Page 1

Cinema Tools 4

User Manual

Page 2

K

Apple Inc.

Copyright © 2007 Apple Inc. All rights reserved.

Your rights to the software are governed by the

accompanying software license agreement. The owner

or authorized user of a valid copy of Final Cut Studio

software may reproduce this publication for the purpose

of learning to use such software. No part of this

publication may be reproduced or transmitted for

commercial purposes, such as selling copies of this

publication or for providing paid for support services.

The Apple logo is a trademark of Apple Inc., registered

in the U.S. and other countries. Use of the “keyboard”

Apple logo (Shift-Option-K) for commercial purposes

without the prior written consent of Apple may

constitute trademark infringement and unfair

competition in violation of federal and state laws.

Every effort has been made to ensure that the

information in this manual is accurate. Apple is not

responsible for printing or clerical errors.

Note: Because Apple frequently releases new versions

and updates to its system software, applications, and

Internet sites, images shown in this book may be slightly

different from what you see on your screen.

Apple Inc.

1 Infinite Loop

Cupertino, CA 95014–2084

408-996-1010

www.apple.com

Apple, the Apple logo, Final Cut, Final Cut Pro,

Final Cut Studio, FireWire, Mac, Mac OS, Monaco, and

QuickTime are trademarks of Apple Inc., registered in

the U.S. and other countries.

Cinema Tools, Finder, and OfflineRT are trademarks of

Apple Inc.

AppleCare and Apple Store are service marks of

Apple Inc., registered in the U.S. and other countries.

Other company and product names mentioned herein

are trademarks of their respective companies. Mention

of third-party products is for informational purposes

only and constitutes neither an endorsement nor a

recommendation. Apple assumes no responsibility with

regard to the performance or use of these products.

Production stills from the film “Koffee House Mayhem”

provided courtesy of Jean-Paul Bonjour. “Koffee House

Mayhem” © 2004 Jean-Paul Bonjour. All rights reserved.

http://www.jbonjour.com

Production stills from the film “A Sus Ordenes”

provided courtesy of Eric Escobar. “A Sus Ordenes”

© 2004 Eric Escobar. All rights reserved.

http://www.kontentfilms.com

Page 3

1

Contents

Preface 7 An Introduction to Cinema Tools

8

Editing Film Digitally

10

Why 24p Video?

10

Working with 24p Sources

11

Offline and Online Editing

11

About This Manual

12

Apple Websites

Part I Using Cinema Tools

Chapter 1 17 Before You Begin Your Project

17

Before You Shoot Your Film

18

Which Film to Use?

19

Transferring Film to Video

19

Telecines

20

Transfer Techniques That Are Not Recommended

21

How Much Should You Transfer?

22

Frame Rate Basics

23

Working with NTSC Video

25

Working with PAL Video

26

Working with 24p Video

26

Timecode Considerations

29

Sound Considerations

29

Choosing an Audio Recorder

29

Choosing an Audio Timecode Format

30

Mixing the Final Audio

31

Synchronizing the Audio with the Video

33

Working in Final Cut Pro

33

Setting the Editing Timebase for Sequences

33

Outputting to Videotape When Editing at 24 fps

33

Using Effects

3

Page 4

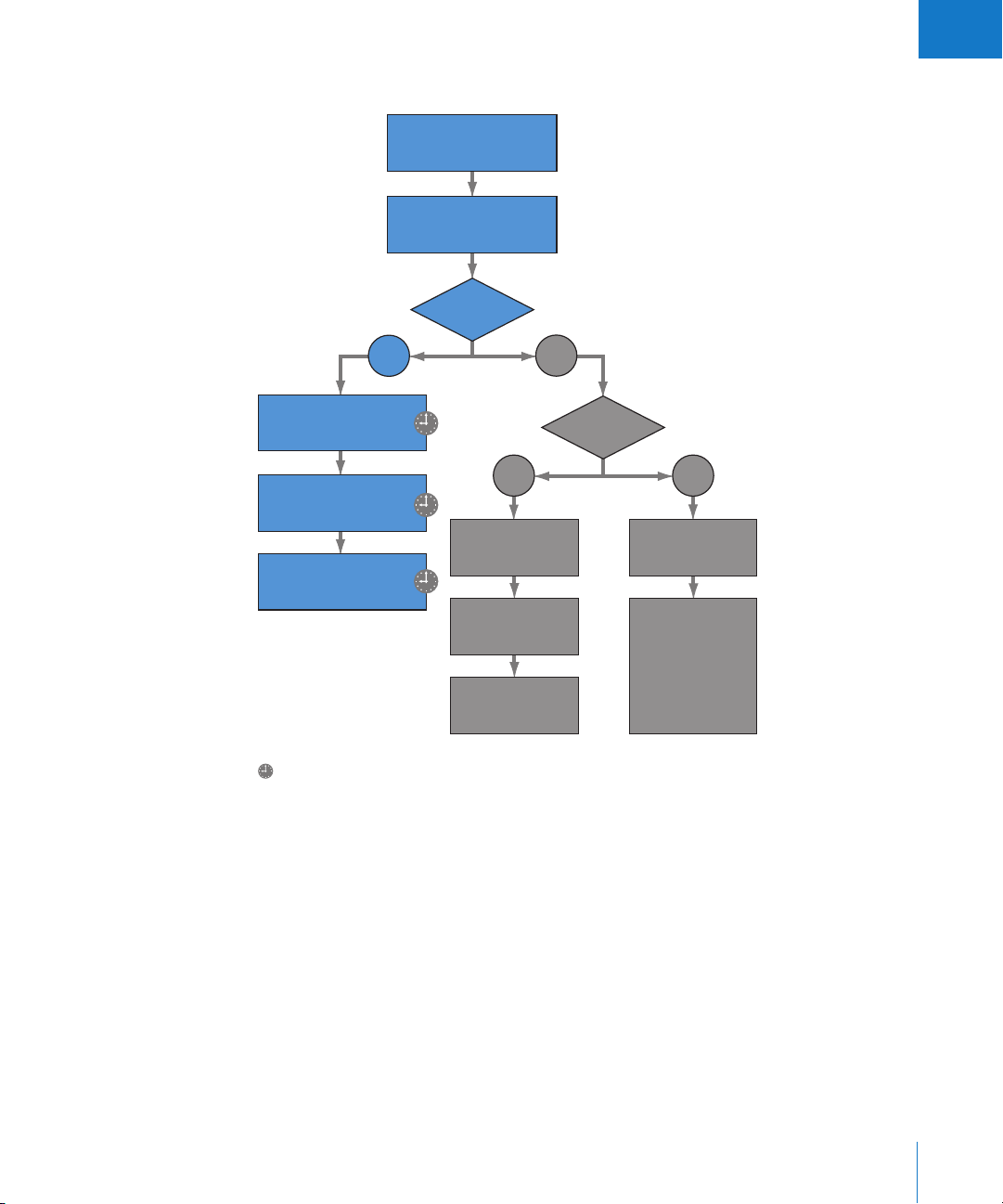

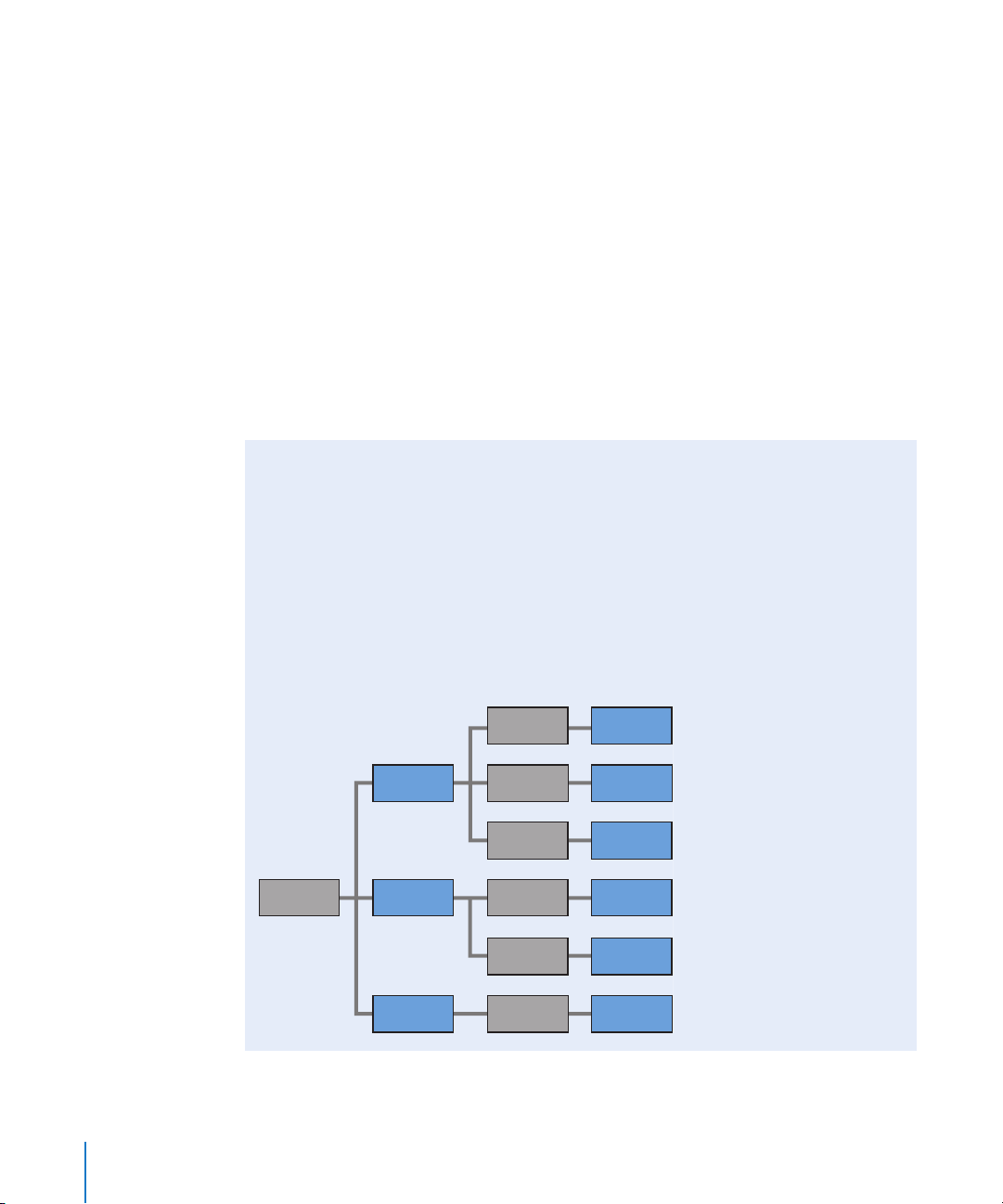

Chapter 2 35 The Cinema Tools Workflow

35

Basic Workflow Steps

36

Creating the Cinema Tools Database

39

Capturing the Source Clips

41

Connecting the Clips to the Database

42

Preparing the Clips for Editing

43

Editing the Clips in Final Cut Pro

43

Generating Film Lists and Change Lists with Cinema Tools

44

Cinema Tools Workflow Examples

44

How Much Can Be Done from Final Cut Pro?

