUDGING GROUND ACTION ....................................................................

Department

Advanced Training ..........................................................

Command

School

Skill

Command

Advanced

Post-Academy

Character

Experience

Determining

Determining Tour Assignments ...............................................

Determining

Skill

Advancement

Age

.......................................................................

Increasing Skill Ratings Through Play ...................................................

Using Attributes .....................................................................

Requesting Saving Rolls .....................................................

Saving Roll Targets For Specific Attributes .....................................

Skill Ratings And Automatic Success ..........................................

Requesting Skill Rolls .......................................................

Skill Roll Targets For Specific Skills ...........................................

Secret Rolls And Hidden Success .......................................................

Secret Rolls ................................................................

Hidden

Judging Tactical Movement ...........................................................

Judging Large-Scale Movement ........................................................

Judging Combat .....................................................................

Success

Estimating AP Cost For Unusual actions ........................................

Using

AP

Judging

Specific

Position Change ..........................................................

Movement ................................................................

Equipment And Weapon Use ................................................

Combat

And

Action Point Modifiers For Terrain Type ........................................

Vehicle Movement ..........................................................

Movement

To-Hit

Sequence

Determining

Determining

Calculating

Determining Successful Attacks ...............................................

Determining Damage .......................................................

Special Vulcan Attacks ......................................................

Judging Injury, Medical Aid, And Death .................................................

Taking Damage ............................................................

Inaction ...................................................................

Unconsciousness ...........................................................

Rest And Healing ...........................................................

Emergency First Aid ........................................................

Death .....................................................................

Vulcan

Judging Equipment Use ..............................................................

Pain

Personal Equipment ........................................................

21

21

22

22

22

22

22

Medical Equipment .........................................................

22

23

23

23

23

23

23

23

24

24

24

24

24

24

24

24

24

25

25

25

25

25

25

25

25

25

25

JUDGING STARSHIP COMBAT .......................................................

Sidearms ..................................................................

Shipboard Systems .........................................................

Using

The

STAR

Enemy

Your

TREK

Contact:

Imagination

Using

Skills

Simple

Gamemastering

Using

Using

Shielding

....................••••••••••

Head

School

Curriculum

Skills

.....................................

List

...............................•••........••••••.•••••••••••

School

Curriculum

Skills

Training

...........................................................

.............................................................

Number

Of

First

Tour

Assignment

Determining

Other Tour Assignments ...........................................

Special

Final

Tour

Length

..........................................................

...........................................

Tours

Served

.........................................

...................................

Officer

Efficiency

Reports

...............................

Tour

Posting

..........................................

....................................................

Randomly Determining If A Roll Is Needed ...........................

............................................................

..................................................................

Actions

....................................................

Emergency

Evasion

.............................................

Through

Space

...................................................

............................................................

Base

To-Hit

Numbers

Base

To-Hit

Modifiers

Range

Modifiers

Size

Modifiers

Position Modifiers .................................................

Concealment

Modifiers

Modifiers

Adjusted

Damage

From

Damage

From

Armor ...........................................................

Parrying

Attacks

Psionics .........................................................

Nerve Pinch ......................................................

............................................

Numbers

For

Thrown

Weapons

Or

Objects

......................................................

..................................................

....................................................

Modifiers

............................................

For

Target's

Movement

...................................

For

Attacker's

Movement

To-Hit

Number

Armed

Unarmed

..................................

...........................................

Combat

......................................

Combat

....................................

................

..................................................

Duration .........................................................

Regaining Temporary Damage ......................................

Regaining Damage While Unconscious ...............................

Regaining Wound Damage .........................................

Reduction

......................................................

Environmental Suit ................................................

Life Support Belt ..................................................

Psychotricorder ...................................................

Subcutaneous Transponder ........................................

Tricorder ........................................................

Universal Translator ...............................................

Biocomputer .....................................................

Cardiostimulator ..................................................

Diagonstic Table And Panel ........................................

Drugs ...........................................................

Warning About Sedatives And Stimulants ....................

Heartbeat Reader .................................................

Hypo ............................................................

Med Pouch ......................................................

Protoplaser ......................................................

Spray Dressing ...................................................

Agonizer .........................................................

Wide Angle Stun ..................................................

Phaser Overload ..................................................

Sensors

Shuttlecraft ......................................................

Transporters .....................................................

Turbolifts ........................................................

III:

Starship

Combat

Game

Bridge

Alert

...........................••••••••••••••••'•••'•••••

.....................................•••••••••••••••••'•'•'••••

.....................................-••••••••••••••••••••••••••

Captain

........................••••••••••••••••••••'•'''•'•••••••

Chief

Engineer

Science

Officer

Helmsman

.............

Navigator

.............-••••••••••••••••••••••••""•'•"•••••••••

Communications

Medical

Officer

Systems

To-Hit

...........••••••••••••••••••••••••••"•"••••••••••••••...

Damage

Location

.............,•••••••••••••'•'""'

......................

.................••••••••••••••••••'•''''''''•••••••

.............•••••••••••••••••••"'''''''''•'••••••

.......••••••••••••••••'•••••••••••••••••

Officer

.........•••••••••••••••••••••••••••••-....

............••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••...

.........••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••......

...........••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••........

° '' °

'"'""

° " °

"""•••••••...

25

25

26

26

26

26

26

26

26

26

26

26

26

26

26

26

26

27

27

27

27

28

28

28

28

28

32

32

32

32

32

32

32

32

32

33

33

33

34

34

34

34

34

34

34

35

35

35

35

35

35

35

35

35

36

36

36

36

36

36

36

36

37

37

37

37

37

3

3

3

3

3

3

38

38

38

38

38

38

38

38

38

38

38

38

38

38

38

39

39

39

39

39

39

39

39

39

39

39

39

40

40

40

41

41

41

41

42

42

42

42

42

42

42

42

42

42

42

42

Page 4

DESIGNING ADVENTURES

ENCAOUNTERS, SCENARIOS

AND CAMPAIGNS

BY WM. JOHN WHEELER

The fun of the game comes from its interesting adventures. These adventures may be short, lasting only one game

session, or they may be much longer, sometimes lasting

many months. An adventure can be compared to a television

show. Some adventures, like one-shot TV shows or movies,

are played with characters created just for the adventure;

after the adventure is done, the characters never are used

again. Other adventures, like the episodes in a television

series, are played with the same characters; each new adventure builds on the previous ones, and the characters develop

personalities and histories.

ENCOUNTERS

The basis of all adventures are the encounters that the

player characters have. An encounter occurs wherever the

player characters interact with their environment.

These encounters may be between the player characters

and the physical world at long range, such as when the bridge

crew attempts to gather information about a new Class M

world from a standard orbit, or at close hand, such as when

a landing party beams down onto the planet's surface for

the first time. These encounters may be between the player

characters and new life forms, such as when the landing

party observes, inspects, and interacts with the plant and

animal life on the planet. These encounters may be between

the player characters and new civilizations, such as when

the landing party discovers that the plants are intelligent,

resentful of intrusion, and deadly! The encounters can be

between player characters and non-player characters, such

as the meeting between the Captain and the Council Of Ani-

mal Control, the plants who determine whether or not animal

life is harmless or a pest needing extermination.

Encounter Types

There are two types of encounters in most adventures,

planned encounters designed as part of the adventure and

random encounters that occur because of pure chance. Many

random encounters occur as the result of a random die roll.

How often an encounter occurs and the type of encounter

will

depend

scale being used. It is not reasonable to expect to encounter

on the

area

where

the

characters

are and the

all kinds of beasties in the middle of a fully-operational Star

Fleet outpost even in a dozen turns at the area scale, but

there may be a random encounter every turn in the region

scale, for example. Encounter charts and directions for using

them usually will be given in the individual scenarios and

adventures. These frequently list the possible kinds of en-

counters and give the chance of a random encounter occur-

ring.

ADVENTURE SCENARIOS

An adventure scenario is a story, linking together en-

counters. Some scenarios will have a well-established plot,

moving predictably from one encounter to another. Others

will have general story lines, but how the story progresses

from one encounter to the next is completely open and unpredictable. Scenarios with well-established, predictable

plots are linear in nature, with all of the encounters strung

out in a line, as though they were on a path. Scenarios with

open and unpredictable story lines are free-form in nature,

with the encounters like apples on a tree, any one of which

may be picked next.

