Page 1

Programme’s After Market Services

NHP–4 Series Transceivers

Chapter 3

System Overview

Issue 1 04/99

Page 2

NHP–4

System Overview

Technical Documentation

CONTENTS

Acronyms 3–4. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Cellular History 3–5. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Code Division Multiple Access (CDMA) 3–6. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Quadrature Phase Shift Keying – QPSK 3–9. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The CDMA Signal 3–10. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Processing Gain 3–11. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The CDMA Forward Link 3–12. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

V ocoder 3–13. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Convolutional Encoder 3–13. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Interleaver 3–14. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

PAMS

Page No

PN Code Generation 3–14. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Long Code Scrambling 3–16. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Walsh Code User Channelization 3–16. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Walsh Codes 3–17. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Orthogonal Functions 3–18. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Short Code Spreading 3–24. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Forward Link Channel Format 3–24. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

CDMA Reverse Link 3–27. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Data Burst Randomizer 3–27. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Reverse Link Error Protection 3–28. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

64–ary Modulation 3–28. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Reverse Channel Long Code Spreading 3–28. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Reverse Channel Short Code Spreading 3–28. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Mobile Phone Operation 3–29. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Pilot Channel 3–29. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Sync Channel 3–30. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Paging Channel 3–30. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Page 3–2

CDMA Call Initiation 3–31. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Reverse Link Open Loop Power Control 3–31. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

CDMA Call 3–32. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Reverse Link Closed Loop Power Control 3–32. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

CDMA Variable Rate Speech Coder 3–32. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Mobile Power Bursting 3–32. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The Rake Receiver 3–33. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

CDMA Hand–offs 3–34. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Issue 1 04/99

Page 3

PAMS

NHP–4

Technical Documentation

System Overview

List of Figures

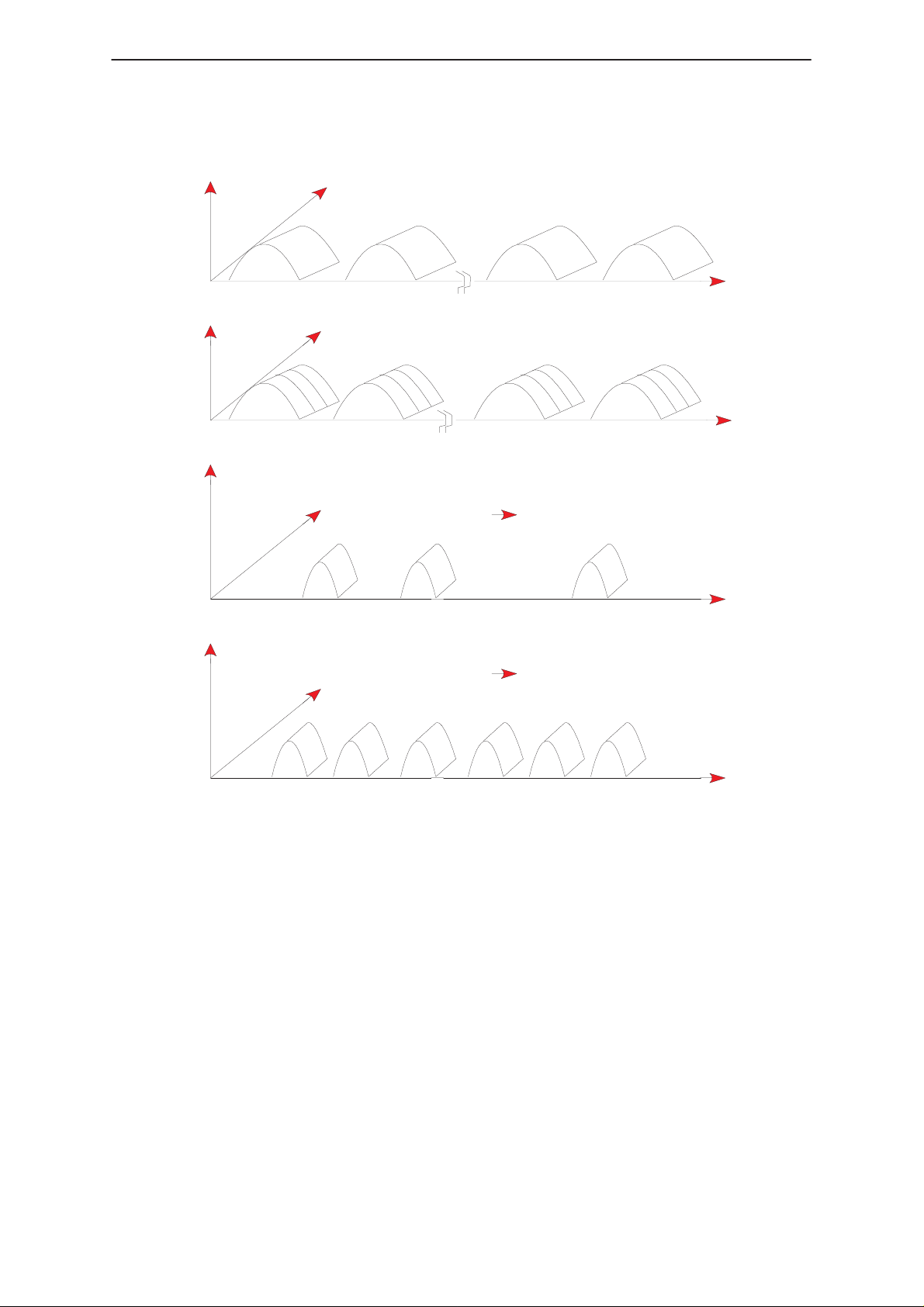

Figure 1. TDMA & CDMA Freq and time domain 3–6. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

