Page 1

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

Page 2

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

PART ONE -- HISTORICAL BRIEF . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3

History of Hiigaran Landfall . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4

The Rude Awakening . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6

History of Kiith . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8

History of Kiith Somtaaw . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9

The Taidan Republic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14

The Turanic Raiders . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17

PART TWO -- TECHNICAL BRIEF AND GAMEPLAY GUIDE . .19

Installation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .20

Game Controls . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .20

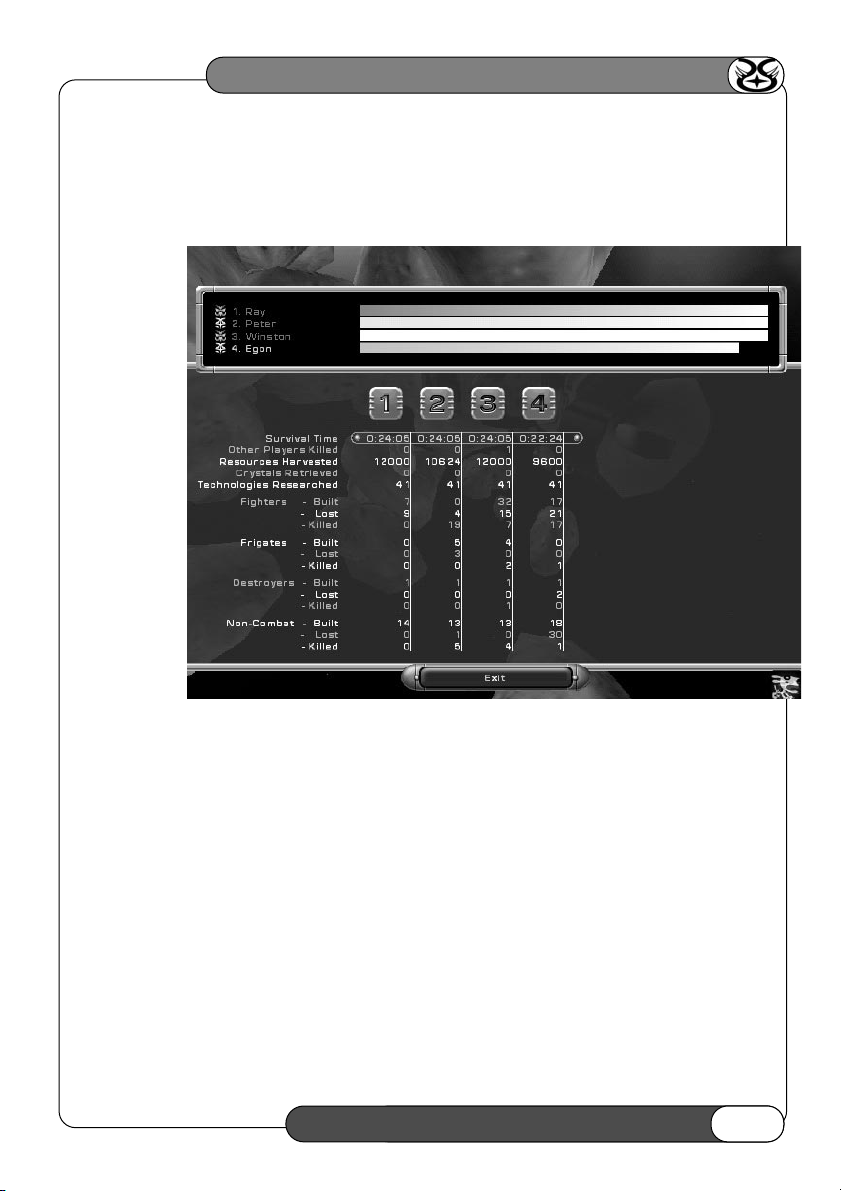

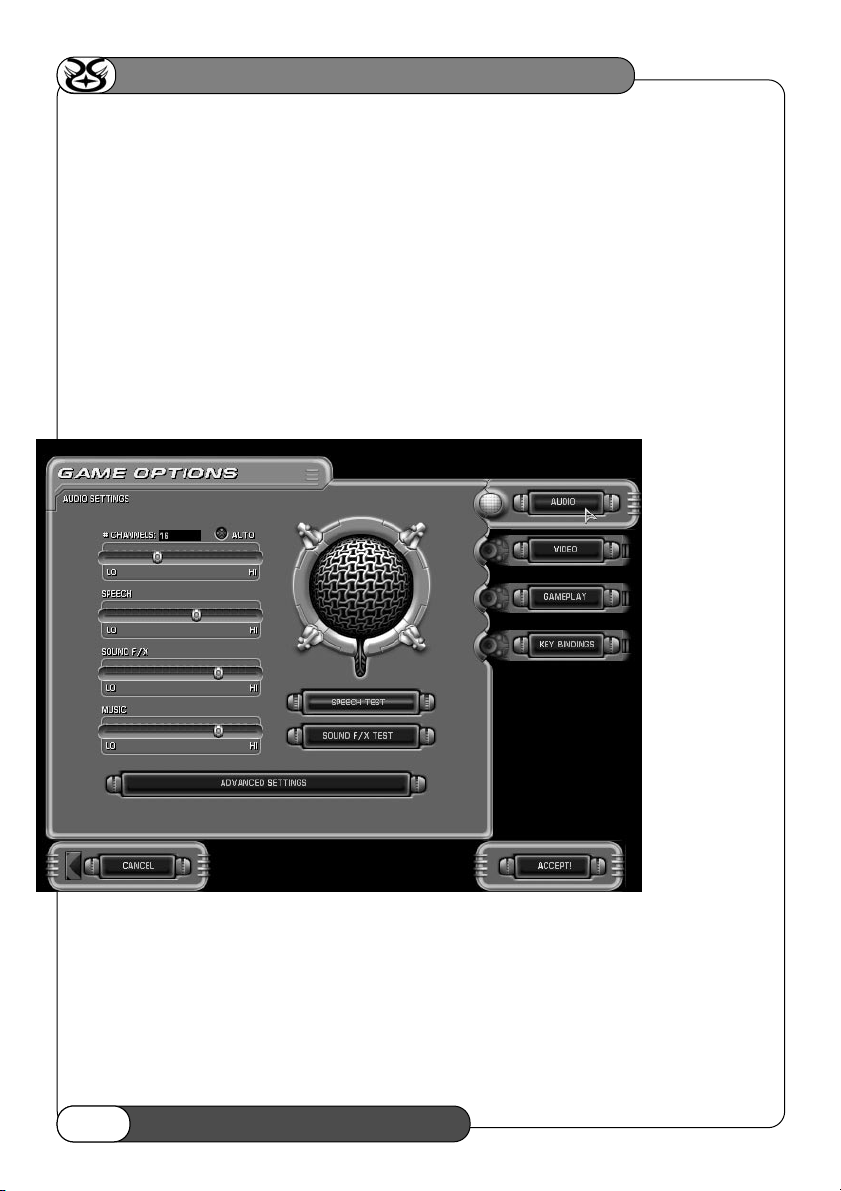

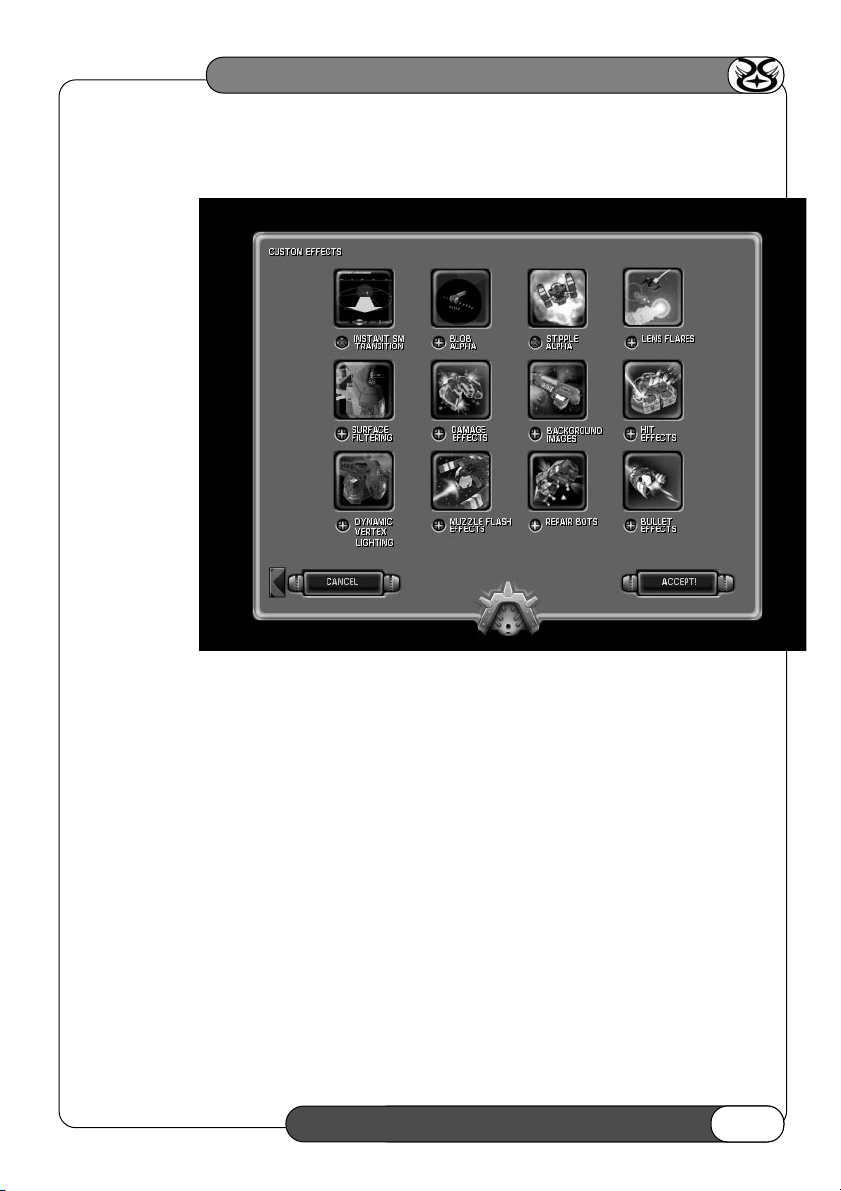

Options . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .68

Game Play . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .73

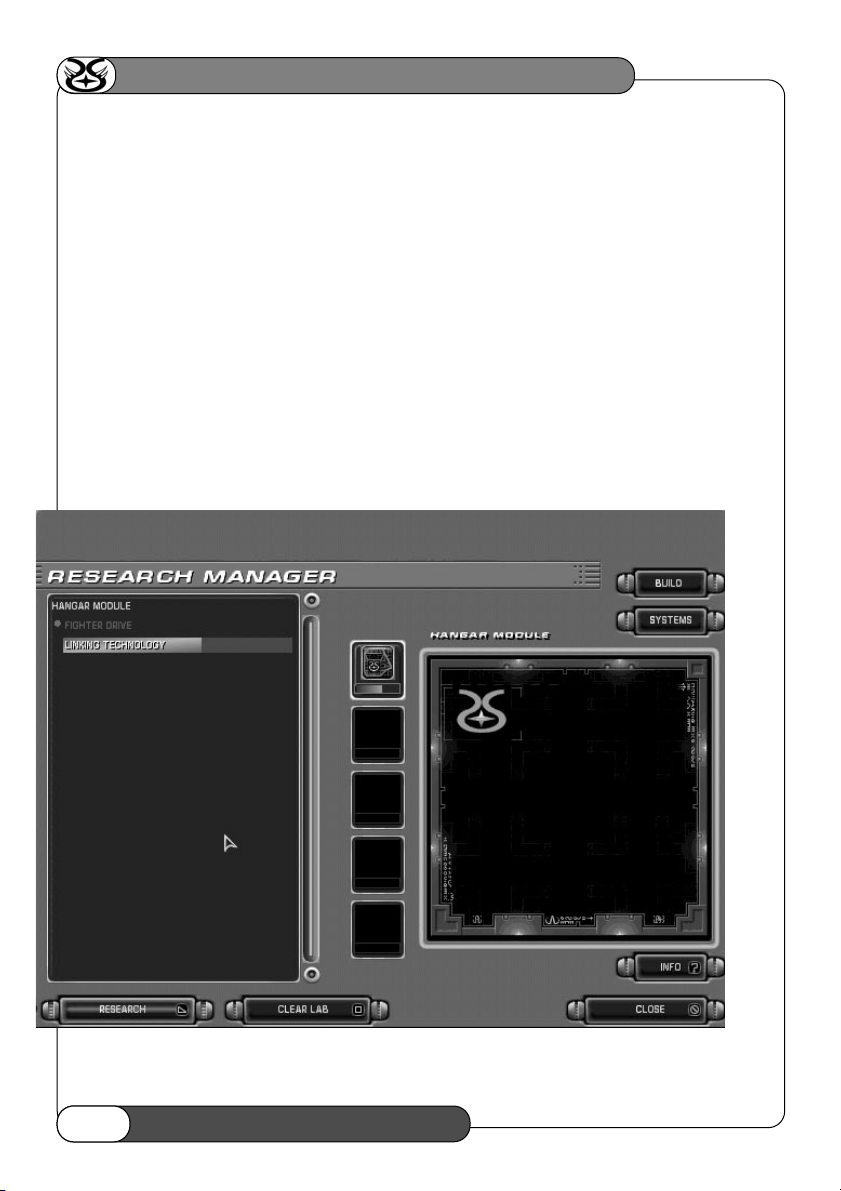

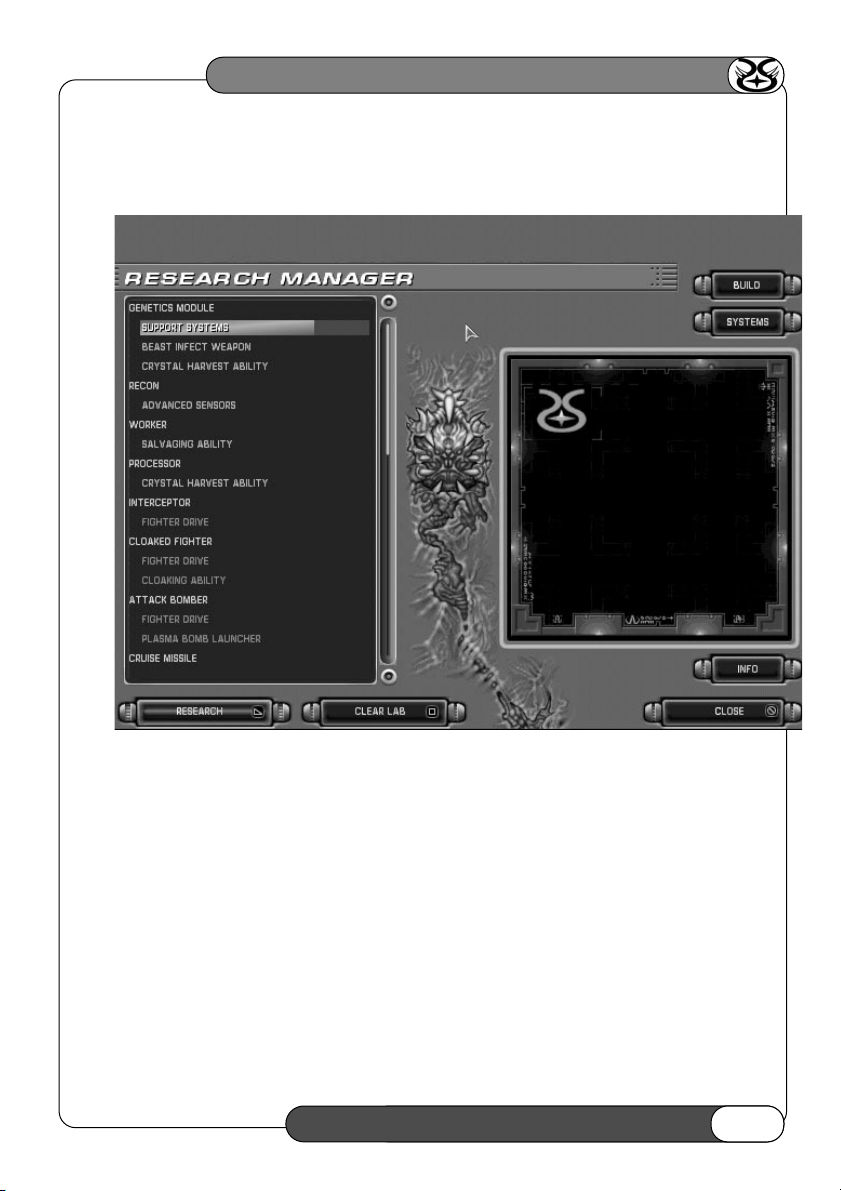

PART THREE -- TECH TREES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .77

Somtaaw Module Tech Tree (Multiplayer) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .78

Somtaaw Tech Tree (Multiplayer) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .79

Beasts Tech Tree (Multiplayer) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .81

PART FOUR -- SHIPS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .83

Kiith Somtaaw Vessels . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .84

Turanic Raider Vessels . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .101

Imperialist Taiidan Vessels . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .107

PART FIVE -- CREDITS AND CUSTOMER SUPPORT . . . . . . .135

Credits . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .136

Technical Support . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .140

2

Page 3

PART ONE -- HISTORICAL BRIEF

Page 4

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

HISTORY OF THE HIIGARAN LANDFALL

The story of the Kushan Exodus to Hiigara is widely known and often told; most of us already know all about the

voyage. In six months, the survivors of our entire race traveled from the prison world of Kharak to our once and

future homeworld. The trip was a major turning point not only for the Kushan people, but for most of the

civilized galaxy; our return to Hiigara was not only the end of our 3,000-year exile, but the end of the Taidani

Empire, and its tyranny over billions.

By the ancient Kharakian dating system, the Kushan people returned to Hiigara in the year 1216 (Galactic

Standard Year 9,510). In honor of the momentous occasion, Kiith Sjet declared the beginning of a new

calendar on the day the returning Kushan first set foot on our homeworld. By decree, the Hiigaran Landfall

marked the first day of a new Year Zero. From that time on, “days” have been measured by Hiigara’s period of

rotation, and “years” according to the revolutions of Hiigara around its mother sun.

By the new dating system, these words are written in the year 15 AHL (GSY 9525)-15 years after Hiigaran

Landfall. The past decade and a half have been a time of both celebration and adversity for the Kushan people.

Nearly 550,000 of us survived the Exodus from Kharak, but our culture has been subjected to tremendous stress.

There is not a single aspect of Kushan existence which we have not been forced to re-examine in light of our new

circumstances. Even the simplest things, like providing our population with food and shelter, have proved far

more complicated than we ever imagined.

Defending ourselves has been our most serious concern. The Bentusi and the new Taidanii Republic have

established a small buffer zone around Hiigara, a region approximately 10 lightyears in diameter. Anything within

a 5 lightyear radius of Hiigara is considered our space, and we are obligated to defend it. Our warrior kiithid are

forced to maintain constant patrols to keep our spaceways from being overrun, not only by the mongrel ships of

the pirate races, but by the last bitter remnants of the Imperial fleet.

The Mothership, which once carried our people safely across 35,000 lightyears of uncharted space, is no longer

fully operational. Deprived of the conscious

direction of Karan Sjet, the Mothership’s engines are

set on automatic; She serves as an orbital space

station and shipyard. Manned by a skeleton crew of

8,000 engineers, the Mothership provides living

quarters for those working in low orbit, and She has

given birth to over 30 carrier-class ships since the

Hiigaran Landfall. The result of this phenomenal output has been a new Hiigaran navy, which consists of

six great Fleets; the largest of our present-day kiithid

have each taken command of an autonomous carrier group. The fleets of Manaan, Soban, Naabal,

LiirHra, Paktu and Kaalel take turns patrolling the

outer systems, guarding our trade routes, and

defending Hiigara itself.

44

Page 5

Addressing the practical concerns of our people has been hard enough; up until the year 11 AHL (9521 GSY) ,

food rationing was common, and on the surface of Hiigara, thousands are still engaged in construction. Providing

for our peoples’ practical needs has been difficult, however, providing for their political needs has been far, far

more troublesome. Kushan society has been in a state of flux since the Exodus; finding some way to give all our

people a fair say in government is a serious problem, and no one is entirely satisfied by any solution.

The New Daiamid was completed in the year 4 AHL, (9514 GSY) the crowning glory of our planetary capital at

Asaam Kiith’sid. The Daiamid Assembly is still the main governing body of the Kushan race, although its

detractors claim that the New Daiamid cannot rule as fairly as its predecessor on Kharak once did. Such

hotheads denounce the current Assembly as a sham, and maintain that a few families wield too much power.

Sadly, there is some merit to this accusation! Over one-half of the Kushan population now belong to one of six

kiithid, and by virtue of sheer population the major families have tremendous influence. The Paktu, the Manaan,

the Sjet, Naabal, LiirHra, Kaalel and Soban are by far the largest kiith groupings in existence, and their combined

numbers come to almost 300,000. By contrast, the majority of other kiithid on Hiigara can boast a few hundred

souls at best; most are lucky to have even that many. In some cases the kiithid, once over 100,000 strong on

Kharak, now only have 30 or 40 members.

These smaller kiithid are now collectively known as the Sleepers, because most of them spent the voyage from

Kharak in cryogenic suspension. Coming from all walks of life, the only thing that these men and women have in

common today is their powerlessness in the present Daiamid system. Unable to compete with large kiithid which

can lay claim to half a continent at a time, exhausted by years of struggle for a voice in the Assembly, many of

these small kiithid have given up the fight to establish a power base for themselves on Hiigara. Dozens of Sleeper

clans have chosen in recent years to abandon their ancient names and become vassals instead, joining their

bloodlines to powerhouses like the Paktu or the Naabal. The family honor comes a poor second, as always, to

survival; surrendering to necessity is an ancient tradition among the Kushan. It may eventually come to pass that

the entire kiith system, which still connects us to the life we once lived on Kharak, will collapse.

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

