Page 1

WARRANTY.....

Top Fite

®

Model

Manufacturing Co. guarantees this kit to be free from

defects in both material and workmanship at the date of

purchase. This warranty does not cover any component

parts damaged by use or modification.In no case shall Top

Flites’liability exceed the original cost of the purchased kit.

Further, Top Flite reserves the right to change or modify

this warranty without notice.

In that Top Flite has no control over the final assembly or

material used for final assembly, no liability shall be

assumed nor accepted for any damage resulting from

the use by the user of the final user-assembled product.

By the act of using the user-assembled product, the user

accepts all resulting liability.

If the buyer is not prepared to accept the liability

associated with the use of this product, the buyer is

advised to return this kit immediately in new and unused

condition to the place of purchase.

To make a warranty claim send the defective part or item

to Hobby Services at the following address:

Hobby Services

3002 N. Apollo Dr. Suite 1

Champaign IL 61822

USA

Include a letter stating your name, return shipping

address, as much contact information as possible

(daytime telephone number , fax number, e-mail address),

a detailed description of the problem and a photocopy of

the purchase receipt. Upon receipt of the package the

problem will be evaluated as quickly as possible.

Top Flite Models Champaign, IL Telephone (217) 398-8970, Ext. 5 airsupport@top-flite.com

READ THROUGH THIS MANUAL BEFORE STARTING CONSTRUCTION. IT CONTAINS IMPORTANT INSTRUCTIONS AND WARNINGS CONCERNING THE ASSEMBLY AND USE OF THIS MODEL.

TOPZ0910 for TOPA0910 V1.0

Entire Contents © Copyright 2006

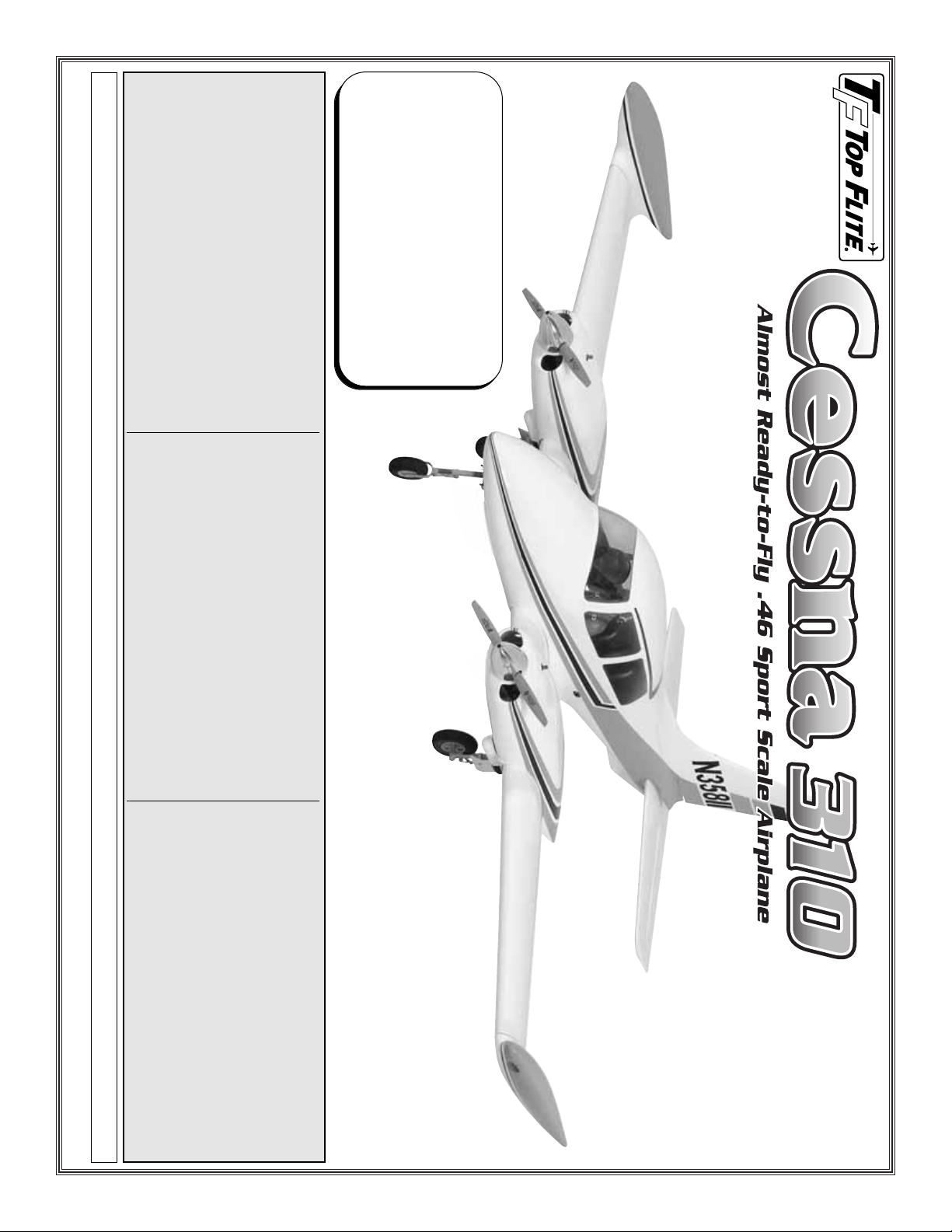

Wingspan: 81 in [2057mm]

Wing Area: 914 sq in [58.9dm

2

]

Weight: 17-20 lb [7710-9070g]

Wing Loading: 43-50 oz/sq ft

[131-153g/dm

2

]

Length: 66 in [1680mm]

Radio: 6-Channel minimum w/8 servos (8- or 9-channel

w/9 servos required for optional retracts)

Engines (2): .46-.51 cu in [7.5-8.5 cc] 2-stroke or

.70-.80 cu in [11.5-13 cc] 4-stroke

Page 2

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

SAFETY PRECAUTIONS. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

DECISIONS YOU MUST MAKE . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Radio Equipment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Engine Recommendations . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

Optional Retractable Landing Gear . . . . . . . 4

ADDITIONAL ITEMS REQUIRED. . . . . . . . . . . . 4

Adhesives and Building Supplies. . . . . . . . . 4

Optional Supplies and Tools . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

IMPORTANT BUILDING NOTES . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

ORDERING REPLACEMENT PARTS . . . . . . . . . 5

KIT CONTENTS. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

PREPARATIONS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

ASSEMBLE THE FUSELAGE STAND . . . . . . . . 7

ASSEMBLE THE WING . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Install the Ailerons and Flaps . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Mount the Plywood Engine Nacelles . . . . . . 9

Install the Flap, Throttle and Aileron

Servos and Pushrods. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Mount the Wing Tip to the Wing. . . . . . . . . 11

Install the Engine and Fuel Tank . . . . . . . . 12

Install the Fiberglass Nacelles. . . . . . . . . . 13

Install the Spinners . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Join the Wings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

ASSEMBLE THE FUSELAGE . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Install the Elevator and Rudder . . . . . . . . . 15

Install the Cockpit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Install the Radio, Elevator

and Rudder Servos. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

INSTALL THE LANDING GEAR . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Nose Gear . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Main Gear. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

RETRACTABLE LANDING GEAR . . . . . . . . . . 22

Nose Gear . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

Main Gear. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

Install the Retract Hardware . . . . . . . . . . . 25

FINAL ASSEMBLY. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

Completing the Radio Installation . . . . . . . 26

Connecting the Lighting System . . . . . . . . 26

Apply the Decals. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

GET THE MODEL READY TO FLY . . . . . . . . . . 27

Check the Control Directions. . . . . . . . . . . 27

Set the Control Throws . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

Balance the Model (C.G.) . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

Balance the Model Laterally . . . . . . . . . . . 28

Adjusting the Retractable Landing Gear. . . 29

PREFLIGHT. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

Identify Your Model . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

Charge the Batteries. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

Balance Propellers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

Ground Check. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

Range Check . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

ENGINE RUN IN INSTRUCTIONS . . . . . . . . . . 30

ENGINE SAFETY PRECAUTIONS . . . . . . . . . . 30

AMA SAFETY CODE. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

IMAA SAFETY CODE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

CHECK LIST . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

FLYING . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

Takeoff . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

Flight . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

Landing. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

Engine Out Procedure. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

INTRODUCTION

Congratulations on the purchase of your Cessna

310! This is one of the finest ARF aircraft we have

ever produced. It is an airplane that is sure to turn

heads at the field and get everyone’s attention as

soon as you are airborne. The molded fiberglass

fuselage and wing tips have faithfully re-created this

classic twin with many fine details and a tremendous

paint finish. Many of the bad tendencies of twin

engine aircraft have been engineered out of this

model so this plane is easily within the capability of

the average intermediate pilot. We are sure this

plane will bring you many hours of flying enjoyment!

For the latest technical updates or manual corrections

to the Cessna 310 visit the Top Flite web site at

www.top-flite.com. Open the “Airplanes” link, then

select the Cessna 310 ARF. If there is new technical

information or changes to this model a “tech notice”

box will appear in the upper left corner of the page.

AMA

In addition to joining a radio control club, we strongly

recommend you join the AMA (Academy of Model

Aeronautics). The AMA is the governing body of

model aviation and membership is required to fly at

AMA clubs. Though joining the AMA provides many

benefits, one of the primary reasons to join is liability

protection. Coverage is not limited to flying at

contests or on the club field. It even applies to flying

at public demonstrations and air shows. Failure to

comply with the Safety Code (excerpts printed in the

back of the manual) may endanger insurance

coverage. Additionally, training programs and

instructors are available at AMA club sites to help

you get started the right way. There are over 2,500

AMA chartered clubs across the country. Contact the

AMA at the address or toll-free phone number below:

Academy of Model

Aeronautics

5151 East Memorial Drive

Muncie, IN 47302-9252

Tele. (800) 435-9262

Fax (765) 741-0057

Or via the Internet at: www.modelaircraft.org

IMPORTANT!!!

Two of the most important things you can do to

preserve the radio controlled aircraft hobby are to

avoid flying near full-scale aircraft and avoid flying

near or over groups of people.

- 2 -

Page 3

IMAA

The Top Flite Cessna 310 is an excellent sport-scale

model and is eligible to fly in IMAA ev ents.The IMAA

(International Miniature Aircraft Association) is an

organization that promotes non-competitive flying of

giant-scale models. If you plan to attend an IMAA

event, obtain a copy of the IMAA Safety Code by

contacting the IMAA at the following address or

telephone number, or b y logging on to their web site .

IMAA

205 S. Hilldale Road

Salina, KS 67401

(913) 823-5569

www.fly-imaa.org/imaa/sanction.html.

SCALE COMPETITION

Though the Top Flite Cessna 310 is an ARF and

may not have the same level of detail as an “all-out”

scratch-built competition model, it is a scale model

nonetheless and is therefore eligible to compete in

the Fun Scale class in AMA competition (we receive

many favorable reports of Top Flite ARFs in scale

competition!). In Fun Scale, the “builder of the

model” rule does not apply.To receive the five points

for scale documentation, the only proof required that

a full size aircraft of this type in this paint/markings

scheme did exist is a single sheet such as a kit box

cover from a plastic model, a photo, or a profile

painting, etc. If the photo is in black and white other

written documentation of color must be provided.

Contact the AMA for a rule book with full details.

If you would like photos of full-size Cessna 310s for

scale documentation, or if you would like to study

the photos to add more scale details, photo packs

are available from:

Bob’s Aircraft Documentation

3114 Y uk on A ve

Costa Mesa, CA 92626

Telephone: (714) 979-8058

Fax:(714) 979-7279

www.bobsairdoc.com

1.Your Cessna 310 should not be considered a toy, but

rather a sophisticated, working model that functions very

much like a full-size airplane. Because of its

performance capabilities, the Cessna 310, if not

assembled and operated correctly, could possibly cause

injury to yourself or spectators and damage to property.

2. You must assemble the model according to the

instructions. Do not alter or modify the model, as

doing so may result in an unsafe or unflyable model.

In a few cases the instructions may diff er slightly from

the photos.In those instances the written instructions

should be considered as correct.

