Page 1

SILENT

HUNTER

CONTENTS

WAR BENEATH THE WAVES . . . . . . . . . . . 1

What Comes with This Game . . . . . . . . . . 1

Using the Mouse . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

STARTING THE GAME . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

Single Missions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Mission Customization . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

Realism . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Submarine Class Selection . . . . . . . . . . . 10

Victory or Defeat . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

THE CAREER MENU . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

Starting a Career . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

Best Careers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

Main Menu . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

Continue a Career . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

Base Menu Options . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

CONTROLS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

The Smart Mouse Pointer . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Using the Function Keys (F1 - F10) . . . . . 14

Setting the Detail Level . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Control Buttons . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

COMMANDING THE SUBMARINE . . . . . . 16

Captain’s Cabin . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Charts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Radar . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

TDC (Torpedo Data Computer) . . . . . . . . 22

Gauges Station . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

Up Scope (or Periscope Station) . . . . . . . 27

Bridge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

Status and Torpedo Room Stations . . . . . 38

SUBMARINES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

S

ILENTHUNTER

U.S. Torpedoes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50

Radar and Bathythermograph . . . . . . . . . 50

Deck Guns/AA Guns . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50

TORPEDOES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50

Shortages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50

Torpedo Types . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

Problems Arise . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52

The New Hope . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53

THE COMMANDERS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54

Vice Admiral Charles Lockwood . . . . . . . 54

Dudley W. “Mush” Morton

and the Wahoo . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55

Lawson P. “Red” Ramage

and the Parche . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55

Richard H. O’Kane and the Tang . . . . . . . 56

APPENDIX A:

U.S.S. SKATE AND THE FIFTH FLEET . . 57

On to the Gilberts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61

Operations Flintlock and Hailstone . . . . 64

APPENDIX B:

TACTICS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68

Torpedo Attack . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68

Basic Approach Objective . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68

APPENDIX C:

THE FIRE CONTROL PROBLEM . . . . . . . 73

WEAPONS DATA . . . . . . . 50

This product has been rated by the Entertainment Software Rating Board. For information about the ESRB rating, or to comment about the appropriateness of the

rating, please contact the ESRB at 1-800-771-3772.

Page 2

SILENT

HUNTER

1 WAR BETWEEN THE WAVES

WAR BENEATH THE WAVES

The December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor damaged or destroyed nineteen

capital ships of the U.S. Navy’s Pacific Fleet. This left the aged and outgunned

forces of the Asiatic Fleet as the first line of defense against the oncoming might of

the Japanese Navy. One force that emerged from the attacks on Pearl Harbor and

Cavite, virtually unscathed and ready to carry the war to the enemy, were the submariners of the Fleet Scouting Force. The 51 submarines of the Asiatic and Pacific

fleets were ordered to “...

J

APAN

. Y

OU WILL SINK OR DESTROY ENEMY SHIPPING WHEREVER ENCOUNTERED

Authorized to sink any vessel bearing the “Rising Sun” of Japan, the untried

men of the Pacific submarine forces quickly became hunters of the largest

prey around. Now, you too can stalk the tankers and freighters that carry the

lifeblood of the empire, the destroyers, cruisers and carriers that are the

weapons of war. You can become a Silent Hunter.

EXECUTE UNRESTRICTED AIR AND SUBMARINE WARFARE AGAINST

.”

SILENT

HUNTER

2 WAR BETWEEN THE WAVES: What Comes with this Game

by William P. “Bud” Gruner, who commanded SS 305, the U.S.S. Skateon her

third, fourth and fifth war patrols. Appendix A is entitled “The U.S.S. Skate and

the Fifth Fleet.” Appendix B provides a brief overview of submarine tactics.

Appendix C describes the formulas for calculating a manual firing solution.

Using the Mouse

In this manual, the term “click” means to move the mouse pointer over the

desired area of the screen and press either the left or right mouse button.

The mouse pointer changes shape depending on the type of action which can

be taken. “Left-click” or “right-click” means to move the mouse pointer to

the desired position and press the appropriate button.

Left-clicking is used to change stations aboard the submarine, set controls,

fire weapons, and alter preferences. Left-clicking handles most of the controls in S

the current mission can be ended.

ILENTHUNTER

. Right-clicking opens the Abort Mission box where

What Comes with This Game

The game box should contain this user’s manual, a S

a data card. This user’s manual explains game controls and contains historical

information about submarine warfare in the Pacific Theater during World War II.

To install the game, please refer to the data card.

This manual contains a description of how to use all of the controls that this

simulation provides to realistically reproduce the feeling of hunting and being

hunted by the ships of the Imperial Japanese Navy. It also contains several

appendices which provide more insights into the reality of submarine warfare

ILENTHUNTER

CD-ROM, and

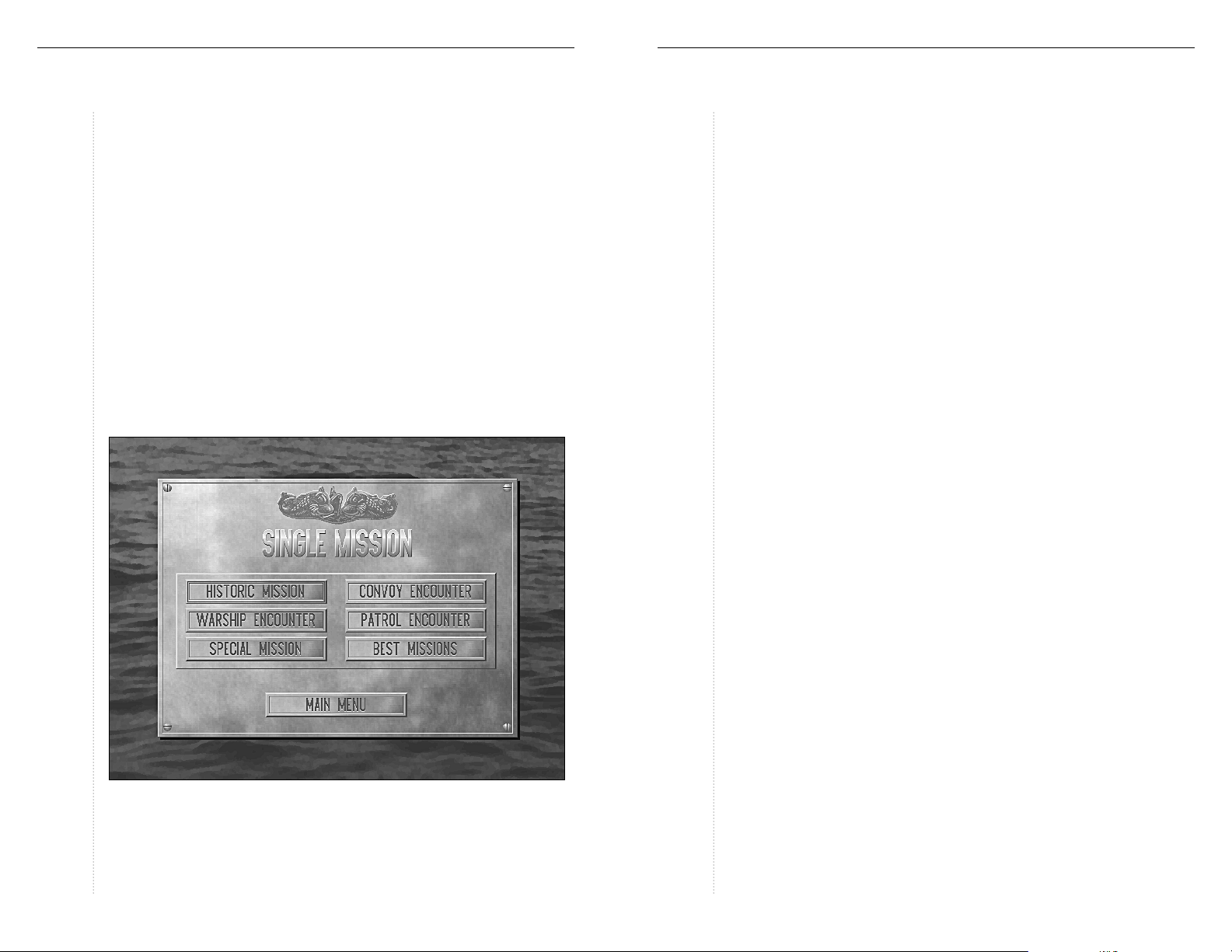

STARTING THE GAME

After the opening animation, two choices are offered for playing S

a Single Missionor the Career Menu. In addition, there are options to view an

interview with William P. “Bud” Gruner, who commanded the U.S.S. Skate;

take a multimedia tour of the U.S.S. Pampanito ; or Exit to DOS.

ILENTHUNTER

,

Page 3

SILENT

HUNTER

3 STARTING THE GAME: Single Mission

SILENT

HUNTER

4 STARTING THE GAME: Single Mission

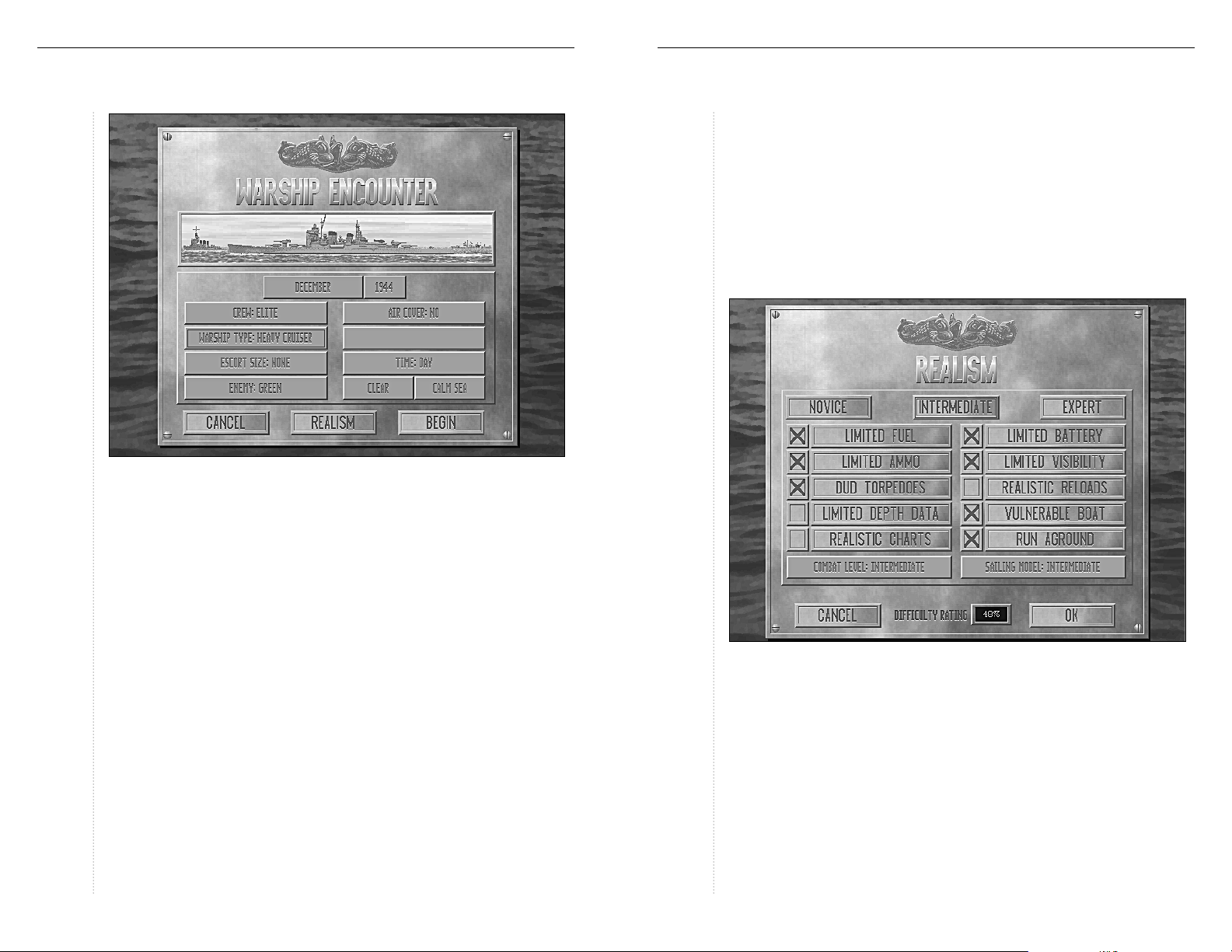

Single Missions

Choosing Single Mission presents an option to perform one of five different

kinds of authentic missions that U.S. submarines undertook during WWII.