46

If You Used Scene-and-Take Transfers

47

If You Used Camera-Roll Transfers

Chapter 3 51 The Cinema Tools Interface

51

Cinema Tools Windows and Dialogs

62

Dialogs in Final Cut Pro and Cinema Tools

Chapter 4 67 Creating and Using a Cinema Tools Database

69

Deciding How You Should Create the Database

69

Capturing Before You Create the Database

69

If You Have a Telecine Log or ALE File

70

If You Do Not Have a Telecine Log or ALE File

72

Additional Uses for the Database

72

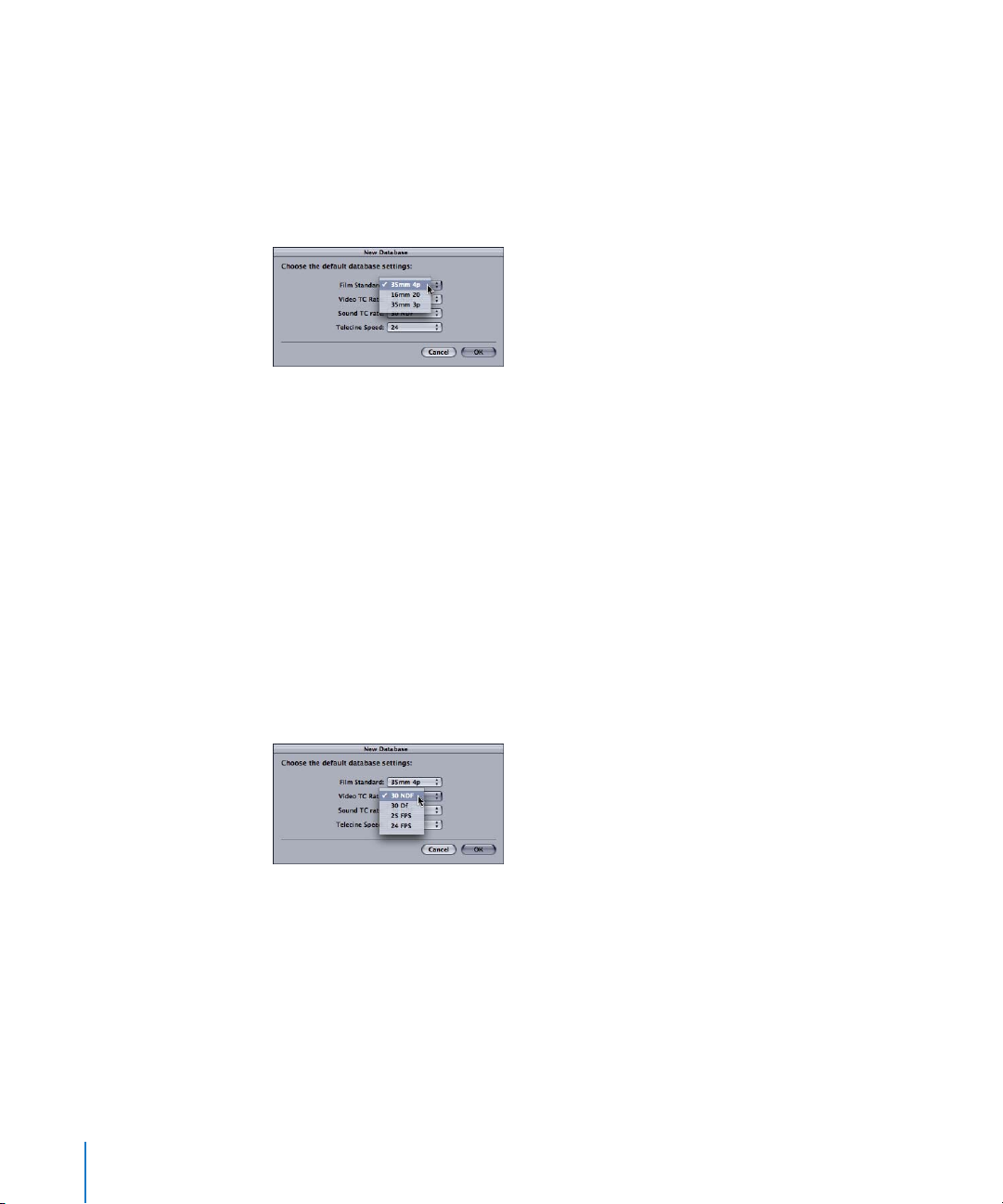

Creating and Configuring a New Database

72

Creating a New Database Using Cinema Tools

73

Creating a New Database Using Final Cut Pro

75

Settings in the New Database Dialog

78

Working with the Database

Opening an Existing Database

78

79

Finding and Opening Database Records

82

Backing Up, Copying, Renaming, and Locking Databases

82

Accessing Information About a Source Clip

83

Entering Information in the Database

83

Importing Database Information

88

Entering Database Information Manually

98

Using the Identify Feature to Enter and Calculate Database Information

10 0

Modifying Information in the Database

10 0

Deleting a Database Record

101

Choosing a Different Poster Frame for a Clip

10 2

Changing the Default Database Settings

10 2

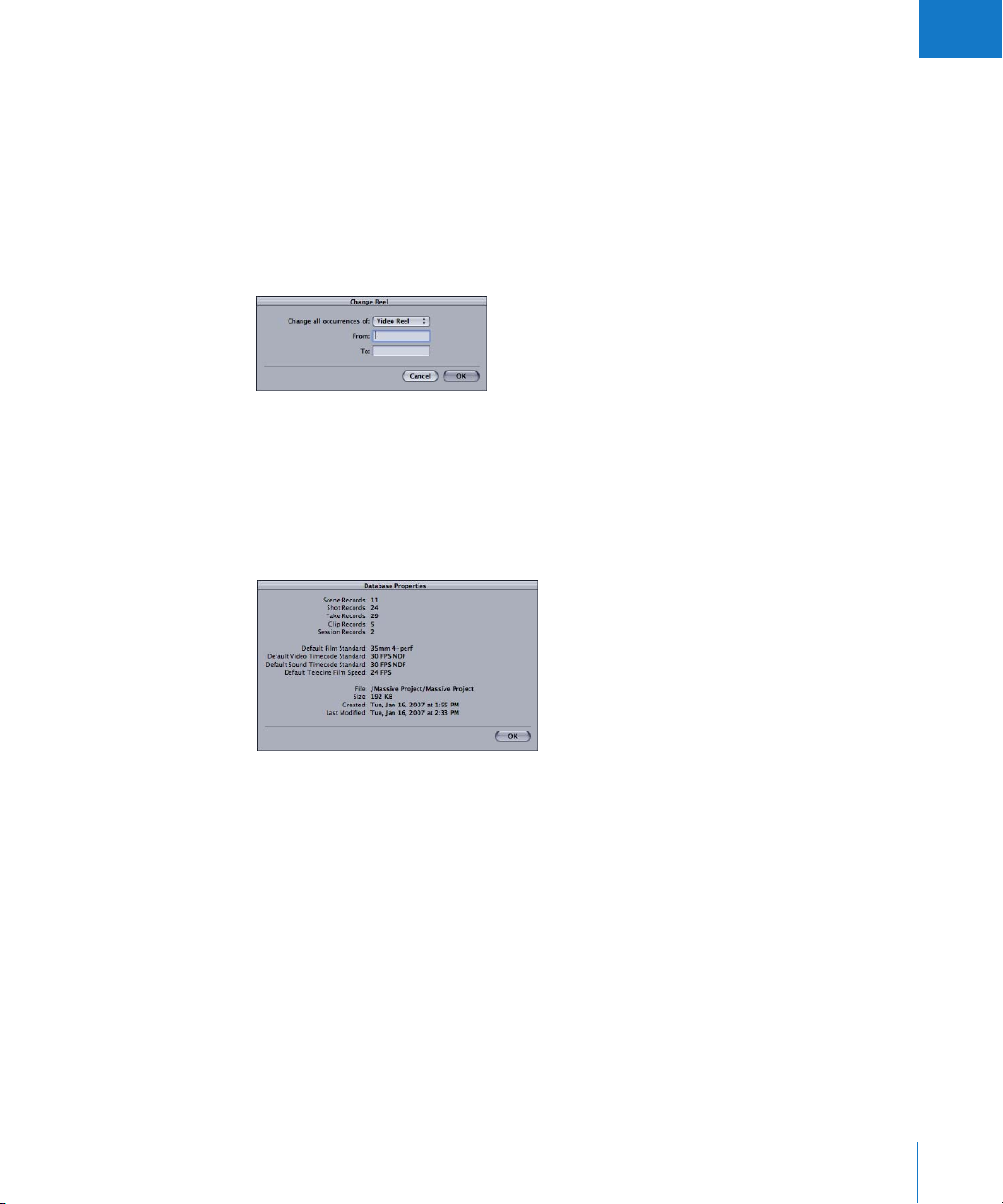

Changing All Reel or Roll Identifiers

10 3

Verifying and Correcting Edge Code and Timecode Numbers

4

Contents

Page 5

Chapter 5 105 Capturing Source Clips and Connecting Them to the Database

10 5

Preparing to Capture

10 6

Avoiding Dropped Frames

10 7

Setting Up Your Hardware to Capture Accurate Timecode

10 8

Considerations Before Capturing Audio

10 8

Generating a Batch Capture List from Cinema Tools

11 4

Considerations Before Capturing Clips Individually

11 4

Connecting Captured Source Clips to the Database

11 6

Using the Connect Clips Command to Connect Source Clips

117

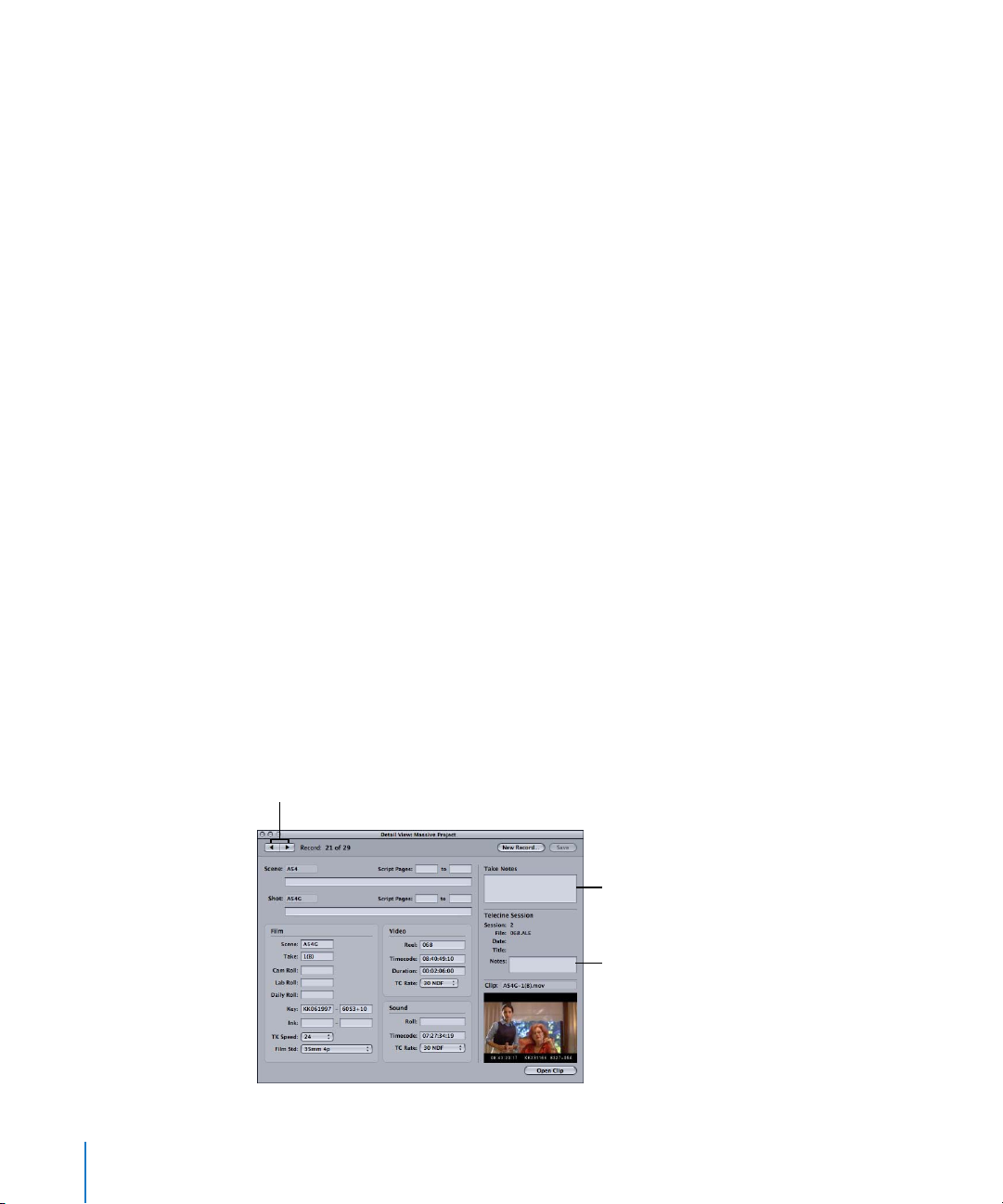

Using the Detail View Window to Connect and Disconnect Source Clips

11 8

Using the Clip Window to Connect or Disconnect Source Clips

12 0

Fixing Broken Clip-to-Database Links

12 0

Reconnecting Individual Clips That Have Been Renamed or Moved

12 0

Locating Broken Links and Reconnecting Groups of Clips That Have Been Moved

Chapter 6 123 Preparing the Source Clips for Editing

12 3

Determining How to Prepare Source Clips for Editing

12 5

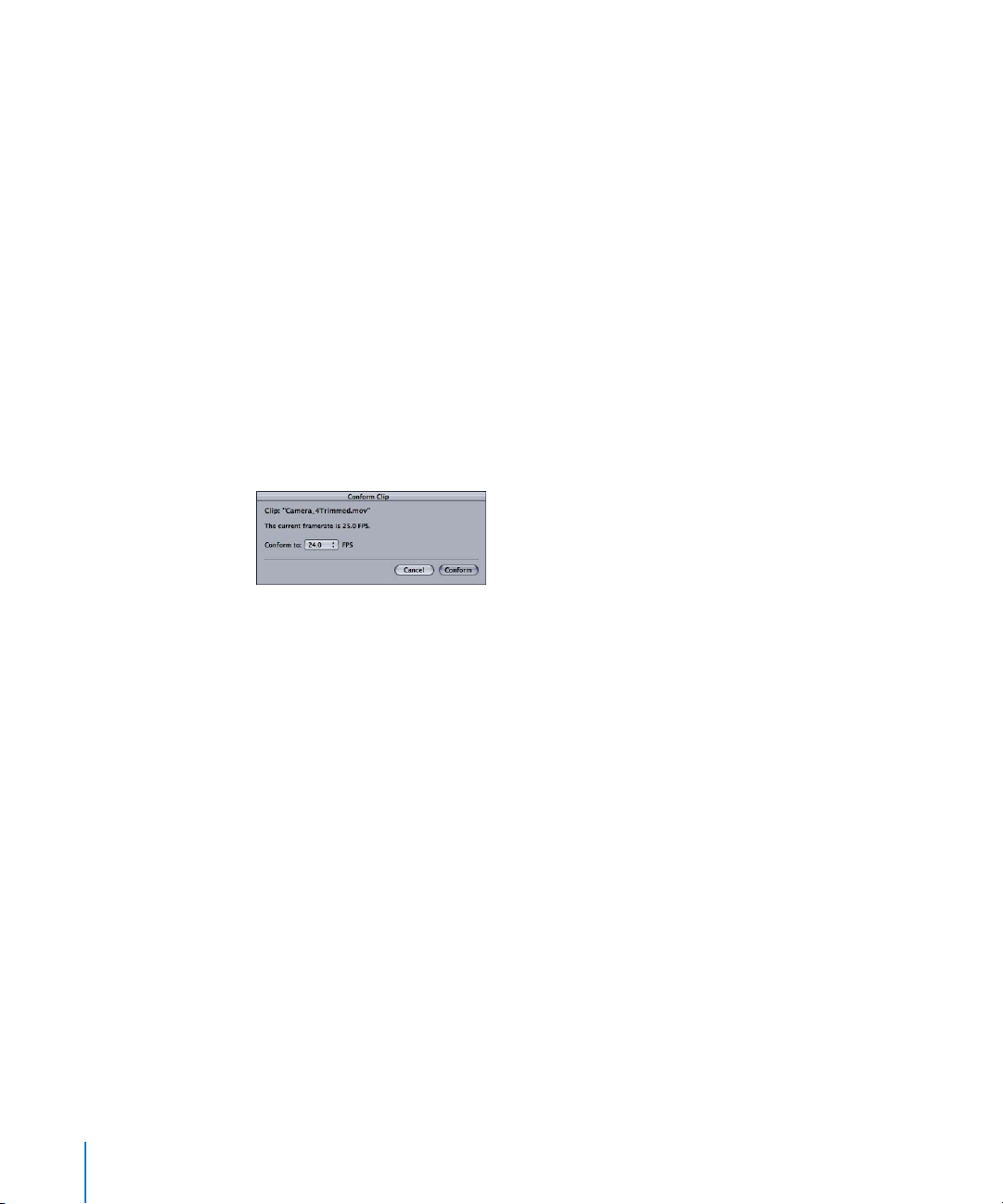

Using the Conform Feature

12 7

Reversing the Telecine Pull-Down

13 7

Making Adjustments to Audio Speed

13 8

Synchronizing Separately Captured Audio and Video

13 9

Dividing or Deleting Sections of Source Clips Before Editing

Chapter 7 143 Editing with Final Cut Pro

14 3

About Easy Setups and Setting the Editing Timebase

14 4

Working with 25 fps Video Conformed to 24 fps

14 6

Displaying Film Information in Final Cut Pro

151

Opening Final Cut Pro Clips in Cinema Tools

Restrictions for Using Multiple Tracks

151

15 2

Using Effects, Filters, and Transitions

157

Tracking Duplicate Uses of Source Material

15 8

Ensuring Cut List Accuracy While Editing 3:2 Pull-Down or 24 & 1 Video

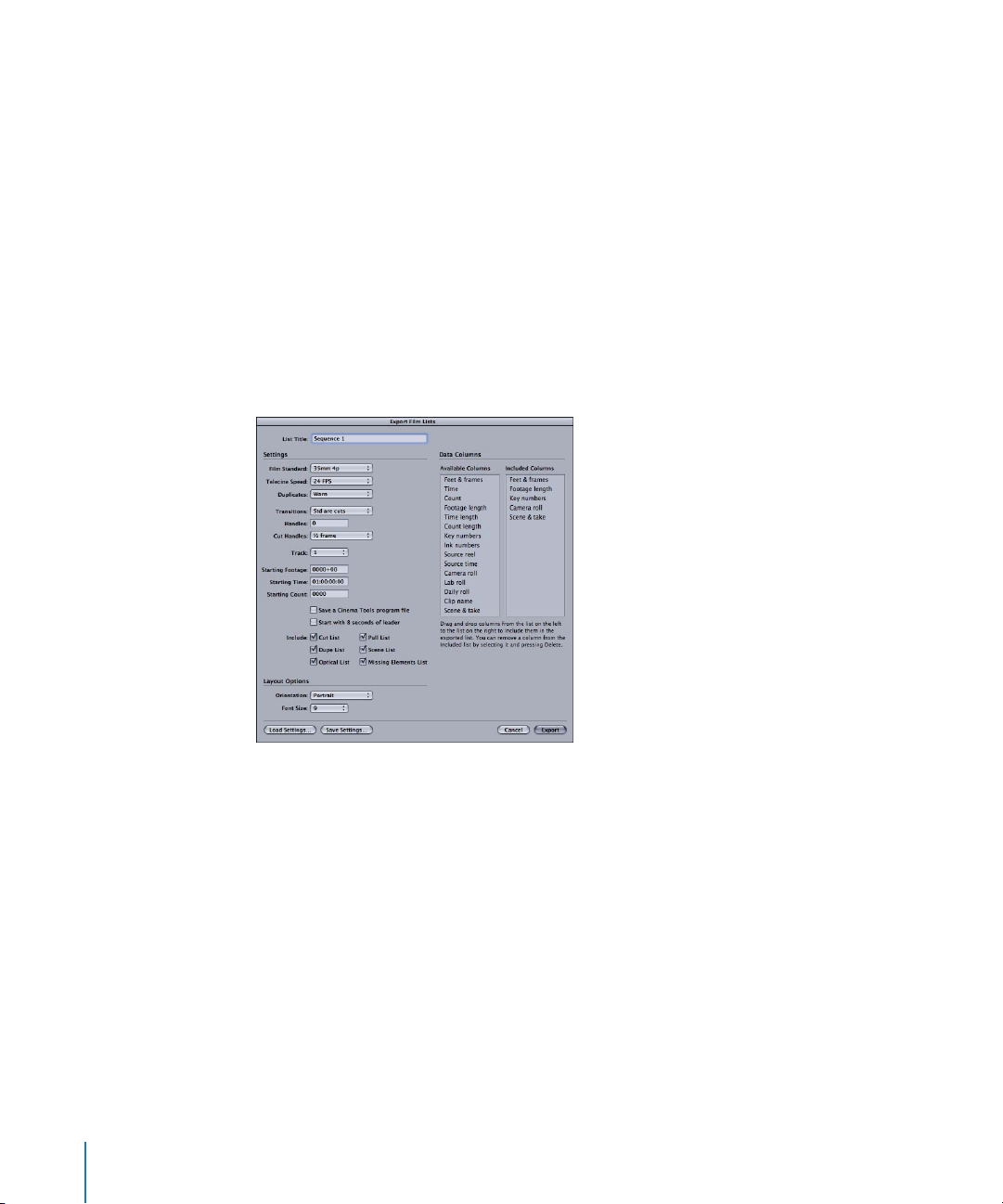

Chapter 8 159 Generating Film Lists and Change Lists

160

Choosing the List Format

161

Lists You Can Export

166

Exporting Film Lists Using Final Cut Pro

17 3

Creating Change Lists

Chapter 9 181 Export Considerations and Creating Audio EDLs

18 2

Considerations When Exporting to Videotape

18 2

Considerations When Exporting Audio

183

Exporting an Audio EDL

Contents

5

Page 6

Chapter 10 189 Working with External EDLs, XML, and ALE Files

18 9

Creating EDL-Based and XML-Based Film Lists

19 4

Working with ALE Files

Part II Working with 24p Video

Chapter 11 199 Working with 24p Video and 24 fps EDLs

200

Considerations When Originating on Film

201

Editing 24p Video with Final Cut Pro

201

Using One Final Cut Pro System for Both 24p Offline and Online Editing

202

Using 24p Video with Final Cut Pro and Cinema Tools

203

Using Final Cut Pro as a 24p Online Editor

205

Using Final Cut Pro as a 24p Offline Editor

208

Adding and Removing Pull-Down in 24p Clips

209

Working with 2:3:3:2 Pull-Down

211

Removing 2:3:3:2 Pull-Down with Final Cut Pro

211

Removing 2:3:3:2 or 2:3:2:3 Pull-Down with Cinema Tools

215

Pull-Down Patterns You Can Apply to 23.98 fps Video

217

Adding Pull-Down to 23.98 fps Video

217

Using Audio EDLs for Dual System Sound

Part III Appendixes

Appendix A 221 Background Basics

221

Film Basics

226

Editing Film Using Traditional Methods

228

Editing Film Using Digital Methods

Appendix B 233 How Cinema Tools Creates Film Lists

235

About the Clip-Based Method

235

About the Timecode-Based Method

Appendix C 237 Solutions to Common Problems and Customer Support

237

Solutions to Common Problems

239 Contacting AppleCare Support

Glossary 241

Index 249

6

Contents

Page 7

An Introduction to Cinema Tools

Cinema Tools with Final Cut Pro gives unprecedented power

to film and 24p video editors.