3.You must take time to build straight, trueand strong.

4.You must use an R/C radio system that is in first-

class condition, and correctly sized engines and

components (fuel tank, wheels, etc.) throughout the

building process.

5. You must correctly install all R/C and other

components so that the model operates correctly on

the ground and in the air.

6. You must check the operation of the model before

every flight to insure that all equipment is operating and

that the model has remained structurally sound.Be sure

to check clevises or other connectors often and replace

them if they show any signs of wear or fatigue.

7. If you are not an experienced pilot or have not flown

this type of model before, we recommend that you get

the assistance of an experienced pilot in your R/C club

for your first flights.If you’ re not a member of a club , your

local hobby shop has information about clubs in your

area whose membership includes experienced pilots.

8. WARNING: The cowl, fuselage, nacelles and tail

cone included in this kit are made of fiberglass, the

fibers of which may cause eye, skin and respiratory

tract irritation. Never blow into a part to remove

fiberglass dust, as the dust will blow back into your

eyes. Always wear safety goggles, a particle mask

and rubber gloves when grinding, drilling and sanding

fiberglass parts.Vacuum the parts and the work area

thoroughly after working with fiberglass parts.

Remember: Take your time and follow the

instructions to end up with a well-built model that

is straight and true.

DECISIONS YOU MUST MAKE

This is a partial list of items required to finish the

Cessna 310 that may require planning or decision

making before starting to build. Order numbers are

provided in parentheses.

RADIO EQUIPMENT

Transmitter and Receiver

A minimum of a 6 channel radio is required but

because of the number of servos in this model you

may wish to eliminate the use of “Y” connectors. An

8- or 9- channel radio may be preferable.

Servos

(2) 40 oz-in servos for the throttles

(1) 40 oz-in servo for the retract (optional)

(6) 54 oz-in servos 2-flaps, 2-ailerons,

1-rudder, 1-elevator

We, as the kit manuf acturer , pro vide you with a top

quality, thoroughly tested kit and instructions, but

ultimately the quality and flyability of your finished

model depend on how you build it; therefore, we

cannot in any way guarantee the performance of

your completed model, and no representations

are expressed or implied as to the performance or

safety of your completed model.

PRO TECT YOUR MODEL,

YOURSELF & OTHERS

FOLLO W THESE IMPORT ANT

SAFETY PRECAUTIONS

- 3 -

Page 4

Servo Extensions

(3) Y-har ness (HCAM2751 for Futaba

®

)

(4) 6" [150mm] extension (HCAM2701 for Futaba)

(2) 12" [300mm] extension (HCAM2711 for Futaba)

(4) 24" [610mm] extension (HCAM2721 for Futaba)

Batteries

1000 mAh NiCd battery for the receiver

500 mAh NiCd battery for the lighting system

ENGINE RECOMMENDATIONS

Engine

The recommended engine size for the Cessna 310 is

a .46-.50 two-stroke. This airplane was extensively

flown on the O.S.

®

.46AX two stroke engines and

Bisson muffler. Though your instincts might tell you

that a plane of this size and weight will be

underpowered with these engines, this is not true.

During our test flights we used these engines for

taking off from grass and asphalt with no problems.

The climb out from take off was impressive. Once the

plane was at altitude the plane was flown at 1/2 to 3/4

throttle. As par t of our testing the plane was flown on

a single engine from both the right and left nacelle.

The O.S. .46 was enough power to maintain flying

altitude, fly a figure eight, and a rectangle approach to

the runway. The airplane has the power to fly on one

engine but not enough to climb out from a missed

landing approach.The O.S..46 or .50 SX is the engine

of choice to keep ev erything hidden under the nacelle.

Muffler

The Bisson Pitts Muffler (BISG4046) fits very well in

the nacelle and is the recommended after market

muffler for the Cessna 310.

OPTIONAL RETRACTABLE

LANDING GEAR

Robart Cessna 310 Retracts (ROBQ1623)

Robart Standard Air Kit with variable

rate valve (ROBQ2302)

10' [1meter] Pressure tubing (ROBQ2369)

(2) Air line quick disconnects (ROBQ2395)

ADDITIONAL ITEMS REQUIRED

ADHESIVES & BUILDING SUPPLIES

This is the list of Adhesives and Building Supplies

that are required to finish the Cessna 310.

❏ 3' [900mm] standard silicone fuel

tubing (GPMQ4131)

❏ 1/2 oz. [15g] Thin Pro

™

CA (GPMR6001)

❏ 1 oz. [30g] Medium Pro CA+ (GPMR6008)

❏ Pro 30-minute epoxy (GPMR6047)

❏ Pro 6-minute epoxy (GPMR6045)

❏ Drill bits: 1/16" [1.6mm], 5/64" [2mm], 3/32"

[2.4mm], 7/64" [2.8mm], 1/8" [3.2mm], 11/64"

[4.4mm]

❏ Silver solder w/flux (GPMR8070)

❏ #1 Hobby knife (HCAR0105)

❏ #11 blades (5-pack, HCAR0211)

❏ Medium T-pins (100, HCAR5150)

❏ Masking tape (TOPR8018)

❏ Threadlocker thread locking cement (GPMR6060)

❏ Denatured alcohol (for epoxy clean up)

❏ Hot melt glue and glue gun (available at hobby,

craft and hardware outlets)

OPTIONAL SUPPLIES & TOOLS

Here is a list of optional tools mentioned in the

manual that will help you build the Cessna 310.

❏ 21st Century

®

sealing iron (COVR2700)

❏ 21st Century iron cover (COVR2702)

❏ 4 oz. [113g] aerosol CA activator (GPMR634)

❏ CA applicator tips (HCAR3780)

❏ Epoxy brushes (6, GPMR8060)

❏ Mixing sticks (50, GPMR8055)

❏ Mixing cups (GPMR8056)

❏ Hobbico Duster

™

compressed air (HCAR5500)

❏ Rotary tool such as Dremel

®

❏ Rotary tool reinforced cut-off wheel (GPMR8020)

❏ Servo horn dr ill (HCAR0698)

❏ Dead Center

™

Engine Mount Hole

Locator (GPMR8130)

❏ AccuThrow

™

Deflection Gauge (GPMR2405)

❏ CG Machine

™

(GPMR2400)

❏ Precision Magnetic Prop Balancer (TOPQ5700)

IMPORTANT BUILDING NOTES

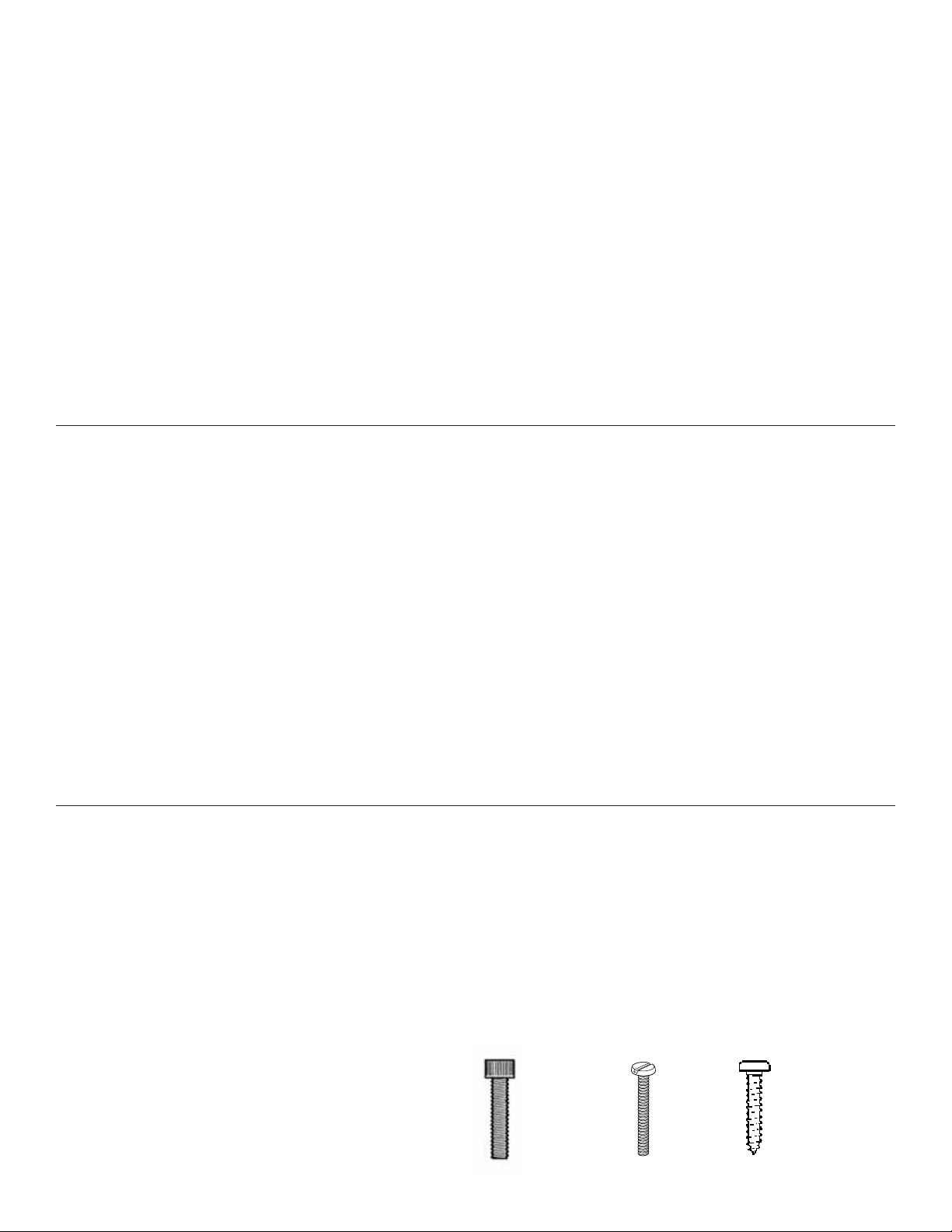

• There are two types of screws used in this kit:

Sheet metal screws are designated by a number

and a length. For example #6 x 3/4" [19mm]

This is a number six screw that is

3/4" [19mm] long.

Machine screws are designated by a number, threads

per inch, and a length.For example 4-40 x 3/4" [19mm]

This is a number four screw that

is 3/4" [19mm] long with forty

threads per inch.

Socket head cap screws are designated by a

number, threads per inch and a length.For example

4-40 x 3/4" [19mm]

This is a number four screw that

is 3/4" [19mm] long with forty

threads per inch

.

• When you see the term test fit in the instructions, it

means that you should first position the part on the

assembly without using any glue, and then slightly

modify or custom fit the part as necessar y for the

best fit.

•Whenever the term glue is written you should rely upon

your experience to decide what type of glue to use.

When a specific type of adhesive works best for that

step, the instructions will make a recommendation.

• Whenever just epoxy is specified you may use

either 30-minute (or 45-minute) epoxy or 6-minute

epoxy. When 30-minute epoxy is specified it is

highly recommended that you use only 30-minute

(or 45-minute) epoxy, because you will need the

working time and/or the additional strength.

• Photos and sketches are placed bef ore the step they

refer to .Frequently you can study photos in follo wing

steps to get another view of the same parts.

- 4 -

Page 5

• The Cessna 310 is factory-covered with Top Flite

MonoKote

®

film. Should repairs ever be required,

MonoKote can be patched with additional MonoKote

purchased separately. MonoKote is packaged in six-

foot rolls, but some hob by shops also sell it by the f oot.

If only a small piece of MonoKote is needed for a

minor patch, perhaps a fellow modeler would giv e y ou

some. MonoKote is applied with a model airplane

covering iron, but in an emergency a regular iron could

be used. A roll of MonoKote includes full instructions

for application. Following are the colors used on this

model and order numbers for six foot rolls.