5

HISTORICAL BRIEF

5

Page 6

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

THE RUDE AWAKENING

Sleepers aboard the Mothership would not learn

of the destruction of Kharak until the long journey

to Hiigara had been completed.

THE RUDE AWAKENING

One of the most difficult aspects of the Hiigaran Landfall

was the revival of our so-called “Sleeper Kiithid”, the 92%

of our current population who traveled from Kharak to

Hiigara in cryogenic suspension. Upon arrival on Hiigara, most of our Sleepers faced a very rude awakening. In

some ways, our society is still trying to cope with what they were told, when they rose from cold storage.

There was good news, of course. Every Sleeper was delighted to hear that the Mothership and its crew had

arrived safely on our Homeworld, that the mystery of our origins had been solved, and that the oppressive regime

which once banished us to the far reaches of space had been defeated. But there was very, very bad news as well:

unlike our fighting men and women, the Sleepers had no six-month struggle for survival to cushion their shock

and horror when they heard that Kharak had been destroyed.

No one awakened on Hiigara without an immediate burden of grief and loss...and sometimes guilt and anger as

well. When they went to sleep, most Sleepers had accepted the possibility that they would never see their loved

ones again, but it was generally assumed that those onboard the Mothership would be in far greater danger than

those we left behind. The Sleepers began their mission with a willingness to sacrifice themselves, secure in the

knowledge that their own families and friends would carry on and remember them, if worst came to worst. The

irony of finding that the crew of the Mothership were the only survivors of our race was too much for many to

bear. In the first few weeks after Landfall, there were dozens of suicides.

Only 1 out of every 60 Kushan was aboard the Mothership at launch. Volunteers for Sleep had been forced to

meet some basic criteria for useful skills, age and health. This seemed extremely reasonable at the time, simple

common sense; but some of those practical decisions had cruel consequences in hindsight. For example, no

persons under the age of 17 or over the age of 50 were accepted; the freezing process was considered too great

a risk for those not in optimal condition. There were no children aboard the Mothership, nor any of our

elders. When Kharak burned, the majority of Sleepers lost their blood links to both past and future; they were

left with nothing to hold on to but a few seconds of torturous satellite footage...pictures of our loved ones being

burned alive by the Taidan Imperium.

The Burning of Kharak has kindled a great hatred in the Kushan people, of this there can be no doubt. The

savagery of the Imperial attacks both on Kharak and on their own cryogenic storage units has filled our Sleepers

with what can only be described as bloodthirsty rage...and as many have pointed out, watching the video footage

of the Emperor’s personal guard being cut to ribbons is not the same as being there! We cope with this anger

in various ways, but our society still boils with resentment of the Taidani in general. Of course, most of our

people are capable of distinguishing between the Imperium, which wronged us so cruelly, and the current

besieged Taidan Republic, which is still ruled by the Rebels who helped us win back Hiigara...but sadly, not

everyone can make this distinction. With the constant threat of Imperialist rule, for many Kushan, the only good

66

Page 7

Taidani is a dead one and even the moderates are pushing for he annexation of nearby former Taidan worlds in

the name of security for Hiigara.

All of us have had to make some kind of peace with the past, and go on as best we can. Some of us have thrown

ourselves into the hard work of construction, trying to recreate some small part of what we lost; some of us have

hastened to bring new children into our depleted kiithid. Others have volunteered for military service, and spend

their days repelling Imperial and pirate attacks on our borders. But for some, the ordinary means of coping do

not suffice...

No one embodies the Kushan hatred of Imperials more perfectly than the man now known as Iifrit Tambuur’sa.

Iifrit is the last living member of the Tambuur kiith, and for the past twelve years he has lived largely in the new

Taidan Republic. Tambuur’sa and his young wife, Dava, were the only members of Kiith Tambuur who made the

Gold List, back on Kharak; both of them were chosen as Sleepers, and they were frozen side by side some months

before the Mothership was launched. Unfortunately, when the Taidanii burned Kharak, they also turned and

opened fire on our cryogenic storage units; Dava Tambuur’s life pod was one of many to be irreparably damaged

by the Taidani attack, and she died in transit to Hiigara. When Iifrit Tambuur awoke from cold sleep, he found

that he had lost not only his entire kiith, but his beloved wife as well. He declared Paaura on the Taidan

Imperium, and several Kushan survivors who sympathized with his cause became honorary members of Kiith

Tambuur, in order to share in his “eternal vengeance”. Out of respect for the ancient vow of Paaura, Tambuur’sa

and his people were granted the use of a small frigate, and he has since become one of the most famous bounty

hunters in this quadrant of the galaxy, credited with collecting the heads of over 300 Imperial war criminals.

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

7

HISTORICAL BRIEF

7

Page 8

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

HISTORY OF KIITH

Kushan society is organized along loose family associations. An extended family grouping is called a Kiith

(plural: Kiithid) and most anthrocists agree it is a social artifact that probably dates back before our arrival on

Kharak itself. Interpretation of ancient legends and translations of texts found in the ruins of Khar-Toba suggest

that over generations, all social structures except the most basic family bonds have broken down.

A Kiith has a loose hierarchy based on one’s social position within the family. Originally this was based

primarily on seniority, but as technology has changed the face of life on Kharak, the Kiithid too have changed,

and now family ranking is based more on wealth or personal influence than simple age. Organization within

the Kiith is recursive in nature, and models that of a core family unit. Where a single family has a Primary

leader, a secondary and then a group of dependants, the next level of Kiith organization is based on the same

system. There is a Primary family who makes policy decisions, a Secondary family which hears disputes and

makes recommendations, and a number of families of lesser power that have sworn allegiance to the Primary.

The Primary family for a Kiith is called the Kiith-Sa.

This structure is not static by any means, and, while it is not a trivial matter, families are free to change their

primary allegiances as they see fit. A family’s position within the Kith rises and falls with how many swear

allegiance to them. Although it is much more rare, from time to time a family will move from one Kiith to

another or even feel the need to begin a full Kiith of their own.

In ancient times, a Kiith-Sa could direct the entire Kiith to war, demand all families dedicate time and finances

to special projects, or even move the Kiith to another region. In modern times, the Kiith-Sa is a political and

financial leader only in that it acts on the wishes of the entire Kiith as established by referendums. The Kiith-Sa

from all over Kharak meet in the Great Daiamid located in the capital of Tiir to debate global policy and resolve

legal conflicts between Kiiths.