In today’s post-production environment, it’s common for editors and filmmakers to find

themselves faced with a confounding array of formats, frame rates, and workflows

encompassing a single project. Projects are often shot, edited, and output using

completely different formats at each step. For editors and filmmakers who specifically

want to shoot and finish on film, Cinema Tools becomes an essential part of the

post-production process when editing with Final Cut Pro, allowing you to edit video

transferred from film and track your digital edits for the purpose of conforming

workprints and cutting the original camera negative.

For example, when working with film you need to be able to track the relationship between

the original film frames and their video counterparts. Cinema Tools includes a sophisticated

database feature that tracks this relationship regardless of the video standard you use,

ensuring that the film can be conformed to match your Final Cut Pro edits.

Preface

Also provided is the ability to convert captured video clips to 24 frames per second

(fps) video. For NTSC, this includes a Reverse Telecine feature that removes the extra

frames added during the 3:2 pull-down process commonly used when transferring film

to video or when downconverting 24p video.

Cinema Tools, in combination with Final Cut Pro, provides tools designed to make both

editing film digitally and working with 24p video easier and more cost effective, providing

functionality previously found only on high-end or very specialized editing systems.

The integration between Cinema Tools and Final Cut Pro makes it possible to perform

the most common Cinema Tools tasks directly from Final Cut Pro—Cinema Tools

performs the tasks automatically in the background.

7

Page 8

Editing Film Digitally

Computer technology is changing the film-creation process. Most feature-length films

are now edited digitally, using sophisticated and expensive nonlinear editors designed

for that specific purpose. Until recently, this sort of tool has not been available to

filmmakers on a limited budget.

Cinema Tools provides Final Cut Pro with the functionality of systems costing many

times more at a price that all filmmakers can afford. If you are shooting with 35mm or

16mm film and want to edit digitally and finish on film, Cinema Tools allows you to edit

video transfers from your film using Final Cut Pro and then generate an accurate cut list

that can be used to finish the film.

Even if you do not intend to conform the original camera negative, Cinema Tools

provides a variety of tools for capturing and processing your film’s video.

How Does Cinema Tools Help You Edit Your Film?

For many, film still provides the optimum medium for capturing images. And, if your

goal is a theatrical release or a showing at a film festival, you may need to provide the

final movie on film. Using Final Cut Pro with Cinema Tools does not change the process

of exposing the film in the camera or projecting the final movie in a theater—it’s the

part in between that takes advantage of the advances in technology.

Editing film has traditionally involved the cutting and splicing together of a film

workprint, a process that is time-consuming and tends to discourage experimenting

with alternate scene versions. Transferring the film to video makes it possible to use a

nonlinear editor (NLE) to edit your project. The flexible nature of an NLE makes it easy

to put together each scene and gives you the ability to try different edits. The final

edited video is generally not used—the edit decisions you make are the real goal. They

provide the information needed to cut and splice (conform) the original camera

negative into the final movie. The challenge is in matching the timecode of the video

edits with the key numbers of the film negative so that a negative cutter can accurately

create a film-based version of the edit.

8 Preface An Introduction to Cinema Tools

Page 9

This is where Cinema Tools comes in. Cinema Tools tracks the relationship between the

original camera negative and the video transfer. Once you have finished editing with

Final Cut Pro, you can use Cinema Tools to generate a cut list based on the edits you

made. Armed with this list, a negative cutter can transform the original camera

negative into the final film.

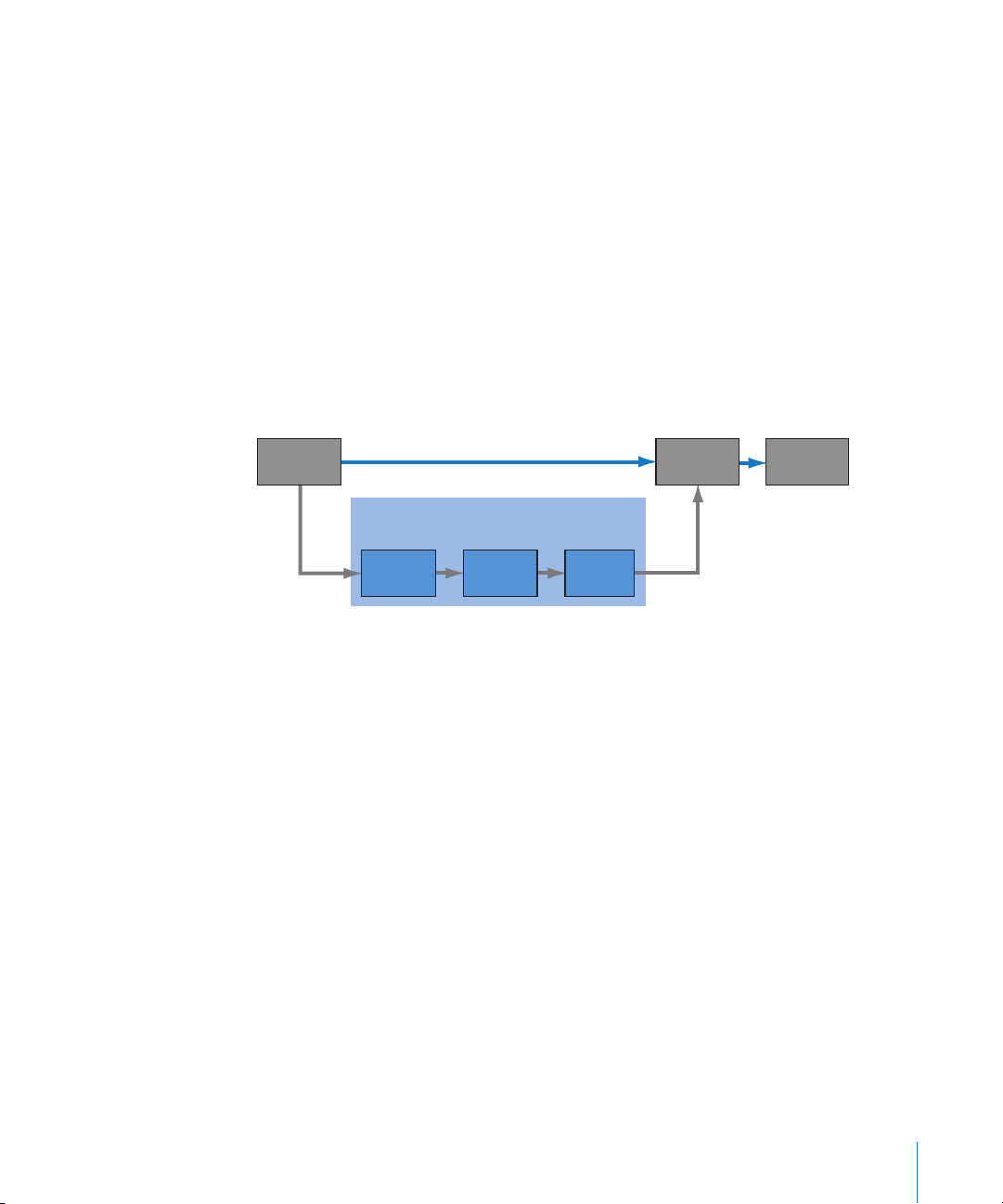

Shoot film

Convert film

to video

Original camera negative

Edit in Final Cut Pro

with Cinema Tools

Conform

original camera

negative

Cut list

Create

release

print

If your production process involves workprint screenings and modifications, you can

also use Cinema Tools to create change lists that describe what needs to be done to a

workprint to make it match the new version of the sequence edited in Final Cut Pro.

What Cinema Tools Does

Cinema Tools tracks all of the elements that go into the making of the final film. It knows

the relationship between the original camera negative, the transferred videotapes, and

the captured video clips on the editing computer. It works with Final Cut Pro to store

information about how the video clips are being used and generates the cut list required

to transform the original camera negative into the final edited movie.

Cinema Tools also checks for problems that can arise while using Final Cut Pro, the

most common one being duplicate uses of source material: using a shot (or a portion

of it) more than once. Besides creating duplicate lists, you can use Cinema Tools to

generate other lists, such as one dealing with opticals—the placement of transitions,

motion effects (video at other than normal speed), and titles.

Cinema Tools can also work with the production sound, tracking the relationship

between the audio used by Final Cut Pro and the original production sound sources. It is

possible to use the edited audio from Final Cut Pro when creating an Edit Decision List

(EDL) and process (or finish) the audio at a specialized audio post-production facility.

It’s important to understand that you use Final Cut Pro only to make the edit

decisions—the final edited video output is not typically used, since the video it is

edited from generally is compressed and includes burned-in timecode (window burn)

and film information. It is the edit-based cut list that you can generate with

Cinema Tools that is the goal.

Preface An Introduction to Cinema Tools 9

Page 10

Why 24p Video?

The proliferation of high definition (HD) video standards and the desire for

worldwide distribution have created a demand for a video standard that can be

easily converted to all other standards. Additionally, a standard that translates well to

film, providing an easy, high-quality method of originating and editing on video and

finishing on film, is needed.

24p video provides all this. It uses the same 24 fps rate as film, making it possible to

take advantage of existing conversion schemes to create NTSC and PAL versions of your

project. It uses progressive scanning to create an output well suited to being projected

on large screens and converted to film.

Additionally, 24p video makes it possible to produce high-quality 24 fps telecine

transfers from film. These are very useful when you intend to broadcast the final

product in multiple standards.

Working with 24p Sources

With the emergence of 24p HD video recorders, there is a growing need for

Final Cut Pro to support several aspects of editing at 24 fps (in some cases, actually

23.98 fps). To this end, Final Cut Pro and Cinema Tools provide the following:

The import and export of 24 fps and 23.98 fps EDLs

The ability to convert NTSC 29.97 fps EDLs to 23.98 fps or 24 fps EDLs

A Reverse Telecine feature to undo the 3:2 pull-down used when 24 fps film or video

is converted to NTSC’s 29.97 fps

The ability to remove 2:3:3:2 or 2:3:2:3 pull-down from NTSC media files so you can

edit at 24 fps or 23.98 fps

The ability to output 23.98 fps video via FireWire at the NTSC standard of

29.97 fps video

The ability to match the edits of videotape audio with the original production audio

tapes and generate an audio EDL that can then be used to recapture and finish the

audio if you intend to recapture it elsewhere for final processing

Several of the features mentioned above are included with Final Cut Pro and do not

require Cinema Tools; however, this book will describe all of these features because

they relate to working with 24p, which is of specific interest to many filmmakers. See

“Frame Rate Basics” on page 22 for more information about working with the different

frame rates.

