Page 1

Academic

Courseware

Animation

by Joyce Ryan

Page 2

Page 3

Copyright 2001-2004 Corel Corporation. All rights reserved.

The content of this document and the associated Corel Painter software are the property of Corel Corporation

and its respective licensors, and are protected by copyright.

Corel, the Corel logo, Corel Painter, and Corel PHOTO-PAINT are trademarks or registered trademarks of

Corel Corporation and/or its subsidiaries in Canada, the U.S. and/or other countries. Adobe and Photoshop are

registered trademarks of Adobe Systems Incorporated in the United States and/or other countries. Apple, Mac

OS, and Macintosh are registered trademarks of Apple Computer, Inc., registered in the United States and

other countries. QuickTime is a trademark used under license. QuickTime is a registered trademark of Apple

Computer, Inc. in the United States and other countries. Indeo and Intel are registered trademarks of Intel

Corporation. Windows is a registered trademark of Microsoft Corporation in the United States and/or other

countries. Netscape Navigator is a registered trademark of Netscape Communications Corporation in the U.S.

and other countries. TARGA is a registered trademark of Pinnacle Systems, Inc., registered in the U.S. and

other countries. Cinepak is a registered trademark of Radius, Inc. Wacom is a registered trademark of Wacom

Company, Ltd. Other product and company names and logos may be trademarks or registered trademarks of

their respective companies.

Academic Courseware

Page 4

Page 5

Table of contents

Foreword . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . iii

Jargon 101: The Technical Terms Every Animator Needs to Know1

The Storyboard . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .15

Digital Ink and Paint Techniques . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .25

The Background Art. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .39

The Write-on . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .49

Saving and Exporting Movies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .55

Animating with Strokes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .65

Rotoscoping with Corel Painter. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .71

The Power of Scripting . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .79

3-D Effects . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .87

Vocabulary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 97

Academic Courseware:

Joyce Ryan

i

Page 6

Academic Courseware:

Joyce Ryan

ii

Page 7

Foreword

In 1972, I got my first taste of “computer art.” My husband John and I

were students at the Rhode Island School of Design. John got involved

in an experiment at the Rhode Island School of Design, and Brown

University had started to encourage art students to collaborate with

computer science students. John was led into a frigid room that housed

gigantic machines that seemed to eat punched cards for fuel. Most of the

artists in the program quickly lost interest. The thought of feeding

punch cards in, one at a time, to plot out a black-and-white drawing

made of alphanumeric characters didn’t seem all that appealing. John,

who was studying Graphic Design at the time and liked anything to do

with turning type into pictures, thought this might have some real

potential. He ended up using all of his allotted time and most of the

other artists’ time as well. In those days it cost several hundred dollars

an hour to use the computers.

Moving forward to the mid 1980’s. I was working with Washington

University to develop a program of study that would introduce artists to

computers. John and I were the only artists they had ever heard of who

had any involvement with computers. I was already going to attend

Siggraph, so I kept an eye out for some software that would meet the

needs of such an academic program. I saw the big 3-D modeling

systems, but was most impressed when I came across the first “paint”

system I’d ever seen. It was by a small company called Time Arts, Inc.

and it used a pressure-sensitive tablet with a special graphics card that

allowed the computer to display 256 colors. Far beyond the punch cards

from college, I could now actually draw and paint with the computer,

and in color! This was the tool I needed to start my program at

Washington University. As excited as I was, that was about how

unimpressed the arts faculty were with the idea of drawing and painting

on a computer. My program got a lot of criticism for being “unnatural”

or superfluous. One or two brave souls came around, but mostly the

faculty could not imagine why anyone would want to try to make art

with a computer.

I threw myself into learning this software inside and out, and was

learning even more by teaching my students. This was the beginning of

the computer graphics program in the art school at Washington

University. The more I learned, the more I wanted to meet the people

Academic Courseware:

Joyce Ryan

iii

Page 8

who had written this wonderful software. I had ideas for tools I wanted

them to make especially for animators. My next stop was the Time Arts

offices in Santa Rosa, California, where I first met, among many talented

artists, programmers and engineers, John Derry, who was destined to

become one of the co-creators of Painter. The people I met were

pursuing a goal—to replicate natural media with a computer. I fell in

love with their work, made some of the best friends of my life, and

eventually joined the company in an 8-year relationship, first as a

software reseller, then eventually as an animation consultant, software

trainer, demo artist and interface designer. I wanted to take what I knew

about conventional animation techniques and apply it to the computer.

It has been my passion ever since.

Jump ahead again and it is now 2004 and I am teaching Digital Ink and

Paint at the Art Institute of Atlanta. I am demonstrating Corel®

Painter™ to my class. I ask my students how many of them remember

seeing the scene in “Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory” where the

children are shown lickable wallpaper. Willy Wonka excitedly tells them

to lick the wallpaper, that the strawberries taste like strawberries, the

pineapple tastes like pineapple, and the snozzberries taste like

snozzberries—but the children had never heard of or tasted

“snozzberries.” The snozzberries had to be magic. I then showed my

students the watercolor brushes in Painter that acted like watercolor, the

chalk that acted like chalk, and then the brushes that acted like nothing

they had ever seen before. The Image Hose that painted with donuts.

The brush that painted with metal. And how it could all be used to

make animation. For that moment we were all as excited as children

tasting “snozzberries” for the first time. The fruit not from a bush or a

tree, but from an inventor’s imagination!

I wish to thank my husband John for contributing so much of his

artwork and support while I was writing these chapters. I want to thank

my son Lucas for his comments and insight. I want to thank my

students at the Art Institute of Atlanta for letting me test my tutorials

on them. I want especially to thank all the good people at Corel who

supported this book and who continue to develop Painter, pushing the

envelope of what it can do. They just keep making it better—it must be

magic.

Joyce N. Ryan, 2004

Academic Courseware:

Joyce Ryan

iv

Page 9

Chapter 1

Always check to make sure you

are working at the right size before

starting any project. Check the preset

sizes in your editing software, or talk

with your video editor, film editor, Web

developer or service bureau.

Jargon 101: The Technical Terms Every Animator

Needs to Know

Before beginning an animation project, you must consider the final

format your work will be displayed in. Are you working for film, video,

or the Web? Will any of the animation frames ever need to be resized for

print? Setting the correct size, shape, and resolution for your project

from the start is critical to its success.

Typically, if you are working

for film and video, you might work at

720 x 486 pixels (standard NTSC

video). If you are making an animated

comp in QuickTime®, or an AVI to

run on your computer, 320 x 240

usually works well.

Storyboard panel formatted for television.

TV cut-off and safe titling

If you are creating animation for television or film, you must make sure

that your type is not cropped by the shape of the screen, and that

nothing vital in your image is lost. The rule of thumb for layout

purposes is to crop a 12-field layout, 1.5 inches all around for TV cutoff, and 2 inches around for title safe.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 1

Joyce Ryan

1

Page 10

A field guide or “graticule”

helps the animator plan a layout. 35mm film layout is based on a

proportion of 1:1.376 (known as the

Academy Ratio). This typically yields

a size of 12 x 8.72 inches. For

television, this format varies slightly.

Typically, an aspect ratio of 4:3

corresponds to the NTSC standard.

The degree to which TV cut-off crops

the field depends on the make, model,

and age of the TV set.

Tape an animation peg bar to

your scanner, so that all your drawings

are scanned in perfect alignment

(registration) to one another.

TV layout based on a 4:3 aspect ratio indicating TV cut-off and title safe for a

standard NTSC (National Television Standards Committee) television broadcast.

