Page 1

WORLD WAR II FIGHTERS

CONTENTS

Air War in Western Europe . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Museum Map . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

The Exhibitions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Welcome Desk . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Info Room . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Hanger . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

War Room . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Jane’s WW II Fighters Museum Collection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

Other Aircraft on the Western Front . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

Basics of Flight . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52

Physics. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52

Movement Vectors. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54

Control Surfaces. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55

Basic Flight Maneuvers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 57

Combat . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61

Air-to-Air Combat . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 62

Air-to-Ground Combat. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 86

Credits . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 90

2

Page 2

AIR WAR IN WESTERN EUROPE

AIR WAR

in Western Europe

AIR WAR COMES OF AGE

In the First World War, air power emerged as a dramatic new dimension of

combat. German dirigibles had bombed London, causing panic. Biplanes

and triplanes soared, locked in dogfights over the trenches of France. The

men flying the fragile airplanes cut a romantic figure as they rose into the

sky. In an era full of fear at the regimentation and mass movement of man,

they were a welcome throwback to the knights of old, charging into

enemy lines either single-handedly or in small squadrons. Among even the

most bitter opponents, there was an almost medieval code of chivalry.

Aces such as Baron Manfred von Richthofen (the legendary Red Baron)

and his successor Hermann Goering became worldwide celebrities.

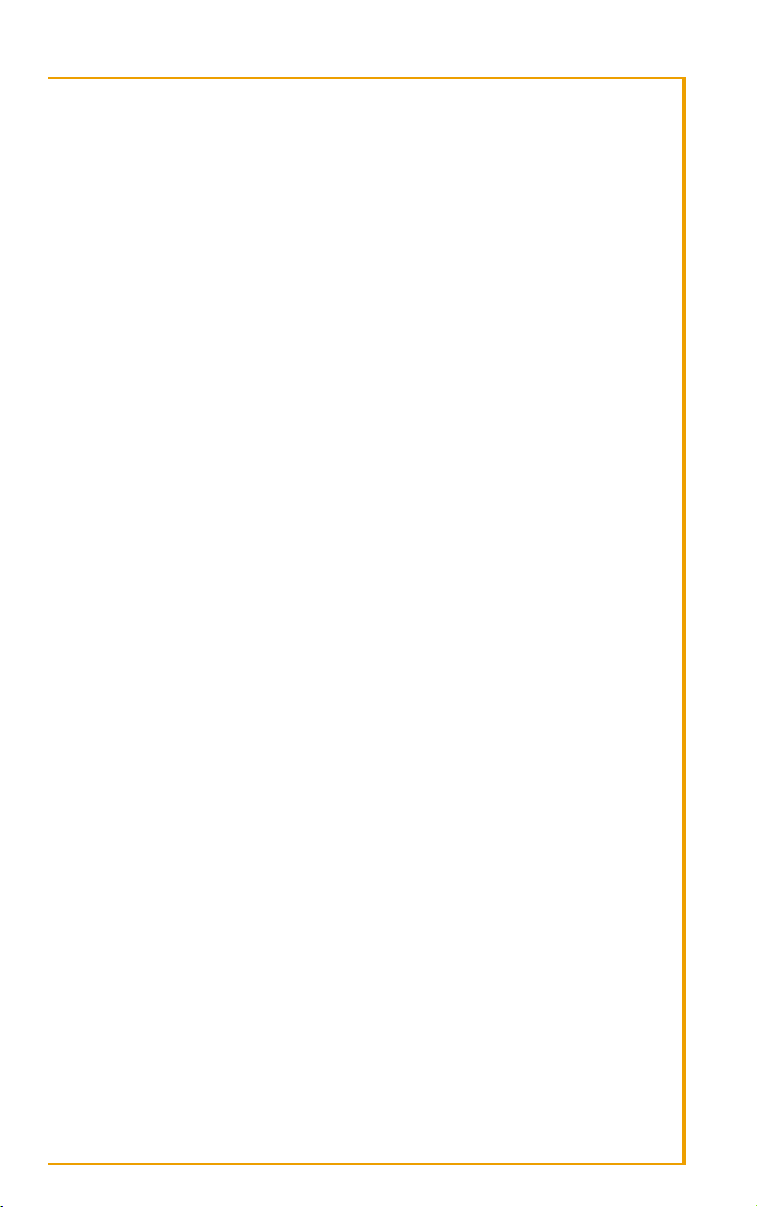

Urban devastation: the dream of Douhet and other prophets of air power.

While capturing the imagination, these initial air ventures had little effect

on the course of the war. Soon after the conflict ended, however, hints of

the future began to emerge. Stronger engines and better designs made new

strategies possible. The planes became bigger and faster, and were able to

carry heavier loads. The implications of these advances were set forth with

chilling vision by Italian Guilio Douhet, in his 1921 book Command of the

Air. He declared the era of ground war over; from now on war could be

fought and won in the air. Douhet proposed huge flying bombers that

could penetrate far behind lines of battle—bypassing the trench warfare

that had slowly eaten the morale of First World War armies—and pulverize enemy cities. The resulting panic and destruction would demoralize

one’s opponent and bring any war to a speedy conclusion.

3

Page 3

WORLD WAR II FIGHTERS

British and American designers read Douhet’s theories closely. Both began

designing large, long-range bombers with the intent, should war come, of

taking combat deep inside enemy lines. Both met strong internal

resistance to such a strategy: the thought of slaughtering huge numbers of

civilians was repugnant to the leadership, especially the American government of Roosevelt. It would be an ironic twist that those most reluctant

would be the ones most successful at wholesale urban destruction,

culminating in the atomic annihilation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Equally ironic was that those who would goad the Allies into such devastation never put much stock in Douhet’s book. Germany’s rebuilt air power

concentrated on the bomber as battlefield support, and their planes were

accordingly smaller and with much shorter range. In the initial sweep of

war, this would be highly successful. When the time came for attempts at

behind-the-lines civilian assault, those most eager to decimate populations

would find their air power poorly equipped to help in the project.

AIR POWER AND THE SECOND WORLD WAR

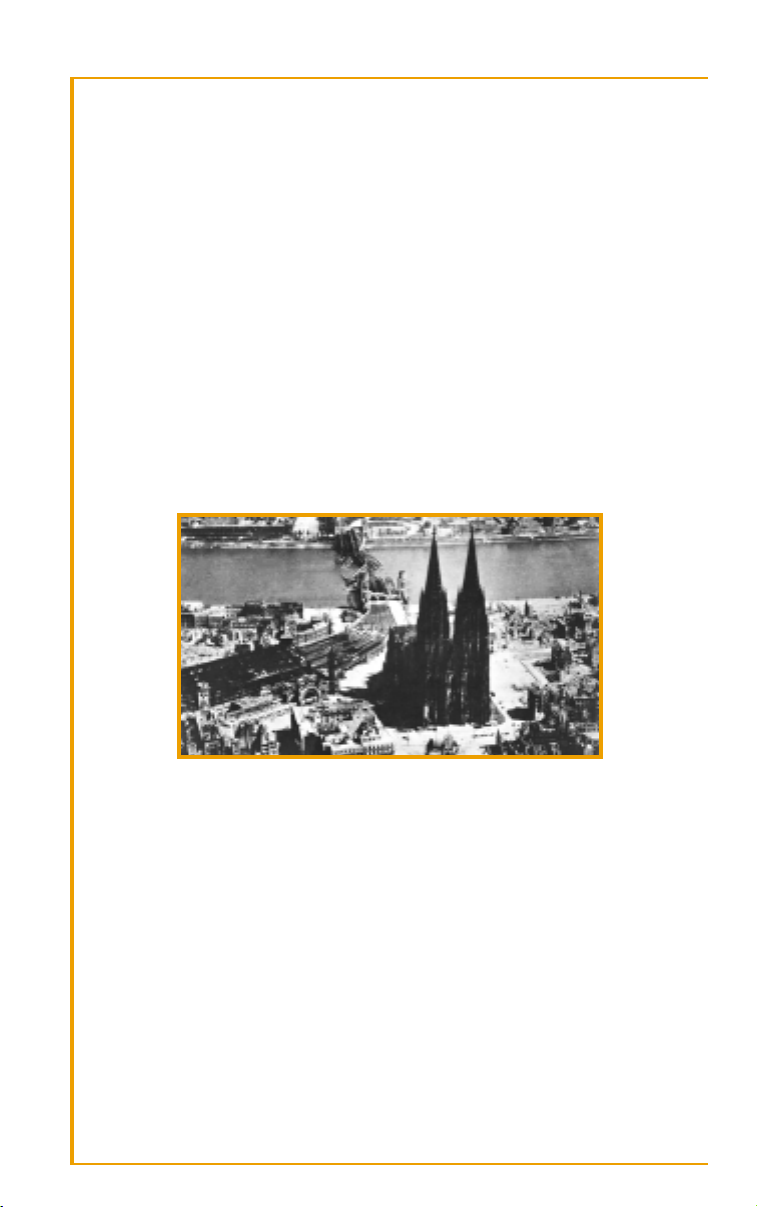

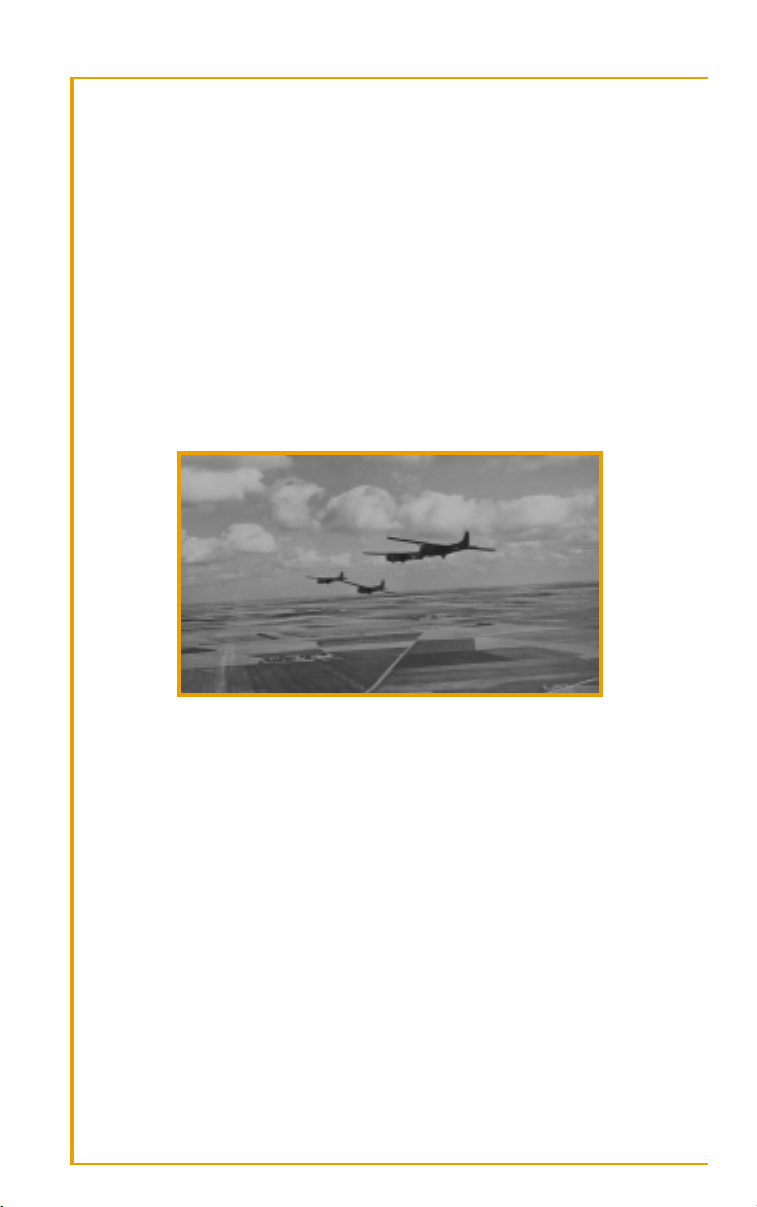

A vast Allied bomber armada heads for Hitler’s Reich.

As the Second World War progressed, the theories of Douhet and another

early champion of air combat potential, American William “Billy”

Mitchell, would be tested to their utmost. Some ideas proved accurate;

others had results far different than those envisioned. Douhet’s belief that

urban bombing would demoralize a nation proved quite incorrect when

Germany attempted to level British cities in the Battle of Britain. In fact, it

united the British people and hardened their resolve to see the war

through to its conclusion. Oddly enough, the British leadership failed to

learn its own lesson and followed the exhortations of another air power

devotee, Arthur “Bomber” Harris, perhaps the war’s most zealous advocate

of massive civilian bombing. He was convinced that the German people,

unlike his own island’s residents, would crumble and blame their leaders

for disaster if subjected to horrific raids. While the economic and strategic

results of the massive Allied bombing effort can be argued, the German

civilians, like their British counterparts, simply dug in and endured.

4

Page 4

AIR WAR IN WESTERN EUROPE

If civil collapse was not achieved, Britain alone could not accomplish the

other goals of large-scale bombing. It took the entry of the United States

into the war for the two nations to combine efforts and strategies and

impact the German military machine in a decisive manner. Britain favored

night time raids; America confidently chose daylight. Together this roundthe-clock bombing strategy aimed to pummel German industry into the

ground, and force the Luftwaffe into a defensive position, thus depriving

German forces on the front lines of air support.

A burden to bombing strategy was the distance which the planes had to

travel. Though equipped with some gun turrets, the bombers were easy

targets for fast-moving fighter planes which rose to meet the attack. For

raids along the nearby fringes of enemy territory, friendly fighters could fly

as escort to the larger planes and fly out to engage enemy fighters. As Allied

raids aimed deeper and deeper into German territory, however, the fuel

capacity of their fighters forced the tiny planes to turn back often well

before the bombers were over their prime targets. Left on their own, the

bomber losses were staggering. Champions of heavy bombing such as Harris and American General Carl Spaatz found themselves hard-pressed to

justify the losses against the questionable levels of damage inflicted to German military potential.

