Page 1

AppleScript Language Guide

English Dialect

Page 2

Apple Computer, Inc.

© 1996 Apple Computer, Inc.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication or the

software described in it may be

reproduced, stored in a retrieval

system, or transmitted, in any form

or by any means, mechanical,

electronic, photocopying, recording,

or otherwise, without prior written

permission of Apple Computer, Inc.

Printed in the United States

of America.

The Apple logo is a trademark of

Apple Computer, Inc. Use of the

“keyboard” Apple logo (OptionShift-K) for commercial purposes

without the prior written consent of

Apple may constitute trademark

infringement and unfair competition

in violation of federal and state laws.

No licenses, express or implied, are

granted with respect to any of the

technology described in this book.

Apple retains all intellectual

property rights associated with the

technology described in this book.

This book is intended to assist

application developers to develop

applications only for Apple

Macintosh computers.

Apple Computer, Inc.

20525 Mariani Avenue

Cupertino, CA 95014

408-996-1010

Apple, the Apple logo, AppleTalk,

HyperCard, HyperTalk, LaserWriter,

and Macintosh are trademarks of

Apple Computer, Inc., registered

in the United States and other

countries.

AppleScript, Finder, Geneva

and System 7 are trademarks of

Apple Computer, Inc.

Adobe Illustrator and PostScript are

trademarks of Adobe Systems

Incorporated, which may be

registered in certain jurisdictions.

FrameMaker is a registered

trademark of Frame Technology

Corporation.

Helvetica and Palatino are registered

trademarks of Linotype Company.

FileMaker is a registered trademark

of Claris Corporation.

ITC Zapf Dingbats is a registered

trademark of International Typeface

Corporation.

Microsoft is a registered trademark

of Microsoft Corporation.

Simultaneously published in the

United States and Canada.

LIMITED WARRANTY ON MEDIA

AND REPLACEMENT

If you discover physical defects in the

manuals distributed with an Apple

product, Apple will replace the manuals

at no charge to you, provided you return

the item to be replaced with proof of

purchase to Apple or an authorized

Apple dealer during the 90-day period

after you purchased the software. In

addition, Apple will replace damaged

manuals for as long as the software is

included in Apple’s Media Exchange

program. See your authorized Apple

dealer for program coverage and details.

In some countries the replacement

period may be different; check with

your authorized Apple dealer.

ALL IMPLIED WARRANTIES ON

THIS MANUAL, INCLUDING

IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF

MERCHANTABILITY AND FITNESS FOR A

PART ICULAR PURPOSE, ARE

LIMITED IN DURATION TO NINETY

(90) DAYS FROM THE DATE OF THE

ORIGINAL RETAIL PURCHASE OF

THIS PRODUCT.

Even though Apple has reviewed this

manual, APPLE MAKES NO

WARRANTY OR REPRESENTATION,

EITHER EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, WITH

RESPECT TO THIS MANUAL, ITS

QUALITY, ACCURACY, MERCHANTABILITY, OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. AS A RESULT, THIS

MANUAL IS SOLD “AS IS,” AND

YOU, THE PURCHASER, ARE

ASSUMING THE ENTIRE RISK AS TO

ITS QUALITY AND ACCURACY.

IN NO EVENT WILL APPLE BE

LIABLE FOR DIRECT, INDIRECT,

SPECIAL, INCIDENTAL, OR

CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES

RESULTING FROM ANY DEFECT OR

INACCURACY IN THIS MANUAL,

even if advised of the possibility of such

damages.

THE WARRANTY AND REMEDIES

SET FORTH ABOVE ARE EXCLUSIVE

AND IN LIEU OF ALL OTHERS, ORAL

OR WRITTEN, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED.

No Apple dealer, agent, or employee is

authorized to make any modification,

extension, or addition to this warranty.

Some states do not allow the exclusion

or limitation of implied warranties or

liability for incidental or consequential

damages, so the above limitation or

exclusion may not apply to you. This

warranty gives you specific legal rights,

and you may also have other rights

which vary from state to state.