Linear Scenarios

Linear scenarios have some strong advantages and

some strong disadvantages. Among their advantages, they

provide a real sense of story, with a beginning, a climax, and

an aftermath. Some players will be quick to sense the plot,

and they will be able to use this knowledge to their advantage. Such scenarios can build suspense or tension, because

each encounter can build on the ones before. They are easy

to design, because the encounters can be begun in certain,

predictable ways, and ended in the same ways. They give

few surprises to the prepared gamemaster, and they require

little preparation, because the environment and the NPCs

that the player characters will meet is known before the

game.

On the other hand, linear scenarios give the players the

least freedom. Because they are structured to play out a

certain way, frequently the players' creative solutions do not

work well. Players feel pressured into behaving in certain

ways, and, unless the gamemaster is very careful, they can

feel that nothing they do makes any difference.

Free-Form Scenarios

Open, unpredictable scenarios also have some strong

advantages and disadvantages. Among their advantages,

they allow the players complete freedom, moving in

whichever direction suits them at the moment. At their best,

they depend completely on what the player characters do,

the actions in one encounter possibly having an effect on all

of the other encounters, like ripples from a stone thrown into

a pond. They make the players feel as though their actions

completely control the game.

On the other hand, free-form scenarios are very demanding on the gamemaster. The near-legendary ability of players

to surprise the gamemaster is given free rein here, and unprepared or inflexible gamemasters will become lost quickly.

Unless the gamemaster is very careful, these scenarios can

make the players feel lost, wondering where to go next and

what to do when they get there. They require frequent

signposts, guiding the players or alerting them to possibilities for action. They require extensive preparation, not

only in terms of design, but also just before play; the

gamemaster must know a great deal about his environment

and the NPCs that people it.

The Best Of Both

The best published scenarios combine the two types,

using some linear encounters and some free-form encounters. Linear encounters are used to introduce the scenario,

drawing the players and their characters into the action, giving them a reason to enter the scenario environment and

meet the scenario NPCs. After the 'hook/ as the introductory

encounter is sometimes called, the linear encounters lead

the player characters into a situation which gives them free

choice about where they will proceed. The actions in each

of the free-form encounters affect the players in the short

term. In the long term, another set of linear encounters lead

the players into yet another area of free choice, perhaps the

climax of the scenario. Linear encounters often are used to

wrap up the scenario, bringing it to a satisfactory conclusion.

Using encounters of both types is like building a structure

with tinker toys, with the sticks being linear encounters and

3

Page 5

the knobs being the free-form encounters. The linear encounters give some structure to the free-form encounters. The

combination allows the scenario to have a well-defined story

line, not as well-defined as purely linear scenarios, but much

more defined than those that are purely free-form. The com-

bination also allows the players freedom to choose their

action, not as much as in purely free-form scenarios, but far

more than in those that are purely linear.

In general, use linear encounters to introduce the

scenario and to set the story line. This would be like sending

orders to the player characters to pick up a passenger from

a certain space station, then having them meet the Orion

NPC and his lovely slave girl, and then have the ship attacked

by Orion freebooters who want the slave girl back.

Use free-form encounters to develop the scenario. This

would be like allowing the crew to flee from the pirates, to

defend themselves, to turn and attack the pirates, orto pursue

the pirates; alternate choices would be to declare a tempo-

rary truce to discover the problem, or even to turn over the

slave girl and her master at once. How the scenario progres-

ses depends on the choices the players make.

Then use a new set of linear encounters to move the

story along. This would be like having the ship receive an

incomplete message of distress. No matter what choice they

made in the earlier confrontation with the pirates, they would

receive the message. Chances are great that the ship will

respond, though there is still the chance that they will not.

If it is important to the story for the ship to respond, the

message can be repeated, the ship in distress could be in

the path of the player character's ship, and so on. In well-con-

structed linear encounters, the players may feel like they

have a choice, and that they really have none is well-hidden.

Use more free-form encounters to further develop the

scenario. This would be like having the distress call come

from an Orion privateer vessel, possibly even the same one.

The players have a new set of choices to make, and how the

scenario will progress depends on what they do.

Finally, have another set of linear encounters lead into

the climax of the scenario, the high-point of the story.

Most often, the climax is not the end of the story, but

some point near the end. The climax is best as a free-form

encounter; therefore, how the story actually ends depends

on what the players choose to do.

The aftermath of the climax, the story's wrap-up ("And

they lived happily ever after/'), easily can be a set of linear

encounters that lead into the 'hook' for the next scenario.

CAMPAIGNS

A campaign is a series of adventure scenarios, held together in one of three ways. One way is that the player characters all are the same, even though the scenarios do not have

much to do with one another; this is the way a campaign

would be run if it were like the STAR TREKJV show. Another

way is that the scenarios all have to do with the same topic,

perhaps approaching it from different angles, possibly with

different characters; this is the way a campaign would be

run that dealt with the beginning of the Second Klingon War,

for example, where no one group of characters could possi-

bly be involved in every aspect. A third way, possibly the

most exciting, is to combine the two; this would be a cam-

paign in which the same characters follow the same plot

from adventure to adventure, solving puzzles along the way

and discovering more and more information about the plot

as the adventure scenarios progress.

Campaigns of the first type are the easiest to design and

run. They require only the dedication of the gamemaster and

the players to design player characters that will be interesting

to play week after week. All the adventures must come to a

climax brought about by the player characters' actions. As

characters die, they are replaced. The important thing is that

the characters' ship survives from game session to game

session, for this is what holds the player characters together.

The adventures may be designed by the gamemaster, even

on the spot! They also may be purchased, for most commer-

cial adventures are written for campaigns of this type.

Campaigns of the second type are not quite as easy to

design. They require a master plot, one that allows for many

adventures. The only restriction is that all scenarios deal with

the master plot in some way, because in campaigns of this

type, the master plot holds things together. The job is not

as difficult as it might seem, because the plot can be vast in

scope, and it will not come to a climax in one adventure,

and it need not come to a climax at all. Several adventures

may be run with the same starship and crew, but the scope

of the master plot allows the ship to be destroyed or lost

and another created to replace it. As the campaign progresses, the master plot unfolds, giving all the adventures added

realism and depth. It will be necessary for the gamemaster

to spend some time designing the master plot, which really

is his campaign universe. He will have to create the major

controversies and conflicts, the history and background for

them, and the areas in which the player characters are likely

to make a difference. Although some of the adventures for

this campaign type can be purchased, they will have to be

modified to tie them into the master plot.

Campaigns of the third type are the most difficult to

design, for they require the gamemaster to design one or

more master plots that can involve the small group of player

characters and can be brought to a climax by the characters'

actions. Each adventure builds on the one before it, adding

details to the master plot(s) as the players (and their characters) discover more about the campaign universe. In this type

of campaign, it is possible to develop NPC opponents that

the player characters meet again and again, much like the

archvillains found in superhero comic books. Again, the im-

portant thing is survival, for the campaign centers around

the player characters. As characters die, others are promoted

or transferred in to take their place. This campaign is the

most work for the gamemaster (but possibly the most rewarding), for nearly every adventure must be tailor-made.

Most will need to be designed by the gamemaster, for few

companies produce adventures oriented to this type of cam-

paign.

STEPS IN ADVENTURE

SCENARIO DESIGN

BY WM. JOHN WHEELER

In designing an adventure scenario, the gamemaster's

first job is to decide on a plot for the scenario, the story that

the game will play out. Ideas for these stories can come from

almost anywhere: television shows or movies, comic books,

novels, even real history. Some of the best stories come from

answering the question, "I wonder what would happen if..."

Second, the gamemaster must design an environment

that fits his story. If this means creating a "strange new

world... new life and new civilizations," then he must do this

job. Systems are given later in this chapter that will help do

this. Sometimes, this job is done first, for many times creation

of a new life form or civilization will suggest a story.