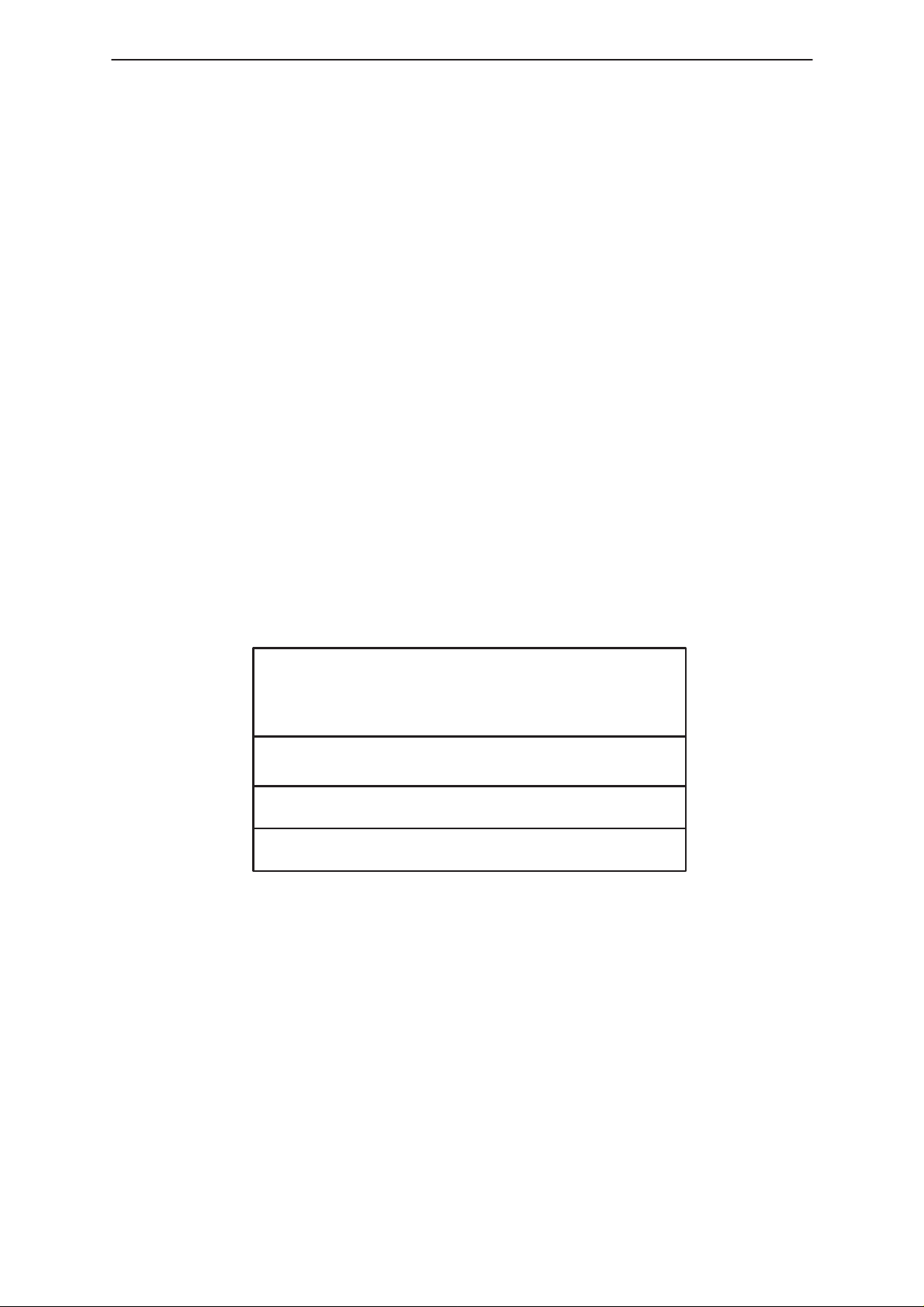

Figure 2. CDMA Capacity gains 3–7. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Figure 3. TDMA & CDMA Structure 3–8. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Figure 4. BPSK Modulator 3–9. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Figure 5. I/Q Modulator 3–10. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Figure 6. CDMA Waveforms 3–10. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Figure 7. CDMA Forward Link 3–12. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Figure 8. Convolutional encoder 3–13. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Figure 9. Interleaver 3–14. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Figure 10. PN Code generator 3–14. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Figure 11. PN Code generator w/mask ckt. 3–15. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Page No

Figure 12. Mask offset example 3–16. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Figure 13. CDMA Forward Link 3–16. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Figure 14. Walsh code example 3–17. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Figure 15. Orthogonal Functions. 3–18. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Figure 16. Walsh Encoding Example 3–19. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Figure 17. Walsh Decoding Example 3–20. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Figure 18. Definition of orthonogonality 3–21. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Figure 19. Forward Link Channel Format 3–26. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Figure 20. CDMA Reverse Link 3–27. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Figure 21. CDMA Pilot & Synch Channel Timing 3–29. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Figure 22. Mobile Power Bursting 3–33. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Figure 23. CDMA Hand–off 3–34. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Issue 1 04/99

Page 3–3

Page 4

NHP–4

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

System Overview

Acronyms

PAMS

Technical Documentation

AMPS

BS

ББББББББ

CDMA

CTIA

DAMPS

ББББББББ

DTMF

FDMA

GSM

ББББББББ

HLR

ISDN

MS

ББББББББ

MSC

MTSO

MTX

ББББББББ

NADC

Advanced Mobile Phone System

Base Station

БББББББББББББББББББББ

Code Division Multiple Access

Cellular Telecommunications Industry Association

Digital Advanced Mobile Phone System

БББББББББББББББББББББ

Dual Tone Multi Frequency

Frequency Division Multiple Access

Global System for Mobile communications

БББББББББББББББББББББ

Home Location Register

Integrated Services Digital Network

Mobile Station (Cellular phone)

БББББББББББББББББББББ

Mobile Switching Center (see MTX also)

Mobile Telephone Switching Office

Mobile Telephone Exchange (see MSC also)

БББББББББББББББББББББ

North American Digital Communications (IS–54 DAMPS)

PCH

PN Code

ББББББББ

PSTN

RF

SAT

ББББББББ

ST

TCH

TS

ББББББББ

VLR

VOCODER

VOCODER

Paging Channel

Pseudo random Noise Code

БББББББББББББББББББББ

Public Switched Telephone Network

Radio Frequency

Supervisory Audio Tone (5970, 6000 and 6030 Hz)

БББББББББББББББББББББ

Signaling Tone (10 kHz)

Traffic CHannel

Time Slot

БББББББББББББББББББББ

Visitor Location Register

VOice COder DEcodeR

VOice CODER

Page 3–4

Issue 1 04/99

Page 5

PAMS

NHP–4

Technical Documentation

System Overview

Cellular History

Mobile Radios have been in use for approximately 70 years and the cellular concept

was conceived in the 1940s. Public cellular mobile radio was not introduced in the

US until 1983.

In the beginning of the twentieth century, mobile radios were limited to shipboard

use due to the high power requirements and bulky tube radio technology.

Automotive systems in the 1920s operated on 6 volt batteries with a limited storage

capacity.

One of the first useful means of automotive mobile radio occurred in 1928 by the

Detroit police department. Transmission was broadcast from a central location and

could only be received by the mobile police radios.

Introduction of the first two way mobile application was delayed until 1933. This

simplex AM (Amplitude Modulation) push to talk system was introduced by the

police department in Bayonne, New Jersey. The first FM (Frequency Modulation)

mobile transmission (two frequency simplex) was used by the Connecticut State

Police at Hartford in 1940.

The first step towards mobile radio connection with the land line telephone network

was established in St. Louis in 1946. It was called an “urban” system and only

supported three channels.

In 1976, New York City had only 12 radio channels that supported 545 subscribers

with a waiting list of 3700.

In the 1970s, available cellular spectrum was constrained to frequencies above 800

MHz due to equipment design limitations and poor radio propagation characteristics

at frequencies above 1–GHz, this resulted in the allocation of the 825–890 MHz

region.

In 1974, 40 MHz of spectrum was allocated for cellular service and in 1986, an

additional 10 MHz of spectrum was added to facilitate expansion. The present

frequency assignments for the US Cellular system mobile phone is

824.040–848.970 MHz transmit and 869.040–893.970 MHz receive These bands

have been frequency divided (FDMA) into 30 kHz channels. This results in a

maximum capacity of 832 channels. These channels were then divided into two

groups with 416 channels assigned to each system.