In addition to seeking out and destroying enemy warships and cargo ships,

U.S. submarines performed other valuable services such as rescuing

downed pilots. All of the types of missions except for the Historic Mission

selection are generated randomly, and can be customized prior to play.

These missions will begin with some form of contact notification regarding

the enemy, either a radar contact, a hydrophone bearing, or a lookout

report. The mission ends when the submarine is out of contact with all

enemy ships. This might be because the submarine has sunk all the enemy

ships, has disengaged or been outrun by the enemy, or has been destroyed.

At this point a scoring screen appears which correlates the level of realism

and the number of enemy vessels damaged or sunk and presents the score.

Left-clicking on the Exit button returns you to the Single Mission menu.

The Historical Mission menu automatically defaults to the top mission on

the menu, so go ahead and make any realism changes prior to selecting the

mission to be played.

Convoy Encounter

During WWII U.S. submarines sank nearly 5,000,000 tons of Japanese merchant shipping, accounting for over 1100 confirmed sinkings. This was the

most likely type of encounter during the war.

Warship Encounter

This mission consists of intercepting and attacking an Imperial Japanese

Navy task force. Aircraft carriers were the highest priority target for the

submarine force, followed by battleships and escort carriers.

Patrol Encounter

Encounter a Japanese anti-submarine (ASW) patrol searching for U.S. submarines.

Lifeguard Duty

Over 500 aviators owe their lives to the men of the Silent Service. Submarines

were frequently positioned to recover downed pilots at the scene of surface

engagements, such as Midway, or during large air strikes. A downed aviator

can only survive a limited time in the water, and the submarine’s task is to

effect a rescue before the sea claims him or the enemy captures him.

Historic Mission

This option presents the opportunity to test your skills against those of historic submariners in encounters that defined what it meant to be a member

of the Silent Service. The available missions are listed in the menu, with

the appropriate briefing listed below the mission menu.

Mission Customization

After a mission type has been selected, several mission variables may be

chosen. Each type of mission has some of the following options available.

Date

The date affects the location of the encounter, the number and type of ships

encountered, and the equipment available to both sides. For more information regarding the types of equipment available for any given month of the

war, see the “S

Crew Quality

Crew quality affects the ability of the crew to operate the submarine. Reload

time, dive time, lookout sighting distances, and other factors are all determined by the crew quality setting. The crew can range from green to elite.

ILENTHUNTER

Weapons Data” table on page 50.

Page 4

SILENT

HUNTER

5 STARTING THE GAME: Mission Customization

Convoy Size

The size of the encountered convoy, small, medium, or large.

SILENT

HUNTER

6 STARTING THE GAME: Mission Customization

Time of Day

Select whether to begin the mission at Dawn, during the Daytime, at Dusk

or during the Night. Submarines equipped with radar could operate on the

surface at night much more readily than could earlier submarines.

Weather

The weather affects the speed of ships and the amount of visibility. Heavy

seas affect the submarine’s stability near the surface, while fog can be a

commander’s best friend.

Warship Type

Capital ships travelled in a main body of vessels, usually with an interior

screen of cruisers and an exterior screen of destroyers. Select between carrier, battleship, cruiser, and light cruiser task forces.

Escort Size/Patrol Threat

These options determine the number and probability of encountering some

form of patrol vessel or escort.

Enemy Quality

This setting determines how tough the enemy is. Gun and depth charge

attack accuracy, lookout sighting distance, and overall coordination of attack

are controlled by this setting. Enemy crews can be green, veteran, or elite.

Air Cover/Threat

Task forces and occasionally convoys were supplied with air cover. Other missions run the risk of encountering an aerial patrol. These settings determine

the number and probability of encountering some form of air cover.

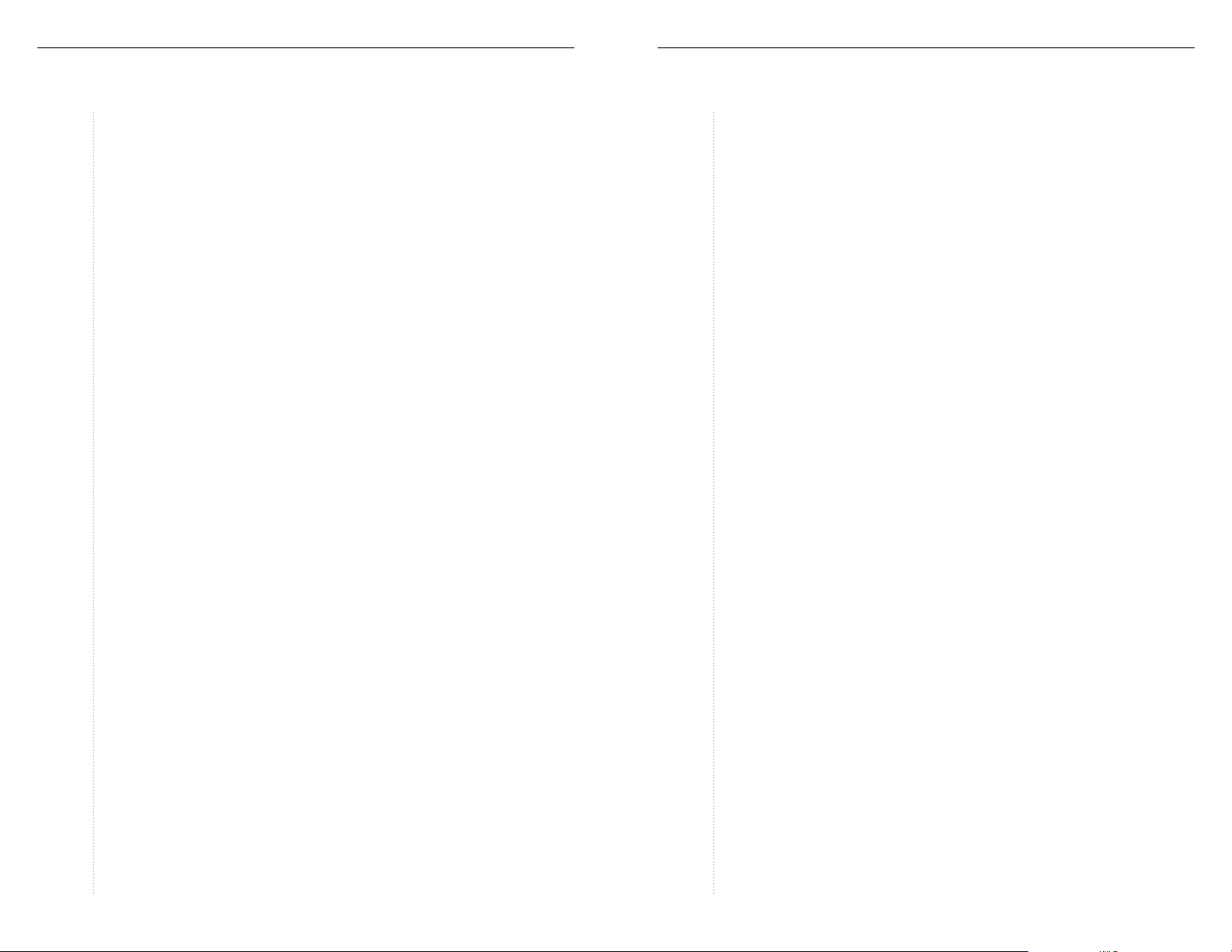

Realism

The level of realism experienced while playing S

fied for both single missions and careers. This is done using the Realism

screen, which is available from all Single Mission screens and when the

submarine is in port during campaign games. With all Realism settings

selected, the simulation is as close to real as is possible!

Overall settings

At the top of the Realism menu are three buttons: Novice, Intermediate, and

Expert. These buttons are quick ways to select specific sets of play conditions.

Novice level lowers the combat and sailing model levels to novice, and turns

off all realism settings except the vulnerability of the submarine.

ILENTHUNTER

can be modi-

Page 5

SILENT

HUNTER

7 STARTING THE GAME: Realism

SILENT

HUNTER

8 STARTING THE GAME: Realism

Intermediate level lowers the combat level and sailing models to “Intermediate,”

and turns off the Dud Torpedo, Realistic Reloads, Limited Depth Data, and

Realistic Charts settings.

Expert level implements every possible realism setting, duplicating live conditions during WWII as closely as possible. The combat level is set to

“Advanced” and the submarine maneuvers realistically.

Other Realism Settings

There are options other than the three preset levels. Ten settings can be

toggled on or off and each of these settings has the effect of reducing the

realism by a certain percentage when turned off. The Combat Level and

Sailing Model settings have more than two levels and each of these levels

also change the overall Difficulty Rating.

Limited Fuel

The Limited Fuel setting has a small effect on Single Mission games, but is

a serious consideration for the Campaign Game. Refueling can only be performed by a submarine tender or at a base. Turning this setting off reduces

the realism factor by 10%.

Limited Battery

With Limited Battery turned off, the submarine never needs to surface to recharge the batteries. Turning this setting off reduces the realism factor by 30%.

Limited Ammo

The submarines simulated by S

rounds for the deck gun and twelve to twenty-eight torpedoes. When

turned off, there is an unlimited supply of both types of munitions. Turning

this setting off reduces the realism factor by 50%.

ILENTHUNTER

normally carried one hundred

Limited Visibility

With this option on, only ships actually visible to the crew will appear on

the map screen at the Charts station. If the submarine is submerged with

the periscope lowered, only the most recent observed contact will be shown

on the map. With this setting off, all ships will be shown on the map.

Turning this setting off reduces the realism factor by 30%.

Dud Torpedoes

From the beginning of the war until late in 1943, a series of problems with

the torpedoes caused a significant number of them to fail. With this setting

off, torpedoes are always reliable, but realism drops by 15%. For more

details of the torpedo problems, see the “Torpedoes” section on page 50.

Realistic Reloads

The Realistic Reloads setting toggles the torpedo tube reload time between

two minutes and a more realistic time that is also affected by crew quality.

Turning this setting off reduces the realism factor by 10%.

Limited Depth Data

With Limited Depth Data toggled on, the Depth Gauge indicates only how

deep the submarine has gone. There is no information available other than

the chart about how deep the waters are in that particular part of the ocean.

When toggled off, an additional gauge appears at the Gauges station entitled

“Depth Under Keel.” This indicates how deep the local waters are. Turning

this setting off reduces the realism factor by 5%.

Vulnerable Boat

Toggling Vulnerable Boat off eliminates the chance of the submarine taking damage, and correspondingly, reduces the Realism level by 80%.

Realistic Charts

The Realistic Charts setting controls the information that can be viewed at

the Charts station. With this setting toggled on, the chart shows only the

position of ships relative to the submarine, further modified by the Limited

Visibility setting. With this setting off, the Charts station shows torpedo

wakes and shell splashes as well. Turning this setting off reduces the realism factor by 10%.

Run Aground

With this setting turned off, the submarine can run aground without sustaining damage. This setting alters the Difficulty Rating by 5%.

Combat Level

Changing the Combat Level setting affects the accuracy and lethality of

both side’s weapons. The amount of information displayed on the map at

the Charts station, such as torpedoes, sonar pings, and gun hits, also

decreases at the advanced levels. The Realism rating is reduced 15% for

each level below Expert; from Expert to Advanced, to Intermediate and

finally Novice.

Page 6

SILENT

HUNTER

9 STARTING THE GAME: Realism

SILENT

HUNTER

10 STARTING THE GAME: Submarine Class Selection

Sailing Model

The Sailing Model controls the maneuverability of the submarine, affecting

dive time, maximum speed in heavy seas, turn rate and the likelihood of the

submarine running aground. Realism drops by 10% for each reduction in

level; from Realistic to Intermediate and from Intermediate to Novice.

Difficulty Rating

The Difficulty Rating is based on the effects of changing the realism settings

above. The mission score for completed missions is modified by the level of

realism chosen. The higher the realism setting, the higher the potential score.