One result of the Allied bombing offensive that was an unqualified success

was its effect on the Luftwaffe. At a time when the tides of battle were turning against Germany, an air force designed for offense and ground support

in the field of battle was instead forced to stay on home turf and defend

industry and urban sites against an ever-growing enemy swarm. The

attrition rate for Allied flyers was horrifying, but the sheer manpower

available to the Allies meant losses could be replaced. Germany’s losses

were crippling. Skilled pilots were replaced by men who, due to time

constraints and scarcity of fuel, had little training. No matter what

“miracle weapons” Hitler’s weaponers might design, the skills of those

flying them ensured the impact of those wonders would be minimal.

AIR WAR: 1943–44

All across the western front in 1943, air power was playing a critical role.

The early mistake Hermann Goering, architect of German air power, made

in emphasizing smaller bombers for troop support was now apparent as

the four-engine long range bombers of the Allies roared over Germany. At

the war’s start, it was the Luftwaffe inspiring terror while screaming over

foreign skies. Now, over its own territory, Goering’s air force fought a desperate battle with an enemy growing in strength and confidence.

5

Page 5

WORLD WAR II FIGHTERS

In late 1942, the Allies escalated saturation bombing to round-the-clock

bombing. The British would fly over German cities by night and do their

best to utterly destroy them. By day, American bombers would attempt to

pinpoint more strategic targets and cripple German industry. American

faith in its bombing sights was misplaced, however: the height their planes

had to fly to avoid anti-aircraft artillery often negated any accuracy those

sights might provide. Bombs often fell miles from their target.

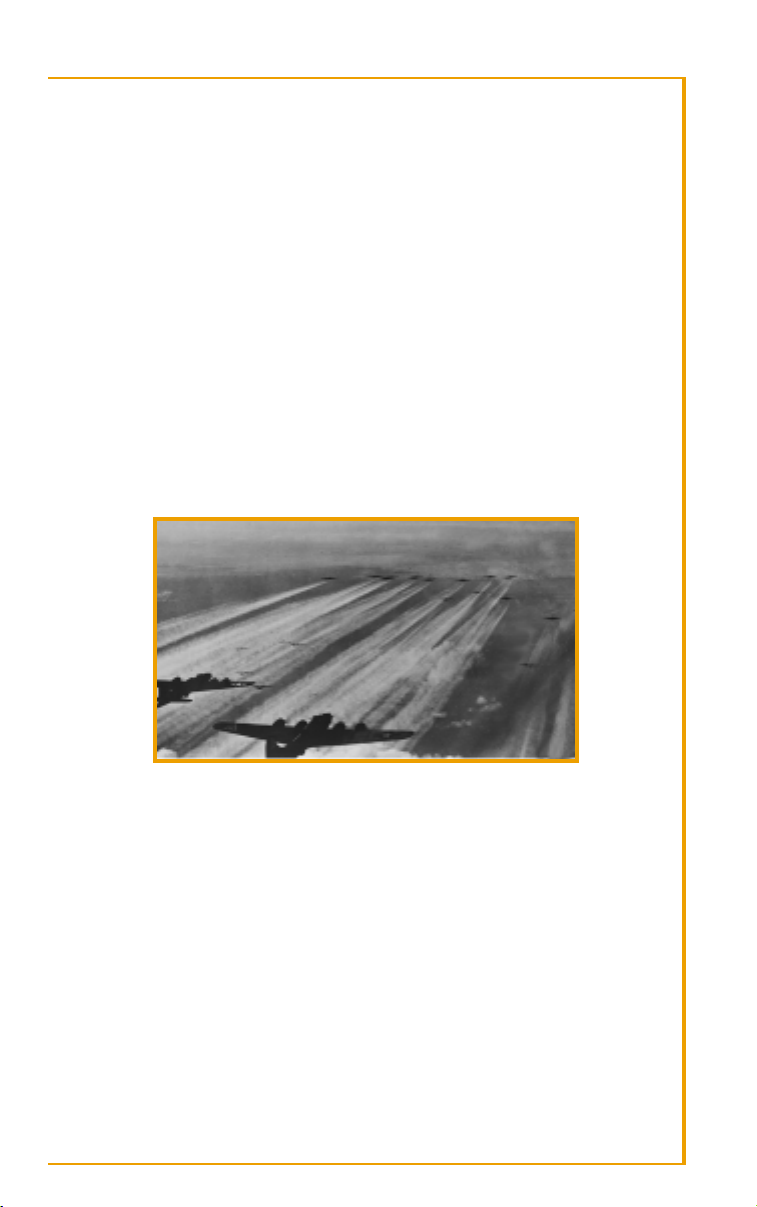

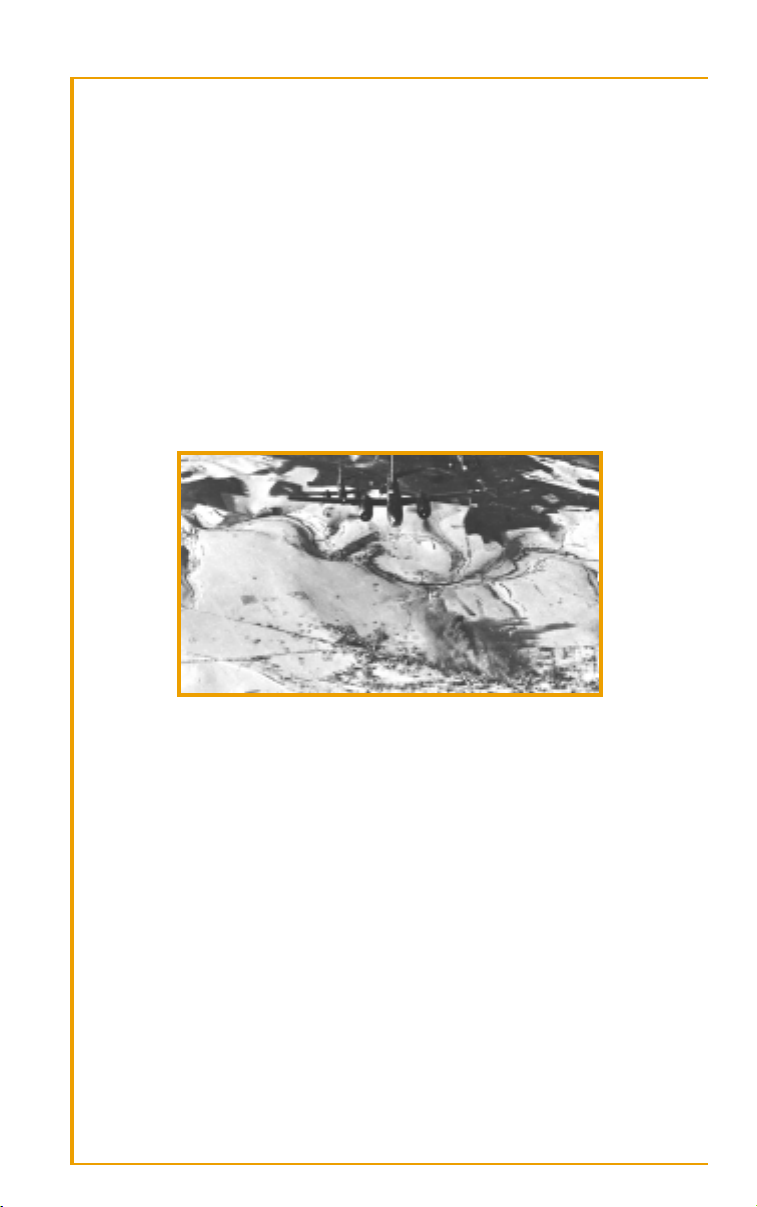

An American Liberator succumbs to German air defenses.

In summer 1943 the Allies bombed Hamburg for four consecutive nights,

taking 40,000 lives and creating a huge firestorm. The citizens—those who

survived—were stunned and numbed, but did not turn on their leaders. In

August, American planes from Libyan bases reached Ploesti, Romania’s

huge oil facility. As they flew over the Balkans, wave after wave of Luftwaffe fighters rose and hammered them. A quarter of the men on the mission died. Slightly more than one-sixth of the planes survived or were able

to be flown again. The facilities were soon repaired and operational.

For both sides, losses were terrible. The Luftwaffe were losing pilots at a

speed too great to replace. By late 1943, most planes rising to meet the

huge fleets of Allied bombers with their swarms of fighter support were

piloted by men with much less training, let alone battle experience. As for

the Allies, their fighter planes could not make the longer journeys to support the bombers. As better fighters were built and their range increased,

more German targets could be reached, but at a certain point, they had to

turn back—and then the Luftwaffe and its speedy planes could tear the

bombers to pieces. It would not be until 1944 that additional gas tanks

called ‘drop tanks’ would enable Allied fighters such as the P-51 Mustang

to penetrate deep into Nazi territory and destroy the Luftwaffe.

Equally dreaded was the 88 mm antiaircraft gun. Closely concentrated,

dug in near vital industrial areas and other targets sure to attract Allied air

raids, Flak guns may have taken out more bombers than the Luftwaffe

throughout the course of the war.

6

Page 6

AIR WAR IN WESTERN EUROPE

Amazingly, though fuel and pilots were scarce, fighter production continued

to rise in Germany. Hitler’s new minister of production, Albert Speer, had

reorganized the economy and cut as best he could through the multiple

layers of squabbling bureaucracies to actually increase all-around military

production. This in the face of round-the-clock bombing raises questions

as to the strategic, as opposed to propagandistic, value of the constant raids.

One definite result of round-the-clock bombing was that the Luftwaffe was

being slowly bled dry. While not destroying German industry, the bombing strategy had pinned Goering’s forces down on the home front. While

more planes were being built, they couldn’t keep pace with the losses

sustained against the Allies. Hitler began putting more and more hope—

and more and more resources—into a host of experimental weapons he

believed would turn the tide again to his favor. Goering, desperate to

regain favor, encouraged his Führer in those dreams. And in the East, the

loss of air support to defense over Germany left the Wehrmacht open to

the grinding, inexorable advance of the Red Army.

COUNTDOWN TO INVASION

By now the path of the war had become plain, like a hideous ballet whose

choreography had been planned and now must be followed through. German High Command knew that eventually the Western Allies were going

to strike across the English Channel and fortifications were accordingly

built. Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel, considered one of Germany’s

best generals, was brought north from overseeing the occupation of what

was left of Mussolini’s regime to supervise the anticipated defense of the

beaches. He immediately began construction of an elaborate series of

defenses. If invasion came, he thought, and the Allies could be repelled on

the beaches, it would be years before they could muster another assault.