Third, the gamemaster must define for himself the goals

for his players. He must decide on what he expects the player

characters to accomplish, and what steps they can take to

achieve their goal. Not only this, but he must make the same

decisions for the NPC opponents and allies. This usually will

include the background story that will be told to the players.

4

Page 6

The background must be complete enough that it is clear to

the players why they are where they are and what they are

expected to accomplish.

Fourth, the gamemaster must decide upon the first en-

counter, the hook leading into the scenario. This 'hook'

should give the players a strong reason to enter the scenario,

to become involved. The 'hook' can play on the players' good

nature, their sense of fairness or justice, their pride and ego,

their desire for fame or fortune, or even their need for revenge. Whatever the reason, it must be strong, with a sense

of urgency, giving the players the feeling that they must

become involved NOW, and waiting until later will not be

desirable. If all else fails, the old standby, a message from

Star Fleet Headquarters, can point the players in the right

direction.

After this, the process depends on the story chosen. It

will be necessary to design each of the encounters that the

players WILL have. These are all of the linear encounters and

the climax. Then, it is a good idea to design the encounters

that the players are LIKELY to have and at least sketch out

those that they MAY have. The setting for each encounter

must be designed, at least in general; furthermore, notes

need to be made about the NPCs, the other life forms, and

the objects, so that when they are encountered they can be

described for players.

In preparing these encounters, rough notes, maps, and

sketches usually are enough to meet most needs. It is helpful

to draw maps of key areas, and to make notes on the map

itself, perhaps using a color-coded system. Sometimes, more

detail should be provided giving the exact information avail-

able from critical sensors or tricorder scans, of critical encounter areas, or of important NPCs met. As a gamemaster

gains experience, he will find it easier to know just when

rough notes are not enough and detail is needed.

A very important fact to remember concerns the kinds

of encounters that make the game interesting and fun. Variety

is the key word. Some encounters should be friendly, some

should be hostile, and some should be neither. Few should

result in combat. A phaser is a potent weapon, and Star Fleet

personnel do not use them indiscriminately. Combat, on the

ground or in space, is an important part of the feel of STAR

TREK, but if the game degenerates into merely killing Kling-

ons, then it will lose much of its enjoyment.

ADAPTING PUBLISHED ADVENTURES

Published scenarios and adventures are a good way to

get started or to play with a minimum of design work. Many

of these are well written, providing a good mix of encounter

types and an interesting and enjoyable story line. Even the

best of these, however, requires some design effort before

it can be used in any particular campaign or with any particu-

lar group.

Only you, as the gamemaster, are familiar with your

campaign and your players. Only you can tell when an encounter from the scenario is likely to be interesting to your

players or when it will bore them to tears. Only you can tell

how it must be altered to fit your players' characters, their

ship, or the situation in which they find themselves. There-

fore, YOU must be the oneto alterthe design tofityour needs.

Don't worry about this job. Most of the time, the changes

will be obvious after you have read the adventure the first

time. Make notes about the changes in general, and then

flesh out the notes as you go along. Remember this: the

more you can make the published adventure seem to be a

natural part of your game, the betteryour players will like it.

It is a rare person who can be successful with a published

adventure after only one reading, and few can remember

enough of the adventure to use it after only two. One of the

hidden advantages of designing your own scenarios is that

you know them thoroughly!

PLANETSIDE ADVENTURING

Much of the action and adventure in STAR TREK takes

place on Class M planets, such as those investigated by the

USS Enterprise on it's five-year mission. Gamemasters will

want to create a steady stream of these strange new worlds

to explore, as well as new life and new civilizations to popu-

late them. Space, and its variety, is infinite; STAR TREK: The

Role-Playing Game should be a celebration of this variety.

These new worlds, new life-forms, and new civilizations

largely will be created by the gamemaster. Like the writers

who shaped the STAR TREK universe in the first place, he

will create planets, animals, and sentient races to suit his

campaign and to delight the players involved.

The first step is to determine the physical parameters of

the new world that is to be explored. The specifics about the

planet's position in the system, its gravity and size, its cli-

mate, and its mineral wealth all may be determined using

the Class M planet design system.

Next, the gamemaster must determine what type of life

exists. Class M planets are all capable of supporting life, and

the least hospitable Class M world will bear at least microorganisms. Gamemasters are encouraged to come up with

imaginative, sensible and playable life forms on their own.

The alien creature design system may be used to help a

gamemaster decide what the highest form of life on a new

planet is like, and if it is intelligent enough to qualify as a

thinking (sentient) being, and not an animal.

Finally, if the dominant creature is intelligent, it is necessary to determine the specifics of its civilization.

Even the most creative gamemaster needs a push in the

right direction and some guidance occasionally, and the capacity for players to surprise even the most prepared

gamemaster is legendary. For these times, simple systems

have been provided so that gamemasters can generate

quickly some of the important data about a yet-to-beexplored Class M planet and the life forms that might be

found there. The gamemaster can then take this basic data

and expand on it to flesh out the adventure.

STRANGE NEW WORLDS

Only Class M planets are covered by this system, be-

cause those are the planets that Star Fleet's exploration ships

are assigned to explore. Class M planets have a silicate and

water surface like that of Earth, an oxidizing atmosphere like

air, and geologic activity. They are planets capable of

sustaining most Federation species (carbonbased oxygen-

breathers) without major life-support equipment. Occasionally, ships call at other than Class M worlds, and some

successful colonies have even been established on these

worlds; but such worlds are selected for their strategic

location. Class M planets come in a wide variety, and they

all are not as hospital as Terra (Earth).

This system uses dice rolls to generate the planetary

data, but these dice rolls should be used only to spark a

gamemaster's imagination or to give a push in one direction

or another. The planets generated using this system, which

is purely random, may not conform to accepted scientific

principles. Gamemasters should feel free to pick and choose

data for planets, keeping in mind that the system provides

a guideline to the relative chances for each planetary attribute

and does not guarantee overall acceptability.