Realism and Japanese Anti-Submarine Warfare

The realism setting determines the effectiveness of Japanese anti-submarine warfare (ASW). Throughout most of WWII, the Japanese Navy believed

that no submarine could dive below 200 feet and survive, so most of their

ASW efforts were expended at depths between 50 and 150 feet. In deep

water, U.S. fleet submarines could dive routinely below 200 feet and so

were able to survive repeated depth charge attacks.

In S

ILENTHUNTER

beyond 100%. This reflects Japanese ASW efforts that take into account the

full capabilities of U.S. submarines.

, the Combat Level setting can be used to increase realism

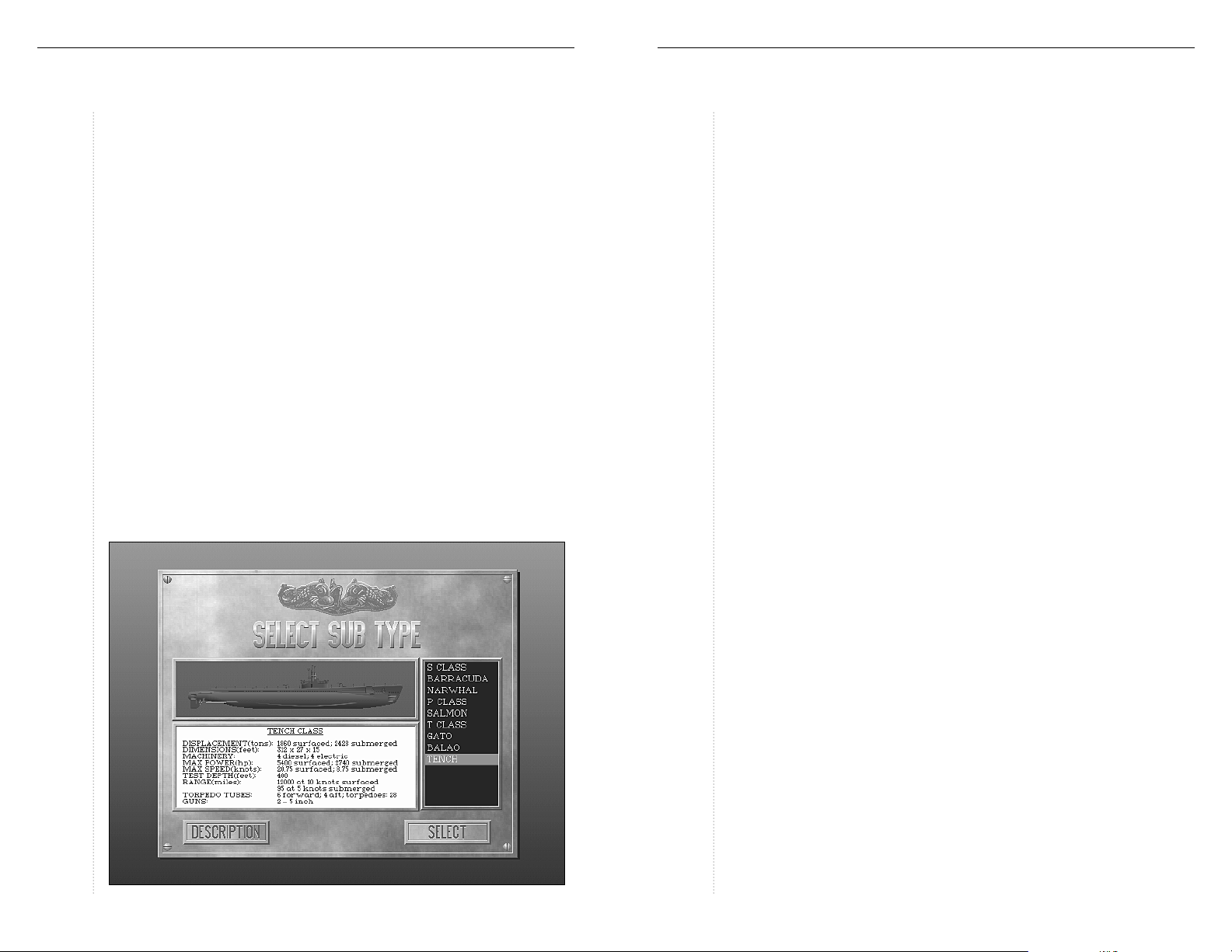

Submarine Class Selection

The type of submarine used can be selected for any of the single mission scenarios from a range of vessels available at that date. For Historic Missions, the

type of submarine used in the actual encounter is preselected. Each type of

submarine is displayed with statistical details by left-clicking on the list of

classes. Left-clicking on the Descriptionbutton toggles to a brief description.

Confirm the choice of a particular class by left-clicking on the Select button.

For more details about the submarine classes available in S

the “Submarines” section on page 40.

ILENTHUNTER

see

Victory or Defeat

The scenario continues until the submarine is destroyed or all enemy vessels

are beyond contact range. This can be because they have been sunk, they

have outrun the submarine, or the submarine has evaded all pursuit.

At this point a scoring screen appears which correlates the level or realism

and the number of enemy vessels damaged or sunk and presents the score.

Left-clicking on the Exit button returns you to the Single Mission menu.

THE CAREER MENU

The Career Menu is where the campaign game begins. Starting at any point

in the war, a series of war patrols are performed that can then be compared

to those of some of the greatest submariners ever.

Starting a Career

Enter the name of the submarine’s commander and select a starting month

and year for this career. Up to twenty different careers can be accommodated by the career roster; if all twenty positions have been used, a new

career must be entered over an older career.

The date chosen determines what classes of equipment are available to the

commander. This includes submarine classes, and features such as radar,

improved torpedoes, and radar detectors.

Best Careers

This option displays the top careers to date.

Main Menu

This button returns to the Main Menu.

Page 7

SILENT

HUNTER

11 THE CAREER MENU: Continue a Career

SILENT

HUNTER

12 THE CAREER MENU: Base Menu Options

Continue a Career

This button opens a menu where a saved career may be continued,

reviewed, or deleted. The Career Roster lists the names that have been

entered for the careers in progress. To continue to play a particular career,

left-click on it to highlight it and left-click on the Select button or double

left-click to resume that career.

The View button displays the progress of a highlighted career. The Delete

button deletes the highlighted career.

After selecting a career, the Base Menu appears.

Start War Patrol

This option begins a war patrol. The submarine will be assigned a patrol

area in which to operate. Any changes to the realism settings must be

done now, while still in port. See the “Realism” section on page 6 for

more information.

Prior to departure initial instructions are issued for any particular missions

the submarine is to undertake. While on the mission, occasional radio messages will update the commander of enemy activity in the area.

Ending a War Patrol

A war patrol continues until:

♦

The submarine is destroyed.

♦

The submarine is damaged beyond the ability of the crew to repair it.

♦

The submarine runs out of supplies (fuel and /or ammunition).

♦

The submarine is ordered back to base at the end of the patrol.

Depending on the success of the war patrol, the commander may be

rewarded. Success is measured in a variety of ways, and reassignment is

possible in cases of poor performance.

Tonnage

The primary yardstick of success for a submariner during WWII was ships

sent to the bottom, whether merchant or military. The tonnage sunk figure

does not include ships that were damaged but did not actually sink.

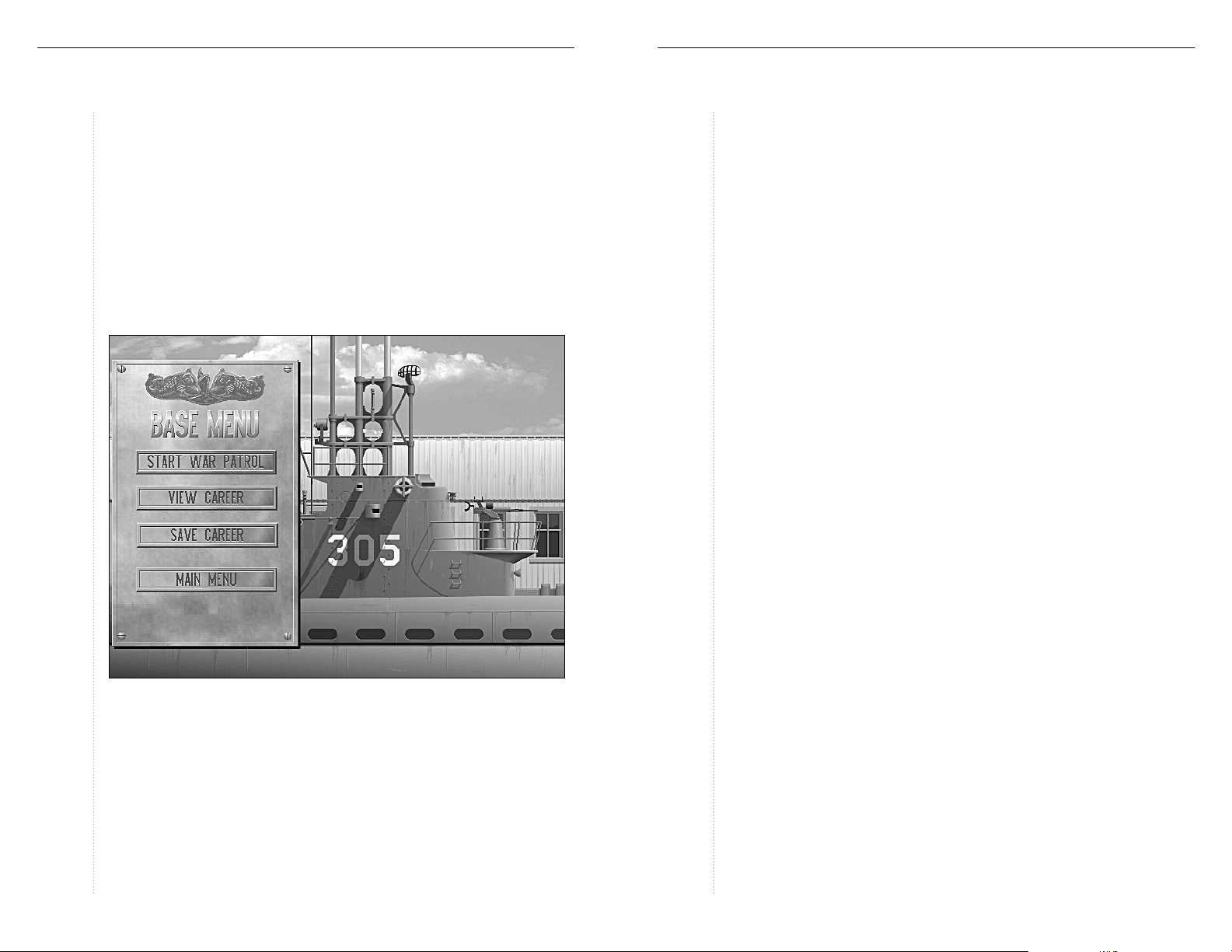

Base Menu Options

The campaign aspects of S

Menu — campaigns are made up of a series of war patrols. While at

base several activities are possible:

♦

Start a war patrol.

♦

View the top scores for commanders in that campaign.

♦

Examine the record of the active commander.

♦

Visit the Officer’s Club for news and rumors.

♦

Save the active career.

♦

Return to the Main Menu.

ILENTHUNTER

are managed from the Base

Score

The score takes into account ships damaged or sunk, the overall mission

difficulty, and the difficulty based on realism level. The score for damaged

ships is based on the amount of damage done. The higher the realism level,

the higher the score.

Promotion, Medals, and Awards

While referred to on board as “Captain,” officers commanding submarines

were all Lieutenant Commanders or Commanders; all officers of higher

rank either moved to a different command or were assigned shore duty. For

this reason, submarine commanders in S

in order to remain historically accurate. Reassignment for inadequate performance is always possible.

ILENTHUNTER

will not be promoted

Page 8

SILENT

HUNTER

13 THE CAREER MENU: Base Menu Options

Medals are awarded based on the results of a particularly productive war

patrol. The medals that are possible, in order of precedence are:

♦

Medal of Honor

♦

Distinguished Service Medal

♦

Navy Cross

♦

Silver Star

♦

Bronze Star

Submarine crews may also earn either a Presidential Unit Citation or a Unit

Citation if the overall record of the submarine is good and it has an exemplary war patrol.