10 Preface An Introduction to Cinema Tools

Page 11

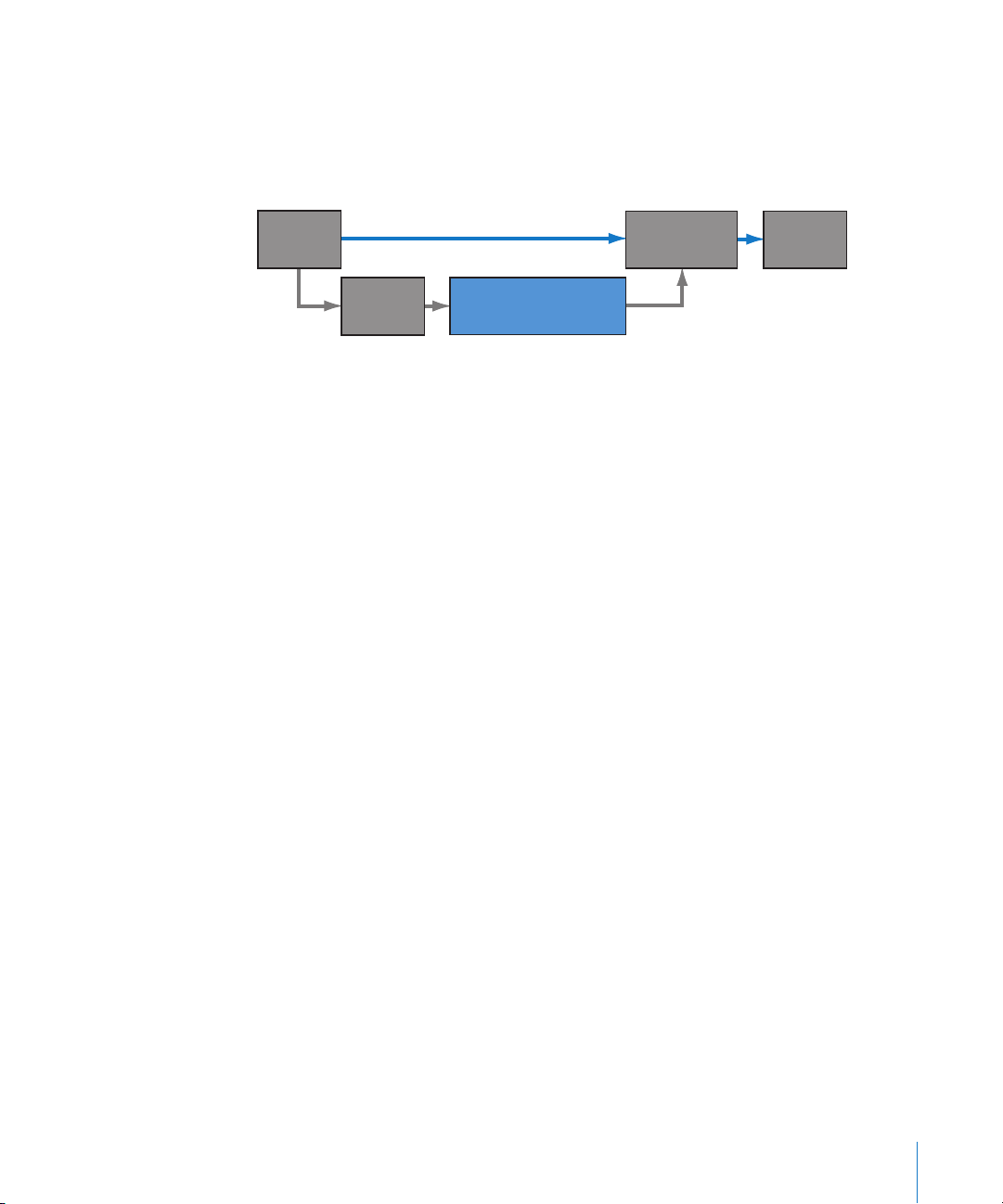

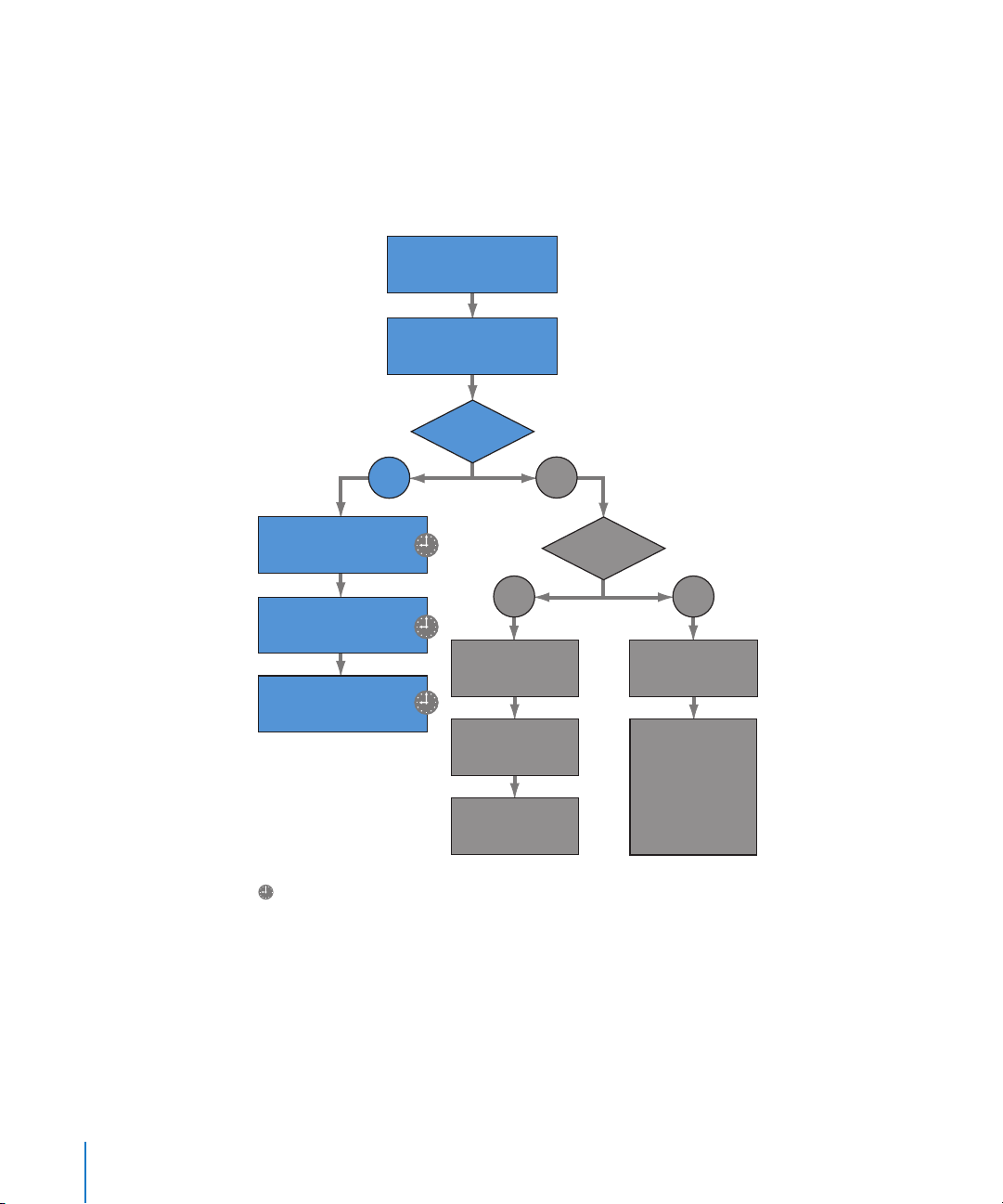

Offline and Online Editing

If you are working with a high-resolution 24p format, such as uncompressed HD video,

you may need to make lower-resolution copies of your footage to maximize your

computer’s disk space and processing power. In this case, there are four basic steps to

the editing process:

Production (generating the master video): Transfer film to or natively shoot on

uncompressed 24p HD video.

Offline edit: Convert footage to NTSC or PAL video (which is generally

lower-resolution than 24p) and edit it.

Project interchange: Export a Final Cut Pro project or an EDL containing your final

edit decisions.

Online edit: Replace low-resolution footage and create a full-resolution master.

For more information see “Editing 24p Video with Final Cut Pro” on page 201.

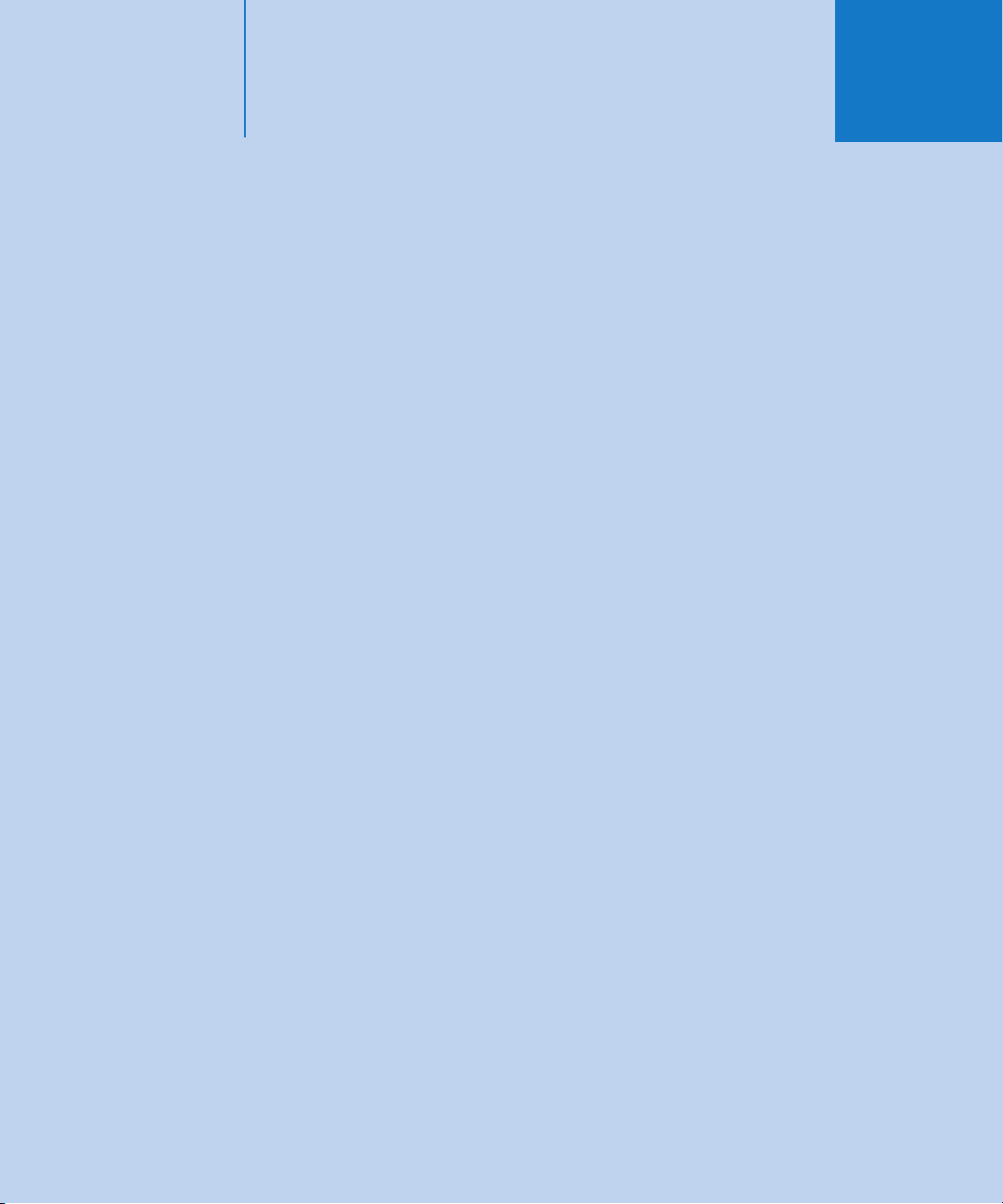

24p master

source

NTSC or

PAL video

Final Cut Pro with Cinema Tools

Capture

video

24p video

(offline edit)

Convert

to 24 fps

Edit

clips

Online edit

(24 fps)

24 fps

EDL

Edited 24p

master

About This Manual

This manual documents not only all aspects of using the Cinema Tools application, but

also all related functions within Final Cut Pro.

This manual is a fully hyperlinked PDF document enhanced with many features that

make locating information quick and easy.

The access page provides quick access to various features, including the index and

the Cinema Tools website.

A comprehensive bookmark list allows you to quickly choose what you want to see

and takes you there as soon as you click the link.

All cross-references in the text are linked. You can click any cross-reference and jump

immediately to that location. Then you can use the navigation bar’s Back button to

return to where you were before you clicked the cross-reference.

The table of contents and index are also linked. If you click an entry in either of these

sections, you jump directly to the section for that entry.

You can also use the search field to search the text for a specific word or phrase.

Preface An Introduction to Cinema Tools 11

Page 12

This manual provides background and conceptual information, as well as step-by-step

instructions for tasks and a glossary of terms. It is designed to provide the information

you need to get up to speed quickly so that you can take full advantage of the

powerful features of Cinema Tools.

If you want to begin with some introductory background information about editing

film traditionally as opposed to editing it using digital methods, see Appendix A,

“Background Basics,” on page 221.

To find out the details of how to use Cinema Tools, as well as some things to consider

in the planning of your project, see Part I, “Using Cinema Tools,” next.

If you’re interested in the 24p aspects of using both Final Cut Pro and Cinema Tools,

see Part II, “Working with 24p Video” on page 197.

Note: This manual is not intended to be a complete guide to the art of filmmaking.

Much of the film-specific information presented here is very general in nature and is

supplied to provide a context for the terminology used when describing

Cinema Tools functions.

Apple Websites

There are a variety of Apple websites that contain information to help you take full

advantage of the power of Cinema Tools and your Apple system.

Cinema Tools Website

For general information and updates, as well as the latest news about Cinema Tools,

go to:

http://www.apple.com/finalcutstudio/finalcutpro/cinematools.html

Apple Service and Support Website

For software updates and answers to the most frequently asked questions for all Apple

products, including Cinema Tools, go to:

http://www.apple.com/support

You’ll also have access to product specifications, reference documentation, and Apple

and third-party product technical articles.

For Cinema Tools support information, go to:

http://www.apple.com/support/cinematools

12 Preface An Introduction to Cinema Tools

Page 13

Other Apple Websites

Start at the Apple homepage to find the latest and greatest information about

Apple products:

http://www.apple.com

QuickTime is industry-standard technology for handling video, sound, animation,

graphics, text, music, and 360-degree virtual reality (VR) scenes. QuickTime provides a

high level of performance, compatibility, and quality for delivering digital video. Go to

the QuickTime website for information about the types of media supported, a tour of

the QuickTime interface, specifications, and more:

http://www.apple.com/quicktime

FireWire is one of the fastest peripheral standards ever developed, which makes it

great for use with multimedia peripherals, such as video camcorders and the latest

high-speed hard disk drives. Visit this website for information about FireWire

technology and available third-party FireWire products:

http://www.apple.com/firewire

For information about seminars, events, and third-party tools used in web publishing,

design and print, music and audio, desktop movies, digital imaging, and the media arts,

go to:

http://www.apple.com/pro

For resources, stories, and information about projects developed by users in education

using Apple software, including Cinema Tools, go to:

http://www.apple.com/education

Go to the Apple Store to buy software, hardware, and accessories direct from Apple

and to find special promotions and deals that include third-party hardware and

software products:

http://www.apple.com/store

Preface An Introduction to Cinema Tools 13

Page 14

Page 15

Part I: Using Cinema Tools

This section details using Cinema Tools while editing

film projects.

Chapter 1 Before You Begin Your Project

Chapter 2 The Cinema Tools Workflow

Chapter 3 The Cinema Tools Interface

Chapter 4 Creating and Using a Cinema Tools Database

Chapter 5 Capturing Source Clips and Connecting Them to the Database

Chapter 6 Preparing the Source Clips for Editing

I

Chapter 7 Editing with Final Cut Pro

Chapter 8 Generating Film Lists and Change Lists

Chapter 9 Export Considerations and Creating Audio EDLs

Chapter 10 Working with External EDLs, XML, and ALE Files

Page 16

Page 17

1 Before You Begin Your Project

1

Start planning your project early to ensure its success.

Successful film production requires thorough planning well before exposing the first

frame. Besides the normal preparations, additional issues must be considered when

you intend to edit the film digitally. These issues may affect the film you use, how you

record your sound, and other aspects of your production.

This chapter provides basic information about many of the issues you will face:

Which film to use

Choices for transferring the film to video

Frame rate issues between the film, your video standard, and your editing timebase

Sound issues such as which recorder and timecode to use and how to synchronize

the sound with the video

Issues with Final Cut Pro such as selecting a sequence timebase and using effects

Note: Much of this information is very general in nature and is not intended to serve as

a complete guide to filmmaking. The digital filmmaking industry changes rapidly, so

what you read here is not necessarily the final word.

Before You Shoot Your Film

Before you begin your project, make sure to discuss it with all parties involved in

the process:

Those providing equipment or supplies used during the production

Those involved in the actual production

The facility that will develop your film, create workprints, and create the release print

The video transfer facility

The editor using Cinema Tools and Final Cut Pro (if it is not you)

The negative cutter

The audio post-production facility

17

Page 18

These are people who are experts in their fields. They can provide invaluable

information that can make the difference between a smooth, successful project and

one that seems constantly to run into obstacles.

Be Careful How You Save Money

There are a number of times throughout the film production process when you will

get to choose between “doing it right” and “doing it well enough.” Often your budget

or a lack of time drives the decision. Make sure you thoroughly understand your

workflow choices before making decisions that could end up costing you more, both

in time and money, in the long run. Problems based on choices made early in the

process—for example, deciding not to have a telecine log made—could take you by

surprise later.

Having professional facilities handle the tasks they specialize in, especially when you

are new to the process, is highly recommended. You may actually save money by

spending a little for tasks that you could do yourself, such as using an audio

post-production facility.

Also, do not underestimate the importance of using the cut list to conform a

workprint before conforming the negative. While creating and editing a workprint

adds costs to the project, incorrectly conforming the original camera negative will

cause irreparable harm to your film.

Which Film to Use?

One of the first steps in any film production is choosing the film format to use.

Cinema Tools requirements must be taken into account when making this choice.

Cinema Tools supports 4-perf 35mm, 3-perf 35mm, and 16mm-20 film formats. See

“Film Basics” on page 221 for details about these formats.

Your budget will likely determine which format you use. While it is recommended that

you use the same film format throughout your production, Cinema Tools does not

require it. Each database record has its own film format setting.

18 Part I Using Cinema Tools

Page 19

I

Transferring Film to Video

In order to digitally edit your film, you need to transfer it to video so that it can be

captured by the computer. There are a few ways to do this, but an overriding

requirement is that there be a reliable way to match the film’s key numbers to the

edited video’s timecode. This relationship allows Cinema Tools to accurately calculate

specific key numbers based on each edit’s In and Out point timecode values.

You also need to make decisions regarding film and video frame rates used during the

transfer. These affect the editing timebase and impact the accuracy of the cut list that

Cinema Tools generates.

Telecines

By far the most common method of transferring film to video is to use a telecine.

Telecines are devices that scan each film frame onto a charge-coupled device (CCD) to

convert the film frames into video frames. While a telecine provides an excellent

picture, for the purposes of Cinema Tools the more important benefit is that it results in

a locked relationship between the film and video, with no drifting between them.

Telecines are typically gentler on the film and offer sophisticated color correction and

operational control as compared to film chains, described below. Another advantage is

that telecines can create video from the original camera negative—most other

methods require you to create a film positive (workprint) first. (While from a budget

viewpoint it may be a benefit not to create a workprint, they are generally created

anyway since they provide the best way to see the footage on a large screen and spot

any issues that might impact which takes you use. Even more importantly, they allow

you to test the cut list before working on the negative.)