White - TOPQ0204

Sky Blue - TOPQ0206

Insignia Blue - TOPQ0207

METRIC CONVERSIONS

To convert inches to millimeters, multiply inches by 25.4

.4mm = 1/64"

.8mm = 1/32"

1.6mm = 1/16"

2.4mm = 3/32"

3.2mm = 1/8"

4mm = 5/32"

4.8mm = 3/16"

6.4mm = 1/4"

9.5mm = 3/8"

12.7mm = 1/2"

15.9mm = 5/8"

19mm = 3/4"

25.4mm = 1"

50.8mm = 2"

76.2mm = 3"

152.4mm = 6"

304.8mm = 12"

381mm = 15"

457.2mm = 18"

533.4mm = 21"

609.6mm = 24"

762mm = 30"

914.4mm = 36"

ORDERING REPLACEMENT PARTS

Replacement parts for the Top Flite Cessna 310 are

available using the order numbers in the

Replacement Parts List that follows. The fastest,

most economical service can be provided by your

hobby dealer or mail-order company.

To locate a hobby dealer, visit the Hobbico web site

at www.hobbico.com. Choose “Where to Buy” at the

bottom of the menu on the left side of the page.

Follow the instructions provided on the page to

locate a U.S., Canadian or International dealer.

Parts may also be ordered directly from Hobby

Services by calling (217) 398-0007, or via facsimile

at (217) 398-7721, but full retail prices and shipping

and handling charges will apply. Illinois and Nevada

residents will also be charged sales tax. If ordering

via fax, include a Visa

®

or MasterCard

®

number and

expiration date for payment.

Mail parts orders and payments by personal check to:

Hobby Services

3002 N Apollo Drive, Suite 1

Champaign IL 61822

Be certain to specify the order number exactly as

listed in the Replacement Parts List. Payment by

credit card or personal check only; no C.O.D.

If additional assistance is required for any reason

contact Product Support at:

(217) 398-8970

productsupport@greatplanes.com

REPLACEMENT PARTS LIST

Description How to purchase

Missing pieces Contact Product Support

Instruction manual Contact Product Support

Full-size plans Not available

Order # Description

TOPA1660 Wing Set

TOPA1661 Fuselage Set

TOPA1662 Wing Tip Set

TOPA1663 Tail Set

TOPA1664 Left Engine Pod

TOPA1665 Right Engine Pod

TOPA1666 Landing Gear

TOPA1667 Decal Set

TOPA1668 Wing Tubes (2)

TOPA1669 Tail Tubes (2)

TOPA1670 Windshield/Windows

TOPA1671 Gear Doors

TOPA1672 Aluminum Spinner

TOPA1673 Tail Cone

TOPA1674 Rudder

- 5 -

Page 6

- 6 -

PARTS NOT PHOTOGRAPHED

(2) 2-56 Metal Clevis

(1) 4-40 Threaded Metal Clevis

(2) 4-40 Solder Clevis

(4) Brass Screw Lock Connector

(2) 4-40 Nut

(8) 6-32 Blind Nut

(2) 8-32 Blind Nut

(2) 2-56 Nut

(3) .080 Nut

(7) 1/4-20 Blind Nut

(2) Large Nylon Control Horn

(6) 1/4-20 Bolts

(4) 2-56 Nylon Clevis

(2) Large Black Control Horn

(1) 2-56 Nylon Ball Link Socket

(4) Nylon Retainer

(2) CA Hinge Strip

(5) Faslink

(2) 36" Gray outer Pushrod Tube

(9) Silicone Clevis Keeper

(8) #4 x 1/2" [13mm] Sheet

Metal Screw

(2) 4-40 x 1/4" [6mm] SHCS

(32) #2 x 3/8" [10mm] SMS

(16) #6 x 1/2" [13mm] SMS

(4) 8-32 x 1" [25mm] Slotted MS

16 6-32 x 3/4" [19mm] SHCS

(3) .080 Ball

(8) #2 x 3/8" [10mm] Wood Screw

(2) 8-32 x 1" [25mm] SHCS

(4) 4-40 x 1/8" [3mm] SHS

(8) #2 x 1/2" [13mm] SMS

(2) .074 x12" Wire [305mm]

(5) .074 x 6" [152mm] Wire

(2) 4-40 x 36" [914mm] Threaded Rod

(32) #6 Flat Washer

(2) #4 Flat Washer

(20) #2 Flat Washer

(2) #8 Lock Washer

(14) #8 Flat Washer

(28) #6 Lock Washer

(4) Crimp Connector

(1) 1/4-20 Thumb Screw

(4) Flat Nylon Strap

(4) Humped Landing Gear Strap

(3) 4x200mm Nylon Tie Strap

(1) .5 x 1000mm Cable

(2) 8x40mm Nylon Dowel with Pin

(4) 8x30mm Nylon Dowel

(2) 2-56 Brass Connector

(8) Pinned Hinge

(2) Aluminum Door Mount Brackets

(8) 2 x 10mm Screws

(8) 2mm Nuts

(6) Wheel Collars and Set Screws

(3) Fiberglass Landing Gear Doors

(1) 4-40 x 12" [305mm] Fully

Threaded Rod

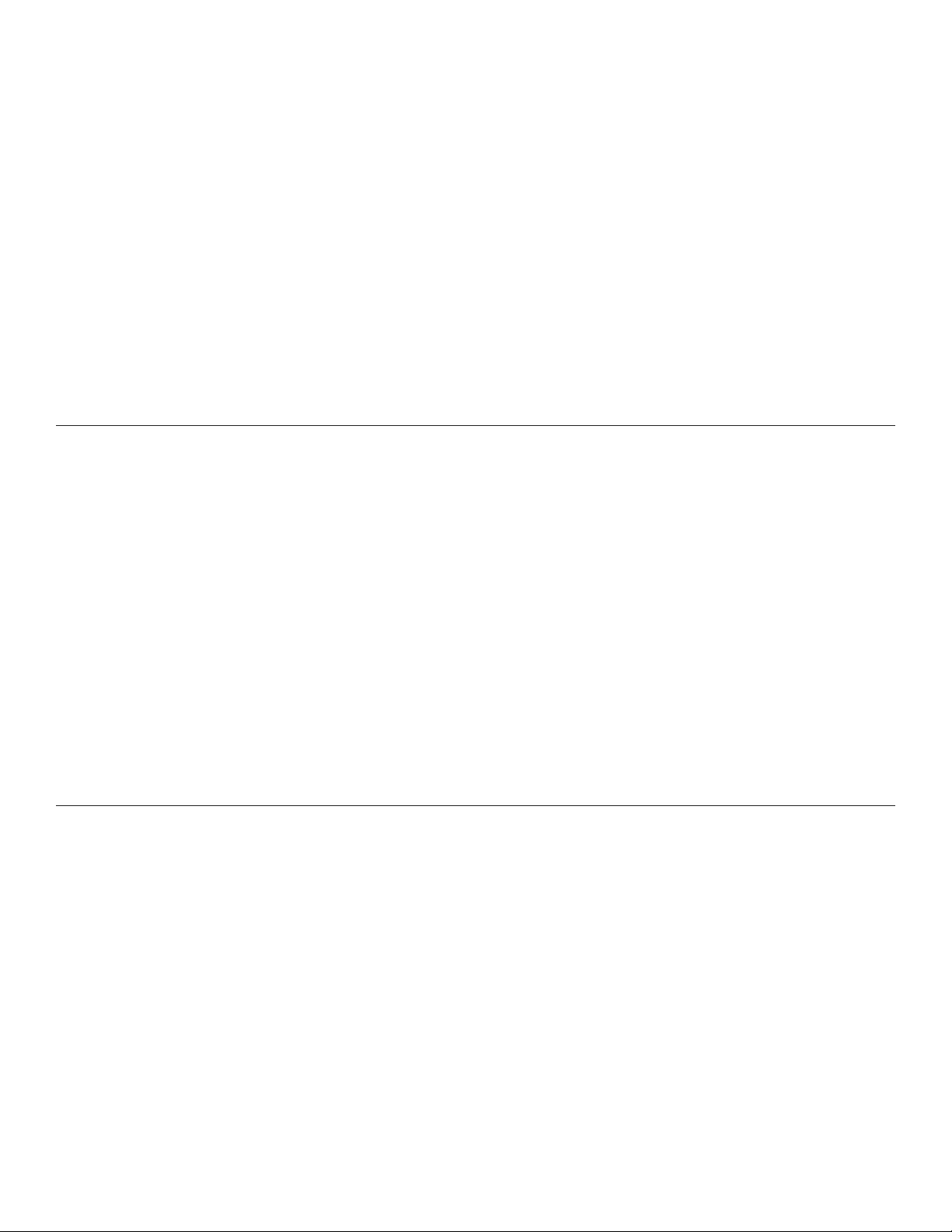

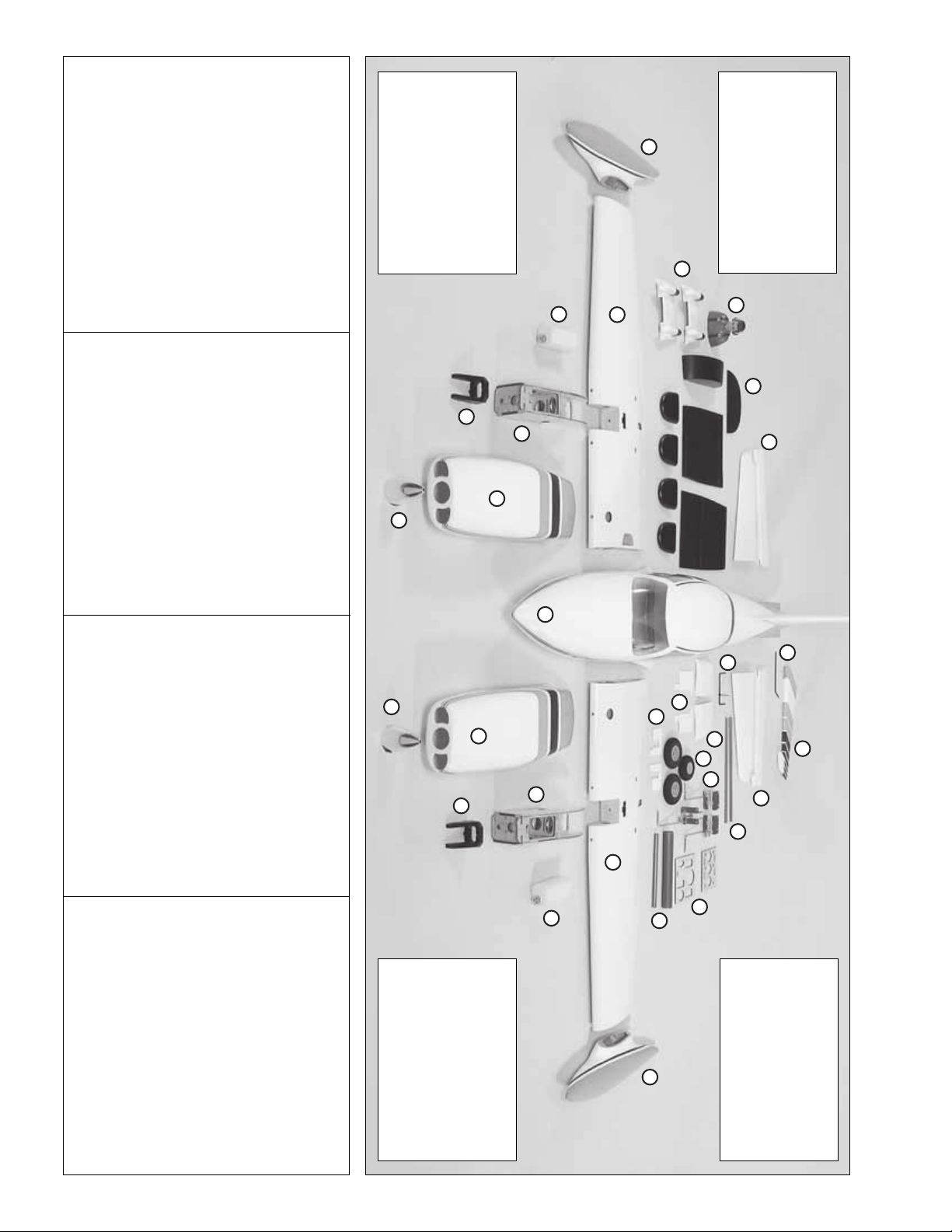

KIT CONTENTS

1. Fuselage

2. Nacelles (L&R)

3. Spinners

4. Engine Mounts

5. Fuel Tanks

6. Wood Nacelle (Left)

14. Pilot

15. Wing Fairing (L&R)

16. Gear Door (L&R)

17. Landing Gear Covers

18. Wheels

19. Landing Gear

7. Wood Nacelle (Right)

8. Wing Half (Left)

9. Wing Half (Right)

10. Wing Tip (Right)

11. Wing Tip (Left)

12. Lower Nacelle Covers

13. Cockpit Kit

20. Ser vo and Battery Tray

21. Wing Joiner Tubes

22. Stab T ubes

23. Elevator Joiner Wire

24. Stabilizer (L&R)

25. Rudder Control Wire

26. Rudder

10

12

4

3

3

4

5

7

2

9

14

13

24

1

23

16

17

2

6

15

18

19

22

25

26

24

8

5

11

20

21

Page 7

- 7 -

PREPARATIONS

❏ 1. If you have not done so already, remove the

major parts of the kit from the box and inspect for

damage. If any parts are damaged or missing,

contact Product Support at the address or telephone

number listed in the “Ordering Replacement Parts”

section on page 5.