View Career

The career of the active submarine commander can be viewed using this

option. In addition to the name of the commander’s submarine and the

base he is assigned to, useful information is shown including the number of

ships sunk, the total tonnage sunk, and any medals or commendations the

commander or submarine have been awarded.

SILENT

HUNTER

14 CONTROLS: The Smart Mouse Pointer

CONTROLS

The Smart Mouse Pointer

The submarine is managed using controls and displays at several stations

around the submarine which are accessed via the control room. Move the

mouse pointer until it changes from an arrow to the name of the station and

left-click to change the view. Each station is represented by one or more

screens. Moving the mouse pointer over the controls and gauges at each

station is the fastest way to determine which are controls and which are displays because the mouse pointer changes from an arrow to a reticule with a

word above it, such as SET, SELECT, or FIRE.

♦

Settings on dials are changed by moving the reticule to the desired

position on the dial and left-clicking.

♦

Buttons are pressed by moving the mouse pointer over the button and

left-clicking.

Using the Function Keys (F1 - F10)

The stations listed below can also be reached using the corresponding

function keys:

FUNCTION KEY STATION

F1 ................................... Control Room

F2.................................... Up Scope/Periscope

F3.................................... Target Bearing Transmitter

F4.................................... Bridge

F5.................................... Charts

F6.................................... Torpedo Data Computer

F7.................................... Gauges

F8.................................... Status

F9.................................... Radar

F10.................................. Logbook

Alt F4.............................. Deckgun

Setting the Detail Level

Once a mission or war patrol has begun, pressing Alt-D opens the Detail

Level box. Graphic features that enhance the appearance but may hinder

play of S

wakes can be toggled on or off using this box. In addition, visibility range

can be increased in increments of one mile using this control. Left-clicking

in the upper left corner returns to play.

ILENTHUNTER

such as clouds, waves, land texture, ship and torpedo

Page 9

SILENT

HUNTER

15 CONTROLS: Control Buttons

SILENT

HUNTER

16 CONTROLS: Control Buttons

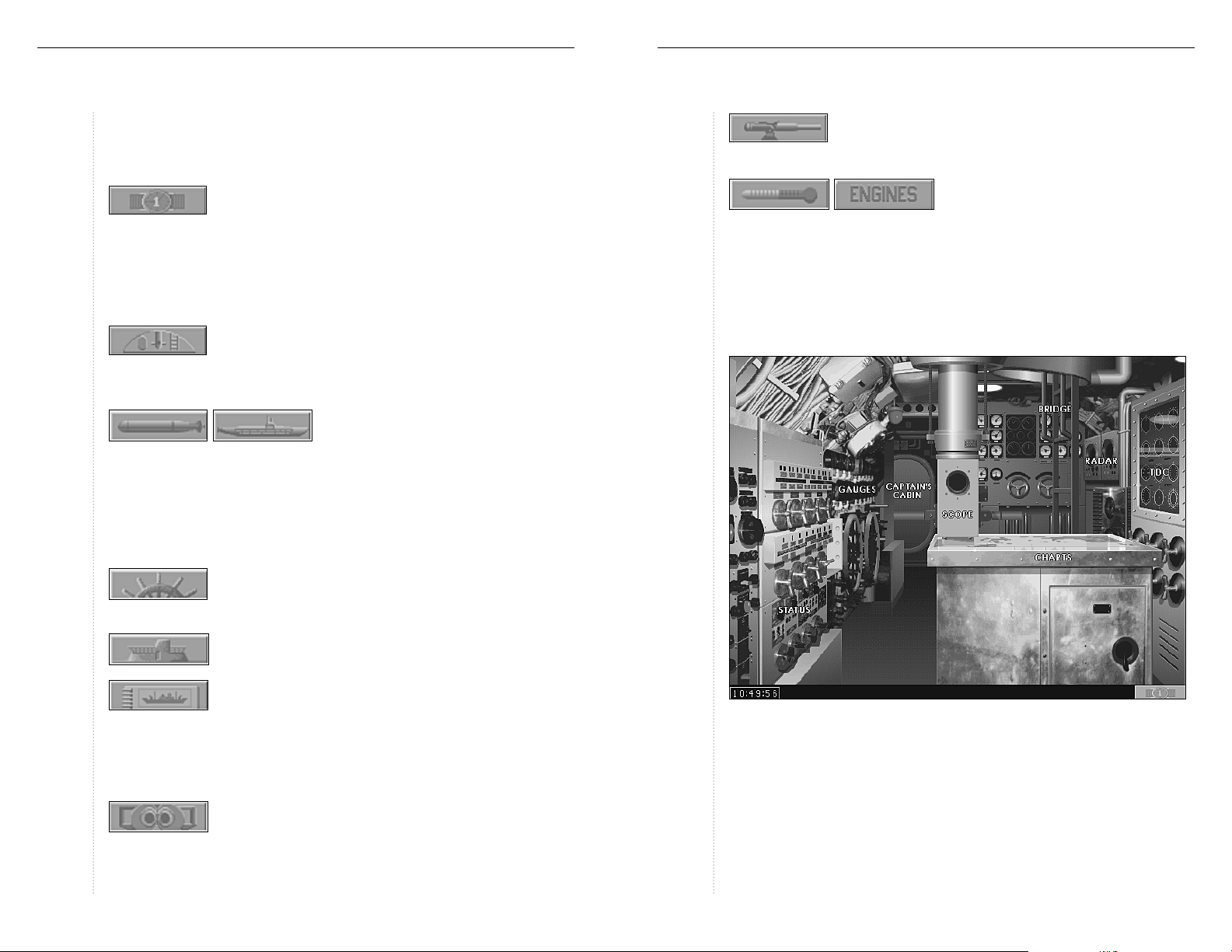

Control Buttons

At each station there are buttons at the bottom of the screen for changing

certain game settings, stations or accessing features.

The rate at which time passes can be changed by left-

clicking this button, from 1x to 256x. At 1x time passes at

the normal rate. This button appears on all stations. The + key increases

compression, while the – key decreases time compression. The Enter key

returns the time rate to 1x. Note: During encounters with enemy ships,

the maximum rate of time compression is 16x. While torpedoes are active the

maximum rate is 8x.

This common button is used to return to the Control

Room from almost any station on the submarine. The

control room button is available on the Gauges, Status, Captain’s Quarters,

Periscope, Charts and TDC station screens.

This button brings up the first of three

parts of the Torpedo Data Computer (TDC)

for use at the periscope or the Target Bearing Transmitter (TBT). This button

appears on the periscope screen and the TBT screen. At the Status Station, the

Torpedo button toggles the view to the Torpedo Room station where the torpedo tubes are reloaded displayed combat and the status of torpedo reloading

can be found. The button is replaced with the Status button while the Torpedo

room is visible. See the Status Station section on page 38 for more information.

This button is found on the Bridge station and goes to

the Deck Gun station. For more information see the

“Deck Gun” section starting on page 36.

The Bathythermograph button is located

at the Gauges station. It replaces the

“Christmas tree” display, which indicates the usage of engines to charge batteries, with the bathythermograph. For more information see the “Thermal

Layers and the Bathythermograph” section starting on page 26. When the

bathythermograph is visible, the Bathythermograph button switches to a

button marked “Engines” which restores the Bathythermograph button and

the Christmas tree display.

The Wheel button changes the “controls” portion of any

screen to the Maneuver Controls subset. This button

appears on the periscope, the TBT station, and the Chart station.

The Bridge button returns to the Bridge view from

the TBT and Deck Gun stations.

Pressing this button opens the Ship Identification

Manual which is normally stored in the Captain’s

Quarters. It contains views of the ships that Naval Intelligence has determined are likely to be encountered. This option is available at the TBT,

Periscope stations, and the Captain’s Cabin. For more information see the

section on the Captain’s Cabin starting on page 17.

The Target Bearing Transmitter (TBT) button is located

on the Bridge and contains the same components as the

Torpedo Data Computer (TDC), divided into three sections to fit at the bottom of the screen. For more information see the section on the TBT

starting on page 35.

COMMANDING THE SUBMARINE

The control room is the nerve center of the submarine. All other stations

necessary to fight and maneuver the submarine are accessed from the control room. Other stations are reached from the Control Room by moving

the pointer until it changes to a word, for example Charts or Gauges. Leftclicking changes the view to that particular station. Note: On actual U.S.

submarines the periscope was accessible in the conning tower. It has been

placed in the Control Room in S

ILENTHUNTER

for ease of use.

Page 10

SILENT

HUNTER

17 COMMANDING THE SUBMARINE: Captain’s Cabin

SILENT

HUNTER

18 COMMANDING THE SUBMARINE: Charts

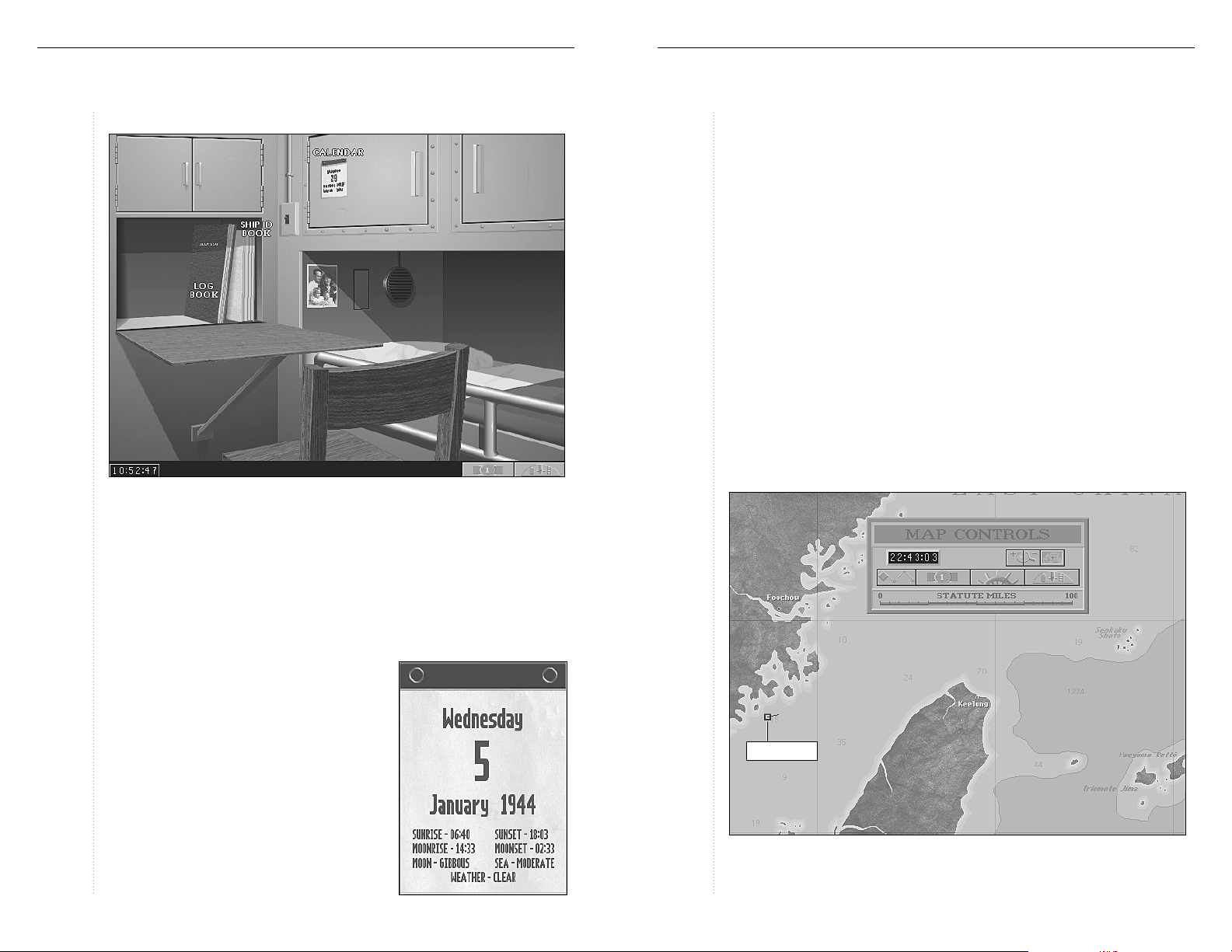

Captain’s Cabin

Ship Identification Manual

The Ship Identification Manual on the captain’s bookshelf is a valuable tool in

prosecuting the war against the enemy and not our own shipping. The Ship

Identification Manual contains views of thirteen classes of enemy vessels at

various angles. The displacement, length and maximum speed in knots are

also listed. A copy of this manual is available on the bridge to be used with the

Target Bearing Transmitter (TBT) and at the periscope.