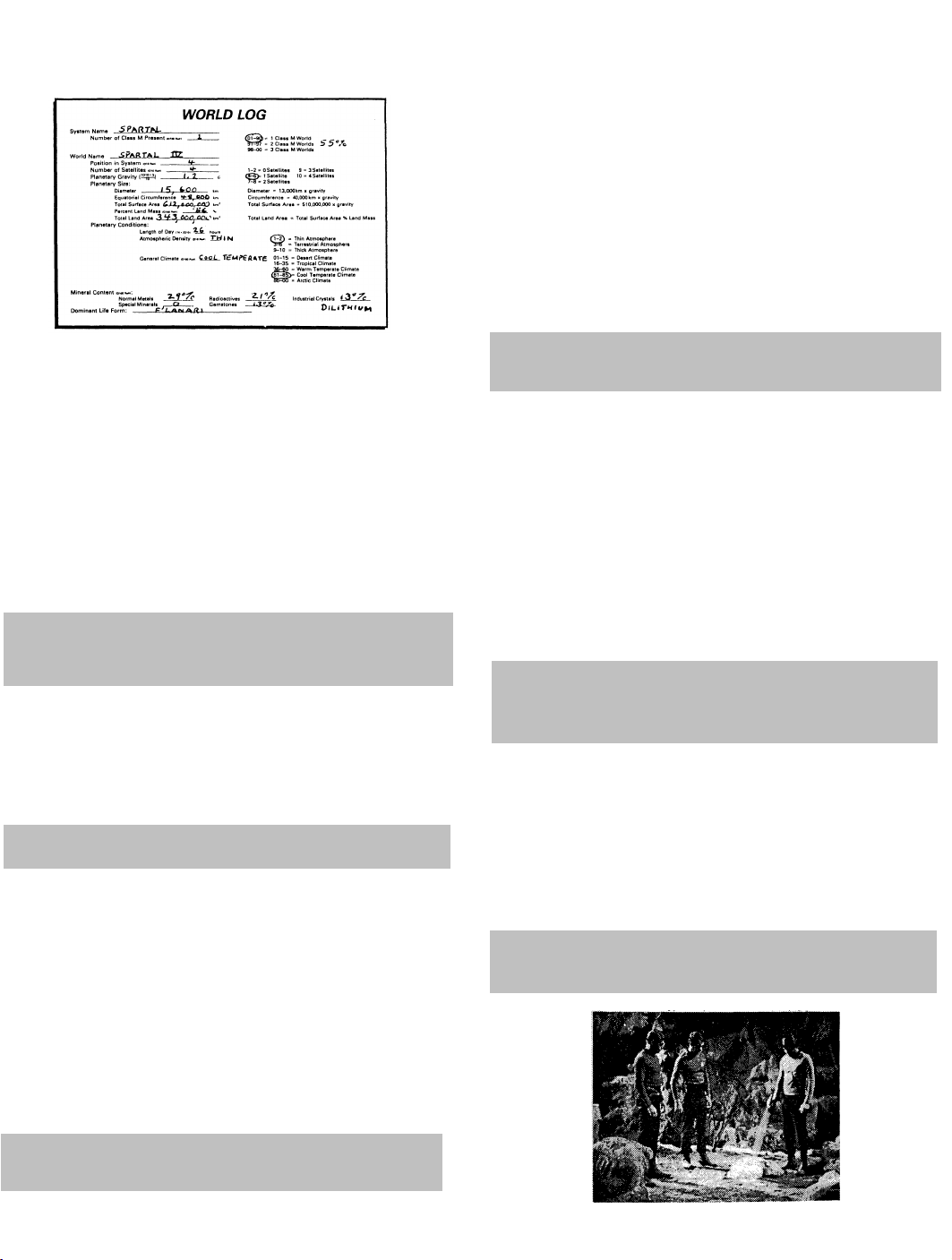

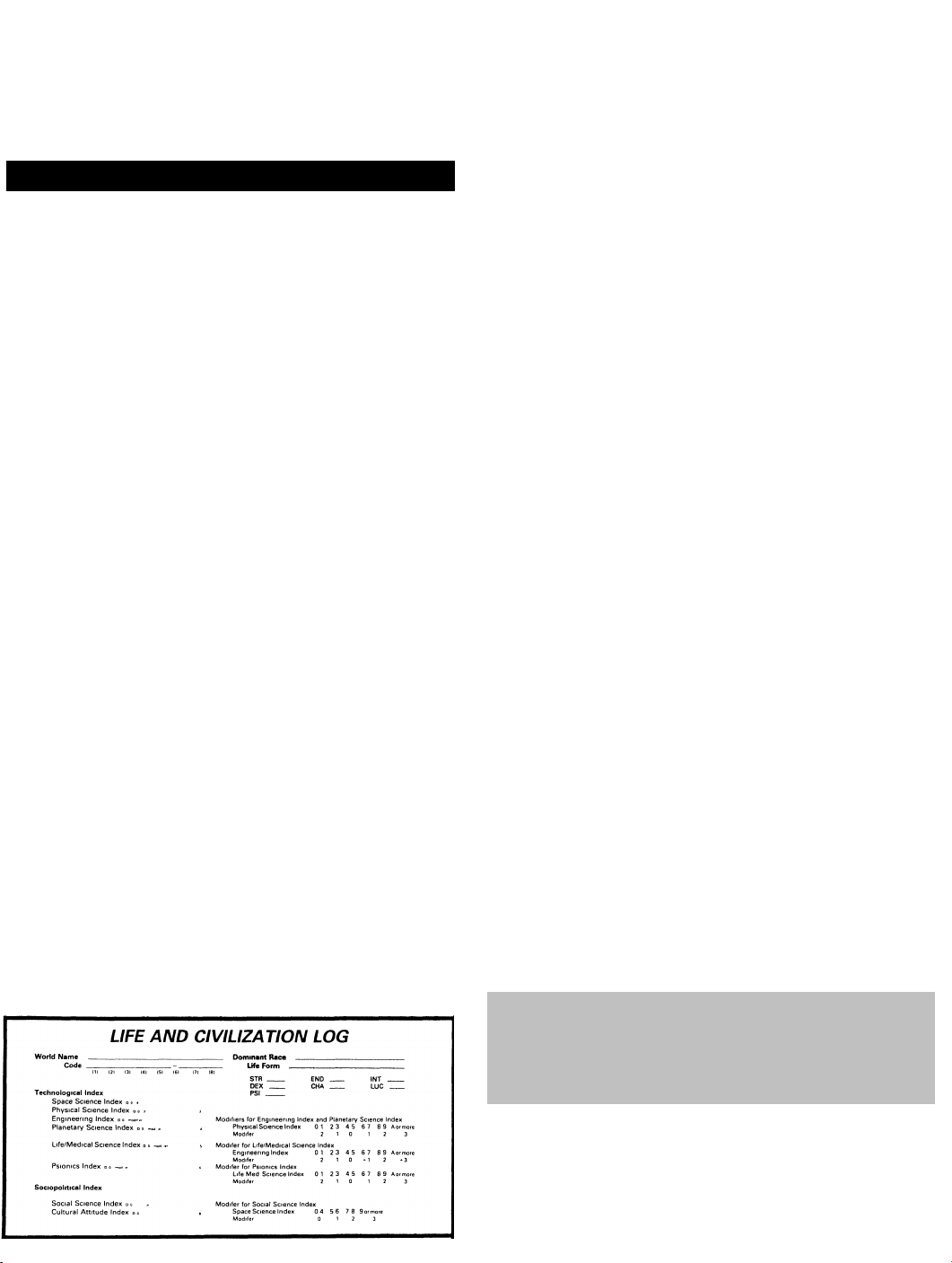

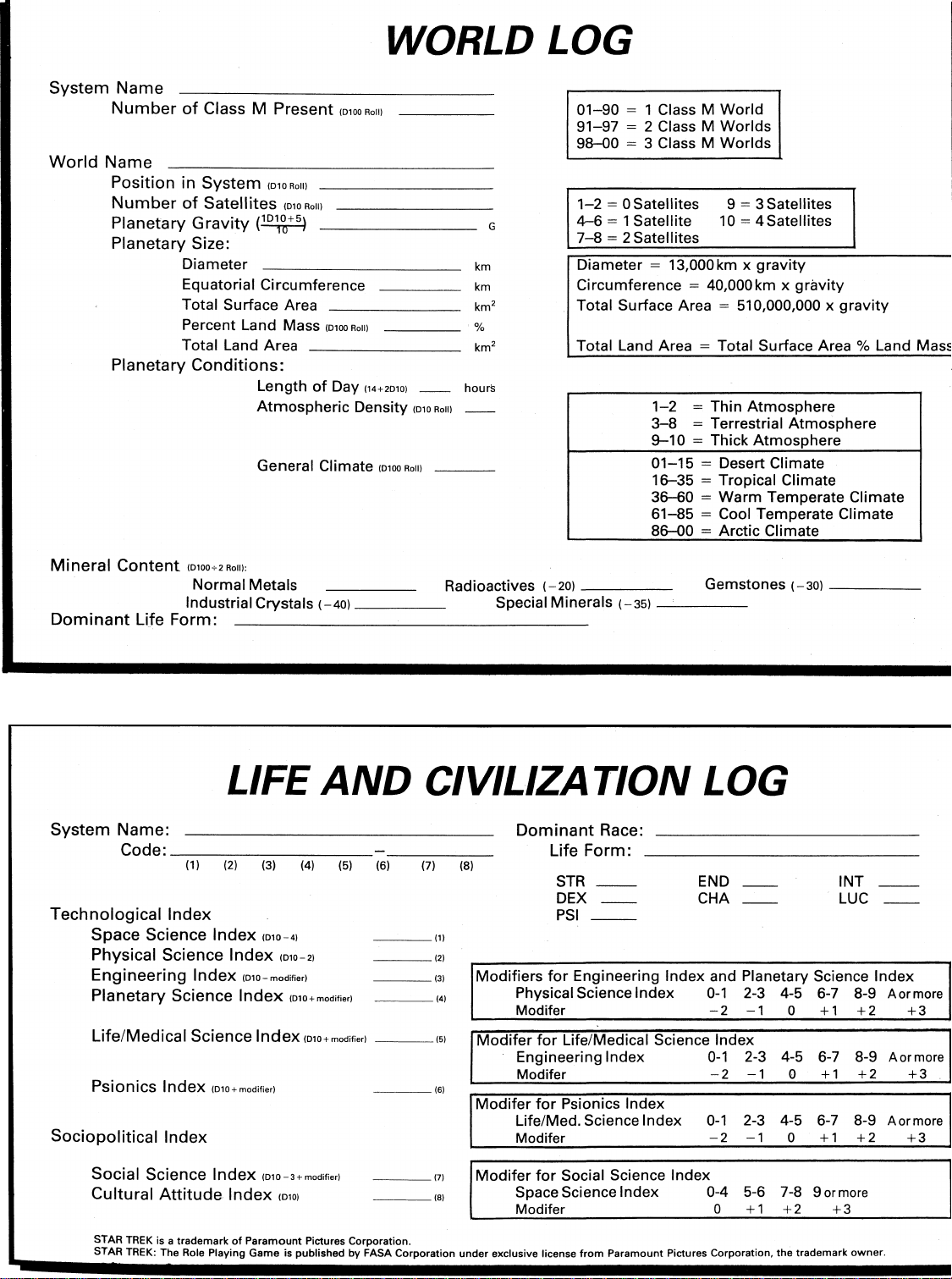

WORLD LOG

The World Log shown in the illustration should be used

to record the information about each world as it is created.

Permission is granted for players and gamemasters to photo-

copy this form for their personal use. The world design sys-

tem follows this log, with each step adding new information

5

Page 7

to it. An example of this log has been provided, with all of

the information filled in for the world Spartal IV. After each

step in the process is explained in the text, the appropriate

information will be generated for this example; this informa-

tion is shown shaded in the text.

DESIGNING CLASS M PLANETS

Follow this procedure step-by-step, filling out the World

Log as each piece of information is generated.'

Number Of Class M Worlds Present

Roll percentile dice and consult the table below to determine if there are 1, 2, or 3 Class M planets in the system.

Four or more Class M worlds in one system would be extremely rare, but possible if the gamemaster chooses.

NUMBER OF CLASS M PLANETS IN SYSTEM

Dice

Roll

01-90

91-97

98-00

Number Of

Worlds

1

2

3

The percentile-dice roll for the number of worlds in the

Spartal star system is 55. This indicates that there is only 1

Class M planet in the Spartal system.

Position In System

Roll 1D10 to determine the number of the planet in the

system. It is usual to use Roman numerals to number the

planets outward from the star. If the system has more than

one Class M planet, roll the die the appropriate number of

times, re-rolling ties.

POSITION IN SYSTEM =1010

The 1D10 roll was 4, and so the planet will be Spartal

IV, the fourth planet in the system.

Number Of Satellites

Roll 1D10 to determine the number of natural satellites,

from 1 to 4. Roll percentile dice to see if the satellite is a

Class M itself. If the roll is 01, then this is the case; generate

its data just like a separate planet.

NUMBER

Die

Roll

1-3

4-6

7-8

9

10

OF SATELLITES

Number Of

Satellites

0

1

2

3

4

Planetary Gravity

Roll 1D10 to determine planetary gravity for the Class

M world. The gravity is determined by adding 5 to the die

roll and dividing the total by 10, without rounding the result.

This gives a resultant gravity of anywhere from 0.6 G to 1.5

G. (1G = Earth gravity.) Planets with greater or lesser gravity

than this do not qualify as Class M worlds.

When characters land on high-gravity worlds, those who

are not used to the added gravity should make fatigue END

rolls more often than normal because of the extra stress.

Skill Rolls likely would be required for delicate work by such

characters if they failed a Saving Roll against the average of

DEX and STR. When characters land on low-gravity worlds,

most

will

need

to

make

DEX

normal, but they may not become fatigued as quickly. In

Saving

either case, the longer a character is on the world, the less

Rolls

more

often

than

the gravity difference will affect him.

PLANETARY GRAVITY = (5+1D10) / 10

The gravity roll for Sparta! IV was 7, and so the gravity

is 1.2 G. (7 +

5=12;

12 / 10=

1.2).

Planetary Size

Planetary size is not often a factor in play, and so no

system for approximating size is provided. Assume that the

planet has a density identical to that of Earth, and so its

gravity would indicate its size relative to that of Earth. To do

this, multiply Earth's planetary size, given below, by the grav-

ity factor just rolled to get the size of the new Class M world.

EARTH PLANETARY SIZE

(approximate)

Diameter: 13,000 km (8,000 miles)

Equatorial Circumference: 40,000 km (25,000 miles)

Total Surface Area: 510,000,000 sq. km

1196,940,000 sq. miles)

The diameter of Spartal IV is 15,600 km