Page 3

Contents

Figures and Tables xiii

Preface About This Guide

Audience xv

Organization of This Guide xvi

Sample Applications and Scripts xvii

For More Information xviii

Getting Started xviii

Scripting Additions xviii

Other AppleScript Dialects xviii

Scriptable Applications xviii

Conventions Used in This Guide xix

Part 1 Introducing AppleScript

xv

1

Chapter 1 AppleScript, Scripts, and Scriptable Applications

What Is AppleScript? 3

What Can You Do With Scripts? 5

Automating Activities 5

Integrating Applications 7

Customizing Applications 7

Who Runs Scripts, and Who Writes Them? 9

Special Features of AppleScript 10

What Applications Are Scriptable? 11

3

iii

Page 4

Chapter 2 Overview of AppleScript

How Does AppleScript Work? 14

Statements 14

Commands and Objects 17

Dictionaries 18

Values 20

Expressions 21

Operations 21

Variables 22

Script Objects 23

Scripting Additions 23

Dialects 24

Other Features and Language Elements 24

Continuation Characters 25

Comments 26

Identifiers 27

Case Sensitivity 28

Abbreviations 29

Compiling Scripts With the Script Editor 30

13

Part 2 AppleScript Language Reference

Chapter 3 Values

Using Value Class Definitions 33

Literal Expressions 36

Properties 36

Elements 37

Operators 37

Commands Handled 37

Reference Forms 38

Coercions Supported 38

iv

33

31

Page 5

Value Class Definitions 38

Boolean 40

Class 41

Constant 42

Data 43

Date 43

Integer 47

List 48

Number 52

Real 53

Record 54

Reference 57

String 60

Styled Text 64

Text 66

Coercing Values 67

Chapter 4 Commands

Types of Commands 71

Application Commands 72

AppleScript Commands 73

Scripting Addition Commands 74

User-Defined Commands 76

Using Command Definitions 77

Syntax 78

Parameters 78

Result 79

Examples 79

Errors 79

Using Parameters 80

Parameters That Specify Locations 80

Coercion of Parameters 81

Raw Data in Parameters 81

Using Results 82

Double Angle Brackets in Results and Scripts 83

71

v

Page 6

Command Definitions 84

Close 87

Copy 88

Count 92

Data Size 97

Delete 98

Duplicate 99

Exists 99

Get 100

Launch 103

Make 105

Move 106

Open 107

Print 108

Quit 109

Run 110

Save 112

Set 113

Chapter 5 Objects and References

Using Object Class Definitions 119

Properties 120

Element Classes 120

Commands Handled 120

Default Value Class Returned 122

References 122

Containers 123

Complete and Partial References 124

Reference Forms 125

Arbitrary Element 126

Every Element 127

Filter 129

ID 130

Index 131

Middle Element 133

vi

119

Page 7

Name 134

Property 135

Range 136

Relative 139

Using the Filter Reference Form 140

References to Files and Applications 143

References to Files 144

References to Applications 146

References to Local Applications 147

References to Remote Applications 148

Chapter 6 Expressions

Results of Expressions 149

Variables 150

Creating Variables 150

Using Variables 152

The “A Reference To” Operator 153

Data Sharing 154

Scope of Variables 155

Predefined Variables 156

Script Properties 156

Defining Script Properties 157

Using Script Properties 157

Scope of Script Properties 158

AppleScript Properties 158

Text Item Delimiters 158

Reference Expressions 160

Operations 161

Operators That Handle Operands of Various Classes 168

Equal, Is Not Equal To 168

Greater Than, Less Than 172

Starts With, Ends With 173

Contains, Is Contained By 175

Concatenation 177

Operator Precedence 178

Date-Time Arithmetic 180

149

vii

Page 8

Chapter 7 Control Statements

Characteristics of Control Statements 184

Tell Statements 185

Tell (Simple Statement) 188

Tell (Compound Statement) 189

If Statements 190

If (Simple Statement) 192

If (Compound Statement) 193

Repeat Statements 194

Repeat (forever) 197

Repeat (number) Times 198

Repeat While 199

Repeat Until 200

Repeat With (loopVariable) From (startValue) To (stopValue) 201

Repeat With (loopVariable) In (list) 202

Exit 204

Try Statements 204

Kinds of Errors 205

How Errors Are Handled 206

Writing a Try Statement 206

Try 207

Signaling Errors in Scripts 210

Error 210

Considering and Ignoring Statements 213

Considering/Ignoring 214

With Timeout Statements 217

With Timeout 218

With Transaction Statements 219

With Transaction 219

183

Chapter 8 Handlers

Using Subroutines 221

Types of Subroutines 223

Scope of Subroutine Calls in Tell Statements 224

Checking the Classes of Subroutine Parameters 225

viii

221

Page 9

Recursive Subroutines 225

Saving and Loading Libraries of Subroutines 226

Subroutine Definitions and Calls 228

Subroutines With Labeled Parameters 229

Subroutine Definition, Labeled Parameters 229

Subroutine Call, Labeled Parameters 230

Examples of Subroutines With Labeled Parameters 232

Subroutines With Positional Parameters 235

Subroutine Definition, Positional Parameters 235

Subroutine Call, Positional Parameters 236

Examples of Subroutines With Positional Parameters 238

The Return Statement 239

Return 240

Command Handlers 241

Command Handler Definition 241

Command Handlers for Script Applications 243

Run Handlers 243

Open Handlers 246

Handlers for Stay-Open Script Applications 247

Idle Handlers 248

Quit Handlers 249

Interrupting a Script Application’s Handlers 250

Calling a Script Application 251

Scope of Script Variables and Properties 252

Scope of Properties and Variables Declared at the Top Level

of a Script 254

Scope of Properties and Variables Declared in a Script Object 258

Scope of Variables Declared in a Handler 263

Chapter 9 Script Objects

About Script Objects 265

Defining Script Objects 267

Sending Commands to Script Objects 268

Initializing Script Objects 269

Inheritance and Delegation 271

265

ix

Page 10

Defining Inheritance 271

How Inheritance Works 272

The Continue Statement 277

Using Continue Statements to Pass Commands to Applications 280

The Parent Property and the Current Application 281

Using the Copy and Set Commands With Script Objects 283

Appendix A The Language at a Glance

Commands 289

References 294

Operators 296

Control Statements 299

Handlers 301

Script Objects 303

Variable and Property Assignments and Declarations 303

Predefined Variables 304

Constants 305

Placeholders 307

289

Appendix B Scriptable Text Editor Dictionary

About Text Objects 313

Elements of Text Objects 314

Special Properties of Scriptable Text Editor Text Objects 314

Text Styles 315

AppleScript and Non-Roman Script Systems 317

Scriptable Text Editor Object Class Definitions 318

Application 318

Character 321

Document/Window 323

File 328

Insertion Point 329

Paragraph 331

Selection 334

Text 336

313

x

Page 11

Text Item 339

Text Style Info 341

Window 342

Word 342

Scriptable Text Editor Commands 345

Copy 347

Cut 348

Data Size 349

Duplicate 349

Make 350

Move 351

Open 351

Paste 351

Revert 352

Save 353

Select 354

Scriptable Text Editor Errors 355

Appendix C Error Messages

Operating System Errors 358

Apple Event Errors 359

Apple Event Registry Errors 361

AppleScript Errors 362

Glossary

Index

363

371

357

xi

Page 12

Page 13

Figures and Tables

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

AppleScript, Scripts, and Scriptable Applications

Figure 1-1 Changing text style with the mouse and with a script 4

Figure 1-2 A script that performs a repetitive action 6

Figure 1-3 A script that copies information from one application to another 8

Figure 1-4 Different ways to run a script 9

Overview of AppleScript

Figure 2-1 How AppleScript works 15

Figure 2-2 How AppleScript gets the Scriptable Text Editor dictionary 20

13

3

Values 33

Figure 3-1 Value class definition for lists 34

Figure 3-2 Coercions supported by AppleScript 69

Table 3-1 AppleScript value class identifiers 39

Commands

Figure 4-1 Command definition for the Move command 77

Figure 4-2 The Scriptable Text Editor document “simple” 95

71

Chapter 5

Table 4-1 Standard application commands defined in this chapter 85

Table 4-2 AppleScript commands defined in this chapter 86

Objects and References

Figure 5-1 The Scriptable Text Editor’s object class definition for

paragraph objects 121

Figure 5-2 The Scriptable Text Editor document “simple” 137

Table 5-1 Reference forms 126

Table 5-2 Boolean expressions and tests in Filter references 142

119

xiii

Page 14

Chapter 6

Expressions

Table 6-1 AppleScript operators 163

Table 6-2 Operator precedence 179

149

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Appendix A

Handlers

Figure 8-1 Scope of property and variable declarations at the top level

Figure 8-2 Scope of property and variable declarations at the top level

Figure 8-3 Scope of variable declarations within a handler 263

Script Objects

Figure 9-1 Relationship between a simple child script and its parent 273

Figure 9-2 Another child-parent relationship 273

Figure 9-3 A more complicated child-parent relationship 274

The Language at a Glance

Table A-1 Command syntax 290

Table A-2 Reference form syntax 294

Table A-3 Container notation in references 296

Table A-4 Operators 297

Table A-5 Control statements 300

Table A-6 Handler definitions and calls 302

Table A-7 Script objects 303

Table A-8 Assignments and declarations 304

Table A-9 Predefined variables 305

Table A-10 Constants defined by AppleScript 305

Table A-11 Placeholders used in syntax descriptions 308

221

of a script 254

of a script object 258

265

289

Appendix B

xiv

Scriptable Text Editor Dictionary

Figure B-1 Bounds and Position properties of a Scriptable Text Editor

window 327

Table B-1 Variations from standard behavior in Scriptable Text Editor versions

of standard application commands 345

Table B-2 Other Scriptable Text Editor commands 347

313

Page 15

P R E F A C E

About This Guide

The AppleScript Language Guide: English Dialect is a complete guide to the

English dialect of the AppleScript language. AppleScript allows you to create

sets of written instructions—known as scripts—to automate and customize

your applications.

Audience 0

This guide is for anyone who wants to write new scripts or modify

existing scripts.

Before using this guide, you should read Getting Started With AppleScript to

learn what hardware and software you need to use AppleScript; how to install

AppleScript; and how to run, record, and edit scripts.

To make best use of this guide, you should already be familiar with at least one

of the following:

■

another scripting language (such as HyperTalk, the scripting language for

HyperCard, or a scripting language for a specific application)

■

a computer programming language (such as BASIC, Pascal, or C)

■

a macro language (such as a language used to manipulate spreadsheets)

If you’re not already familiar with the basics of scripting and programming

(such as variables, subroutines, and conditional statements such as If-Then),

you may want additional information to help you get started. You can find a

variety of introductory books on scripting and programming—including books

specifically about AppleScript—in many bookstores.

Macintosh software developers who want to create scriptable and recordable

applications should refer to Inside Macintosh: Interapplication Communication.

xv

Page 16

P R E F A C E

Organization of This Guide 0

This guide is divided into two parts:

■

Part 1, “Introducing AppleScript,” provides an overview of the AppleScript

language and the tasks you can perform with it.

■ Part 2, “AppleScript Language Reference,” provides reference descriptions

of all of the features of the AppleScript language.

Part 1 contains these chapters:

■ Chapter 1, “AppleScript, Scripts, and Scriptable Applications,” introduces

AppleScript and its capabilities.

■ Chapter 2, “Overview of AppleScript,” provides an overview of the

elements of the AppleScript language.

Part 2 contains the following chapters:

xvi

■ Chapter 3, “Values,” describes the classes of data that can be stored and

manipulated in scripts and the coercions you can use to change a value

from one class to another.

■ Chapter 4, “Commands,” describes the types of commands available in

AppleScript, including application commands, AppleScript commands,

scripting addition commands, and user-defined commands. It also includes

descriptions of all AppleScript commands and standard application

commands.

■ Chapter 5, “Objects and References,” describes objects and their

characteristics and explains how to refer to objects in scripts.

■ Chapter 6, “Expressions,” describes types of expressions in AppleScript,

how AppleScript evaluates expressions, and operators you use to

manipulate values.

Page 17

P R E F A C E

■ Chapter 7, “Control Statements,” describes statements that control when and

how other statements are executed. It includes information about Tell, If,

and Repeat statements.

■ Chapter 8, “Handlers,” describes subroutines, command handlers, error

handlers, and the scope of variables and properties in handlers and

elsewhere in a script. It includes the syntax for defining and calling

subroutines and error handlers.

■ Chapter 9, “Script Objects,” describes how to define and use script objects. It

includes information about object-oriented programming techniques such as

using inheritance and delegation to define groups of related objects.

At the end of the guide are three appendixes, a glossary of AppleScript terms,

and an index.

■ Appendix A, “The Language at a Glance,” is a collection of tables that

summarize the features of the AppleScript language. It is especially useful

for experienced programmers who want a quick overview of the language.

■ Appendix B, “Scriptable Text Editor Dictionary,” defines the words in the

AppleScript language that are understood by the Scriptable Text Editor

sample application.

■ Appendix C, “Error Messages,” lists the error messages returned

by AppleScript.

Sample Applications and Scripts 0

A sample application, the Scriptable Text Editor, is included with AppleScript.

The Scriptable Text Editor is scriptable; that is, it understands scripts written in

the AppleScript language. It also supports recording of scripts: when you use

the Record button in the Script Editor (the application you use to write and

modify scripts), the actions you perform in the Scriptable Text Editor generate

AppleScript statements for performing those actions. Scripts for performing

tasks in the Scriptable Text Editor are used as examples throughout this guide.

xvii

Page 18

P R E F A C E

For More Information 0

Getting Started 0

See the companion book Getting Started With AppleScript to learn what

hardware and software you need to use AppleScript; how to install

AppleScript; and how to run, record, and edit scripts.

Scripting Additions 0

Scripting additions are files that provide additional commands you can use in

scripts. A standard set of scripting additions comes with AppleScript. Scripting

additions are also sold commercially, included with applications, and

distributed through electronic bulletin boards and user groups.

