Page 1

Newton 2.0 User Interface

Guidelines

Addison-Wesley Publishing Company

Reading, Massachusetts Menlo Park, California New York

Don Mills, Ontario Wokingham, England Amsterdam Bonn

Sydney Singapore Tokyo Madrid San Juan

Paris Seoul Milan Mexico City Taipei

Page 2

Apple Computer, Inc.

© 1996, 1994 Apple Computer, Inc.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be

reproduced, stored in a retrieval

system, or transmitted, in any form

or by any means, mechanical,

electronic, photocopying, recording,

or otherwise, without prior written

permission of Apple Computer, Inc.,

except to make a backup copy of

any documentation provided on

CD-ROM. Printed in the United

States of America.

No licenses, express or implied, are

granted with respect to any of the

technology described in this book.

Apple retains all intellectual

property rights associated with the

technology described in this book.

This book is intended to assist

application developers to develop

applications only for Apple-labeled

or Apple-licensed computers.

Every effort has been made to

ensure that the information in this

manual is accurate. Apple is not

responsible for printing or clerical

errors.

Apple Computer, Inc.

1 Infinite Loop

Cupertino, CA 95014

408-996-1010

Apple, the Apple logo, APDA,

AppleLink, AppleTalk, LaserWriter,

Macintosh, and Newton are

trademarks of Apple Computer, Inc.,

registered in the United States and

other countries.

Balloon Help, Espy, Geneva, the

light bulb logo, MessagePad,

NewtonScript, Newton Toolkit, New

York, QuickDraw, and System 7 are

trademarks of Apple Computer, Inc.

Adobe Illustrator and PostScript are

trademarks of Adobe Systems

Incorporated, which may be

registered in certain jurisdictions.

FrameMaker is a registered

trademark of Frame Technology

Corporation.

Helvetica and Palatino are

registered trademarks of Linotype

Company.

ITC Zapf Dingbats is a registered

trademark of International Typeface

Corporation.

Simultaneously published in the

United States and Canada.

LIMITED WARRANTY ON MEDIA

AND REPLACEMENT

ALL IMPLIED WARRANTIES ON

THIS MANUAL, INCLUDING

IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF

MERCHANTABILITY AND FITNESS

FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE, ARE

LIMITED IN DURATION TO NINETY

(90) DAYS FROM THE DATE OF THE

ORIGINAL RETAIL PURCHASE OF

THIS PRODUCT.

Even though Apple has reviewed this

manual, APPLE MAKES NO

WARRANTY OR REPRESENTATION,

EITHER EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, WITH

RESPECT TO THIS MANUAL, ITS

QUALITY, ACCURACY,

MERCHANTABILITY, OR FITNESS

FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. AS A

RESULT, THIS MANUAL IS SOLD “AS

IS,” AND YOU, THE PURCHASER,

ARE ASSUMING THE ENTIRE RISK

AS TO ITS QUALITY AND

ACCURACY.

IN NO EVENT WILL APPLE BE

LIABLE FOR DIRECT, INDIRECT,

SPECIAL, INCIDENTAL, OR

CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES

RESULTING FROM ANY DEFECT OR

INACCURACY IN THIS MANUAL,

even if advised of the possibility of such

damages.

THE WARRANTY AND REMEDIES

SET FORTH ABOVE ARE EXCLUSIVE

AND IN LIEU OF ALL OTHERS, ORAL

OR WRITTEN, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED.

No Apple dealer, agent, or employee is

authorized to make any modification,

extension, or addition to this warranty.

Some states do not allow the exclusion

or limitation of implied warranties or

liability for incidental or consequential

damages, so the above limitation or

exclusion may not apply to you. This

warranty gives you specific legal rights,

and you may also have other rights

which vary from state to state.

ISBN 0-201-48838-8

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9-MA-0099989796

First Printing, May 1996

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Newton 2.0 user interface guidelines / Apple Computer, Inc.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 0-201-48838-8