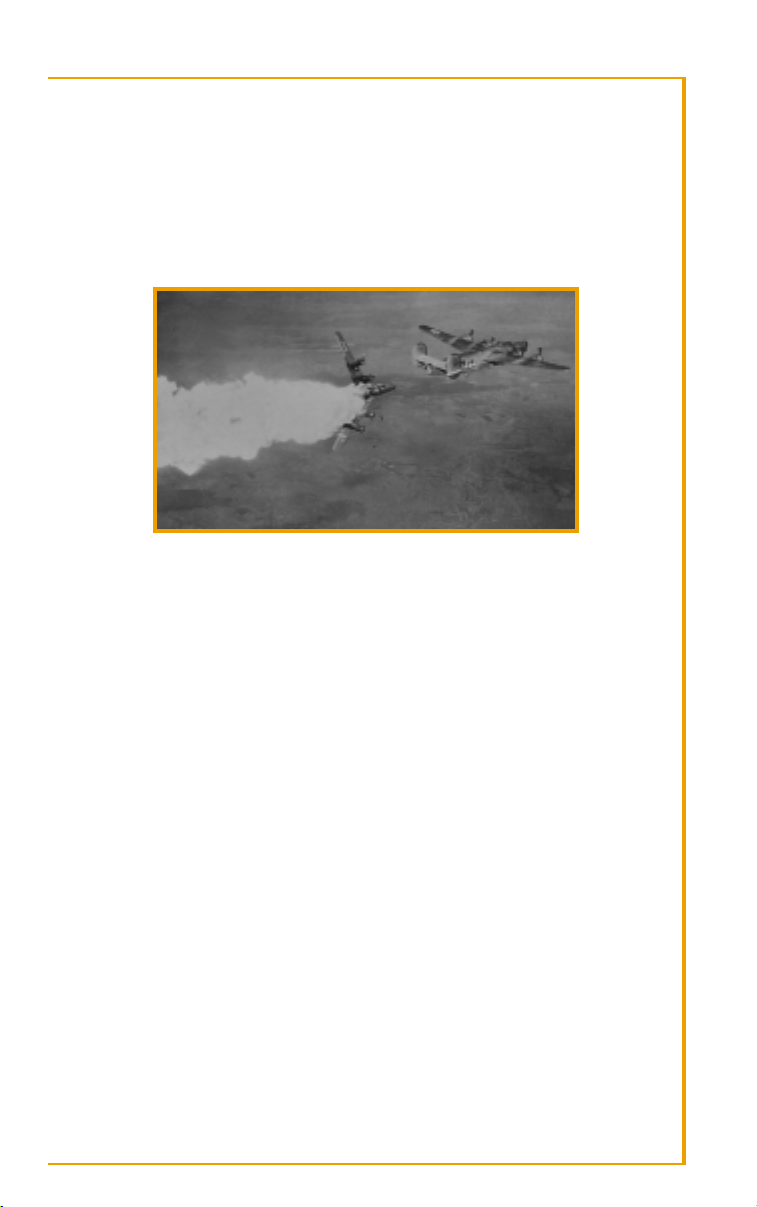

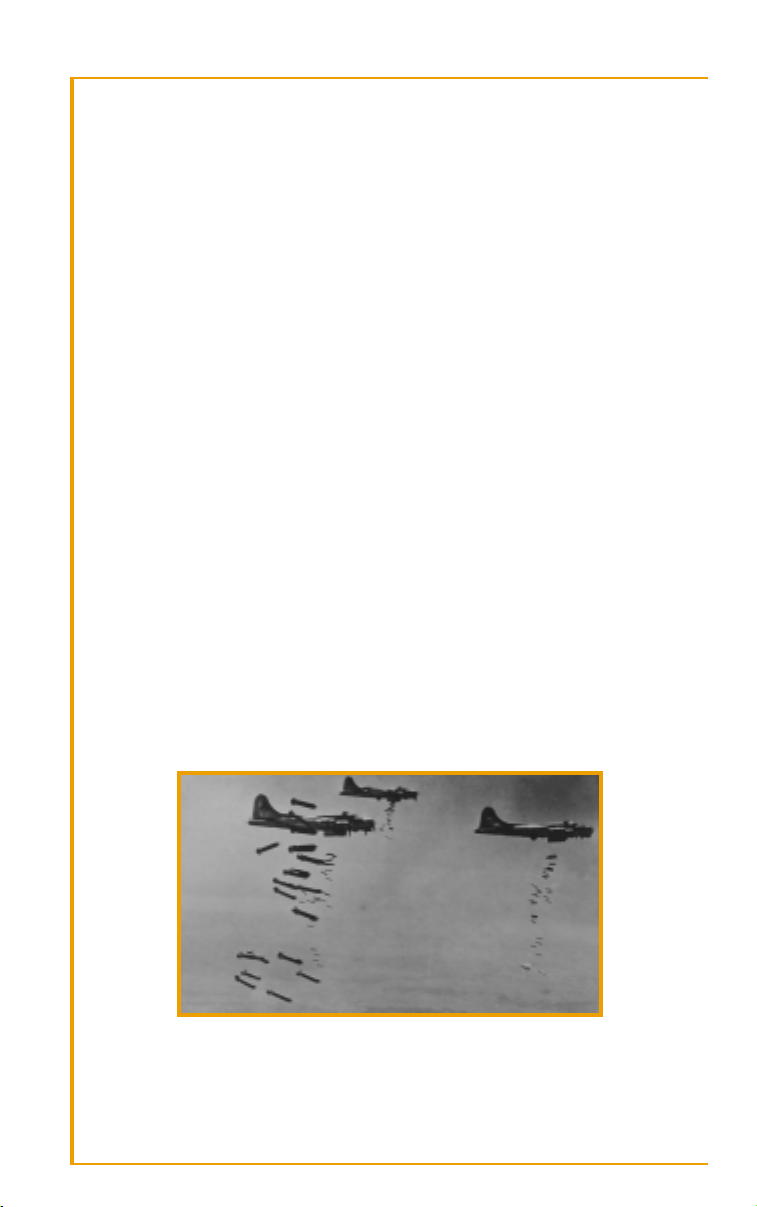

B-17s unload their “sticks” on the target.

7

Page 7

WORLD WAR II FIGHTERS

Hitler too hoped for a decisive blow on the beaches. In the face of the

crushing defeats being dealt the Wehrmacht in the East, he was still

convinced he could triumph over his enemies. He moved many of his best

divisions to France and the Low Countries to wait for the invaders and

smash them on the beaches. From there, holding them in the Italian

bottleneck would be easy. Full force could be concentrated on the Soviets,

who would then crumble. Hitler could then choose the time and place for

his victorious attack against the West.

Unfortunately for the Führer, his visions of destiny combined poorly with

faulty Nazi intelligence gathering. Allied diversions led German High

Command to grossly overestimate the size of the invasion force gathering

in England. Thus, more German divisions were held down in France, just

as the Red Army was hitting high gear in its most brutal offensives yet. Further Allied deception tricked Rommel into positioning most of the finest

armor and best troops far away from the actual landing point. As newlyappointed Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower polished

plans for a Normandy landing, the best Germany could throw against an

attacker was waiting to the east, convinced the Allies would make a straight

line from Dover to Pas de Calais. Any landings to the west, thought Rommel, were diversionary attacks to be disregarded and dealt with later.

Meanwhile, Allied round-the-clock bombing continued its relentless pounding of the German landscape. The Luftwaffe was slowly being whittled away.

Though Albert Speer was achieving sinister miracles in keeping armaments

production high, damage to transportation infrastructure and the massive

consumption of fuel by units engaged to the south and east meant that

poorly trained pilots were rising to meet Allied flyers. The few skilled German pilots left were busy testing the secret weapons Hitler was always

boasting of, the weapons that in his wild inner world would turn the tide

of war. Allied bombs had hindered development of his V-2, the world’s first

rocket weapon, with which he hoped to bring the Blitz back to London.

With their debut put off by a year, the Führer instead demanded a renewed

conventional bombing assault on England at the start of 1944. The Luftwaffe

thus squandered precious planes on a futile “Baby Blitz”, as Londoners

called it. Until May 1944, a force of 500 bombers inflicted minimal damage

as Allied air defenses blasted more than half of them out of the sky.

In the East, the Red Army continued slowly steamrolling over the

Wehrmacht. Their 1943–44 winter offensive gave the Germans no rest. By

spring 1944, Germany was in full retreat in the East. The Soviets had their

choice of where to strike first. Reinforcements poured into the Red Army;

its Ural industrial base, untouched by Axis assault, sent a steady stream of

weaponry toward the front. The Germans in the East, on the other hand,

were increasingly desperate. Reinforcements and new weaponry were

being sent westward, to guard the beaches of France. Partisans roamed

behind the lines freely, pinning down Nazi troops, destroying supply lines

8

Page 8

AIR WAR IN WESTERN EUROPE

and communications. Years of slaughtering Soviet officers and starving

prisoners of war had made their enemy a merciless, furious foe. No German wanted to be taken prisoner by the Red Army. It was a virtual death

sentence.

In Italy, the first of the Axis nations to be invaded, the Allies saw a much

slower advance. Given terrain, climate, and the proximity to the Reich

itself, the German defense was more tenacious, despite the Italian populace’s

eager embrace of the Allied assault. The fighting was slow, torturous, and

bloody, with only more devastation likely as the Allies would slug their

way up the narrow peninsula. But as Italy and her liberators looked ahead,

the only thing that could shorten the bloodshed was on the horizon: the

attack from the west. The time had come at last for D-Day.

D-DAY

Gliders carrying troops into Normandy.

Operation Overlord, the largest amphibious assault ever undertaken,

began on June 5, 1944, during a break in an unexpected storm which nearly forced Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower to call off the

invasion. Due to amazingly successful Allied deception as well as the

bureaucratic stupidities and inept intelligence-gathering of the Germans,

the landings were a surprise.

Massive air power had been called in. For weeks, bombing runs had been

softening up the coastal defenses, and surveillance flights had pinpointed

the major installations. Even Arthur “Bomber” Harris put aside his usual

obsession with terror bombing and committed his forces to aiding the

invasion, devastating the rail lines and infrastructure Germany needed if it

was to respond quickly to the assault. Allied fighters and bombers ruled the

skies: the Luftwaffe’s ill-advised “Baby Blitz” had left it even weaker than

it already was, and the landing sites were all within range of fighters based

in England.

9

Page 9

WORLD WAR II FIGHTERS

The Germans were taken in by almost every Allied diversion. Dummy

parachutists convinced Rommel that his instincts were correct: the forces

landing at Normandy were simply a diversionary attack. He refused to be

fooled; his main forces, including prized panzer divisions which might

have blown the landing troops to pieces, remained to the east, and would

stay there for crucial days to come. Surely the main landing would come

at one of the strategic harbors the Germans held, and had built impenetrable defenses around. What Rommel didn’t know was that the Allies had

built two floating harbors of their own, and that these huge devices were

on their way across the channel.

American Thunderbolts meet French livestock on a temporary runway.

The key to victory was landing as many forces as fast as possible, and the

Allies succeeded brilliantly. Before the Germans realized the main invasion

really was happening and could get reinforcements to contain the beachheads, the floating harbors had unloaded artillery, armor, and thousands

of men. Even a terrific storm’s destruction of one of the artificial harbors

on June 19 couldn’t help the Germans. The first day’s hesitations cost

them the battle. Their numerical superiority in troops and armor was too

slowly deployed, and their air defenses had been shattered by wave after

wave of Allied planes.

Still, the destruction was terrible. The defenders gave ground grudgingly,

fighting field by field, inflicting heavy losses on Americans in the west and

the British further east. But after bitter initial fighting, by the 14th the

Americans, under the colorful General George Patton, had broken through

German lines and drove toward Cherbourg, which fell on the 26th. The

Allies now had a true harbor through which they could pour weaponry

and supplies. The Nazis had done their best to destroy the city and its harbor, but within three weeks Cherbourg was beginning to unload further

invasion forces.

10

Page 10

AIR WAR IN WESTERN EUROPE

The Allies had firmly established themselves on the continent, though

progress was slower than initially anticipated. Field Marshal Bernard

Montgomery, the hero of El Alamein, the crucial battle which turned the

tide against Germany in North Africa, was unwilling to take the heavy losses a major British push would entail. The Americans to the west found

themselves in terrain which hindered the advance of their heavy armor.

Once they attached gigantic spikes to the front of their tanks, however,

they could go off road again, punching through the hedgerows of northern France and into the face of the ferociously-resisting Germans.

As American armor hammered in the west, to their east, Nazi armor was

doing its best to push the British back to the beaches. But from the air

came swarms of Allied fighters and bombers, pinning the tanks in their

positions, making movement slow and deadly. Round-the-clock air attacks

from Allied planes and futile offensives had left the Luftwaffe, in the hour

it was most needed, outnumbered and outgunned.

From Berlin, Hitler made a confusing situation worse, issuing contradictory orders, berating, ignoring, and overruling his generals. He refused calls

for a counterattack against the menacing American armor which threatened to buckle the entire defensive line in France. He didn’t want to risk

the army; instead it began to be whittled and chipped away as it was slowly pushed back, with no reserves to replace the losses.

Meanwhile, his fervent belief in his secret weapons program finally bore

fruit in mid-June. The first V-1’s, pilotless jet planes loaded with explosives,

began falling on London. Although the appearance of these odd bombs

were a blow to British morale—Churchill even demanded retaliatory poison gas attacks, but was overruled by the Americans—actual damage was

nowhere near as great as Hitler envisioned. The V-1’s were easily shot

down, and many others missed their London target. Panic did not set in;

London was not evacuated; the Allied war effort continued unhindered.

Once again Douhet’s predictions failed to come true. The weapons

designed to suddenly win the war only hurried the Allies to break out of

the Normandy beach heads to reach the V-1 launch sites.

Nazi generals finally got the hint that Normandy was, indeed, the big landing by late July and began moving their long-sidelined armor from Pas de

Calais to intercept American tanks. By then the difficult terrain was behind

Patton’s forces, however, and open country well-suited for armor was now

before the audacious general. Hitler finally agreed to a counterattack at

Mortain, and issued orders to strike—orders which were intercepted and

decoded by the Allies, who had broken almost all the German codes and

knew exactly when and where the attack was to come. Allied air power,

combined effectively with the ground troops, stopped the assault in its

tracks. As the Americans pummeled their attackers, the British and Canadians previously pinned down by those German troops moved south. Had

Montgomery not once again been too cautious and held back his best

11

Page 11

WORLD WAR II FIGHTERS

troops, the Germans would have been trapped and annihilated in another

Stalingrad. As it was, many of them escaped, although with huge losses in

life and equipment. By late August, the British were clearing Belgium and

capturing the V-1 launch sites, and to the south, defying Hitler’s orders to

level the city, Gen. von Choltitz pulled out of Paris. On August 25, advancing American troops held back and let Charles de Gaulle’s Free French

forces liberate their long-suffering capital. Ten days earlier, more Allied

troops had struck from the south, landing on the French Mediterranean

coast. Churchill had heatedly opposed this operation, pushing instead for

continued pressure in Italy. Given the choice of advancing slowly to an

Alps range filled with Nazis armed to the teeth or seizing the ports of Marseilles and Toulon, Eisenhower understandably overruled the British prime

minister’s strategy.

The German lines were crumbling. From the Low Countries to the Swiss

frontier, Allied troops were racing toward the borders of the Reich. Hitler

grudgingly allowed the troops in the south of France to pull back and

avoid encirclement. Almost all of France had been taken in two months’

fighting. With the Nazi armies went the wartime French government based

in Vichy. Coming to power through French defeat, they now faced disaster of their own as France was freed, having tied themselves to the fate of

their conquerors. From southwest Germany, they watched as the Wehrmacht abandoned France and regrouped along the border, holding as many

Low Country ports as it could.

That holding of ports became ever more troublesome for the Allies as 1944

progressed. While Cherbourg was slowly being cleared, other liberated

ports such as Brest had been so badly wrecked by the retreating Germans

that they were unusable. As Germany’s supply lines shortened, lessening

the strain on its battered infrastructure, the Allied lines stretched forward,

with huge levels of troops, planes, tanks, and artillery to maintain. The

damage they had done to infrastructure to cripple Nazi supply lines now

haunted them. The only thing that helped them get as far as they did

before supply became a major issue was the valiant drivers of a massive

convoy of trucks laden with fuel and weapons which came to be called the

Red Ball Express. A round-the-clock substitute for the ruined rails ran nearly 90,000 tons of supplies from the landing beaches of Normandy deep

into France in the space of a few weeks.

By the time the Allies were closing in on the Reich, even that fuel was running low. Patton and Montgomery bickered over who should get the last

fuel reserves and push ahead. Eisenhower sided with the difficult British

general, who planned to force his way across the Rhine into Holland,

allowing the Allies to exploit the great harbor of Antwerp, which the

British had seized virtually intact. Montgomery swung from his usual toocautious approach to overconfidence. Ignoring warnings of strong German

armor nearby, he ordered a parachute brigade dropped behind enemy

12

Page 12

AIR WAR IN WESTERN EUROPE

lines—and on the other side of town from the Arnhem bridge the paratroopers were to seize. The Germans cut them off, drove them away from

the bridge, and shot them to pieces. Only a fifth of them survived to

become prisoners or escape back across the Rhine.