(13,000 x 1.2= 15,600), the circumference at the equator is

48,000 km (40,000 x 1.2 = 48,000), and the total surface area

i$ 612,000,000 sq. km (510,000,000 x 1.2 = 612,000,000).

Land Area

To determine the percent of the surface which is land,

as opposed to water, roll percentile dice. The roll indicates

the percent of surface land. A result of 01 means there is 1%

land surface, probably in the form of small islands. A result

of 00 means 100% land, probably as desert with almost no

free-standing water. To find the amount of land in square

kilometers, multiply the total surface area by the dice roll

and divide by 100.

PERCENT LAND AREA = 0100

The percentile dice roll gives 56. Thus, Spartal IV has

56% land and 44% water. The land area is about 343,000,000

sq. km (612,000,000 x56 / 100 = 343,000,000).

The 1D10 roll for the number of satellites is 4, which tells

us that Spartal IV has one natural satellite. A roll of 74 on

percentile dice indicates that the moon is uninhabitable.

6

Page 8

Planetary Rotation

Planetary rotation time, in hours, is determined by rolling

2D10. Add the rolls together and add 14 to the sum. This

generates a time between 16 and 35 hours as the length of

one local day.

This tells nothing about the number of daylight hours,

merely the approximate number of hours between midnight

(or any other time) one day and the same time on the following day. To find out how many daylight hours, assume the

world is like earth. About half of the hours will be spent in

daylight, and half spent in night. Use the current season on

Earth as the season on the world; in winter, the night will

be longer and in summer it will be shorter than half the total

day. The length of the local day (or the number of hours of

daylight) could be important in some planetary scenarios.

LENGTH OF DAY - 14 + 2D10 HOURS

The 2D10 roll for Sparta I IV's planetary rotation period

is 7 and 5, for a total of 12. Adding 14, brings the total to 26

hours, the length of a local 'day' on Spartal IV.

Atmospheric Density

Both thin and thick atmospheres are breathable, but they

may cause fatigue over longer periods of time. If no special

measures are taken, such as Tri-Ox injections for thin atmospheres or breathing masks for thick atmospheres, all characters except Vulcans and Tellarites must make END Saving

Rolls every two hours. These Saving Rolls, and any others

necessary (such as for fatigue) will be made with a modifier

of -20 to the MAX OP END. Vulcans and Tellarites are used to

thin atmospheres and require no extra or modified saving

throws for thin or normal atmospheres.

To determine the atmospheric density of the planet,

whether it is normal (like that of Earth), thick, or thin, roll

1D10 and consult the following table.

ATMOSPHERIC DENSITY

Die

Roll

1-2

3-8

9-10

Atmospheric

Density

Thin

Terrestrial

Thick

The die roll for atmospheric density is a 10, which means

that Spartal IV has a thick atmosphere.

General Climate

To determine the planet's general climate, whether it is

temperate, tropical, desert, or arctic, roll percentile dice and

consult the following table. The climate is only a general

description. An arctic planet will have cool temperate zones,

and a tropical planet may have warm temperate areas.

Though Earth falls in the cool temperate range, it has climates

in all the classes on the table.

The gamemaster should not be bound to the die rolls in

this section, and random rolls here must be tempered with

common sense. For example, a planet with less than 5% land

area would be unlikely to qualify as a desert planet. The

gamemaster is strongly urged to use this table only as a

guideline that indicates a general direction. Feel free to substitute imagination for dice rolls at any time!