In addition to providing a high-quality transfer, most modern telecines read the key

numbers from the film and can access the video recorder’s timecode generator,

burning in these numbers on the video output. An additional benefit of the telecine

transfer method is its ability to provide synchronized audio along with the video

output. It can control the audio source and burn in the audio timecode along with the

video timecode and the key numbers.

Chapter 1 Before You Begin Your Project 19

Page 20

But What If You Want a Clean Master?

If you plan to conform the original camera negative, the presence of burned-in

timecode and key numbers on the video clips you edit in Final Cut Pro may not be a

problem, especially if you are working with a highly compressed video format.

The burned-in numbers can be a problem, however, if you intend to use the edited

video for screenings or for broadcast. As valuable as they are to the editor, the

burned-in numbers can be distracting when watching an edited project. There are

two common methods you can use to minimize this problem:

Letterbox the video during capture using a 2:35 aspect ratio so that there is

enough room below the video to show the numbers.

Flash the burn-in information on the first frame only. While not quite as useful as a

continuous burn-in, this does provide the editor with the ability to ensure that the

relationship of the edge code to the timecode is correct.

In most cases, telecines produce a log file that can provide the basis for the Cinema Tools

database. This allows you to automate capturing the video into the computer.

Increasingly, telecine facilities can also capture the video clips for you, providing the

clips on a DVD disc or FireWire drive, along with the telecine log and videotapes.

Transfer Techniques That Are Not Recommended

There are a couple of transfer techniques that are worth mentioning just to point out

why you should not use them.

Film Chains

You should avoid using a film chain if at all possible. Film chains are relatively old

technology, as compared to telecines. A film chain is basically a film projector linked to

a video camera. Film chains typically do not support features such as reading the key

numbers or controlling video recorders, and they cannot create a positive video from a

film negative. You must create a workprint to use a film chain.

Using a film chain is usually less expensive than using a telecine, although the cost of

creating a workprint partly offsets the lower cost. The biggest challenge is being able

to define the relationship between the film’s key numbers and the video timecode. This

is usually accomplished with hole punches (or some other distinct frame marker) at

known film frames.

Important: Older film chains may not synchronize the film projector to the video

recorder, potentially causing the film-to-video relationship to drift.

20 Part I Using Cinema Tools

Page 21

I

Recording a Projected Image with a Camcorder

Because of the greatly increased chances for error and the additional time you have to

spend tracking key numbers, this method of transfer is strongly discouraged and

should not be considered.

Projecting your film and recording the results using a video camcorder is a method

that, while relatively inexpensive, almost guarantees errors in the final negative cutting.

Telecines and film chains are usually able to synchronize the film and video devices,

ensuring a consistent transfer at whatever frame rates you choose. The projector’s and

video camcorder’s frame rates may be close to ideal but will drift apart throughout the

transfer, making it impossible to ensure a reliable relationship between the film’s key

numbers and the video timecode. You will have to spend extra time going over the cut

list to ensure the proper film frames are being used. Additionally, there may be

substantial flicker in the video output, making it difficult to see some frames and

determine which to edit on.

Since the video is not actually used for anything except determining edit points, its

quality doesn’t matter too much. As with film chains, you have to create a workprint to

project. Being able to proof your cut list before the original camera negative is worked

on is very important with this type of transfer.

How Much Should You Transfer?

Deciding how much of your film to transfer to video depends on a number of issues,

the biggest one probably being cost. The amount of time the telecine operator

spends on the transfer determines the cost. Whether it is more efficient to transfer

entire rolls of film (a “camera-roll” transfer), including bad takes and scenes that won’t

be used, or to spend time locating specific takes and transferring only the useful

ones (a “scene-and-take” transfer) needs to be determined before starting.

Camera-Roll Transfers

Cinema Tools uses a database to track the relationship between the film key numbers

and the video and audio timecode numbers. The database is designed to have a record

for each camera take, but this is not required. If you transfer an entire roll of film

continuously to videotape, Cinema Tools needs only one record to establish the

relationship between the key numbers and the video timecode. All edits using any

portion of that single large clip can be accurately matched to the original camera

negative’s key numbers. A drawback to this transfer method is the large file sizes,

especially if significant chunks of footage will not be used.

Chapter 1 Before You Begin Your Project 21

Page 22

Additionally, because of the way it is recorded, audio is difficult to synchronize at the

telecine during a camera-roll transfer. During a production, the audio recorder

typically starts recording before film starts rolling and ends after filming has stopped.

You also will often shoot some film without sound (known as MOS shots). This means

you cannot establish audio sync at the start of the film roll and expect it to be

maintained throughout the roll. Instead, each clip needs to be synced individually.

The Cinema Tools database includes provisions for tracking the original production

sound reels and timecode.

Once captured, a single large clip can be broken into smaller ones, allowing you to

delete the excess video. Even with multiple clips, it is possible for Cinema Tools to

generate a complete cut list with only one database record. Another approach is to

manually add additional records for each clip, allowing you to take advantage of the

extensive database capabilities of Cinema Tools. See “Creating the Cinema Tools

Database” on page 36 for a detailed discussion of these choices.

Scene-and-Take Transfers

Scene-and-take transfers are a bit more expensive than camera-roll transfers, but they

offer significant advantages:

Scene-and-take transfers make it easier to synchronize audio during the transfer.

Since the telecine log contains one record per take, it establishes a solid database

when imported into Cinema Tools.

With an established database, Cinema Tools can export a batch capture list. With this

list (and appropriate device control), Final Cut Pro can capture and digitize the

appropriate takes with minimum effort on your part.

Maintaining an accurate film log and using a timecode slate can help speed the

transfer process and reduce costs.

Frame Rate Basics

When transferring film to video, you need to take into account the differences in film

and video frame rates. Film is shot almost exclusively at 24 frames per second (fps) or

23.98 fps, although 25 fps is often used when the final project is to be delivered as PAL

video. Video can have a 29.97 fps rate (NTSC), a 25 fps rate (PAL), or either a 24 fps or

23.98 fps rate (24p), depending on your video standard.

The frame rate of your video (whether you sync the audio during the telecine transfer or

not) and the frame rate you want to edit at can determine what you need to do to

prepare your clips for editing. You may find it useful to read “Determining How to Prepare

Source Clips for Editing” on page 123 before you make any decisions about frame rates.

22 Part I Using Cinema Tools

Page 23

ABCD

AAB B B C C DDD

Field1Field2Field1Field

2

Field1Field

2

Field1Field

2

Field1Field

2

I

Working with NTSC Video

The original frame rate of NTSC video was exactly 30 fps. When color was added, the

rate had to be changed slightly, to the rate of 29.97 fps. The field rate of NTSC video is

59.94. NTSC video is often referred to as having a frame rate of 30, and while the

difference is not large, it cannot be ignored when transferring film to video (because of

its impact on audio synchronization, explained in “Synchronizing the Audio with the

Video” on page 31).

Another issue is how to distribute film’s 24 fps among NTSC video’s 29.97 fps. You have

two options:

Perform a 3:2 pull-down

Run the film at 29.97 fps

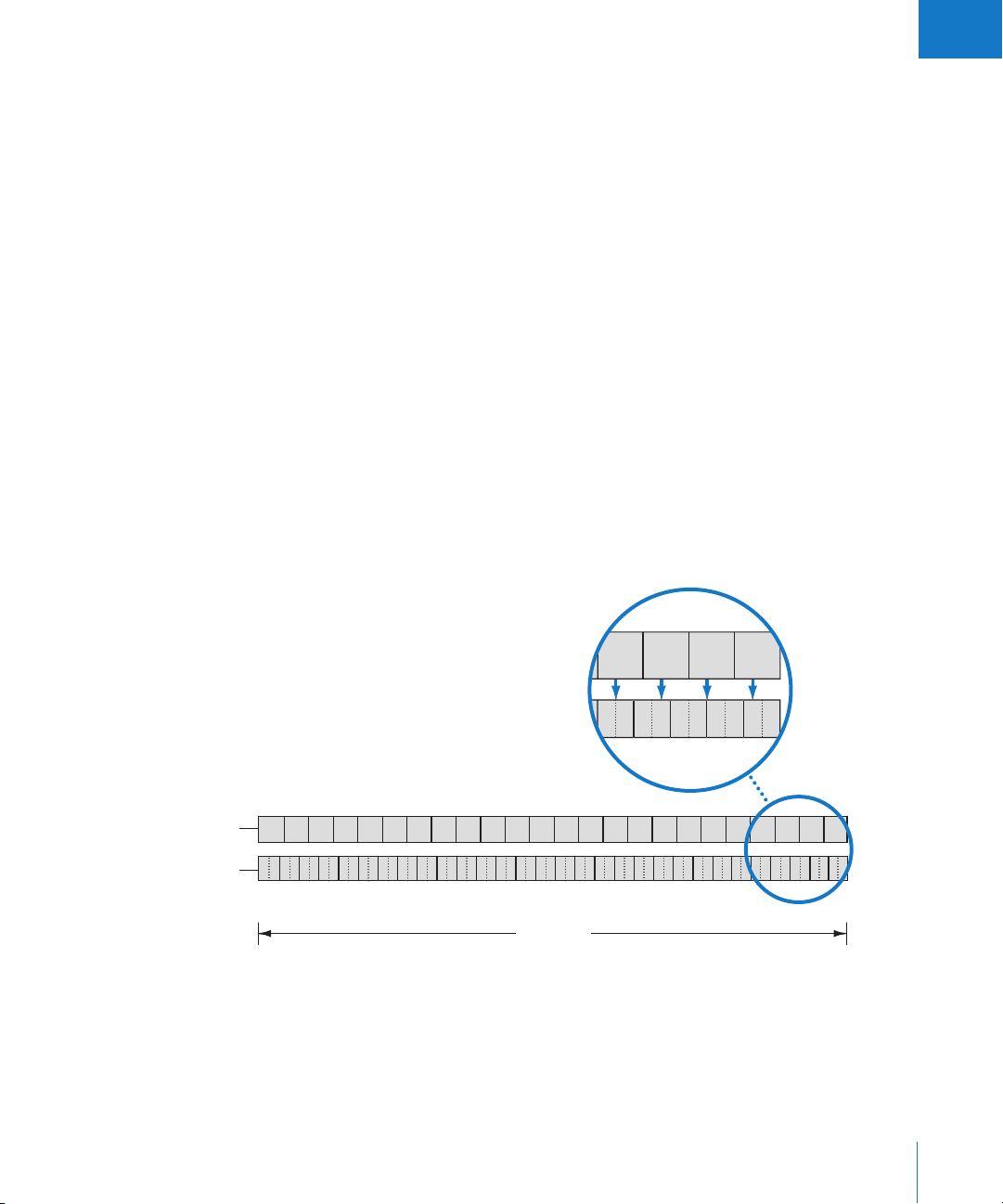

Performing a 3:2 Pull-Down

The most common approach to distributing film’s 24 fps among NTSC video’s 29.97 fps

is to perform a 3:2 pull-down (also known as a 2:3:2:3 pull-down). If you alternate

recording two fields of one film frame and then three fields of the next, the 24 frames

in 1 second of film end up filling the 30 frames in 1 second of video.

Note: The actual NTSC video frame rate is 29.97 fps. The film frame rate is modified to

23.98 fps in order to create the 3:2 pattern.

Before

(23.98 fps)

After

(29.97 fps)

3:2 Pull-Down

ABCDA DABCDABCDABCDABCD

AABBBCCDDDAABBBCCDDDAABB CCDDDAAB BBCCDDDABABBCCDDBD

BC

ABABBCCDDD

One second

As shown above, the 3:2 pattern (actually a 2:3:2:3 pattern since frame A is recorded to

two fields followed by frame B recorded to three fields) repeats after four film frames.

Virtually all high-end commercials, movies, and non-live television shows use this

process prior to being broadcast.

Chapter 1 Before You Begin Your Project 23

Page 24

Note that there is not a one-to-one correspondence between film frames and video

frames after this pull-down occurs. The duration of a video frame is four-fifths the

duration of a film frame. Because of this discrepancy, if you tried to match a specific

number of whole video frames to some number of whole film frames, the durations

would seldom match perfectly. In order to maintain overall synchronization, there is

usually some fraction of a film frame that must be either added to or subtracted from

the duration of the next edit. This means that in the cut list, Cinema Tools occasionally

has to add or subtract a film frame from the end of a cut in order to maintain

synchronization. For this reason, if you edit 3:2 pull-down video, the Cinema Tools cut

list is only accurate to within +/– 1 frame on each edit.

This accuracy issue is easily resolved by using the Reverse Telecine feature (or third-party

hardware or software) to remove the extra fields and restore the film’s original 24 fps rate

before you begin editing digitally, providing a one-to-one relationship between the

video and film frames. Setting the Final Cut Pro editing timebase in the Sequence Preset

Editor to 24 fps (or 23.98 fps—see “Synchronizing the Audio with the Video” on page 31)

allows you to edit the video and generate a very accurate cut list. See “Determining How

to Prepare Source Clips for Editing” on page 123 for more information about issues

related to these options.

What’s an A Frame?

You will see and hear references to “A” frames whenever you are involved with

3:2 pull-down video. As the previous illustration shows, the A frame is the only one

that has all its fields contained within one video frame. The others (B, C, and D

frames) all appear in two video frames. Since the A frame is the start of the video

five-frame pattern, it is highly desirable to have one as the first frame in all video

clips. It’s common practice to have A frames at non-drop frame timecode numbers

ending in “5” and “0.”

See “About A Frames” on page 134 for more information.

Running the Film at 29.97 fps

Another NTSC video transfer option is to run the film at 29.97 fps. While this leads to a

one-to-one relationship between each video and film frame, the action in the film is

sped up by 25 percent. Because of audio synchronization considerations, this method is

not often used or recommended.

24 Part I Using Cinema Tools

Page 25

I

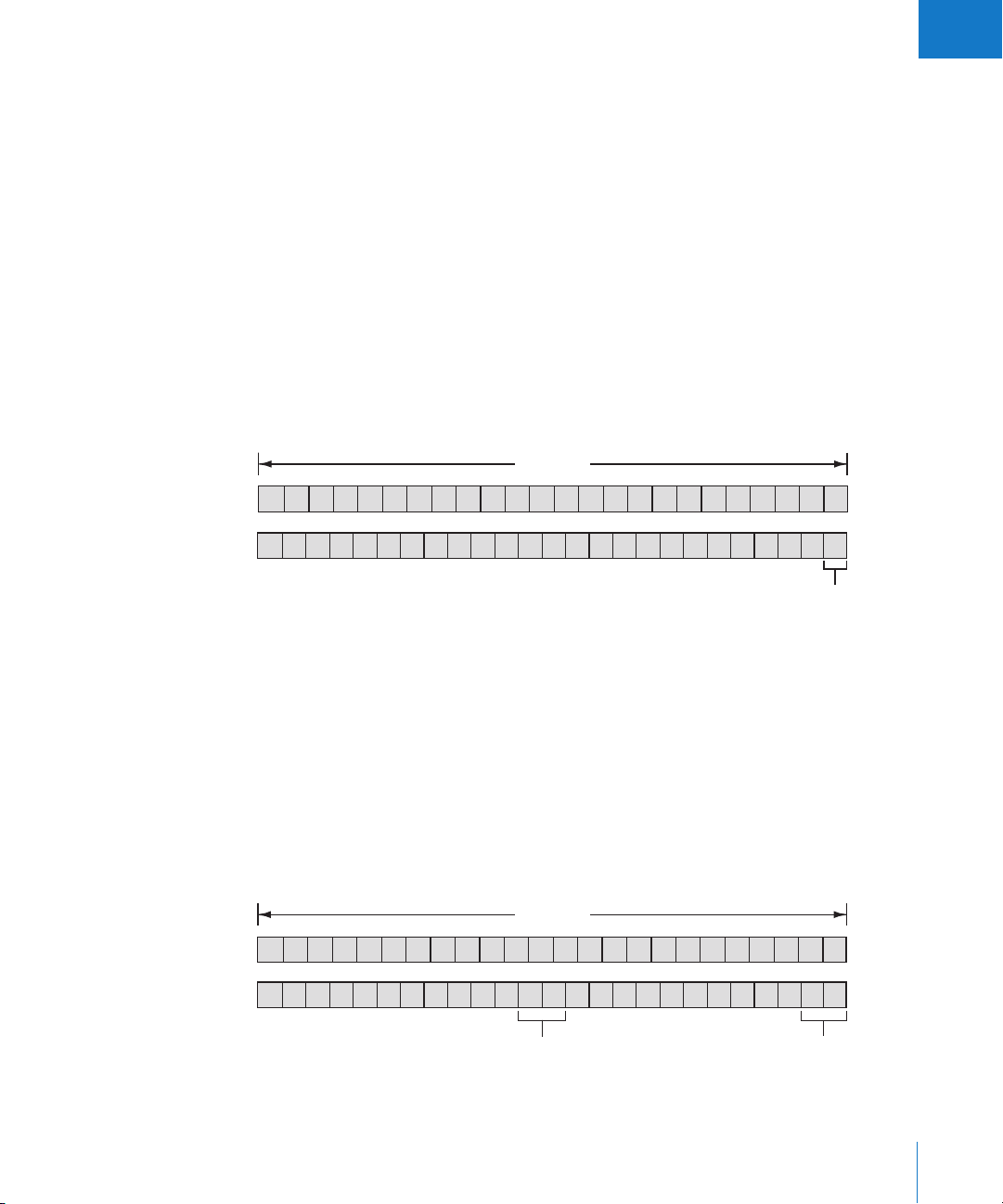

Working with PAL Video

The PAL video frame rate is exactly 25 fps. There are two methods used when

transferring film to PAL: running the film at 25 fps (referred to as the 24 @ 25 method),

and adding two extra fields per second (similar to NTSC’s 3:2 pull-down, referred to as

the 24 & 1 method, or the 24 @ 25 pull-down method).