Surprised by the stiffening German resistance, stunned by Montgomery’s

defeat, and above all, desperately low on fuel, the Allied advance slowed as

autumn progressed. Eisenhower had hoped for an end to war in Europe by

autumn; an obstinate Reich had held out. The Allies would have to wait

until spring—winter was coming, and conditions would be too poor for

any major offensive on the Western front. Eisenhower’s only solace was

that, given the weather and the continuous beating Germany was taking

in the East, at least Hitler couldn’t launch any counterattacks either.

THE ARDENNES OFFENSIVE

Allied medium bombers over “The Bulge.”

Hitler counterattacked on December 16, 1944, stunning the Allies by sending forth troops and armor under cover of fog and cold. Now, with the

Eastern front in collapse and his final attempts at terror bombing London

out of the war proven futile, he decided on a final, furious offensive that

might change the course of the war.

While on the Eastern front the amount of territory between Germany and

the Soviets was ample, in the West the front was uncomfortably close to

the Reich’s industrial base. While there might be time to stall and regroup

against the Soviets, there was little time to waste before the Allies would be

in the vital Ruhr region. Thus, as entire armies were being annihilated on

the Polish frontier, Hitler massed more than twenty divisions of new

troops and equipment in the West, augmenting it with the last reserves of

manpower he could find within the Reich. Total mobilization had finally

been declared by Speer. Now 16-year-old boys sat in the cockpits of the

Luftwaffe’s fighters and filled the ranks of German rifle companies.

13

Page 13

WORLD WAR II FIGHTERS

Hitler planned to deliver a stunning, crushing blow, pushing the Allies

across the Channel in a second Dunkirk. This new Blitzkrieg would

undoubtedly be so successful that it would end in time to switch the forces

back to the East before the Soviet winter offensive would begin. Hitler’s

estimation of the Allies, especially the Americans who now made up the

bulk of the force in the West, was that they were a weak-willed assembly,

ready to crack with the first serious defeat. For the third time in less than

fifty years, Germany planned a sudden attack through the Low Countries.

Allied intelligence summed up the Wehrmacht as a spent force, unable to

muster anything beyond a tenacious but doomed defense. Over the skies

of Germany, Allied bombers flew virtually unopposed, pulverizing cities

with impunity. The vast resources of Ukraine and Romania were in Soviet

hands; only the oil fields of Hungary remained for Hitler to draw upon.

The Allied lines were drawn thin across the Ardennes forest, but could

hold firm until supplies arrived and a spring offensive could begin.

It was with this mutual underestimation that the last Nazi offensive began.

In cold and snow, through the heavy woods of Luxembourg and Belgium,

a 400,000 man German force slammed into a front guarded by 80,000

Americans who were outnumbered in tanks and (by a more than four-toone ratio) artillery. In the long-gone days of 1940, the attack would have

waited for a clear day, so that the mighty Luftwaffe could first bludgeon

the enemy from the air. In 1944, the Germans instead counted on poor

weather to keep the Allied air forces’ far superior strength on the ground.

American ground crewmen prepare a holiday gift for the enemy.

The Americans were caught totally off-guard. Eisenhower scrambled to move

forces to the Ardennes as two divisions were destroyed and others were

pushed back toward the strategic town of Bastogne. A division of US paratroopers secured the town just in time; the Germans surrounded it but

failed to take it. This slowed the advance toward the Meuse River, giving

American armor time to regroup and stop the attack on the water’s east side.

14

Page 14

AIR WAR IN WESTERN EUROPE

To the south sat the American 3rd Army. Patton had been waiting for the

fuel to take his attack east into Germany. When the sudden offensive

began, Allied command was alarmed at the sparse defenses in the German

path, and the time it would take distant reinforcements to arrive. To everyone’s astonishment, Patton promised them he could disengage in the Saar,

change direction, and swing north to relieve Bastogne in 48 hours. To

everyone’s further astonishment, he did just that, not only getting his

forces to the front but hurling them into combat against the German

armor besieging the city. He smashed his way through in the face of brutal

panzer counterattacks, breaking the iron ring around Bastogne and freeing

the pinned 101st Airborne Division.

Despite the help Montgomery’s timidity gave them, the Germans’ bout of

good luck came to an end on Christmas Eve 1944, when the bad weather

which kept the Allied air forces grounded gave way. In the cold, clear skies

over the Ardennes, over 3,000 planes took to the air, and aimed for the

slowly stalling German advance. To the east, the Luftwaffe had orders to

attempt yet another air offensive against the enemy. Untrained pilots with

little ammunition and less fuel climbed into what was left of the Luftwaffe

with visions of chasing the Allied planes (by now outnumbering them

ten-to-one) from the sky.

So the Allies and Nazi Germany found themselves, on the Western Front,

in desperate battle. Hitler was flinging his last reserves in a final assault,

convinced he could sweep his enemies into the Atlantic and buy time to

win in the East. Both sides prepared to throw all they had into this showdown for control of the war’s direction, and perhaps its outcome. At the

end of 1944, the future of the planet was being decided on the ground and

in the skies above the dense forests of the Ardennes. The West had to get

reinforcements to the lines before they were overwhelmed, and hope for

the weather to clear so their superior air power could be deployed.

15

Page 15

WORLD WAR II FIGHTERS

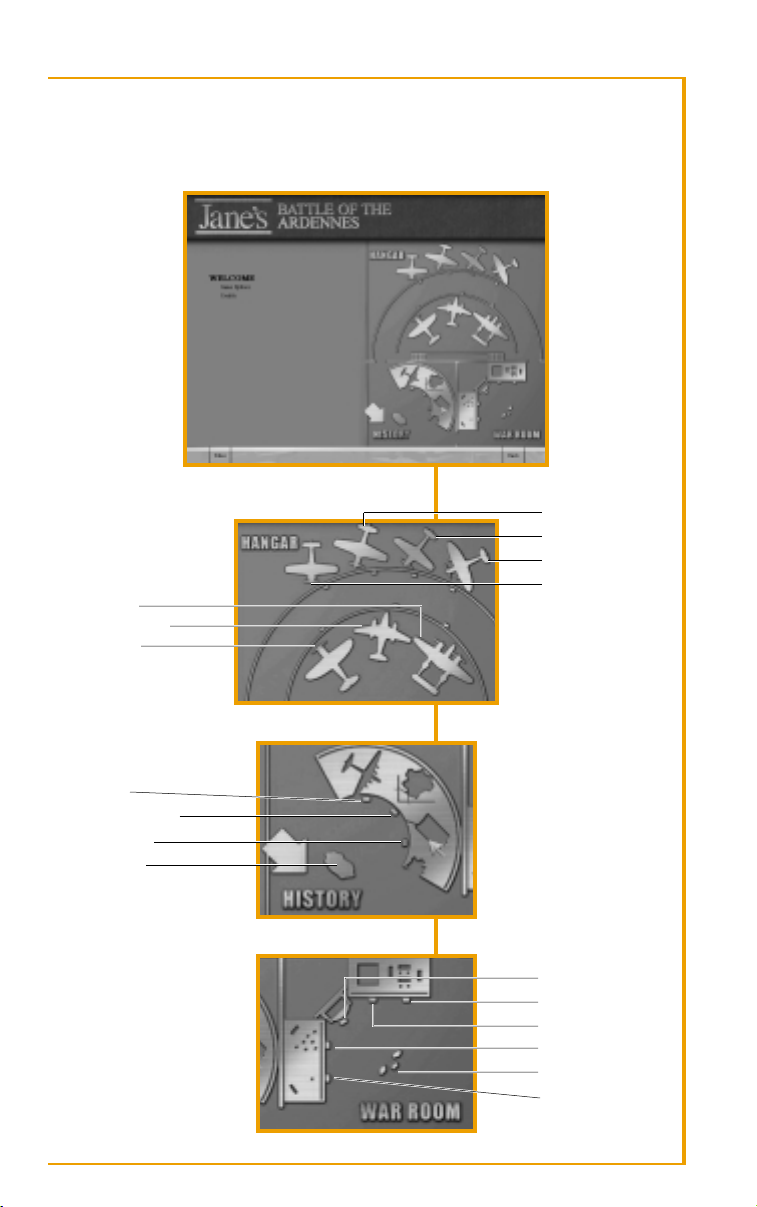

MUSEUM MAP

P-38J

ME 262A-1A

P-47D

P-51D

BF 109G-6

SPITFIRE F. IX

FW 190A-8

AIR FORCES

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

GROUND FORCES

WELCOME DESK

16

MULTIPLAYER

QUICK MISSION

MISSION BUILDER

CAMPAIGN

ACES

SINGLE MISSION

Page 16

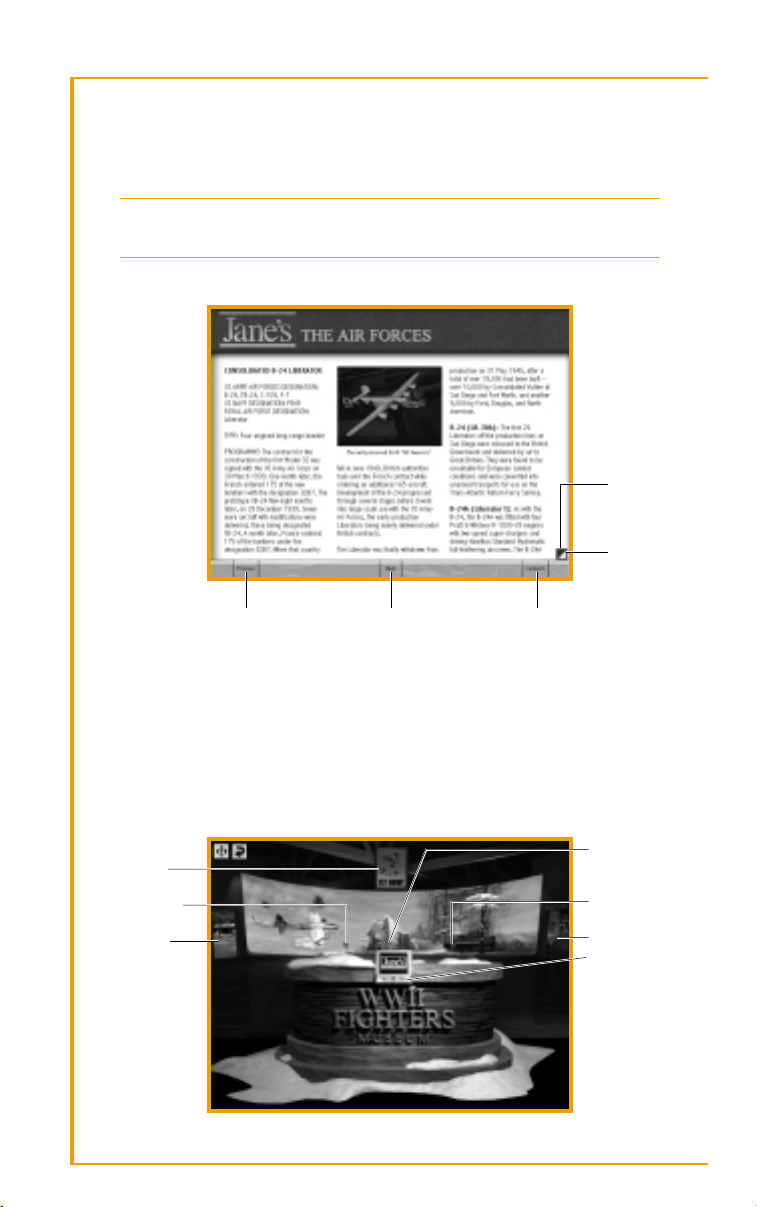

THE EXHIBITIONS

THE EXHIBITIONS

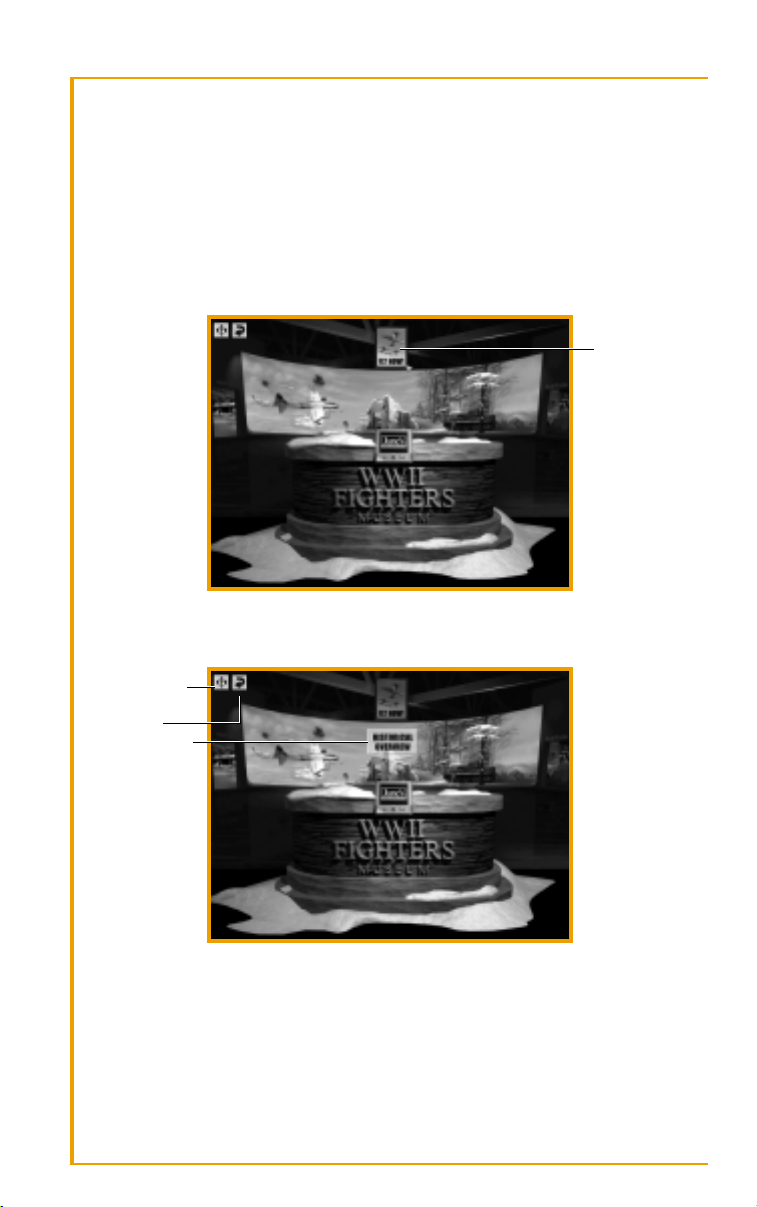

Upon entering the museum, you see the Welcome Kiosk. If you want to

jump right into flight, click the Fly Now! poster hanging in the top center

of the screen. You immediately begin a quick mission without configuring

your flight.