For information about using the scripting additions that come with AppleScript,

see the companion book AppleScript Scripting Additions Guide: English Dialect.

xviii

Other AppleScript Dialects 0

A dialect is a version of the AppleScript language that resembles a particular

language. This guide describes the English dialect of AppleScript (also

called AppleScript English). This dialect uses words taken from the English

language and has an English-like syntax. Other dialects can use words from

other human languages, such as Japanese, and have a syntax that resembles

a specific human language or programming language.

For information about a specific dialect, see the version of the AppleScript

Language Guide for that dialect.

Scriptable Applications 0

Not all applications are scriptable. The advertising and packaging for an

application usually mention if it is scriptable. The documentation for a

scriptable application typically lists the AppleScript words that the application

understands.

Page 19

P R E F A C E

Conventions Used in This Guide 0

Words and sample scripts in monospaced font are AppleScript language

elements that must be typed exactly as shown. Terms are shown in boldface

where they are defined. You can also find these definitions in the glossary.

Here are some additional conventions used in syntax descriptions:

language element

Plain computer font indicates an element that you

must type exactly as shown. If there are special symbols

(for example, + or &), you must also type them exactly

as shown.

placeholder Italic text indicates a placeholder that you must replace

with an appropriate value. (In some programming

languages, placeholders are called nonterminals.)

[optional] Brackets indicate that the enclosed language element or

elements are optional.

(a group) Parentheses group together elements. If parentheses are

part of the syntax, they are shown in bold.

[optional]... Three ellipsis points (. . .) after a group defined by

brackets indicate that you can repeat the group of

elements within brackets 0 or more times.

(a group). . . Three ellipsis points (. . .) after a group defined by

parentheses indicate that you can repeat the group

of elements within parentheses one or more times.

a|b|cVertical bars separate elements in a group from which

you must choose a single element. The elements are

often grouped within parentheses or brackets.

xix

Page 20

Page 21

P A R T ONE

Introducing AppleScript 1

Page 22

Page 23

CHAPTER 1

Figure 1-0

Listing 1-0

Table 1-0

AppleScript, Scripts, and

Scriptable Applications 1

This chapter introduces the AppleScript scripting language. It answers

these questions:

■ What is AppleScript?

■ What are scripts?

■ Who runs scripts, and who writes them?

■ How is AppleScript different from other scripting mechanisms?

■ What can you do with scripts?

■ What applications are scriptable?

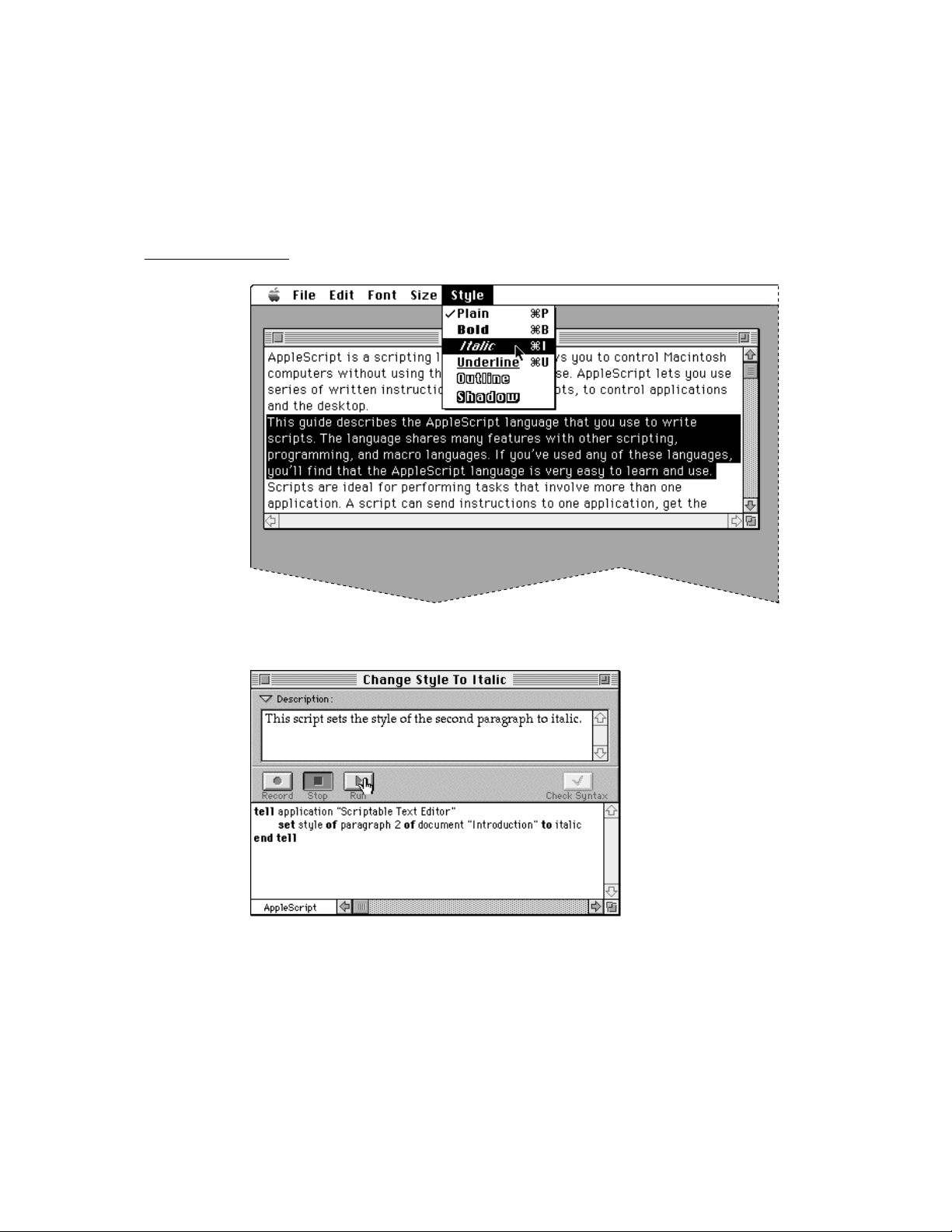

What Is AppleScript? 1

AppleScript is a scripting language that allows you to control Macintosh

computers without using the keyboard or mouse. AppleScript lets you use

series of written instructions, known as scripts, to control applications and the

desktop. Figure 1-1 shows the difference between changing the text style of a

paragraph with the mouse and performing the same task with a script.

What Is AppleScript? 3

Page 24

CHAPTER 1

AppleScript, Scripts, and Scriptable Applications

Figure 1-1 Changing text style with the mouse and with a script

Changing the style of text with the mouse

Changing the style of text with a script

4 What Is AppleScript?

Page 25

CHAPTER 1

AppleScript, Scripts, and Scriptable Applications

The script shown at the bottom of Figure 1-1 is written in AppleScript English,

which is a dialect of the AppleScript scripting language that resembles English.

This guide describes AppleScript English and how you can use it to write

scripts. Other dialects, such as AppleScript Japanese and AppleScript French,

are designed to resemble other human languages. Still others, such as the

Programmer’s Dialect, resemble other programming languages. For information about dialects other than AppleScript English, see the guide for the dialect

you want to use. For information about installing dialects, see Getting Started

With AppleScript.

All AppleScript dialects share many features with other scripting, programming,

and macro languages. If you’ve used any of these languages, you’ll find

AppleScript dialects very easy to learn and use.

AppleScript comes with an application called Script Editor that you can use to

create and modify scripts. You can also use Script Editor to translate scripts

from one AppleScript dialect to another.

What Can You Do With Scripts? 1

AppleScript lets you automate, integrate, and customize applications. The

following sections provide examples.