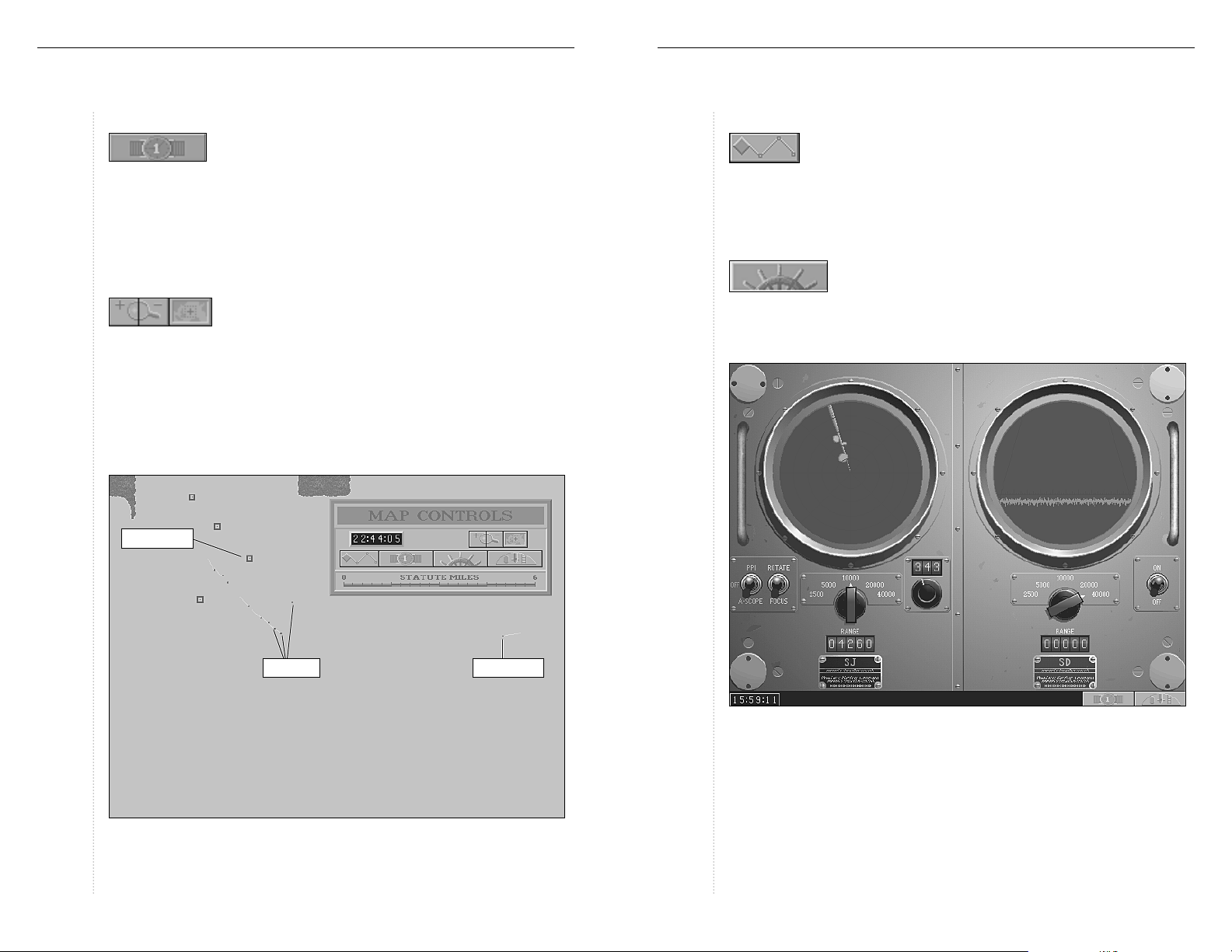

Charts

The Charts station is reached by pressing F5, or moving the pointer until it

reads Charts. The Charts station contains charts of the current patrol area,

showing important features such as depth information, enemy bases, shipping lanes, and ports of call. Visible enemy ships and reports of enemy

vessels are indicated on the chart for tracking purposes depending on the

realism level. Boxes that are available while viewing the charts allow for

maneuvering, setting way points along a course and general map controls.

At high levels of zoom the submarine is represented by a blue box trailing a

line away from its heading.

Sonar

At lower speeds the submarine’s sonar can detect other vessels. This is indicated on the map by a line along the relative bearing of the target. The line

is either gray, representing a set of low-speed screws, or orange, representing high-speed screws. High-speed screws are usually warships, while

low-speed screws can be either a merchant ship of some sort, or a warship

travelling at low speed.

Map Controls

Logbook

The Logbook can be viewed in the Captain’s

Cabin or by pressing F10. This is where the

crew’s victories are recorded as enemy shipping is harried across the Pacific.

Calendar

Left-clicking here shows more than the current date. Weather information, the phase of

the moon, and rising and setting times for the

sun and moon are also listed here.

Player Submarine

Page 11

SILENT

HUNTER

19 COMMANDING THE SUBMARINE: Charts

SILENT

HUNTER

20 COMMANDING THE SUBMARINE: Charts

Time Controls

The local time is displayed above the Time Compression

control button, and at the bottom left at most other stations. Activating Time Compression allows the rate time passes to be changed

from 1x to 256x. At 1x time passes at the normal rate. The + key increases com-

pression, while the –key decreases time compression. The Enterkey returns

the time rate to 1x. Note:Because of the complexity of this simulation, some

features may not operate smoothly at high rates of time compression.

Zoom and Centering Buttons

The Zoom controls allow a bird’s-eye view of the submarine

and other ships at the highest levels of magnification.

Zoom in by left-clicking on the “+” button, which turns the pointer into a

frame. Drag the frame over the section of the map to be viewed. At this

point, pressing the “Z” key increases the level of zoom, represented by the

size of the frame shrinking. Pressing the “X” key will increase the size of the

frame, decreasing the amount of zoom. Left-clicking a second time engages

the zoom and changes the view. At zoom levels below a certain point, some

map features such as depth gradients are not visible.

Reported Contact

Way Point Selection

The Way Point Selection button allows navigational way-points

to be set or cleared. Left-clicking on the map establishes a

course for the submarine which is followed until cleared from this panel by

pressing the CLEARbutton, when the course is completed, or if the manual

helm is used to override it.

Navigation

The Navigation button opens a box showing the Engine

Room Telegraph, the Manual Helm, the Speed Gauge,

Course Indicator and the Depth Control. The two buttons at the bottom

return to the Map Controls or the Control Room. For more information on

these controls see the “Gauges Station” section on page 23.

Visible Ships

Moving the cursor to the edge of the screen allows the entire map screen to

be shifted in any direction. The Centering button returns the submarine to

the center of the screen.

Player Submarine

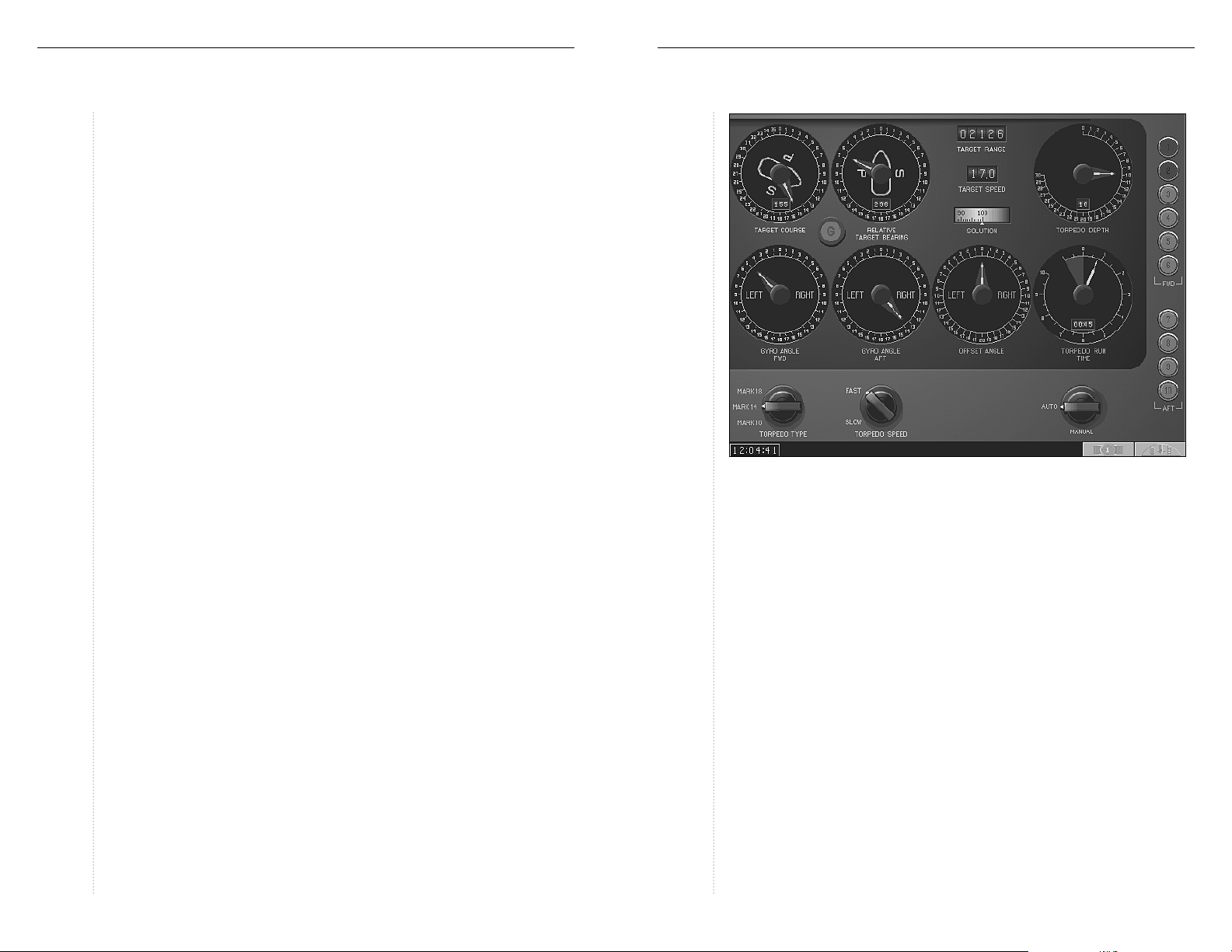

Radar

The Radar station contains two radar range finding panels. On the left is

the SJ surface radar, on the right is the SD aerial radar. Both types of

radar can be tuned using the range knob; the scope will show an approximate representation of the distance to the target object, the digital readout

below the knob gives more precise range information. Note: Neither will

function if the submarine is below 45 feet.

Page 12

SILENT

HUNTER

21 COMMANDING THE SUBMARINE: Radar

SJ Radar

SJ surface search radar was installed on all submarines built after the war

started, and six of the older S-class submarines were refitted in 1943. Radar

made night surface-actions practical for submarines by generating accurate

range information.

SILENT

HUNTER

22 COMMANDING THE SUBMARINE: Torpedo Data Computer

The SJ radar represented in S

Plan-Position Indicator (PPI) and A-scope.

The PPI screen shows the direction the radar’s antenna is pointing with a

line that sweeps through 360 degrees. When a contact is made, the radar

produces a blip on the screen. Distance to the contact is indicated on the

digital readout below the central knob, and by the blip’s relative position on

the radar screen.

An A-scope contact doesn’t show the direction on the radar screen the way

the PPI does. The direction can be derived by the digital bearing readout on

the right side of the SJ console. A contact is represented as a spike in the

baseline reception, the size of the spike representing the size of the contact.

Contact range is indicated on the digital readout and by where the spike

appears on the screen. The farther to the left the spike appears, the closer

to the submarine the contact is.