1. User interfaces (Computer systems) I. Apple Computer, Inc.

QA76.9.U83N49 1996

005.265—dc20 96-20168

CIP

Page 3

Contents

Figures xiii

Preface

Chapter 1

About This Book

Who Should Read This Book xxi

What’s in This Book xxii

Related Books xxii

Visual Cues Used in This Book xxiii

Developer Products and Support xxiii

Newton and Its Users

Understand Newton 1-1

Know Your Audience 1-2

What People Do With Newton 1-3

Accessibility 1-3

Observe Basic Human Interface Principles 1-4

Metaphors 1-4

Direct Manipulation 1-6

Feedback 1-7

See and Point 1-7

Consistency 1-7

User Control 1-8

Forgiveness 1-8

Stability 1-9

Aesthetic Integrity 1-9

Design for the Newton System 1-10

Observe the Built-In Applications 1-10

Use the Common Pool of Data 1-10

Keep Applications Simple 1-11

xxi

1-1

iii

Page 4

Use Screen Space Wisely 1-11

Check the Screen Size 1-11

Involve Users in the Design Process 1-13

Define Your Audience 1-13

Analyze Tasks 1-13

Build Prototypes 1-14

Observe Users 1-14

Ten Steps for Conducting a User Observation 1-15

Chapter 2

Container Views

How Views Look 2-3

View Controls 2-3

View Title 2-4

View Border 2-6

Matte Border 2-6

Striped Border 2-7

Wavy Border 2-7

Plain Border 2-8

Drop Shadows 2-8

View Fill 2-9

Main Views 2-9

Title or Folder Tab 2-10

Primary Controls and Status Bar 2-11

Separator Bars 2-11

The Main View’s Border 2-13

Auxiliary Views 2-14

Slips 2-15

Notification Alerts 2-17

Confirmation Alerts 2-18

Status Slips 2-20

Title and Message 2-21

Progress Indicator 2-22

2-1

iv

Page 5

Close, Stop, or Cancel 2-23

User Decision 2-24

Palettes 2-24

Drawers 2-26

Roll Views 2-27

How Views Work 2-28

Opening Container Views 2-28

View Display Order 2-28

The Backdrop 2-29

What Is Active 2-29

View Position 2-30

Position of a Main View 2-30

Position of Auxiliary Views 2-31

Closing a View 2-32

Closing a Main View 2-32

Closing a Slip 2-33

Closing a Drawer 2-33

Moving a View 2-33

Changing a View’s Size 2-34

Scrolling 2-36

Scrolling With Scroll Arrows 2-37

Universal Scroll Arrows 2-38

Local Scroll Arrows 2-39

Four-way Scrolling 2-41

Automatic Scrolling 2-43

Scrolling Performance 2-44

Overview 2-44

Overview Contents 2-44

Overview Button 2-46

Switching to and from an Overview 2-47

Scroll and Overview in an Overview 2-48

Closing an Overview 2-49

Nonfunctional Scroll and Overview Controls 2-49

v

Page 6

Chapter 3

Controls

Buttons 3-2

Text Buttons 3-2

Text Button Sizes 3-3

Naming Text Buttons 3-4

Naming Take-Action Buttons 3-4

Naming Cancel- and Stop-Action Buttons 3-5

Picture Buttons 3-7

Designing Picture Buttons 3-8

Button Behavior 3-9

Button Feedback 3-9

Button States 3-10

Button Placement 3-11

Button Spacing 3-12

Large Buttons 3-14

Close Boxes 3-14

Where to Use a Regular Close Box 3-15

Where to Use a Large Close Box 3-15

Radio Buttons 3-16

Checkboxes 3-18

Sliders 3-20

Hot Spots 3-21

Standard Newton Buttons 3-22

Analog Clock Button 3-23

Info Button 3-23

Recognizer Button 3-24

Keyboard Button 3-25

New Button 3-26

Show Button 3-26

Filing Button 3-27

Action Button 3-28

Item Info Button 3-29

Rotate Button 3-30

3-1

vi

Page 7

Chapter 4

Pickers

List Pickers 4-2

Elements of List Pickers 4-2

Check Marks 4-3

Icons 4-3

Item Names 4-3

Table of Items 4-4

Unavailable Items 4-5

Organization of List Pickers 4-6

Sources of List Pickers 4-7

Position of List Pickers 4-8

Using a List Picker 4-9

Picking an Item 4-9

User Editing of Pickers 4-11

Scrolling 4-12

Index Tabs 4-13

Hierarchical List Pickers 4-14

Number Picker 4-16

Date and Time Pickers 4-17

Overview Pickers 4-19

Contents of Overview Pickers 4-19

Position of Overview Pickers 4-20

Using an Overview Picker 4-21

Picking Items 4-21

Scrolling Items 4-22

Creating New Items 4-23

Standard Newton Pickers 4-23

Info Picker 4-24

New Picker 4-25

Show Picker 4-26

Action Picker 4-26

People Picker 4-27

4-1

vii

Page 8

Chapter 5

Icons

Designing Effective Icons 5-1

Thinking Up an Icon Image 5-2

Make Shapely Icons 5-3

Design for the Newton Display 5-3

Avoid Text in Icons 5-4

Make All Sizes of an Icon Look Alike 5-4

Use Icons Consistently 5-5

Think About Multicultural Compatibility 5-6

Extras Drawer Icons 5-6

Extras Drawer Icons Together 5-6

Extras Drawer Icon Size 5-8

Extras Drawer Icon Shape 5-9

Extras Drawer Icon Names 5-9

Animating an Extras Drawer Icon 5-9

Title Icons 5-11

Button Icons 5-12

Icons in a Picker 5-12

5-1

Chapter 6

viii

Data Input

Input Fields 6-1

Tapping 6-3

Pickers 6-3

Scrolling Lists and Tables 6-4

Radio Buttons 6-6

Checkboxes 6-7

Sliders 6-7

Writing, Drawing, and Editing 6-8

Text Input 6-8

Simple Input Line 6-9

Labeled Input Line 6-10

Text Input Lines that Expand 6-11

Paragraph Input 6-12

Structured List Input 6-12

6-1

Page 9

Shape Input 6-13

General Input 6-14

Recognition 6-15

User Control of Recognition 6-16

Deferred Recognition 6-18

Forcing Recognition 6-19

Configuring Recognition 6-19

Editing 6-21

Selecting Text and Shapes 6-22

Erasing Text or Shapes 6-24

Joining Words 6-26

Breaking Paragraphs 6-26

Inserting Space in Text 6-26

Inserting New Text 6-27

Replacing Text 6-29

Correcting Misrecognized Text 6-29

Changing Capitalization of Text 6-31

Changing Paragraph Margins 6-31

Removing Extra Space from Paragraphs 6-31

Duplicating Text or Shapes 6-31

Changing Shapes 6-31

Moving Objects 6-32

Typing 6-32

Displaying Keyboards 6-33

Keyboard Position 6-34

Keys 6-34

Character Keys 6-34

Return 6-35

Tab 6-35

Del 6-35

Shift 6-35

Caps 6-35

Option 6-36

Arrow Keys 6-36

Type-Ahead and Auto-Repeat 6-36

ix

Page 10

Error Handling 6-37

Error Correction 6-37

Error Detection 6-38

Chapter 7

Routing and Communications

The In/Out Box 7-2

The In Box 7-3

The Out Box 7-4

In/Out Box Items 7-4

Viewing Items in the In/Out Box 7-5

Viewing Routing Information 7-6

Routing Outgoing Items 7-7

Action Button and Picker 7-8

An Action Button’s Location 7-9

Action Picker Contents 7-10

Building an Action Picker 7-11

Routing Slips 7-12

Sender Picker 7-13

Recipient Pickers 7-15

Choosing a Printer 7-15

Choosing Fax or E-mail Recipients 7-16

Transport Picker 7-18

Send Button and Close Box 7-18

Other Routing Slip Elements 7-20

Format Picker 7-20

Preview Button 7-23

Sending Out Box Items 7-24

Routing Incoming Items 7-24

Receiving In Box Items 7-25

Receiving Remote In Box Items 7-26

Disposing of Received Items 7-26

Putting Away Received Items 7-27

Putting Away Items Automatically 7-28

Filing Items That Are Put Away 7-28

Extending the Tag Picker 7-29

7-1

x

Page 11

Routing Status 7-29

Stopping a Send or Receive in Progress 7-31

Transport Preferences 7-32

Routing Alternatives 7-34

Routing by Intelligent Assistant 7-35

Programmed Sending 7-36

Chapter 8

Newton Services

Automatic Busy Cursor 8-2

Notify Button and Picker 8-2

Alarms 8-4

Unacknowledged Alarms 8-5

Alarm Etiquette 8-5

Sound 8-6

Find 8-6

Text Searches 8-7

Date Searches 8-8

The Scope of a Search 8-8

Customizing the Standard Find Slip 8-9

Initiating or Canceling a Search 8-11

Search Status 8-11

Search Results 8-11

Filing 8-13

Filing Button and Slip 8-14

A Filing Button’s Location 8-15

A Filing Slip’s Contents 8-16

Editing Folders 8-18

Folder Tab 8-19

Intelligent Assistant 8-22

Invoking the Assistant 8-22

Interpreting the Request Phrase 8-23

Assist Slip 8-24

Task Slips 8-27

Help 8-28

8-1

xi

Page 12

Preferences 8-30

System-wide Preferences 8-30

Application Preferences 8-31

Appendix

Avoiding Common Mistakes

Info Button A-1

New and Show Buttons A-1

Screen Size A-1

Tapping v. Writing A-1

Picker Placement and Alignment A-2

Field Alignment A-2

Close Box Size A-2

Button Location A-2

Button Spacing A-2

Button Size A-3

Capitalization A-3

Picker Icons A-3

Dismissing a Slip A-3

Take-Action Button A-3

Fonts A-4

Keyboard Button A-4

Punctuation to Avoid A-4

Extras Drawer Icons A-4

Storage A-5

Date and Time Input A-5

A-1

xii

Glossary

Index

GL-1

IN-1

Page 13

Figures

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Newton and Its Users

Figure 1-1

Figure 1-2

Figure 1-3

Metaphors help people quickly grasp how

software works 1-5

Users should feel they are directly controlling

something tangible 1-6

An application adjusts its size, position, and layout to

fit the screen 1-12

Container Views

Figure 2-1

Figure 2-2

Figure 2-3

Figure 2-4

Figure 2-5

Figure 2-6

Figure 2-7

Figure 2-8

Figure 2-9

Figure 2-10

Figure 2-11

Figure 2-12

Figure 2-13

Figure 2-14

Figure 2-15

Figure 2-16

Figure 2-17

Examples of container views 2-2

Standard controls for manipulating views 2-4

Various title styles 2-5

A matte border indicates a movable view 2-6

A striped border suggests routing 2-7

An alert box has a thick wavy border 2-8

Some views need the simplicity of a

plain border 2-8

Sparing use of some types of shadows is OK 2-9

A title or a folder tab tops a main view 2-10

A status bar anchors primary controls at the bottom

of a main view 2-11

Separator bars separate multiple items in a

scrolling view 2-12

Main views have matte or plain borders with

rounded corners 2-13

Examples of auxiliary views 2-14

Users can move most slips 2-15

Dismissing slips that complete actions 2-16

A notification alert tells the user something

important 2-17

A Snooze button enables a user to dismiss an alert

temporarily 2-18

1-1

2-1

xiii

Page 14

Figure 2-18

Figure 2-19

Figure 2-20

Figure 2-21

Figure 2-22

Figure 2-23

Figure 2-24

Figure 2-25

Figure 2-26

Figure 2-27

Figure 2-28

Figure 2-29

Figure 2-30

Figure 2-31

Figure 2-32

Figure 2-33

Figure 2-34

Figure 2-35

Figure 2-36

Figure 2-37

Figure 2-38

Figure 2-39

A confirmation alert tells the user about a grave

situation 2-19

A status slip reports on a lengthy operation 2-20

A sequence of status messages traces the steps

of an operation 2-22

A gauge in a status slip measures elapsing

progress 2-23

A status slip can report a condition that demands

a user decision 2-24

A palette provides handy access to useful

settings 2-25

A drawer slides open and closed 2-26

Where to position a small auxiliary view 2-31

Dragging a view’s drag handle moves

the view 2-34

Dynamically adjust a view’s position, size, and layout