GENERAL CLIMATE

Die Roll

01-15

16-35

36-60

61-85

86-00

Climate

Desert

Tropical

Warm Temperate

Cool Temperate

Arctic

A percentile roll of 62 means that Spartal IV has a cool

temperate climate.

Mineral Content

The following optional system is used to determine the

mineral content of the planet. To eliminate the trouble of

mapping each individual vein of ore, percentile dice are used

to determine the percentage chance of finding a certain min-

eral in a given area.

Mineral content is divided into five categories: normal

metals (iron, copper, aluminum, etc.), special minerals

(pergium, topaline, ryetalyn and other STAR TREK inven-

tions), radioactives (uranium, plutonium, etc.), gemstones

(diamonds, rubies, flame gems, etc.), and industrial crystals

(dilithium, special silicates, etc.). For each category (or each

mineral, if the gamemaster needs that detail) roll percentile

dice, divide by two, round up, and subtract the modifier, if

any. This will give the likelihood of finding it in any given

area on the planet.

The modifiers show that some minerals are quite rare

(industrial crystals, special minerals), and some less so. If,

after subtracting the modifier, the number is zero or less, the

planet will not have the mineral type in question. Only one

type of special mineral or industrial crystal will be found on

any planet. The modifiers may be changed at the gamemaster's discretion, particularly if he wants to 'load' a particular

area with one or more minerals.

The general percentages generated in this way can be

determined by a ship's sensor scan from orbit. Such a survey

takes about 5 hours times the planetary gravity factor, which

modifies the roll to account for a small or large planetary

surface area. Round off the result to the nearest hour.

CHANCE FOR MINERALS = D100-2 FOR EACH TYPE

Mineral Type

Normal Metals

Radioactives

Gemstones

Industrial Crystals

Special Minerals

Modifier

0

-20

-30

-35

-40

The percentile dice roll for normal metals was 57; thui

Spartal IV has 29% chance for normal metals. The roll fo>

radioactives was 82, and the chance for radioactives is 21°/<

(82 -T- 2 = 41; 41 - 20 = 21). The roll for gemstones was 86

and the chance for gemstones is 13% (86 -r 2 = 43,

43 - 30= 13). The roll for industrial crystals is 95, and thi

chance for industrial crystals (dilithium in this case) is 13°A

(95 -s- 2 = 47.5, rounded up to 48; 48 - 35 = 13). The roll fo>

special minerals was 03%, and so there are none on tht

planet (3-5-2=1.5, rounded up to 2; 2 - 40 = - 38, or 0). Thh

scan takes 6 hours (5x 1.2 = 6) after the ship begins standarc

orbit.

Once the general percentage chance is determined, <

landing

party

with a professional-level

geologist

of at least 40 in Geology) may make closer scans with «

sciences tricorder. The gamemaster then makes a secret per

centile'dice roll against the generated percentage to see i

the area being surveyed actually contains the desired miner

als. If the roll is equal to or less than the base chance fo

that mineral, a deposit is present in the survey area. It i

possible, but not likely, that more than one mineral type wi

be abundant in a specific survey area.

It takes 10 hours for a landing party to check a squar

kilometer for mineral deposits. More than one party can b

used, proportionally reducing the time. (Two parties can d<

it in 5 hours, three in 31/3 hours and so forth.) Each part

must have at least one geologist with a sciences tricordei

7

(Skill

Ratine

Page 9

Also, the parties must separate to be effective, which means

the groups likely will be too far away to help one another if

there is trouble.

At the end of the scan in an area, the geologist gains

the information he seeks. If no professional-level geologist

is present, the gamemaster must make a determination if

the characters in the landing party have the skill to notice

the mineral deposit. The gamemaster must also determine

how accessible the material will be.

NEW LIFE

The system presented here will help determine new life-

forms on the world being designed, whether or not they are

intelligent enough to be called thinking beings, what they

look like, and what their abilities are. Mammals predominate

to reflect the STAR TREK universe as seen in the TV series;

most dominant species on worlds visited by the USS Enter-

prise were mammals. As information is developed, it should

be recorded in two places: on the Alien Creature Record and

on the Life And Civilization Log, described below.