❏ 2.Remove the tape and separate the ailerons and

flaps from the wing and the elevators from the stab.

Use a covering iron with a covering soc k on high heat

to tighten the covering if necessary. Apply pressure

over sheeted areas to thoroughly bond the covering

to the wood.

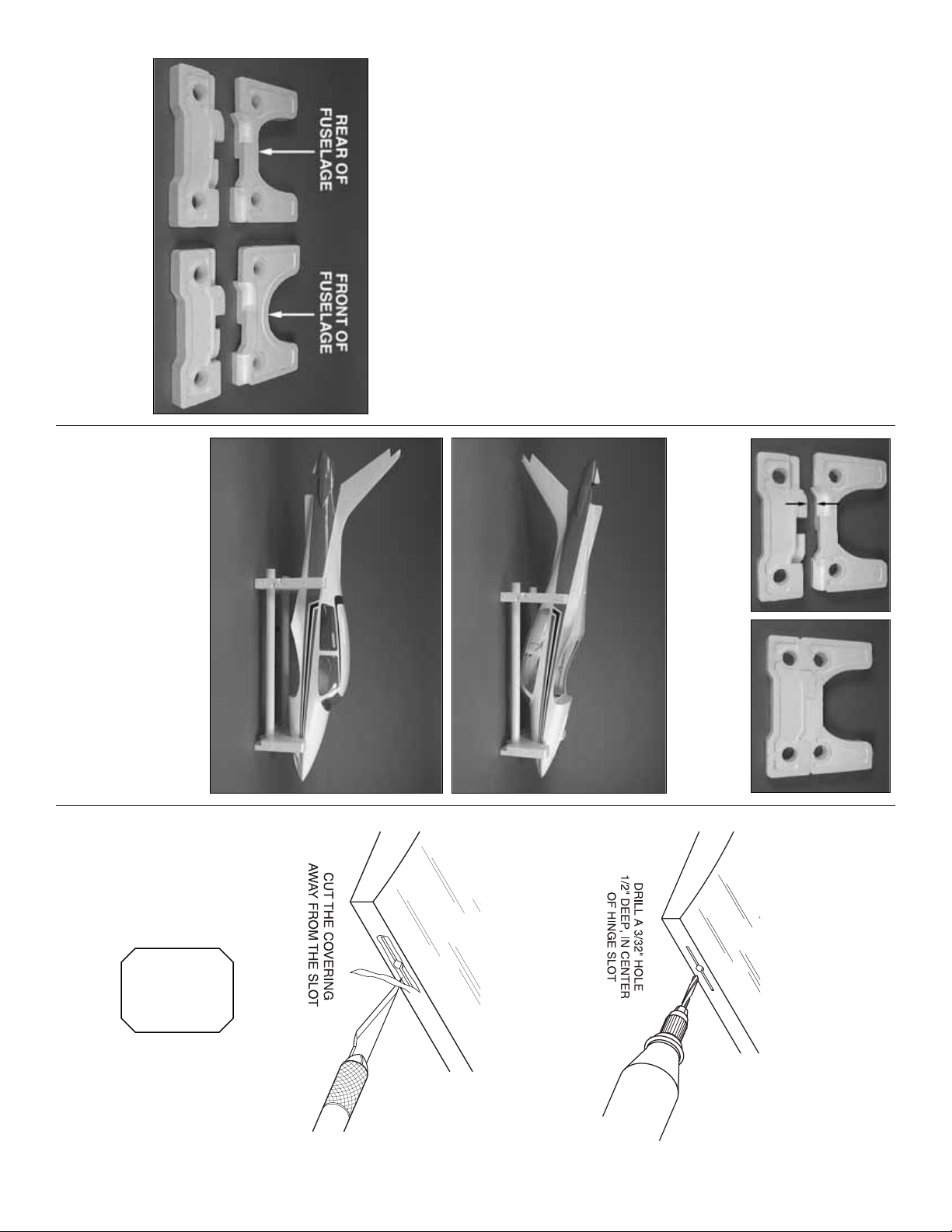

ASSEMBLE THE FUSELAGE STAND

Your kit includes a stand that can be used during the

assembly process and as a useful tool for transporting

the airplane to the field as well as assembly of the

airplane at the field.

❏ 1. The stand consists of four foam cradle

components and two PVC tubes. There are two

different cutouts in the cradle.The curved section fits

the front of the fuselage while the one that has the

flat cut fits the rear half of the fuselage.

❏ 2. The top and bottom stand components will fit

snugly together. Fit the bottom with the top cradle

(the one with the flat cut) as shown.

❏ 3. When placed into the cradle upside down the

fuselage is elevated so the tail and the cabin top are off

of your work bench. You can also place the fuselage

upright in the cradle.If you install the fixed landing gear

and wish to transport the fuselage or work on it on your

workbench, you will want to place the other bottom

cradle component onto the front cradle.This will allow

enough clearance for the nose gear.

ASSEMBLE THE WING

Install the Ailerons and Flaps

Assemble the right wing first so your

work matches the photos.

❏❏1. Drill a 3/32" [2.4mm] hole, 1/2" deep in the

center of each hinge slot to allow the CA to “wick”in.

Follow-up with a #11 blade to clean out the slots.

Hint: If you ha v e one , use a high-speed rotary tool to

drill the holes.

❏❏2. Use a sharp #11 blade to cut a strip of

covering from the hinge slots in the wing and aileron.

❏❏3.Cut three 1" x 1" [25mm x25mm] hingesfrom

the CA hing e strip. Snip off the corners so they go

in easier.

Page 8

❏❏4. Test fit the ailerons to the wing with the

hinges.If the hinges don’t remain centered, stick a pin

through the middle of the hinge to hold it in position.

❏❏5.Remove any pins you may have inserted into

the hinges. Adjust the aileron so there is a small gap

between the LE of the aileron and the wing.The gap

should be small, just enough to see light through or

to slip a piece of paper through.

❏❏6. Apply six drops of thin CA to the top and

bottom of each hinge. Do not use CA accelerator.

After the CA has fully hardened, test the hinges by

pulling on the aileron.

❏❏7. If you have not removed the flap from the

wing, do so. Locate four nylon pinned hinges. Apply

a drop of oil or work Vaseline into the hinge. This will

prevent glue from getting into the hinge in the next

step. Be careful not to get oil on the portion of the

hinge that slides into the wing and flap.If this should

happen be sure to clean the hinge with alcohol

before applying the glue.

❏❏8. Apply epoxy to one end of each hinge and

into each of the four holes in the wing trailing edge in

the flap compartment. Insert the hinge into the hole,

positioning the hinge as shown.

❏❏9. Apply epoxy to the opposite end of the hinge

and the hinge holes in the flap.Insert the flap onto the

hinges. Set the wing aside until the glue has cured.

❏ 10. Repeat steps 1- 9 for the left wing panel.

- 8 -

Page 9

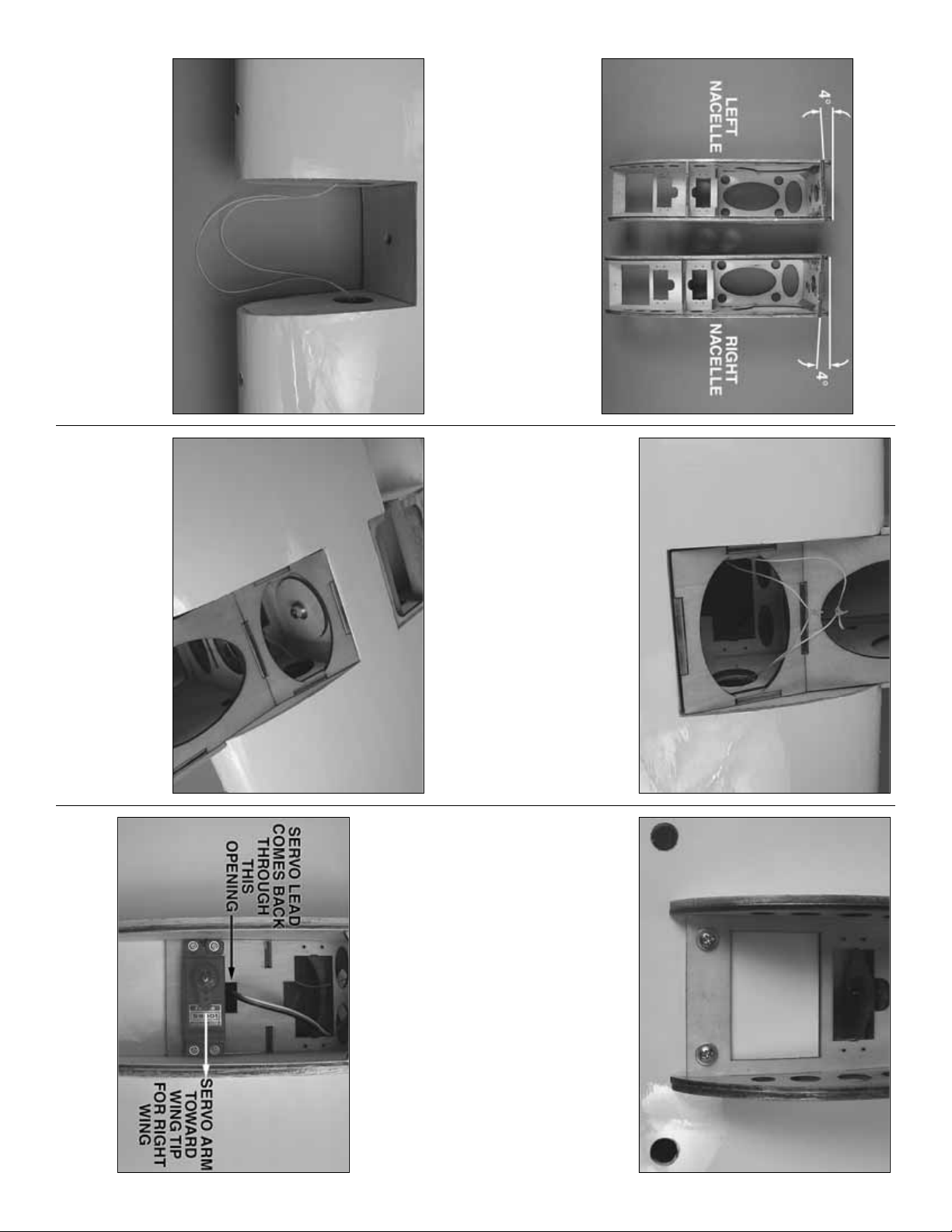

Mount the Plywood Engine Nacelles

❏

1. Remove the top plate and fuel tank from the

plywood engine nacelle. Set the two plywood

engine nacelles on your workbench as shown in the

photograph. Looking at the top of the nacelle you

must note the difference in the angle of the firewall

of each nacelle. Each nacelle has 4° of outward

thrust built into it. Write the word “left” and “right” on

each nacelle so you can easily identify each one.

