Page 1

MCS@51 MICROCONTROLLER

FAMILY USER’S MANUAL

ORDER NO.: 272383-002

FEBRUARY 1994

Page 2

Intel Corporation makes no warrsnfy for the uee of ite products and assumes no responsibility for any ewors which may

appear in this document nor does it make a commitment to update the information contained herein.

Intel retains the rightto make changes to these specifications at any time, without notk

Contact your local Intel sales office or your distributorto obtain the latest speoificationa before placing your product order.

MDS is an ordering code only and is not usad ae a product name or trademark of Intel Corporation.

Intel Corporation and Intel’s FASTPATH are not affiliated with Kinetics, a division of Excelan, Inc. or its FASTPATH

trademark or products,

●Ofher brands and names are the properly of their respective owners,

Additional copies of this document or other Intel literature maybe obtained from:

Intel Corporation

Literature Selas

P.O. Box 7S41

Mt. Prospect, IL 6005S-7641

or call 1-800-879-4683

c-INTELCORPORATION, 1093

Page 3

MCS” 51 CONTENTS

MICROCONTROLLER c“*pTf==1

FAMILY

USER’S MANUAL

MCS 51 Family of Microcontrollers

Archkedural Ovewiew .............................l-l

CHAPTER 2

MCS 51 Programmer’s Guide and

Instruction Set ..........................................2-l

CHAPTER 3

8051, 8052 and 80C51 Hardware

Description ...............................................3.l

CHAPTER 4

8XC52J54/58 Hardware Description ............4-1

CHAPTER 5

8XC51 FX Hardware Description .................5-1

CHAPTER 6

87C51GB Hardware Description .................8-1

CHAPTER 7

83CI 52 Hardware Description ....................7-1

PAGE

Page 4

Page 5

MCS@51 Family of

Microcontrollers

Architectural Overview

1

Page 6

Page 7

MCS@51 FAMILY OF CONTENTS

PAGE

MICROCONTROLLERS INTRODUCTION .........................................1-3

ARCHITECTURAL CHMOSDevices ... ..”.....’.......”.....-...-... .......I-5

OVERVIEW M;~$&:RGA-~oN INMc- 51

Lo ical Separation of Program and Data

h emoy ....................................................l+

Program Memo~ .........................................l-7

Data Memory ...............................................1 -8

THE MC951 INSTRUCTION SET .............1-9

Program Status Word ..................................1-9

Addressing Modes .....................................l-l O

Arithmetic Instructions ...............................1-10

Logical lnstrudions ....................................l.l2

Data Tran#ers ...........................................l.l2

Boolean Instructions

Jump Instructions ......................................1-16

CPU TIMING .............................................l-l7

Machine Cycles .........................................1-18

Interrupt Structure ......................................l.2O

ADDITIONAL REFERENCES ...................1 -22

.................................................