to fit the screen 2-35

A view may change size in response to user

actions 2-35

Ready to scroll Notepad notes into view from

above or below 2-36

Scrolling by tapping a down arrow 2-37

The universal scroll arrows at the bottom of a

MessagePad screen 2-39

How scroll arrows work in the Date Book’s

Day view 2-40

Scroll arrow color may indicate what scrolling

will reveal 2-41

A control for scrolling in four directions 2-42

An alternate control for scrolling in four

directions 2-42

Automatic scrolling 2-43

How an overview relates to a detail view 2-45

The Overview button at the bottom of a

MessagePad screen 2-46

Getting an overview 2-47

xiv

Page 15

Chapter 3

Controls

3-1

Figure 3-1

Figure 3-2

Figure 3-3

Figure 3-4

Figure 3-5

Figure 3-6

Figure 3-7

Figure 3-8

Figure 3-9

Figure 3-10

Figure 3-11

Figure 3-12

Figure 3-13

Figure 3-14

Figure 3-15

Figure 3-16

Figure 3-17

Figure 3-18

Figure 3-19

Figure 3-20

Figure 3-21

Figure 3-22

Figure 3-23

Figure 3-24

Figure 3-25

Figure 3-26

Figure 3-27

Figure 3-28

Figure 3-29

Figure 3-30

Tapping a button initiates an action 3-2

A text button’s name states what the

button does 3-2

Leave standard margins between a button’s name and

its borders 3-3

Name buttons distinctively wherever possible 3-5

Where to use a button named Cancel 3-6

A Stop button lets a user halt an operation 3-6

A picture button depicts what the button does 3-7

Where to use borders with small, self-bordered

picture buttons 3-8

Tapping a button highlights it 3-9

A button disappears when it isn’t available 3-10

Where to put buttons in a view 3-12

Group buttons by function 3-12

Regular spacing between buttons on a

MessagePad 3-13

A Close box compared to a large Close box 3-14

Where to use a regular Close box 3-15

Where to use a large Close box 3-16

Only one radio button in a cluster can

be selected 3-17

Each checkbox can be on or off 3-19

One checkbox vs. two radio buttons 3-20

A slider used for data input 3-21

Providing feedback for small, transparent

hot spots 3-22

How the Analog Clock button works 3-23

Where an Info button goes 3-24

Where a Recognizer button goes 3-24

The Recognizer button indicates the type of

recognition in effect 3-24

Where a Keyboard buttons goes 3-25

Where a New button goes 3-26

Where a Show button goes 3-26

Where a Filing button goes 3-27

A Filing button reports where a data item

is stored 3-28

xv

Page 16

Figure 3-31

Figure 3-32

Figure 3-33

Where an Action button goes 3-29

Seeing an Item Info slip 3-30

A Rotate button lets users change the screen

orientation 3-31

Chapter 4

Pickers

Figure 4-1 The parts of list pickers 4-2

Figure 4-2 A list picker can contain a two-dimensional table

Figure 4-3 Remove unavailable items from a list picker 4-5

Figure 4-4 Grouping items in list pickers 4-7

Figure 4-5 Pickers can pop up from buttons, labels, and

Figure 4-6 How a list picker should align with its label

Figure 4-7 Using a list picker from a button 4-10

Figure 4-8 Using a list picker from a label 4-10

Figure 4-9 List pickers that are too long to display all at once

Figure 4-10 A lengthy picker can include scroll arrows and

Figure 4-11 How a two-level hierarchy of list pickers works 4-15

Figure 4-12 A number picker simplifies specifying a numerical

Figure 4-13 Time pickers specify a time, a time range, or a

Figure 4-14 Date pickers specify one date or a date range 4-18

Figure 4-15 The parts of overview pickers 4-20

Figure 4-16 Entering a new value in an overview picker 4-22

Figure 4-17 An Info picker lists information items 4-24

Figure 4-18 The New picker lists types of data items that users

Figure 4-19 The Show picker lists alternate ways to see an

Figure 4-20 The Action picker lists commands for acting

Figure 4-21 A People picker excerpts items from the Names File

4-1

of items 4-5

hot spots 4-8

or button 4-9

have scroll arrows 4-12

index tabs 4-13

value 4-16

time offset 4-17

can create 4-25

application’s data 4-26

on data 4-27

and Owner Info applications 4-28

xvi

Page 17

Chapter 5 Icons 5-1

Figure 5-1 Distinctive icon shapes are easier to recognize than

Figure 5-2 Avoid text in icons 5-4

Figure 5-3 Small icon resembles large icon 5-5

Figure 5-4 Use icon elements consistently 5-5

Figure 5-5 The good, the bad, and the ugly in Extras

Figure 5-6 Large icons crowd the Extras Drawer 5-8

Figure 5-7 An icon’s mask either highlights or animates

Figure 5-8 Combining an icon with its mask to animate

Figure 5-9 An icon in a slip title should decorate

Figure 5-10 An icon can label a button 5-12

Figure 5-11 Icons can help communicate picker item

Chapter 6 Data Input 6-1

Figure 6-1 Users enter and edit data in input fields 6-2

Figure 6-2 How a picker works for data input 6-4

Figure 6-3 Data input using scrolling lists with or without

Figure 6-4 With radio buttons, a user can select one value

Figure 6-5 With checkboxes, a user can select more than one

Figure 6-6 A slider used for data input 6-7

Figure 6-7 How an unlabeled text-input line works 6-9

Figure 6-8 How labeled text input lines work 6-10

Figure 6-9 How expandos work 6-11

Figure 6-10 Interface element for multiple-line or paragraph

Figure 6-11 A user can rearrange a structured list by dragging

Figure 6-12 Interface element for shape input 6-14

Figure 6-13 Interface element for general input 6-15

rectangular icons 5-3

Drawer icons 5-7

the icon 5-10

the icon 5-11

and inform 5-11

functions 5-13

checkboxes 6-5

for a field 6-6

value for a field 6-7

text input 6-12

topic markers 6-13

xvii

Page 18

Figure 6-14 The Recognizer button and picker give users control

Figure 6-15 Users may need to control recognition separately

Figure 6-16 In an Alpha Sorter picker, users select a sort key

Figure 6-17 Selecting words and shapes 6-23

Figure 6-18 Orientations of the scrubbing gesture 6-24

Figure 6-19 Scrubbing a little or a lot 6-25

Figure 6-20 Joining two words 6-26

Figure 6-21 Breaking a paragraph into two paragraphs 6-26

Figure 6-22 Inserting space in text 6-27

Figure 6-23 A caret marks the text insertion point 6-27

Figure 6-24 The Caret picker lists 14 hard-to-write characters and

Figure 6-25 How a Correction picker works 6-29

Figure 6-26 How a Corrector view works 6-30

Figure 6-27 The four built-in keyboards 6-32

Figure 6-28 A Keyboard picker lists alternate on-screen

Figure 6-29 A keyboard can be embedded in a data-

over recognition 6-16

in a slip 6-17

for ink text 6-19

three actions 6-28

keyboards 6-33

input slip 6-34

Chapter 7 Routing and Communications 7-1

xviii

Figure 7-1 The In/Out Box application displays either the In Box

or the Out Box 7-3

Table 7-1 Meanings of status words in the In/Out Box

headers 7-5

Figure 7-2 A Show button provides access to alternative

views 7-6

Figure 7-3 Viewing routing information in an Item Info slip 7-7

Figure 7-4 An Action picker lists the transports available

for sending 7-8

Figure 7-5 An Action button at the bottom of a view affects the

entire view 7-9

Figure 7-6 An Action button above an item affects only

that item 7-10

Figure 7-7 An Action picker can include two kinds

of actions 7-11

Page 19

Figure 7-8 A routing slip shows sender, recipient, and type

Figure 7-9 Changing the sender’s name or location 7-14

Figure 7-10 Choosing a printer in a routing slip 7-16

Figure 7-11 Choosing fax or e-mail recipients in a

Figure 7-12 Switching to another transport in a group 7-18

Figure 7-13 Setting format and content options in a

Figure 7-14 Format choices vary by transport and class

Figure 7-15 A format can get supplemental information in

Figure 7-16 Previewing outgoing page images 7-23

Figure 7-17 The Out Box’s Send picker lets users send items to

Figure 7-18 The Receive picker lists the transports available

Figure 7-19 Connection setup varies by transport 7-26

Figure 7-20 The Tag picker disposes of currently selected

Figure 7-21 Status slips apprise users of lengthy transport

Figure 7-22 Accessing transport preferences from the In/Out Box’s

Figure 7-23 Some common preference items for

Figure 7-24 A Call routing slip sets up an outgoing

Figure 7-25 Routing with the Intelligent Assistant 7-35

of transport 7-13

routing slip 7-17

routing slip 7-20

of data 7-21

an auxiliary view 7-22

output devices 7-24

for receiving 7-25

In Box items 7-27

activities 7-30

Info picker 7-32

transports 7-33

phone call 7-34

Chapter 8 Newton Services 8-1

Figure 8-1 A busy cursor indicates the system is temporarily

engaged 8-2

Figure 8-2 The Notify button signals an ongoing action or

deferred alert 8-3

Figure 8-3 The Notify picker lists ongoing actions and

deferred alerts 8-3

Figure 8-4 An alarm notification alert’s Snooze button can

postpone the alarm 8-4

xix

Page 20

Figure 8-5 A standard Find slip specifies what to find and where

Figure 8-6 Specifying text or date searches in a Find slip 8-7

Figure 8-7 Specifying a date in a Find slip 8-8

Figure 8-8 Searching specified applications 8-9

Figure 8-9 A custom Find slip displays application-specific

Figure 8-10 A status slip shows the progress of a Find

Figure 8-11 A Find overview lists items that match search

Figure 8-12 The Find slip reports which found item is currently

Figure 8-13 A Filing slip names available folders and storage

Figure 8-14 A Filing button at the bottom of a view affects the

Figure 8-15 A Filing button above an item affects only

Figure 8-16 A Filing slip can include storage locations, folders,

Table 8-1 Headings for radio button clusters in

Figure 8-17 Slips for entering and editing folder names 8-19

Figure 8-18 A folder tab allows users to filter a view

Figure 8-19 A Folder picker can list available storage

Figure 8-20 A folder tab can include a digital clock and

Figure 8-21 A folder tab can include a view title 8-21

Figure 8-22 The Assist button makes the Assistant try a written

Figure 8-23 An Assist slip appears when the Assistant needs

Figure 8-24 The Assistant’s Please picker lists known actions and

Figure 8-25 Online help has a topical outline and concise

Figure 8-26 The Prefs application shows system-wide

Figure 8-27 A preferences slip contains application-specific

to look 8-7

criteria at the top 8-10

operation 8-11

criteria 8-12

displayed 8-13

locations 8-14