Scanning for animation

If you draw your animation by hand, you will have to scan it into Corel

Painter. Your drawing should be created at the correct dimensions

(width to height) for your animation. Ten seconds of animation at 30

frames per second can translate into 300 drawings if you create one

drawing for every frame of video. It is critical to scan efficiently to

handle that volume of artwork. If you are scanning in art to use as final

renderings in your animation, you will scan at 72 dpi in RGB at 720 x

486 for NTSC video. However, if you are scanning in to trace, reference,

or make a rough pencil test of your motion, get into the habit of

scanning at 72 dpi in grayscale, so that your files are small and scan

quickly. Depending on your drawings, you may even scan them in as

black-and-white line art; the drawings will look jaggy, but if you are

only using them as reference to trace from in Corel Painter, that is all

you need. This will give you files that take up the least amount of

storage space on your computer.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 1

Joyce Ryan

2

Page 11

Each scanner has a different

interface, so you may have to explore a

little to find the settings you need.

If you have to increase the size

of an image, the best place to do that is

on the scanner; blowing up a bitmap in

a software program is always a bad

idea.

“Paint” = Bitmaps, “Draw” = Vectors

Computers handle images in two ways: as bitmaps, or as vector images

(also known as object-oriented graphics). When working with objects

and vectors, the computer keeps a “display list” that describes a series of

points in space and their attributes.

What size should you work

at? That depends on your finished

product. Will the artwork ever be used

for other purposes? Remember, it is

always easy to make the image smaller,

but it is very difficult to make it

bigger.

The rough draft for the fish was done in Corel PHOTO-PAINT®. Once

the client approved it, the image was recreated with shapes so it could

easily be resized for various uses.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 1

Joyce Ryan

3

Page 12

Bitmaps are resolutiondependent. If you blow up pixels, they

just look more obvious.

The finished design created with vectors.

Unlike vector images, bitmaps cannot always be easily resized without

loss of quality.

Note what happens to the letters when they are blown up. It is all right

to reduce a bitmap, but it is almost never acceptable to enlarge one.

Understanding vectors

A vector is a mathematical description of a location in space; as such, it

has no actual size. Images described by vectors are resolutionindependent. They can be rendered at any size and maintain their image

quality. The image file only contains a list of vectors and display

properties, making vector-based (object-oriented) files very small

compared to bitmaps. Eventually, the file has to be converted to a

bitmap output. When it is sent to a printer, the raster image processor

Academic Courseware: Chapter 1

Joyce Ryan

4

Page 13

Vector-based graphics are

easy to resize with no loss of quality.

However, they tend to have a

somewhat flat graphic style to them. If

you want a painterly look, you will

not be satisfied with working only

with vectors.

(RIP) usually handles that task. The display adapter in your computer

interprets the image as a bitmap of pixels on your monitor. Some “Paint”

programs like Corel Painter and Adobe® Photoshop® let you import

vector graphics and turn them into bitmaps (“rasterize” them) so they

can be embellished with paint effects. Corel Painter combines the best of

both worlds by letting the artist work with both bitmaps and vectorbased objects.

An image like this one would be impossible to create with vectors.

Understanding bitmaps

Everything in graphics output eventually becomes a bitmap. Bitmap

files are large! They have to be—the computer must keep track of the

color values of every pixel that makes up the image, not just vectors and

attributes. Bitmaps are also resolution-dependent. If you blow up pixels,

they just look more obvious. To make a bitmapped image large and

smooth, you have to have a finer grid of pixels defining the image. For

best results, you must create your image at the correct resolution, or

higher.

A bitmap is a rectangular grid of dots used to describe an image. It has

four basic characteristics:

•Dimension

•Resolution

•Bit depth

• Color model

Academic Courseware: Chapter 1

Joyce Ryan

5

Page 14

Some software, games, and

Web sites will stipulate the ideal

settings for your monitor, so that you

can see the images as they were

intended.

Resolution

The word “resolution” can be used to describe different things.

Spatial resolution — describes the dimensions of an image in width

and height.

Color resolution — often referred to as “color depth” or “bit depth”;

refers to how many colors are available to define the image.

Scanner resolution — refers to the number of dots per inch (DPI). If

you have to enlarge an image, it should be done on the scanner and not

in Corel Painter. DPI is also used for the resolution of printers,

describing how many dots per inch the printer can apply to the paper.

Screen resolution — refers to the number of pixels per inch (PPI).

Computer monitors can be set for different screen resolutions. The

setting determines how many pixels the monitor can display. A large

monitor can accommodate a high setting. A small monitor may be easier

to see at a lower setting.

Line frequency — also known as “screen frequency”; refers to the

number of lines per inch (LPI) that a halftone screen uses to break down

a continuous tone image into printable dots for reproduction on a

printing press. Low line frequency (large dots) is used for porous papers

like newsprint. Coated stock can hold more detail and can take a higher

line frequency. Always ask your service bureau what LPI you should be

working at.

So how do we understand all

these different references to resolution?

It’s all about dots—the dots just come

in different flavors! Whenever people

are talking about “resolution,” they

are talking about a grid of dots that

are assigned or mapped to a given

space, usually measured in inches or

centimeters. The more dots you put in

an inch, the more detailed the image

will be—it will have a “higher rez.”

An image must be broken into dots with a halftone screen to print on a

commercial printing press.

When you are creating an animation with Corel Painter, consider

• the type of animation you are producing,

Academic Courseware: Chapter 1

Joyce Ryan

6

Page 15

The PPI doesn’t tell you

anything about the actual size of the

grid.

PC’s typically default to 96

ppi, and Macintosh® computers

default to 72 ppi. Television sets

default to 72 ppi. A liquid crystal

display (LCD) screen may be set

brighter than a cathode ray tube

(CRT) one. Apple® computers

typically default to a brighter screen

gamma than PC’s. When designing

for the Web, developers typically test

their work on both platforms. If you

are working in video, you will also

want to look at your work on a video

monitor.

• the requirements of any systems that will process the animation

when you are finished with it in Corel Painter,

• the final delivery medium of the animation (video, film, Web, CD,

QuickTime, AVI, etc.).

Dimensions or spatial resolution

Bitmaps have two dimensions. They are grids containing picture

elements (pixels). The dimensions of a bitmap are described by the

number of pixels the bitmap is high and the number of pixels the

bitmap is wide.

spatial resolution = width x height

The spatial resolution of a bitmapped image is based on how many

pixels in the grid make up each unit of measurement. In Corel Painter,

you are working in pixels per inch (PPI). In other words, if you have a

one-inch grid, how many pixels is this grid broken up into: 72, 96, or

maybe 300? Which would look sharper and have more detail, the 1”

grid described by 76 pixels or the 1” grid described by 300 pixels?

Compare resolution and zooming

Look at an image file and note its resolution. Let’s say it is 720

x 486 pixels and has a resolution of 72 ppi. Zoom in on it

200%. It looks twice as big, but it is still only 720 x 486

pixels. You have made the pixels of the grid look bigger, but

you have not added more pixels to the grid, so the resolution

has not increased.

Increase screen resolution

Increase the resolution of your monitor to see what happens.

The icons on your desktop look smaller. Why?

Color resolution

A bit (binary digit) can describe two states: on and off, black and white,

0 and 1, etc. If 1 bit = 2 colors, 2 bits give you 4 colors, and 8 bits give

you 256 colors. That’s 2x2x2x2x2x2x2x2 = 256, or 2 to the power of 8

8

(2

). At 24 bits of information, you have over 16.7 million colors to

work with. Each pixel is made of three components: Red, Green and

Blue, or RGB for short. We have 8 bits of color for each component, or

256 levels of Red, 256 levels of Green and 256 levels of Blue. Multiply

256 x 256 x 256, and you get 16,777,216 colors. You now know why

Corel Painter and other software programs display RGB in values of 0 to

255. If each of the three RGB colors has 8 bits, the image needs 24 bits

Academic Courseware: Chapter 1

Joyce Ryan

7

Page 16

There is an important

difference between displayable and

definable color. If you have 24 bits of

color, you can define over 16.7 million

colors. If your display is set for 1024 x

768, you only have 786,432 pixels,

so you can only display 786,432 colors

out of a possible 16.7 million.

for all the colors. But what does it mean when you are working with a

32-bit image? What are those other 8 bits for, if they’re not needed to

display the RGB colors? They are used for transparency. Certain file

formats support “alpha channels.” Having an 8-bit alpha channel means

that you can have 256 levels of transparency in your image. Color

resolution, or bit depth, affects not only the file size (fewer colors means

fewer bits), but also the smoothness of the color gradations in an image.