..................................1-14

1-6

1-1

Page 8

Page 9

ir&L

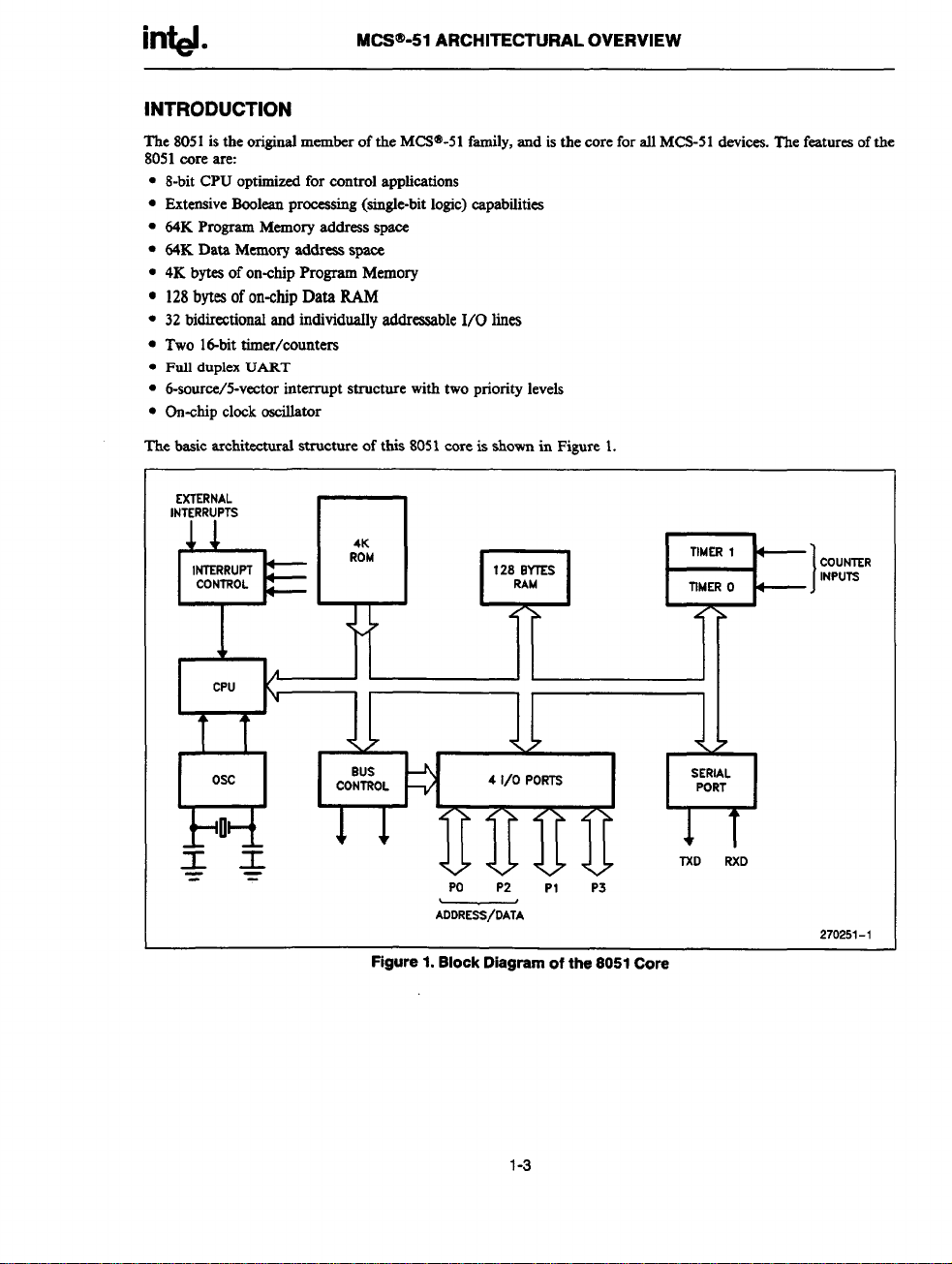

INTRODUCTION

The

8051 is the original member of the MCW-51 family, and is the core for allMCS-51 devices. The features of the

8051 core are -

●

8-bit CPU optimized for control applications

●

Extensive Boolean processing (Single-blt logic) capabtilties

●

64K Program Memory address space

●

64K Data Memory address space

●

4K bytes of on-chip Program Memory

●

128 bytesof on-chip Data RAM

●

32 bidirectional and individually addressable 1/0 lines

●

Two 16-bit timer/counters

●

Full duplex UART

●

6-source/5-vector interrupt structure with two priority levels

●

On-chip clock oscillator

The basic architectural structure of this 8051 core is shown in Figure L

EXTERNAL

INTERRUPTS

,,

M~@.51 ARCHITECTURAL OVERVIEW

I

I

COUNTER

INPUTS

w II

BUS

CONTROL

11

H

4 1/0 PORTS

Po P2 PI P3

AODRESS/DATA

Figure 1. Block Diagram of the 8051 Core

1-3

H

SERIAL

PORT

Q

TXO RXD

270251-1

Page 10

intd.