❏❏2. The wing has strings running through it for

pulling servo leads through the wing.The string is taped

at the root rib, the wing tip and inside the aileron servo

compartment. Remove the tape and pull the excess

string into the front of the wing where the nacelle will be

mounted. Re-tape the end of the string to the rib.

❏❏3.Cut the strings.Begin sliding the right nacelle

in place and at the same time feed the string through

the holes in each side of the nacelle. Re-tie the

strings.Apply a drop of thin CA to the knot to prevent

it from coming apart.

❏❏4. Slide the nacelle completely into the wing.

Attach the nacelle to the wing with an 8-32 x 1"

[25mm] socket head cap screw, a #8 lock washer

and a #8 flat washer. Apply a couple of drops of

thread locker onto the bolt before tightening the bolt

to the wing and nacelle.

❏❏5. Drill 3/32" [2.4mm] holes through each of the

two pilot holes located at the back of the nacelle.Drill

through the nacelle and into the hardwood block

located in the wing. Inser t and remove a #6 x 1/2"

[13mm] screw into each of the holes.Apply a couple

drops of thin CA into the holes to harden the threads.

Once the glue has cured install the #6 screws and #6

flat washers into each of the holes.

❏ 6. Repeat steps 1- 5 for the left wing panel.

Install Flap,Throttle and Aileron

Servos and Pushrods

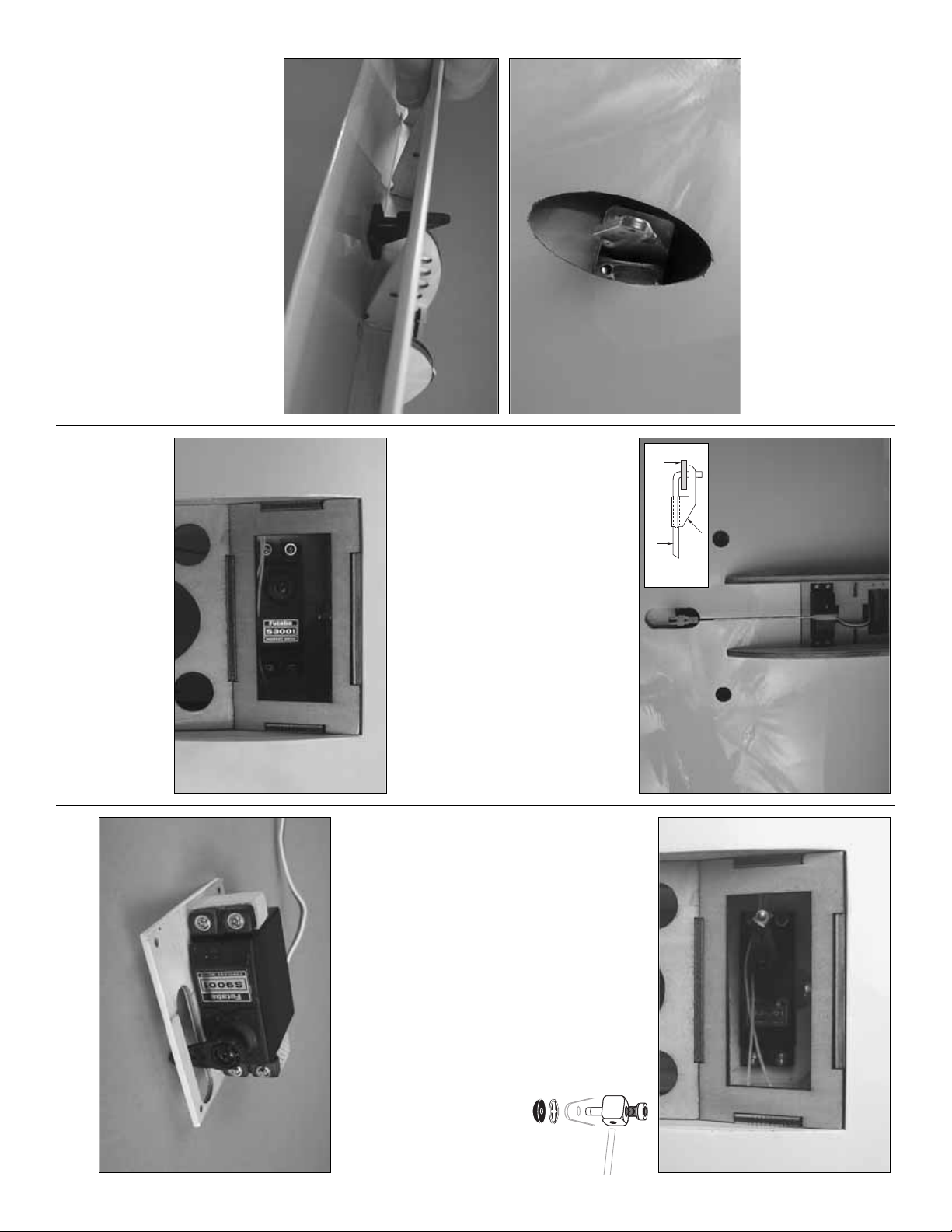

❏❏1.Install the flap servo into the rear servo opening.

Insert and remove a servo mounting screw into each of

the pre-drilled holes. Apply a couple drops of thin CA

- 9 -

Page 10

into the holes to harden the threads.Once the glue has

cured re-install the servo mounting screws.Be sure the

servo lead comes up through the slot alongside of the

servo. When installing the flap ser vo in the right wing

panel, the servo arm should be pointed towards the

wing tip.When installing the servo in the left wing, the

arm should be pointed towards the wing center.

❏❏2. Center a black control horn in the opening

above the flap , positioning it as shown (the control horn

should be backwards from what would be considered

the normal direction of a control horn.) Drill a 1/16"

[1.6mm] hole through each of the mounting holes in the

control horn and into the plywood plate in the flap.Drill

only through the plywood plate. DO NOT drill through

the flap. Inser t and remove a #2 x 3/8" [10mm] screw

into each of the holes.Apply a couple drops of thin CA

into the holes to harden the threads.Once the glue has

cured attach the horn to the flap with four

#2 x 3/8" [10mm] screws.

❏❏3.Screw a nylon clevis onto a .074 x 6" [152mm]

threaded wire 20 turns. Slide a nylon clevis retainer

onto the clevis. Install the clevis into the outermost

hole of the control horn. Then slide the silicone

retainer over the clevis. Drill a 5/64" [2mm] hole in the

outer hole of the servo arm. Position the servo arm as

shown and be sure the flap is fully closed.With a fine

tip marker, mark the wire where it aligns with the outer

hole of the servo arm. Make a 90 degree bend on the

mark. Cut the wire so the wire is 3/8" [10mm] in length

after the bend. Insert the wire into the servo arm and

lock it in place with a nylon Faslink.

❏❏4. Install the throttle ser vo into the servo opening.

(Note that the servo is mounted on the bottom of the

nacelle).Insert and remove a servo mounting screw into

each of the pre-drilled holes.Apply a couple drops of thin

CA into the holes to harden the threads. Once the glue

has cured, re-install the servo mounting screws.

❏❏5. Install a brass screw lock

connector, nylon retainer ring and a

4-40 x 1/4" [6mm] socket head cap

screw onto the servo arm. Then

center the servo and install the arm

onto the servo.

❏❏6. Install a 6" [152mm] servo extension onto the

throttle and flap servo leads. Secure the extension to

the lead with tape, a piece of shrink tube or some

other method to keep them from coming unplugged.

❏❏7. Install a 24" [610mm] servo extension onto

the aileron servo lead. Secure the extension to the

lead with tape, a piece of shrink tube or some other

method to keep them from coming unplugged.

❏❏8. Install the aileron servo between the wooden

rails under the aileron servo cover using the

- 10 -

SERVO

HORN

PUSHROD WIRE

2-56 (.074")

FASLINK

Page 11

- 11 -

hardware that came with the servo. Drill a 1/16"

[1.6mm] hole through each of the servo mounting

holes and into the servo mounting rails. Inser t and

remove a servo mounting screw into each of the

holes. Apply a couple drops of thin CA into the holes

to harden the threads. Once the glue has cured,

re-install the servo mounting screws.

❏❏9. Center the servo.Then, install a large ser vo

horn to the servo.

❏❏10. Tie the string from the ser vo compartment

to the servo lead. Pull the lead through the wing

exiting at the nacelle.Leave the string attached to the

lead for now.

❏❏11. Install the aileron ser vo cover to the wing

with four #2x 3/8"[10mm] wood screws.

❏❏12.Look closely under the covering of the aileron

and you will see a plywood mounting plate for the

control horn. Place a nylon clevis on the plate in line

with the servo arm. Mark the location of the mounting

holes onto the aileron. Drill a 1/16" [1.6mm] hole on

the marks, drilling through the plywood plate

but not

through the top of the aileron. Insert and remove a #2

x3/8" [10mm] screw into each of the holes. Apply a

couple drops of thin CA into the holes to harden the

threads. Once the glue has cured, attach the horn to

the aileron with two #2 x 3/8" [10mm] screws.

❏❏13.Screw a nylon clevis onto a .074 x 6" [152mm]

threaded wire 20 turns.Slide a nylon clevis retainer onto

the clevis.Install the clevis into the second hole from the

end of the control horn. Then slide the silicone retainer

over the cle vis.Drill a 5/64" [2mm] hole in the outer hole

of the servo arm. Center the servo and position the

servo arm as shown. Then, center the aileron. With a

fine tip marker, mark the wire where it aligns with the

outer hole of the servo arm. Make a 90 degree bend on

the mark. Cut the wire so the wire is 3/8" [10mm] in

length after the bend.Insert the wire into the servo arm

and lock it in place with a nylon Faslink.

❏ 14. Repeat steps 1- 13 for the left wing panel.

Mount the Wing Tip to the Wing

❏❏1. Glue two 1/4" x1/4" x 3/4" [6mm x 6mm x

19mm] balsa triangle blocks onto each side of the

slot in the wing.

❏❏2.Examine both wing tips to determine which is

the left and the right. When installed on the wing the

tip should curve upward towards the top of the wing.

❏❏3. Pull the wires for the wing tip lights from

inside of the wing tip. Tie the end of the wire to the

string located on the end of the wing. Pull the wire

through the wing exiting at the nacelle. Note: at this

point all of the servo leads and the wire for the light

should be at the nacelle.

Page 12

❏❏4. Test fit the wing tip to the wing. Once you’re

satisfied everything fits, apply epoxy into the pocket

in the end of the wing, the plywood tongue on the

wing tip, the tip of the wing and the root rib of the

wing tip. Tape the wing tip to the wing. Set it aside

until the glues has cured.

❏❏5. At this point the servo leads as well as the

lead for the wing tip lights should be located at the

nacelle. Untie both of the strings from the servo

leads.If you will be installing retractable landing gear,

tape one of the strings to the wing. This will be used

later to pull the air lines through the wing. Tie all of

the leads to the other string. If you will be installing

fixed gear tie two leads to each string.This will make

it easier to pull the leads through the wing. Pull all of

the servo leads and the wing tip light wire through

the wing, exiting through the hole in the top of the

wing.Untie the leads and then tape all of the leads to

the top of the wing, preventing the leads from falling

back into the wing. If you are installing retracts be

sure to leave the string taped to the root rib.

❏ 6. Repeat steps 1- 5 for the left wing panel.

Install Engine and Fuel Tank

❏❏1. Cut the tabs from the engine mount. Install

the engine mount to the firewall with four 6-32x 3/4"

[25mm] socket head cap screws , #6 flat washers and

#6 lock washers.

❏❏2. Position the engine on the engine mount so

the distance from the firewall to the thrust washer

measures 4-5-8" [118mm]. Mark the location of the

mounting holes onto the engine mount. Drill and tap

the engine mount with a 6-32 tap for each of the four

bolts.Mount the engine to the mount with four 6-32 x

3/4" [25mm] socket head cap screws , #6 flat washers

and #6 lock washers.

❏❏3. Assemble the fuel tank as shown in the

sketch.When tightening the center screw be sure not

to over tighten it.You just want it snug enough to pull

the rubber stopper tight against the tank.