Automating Activities 1

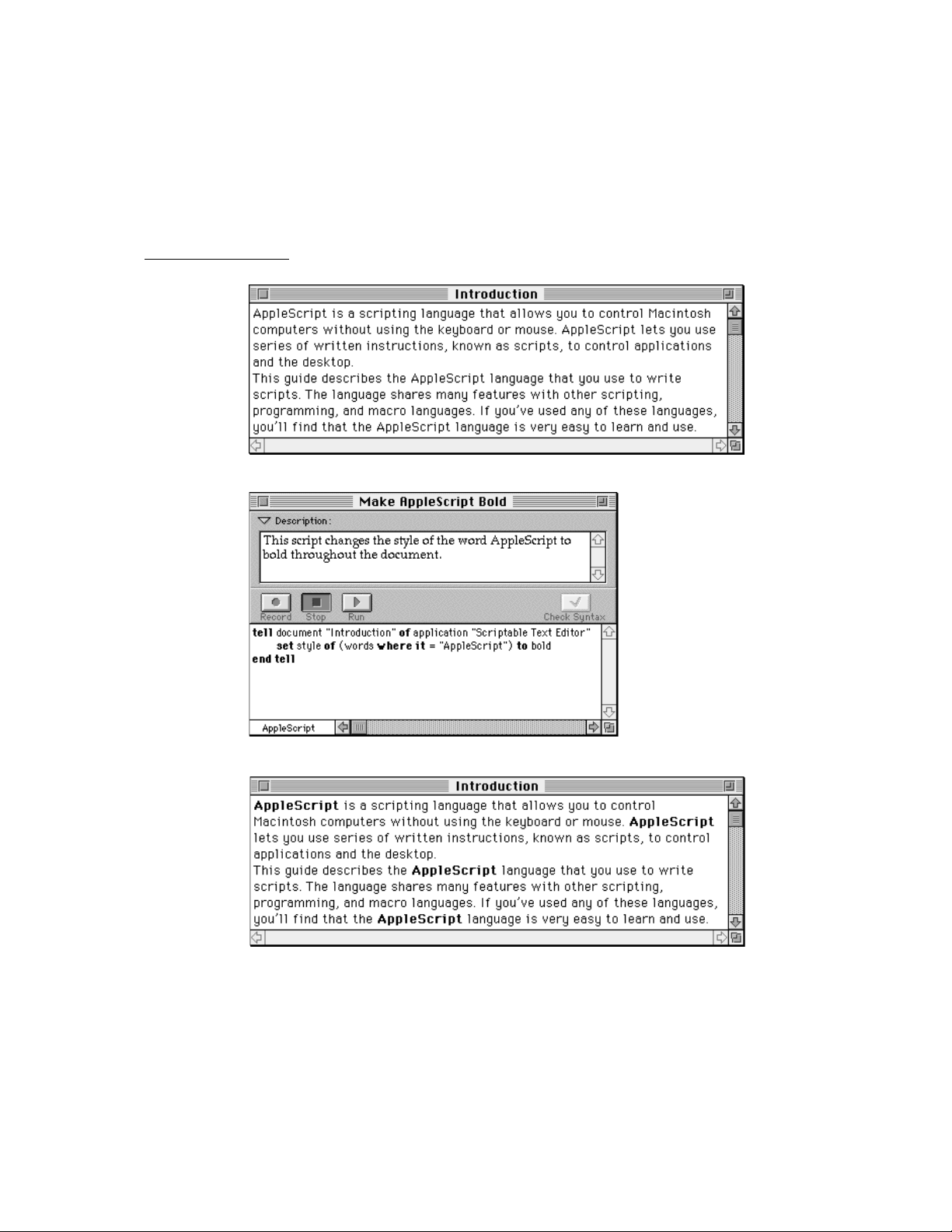

Scripts make it easy to perform repetitive tasks. For example, if you want

to change the style of the word “AppleScript” to bold throughout a document

named Introduction, you can write a script that does the job instead of

searching for each occurrence of the word, selecting it, and changing it from

the Style menu.

Figure 1-2 shows the script and what happens when you run it.

What Can You Do With Scripts? 5

Page 26

CHAPTER 1

AppleScript, Scripts, and Scriptable Applications

Figure 1-2 A script that performs a repetitive action

Introduction before running script

Make AppleScript Bold script

Introduction after running script

6 What Can You Do With Scripts?

Page 27

CHAPTER 1

AppleScript, Scripts, and Scriptable Applications

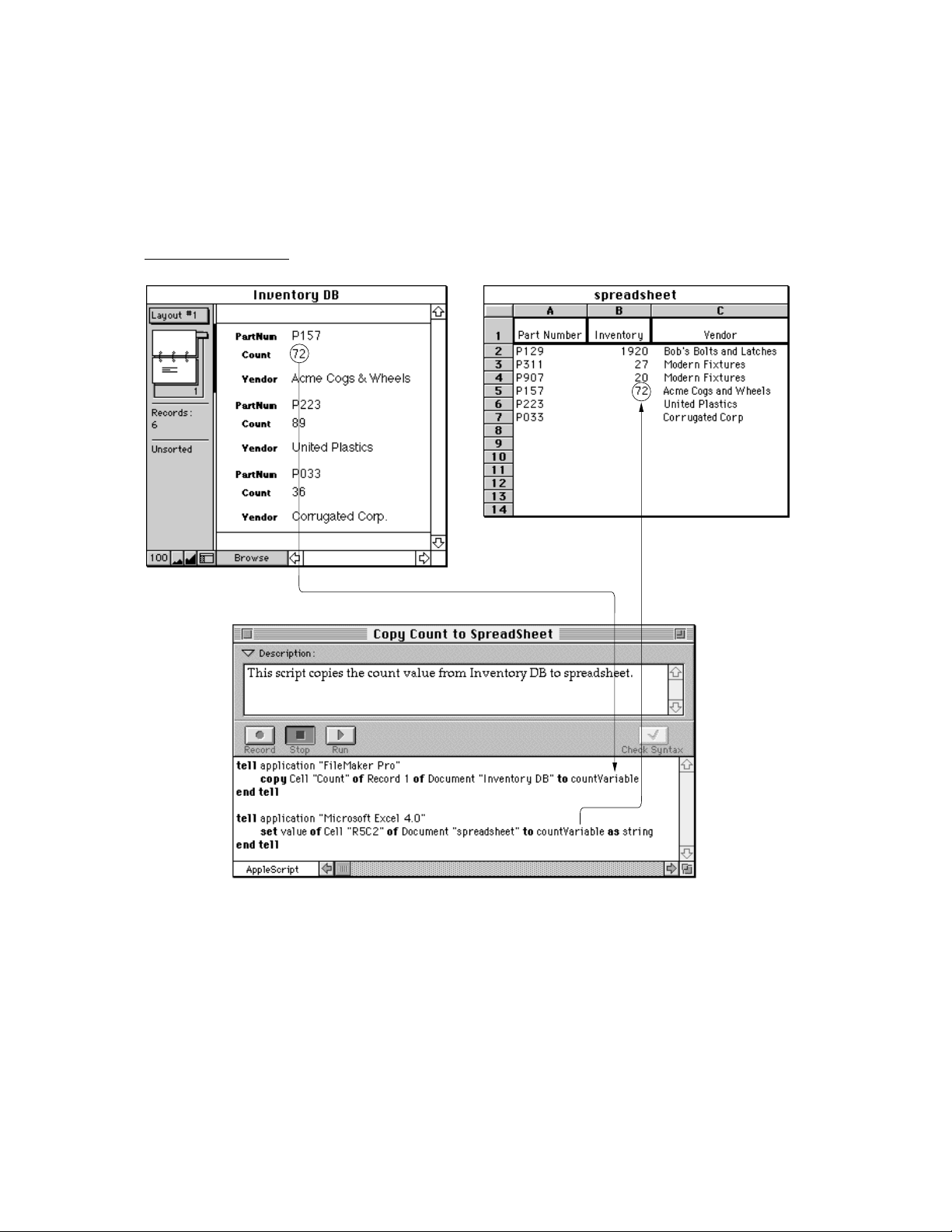

Integrating Applications 1

Scripts are ideal for performing tasks that involve more than one application.

A script can send instructions to one application, get the resulting data, and

then pass the data on to one or more additional applications. For example, a

script can collect information from a database application and copy it to a

spreadsheet application. Figure 1-3 shows a simple script that gets a value

from the Count cell of an inventory database and copies it to the Inventory

column of a spreadsheet.

In the same way, a script can use one application to perform an action on data

from another application. For example, suppose a word-processing application

includes a spelling checker and also supports an AppleScript command to

check spelling. You can check the spelling of a block of text from any other

application by writing a script that sends the AppleScript command and the

text to be checked to the word-processing application, which returns the results

to the application that runs the script.

If an action performed by an application can be controlled by a script, that

action can be also performed from the Script Editor or from any other

application that can run scripts. Every scriptable application is potentially a

toolkit of useful utilities that can be selectively combined with utilities from

other scriptable applications to perform highly specialized tasks.

Customizing Applications 1

Scripts can add new features to applications. To customize an application, you

add a script that is triggered by a particular action within the application, such

as choosing a menu item or clicking a button. Whether you can add scripts to

applications is up to each application, as are the ways you associate scripts

with specific actions.

What Can You Do With Scripts? 7

Page 28

CHAPTER 1

AppleScript, Scripts, and Scriptable Applications

Figure 1-3 A script that copies information from one application to another

8 What Can You Do With Scripts?

Page 29

CHAPTER 1

AppleScript, Scripts, and Scriptable Applications

Who Runs Scripts, and Who Writes Them? 1

To run a script is to cause the actions the script describes to be performed.

Everyone who uses a Macintosh computer can run scripts. Figure 1-4 illustrates

two ways to run a script.

Figure 1-4 Different ways to run a script

Double-clicking a script application’s icon

Clicking the Run button

If the script is a script application on the desktop, you can run it by doubleclicking its icon. You can also run any script by clicking the Run button in the

Script Editor window for that script.

Who Runs Scripts, and Who Writes Them? 9

Page 30

CHAPTER 1

AppleScript, Scripts, and Scriptable Applications

Although everyone can run scripts, not everyone needs to write them. One

person who is familiar with a scripting language can create sophisticated

scripts that many people can use. For example, management information

specialists in a business can write scripts for everyone in the business to use.

Scripts are also sold commercially, included with applications, and distributed

through electronic bulletin boards and user groups.

Special Features of AppleScript 1

AppleScript has a number of features that set it apart from both macro

programs and scripting languages that control a single program:

■ AppleScript makes it easy to refer to data within applications. Scripts can

use familiar names to refer to familiar objects. For example, a script can refer

to paragraph, word, and character objects in a word-processing document

and to row, column, and cell objects in a spreadsheet.