24 @ 25 Method

Running the film at 25 fps sets up a one-to-one relationship between the film and

video frames. The drawback is that the action in the film is sped up by 4 percent, and

the audio will need an identical speed increase to maintain synchronization. To take

advantage of the wide variety of 25 fps video equipment available, you can choose to

edit with the action 4 percent faster. Another option is to use the Cinema Tools

Conform feature to change the clip’s timebase to 24 fps, correcting the speed. The

video can then be edited with Final Cut Pro as long as the sequences using it have a

24 fps timebase.

One second

12345 89101112131415161718192021222324

1

1

22334455667788991010111112121313141415151616171718

67

18 19 20 21 22 23 24

19 20 21 22 23 24

First frame of next second

24 fps

1

25 fps

1

Note: Final Cut Pro includes an Easy Setup and sequence preset with “24 @ 25” in

their names, as well as a timecode format named “24 @ 25.” These are all intended to

be used with clips that originated as PAL 25 fps video but have been conformed to

24 fps video. See “Working with 25 fps Video Conformed to 24 fps” on page 144 for

more information.

24 &1 Method

Adding two extra video fields per second (also known as the 24 @ 25 pull-down method

in Final Cut Pro) has the advantage of maintaining the original film speed, at the expense

of losing the one-to-one film-to-video frame relationship. This method records an extra

video field every twelfth film frame.

One second

1 2 3 4 5 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24

1122334455667788991010111112

6 7

12 13 14 15 1 6 17 18 19 2 0 21 2 2 2 3

12

13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24

Repeated field Repeated field

24 fps

24

25 fps

24

Chapter 1 Before You Begin Your Project 25

Page 26

Working with 24p Video

With its frame rate and progressive scanning, 24p video is well suited for use with

telecine transfers. It uses the same frame rate as film, providing a one-to-one relationship

between the film and video frames without requiring a frame rate conversion.

Your Final Cut Pro system needs to be equipped with specialized hardware to capture

24p video, either as compressed or uncompressed clips. Alternatively, some DV cameras,

such as the Panasonic AG-DVX100 camcorder, can shoot 24p video and use the 2:3:3:2

pull-down method to record it to tape as 29.97 fps (the NTSC standard). Using

Final Cut Pro and Cinema Tools, you can capture this video and remove the 2:3:3:2

pull-down so that you can edit it at 24 fps. See “Adding and Removing Pull-Down in

24p Clips” on page 208 for more information.

Note: When used as part of an NTSC system, the 24p videotape recorder’s (VTR’s) frame

rate is actually 23.976 fps (referred to as 23.98 fps) to be compatible with the NTSC

29.97 fps rate.

Timecode Considerations

There are several general issues related to timecode that you should be aware of. If

you’re using NTSC video, you can also choose between two timecode formats.

General Timecode Tips

When using video or audio equipment that allows you to define the timecode setting,

it is recommended that you set the “hours” part of the timecode to match the tape’s

reel number. This makes it much easier to recognize which reel a clip originated from. It

is also best to avoid “crossing midnight” on a tape. This happens when the timecode

turns over from 23:59:59:29 to 00:00:00:00 while the tape is playing.

You have the option to use record run or free run timecode during the production:

Record run timecode: The timecode generator pauses each time you stop recording.

Your tape ends up with continuous timecode, since each time you start recording it

picks up from where it left off.

Free run timecode: The timecode generator runs continuously. Your tape ends up

with a timecode break each time you start recording.

To avoid potential issues while capturing clips, it is strongly suggested that you use the

record run method, which avoids noncontinuous timecode within a tape.

Whenever a tape has noncontinuous timecode (with jumps in the numbers between

takes), make sure to allow enough time (handles) for the pre-roll and post-roll required

during the capture process when logging your clips. See the Final Cut Pro documentation

for additional information about timecode usage.

26 Part I Using Cinema Tools

Page 27

I

About NTSC Timecode

Normal NTSC timecode (referred to as non-drop frame timecode) works as you would

expect—each frame uses the next available number. There are 30 frames per second,

60 seconds per minute, and 60 minutes per hour. Since NTSC’s actual frame rate of

29.97 fps is a little less than 30 fps, non-drop frame timecode ends up being slow

(by 3 seconds and 18 frames per hour) when compared to actual elapsed time.

To compensate for this, drop frame timecode skips ahead by two frames each minute,

except those minutes ending in “0.” (Note that it is only the numbers that are

skipped—not the actual video frames.) This correction makes the timecode accurate

with respect to real time, but adds confusion to the process of digital film editing.

With non-drop frame timecode, once you find an A frame, you know that the frame

at that frame number and the one five away from it will always be A frames. For

example, if you find an A frame at 1:23:14:15, you know that all frames ending in “5”

and “0” will be A frames. With drop frame timecode, you are not able to easily

establish this sort of relationship.

Note: It is standard practice to have A frames at non-drop frame timecode numbers

ending in “5” and “0.”

It is highly recommended that you use non-drop frame timecode for both the video

and audio in all film editing projects, even though both Cinema Tools and Final Cut Pro

are able to use either type. Whichever you use, make sure to use the same for both the

video and audio tapes.

Note: PAL timecode does not have this issue—it runs at a true 25 fps.

What Happens to the Timecode After Using Reverse Telecine?

The Reverse Telecine feature (used to change 29.97 fps video to 23.98 fps video) directly

affects the timecode of the video frames. Because Cinema Tools must generate new

23.98 fps timecode for the frames (based on the original timecode), you may see a

difference between the burned-in timecode numbers and the numbers shown in

Final Cut Pro. Though the timecode discrepancies between the window burn and

Final Cut Pro timecode may be confusing, Cinema Tools tracks the new timecode of the

23.98 fps video and is able to match it back to its original NTSC or PAL values, and thus

back to the film’s key numbers.

Note: The Reverse Telecine feature is most often used to convert the NTSC video to

23.98 fps to match the audio timecode, but it can also convert the video to 24 fps.

Chapter 1 Before You Begin Your Project 27

Page 28

This is what happens to the timecode: reverse telecine removes six frames per second,

so the timecode numbers continue to match at the beginning of each second. This

means that a clip that lasts for 38 seconds when played at its NTSC rate of 29.97 fps will

still last for 38 seconds when played at the reverse-telecined rate of 23.98 fps.

Clip start

2

1:0

1:01

0

1:0

1:03

1

1:0

2

1:00 1:11

1:0

1:0 6

1:04

1:05 1:16

1:0 7

1:0

3

1:0

4

1:0

5

1:0

1:10

1:09

6

1:0

7

1:0

8

Reverse-telecined video frames (23.98 fps)

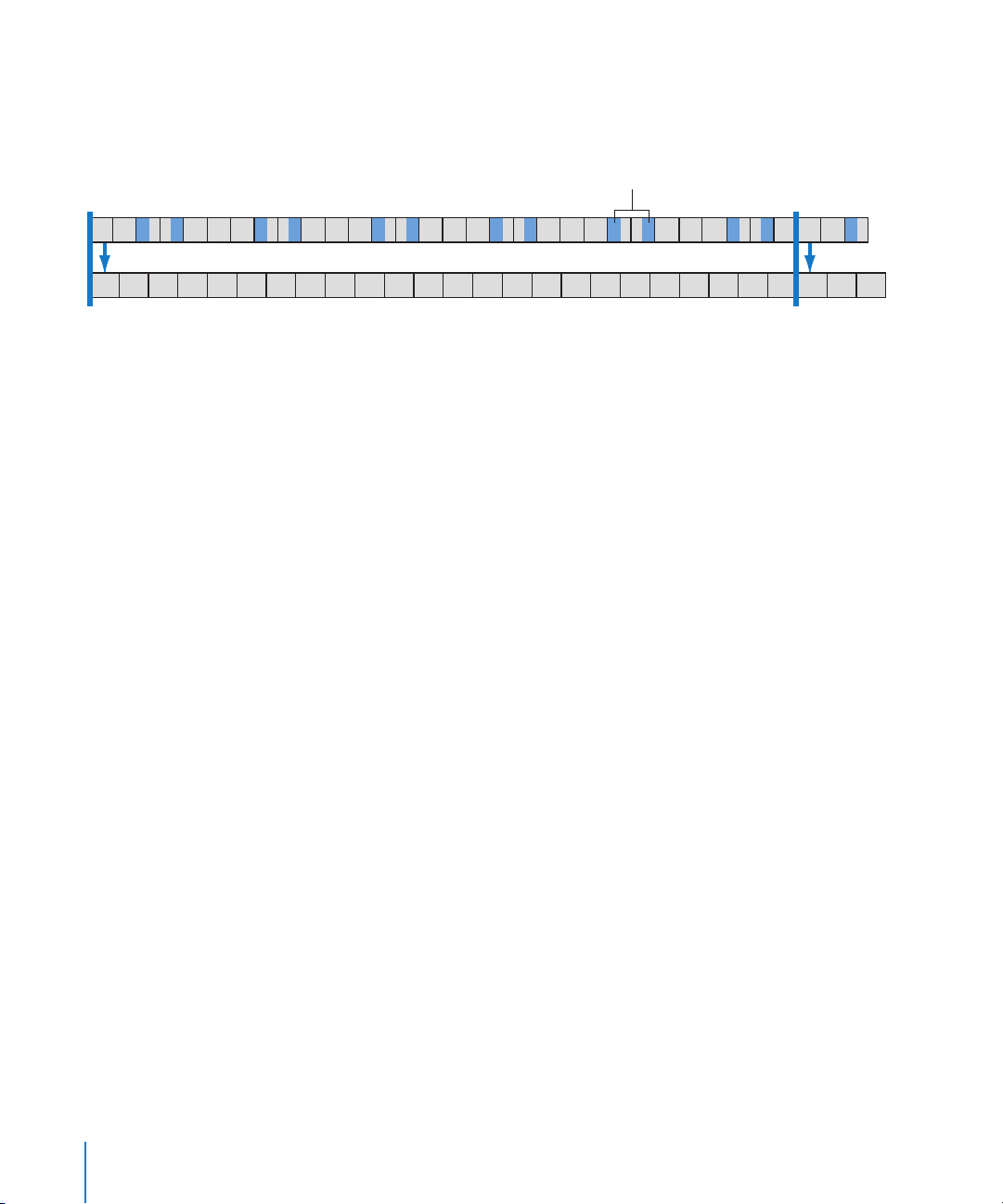

In the above illustration, the blue NTSC fields represent those that are removed during

the reverse telecine process on a clip using traditional 3:2 pull-down. (See “Adding and

Removing Pull-Down in 24p Clips” on page 208 for information about 2:3:3:2 pull-down.)

The window burn NTSC timecode will be different from what Final Cut Pro shows for all

frames except the first one of each second, regardless of the clip’s length.

What Happens to the Timecode After Using Conform?

There are three common situations you would use the Conform feature for:

Converting PAL 25 fps video to 24 fps: The timecode is not changed, which ensures

that an EDL exported after the clips are edited will accurately refer to the original PAL

timecode. The drawback is that the timecode, at 25 fps, no longer accurately

represents the true passage of time when played at 24 fps since each frame is

displayed for a slightly longer time. See “Working with 25 fps Video Conformed to 24

fps” on page 144 for more information.

Conforming 29.97 fps video to 29.97 fps: The timecode is not changed. This process is

used to correct issues in a QuickTime file prior to using the Reverse Telecine feature.

See Appendix C, “Solutions to Common Problems and Customer Support,” on

page 237 for more information.

Converting NTSC 29.97 fps video to 23.98 fps: The timecode is altered, with a number

skipped every five frames. This conform situation is rarely used.

NTSC video frames (29.97 fps)

1:12

1:13

1:15

1:0

1:14

1:1

1:1

1

0

9

1:1

1:17

2

1:1

3

1:1

One secondDiscarded fields

1:181:08

1:19

4

1:1

5

1:20

1:1

6

1:21

1:1

1:2

2

7

1:1

1:23

1:2 5

1:24

1:26

1:201:2

1:1

9

8

1:2 7

1

1:221:2

1: 29

1:2 8

3 2:00 2:01 2:02

2:00 2:01 2:02

See “Using the Conform Feature” on page 125 for more information.

28 Part I Using Cinema Tools

Page 29

I

Sound Considerations

Since the sound for a film is recorded separately on an audio recorder, there are a

number of issues that you must be aware of and plan for:

What type of audio recorder to use

What timecode format to use

How to mix the final audio

How to synchronize the audio with the video

Choosing an Audio Recorder

When choosing an audio recorder, you have several options: an analog tape recorder

(typically a Nagra), a digital tape recorder (DAT—Digital Audio Tape), or a digital disc

recorder. Whether analog or digital, make sure the recorder has timecode capability.

Choosing an Audio Timecode Format

Unlike video or film, which must be structured with a specific frame rate, audio is linear

with no physical frame boundaries. Adding timecode to audio is simply a way to

identify points in time, making it easier to match the audio to video or film frames.

During the shoot, you have the choice of which audio timecode standard to use (typically

30 fps, 29.97 fps, 25 fps, 24 fps, or 23.98 fps). You also have the choice, with 30 fps and

29.97 fps, of using drop frame or non-drop frame timecode. For NTSC transfers, it is highly

recommended that you use non-drop frame timecode for both the video and audio

(although Cinema Tools can work with either). See “About NTSC Timecode” on page 27

for more information about drop frame and non-drop frame timecode.

A consideration for the audio timecode setting is how the final audio will be mixed:

If the final mix is to be completed using Final Cut Pro: The setting needs to match the

Final Cut Pro Editing Timebase setting in the Sequence Preset Editor.

If the final mix is to be completed at an audio post-production facility: The timecode

needs to be compatible with the facility’s equipment.

Note: Make sure to consult with the facility and make this determination before the

shoot begins.

In general, if you are syncing the audio during the telecine transfer, the timecode

should match the video standard (29.97 fps for NTSC, 25 fps for PAL, or 24 fps for 24p).

Check with your sound editor before you shoot to make sure the editor is comfortable

with your choice.

Chapter 1 Before You Begin Your Project 29

Page 30

Mixing the Final Audio

The way you mix the final audio depends on how complicated the soundtrack is

(multiple tracks, sound effects, and overdubbing all add to its complexity) and your

budget. You can either finish the audio with Final Cut Pro or have it finished at a

post-production facility.

Finishing the Audio with Final Cut Pro

If you capture high-quality audio clips, you can finish the audio for your project with

Final Cut Pro, which includes sophisticated sound editing tools. Keep in mind, however,

that good audio is crucial to a good film, and a decision not to put your audio in the

hands of an audio post-production facility familiar with the issues of creating audio for

film might lead to disappointing results.

You can export the audio from Final Cut Pro as an Open Media Framework (OMF) file

for use at an audio post-production facility. An exported OMF file contains not only the

information about audio In and Out points, but also the audio itself. This means that,

for example, any sound effects clips you may have added are included. When you use

an OMF file, the recording quality must be as high as possible, as this is what the

audience will hear. Make sure to use a good capture device and observe proper

recording levels.

Exporting Audio EDLs

Another approach is to use lower-quality clips in Final Cut Pro and then export an

audio Edit Decision List (EDL) for use at an audio post-production facility. There they

can capture high-quality versions of the audio clips straight from the original

production sound source and edit them based on the audio EDL. For this to work, the

timecode and reel numbers of the original audio tapes must be kept track of and used

to create the audio EDL.

