Page 1

Cinema Tools 4

User Manual

Page 2

Copyright © 2009 Apple Inc. All rights reserved.

Your rights to the software are governed by the

accompanying software license agreement. The owner or

authorized user of a valid copy of Final Cut Studio software

may reproduce this publication for the purpose of learning

to use such software. No part of this publication may be

reproduced or transmitted for commercial purposes, such

as selling copies of this publication or for providing paid

for support services.

The Apple logo is a trademark of Apple Inc., registered in

the U.S. and other countries. Use of the “keyboard” Apple

logo (Shift-Option-K) for commercial purposes without

the prior written consent of Apple may constitute

trademark infringement and unfair competition in violation

of federal and state laws.

Every effort hasbeen made to ensure thatthe information

in this manual is accurate. Apple is not responsible for

printing or clerical errors.

Note: Because Apple frequently releases new versions

and updates to its system software, applications, and

Internet sites,images shownin this manualmay be slightly

different from what you see on your screen.

Apple

1 Infinite Loop

Cupertino, CA 95014

408-996-1010

www.apple.com

Apple, the Apple logo, Final Cut, Final Cut Pro,

Final Cut Studio, FireWire, Mac, Mac OS, Monaco, and

QuickTime are trademarks of Apple Inc., registered in the

U.S. and other countries.

Cinema Tools, Finder, and OfflineRT are trademarks of

Apple Inc.

AppleCare is a service mark of Apple Inc., registered in the

U.S. and other countries.

Other company and product names mentioned herein

are trademarks of their respective companies. Mention of

third-party products is for informational purposes only

and constitutes neither an endorsement nor a

recommendation. Apple assumes no responsibility with

regard to the performance or use of these products.

Production stills from the film “Koffee House Mayhem”

provided courtesy of Jean-Paul Bonjour. “Koffee House

Mayhem” © 2004 Jean-Paul Bonjour. All rights reserved.

http://www.jeanpaulbonjour.com

Production stills from the film “A Sus Ordenes” provided

courtesy of Eric Escobar. “A Sus Ordenes” © 2004 Eric

Escobar. All rights reserved.http://www.kontentfilms.com

Page 3

Contents

Welcome to Cinema Tools7Preface

About Cinema Tools7

About the Cinema Tools Documentation8

Additional Resources8

An Overview of Using Cinema Tools9Chapter 1

Editing Film Digitally9

Why 24p Video?12

Working with 24p Sources13

Offline and Online Editing13

Creating the Cinema Tools Database14

Capturing the Source Clips with Final Cut Pro16

Preparing the Clips for Editing19

Creating Cut Lists and Other Lists with Cinema Tools20

How Much Can Be Done from Final Cut Pro?21

Before You Begin Your Film Project23Chapter 2

An Introduction to Film Projects23

Before You Shoot Your Film24

Which Film to Use?24

Transferring Film to Video25

Frame Rate Basics28

Audio Considerations34

Working in Final Cut Pro38

Cinema Tools Workflows41Chapter 3

Basic Film Workflow Steps41

Film Workflow Examples42

Basic Digital Intermediate Workflow Steps46

Digital Intermediate Workflow Using a Telecine49

Working with REDCODE Media51

Creating a Cinema Tools Database53Chapter 4

An Introduction to Cinema Tools Databases53

3

Page 4

Deciding How You Should Create the Database54

Creating and Configuring a New Database58

Working with Databases65Chapter 5

Opening an Existing Database65

Viewing Database Properties66

About the Detail View Window66

Settings in the Detail View Window67

About the List View Window73

Settings in the List View Window74

Finding and Opening Database Records76

Settings in the Find Dialog77

Backing Up, Copying, Renaming, and Locking Databases80

About the Clip Window80

Settings in the Clip Window81

Accessing Information About a Source Clip84

Entering and Modifying Database Information85Chapter 6

About Working with Database Information85

Importing Database Information86

Entering Database Information Manually91

Using the Identify Feature to Calculate Database Information96

Deleting a Database Record98

Choosing a Different Poster Frame for a Clip98

Changing the Default Database Settings99

Changing All Reel or Roll Identifiers100

Verifying and Correcting Edge Code and Timecode Numbers101

Capturing Source Clips and Connecting Them to the Database105Chapter 7

About Source Clips and the Database105

Preparing to Capture105

Generating a Batch Capture List from Cinema Tools109

Connecting Source Clips to the Database115

Fixing Broken Clip-to-Database Links120

Preparing the Source Clips for Editing123Chapter 8

An Introduction to Preparing Source Clips for Editing123

Determining How to Prepare Source Clips for Editing123

Using the Conform Feature125

Reversing the Telecine Pull-Down127

Making Adjustments to Audio Speed139

Synchronizing Separately Captured Audio and Video139

Dividing or Deleting Sections of Source Clips Before Editing141

4 Contents

Page 5

Editing with Final Cut Pro143Chapter 9

About Easy Setups and Setting the Editing Timebase143

Working with 25 fps Video Conformed to 24 fps144

Displaying Film Information in Final Cut Pro146

Opening Final Cut Pro Clips in Cinema Tools150

Restrictions for Using Multiple Tracks150

Using Effects, Filters, and Transitions151

Tracking Duplicate Uses of Source Material157

Ensuring Cut List Accuracy with 3:2 Pull-Down or 24 & 1 Video158

Generating Film Lists and Change Lists159Chapter 10

An Introduction to Film Lists and Change Lists159

Choosing the List Format160

Lists You Can Export161

Exporting Film Lists Using Final Cut Pro166

Creating Change Lists174

Working with XSL Style Sheets189

Export Considerations and Creating Audio EDLs193Chapter 11

About Common Items You Can Export for Your Project193

Considerations When Exporting to Videotape194

Considerations When Exporting Audio194

Exporting an Audio EDL195

Working with External EDLs, XML, and ALE Files201Chapter 12

Creating EDL-Based and XML-Based Film Lists201

Working with ALE Files206

Working with 24p Video and 24 fps EDLs209Chapter 13

Considerations When Originating on Film210

Editing 24p Video with Final Cut Pro211

Adding and Removing Pull-Down in 24p Clips217

Using Audio EDLs for Dual System Sound227

Film Background Basics229Appendix A

Film Basics229

Editing Film Using Traditional Methods234

Editing Film Using Digital Methods236

How Cinema Tools Creates Film Lists241Appendix B

Film List Creation Overview241

About the Clip-Based Method242

About the Timecode-Based Method243

5Contents

Page 6

Solving Problems245Appendix C

Resources for Solving Problems245

Solutions to Common Problems245

Contacting AppleCare Support247

249Glossary

6 Contents

Page 7

Welcome to Cinema Tools

Cinema Tools is a powerful database that tracks Final Cut Pro edits for conforming film,

digital intermediate, and 24p video projects.

This preface covers the following:

• About Cinema Tools (p. 7)

• About the Cinema Tools Documentation (p. 8)

• Additional Resources (p. 8)

About Cinema Tools

In today’s post-production environment, it’s common for editors and filmmakers to find

themselves faced with a confounding array of formats, frame rates, and workflows

encompassing a single project. Projects are often shot, edited, and output using completely

different formats at each step.

Preface

For editors and filmmakers who specifically want to shoot and finish on film or use a

digital intermediate workflow, Cinema Tools becomes an essential part of the

post-production process when editing with Final Cut Pro. For example, when working

with film you need to be able to track the relationship between the original film frames

and their video counterparts. Cinema Tools includes a sophisticated database feature

that tracks this relationship regardless of the video standard you use, ensuring that the

film can be conformed to match your Final Cut Pro edits.

Cinema Tools also provides the ability to convert captured video clips to

24-frame-per-second (fps) video. For NTSC, this includes a Reverse Telecine feature that

removes the extra frames added during the 3:2 pull-down process commonly used when

transferring film to video or when downconverting 24p video.

Cinema Tools, in combination with Final Cut Pro, provides tools designed to make editing

film digitally, using digital intermediate processes involving Color, and working with 24p

video easier and more cost effective, providing functionality previously found only on

high-end or very specialized editing systems.

7

Page 8

The integration between Cinema Tools and Final Cut Pro makes it possible to perform

the most common Cinema Tools tasks directly from Final Cut Pro—Cinema Tools performs

the tasks automatically in the background.

About the Cinema Tools Documentation

Cinema Tools comes with the Cinema Tools 4 User Manual (this document), which provides

detailed information about the application. This comprehensive document describes the

Cinema Tools interface, commands, and menus and gives step-by-step instructions for

creating Cinema Tools databases and for accomplishing specific tasks. It is written for

users of all levels of experience. This manual documents not only all aspects of using the

Cinema Tools application, but also all related functions within Final Cut Pro.

Note: This manual is not intended to be a complete guide to the art of filmmaking. Much

of the film-specific information presented here is very general in nature and is supplied

to provide a context for the terminology used when describing Cinema Tools functions.

Additional Resources

Along with the documentation that comes with Cinema Tools, there are a variety of other

resources you can use to find out more about Cinema Tools.

Cinema Tools Website

For general information and updates, as well as the latest news on Cinema Tools, go to:

• http://www.apple.com/finalcutstudio/finalcutpro/cinematools.html

Apple Service and Support Websites

For software updates and answers to the most frequently asked questions for all Apple

products, go to the general Apple Support webpage. You’ll also have access to product

specifications, reference documentation, and Apple and third-party product technical

articles.

• http://www.apple.com/support

For software updates, documentation, discussion forums, and answers to the most

frequently asked questions for Cinema Tools, go to:

• http://www.apple.com/support/cinematools

For discussion forums for all Apple products from around the world, where you can search

for an answer, post your question, or answer other users’ questions, go to:

• http://discussions.apple.com

8 Preface Welcome to Cinema Tools

Page 9

An Overview of Using Cinema Tools

Cinema Tools combined with Final Cut Pro gives unprecedented power to film, digital

intermediate, and 24p video editors.

This chapter covers the following:

• Editing Film Digitally (p. 9)

• Why 24p Video? (p. 12)

• Working with 24p Sources (p. 13)

• Offline and Online Editing (p. 13)

• Creating the Cinema Tools Database (p. 14)

• Capturing the Source Clips with Final Cut Pro (p. 16)

• Preparing the Clips for Editing (p. 19)

• Creating Cut Lists and Other Lists with Cinema Tools (p. 20)

• How Much Can Be Done from Final Cut Pro? (p. 21)

1

Editing Film Digitally

Computer technology is changing the film-creation process. Most feature-length films

are now edited digitally, using sophisticated and expensive nonlinear editors designed

for that specific purpose. Until recently, this sort of tool has not been available to

filmmakers on a limited budget.

Cinema Tools provides Final Cut Pro with the functionality of systems costing many times

more at a price that all filmmakers can afford. If you are shooting with 35mm or 16mm

film and want to edit digitally and finish on film, Cinema Tools allows you to edit video

transfers from your film using Final Cut Pro and then generate an accurate cut list that

can be used to finish the film.

Even if you do not intend to conform the original camera negative, as in a digital

intermediate workflow, Cinema Tools provides a variety of tools for capturing and

processing your film’s video. See About the Digital Intermediate Process for more

information.