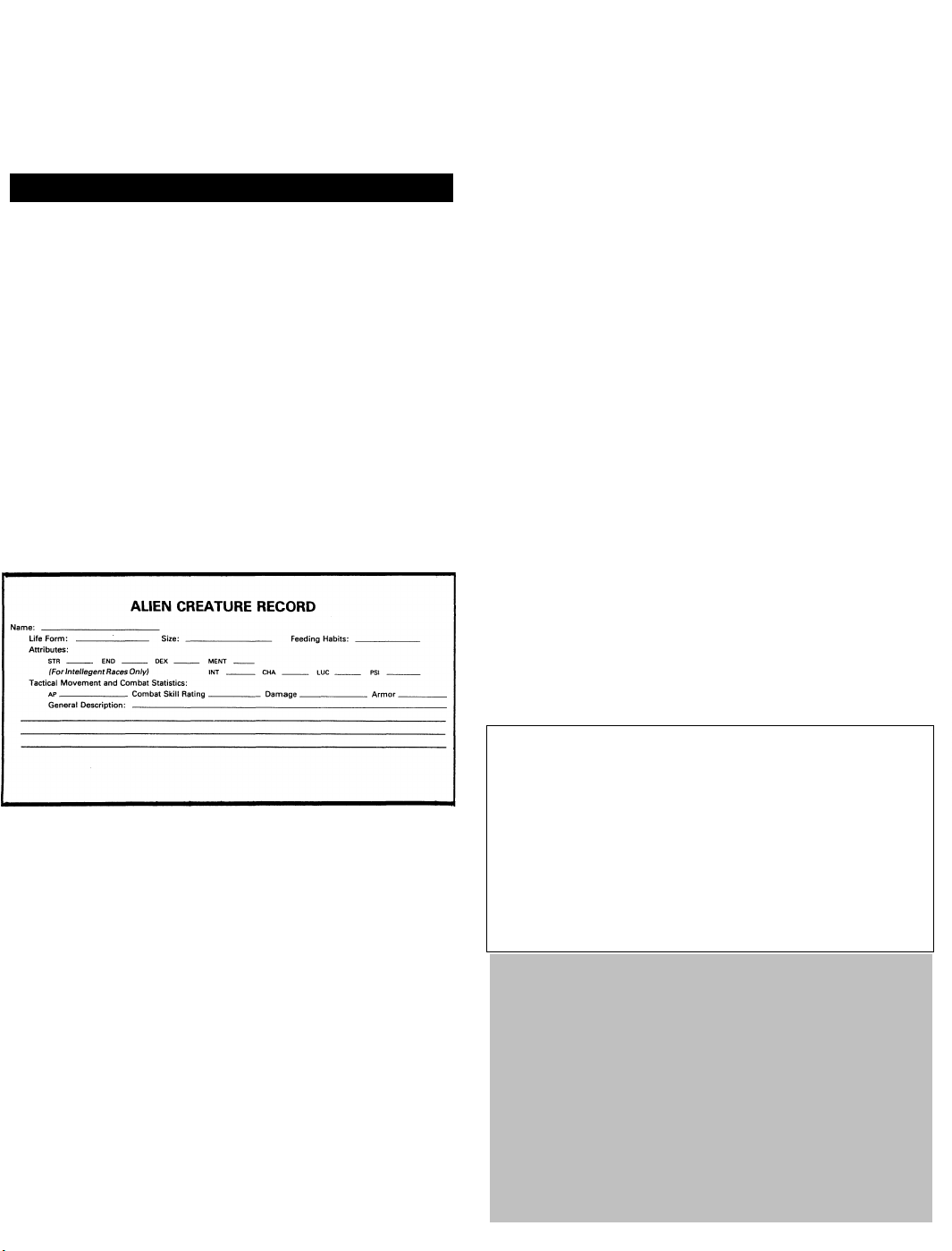

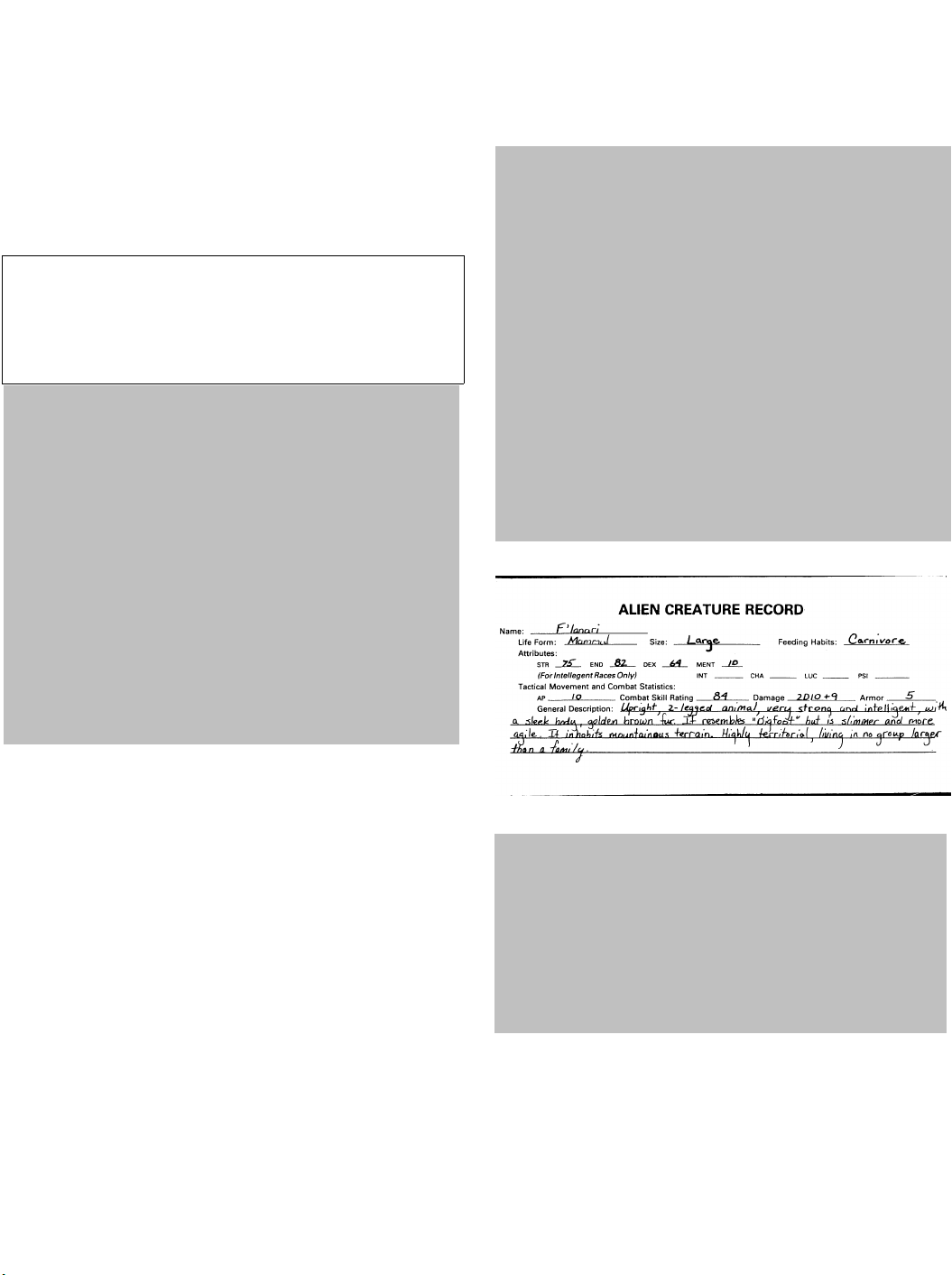

ALIEN CREATURE RECORD

The Alien Creature Record provided at the end of this

book should be used to record the information generated

when creating alien creatures, whether they are animals or

thinking beings. The alien creature design system follows

the record form, with each step adding new information to

it. This record is shown in the illustration. Permission is

granted for players and gamemasters to photocopy this form

for reasonable personal use.

Dominant Life-Form

The major life forms of a new planet may be designed

using the procedure below, but only one is likely to dominate

the planet, just as Man dominates Earth. It will be the most

highly developed life form on the world. Representatives of

all groups will be in evidence on the planet as well, but none

of the groups above the dominant group will have much

importance. Thus, if the dominant form on a planet is an

amphibian, it is certain that there will be fish, insects and

mollusks, plants, and microorganisms on the planet; but any

reptiles, birds, or mammals native to that world are likely to

be relatively unimportant members of the food web.

The table below gives the chances for each group of

being the dominant life form; the term 'Special' includes

creatures made of pure energy, gas, crystalline material, or

anything else the gamemaster chooses.

The table also indicates if the dominant life form is a

thinking (sentient) creature, another alien race. If the domin-

ant life form is determined to be intelligent, it is possible

(though not likely, competition between species being what

it is) for another form on the planet to be intelligent as well,

just as dolphins may be intelligent on Earth. If the dominant

life form is merely an animal, likely with a well-developed

animal intelligence, there is little chance that another, more

intelligent (or thinking) race also inhabits the world.

To determine the type of life form that dominates the

world, roll percentile dice and consult the table below. The

'Percent Sentient' column indicates the chance for the dominant life form to be a thinking creature. After the life form type

has been determined, roll percentile dice again and compare

the roll to the table to see if the life form is an intelligent

race. If the roll is less than or equal to the Percent Sentient,

then the dominant life form is a race of thinking beings.

If the dominant species is determined to be intelligent,

make both rolls again to determine if the world has a second

intelligent form. First roll to find the life form type, and then

roll again to see if it is intelligent. If the second Percent Sen-

tient roll indicates intelligence, reroll. If the new Percent

Sentient roll indicates intelligence as well, there are two in-

telligent races on the world.

An example of this form has been provided, with all of

the information filled in for the F'lanari, the dominant form

for Spartal IV. After each step in the process is explained in

the text, the appropriate information will be generated for

this example. This information is shown shaded in the text

that follows.

DESIGNING ALIEN CREATURES

Follow this procedure step-by-step, filling out the Alien

Creature Record as each piece of information is generated.

This system does not use 'one from column A, one from

column B.' The table will develop a basic idea of what the

creature is like and its attributes. The rest is up to the

gamemaster to decide as he fleshes out the details. Create

all alien creatures, intelligent or not, by using the following

rules. If they are determined to be intelligent, build them into

an alien race using the information in the New Civilizations

section.

The dice rolls are meant as guidelines. Because they are

random, improbable creatures may result. Feel free to pick

and choose instead of rolling dice, particularly if you have

something specific in mind!

DETERMINING DOMINANT LIFE FORM

form

Dice

Roll

01-04

05-07

08-14

15-20

21-35

36-50

51-96

96-00

The

percentile

is 83,

indicating

Dominant

Life Form

Plants

Lower Animals

Insects/Arthropods

Birds/

Mammals

roll

that

Fish

Avians

Special

for

it is a

Spartal

mammal.A

Amphibians/Reptiles

dice

IV's

second

dominant

dice roll of 39 indicates that it is not sentient This should be

recordep on the Alien Creature Log.

Suppose that the dominant life form on Spartal IV had

been sentient, the dice would have been rolled again to see

if another race also existed, The roll of 48 indicates that the

second most important race is a bird or avian creature. The

Percent

Sentient

roll

is 05,

indicating

that

it

might

gent, but the confirming roll is 72, and so it is not.

8

Percent

Sentient

1%

0%

3%

5%

7%

7%

10%

90%

life

percentile

be

intelli-

Page 10

Alien Attributes

Intelligent (sentient) alien creatures have 7 attributes just

like other player character or NPC races. If they are not sentient, however, alien creatures use only 3 standard attributes

(STR, END and DEX) and one special attribute indicating its

level of animal intelligence, or mentation; this special attribute is called the mentation rating (MENT), as described

below. Non-intelligent alien creatures normally have no CHA,

LUC, or PSI scores, though this may not hold for special cases.