■ You can control several applications from a single script. Although many

applications include built-in scripting or macro languages, most of these

languages work for only one application. In contrast, you can use AppleScript

to control any of the applications that support it. You don’t have to learn a

new language for each application.

■ You can write scripts that control applications on more than one computer. A

single script can control any number of applications, and the applications

can be on any computer on a given network.

■ You can create scripts by recording. The Script Editor application includes a

recording mechanism that takes much of the work out of creating scripts.

When recording is turned on, you can perform actions in a recordable

application and the Script Editor creates corresponding instructions in the

AppleScript language. To learn how to turn recording on and off, refer to

Getting Started With AppleScript.

■ AppleScript supports multiple dialects, or representations of the AppleScript

language that resemble various human languages and programming

languages. This guide describes the AppleScript English dialect. You can use

Script Editor to convert a script from one dialect to another without

changing what happens when you run the script.

10 Special Features of AppleScript

Page 31

CHAPTER 1

AppleScript, Scripts, and Scriptable Applications

What Applications Are Scriptable? 1

Applications that understand one or more AppleScript commands are called

scriptable applications. Not all applications are scriptable. The advertising

and packaging for an application usually mention if it is scriptable. The

documentation for a scriptable application typically lists the AppleScript words

that the application understands.

Some scriptable applications are also recordable. For every significant action

you can perform in a recordable application, the Script Editor can record a

series of corresponding instructions in the AppleScript language. With

recordable applications, you can create a script simply by performing actions

in the application.

Finally, some scriptable applications are also attachable. An attachable applica-

tion is one that can be customized by attaching scripts to specific objects in the

application, such as buttons and menu items. These scripts are triggered by

specific user actions, such as choosing a menu item or clicking a button.

What Applications Are Scriptable? 11

Page 32

Page 33

CHAPTER 2

Figure 2-0

Listing 2-0

Table 2-0

Overview of AppleScript 2

AppleScript is a dynamic, object-oriented script language. At its heart is the

ability to send commands to objects in many different applications. These

objects, which are familiar items such as words or paragraphs in a text-editing

application or shapes in a drawing application, respond to commands by

performing actions. AppleScript determines dynamically—that is, whenever

necessary—which objects and commands an application recognizes based on

information it obtains from each scriptable application.

In addition to manipulating objects in other applications, AppleScript can store

and manipulate its own data, called values. Values are simple data structures,

such as character strings and real numbers, that can be represented in scripts

and manipulated with operators. Values can be obtained from applications or

created in scripts.

The building blocks of scripts are statements. When you write a script, you

compose statements that describe the actions you want to perform. AppleScript

includes several kinds of statements that allow you to control when and how

statements are executed. These include If statements for conditional execution,

Repeat statements for statements that are repeated, and handler definitions for

creating user-defined commands.

This chapter provides an overview of AppleScript. It includes a summary of

how AppleScript works and brief descriptions of the AppleScript language

elements. Part 2 of this book, “AppleScript Language Reference,” describes the

elements of the AppleScript language in more detail.

13

Page 34

CHAPTER 2

Overview of AppleScript

How Does AppleScript Work? 2

AppleScript works by sending messages, called Apple events, to applications.

When you write a script, you write one or more groups of instructions called

statements. When you run the script, the Script Editor sends these statements

to the AppleScript extension, which interprets the statements and sends Apple

events to the appropriate applications. Figure 2-1 shows the relationship

between the Script Editor, the AppleScript extension, and the application.

The parts that you use—the Script Editor and the application—are shown to

the left of the dotted line in Figure 2-1. The parts that work behind the scenes—

the AppleScript extension and Apple events—are shown to the right of the

dotted line.

Applications respond to Apple events by performing actions, such as changing

a text style, getting a value, or opening a document. Applications can also

send Apple events back to the AppleScript extension to report results. The

AppleScript extension sends the final results to the Script Editor, where they

are displayed in the result window.

When you write scripts, you needn’t be concerned about Apple events or the

AppleScript extension. All you need to know is how to use the AppleScript

language to request the actions or results that you want.

Statements 2

Every script is a series of statements. Statements are structures similar to

sentences in human languages that contain instructions for AppleScript to

perform. When AppleScript runs a script, it reads the statements in order and

carries out their instructions. Some statements cause AppleScript to skip or

repeat certain instructions or change the way it performs certain tasks. These

statements, which are described in Chapter 7, are called control statements.

14 How Does AppleScript Work?

Page 35

CHAPTER 2

Overview of AppleScript

Figure 2-1 How AppleScript works

Script Editor

Writes, records, and runs scripts

Application

• Responds to Apple events by performing actions

• Sends Apple events to AppleScript extension

1

4

AppleScript

statements

(results)

AppleScript extension

• Interprets script statements and

sends corresponding Apple events

• Interprets Apple events and sends

results back to the Script Editor

3

Apple events

(results)

2

Apple events

(requests for action)

Statements 15

Page 36

CHAPTER 2

Overview of AppleScript

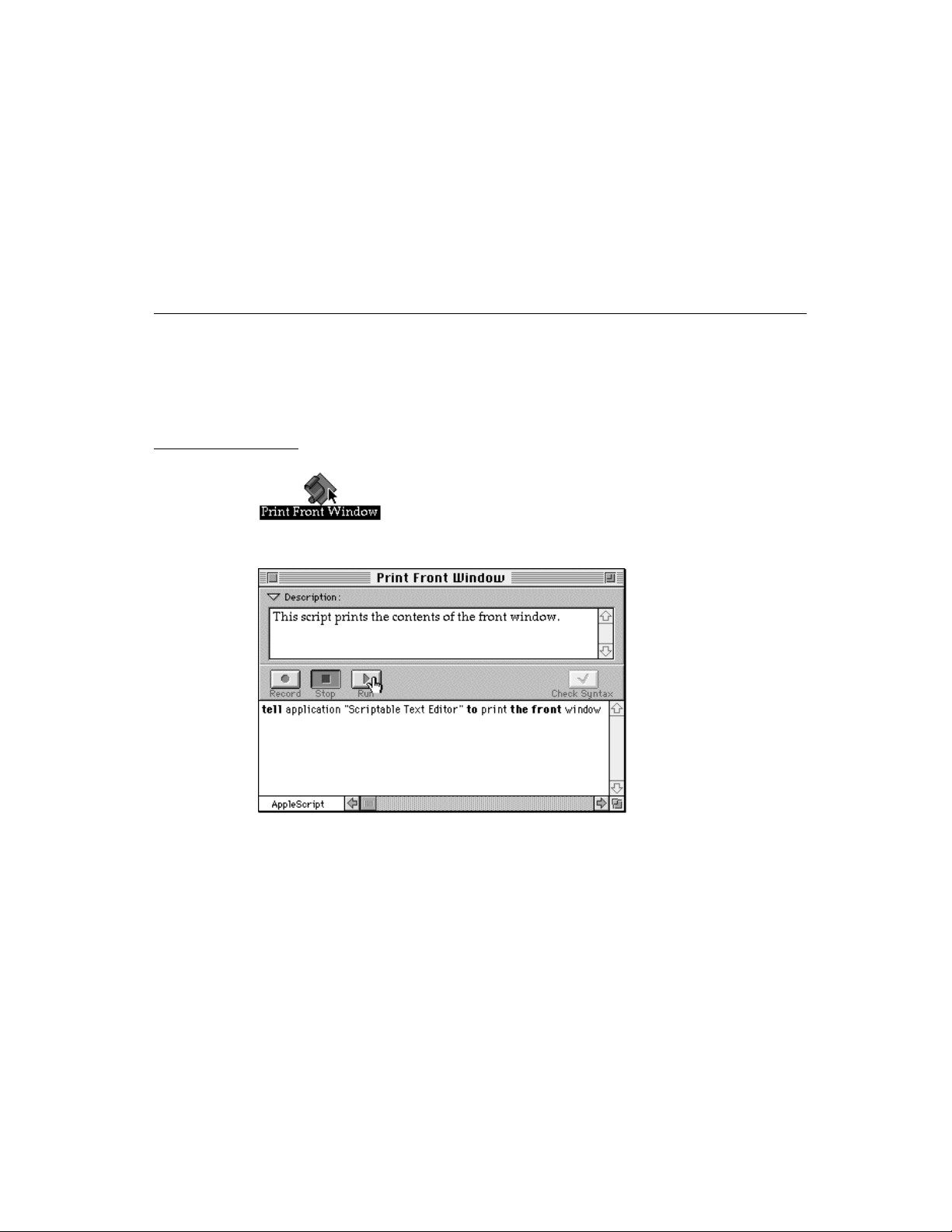

All statements, including control statements, fall into one of two categories:

simple statements or compound statements. Simple statements are statements

such as the following that are written on a single line.

tell application "Scriptable Text Editor" to print the front window

Compound statements are statements that are written on more than one line

and contain other statements. All compound statements have two things in

common: they can contain any number of statements, and they have the word

end (followed, optionally, by the first word of the statement) as their last line.