9

Page 10

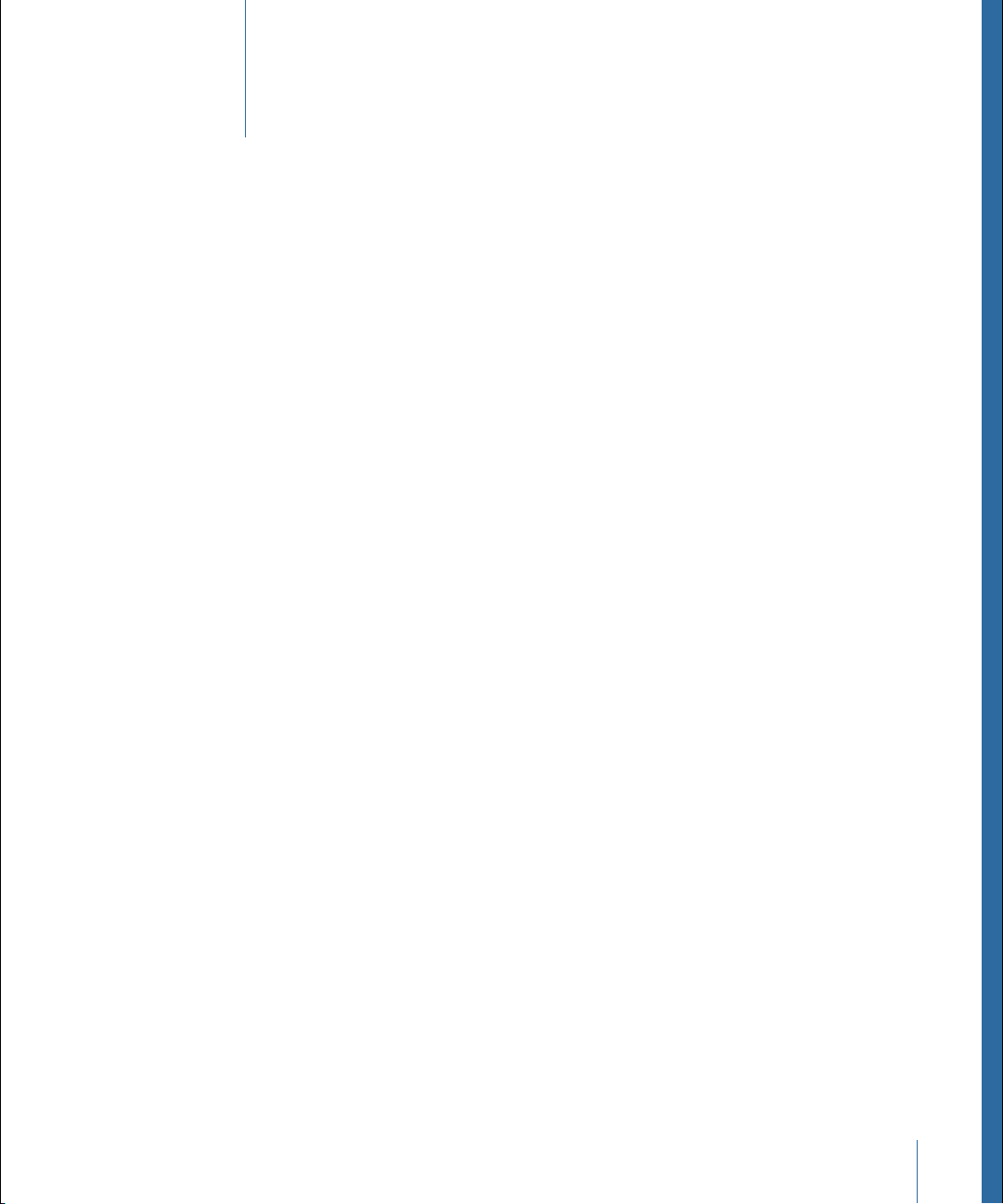

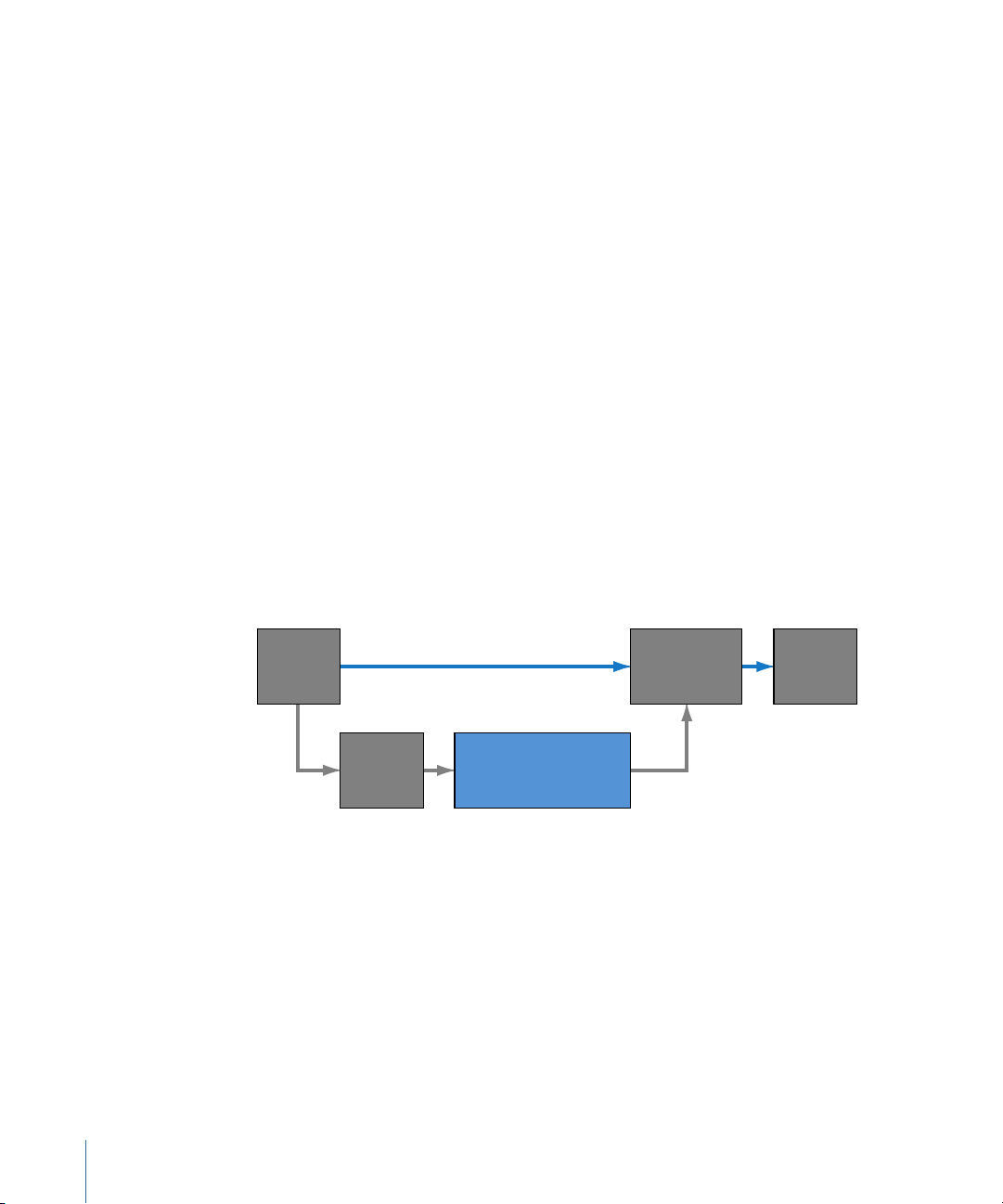

How Does Cinema Tools Help You Edit Your Film?

Cut list

Original camera negative

Convert

film to

video

Conform

original camera

negative

Create

release

print

Shoot film

Edit in Final Cut Pro

with Cinema Tools

For many, film still provides the optimum medium for capturing images. And, if your goal

is a theatrical release or a showing at a film festival, you may need to provide the final

movie on film. Using Final Cut Pro with Cinema Tools does not change the process of

exposing the film in the camera or projecting the final movie in a theater—it’s the part

in between that takes advantage of the advances in technology.

Editing film has traditionally involved the cutting and splicing together of a film workprint,

a process that is time-consuming and tends to discourage experimenting with alternative

scene versions. Transferring the film to video makes it possible to use a nonlinear editor

(NLE) to edit your project. The flexible nature of an NLE makes it easy to put together

each scene and gives you the ability to try different edits. The final edited video is generally

not used—the edit decisions you make are the real goal. They provide the information

needed to cut and splice (conform) the original camera negative into the final movie.

The challenge is in matching the timecode of the video edits with the key numbers of

the film negative so that a negative cutter can accurately create a film-based version of

the edit.

This is where Cinema Tools comes in. Cinema Tools tracks the relationship between the

original camera negative and the video transfer. Once you have finished editing with

Final Cut Pro, you can use Cinema Tools to generate a cut list based on the edits you

made. Armed with this list, a negative cutter can transform the original camera negative

into the final film.

If your production process involves workprint screenings and modifications, you can also

use Cinema Tools to create change lists that describe what needs to be done to a workprint

to make it match the new version of the sequence edited in Final Cut Pro. See Basic Film

Workflow Steps for more details about this workflow.

What Cinema Tools Does

Cinema Tools tracks all of the elements that go into the making of the final film. It knows

the relationship between the original camera negative, the transferred videotapes, and

the captured video clips on the editing computer. It works with Final Cut Pro to store

information about how the video clips are being used and generates the cut list required

to transform the original camera negative into the final edited movie.

10 Chapter 1 An Overview of Using Cinema Tools

Page 11

Cinema Tools also checks for problems that can arise while using Final Cut Pro, the most

common one being duplicate uses of source material: using a shot (or a portion of it)

more than once. Besides creating duplicate lists, you can use Cinema Tools to generate

other lists, such as one dealing with opticals—the placement of transitions, motion effects

(video at other than normal speed), and titles.

Cinema Tools can also work with the production audio, tracking the relationship between

the audio used by Final Cut Pro and the original production audio sources. It is possible

to use the edited audio from Final Cut Pro when creating an Edit Decision List (EDL) and

process (or finish) the audio at a specialized audio post-production facility.

It’s important to understand that you use Final Cut Pro only to make the edit

decisions—the final edited video output is not typically used, since the video it is edited

from generally is compressed and includes burned-in timecode (window burn) and film

information. It is the edit-based cut list that you can generate with Cinema Tools that is

the goal.

About the Digital Intermediate Process

As movies become more sophisticated and the demand for digitally generated special

effects grows, the digital intermediate process, also known as DI, has become increasingly

important to filmmakers. This process often starts with a high-quality scan of the original

film. This scan results in extremely high-quality video, often in the form of digital picture

exchange (DPX) image sequences whose quality rivals or surpasses that of film. This

high-quality video can then be edited, manipulated, and color corrected digitally. The

big difference between this process and the telecine-based film editing process described

previously is that the DI process does not actually conform the original camera

negative—instead, the final digital output is either printed to film or distributed directly.

The term DI is also usedto describe the editing, digital manipulation, and color correction

processes used when the source of the video is a high-resolution camera system that

does not use film at all, such as the RED ONE camera.

The video clips created most often during this process are referred to as 2K video image

sequences. An image sequence is actually a folder containing individual image files for

each video frame. Because of the large size of these video clips, they are not generally

edited directly. Instead, lower-resolution versions of the files are created, usually based

on the Apple ProRes 422 codec, and then edited.

Once the edit is finished, the next step is to use Color to apply any needed color correction.

This color correction is applied to the original 2K media. To accomplish this, an Edit

Decision List (EDL) is exported from Final Cut Pro. This EDL is used to match the edits to

the 2K media, allowing Color to conform and color correct the 2K media.