entire view 8-15

that item 8-16

or both 8-17

Filing slips 8-18

by folder 8-20

locations 8-20

calendar 8-21

action request 8-23

more information 8-25

recent phrases 8-26

instructions 8-28

preference settings 8-30

settings 8-31

xx

Page 21

PREFACE

About This Book

Newton 2.0 User Interface Guidelines describes how to create

software products that optimize the interaction between people

and devices that use Newton 2.0 software. The book explains

the whys and hows of the Newton 2.0 interface in general terms

and in specific details.

Newton 2.0 User Interface Guidelines helps you link the philosophy

behind the Newton 2.0 interface to the actual implementation of

the interface elements. Examples from a range of Newton software show good human interface design. These examples are

augmented by descriptions and discussions of the reasoning behind

the guidelines.

This book also contains examples of how not to design human

interface; they are marked as such and appear with a discussion

that points out what’s inappropriate and how to correct it.

Who Should Read This Book

This book is for people who design and develop software for

Newton devices. If you are a designer, a human interface

professional, or an engineer, this book contains information you

need to design and create software that fits the Newton model.

It also provides background information to help you plan your

software product’s design.

Even if you don’t design and develop software for Newton, reading

this book will help you understand the Newton interface. This

understanding is useful to managers and planners who are

thinking about developing Newton software, as well as to people

who are studying human interface design in general.

xxi

Page 22

PREFACE

This book assumes you are familiar with the concepts and

terminology used with Newton devices, and that you have used a

Newton device and its standard applications.

What’s in This Book

This book begins with a chapter that describes Newton devices

such as the Apple MessagePad, what people do with them, and

how they differ from personal computers. The first chapter also

presents important principles you should keep in mind when

designing Newton software, and explains how to involve users

in designing the interface. The rest of the chapters define various

parts of the Newton 2.0 interface. They describe each interface

element in general language and show examples of how to use

the elements correctly. For the more technical reader, the book

specifies dimensions, spacing, and other specific implementation

details for the Apple MessagePad. The book concludes with a list

of common interface mistakes and a glossary.

Related Books

xxii

This book does not explain how to create Newton software with

Newton Toolkit, the Newton development environment. For that

you’ll need to refer to these other books, all of which come with

Newton Toolkit:

■ Newton Programmer’s Guide

guide and reference for Newton programming. This book

explains how to write Newton programs and describes the

system software routines that you can use to do so.

.

This set of books is the definitive

Page 23

PREFACE

■ Newton Toolkit User’s Guide. This book introduces the Newton

Toolkit (NTK) development environment and shows how to

develop Newton applications using Newton Toolkit. You

should read this book first if you are a new Newton application

developer.

■ Newton Book Maker User’s Guide. This book describes how to use

Newton Book Maker and Newton Toolkit to make Newton

digital books and to add online help to Newton applications.

You have this book only if you purchased the Newton Toolkit

package that includes Book Maker.

■ The NewtonScript Programming Language. This book describes

the NewtonScript programming language.

Visual Cues Used in This Book

Throughout this book you’ll see visual cues to certain types of

information.

■ Boldfaced text indicates that a new term is being defined and

that a definition of the word appears in the glossary.

■ This symbol indicates an example of the correct way to use a

Newton interface element.

■ This symbol indicates an example of the wrong way to

use a Newton interface element. It specifically calls out

common mistakes.

Developer Products and Support

APDA is Apple’s worldwide source for hundreds of development

tools, technical resources, training products, and information for

anyone interested in developing applications for Apple computer

platforms. Customers receive the Apple Developer Catalog, which

xxiii

Page 24

PREFACE

features all current versions of Apple development tools, as well

as popular third-party development tools. APDA offers

convenient payment and shipping options, including site

licensing.

To order product or to request a complimentary copy of the Apple

Developer Catalog, use the following information:

APDA

Apple Computer, Inc.

P.O. Box 319

Buffalo, NY 14207-0319

Telephone 1-800-282-2732 (United States)

1-800-637-0029 (Canada)

716-871-6555 (International)

Fax 716-871-6511

AppleLink APDA

America Online APDAorder

CompuServe 76666,2405

Internet APDA@applelink.apple.com

xxiv

If you provide commercial products and services, call

408-974-4897 for information on the developer support

programs available from Apple.

Page 25

Figure 1-0

Table 1-0

CHAPTER 1

Newton and Its Users 1

Before you can begin to design an application, it is crucial that you have a

clear picture of what a Newton device can do and how people will use your

Newton software. This chapter introduces some high-level concepts that

will help you clarify that picture. In addition, this chapter presents some

basic principles of user interface design that apply to all types of software.

The chapter concludes by detailing how to conduct user tests of your

product during its development.

Understand Newton 1

Newton is a software and hardware technology designed for a family of

products in the category of personal digital assistants (PDAs), such as the

Apple MessagePad. The goal of Newton technology is to help people and

businesses become more productive by simplifying basic tasks and making it

easier for people to manage bits and pieces of information while on the

move. Information entered on a Newton device can be moved to a desktop

machine or a mainframe computer, where it can be manipulated in powerful

applications.

Understand Newton 1-1

Page 26

CHAPTER 1

Newton and Its Users

Newton is not a small portable computer with another graphical user

interface. There may be similarities between portable computers and Newton

devices, but the differences summarized below are more important than the

similarities when it comes to designing a user interface for an application.

Newton Portable Computers

Focused function General purpose

New architecture optimized for

mobility and communications—

use it anywhere, any time

Tapping, writing, and drawing

with a pen

Intelligent assistant Scripting and macros

New and custom applications Existing desktop applications

It’s a communications assistant It’s a personal computer

Simple Complex

Derived from desktop computer

architecture, which is optimized

for stationary operation

Typing, pointing, and clicking with

mouse and keyboard

To take advantage of its distinguishing features and capabilities, Newton has

distinctive user interface elements.

Know Your Audience 1

Identifying and understanding your target audience are among the most

important first steps when you start designing your product. To create a

product that people can and will use, study the people who make up your

target audience.

It’s useful to create scenarios that describe a typical day in the life of a person

you think uses the type of product you’re designing. Think about the different

work spaces, tools, and constraints and limitations that people deal with.

You can also visit actual work places and study how people do their jobs.

Analyze the steps necessary to complete each task you anticipate people

wanting to accomplish. Then design your product to facilitate those tasks,

1-2 Know Your Audience

Page 27

CHAPTER 1

Newton and Its Users

using a step-by-step approach by thinking of how a person might get from

one place to the next in a logical fashion.

Involve users throughout the design process and observe them working in

their environment. Use people who fit your audience description to test your

prototypes and development products. Listen to their feedback and try to

address their needs in your product. Develop your product with people and

their capabilities, not computers and their capabilities, in mind. For more

information, see “Involve Users in the Design Process” on page 1-13.

What P eople Do With Newton 1

The features and capabilities that make Newton what it is also strongly

influence what people want to do with Newton devices. These expectations

indirectly affect the user interface of Newton software. An application must

make it easy for people to accomplish the following tasks on demand:

■ Capture information fragments—write, sketch, pick from lists, specify

dates and times, and select options

■ Organize information—file, sort, schedule, prioritize, copy, delete,

and format

■ Retrieve information—find, recall, browse, skim, read, and view

■ Send and in some cases receive information by various means—print, fax,

mail, and direct transfer

Accessibility 1

Your software needs to appeal to and be useful to people with a wide range

of abilities and backgrounds. There are likely to be members of your target

audience who are different from the so-called average user that you envision.

Users will undoubtedly vary in their ages, styles, and abilities. They may

also have physical or cognitive limitations, linguistic differences, or other

differences you need to consider. Identify how the individuals in your target

audience differ and what special needs they may have.

Know Y our Audience 1-3

Page 28

CHAPTER 1

Newton and Its Users

Make your application accessible to people around the world by including

support for worldwide capabilities in your designs from the beginning of

your development process. Take stock of the cultural and linguistic needs

and expectations of your target audiences.