The antenna can be aimed by switching from Rotate mode to Focus. This

allows the PPI scope to be aimed by left-clicking right on the scope screen

or by left-clicking the bearing knob. The A-scope is aimed using the bearing

knob on the SJ panel. The radar’s aim can be fine tuned by left-clicking on

the digital display above the knob to adjust the bearing of the antenna by

hundreds, tens, or single degrees. The SJ radar can be toggled on or off

using Alt-S. Left-clicking on the Range knob allows the radar coverage to

be fine tuned by aiming the radar at the bearing chosen.

ILENTHUNTER

can operate in two modes:

SD Radar

All submarines used in WWII were equipped with SD radar to prevent them

from being attacked by aircraft. The SD radar in S

scope variety, which reveals distance but not direction of aircraft detected

on the screen. A contact is represented as a spike in the baseline reception.

The SD radar can be toggled on or off using Alt-A.

ILENTHUNTER

is of the A-

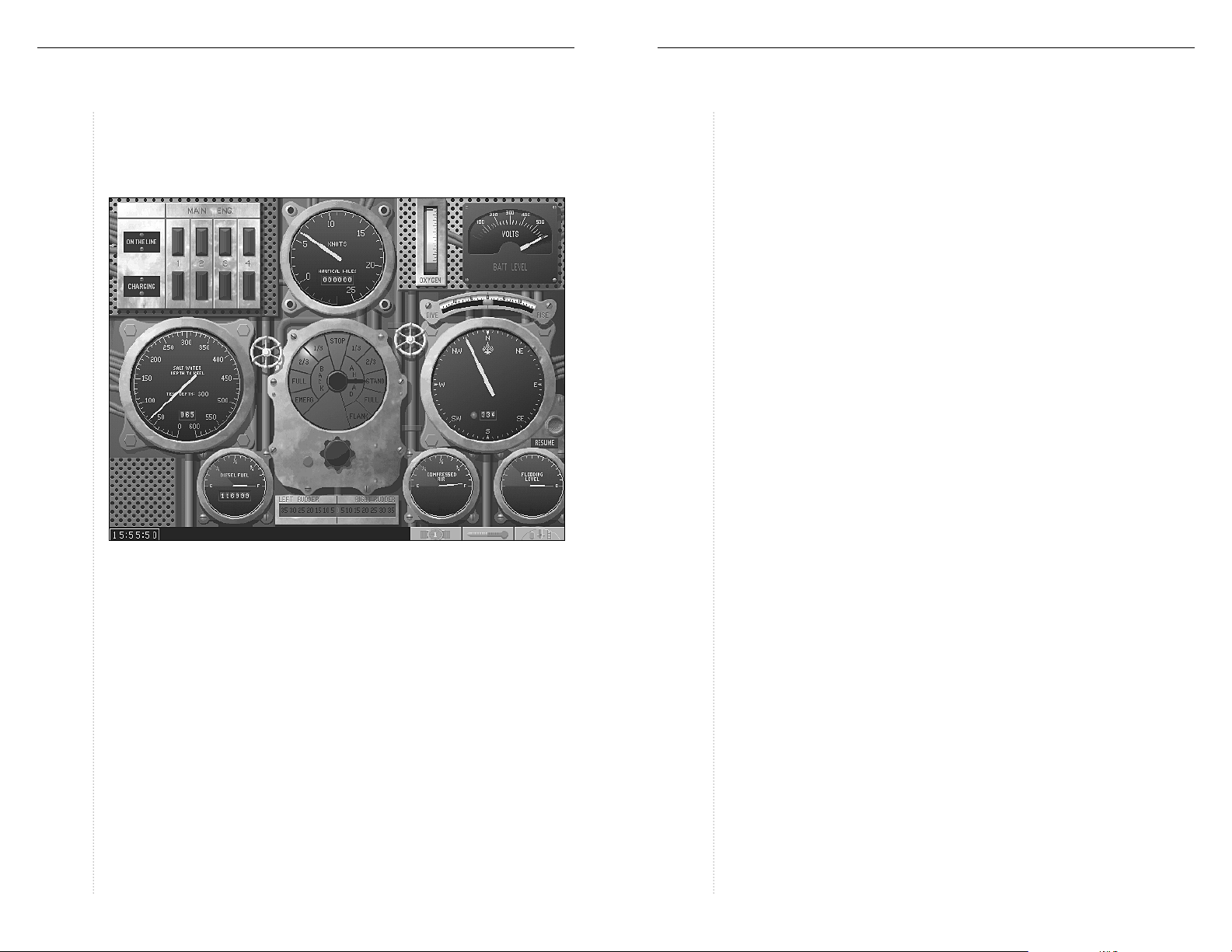

TDC (Torpedo Data Computer)

The controls on the Torpedo Data Computer (TDC) were remarkably

sophisticated for the period. The firing officer input the estimated speed

and course of the target ship, and the TDC compared this information with

the sub’s course and bearing and fed this information to the gyroscope in

the torpedo. Once fired, the torpedo ran straight for roughly 20 yards, then

altered course based on the gyro setting to intercept the target vessel.

There are three ways to access the TDC:

♦

At the main TDC station in the control room (or by pressing F6).

♦

Using the TBT binocular mount on the Bridge.

♦

Through the periscope.

The main TDC station has the complete set of controls and indicators for

setting and firing torpedoes, however there is no way to take a bearing on

the target from the TDC itself. The Target Bearing Transmitter (TBT) and

periscope TDC controls are split into three partial screens which are

accessed using a control knob. The launch buttons are arrayed on the right

side of the TDC, forward tubes on top, aft tubes below.

Page 13

SILENT

HUNTER

23 COMMANDING THE SUBMARINE: Torpedo Data Computer

SILENT

HUNTER

24 COMMANDING THE SUBMARINE: Gauges Station

Most torpedo attacks will be launched from the periscope in the control room or

the Target Bearing Transmitter on the bridge. See the “Using the Local TDC”

section on page 29 for information on using the TDC for making an attack.

Gauges Station

In S

ILENTHUNTER

station and consist of the depth gauge, the compass, the manual helm, the

engine-room telegraph and the speed gauge. This station can also be

reached from anywhere on the submarine by pressing F7. There are also

displays for the electric motors, battery charge status, as well as gauges

showing the amount of compressed air, the level of flooding, the amount of

oxygen remaining, the remaining diesel fuel and the dive angle. The buttons in the lower right corner open the Time Compression box, toggle the

Bathythermograph, or return to the Control Room.

Maneuvering the submarine was the job of the diving officer, under the

command of the captain or the executive officer. Most submerged

maneuvering was done by dead reckoning using navigational fixes taken

while on the surface. The sub’s speed and course were tracked on navigational charts, which were the only means of determining the submarine’s

, the primary maneuver controls are found at the Gauges

position. Strong ocean currents, inaccurate charts and long periods operating

submerged without fixes created the possibility of running aground, particularly in the shallow seas of the Solomon, Marshall, and Philippine Islands.

Manual Helm

The submarine can be turned to port or starboard by left-clicking on the

Manual Helm, or pressing the left- or right-arrow key on the keyboard.

The 0 setting indicates a straight ahead course, barring wind and current.

Turns of up to 35degrees may be made to port or starboard by left-clicking

over that number on the Helm. The submarine continues to turn until the

Helm is returned to the 0setting, either by left-clicking on the 0or by pressing the arrow key which is opposite the current direction of turn until the

Helm reads 0; in other words, if left rudder is being applied, press the right

arrow key until the helm returns to 0. Pressing the “H” key establishes the

current heading as the new course and returns the Manual Helm setting to 0.

Pressing the “V” key restores the view to directly ahead of the submarine.

Compass

The course of the submarine can also be controlled using the compass. The

white needle indicates current course while the red needle indicates the

desired course. Left-clicking on the compass lays in a course, and the helm

responds by gradually turning the ship onto that course. The manual helm

should be used for radical course changes, such as evasive maneuvers or

attack maneuvers. A course laid-in previously can be returned to by leftclicking on the Resume button or by left-clicking on the compass.

Diving Controls

In S

ILENTHUNTER

depth on the depth-gauge or using a convenient keyboard command. The

dive angle is displayed on the inclinometer. Below 65 feet, the periscope

automatically retracts. Diving and surfacing are controlled by the diving

officer at the captain’s direction.

Diving involves the release of gas from the ballast tanks to reduce the submarine’s buoyancy to a point where the weight of the vessel overcomes the

displacement of water. As the submarine becomes less buoyant, the dive is

controlled using the bow planes and the electric motors. Surfacing is the

opposite of diving; compressed air is forced into the ballast tanks to replace

water taken on when diving. This creates a positive buoyancy, causing the

submarine to rise slowly. The bow planes and motors are used to control

diving and surfacing is handled simply by setting the dive

Page 14

SILENT

HUNTER

25 COMMANDING THE SUBMARINE: Gauges Station

SILENT

HUNTER

26 COMMANDING THE SUBMARINE: Gauges Station

the rate of change in depth. Once under water, with a neutral buoyancy,

the submarine maneuvers to different depths using the bow planes and

motors exclusively unless an emergency occurs where depth must be

gained or lost quickly. The diving planes can be controlled manually using

the “down” arrow key to cause the submarine to dive, the “up” arrow key to

cause a submerged submarine to climb, and the “5” key on the number

keypad to resume a straight and level course

The following keyboard equivalents exist for certain standard maneuvers to

simplify the process of changing depth:

♦

B – Blow tanks; emergency surface at maximum speed using your compressed air reserves in an inefficient manner Note: Using this command

leaves the submarine on the surface with few options since it takes time

to restore the compressed air.

♦

C – Crash dive; the submarine heads for 200 feet at maximum speed and

dive angle.

♦

P – Takes the submarine to periscope depth (65 feet).

♦

R – Takes the submarine to radar depth (45 feet).

♦

S – Surface normally.

Compressed Air Gauge

The number of times the submarine can change depth is dependent on the

supply of compressed air used to force water out of the ballast tanks. This

gauge indicates the amount of compressed air remaining. It is important to

be aware of the status of the submarine’s compressed air supply because

without compressed air the only way to change depth is by using the diving

planes and the electric motors. Once these tanks are empty, they can only

be recharged by sailing on the surface. This process takes an hour or two

depending on the amount of air required. If the submarine finds itself on

the bottom with no compressed air, returning to the surface may be an

impossible feat.

Thermal Layers and the Bathythermograph

In any large body of water, there are layers

where the water is warmer or cooler. The

bathythermograph plots water temperature

against depth to identify the location of these

thermal layers. The benefit of this is that

these layers reflect sound waves, which travel

very well through water, making it more difficult to locate a submarine using hydrophones or sonar. A submarine

beneath the thermal layer becomes nearly undetectable.

As the submarine descends, the bathythermograph indicates the temperature at every depth. When the bathythermograph indicates that the

temperature has dropped, this indicates that a thermal layer exists at that

depth. Diving below one of these layers is a good way to escape an enemy

ASW vessel.

Engine-Room Telegraph and Speed Gauge

Control of the submarine’s diesel engines and electric motors is performed in

the engine room. The Captain of the submarine forwards his orders by way of

the engine-room telegraph. The telegraph’s settings indicate the amount of

thrust the engines and motors are set to provide, either forward or reverse.

The speed of the submarine is indicated on the speed gauge and varies based

on sea conditions, damage, and whether the submarine is running submerged

or on the surface. Except at very low speeds, there is no way to come to a rapid

stop. Inertia causes the submarine to continue moving until the drag of the

water causes it to slow to a stop, unless reverse thrust is employed. The number keys across the top of the keyboard can also be used to control speed:

KEY TELEGRAPH SETTING

0...................................... All Stop

1...................................... Ahead 1/3

2...................................... Ahead 2/3

3...................................... Ahead Standard

4...................................... Ahead Full

5...................................... Ahead Flank

6...................................... Reverse 1/3

7...................................... Reverse 2/3

8...................................... Reverse Full

9...................................... Emergency Reverse

Page 15

SILENT

HUNTER

27 COMMANDING THE SUBMARINE: Gauges Station

Engine Status Indicator

The “Christmas tree,” so named for the red and green lights it features,

indicates which of the diesel engines are engaged in propelling the submarine or charging the batteries used to drive the electric motors. The panel

contains one green light and one red light for each engine on the submarine. When a diesel engine is being used to charge batteries the red light is

on, when the engine is being used to drive the submarine the corresponding green light is lit.

Voltage and Fuel Gauges

The state of battery charge is shown on the voltage gauge. When the electric motors are on line, the voltage level drops as batteries are discharged.