11Chapter 1 An Overview of Using Cinema Tools

Page 12

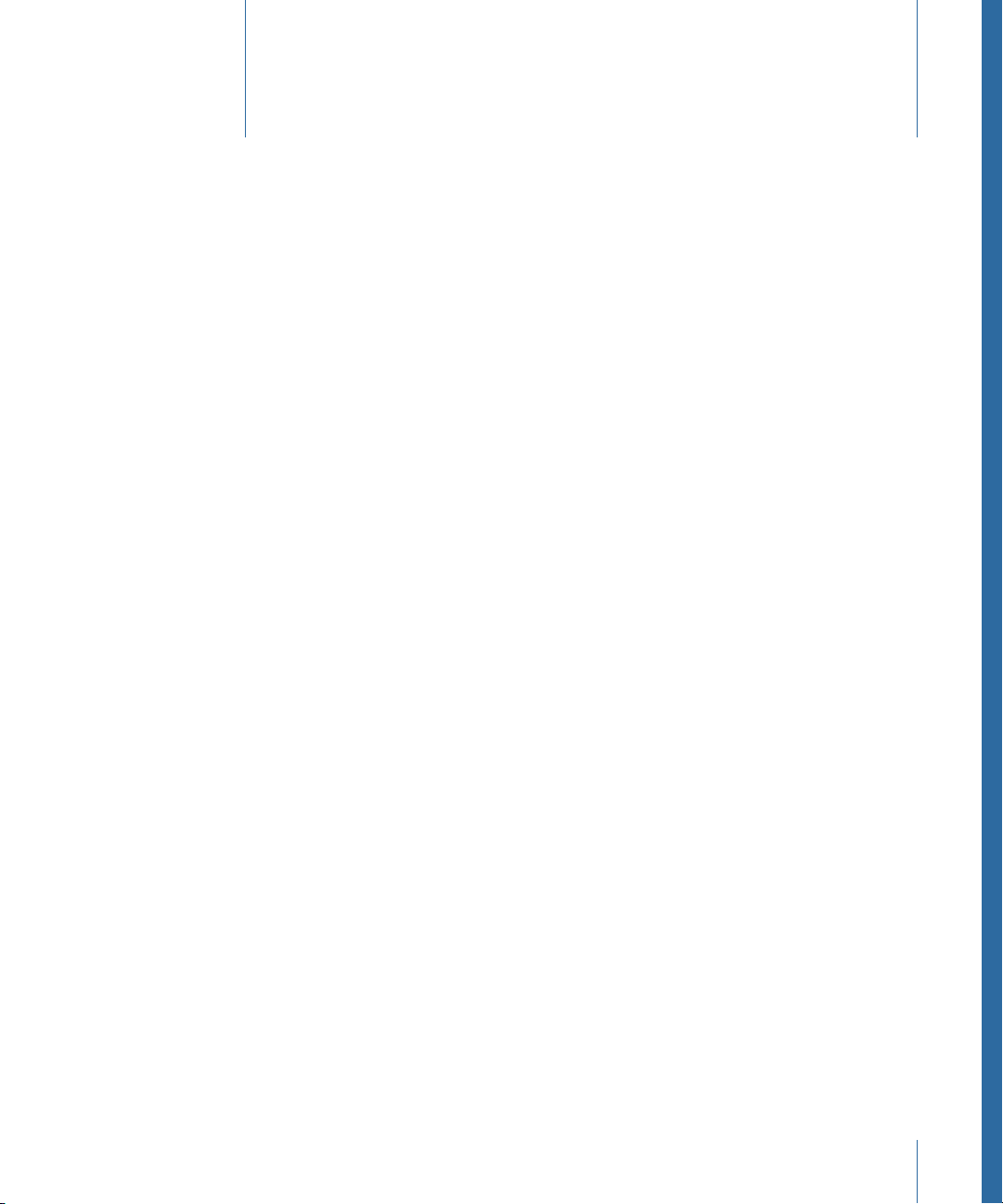

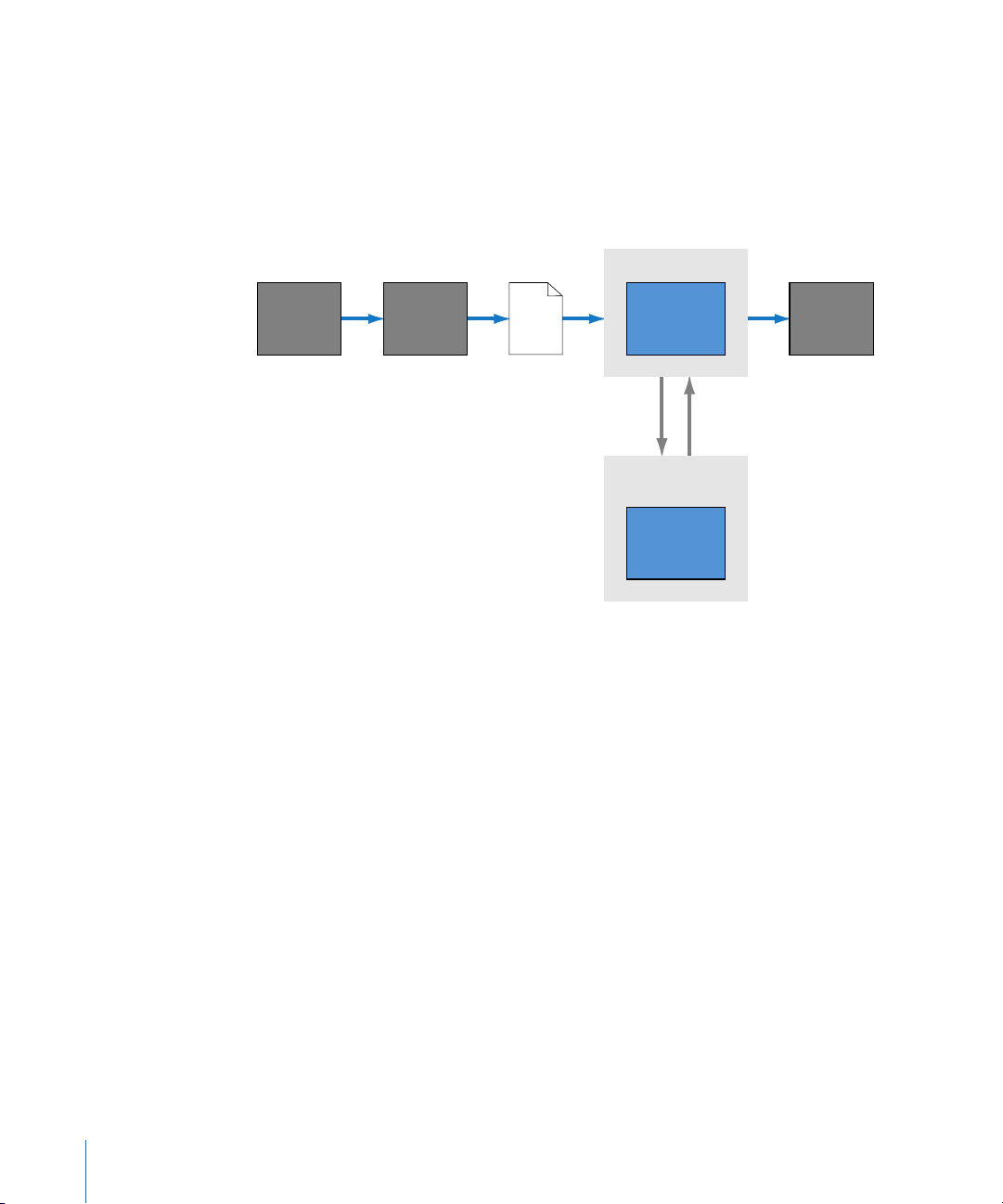

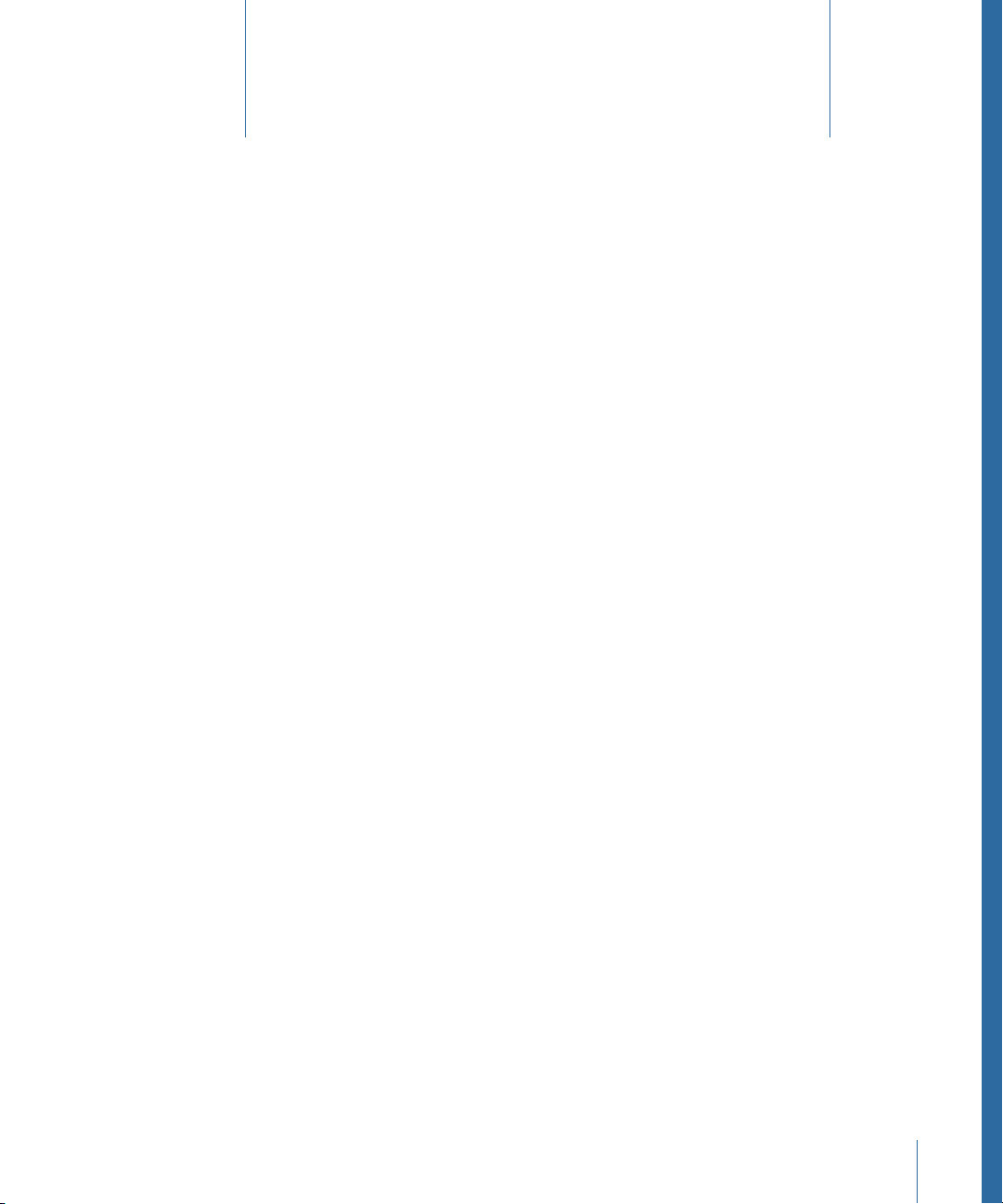

Cinema Tools databases can be used in this process to match the EDL to the 2K media,

EDLOffline

video

Final Cut Pro with

Cinema Tools

Edit

sequence

Scan film

to video

Create

release

print

Shoot film

Color

Conform and

color correct

DPX

image

sequences

DPX

linking the reel names and timecode of each edit to entries in a database created from

a folder of 2K image sequence clips. Using a Cinema Tools database provides powerful

tools to diagnose and resolve any issues that occur, such as nonmatching reel names.

See Basic Digital Intermediate Workflow Steps and Digital Intermediate Workflow Using

a Telecine for details about this workflow.

Why 24p Video?

The proliferation of high definition (HD) video standards and the desire for worldwide

broadcast distribution have created a demand for a video standard that can be easily

converted to all other standards. Additionally, a standard that translates well to film,

providing an easy, high-quality method of originating and editing on video and finishing

on film, is needed.

24p video provides all this. It uses the same 24 fps rate as film, making it possible to take

advantage of existing conversion schemes to create NTSC and PAL versions of your project.