Observe Basic Human Interface Principles 1

Effective software adheres to certain basic principles no matter whether it

runs on a Newton PDA, a personal computer, or a high-powered computer

workstation. These principles are based on the capabilities and processes not

of the machine but of the human operator—how people usually think, act,

and work.

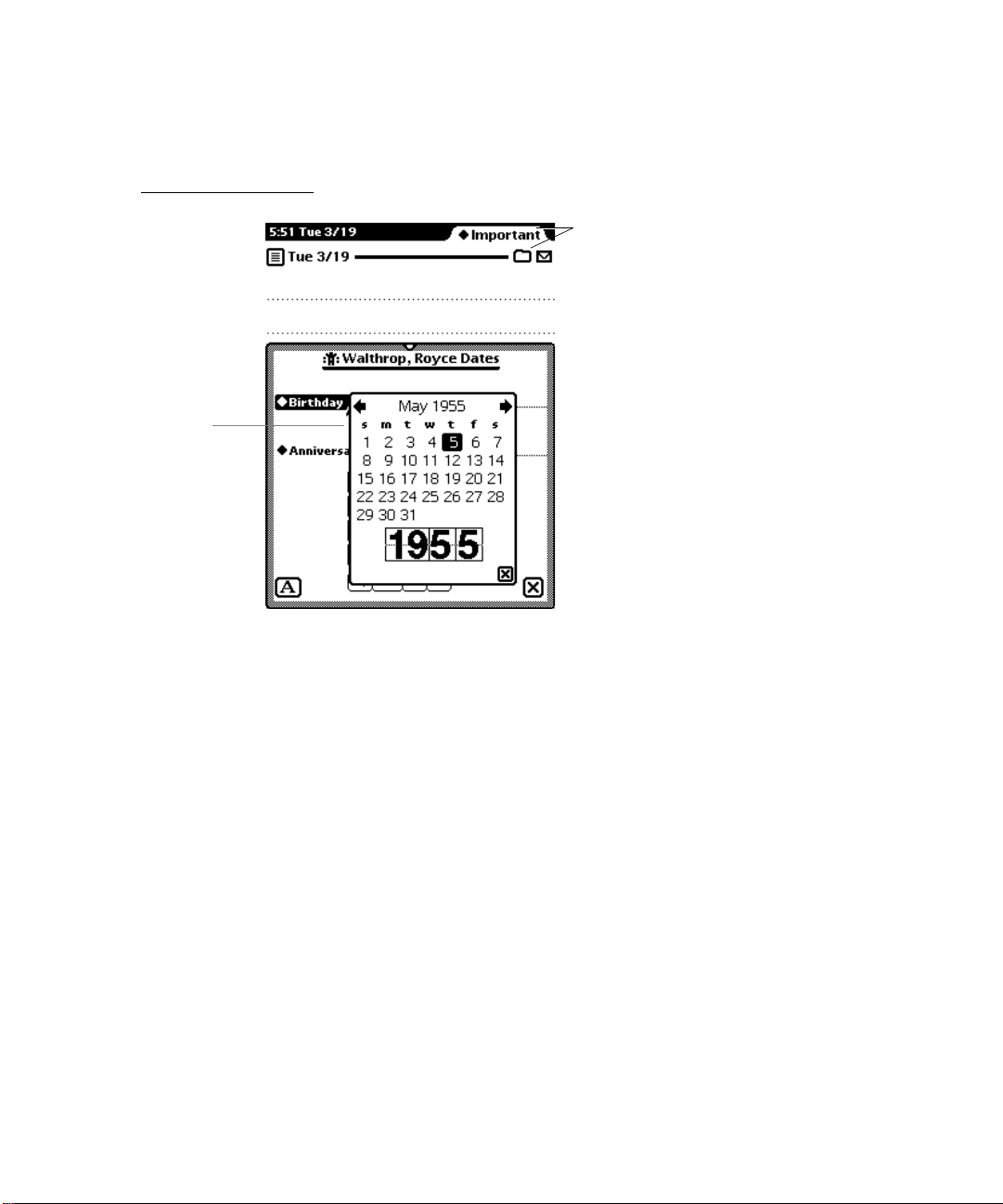

Metaphors 1

Wherever possible, model the actions and objects in your program on

something from the real world. This trick especially helps inexperienced

users quickly grasp how your program works. Folders are a classic metaphor.

People file things in folders in the real world, so they immediately understand

the concept of filing data items in folders on a Newton. Other common

metaphors include scrubbing to delete data, tapping buttons to make things

happen, sending and receiving things through an in box and out box, setting

dates and times on calendars and digital clocks, and homing in on information

with alphabetic index tabs. Figure 1-1 illustrates some Newton metaphors.

Metaphors suggest a use for objects and actions in the Newton interface, but

that use doesn’t define or limit the implementation of the metaphor. For

example, a paper folder has a limited storage capacity, but a folder on a

1-4 Observe Basic Human Interface Principles

Page 29

Folder button and

C

alendar for

s

pecifying a date

CHAPTER 1

Newton and Its Users

Figure 1-1 Metaphors help people quickly grasp how software works

folder tab for filing

notes

Newton doesn’t have to be constrained by the same limitation. Newton

folders can hold a limitless number of items (up to the storage capacity of

the hardware), and this is an advantage that the Newton can offer. Try to

strike a balance between the metaphor’s suggested use and the ability of the

Newton to support and extend the metaphor.

Naturally you can’t find a metaphor for everything. Be sure to use the

established metaphors, but if you can’t come up with a solid metaphor for

another object or action, then do without. Don’t distort the real world into

a caricature in a slavish attempt to find a metaphor.

Observe Basic Human Interface Principles 1-5

Page 30

CHAPTER 1

Newton and Its Users

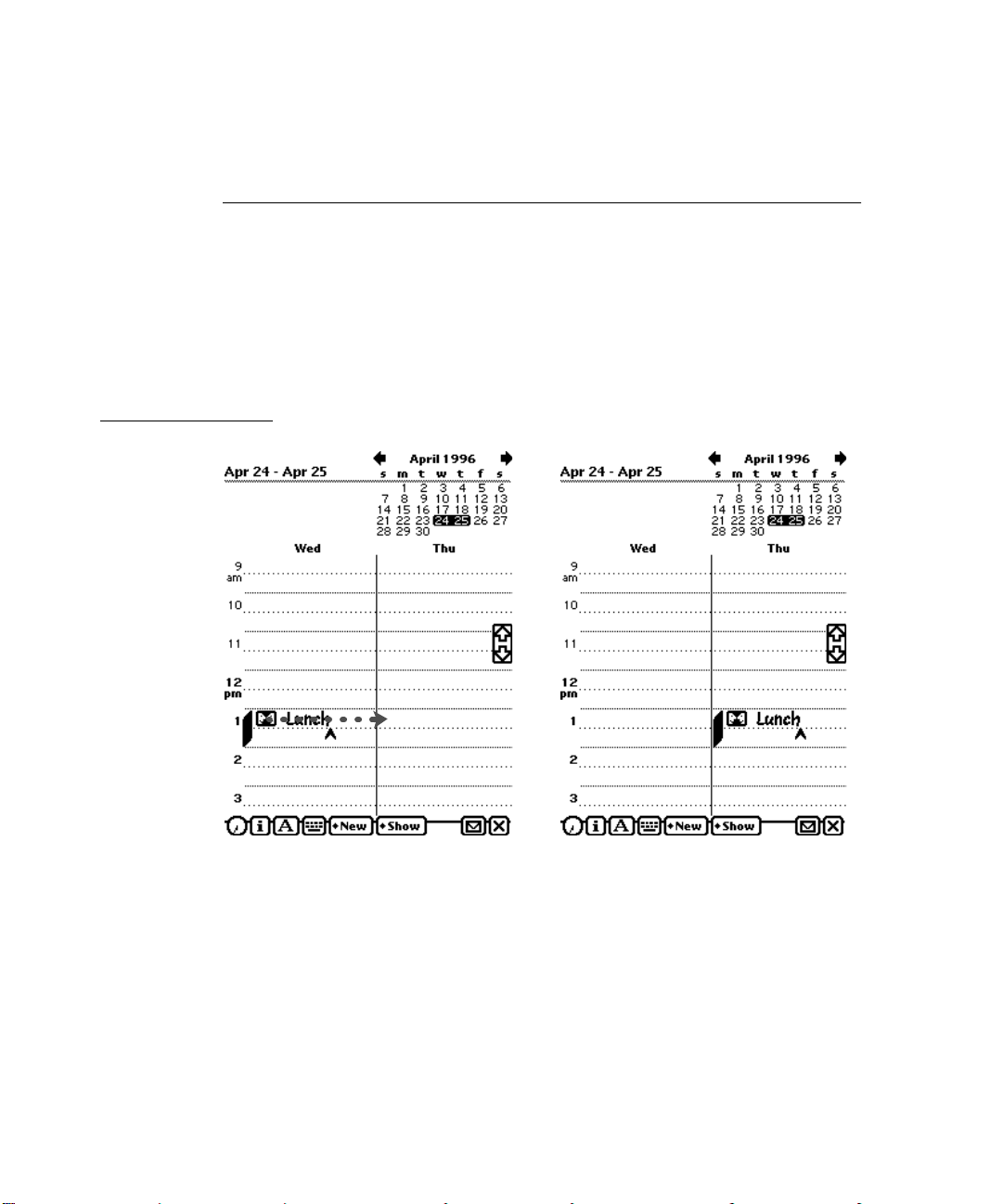

Direct Manipulation 1

Your product should let users feel that they are directly controlling

something tangible, not abstract. Make sure objects on the screen remain

visible while a user performs actions on them, and make the result of the

user’s actions immediately visible. For example, a user can reschedule a

meeting in the built-in Date Book application by dragging the meeting’s icon

from one time to another. Figure 1-2 illustrates direct manipulation.