This image has excellent color resolution.

Here is the same image using only 60 colors (it has decreased color depth). Look closely

at the green boat and the clouds; notice how the colors are simplified. This effect is called

“posterization.”

Academic Courseware: Chapter 1

Joyce Ryan

8

Page 17

A common trick used to save on file size is to lower the color resolution

of an image. Depending on the image, it can be hard to tell the

difference between an 8-bit image and a 24-bit image on the screen.

This TIFF file takes up 600 KB of storage space.

This GIF file takes only 60 KB of storage space.

Compare output colors

Let’s look at an image at different bit depths in Corel Painter

using the GIF file format.

1 In Corel Painter, open a new file, 100 x 100 pixels at a resolution of

72 ppi.

2 Set the paper color to pure red in the RGB values by setting the red

to 255 and the green and blue to 0.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 1

Joyce Ryan

9

Page 18

NTSC (National Television

Standards Committee) is often

jokingly referred to as “Never Twice

the Same Color.” Video can’t display

the pure bright red you see on a

computer monitor. That is why you

want to look at your work on an

NTSC monitor if you are working for

video. Corel Painter has a special filter

that ensures your animation will be

compatible with both NTSC for the

U.S. and Pal (Phase Alternation by

Line) for European video systems.

When you have finished

making a movie, you can also run a

script in Corel Painter that will apply

the NTSC filter and convert your

movie to video-safe colors.

3 Go to Effects > Tonal Control > Video Legal Colors. Choose NTSC.

Notice how different the red looks in NTSC.

Visually reduce the number of colors in an image

1 Choose File > Save As and name your image file. Choose the GIF file

format, and click Save. Click OK to dismiss the layer warning, if

displayed.

2 In the Save As GIF Options dialog box, in the Number of Colors

area, choose 256 colors. In the preview window, the image appears in

256 colors.

3 Change the number of colors to 128. In the preview window, the

image appears in 128 colors. Continue reducing the number of colors

Academic Courseware: Chapter 1

Joyce Ryan

10

Page 19

in the graphic until you find the minimum number of colors

necessary for adequate display of your image on a Web page.

4 Choose an Imaging Method. Choose Quantize To Nearest Color if

you want Corel Painter to look at each pixel for which it doesn’t have

the exact color and pick the nearest color for it from the available

colors. Choose Dither Colors if you want Corel Painter to apply a

pattern to the colors chosen to generate a more accurate, less banded

result. In this case, Corel Painter will approximate the color of a

larger area of the image, rather than individual pixel colors.

5 You can now either save the graphic to use it on a Web page, or

return to Corel Painter to continue working on the image.

Resolution for video

In Corel Painter, when we start a new file, we see a dialog box that

requires us to enter a resolution in pixels per inch (PPI), or pixels per

centimeter. These pixels represent the number of blocks per inch making

up the grid of the bitmap. In video, the default screen resolution is 72

ppi. In addition, it is critical to know the width and height, or spatial

resolution necessary for the format you are working in.

Resolution for print

The RGB model can describe 256 levels of gray. Remember those gray

scales you did? How hard it was to create a gray scale with ten steps,

with twenty? Look at this grayscale strip—it is made of 256 levels of

gray. Can you tell the difference between all 256 shades of gray?

Most job printing presses can’t reproduce much more than 100 levels of

gray. Fine printers can do better if they use top quality materials and

papers, and highly controlled press conditions.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 1

Joyce Ryan

11

Page 20

Create a grayscale gradient

In Corel Painter, open a new file, 640 x 100 pixels at a

resolution of 72 ppi. Fill it with a grayscale gradation from

white to black. How many shades of gray can you see? Zoom

in on the gradient and examine it closely.

If you have your own printer

(ink-jet, laser, etc.), you should know

the printer DPI. If you don’t, check

your printer documentation or the

printer properties, or check with the

manufacturer. If you are using a

service bureau, they should tell you

what LPI to work at—ask! If they

don’t know, use a different service

bureau!

The rule of sixteen

Let’s say you want to print out your storyboard for a big client

presentation. There will be several people in the room and you want it to

look good from a distance and also upon close examination. A highquality look is important to impress the client. You created the

storyboard at 72 ppi, and it looked fine on your monitor. When you

printed it out, it looked awful! What happened? There weren’t enough

pixels per printed dot to give you a good-looking print. You need higher

resolution for print than you do for video. How do you find out how

much higher?

You already know it is possible to display 256 levels of gray in RGB.

Now you need to know the highest screen frequency (LPI) you should be

working at, given the capabilities of your printer. To arrive at the LPI

value, divide your printer DPI by 16 and multiply by 2. Here is a simple

example. My ink-jet printer has a resolution of 1440 dpi. If I divide that

by 16, 1440 ÷ 16 = 90. The rule of thumb is that I need 2 pixels per

printed dot to get a nice-looking image from my printer. I multiply 90 x

2, and set my resolution at 180 ppi. This should give me a full range of

tones and a beautiful print on photo glossy paper from my ink-jet

printer.

There is no LPI to worry about in video. Video defaults to 72 pixels per

inch. The important thing to know is the spatial resolution—the size of

the image as measured by its width and height. The screen resolution is

going to default to 72 ppi for video and the Web, but you need to know

the spatial resolution of your final output, in order to create your

animation at the correct dimensions and aspect ratio (the ratio of width

to height).

Academic Courseware: Chapter 1

Joyce Ryan

12

Page 21

Use photo quality paper for

high-resolution printing. It has a

coating that enables it to handle more

color and detail than plain paper.

This printer has a maximum resolution of 600 dpi.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 1

Joyce Ryan

13

Page 22

Academic Courseware: Chapter 1

Joyce Ryan

14

Page 23

Chapter 2

The Storyboard

There are two types of storyboards: the production guide and the

presentation board. A good presentation board helps you sell the client

on your idea. It should communicate the look and feel of the animation.

Presentation board created in Corel Painter using Watercolor variants

and the Sargent Brush from the Artists category.

The production storyboard serves as a visual road map for the

production crew, making it clear how the animation will work. It should

include camera angles, audio cues, zooms and transitions.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 2

Joyce Ryan

15

Page 24

Box and arrows indicate zooming out from a tight close-up.

Created using fills and layers in Corel Painter.

Blur filters were used to create shadow masks.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 2

Joyce Ryan

16

Page 25

Working out a detailed

storyboard in advance of production

helps predict the costs involved in the

production. The producer may use the

storyboard to estimate costs prior to

starting production.

This storyboard for “Mission Health” was created using the

Sargent Brush from the Artists category in Corel Painter.

Assignment 1

Storyboarding a 30-second TV commercial for a new radio show

The client wants something memorable that will help establish a brand

for a new radio show that will be competing with drive-time talk radio.

The show will offer an alternative to the incessant chatter of talk radio

by providing long uninterrupted blocks of music interspersed with

upbeat or funny stories. The radio station is broadcasting in areas with

heavy traffic and long commutes. The broadcast format is aimed at

commuters suffering through the stress of traffic, so the station wants to

communicate an image that will attract its target demographic group—

25- to 38-year-olds whose tastes have been formed by popular culture.

Your job is to come up with a concept that addresses the needs of your

client in an entertaining and memorable fashion. You have one week to

get a storyboard together to impress the client and win the job.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 2

Joyce Ryan

17

Page 26

1 In Corel Painter, create a new file. Set your image size to 720 x 486.

(D1 NTSC uses a spatial resolution of 720 x 486 at 72 ppi.)