MCS@-51 ARCHITECTURAL OVERVIEW

1-4

Page 11

i~.

MCS@’-5l ARCHITECTURAL OVERVIEW

1-5

Page 12

i~.

M~@.51 ARCHITECTURAL OVERVIEW

PROORAMMrhtosv

* ----------- --------------

8

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

I

1

I

o

8

0

0

0

8

0

0

9

I

I

I

,

1

I

:

#

o

0

1

0

@

*

I

:

●-

--- -------- -------- -.!

(REM ONLY)

FFFFw

T -

EXTERNAL

G=o m.1

2STERNAL

0000

IN7ERNAL :

Figure 2. MCW’-51 Memory Structure

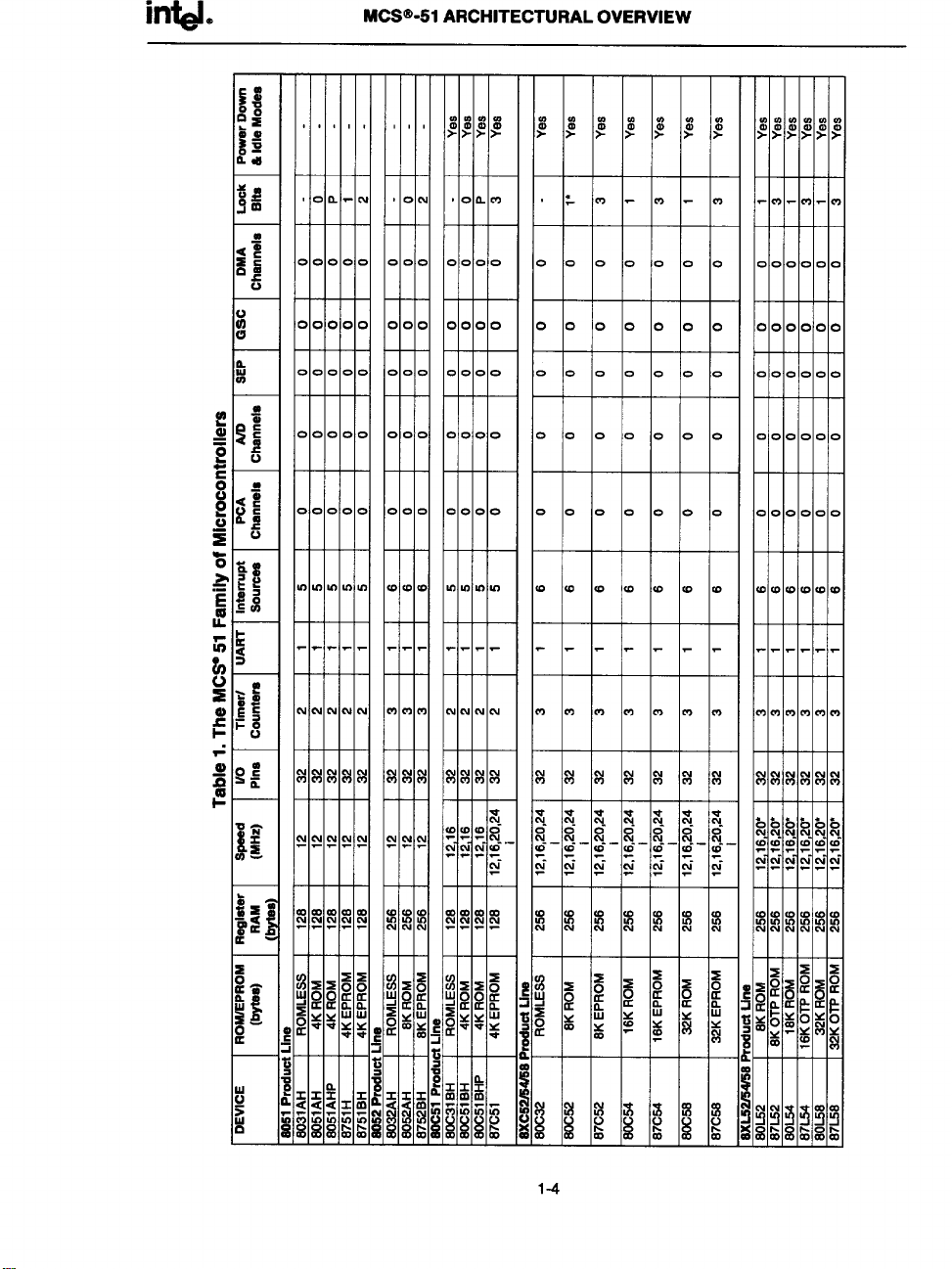

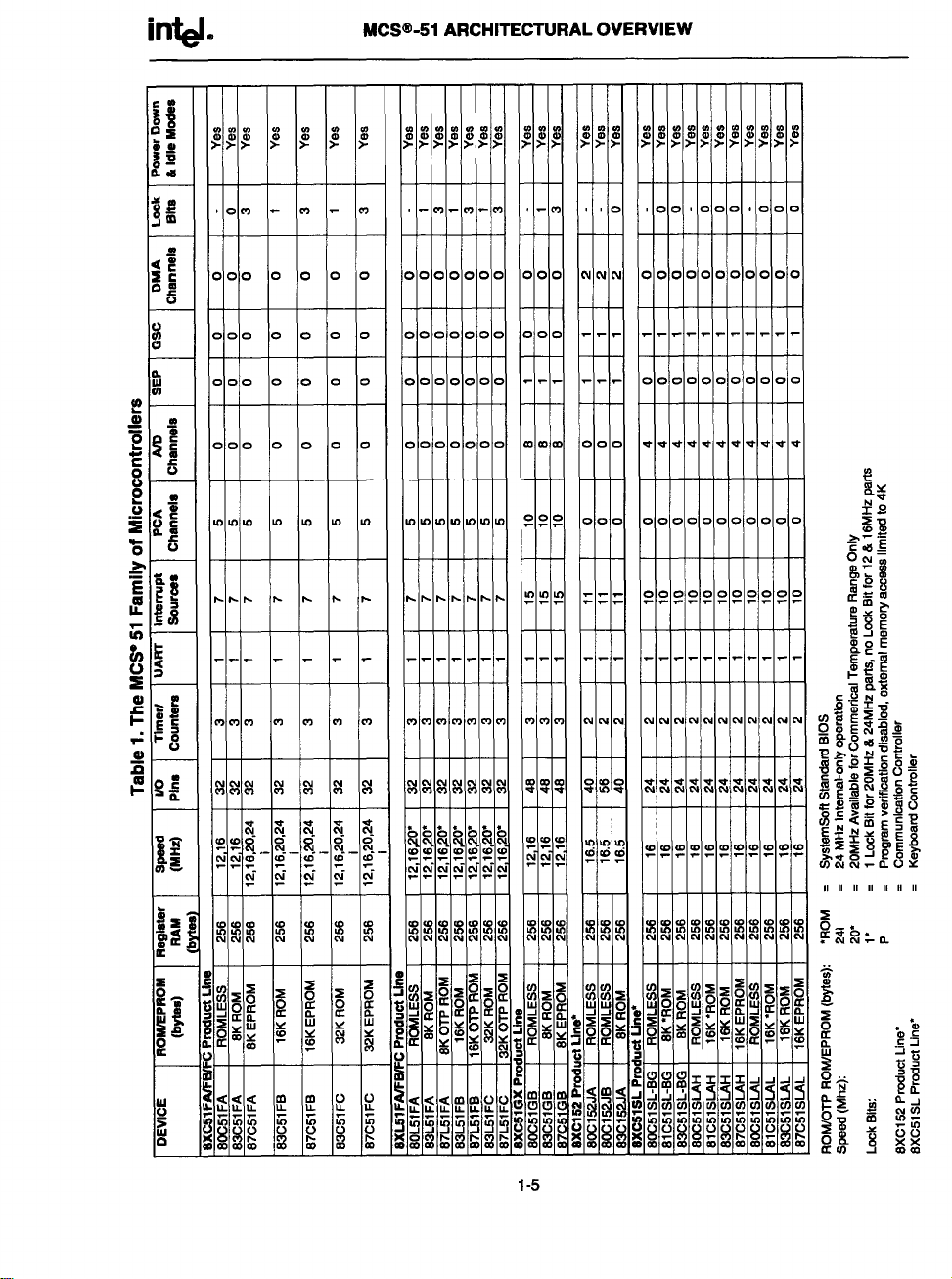

CHMOS Devices

Functionally, the CHMOS devices (designated with

“C” in the middle of the device name) me all

compatible with the 8051, but being CMOS, draw less