Traditionally, Kiiths usually concentrate their power in one or two disciplines and gather families under their

banner by being the best place to find advancement in a particular field. For example, Kiith Sjet has been

associated with the sciences on Kharak for over a thousand years, and is known to have the most advanced

computer labs in the world. Bonded couples interested in the field often apply to a S’jet family associated

with such labs. Alliances between Kiith are also based on mutual interests, and they often lead to closer ties

or complete reorganizations.

Never has the Kiith system faced such upheaval than during the years following our people’s arrival on Hiigara,

the homeworld.

88

Page 9

KIITH HISTORY: SOMTAAW

Of the earliest days of Kiith Somtaaw little is known, although this ancient family could once trace its unbroken

lineage back over 1,000 years on Kharak. The Somtaaw made their ancestral homes in the peaks and valleys of

the Kohntala Mountain range, one of the more dramatic geographic features in Kharak’s northern hemisphere.

In the first and second centuries, Somtaaw’s holdings in the Khontala were rich and varied, running the gamut

from farms, dams, and mills to fortresses and towns, including the walled cities of Hameln and Gydeo. The kiith

was more than self-sufficient; the terraced farms of the lowlands and the seasonal grazing pastures of the

highlands produced a great surplus of food and hides, and the Somtaaw prospered in trade.

Starting in the year 178, Kharakian artists from various disciplines were gathered under the patronage of Teigor

Somtaaw, one of the most enlightened kiith’sid of his time. Employing hundreds of skilled masons, painters,

architects and weavers, Kiith Somtaaw began building a series of temples on the slopes of the mountain called

Lungma Jiin, “The Roof of the World”. There were 33 temples in all, leading from the sands of the Kasaar to the

very summit of what was, at that time, the world’s highest known mountain.

Collectively, the 33 temples of the Somtaaw were known as “The Shimmering Path”. For nearly 400 years, it was

considered the height of spiritual devotion for a religiously inclined Kharakian to walk the Shimmering Path;

most Kharakians attempted the trip at least once a lifetime. Beginning at the first temple, the Oracle of Tala, the

distance that a pilgrim was able to travel on his or her own feet was considered a watermark for the strength of

the Faith that burned within.

The vast majority of Kharakians finished the pilgrimage at the Seventh Temple, the famous “Dome of Heaven”,

which lay within the city walls of Gydeo. For those stubborn few who felt the need to move closer to god,

however, there were 26 more temples along the Shimmering Path, each more inaccessible than the last. The

highest of these was Temple of the Mysteries, which very few travelers could reach; the upper slopes of Lungma

Jiin were a blasted ladder of crumbling granite and thin ice, and constantly buffeted by freezing gale force winds.

According to legend, the most sacred relics of the Somtaaw were kept on the altar of this temple, and any

pilgrim who made the journey on foot was permitted to touch them: the famed Star-Metal Scrolls, which were

alleged to have been written by the hand of Jakuul Himself, in a language which no living man could read.

Up until the discovery of Khar Toba, most serious Kharakian scholars had assumed that the Somtaaw’s Star Metal

Scrolls were just a myth, very much like their Chalice of Life or any other mystical refuse from Kharakian legend.

Before the discovery of the Guidestone, the Star-Metal Scrolls were put into the same category as Soban’s sword

Caaliburnos, or the Burning Spear of Gaalsi. However, given the discovery of the Guidestone, a great deal of new

interest was generated in the Somtaaw holy relics. Many prominent anthrocists and historians, including the

famous Mevath Sagald, joined forces and put a motion before the Great Daiamid at Tiir, requesting that the

Somtaaw’s upper temples, which had been closed to outsiders for over 300 years, be re-opened for the benefit

of modern-day scholars.

Alas, nothing came of this motion before the Burning of Kharak. Representatives from Kiith Somtaaw dragged

their heels in the Daiamid assembly, and even went so far as to suggest that archaeologists should approach the

Temple of Mysteries on foot, dressed in traditional pilgrim’s clothes! Sagald and her coalition declared this

notion “ridiculous”, and openly referred to the Somtaaw as “backward barbarians”. Many Sagald supporters

pointed out that the Daiamid was founded to hear sound logical debates, not to listen to superstitious nonsense!

Arguments on both sides were still being heard when the Mothership was launched.

HISTORICAL BRIEF

9

Page 10

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

In any case, we will never know what we might have learned from the Somtaaw Scrolls; they were lost with the

rest of Kharak, and among the Somtaaw survivors who awoke on Hiigara 15 years ago, there were none who

could claim to have seen them. Since the later days of the Heresy Wars, Kiith Somtaaw had largely abandoned

their role as a religious kiith; by the time of the Exodus, the vast majority of Somtaaw’s kiithid were engaged in

another profession, the profession by which they are still best known today: mining.

The transformation of Kiith Somtaaw from a primary religious kiith to a hard-working miner’s kiith was a slow

and painful one, and involved many generations of privation and suffering. The centuries of the Heresy Wars

were hard times for the Somtaaw; their Khontala mountains provided a natural barrier between the forces of

Gaalsi and Siid, and both sides struggled urgently to subdue or seduce the Somtaaw for nearly two hundred years.

The flow of pilgrims to Somtaaw temples slowed disastrously in a world at war, and soon there was not enough

money flowing into the kiith’s coffers to maintain those temples in their intended role, as way-stations along the

Shimmering Path. Eventually, in the year 675, all 33 of the Somtaaw temples were closed to outsiders, except

for the Oracle of Tala and the Dome of Heaven.

By virtue of their own sheer stubbornness, and the natural protection provided by the narrow passes and

forbidding peaks of their homeland, the Somtaaw were able to hold off all invaders during the worst of the

Siidim and Gaalsien conflict. More difficult to resist, however, was the seduction of becoming a vassal clan,

especially when the Somtaaw holdings, although easy to defend, were also easy to cut off from trade routes.

Even a small garrison could hold the Kasaar like a cork in a bottle, and keep the Somtaaw trapped in their

mountain fortresses; invaders couldn’t enter, but neither could caravans and other visitors. Contact with the

outside was sporadic throughout the seventh and eighth centuries...the Somtaaw held no goods sufficiently

inviting to keep the Kasaar Road open.

This changed in the year 789, when Kuura Somtaaw, then kiith’sa of the 30,000 souls who still made their

homes in the Khontala, awoke one night from a strange dream. Kuura had seen the image of the god Sajuuk,

driving a great red sword into the earth in the Khontala mountains, in a seldom-visited region far from the main

roads. Driven by the urgency of her vision, she ordered several smaller families to begin digging in the Red

Creek valley. Because their kiith’sa was descended from the temple women of Tala, the Somtaaw reluctantly

obeyed, and several Somtaaw kiithid moved to the area and began the excavation, although no one was quite

certain what they were looking for.

What the Somtaaw found at Red Creek was a deposit of the richest iron ore ever seen on Kharak, which lay just

six feet below the soft sediments of the valley floor. Here was enough metal to be hammered into a hundred

thousand swords, and Kiith Somtaaw was not slow to announce their find to the rest of the world. Although both

Siid and Gaalsi offered ruinous sums to buy the mine, or the ore that it produced, Kuura Somtaaw refused to

trade with either side. In her own words, “Why should I sell these madmen a knife to cut my throat with?”

Instead, the Somtaaw built their own smelters and began mixing the iron with carbon, producing a very high

grade steel...a commodity far more precious than gold, especially during those dangerous times. An

arrangement that eventually sustained Kuura Somtaaw’s kiith was made with the Sobanii, who immediately saw

the use for Somtaaw steel and the superior weapons that could be forged from it. In exchange for a yearly

tribute from the smelters at Hameln, the Soban signed an unheard-of contract; the mercenary kiith agreed to

keep the Kasaar open and clear of marauders for a period of no less than one hundred years!

With the Naabal intervention, the Somtaaw expanded their operations, throwing themselves into their new

profession with the kiith’s customary enthusiasm. Although they never developed any significant technological

advances on their own, they were always quick to buy, copy or outright steal any new tool or technique, once

10

Page 11

HISTORICAL BRIEF

11

another kiith had put it into operation. Thus the Somtaaw profited greatly from the introduction of

steam-powered drills, narrow-gauge railroads and chemical explosives. By the time of the Exodus, Kiith

Somtaaw was nearly 500,000 strong, and had even built new holdings alongside great industrial kiithid like

Naabal and LiirHra, to the extent of opening off-planet mines in the Kharakian asteroid belt.

The return to Hiigara was not as joyous for Somtaaw as for many of our people. Although a few of their number

were awake during the journey from Kharak, employed in the care and maintenance of resource collectors, the

vast majority of Somtaaw survivors were Sleepers during the journey. When they were awakened on Hiigara, many

were horrified to hear that the families and loved ones they left on Kharak were gone, and that there was no hope

of return. Of a kiith that had once been so strong, very few survivors remained; only 15,000 Somtaaw awakened

on Kharak, less than a twentieth of their number, and the vast majority of these were men.

Kiith Naabal elders address

the New Daiamid.

Somtaaw’s fortunes were further

complicated by a political

conflict with Kiith Naabal,

which made a bid seven years

after landfall to absorb the

Somtaaw survivors as a vassal

clan. It was argued in the New

Daiamid that Somtaaw’s kiithid

had valuable skills, which

could be of the greatest possible

use to Hiigara if channeled by

Naabal’s industrial planning committees. According to the Naabal, it was in the best interests of all Hiigarans if

Somtaaw joined with Kiith Naabal, and provided their mining expertise to the Naabal-owned colonies throughout the Hiigaran buffer zone. Many such mergers had taken place in the past decade, with benefits for all concerned.

Somtaaw flatly refused this proposition, and the debate between Somtaaw and Naabal supporters in the New

Daiamid has already been cited by many as a history-making event. According to the Somtaaw survivors, larger

and more powerful kiithid like Naabal were deliberately campaigning to deprive the weakened Sleeper clans of

their sovereign rights, which included the staking of land claims on Hiigara, a voice in the New Daiamid, and

access to the ship-building capabilities of the Mothership Station. Given that the Mothership’s building array had

already provided whole fleets to the larger kiithid, and no less than fifteen carrier groups each to Naabal, Soban,

Kaalel and Manaan, Kiith Somtaaw argued that they also had the right to seek their fortune among the stars. They

proposed to build themselves a tonnage of starships which was proportional to their kiith numbers.

Page 12

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

During the Somtaaw/Naabal debate, dispossessed members of many Kharak’s devastated kiithid joined the

Somtaaw as family members, swelling their ranks from 15,000 to nearly 25,000 in a few short months. The matter

was contended for months in the Daiamid, with the larger kiithid of the inner council arguing bitterly. Kiith Soban

honored its ancient ties to Somtaaw and opposed Naabal’s power-hungry crusade, and so did the Paktu, a kiith

inclined to support Somtaaw both out of historical sympathy with the underdog and respect for the rising

confederation of Somtaaw with other weakened kiithid. On the opposite side of the table, Kiith LiirHra supported

Naabal vigorously, citing the benefits of their own union with the survivors of the Hraal.

The Kuun-Lan undergoes

final systems check before

launch. The Faal-Corum had

left dock two days earlier.

The matter was eventually

decided in favour of Somtaaw

by a very narrow margin in the

Diamid and only after the

Somtaaw managed to convince

the disenfranchised kiith to

threaten a general strike over

the issue. While many of the established Kiith accused Somtaaw of further undermining the ancient social systems

for their own benifit, the result was Somtaaw was granted access to the Mothership Station for a period of six

months. Mothership access for other lesser Kiith soon followed. In their time, the Somtaaw built two enormous

mining ships, the Kuun-Lan and the Fal-Corum, which were both launched, fully manned,

within 45 days. In the final days of their control over the Mothership’s PDA, Kiith Somtaaw triumphantly built one

final ship, the Clee San, a top-of-the-line deep space research frigate. Students of history will note that the names

of all three vessels derive from the names of temples along the old Shimmering Path: Kuun-Lan, “Purifying Flame”,

Fal-Corum, “Silent Wayfarer”, and Clee San, “Truth Seeker”...

12

Page 13

The Clee-San, Kiith Somtaaw’s

third and final ship. Designed for

deep space mining exploration,

the Clee-San is equipped with an

impression sensor array and

equally impressive onboard

science facilities.

Since then the Somtaaw have

explored many neighboring systems

to Hiigara. Although their numbers

are small, they’ve set up several mining stations to collect rare elements, and they sell the fruits of their labors

to all clients allowed by the current Hiigaran trade regulations. Like all our kiithid, their ships are bound to

respond to any call to arms, when Hiigaran space is violated. But beyond the Somtaaw’s duty to Hiigara, they

live free and bend knee to none but their own kiith’sa...maintaining a centuries-long tradition.

HISTORICAL BRIEF

13

Page 14

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

THE TAIDAN REPUBLIC

THE END OF THE

IMPERIAL ERA

The return of the Exiles to their Homeworld did more than mark a new beginning for life on Hiigara; it also

helped to bring about the end of the Taidani Imperial line, which had ruled continuously for nearly 3,000

standard years.

The Taidan Empire of Year 0 AL (9510 Galactic Standard Year) held 150 star systems in its grip, but not easily.

Emperor Riesstiu IV the Second was rapidly approaching his 4th century of life, and his pogroms and agendas

were becoming increasingly bloody and erratic. Relations with other Galactic civilizations were at an all time

low, with the Empire receiving regular censure from the Galactic Council during their twice-per-decade assemblies.

The Frerrn Aggregate was in a state undeclared war with the Taidan Empire over a number of border issues on

the Far Rim, and even the Bentusi had suspended all trade contact with the Taidan in the year -7 BL (9503 GSY.)

Internal Taidani politics was faring even worse in these last years of the Empire. Tax revolts in the outer systems were

a common occurrence, as Emperor Riesstiu IV’s increasing paranoia led to a prohibitively large and expensive

military. The Taidan Assembly of Lords, a token political body whose task was merely to “rubber stamp” edicts from

the desk of the Emperor, even began to question some of Riesstiu’s more outrageous demands. The entire

political system of the Imperium was corrupt and on the verge of collapse when a Mothership of unknown design

breached Taidani borders, and destroyed 3000 years of political stagnation.