2 Set the resolution to 180 ppi. The storyboard panels have to be

printed out in color for a presentation to the client and the

advertising agency for their initial reaction. Therefore, it is a good

idea to roughly double the resolution to 150-180 ppi, depending on

your printer. This will yield a printed panel that is 10 inches wide by

6.75 inches high.

3 Always name your files according to the job you are working on, and

keep all the files involved with that job in one folder. In this case,

name the file Radio_Panel_1.rif and save it in a folder called

Radio_Spot.

4 Pick a tool you like sketching with. Personally, I like the Scratchboard

Tool from the Pens category. Experiment with pencils, pens, charcoal

and chalk to find the tools you are most comfortable sketching with.

There is no “right” tool. If you are painting over a scanned image,

you are ready to go.

5 Once you are happy with the sketch, you are ready to begin working

with watercolor. Corel Painter automatically creates a new layer for

watercolors, so you don’t have to worry about painting over your

lines.

6 Try laying in a wash of color using the Soft Camel brush variant.

Clean up unwanted paint with the Eraser Dry brush.

7 When you are happy with your watercolor, dry the layer and add

another layer for more detail. Try colored pencils on this layer to add

crispness and finer detail.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 2

Joyce Ryan

18

Page 27

The more you work with

Corel Painter, the more you will

develop your own techniques.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 2

Joyce Ryan

19

Page 28

Academic Courseware: Chapter 2

Joyce Ryan

20

Page 29

Academic Courseware: Chapter 2

Joyce Ryan

21

Page 30

Academic Courseware: Chapter 2

Joyce Ryan

22

Page 31

These storyboards were created using the Watercolor brushes in Corel

Painter. Before Corel Painter, the artist, John Ryan of DAGNABIT!,

says he would have used markers on paper. What he especially liked

about using the Watercolor brushes in Corel Painter was that they left

his lines undisturbed: “Painter gave me a very facile watercolor look

without the fuss and muss of the real thing.”

Academic Courseware: Chapter 2

Joyce Ryan

23

Page 32

Academic Courseware: Chapter 2

Joyce Ryan

24

Page 33

Chapter 3

Digital Ink and Paint Techniques

Once your storyboard is complete, it is time to create the art for the

animation. You want to create the art as efficiently as you can, and that

takes planning. Reusable elements, color palettes, naming conventions,

and file folder structure should all be thought out before creating any of

the final artwork.

The following is a typical production workflow for a 30-second

commercial:

• Create model sheets for all the characters.

• Read the audio track for timing.

• Create an exposure sheet.

• Rough out the animation.

• Complete the inbetweening and backgrounds.

• Pencil-test the animation.

• Clean up and ink the animation.

• Paint the animation.

• Put the finished art together with audio.

Creating model sheets

The purpose of a model sheet is to give as much visual information

about the construction of the character as possible. This is especially

critical if other animators will be working with your characters. They

will use your model sheet as a guide to drawing the characters. It is

essential in any animated production for the animator to stay “on

model.” The characters must be consistent from scene to scene. A good

model sheet will give an indication of the character’s personality and

what the character should look like through a variety of expressions. A

full turn of the character helps to visualize it as a three-dimensional

object.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 3

Joyce Ryan

25

Page 34

Simplifying the character and breaking it down to show how it is constructed helps

the animators to maintain the proportions and volume of the character.

The model sheet serves as a reference for the animators. It is critical they stay “on

model” so the character doesn’t lose its original look and feel.

Assignment 2

Creating a model sheet for your characters

Using a pressure-sensitive stylus, start sketching with a brush variant

that feels comfortable to you. Experiment with a number of brushes and

variants until you find the one that fits your sketching style.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 3

Joyce Ryan

26

Page 35

It is a good idea to start any

sketching session by going to Corel

Painter IX > Preferences > Brush

Tracking (Mac OS®), or Edit >

Preferences > Brush Tracking

(Windows®), and setting the

sensitivity of your pen. This is

especially helpful if you have a light

touch, or if you prefer different settings

with different variants. Some artists

even like to tape sketch paper to their

tablets so they feel the “tooth” of the

paper.

The first sketch was created with Tapered Artist Chalk 10 from the Chalk brush

category. The second sketch was created with Fine Detail Air 3 from Airbrushes.

Once you have your sketches, it is time to clean them up and create the

model sheet. You can use layers, or even better, clone your drawing.

1 Clone your drawing (File > Clone).

2 Choose Select > All.

3 Delete the image in the clone (press Delete or Backspace).

4 Toggle on the tracing paper by selecting Canvas > Tracing Paper, or

clicking the Toggle Tracing Paper button in the upper-right corner of

the image window.

5 Trace your sketch using the Pen tools from the toolbox.

6 In the property bar, enable the Stroke check box and disable Fill.

Clean up the drawings using the shape tools to get perfect curves.

Cleaning up a drawing with

shapes has several advantages: Your

characters can be easily resized, and

parts that move can be created on

separate layers and animated

separately without you having to

redraw the whole character. Shapes are

also easily converted to selections,

allowing you to add painterly effects.

7 Create a variety of expressions for your character that show a full

range of emotions.

8 Turn on the rulers and the guides (Canvas > Rulers > Show Rulers

and Canvas > Guides > Show Guides), and set guidelines for

Academic Courseware: Chapter 3

Joyce Ryan

27

Page 36

aligning your character in the front, side and back views. Use the

guides to line up the views of the character.

A complete turn-around of the character gives a sense of the character’s volume and

proportions. It is an invaluable aid to drawing the character from a variety of angles.

Most artists use reference

material as a starting point. Try using

a digital camera and the Cloning tools

in Corel Painter to create your

characters if your drawing skills are

not up to the task. The more you work

from life, the more your drawing skills

are bound to improve.

A good model sheet helps indicate the personality of a character by showing how that

character would experience a wide variety of emotions.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 3

Joyce Ryan

28

Page 37

Make a palette of colors that is

specific for the job, so you can stay

consistent from frame to frame. You

don’t want your characters changing

colors! You may also have an assistant

helping you, who will be working on

the same storyboard and will need to

use your palette.

Coloring your characters

Corel Painter offers an almost unlimited number of options to paint your

characters. Traditionally, animators inked their drawing onto clear

celluloid or acetate sheets called “cels.” These were inked on the front,

then turned over and filled in with special cel vinyl paint on the back.

This technique gave a flat matte finish to the paint and kept the ink line

intact. Color paints had to be mixed in quantity to assure not running

out. Remixing could cause the colors to shift before all the cels were

painted. Each color was labeled and keyed to a master painting for

reference. Many people were required to paint and, again, they all had to

stay on model. Corel Painter makes it easy to both “paint cels” and mix,

store and label your colors.

Create a custom color palette for painting your characters

1 On the Color Sets palette, click the palette menu arrow, and choose

New Empty Color Set.

2 On the Colors palette, choose a color from the Standard Colors or the

Small Colors display (the Hue Ring or the hue indicator). On the

Color Sets palette, click the Add Color To Color Set button.

3 On the Color Sets palette, double-click the color to get the Set Color

Name dialog box. Name each color to correspond to parts of your

character: “face,” “teeth,” “eyes,” “hair,” etc. To display the color

name, choose Display Name from the Color Sets palette menu.

4 Save your color set with the name of your character by choosing Save

Color Set from the palette menu. Anyone who has to paint the “cels”

now has the correct colors with which to paint the character.

5 Experiment with a variety of ways to mix your colors. Try sampling

colors from an image, using the Mixer palette and the Color Info

palette. There is no right or wrong method. Use the technique that

best fits your personal workflow.

Practice cel painting in Corel Painter

Cel painting is no longer limited to flat color. With the advent

of Paint programs like Corel Painter, the range of techniques

used to paint cels is limited only by your imagination.