Figure 1-2 Users should feel they are directly controlling something tangible

1. User drags a meeting icon to a new time 2. Icon appears at new meeting time

1-6 Observe Basic Human Interface Principles

Page 31

CHAPTER 1

Newton and Its Users

Feedbac k 1

In addition to seeing the results of their actions, users need immediate feedback when they operate controls and ongoing status reports during lengthy

operations. Have your application respond to every user action with some

visible change. For example, make sure every button highlights when a user

taps it. Audible feedback also helps, but can’t be the primary or sole feedback

because people may use Newtons in places where they can’t hear or where

they must turn off the sound.

The system automatically provides feedback when it’s temporarily busy by

displaying the busy cursor. During operations that last more than a few

seconds, your application should display explanatory messages and show

elapsing progress.

See and P oint 1

A Newton application is better than a person at remembering lists of options,

commands, data, and so on. Take advantage of this situation by presenting

lists and letting users choose from them. People can concentrate on

accomplishing tasks with your program instead of remembering how to

operate it. As a bonus, your program controls its inputs and doesn’t have to

check as many error conditions.

Consistency 1

It’s likely that people will use other Newton software besides yours—at the

least they will use some of the built-in applications and services. You can

turn this likelihood to your advantage by designing your application’s interface to be consistent with other Newton applications. Both you and your

application’s users benefit if they can build on prior experience when learning

how to use your application.

Observe Basic Human Interface Principles 1-7

Page 32

CHAPTER 1

Newton and Its Users

You can make your application consistent visually and behaviorally by

incorporating standard Newton interface elements in it. Visual consistency

helps people learn and then easily recognize the graphic language of the

interface. For example, users learn to recognize a black diamond as the

source of a pop-up list of choices. Behavioral consistency of the interface

means people only have to learn once how to do things such as erasing and

scrolling. Then they can explore new functions and applications using the

skills they already have.

User Control 1

Allow users, not your application, to initiate and control actions. Keep

actions simple and straightforward so users can easily understand and

remember them. Provide ample opportunity to cancel operations before they

begin, and wherever possible allow users to gracefully stop an operation

that’s underway. Be careful about unleashing agents, experts, or wizards that

will do things behind a user’s back.

Forgiveness 1

People make mistakes, so your program should make it easy for them to

correct their mistakes. Let them use the Undo button to reverse their last

action. People need to feel they can experiment without damaging the

system or their data. Create safety nets for people so they feel comfortable

learning and using your product.

Always advise people when they begin an operation that has potentially

dire consequences. Display a warning and have the user confirm the operation

before proceeding. This doesn’t mean you should have users confirm every

action. Frequent warning messages suggest something is wrong with

the program design—obviate some of the warnings by making more

actions reversible.

1-8 Observe Basic Human Interface Principles

Page 33

CHAPTER 1

Newton and Its Users

Stability 1

Personal digital assistants introduce a new level of complexity for many

people. To cope with this complexity, people need some stable reference

points. The Newton interface is designed to provide an environment that is

understandable, familiar, and predictable. It defines a number of regular

interface elements to foster a perception of stability, including view borders,

view titles, folder tabs, standard buttons, and standard button locations.

Each of these elements has a specific look and a regular, predictable behavior.

In addition, the interface defines a clear, finite set of basic data objects—text,

ink text, shapes, and sketches—and a clear, finite set of editing commands

with which users can create and manipulate the objects. Your application can

share and enhance the stability by using the regular interface elements and

handling data objects in the customary manner.

Aesthetic Integrity 1

People primarily see software as a functional product, not a fashion product.

This means you want them to notice what your product does, not how it

looks. Don’t succumb to the temptation to load up with the latest interface

fads; they’ll quickly become dated. Since people will spend a lot of time with

your product, design it to be pleasant to look at for a long time. A spare,

clean interface will stand up to repeated viewing much better than a highly

decorative interface. For example, the built-in Setup application has lots of

non-functional decorative elements to make a user’s first Newton experience

a friendly one, but the built-in applications that people use daily have none

of that decoration.

Make sure you follow the graphic language of the interface. Don’t invent

new interface elements to replace existing ones, and don’t change the

function of standard interface elements. If you change the look of standard

interface elements, people will actually try to make up functional reasons

for the differences. If you square off the corners of your buttons, use unique

view borders, or use a different symbol to designate a pop-up, people will

waste time trying to figure out what your custom elements do that the

standard ones don’t. It won’t occur to people that you merely have your own

notion of how the interface elements should look.

Observe Basic Human Interface Principles 1-9

Page 34

CHAPTER 1

Newton and Its Users

Design for the Newton System 1

In addition to the general user interface principles presented in the previous

section, you should keep in mind the guidelines in this section as you design

software specifically for the Newton system.

Observe the Built-In Applications 1

Your software will coexist with built-in Newton applications and services.

On an Apple MessagePad they include the Notepad, Names File, Date Book,

In/Out Box, Filing, Routing, Find, Assist, and others. If your application has

functions analogous to those in the built-in applications and services, use

the same mechanisms. Users will be accustomed to them and will expect

other software to work in the same way. You can most easily match the builtin applications and services by using the system proto templates in the

Newton Toolkit.

You can extend the Newton interface if you need to, but make sure your

extensions retain the original look and feel.

Use the Common P ool of Data 1

All built-in Newton applications and services can access a common pool of

data, and so can your Newton software. This pool is the information a user

enters into the Newton device. Since all applications have access to this data,

a user can work more efficiently—because each piece of information needs to

be entered only once. Thereafter, the data can be accessed and used in many

different ways. Your application can read and write this data. Put it to the

user’s advantage.

1-10 Design for the Newton System

Page 35

CHAPTER 1

Newton and Its Users

Keep Applications Simple 1

Newton isn’t designed for complex tasks or applications that require viewing

a large area or multiple windows of data at a time. Applications that require

the user to keep track of several pieces of information at once probably won’t

work well because the user must either move around a lot within the

application, or deal with many simultaneous or layered views. Studies show

that users become confused in those situations.

Remember that people will use Newton while on the move, in places where

there’s no place to sit or to set it down. In such settings, it’s easiest to use

applications with simple, straightforward screens and an obvious path

through the information. Make sure that your application’s controls are

clearly identified, that there aren’t too many “places” for the user to navigate

through, that you don’t display too many container views at once, and that

the user can easily see what to do. Minimize writing; tapping to pick from a

list of alternatives is easier.

Use Screen Space Wisely 1

Because the user’s hand is usually held close to a Newton device, it’s best to

keep tappable controls at the bottom of the screen, have the user enter data

in the middle of the screen, and display titles and other descriptors at the top

of the screen. This way, the most important information (the user’s information) isn’t obscured each time he or she taps a button. If you need to display

controls on the side, make sure your application allows users to move the

controls to either side of the screen, according to whether they are right- or

left-handed.

Check the Screen Size 1

A Newton application’s main view—the visual object that serves as the

application’s base of user operations—can be any size. If your application’s

main view does not fill the entire screen, keep in mind that whatever is

visible behind your application will be operable. In this situation, users can

Design for the Newton System 1-11

Page 36

CHAPTER 1

R

Newton and Its Users

get confused about what’s frontmost—and therefore about what will be

scrolled when the scroll arrows are tapped and which view is currently

in use.

Also keep in mind when designing your application that future Newton

devices may have larger or smaller screens than current Newton devices. To

work with different screen sizes, a Newton application must check the screen

size and make adjustments as needed to the size and location of the things it

displays so that everything fits. If you want your application to work in

either of the two display orientations available on an Apple MessagePad 120,

your application needs to be able to adjust the position and configuration

of everything it displays for regular or sideways orientation of the display.