A powerful group of military, political and economic figures had been plotting a coup in secret for years, staying

only steps ahead of one purge or another as they looked desperately for the trigger that could sway 360 billion

souls against their God-like Emperor. Oddly enough, it wasn’t the plight of the Kharakian Exiles as much as the

mindless obedience of the Taidani navy which created that trigger. When the first propaganda images spread

through the Empire, showing yet another victory, this time against an ancient and forgotten enemy, it soon became

obvious that a serious mistake had been made on the part of the Emperor’s political advisors. Instead of

reassuring the Taidani people that their nigh-immortal Emperor was all-seeing and all-powerful, the Taidan reacted

with near-universal horror and disgust. Again and again they were forced to watch one of their fleets commit an

act of genocide against 300 million aliens, who had committed no crime greater than entering hyperspace and

violating a long-forgotten treaty.

The Emperor reacted quickly and ordered the Home Fleet to hunt down and destroy the Exiles before they could

penetrate Taidan space, but it was too late. The political damage had been done, and the secret conspirators

launched their coup against an obviously mad Emperor. While the initial groundswell of support was very strong,

the conspirators and the general public seriously underestimated how prepared the Empire was for just such a

rebellion, and how far their leaders were willing to go in order to maintain their stranglehold on power. After

the first few heady days of rebellion, the Emperor declared full martial-law across the Taidani worlds. According

to his edict, no act performed in the defense of His Throne would be judged in civilian courts.

The death and destruction that followed this announcement throughout the Empire beggars the imagination. For

every military unit that defected to the Coup, 2 others launched an orgy of brutal reprisals. Dukes and Governors

that were unwilling to massacre protestors en masse were executed and replaced by ones who would. Entire

rebellious asteroid cities were exterminated when navy corvettes destroyed their life support systems, and the

slow death throes of millions were recorded, to be shown as an example to the rest of the population. By the

end of the first month it was obvious to all but the most optimistic that the Emperor’s grip on the Taidan could

1414

Page 15

not be thrown off. The final blow was nearly struck at the battle of Vorshan’s Rift, where the gathered rebel Navy

was ambushed and devastated due to a high level defector, who led the rebels into a trap. The ranking surviving

military member of the coup fled for his life, directly into the arms of the one force in the galaxy that was

successfully resisting Imperial power: the returning Exile Fleet. Luckily for the rebellion, the Exiles aided the

Rebel officer, allowing him the chance to escape and regroup the tattered remnants of his fleet.

When news broke that the Exiles were actively aiding the rebellion, it was the final insult to the Emperor. Riesstiu

declared that he would personally command the Taidani High Guard fleet in their crusade against the interlopers.

The final battle took place high above the Exile’s ancient Homeworld, Hiigara, and when it was over the Emperor

lay dead and his Elite guard fleet was shattered.

In the resulting chaos, the Rebels seized their last chance and destroyed the Imperial Gene bank. Without a clear

line of succession through cloning, the Emperor having long ago executed any living relative who might try to

kill him and take power, the Imperial structure collapsed. In its place was erected a new Taidan Republic.

THE TAIDAN REPUBLIC

Even after the death of the Emperor, the new Taidan Republic has had anything but a smooth ride from tyranny

to democracy. What was supposed to be a quick and relatively painless coup flared into a full blown civil war

after the battle of Hiigara. Various factions tried to seize control of the Empire, while entire sectors fought for

independence. After 5 years of skirmishes and all-out battles, the Taidan Republic finally stabilized and established

an uneasy peace within itself...but by the time the shooting stopped, only 60 out of a 150 star systems were willing

to call themselves Taidani. Most of these loyal worlds are centered in the Galactic Core, while the spiral regions

of the old Empire have splintered into a variety of small kingdoms, duchies and independent democratic states.

The Republic is still struggling to restore order both internally and externally and has met with some success.

In year 6 AL (9516 GSY), the Republic signed a formal non-aggression and co-operation pact with the Exiles,

which recognized their ancient claim to Hiigara. A 5-light-year sphere of influence was also granted the new

Hiigarans, in recognition of their aid to the Republic during the dark days of the Coup. Currently, the Republic

and Hiigara share excellent relations, which has only been helped by the Republic’s willingness to extradite war

criminals who took part in the Kharakian Genocide. The Republic also re-established trade relations with the

enigmatic Bentusi, and it is rumored that the Bentusi have been crucial in supplying the new Republic with the

technology, infrastructure and information it needs. Despite these advances, the Republic continues to splinter

away system after system as local leaders decide they are better off on their own, than to be drawn into any

Taidani conflict to come.

While most analysts still are debating whether the worst is over for the Taidan Republic, all agree that stability

needs to be based on military security for the former Empire. With a few years of planning time, the Republic

has stopped trying to match the Imperialist factions on a gun-to-gun basis, and are now trying to seize the high

ground by using advanced technologies. The Taidani military invested vast amounts of their financial reserves in

manpower, for a few crucial fleet Research Stations. Their hope was of making ship design and weapon breakthroughs

that would allow them to defend the Republic’s borders with a vastly reduced fleet. All the progress made by the

Republic could be destroyed overnight, should the surviving Imperialists find a way to overthrow the Republic,

and return a new Emperor to the ancient Throne of Worlds.

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

15

HISTORICAL BRIEF

15

Page 16

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

THE IMPERIALIST FACTION

With the Empire shattered, it was to be expected that many major Imperial figures would flee the Republic to

carve their own domains in the splintered frontier worlds. Many of these Imperialists call themselves “Loyalists”,

and support any one of hundreds of “lost heirs” that have been sprung up over the past 15 years. While the

Imperialist fleet is but a battered shadow of its former power, it is still a significant threat on the frontier, where

many secret naval bases from the Imperial era are intact and functioning.

Imperialist power remains in the hands of the fleet, and while these once-proud ships have been forced to work

as equals with pirates or hire themselves out as mercenaries, they are still a force to be reckoned with, and still

a major threat to the stability of the Republic. Twice in the past 15 years the Imperialists tried to unite the

splintered kingdoms by force of arms, only to be defeated by their own factionalism and the military intervention

of the Galactic Council.

Apart from the desire to overthrow the new Republic, the only other thing that binds the Imperialist Factions

together is their deep, abiding hatred of the new Hiigarans. The Imperialist hold the Exiles and their quest for

their Homeworld directly responsible for the Emperor’s death and the fall of the Empire. Amongst Imperialist

supporters, it is an oft-quoted prophecy that Empire will only rise again when the Imperial Fleet once again orbits

Hiigara, and the work begun with the Kharakian Genocide is finished once and for all.

Needless to say, a state of open warfare exists between Hiigara and all Imperialist factions. Three times in the

past 15 years, (in 4, 9 and 11 AL) the Imperialist led major incursions into the Hiigaran sphere of influence. In

the latter two invasions, strike fleets reached Hiigara itself, only to be thrown back with heavy losses on both

sides. While Hiigaran shipping is constantly being harassed by Imperialist forces, either operating by themselves

or in conjunction with the Turanic Raiders, it has been 4 years since any significant fleet actions took place in

the Hiigaran sphere. This led some analysts to conclude that the Imperialist forces are more interested in consolidating

the splinter kingdoms than wasting more strength and technology on a blood feud with a single world. Others

merely consider this to be the quiet before another inevitable storm.

1616

Page 17

TURANIC RAIDERS

No other group has profited more from the anarchy caused by the retaking of Hiigara and the resulting Taiidani civil

war, than the Turanic Raiders. Nothing is known about the origins of this nomadic race of pirates and mercenaries but

theories range from a disposed race of refugees to a former slave race run amuck. Attacks by Turanic Raiders were first

recorded during the year -475 BL (GSY 9035) in the Turan Sector and hence the name given to this enigmatic warrior

species. Turanic hordes have infested the trade lanes of the galaxy at least twice a century since their arrival and no

matter how much effort is put into hunting them down by one government or another, they always survive in some

hidden base to emerge years later. Most of this growth-and-retreat cycle is spent raiding lone ships or unprotected

convoys in order to slowly build up their power base. The Raiders are at the height of their power fielding carrier groups,

are capable of taking over entire asteroid settlements.

The Turanic Raiders have never been stronger than they were during much of the 1’st century BL when they

enjoyed the patronage of the Mad Taiidani Emperor Riestiu IV. While most details were covered up at the time,

new documents released by the Taiidan Republic during various war crimes trials have revealed the Turanic

Raiders were supported by Imperial funds and supplies. Many of the targets hit by the raiders during this period

were of special military value. Intelligence gathered during these attacks, aided the Emperor to stymie the efforts

of neighboring galactic powers and limit their ambitions. Reliable estimates place Turanic Fleet strengths at

nearly 20 carrier groups spread throughout the Imperial Frontier before the Homeworld War.

Unfortunately for the Raiders, the death of Emperor Reistiu IV and the fall of the Taiidan Empire brought about

their fall as well. As if sensing the wake of history that rippled away from the Exile fleet as it approached Hiigara,

the Turanic Raiders went into hiding and denied the Emperor their firepower when he faced the Exiles in final

battle. The reasons for this may never be exactly known, but when the Taiidani Empire fractured from the pressure

of civil war, the Raiders were in perfect position to seize power in many outlying provinces of the Empire. These

new “Bandit Kingdoms” as they have become known, are centers of power for a new, organized Turanic presence

in the Galaxy and in a final irony, it is now Imperialist factions who come to the Raiders seeking patronage. The

current level of Imperialist/Raider co-operation is not truly known at this point, but there have been scattered

reports in recent years of mixed fleets performing strike and capture operations.

Despite these reports, Raider activity has been relatively low and most experts agree that the Turanic Raiders are

in a build up phase that will continue for quite some time. The only dissenting voice in the Turanic analysis

comes from several Hiigaran Warrior Kiith, who point out the growing number of Hiigaran combat and transport

vessels that have been lost in anomalous circumstances in the past 2 years. The animosity of the Raiders towards

the new Hiigarans is well known, and these losses may be due to new or exotic technologies being introduced

into the Raider’s fleet by their Imperialist Allies.

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

17

HISTORICAL BRIEF

17

Page 18

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

NOTES: ....................................................

..............................................................

..............................................................

..............................................................

..............................................................

..............................................................

..............................................................

..............................................................

..............................................................

..............................................................

..............................................................

..............................................................

..............................................................

..............................................................

..............................................................

..............................................................

1818

Page 19

PART TWO -- TECHNICAL BRIEF + GAMEPLAY GUIDE

Page 20

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

INSTALLATION

Insert the CD- ROM into your CD- ROM drive. The Cataclysm Installation program will automatically start up.

Follow the on-screen instructions to specify the various installation options. When the installation is complete, it

will have created a shortcut in your Start Menu that you can use to run Cataclysm.

If the Cataclysm Installation program does not start up, double-click on the “my computer” icon

on your desktop. Double-click on the CD-ROM drive icon. In the file window, double-click on the

file icon of AUTORUN.EXE. Follow the instructions on screen.