Issue 1 04/99

Page 3–5

Page 6

NHP–4

System Overview

Code Division Multiple Access (CDMA)

PAMS

Technical Documentation

Amplitude

RX Ch1 RX Ch...n TX Ch 1 TX Ch...n

Amplitude Time

Amplitude

Time

Time

Channelization – FDMA

Channelization – TDMA

3

2

1

3

2

1

3

2

1

TX Ch...nTX Ch 1RX Ch...nRX Ch1

Channelization – CDMA

Forward Link B.S. M.S.

PN Offset 1 PN Offset 2 PN Offset 512

. . .

Frequency

3

2

1

Frequency

PN Sequence

(short code)

Channelization – CDMA

Amplitude

Time

CDMA01.DRW

Reverse LinkM.S. B.S.

Allows Channalization

and privacy

42

2

possible

PN Sequence

(long code)

Figure 1. TDMA & CDMA Freq and time domain

With FDMA Channelization (Analog AMPS), a channel is 30 kHz wide, this where all

the signal’s transmission power is concentrated. Different users are assigned

different frequency channels. FDMA is the acronym for Frequency Division Multiple

Access. Interference to and from adjacent channels is limited by the use of

bandpass filters that only pass signal’s within a specified narrow frequency band

while rejecting signals at other frequencies. The analog FM cellular system AMPS,

uses FDMA.

The US 800 MHz cellular system divides the allocated spectrum into 30 kHz

bandwidth channels. Narrowband FM modulation is used with AMPS, resulting in 1

call per 30 kHz of spectrum. Because of interference, the same frequency cannot

be used in every cell.

Page 3–6

Issue 1 04/99

Page 7

PAMS

NHP–4

Technical Documentation

System Overview

The frequency reuse factor is a number representing how often the same frequency

can be reused. To provide acceptable call quality, a Carrier–to–Interference ratio

(C/I) of at least 18 dB is needed. Practical results show that in most cases to

maintain a 18 dB (C/I) a frequency reuse factor of 7 is required. Please note that C/I

is carrier to interference, not signal to noise ratio The resulting capacity is one call

per 210 kHz of spectrum in each cell.

With TDMA, a channel consists of a time slot in a periodic train of time intervals

making up a frame. A given signal’s energy is confined to one of these time slots.

The IS–54B TDMA standard provides a basic modulation efficiency of three voice

calls per 30 kHz of bandwidth. The resulting capacity is one call per 70 kHz of

spectrum or three times that of the analog FM system.

With CDMA each signal consists of a different pseudo random binary sequence that

modulates the carrier, spreading the spectrum of the waveform. A large number of

CDMA signals share the same frequency spectrum. The signals are separated in

the receivers by using a correlator that accepts only signal energy from the selected

binary sequence and de–spreads its spectrum simultaneously. The other users’

signals, whose codes do not match, are not de–spread and as a result, contribute

only minimally to the noise and represent a self–interference generated by the

system. The forward link (B.S. to M.S.) “channels” are separated by offsets in the

short code PN sequence. Reverse link channels are separated by different long

code PN sequences. A detailed description of the forward and reverse links is

given later.

CDMA = 1.5 MHz 1 CDMA channel + 1.2288MHz

Capacity varies between 30 to 40 calls per CDMA

channel. Actual capacity depends Rho, processing

gain, error correction coding gain of M.S. vs signals

in cell and external cell signals.

AMPS = 1.5 MHz / 30kHz = 50 Channels

Capacity = 50 Channels / 7 (1 in 7 Frequency Reuse)

AMPS = 7 calls

DAMPS = 1.5 MHz / 30 kHz = 50 Channels

Capacity = 50 Channels / 7 x 3 Time Slots

DAMPS = 21 calls

GSM = 1.5 MHz / 200 kHz = 7 Channels

Capacity = 7 Channels / 7 x 8 Time Slots

GSM = 8 calls

Figure 2. CDMA Capacity gains

CDMA Capacity

Why should NOKIA go to so much trouble to develop CDMA? CAPACITY! To see

how CDMA increases capacity over present 800 MHz systems (AMPS and DAMPS)

lets look at a 1.5 MHz span of frequencies and compare. A CDMA frequency

channel is 1.2288 MHz wide however to provide guard bands in order to reduce

potential interference with adjacent analog channels a total of 1.5 MHz will be used.

Issue 1 04/99

Page 3–7

Page 8

NHP–4

System Overview

Technical Documentation

PAMS

The AMPS, DAMPS, and GSM capacity examples assume that only one channel

out of every seven can be used. In a crowded metropolitan area, cellular base

stations are arranged like the top part of Figure 3 Each base station is surrounded

by seven others so only one out every 7 channels can be used or adjacent channel

interference will occur. However, such is not the case for CDMA because all users

on a “CDMA Channel” operate on the same frequency. I’ve just used the word

“Channel” in a different way. Users in a given CDMA channel are separated by

different PN code sequences. According to information at the present time there

four designated CDMA frequency channels, so users on a given frequency channel

operate on the same frequency and are separated by different PN code sequences

which are also called “Channels”.

2

2

7

1

6

5

7

3

6

4

2

7

1

6

5

3

1

4

5

7

3

6

4

CDMA Cell Structure

Transmission range of

any given celll

1

1

ANALOG & TDMA Cell Structure

Transmission range of

any given cell

2

3

1

4

5

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

CDMA03.DRW

Page 3–8

Figure 3. TDMA & CDMA Structure

Issue 1 04/99

Page 9

PAMS

NHP–4

Technical Documentation

System Overview

Quadrature Phase Shift Keying – QPSK

Forward link transmissions from the Base Station (BS) to the Mobile Subscriber

(MS) use QPSK modulation. QPSK is the sum of Two Binary Shift Keyed (BPSK)

signals. Figure 4 shows how a BPSK signal is made up.

180

Time

0

TT

TT

Reference

carrier

input

Carrier

input

Carrier

input

DAMPS_4

A

T1 T2

B

++ ++

0 deg

–– ––

C

++

0 deg

––

Binary Phase Shift Keying

D1

D3

D4

D2

Binary input

D1 (on)

D3 and D4

(off)

D2 (on)

Binary 1

D1 (off)

D2 (off)

Binary 0

––

D3/D4

(on)

++

Modulator

output

Carrier

output

180 deg

Carrier

output

Binary

input

BPSK

output

Degrees

Radians

0 deg

10 1 10

0

TT

180

0

TT

TT

Binary input Output phase

Logic 0 180 deg

Logic 1 0 deg

Figure 4. BPSK Modulator

Before starting any explanation about phase modulation a convention needs to be

established that will carry on throughout this study guide. Digital signals are

generally generated by use of a modulator that generates a sine and a cosine

channel and scales each channel by a factor that ranges from –1 to +1. What

the last sentence means is that the values of Data Channels are –1 and +1, not

0 and 1. A logic one will be “plus one” and a logic zero will be “minus one”.