It uses progressive scanning to create an output well suited to being projected on large

12 Chapter 1 An Overview of Using Cinema Tools

screens and converted to film.

Additionally, 24p video makes it possible to produce high-quality 24 fps telecine transfers

from film. These are very useful when you intend to broadcast the final product in multiple

standards.

Page 13

Working with 24p Sources

With the emergence of 24p HD video recorders, there is a growing need for Final Cut Pro

to support several aspects of editing at 24 fps (in some cases, actually 23.98 fps). To this

end, Final Cut Pro and Cinema Tools provide the following:

• The import and export of 24 fps and 23.98 fps EDLs

• The ability to convert NTSC 29.97 fps EDLs to 23.98 fps or 24 fps EDLs

• A Reverse Telecine feature to undo the 3:2 pull-down used when 24 fps film or video

is converted to NTSC’s 29.97 fps

• The ability to remove 2:3:3:2 or 2:3:2:3 pull-down from NTSC media files so you can edit

at 24 fps or 23.98 fps

• The ability to output 23.98 fps video via FireWire at the NTSC standard of 29.97 fps

video

• The ability to match the edits of videotape audio with the original production audio

tapes and generate an audio EDL that can then be used to recapture and finish the

audio if you intend to recapture it elsewhere for final processing

Several of the features mentioned above are included with Final Cut Pro and do not

require Cinema Tools; however, this manual describes all of these features because they

relate to working with 24p, which is of specific interest to many filmmakers. See Frame

Rate Basics for more information about working with the different frame rates.

Offline and Online Editing

If you are working with a high-resolution 24p format, such as uncompressed HD video,

you may need to make lower-resolution copies of your footage to maximize your

computer’s disk space and processing power. In this case, there are four basic steps to

the editing process:

• Production (generating the master video): Transfer film to or natively shoot on

uncompressed 24p HD video.

• Offline edit: Convert footage to NTSC or PAL video (which is generally lower-resolution

than 24p) and edit it.

• Project interchange: Export a Final Cut Pro project or an EDL containing your final edit

decisions.

13Chapter 1 An Overview of Using Cinema Tools

Page 14

• Online edit: Replace low-resolution footage and create a full-resolution master.

24p master

source

Capture

video

Online edit

(24 fps)

Edit

clips

24 fps

EDL

NTSC or

PAL video

24p video

Convert

to 24 fps

Final Cut Pro with Cinema Tools

(offline edit)

Edited 24p

master

See Editing 24p Video with Final Cut Pro for more information.

Creating the Cinema Tools Database

There are a number of issues to take into account when you create your database.

How the Database Works

The database can contain one record or thousands of records, depending on how you

decide to use Cinema Tools. These records are matched to the edits made in Final Cut Pro

so that the cut list can be created. To be valid in a film workflow, a record must have

values for the camera, daily, or lab roll, as well as the edge code (key numbers or ink

numbers). In addition, the record must either have a clip connected to it or have video

reel and video timecode (In point and duration) values.

When you export the cut list after editing the video in Final Cut Pro, Cinema Tools looks

at each edit and tries to find the appropriate record in its database to determine the

corresponding key numbers or ink numbers (edge code). Cinema Tools first looks for a

record connected to the media file used in the edit. If a record is found, Cinema Tools

then locates the file, adds a note to the cut list, and moves on to the next edit.

If no record is found using an edit’s media file, or the file is not located, Cinema Tools

looks at the video reel number to see if any of its records have the same number (“001”

is not the same as “0001”). If so, it then looks to see if the edit’s In and Out points fall

within the range of one of the records. If this condition is also met, the edit is added to

the cut list, and Cinema Tools moves on to the next edit.

If a record cannot be found that uses an edit’s clip pathname or video reel number with

suitable timecode entries, “<missing>” appears in the cut list and a note is added to the

missing elements list. If a record is found but is incomplete (missing the key number, for

example), “<missing>” is placed in those fields and a note is added to the missing elements

list.

14 Chapter 1 An Overview of Using Cinema Tools

See An Introduction to Film Lists and Change Lists and How Cinema Tools Creates Film

Lists for details about this process and the missing elements list.

Page 15

A Detailed or Simple Database?

Cinema Tools is designed to allow you to create a record for an entire camera roll, for

each take, or somewhere in between, depending on how you like to work. Each record

can contain:

• Scene, shot, and take numbers with descriptions

• The film’s camera roll number, edge code, and related video timecode and reel number

• The sound roll and timecode

• A clip poster frame showing a representative frame from the clip

• Basic settings such as film and timecode format

The records can be entered manually or imported from a telecine log. You can modify,

delete, and add records to the database as required, even if it is based on the telecine

log. You can also merge databases. For example, if you are working with dailies, you can

create a new database for each session and merge them all together when the shoot is

complete.

The telecine log from scene-and-take transfers, where only specified film takes are

transferred to video, can provide the basic information for the database. You can add

additional records, comments, and other information as needed.

The telecine log from camera-roll transfers typically provides information for a single

record—the edge code and video timecode used at the start of the transfer. Assuming

continuous film key numbers and video timecode throughout the transfer, that single

record is sufficient for Cinema Tools to generate a cut list for that camera roll.

Importing Telecine Logs

You have a choice of importing the telecine log using Cinema Tools or Final Cut Pro. You

can choose either method according to your workflow.

In both cases, you have the option of assigning a camera letter, which is appended to

the take entries, to the import. This is useful in those cases where multiple cameras were

used for each take. See Assigning Camera Letters for more information.

See Importing Database Information from a Telecine Log or ALE File for more information

about importing telecine logs.

• Importing telecine logs using Cinema Tools: To import a telecine log into Cinema Tools,

you must first have a database open. The database can be an existing one that you

want to add new records to, or it can be a new one with no records.

Once the records have been imported, you can export a batch capture list from

Cinema Tools that you can import into Final Cut Pro to automate the clip capture

process.

15Chapter 1 An Overview of Using Cinema Tools

Page 16

• Importing telecine logs using Final Cut Pro: When you import a telecine log using

Final Cut Pro, you choose whether to import it into an existing Cinema Tools database

or whether a new database should be created.

As records are added to the selected Cinema Tools database, each record also creates

an offline clip in the Final Cut Pro Browser so that clips can be batch captured. The

film-related information from the telecine log is automatically added to each clip. You

can show this information in a variety of ways while editing the clips in Final Cut Pro.

See Displaying Film Information in Final Cut Pro for more information.

Manually Entering Database Records

The most common reason to manually enter a record into the database is that there is

no log available from the film-to-video transfer process. Some film-to-video transfer

methods, such as film chains, do not provide logs.

Each record in a database should represent a media file that has continuous timecode

and key numbers. With scene-and-take transfers, each take requires its own record because

film key numbers are skipped when jumping from take to take during the transfer.

With camera-roll transfers, because the film roll and video recorder run continuously from

start to finish, you require only one record for the entire clip, even if you later break it

into smaller clips (that retain the original timecode) and delete the unused portions. This

is because Cinema Tools can use an edit’s video reel number and edit points to calculate

the appropriate key numbers, as long as the video reel and edit point information is part

of a record.

To manually enter database records, you need to know the key number and video

timecode number for a frame of the clip. This is easiest when the transfer has these values

burned in to the video.

See Creating a Cinema Tools Database for details about creating and managing

Cinema Tools databases.

Capturing the Source Clips with Final Cut Pro

How you capture the source clips with Final Cut Pro depends in large part on the actual

media used for the telecine transfer.

• If you have a telecine log file and the clips are provided using a tape-based system: In this

case, you start by importing the telecine log file into either Cinema Tools or Final Cut Pro.

If you import the telecine log file into Cinema Tools, you then export a batch capture

list for Final Cut Pro. If you import the telecine log file into Final Cut Pro, you can use

the batch capture process to capture the clips.

16 Chapter 1 An Overview of Using Cinema Tools

Page 17

Note: Capturing video clips from a tape-based device may require third-party hardware.

When using serial device control, make sure to calibrate its capture offset. See the

Final Cut Pro documentation for more information. Also see Setting Up Your Hardware

to Capture Accurate Timecode for more information about capturing your clips.

• If youdo not have atelecine log file and theclips are provided usinga tape-based system: In

this case, you use the Final Cut Pro Log and Capture window to manually capture each

clip. Once the clips are captured, you can create a Cinema Tools database based on

them using the Synchronize with Cinema Tools command. In some cases, third-party

hardware is required.

• If the clips are provided using a file-based system, such as on a hard disk or DVD-ROM

disc: In this case, most often you also have a telecine log file. You can import the telecine

log file into Final Cut Pro, copy the files to your computer, and connect them to your

Final Cut Pro project.

• If your clips are coming directly from a digital acquisition source, such as camcorders using

solid-state cards: In this case, you use the Log and Transfer window in Final Cut Pro to

ingest the clips. You then use the Synchronize with Cinema Tools command to create

a Cinema Tools database based on the clips.

Recompressing the Captured Files

Regardless of how you captured your video, you may decide to recompress the files to

make them smaller and easier to work with. For example, taking advantage of the correct

codec may allow you to edit on an older portable computer.

About Compression

Compression, in terms of digital video, is a means of squeezing the content into smaller

files that require less hard disk space and potentially less processor power to display.

The tradeoff is lower-quality images.

It’s important to remember that the edited video that results from Final Cut Pro when

used with Cinema Tools is not typically going to be used in an environment where high

quality would be expected. The most common use of the edited video is to give the

negative cutter a visual guide to go along with the cut list. This means that the quality

of the video only needs to be good enough to make your edit decisions and read the

window burn values. However, because your edit decisions are sometimes based on

subtle visual cues, it’s best not to get too carried away with excess compression.

Important: Do not use long-GOP codecs, such as most MPEG-2, XDCAM, H.264, or HDV

codecs. In addition to being difficult to edit, these files cannot take advantage of the

Reverse Telecine feature.

17Chapter 1 An Overview of Using Cinema Tools

Page 18

Capturing Tactics

There are several approaches to capturing your video and audio. Determining which is

right for you depends on a number of factors, including whether you have device control

of the source tape deck and the transfer type used (camera-roll or scene-and-take).

Device Control

A primary consideration when determining how to capture video and audio is whether

Final Cut Pro supports device control for the deck you use. Device control allows you to

capture precisely the video and audio you want in a way that can be exactly repeated, if

necessary. You can even set up a “batch capture” that automates the process, freeing

you to do other tasks.

Capturing without device control presents several challenges. Clips that are captured

manually do not have precise start and end times. If you intend to match start and end

times from a telecine log, you must trim the clips after capturing them. Additionally,

without device control, a clip’s timecode does not match the timecode on the tape.

Final Cut Pro has a provision for changing a clip’s timecode, but in order for that timecode

to match the source tape, you must have a visual reference (a hole-punched or marked

frame) with a known timecode value.

For more information about device control, see the Final Cut Pro documentation.

Camera-Roll Transfers

Camera-roll transfers require you either to capture the entire tape or to manually capture

a clip for each take. As long as the tape uses continuous video timecode and film key

numbers, Cinema Tools requires only a single database record showing the relationship

between the two.

If Final Cut Pro has device control of your source deck, the best method for capturing the

desired takes is to use the Final Cut Pro Log and Capture window and enter the In and

Out points and reel number for each. You can then use batch capture to finish the process.

It’s not necessary to create a database record for each clip, as long as you do not change

the timecode.

Without device control, you must manually capture either the individual takes you want

or the entire tape. You may need to trim a take that you capture manually, and you will

also have to manually set its timecode to match the source tape. An advantage to

capturing the entire tape is that you only have to set the clip’s timecode once (assuming

that the source tape had continuous timecode). The drawback is the amount of disk space

required, although once the tape is captured, you can use Final Cut Pro to create subclips

of the useful takes and then delete the unused material.