GAME CONTROLS

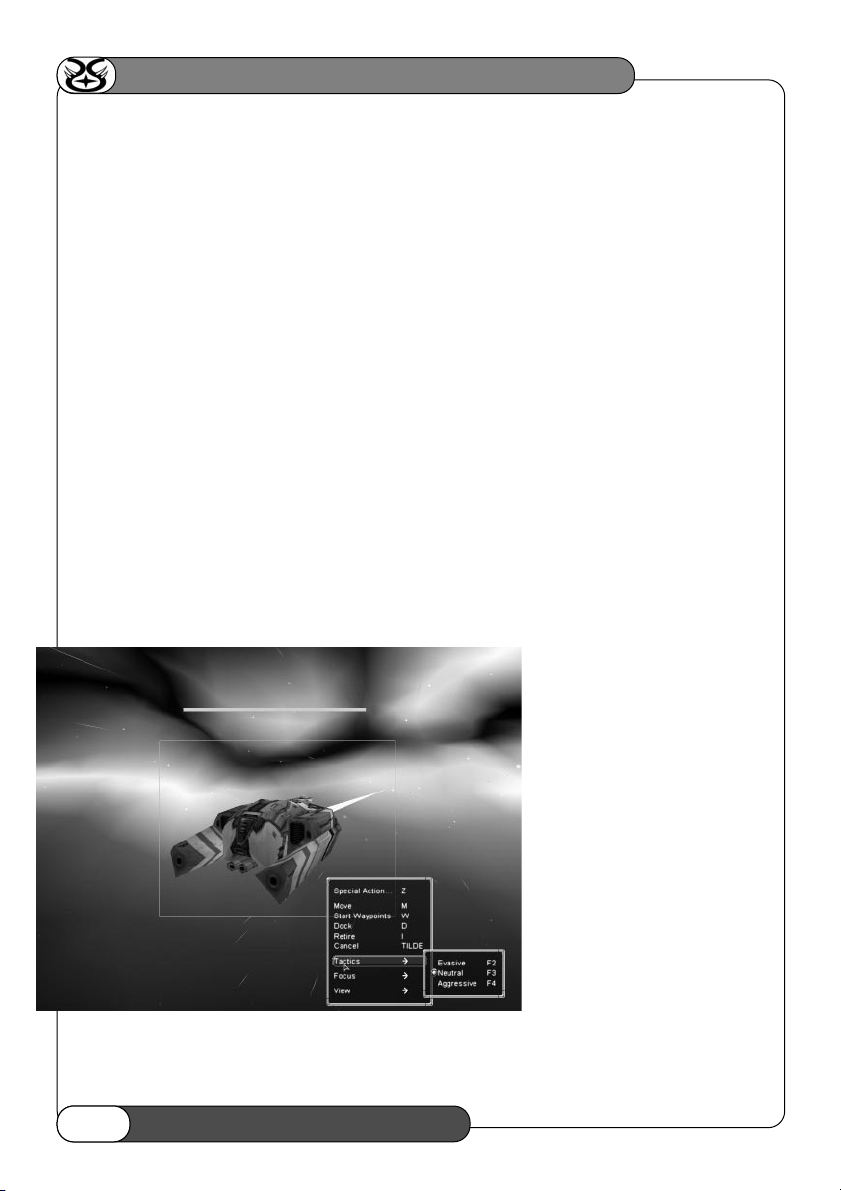

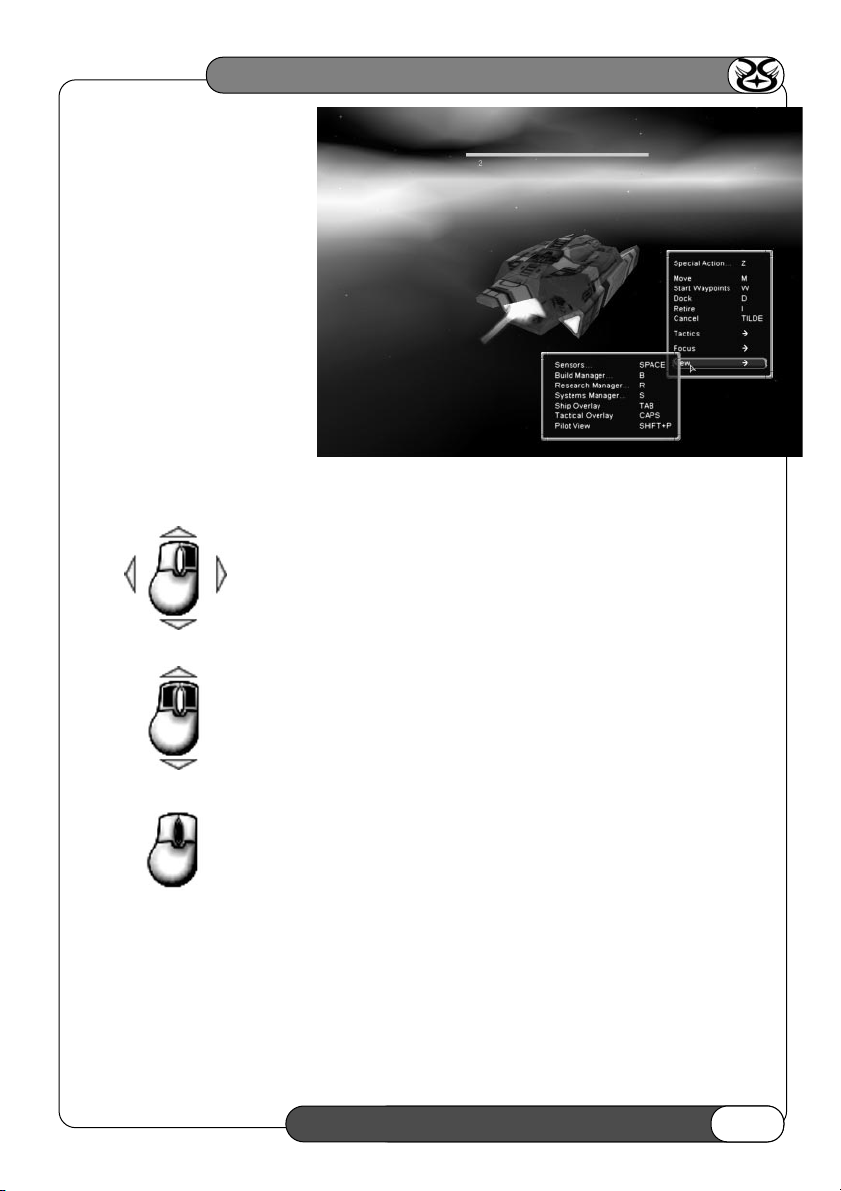

THE RIGHT-CLICK MENU

At any point during the game, you can get a detailed list of command options (some specific to the ships

selected) by right-clicking.

NOTE: When you have the context sensitive right-click enabled (by default), you cannot right-click with

the mouse pointer over some ships and objects in the display. This occurs when a special action icon is

present below the pointer. Simply move the mouse pointer until no icon is present beneath the pointer

and then press the right mouse button to bring up the desired menu.

The menu has many options that enable you to control the selected ships. Movement, formations, tactics,

and other commands can all be set via these options.

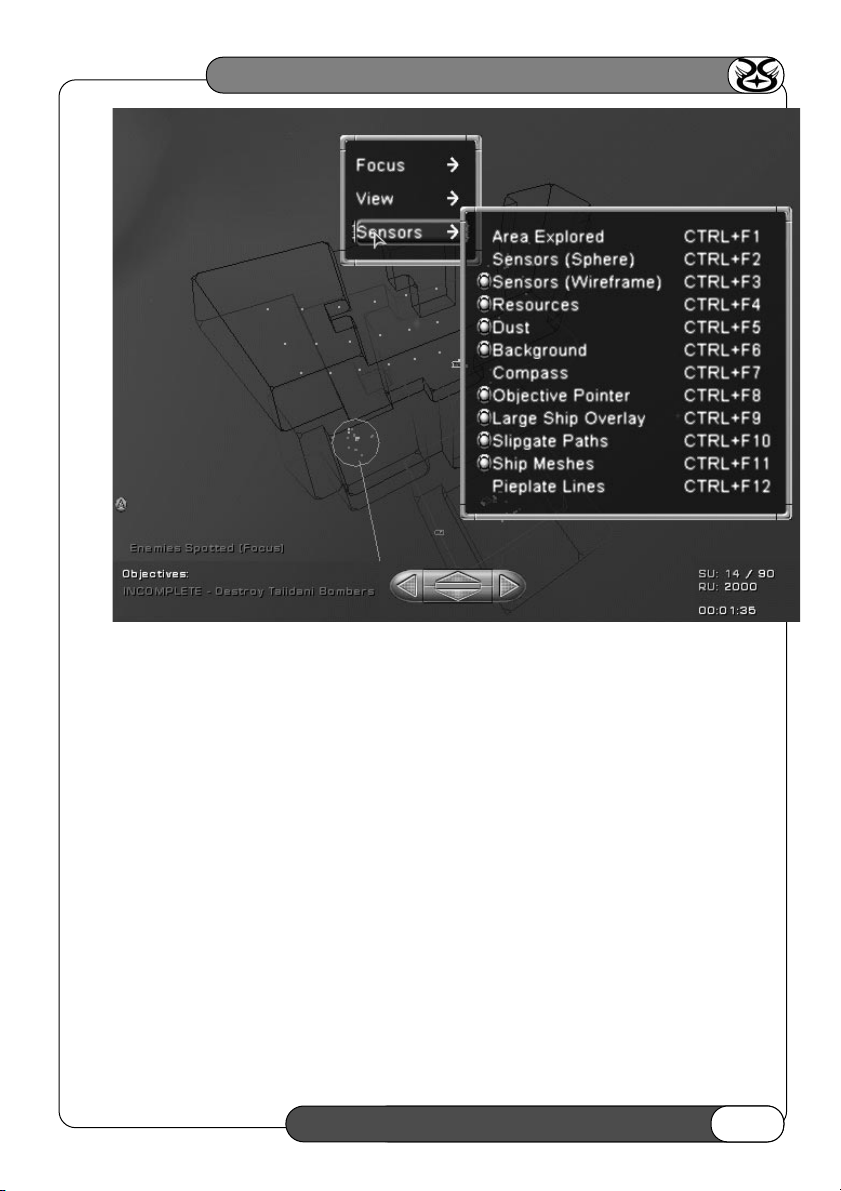

In the <VIEW> section of the

right-click menu, you can access

the manager screens (build,

research, systems, and sensors)

and turn on/off ship overlay,

tactical overlay, and pilot view.

2020

Page 21

All right-click menu options have

hotkey equivalents. These hotkeys

can be changed via the key binding

settings in the option menu.

CAMERA CONTROLS

Rotating

Hold down the right mouse button and drag the mouse.

Zooming

Hold down the left and right mouse buttons and drag the mouse forward or backward. OR:

If you are using a mouse with a wheel, this can be used to zoom as well..

Focusing

Select a ship and press the middle mouse button or the [F] key.

NOTE: Issuing the focus command a second time will make the camera zoom

in as close as possible.

OR: Call up the right-click menu and select <ON SELECTED> in the <FOCUS> section.

Focus on Ships in View

Press [ALT]+[F] keys. This focuses on all of your ships in the viewable area.

OR: Call up the right-click menu and select <ON SHIPS IN VIEW> in the <FOCUS> section.

Focus on Command Ship

Press the [HOME] key.

OR: Call up the right-click menu and select <ON COMMAND SHIP> in the <FOCUS> section.

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

21

TECHNICAL BRIEF + GAMEPLAY GUIDE

21

Page 22

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

Focus on Event

Press the [ENTER] key.

OR: Call up the right-click menu and select <ON EVENT> in the <FOCUS> section.

ALT Focusing

To focus on a ship without selecting it, hold down the [ALT] key and left-click on it.

Cancel Focus

Press the [DELETE] key. If you wish to go back to a focus you have cancelled, press the [INSERT] key.

SHIP SELECTION

All selection can be done in both the main view and in sensors manager.

Selecting

Place mouse pointer over desired ship and click the left mouse button to select it. NOTE: If you

left-click on a group of ships in formation, the first left-click will select them all, and a second

left-click will select just that ship. Also, if you have different types of ships selected, you can

left-click to select any ship type from the ships selected list in the top right of the screen.

Drag Selecting

Hold down the left mouse button and drag a box around the desired ships.

Selecting Everything

Press the [E] key.

De-Selecting

Left-click on empty space or press the [ESC] key.

Shift Selecting

To add ships to the selection, hold down [SHIFT] and click the left mouse button on the desired

ship(s). It’s also possible to hold down [SHIFT] and then drag-select the desired ship(s).

NOTE: You can also hold down [SHIFT] and left-click to select multiple types of ships from the ships selected

list in the top right of the screen, (if you already have different ship types selected).

2222

Page 23

Hotkey Grouping

Select the ships you wish to assign a hotkey to and then press [CTRL] + a number key (from 1-9). You may

then select that group at any time, regardless of where you are, simply by pressing its hotkey number. Pressing

it again will focus the camera on the ship(s) in that hotkey group.

Adding Ships to a Hotkey Group

Select the hotkey group with its number key and then use “Shift Selecting” to add ship(s) to the group. Once

this is done, reassign the entire group to the hotkey number with the “Hotkey Grouping” command.

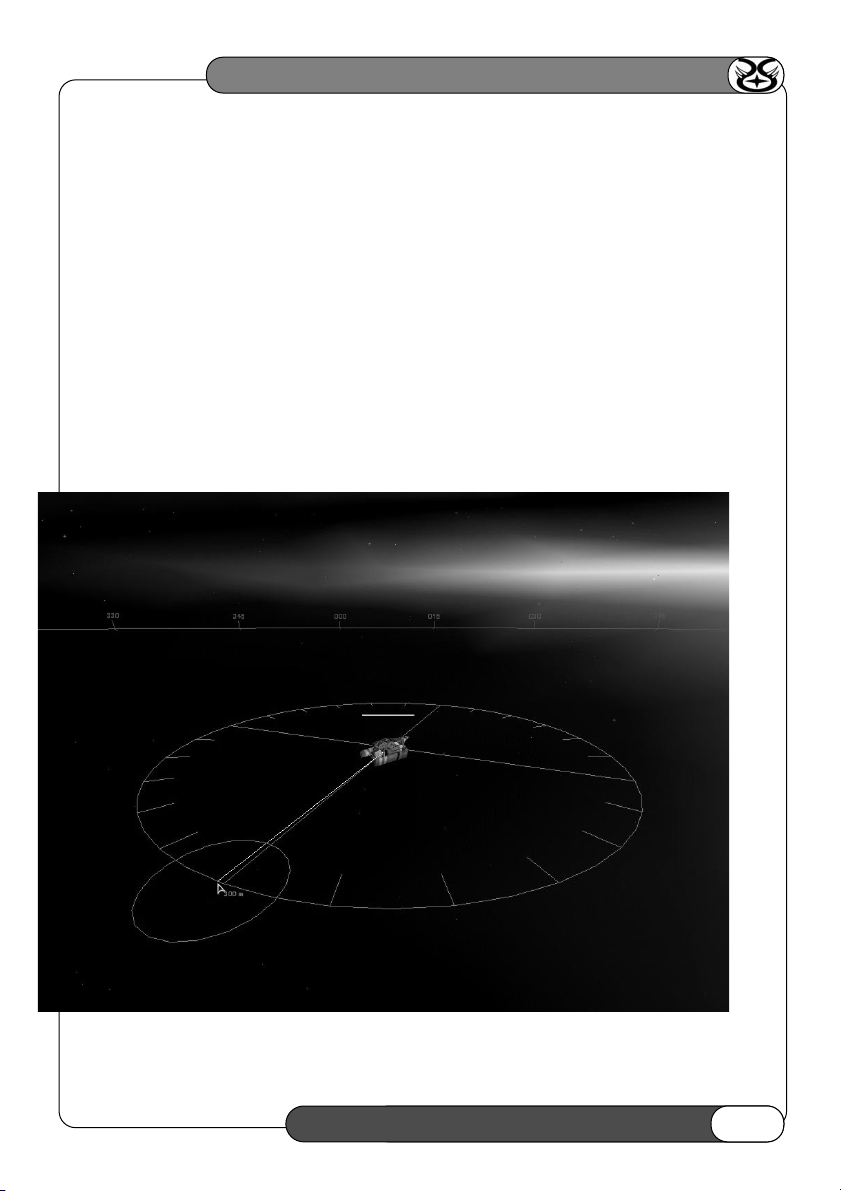

MOVEMENT

All movement can be done in the main view and sensors manager.

Horizontal Movement

Select a ship or group of ships and then press the [M] key. This will bring up the movement disk. Simply move

the mouse pointer to where you wish to go and click the left mouse button to issue the move order.