Experiment with different styles to give your work a unique

look and feel.

1 Open a new file and copy one of your cleaned-up characters to the

file. Save the file and call it ColorRef.rif.

2 Drop the copied layer to the canvas.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 3

Joyce Ryan

29

Page 38

Keeping your line intact on a

separate layer lets you control the

integrity of your line. You may wish to

keep the line or not. You may also wish

to change the color of the line to match

the painting.

3 Select the black lines by using the Select > Auto Select > Image

Luminance command. Copy the lines and choose Edit > Paste In

Place to paste your lines on a new layer.

4 On the canvas layer, choose the Paint Bucket tool. Set the Fill to

Current Color on the property bar, and fill the drawing with the

appropriate colors. Depending on the tolerance and feathering

settings, your fill will antialias to the line.

5 Once the fills are complete, set up your lighting using Effects >

Surface Control > Apply Lighting. Set your lighting and remember

to save it! You now have a painted and shaded cel.

A frame of animation created by John Ryan of DAGNABIT! for the National

Black Arts Festival campaign.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 3

Joyce Ryan

30

Page 39

Experiment with the many

ways there are to mix color. There is no

right or wrong way. Corel Painter

allows many different approaches to

match your personal preferences.

Colors were mixed using the Mixer palette and the Color Info palette, and sampling

scanned watercolor studies.

Reading the audio track

If the character is to talk, the drawing of the character’s mouth must

synchronize with the dialogue. This process is called “lip synching.”

Although there are many references for creating lip synch, including

specialized software, it is critical for the animator to act out the dialogue

in front of a mirror. Acting out the dialogue helps the animator bring

out the personality of the character. Sometimes there is reference footage

of the actor who is doing the voice. The more the animator or actor is in

character, the better the reference will be.

The audio track has to be broken down and interpreted on an exposure

sheet. This “dope sheet” indicates where the parts of speech (phonemes)

occur frame by frame. Good lip synch is an art. Emphasis on specific

sounds works better when the action anticipates the sound by a few

frames.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 3

Joyce Ryan

31

Page 40

Create an exposure sheet or

“dope sheet” to track your audio and

match it to your animation.

Sample exposure sheet with indications for lip synch.

Create mouth positions for reference

Academic Courseware: Chapter 3

Joyce Ryan

A (“ehee”)

32

Page 41

B (“buh”)

C (“ss”)

Practice lip synching

Make a simple sock puppet. Practice making it talk believably.

Try to “speak” your dialogue with the puppet, videotape your

efforts and critique the results. How could you have

emphasized important sounds? Did you open the puppet’s

mouth on the vowels or the consonants?

Create a phoneme chart as a custom Image Portfolio

1 Photograph your mouth and chin forming basic phonemes: A, B, C,

D, E, F, G . . .

2 Display the Image Portfolio palette (Window > Show Image

Portfolio).

Academic Courseware: Chapter 3

Joyce Ryan

33

Page 42

Save your phoneme chart as

a custom Image Portfolio so you

always have reference for mouth

positions.

3 To create a new portfolio, click the palette menu arrow, and choose

Open Library.

4 In the Choose Image Portfolio dialog box, click the New Library

button.

5 In the New Image Portfolio dialog box, choose a location and enter a

name for your image portfolio. Click Save.

6 To add an image to the new image portfolio, select a layer, and do one

of the following:

• To cut the layer from the current document, drag the image from

the document window to the Image Portfolio palette using the

Layer Adjuster tool.

• To copy the layer, hold down Option (Mac OS) or Alt (Windows),

and drag the image from the document window to the Image

Portfolio palette using the Layer Adjuster tool.

7 In the Save Image dialog box, type a name for the image.

8 To use an image from the Image Portfolio, drag it from the Image

Portfolio palette to the document window.

Roughing out the animation

Once you have a good sense of when things have to happen and where

they hit on the audio track, you can start animating. Roughing out the

key poses for your animation is the next step. Some animators like to

animate “straight ahead,” creating each drawing in sequence. Most

animators find it easier to rough out the key poses, then create the inbetween drawings for those poses, and then test the motion and add or

subtract drawings where necessary. You may find yourself using a

combination of the two techniques.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 3

Joyce Ryan

34

Page 43

A rough key pose sketched in Corel Painter.

Inbetweening

Producing the drawings “in between” the key drawings is a skill unto

itself. Traditionally, one would place a key drawing onto a light box, the

next key drawing over it, and then another sheet of paper over that. On

the top sheet, the animator would figure out the position between the

two key drawings and sketch it. We can do something very similar in

Corel Painter using layers.

Once you have your key drawings, you can set them up as layers in a file

and draw the inbetweens. Insert a blank layer over the key drawings you

wish to inbetween, and draw the inbetween. By changing the opacity of

the layers it is easy to see the differences between the key drawings.

Changing the color of the lines also makes it easier to tell the difference

between the keys (you can select the lines using the Image Luminance

option and change the colors of the lines in each layer).

Practice inbetweening techniques using layers

1 Sketch your first key pose on a transparent layer.

2 Create a new layer and select a different contrasting color to sketch

with. Sketch the next key pose.

3 Create a new layer and, with another color, sketch the inbetween

using the key drawings as reference. Experiment with changing the

transparencies of the layers you are referencing.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 3

Joyce Ryan

35

Page 44

Example of inbetweening with layers in Corel Painter.

Drawing the inbetween using layers in Corel Painter.

Pencil-test your motion

1 Open a new file in Corel Painter, the same size as your inbetweens. In

the New dialog box, set the Picture Type to Movie, and set the

number of frames to match the number of inbetweens you have.

2 Paste your inbetweens into separate layers in your movie file.

3 On the first frame of your movie, shut off all layers except the one

you wish to have showing.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 3

Joyce Ryan

36

Page 45

4 Move to the next frame and turn on the next inbetween, turning off

everything else.

5 Repeat until you have an inbetween on each frame of your movie—

your layers have become frames.

6 Shut off all your layers.

7 Play back the movie to test your motion.

8 If your computer plays back too quickly, save your movie as an AVI at

a frame rate of 12 to 15 frames per second and view the AVI, or save

it as sequential TARGA® files to edit in a video editing program.

You can also slow the playback down by repeating the above process,

but instead of forwarding one frame, try forwarding two or three

frames for each drawing.

Pencil tests show you if you have enough inbetweens for fluid motion

from one pose to another. There are two ways to change the timing of

your animation: Adding more inbetweens will slow things down and

make the motion more fluid; holding each drawing for a longer period of

time will slow things down as well, but your motion will be choppier.

In video, you work with 30 frames per second. If you have 15 drawings

to describe that second, you hold each drawing for two frames. This is

referred to as shooting on “twos.” If you have a different drawing for

each frame, or 30 drawings per second, it is called shooting on “ones.”

Getting a feel for timing is a major part of becoming an accomplished

animator. Some motion looks better on twos, some on ones, some on

threes or more. There is a great deal of animation produced for the Web

and television that is designed with far longer holds than twos and that

still works quite well for the style of animation.

Tweening

Inbetweening is drawn by hand and takes drawing skill and practice.

“Tweening” can be done by a software program and can be a tremendous

labor-saving device. Learn how to use inbetweening and tweening to

their best advantage.

Practice tweening with Corel Painter

1 Open a new movie file at 320 x 240 pixels and 72 ppi, set for 30

frames.

2 Open another file, the same size but a single image.

3 Choose the Image Hose brush category. Open the Nozzle Selector in

the toolbox, click the selector menu arrow, and choose Load Nozzle.

Locate the Walkbrush.rif file, and click Open.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 3

Joyce Ryan

37

Page 46

4 Open the Nozzle Selector again, and click the selector menu arrow.

Choose Add Nozzle To Library, and save the nozzle.