See Capturing Source Clips and Connecting Them to the Database for details about

capturing clips.

18 Chapter 1 An Overview of Using Cinema Tools

Page 19

Scene-and-Take Transfers

Scene-and-take transfers generally result in records in the Cinema Tools database that

are suitable for performing a batch capture. You can export a capture list from

Cinema Tools and import it into the Final Cut Pro Browser. Final Cut Pro can then perform

a batch capture (assuming it can control the source device), creating clips as directed by

the Cinema Tools list. These clips can then be easily linked to records in the Cinema Tools

database.

Finishing with High-Quality Video

If you intend to provide a high-quality video output when you have finished the project,

there are several issues you might need to consider.

When capturing video for the initial offline edit, you can capture with relatively high

compression and include burned-in timecode and key numbers. The compression makes

it easier for your computer to work with the video and requires less hard disk space,

allowing you to capture more video to use for making your edit decisions.

After you have finished the offline edit, you can use Final Cut Pro to recapture just the

video actually used in the edits, using a high-quality codec and a version of the video

without burned-in timecode and key numbers.

See Working with 24p Video and 24 fps EDLs for more information about this process.

Also see your Final Cut Pro documentation for more information about offline and online

editing workflows.

Preparing the Clips for Editing

Cinema Tools includes two features you can use to help prepare the captured clips for

editing.

Reverse Telecine

The Reverse Telecine feature (for NTSC transfers only) provides a means of removing the

extra fields added during the 3:2 pull-down process of the telecine transfer. You need to

do this when you intend to edit the video at 23.98 fps. See Frame Rate Basics for

information about what a 3:2 pull-down is and why you might want to reverse it. See

Reversing the Telecine Pull-Down for details about using the Reverse Telecine feature.

Note: The Reverse Telecine feature cannot be used with temporally compressed video

such as MPEG-2-format video.

Conform

The Conform feature is useful both to correct errors in video clips and to change the

frame rate (timebase) of a clip. Cinema Tools lets you select the frame rate you want to

conform a clip to.

19Chapter 1 An Overview of Using Cinema Tools

Page 20

In order to understand the Conform feature, you need to know a bit about the nature of

QuickTime video files. Each video frame within a QuickTime file has a duration setting

that defines the length of time that a particular frame is displayed (normal NTSC- or

PAL-based QuickTime video has the same duration assigned to all frames). For example,

the NTSC video ratehas a value of 1/30 of a second (actually 1/29.97 of a second) assigned

to each frame. The PAL video rate is 1/25 of a second.

Occasionally, captured video clips have some frames whose durations are set to slightly

different values. Although the differences are not visible when playing the clip, they can

cause problems when Cinema Tools creates the cut list or when you use the Reverse

Telecine feature. In these cases, you can conform the clip to its current frame rate.

There are also times when you may want to change the frame rate of a clip. If you

transferred 24 fps film to video by speeding it up (either to 29.97 fps for NTSC or to 25 fps

for PAL—in each case ensuring a one-to-one relationship between the film and video

frames), the action during playback will be faster than in the original film, and the audio

will need to have its playback speed adjusted to compensate. You can use the Conform

feature to change the clip’s frame rate to 24 fps, making it play back at the original film

rate and stay in sync with the audio. See Using the Conform Feature for details.

Note: Make sure to use the Conform feature on a clip before editing it in Final Cut Pro.

Also make sure the editing timebase in the Final Cut Pro Sequence Preset Editor is set at

the same rate you are conforming to.

See Determining How to Prepare Source Clips for Editing for more information.

Creating Cut Lists and Other Lists with Cinema Tools

There are a number of other useful lists that can be generated at the same time as a cut

list. One film list file can contain any of the following:

• Missing elements list: A list of any required information that could not be found in the

database

• Duplicate list: A list of duplicate usages of the same source material

• Optical list: A list for the effects printer, describing any transitions and motion effects

• Pull list: A list to aid the lab in pulling the required negative rolls

• Scene list: A list of all the scenes used in your program and the shots used in the opticals

You can also export a change list, useful if your production process involves workprint

screenings and modifications. The change list assumes a workprint has been cut to the

specifications of a cut list (or prior change list) and it specifies further changes to make

to the workprint, based on edits you have made to the sequence in Final Cut Pro. See

When Are Change Lists Used in a Film Workflow? for a flow chart of the workprint and

change list process.

20 Chapter 1 An Overview of Using Cinema Tools

Page 21

See An Introduction to Film Lists and Change Lists for more details about all the

film-related lists that are available.

How Much Can Be Done from Final Cut Pro?

Because of the high level of integration between Cinema Tools and Final Cut Pro, you

have several options for each stage in your project’s workflow. For example, should you

import the telecine log into Cinema Tools and export a batch capture list for Final Cut Pro,

or should you import the telecine log directly into Final Cut Pro? Your situation and

preferred working methods will often make this decision for you. Among the

Cinema Tools–related functions you can perform directly from Final Cut Pro are:

• Importing telecine log files

• Conforming 25 fps video to 24 fps

• Reversing the telecine pull-down (using the last settings in Cinema Tools)