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

23

TECHNICAL BRIEF + GAMEPLAY GUIDE

23

Page 24

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

2424

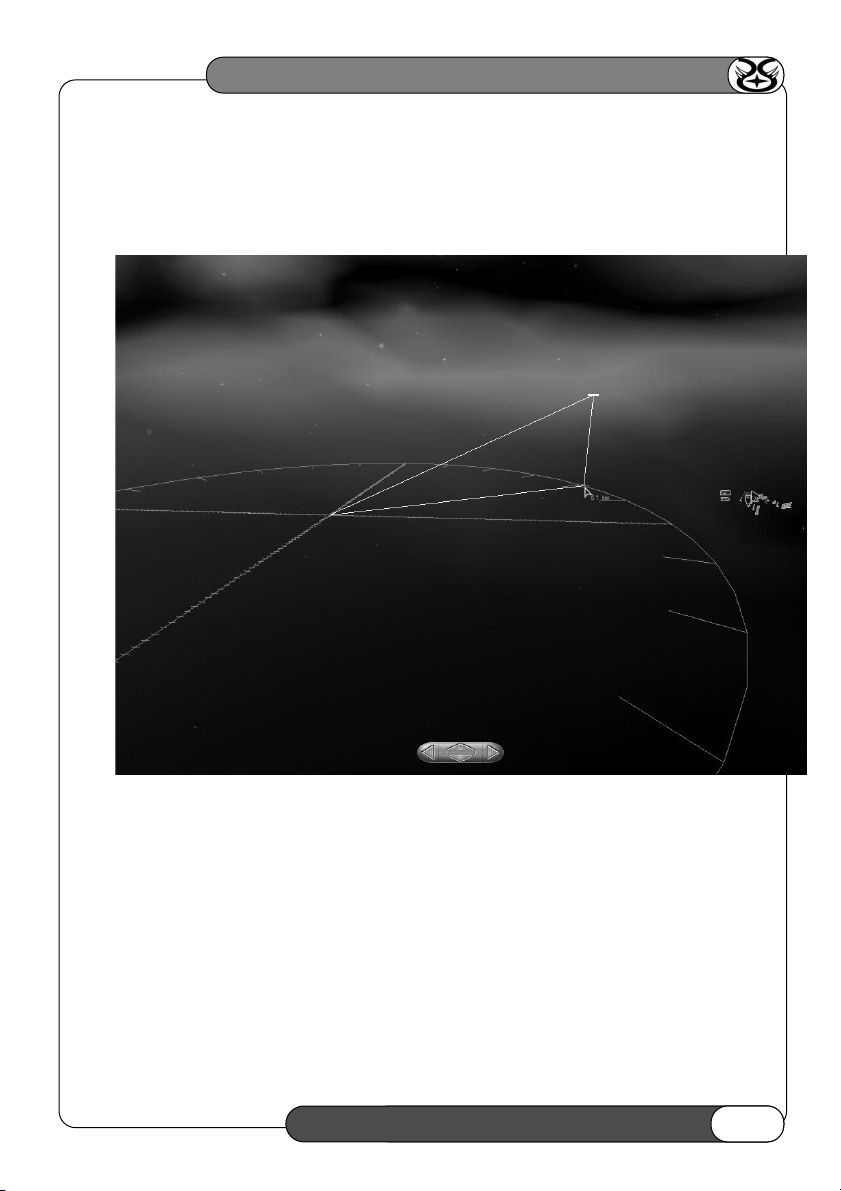

3D Movement

With the movement disk up, hold down [SHIFT] and drag the mouse to add elevation to your destination. As

before, clicking the left mouse button will issue the move order. NOTE: To cancel vertical movement and return

the movement disk to horizontal mode, press [CTRL]+[SHIFT].

Page 25

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

25

TECHNICAL BRIEF + GAMEPLAY GUIDE

25

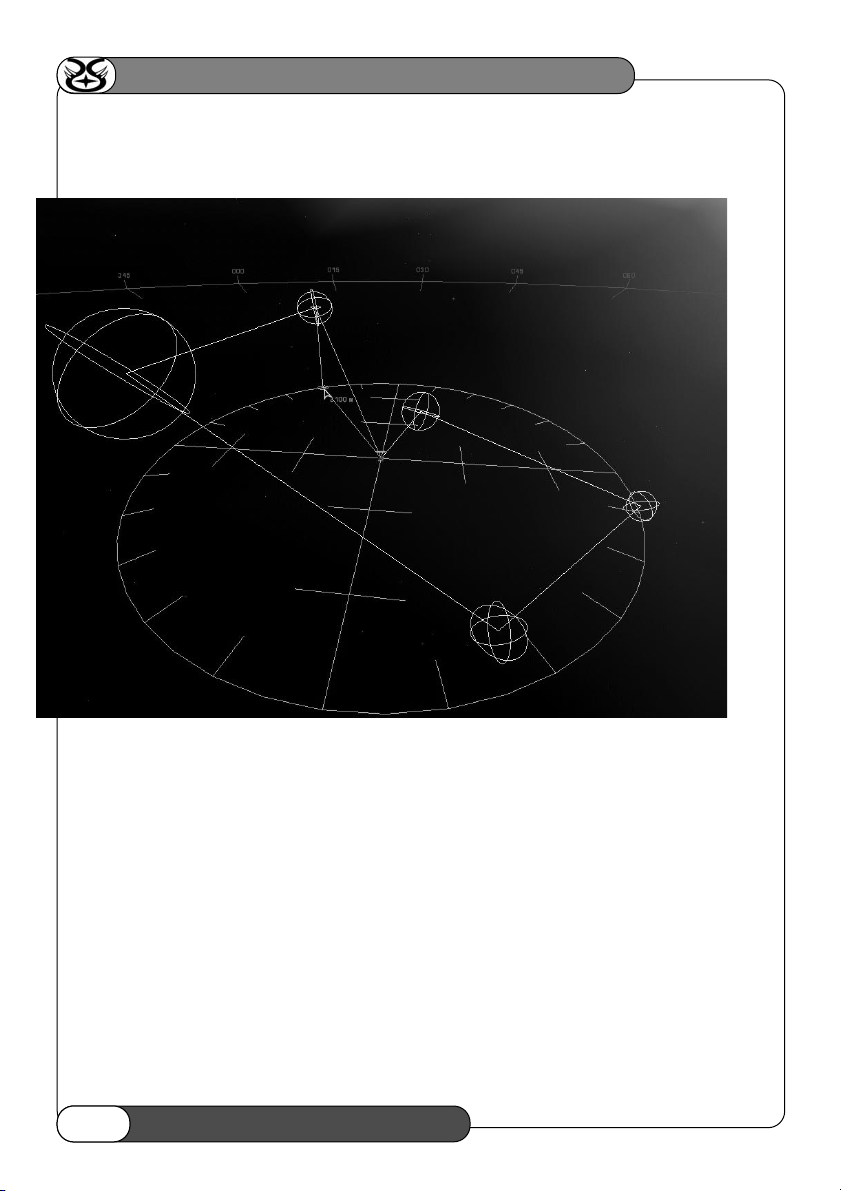

Moving in Sensors Manager

Like most other commands, movement can be done in the Sensors Manager. This is very useful when moving

long distances. Call up the Sensors Manager by pressing the [SPACE] key. Then use the [M] key to bring up the

movement disk and issue your move command, just as you would in the main game view.

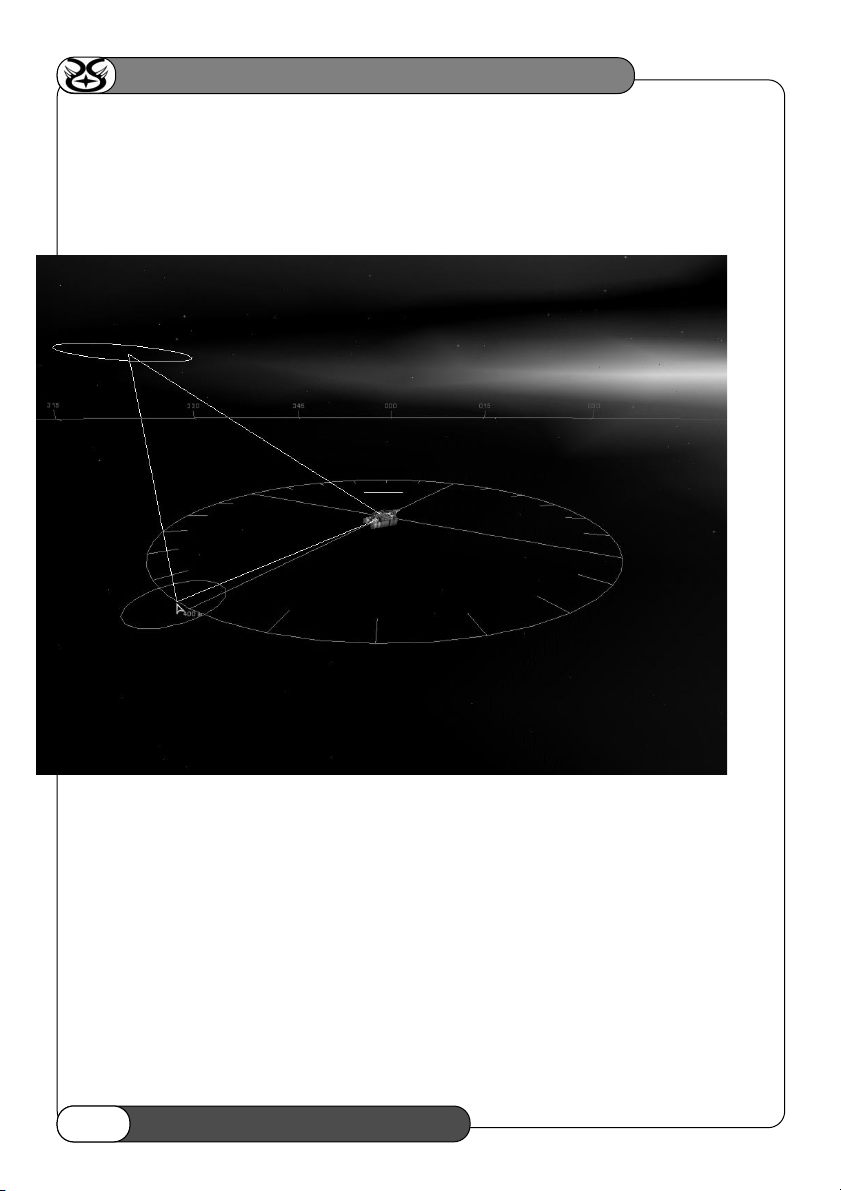

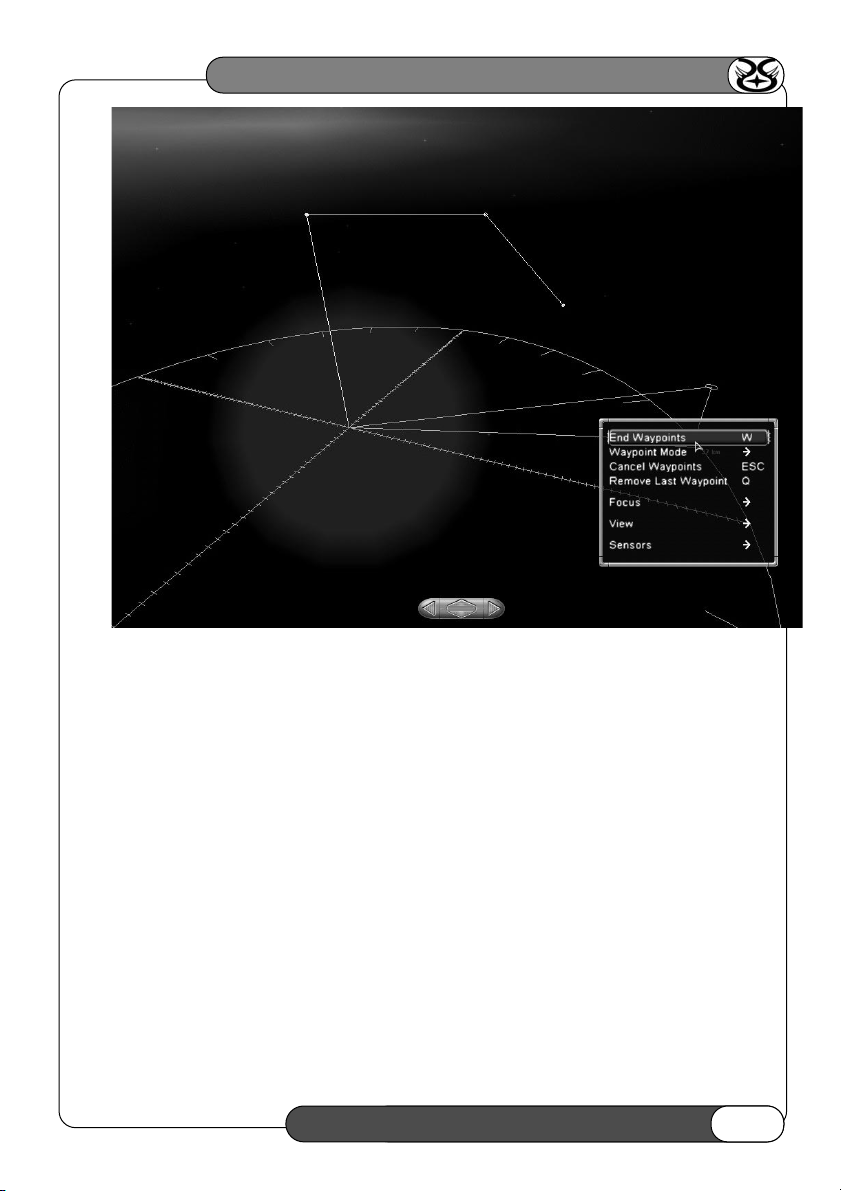

Waypoints

Waypoints are very useful for directing ships around enemy forces or setting up patrol routes. To start setting

waypoints, select some ships, and select the right-click menu option <START WAYPOINTS>.

OR: Select some ships and press [W].

Page 26

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

2626

You can now place each waypoint by pressing the left mouse button at the desired location. You can use the

[SHIFT] key to change vertical elevation of each waypoint, just as you would for a move command.

You can then finish placing waypoints by selecting the <END WAYPOINTS> option in the right-click menu.

OR: By pressing the [W] key again.

Page 27

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

27

TECHNICAL BRIEF + GAMEPLAY GUIDE

27

Waypoints have 3 modes that can be set via the right-click menu while placing waypoints, or with the following

hotkeys:

[SHIFT]+[Q] . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Linear

[SHIFT]+[W] . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Circular

[SHIFT]+[E] . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .End-to-End

Linear mode will make the ships go to the end of the path and stop. Circular mode will make the ships continuously

follow the path in a circular fashion, while End-to-End mode will ping-pong the ships from one end of the path to the

other. Use Circular and End-to-End waypoint paths in conjunction with aggressive tactics to set up effective patrols that

require little management.