❏❏4.Install the tank into the fuselage with the neck

of the tank through the firewall.

- 12 -

SILICONE

FUEL LINE

FUEL TANK

FUEL CLUNK

FUEL

PIPE

FIREWALL

TO NEEDLE

VALVE

PRESSURE

TAP TO

MUFFLER

Page 13

❏❏5. From one of the 1/4" x 1/4" x 12" [6mm x 6mm

x 305mm] balsa sticks, cut two sticks to a length of 1"

[25mm]. Insert them into the square openings on each

side of the bottom of the nacelle. Make sure they

extend into the nacelle far enough to support the fuel

tank.Then, glue them in place.

❏❏6. Install silicone fuel tubing onto the aluminum

tubes from the fuel tank. The line with the fuel clunk

will feed to the fuel inlet at the needle valve and the

other will attach to the pressure tap on the muffler.If

you choose to use some kind of an external fuel

valve, follow the instructions with your particular

brand of fuel valve.You can also install a third line to

the tank and use it for filling the tank.The method you

use is your choice but make your decision before

moving onto the installation of the fuel tank.

❏❏7 Install a brass screw lock connector, nylon

retainer ring and a 4-40 x 1/4" [6mm] socket head cap

screw onto the throttle arm on the engine. Cut the

threaded portion off of a 2-56 x 12" [305mm] pushrod

wire. Slide the wire through the screw lock connector

on the throttle arm, pushing it back towards the throttle

servo.Bend the wire as needed to clear the top of the

fuel tank and reach the screw lock connector. Tighten

the set screws against the wire pushrod.

❏❏8. Epoxy the top of the nacelle in place.

A note about the muffler: A wide variety of mufflers

are available. On our O.S .46 we used the Bison

muffler (BISG4046) and cut the pipes to a length of

3/8" [10mm]. This allowed the cowl to slip over the

engine and muffler yet still allows the e xhaust to clear

the inside of the nacelle. Cut the pipes as shown.

Leave the muffler off the engine for now. This will

make the installation of the fiberglass nacelle easier.

❏ 9. Repeat steps 1- 8 for the left wing panel.

Install Fiberglass Nacelle

❏❏1. Glue two of the 1/4 x 1-1/8" [6mm x 30mm]

nylon dowels into the leading edge of the wing on

each side of the nacelle with epoxy. The dowels

should extend from the leading edge of the wing

approximately1/2" [13mm].

❏❏2. Place the two nacelles side by side. Each

have outboard thrust angles built into the front of the

nacelle. Identify the right and left and mar k this on

the inside of the nacelle.

- 13 -

Page 14

❏❏3. Slide the nacelle over the engine and onto

the locating dowels on the leading edge of the wing.

Note: You may have to remove the needle valve

and/or the needle valve spring to get the nacelle

completely over the engine.Secure the nacelle to the

wing with two 1/4-20 x 2" [51mm] nylon bolts on the

bottom of the wing.

❏❏4. Place the nacelle belly pan onto the bottom

of the wing, placing it tight against the nacelle.Drill a

1/16" [1.6mm] hole at the location shown, making

sure to drill only through the wood under the pan.

Install and then remove a #2 x 1" [25mm] sheet metal

screw into each of the holes. Apply a few drops of

thin CA into the holes. After the glue has cured,

screw the belly pan in place.

❏❏5. Make the necessary cut-outs for the needle

valve, muffler, glow driver, etc.

❏❏6. It is very important that you provide an air

exhaust to allow the engine to be cooled properly.

With the engine completely cowled, you must provide

approximately 5 sq. in. [.35 dm

2

] of exhaust area on

the bottom of the wing nacelle.

❏❏7. Epoxy one of the two 5/16 x 1-1/2" [8mm x

40mm] nylon dowels with the steel pin in its center

into the hole in the leading edge of the wing. Insert

the pin fully into the hole in the leading edge.

❏ 8. Repeat steps 1-7 for the other wing.

Install the Spinners

❏❏Install the spinners to the engine with the

hardware included with the spinners.When mounting

the propellers you will need to use the nut that came

with the spinners rather than the nut that came with

the engine.

Join the Wings

❏ 1. Slide the two aluminum tubes into one of the

wing halves. Slide the other wing onto the tubes.

Push the wings tightly together.

- 14 -

Page 15

❏ 2. Inser t the 1/4-20 thumbscrew into the opening

in the right wing panel.Tighten the screw, pulling the

wings together.

❏ 3. Place the fuselage upside down into the foam

stand. Install the wing onto the fuselage, securing it

with two 1/4-20 nylon wing bolts.

❏ 4. Locate the two fiberglass wing fairings. Place

them on each wing. Trace the outline of the fairing

onto the wing.Using a sharp modeling knife, carefully

cut the covering from the wing. Be careful to only cut

through the covering, not the surface of the wing.

❏ 5. Glue the fairings to the wing. After the glue has

cured, remove the wing from the fuselage and

separate the two halves of the wing.

ASSEMBLE THE FUSELAGE

Install the Elevator and Rudder

❏ 1. Locate the rudder control wire and the r udder

control horn.Note that the wire has a flat spot pre-cut

in the end of the wire.

❏ 2. Slip the rudder control wire into the hole in the

top of the fuselage.

❏ 3. Put a 4-40 nut onto a 4-40 x 36" [914mm] wire

pushrod.Screw the wire pushrod into the nylon swiv el

connector approximately 20 turns. Lock the nut

against the connector.From the back of the fuselage,

slide the pushrod wire into the center plastic guide

tube that is pre-installed in the fuselage. Slide the

rudder control wire through the nylon bearing. Place

the rudder control horn onto the rudder control wire.

When installing it over the wire be sure the control

arm is on the left side of the fuselage.Remove the set

screw from the control horn and apply a couple of

drops of thread locker to the threads. Re-insert the

screw into the control horn, tightening the set screw

against the flat spot on the rudder control wire.

- 15 -

Page 16

- 16 -

❏ 4. Insert the elev ator joiner wire into the holes in the

sides of the fuselage following the sequence shown.

❏ 5. Slide the aluminum stabilizer tubes into the

back of the fuselage.Test fit the two stabilizer halves

onto the tubes. Be sure the stabilizer fits snug to the

sides of the fuselage.Once you are satisfied with the

fit, remove the stabilizers from the tubes.

❏ 6. WIth 200-grit sandpaper, roughen the fuselage

where the stabilizers make contact with the fuselage.

Glue the stabilizer halves to the fuselage with epoxy.

Tape the stabilizers in place until the glue has hardened.

❏ 7. Cut six 1" x 1" [25mm x 25mm] hinges from the

CA hinge strip. Snip off the corners so they go in

easier. Install three hinges into each of the elevator

halves and trial fit the elevators to the stab. Once

satisfied with the fit, remove the elevators from the

stab. Apply a small amount of epoxy to the elevator

joiner wires.With the hinges installed in the elevator,

slide the elevators onto the joiner wire and into the

hinge slots, securing the hinges to the stabilizer with

thin CA the same way you did the ailerons.

❏ 8. Cut three 1" x 1" [25mm x 25mm] hinges from the

CA hinge strip.Snip off the corners so they go in easier.

❏ 9. Insert the hinges into the hinge slots of the

vertical fin. Keep the hinges centered using a pin.

Page 17

❏ 10. Trial fit the rudder onto the hinges and the

vertical fin. Once satisfied with the fit, remove the

rudder. Apply a small amount of epoxy to the rudder

wire.With the hinges installed in the rudder, slide the

rudder in position.Secure the hinges with thin CA the

same way as was done for the elevator.

Install the Cockpit

The cockpit needs to be installed now, before the

installation of the servos.Do not skip this step thinking

you will install the cockpit after the rest of the plane is

complete. The cockpit can be installed permanently

but if you’re like most modelers you may lik e the ability

to remove it at a future date.The following instructions

will allow the cockpit to be removed should there ever

be a need to do so.

❏ 1. Locate the components of the cockpit interior.

Cut the instrument panel decal from the decal sheet

and install it to the instrument panel bulkhead. Glue

the four seat backs, the instrument panel and the

back of the cockpit in place.Glue pilot in place.

❏ 2. Located inside of the fuselage, on both sides of

the fuselage, are wood tabs.These are to be used to

help locate the cockpit floor. Position the cockpit just

above these blocks.

❏ 3. Install the cockpit into position with a hot melt

glue gun.This glue sets quickly yet is easily removab le

should you ever need to remove the cockpit.If you do

not have a hot melt glue gun you can also use silicone

though this will take longer to set up.

- 17 -

Page 18

Install Radio, Elevator & Rudder Servos

❏ 1. Plug the wire from the landing light located in the

nose of the fuselage into the wiring harness inside

the fuselage.

❏ 2.If you plan to install retractable landing gear you

need to install the air tank now .Glue the tank into the

opening on the right side of the fuselage. Hot melt

glue or epoxy mixed with microballoons works well.

❏ 3. Glue the two 3/16" x 3/8" x 9" [4mm x 10mm x

230mm] hardwood servo tray mounting rails inside

the fuselage.The mounting rails must be located on

the top of the balsa rails already glued to the

fuselage sides and spaced as shown in the photo.

❏ 4. Test fit the radio and servo tray to the rails you

glued into the fuselage. Note that the trays fit between

the balsa longerons on the fuselage sides. Once you

are satisfied with the fit of the trays, drill a 1/16" [1.6mm]

hole through the servo and radio trays, drilling through

the servo mounting rails. Secure both trays to the rails

with eight #2 x 3/8" [10mm] sheet metal screws and #2

flat washers.

❏ 5. Install a 4-40 nut, 4-40 threaded clevis and

silicone clevis keeper onto the threaded end of a 4-40

x 36" [914mm] wire pushrod. From the back of the

fuselage slide the elevator wire into the pre-installed

plastic pushrod tube for the elevator. Attach the clevis

to the elevator control horn.

❏ 6. Using the hardware provided with the servos,

install the elevator servo into the servo tra y as sho wn.

Center the elevator servo. Align the elevator pushrod

wire with the servo arm.To get a good alignment with

the servo arm, adjust the pushrod wire by making

slight bends as needed to the wire. Install a 4-40

solder clevis onto the servo arm. Center the elevator

and then mark the pushrod wire and cut it to length.

Remove the clevis from the ser vo arm.

❏ 7. Solder the clevis to the wire. Slide a clevis

keeper over the clevis. Then, attach the clevis to the

servo arm.

❏ 8. Install the rudder servo following the same

procedure used with the elevator servo. For the

rudder use a double servo arm and install the clevis

one hole in from the outermost hole as shown.

- 18 -

Page 19

❏ 9. Place 1/4" [6mm] foam under the receiver and

battery .Hold them to the tray with the plastic tie wraps.

Route the receiver antenna through the antenna tube,

securing the antenna at the back of the fuselage.

Note:If you are going to be utilizing the lighting system

on this airplane, you should hold off on installing the

receiver battery until you are instructed to install the

battery for the lights.The same plastic tie wraps used

for the receiver battery will be used to hold the battery

for the lighting system in place.

❏ 10. Position the tail cover in place on the bottom of

the fuselage.Drill a 1/16" [1.6mm] hole in each corner

of the cover. Remove the cover and drill a 3/32"

[2.4mm] hole through each of the holes you drilled in

the cover. Secure the cover to the fuselage with four

#2 x 3/8" [10mm] screws and #2 flat washers.

INSTALL THE LANDING GEAR

The following instructions are for the installation of the

fixed landing gear. If you will be installing the

retractable landing gear, skip ahead to the instruction

for the retractable landing gear .Should you later decide

to change over to the retractable landing gear, the

mounting holes match so the gear is interchangeable.

Nose Gear

❏

1. Locate the components for the nose gear

assembly. Assemble it as shown, making sure to use

thread locker on all of the bolts.

❏ 2. Place the nose gear assembly onto the

mounting rail in the fuselage. You will find that the

nose gear wire touches the fuselage. Mark the spot

where the wire makes contact and make a clearance

hole in the fuselage with a high speed motor tool.

❏ 3. Place the nose gear onto the mounting rails.