• Opening a clip in the Cinema Tools Clip window

• Synchronizing a Cinema Tools database to a group of selected clips

• Exporting film lists and change lists

21Chapter 1 An Overview of Using Cinema Tools

Page 22

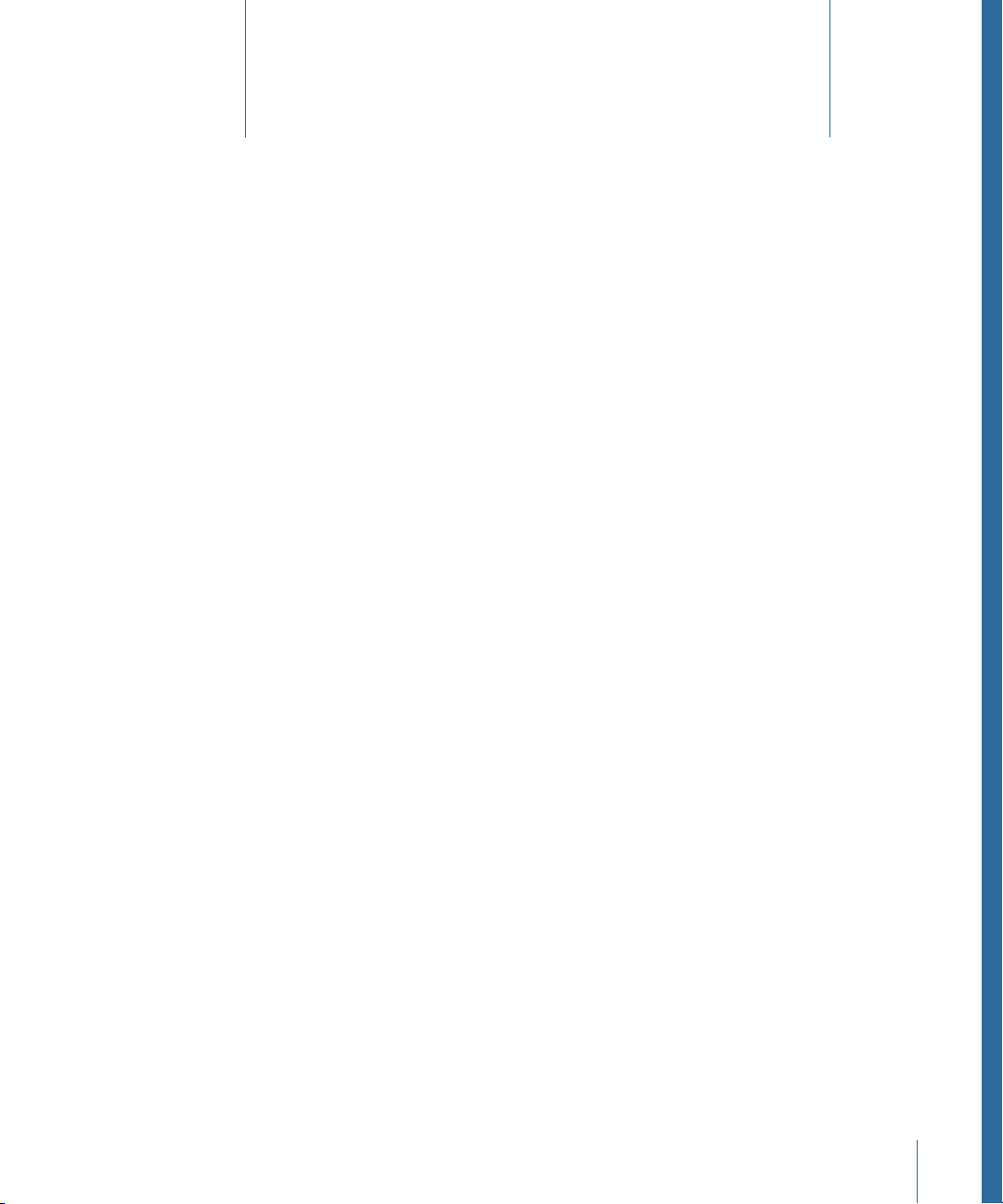

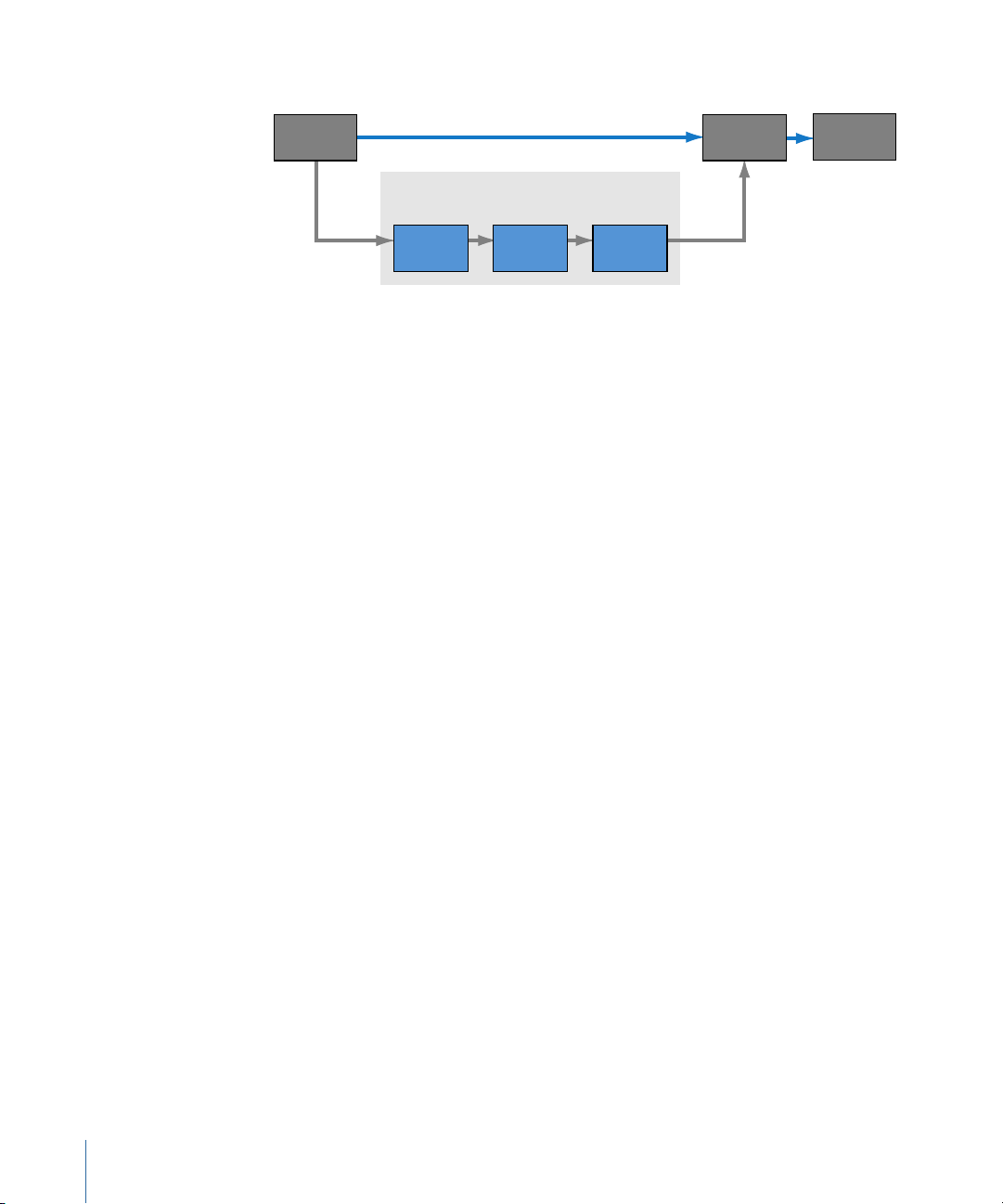

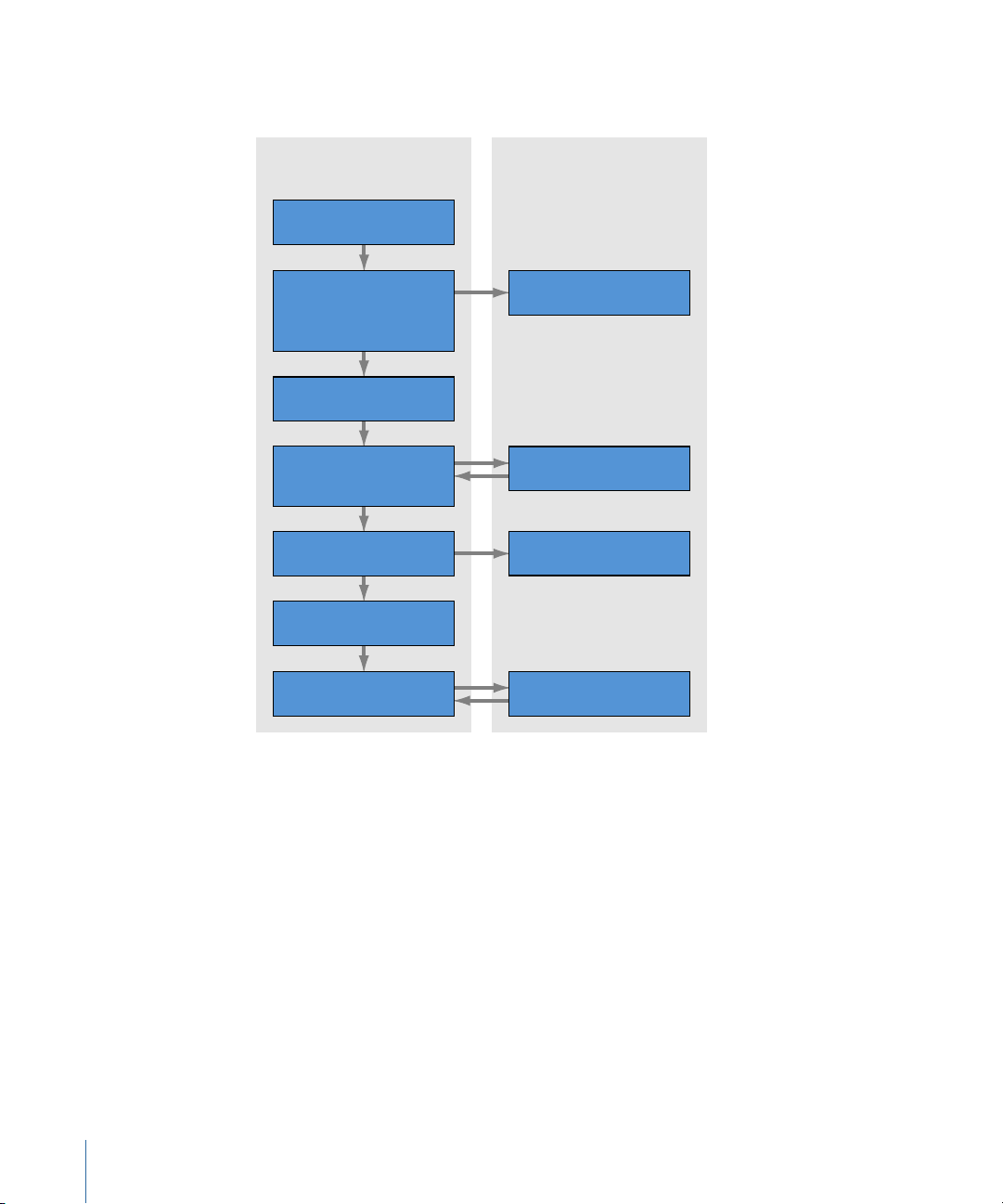

Following is a diagram showing an ideal workflow that focuses on using Final Cut Pro

Steps Performed from

Final Cut Pro

How Cinema Tools

Is Involved

Process clips (if needed)

• Reverse telecine

• Conform (25 @ 24)

Synchronize captured clips

with Cinema Tools database

Edit clips

Import a log into the

Final Cut Pro project,

creating the offline clips

for capture

Batch capture clips

Export lists

Cinema Tools

creates the lists

Cinema Tools

does the processing

A new Cinema Tools

database is created

The clips are connected to

the Cinema Tools database

Create a new

Final Cut Pro project

methods.

In this workflow, you can focus on using Final Cut Pro, and Cinema Tools performs tasks

in the background as needed. You must use Cinema Tools manually if you want to add

information to the database beyond what the telecine log provided, or if you have a

unique issue with reverse telecine and need to configure its settings.

22 Chapter 1 An Overview of Using Cinema Tools

Page 23

Before You Begin Your Film Project

Start planning your project early to ensure its success.

This chapter covers the following:

• An Introduction to Film Projects (p. 23)

• Before You Shoot Your Film (p. 24)

• Which Film to Use? (p. 24)

• Transferring Film to Video (p. 25)

• Frame Rate Basics (p. 28)

• Audio Considerations (p. 34)

• Working in Final Cut Pro (p. 38)

2

An Introduction to Film Projects

Successful film production requires thorough planning well before exposing the first

frame. Besides the normal preparations, additional issues must be considered when you

intend to edit the film digitally. These issues may affect the film you use, how you record

your sound, and other aspects of your production.

This chapter provides basic information about many of the issues you will face:

• Which film to use

• Choices for transferring the film to video

• Frame rate issues between the film, your video standard, and your editing timebase

• Audio issues such as which recorder and timecode to use and how to synchronize the

audio with the video

• Issues with Final Cut Pro such as selecting a sequence timebase and using effects

Note: Much of this information is very general in nature and is not intended to serve as

a complete guide to filmmaking. The digital filmmaking industry changes rapidly, so what

you read here is not necessarily the final word.

23

Page 24

Before You Shoot Your Film

Before you begin your project, make sure to discuss it with all parties involved in the

process:

• Those providing equipment or supplies used during the production

• Those involved in the actual production

• The facility that will develop your film, create workprints, and create the release print

• The video transfer facility

• The editor using Cinema Tools and Final Cut Pro (if it is not you)

• The negative cutter

• The audio post-production facility

These are people who are experts in their fields. They can provide invaluable information

that can make the difference between a smooth, successful project and one that seems

constantly to run into obstacles.

Be Careful How You Save Money

There are a number of times throughout the film production process when you will get

to choose between “doing it right” and “doing it well enough.” Often your budget or a

lack of time drives the decision. Make sure you thoroughly understand your workflow

choices before making decisions that could end up costing you more, both in time and

money, in the long run. Problems based on choices made early in the process—for

example, deciding not to have a telecine log made—could take you by surprise later.

Having professional facilities handle the tasks they specialize in, especially when you

are new to the process, is highly recommended. You may actually save money by

spending a little for tasks that you could do yourself, such as using an audio

post-production facility.

Also, do not underestimate the importance of using the cut list to conform a workprint

before conforming the negative. Although creating and editing a workprint adds costs

to the project, incorrectly conforming the original camera negative will cause irreparable

harm to your film.

Which Film to Use?

One of the first steps in any film production is choosing the film format to use.

Cinema Tools requirements must be taken into account when making this choice.

Cinema Tools supports 4-perf 35mm, 3-perf 35mm, and 16mm-20 film formats. See Film

Basics for details about these formats.

24 Chapter 2 Before You Begin Your Film Project

Page 25

Your budget will likely determine which format you use. Although it’s generally best to

use the same film format throughout your production, Cinema Tools does not require it.

Each database record has its own film format setting.

Transferring Film to Video

In order to digitally edit your film, you need to transfer it to video so that it can be captured

by the computer. There are a few ways to do this, but an overriding requirement is that

there be a reliable way to match the film’s key numbers to the edited video’s timecode.

This relationship allows Cinema Tools to accurately calculate specific key numbers based

on each edit’s In and Out point timecode values.

You also need to make decisions regarding film and video frame rates used during the

transfer. These affect the editing timebase and impact the accuracy of the cut list that

Cinema Tools generates.

Telecines

By far the most common method of transferring film to video is to use a telecine. Telecines

are devices that scan each film frame onto a charge-coupled device (CCD) to convert the

film frames to video frames. Although a telecine provides an excellent picture, for the

purposes of Cinema Tools the more important benefit is that it results in a locked

relationship between the film and video, with no drifting between them.

Telecines are typically gentler on the film and offer sophisticated color correction and

operational control as compared to film chains, described in Transfer Techniques That

Are Not Recommended. Another advantage is that telecines can create video from the

original camera negative—most other methods require you to create a film positive

(workprint) first. (Although from a budget viewpoint it may be a benefit not to create a

workprint, workprints are generally created anyway since they provide the best way to

see the footage on a large screen and spot any issues that might impact which takes you

use. Even more importantly, they allow you to test the cut list before working on the

negative.)

In addition to providing a high-quality transfer, most modern telecines read the key

numbers from the film and can access the video recorder’s timecode generator, burning

in these numbers on the video output. An additional benefit of the telecine transfer

method is its ability to provide synchronized audio along with the video output. It can

control the audio source and burn in the audio timecode along with the video timecode

and the key numbers.

25Chapter 2 Before You Begin Your Film Project

Page 26

But What If You Want a Clean Master?

If you plan to conform the original camera negative, the presence of burned-in timecode

and key numbers on the video clips you edit in Final Cut Pro may not be a problem,

especially if you are working with a highly compressed video format.

The burned-in numbers can be a problem, however, if you intend to use the edited

video for screenings or for broadcast. As valuable as they are to the editor, the burned-in

numbers can be distracting when watching an edited project. There are two common

methods you can use to minimize this problem:

• Letterbox the video during capture using a 2:35 aspect ratio so that there is enough

room below the video to show the numbers.

• Flash the burn-in information on the first frame only. Although not quite as useful as

a continuous burn-in, this does provide the editor with the ability to ensure that the

relationship of the edge code to the timecode is correct.

In most cases, telecines produce a log file that can provide the basis for the Cinema Tools

database. This allows you to automate capturing the video into the computer.

Increasingly, telecine facilities can also capture the video clips for you, providing the clips

on a DVD disc or FireWire drive, along with the telecine log and videotapes.

Transfer Techniques That Are Not Recommended

There are a couple of transfer techniques that are worth mentioning just to point out

why you should not use them.

Film Chains

You should avoid using a film chain if at all possible. Film chains are relatively old

technology, as compared to telecines. A film chain is basically a film projector linked to

a video camera. Film chains typically do not support features such as reading the key

numbers or controlling video recorders, and they cannot create a positive video from a

film negative. You must create a workprint to use a film chain.