In drawing ”B” diodes D1 and D2 are forward biased into conduction with a logic

one. Transformer’s T1 and T2 are connected together in an in–phase condition. In

this case the output carrier’s signal would have the same phase as the input.

In drawing “C”diodes D3 and D4 are forwarded biased into conduction with a logic

zero. The output of T1 is cross connected to the input of T2 which will result in the

output being 180 degrees out of phase with the input signal.

Issue 1 04/99

Page 3–9

Page 10

NHP–4

System Overview

PAMS

Technical Documentation

I DATA

SIN

CARRIER

INPUT

Values of Data Channels

are –1 and 1, not 0 and 1

90

Hybrid

COS

o

Σ

For the reverse link

the Q data is delayed

CDMA04.DRW

Q DATA

by 1/2 clock chip. This

modulation is called

OQPSK (Offset Quadra

Phase Shift Keying)

Figure 5. I/Q Modulator

In Figure 5 the 90 phase shifter is used to generate the sine and cosine channel

reference frequency. The two signal paths are called the “In phase” and the

“Quadrature phase” paths, therefore the name, I/Q modulator.

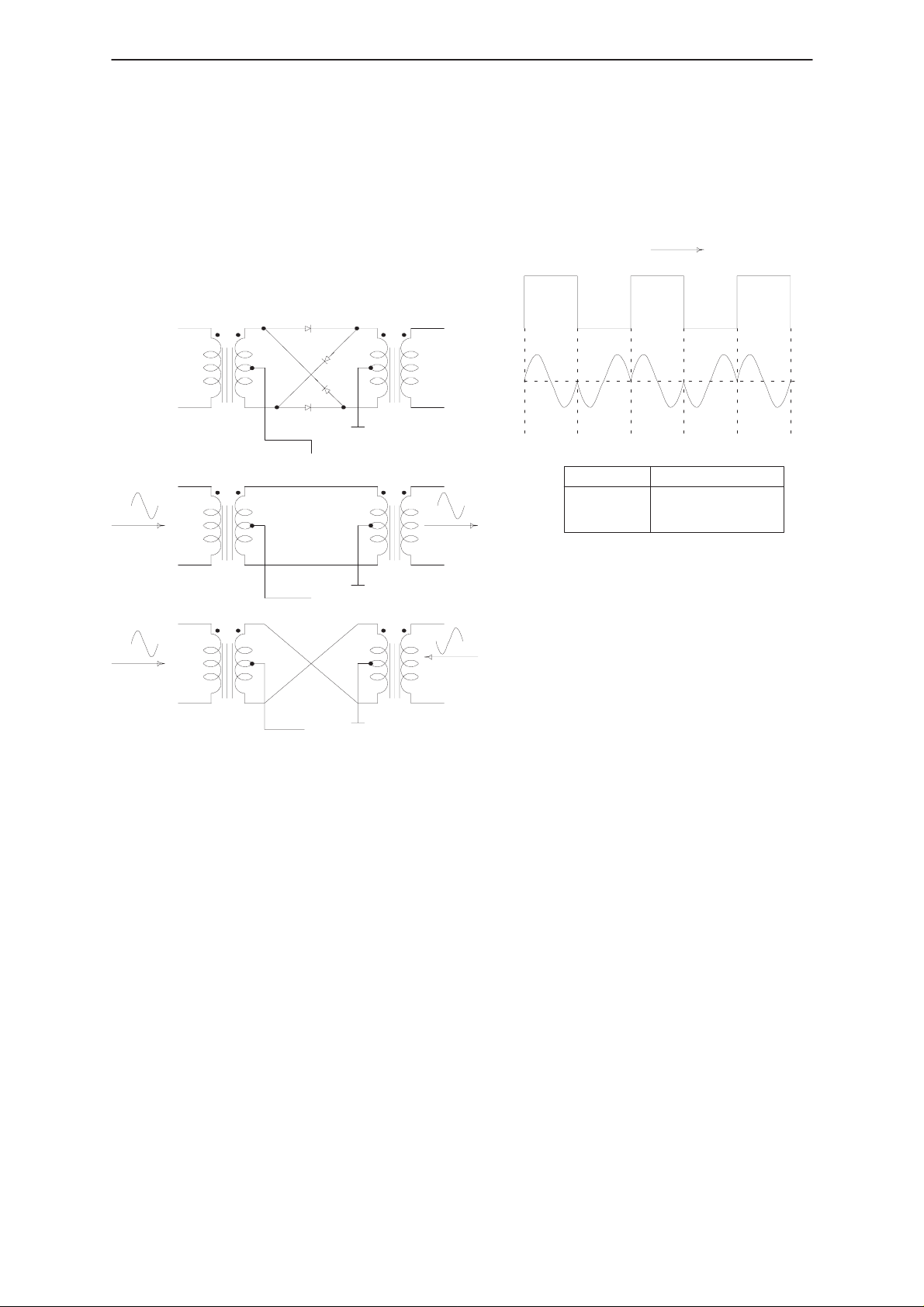

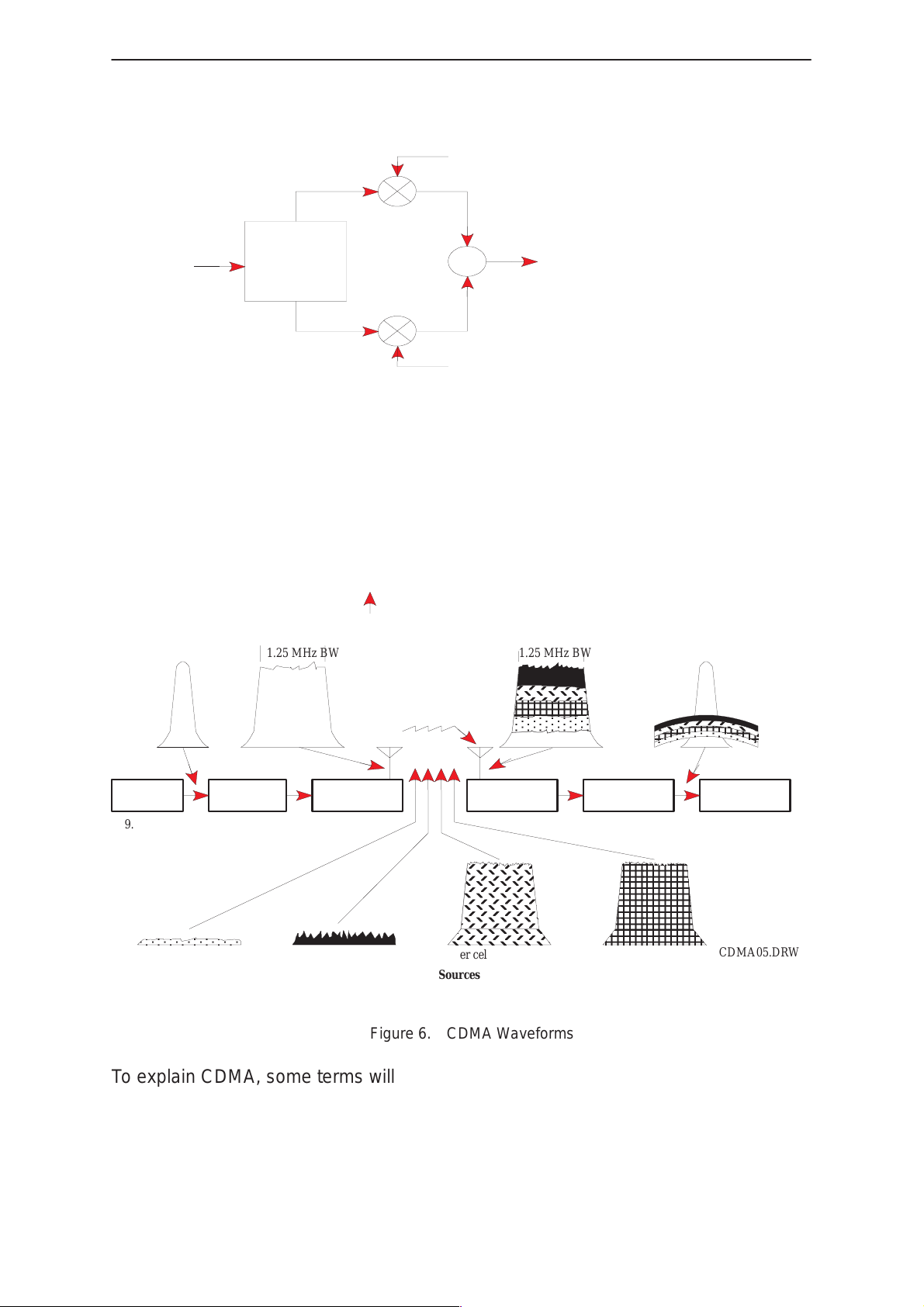

The CDMA Signal

CDMA

Transmitter

CDMA

Receiver

1.25 MHz BW1.25 MHz BW

10 kHz BW10 kHz BW

Baseband

Data

9.6 kbps 19.2 kbps 1228.8 kbps

Background Noise

Encoding &

Interleaving

Walsh Code

Spreading

External Interference Other cell interference Other User Noise

Interference Sources

Walsh Code

Correlator

1228.8 kbps

Decode & De–

interleaving

19.2 kbps 9.6 kbps

Baseband

Data

CDMA05.DRW

Figure 6. CDMA Waveforms

To explain CDMA, some terms will have to be used that most persons are not

familiar with, but have patience they will be given a full explanation later in this Study

Guide. Forward link (BS to MS) CDMA starts with a narrowband signal that is

digitized speech. In this example the

full rate speech data rate

of 9600 bps is

shown.

Page 3–10

Issue 1 04/99

Page 11

PAMS

NHP–4

Technical Documentation

Speech data rates from the VOCODER can vary from 1200 BPS to 9600 BPS when

using “Rate Set One” and 14.4, 7.2, 3.6, and 1.8 kbps when using “Rate Set Two”.

A specialized digital code called a Walsh Code provides “user” channelization for the

forward link (B.S to M.S.) and is used to encode the reverse link (B.S. to M.S.) user

data. The short code PN sequence

reverse links. The short code also provides channelization for BASE STATIONS on

the forward link by using a masking circuit. Masking will be explained later.

Processing Gain

One of the unique aspects of IS–95 standard CDMA is 21 dB of processing gain.

Processing gain is computed by using the formula 10 log(spread data rate) divided

by (Symbol rate). [10 log (1,228,800 / 19.2kBPS) = 21 dB]. If you calculate the

processing gain using the numbers in the last sentence the answer is 18 dB. The

extra 3 dB is comes from the same data being transmitted by the Q channel. If rate

set 2 is used the processing gain is 19.31 dB. When “your” CDMA signal is

transmitted all other CDMA signals along with background noise and any spurious

signals are considered interference.

SPREADS

the baseband for both forward and

System Overview

When the wanted CDMA signal, “yours”, is received the correlation receiver

recovers “your” signal and rejects the rest. Looking at Figure 6, the upper right

most part of the drawing shows what happens to the unwanted signals. The