Mark the hole locations. Then, drill a 7/64" [2.8mm]

hole on each of the marks. Install the nose gear

assembly with four #6 x 1/2" [13mm] machine scre ws,

#6 flat washers and #6 lock washers.

- 19 -

Page 20

❏ 4. Cut the 39" [990mm] pull-pull wire in half. Slip a

crimp connector onto one of the wires. Wrap the wire

around each of the ball links on the nose gear steering.

Pull the wires tight and squeeze the crimp connector.

Insert the opposite end of the wire into the plastic tube.

❏ 5. Install a 2-56 nut and clevis onto two threaded

brass couplers.Install the clevis onto the outer holes of

the servo arm. Slide a crimp connector onto the wire.

Then, feed the wire through the hole in the side of the

brass coupler and back through the crimp connector.

Do this for both of the wires. Pull the wires, making

them equal in tension and making sure the rudder is

centered. Crimp the connectors against the wire.

❏ 6. Apply thread locker to two of the wheel collar set

screws. Insert the screws into two wheel collars.

Slide a wheel collar onto the nose gear wire,

tightening it against the inner most flat spot on the

nose gear wire. Install the nose wheel onto the axle

followed b y another wheel collar, tightening it against

the remaining flat spot on the wire.

Decision you must make…

Included in the kit is a fiberglass door that fits the

opening in the fuselage for the landing gear. If you

are planning to only fly this airplane with fixed

landing gear, then you might wish to proceed with

step 7. If you think you might be installing retracts at

some time in the future, you should skip step 7 and

move onto the main landing gear. The procedure

outlined in step 7 may be skipped with no effect on

the flying performance of the airplane.

❏ 7. You might wish to close off the nose gear

compartment to minimize drag to the aircraft. If so,

trim the door as shown and glue it permanently in

place on the fuselage.

Main Gear

Decision you must make…

Look closely at the bottom of the right wing. Adjacent

to the mounting rails for the landing gear you will find

the wheel opening for the retracts is covered with

Monokote. This covering can be left in place to

minimize drag. If you are interested in a more scale

like appearance, you might wish to permanently

mount the fiberglass gear doors as shown in the

following instructions. If there is a chance that you

might install retracts in the future, it is recommended

that you leave the covering in place and not install

the gear doors.If you choose to leave the co vering in

place skip ahead to step 3.

❏❏1. Cut the covering from the wheel wells. From

the 1/8" x 3/16" x 15-1/2" [3mm x 5mm x 390mm]

white balsa stick, cut four 3" [76mm] sticks. Glue two

into each wheel well to support the door when it is

glued in place. Position the sticks 1/8" [3mm] above

the bottom skin of the wing.

- 20 -

Page 21

❏❏2. Glue the gear door to the sticks.

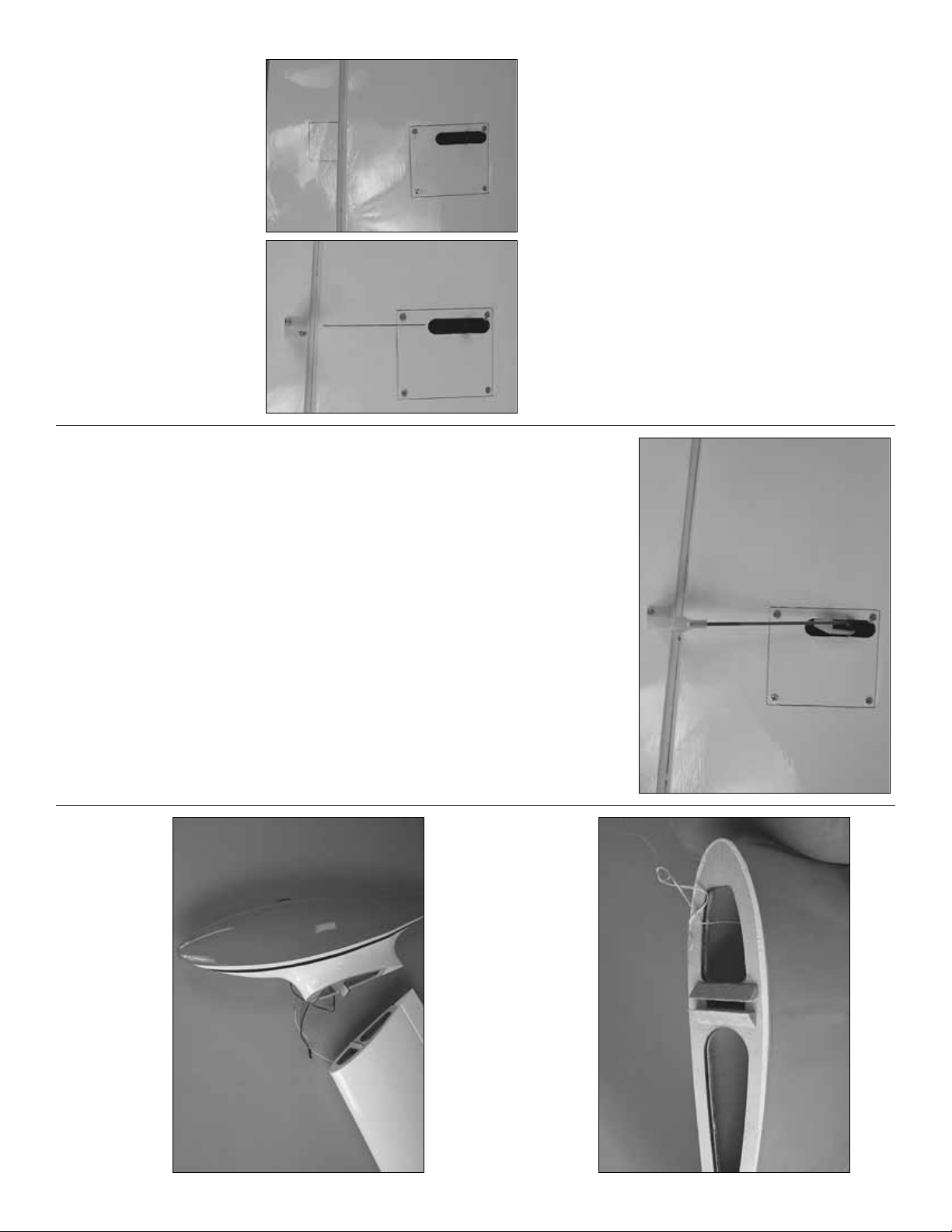

❏❏3. Install the

landing gear into the

landing gear mounting

block.Secure the gear

to the blocks with two

nylon landing gear

straps and four #4 x

1/2" [3mm x 13mm]

sheet metal screws.

❏❏4. Position the landing gear over the hardwood

rails. Be sure the axle is pointed towards the root rib

of the wing. Drill four 7/64" [2.8mm] holes through the

mounting holes and into the hardwood rails.Use four

#6 x 1/2" [13mm] sheet metal screws, #6 lock

washers and #6 flat washers to hold the gear in place.

❏❏5.Position two nylon humped landing gear straps

onto the landing gear wire and position the landing

gear door over the landing gear wire.Mark the location

of the holes for the landing gear straps onto the door.

On the marks, drill a 5/64" [2mm] hole through the

door. Secure the door to the landing gear straps with

four 2mm x 10mm machine screws and 2mm nuts.

When positioning the landing gear doors note that the

bottom of the door extends beyond the axle.

❏❏6. Drill a 3/32" [2.4mm] hole in each of the

corners of the landing gear plate as shown.

❏❏7. Place the landing gear plate in position over

the landing gear block. Drill a 1/16" [1.6mm] hole

through each of the four holes, drilling through the

hardwood plate. Mount the plate with four #2 x 3/8"

[9.5mm] sheet metal screws.

❏❏8.Install a set screw into two 3/16" [5mm] wheel

collars. Slide a wheel collar onto the axle followed by

the wheel and another wheel collar. Tighten the set

screw against the flat spots on the axle.

❏ 9.Repeat steps 1–8 for the opposite landing gear.

Skip ahead to Final Assembly.

- 21 -

Page 22

RETRACTABLE LANDING GEAR

The following instructions will take you through the

installation of the retractable landing gear.To maximize

the scale appearance of the airplane we have included

landing gear doors for the nose gear and the main gear .

These doors are intended for use with the installation of

the fixed landing gear. Though we are not providing

instructions for their use on retractable landing gear , the

more “scale-minded” pilot might wish to use them and

create their own door hinging and closure mechanisms.

Nose Gear

❏ 1. Drill two 1/8" [3mm] holes in the corner of the

nose gear wheel well for the air lines.

❏ 2. Install 18" [460mm] of air line onto each air inlet

on the landing gear.Feed each line into the holes you

drilled, pulling the lines into the radio compartment.

Place the nose gear onto the mounting rails.Mark the

hole locations and then drill a 7/64" [2.8mm] hole on

each of the marks. Install the nose gear assembly

with four #6 x 1/2" [13mm] machine screws, #6 flat

washers and #6 lock washers.

❏ 3.Install the nose wheel.Use two #8 flat washers on

each side of the wheel to keep it centered in the fork.

❏ 4. Cut the 39" [990mm] pull-pull wire in half. Slip a

crimp connector onto one of the wires.Wrap the wire

around each of the ball links on the nose gear

steering. Pull the wires tight and squeeze the crimp

connector.Insert the opposite end of the wire into the

plastic tube.

❏ 5. Install a 2-56 nut and clevis onto two threaded

brass couplers.Install the clevis onto the outer holes

of the servo arm. Slide a crimp connector onto the

wire.Then, feed the wire through the hole in the side

of the brass coupler and back through the crimp

connector. Do this for both of the wires. Pull the

wires, making them equal in tension and making

sure the rudder is centered. Crimp the connectors

against the wire.

- 22 -

Page 23

Main Gear

❏❏1. Cut two airlines to a length of 24" [610mm].

They need to be fed from the wheel well to the center

of the wing where they will be pulled through the

wing with the string that was left in place during the

servo installation. The lines can be fed through the

openings for the servo leads as shown in the photos.

Once the line is installed between the wheel well and

the wing, tie the string to the two airlines and pull

them through the hole at the root of the wing.

❏❏2. Attach the airlines to the air inlets on the

landing gear.Place the landing gear onto the landing

gear rails. (

Note: When installing the landing gear,

the torque link assembly will be towards the back of

the wing.

) Drill a 7/64" [2.8mm] hole through the

landing gear plate for each of the mounting holes.

Insert and then remove a #6 x 1/2" [13mm] screw

into each hole.Apply a small amount of thin CA onto

the threads to harden them. After the glue has

hardened, mount the landing gear with a #6 x 1/2"

[13mm] screw, #6 flat washer and #6 lock washer.

❏❏3. Cut away the wood as shown.

❏❏4. Loosen the set screw for the landing gear.

Remove the landing gear leg.Then, slide one of the

landing gear door cover mounting brackets onto the

leg. Reinstall the leg and tighten the set screw.

❏❏5. Retract the landing gear.Then, position the

landing gear door so it is centered in the opening as

shown. Make a line on the door in line with the hole

in the landing gear.

- 23 -

Page 24

❏❏6. Place a piece of masking tape onto the

mounting flange. Make a line on the masking tape in

line with the hole in the landing gear.

❏❏7. Position the landing gear door in the opening

in the bottom of the wing.When you are satisfied with

the position of the door, draw a line across the line

already drawn on the landing gear door.

❏❏8.At the intersection of the two lines drill a 1/16"

[1.6mm] pilot hole. Then drill through the pilot hole

with a 11/64" [4.4mm] drill.

❏❏9. Glue two #8 flat washers to the inside of the

landing gear door.

❏❏10. Locate a #8 x 1" [25mm] phillips head

machine screw. Use a high speed motor tool or

hacksaw and cut the bolt so the threaded length of

the bolt is 5/16" [7.9mm].

❏❏11. Locate the 4-40 x 12" [305mm] threaded

rod. File a point onto one end of the rod. Cut the

pointed end from the rod to a length of 1/4" [6mm].