JUMP DIRECTLY

INTO A MISSION

NAVIGATING THE MUSEUM

QUICK NAVIGATION

BUTTON

BACK BUTTON

CLICK ON AN ACTIVE

LABEL TO MOVE

FORWARD

To go to the previous screen, left-click the BACK button in the top left

corner of the screen.

Use the QUICK NAVIGATION button to jump to another part of the

museum. Click to bring up a screen listing the various locations in the

museum. Select a location to be instantly transported there.

17

Page 17

WORLD WAR II FIGHTERS

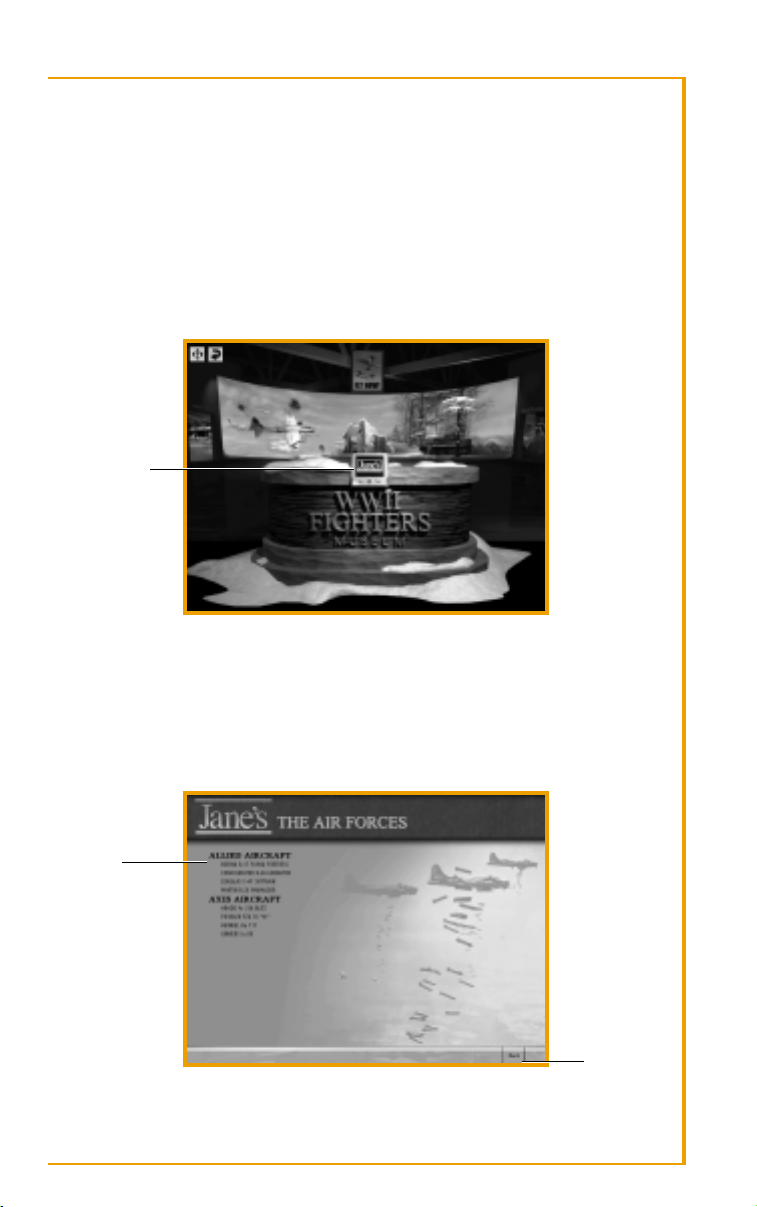

PANNING YOUR VIEW

At some locations, you may need to pan your view in order to see everything before you. To pan your view, move the mouse cursor to the left or

right side of the screen.

VIEWING KIOSKS

Each museum room has a number of kiosks. When you move the mouse over

a kiosk, it lights up. Click on a kiosk to view the content at that station.

CLICK ON KIOSK

TO VIEW CONTENT

The content you see on a kiosk monitor varies. Some kiosks display information on vehicles or historical subjects. Others select a mission.

INFORMATION KIOSKS

All Information Kiosks have a contents page. Here you choose the subject

about which you want to learn.

CONTENTS

BACK

18

Page 18

THE EXHIBITIONS

When you move your mouse over the contents page, the option under the

mouse turns white. Click to view detailed information on the subject.

Select the BACK button to exit the kiosk screen.

Video Button: Many kiosks have an additional Video button. Use

this to watch video reference material on the current subject.

Viewing Information

GO TO THE

PREVIOUS

PAGE OF

INFORMATION

GO TO THE

NEXT PAGE OF

INFORMATION

DISPLAY THE PREVIOUS

SUBJECT IN THE CONTENTS

DISPLAY THE NEXT

SUBJECT IN THE CONTENTS

RETURN TO THE

CONTENTS PAGE

Mission Kiosks

The Mission Kiosks are found only in the War Room. The controls in the

mission kiosks vary depending on the type of mission. See the Gameplay

Guide included in your Jane’s

®

WW II Fighters box for information on

selecting missions and building your own missions.

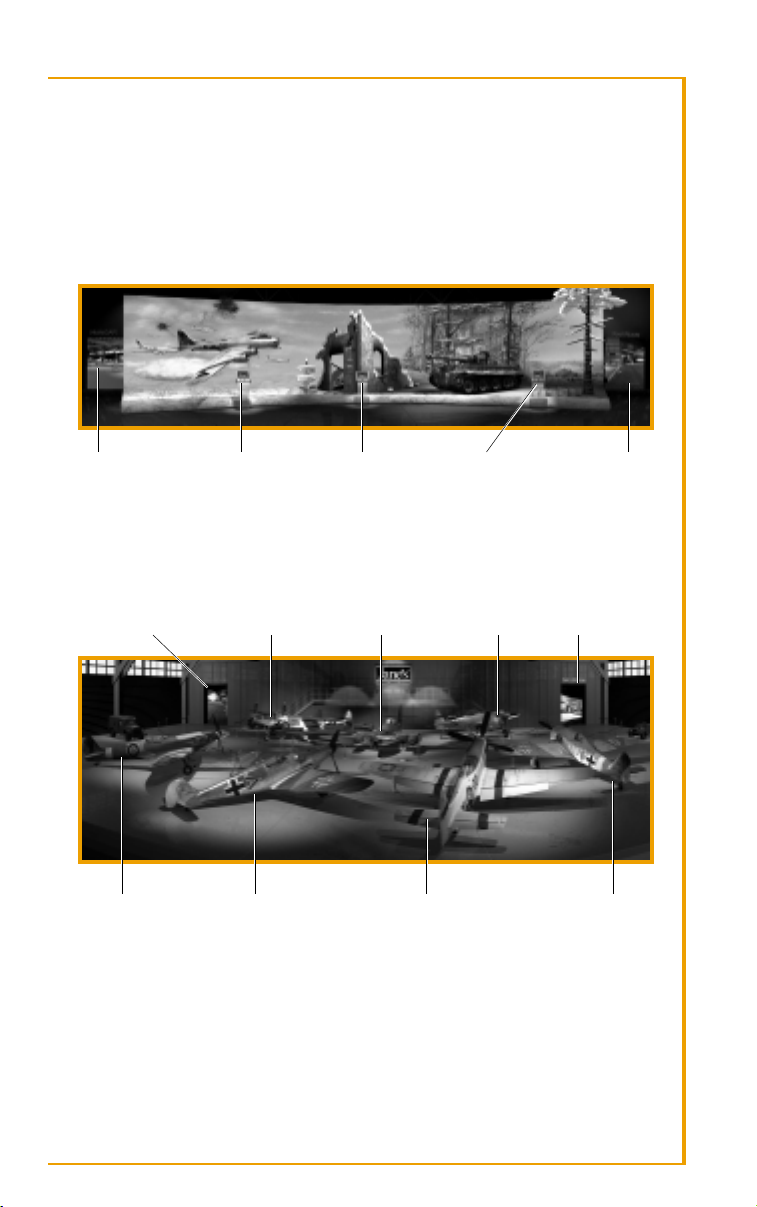

WELCOME DESK

JUMP DIRECTLY

INTO A MISSION

GO TO AIR FORCES

KIOSK

GO TO HANGAR

GO TO HISTORICAL

BACKGROUND

KIOSK

GO TO GROUND

FORCES KIOSK

GO TO WAR ROOM

SET GAME OPTIONS,

VIEW CREDITS, OR

WATCH THE GAME

INTRO ANIMATION

19

Page 19

WORLD WAR II FIGHTERS

INFO ROOM

In the Info Room, you can learn about bombers and other aircraft that

operated over Europe, as well as the types of ground vehicles and weapons

that operated on the Western Front in late 1944. Also, the Historical Background Kiosk provides you with information on the Ardennes Offensive,

known in the US as the Battle of the Bulge.

GO TO HANGAR VIEW INFORMATION

ON ALLIED AND

AXIS BOMBERS

AND TRANSPORTS

VIEW HISTORICAL

BACKGROUND ON

THE ARDENNES

OFFENSIVE

VIEW INFORMATION

ON ALLIED AND AXIS

GROUND VEHICLES

GO TO WAR ROOM

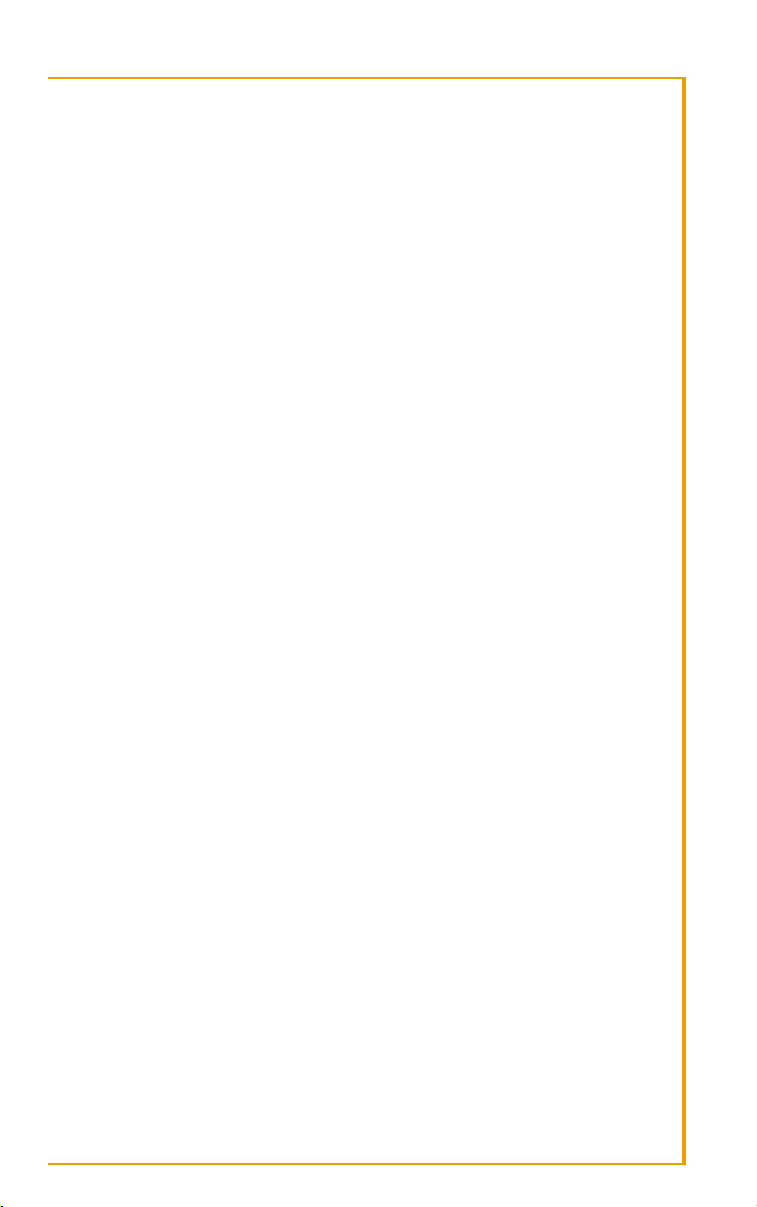

HANGAR

In the Hangar, you can learn about the museum’s featured aircraft.

GO TO P-38JGO TO INFO ROOM GO TO ME 262A–1A GO TO P-47D GO TO INFO ROOM

GO TO SPITFIRE F. IX GO TO BF 109G-6 GO TO P51D GO TO FW 190A-8

VIEWING THE AIRCRAFT

When viewing an airplane, you can go take a closer look at the cockpit,

armament, and powerplant. The curator provides commentary on each

aspect of the airplane.