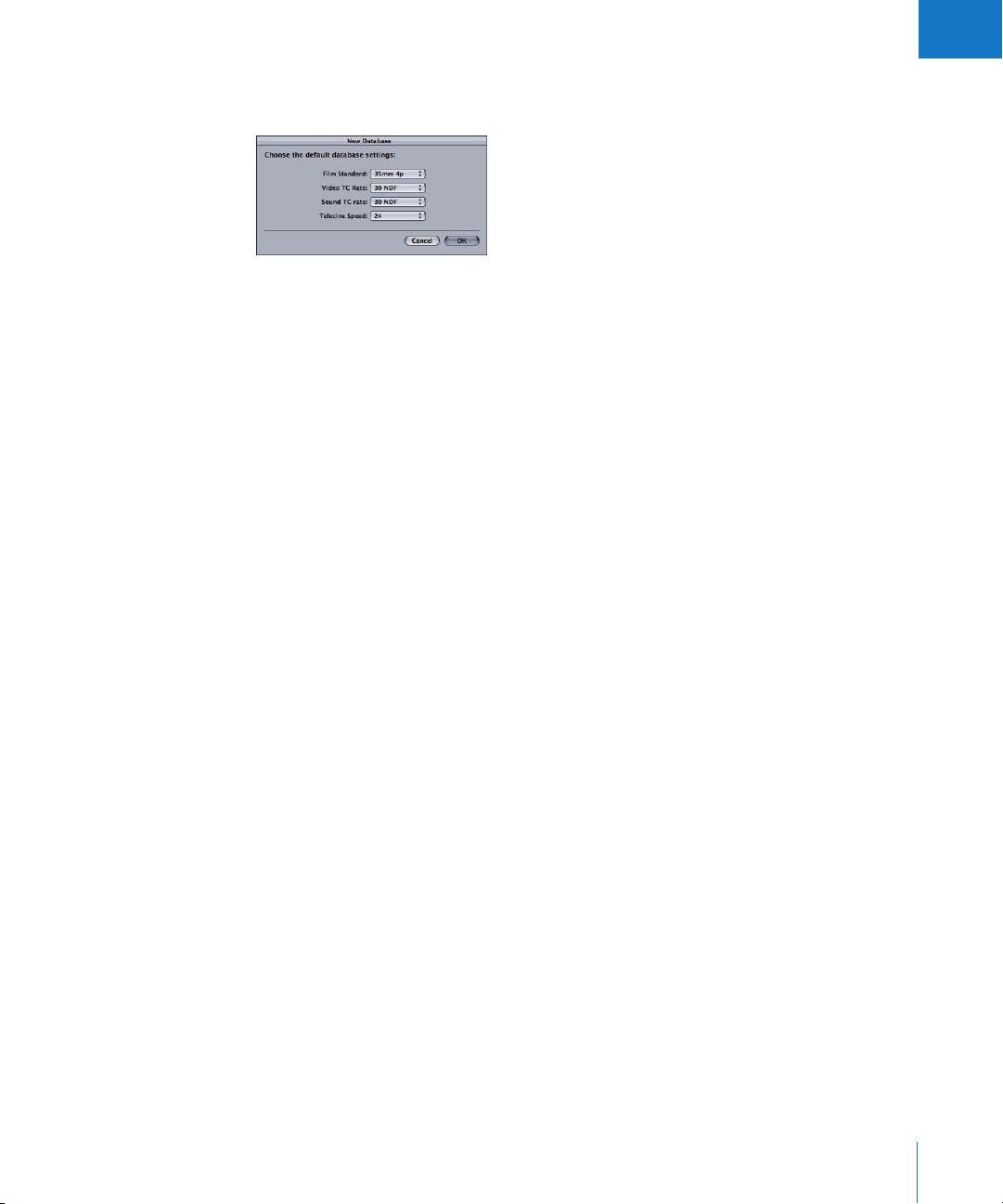

Audio clips captured as part of video clips do not retain their original timecode and

reel numbers, and the Final Cut Pro EDL cannot be used by an audio post-production

facility. This is most common with clips created from scene-and-take transfers, where

the audio is synchronized to the film and recorded onto the videotape, losing the

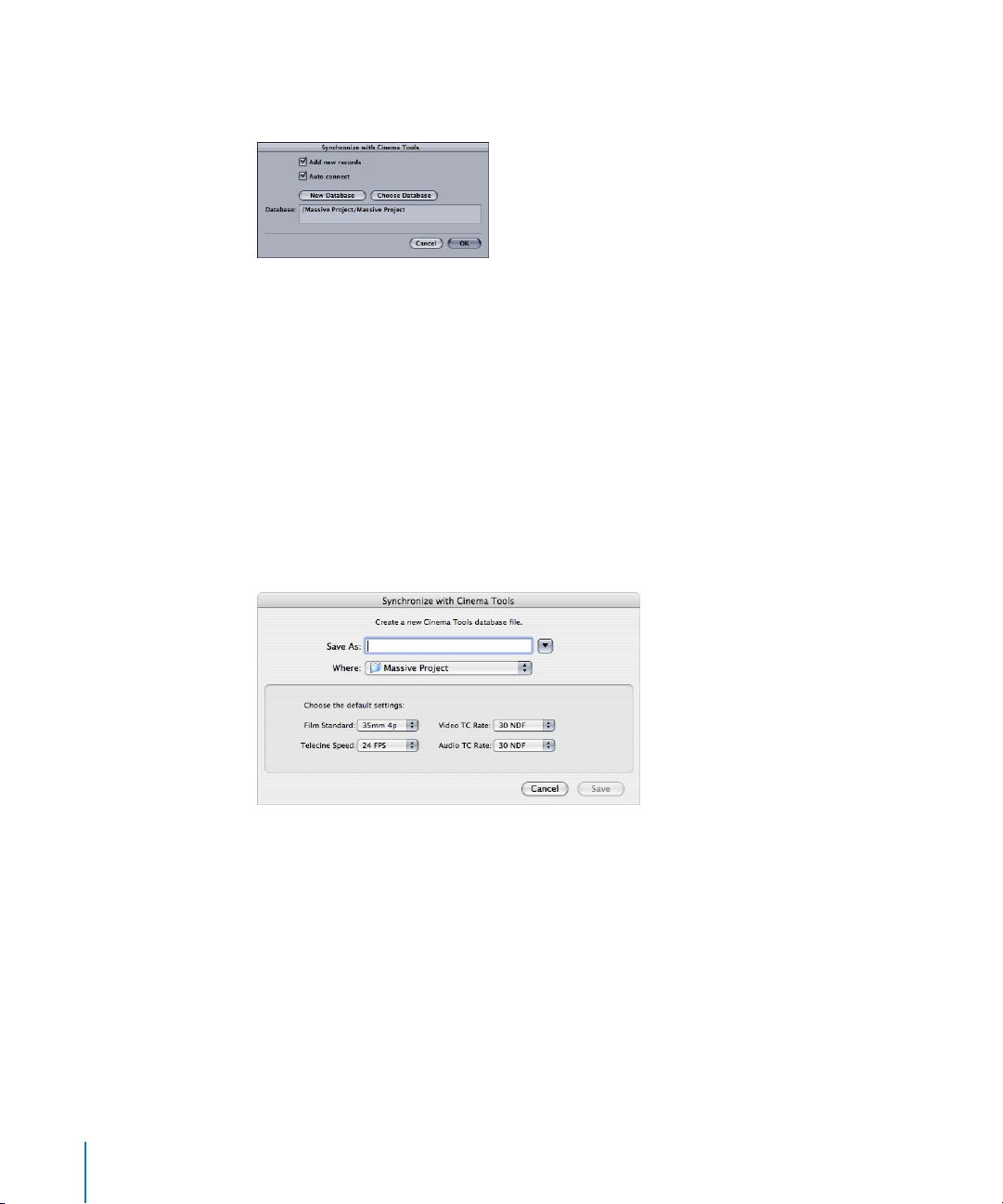

original audio timecode. But because the telecine log from the transfer generally

contains timecode and reel number information for both the video and audio,

importing this log into the Cinema Tools database allows the database to track audio

usage, and you can export an audio EDL from Cinema Tools once you finish editing.

See “Exporting an Audio EDL” on page 183 for details about the process.

30 Part I Using Cinema Tools

Page 31

I

Synchronizing the Audio with the Video

The production sound for a film is recorded separately on an audio recorder; this is known

as dual (or double) system recording. Synchronizing the sound with the film and video,

ensuring good lip-sync, is a critical step in making a movie. How you synchronize depends

on the equipment used and when syncing is done. There are also considerations related to

your video standard, how the telecine transfer was done, and the timecode used that

directly impact the process.

There are three times when audio synchronization is important:

During the telecine transfer

During editing

While creating the release print

Different strategies may be required to maintain sync at each of these times. Make sure

you have planned accordingly.

Synchronization Basics

Synchronizing the audio with the video image can be fairly easy as long as some care

was taken during the shoot. There are two aspects to synchronizing your audio:

establishing sync at a particular point in each clip, and playing the audio at the correct

speed so that it stays in sync.

While shooting, you must provide visible and audible cues to sync on. The most

common method is to use a clapper board (also called a slate or sticks) at the

beginning of each take. Even better, you can use a timecode slate that displays the

audio recorder’s timecode. To sync the audio with the video, position the video at the

first frame where the slate is closed, then locate the sound (or timecode) of the related

audio. Note that production requirements occasionally require the slate to occur at the

end of the take, generally with the slate held upside down.

Since the film is often either slightly sped up or slowed down during the telecine

transfer, the audio must also have its speed changed. If the audio is being synced

during the transfer, the speed change is handled there. If the audio is being synced to

the videotape after the transfer, the speed change must happen then.

Chapter 1 Before You Begin Your Project 31

Page 32

Synchronizing During the Telecine Transfer

During the shoot, you typically start the audio recorder a little before the camera rolls and

stop it a little after the camera stops. Since you end up recording more audio than film,

you cannot play the audio tape and the film through several takes and have them stay in

sync. If you want the telecine transfer to record synchronized audio on the videotape, you

must either use the scene-and-take transfer method, synchronizing each take on its own,

or create a synced audio reel before performing a camera-roll transfer.

A large benefit to synchronizing during the telecine transfer, aside from having

videotapes with synchronized audio ready to be captured, is that the telecine log usually

includes the audio timecode and reel number information. Importing the log into

Cinema Tools makes it possible to export an audio EDL so that an audio post-production

facility can recapture the audio clips at a higher quality later, if needed.

NTSC Transfers

When transferring film to NTSC video, it is always necessary to run the film 0.1 percent

slower than 24 fps (23.976 fps, typically referred to as 23.98 fps) to compensate for NTSC

video’s actual frame rate of 29.97 fps (instead of an ideal 30 fps). Since the film has been

slowed down, audio too must be slowed to maintain sync.

PAL Transfers

PAL transfers using the 24 @ 25 method (speeding up the film to 25 fps) require that

the audio also be sped up if you are syncing the audio during the telecine transfer or if

you intend to edit the video at this rate.

If you are transferring the film to video using the 24 & 1 method (recording an extra

video field every twelfth film frame) you should run the audio at its normal speed

regardless of where sync is established. Use 25 fps timecode for the audio in this case.

Synchronizing in Final Cut Pro

If you don’t synchronize your sound and picture onto tape via the telecine transfer,

they are captured into Final Cut Pro as separate audio and video clips. You can then

synchronize them in Final Cut Pro, using the clapper board shots, as mentioned in

“Synchronization Basics” on page 31. Once you synchronize two or more clips, you can

link them together as one clip, using the Final Cut Pro merged clips feature. See

“Synchronizing Separately Captured Audio and Video” on page 138, and the

Final Cut Pro documentation, for more information.

32 Part I Using Cinema Tools

Page 33

I

Working in Final Cut Pro

Decisions you make regarding the telecine transfer and how you work with audio affect

how you use Final Cut Pro during the editing process.

Setting the Editing Timebase for Sequences

In Final Cut Pro you must set the editing timebase for sequences to match the frame

rate of the captured clips.

Important: Do not place clips into a sequence if the clips and sequence have different

frame rates. If you do, the resulting film list is likely to be inaccurate. For example, if you

want to edit at 24 fps, make sure your clips’ frame rates are all set at 24 fps (either by

using the Reverse Telecine or Conform features).

See “About Easy Setups and Setting the Editing Timebase” on page 143 and the

Final Cut Pro documentation for details about setting the editing timebase for sequences.

Outputting to Videotape When Editing at 24 fps

One of the benefits of editing at 24 fps is that you get a one-to-one relationship

between the film and video frames, allowing for very accurate cut lists. A drawback is

that you need a 24p VTR to directly record video as 24 fps—you cannot easily record

the video on standard NTSC or PAL video equipment. This can be a problem if you

want to record a videotape of the edited project, either to show others or to give the

negative cutter a visual reference to use along with the cut list, but there are solutions:

If you’re working with NTSC video: You can use the pull-down insertion feature in

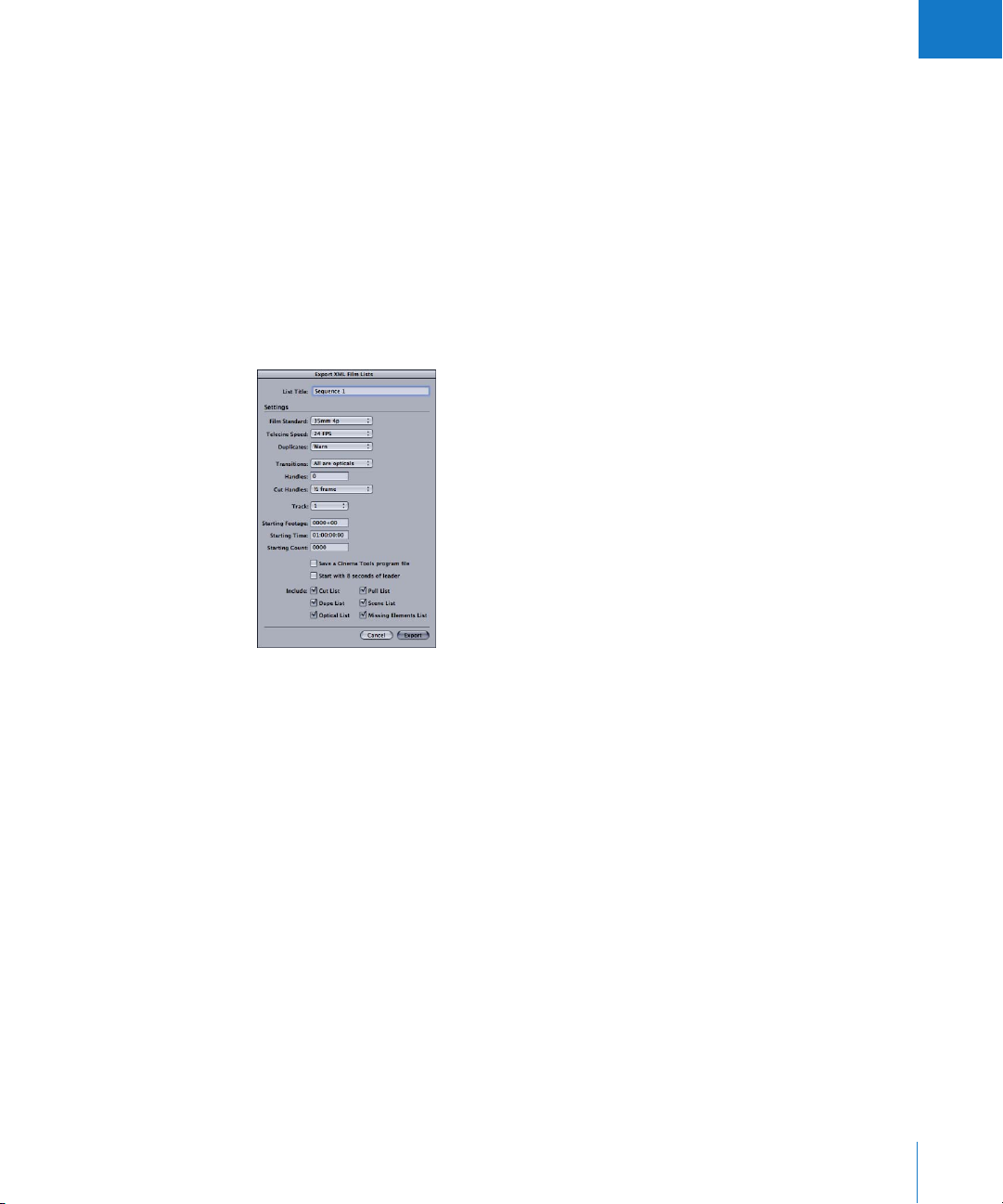

Final Cut Pro to apply a pull-down pattern to the video, thus outputting it at

29.97 fps. See “Pull-Down Patterns You Can Apply to 23.98 fps Video” on page 215 for

details. There are also third-party cards and applications that can perform a

3:2 pull-down on the video, allowing it to run at the NTSC 29.97 fps rate.