❏❏12.Position the landing gear door cover mounting

bracket so that it is appro ximately 1/16" [1.6mm] abov e

the torque link assembly. Install the pointed rod into the

hole in the bracket as shown.Be sure the flat portion of

the bracket is aligned with the surface of the wing and

then tighten the threaded rod against the landing gear.

❏❏13. Place the landing gear door in position over

the wheel well. Install the 8-32 bolt that you cut

through the hole in the gear door, tightening it to the

landing gear. Adjust the door as needed to make

sure it is properly centered in the wheel well. Once

you are satisfied with the position, press firmly on the

landing gear door where the pointed rod is making

contact with the door.Press firmly enough to make a

small mark on the inside of the door.

- 24 -

Page 25

❏❏14.Remove the gear door from the landing gear.

On the mark you made drill a 1/16" [1.6mm] pilot hole

through the mark. Drill though the pilot hole with a

7/64" drill bit.

❏❏15. Reinstall the landing gear door onto the

landing gear with the 8-32 bolt. Using a 4-40 x 1/4"

[13mm] socket head cap screw and a #4 washer,

secure the bottom of the door to the landing gear

door cover mounting bracket. Be sure to use thread

locker on both mounting screws.

❏❏16. Position the landing gear flange plate over

the landing gear mounting plate.Drill a 1/16" [1.6mm]

hole in each corner of the plate. Remove the flange

plate from the wing and drill a 3-32" [2.4mm] hole

through each of the holes you drilled in the flange

plate.Secure the flange plate to the wing with four #2

x 3/8" [10mm] screws and #2 flat washers.

❏ 17. Repeat steps 1-16 for the other landing gear.

Install the Retract Hardware

❏ 1.Glue the plywood air control valve plate to the

servo tray and glue the two plywood triangle shaped

gussets as shown.

❏ 2. Install a ball link ball to the control valve with a

.080 nut. Be sure to use a small amount of thread

locker when securing the nut. Insert the air control

valve into the plate.Secure the valve to the plate with

the nut.Be sure to use a small amount of thread locker

when securing the nut.

❏ 3. Install the retract servo into the servo opening

in the tray. Secure it the same way you did the other

servos. Install a nylon ball link onto the 2-56 x 6"

[152mm] threaded rod approximately 15 turns.Then

install the nylon ball link onto the ball. Center the air

control valve arm and center the servo.With a fine tip

marker, mark the wire where it aligns with the outer

hole of the servo arm. Make a 90 degree bend on the

mark. Cut the wire so the wire is 3/8" [10mm] in

length after the bend. Inser t the wire into the servo

arm and lock it in place with a nylon Faslink.

- 25 -

Page 26

❏ 4. Decide on a location to mount the air fill valve.

We mounted ours on the bottom of the fuselage just

behind the trailing edge of the wing. This keeps the

valve somewhat hidden but it is not the most easily

accessible location.If you do not mind it being visible

you may wish to locate in on the fuselage in a place

more convenient for filling the air tank.

❏ 5. Install the air lines to the air tank, fill valve and

air control valve as shown in the instructions that

came with the air control kit. Install the connectors

that will connect the airlines from the main gear to

the airlines in the fuselage.

❏ 6. You now have to make a couple of decisions

regarding the wing.The wing is designed in two pieces

for easier transportation and storage. Those of you

that have an appropriately sized v ehicle and adequate

storage area may wish to leav e the wing assemb led in

one piece.If you will be leaving the wing together, join

the two air lines that will retract the landing gear with

a “T” fitting. Join the remaining two lines with another

“T” fitting. Install a 12" [310mm] length of air line onto

the “T” fitting and an air line quick connector on the

other end. If you will be taking your wings apart,

substitute a pair of quick connectors for the “T”fittings.

FINAL ASSEMBLY

Completing the Radio Installation

❏ 1. Connect the elevator and rudder servos to the

receiver. If you have installed retracts, connect the

retract servo to the receiver too.

❏ 2. You have a few options when connecting the

aileron, flap and throttle servos. Depending on the

number of channels you hav e available on your radio

system, you may wish to have each servo lead plug

into its own receiver slot. If you choose to do this

follow the instructions included with your radio

system. The option of using a “Y” connector is

probably the simplest method.Install a “Y” connector

between the two aileron connections coming out of

each wing and one between the flap connections in

each wing.If you intend to leave y our wings together,

secure the connectors together with heat shrink

tubing, tape or some other method. If you want the

ability to separate the two wings, secure the

connectors on one wing only.

❏ 3. For the throttle linkage you can use “Y”

connectors the same way done for the ailerons and

flaps. Again, if your radio has the ability to plug each

throttle servo into its own slot, you might want to

consider doing this. Even if you chose to use “Y”

connectors on the ailerons and flaps, you might want

to have the throttles on separate channels and mix

them with the radio.This would give you the option of

starting and operating each engine independently of

each other during the start up of the engines.

❏ 4. Install a 6" [152mm] ser vo extension into the

slots in your receiver for each of the aileron, flap and

throttle servo leads. This will make plugging the

connections in the wing to the receiver easier.

❏ 5. Install the radio switch and charge jack for your

particular brand of radio and plug it into the receiver.

We chose to mount ours on the bottom of the

fuselage. For easier access you might want to

consider mounting it to the side of the fuselage.

Connect the Lighting System

The lighting system is a nice scale option but is not

required in order to fly the airplane. If you choose not

to use the lights you can skip this section of the

manual.

Do not operate the lighting system from

the receiver battery pack!

The lighting system will

require the use of a separate 500 mAh battery pack

and a switch harness for installation.

- 26 -

Page 27

❏ 1. You may wish to balance your airplane before

deciding on the final location of the battery for the lighting

system, but most likely the battery placement will not be

crucial for purposes of balancing the airplane.Mount the

battery for the lighting system on the opposite side of the

battery/receiver tray from the battery for the radio

system. Use the plastic tie wraps to hold them in place.

❏ 2. Install a switch and charge jack on the fuselage

the same way done for the receiver.

❏ 3. Be sure the main landing light from the front of

the fuselage is plugged into the pre-installed lighting

harness. Plug the wires from the switch into the

wiring harness and the batter y pack.

❏ 4. Once everything in the fuselage is connected

properly, use tie wraps or tape to bundle the excess

wire together to help clean up the entire installation.

When doing this be sure that you leave the male

connector for the lights in the wing accessible.

❏ 5.Install a “Y”harness to the wires from the left and

right wing tip light. When you assemble the airplane

for flight, plug the lights from the wing into the

connector on the lighting harness.

Apply the Decals

1. Use scissors or a sharp hobby knife to cut the

decals from the sheet.

2. Be certain the model is clean and free from oily

fingerprints and dust. Prepare a dishpan or small

bucket with a mixture of liquid dish soap and warm

water–about one teaspoon of soap per gallon of water .

Submerse the decal in the soap and water and peel off

the paper backing.Note: Even though the decals have

a “sticky-back” and are not the water transfer type,

submersing them in soap and water allows accurate

positioning and reduces air bubbles underneath.

3. Position the decal on the model where desired.

Holding the decal down, use a paper towel to wipe

most of the water away.

4. Use a piece of soft balsa or something similar to

squeegee remaining water from under the decal.

Apply the rest of the decals the same way.

GET THE MODEL READY TO FLY

Check the Control Directions

❏ 1.Turn on the transmitter and receiver and center

the trims. If necessary, remove the servo arms from

the servos and reposition them so they are centered.

Reinstall the screws that hold on the servo arms.

❏ 2. With the transmitter and receiver still on, check

all the control surfaces to see if they are centered.If

necessary, adjust the clevises on the pushrods to

center the control surfaces.

❏ 3. Make cer tain that the control surfaces and the

carburetor respond in the correct direction as shown

in the diagram. If any of the controls respond in the

wrong direction, use the servo reversing in the

transmitter to reverse the servos connected to those

controls. Be certain the control surfaces have

remained centered. Adjust if necessar y.

- 27 -

Page 28

Set the Control Throws

Use a Great Planes AccuThrow

™

(or a ruler) to

accurately measure and set the control throw of each

control surface as indicated in the chart that follows.If

your radio does not have dual rates, we recommend

setting the throws at the high rate setting. NOTE: The

throws are measured at the widest part of the

elevators, rudder and ailerons.

Balance the Model (C.G.)

At this stage the model should be in ready-to-fly

condition with all of the systems in place including

the engines, landing gear and the radio system.

❏ 1. Use a felt-tip pen or 1/8" [3mm]-wide tape to

accurately mark the C.G. on the top of the wing on

both sides of the fuselage.The C.G. is located 3-7/16"

[87mm] back from the leading edge of the wing at the

fuselage sides.

❏ 2.With the wing attached to the fuselage, all parts

of the model installed (ready to fly) and an empty fuel

tank, place the model upsidedown on a Great Planes

CG Machine

™

, or lift it upside down at the balance

point you marked.

❏ 3.If the tail drops, the model is “tail heavy”and the

battery pack and/or receiver must be shifted forward

or weight must be added to the nose to balance.If the

nose drops, the model is “nose heavy”and the battery

pack and/or receiver must be shifted aft or weight

must be added to the tail to balance. If possible,

relocate the battery pack or eliminate any additional

ballast required. Use Great Planes (GPMQ4485)

“stick on” lead. A good place to add stick-on nose

weight is in the nose of the fuselage.Begin by placing

incrementally increasing amounts of weight on the

inside of the fuse until the model balances. Once you

have determined the amount of weight required, it

can be permanently attached. If required, tail weight

may be added inside the rear of the fuselage.

❏ 4. IMPORTANT: If you found it necessary to add

any weight, recheck the C.G. after the weight has

been installed.

Balance the Model Laterally

❏ 1. With the wing level, have an assistant help you

lift the model at the tip of the nose and the tail. Do

this several times.

❏ 2.If one wing always drops when you lift the model,

it means that side is heavy. Balance the airplane by

adding weight to the other wing tip.An airplane that

has been laterally balanced will track better in

loops and other maneuvers.

This is where your model should balance for the first

flights.Later, you may wish to experiment by shifting

the C.G. up to 5/16" [8mm] forward or 5/16" [8mm]

back to change the flying characteristics.Moving the

C.G. forward may improve the smoothness and

stability, but the model may then require more speed

for takeoff and make it more difficult to slow for

landing. Moving the C.G. aft makes the model more

maneuverable , but could also cause it to become too

difficult to control. In any case, start at the

recommended balance point and do not at any

time balance the model outside the specified range.

More than any other factor, the C.G. (balance

point) can have the greatesteffect on how a model

flies, and may determine whether or not your first

flight will be successful.If you value this model and

wish to enjoy it for many flights, DO NOT

OVERLOOK THIS IMPORTANT PROCEDURE. A

model that is not properly balanced will be

unstable and possibly unflyable.

IMPORTANT:The Cessna 310 has been extensively

flown and tested to arrive at the throws at which it flies

best. Flying your model at these throws will provide

you with the greatest chance for successful first flights .

If, after you have become accustomed to the way the

Cessna 310 flies, you would like to change the thro ws

to suit your taste, that is fine. However, too much

control throw could make the model difficult to control,

so remember, “more is not always better.”

These are the recommended control surface throws:

High Rate Low Rate

ELEVATOR 1" up 3/4" up

1" down 3/4" down

[25mm] [19mm]

RUDDER 1-1/2" right 1" right

1-1/2" left 1" left

[38mm] [25mm]

AILERONS: 3/4" up 1/2" up

3/4" down 1/2" down

[19mm] [19mm]

FLAPS: 1-5/8" [40mm] down

- 28 -

3-7/16" [87mm]

Page 29

Adjusting the Retractable Landing Gear

After connecting the air lines as instructed in the

instructions that came with the Air Control kit, fill the

air tank to 100psi and try cycling the landing gear.

The landing gear should cycle up and down freely. If

they do not, here are some troubleshooting tips:

❏ 1. The gear does not move up or down: Check to

be sure the control screws on the variable rate valve

are open.

❏ 2. The landing gear moves up and down but is

not smooth:When mounting the landing gear onto the

landing gear rails it is important that the rails are

exactly parallel to one another. If not, when you tighten

the screws the mounting flange of the gear mechanism