unwanted signals are not de–spread so that each interfering signal only contributes

a little to the noise floor while “your” wanted signal is de–spread and will have an

acceptable signal–to–noise ratio. This is where the processing gain comes into

play. The processing gain is 21 dB and it takes a signal–to–noise ratio of about 7

dB for acceptable voice quality. This leaves 14 dB of processing gain to extract

“your” signal from the noise.

Here are some of the differences between CDMA and analog FM (AMPS).

Multiple users are on one frequency at the same time. RF engineers have spent a

lot of time and effort trying to keep signals on one channel so that adjacent channel

signals would not cause interference. CDMA technology places a great many

conversations (signals) on the same frequency.

In CDMA a channel is defined by various digital codes in addition to having different

frequencies. Analog FM channels are defined by different frequencies only.

An analog FM (AMPS) cell site has a hard limit on the number of users it can

accommodate, only one call per frequency channel. CDMA has a soft capacity

limit. If cells surrounding a heavily loaded cell are lightly loaded then the heavily

loaded cell site can accommodate additional users. CDMA has a soft limit because

less “other cell” interference causes the total interference to be less. More calls can

also be accommodated at the expense of lower voice quality (S/N), this because

each additional user adds only a small amount of interference to the total.

Issue 1 04/99

Page 3–11

Page 12

NHP–4

System Overview

The CDMA Forward Link

PAMS

Technical Documentation

20 MSEC

BLOCKS

Vocoded

Speech

data

Convolutional

Encoder

9.6

kbps

1/2

Rate

Long Code

Generator

19.2

kbps

CDMA Forward Link

Interleaver

19.2

kbps

Long Code

Decimator

1.2288

Mbps

1 of 64 bits

XOR

Power

Control

Bit

1 in 24

Decimator

MUX

800 Hz

Walsh Cover

XOR

1.2288

Mbps

Walsh Code

Generator

1.2288

Mbps

1.2288

Mbps

I Short Code

I Channel

Lo Pass

Filter

To I/Q

Modulator

Lo Pass

Filter

Q Channel

Q Short Code

CDMA06,DRW

Figure 7. CDMA Forward Link

When discussing the CDMA Forward Link, voice data will be shown at 9600 BPS

(full rate). Keep in mind that the Vocoded Speech rate can be 9600, 4800, 2400 or

1200 BPS when using Rate Set One. The Vocoded Speech rate is developed after

the CODEC in both the Base Station and the Mobile Phone.

Speech data is passed through a Convolutional Encoder that doubles the data rate.

This data is then Interleaved. Interleaving does not change the data rate but will

introduce some data time delay. The Long Code Generator running at 1.2288

Mbps develops the 242 bits long PN (Pseudo–random noise) code. The long code

Decimator uses one out of every 64 bits of the PN long code and exclusive OR’s this

decimated bit stream with the output of the Interleaver. At this point the data stream

is still running at 19.2 kbps. The 64 bit Walsh Code Generator output running at

1.2288 Mbps is exclusive OR’ed with the pervious exclusive OR gate’s output. The

baseband is now running at a data rate of 1.2288 Mbps, 64 times 19.2 kbps. The

Walsh encoded data stream is then split into I and Q channels, and then each

channel is spread with a short code. Then finally, signals are sent through a low

pass filter to the I/Q modulators.