Page 28

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

2828

COMBAT

Attacking

Move the mouse pointer over an enemy ship and click the left mouse button. NOTE: It is possible

that the attack icon will be replaced with a context sensitive special action icon. This does not mean

that a left-click will not attack, it just indicates that a right-click will perform a special action on that

target with the ships that you currently have selected, rather than bringing up the right-click menu.

Group Attacking

Hold down [CTRL] and drag a box around the targets with the left mouse button.

Force Attacking

Hold down [CTRL]+[SHIFT] and left-click on or bandbox the target(s). NOTE: Force attacking

can be used to attack asteroids and your own ships if necessary.

Moving While Attacking

Capital ships have a special ability to move while keeping their weapons bearing on an enemy ship. To do this,

give the Capital ship its attack order and then give it a movement order. The ship will move and continue to

attack until it is out of range of its target(s).

FORMATIONS AND TACTICS

Setting Formations

To set a formation, select the desired ships and bring up the right-click menu. From the <FORMATION>

section, you can choose one of seven formations.

OR: Formations also can be cycled through by pressing the [<] and [>] keys.

OR: Formations can be accessed directly via the F-keys:

F5 Delta

F6 Broad

F7 X

F8 Claw

F9 Wall

F10 Sphere

F11 Custom

Custom Formation

Custom formation lets you create your own formations. To create a custom formation, move your ships into the

desired position, select them all, then select <CUSTOM> from the right-click menu or press [F11].

Military Parade Formation

When you build ships, they come out of your Mothership or Carrier and go into Military Parade formation

with that ship. Frigates, corvettes, and fighters will go back into parade formation after docking with a

Carrier or Mothership.

Page 29

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

29

TECHNICAL BRIEF + GAMEPLAY GUIDE

29

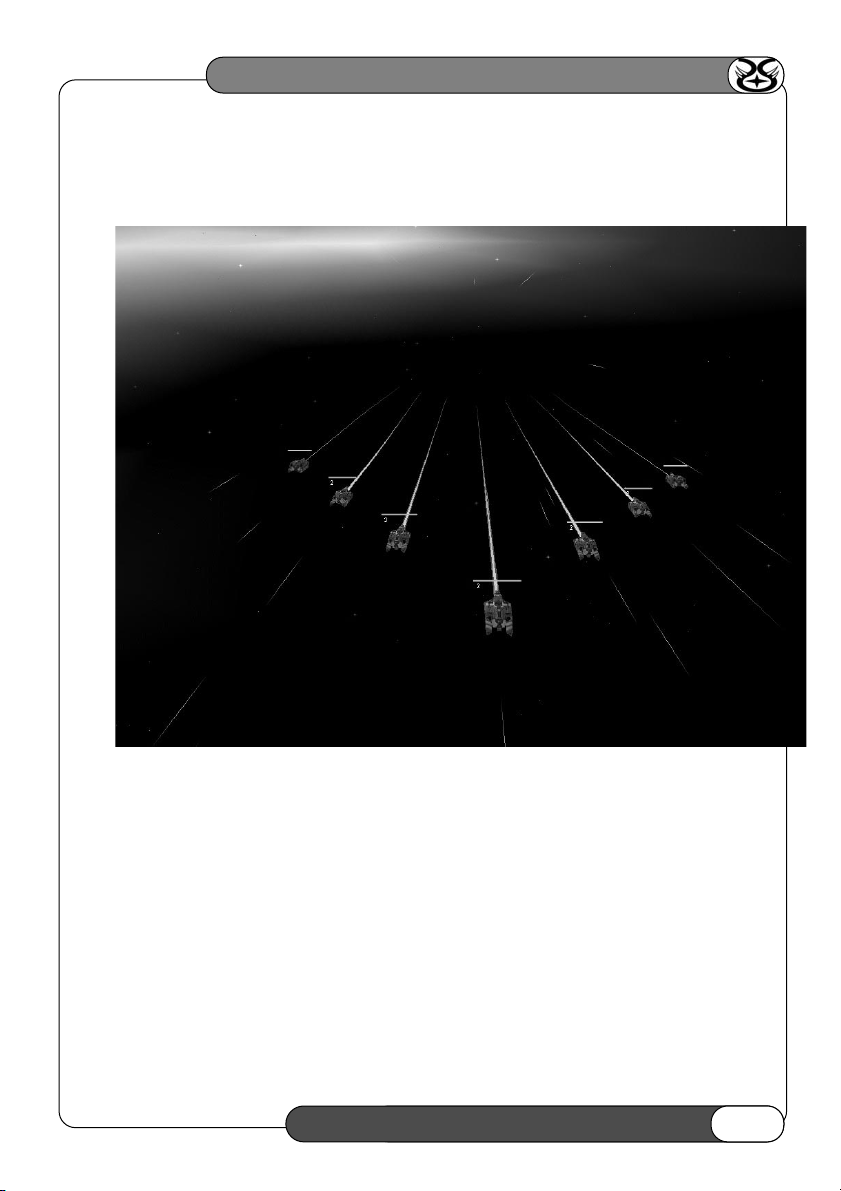

Delta

The standard flat triangle formation can organize groups of Strike Craft into effective squadrons, but it lacks the

flexibility and firepower concentration available to more three-dimensional formations.

Page 30

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

3030

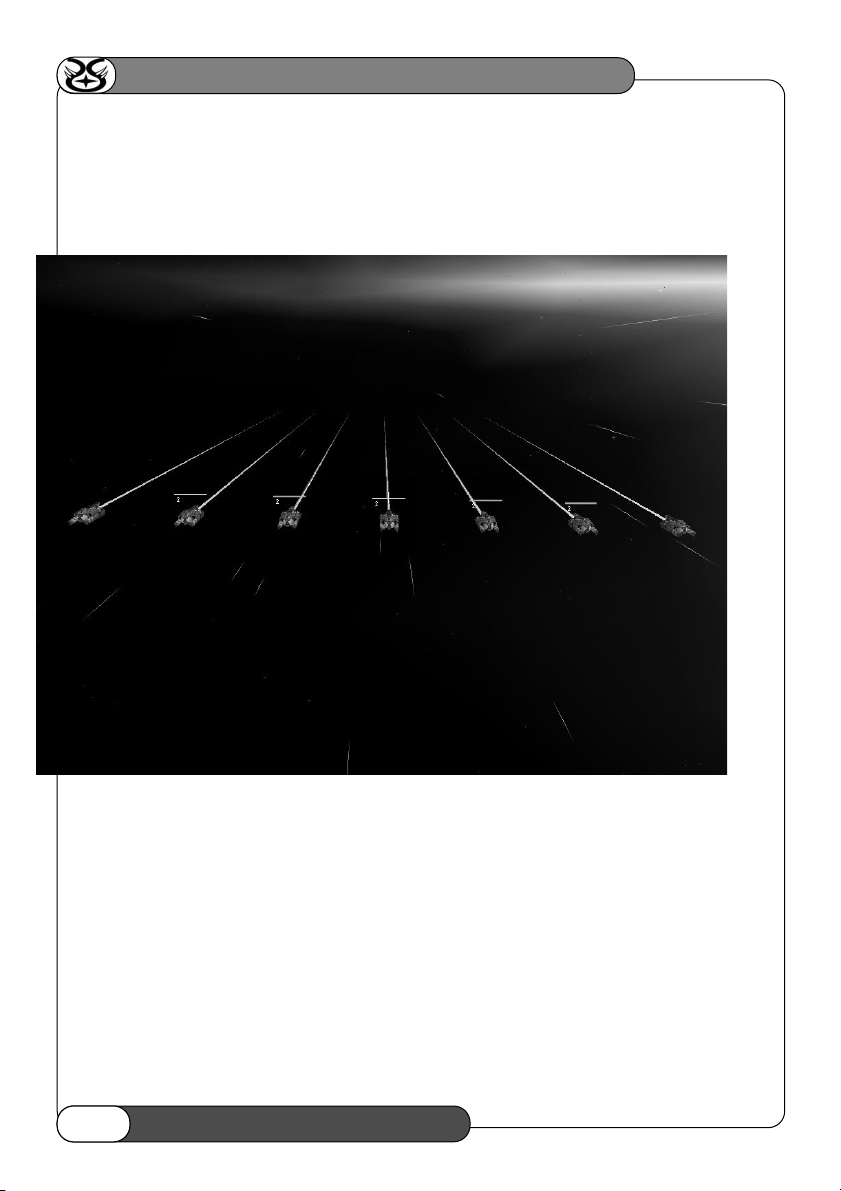

Broad

This flattened line is not effective for Strike Craft, as it disperses their firepower. It is more useful for

squadrons of Capital ships, where quick identification and selection of units is as important as concentrating

firepower. It is a useful formation to approach in, if you are planning to break ships off to strike at specific

targets once the battle is joined.

Page 31

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

31

TECHNICAL BRIEF + GAMEPLAY GUIDE

31

X

The flying X formation is an excellent Strike Craft formation, concentrating a large number of vessels into a

relatively small three-dimensional space. Its only drawback is that the dense formation makes individual ships

vulnerable to slow turret fire, which they might otherwise avoid if they were more widely dispersed.

Page 32

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

3232

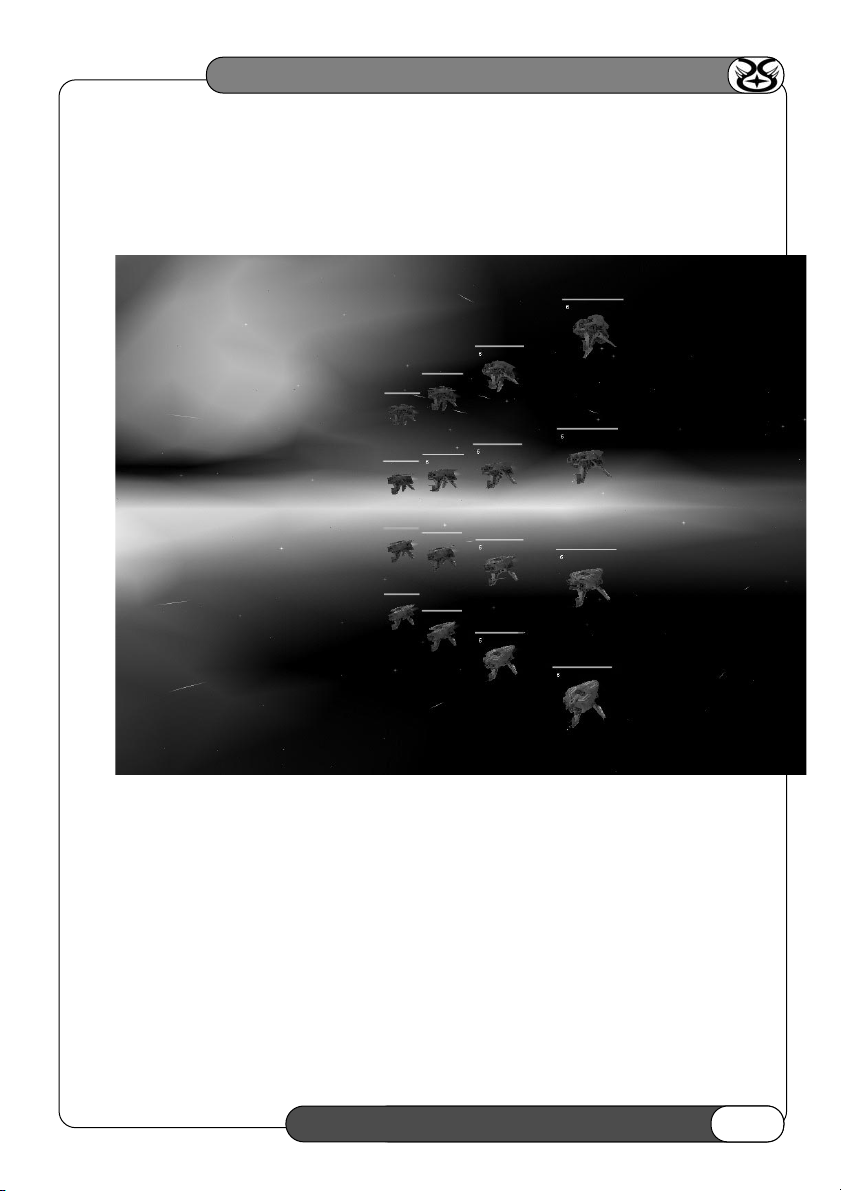

Claw

Like its namesake in nature, this formation is deadly when striking out at an individual target. The claw is a

superb formation for Strike Craft when they are targeting a Capital Ship. The four curving lines of Fighters make

concentrating firepower and envelopment deadly efficient. The only drawback is identifying and selecting single

ships inside this complex formation.

Page 33

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

33

TECHNICAL BRIEF + GAMEPLAY GUIDE

33

Wall

Most effective for Capital Ships, the wall formation allows larger vessels to concentrate firepower without

dangerously crowding each other. The wall is not a subtle formation, but gives large groups of big ships an

effective attack mode.

Page 34

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

Sphere

This is the deadliest of all formations, in terms of continuous firepower. Ships in this formation lose their

ability to perform complex flight maneuvers, but gain the ability to constantly fire at targets from every angle.

This is also an effective guarding formation, as it puts the vessel to be protected in the center of the sphere.

Setting Tactics

To change the tactics setting, select the desired ships and bring up the right-click menu. From the <TACTICS>

section you can choose one of three settings: Evasive, Neutral or Aggressive. The tactics setting can be increased

using the ] key and decreased using the [ key.

OR: Tactics can be accessed directly via the F-keys:

F2 Evasive

F3 Neutral

F4 Aggressive

3434

Page 35

Evasive Tactics

Evasive ships will not maintain formation when attacking, and thus are less likely to be hit by fire intended for

nearby wingmen. Evasive ships will also flee enemies that are attacking them, unless instructed specifically to

attack certain ships. Even when instructed to attack, an evasive ship will abort the attack if damaged severely

and return to dock for repairs at the nearest Carrier or Mothership. NOTE: Certain large ships cannot be set to

evasive, as they are too slow to flee enemies and/or cannot dock for repairs due to their size (Motherships,

Carriers, Dreadnoughts, Heavy Cruisers, Destroyers, and Processors).

Neutral Tactics

This is the normal stance for ships. Strike Craft set to neutral will perform evasive maneuvers while attacking

enemy ships, but will maintain specified formations. If no orders are issued and enemies are within weapons

range, ships in neutral will fire from their current position, but will not engage in full combat. All ships that have

just been built are launched with neutral tactics.