When the batteries are being charged using the diesel engines, one or more

of the red charging lights are lit and the needle climbs back to full charge.

It can take several hours running on the surface to recharge batteries. Most

of the submarines in S

low speed, but running at flank speed while submerged will exhaust battery

capacity quickly.

ILENTHUNTER

can run submerged for many hours at

SILENT

HUNTER

28 COMMANDING THE SUBMARINE: Up Scope

The fuel gauge shows the volume of diesel fuel remaining, with a digital

counter for the number of miles available from the remaining fuel. Note: The

amount of fuel carried by submarines was large enough to allow for extended

missions, but was not inexhaustible. If the submarine runs out of fuel, the

only margin of safety lies in the charge level on the batteries. If the submarine runs out of fuel in enemy waters, it is likely to be destroyed or captured.

Flooding Gauge

This gauge indicates the level of danger that flooding represents is in the

event that the submarine takes damage which ruptures the pressure hull so

that the submarine begins to take on water. The great danger of flooding is

that the submarine may gain so much weight that the motors cannot lift it

to the surface again.

Up Scope (or Periscope Station)

Left-clicking on the periscope shaft, or pressing F2, raises the periscope for

viewing the surface, navigation, or fire control. The periscope cannot be

employed at depths below 65 feet, and is automatically retracted when diving below that depth. The periscope also retracts automatically when

destroyed or damaged.

Moving the pointer to the handles on either side of the periscope activates

the Rotate Left or Rotate Right controls. Left-clicking when these commands

are visible, turns the periscope in the appropriate direction, through 360

degrees. At the top of the screen is the Relative Bearing Indicator, which

shows the bearing of any object viewed in the periscope relative to the submarine’s heading.

The right handle of the periscope is also used to control the zoom factor of

the periscope. When the pointer nears the right side of the periscope, it

changes to the Zoom command. Left-clicking while this command is active

increases the magnification through the settings 1x, 2x, 4x, and 8x.

Pressing the “Z” key achieves the same result. The periscope can be lowered

or raised from any station by pressing Alt-P.

When first activated, the periscope screen shows maneuver controls to

either side. These controls operate in the same manner as their counterparts at the Gauges station. The manual helm allows the submarine to be

steered, the course can be set using the compass, and the submarine can be

submerged or surfaced using the depth control. The Ship Identification

Manual can be viewed at this station using the button at the bottom of the

screen. Left-clicking on the Torpedo button or pressing the “T” key brings

up the Position Keeper panel for the local TDC.

Page 16

SILENT

HUNTER

29 COMMANDING THE SUBMARINE: Up Scope

SILENT

HUNTER

30 COMMANDING THE SUBMARINE: Up Scope

Using the Local TDC

The full TDC panel is not visible from the Periscope or the Target Bearing

Transmitter (TBT) stations, but has been divided into three separate panels

which appear to the right and left side of the Periscope and across the bottom

of the TBT. Some components of the TDC which do not change are the

Auto/Manual and Panel Selection switches and the firing buttons which are

just above the right handle of the periscope and at the far right of the TBT.

Pressing the “N” key restores the maneuver controls panel.

Left-clicking on the panel selection knob changes to the Angle Solver panel

which has the Gyro Angle Forward and Aft dials and Offset Angle dial. The

Offset Angle dial is used to establish a “spread” of torpedoes by locking a

course offset into each torpedo from the first torpedo fired. The Gyro Angle

Forward and Aft dials are primarily indicators unless the TDC is set to manual, when they become active for setting the offset from the submarine’s

heading that the torpedo will need to intercept the target.

For example, if the target is dead ahead, the relative target bearing would

be 0 degrees. The Relative Target Bearing dial shows an arrow pointing

straight up, aligned along the centerline of the submarine.

Calculating a firing solution is a very complex process. For more information

about the basic formulas of fire control, see Appendix C on page 73.

The Torpedo Depth setting dial and Torpedo Run Time dial are found on the

Torpedo Data panel, as are the Torpedo Speed knob and Torpedo Type knob.

The depth setting control is used to adjust the depth that torpedoes run.

Different classes of ship have a different draft, and a torpedo set to hit an aircraft carrier will pass harmlessly beneath a destroyer.

There is also a Torpedo Speed knob where the speed can be changed for

variable speed torpedoes. Common practice was to fire torpedoes at the

highest speed available unless the target is motionless. A slow torpedo is

more likely to be evaded by wary prey. The slow speed setting is useful

when shooting at stationary targets at long range, such as inside a shallow

harbor, where a close approach is too dangerous.

The panel that is visible the first time that a local TDC station is seen, is the

Position Keeper panel. It shows the Target Course and Relative Target

Bearing dials as well as the Target Range, Target Speed and Solution indicators. The Solution dial indicates the quality of any firing solution as a

percentage, from zero to one hundred percent. When a potential target is

visible in the eyepiece, a red arrow will flash beneath the target indicating

that the TDC is receiving information on that target. The longer a target is

in view, the more accurate a firing solution the TDC will provide. Locking

the target into the TDC allows the TBT or periscope to be used to view the

rest of the horizon, while the TDC continues to calculate. This is done

using the Mark button at the TBT station and the Spacebar at the Periscope.

Leaving the TBT or periscope station resets the TDC.

Making a Torpedo Attack

When using the TDC on automatic, the most important features to keep track

of are the target’s course, relative bearing, range, speed, and the firing solution quality. These are all located on the Position Keeper panel. All other

factors can be left to the game’s artificial intelligence (AI). The range indicator

is particularly important because a torpedo only arms itself after travelling 500

yards. The ideal range for torpedo launch at a moving target is between 500

and 1000 yards. Only targets that are at anchor or damaged should be shot at

from farther away than 1000 yards, particularly at higher levels of realism.

Once a target has been selected and locked into the TDC, the computer will

continue to calculate a firing solution. Making a successful torpedo attack

is a combination of having an accurate firing solution and being in range.

While the torpedoes used in U.S. submarines had maximum ranges of

between 3500 and 9000 yards, they were only used at ranges beyond 1500

yards in extreme situations.

Page 17

SILENT

HUNTER

31 COMMANDING THE SUBMARINE: Up Scope

Torpedoes can be fired by moving the mouse pointer over the illuminated

number buttons, which correspond to the torpedo tubes, and left-clicking

when the Fire reticule appears. When an appropriate range is reached,

between 500 and 1500 yards, and the Solution dial is reading an acceptable

level, preferably above 75%, fire away!

Torpedoes can also be fired by pressing the Alt key and the corresponding

torpedo tube number on the keyboard, so that pressing Alt-1 fires torpedo

tube one. The Alt-key combination is convenient because they can be used

to fire torpedoes from any station.

The Torpedo Run Time dial found on the Torpedo Data panel can be used

to monitor the time-to-target. Once torpedoes have been fired, escorts are

likely to attack the position the attack came from. Good tactical doctrine

suggests that keeping the periscope retracted until torpedo impact is imminent. Unlike the real world, submarines get credit for ships that sink,

whether anyone witnesses it or not.

Automatic vs. Manual

The Automatic/Manual knob determines whether the TDC continuously

feeds data into the torpedo gyroscopes or allows for manual correction of the

gyro setting. When set on automatic, the TDC automatically calculates a firing solution for whichever ship is being viewed through the periscope or

SILENT

HUNTER

32 COMMANDING THE SUBMARINE: Up Scope

Target Bearing Transmitter (TBT), as indicated by the flashing red arrow

below the target. Left-clicking on the Mark button on the TBT (or the Space

Bar when using the periscope) locks the current target into the TDC. At this

point, the red arrow below the target stops flashing and the TDC continues to

calculate a firing solution for that target even though it is not in view

through the scope. This allows the TDC to continue improving its firing solution while the viewing device is aimed elsewhere. This simulates the

continuous flow of information from periscope, radar, and hydrophones that

the submariners used to locate and destroy the enemy with.

Attempting to create a manual firing solution for torpedoes requires several

pieces of information about the target including the relative bearing, range,

course, and the speed. Without the continuous feed of information provided

by the TDC when on auto, the firing officer must make do with other sources.

The relative bearing, or angle on the bow, can be determined using the

periscope, TBT, or radar, if the submarine is equipped with it. The Officer

of the Deck will also call out the approximate bearing when contact is first

made. This information is programmed into the TDC using the Relative

Target Bearing dial. The mouse pointer will change to a reticule and the

word SET when moved over the dial. Simply left-click on the rim of the dial,

each increment represents 10 degrees, until the digital readout at the bottom of the dial is close enough to the desired bearing. The bearing of

targets can also be determined by the hydrophone operator when the submarine is travelling at low speed.

Determining range without the automatic setting will only be possible on

submarines equipped with radar. As a commander becomes more experienced, however, making range “guesstimates” will become easier. The

periscope has a set of graduated cross-hairs for that purpose. Once an estimated range is determined, move the mouse pointer over the Target Range

digital counter until the pointer becomes an upward pointing arrow. Leftclicking on a particular column increments the Target Range counter.

The target’s course should be entered in absolute terms; if the target is heading

due south, its course would be 180 on the compass. The easiest way to calculate this is by using the Ship Identification Book. If the target ship is facing the

submarine, start with a figure that is 180 degrees from the submarine’s course,

which can be found at any station with maneuver controls. Alter that number

to port or starboard based on the view angle as diagrammed in the Ship ID

Book. If the target ship is facing away from the submarine, the base course

starts similar to that of the submarine, which is then adjusted by the difference

in view. Adjust the Target Course dial in the same manner that the Relative

Target Bearing dial was adjusted, using the mouse pointer.

Page 18

SILENT

HUNTER

33 COMMANDING THE SUBMARINE: Up Scope

SILENT

HUNTER

34 COMMANDING THE SUBMARINE: Bridge

Speed is the most difficult to estimate. Once again, the Ship ID Book comes

into play. The general class of ship provides a reasonable estimate for the

target’s maximum speed. This information can be programmed into the

Target Speed counter in a similar manner to that of the Target Range. If all

else fails, target course and speed can be easily determined by switching the

TDC from manual to auto while the target is in view.

Once this information has been entered into the TDC, left-click on the red G

button in the center of the panel to generate a solution. When the G button is

illuminated, a solution is locked into the torpedoes. The Forward and Aft Gyro

Angle dials will present the gyro angle that is programmed into the torpedo.

These steps may need to be repeated until the solutions seems sufficiently

accurate. The Offset Angle dial is used at this point to establish a “spread” of

torpedoes by locking a course offset into each torpedo from the first torpedo

fired. Determining how wide a spread needs to be is a matter of experience, but

at ranges between 500 and 1000 yards, the offset should be from 5 to 10

degrees in order to get a sufficient amount of spread. At that point, fire the torpedoes! A distant booming sound in the hydrophones and an entry in the

submarine’s log will indicate the sinking of the enemy.

submarine while on the surface: the Depth Gauge, Compass, Manual Helm,

Engine-Room Telegraph and Speed Gauge. For information about giving

dive commands, see the “Diving Controls” section on page 24.

Compass

The course of the submarine can also be controlled using the compass. The

white needle indicates current course while the red needle indicates the

desired course. Left-clicking on the compass lays in a course, and the helm

responds by gradually turning the ship onto that course. The manual helm

should be used for radical course changes, such as evasive maneuvers or

attack maneuvers. A previously laid-in course can be returned to by left-clicking on the Resumebutton or by left-clicking on the compass.

Manual Helm

The submarine can be turned to port or starboard by left-clicking on the

Manual Helm, or pressing the left- or right-arrow key on the keyboard. The

0 setting indicates a straight ahead course, barring wind and current. Turns

of up to 35 degrees may be made to port or starboard by left-clicking over

that number on the Helm. The submarine continues to turn until the Helm

is returned to the 0 setting, either by left-clicking on the 0 or by pressing

the arrow key which is opposite the current direction of turn until the

Helm reads 0. Pressing the “H” key establishes the current heading as the

new course and returns the Manual Helm setting to 0. Pressing the “V” key

restores the view to directly ahead of the submarine.

Depth Gauge Compass

Relative Bearing

Engine Room Telegraph Speed Gauge

Manual Helm

Bridge

Climbing the ladder to the Bridge presents a 40-degree view of the surrounding waters. A set of maneuver controls is here for commanding the

Engine-Room Telegraph and Speed Gauge

Control of the submarine’s diesel engines is performed in the engine room. The commander of the submarine forwards his orders by way of the Engine-Room Telegraph.