5 From the Brush Selector bar menu, turn on Record Stroke.

6 Paint across the canvas with the Walkbrush.

7 Close the file (there is no need to save it).

8 Return to your movie. Choose Movie > Apply Brush Stroke To

Movie. Corel Painter applies your stroke to the frames of your movie.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 3

Joyce Ryan

38

Page 47

Chapter 4

A “pan” in animation refers

to moving a background painting

under a camera to create the illusion of

motion. In live action, the camera

would move, “panning” across a

background to create the same effect.

The Background Art

Now that the characters have been drawn, cleaned up and painted, you

need to create your backgrounds. Imagine your character is driving

along the road. How do you make the view outside his car window

appear to move? With a moving background.

Creating a moving background

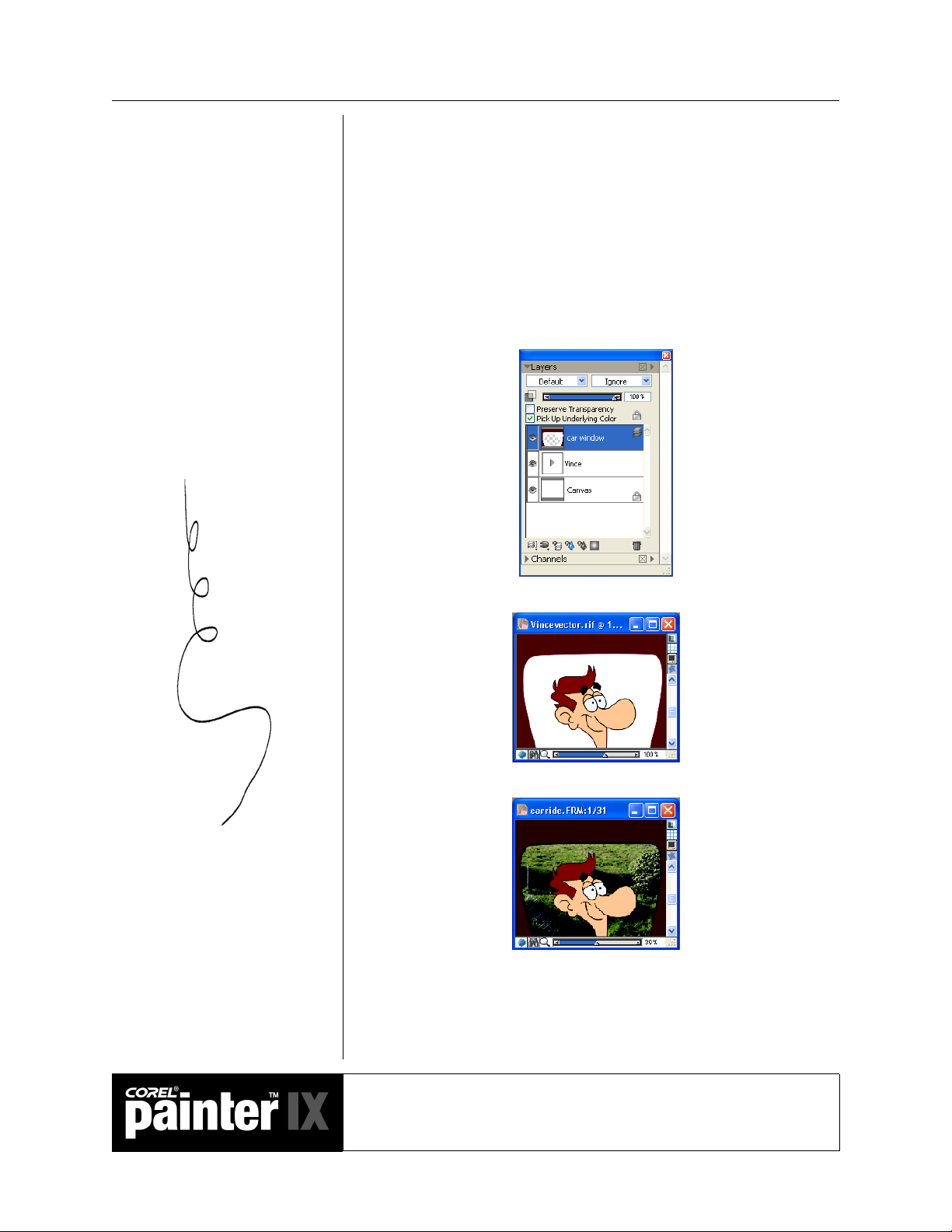

In the following example, the character of Vince is layered over a

background of the car interior. The car interior is a simple vector shape

that leaves a transparent opening to view the background through.

Next, the background art is created in a file that is much wider than the

window. This is referred to as a “pan cel.” We are going to move the

background across a movie. This will create the illusion of the character

moving through the background.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 4

Joyce Ryan

39

Page 48

A wide image for the background is the equivalent of a pan cel. It will be moved

through the scene to create the illusion of a moving background.

Create a moving background

1 Assume you are creating an animation that is 320 x 240 pixels at 72

ppi. Create a new file that is 640 x 240 pixels at 72 ppi.

2 Paint the background. Once the background is done, click Select >

All, and then Select > Float. This moves your painting up on a

separate layer above the canvas. Save this file and leave it open.

3 Create a new file, 320 x 240 at 72 ppi. In the New dialog box, under

Picture Type, click the radio button for movie, and set the frames to

30. Name the movie Backgrnd.frm.

4 Choose the Layer Adjuster tool from the toolbox, and enable the

Auto Select Layer check box on the property bar. Click on the

background layer in the document window and drag it into the first

frame of your movie. The background is automatically pasted on a

new layer.

5 Advance one frame in your movie by clicking the Step Forward

button on the Frame Stacks palette. The layer in the previous frame is

merged with the canvas. In the new frame, the layer is active. Use the

left arrow key to move the background the desired amount.

6 Repeat step 5 until you have completed the movie.

7 On the final frame, remember to either drop the background layer or

turn it off before you play back your movie.

8 Play the movie and watch your background move!

Academic Courseware: Chapter 4

Joyce Ryan

40

Page 49

Compositing

Next, we want to combine our character with the moving background.

This process is called “compositing.” To create the composite, start at

the first frame of the movie. Open the file that contains the elements

you wish to composite. Pull the elements into the movie file. Hold down

the Step Forward button until you reach the last frame of the movie,

then click Layers > Drop All.

Here is how the composite is created for the Vince movie. First, the

movie is set on frame 1. Next, the car window layer is moved into

position using the Layer Adjuster tool.

Then the Vince layer is positioned in the same way.

Then the background is added.

Once the layers are in place over the first frame of the movie, the frames

are advanced to the end and all the layers dropped.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 4

Joyce Ryan

41

Page 50

When the movie is played back, it appears that Vince is driving along in

his car. For added realism, Vince can be moved up and down a bit as

each frame is advanced to make his ride look a bit bumpy.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 4

Joyce Ryan

42

Page 51

You can choose different

lighting effects from the Corel Painter

library, or you can create your own

effects by defining brightness, distance,

color, and other characteristics. Once

you’ve produced a lighting effect you

like, you can save it in a library for

use with other images. Your computer

must have a math coprocessor to use the

Apply Lighting effect.

The importance of backgrounds

Creating beautiful backgrounds for animation is a career path in itself.

The background fills most of the screen. In many cases it does not move

(unlike our car window example), so your audience has plenty of time to

appreciate the quality of the background painting. In creating an

effective background, the mood, lighting and texture are critical.

The background painting sets the mood for the animation. What type

of emotional climate does the scene take place in? Is the setting bleak,

mysterious, joyful, cheery? How do you express that in your painting?

One way to express the mood is through lighting. Corel Painter gives

you several options for lighting your scene.

Apply lighting

Open Fields.rif. This scene shows a landscape in mid-afternoon

on a slightly hazy day.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 4

Joyce Ryan

43

Page 52

Photograph by Joyce Ryan, 2004.