20

Page 20

GO TO THE COCKPIT

THE EXHIBITIONS

GO TO THE

ARMAMENT

VIEW INFORMATION

ABOUT THE AIRPLANE

GO TO THE ENGINE

COMPARTMENT

Special Test Flight Buttons: Each of the Airplane Kiosks in the

Hangar has a Test Flight button. Click this to fly the airplane of your

choice in a non-hostile environment. Here you can test your flying

and gunnery skills.

WAR ROOM

In the War Room, you can select a single mission, build a custom mission

of your own, start or continue a campaign, or join a muliplayer game. In

addition, a special Aces Kiosk has video interviews with the aces who flew

the actual planes.

GO TO SINGLE MISSIONS KIOSK

GO TO CAMPAIGNS

KIOSK

GO TO MULTIPLAYER

KIOSK

GO TO MISSION

BUILDER KIOSK

GO TO QUICK MISSION KIOSK

SELECTING MISSIONS

The controls in the mission kiosks vary depending on the type of mission.

See the Gameplay Guide included in your Jane’s WW II Fighters box for

information on selecting missions and building your own missions.

21

Page 21

WORLD WAR II FIGHTERS

JANE’S®WW II FIGHTERS

Museum Collection

In the 1930s, the antiquated, wooden biplanes of WW I were replaced by

a new generation of sleek, metallic monoplanes that would redefine combat. Improvements in the engines, airframes, and firepower of these new

aircraft fostered the great race of the decade—which country could create

the fastest, most destructive flying machine in the world.

FOCKE-WULF FW 190A-8

Germany prepared for war with the expectation that mobile warfare and

combined arms would make any future conflict a brief if violent affair. It

was widely believed that a successor to the Luftwaffe’s frontline fighter, the

Messerschmitt Bf 109, would hardly be necessary in the age of Blitzkrieg

warfare. Thus it was with unusual foresight that the Reichsluftfahrtminis-

terium (RLM), or Air Transport Ministry, chose to fund the development of

an air superiority fighter in 1938, just as the Luftwaffe was standardizing

on Messerschmitt’s outstanding fighter. Who would have guessed then

that a particularly compact airplane—designed by Kurt Tank and his team

at Focke-Wulf—would become one of the most successful propeller-driven

fighters ever produced in great numbers?

Certainly the officials at the RLM did not expect much from Tank’s machine.

True, the airplane was small and sleek, with an attractively thin fuselage,

extremely low-drag profile, and excellent structure. But the fact that it was

built around a bulky radial engine instead of a narrow inline engine did

not bode well for its future. Three prototypes powered by 18-cylinder BMW

139 radial engines were ordered and built, the first flight occurring in early

June 1939. The engines were found to be wanting and were replaced by the

heavier but more powerful 1,192 kW (1,600 hp) BMW 801C. The added

weight forced some changes in the airframe, including moving the cockpit

further aft in order to shift the center of gravity; combined with a now

larger engine cowling, the pilot’s view was diminished slightly. The wing

was also lengthened, though this was more beneficial than detrimental.

Trials with pre-production aircraft revealed teething trouble with the airplane’s ten-blade cooling fan, but the overall impression of the fighter was

that it was a delight to fly. Orders were delivered for a hundred Fw 190A-1

aircraft armed with four 7.7 mm MG 17 machine guns—two in the cowling

and another pair in the wing roots—all firing through the propeller. To

increase firepower, 20 mm MG FF cannons were added to points outboard

of the landing gear. By the time the A-2 arrived, the wing root guns were

being replaced by the new 20 mm MG 151/20, necessitating the bulged

plates on the upper wing surfaces.

22

Page 22

MUSEUM COLLECTION

It was the Fw 190A-3 powered by the 1,268 kW (1,700 hp) BMW 801D-2

that became a menace to the RAF in the summer of 1942. Flying against

Spitfire Vs, the Fw 190s proved themselves in every category of performance save turning ability. Able to initiate or break off combat at will, the

Fw 190s dominated the skies over northwest Europe. The power of the new

fighter was such that the English would have to scramble to wrest air

superiority from a smaller Luftwaffe force facing them across the channel.

A number of Fw 190A sub-variants followed to fulfill an ever-widening

number of roles. Originally intended to be an air superiority fighter, the

Würger (“butcher bird”) quickly became a jack-of-all-trades, armed with

cameras for reconnaissance; external fuel tanks for long-range missions;

bombs for use as a fighter-bomber; tropical equipment for desert-fighting;

wing pods for use as a bomber-destroyer; additional armor for bomberramming; radar equipment for use as a night-fighter; bomb racks for

carrying torpedoes; and various combinations of the above.

As the war progressed, the Fw 190 assumed roles earlier held by such

esteemed German aircraft as the Ju 87 Stuka and other close support

aircraft. Beginning in late 1942, the heavily-armored Fw 190F—which also

featured an incredible number of sub-variants—was developed for use in

the ground attack role. This was followed by the 190G series, a close

support version with additional fuel for increased combat range.

As the radial engine Fw 190 was being perfected, Focke-Wulf simultaneously developed versions of the fighter (190B and C series) with inverted-V

liquid-cooled inline engines. The radial engine 190s performed poorly at

high-altitude, and as defense of the Reich took on importance, the need

for a heavily-armed high-altitude fighter became greater. The result was the

famous 190D or “Dora” series of fighters, which began to see service only

in late 1944. Powered by a 1,323 kW (1,776 hp) Junkers Jumo 213A-1

engine, the Fw 190D was considered on a competitive footing with the P51 or Spitfire IX.

In total, just over 20,000 Fw 190s of all types would be produced by war’s end.

FW 190A-8 DATA

Engines One 1,268 kw (1,700 hp) BMW 801D-2

Wing Span 10.5 m (34 ft 5.5 in)

Length 8.96 m (29 ft 4.75 in)

Max T-O Weight 4,900 kg (10,802 lb)

Max Level Speed 657 km/h (408 mph)

Range 800 km (497 mi)

Armament Two 12.7 mm machine guns, two 20 mm cannon,

and either two-four 20 mm or two 30 mm cannon

23

Page 23

WORLD WAR II FIGHTERS

FW 190A-8 COCKPIT

1 2

3

4 5 6 7

8

1. AMMUNITION COUNTER

2. RADIO DIRECTION FINDER

3. AIRSPEED INDICATOR

4. ARTIFICIAL HORIZON

5. RATE OF CLIMB INDICATOR

6. COMPASS

7. BOOST

10

14

11 12

8. ALTIMETER

9. TACHOMETER

10. FUEL AND LUBRICANT PRESSURE GAUGE

11. FUEL GAUGE

12. CLOCK

13. OXYGEN PRESSURE INDICATOR

14. ENGINE TEMPERATURE

9

13

FW 190A-8 GAME LOADOUTS

Clean Fuel Gun Pods Gun Pods 500 kg 250 kg

Primary Guns Type/Number 20 mm x 4 20 mm x 4 20 mm x 2 20 mm x 2 20 mm x 4 20 mm x 4

Location Wing/ Wing/ Wingroot Wingroot Wing/ Wing/

Wingroot Wingroot Wingroof Wingroof

Rounds/Gun 200 200 200 200 200 200

Secondary Guns Type/Number 13 mm x 2 13 mm x 2 13 mm x 2 13 mm x 2 13 mm x 2 13 mm x 2

Location Cowling Cowling Cowling Cowling Cowling Cowling

Rounds/Gun 475 475 475 475 475 475

Secondary Guns Type/Number – – 30 mm x 2 30 mm x 2 – –

Location – – Wing Pods Wing Pods – –

Rounds/Gun – – 55 55 – –

Bomb Load Type ––––500 kg250 kg

Location ––––Centerline Centerline

Number ––––1 1

Drop Tank Type – 300 ltr – 300 ltr – –

Location – Centerline – Centerline – –

Number – 1 – 1 – –

Fuel,

24

Page 24

MUSEUM COLLECTION

LOCKHEED P-38 LIGHTNING

Developed before the war for use as a long-range, high-altitude fighter, the

P-38 took on a wide variety of additional combat roles, including escort,

fighter-bomber, photo-reconnaissance, torpedo-bomber, light transport,

and even an airborne ambulance. The adaptable Lightning served until the

end of the war—the only fighter to precede the war and remain in production until Japan surrendered. With its unusual twin-engine twin-boom

design, it was certainly the most recognizable airplane in the entire Allied

inventory—the Germans called it der Gabelschwanz Teufel or “the ForkTailed Devil”, while the Japanese term translated as “one pilot, two fighters.”

The P-38 was a credit to Lockheed, who in the early ’30s had never developed a purely military airplane. It was designed to meet a 1936 US Army

Air Corps specification for a pursuit fighter capable of 360 mph (576 km/h)

at 20,000 ft (6,100 m). A proposal was accepted the following year, and the

prototype XP-38 flew for the first time on 27 January 1939. In many respects

it was a truly revolutionary airplane. At the time of its introduction, it was

the fastest fighter in the world, and it also had the longest range. It had an

all-metal flush-riveted skin and turbo-supercharger for solid high-altitude

performance. And it was the first fighter to employ a tricycle landing gear.

The USAAC was pleased enough to issue a Limited Procurement order for

13 YP-38 fighters. These were fitted with two 1,150 hp (858 kW) Allison

V-1710-27/29 engines and carried a powerful array of guns in the nose: one

37 mm cannon, two .30 caliber machine guns, and two .50 caliber

machine guns.

An additional thirty production fighters designated P-38 were delivered in

July 1941. The .30 caliber guns were replaced by additional .50 caliber

guns, and pilot armor was added. These aircraft were turned over to training duties when the first combat-ready version, the P-38D, arrived in

August 1941. This version featured self-sealing fuel tanks as well as a redistribution of the elevator balance weights, which improved dive recovery

and eliminated problems associated with tail-buffeting.

The P-38E introduced what would become the fighter’s standard gun armament: four .50 caliber machine guns in the nose forming an arc over one

20 mm cannon. This was followed by the P-38F, which was fitted with two

1,325 hp (988 kW) V-1710-49/53 engines and underwing racks for up to two

1,000 lb bombs or long-range drop tanks. The latter increased the airplane’s

combat range to an astonishing 1,750 miles (2,816 km).

The P-38G and H each saw increases in engine performance. The P-38J,

which entered service in August 1943, was powered by two 1,425 hp

(1,063 kW) V-1710-89/91 engines and introduced powered ailerons and a

better cooling system. This was followed by the P-38L, the most numerous

version built and the first to carry underwing rockets. Some P-38Js and Ls

25

Page 25

WORLD WAR II FIGHTERS

were later adapted as pathfinders, complete with a bombardier and Norden

bombsight in a transparent nose. The P-38M, which arrived too late to

serve in the European theater, was a two-seat night-fighter carrying a radar

in a chin pod.

P-38J DATA

Engines Two 1,425 hp (1,062 kW) Allison V-1710-89/91

Wing Span 52 ft 0 in (15.85 m)

Length 37 ft 10 in (11.53 m)

Max T-O Weight 21,600 lb (9,798 kg)

Max Level Speed 414 mph (666 km/h)

Range 450 mi (724 km)

Armament One 20 mm cannon and four .50 caliber machine

guns, plus up to 2,000 lb of external stores

P-38J COCKPIT

3

2

1

5 6

7

10

1. COMPASS

2. SUCTION GAUGE

3. CLOCK

4. DIRECTIONAL GYRO

5. ARTIFICIAL HORIZON

6. MANIFOLD PRESSURE GAUGE

7. TACHOMETER

26

4

11 12 13

16

17

8. ENGINE GAUGE CLUSTER:

FUEL & OIL PRESSURE,

TEMPERATURE (LEFT ENGINE)

9. ENGINE GAUGE CLUSTER:

FUEL & OIL PRESSURE,

TEMPERATURE (RIGHT ENGINE)

10. FRONT (RESERVE) FUEL TANKS

GAUGE

11. ALTIMETER

8 9

14

15

12. AIRSPEED INDICATOR

13. BANK AND TURN INDICATOR

14. RATE OF CLIMB INDICATOR

15. CARBURETOR AIR TEMPERATURE

GAUGE

16. REAR (MAIN) FUEL TANKS GAUGE

17. HYDRAULIC PRESSURE GAUGE

Page 26

MUSEUM COLLECTION

P-38J GAME LOADOUTS

Clean Fuel HVAR HVAR 500 lb 500 lb 1000 lb

Primary Guns Type/Number .50 cal x 4 .50 cal x 4 .50 cal x 4 .50 cal x 4 .50 cal x 4 .50 cal x 4 .50 cal x 4

Location Fuselage Fuselage Fuselage Fuselage Fuselage Fuselage Fuselage

Rounds/Gun 500 500 500 500 500 500 500

Secondary Guns Type/Number 20 mm x 1 20 mm x 1 20 mm x 1 20 mm x 1 20 mm x 1 20 mm x 1 20 mm x 1

Location Fuselage Fuselage Fuselage Fuselage Fuselage Fuselage Fuselage

Rounds/Gun 150 150 150 150 150 150 150

Bombs Type – – – – 500 lb 500 lb 1,000 lb

Location – – – – Wing Wing Wing

Number – – – – 2 2 2

Rockets Type – – HVAR HVAR – HVAR –

Location – – Wing Racks Wing Racks – Wing Racks –

Number/Rack – – 5 5 – 5 –

Drop Tanks Type – 165 US gal – 165 US gal – – –

Location – Wing – Wing – – –

Number – 2 – 2 – – –

Fuel, HVAR

MESSERSCHMITT BF 109

Perhaps the most famous German fighter ever built, the Bf 109 earned a

place in the annals of all-time great warplanes by virtue of its early-war

performance alone—to say nothing of the fact that it faithfully served as

the mainstay of the Luftwaffe from before hostilities commenced in 1939

until the capitulation of Germany in May 1945. A fundamentally good

design allowed it to be employed in an incredibly wide variety of tasks, and

the fact that some 35,000 were built speaks volumes of the airplane’s

usefulness.