Page 3–12

Issue 1 04/99

Page 13

PAMS

NHP–4

Technical Documentation

System Overview

Vocoder

CDMA takes advantage of quiet times during speech to raise capacity. A variable

rate VOCODER is used; the vocoder’s output is at 9600 BPS when the user is

speaking. When the user pauses, or is listening, the data rate drops to 1200 BPS.

The data rates of 2400 and 4800 BPS are also used but not as often as the other

two. The data rate is based on speech activity and complexity. A decision is made

on the data rate every 20 msec. Normal speech has about a 40% activity factor. A

40% voice activity factor means that only 40% of transmission time is needed to

transmit the intelligible parts of speech.

Convolutional Encoder

Forward Error Protection

Data in

9600

pbs

D D D D

D D D D

Data Out

9600 bps

CDMA07.DRW

Data Out

9600 bps

Figure 8. Convolutional encoder

The forward CDMA link uses a half–rate convolutional encoder to provide error

correction capabilities. A half–rate encoder produces two output bits for every bit

input. This type of encoder accepts incoming serial data and outputs encoded data.

A convolutional encoder uses a shift register that contains a history of the bit

stream. It starts with all zeros and the data stream is shifted through. The two

9600 BPS output data streams are combined at a higher rate to provide a single

19,200 BPS data stream.

Issue 1 04/99

Page 3–13

Page 14

NHP–4

System Overview

Technical Documentation

PAMS

Interleaver

Data In Data Out

12

34

5 Interleaver

12345

Figure 9. Interleaver

CDMA08.DRW

Interleaving is the process of shuffling the data before transmission with a

corresponding un–shuffle on the receiving end. The purpose is to spread the bit

errors. Bit errors tend to come in bursts due to fading, rather than uniformly spread

in time. Interleaving provides a more uniform bit error distribution so that one burst

of errors will not wipe out a whole digital word but only individual bits that can be

corrected by the convolutional decoding.

PN Code Generation

Pseudorandom Noise (PN)Sequences

00 1

10 0 0

Pattern = 1001011

01 0 0

Figure 10. PN Code generator

1

CDMA09.DRW

The illustration above is a highly simplified version of a PN code generator. It will

be left to the reader to fill in the blank registers. This generator will start repeating

after 7 bits. A CDMA long code register is 42 bits long and the short code register

15 bits long.

Page 3–14

Issue 1 04/99

Page 15

PAMS

NHP–4

Technical Documentation

System Overview

The forward link Short Code is the same for all base stations. However a specific

mask is AND’ed with the output of the code generator to create a unique short code.

Even though the specific mask does not change the PN pattern the code is

considered unique relative to system time. This means that each specific mask will

shift the PN code to a unique delay with respect to system time and in this way the

shifted PN code is considered unique.

Here is another way of saying the same thing: PN codes used are required to have

low auto–correlation properties–––a time shifted version of itself correlated with itself

looks like random noise. Therefore a time shifted version is unique. Short Code

and Long Codes are handled the same: they use time shifted versions to be unique.

An example of a mask is shown in Figure 11. The three–bit shift register in

Figure 10 has a three–bit mask circuit connected to it in Figure 11.

11

0

11

1

0

11 1

11

11

0

0

0

0

00 1

11

00

1

0

0

0

0

10 0

11

00

1

0

11

0

0

1

1

1

0

0

0

1

11

11

Issue 1 04/99

1

0

0

1

1

0

0

0

11

1

0

1

0

0

CDMA10.DRW

1

Figure 11. PN Code generator w/mask ckt.

Page 3–15

Page 16

NHP–4

Á

Á

ÁÁ

ÁÁ

ÁÁ

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

ÁÁ

ÁÁ

Á

ÁÁ

ÁÁ

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

ÁÁ

ÁÁ

Á

ÁÁ

ÁÁ

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

ÁÁ

System Overview

PAMS

Technical Documentation

Offset

ÁÁ

ÁÁ

01

10

11

ÁÁ

100

101

110

ÁÁ

1111

T0

1

0

1

0

1

0

1

T1

ÁÁ

ÁÁ

0

0

0

ÁÁ

1

1

1

ÁÁ

1

T2

Á

Á

0

1

1

Á

0

0

1

Á

1

T3

Á

Á

1

0

1

Á

1

0

1

Á

0

T4

Á

Á

0

1

1

Á

1

1

0

Á

0

T5

ÁÁ

ÁÁ

1

1

0

ÁÁ

1

0

0

ÁÁ

1

T6

Á

Á

1

1

0

Á

0

1

1

Á

0

Base

БББББ

Stations

БББББ

1

2

БББББ

3

4

5

БББББ

6

7

Figure 12. Mask offset example

The above example shows how different offsets will create different codes. Note

that none of the codes has been altered. Each one just starts at a different time.

Remember the CDMA system uses the same 15 bit linear feedback shift register to

generate the PN short code for both forward and reverse links. If figure 28 were

expanded to a 15–bit shift register the time shifted short codes for the 512 base

station channels would be shown.

Long Code Scrambling

In the forward link the long code is used to scramble voice data and provide some

measure of security. However the complete long code is not used, refer to Figure

28. A Long Code Decimator allows only one in every 64 bits of the Long Code to

be exclusively OR’ed with the Encoded Voice Data. This scrambling does not

increase the data rate because two 19.2 kbps data streams are being exclusive

OR’ed with each other.

Walsh Code User Channelization

The CDMA forward link figure will be repeated here to show where we are in the

CDMA forward link (base station to mobile) generation.

20 MSEC

BLOCKS

1.2288

Mbps

1.2288

Mbps

I Short Code

Lo Pass

Filter

Lo Pass

Filter

Q Short Code

CDMA06,DRW

I Channel

To I/Q

Modulator

Q Channel

Vocoded

Speech

data

Convolutional

Encoder

1/2

Rate

9.6

kbps

19.2

kbps

Long Code

Generator

Interleaver

1.2288

Mbps

XOR

19.2

kbps

Long Code

Decimator

1 of 64 bits

Power

Control

Bit

1 in 24

Decimator

MUX

800 Hz

Figure 13. CDMA Forward Link

Walsh Cover

XOR

1.2288

Mbps

Walsh Code

Generator

The 20 msec VOCODED speech data blocks have had an error correction routine

added in the Convolutional Encoder that increased the data rate to 19.2 ksps (kilo

symbols per second).

Page 3–16

Issue 1 04/99

Page 17

PAMS

NHP–4

Technical Documentation

System Overview

The Interleaver changes the data order so only bits instead of whole words would be

lost because of data errors. The Long Code Generator generates a code that is

242 bits long. This code runs at 1.2288 Mbps and takes about 41.5 days before it

repeats. The PN (Pseudo–random) code is decimated by a factor of 64 that means

only one out of 64 bits is XOR’ed with the output of the Interleaver. The data rate at

this point is still 19.2 ksps because two 19.2 ksps data streams have been XOR’ed.