Using a film chain is usually less expensive than using a telecine, although the cost of

creating a workprint partly offsets the lower cost. The biggest challenge is being able to

define the relationship between the film’s key numbers and the video timecode. This is

usually accomplished with hole punches (or some other distinct frame marker) at known

film frames.

Important: Older film chains may not synchronize the film projector tothe video recorder,

potentially causing the film-to-video relationship to drift.

26 Chapter 2 Before You Begin Your Film Project

Page 27

Recording a Projected Image with a Camcorder

Because of the greatly increased chances for error and the additional time you have to

spend tracking key numbers, this method of transfer is strongly discouraged and should

not be considered.

Projecting your film and recording the results using a video camcorder is a method that,

although relatively inexpensive, almost guarantees errors in the final negative cutting.

Telecines and film chains are usually able to synchronize the film and video devices,

ensuring a consistent transfer at whatever frame rates you choose. The projector’s and

video camcorder’s frame rates may be close to ideal but will drift apart throughout the

transfer, making it impossible to ensure a reliable relationship between the film’s key

numbers and the video timecode. You will have to spend extra time going over the cut

list to ensure the proper film frames are being used. Additionally, there may be substantial

flicker in the video output, making it difficult to see some frames and determine which

to edit on.

Because the video is not actually used for anything except determining edit points, its

quality doesn’t matter too much. As with film chains, you have to create a workprint to

project. Being able to proof your cut list before the original camera negative is worked

on is very important with this type of transfer.

How Much Should You Transfer?

Deciding how much of your film to transfer to video depends on a number of issues, the

biggest one probably being cost. The amount of time the telecine operator spends on

the transfer determines the cost. Whether it is more efficient to transfer entire rolls of film

(a “camera-roll” transfer), including bad takes and scenes that won’t be used, or to spend

time locating specific takes and transferring only the useful ones (a “scene-and-take”

transfer) needs to be determined before starting.

Camera-Roll Transfers

Cinema Tools uses a database to track the relationship between the film key numbers

and the video and audio timecode numbers. The database is designed to have a record

for each camera take, but this is not required. If you transfer an entire roll of film

continuously to videotape, Cinema Tools needs only one record to establish the

relationship between the key numbers and the video timecode. All edits using any portion

of that single large clip can be accurately matched to the original camera negative’s key

numbers. A drawback to this transfer method is the large file sizes, especially if significant

chunks of footage will not be used.

27Chapter 2 Before You Begin Your Film Project

Page 28

Additionally, because of the way it is recorded, audio is difficult to synchronize at the

telecine during a camera-roll transfer. During a production, the sound recorder typically

starts recording before film starts rolling and ends after filming has stopped. You also will

often shoot some film without sound (known as MOS shots). This means you cannot

establish audio sync at the start of the film roll and expect it to be maintained throughout

the roll. Instead, each clip needs to be synced individually. The Cinema Tools database

includes provisions for tracking the original production sound rolls and audio timecode.

Once captured, a single large clip can be broken into smaller ones, allowing you to delete

the excess video. Even with multiple clips, it is possible for Cinema Tools to generate a

complete cut list with only one database record. Another approach is to manually add

additional records for each clip, allowing you to take advantage of the extensive database

capabilities of Cinema Tools. See Creating the Cinema Tools Database for a detailed

discussion of these choices.

Scene-and-Take Transfers

Scene-and-take transfers are a bit more expensive than camera-roll transfers, but they

offer significant advantages:

• Scene-and-take transfers make it easier to synchronize audio during the transfer.

• Because the telecine log contains one record per take, it establishes a solid database

when imported into Cinema Tools.

• With an established database, Cinema Tools can export a batch capture list. With this

list (and appropriate device control), Final Cut Pro can capture and digitize the

appropriate takes with minimum effort on your part.

Maintaining an accurate film log and using a timecode slate can help speed the transfer

process and reduce costs.

Frame Rate Basics

When transferring film to video, you need to take into account the differences in film and

video frame rates. Film is commonly shot at 24 frames per second (fps), although 25 fps

is sometimes used when the final project is to be delivered as PAL video (as opposed to

the more common technique of just speeding up 24 fps film to 25 fps). Video can have

a 29.97 fps rate (NTSC), a 25 fps rate (PAL), or either a 24 fps or 23.98 fps rate (24p),

depending on your video standard.

The frame rate of your video (whether you sync the audio during the telecine transfer or

not) and the frame rate you want to edit at can determine what you needto do to prepare

your clips for editing. You may find it useful to read Determining How to Prepare Source

Clips for Editing before you make any decisions about frame rates.

28 Chapter 2 Before You Begin Your Film Project

Page 29

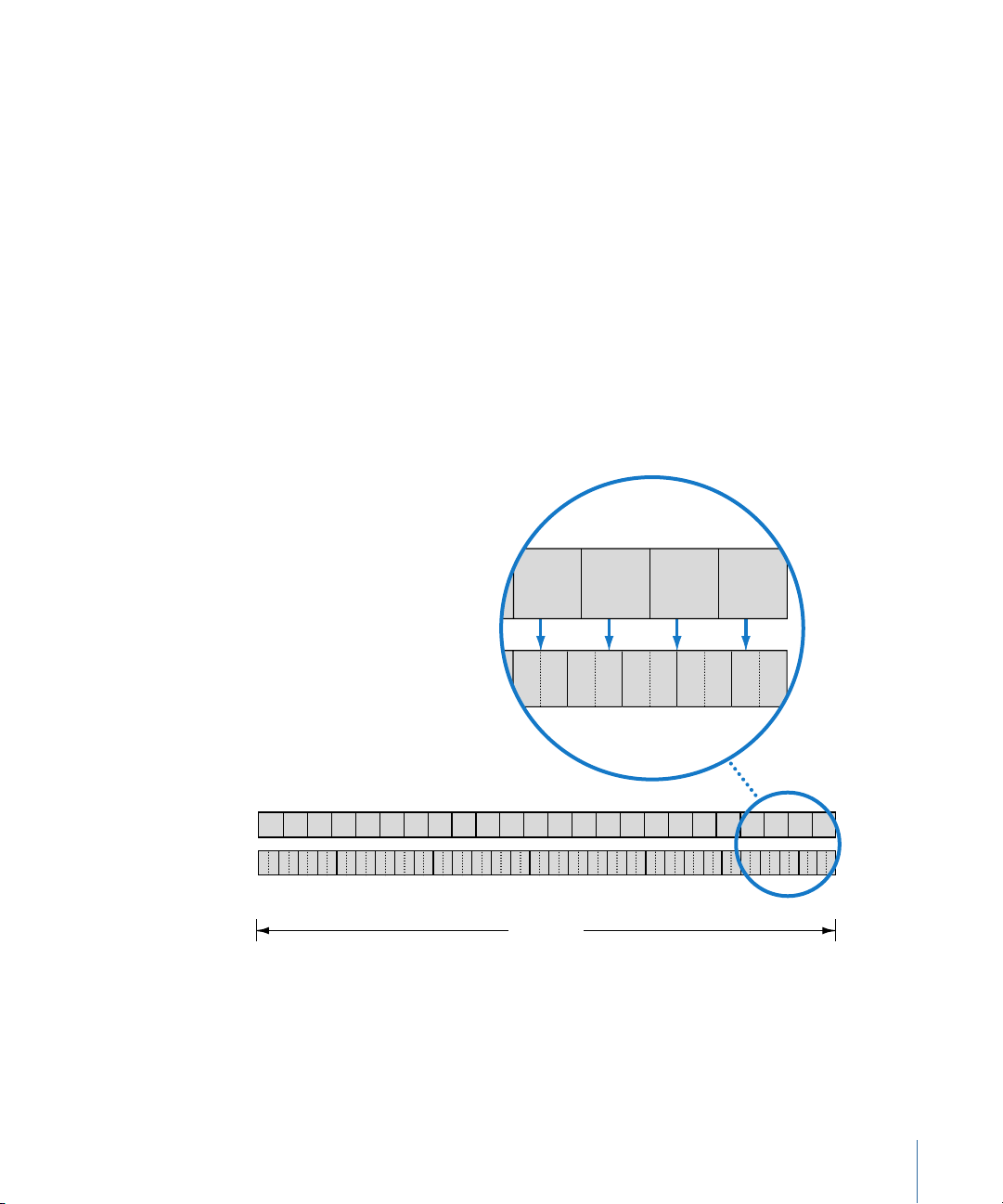

Working with NTSC Video

Before (23.98 fps)

A BA B B CC D D D

A B C D A D A B C D A B C D A B C D A B C D

B C

A A B B B C C D D D A A B B B C C D D D A A B B C C D D D A A B BB CC D D D A BA B B CC D DB D

A B C D

A A B B B C C D D D

Field1Field2Field1Field

2

Field1Field

2

Field1Field

2

Field1Field

2

3:2 Pull-Down

After (29.97 fps)

One second

The original frame rate of NTSC video was exactly 30 fps. When color was added, the rate

had to be changed slightly, to the rate of 29.97 fps. The field rate of NTSC video is 59.94

fields per second. NTSC video is often referred to as having a frame rate of 30 fps, and

although the difference is not large, it cannot be ignored when transferring film to video

(because of its impact on audio synchronization, explained in Synchronizing the Audio

with the Video).

Another issue is how to distribute film’s 24 fps among NTSC video’s 29.97 fps.

The most common approach to distributing film’s 24 fps among NTSC video’s 29.97 fps

is to perform a 3:2 pull-down (also known as a 2:3:2:3pull-down). If you alternate recording

two fields of one film frame and then three fields of the next, the 24 frames in 1 second

of film end up filling the 30 frames in 1 second of video.

Note: The actual NTSC video frame rate is 29.97 fps. The film frame rate is modified to

23.98 fps in order to create the 3:2 pattern.

As shown above, the 3:2 pattern (actually a 2:3:2:3 pattern because frame A is recorded

to two fields followed by frame B recorded to three fields) repeats after four film frames.

Virtually all high-end commercials, movies, and non-livetelevision shows use this process

prior to being broadcast.

29Chapter 2 Before You Begin Your Film Project

Page 30

Note that there is not a one-to-one correspondence between film frames and video

frames after this pull-down occurs. The duration of a video frame is four-fifths the duration

of a film frame. Because of this discrepancy, if you tried to match a specific number of

whole video frames to some number of whole film frames, the durations would seldom

match perfectly. In order to maintain overall synchronization, there is usually some fraction

of a film frame that must be either added to or subtracted from the duration of the next

edit. This means that in the cut list, Cinema Tools occasionally has to add or subtract a

film frame from the end of a cut in order to maintain synchronization. For this reason, if

you edit 3:2 pull-down video, the Cinema Tools cut list is only accurate to within +/–

1 frame on each edit.

This accuracy issue is easily resolved by using the Reverse Telecine feature (or third-party

hardware or software) to remove the extra fields and restore the film’s original 24 fps rate

before you begin editing digitally, providing a one-to-one relationship between the video

and film frames. Setting the Final Cut Pro editing timebase in the Sequence Preset Editor

to 24 fps (or 23.98 fps—see Synchronizing the Audio with the Video) allows you to edit

the video and generate a very accurate cut list. See Determining How to Prepare Source

Clips for Editing for more information about issues related to these options.

What’s an A Frame?

You will see and hear references to “A” frames whenever you are involved with 3:2

pull-down video. As the previous illustration shows, the A frame is the only one that

has all its fields contained within one video frame. The others (B, C, and D frames) all

appear in two video frames. Because the A frame is the start of the video five-frame

pattern, it is highly desirable to have one as the first frame in all video clips. It’s common

practice to have A frames at non-drop frame timecode numbers ending in “5” and “0.”

See About A Frames for more information.

Working with PAL Video

The PAL video frame rate is exactly 25 fps. There are two methods used when transferring

film to PAL: running the film at 25 fps (referred to as the 24 @ 25 method), and adding

two extra fields per second (similar to NTSC’s 3:2 pull-down, referred to as the 24 & 1

method, or the 24 @ 25 pull-down method).