Figure 1-3 shows how the built-in Notepad application and the on-screen

keyboard adjust their size, position, and layout when a user rotates

the display.

Figure 1-3 An application adjusts its size, position, and layout to fit the screen

Sideways orientation on a MessagePad 120

egular orientation on a MessagePad 120

1-12 Design for the Newton System

Page 37

CHAPTER 1

Newton and Its Users

Involve Users in the Design Process 1

The best way to make sure your product meets the needs of your target

audience is to show it to the kinds of people you hope will buy it. Do they

understand what it’s for and what to do with it? Can they use it? Can they

keep track of where they are? Does it help them? You can do this during

every phase of the design process to help reveal what works about your

product as well as what needs improvement.

When you give people an opportunity to use your product or a mock-up of

it, they will inevitably find some undiscovered flaws. You can implement

significant changes to your product during its evolution and thereby save

yourself lots of time and money and save your users from frustration. By

identifying and focusing on users’ needs and experiences, you can create

products that are easier to assemble, learn, and use. These improvements

can translate into competitive advantages, increased sales, and enhanced

customer satisfaction.

Define Y our Audience 1

There are several steps to involving users in your design process. The first

step, done at the beginning of a project, is to define the users and then do an

analysis of the target audience. You want to determine what these people

are like, how they might use a product like yours, if they have any similar

products, and what features they would like to see in your product. By doing

some research on your target audience, you can find out if what you’re

including in a product is desirable and useful.

Analyze Tasks 1

The second step is to analyze the tasks people will be doing with your

product. You need to do a task analysis for each task you anticipate that your

users will do. Look at how they perform similar tasks without a Newton.

Involve Users in the Design Process 1-13

Page 38

CHAPTER 1

Newton and Its Users

Then look at how the Newton can facilitate the tasks. To help plan a task

analysis, imagine a scenario in which someone uses your product. List each

task a person might perform in that scenario, then break each task apart into

its component steps. This allows you to identify each step that a person goes

through in order to complete the task. Order the steps according to how

people do them. When you feel you have all the steps listed and ordered,

read the list back to someone and see if that person can use the steps you’ve

listed to accomplish the task.

Build Prototypes 1

For the third step, apply the information you’ve collected about your users,

their skills, and the tasks you envision them performing to create a prototype

of your design. Prototyping is the process by which you develop preliminary

versions of your design to verify its workability. You can use a variety of

techniques to construct prototypes of your design. Creating storyboards is

one technique—you draw out the steps your users will go through to

accomplish a task. Another technique is to build a simulation of the product

in prototyping software that animates some features or demonstrates how

the product will work.

Observe Users 1

Once you have a prototype drawn or mocked up, you can begin to show it to

people to get reactions to it. The fourth step, called user observation, lets

you test the workability of your product design by watching and listening

carefully to users as they work with your prototype. Although it is possible

to collect far more elaborate data, observing users is a quick way to obtain an

objective view of your product. Before you do any testing, take time to figure

out what you’re testing and what you’re not. By limiting the scope of the

test, you’re more likely to get information that will help you solve a specific

problem. You can use the information you gather about your target audience

to help you pick participants for your user observation; find people who

have the same demographic background and experience level as the typical

user in your target audience. Your participants will work through one or

1-14 Involve Users in the Design Process

Page 39

CHAPTER 1

Newton and Its Users

more specific tasks. These tasks can be based on the task analyses that you

performed earlier in the design process. After you determine which tasks to

use, write them out as short, simple instructions. Your instructions to the

participants should be clear and complete but should not explain how to

do things you’re trying to test. See the following section, “Ten Steps for

Conducting a User Observation,” for more information; it includes a series

of sample steps on which you can base your own user observation.

During the user observation, record what you learn about your design; you’ll

be using this information to revise your prototype. Once you’ve revised your

prototype, conduct a second user observation to test the workability of the

changes you’ve made to your design. Continue this iterative process of

creating prototypes and conducting user observations until you feel

confident that you’ve fully addressed the needs of your target audience.

Ten Steps f or Conducting a User Observation 1

The following steps provide guidelines that you can use when conducting a

simple user observation. Remember, this test is not designed as an experiment,

so you will not get quantitative data that can be statistically analyzed. You

can, however, see where people have difficulty using your product, and you

can then use that information to improve your product.

Most of these steps include some explanatory text with sample statements

that you can read to the participant. Feel free to modify the statements to suit

your product and the situation.

1. Introduce yourself and describe the purpose of the observation (in very

general terms). Most of the time, you shouldn’t mention what you’ll be

observing.

Set the participant at ease by stressing that you’re trying to find problems

in the product. For example, you could say something like this:

n

“You’re helping us by trying out this product in its early stages.”

n

“We’re looking for places where the product may be difficult to use.”

n

“If you have trouble with some of the tasks, it’s the product’s fault, not

yours. Don’t feel bad; that’s exactly what we’re looking for.”

Involve Users in the Design Process 1-15

Page 40

CHAPTER 1

Newton and Its Users

n

“If we can locate the trouble spots, then we can go back and improve

the product.”

“Remember, we’re testing the product, not you.”

n

2. Tell the participant that it’s OK to quit at any time.

Never leave this step out. Make sure you inform participants that they can

quit at any time if they find themselves becoming uncomfortable. Participants shouldn’t feel like they’re locked into completing tasks. Say something like this:

“Although I don’t know of any reason for this to happen, if you should

n

become uncomfortable or find this test objectionable in any way, you

are free to quit at any time.”

3. Talk about the equipment in the room.

Explain the purpose of each piece of equipment (hardware, software,

video camera, tape recorder, microphones, and so forth) and how it will

be used in the test.

4. Explain how to think aloud.

Ask participants to think aloud during the observation, saying what

comes to mind as they work. By listening to participants think and plan,

you’ll be able to examine their expectations for your product as well as

their intentions and their problem-solving strategies. You’ll find that

listening to users as they work provides you with an enormous amount of

useful information that you can get in no other way.

Some people feel awkward or self-conscious about thinking aloud.

Explain why you want participants to think aloud and demonstrate how

to do it. For example, you could say something like this:

“We have found that we get a great deal of information from these

n

informal tests if we ask people to think aloud as they work through

the exercises.”

n

“It may be a bit awkward at first, but it’s really very easy once you get

used to it. All you have to do is speak your thoughts as you work. If

you forget to think aloud, I’ll remind you to keep talking. Would you

like me to demonstrate?”

1-16 Involve Users in the Design Process

Page 41

CHAPTER 1

Newton and Its Users

5. Explain that you will not provide help.

It is very important that you allow participants to work with your product

without any interference or extra help. This is the best way to see how

people really interact with the product. For example, if you see a participant

begin to have difficulty and you immediately provide an answer, you will

lose the most valuable information you can gain from user observation—

where users have trouble and how they figure out what to do.

Of course, there may be situations in which you will have to step in and

provide assistance, but you should decide what those situations will be

before you begin testing. For example, you may decide that you will allow

someone to struggle for at least three minutes before you provide

assistance. Or you may decide that there is a distinct set of problems on

which you will provide help. However, if a participant becomes very

frustrated, it’s better to intervene than have the participant give up

completely.

As a rule of thumb, try not to give your test participants any more information than the true users of your product will have. Here are some

things you can say to the participant:

“As you’re working through the exercises, I won’t be able to provide

n

help or answer questions. This is because we want to create the most

realistic situation possible.”

n

“Even though I won’t be able to answer your questions, please ask

them anyway. It’s very important that I capture all your questions and

comments. When you’ve finished all the exercises, I’ll answer any

questions you still have.”

6. Describe in general terms what the participant will be doing.

Explain what all the materials are (such as the set of tasks, disks, and a

questionnaire) and the sequence in which the participant will use them.

Give the participant written instructions for the tasks.

If you need to demonstrate your product before the user observation

begins, be sure you don’t demonstrate something you’re trying to test.

For example, if you want to know whether users can figure out how to

use certain controls, don’t show them how to use the controls before the

session. Don’t demonstrate what you want to find out.

Involve Users in the Design Process 1-17

Page 42

CHAPTER 1

Newton and Its Users

7. Ask if there are any questions before you start; then begin

the observation.

8. During the observation, remember several pointers:

n

Stay alert. It’s very easy to let your mind wander when you’re in the

seventh hour of observing users. A great deal of the information you

can obtain is subtle.

n

Ask questions or prompt the participant. Make sure you have a tester

protocol that spells out how frequently you prompt and what you

say. Your interruptions shouldn’t be frequent, but when a participant

is hesitating or saying, “Hmmm,” ask what the participant is

thinking about.

n

Be patient; it is very easy to become impatient when someone is taking

a long time. The participant is doing you a favor and is probably

somewhat nervous. Anything you can do to alleviate the participant’s

insecurities and put the participant at ease will provide you with much

richer data.