The 64 Walsh codes are used in the forward link as a means to uniquely identify

each user. The Walsh code generator runs at 1.2288 Mbps while the encoded

voice data runs at 19.2 kbps the ratio is 64 or 21 dB of processing gain. This

means that each data bit is XOR’ed with 64 Walsh code bits, one complete 64 bit

Walsh code. The voice data determines the polarity of the Walsh code. This

makes it easier for the CDMA mobile to find and decode its assigned Walsh code.

All base station’s use the same Walsh code 64 set. What gives each base station

its own unique identity will be explained in “Short Code Spreading”

The forward link is now running at its final rate of 1.2288 Mbps.

Walsh Codes

Walsh Codes in the CDMA forward link are used to “make” the CDMA forward

channels. Remember in analog phones a different frequency channel is used to

separate one cell phone user from another. TDMA cell phones use different time

slots to allow 3 phones to share one frequency channel. CDMA uses different

frequency channels like analog and TDMA cell phones. However, to separate

CDMA users on the same base station, different codes are used on the forward link

(Base Station to Mobile). IS–95 Standard CDMA uses Walsh code set 64. This

Walsh set has 64 unique codes each having 64 bits. Figure 14 shows how a Walsh

code set is built up.

W = 0

1

W =

2n

W W

W W

W =

W =

0 0

2

4

0 1

0 0 0 0

0 1 0 1

0 0 1 1

0 1 1 0

CDMA11.DRW

Figure 14. Walsh code example

Walsh code sets are generated by using the formula W2n = W W

W W .

In Walsh code set 2 it can be seen that the lower right digit is the logical not of the

other three digits. In Walsh code 4 the set 2 code is repeated three times with the

logical not being used in the lower right corner. The expansion number is always a

power of 2 and also notice that for each set the first code is always all zeros.

Issue 1 04/99

Page 3–17

Page 18

NHP–4

System Overview

Technical Documentation

PAMS

Walsh codes have the desirable characteristic of being “orthogonal” to each other.

What the heck does that mean(this is a rhetorical question)? ORTHOGONAL

Walsh Codes: when simultaneously transmitted they produce minimal interference

to other users. Look at the rows across in code set 4, any two rows have an equal

number of matches and mismatches. When correlation occurs between codes

(they match up) they will yield a cross correlation coefficient of 1. When the codes

do not match (correlate) the cross correlation coefficient is 0. Another way of

stating this is to say that when receiving the desired code a correlation receiver will

yield data and ignore all the unwanted codes.

Figure 15 should help sort out how Walsh orthogonal codes can keep different

CDMA users separated even though they are on the same frequency.

Orthogonal Functions

Two values are orthogonal if the result of exclusive–ORing them results in an equal

number of 1’s and 0’s.

Figure 15. uses the number 2 code, 0 1 0 1, in the Walsh code set 4 to

“Orthogonally Spread” some user input data. Each bit of user input data is

exclusive–OR’ed with the number 2 Walsh code that will result in TX Data shown in

Figure 15.

Orthogonal Functions:

Two values are orthogonal if the result of

exclusive–or–ing them results in an equal

number of 1’s and 0’s

Orthogonal Spreading:

Note; Each Orthogonal Sequence in the

forward link will have 64 bits rather than

the 4 bits in this example.

User Input 1 0 0 1 1

Orthogonal

Sequence

TX Data

Decoding using a Correct Orthogonal Function

RX Data 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0

Correct

Function

0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1

1 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0

+1

–1

0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1

1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

10 011

+1

–1

EXAMPLE: 1 1 1 1

0 1 0 1

1 0 1 0

Page 3–18

Decoding with Incorrect Orthogonal Function

RX Data 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1

Incorrect

Function

CDMA12.DRW

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0

???? ?

+1

–1

Figure 15. Orthogonal Functions.

Issue 1 04/99

Page 19

PAMS

NHP–4

Technical Documentation

System Overview

When the number 2 Walsh code is exclusive OR’ed with what is now the “RX data”

each number 2 Walsh code yields the original user input data 4 times. The IS–95

CDMA standard uses a 64–bit Walsh code so the mobile cell phone has the

transmitted data repeated 64 times. When the data is repeated 64 times, your have

processing gain. Repeating the processing gain information: 10 log 64 equals 18

dB: another 3 dB is added because the data is modulated on two channels, I and Q

for a total of 21 dB. This is one of the reasons why IS–95 CDMA is so tolerant of

noise. That is to say a signal–to–noise ratio that would render an analog signal

useless works fine with CDMA.

BUT JUST HOW DOES AN ORTHOGONAL WALSH CODE SEPARATE

DIFFERENT USERS?

At first it would seem that broadcasting 25 to 30 code streams on one frequency

would create an “electronic tower of babel”. To explain how Walsh encoding works

a Walsh code set 2 that has 2 orthogonal Walsh codes will be used in Figure 16

User B

User B data 0110

1

0

For a 1 input

use code 01

For a 0 input

use code 10

For a 1 input,

use Code 00

For a 0 input,

use Code 11

+1

–1

+1

–1

User A data 1011

0

0

11

Walsh Encoding ExampleUser A

+1

0

W

2

0 1 – User B

0 0 – User A

=

–1

1

Channel A

Voice data

Channel A

Walsh Encoded

Voice Data

+1

111

0

0

Sum of A & B

Walsh Encoded

Data Streams

0

0

11

0000

+2

+1

–1

–2

Channel B

Voice Data

Channel B

Walsh encoded

Voice data

+1

0110

0

+1

1

00

–1

111

00

CDMA13.DRW

Figure 16. Walsh Encoding Example

This example uses Walsh Code set 2 that has two unique orthogonal codes, “00”

and “01”. Walsh code “00” will be assigned to User A and code “01” to User B.

Now in order for the Walsh code addition to work, bipolar values must be used, so

that a binary “0” has a value of “–1”. Also unless some higher math is utilized one

more convention must be used. If the voice data is a “0”, User A’s Walsh code is

“+1,+1”.

Issue 1 04/99

Page 3–19

Page 20

NHP–4

System Overview

Technical Documentation

PAMS

Here is how the “bipolar” addition works:

Voice data 1 0 1 1

bipolar Walsh code –1–1 +1+1 –1–1 –1–1

Walsh encoded data 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0

The voice data is added to both bipolar Walsh code numbers. The example is for

User A.

If the two Walsh encoded voice data channels are added together the result is a

data stream that varies between +2 and –2. Walsh code decoding will show that

both user data streams are contained in this waveform and further more they do not

interfere with each other.

Original User A Voice Data

+1

+2

+1

–1

–2

Multiply summed data with desired Walsh

code then find the area under the

resultant curve.

+2

+1

111

0

0

+1

+2

+1

Original User B Voice Data

+1

+2

+1

–1

–2

Multiply summed data with desired Walsh

code then find the area under the

resultant curve.