1 Choose File > Clone. Click Select > All, and then press Delete or

Backspace to delete the image from the clone file.

2 Using a brush variant from the Cloners category, brush in the

background. For this example, I used the Watercolor Wash Cloner.

Set your opacity low so that you can build up the effect. Try

experimenting with several cloner variants.

3 Go to Effects > Surface Control > Apply Lighting. Experiment with

a variety of preset lighting effects. Try changing the light colors. Try

to create a sunny day, a cloudy, rainy day, a night-time look and dawn

breaking.

Applying a lighting effect to the background.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 4

Joyce Ryan

44

Page 53

Creating the effect of dawn breaking using lighting effects.

This background for a 30-second commercial was created using brush variants

from the Felt Pens and Watercolor categories in Corel Painter.

Animation background provided by DAGNABIT!

Academic Courseware: Chapter 4

Joyce Ryan

45

Page 54

Create background depth

Objects that are closer to you appear to move more quickly

than those far away. For this exercise, you will make it appear

that your background has depth. In this example, the image is

separated into two different layers, foreground and

background.

The foreground was selected and pasted into a new layer. The lake was cloned

to fill in the foreground.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 4

Joyce Ryan

46

Page 55

1 Create a background image with two layers, foreground and

background.

2 Open a new movie file, 640 x 480 at 72 ppi and 10 frames in length.

Using the Layer Adjuster tool, place the background layer onto the

first frame of your movie.

3 Press the left arrow key 4 times, forward to the next frame and repeat

until you reach the final frame. Drop the layer.

4 Next, place the foreground layer in the first frame of your movie.

Repeat step 2, only this time press the left arrow key 8 times within

each frame to make the foreground layer move faster.

5 Save your movie at different frame rates and play it back to see the

effect.

Assignment 3

Creating a moving background

Create a multi-level moving background based on a scene from your

storyboard. Pay close attention to the lighting, mood, texture and

perspective. Make sure the style of your background complements your

characters. Combine your characters with the background to complete a

short segment of your animated storyboard.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 4

Joyce Ryan

47

Page 56

Academic Courseware: Chapter 4

Joyce Ryan

48

Page 57

Chapter 5

The Write-on

Every animator at some point in his or her career is going to have to

create a “write-on.” A write-on is a word or an image being magically

written across the screen. In this chapter, we are going to explore several

techniques in Corel Painter for creating different styles of write-on.

We will create a write-on for the name of a radio station. My radio

station is called WHEW! 98.6 FM. I want to give the WHEW! a shiny

cloud-like 3-D effect that appears over a background of sky and softly

floating clouds.

Create the background

1 Open a new file, 720 x 486 at 72 ppi. Create a gradient from dark

blue to light blue for your sky and save it. Fill the canvas with your

gradient.

2 Choose Select > All, and then Select > Float. Name the new layer

Sky.

A write-on effect can be used

as an effective signature for a client’s

logo. It is also fascinating to watch a

drawing taking shape one step at a

time. This simple technique can be used

in a multitude of situations.

3 On a new layer labeled Clouds1, try using Airbrush variants to create

some clouds. I added some Motion Blur to the background (Effects >

Focus > Motion Blur) to smooth out my clouds and make it look like

there was a little breeze. You will be animating the clouds

independently, so make sure they are not cropped by the edge of the

image. You may want to be able to isolate your clouds as independent

selections for more flexibility.

4 On a new layer, create some smaller foreground clouds. Name this

layer Clouds2. Save your file in the RIFF format to preserve your

layers.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 5

Joyce Ryan

49

Page 58

Play the Clouds script to see how the sky and clouds were

created.

Create the text

1 Open a new file, the same size as your Sky file, and name it Whew.rif.

Click the Text tool in the toolbox, or press “T” on the keyboard to

activate the Text tool. Select a bold font and type “WHEW!.” Use

the Layer Adjuster tool to adjust the height and width of the word to

your liking.

Kerning refers to adjusting the

space between letters. Kern type for

television carefully. Type that looks

good in print does not always look good

in video. Video is made of interlaced

raster lines. If the type is thin, or has

fine serifs, those details can be lost

between the lines in video. It is usually

a good idea to make the tracking (the

space between the letters) a bit wider

for video than for print to make up for

the lower resolution of video.

2 On the Layers palette, click the palette menu arrow and select

Convert Text To Shapes. Click the arrow on the Whew! layer to see

the shapes.

3 Click on any shape that needs adjusting or kerning. Experiment with

the shapes of the letters. Customize the font by manipulating the

shapes. Adjust the kerning. When you are happy with the kerning

and overall letter spacing, choose Shapes > Convert To Selection.

Save your work.

Play the Whew script to watch how the text was created.

4 With a shape layer selected, click on Layers > Dynamic Plug-ins >

Bevel World. Experiment with the controls until you get a look that

you like.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 5

Joyce Ryan

50

Page 59

By moving the background

clouds only one “arrow key press” every

two frames (animating on twos), you

make them move more slowly than the

foreground clouds, which are moved

every frame.

5 Open your Sky.rif file. Open a new movie file, 720 x 486 at 72 ppi,

60 frames, and name it Skytitle.frm. Leave the default setting for the

layers of onion skin at 2, and the storage type at 24-bit color with 8bit alpha.

6 Copy the gradient layer from the Sky file and paste it into your

movie. Hold down the Step Forward button on the Frame Stacks

palette to deposit your gradient on each frame of your movie. When

you have finished, drop the gradient layer.

7 Copy your first cloud layer from the Sky file and paste it into the first

frame of your movie. You will be moving the clouds slowly across the

screen. You may also select individual clouds from your layer to paste

if you prefer.

8 Forward to the next frame and press the right arrow key on your

keyboard to nudge the clouds over. Press the Page Up key twice, then

nudge your clouds again. Repeat moving your clouds once for every

two frames of animation until you have animated your clouds moving

over the entire 60 frames. Drop the first cloud layer. (Animating on

“twos” will cause the background clouds to appear to be moving

more slowly than your foreground clouds.)

9 Close the file. Make a copy of the file under a new name for backup.

All changes you make to a movie file are automatically saved over

previous versions of the file; if you want to preserve the current

version of the movie, you need to save the file under a different name

before making any further changes.

Save versions of your

animation regularly. You cannot undo

once you forward a frame. You should

copy your frame stack with a new file

name and version number to keep track

of your work.

Create the write-on

1 Open the Skytitle.frm file, the Whew.rif file and the Sky.rif file. Click

the Fast Forward button on the Frame Stacks palette and make sure

you are on frame 60 of your animation.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 5

Joyce Ryan

51

Page 60

Timing is an important

consideration when creating any

animation. To create the WHEW!

write-on, you must establish the

following: 1) How long do you want it

to take? In this instance, I decided

that a 2-second effect would work

nicely. Therefore, I created 60 frames.

Video runs at 30 frames per second. I

wanted a very smooth effect, so I

animated on every frame. This is

called working on “ones.” 2) How

many times do you need to erase within

each letter? I looked at each letter and

calculated how many erasures I needed

to make.

2 Using the Layer Adjuster tool, pull your text on top of the final frame

of your animation. You may want to adjust the brightness and

contrast of your letters in relation to the sky by using Effects > Tonal

Control > Brightness/Contrast. I also chose to add a very thin drop

shadow from Effects > Objects > Create Drop Shadow.

3 On the Layers palette, make sure the Preserve Transparency check

box is disabled, and the Pick Up Underlying Color box is enabled.

Click back one frame to deposit your completed text on frame 60.

4 From the Erasers brush category, select the Eraser variant. Erase a

portion of the exclamation point. Click backwards to the next frame

and erase a little more. Repeat until you are back to frame one, and

your letters are completely erased. Delete the text layer. This is a

good time to play your animation! Close the movie file and save a

new version of your animation.