The simple statement of the first example in this section is equivalent to the

following compound statement.

tell application "Scriptable Text Editor"

print the front window

end tell

The compound Tell statement includes the lines tell application

"Scriptable Text Editor" and end tell, and all statements between

these two lines.

A compound statement can contain any number of statements. For example,

here is a Tell statement that contains two statements:

tell application "Scriptable Text Editor"

print front window

close front window

end tell

This example illustrates the advantage of using a compound Tell statement:

you can add additional statements within a compound statement.

Note

Notice that this example contains the statement print

front window instead of print the front window.

AppleScript allows you to add or remove the word the

anywhere in a script without changing the meaning of the

script. You can use the word the to make your statements

more English-like and therefore more readable. ◆

16 Statements

Page 37

CHAPTER 2

Overview of AppleScript

Here’s another example of a compound statement:

if the number of windows is greater than 0 then

print front window

end if

Statements contained in a compound statement can themselves be compound

statements. Here’s an example:

tell application "Scriptable Text Editor"

if the number of windows is greater than 0 then

print front window

end if

end tell

Commands and Objects 2

Commands are the words or phrases you use in AppleScript statements to

request actions or results. Every command is directed at a target, which is

the object that responds to the command. The target of a command is usually

an application object. Application objects are objects that belong to an

application, such as windows, or objects in documents, such as the words

and paragraphs in a text document. Each application object has specific

information associated with it and can respond to specific commands.

For example, in the Scriptable Text Editor, window objects understand the Print

command. The following example shows how to use the Print command to

request that the Scriptable Text Editor print the front window.

tell application "Scriptable Text Editor"

print front window

end tell

The Print command is contained within a Tell statement. Tell statements

specify default targets for the commands they contain. The default target is the

object that receives commands if no other object is specified or if the object is

Commands and Objects 17

Page 38

CHAPTER 2

Overview of AppleScript

specified incompletely in the command. In this case, the statement containing

the Print statement does not contain enough information to uniquely identify

the window object, so AppleScript uses the application name listed in the Tell

statement to determine which object receives the Print command.

In AppleScript, you use references to identify objects. A reference is a

compound name, similar to a pathname or address, that specifies an object.

For example, the following phrase is a reference:

front window of application "Scriptable Text Editor"

This phrase specifies a window object that belongs to a specific application.

(The application itself is also an object.) AppleScript has different types of

references that allow you to specify objects in many different ways. You’ll learn

more about references in Chapter 5, “Objects and References.”

Objects can contain other objects, called elements. In the previous example, the

front window is an element of the Scriptable Text Editor application object.

Similarly, in the next example, a word element is contained in a specific

paragraph element, which is contained in a specific document.

word 1 of paragraph 3 of document "Try This"

Every object belongs to an object class, which is simply a name for objects with

similar characteristics. Among the characteristics that are the same for the

objects in a class are the commands that can act on the objects and the elements

they can contain. An example of an object class is the Document object class in

the Scriptable Text Editor. Every document created by the Script Editor belongs

to the Document object class. The Script Editor’s definition of the document

object class determines which classes of elements, such as paragraphs and

words, a document object can contain. The definition also determines which

commands, such as the Close command, a document object can respond to.

Dictionaries 2

To examine a definition of an object class, a command, or some other word

supported by an application, you can open that application’s dictionary from

the Script Editor. A dictionary is a set of definitions for words that are

understood by a particular application. Unlike other scripting languages,

18 Dictionaries

Page 39

CHAPTER 2

Overview of AppleScript

AppleScript does not have a single fixed set of definitions for use with all

applications. Instead, when you write scripts in AppleScript, you use both

definitions provided by AppleScript and definitions provided by individual

applications to suit their capabilities.

Dictionaries tell you which objects are available in a particular application and

which commands you can use to control them. Typically, the documentation

for a scriptable application includes a complete list of the words in its

dictionary. For example, Appendix B of this book contains a complete list of the

words in the Scriptable Text Editor dictionary. In addition, if you are using the

Script Editor, you can view the list of commands and objects for a particular

application in a Dictionary window. For more information, see Getting Started

With AppleScript.

To use the words from an application’s dictionary in a script, you must indicate

which application you want to manipulate. You can do this with a Tell

statement that lists the name of the application:

tell application "Scriptable Text Editor"

print front window

close front window

end tell

AppleScript reads the words in the application’s dictionary at the beginning

of the Tell statement and uses them to interpret the statements in the Tell

statement. For example, AppleScript uses the words in the Scriptable Text

Editor dictionary to interpret the Print and Close commands in the Tell

statement shown in the example.

Another way to use an application’s dictionary is to specify the application

name completely in a simple statement:

print front window of application "Scriptable Text Editor"

In this case, AppleScript uses the words in the Scriptable Text Editor dictionary

to interpret the words in this statement only.

When you use a Tell statement or specify an application name completely in

a statement, the AppleScript extension gets the dictionary resource for the

application and reads its dictionary of commands, objects, and other words.

Every scriptable application has a dictionary resource that defines the

commands, objects, and other words script writers can use in scripts to control

Dictionaries 19

Page 40

CHAPTER 2

Overview of AppleScript

the application. Figure 2-2 shows how AppleScript gets the words in the

Scriptable Text Editor ’s dictionary.

Figure 2-2 How AppleScript gets the Scriptable Text Editor dictionary

Scriptable Text Editor

application

Dictionary

resource

AppleScript

extension

Commands:

cut

make

print

...

Objects:

character

paragraph

window

...

Dictionary of

commands

and objects

In addition to the terms defined in application dictionaries, the AppleScript

English dialect includes its own standard terms. Unlike the terms in application dictionaries, the standard AppleScript terms are always available. You can

use these terms (such as If, Tell, and First) anywhere in a script. This manual

describes the standard terms provided by the AppleScript English dialect.

The words in system and application dictionaries are known as reserved

words. When defining new words for your script—such as identifiers for

variables—you cannot use reserved words.

Values 2

A value is a simple data structure that can be represented, stored, and

manipulated within AppleScript. AppleScript recognizes many types of values,

including character strings, real numbers, integers, lists, and dates. Values are

fundamentally different from application objects, which can be manipulated

from AppleScript, but are contained in applications or their documents. Values

can be created in scripts or returned as results of commands sent to applications.

20 Values

Page 41

CHAPTER 2

Overview of AppleScript

Values are an important means of exchanging data in AppleScript. When you

request information about application objects, it is usually returned in the form

of values. Similarly, when you provide information with commands, you

typically supply it in the form of values.

A fixed number of specific types of values are recognized by AppleScript. You

cannot define additional types of values, nor can you change the way values

are represented. The different types of AppleScript values, called value classes,

are described in Chapter 3, “Values.”

Expressions 2

An expression is a series of AppleScript words that corresponds to a value.

Expressions are used in scripts to represent or derive values. When you run a

script, AppleScript converts its expressions into values. This process is known

as evaluation.

Two common types of expressions are operations and variables. An operation

is an expression that derives a new value from one or two other values. A

variable is a named container in which a value is stored. The following sections

introduce operations and variables. For more information about these and

other types of expressions, see Chapter 6, “Expressions.”

Operations 2

The following are examples of AppleScript operations and their values. The

value of each operation is listed following the comment characters (--).

3 + 4 --value: 7

(12 > 4) AND (12 = 4) --value: false

Each operation contains an operator. The plus sign (+) in the first expression, as

well as the greater than symbol (>), the equal symbol (=) symbol, and the word

AND in the second expression, are operators. Operators transform values or

pairs of values into other values. Operators that operate on two values are

called binary operators. Operators that operate on a single value are known as

unary operators. Chapter 6, “Expressions,” contains a complete list of the

operators AppleScript supports and the rules for using them.

Expressions 21

Page 42

CHAPTER 2

Overview of AppleScript

You can use operations within AppleScript statements, such as:

tell application "Scriptable Text Editor"

delete word 3 + 4 of document "Test"

end tell

When you run this script, AppleScript evaluates the expression 3 + 4 and

uses the result to determine which word to delete.

Variables 2

When AppleScript encounters a variable in a script, it evaluates the variable by

getting its value. To create a variable, simply assign it a value:

copy "Mitch" to myName

The Copy command takes the data—the string "Mitch"—and puts it in the

variable myName. You can accomplish the same thing with the Set command:

set myName to "Mitch"

Statements that assign values to variables are known as assignment statements.

You can retrieve the value in a variable with a Get command. Run the

following script and then display the result:

set myName to "Mitch"

get myName

You see that the value in myName is the value you stored with the Set command.

You can change the value of a variable by assigning it a new value. A variable

can hold only one value at a time. When you assign a new value to an existing

variable, you lose the old value. For example, the result of the Get command in

the following script is "Pegi".

set myName to "Mitch"

set myName to "Pegi"

get myName

22 Expressions

Page 43

CHAPTER 2

Overview of AppleScript

AppleScript does not distinguish uppercase letters from lowercase variables in

variable names; the variables myName, myname, and MYNAME all represent the

same value.

Script Objects 2

Script objects are objects you define and use in scripts. Like application objects,

script objects respond to commands and have specific information associated

with them. Unlike application objects, script objects are defined in scripts.