Aggressive Tactics

When ships are set to aggressive tactics, they will automatically attack any enemies within weapons range and

attack them until they or their enemies are destroyed. Aggressive ships on patrol will return to the patrol route

after they have destroyed any enemies they encounter. Commands (other than attack) issued to aggressive

ships while they are in the midst of battle will drop them to neutral tactics, so that they can leave the battle and

perform the command issued.w

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

35

TECHNICAL BRIEF + GAMEPLAY GUIDE

35

Page 36

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

OTHER COMMANDS

Upgrade (U key)

Select the ship(s) that you want to upgrade and then press the [U] key.

OR: Select the ship(s) you wish to upgrade, call up the right-click menu, and select the <UPGRADE> option.

This option will not be present if none of the ships selected can be upgraded.

Ships that can upgrade will have a solid blinking yellow circle to the right of their health bar when selected. Ships

can only be upgraded when certain technologies are researched.

Strike craft will automatically dock when instructed to upgrade, while larger ships can upgrade wherever they

are. When larger ships are instructed to upgrade, a tan colored bar will appear below their health bar; this

represents the progress of the upgrade. Ships cannot do anything else while they are upgrading.

Dock (D key)

Select the desired ship(s) and then right-click on the vessel you wish to dock with. A ship will

only dock with a vessel that has docking bays (the dock icon will be visible when the mouse

pointer is over it). NOTE: Some large ships cannot dock (Mothership, Carriers, Destroyers,

Dreadnoughts, Heavy Cruisers, and Processors)

OR: Bring up the right-click menu and select the <DOCK> command. This will cause the

selected ship(s) to dock with the nearest capable vessel.

OR: Press the [D] key. This will instruct your ships to dock with the nearest capable vessel.

Retire (I key)

Select the ships you wish to retire, call up the right-click menu, and select <RETIRE>. The selected ships will

dock and retire with the nearest capable vessel. Once docked, resource units representing a portion of the value

of that ship will be added to your total. Only ships that can dock can be retired.

Hyperspace (J key)

This command allows Capital Ships to perform hyperspace jumps. Just select the ships you wish to hyperspace,

bring up the right-click menu and select the <HYPERSPACE> command. The Sensors Manager and movement

disk will be brought up automatically. Left-click to set the hyperspace destination. The cost of the hyperspace

jump will be displayed near your cursor. If this cost turns red, you don’t have enough Resource Units to make

the jump.

Cancel Orders (~ key)

Select the desired ship(s), bring up the right-click menu and select the <CANCEL ORDERS> command.

OR: Select the desired ship(s) and press the [~] key.

Guard (G key)

Select the ships that you wish to put on guard duty, then hold down the [G] key and left-click on

or left bandbox the target(s) that you wish to guard. Ships will only move as fast as the minimum

velocity of any ship guarding it.

3636

Page 37

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

37

TECHNICAL BRIEF + GAMEPLAY GUIDE

37

Harvest (H key)

Select a Worker, move the mouse pointer over any resource and click the right mouse button.

OR: Bring up the right-click menu and select the <HARVEST> command. This will cause the

Worker to begin harvesting the nearest resource.

OR: Press the [H] key. This will also make the Worker find the nearest resource.

OR: Hold down the [Z] key and left-click on or left bandbox resources.

To harvest crystals, your Workers must be upgraded with salvage technology and your Command Ship (or Carrier

or Processor) must be upgraded with crystal harvesting technology. Instruct your Workers to salvage the crystal

(see special actions section below). It takes 2 Workers to tow a small crystal and 4 Workers to tow a large

crystal. Once a sufficient number of Workers have latched on to the crystal, it will be towed back to the nearest

crystal processing capable ship. If you do not have a ship with the crystal harvesting upgrade, then you will not

be able to issue a salvage command on a crystal.

Kamikaze (K key)

After giving a ship normal attack orders press the [K] key. Only Strike Craft can kamikaze.

Scuttle (SHIFT + S key)

Press the [SHIFT]+[S] keys once you have selected the ship(s) you wish to self-destruct. NOTE: You must issue

the scuttle command twice to confirm this unusual order.

Ship Overlay (TAB key)

Press the [TAB] key.

OR: Call up the right-click menu and select <SHIP OVERLAY> in the <VIEW> section.

Tactical Overlay (CAPS LOCK key)

Press the [CAPS LOCK] key.

OR: Call up the right-click menu and select <TACTICAL OVERLAY> in the <VIEW> section.

Pilot View (Shift key + P key)

Select one ship, then press [SHIFT]+[P] key. Your view is now that of the pilot. To return to regular view,

simply press [SHIFT]+[P] again.

OR: Call up the right-click menu and select <PILOT VIEW> in the <VIEW> section.

Pause (P key)

Press the [P] key at any time during gameplay to pause the game. NOTE: The camera is still fully active

(including focusing) while the game is paused, but no game commands can be issued.

Special Actions

You can call up a special action menu for your currently selected ships at any time by pressing the [Z] key.

Left-click on your choice of action in this menu. If a target is needed for the chosen action, then the closest valid

target will be selected.

OR: Select the <SPECIAL ACTION> option in the right-click menu to call up the special action menu.

If you want to choose a specific target, hold down the [Z] key while left-clicking on or left bandboxing the

Page 38

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

3838

desired target(s). A menu will pop up and you can choose which action to perform by left-clicking on it. Invalid

targets chosen for that action will be ignored. NOTE: Whenever choosing an action from the menu that pops up,

you will notice as your mouse pointer moves over each entry that the ships in your current selection which can

perform that action will have a box drawn around them. This is useful when you have various types of ships

selected.

OR: Place the mouse pointer over a desired target. An icon representing an available special action for your

currently selected ships will appear below the mouse pointer. You can now right-click to perform that action

(provided you haven’t disabled right-click context sensitive commands in the gameplay options).

Some ships do not gain the ability to perform certain special actions until they have been upgraded. For example:

a Worker cannot repair other ships until an engineering module has been built, repair technology has been

researched, and the Worker has been upgraded.

Some ships can perform more than one special action, and some ships have various modes for their special

action, which can be set in the special action menu that pops up when you press the [Z] key.

Below is a quick reference list of special actions for each ship. A more detailed explanation of each special

action is given afterward.

Somtaaw Ships Beast Ships

Recon None Recon None

Leech Leech Sentinel Shield

Sentinel Shield Acolyte Link

Acolyte Link ACV Unlink, EMP

ACV Unlink, EMP Interceptor None

Mimic Link, Mimic Cloaked Fighter Cloak

MCV Unlink, Mimic Attack Bomber None

Ramming Frigate Ram Heavy Corvette None

Multi-Beam Frigate None Multi-Gun Corvette None

Hive Frigate Swarm Missile Corvette None

Destroyer None Cruise Missile None

Dreadnought Repulse Ramming Frigate Ram

Carrier None Multi-Beam Frigate None

Worker Harvest, Repair, Salvage Hive Frigate Swarm

Processor None Ion Array Frigate Cloak

Mothership Siege Cannon DFG Frigate None

Heavy Cruiser Infect

Carrier Infect

Worker Harvest, Repair, Salvage

Processor None

Mothership Infect

Page 39

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

39

TECHNICAL BRIEF + GAMEPLAY GUIDE

39

Repair

When instructed to repair, a Worker will fly within range of the closest target chosen and begin

repairing it. If none of the targets are damaged, the Worker will remain close to the ships and

repair them if they do become damaged.

Leech

When instructed to leech, a Leech will clamp onto a target’s hull. It will then do one of three

things:

1) Spy. Harmless to enemy ship, but enables owner of leech to see what the enemy is up to.

2) Vent. Slowly damage enemy ship by eating though hull and dumping waste into space.

Will continue to do this until the enemy ship is destroyed.

3) Leech. Slowly damage enemy ship by eating through hull, but return gathered material to

nearest Mothership, Carrier, or Processor for resource unit (RU) gain. After dropping off

material, it will return to the same target to gather more material (RUs). Once the enemy

has been reduced to near destruction, the Leech will stop damaging that ship and jump to a

new target, or return gathered material and go into military parade formation.

The mode of leeching can be controlled via the special action menu that pops up after pressing the [Z] key (with

a Leech currently selected).

Shield

When instructed to shield a specific target, the selected Sentinels will attempt to form a sphere

around the target. 12 Sentinels are needed to form a complete sphere. All 12 Sentinels must be

upgraded with at least Force Field Level 1 technology. If less than 12 properly upgraded Sentinels

are instructed to make a shield, they will try to form a sphere that favors the forward direction of

the target ship. If a target is not given, Sentinels will form a wall by themselves.

The shield will not be formed until the Sentinels are close to their desired position around the target, or close

to each other (when forming a wall). Once the shield is active, Sentinels cannot be controlled regularly, and will

remain locked in formation around the target. To regain control of the Sentinels, select them, open the special

action menu and select the <UNLINK FORCE FIELD> option. The Sentinels can now be controlled again.

Sentinels have 3 different levels of effectiveness. When they are upgraded to Force Field Level 3, the shield they

generate will be able to withstand a lot more firepower than Level 1 shields. Each Sentinel that is involved in

forming a shield has a blue bar beneath its health when selected, which represents how strong their part of the

shield is. As soon as this bar reaches nothing, that part of the shield will collapse and the Sentinel will be

vulnerable to enemy fire until it can recharge and reform its part of the shield.

Link

Select 2 or more Acolytes or Mimics that have been upgraded with linking technology. As many pairs of valid ships

in your selection as possible will move together and link to form either ACV or MCV pairs (depending on whether

Acolytes or Mimics were involved). If you notice ships having difficulty linking, it might be due to nearby ships that

are interfering with their maneuvers. Simply move the interfering ships away and the linking process will continue

unimpaired. It is also advisable to avoid linking ships while in the heat of battle, as enemy ships and weapons fire

will impede the linking process.

Page 40

HOMEWORLD: CATACLYSM

4040

Unlink

Select any ACVs or MCVs and issue this command. ACVs will separate into 2 Acolytes and MCVs will separate into

2 Mimics.

EMP

The EMP command can be issued on EMP-upgraded ACVs in two ways. You can use Z left-click,

Z left bandbox, or a context sensitive right mouse click to choose a target; you can also issue an

EMP command via the right-click menu <EMP> option or hotkey.

If a target is chosen, the selected ACVs will move within range and discharge an EMP blast that will

stun the target. The length of time that the enemy ship is stunned depends on the number of ACVs involved in

the attack and the size of the target. 10 ACVs will give the EMP blast its maximum effect.

If a target is not chosen, the selected ACVs will fire an EMP blast immediately if at least one valid target is

within range.

An ACV must recharge its EMP weapon. This recharge time is represented by a blue bar below its health, when

selected. An ACV cannot be involved in an EMP attack if this bar is not full.

Mimic

Mimics and MCVs can holographically emulate the appearance of friendly ships, enemy ships, and asteroids.

You can choose which category to mimic via the special action menu <SELECT MIMIC> section. This section

has a list of all players and an asteroid category. Left-click on the desired choice.

After choosing a category, you can choose exactly what class of ship to emulate via the <MIMIC> section in the

special action menu. This section will list all available ships that you can mimic for that category. Left-click on

the desired choice.

The Mimic or MCV will now transform into the ship or asteroid selected. If you initiated the mimic operation

outside of the visible space for that enemy, you can now infiltrate their forces without detection, unless they have

a Recon or Sentinel nearby that has Advanced Sensors. Small dots above the health bar for the Mimic or MCV

represent which players that ship is currently stealthy with. If the first dot on the left is green, then the ship is

capable of infiltrating player 1’s fleet. If the third dot is red, then player 3’s fleet is aware that this ship is an

enemy. In single player, you are player 1 and any enemy in the current mission is player 2.

When a Mimic or MCV emulates an asteroid, enemy Workers that do not have Recons or Sentinels nearby with

advanced sensors will treat the fake asteroids as real ones. Once they get close, the Mimic will kamikaze into

the Worker, doing substantial damage. This damage is increased if the Mimic or MCV has been upgraded with

Quantum Explosive Charges.

Mimics can emulate corvettes and all classes smaller, while MCVs can emulate frigates and all classes smaller.

Page 41

Ram

Ramming frigates are capable of ramming other ships, both to cause damage and to push them

away from a battle. Once instructed to ram, a Ramming Frigate will move into position and then

make its attack run.

Once it collides with the target, it will remain locked onto the victim until it has pushed it for

approximately 20 seconds, after which it will disengage to recharge its engines. After recharging, it will reposition

itself for another attack run and ram again. While pushing an enemy ship, the Ramming Frigate will also engage

a cutting torch weapon to inflict damage on the hull.

A Ramming Frigate’s effectiveness is greatly improved once it has been upgraded with Afterburner technology (in

multiplayer, you cannot build Ramming Frigates unless you have researched Afterburner technology). A

Ramming Frigate’s cutting torch is also more effective once upgraded with Advanced Ion Cannon technology.

It is possible to ram crystals, thus pushing them around and/or destroying them.

Ramming is a very effective way to take large, dangerous enemies away from your fleet, where they can be

attacked without the support of their escorts.

Swarm

Hive Frigates are equipped with 6 swarmers, which can be launched to attack enemy ships. These

Swarmers are small fighter craft; that continue to attack enemy ships until instructed to return to

the Hive Frigate (via [SHIFT]+[TILDE]) or until the enemy is destroyed. Swarmers are very fast,

able to evade most projectile fire. Their size also makes it impossible for energy weapons to track

them.

If a Swarmer is destroyed, a new one will be constructed within the Hive Frigate and launched immediately.

Note that it is possible to attack a target with the Hive Frigate’s conventional weapons while its Swarmers

are attacking another target entirely.

Repulse

Once upgraded, a Dreadnought can emit a repulse blast that will push and slightly damage enemy ships nearby.

Once fired, the repulse blast expands in a sphere from the Dreadnought. This weapon is capable of taking out small

craft, but is intended to push larger enemies away and give the Dreadnought time to maneuver and bring its

weapons to bear.

Salvage

Once upgraded, Workers can be instructed to salvage both enemy ships and derelicts. Enemy ships

must be substantially damaged before they can be salvaged. If the ship chosen for salvage is not