+2

+1

0110

0

User A + B Walsh DataUser A + B Walsh Data

+1

+2

+1

X =

–1

–2

–1

00

–1

–2

=

1

CDMA14.DRW

X==

–1

–2

–1

–1

–2

–1

Figure 17. Walsh Decoding Example

To see how user data is recovered from the summed signal lets extract the first bit of

each users’ data. First remember that each user bit is XOR’ed with two Walsh code

bits in this example. Taking the first two summed data bits, multiply them with

desired Walsh code. For User A this results in a wave form that starts at zero for

the first bit period and goes to +2 in the second bit period, 0 X –1 = 0 and –2 X –1 =

+2. The next step requires a little calculus, very little to figure “the area under the

curve”. Since the waveform is a square wave its not to hard. Add the two resultant

bits and divide by the number of bit periods, (0 + 2) / 2 = 1. User A’s first data bit is

“1”.

Page 3–20

Issue 1 04/99

Page 21

PAMS

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

NHP–4

Technical Documentation

System Overview

To calculate User B’s first data bit multiply (0 X –1) and (–2 X 1) which equals zero,

minus two waveform. Find the area under the curve, (0 + (–2)) / 2 = –1, which is

User B’s first data bit.

It has been stated that Walsh codes are orthogonal and that this property results in

zero cross talk between Walsh code signals. Using bipolar numbers multiply Walsh

code “00” with Walsh code “01”. Add the resulting area and divide by the number of

bit periods and you will get zero. Figure 18 illustrates this.

+1

–1

Walsh code

0 0

00

+1

X=

0

–1

Figure 18. Definition of orthonogonality

Walsh code

0 1

+1

1

CDMA15.DRW

–1

Another and simpler way to state that Walsh codes are orthogonal is that since the

codes have an equal number of matches and mismatches, they are orthogonal.

The full 64–bit by 64 code Walsh code set 64 has been reproduced in the following

table.

Walsh Code Set W64

0

00

00

00

00

00

00

00

00

00

00

00

00

00

00

00

00

01

01

00

110

110

00

00

01

01

00

110

110

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

1

00

Á

2

01

Á

3

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

4

00

Á

5

00

Á

6

01

Á

7

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

00

01

01

00

110

110

00

00

01

01

00

110

110

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

00

01

01

00

110

110

00

00

01

01

00

110

110

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

00

01

01

00

110

110

00

00

01

01

00

110

110

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

8

00

00

Á

9

00

Á

1

01

Á

0

01

Á

1

00

1

110

Á

110

Á

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

110

Á

110

Á

Issue 1 04/99

111

110

10

110

01

00

1

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

00

Á

1

Á

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

110

Á

110

Á

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

110

Á

110

Á

111

110

10

110

01

00

1

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

00

Á

1

Á

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

110

Á

110

Á

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

110

Á

110

Á

111

110

10

110

01

00

1

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

00

Á

1

Á

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

110

Á

110

Á

00

111

Á

00

110

Á

01

10

Á

01

110

Á

00

01

110

00

Á

110

1

Á

Page 3–21

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

00

Á

1

Á

Page 22

NHP–4

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

System Overview

1

00

111

Á

2

00

Á

1

01

Á

3

01

Á

1

00

Á

4

110

Á

1

110

5

Á

1

00

Á

6

00

Á

1

01

Á

7

01

1

00

Á

8

110

Á

1

110

Á

9

Á

2

00

0

00

Á

2

01

Á

1

01

Á

2

00

Á

2

110

Á

2

110

Á

3

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

Á

111

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

111

110

10

110

01

00

1

00

00

01

01

00

110

110

00

00

01

01

00

110

110

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

Á

111

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

Á

111

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

Á

00

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

111

110

10

110

01

00

1

111

110

10

110

01

00

1

111

110

10

110

01

00

1

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

Á

00

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

Á

00

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

Á

111

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

Technical Documentation

111

00

00

110

10

110

01

00

1

00

00

01

01

00

110

110

00

00

01

01

00

110

110

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

Á

111

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

Á

111

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

Á

00

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

111

110

10

110

01

00

1

111

110

10

110

01

00

1

111

110

10

110

01

00

1

PAMS

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

Á

00

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

2

00

00

Á

4

00

00

Á

2

01

01

Á

5

01

01

Á

2

00

00

Á

6

110

110

Á

2

110

110

Á

7

2

00

111

Á

8

00

110

Á

2

01

10

Á

9

01

110

Á

3

00

01

Á

0

110

00

3

110

1

Á

1

Á

Page 3–22

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

111

110

10

110

01

00

1

111

110

10

110

01

00

1

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

110

Á

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

1

Á

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

110

Á

Á

00

00

01

01

00

110

110

00

00

01

01

00

110

110

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

1

Á

Á

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

110

Á

Á

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

1

Á

Á

111

110

10

110

01

00

1

111

110

10

110

01

00

1

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

110

Á

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

1

Á

Á

111

00

00

01

01

00

110

110

00

00

01

01

00

110

110

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

1

Á

Á

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

110

Á

Á

Issue 1 04/99

Page 23

PAMS

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

Á

NHP–4

Technical Documentation

3

00

00

00

Á

2

00

Á

3

01

Á

3

01

Á

3

00

Á

4

110

Á

3

110

5

Á

3

00

Á

6

00

Á

3

01

Á

7

01

3

00

Á

8

110

Á

3

110

Á

9

Á

4

00

0

00

Á

4

01

Á

1

01

Á

4

00

Á

2

110

Á

4

110

Á

3

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

Á

00

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

00

01

01

00

110

110

00

00

01

01

00

110

110

111

110

10

110

01

00

1

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

Á

111

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

Á

00

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

Á

00

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

00

00

01

01

00

110

110

00

00

01

01

00

110

110

111

110

10

110

01

00

1

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

Á

111

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

Á

111

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

Á

111

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

111

110

10

110

01

00

1

111

110

10

110

01

00

1

00

00

01

01

00

110

110

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

Á

00

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

System Overview

111

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

Á

111

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

Á

111

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

111

110

10

110

01

00

1

111

110

10

110

01

00

1

00

00

01

01

00

110

110

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

Á

00

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

4

00

111

Á

4

00

Á

4

01

Á

5

01

Á

4

00

Á

6

110

Á

4

110

Á

7

4

00

Á

8

00

Á

4

01

Á

9

01

Á

5

00

Á

0

110

5

110

Á

1

Á

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

110

Á

Á

Issue 1 04/99

111

110

10

110

01

00

1

00

00

01

01

00

110

110

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

110

Á

Á

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

1

Á

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

1

Á

Á

111

110

10

110

01

00

1

111

110

10

110

01

00

1

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

1

Á

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

1

Á

Á

00

Á

00

Á

01

Á

01

Á

00

Á

110

Á

110

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

1

Á

Á

00

00

01

01

00

110

110

111

110

10

110

01

00

1

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

1

Á

Á

111

Á

110

Á

10

Á

110

Á

01

Á

00

Á

1

Á

00

Á

00

Á

01