Script objects are an advanced feature of AppleScript. They allow you to use

object-oriented programming techniques to define new objects and commands.

Information contained in script objects can be saved and used by other scripts.

For information about defining and using script objects, see Chapter 9, “Script

Objects.” You should be familiar with the concepts in the rest of this guide

before attempting to use script objects.

Scripting Additions 2

Scripting additions are files that provide additional commands or coercions

you can use in scripts. A scripting addition file must be located in the Scripting

Additions folder (located in the Extensions folder of the System Folder) for

AppleScript to recognize the additional commands it provides.

Unlike other commands used in AppleScript, scripting addition commands

work the same way regardless of the target you specify. For example, the Beep

command, which is provided by the General Commands scripting addition,

triggers the alert sound no matter which application the command is sent to.

A single scripting addition file can contain several commands. For example, the

File Commands scripting addition includes the commands Path To, List Folder,

List Disks, and Info For. The scripting additions provided by Apple Computer,

Inc., are described in the book AppleScript Scripting Additions Guide. Scripting

additions are also sold commercially, included with applications, and

distributed through electronic bulletin boards and user groups.

Script Objects 23

Page 44

CHAPTER 2

Overview of AppleScript

Dialects 2

AppleScript scripts can be displayed in several different dialects, or representations of AppleScript that resemble human languages or programming

languages. The dialects available on a given computer are determined by the

Dialects folder, a folder in the Scripting Additions folder (which in turn is

located in the Extensions folder of the System Folder) that contains one dialect

file for each AppleScript dialect installed on your computer.

You can select any of the available dialects from the Script Editor. You can

tell which dialects are available by examining the pop-up menu in the lowerleft corner of a Script Editor window. You can change the dialect in which a

script is displayed by selecting a different dialect from the pop-up menu. The

behavior of a script when you run it is not affected by the dialect in which it

is displayed.

For more information about selecting dialects and formatting options from the

Script Editor, see Getting Started With AppleScript.

Other Features and Language Elements 2

So far, you’ve been introduced to the key elements of the AppleScript language,

including statements, objects, commands, expressions, and script objects.

The reference section of this guide discusses these elements in more detail

and describes how to use them in scripts. Before you continue to the reference

section, however, you’ll need to know about a few additional elements

and features of the AppleScript scripting language that are not described in

the reference:

■ continuation characters

■ comments

■ identifiers

■ case sensitivity

■ abbreviations

■ compiling scripts

24 Dialects

Page 45

CHAPTER 2

Overview of AppleScript

Continuation Characters 2

A simple AppleScript statement must normally be on a single line. If a statement

is longer than will fit on one line, you can extend it by including a continuation

character, ¬ (Option-L or Option-Return), at the end of one line and continuing

the statement on the next. For example, the statement

delete word 1 of paragraph 3 of document "Learning AppleScript"

can appear on two lines:

delete word 1 of paragraph 3 of document ¬

"Learning AppleScript"

The only place a continuation character does not work is within a string. For

example, the following statement causes an error, because AppleScript interprets

the two lines as separate statements.

--this statement causes an error:

delete word 1 of paragraph 3 of document "Fundamentals ¬

of Programming"

Note

The characters -- in the example indicate that the first line

is a comment. A comment is text that is ignored by

AppleScript when a script is run. Comments are added to

help you understand scripts. They are explained in the

next section, “Comments.” ◆

If a string extends beyond the end of the line, you can continue typing without

pressing Return (the text never wraps to the next line), or you can break the

string into two or more strings and use the concatenation operator (&) to

join them:

delete word 1 of paragraph 3 of document "Fundamentals " ¬

& "of Programming"

For more information about the concatenation operator, see Chapter 6,

“Expressions.”

Other Features and Language Elements 25

Page 46

CHAPTER 2

Overview of AppleScript

Comments 2

To explain what a script does, you add comments. A comment is text that

remains in a script after compilation but is ignored by AppleScript when the

script is executed. There are two kinds of comments:

■ A block comment begins with the characters (* and ends with the

characters *). Block comments must be placed between other statements.

They cannot be embedded in simple statements.

■ An end-of-line comment begins with the characters -- and ends with the

end of the line.

You can nest comments, that is, comments can contain other comments.

Here are some sample comments:

--end-of-line comments extend to the end of the line;

(* Use block comments for comments that occupy

more than one line *)

copy result to theCount--stores the result in theCount

(* The following subroutine, findString, searches for a

string in a list of Scriptable Text Editor files *)

(* Here are examples of

--nested comments

(* another comment within a comment *)

*)

The following block comment causes an error because it is embedded in

a statement.

--the following block comment is illegal

tell application "Scriptable Text Editor"

get (* word 1 of *) paragraph 1 of front document

end tell

26 Other Features and Language Elements

Page 47

CHAPTER 2

Overview of AppleScript

Because comments are not executed, you can prevent parts of scripts from

being executed by putting them within comments. You can use this trick,

known as “commenting out,” to isolate problems when debugging scripts or

temporarily block execution of any parts of script that aren’t yet finished.

Here’s an example of “commenting out” an unfinished handler:

(*

on finish()

--under construction

end

*)

If you later remove (* and *), the handler is once again available.

Identifiers 2

An identifier is a series of characters that identifies a value or other language

element. For example, variable names are identifiers. In the following

statement, the variable name myName identifies the value "Fred".

set myName to "Fred"

Identifiers are also used as labels for properties and handlers. You’ll learn

about these uses later in this guide.

An identifier must begin with a letter and can contain uppercase letters,

lowercase letters, numerals (0–9), and the underscore character (_). Here

are some examples of valid identifiers:

Yes

Agent99

Just_Do_It

The following are not valid identifiers:

C-Back&Forth

999

Why^Not

Other Features and Language Elements 27

Page 48

CHAPTER 2

Overview of AppleScript

Identifiers whose first and last characters are vertical bars (|) can contain any

characters. For example, the following are legal identifiers:

|Back and Forth|

|Right*Now!|

Identifiers whose first and last characters are vertical bars can contain additional

vertical bars if the vertical bars are preceded by backslash (\) characters, as in

the identifier |This\|Or\|That|. A backslash character in an identifier must

be preceded by a backslash character, as in the identifier |/\\ Up \\/ Down|.

AppleScript identifiers are not case sensitive. For example, the variable

identifiers myvariable and MyVariable are equivalent.

Identifiers cannot be the same as any reserved words—that is, words in the

system dictionary or words in the dictionary of the application named in the

Tell statement. For example, you cannot create a variable whose identifier is

Yes within a Tell statement to the Scriptable Text Editor, because Yes is a

constant from the Scriptable Text Editor dictionary. In this case, AppleScript

returns a syntax error if you use Yes as a variable identifier.

Case Sensitivity 2

AppleScript is not case sensitive; when it interprets statements in a script, it

does not distinguish uppercase from lowercase letters. This is true for all

elements of the language.

The one exception to this rule is string comparisons. Normally, AppleScript

does not distinguish uppercase from lowercase letters when comparing strings,

but if you want AppleScript to consider case, you can use a special statement

called a Considering statement. For more information, see “Considering and

Ignoring Statements” on page 213.

Most of the examples in this chapter and throughout this guide are in lowercase letters. Sometimes words are capitalized to improve readability. For

example, in the following variable assignment, the “N” in myName is capitalized

to make it easier to see that two words have been combined to form the name of

the variable.

set myName to "Pegi"

28 Other Features and Language Elements

Page 49

CHAPTER 2

Overview of AppleScript

After you create the variable myName, you can refer to it by any of these names:

MYNAME

myname

MyName

mYName

When interpreting strings, such as "Pegi", AppleScript preserves the case of

the letters in the string, but does not use it in comparisons. For example, the

value of the variable myName defined earlier is always "Pegi", but the value

of the expression myName = "PEGI" is true.

Abbreviations 2

The AppleScript English dialect is designed to be intuitive and easy to understand. To this end, AppleScript English uses familiar words to represent objects

and commands and uses statements whose structure is similar to English

sentences. For the same reason, it typically uses real words instead of abbreviations. In a few cases, however, AppleScript supports abbreviations for long and

frequently used words.

One important example is the abbreviation app, which you can use to refer to

objects of class application. This is particularly useful in Tell statements. For

example, the following two Tell statements are equivalent:

tell application "Scriptable Text Editor"

print the front window

end tell

tell app "Scriptable Text Editor"

print the front window

end tell

Other Features and Language Elements 29

Page 50

CHAPTER 2

Overview of AppleScript

Compiling Scripts With the Script Editor 2

When you create or modify a script and then attempt to run or save it as a

compiled script or script application, the Script Editor asks AppleScript to

compile the script first. To compile a script, AppleScript converts the script

from the form typed into a Script Editor window (or any script-editing

window) to a form that AppleScript can execute. AppleScript also attempts to

compile the script when you click the Script Editor’s Check Syntax button.

If AppleScript compiles the script successfully, the Check Syntax button is

dimmed and the Script Editor reformats the text of the script according to the

preferences set with the AppleScript Formatting command (in the Edit menu).