In 1933 the Reichsluftfahrtministerium (Air Transport Ministry), or RLM,

issued a specification for a monoplane fighter to replace the biplane fighters (Arado Ar 68 and Heinkel He 51) then available to the still-clandestine

Luftwaffe. Contracts for prototypes were awarded to Arado, Bayerische

Flugzeugwerke, Focke-Wulf, and Heinkel. Few expected Willy Messerschmitt and Bayerische Flugzeugwerke to produce a winning design in the

area of high speed fighters, whatever the success of their earlier Bf 108 Taifun touring airplane. When it came time for competitive trials, however,

Messerschmitt’s Bf 109 V1 performed admirably against the Ar 80 V1, Fw

159 V1, and He 112 V1. A low wing monoplane with retractable landing

gear, the 109 was clearly a breed apart from the open cockpit designs proposed by Arado and Focke-Wulf, or Heinkel’s high-wing fighter. The RLM

ordered an additional 10 experimental Bf 109s, but—hedging their bets

perhaps—ordered 10 of the Heinkel design as well. This led to further trials in late 1935, during which the Bf 109 proved its superiority.

27

Page 27

WORLD WAR II FIGHTERS

Ironically, the 109 first flew under the power of imported Rolls-Royce

Kestrel VI engine, since the Jumo 210 engine intended for it was not

finished.

The proposed Bf 109A was cancelled when its armament of just two 7.9

mm MG 17 machine guns in the upper cowling was deemed inadequate.

Provision was made for a possible third gun firing through the airscrew,

and a number of Bf 109B-1, B-2, and C fighters were delivered to Luftwaffe

units operating with the Condor Legion in Spain. Pilots gained considerable experience while participating in the Spanish Civil War, formulating

tactics and suggesting improvements to the 109, which already was

proving capable of going head-to-head with the best Republican fighter,

the Russian-built Polikarpov I-16.

The Bf 109D powered by the Daimler-Benz DB 600 engine was produced

in limited quantities, but by the time the war broke out in 1939, the Bf 109E

with the more powerful 820 kW (1,100 hp) DB 601A engine was taking the

place of the ‘Dora’ on the production lines. The 109E or ‘Emil’ housed

additional MG 17 machine guns or 20 mm MG FF cannon in the wings,

and some variants housed a fifth MG FF cannon in the propeller hub. The

Emil was produced in great numbers—it was the primary fighter used in

the Battle of France and the Battle of Britain—and many were exported to

foreign clients in return for hard cash. The airplane’s tremendous speed

advantage was its greatest asset in the first few years of the war. It suffered

against early RAF Spitfires in the area of turning performance, and its fuel

capacity was small (a serious liability, as the Germans discovered, during

the Battle of Britain), but otherwise the Bf 109E was the superior machine.

The ‘Emil’ began to take on additional roles: fighter-bomber, reconnaissance airplane, high-altitude interceptor with power-boosting, and a

modified version for fighting in the Mediterranean.

By the time Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, the Bf 109F was

being introduced. This airplane—now powered by an 894.2 kW (1,200 hp)

DB 601N or 969 kW (1,300 hp) DB 601E engine—eliminated the aerodynamically unattractive braces under the tailplane while introducing a

retractable tailwheel. The wing guns were eliminated entirely—pilots

would now rely on a pair of MG 17s in the upper nose deck, and a single

high-velocity MG 151/20 cannon firing through the airscrew.

In the summer of 1942, the Luftwaffe introduced the Bf 109G into service.

This model was powered by the 1,100 kW (1,475 hp) DB 605 series of

engines, the intention being to increase the airplane’s speed performance

at the expense of maneuverability. The ‘Gustav’ was built in larger numbers

than any other variant of the 109—despite the fact that it was no longer the

equal of the newest Allied fighters—and G models would continue to roll

off the production line until the end of the war. A few other other versions

were also developed, including the high-altitude Bf 109H (with increased

wing span) and the Bf 109K, which was basically an improved 109G.

28

Page 28

MUSEUM COLLECTION

BF 109G-6 DATA

Engines One 1,099-1,490.4 kW (1,475-2,000 hp) Daimler-Benz

DB 605

Wing Span 9.92 m (32 ft 6.5 in)

Length 8.84 m (29 ft .5 in)

Max T-O Weight 3,150-3,678 kg (6,945-8,109 lb)

Max Level Speed 621 km/h (386 mph)

Range 563 km (350 mi)

Armament One 30 mm MK 108 cannon, two 12.7 mm MG 131

machine guns, and (optional) two 20 mm MG 151

cannon. One 250 kg bomb or 500 kg bomb with

release take-off carriage.

BF 109G-6 COCKPIT

7

1. AMMUNITION COUNTERS

2. CLOCK

3. COMPASS

4. TURN AND BANK INDICATOR/

ARTIFICIAL HORIZON

5. MANIFOLD PRESSURE GAUGE

6. RADIO DIRECTION FINDER

1

3

4

8

2

5

6

10

9

7. ALTIMETER

8. AIRSPEED INDICATOR

9. TACHOMETER

10. PROPELLER PITCH INDICATOR

11. FUEL GAUGE

12. OIL AND PRESSURE GAUGE

11

12

29

Page 29

WORLD WAR II FIGHTERS

BF 109 GAME LOADOUTS

Clean Fuel Gun Pods Gun Pods 500 kg 250 kg

Primary Gun Type/Number 30 mm x 1 30 mm x 1 30 mm x 1 30 mm x 1 30 mm x 1 30 mm x 1

Location Airscrew Airscrew Airscrew Airscrew Airscrew Airscrew

Rounds/Gun 60 60 60 60 60 60

Secondary Guns Type/Number 13 mm x 2 13 mm x 2 13 mm x 2 13 mm x 2 13 mm x 2 13 mm x 2

Location Cowling Cowling Cowling Cowling Cowling Cowling

Rounds/Gun 300 300 300 300 300 300

Secondary Guns Type/Number – – 20 mm x 2 20 mm x 2 – –

Location – – Wing Pods Wing Pods – –

Rounds/Gun – – 120 120 – –

Bomb Load Type ––––500 kg250 kg

Location ––––Centerline Centerline

Number ––––1 1

Drop Tank Type – 300 ltr – 300 ltr – –

Location – Centerline – Centerline – –

Number – 1 – 1 – –

Fuel,

MESSERSCHMITT ME 262

In early 1939, the Reichsluftfahrtministerium (Air Transport Ministry), or

RLM, requested that Messerschmitt AG design a fighter powered by a pair

of the new reaction-turbine engines then under development. Surely no

one imagined that a war launched in that same year would see the development, production, and combat deployment of an airplane propelled by

such revolutionary—and still experimental—means. However, it is difficult

to understand why, once the war got underway, German procurement officers did not give top priority to the development of Messerschmitt’s P 1065

V1 project, or for that matter the equally promising turbojet-powered

Heinkel He 280 V2 prototype. Germany’s overwhelming successes in the

first few years of the war certainly contributed to a general feeling of complacency concerning the next generation of fighters, and at any rate, German manufacturers had their hands full just trying improve the aircraft

already streaming out of the factories. Nonetheless, it’s fascinating to

speculate what the outcome of the European war would have been had

German jet-powered fighters been available as early as 1943, when American strategic bombing forces were beginning to tie up large numbers of

Luftwaffe resources.

Whatever one’s opinion, Messerschmitt’s project was not a priority when

the P 1065 V1 was fitted with a Junkers Jumo 210G propeller engine in the

spring of 1941 in order to test the airplane in powered flight. The Me 262

V1, as it was now known, showed promise in this and subsequent flights.

By December 1941, experimental BMW 003 engines arrived and were

installed on the airplane. These proved unreliable when both engines

30

Page 30

MUSEUM COLLECTION

experienced a flame-out shortly after takeoff on their maiden flight. Fortunately, an alternate power plant was to be found in the equally experimental 5.88 kN (1,323 pounds static thrust) Junkers Jumo 004. The Junkers

engines were fitted to the Me 262 V3, and these took the airplane on its

first successful jet-powered flight on 18 July 1942.

Contracts for further prototypes were awarded, and the jet earned critical

support when Adolf Galland, in his position as General der Jagdflieger (General of Fighter Pilots), recommended that the airplane be developed at the

expense of less-promising projects. The Luftwaffe ordered 100 production

aircraft, but a particularly destructive raid by the US Eighth Air Force forced

Messerschmitt to relocate its jet center south to Oberammergau in Bavaria.

This caused an unfortunate delay in production, which was exasperated by

a shortage of skilled personnel needed to produce the sophisticated airplanes. It wasn’t until October 1943 that the Me 262 V6 prototype—with

retractable tricycle landing gear, trailing-edge flaps, leading-edge slats, and

provision for four 30 mm MK 108 cannon—was tested and approved.

Pre-production Me 262A-0s were delivered to operational fighter-bomber

units in December 1943. These were tested in France in the early summer

of 1944. The first production version, the Me 262A-1a, arrived shortly

thereafter. Configured as a fighter/interceptor, it was powered by two 8.825

kN (1,984 static thrust) Junkers Jumo 109-004B-1 eight-stage axial-flow

turbojets and was armed with four 30 mm MK 108 cannons. A fighterbomber version—the Me 262A-2a—was armed with two 30 mm cannons

and could carry two 250 kg bombs. Other versions included a reconnaissance airplane, a night fighter, and a number of trial models.

ME 262A-1a DATA

Engines Two 8.825 kN (1,984 lb st) Junkers Jumo 109-004B-1

or 004B-4 turbojets

Wing Span 12.5 m (41 ft 1/8 in)

Length 10.61 m (34 ft 9.75 in)

Max T-O Weight 7,045 kg (15,531 lb)

Max Level Speed 868 km/h (539 mph)

Range 1,050 km (652 mi)

Armament Four 30 mm cannon

31

Page 31

WORLD WAR II FIGHTERS

ME 262A-1a COCKPIT

1

4 5 6

8

79

1. AIRSPEED INDICATOR

2. TURN AND BANK INDICATOR/

ARTIFICIAL HORIZON

3. RATE OF CLIMB INDICATOR

4. ALTIMETER

5. COMPASS

6. RADIO DIRECTION FINDER

7. CLOCK

8. OXYGEN PRESSURE GAUGE

9. OXYGEN FLOW INDICATOR

10. AMMUNITION COUNTER

11. TACHOMETER (LEFT ENGINE)

12. TACHOMETER (RIGHT ENGINE)

2

3

11 12

13 17 14

10

15 19 16 20

21 22

13. GAS PRESSURE INDICATOR (LEFT ENGINE)

14. GAS PRESSURE INDICATOR (RIGHT ENGINE)

15. INJECTION PRESSURE INDICATOR

(LEFT ENGINE)

16. INJECTION PRESSURE INDICATOR

(RIGHT ENGINE)

17. GAS TEMPERATURE INDICATOR

(LEFT ENGINE)

18. GAS TEMPERATURE INDICATOR

(RIGHT ENGINE)

19. OIL PRESSURE INDICATOR (LEFT ENGINE)

20. OIL PRESSURE INDICATOR (RIGHT ENGINE)

21. FUEL SUPPLY (LEFT ENGINE)

22. FUEL SUPPLY (RIGHT ENGINE)

18

32

Page 32

MUSEUM COLLECTION

ME 262A-1a GAME LOADOUTS

Clean R4M 250 kg

Main Guns Type/Number 30 mm x 2 30 mm x 2 30 mm x 2

2nd Guns Type/Number 30 mm x 2 – –

3rd Guns Type/Number – – –

Bomb 1 Type – – 250 kg

Bomb 2 Type – – –

Rockets Type – R4M –

Drop Tanks Type – – –

Location Fuselage (top ports) Fuselage (top ports) Fuselage (top ports)

Rounds/Gun 100 100 100

Location Fuselage – –

Rounds/Gun 80 – –

Location – – –

Rounds/Gun – – –

Location – – Centerline

Number – – 2

Location – – –

Number – – –

Location – Wing Racks –

Number/Rack – 12 –

Location – – –

Number – – –

NORTH AMERICAN P-51 MUSTANG

Measured by the standards of pure performance and its influence upon the

course of the war, the P-51 was the best US fighter of the war and arguably

the finest produced by any nation. Incredibly, the airplane that would be

become the renowned Mustang was designed and developed in a threemonth crash program by a young company with no experience making

fighter airplanes, North American Aviation. This was in the summer of

1940, and North American designers Raymond Rice and Edgar Schmued

could take full advantage of technological advances not available to European and Japanese airplane manufacturers just a half a decade earlier. The

most important advances incorporated by Rice and Schmued was a laminar-flow wing section—in which the thickest part of the wing is pushed

further back, the effect being an overall lower drag quotient—and the positioning of the radiator duct. Referencing promising work done on prototypes of the P-40, the designers positioned the coolant system and radiator duct aft of the pilot and wing, which reduced drag and under certain

conditions created a slight amount of positive thrust. This resulted in an

extremely efficient airplane that could reach high speeds even while carrying an enormous amount of fuel—a long-range fighter of superlative performance had been born.

33

Page 33

WORLD WAR II FIGHTERS

The prototype NA-73X flew on 26 October, 1940. A year later, the RAF

began to receive the first of 320 Mustang I fighters. Evaluations proved the

fighter was outstanding in all respects except high-altitude performance.

The fault lay in the chosen power plant, the 1,150 hp (857 kW) Allison

V-1710-F3R engine. The Mustang I fighters were assigned to ground attack

duties and armed with four .50 caliber guns (two below the engine cowling

and one in each wing) and four .303 inch guns. Three hundred Mustang

IA fighters followed with an armament of four 20 mm cannon and

provision for bombs.

By 1942, the USAAF began to take note of the airplane’s potential and

ordered a number of the fighters as low-altitude fighters (P-51 and P-51A),

ground attack aircraft (A-36A), and reconnaissance airplanes (F-6As).