If you’re working with PAL video: If you know that you will want to record a videotape

when finished, it’s easiest to edit at 25 fps (with the film having been sped up to

maintain the one-to-one relationship).

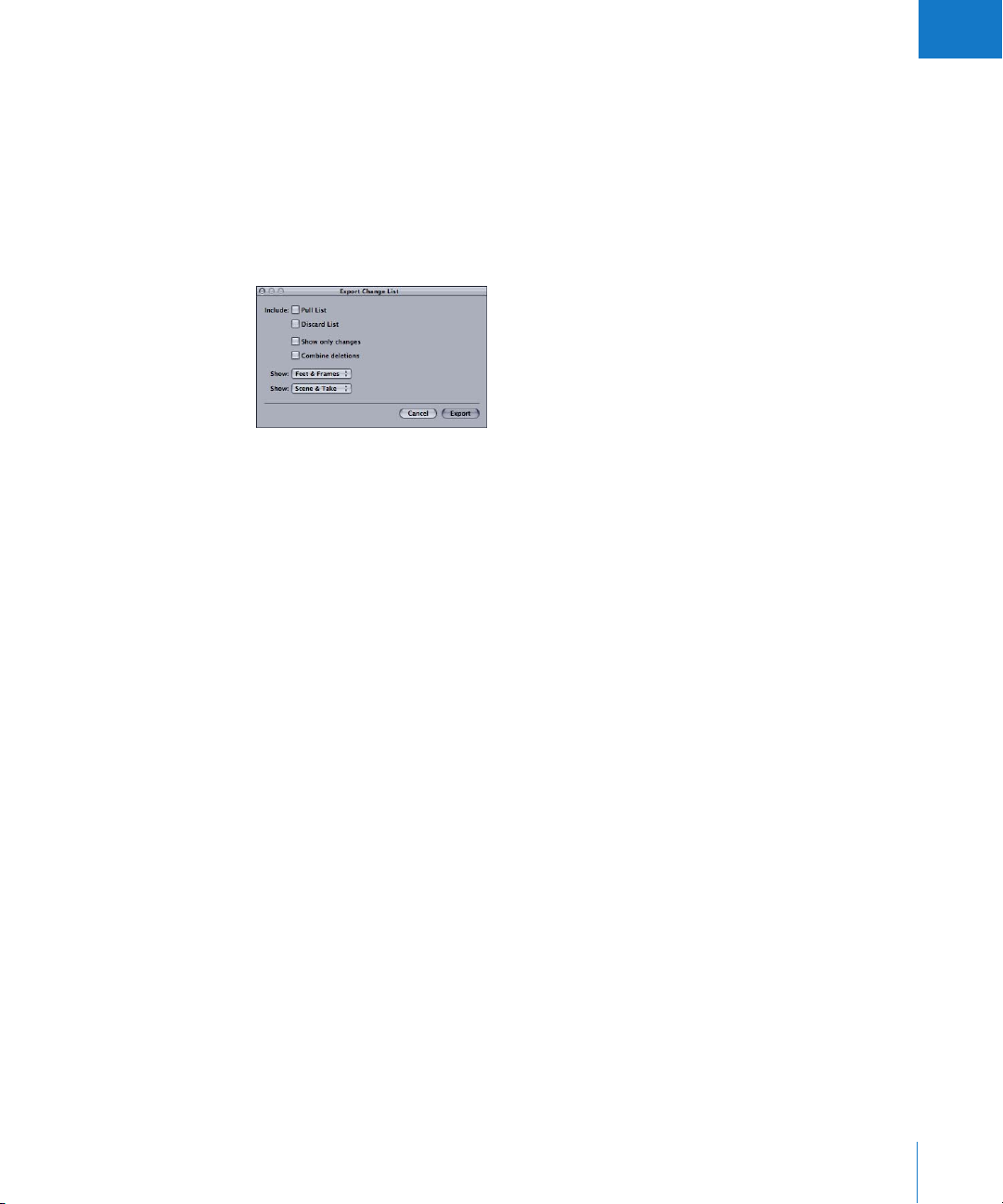

Using Effects

Final Cut Pro provides extensive effects capabilities, including common film effects

such as dissolves, wipes, speed changes, and text credits. Keep in mind that the video

output of Final Cut Pro is not intended to be transferred to film, and these effects must

be created by a facility specializing in opticals, or created digitally using high-resolution

scans of footage to be composited. See “Using Effects, Filters, and Transitions” on

page 152 for more information, including an outline of the basic workflow for including

effects and transitions in your digitally edited film.

Chapter 1 Before You Begin Your Project 33

Page 34

Page 35

2 The Cinema Tools Workflow

Cinema Tools fits easily into a film editing workflow.

The primary purpose of Cinema Tools is to create an accurate cut list based on edits

made in Final Cut Pro. There are a few critical steps that are necessary for this to

happen, but for the most part, the actual Cinema Tools workflow depends on the

equipment you use, your video standard, and how you like to work.

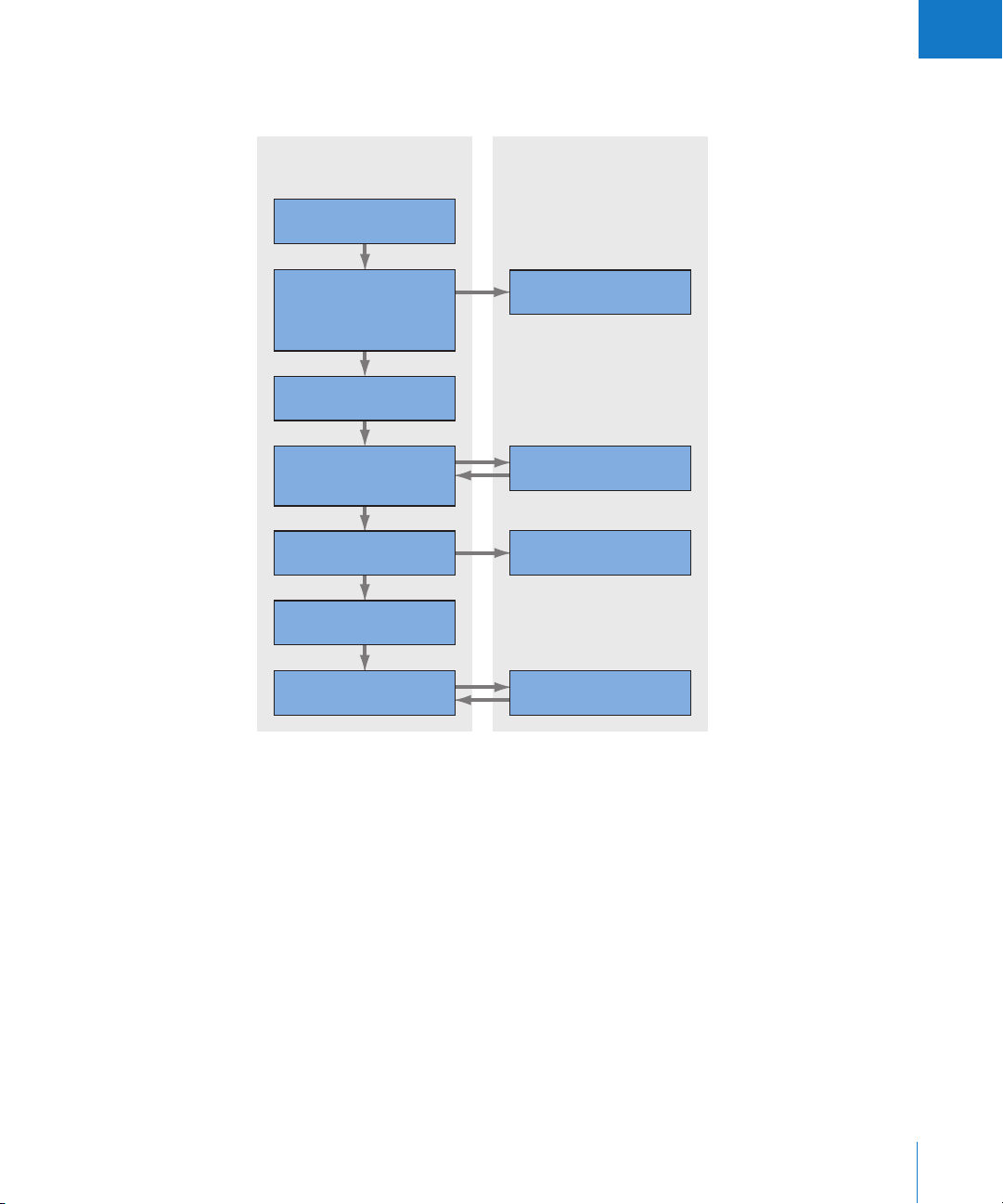

Basic Workflow Steps

The typical Cinema Tools workflow looks like this (each of these steps is discussed in

detail in the following sections):

Step 1: Create the Cinema Tools database

2

Step 2: Capture the source clips with Final Cut Pro

Step 3: Connect the clips to the database

Step 4: Prepare the clips for editing

Step 5: Edit the clips in Final Cut Pro

Step 6: Create cut lists and other lists with Cinema

35

Tools

Page 36

Creating the Cinema Tools Database

The heart of Cinema Tools is its database, where the relationships between the

elements of your movie (the film, video, and sound) are established and tracked. While

there is no actual requirement that the database be created prior to editing, it can

provide some useful tools to help with capturing clips and planning the edit.

How the Database Works

The database can contain one record or thousands of records, depending on how

you decide to use Cinema Tools. These records are matched to the edits made in

Final Cut Pro so that the cut list can be created. To be valid, a record must have values

for the camera, daily, or lab roll, the edge code, and either have a clip connected to it

or have video reel and video timecode (In point and duration) values.

When you export the cut list after editing the video in Final Cut Pro, Cinema Tools looks

at each edit and tries to find the appropriate record in its database to determine the

corresponding key numbers or ink numbers (edge code). Cinema Tools first looks for a

record connected to the clip name used in the edit. If it is found, it then locates the clip

file, a note is added to the cut list, and Cinema Tools moves on to the next edit.

If no record is found using an edit’s clip name, or the clip is not located, Cinema Tools

looks at the video reel number to see if any of its records have the same number (“001”

is not the same as “0001”). If so, it then looks to see if the edit’s In and Out points fall

within the range of one of the records. If this condition is also met, the edit is added to

the cut list, and Cinema Tools moves on to the next edit.

If a record cannot be found that uses an edit’s clip pathname or video reel number with

suitable timecode records, “<missing>” appears in the cut list and a note is added to

the missing elements list. If a record is found but is incomplete (missing the key

number, for example), “<missing>” is placed in those fields and a note is added to the

missing elements list.

See Chapter 8, “Generating Film Lists and Change Lists,” on page 159 and Appendix B,

“How Cinema Tools Creates Film Lists,” on page 233 for details about this process and

the missing elements list.

36 Part I Using Cinema Tools

Page 37

I

A Detailed or Simple Database?

Cinema Tools is designed to allow you to create a record for an entire camera roll, for

each take, or somewhere in between, depending on how you like to work. Each record

can contain:

Scene, shot, and take numbers with descriptions

The film’s camera roll number, edge code, and related video timecode and reel number

The audio timecode and reel number

A clip poster frame showing a representative frame from the clip

Basic settings such as film and timecode format

The records can be entered manually or imported from a telecine log. You can

modify, delete, and add records to the database as required, even if it is based on the

telecine log. You can also merge databases. For example, if you are working with

dailies, you can create a new database for each session and merge them all together

once the shoot is complete.

The telecine log from scene-and-take transfers, where only specified film takes are

transferred to video, can provide the basic information for the database. You can add

additional records, comments, and other information as needed.

The telecine log from camera-roll transfers typically provides information for a single

record—the edge code and video timecode used at the start of the transfer. Assuming

continuous film key numbers and video timecode throughout the transfer, that single

record is sufficient for Cinema Tools to generate a cut list for that camera roll.

Importing Telecine Logs

You have a choice of importing the telecine log using Cinema Tools or Final Cut Pro.

You can choose either method according to your workflow.

In both cases, you have the option of assigning a camera letter, which is appended to the

take entries, to the import. This is useful in those cases where multiple cameras were used

for each take. See “Assigning Camera Letters” on page 84 for more information.

See “Importing Database Information from a Telecine Log or ALE File” on page 83 for

more information about importing telecine logs.

Importing Telecine Logs Using Cinema Tools

To import a telecine log into Cinema Tools, you must first have a database open. The

database can be an existing one that you want to add new records to, or it can be a

new one with no records.

Once the records have been imported, you can export a batch capture list from

Cinema Tools that you can import into Final Cut Pro to automate the clip capture process.

Chapter 2 The Cinema Tools Workflow 37

Page 38

Importing Telecine Logs Using Final Cut Pro

When you import a telecine log using Final Cut Pro, you choose whether to import it

into an existing Cinema Tools database or whether a new database should be created.

As records are added to the selected Cinema Tools database, each record also creates

an offline clip in the Final Cut Pro Browser so that clips can be batch captured. The

film-related information from the telecine log is automatically added to each clip. You

can show this information in a variety of ways while editing the clips in Final Cut Pro.

See “Displaying Film Information in Final Cut Pro” on page 146 for more information.

Manually Entering Database Records

The most common reason to manually enter a record into the database is that there is

no log available from the film-to-video transfer process. Some film-to-video transfer

methods, such as film chains, do not provide logs.

Each record in a database must refer to a media file that has continuous timecode and

key numbers. With scene-and-take transfers, each take requires its own record since

film key numbers are skipped when jumping from take to take during the transfer.

With camera-roll transfers, since the film roll and video recorder run continuously from

start to finish, you require only one record for the entire clip, even if you later break it

into smaller clips (that retain the original timecode) and delete the unused portions.

This is because Cinema Tools can use an edit’s video reel number and edit points to

calculate the appropriate key numbers, as long as the video reel and edit point

information is part of a record.

To manually enter database records, you need to know the key number and video

timecode number for a frame of the clip. This is easiest when the transfer has these

values burned in to the video.

See Chapter 4, “Creating and Using a Cinema Tools Database,” on page 67 for details

about creating and managing Cinema Tools databases.

Are the Window Burn Numbers Correct?

There are a variety of reasons why the window burn values might not be correct,

ranging from incorrectly entered values to faulty automatic detection. You must verify

the accuracy of the window burn values. It is critical that these values be correct if

you are going to rely on them. The key number is usually verified by comparing the

displayed value with a documented value on a hole-punched or marked frame near

the head of the clip. Make sure you verify this at least once for each camera roll

(preferably for each take). Compare the timecode in the window burn with the value

the videotape deck displays.

38 Part I Using Cinema Tools

Page 39

I

Capturing the Source Clips

You must capture the video and audio on your editing computer. How you do this

depends in large part on the actual media used for the telecine transfer.

If you used an analog VTR, such as a Sony Betacam, the video and audio must be

converted to digital format and compressed before they can be used. If you used a

digital VTR, such as a Sony Digital Betacam, the video and audio are already digital, but

must still be captured and compressed. In both cases, specialized hardware with the

appropriate connections is usually required.

If you used a DV system, the video (and audio, depending on the transfer type) is

already digital and compressed, and simply needs to be captured using FireWire.

Important: When using serial device control, make sure to calibrate its capture offset.

See the Final Cut Pro documentation for more information. Also see “Setting Up Your

Hardware to Capture Accurate Timecode” on page 107 for more information about

capturing your clips.

In either case, you may decide to recompress the files to make them smaller and easier

to work with. For example, taking advantage of the correct codec may allow you to edit

on an older portable computer.

About Compression

Compression, in terms of digital video, is a means of squeezing the content into

smaller files so that they require less hard disk space and potentially less processor

power to display. The tradeoff is lower-quality images.

It’s important to remember that the edited video that results from Final Cut Pro when

used with Cinema Tools is not typically going to be used for anything where high

quality would be expected. The most common use of the edited video is to give the