This may cause indentation and spacing to change, but it doesn’t affect the

meaning of the script. If AppleScript can’t compile the script because of syntax

errors or other problems, the Script Editor displays a dialog box describing the

error or, if you are trying to save the script, allowing you to save the script as a

text file only.

30 Other Features and Language Elements

Page 51

P A R T TWO

AppleScript Language

Reference 2

Page 52

Page 53

CHAPTER 3

Figure 3-0

Listing 3-0

Table 3-0

Values 3

Values are data that can be represented, stored, and manipulated in scripts.

AppleScript recognizes many types of values, including character strings, real

numbers, integers, lists, and dates. Values are different from application

objects, which can also be manipulated from AppleScript but are contained in

applications or their documents.

Each value belongs to a value class, which is a category of values that are

represented in the same way and respond to the same operators. To find out

how to represent a particular value, or which operators it responds to, check its

value class definition. AppleScript can coerce a value of one class into a value

of another. The possible coercions depend on the class of the original value.

This chapter describes how to interpret value class definitions, discusses the

common characteristics of all value classes, and presents definitions of the

value classes supported in AppleScript. It also describes how to coerce values.

Using Value Class Definitions 3

Value class definitions contain information about values that belong to a

particular class. All value classes fall into one of two categories: simple values,

such as integers and real numbers, which do not contain other values, or

composite values, such as lists and records, which do. Value class definitions

for composite values contain more types of information than definitions for

simple values.

Figure 3-1 shows the definition for the List value class, a composite value. The

figure shows seven types of information: examples, properties, elements,

operators, commands handled, reference forms, and coercions supported. The

sections following the figure explain each type of information. Some definitions

end with notes (not shown in Figure 3-1) that provide additional information.

Using Value Class Definitions 33

Page 54

CHAPTER 3

Values

Figure 3-1 Value class definition for lists

List

A value of class List is an ordered collection of values. The values

contained in a list are known as items. Each item can belong to

any class.

LITERAL EXPRESSIONS

A list appears in a script as a series of expressions contained within braces

and separated by commas. For example,

{ "it's", 2, TRUE }

is a list containing a string, an integer, and a Boolean.

PROPERTIES

Class

Length

Rest

Reverse

The class identifier for the value. This property is read-only,

and its value is always list.

An integer containing the number of items in the list. This

property is read-only.

A list containing all items in the list except the first item.

A list containing all items in the list, but in the opposite order.

ELEMENTS

Item

A value contained in the list. Each value contained in a list is

an item. You can refer to values by their item numbers. For

example, item 2 of {"soup", 2, "nuts"} is

integer 2. To specify items of a list, use the reference forms

listed in "Reference Forms" later in this definition.

OPERATORS

The operators that can have lists as operands are &, =, , Starts With, Ends

With, Contains, Is Contained By.

34 Using Value Class Definitions

the

Page 55

CHAPTER 3

Values

Figure 3-1 Value class definition for lists (continued)

Using Value Class Definitions 35

Page 56

CHAPTER 3

Values

COMMANDS HANDLED

You can count the items in a list with the Count command. For example,

the value of the following statement is 6.

count {"a", "b", "c", 1, 2, 3}

--result: 6

You can also count elements of a specific class in a list. For example, the

value of the following statement is 3.

count integers in {"a", "b", "c", 1, 2, 3}

--result: 3

Another way to count the items in a list is with a Length property

reference:

length of {"a", "b", "c", 1, 2, 3}

--result: 6

REFERENCE FORMS

Use the following forms to refer to properties of lists and items in lists:

•

Property. For example, class of {"this", "is", "a", "list"}

specifies list.

•

Index. For example, item 3 of {"this", "is", "a", "list"}

specifies "a".

COERCIONS SUPPORTED

AppleScript supports coercion of a single-item list to any value class

to which the item can be coerced if it is not part of a list.

AppleScript also supports coercion of an entire list to a string if all

items in the list can be coerced to a string. The resulting string

concatenates all the items:

{5, "George", 11.43, "Bill"} as string

--result: "5George11.43Bill"

36 Using Value Class Definitions

Page 57

CHAPTER 3

Values

Literal Expressions 3

A literal expression is an expression that evaluates to itself. The “Literal

Expressions” section of a value class definition shows examples of how values

of a particular class are represented in AppleScript—that is, typical literal

expressions for values of that class. For example, in AppleScript and many

other programming languages, the literal expression for a string is a series of

characters enclosed in quotation marks. The quotation marks are not part of the

string value; they are a notation that indicates where the string begins and

ends. The actual string value is a data structure stored in AppleScript.

The sample value class definition in Figure 3-1 shows literal expressions for list

values. As with the quotation marks in a string literal expression, the braces

that enclose a list and the commas that separate its items are not part of the

actual list value; they are notations that represent the grouping and items of

the list.

Properties 3

A property of a value is a characteristic that is identified by a unique label and

has a single value. Simple values have only one property, called Class, that

identifies the class of the value. Composite values have a Class property, a

Length property, and in some cases additional properties.

Use the Name reference form to specify properties of values. For example, the

following reference specifies the Class property of an integer.

class of 101

--result: integer

The following reference specifies the Length property of a list.

length of {"This", "list", "has", 5, "items"}

--result: 5

You can optionally use the Get command with the Name reference form to

get the value of a property for a specified value. In most cases, you can also

use the Set command to set the additional properties listed in the definitions

of composite values. If a property cannot be set with the Set command, its

definition specifies that it is read-only.

Using Value Class Definitions 37

Page 58

CHAPTER 3

Values

Elements 3

Elements of values are values contained within other values. Composite values

have elements; simple values do not. The sample value class definition in

Figure 3-1 shows one element, called an item.

Use references to refer to elements of composite values. For example, the

following reference specifies the third item in a list:

item 3 of {"To", "be", "great", "is", "to", "be", "misunderstood"}

--result: "great"

The “Reference Forms” section of a composite value class definition lists the

reference forms you can use to specify elements of composite values.

Operators 3

You use operators, such as the addition operator (+), the concatenation

operator (&), and the equality operator (=), to manipulate values. Values

that belong to the same class can be manipulated by the same operators.

The “Operators” section of a value class definition lists the operators that

can be used with values of a particular class.

For complete descriptions of operators and how to use them in expressions,

see “Operations,” which begins on page 161.

Commands Handled 3

Commands are requests for action. Simple values cannot respond to commands,

but composite values can. For example, lists can respond to the Count

command, as shown in the following example.

count {"This", "list", "has", 5, "items"}

--result: 5

Each composite value class definition includes a “Commands Handled” section

that lists commands to which values of that class can respond.

38 Using Value Class Definitions

Page 59

CHAPTER 3

Values

Reference Forms 3

A reference is a compound name for an object or a value. You can use

references to specify values within composite values or properties of simple

values. You cannot use references to refer to simple values.

The “Reference Forms” section is included in composite value class definitions

only. It lists the reference forms you can use to specify elements of a composite

value. For complete descriptions of the AppleScript reference forms, see

Chapter 5, “Objects and References.”

Coercions Supported 3

AppleScript can change a value of one class into a value of another class. This

is called coercion. The “Coercions Supported” section of a value class

definition describes the classes to which values of that class can be coerced.

Because a list consists of one or more values, any value can be added to a list or

coerced to a single-value list. The definition in Figure 3-1 also lists the value

classes to which individual items in a list can be coerced.

For more information about coercions, see “Coercing Values,” which begins

on page 68. For a summary of the coercions provided by AppleScript, see

Figure 3-2 on page 70.

Value Class Definitions 3

This section describes the AppleScript value classes. Table 3-1 summarizes the

class identifiers recognized by AppleScript.

Three identifiers in Table 3-1 act only as synonyms for other value classes:

Number is a synonym for either Integer or Real, Text is a synonym for String,

and Styled Text is a synonym for a string that contains style and font

information. You can coerce values using these synonyms, but the class of the

resulting value is always the true value class.

Value Class Definitions 39

Page 60

CHAPTER 3

Values

Table 3-1 AppleScript value class identifiers

Value class

identifier Description of corresponding value

Boolean A logical truth value

Class A class identifier

Constant A reserved word defined by an application or AppleScript

Data Raw data that cannot be represented in AppleScript, but can

be stored in a variable

Date A string that specifies a day of the week, day of the month,

month, year, and time

Integer A positive or negative number without a fractional part

List An ordered collection of values

Number Synonym for class Integer or class Real; a positive or negative

number that can be either of class Integer or of class Real

Real A positive or negative number that can have a fractional part

Record A collection of properties

Reference A reference to an object

String An ordered series of characters

Styled Text Synonym for a special string that includes style and font

information

Text Synonym for class string

For example, you can use the class identifier Text to coerce a date to a string:

set x to date "May 14, 1993" as text

class of x

--result: string

Although definitions for value class synonyms are included in the sections that

follow, they do not correspond to separate value classes. For more information

about coercing values using synonyms, see “Coercing Values,” which begins on

page 68.

40 Value Class Definitions

Page 61

CHAPTER 3

Values

Boolean 3

A value of class Boolean is a logical truth value. The most common Boolean

values are the results of comparisons, such as 4 > 3 and WordCount = 5.