5 Reopen Skytitle.frm. Now let’s add a special effect. Make sure you are

on the final frame of the animation by clicking the Fast Forward

button on the Frame Stacks palette. Then, press the Page Down key

on your keyboard to move back to frame 59. From the F-X brushes,

select Fairy Dust. Make sure your current color is white. Experiment

with the size of your brush by painting a little, then using the Undo

function (Edit > Undo). When you are satisfied with the brush, paint

over the edge of the area that has just been erased from the letters in

the current frame. Page down and repeat until you reach frame 1.

Use the Page Up and Page Down keys to check your placement of

twinkles. Play your animation! Close the file and save a new version

of your animation.

6 Your are now ready to animate the final cloud layer. Reopen the

Skytitle.frm file. From your Sky.rif file, click on the Clouds2 layer.

Select all, and copy your clouds. Paste the clouds onto the first frame

of animation and animate them as you did the background layer.

Move these clouds a bit on every frame so they will move faster than

Academic Courseware: Chapter 5

Joyce Ryan

52

Page 61

the background clouds. When you reach frame 60, drop the cloud

layer or delete it before playing back your animation.

7 Play your animation. You may now export your animation in a

variety of formats.

Play Skytitle.mov to see the final animation.

Save your animation as sequential TARGA files

1 Choose File > Save As. The Save Movie dialog box appears.

2 Select the Save Movie As Numbered Files option.

3 In the Save Image As dialog box, choose a location where you want to

save the file, and choose the TARGA file format from the Save As

Type list. In the File Name box, enter a name for the first file. Since

you may wish to import these files into another program, it is

important to name and number them properly. The safest technique

is to follow the convention of limiting your file name to 8

alphanumeric characters and your extension to 3 letters. For the

Skytitle animation, try skya001.tga—“sky” describes the animation,

“a” is the version, and “001” allows the creation of sequential files

from 1 to 999. You must always begin or end the filename with a

number with sufficient zeroes to accommodate the length of your

animation.

4 Click Save. All frames of the animation are automatically saved and

numbered as sequential files.

Saving your animation as

sequential TARGA files has several

advantages. The TARGA format is a

common one used for video and is easily

imported into video editing and

compositing programs. The TARGA

format will preserve alpha channel

data, also making the images easier to

composite. Corel Painter allows you to

import sequentially numbered

TARGA files into a new Corel

Pai nt er m ov i e f il e .

Academic Courseware: Chapter 5

Joyce Ryan

53

Page 62

Academic Courseware: Chapter 5

Joyce Ryan

54

Page 63

Chapter 6

Saving and Exporting Movies

Once your movie is finished, you can save it or export it in various file

formats. In this chapter, you will find out about the different saving and

exporting options you have for your movie.

Corel Painter provides several options for saving and exporting your

finished movies. Some file formats (such as QuickTime and Video for

Windows) have compression options available.

Exporting a single image from a movie

You can export a single frame from your movie as a separate image.

Export a single image from a movie

1 Display the frame you want to export in the image window. You can

click on the frame thumbnail in the Frame Stacks palette to display

the frame.

The word “codec” comes from

combining the words “compression”

and “decompression.” A codec is any

technology for compressing and

decompressing data. Codecs can be

implemented in software, hardware, or

a combination of both. Some popular

codecs for computer video include

MPEG, Indeo® and Cinepak®.

2 Choose File > Save As. The Save Movie dialog box appears. Select

Save Current Frame As Image, and click OK.

3 In the Save Image As dialog box, choose a location and file format,

enter a name for the file, and click Save.

Exporting movies as QuickTime movies

You can export a movie as a QuickTime movie on either the Macintosh

or the Windows platform. QuickTime supports different compression

schemes (codecs). The following descriptions of the main compression

options should help you choose one; however, you’ll probably want to

experiment with different compressors and settings to identify the best

settings for your work. You may also have additional compression

methods available depending on your hardware.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 6

Joyce Ryan

55

Page 64

The compression ratio is inversely proportional to image quality. The

Quality slider allows you to set an optimum level between the amount

of compression and image quality. For most work in Corel Painter, you’ll

want Quality set to High.

Animation

This compression method works well with areas of continuous tone. If

you set Quality to Best and make every frame a key frame, this

compressor is lossless. For most Corel Painter animations, this

compressor is a good choice.

Cinepak

This method produces acceptable motion and image quality at

remarkably small file sizes. It is the preferred format for CD-ROM

delivery and transfer across the Internet. Cinepak can take a long time

to compress, and it can be difficult to find the best compression settings

for certain image types and frame rates.

Graphics

Codecs make use of different

techniques to compress images. Some are

“lossy,” meaning that they lose data to

make the files smaller. The JPEG

format is lossy. This is a great format

for the Web, allowing you to choose the

amount of loss you are willing to

accept. However, you should never save

a JPEG twice. Each time the file is

resaved, it will lose more data. Be

aware of whether you are saving your

work with lossy or lossless compression

and choose wisely.

This method is limited to 256 colors. It compresses the file at a greater

ratio than the Animation compressor, but does not play as quickly.

None

With this setting, no compression is used, so the images retain all of

their quality. With a large frame size, some computers might not be fast

enough to play at a high frame rate.

Photo-JPEG

JPEG is an international standard for image compression. It allows high

compression ratios while maintaining excellent image quality. However,

it does not play at high rates.

Video

This method is designed for recording and playing back digitized video

at high rates. Because of the spatial compression method it uses, the

Video compressor does not provide great results for images with large

areas of continuous tone, such as those in most animations.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 6

Joyce Ryan

56

Page 65

Export a Corel Painter movie as a QuickTime movie

1 Choose File > Save As.

2 In the Save Movie dialog box, enable the Save Movie As QuickTime

option.

3 In the Enter Movie Name dialog box, choose a location, enter a name

for the file, and click Save.

4 In the Compression Settings dialog box, choose a compression

method from the pop-up menu. Specify the options you want.

Exporting movies as AVI movies (Windows)

If you are using a Windows system, you can export your movie as an

AVI m ov ie . AV I, li ke Qu ic kTi m e, supports various compression

schemes. The most common options are explained below. Again, you

will probably want to experiment with different compressors and

settings to identify the best settings for your work.

Cinepak Codec By Radius

This method produces acceptable motion and image quality at

remarkably small file sizes. It is the preferred format for CD-ROM

delivery and transfer across the Internet. Cinepak takes a long time to

compress, and it can be difficult to find the best compression settings for

certain image types and frame rates.

Intel® Indeo Video R3.2

This method is capable of full-motion playback on systems with a

hardware compression accelerator.

Microsoft Video 1

This method is designed for recording and playing back digitized video

at high rates.

Full Frames (Uncompressed)

This method uses no compression, so the images retain all of their

quality. With a large frame size, some computers might not be fast

enough to play at a high frame rate. This is the preferred format for

transferring Corel Painter movies to AVI-editing applications.

Academic Courseware: Chapter 6

Joyce Ryan

57

Page 66

Export a Corel Painter movie as an AVI movie

1 Choose File > Save As.

2 In the Save Movie dialog box, enable the Save Movie As AVI option,

and specify the number of frames per second.

3 In the Enter Movie Name dialog box, choose a location, enter a name

for the file, and click Save.

4 In the Video Compression dialog box, choose a compression method

from the Compressor pop-up menu. Specify the options you want.

For some compression methods, you can click the Configure button

to specify additional options.

Working with numbered files

Corel Painter supports importing and exporting numbered files.

Numbered files are any series of files that are the same size and

resolution, and that are named following a specific style, which includes

a number at the beginning or at the end of each filename. For example,

the first frame might be called Movie001, the second frame Movie002,

and so on. When you export a movie as numbered files, you can import

the numbered files into an application that may not support other movie

formats.

When exporting, you specify the filename for the first file. You must

include zeroes so that all numbered files have the same number of digits.

For example, if you are creating numbered files from 1 to 24, include