The Telegraph’s settings indicate the amount of thrust the engines are set to provide,

either forward or reverse. The speed of the submarine is indicated on the Speed

Gauge and varies based on sea conditions, damage, and whether the submarine is

running submerged or on the surface. Except at very low speeds, there is no way to

come to a rapid stop. Inertia causes the submarine to continue moving until the drag

of the water causes it to slow to a stop, unless reverse thrust is employed. The number

strip across the top of the keyboard can also be used to control speed:

KEY TELEGRAPH SETTING KEY TELEGRAPH SETTING

0 . . . . All Stop 5.......... Ahead Flank

1 . . . . Ahead 1/3 6.......... Reverse 1/3

2 . . . . Ahead 2/3 7.......... Reverse 2/3

3 . . . . Ahead Standard 8.......... Reverse Full

4 . . . . Ahead Full 9.......... Emergency Reverse

Page 19

SILENT

HUNTER

35 COMMANDING THE SUBMARINE: Bridge

SILENT

HUNTER

36 COMMANDING THE SUBMARINE: Bridge

Moving the pointer to the far left or far right edges of the screen activates

the Rotate Left or Rotate Right controls. Left-clicking when these commands

are visible moves the view in the appropriate direction through 360

degrees. At the bottom of the screen, below the Manual Helm, is the

Relative Bearing Indicator which shows the bearing of any object centered

on the screen relative to the submarine’s heading.

Two other stations besides the Control Room can be reached from the

Bridge station, the Target Bearing Transmitter and the Deck Gun.

Moving the pointer to the grips on either side of the TBT activates the Rotate

Left or Rotate Right controls. Left-clicking when these commands are visible,

turns the periscope in the appropriate direction, through 360 degrees. Above

the eyepiece of the TBT is the Relative Bearing Indicator, which shows the

bearing of any object viewed in the TBT relative to the submarine’s heading.

The Zoom can be increased by left-clicking on the lever to the upper-right of

the zoom level readout on the right side of the TBT. On the top of the left

handle is the Markbutton which is used to lock targets into the TDC.

Other than the placement of dials on the three TDC panels, the use of the

TDC from the TBT station is exactly the same as from the periscope. For

more information about using the local TDC, see the “Using the Local

TDC” section on page 29.

Target Bearing Transmitter (TBT)

Left-clicking on the button with the binoculars on it changes to the Target

Bearing Transmitter (TBT) station. This station can also be reached from anywhere on the submarine by pressing F3. When first entered, the lower half of

the TBT screen contains a set of helm controls: Depth Control, Compass,

Engine Room Telegraph and Manual Helm. These controls operate exactly like

their counterparts at the Periscope station and the Gauges station. The Ship

Identification Manual can be viewed at this station using the button at the

bottom of the screen. Left-clicking on the Torpedo button or pressing “T”

brings up the Position Keeper panel for the local TDC. Pressing the “N” key

restores the navigation controls.

Deck Gun

Left-click on the Deck Gun button while on the Bridge to bring up the firing

controls of the deck gun. Pressing Alt-F4 from any location while surfaced

will also man the Deck Gun. Historically, deck guns were mainly used to finish off damaged ships rather than expend torpedoes. The odds of a submarine

winning a surface battle with a patrol boat or destroyer are very small. Some

classes of submarine carried two deck guns, such as the Tench class and the

Narwhal class. On these submarines, there is an additional Deck Gun button

with the letter ‘F’ for forward and ‘A’ for aft.

Page 20

SILENT

HUNTER

37 COMMANDING THE SUBMARINE: Bridge

The knob on the right side of the sighting scope raises and lowers the gun,

and the smaller knob on the left side of the sighting scope increases the

zoom from 1x to 2x, 4x, and 8x then back to 1x. Moving the pointer to the

handles on either side of the gun mount activates the Rotate Left or Rotate Right

controls. Left-clicking when these commands are visible turns the gun

mount in the appropriate direction, through 350 degrees. Note: the deck

gun cannot be trained on anything directly in front of the submarine since

that would force it to shoot through the conning tower. The same applies to

two mount submarines for the forward gun.

At the top of the screen is the Relative Bearing Indicator, which shows the

bearing of any object viewed in the sighting scope relative to the submarine’s heading. Below the sighting scope is the control panel for the deck

gun. The large black button on the left side of the panel fires the gun. The

knob above the target range display toggles control of the gun between

automatic and manual as does pressing Alt -G. When set on automatic, the

deck gun will fire at the nearest target until the gun is taken off of automatic, the submarine submerges, all the ammunition is used up, the

quality of aim drops below 80%, or the gun is damaged.

SILENT

HUNTER

38 COMMANDING THE SUBMARINE: Status and Torpedo Room Stations

The closer to the target, the more effective the deck gun can be. A red triangle

will appear in the sighting scope when the target has been acquired, and the solution dial shows the increasing solution quality. The solution dial indicates how

accurate the firing solution is for the deck gun. Speed, weather, and crew quality

all effect how accurate gunnery fire is. Press the fire button to fire the gun when

the target is centered in the cross-hairs of the sighting scope. The ready light

indicates the wait while the gun is reloaded and the shells counter shows the

amount of ammunition remaining.

Status and Torpedo Room Stations

Pressing F8 from any station, or moving the pointer until it changes to the

word Status while in the control room, shows the Damage Control and Status

station. The cut-away view of the submarine at the top of the screen contains

important areas of the submarine outlined in dark red. Damaged areas are

outlined in a brighter color red and may show some animation, for example,

flooding. When the cursor is over an area for which a damage report is available, it changes from an arrow to a cross-hair. Left-clicking causes the status

of that area to be shown on the Damage Control Report panel.

Below the cut-away are the display panels which show the status of important

ship systems. Each system has “Christmas tree” lights which allow a quick

status check of systems such as the torpedo tubes and specific engines.

If the submarine suffers damage, the Damage Control Report panel lists

important information about the damage. The location of the damage, the

severity of the damage, the repair status and time if repairs are possible,

and any effects the damage may be having on submarine operations.

Page 21

SILENT

HUNTER

39 COMMANDING THE SUBMARINE: Status and Torpedo Room Stations

Torpedo Room

There were three types of torpedoes available during the course of the war,

but not all submarines could carry all three types. Most of the submarines

built before the war, including the S-, Barracuda, and Narwhal classes,

were equipped to carry only the older Mark 10 torpedo. The later “fleet”

submarines, including the P-, Salmon, T-, Gato, Balao, and Tench classes

were equipped to carry the longer Mark 14 torpedoes. They could also

accommodate the Mark 10 and the Mark 18 electric torpedo when it

became available in 1944.

Left-clicking on the torpedo button on the Status Station screen shows

the contents of the forward and aft torpedo rooms. The submarines in

S

ILENTHUNTER

those loaded in the tubes. Once one or more torpedoes have been fired, the

reload process is automatic and is affected by the Realism setting chosen,

the crew quality level chosen, and any damage the submarine has sustained. Once the reloading process is under way, the time remaining until a

tube is reloaded can be determined by left-clicking over that tube.

carry between twelve and twenty-eight torpedoes including

SILENT

HUNTER

40 SUBMARINES

SUBMARINES

The submarines that were used in the desperate battles above and below

the waves of the Pacific included some which were the epitome of modern

technology and design. Others that saw duty were older, slower, more

cramped but contained crews whose bravery and dedication could not have

been overmatched by mere technology. Despite the brutal lessons taught

during World War I by the Kaiser’s U-boat wolfpacks, the development of

submarine technology held a position of secondary importance to that of

the battleship, aircraft carrier and cruiser. Changes were in progress at the

war’s beginning, but both the Pacific command, SubPac, and the Asiatic

fleet, still had antiquated S-class submarines.

Note: Torpedoes from the forward torpedo room cannot be moved aft

except while in port.

Page 22

SILENT

HUNTER

41 SUBMARINES: S-Class

SILENT

HUNTER

42 SUBMARINES: Barracuda

♦

S-Class

Displacement (in tons): . . . . 903 when surfaced; 1230 when submerged

Dimensions (in feet): . . . . . .265 x 21 x 13

Machinery: . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2 diesel engines; 2 electric motors

Max. Power (in hp): . . . . . . . 1800 surfaced; 1500 submerged

Max. Speed (in knots): . . . . . 14.5 surfaced, 11 submerged

Test Depth (in feet): . . . . . . .200

Range (in miles): . . . . . . . . .8000 at 10 knots surfaced

Torpedo Tubes: . . . . . . . . . . 4 forward; 1 aft; 12 torpedoes

Guns: . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1 – 4 inch

The oldest U.S. submarines to see combat in World War II were the S-class,

some of which had been launched as early as 1918. Six “sugar boats” were

stationed at Manila with the Asiatic Fleet and six with the Pacific Fleet at

Pearl Harbor. These submarines accounted for fourteen Japanese ships

including the destroyer Natsushio sunk by S-37 in February 1942 and the

cruiser Kako sunk by S-44 in August 1942.

Designed and built during the first World War, S-class submarines were

designed for a defensive role, to interdict other submarines along the

Atlantic coastline. When compared with the later fleet-type submarines,

they were more cramped, smaller, and had a shorter range. They featured

double hull construction with the ballast tanks on the outside of the pressure hull. The hulls were riveted together, as were most ships constructed

prior to the war. Underwater speed was deemed an important feature at the

time of their design, to enable the submarine to evade escorts. Speed was

sacrificed later for more dependable surface performance and safety features such as an enclosed bridge.

♦

Barracuda

Displacement (in tons): . . . . 2000 when surfaced; 2620 when submerged

Dimensions (in feet): . . . . . .341 x 27 x 14

Machinery: . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2 diesel engines; 2 electric motors

Max. Power (in hp): . . . . . . . 6700 surfaced; 2400 submerged

Max. Speed (in knots): . . . . . 18 surfaced, 8 submerged

Test Depth (in feet): . . . . . . .200

Range (in miles): . . . . . . . . .12000 at 11 knots surfaced

Torpedo Tubes: . . . . . . . . . . 4 forward; 2 aft; 12 torpedoes

Guns: . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1 – 5 inch

The Barracuda class were an early attempt at what would later be called the

fleet-class submarine. They were not as fast as the S-class when submerged,

but were larger and capable of longer patrols. None of the B-class submarines, Barracuda, Bass, or Bonita saw service during the war, except as

training vessels.

Page 23

SILENT

HUNTER

43 SUBMARINES: Narwhal

SILENT

HUNTER

44 SUBMARINES: P-Class

♦

Narwhal

Displacement (in tons): . . . . 2915 when surfaced; 4050 when submerged

Dimensions (in feet): . . . . . .371 x 33 x 15

Machinery: . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1 diesel engines; 2 electric motors

Max. Power (in hp): . . . . . . . 6000 surfaced; 2450 submerged

Max. Speed (in knots): . . . . . 17 surfaced, 8 submerged

Test Depth (in feet): . . . . . . .328

Range (in miles): . . . . . . . . .18000 at 8 knots surfaced

Torpedo Tubes: . . . . . . . . . . 4 forward; 2 aft; 26 torpedoes

Guns: . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2 – 6 inch

The Narwhal and Nautilus were submarine cruisers, large enough to

accommodate two 6-inch deck guns and capable of higher surface speeds

than the older S-class. They were derived from an earlier mine-laying

design, the Argonaut. In practice, the greater size needed to accommodate

the second deck gun made the submarine easier to detect and did not make

up for poor handling characteristics. The original diesel engines never delivered horsepower adequate to the task of maneuvering such a large vessel

and were replaced in 1940. Both submarines were used to deliver supplies to

guerrillas, transport commandos and coast watchers. Between them, they

managed to sink eleven Japanese ships including the destroyer Yamakaze.

♦

P-Class

Displacement (in tons): . . . . 1330 when surfaced; 2005 when submerged

Dimensions (in feet): . . . . . .300 x 25 x 13

Machinery: . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2 diesel engines; 2 electric motors

Max. Power (in hp): . . . . . . . 4300 surfaced; 2336 submerged

Max. Speed (in knots): . . . . . 19 surfaced, 8 submerged

Test Depth (in feet): . . . . . . .250