30 Chapter 2 Before You Begin Your Film Project

Page 31

24 @ 25 Method

24 fps

25 fps

1 2 3 4 5 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24

6 7

First frame of next second

1

1

1

1

22334455667788991010111112121313141415151616171718

18 19 20 21 22 23 24

19 20 21 22 23 24

One second

24 fps

25 fps

1 2 3 4 5 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24

6 7

Repeated field

1

1

24

24

22334455667788991010111112121312141315141615171618

17 18 19 20 21 22 23

19 20 21 22 23 24

Repeated field

One second

Running the film at 25 fps sets up a one-to-one relationship between the film and video

frames. The drawback is that the action in the film is sped up by 4 percent, and the audio

will need an identical speed increase to maintain synchronization. To take advantage of

the wide variety of 25 fps video equipment available, you can choose to edit with the

action 4 percent faster. Another option is to use the Cinema Tools Conform feature to

change the clip’s timebase to 24 fps, correcting the speed. The video can then be edited

with Final Cut Pro as long as the sequences using it have a 24 fps timebase.

Note: Final Cut Pro includes an Easy Setup and sequence preset with “24 @ 25” in their

names, as well as a timecode format named “24 @ 25.” These are all intended to be used

with clips that originated as PAL 25 fps video but have been conformed to 24 fps video.

See Working with 25 fps Video Conformed to 24 fps for more information.

24 & 1 Method

Adding two extra video fields per second (also known as the 24 @ 25 pull-down method

in Final Cut Pro) has the advantage of maintaining the original film speed, at the expense

of losing the one-to-one film-to-video frame relationship. This method records an extra

video field every twelfth film frame.

Working with 24p Video

With its frame rate and progressive scanning, 24p video is well suited for use with telecine

transfers. It uses the same frame rate as film, providing a one-to-one relationship between

the film and video frames without requiring a frame rate conversion.

31Chapter 2 Before You Begin Your Film Project

Page 32

Your Final Cut Pro system needs to be equipped with specialized hardware to capture

24p video, either as compressed or uncompressed clips. Alternatively, some DV cameras,

such as the Panasonic AG-DVX100 camcorder, can shoot 24p video and use the 2:3:3:2

pull-down method to record it to tape at 29.97 fps (the NTSC standard). Using Final Cut Pro

and Cinema Tools, you can capture this video and remove the 2:3:3:2 pull-down so that

you can edit it at 24 fps. See Adding and Removing Pull-Down in 24p Clips for more

information.

Note: When used as part of an NTSC system, the 24p videotape recorder’s (VTR’s) frame

rate is actually 23.976 fps (referred to as 23.98 fps) to be compatible with the NTSC 29.97 fps

rate.

Timecode Considerations

There are several general issues related to timecode that you should be aware of. If you’re

using NTSC video, you can also choose between two timecode formats.

General Timecode Tips

When using video or audio equipment that allows you to define the timecode setting, it

is recommended that you set the “hours” part of the timecode to match the tape’s reel

number. This makes it much easier to recognize which reel a clip originated from. It is

also best to avoid “crossing midnight” on a tape. This happens when the timecode turns

over from 23:59:59:29 to 00:00:00:00 while the tape is playing.

You have the option to use record run or free run timecode during the production:

• Record run timecode: The timecode generator pauses each time you stop recording.

Your tape ends up with continuous timecode, because each time you start recording

it picks up from where it left off.

• Free run timecode: The timecode generator runs continuously. Your tape ends up with

a timecode break each time you start recording.

To avoid potential issues while capturing clips, it is strongly suggested that you use the

record run method, which avoids noncontinuous timecode within a tape.

Whenever a tape has noncontinuous timecode (with jumps in the numbers between

takes), make sure to allow enough time (handles) for the pre-roll and post-roll required

during the capture process when logging your clips. See the Final Cut Pro documentation

for additional information about timecode usage.

About NTSC Timecode

Normal NTSC timecode (referred to as non-drop frame timecode) works as you would

expect—each frame uses the next available number. There are 30 frames per second,

60 seconds per minute, and 60 minutes per hour. Because NTSC’s actual frame rate of

29.97 fps is a little less than 30 fps, non-drop frame timecode ends up being slow (by

3 seconds and 18 frames per hour) when compared to actual elapsed time.

32 Chapter 2 Before You Begin Your Film Project

Page 33

To compensate for this, drop frame timecode skips ahead by two frames each minute,

NTSC video frames (29.97 fps)

One second

Clip start

Reverse-telecined video frames (23.98 fps)

1:00 1:01 1:02 1:03 1:04 1:05 1:06 1:07 1:08 1:09 1:10 1:11 1:12 1:13 1:14 1:15 1:16 1:17 1:18 1:19 1:20 1:21 1:22 1:23 2:00

1:00

1:011:021:031:041:051:061:071:08 1:091:101:11 1:12 1:13 1:14 1:151:16 1:171:181:191:20 1:211:221:231:241:251:261:27 1:281:29 2:00

Discarded fields

except those minutes ending in “0.” (Note that it is only the numbers that are skipped—not

the actual video frames.) This correction makes the timecode accurate with respect to

real time but adds confusion to the process of digital film editing.

With non-drop frame timecode, once you find an A frame, you know that the frame at

that frame number and the one five away from it will always be A frames. For example,

if you find an A frame at 1:23:14:15, you know that all frames ending in “5” and “0” will

be A frames. With drop frame timecode, you are not able to easily establish this sort of

relationship.

Note: It is standard practice to have A frames at non-drop frame timecode numbers

ending in “5” and “0.”

It is highly recommended that you use non-drop frame timecode for both the video and

audio in all film editing projects, even though both Cinema Tools and Final Cut Pro are

able to use either type. Whichever you use, make sure to use the same for both the video

and audio tapes.

Note: PAL timecode does not have this issue—it runs at a true 25 fps.

What Happens to the Timecode After Using Reverse Telecine?

The Reverse Telecine feature (used to change 29.97 fps video to 23.98 fps video) directly

affects the timecode of the video frames. Because Cinema Tools must generate new

23.98 fps timecode for the frames (based on the original timecode), you may see a

difference between the burned-in timecode numbers and the numbers shown in

Final Cut Pro. Though the timecode discrepancies between the window burn and

Final Cut Pro timecode may be confusing, Cinema Tools tracks the new timecode of the

23.98 fps video and is able to match it back to its original NTSC or PAL values, and thus

back to the film’s key numbers.

Note: The Reverse Telecine feature is most often used to convert the NTSC video to

23.98 fps to match the audio timecode, but it can also convert the video to 24 fps.

This is what happens to the timecode: reverse telecine removes six frames per second,

so the timecode numbers continue to match at the beginning of each second. This means

that a clip that lasts for 38 seconds when played at its NTSC rate of 29.97 fps will still last

for 38 seconds when played at the reverse-telecined rate of 23.98 fps.

33Chapter 2 Before You Begin Your Film Project

Page 34

In the above illustration, the blue NTSC fields represent fields that are removed during

the reverse telecine process on a clip using traditional 3:2 pull-down. (See Adding and

Removing Pull-Down in 24p Clips for information about 2:3:3:2 pull-down.) The window

burn NTSC timecode will be different from what Final Cut Pro shows for all frames except

the first one of each second, regardless of the clip’s length.

What Happens to the Timecode After Using Conform?

There are three common situations you would use the Conform feature for:

• Converting PAL 25 fps video to 24 fps: The timecode is not changed, which ensures that

an EDL exported after the clips are edited will accurately refer to the original PAL

timecode. The drawback is that the timecode, at 25 fps, no longer accurately represents

the true passage of time when played at 24 fps because each frame is displayed for a

slightly longer time. See Working with 25 fps Video Conformed to 24 fps for more

information.

• Conforming 29.97 fps video to 29.97 fps: The timecode is not changed. This process is

used to correct issues in a QuickTime file prior to using the Reverse Telecine feature.

See Solutions to Common Problems for more information.

• Converting NTSC 29.97 fps video to 23.98 fps: The timecode is altered, with a number

skipped every five frames. This conform situation is rarely used.

See Using the Conform Feature for more information.

Audio Considerations

Because the audio for a film is recorded separately on a sound recorder, there are a

number of issues that you must be aware of and plan for:

• What type of sound recorder to use: For more information, see Choosing a Sound

Recorder.

• What timecode format to use: For more information, see Choosing an Audio Timecode

Format.

• How to mix the final audio: For more information, see Mixing the Final Audio.

• How to synchronize the audio with the video: For more information, see Synchronizing

the Audio with the Video.

Choosing a Sound Recorder

When choosing a sound recorder, you have several options: an analog tape recorder

(typically a Nagra), a Digital Audio Tape (DAT ) recorder, or a digital disc recorder. Whether

analog or digital, make sure the recorder has timecode capability.

34 Chapter 2 Before You Begin Your Film Project

Page 35

Choosing an Audio Timecode Format

Unlike video or film, which must be structured with a specific frame rate, audio is linear

with no physical frame boundaries. Adding timecode to audio is simply a way to identify

points in time, making it easier to match the audio to video or film frames.

During the shoot, you have the choice of which audio timecode standard to use (typically

30 fps, 29.97 fps, 25 fps, 24 fps, or 23.98 fps). You also have the choice, with 30 fps and

29.97 fps, of using drop frame or non-drop frame timecode. For NTSC transfers, it is highly

recommended that you use non-drop frame timecode for both the video and audio

(although Cinema Tools can work with either). See About NTSC Timecode for more

information about drop frame and non-drop frame timecode.

A consideration for the audio timecode setting is how the final audio will be mixed:

• If the final mix is to be completed using Final Cut Pro: The setting needs to match the

Final Cut Pro Editing Timebase setting in the Sequence Preset Editor.

• If thefinal mix isto becompleted at an audio post-productionfacility: The timecode needs

to be compatible with the facility’s equipment.

Note: Make sure to consult with the facility and make this determination before the shoot

begins.

In general, if you are syncing the audio during the telecine transfer, the timecode should

match the video standard (29.97 fps for NTSC, 25 fps for PAL, or 24 fps for 24p). Check

with your sound editor before you shoot to make sure the editor is comfortable with your

choice.

Mixing the Final Audio

The way you mix the final audio depends on how complicated the soundtrack is (multiple

tracks, sound effects, and overdubbing all add to its complexity) and your budget. You

can either finish the audio with Final Cut Pro or have it finished at a post-production

facility.

Finishing the Audio with Final Cut Pro

If you capture high-quality audio clips, you can finish the audio for your project with

Final Cut Pro, which includes sophisticated audio editing tools. Keep in mind, however,

that good audio is crucial to a good film, and a decision not to put your audio in the

hands of an audio post-production facility familiar with the issues of creating audio for

film might lead to disappointing results.

35Chapter 2 Before You Begin Your Film Project

Page 36

You can export the audio from Final Cut Pro as an Open Media Framework (OMF) file for

use at an audio post-production facility. An exported OMF file contains not only the

information about audio In and Out points, but also the audio itself. This means that, for

example, any sound effects clips you may have added are included. When you use an

OMF file, the recording quality must be as high as possible, as this is what the audience

will hear. Make sure to use a good capture device and observe proper recording levels.

Exporting Audio EDLs

Another approach is to use lower-quality clips in Final Cut Pro and then export an audio

Edit Decision List (EDL) for use at an audio post-production facility. There they can capture

high-quality versions of the audio clips straight from the original production audio source

and edit them based on the audio EDL. For this to work, the timecode and roll numbers

of the original sound rolls must be kept track of and used to create the audio EDL.

Audio clips captured as part of video clips do not retain their original timecode and roll

numbers, and the Final Cut Pro EDL cannot be used by an audio post-production facility.

This is most common with clips created from scene-and-take transfers, where the audio