Meanwhile, both sides began testing Mustangs with Rolls-Royce Merlin

engines driving four-bladed propellers. The results were impressive—a

maximum speed of 440 mph (710 km/h) was possible. In 1943 North

American began delivering the P-51B and C (Mustang III), most of which

were powered by a Packard-built 1,520 hp (1,133 kW) V-1650-3 engine.

Armament consisted of four .50 caliber machine guns installed in the

wings, with hard points for bombs or drop tanks. Photo-reconnaissance

versions (F-6B and F-6C) were also produced.

In 1944, the definitive P-51D (Mustang IV) version was introduced, and it

was this fighter that would be produced in greater numbers than all other

versions combined. It featured numerous improvements: a new 1,590 hp

(1,186 kW) Packard V-1650-7 engine, an armament increase to six .50

caliber machine guns, and a teardrop-shaped clear ‘bubble’ canopy

replacing the flush framed canopy. Later D models would also add an 85

US gallon (322 ltr) fuel cell behind the pilot’s seat, and an extra rudder fin

to relieve directional stability problems. A number of F-6D reconnaissance

Mustangs were also produced.

By the close of the war, only minor improvements were possible. The

P-51K and F-6K differed only in having an Aeroproducts propeller. North

American also sought to improve performance by creating lightweight

Mustangs, which resulted in the P-51H, L, and M.

P-51D DATA

Engines One 1,590 hp (1,186 kW) Packard V-1650-7

Wing Span 37 ft .5 in (11.29 m)

Length 32 ft 2.5 in (9.81 m)

Max T-O Weight 11,600 lb (5,206 kg)

Max Level Speed 437 mph (703 km/h)

Range 950-2,080 mi (1,529-3,347 km)

Armament Six .50 caliber machine guns, plus up to 2,000 lb of

external stores

34

Page 34

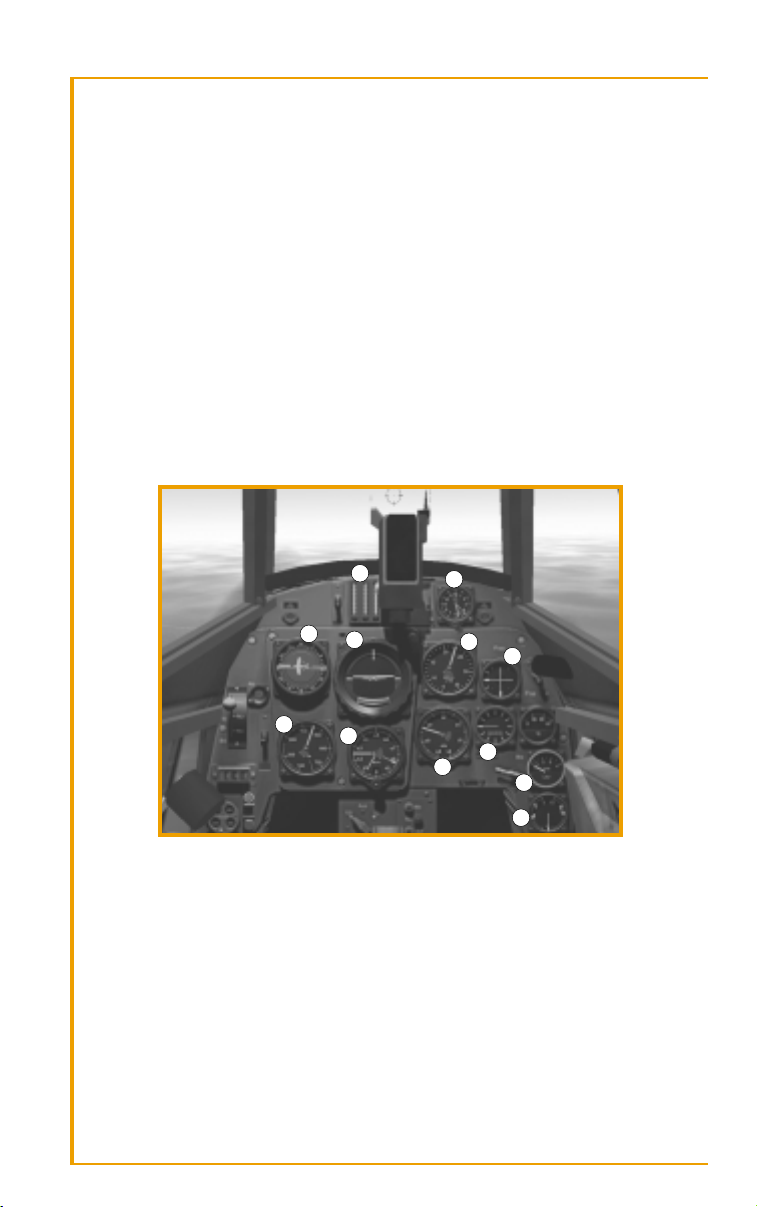

P-51D COCKPIT

1

2 3 4

MUSEUM COLLECTION

5 7 8

6

1. RADIO DIRECTION FINDER

2. CLOCK

3. SUCTION GAUGE

4. MANIFOLD PRESSURE GAUGE

5. AIRSPEED INDICATOR

6. ALTIMETER

7. COMPASS

8. ARTIFICIAL HORIZON

10

14

9. COOLANT TEMPERATURE GAUGE

10. CARBURETOR AIR TEMPERATURE GAUGE

11. TACHOMETER

12. ENGINE GAUGE CLUSTER:

FUEL & OIL PRESSURE, TEMPERATURE

13. TURN INDICATOR

14. VERTICAL SPEED INDICATOR

11

1213

9

P-51D GAME LOADOUTS

Clean Fuel HVAR 500 lb 500 lb, HVAR

Primary Guns Type/Number .50 cal x 6 .50 cal x 6 .50 cal x 6 .50 cal x 6 .50 cal x 6

Bombs Type – – – 500 lb 500 lb

Rockets Type – – HVAR – HVAR

Drop Tanks Type – 75 US gal – – –

* The two inner guns carry 500/gun

Location Wing Wing Wing Wing Wing

Rounds/Gun 270* 270* 270* 270* 270*

Location –––WingWing

Number –––2 2

Location – – Wing Racks – Wing Racks

Number/Rack – – 3 – 3

Location – Wing – – –

Number – 2 – – –

35

Page 35

WORLD WAR II FIGHTERS

REPUBLIC P-47 THUNDERBOLT

To anybody viewing Republic’s P-47 during the war years, the airplane’s

most obvious characteristics were its monstrous size in comparison to

other fighters and its resemblance to an oversized milk jug. But while the

Thunderbolt was the largest and heaviest single-engine fighter of the war,

it more than proved its effectiveness in virtually every theatre in which the

US fought.

An experimental XP-47 project was begun in 1940, but events showed that

greater performance, self-sealing fuel tanks, pilot armor, weapon pylons,

and heavy armament were needed if the airplane was to compete in

Europe. A totally new XP-47B was designed around a new power plant: the

turbocharged Pratt & Whitney XR-2800 Double Wasp engine. The turbocharger was mounted in the underside of the rear fuselage. The engine

exhaust passed under the wing to the turbocharger, where it was fed

through a ‘waste gate’ valve system that controlled the amount of hot gas

that, depending on altitude, drove a turbine. This powered a compressor

that fed air via ducts and intercoolers to the engine, which increased

power. The elaborate gas-exchange system took up a lot of space and gave

the P-47 its particularly bottle-like appearance.

A massive 12 ft 2 in (3.7 m) tall propeller was required to utilize the power,

which in turn required long landing gear. This left little room for the eight

.50 caliber machine guns and their 425 rounds each of ammunition.

Designer Alexander Kartveli solved the problem brilliantly by designing

landing gear that shortened nine inches in length while retracting. The

XP-47B flew on 6 May 1941, with the first production P-47Bs being delivered in June 1942 to the 56th Fighter Group at Mitchell Field in New York.

The B models had fabric covered ailerons and rudders which proved problematical. The P-47C replaced the faulty surfaces with ones covered in

metal sheets, and incorporated other minor improvements. The P-47Cs

were rushed off to England to fight in the European theater. At first the

huge, ungainly birds were regarded with skepticism by the pilots, but

opinions changed once its virtues were displayed: devastating firepower,

an ability to turn altitude into speed (due to the aircraft’s great weight),

and unequaled toughness in the face of extreme battle damage.

The P-47D introduced a large number of improvements: new and more

powerful versions of the R-2800 Double Wasp, increased internal fuel

capacity, provision for jettisonable underwing drop tanks, the ability to

carry weapon loads up to 2,500 lb (1,134 kg), and a new, wider Hamilton

Standard Hydramatic propeller. With the D model, Thunderbolts carrying

drop tanks could escort bombers deep into Germany.

The other full-production versions were the P-47M and N. The M was a

stripped-down version capable of 505 mph (811 km/h) and was intended

36

Page 36

MUSEUM COLLECTION

for use against Germany’s flying bombs. The N model was a long-range

variant for use in the Pacific. It had an increased wingspan and internal

wing tanks that could carry 93 US gallons (352 ltr) of fuel in each wing.

P-47D DATA

Engines One 2,535 hp (1,889 kW) Pratt & Whitney R-2800-59

Double Wasp

Wing Span 40 ft 9.25 in (12.4 m)

Length 36 ft 1.25 in (11.03 m)

Max T-O Weight 19,400 lb (8,800 kg)

Max Level Speed 428 mph (690 km/h)

Range 590 mi (950 km)

Armament Eight .50 caliber machine guns, plus up to 2,500 lb of

external stores

P-47D COCKPIT

2

16

8

109

7

12 15

1. ARTIFICIAL HORIZON

2. LANDING GEAR AND FLAP POSITION

INDICATOR

3. SUCTION GAUGE

4. CARBURETOR AIR TEMPERATURE GAUGE

5. TURBO TACHOMETER

6. FUEL GAUGE

7. ALTIMETER

8. AIRSPEED INDICATOR

9. BANK AND TURN INDICATOR

1

1317

10. RATE OF CLIMB INDICATOR

11. TACHOMETER

12. HYDRAULIC PRESSURE GAUGE

13. MANIFOLD PRESSURE GAUGE

14. ENGINE GAUGE CLUSTER: FUEL & OIL

PRESSURE, TEMPERATURE

15. CYLINDER HEAD TEMPERATURE GAUGE

16. COMPASS

17. RADIO DIRECTION FINDER

4

5

11

14

63

37

Page 37

WORLD WAR II FIGHTERS

P-47D GAME LOADOUTS

Clean Fuel HVAR HVAR 500 lb HVAR 1000 lb

Primary Guns Type/Number .50 cal x 8 .50 cal x 8 .50 cal x 8 .50 cal x 8 .50 cal x 8 .50 cal x 8 .50 cal x 8

Location Wing Wing Wing Wing Wing Wing Wing

Rounds/Gun 425 425 425 425 425 425 425

Bombs Type – – – – 500 lb 500 lb 1,000 lb

Location – – – – Wing Wing Wing

Number – – – – 2 2 2

Rockets Type – – HVAR HVAR – HVAR –

Location – – Wing Racks Wing Racks – Wing Racks –

Number/Rack – – 5 5 – 5 –

Drop Tanks Type – 75 US gal – 75 US gal – – –

Location – Wing – Wing – – –

Number – 2 – 2 – – –

Fuel, 500 lb

SUPERMARINE SPITFIRE

Though its numerical contribution to the Battle of Britain was not as great

as that of the Hurricane, the Spitfire’s psychological contribution was enormous. The airplane became a proud symbol of England’s resolute defiance

of Hitler, defending the kingdom from the German bomber armadas and

thereby denying Hitler the critical precondition he would need in order to

launch an invasion of the British Isles. But the Spitfire was more than a

potent symbol—the strength of its design was proven in six years of war,

during which (through numerous modifications) it remained a frontline

fighter that could challenge the best that Germany had to offer.

The Spitfire originated with a 1931 Air Ministry specification calling for a

single seat fighter to replace the British Bulldog. Supermarine’s prototype

was not accepted, but it prompted Supermarine’s brilliant designer, R.J.

Mitchell, to begin private work on a new prototype. Known as the Type

300, Mitchell’s new airplane would incorporate the new 1,000 hp (745.7

kW) Rolls-Royce PV-12 engine, which only later would be known as the

Merlin. The airplane clearly had great potential, and the Air Ministry subsequently funded a prototype, followed closely by an order for over 300

Spitfires in July 1936 (later increased by an additional 500).

The Spitfire Mk I was a conventional low-wing monoplane of all-metal

stressed skin and fabric-covered control surfaces, powered by a 1,030 hp

(767.5 kW) Rolls-Royce Merlin II or III engine. Armament consisted of

either eight .303 inch machine guns or two 20 mm cannons and four .303

inch guns. Production of the Mk I proceeded until 1939, during which the

aircraft underwent numerous modifications: the flat canopy panels were

replaced by curved canopy; armor plating was added behind the pilot; and

38

Page 38

MUSEUM COLLECTION

electric power was added to the undercarriage controls. Additionally, the

fixed-pitch two-bladed wooden propeller was replaced by a two-speed

three-bladed propeller.

The Spitfire II was powered by the 1,175 hp (876.1 kW) Merlin XII and

used 100 (rather than 87) octane fuel. Other additions were bulletproof

windscreens, self-sealing fuel tanks, and a jettisonable ‘slipper’ drop tank

fitted under the fuselage. Following the Battle of Britain, the RAF began

phasing out the Hurricane while introducing the Spitfire V, initially fitted

with a Merlin 45 engine. This airplane was the first Spitfire to be deployed

in large numbers overseas, and thus the first to be fitted with tropical

equipment. It would become the most numerous of all Spitfire models.

Sub-variants were also developed to carry drop tanks or bombs.

By 1941, the Germans unleashed the Focke-Wulf 190 on the Channel

Front, and it took a devastating toll on the Spitfire V. The Spitfire VII

powered by the 1,565 hp (1,167 kW) Merlin 61 engine was already on the

drawing boards, but before this version could be fully developed an interim solution to the Focke-Wulf threat would need to be found. This arrived