9. Conclude the observation.

Do the following when the test is over:

Explain what you were trying to find out during the test.

n

n

Answer any remaining questions the participant may have.

n

Discuss any interesting behaviors you would like the participant

to explain.

n

Ask the participant for suggestions on how to improve the product.

10. Use the results.

As you observe, you may see users doing things you never expected them

to do. When you see participants making mistakes, your first instinct may

be to blame the mistakes on the participant’s inexperience or lack of

intelligence. This is the wrong focus to take. The purpose of observing

users is to see what parts of your product might be difficult to use or

ineffective. Therefore, if you see a participant struggling or making

mistakes, you should attribute the difficulties to faulty product design,

not to the participant.

1-18 Involve Users in the Design Process

Page 43

CHAPTER 1

Newton and Its Users

Be sure to schedule time between your sessions to make notes and review

the session. Jot down any significant points. If you used videotape or

audio cassette tape, mark in your notes the specific parts of the tape that

you may want to review.

To get the most out of your test results, review all your data carefully and

thoroughly (your notes, the videotape or cassette tape, the tasks, and so

on). Look for places where participants had trouble and see if you can

determine how your product could be changed to alleviate the problems.

Look for patterns in the participants’ behavior that might tell you whether

the product was understood correctly.

It’s a good idea to keep a record of what you found out during the test.

You don’t need elaborate video equipment; a hand-held video camera will

work. In fact, you don’t even have to use video equipment. You can use a

tape recorder to record what is spoken during the session. The important

point is that you create some kind of objective, factual record of the

session that you refer to later. That way, you’ll have documentation to

support your design decisions and you’ll be able to see trends in users’

behavior. You might want to write a report that documents the process

you used and the results you found. After you’ve examined the results

and summarized the important findings, fix the problems you found and

test the product again. By testing your product more than once, you’ll see

how your changes affect users’ performance.

Involve Users in the Design Process 1-19

Page 44

Page 45

Figure 2-0

Table 2-0

CHAPTER 2

Container Views 2

pictThis chapter describes container views, in which an application shows

the user text and graphic information, and in which the user interacts with

the information and the application. The chapter presents specifications and

recommendations about the appearance and behavior of these container

views, including how to display them on the screen, how users interact with

them, and how they interact with each other. There are several kinds of

standard container views whose regular looks enhance the visual stability of

Newton applications. The standard views provide predictable ways to see

and interact with all the different kinds of information people can create and

store on Newton devices. Figure 2-1 shows examples of container views.

There are conventions for opening, closing, moving, scrolling, and getting an

overview of container views. This means that no matter which application

people use, they know how to control container views on the screen and how

to adjust container views in the available screen space.

2-1

Page 46

CHAPTER 2

Container Views

Figure 2-1 Examples of container views

Main view

Routing slip

2-2

Ordinary slip

Palette

Alert box

Corrector view

Page 47

CHAPTER 2

Container Views

When people manipulate container views on the screen, they see immediate

visual feedback. As a user drags a movable container view, the view keeps up

with the user’s pen, reinforcing the user’s sense of direct manipulation. When

people open and close container views, they see a representation of such

actions. These mechanisms emphasize that the user is in control and can

directly manipulate “real” interface objects such as container views.

How Views Look 2

Nothing makes an application look more like it belongs—or less like it

belongs—on a Newton device than the appearance of its container views.

This section describes the key visual attributes of container views:

■ controls

■ title style

■ border style

■ fill pattern

View Controls 2

There are several standard controls for manipulating container views. These

controls include the drag handle, folder tab, Close box, local scroll arrows,

universal scroll arrows, and Overview button. The first four controls are part

of the container view they affect. The latter two controls are not part of the

container view they affect. Figure 2-2 points out the standard view controls.

For details on container view controls, see “Moving a View” on page 2-33,

“Folder Tab” on page 8-19, “Close Boxes” on page 3-14,“Scrolling” on

page 2-36, and “Overview” on page 2-44.

How Views Look 2-3

Page 48

D

rag handle

U

a

O

CHAPTER 2

Container Views

Figure 2-2 Standard controls for manipulating views

Folder tab

Local scroll

arrows

Close box

niversal scroll

rrows

verview button

View Title 2

A container view should have a title at the top unless the view’s identity is

obvious from its contents. Ordinarily a title consists of text in the bold style

of the system font, an optional small icon, and a triple underline, all centered

at the top of the view. If the title of a subordinate view is long or instructional,

2-4 How Views Look

you can left-justify it and omit the icon and the triple underline. Figure 2-3

compares different types of titles.

Page 49

Ordinary title with

ic

on

O

w

S

t

N

c

p

rdinary title

ithout icon

ubordinate view

itle—left-justified

o title—view’s

ontents make its

urpose clear

CHAPTER 2

Container Views

Figure 2-3 Various title styles

The title only identifies the container view’s contents. The title is not a control

that the user can tap to change a setting, alter a state, or initiate an action.

Controls that do these things are described in Chapter 3, “Controls.” For

example, if you want users to be able to change a view’s title, have them tap

a button or choose from a picker in the status bar.

A view title should not end with a colon. The title’s position, size, and font

make a colon unnecessary and distracting.

You capitalize view titles according to conventional rules for book titles. That

is, you capitalize the first word of a title, and you capitalize all other words

except articles (a, an, the), coordinating conjunctions (for example, and, or), and

prepositions of three or fewer letters.

On an Apple MessagePad use 10-point text for the title. The optional icon must

be no more than 11 pixels tall.

How Views Look 2-5

Page 50

CHAPTER 2

R

Container Views

View Border 2

Every container view is framed by a border. (A border is not visible if its

view fills the screen.) Primarily, a view’s border serves to demarcate what’s

in the view and what’s not. Secondarily, certain borders identify special

types of container views.

In general, Newton views are rectangular and have rounded corners.

Use square-cornered borders only when you have a specific need for a

particular look.

A view’s border is not visible if the view completely covers the screen. For

example, a MessagePad 120 user does not see the border of a view that

measures 240 × 320 pixels. The view has a border, but it is off-screen.

Matte Border 2

The most common type of view border, called a matte border, consists of a

thick gray band edged on the outside by a thin black line. Users expect views

with matte borders to be movable (see “Moving a View” on page 2-33).

Figure 2-4 shows the matte border.

Figure 2-4 A matte border indicates a movable view

ounded corners

On an Apple MessagePad a standard matte border is five pixels thick with a

corner roundness of five pixels and an inset of one pixel.

2-6 How Views Look

Page 51

CHAPTER 2

S

s

in

c

Routing slip

s

a

S

fo

t

Container Views

Striped Border 2

A border made of pairs of short, slanted lines edged by a thin black rectangle

is used around views known as routing slips (see “Routing Slips” on

page 7-12). It’s no accident that this border looks something like the border

traditionally printed on airmail envelopes, because routing slips are analogous

to postal envelopes. Figure 2-5 shows a routing slip border.

Figure 2-5 A striped border suggests routing

pecifies source

nd destination

hadow

eparates routing

formation from

ontent options

lide-out panel

r setting options

hat affect content

Square corners

The paired short lines in a striped border slant 45 degrees to the right.

Wavy Border 2

A view with a heavy black wavy border is called an alert box. It contains an

important message that a user must acknowledge. There are two types of

alert boxes; they are described in “Notification Alerts” on page 2-17 and

“Confirmation Alerts” on page 2-18. Figure 2-6 shows the wavy border of

an alert box.

How Views Look 2-7

Page 52

CHAPTER 2

Container Views

Figure 2-6 An alert box has a thick wavy border

Plain Border 2

For simplicity, some container views require a plain black border made of

medium-weight lines. Figure 2-7 shows examples of views with plain borders.

Figure 2-7 Some views need the simplicity of a plain border

Drop Shadows 2

It’s possible to add a drop shadow to a view’s bottom and right borders, but

this ersatz 3D look is not appropriate for Newton applications. Don’t use

drop shadows just because you like the way they look or because you want

to make a Newton application look like a personal computer application.

Although you shouldn’t use drop shadows, you can use another type of

shadow that tells users something about a view. For example, a shadow

2-8 How Views Look

Page 53

CHAPTER 2

Container Views

reinforces the notion that there are two parts to a routing slip—an outer part

above the shadow and an inner part below it. Figure 2-8 shows acceptable

and unacceptable uses of shadows in the Newton interface.

Figure 2-8 Sparing use of some types of shadows is OK

This plain shadow’s function is to separate

the top of the routing slip from the bottom

Don’t use decorative drop shadows on a

Newton

View Fill 2

Standard container views by default are filled with white, not with black or a