A race may have a PSI rating, and an individual pet might

even be said to have a CHA score, if it is intelligent enough

to be persuasive in some manner.

Attribute Scores For STR, END, and DEX

For alien creatures of all types, STR, END, and initial DEX

scores are determined by the table below, as well as the

damage they do in unarmed combat or any natural armor

protection they may have. These scores are determined by

the creature's size and its type. For plants and special creatures, the gamemaster is on his own.

It is recommended that the gamemaster design most

sentient races to be small, medium, or large in size. As with

the other creation systems, the information designed here

may be used or not as the gamemaster sees fit.

To use the table for the dominant race, find the creature

type in the left-hand column and its size in the top row. To

use the table for other animals, roll percentile dice two times.

The first roll tells which type the creature is, and the second

roll tells what its size is. Cross-index the creature type in the

left hand column and the size in the right-hand column; the

numbers in the box indicate the dice rolls necessary to find

the attributes for the race.

The top number tells what dice to roll to find the average

STR for the race; this dice roll should be made now. It gives

a number that represents the STR of an average, healthy

individual; any one of the creatures may have a higher or

lower STR score, just as player character scores are higher

or lower than average.

The second number tells what dice to roll to find the

average END score for the race; this dice roll should be made

now. Like the STR score, the roll gives a number that represents the END of an average, healthy individual.

The third number tells what dice to roll to find the initial

DEX for the race; this dice roll should be made now. It, too,

gives a number that represents the initial DEX of an average,

healthy individual. This initial DEX will be modified later for

the creature's feeding habits.

The fourth number tells what dice to roll every time the

creature does damage in unarmed combat. This roll is made

only in combat after a successful hit, and is not made at this

time. This roll will be modified by the creature's Skill Rating

in Unarmed Personal Combat, which is determined below.

The fifth number, if any, gives the dice roll to find the

value of the creature's natural armor protection. This roll

should be made at this time.

After the dice rolls are determined, roll the dice as indicated, and record the STR score, the END score, the initial DEX

score, and the armor score on the Alien Creation Record.

AMORPHOUS

01-05

INSECT

0&-20

FISH

21-35

AMPHIBIAN

36-50

REPTILE

51-65

BIRD

66-75

MAMMAL

76-95

STR

Roll

END

Roll

OEXRoll

Armor Roll

Damage Roll

STR

Roll

END Roll

DEXRoll

Armor Roll

Damage Roll

STR

Roll

END

Roll

DEXRoll

Armor Roll

Damage Roll

STR

Roll

END

Roll

DEXRoll

Armor Roll

Damage Roll

STR

Roll

END

Roll

DEXRoll

Armor Roll

Damage Roll

STR

Roll

END Roll

DEXRoll

Armor Roll

Damage Roll

STR

Roll

END

Roll

DEXRoll

Armor Roll

Damage Roll

ALIEN ATTRIBUTE GENERATION TABLE

SIZE (ROLL DIOO)

TINY SMALL SMALL MEIDUM LARGE

01-03

D10

2D10

D100

—

D10-3

2D10

2D10

4D10

+ 65

—

D10-3

D10

2D10

4D10+40

—

D10-3

D10

D10

D100

+ 60

D10-8

D10-3

D104-2

D10

3D10

+ 35

—

D10-3

D10

D10-2

+ 40

3D10

—

D10-3

D10

D10

3D10+10

—

D10-3

VERY

04-15

D10

+ 8

4D10+1Q

D100

D10-5

D10-3

4D10

+ 10

4D10

+ 10

4D10

+ 60

D10-5

D10

2D10

+ 5

3D10

+ 15

3D10

+ 40

D10-5

D10-3

2D10

+ 5

2D10

+ 5

D100

+ 40

D10-7

D10-3

3D10

2D10

+ 5

3D10+30

—

D10-3

D10

+ 8

2D10

+ 35

3D10

—

D10-3

2D10+5

2D10

+ 5

3D10+20

—

D10-3

16-36

3D10

+ 5

4D10

+ 40

D100

D10

D10

4D10

+ 40

4D10

+ 40

4D10

+ 55

D10

D10 + 3

3D10+10

3D10

+ 40

3D10+35

D10

D10

3D10+10

3D10

+ 10

D100

+ 30

D10-6

D10

3D10+15

3D10

+ 10

3D10

+ 30

D10-5

D10

3D10

+ 5

2D10

+ 5

3D10

+ 35

—

D10

3D10

+ 10

3D10

+ 10

3D10

+ 25

—

D10

37-64

3D10

+ 20

4D104-80

D100

D100-4

D10

4D10

+ 80

4D10

+ 80

4D10

+ 50

D10 + 5

2D10

3D10+30

3D10+70

3D10

+ 30

D10 + 5

D10

+ 3

3D10

+ 30

3D10

+ 30

4D10

+ 30

D10-5

D10

+ 3

3D10

+ 40

3D10

+ 30

3010+30

B.10

D10 + 3

3D10

+ 20

2D10

+ 15

3D10

+ 35

—

D10

3D10-f30

3D10

+ 30

3D10+30

D10-5

D10

+ 3

65-85

3D10+45

4D10 + 125

D100

D100-4

D10 + 3

4D10

+ 125

4D10

+ 125

4D10

+ 35

D10-f15

3D10

3D10

+

60

3D10 + 115

3D10 + 25

D10+10

2D10

3D10

+ 60

3D10

+ 60

4D10

+ 20

D10-4

2D10

4D10

+ 70

3D10

+ 60

3D10+20

D10 + 5

2D10

3D10

+ 45

2D10

+ 35

3D10

+ 30

—

D10 + 3

3D10

+ 60

3D10

+ 60

3D10

+ 20

D10

2D10

VERY

LARGE

86-97

3D10

+ 70

4D10+170

D100

D100-2

2D10

4D10+170

4D10-M70

3D10

+ 30

D10 + 25

4D10

3D10+90

4D10+160

3D10+20

D10 + 15

2D10

+ 3

3D10

+ 90

3D10

+ 90

4D10+15

D10-3

D10 + 15

4D10+100 3D10+90

3D10

+ 5

D10 + 10

2D10

+ 3

3D10

+ 70

3D10

+ 50

3D10

+ 25

D10-9

2D10

3D10

+ 90

3D10

+ 90

D10 + 5

D10+5

2D10

+ 3

HUGE

98-00

D100

+ 80

D100

+ 225

D100

D100-2

3D10

D100

+ 225

D100 + 225

3D10+15

D10 + 35

5D10

D100+100

D100+175

3D10+15

D10 + 20

3D10

D100+100

D100+100

4D10

+ 5

D10-2

3D10

D100+140

D100

+ 100

3D10-5

D10 + 15

4D10

D100

+ 80

D100

+ 60

3D10

+ 20

D10

3D10

D100+100

D100+100

3D10-5

D10-I-10

3D10

9

Page 11

For the F'lanari, the dominant race on Spartal IV, the

creature type is mammal and its size is large. Cross-indexing

for a large mammal gives the following rolls: 3D10 + 60 for

STR, 3D10 + 60 for END, 3D10 + 20 for DEX, 2D10 for damage,

and D10 for armor.

The STR roll of 3, 5, and 7 give a total of 15; adding 60

gives an average STR of 75. The END rolls of 7, 5, and 10 give

a total of 22; adding 60 gives and average END of 82. The

initial DEX rolls of 9, 6, and 9 give a total of 23; adding 20

gives a score of 44, which will be modified by its feeding

habits. The base damage that the creature does is 2D10; this

will be modified by the creature's feeding habits. The D10

roll for the creature's natural armor is 5, and so the animal's

tough hide gives it some protection.

Attribute Scores For INT, LUC, And PSI

These traits are created only for sentient alien races.

Those new aliens that are not thinking creatures will have a

MENT score instead. These attributes should probably center

around a percentile die roll, just as humans and other known

sentient races do in STAR TREK: The Role Playing Game.

Die modifiers similar to those used for the known player and

non-player races should be developed for each new race as

well. Gamemasters are left to their own discretion here, but

care should be taken to maintain game balance. Gamemas-

ters should be EXTREMELY reluctant to create a race that is