current than an HMOS counterpart. To further exploit

the power savings available in CMOS circuitry, two re-

duced power modes are added

● Software-invoked Idle Mode, during which the CPU

is turned off while the RAM and other on-chip

peripherals continue operating. In this mode, current draw is reduced to

about 15% of the current

drawn when the device is fully active.

● Software-invoked Power Down Mode, during which

all on-chip activities are suspended. The on-chip

RAM continues to hold its data. In this mode the

device typically draws less than 10 pA.

Although the 80C51BH is functionally compatible with

its HMOS counterpart, s~lc differeneea between the

two types of devices must be considered in the design of

an application circuit if one

wiaheato ensure complete

interchangeability between the HMOS and CHMOS

devices. These considerations are discussed in the Ap

plieation

Note AP-252, “Designing with the

80C5lBH.

fiuy

OATAMEMORY

------------------------ . . . . .

t

$

s

8

I

I

1

1

1

I

8

1

1

I

I

1

1

I

1

1

:

1

o

1

#

8

1

9

1

8

1

1

8

1

0

I

0

1

9

1

t

1

#

I

I

,

,

1

B

I

: FfH: ------

I

0:

9,

:

e,

9

0

0

9

9

8

*

I

1

I

I 00

,1+

I

1

●-------- --------- ..- -. -.-:

(RW/WRlT2)

IN7ERNM

EXIERNALm

0000

8

8

I

I

0

I

*

0

I

I

#

I

I

I

I

-

I

I

1

:

1

I

I

I

1

I

1

1

0

1

J:

1

1% tiR

MEMORY ORGANIZATION IN MCS@-51 DEVICES

Logical Separation of Program and

Data Memory

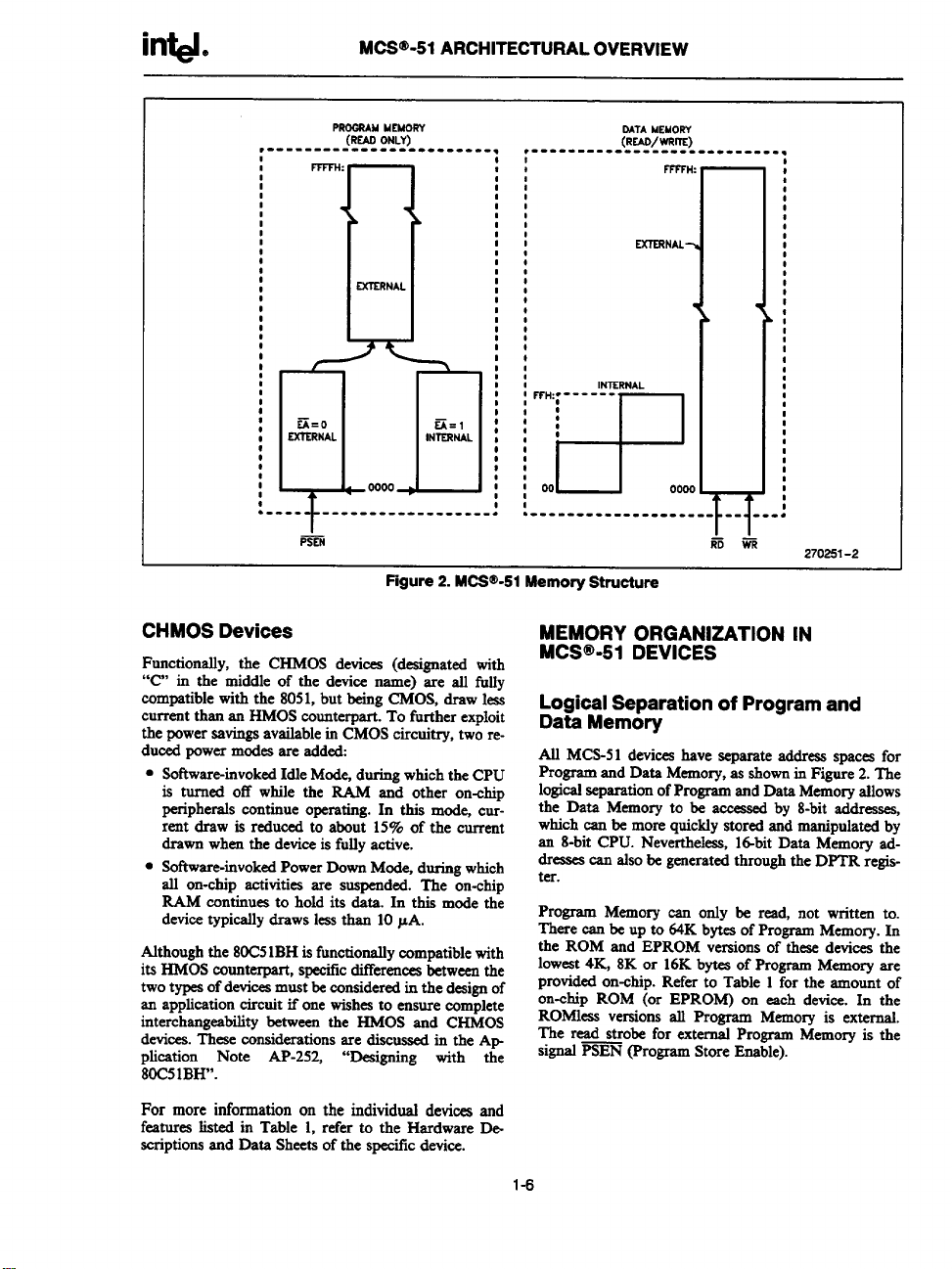

AU MCS-51 devices have separate address spacea for

Program and Data Memory, as shown in Figure 2. The

logical separation of Program and Data Memory allows

the Data Memory to be acceased by 8-bit addressea,

which can be more quickly stored and manipulated by

an 8-bit CPU. Nevertheless, ld-bh Data Memory addresses can also be generated through the DPTR register.

Program Memory can only be read, not written to.

There can be up to 64K bytes of Program Memory. In

the ROM and EPROM versions of these devices the

loweat 4K, 8K or 16K bytes of Program Memory are

provided on-chip. Refer to Table 1 for the amount of

on-chip ROM (or EPROM) on each device. In the

ROMleas versions all Program Memory is external.

The read strobe for external Program Memory is the

signal PSEN @rogram Store Enable).

270251-2

For more information on the individual devices and

features listed in Table 1, refer to the Hardware De

scriptions and Data Sheets of the specific device.

1-6

Page 13

intel.

MCS@-51 ARCHITECTURAL OVERVIEW

Data Memory occupies a separate addrexs space from

%OgrCt122 hkznory. Up to 64K bytes of exterttd RAM

can be addreased in the externrd Data Memo~.

The CPU generatea read and write signals RD and

~, as needed during external Data Memory accesses.

External Program Memory and external Data Memory

~~ combined if-desired by applying the ~ ~d

PSEN signals to the inputs of an AND gate and using

the output of the gate as the read strobe to the external

Program/Data memory.

ProgramMemory

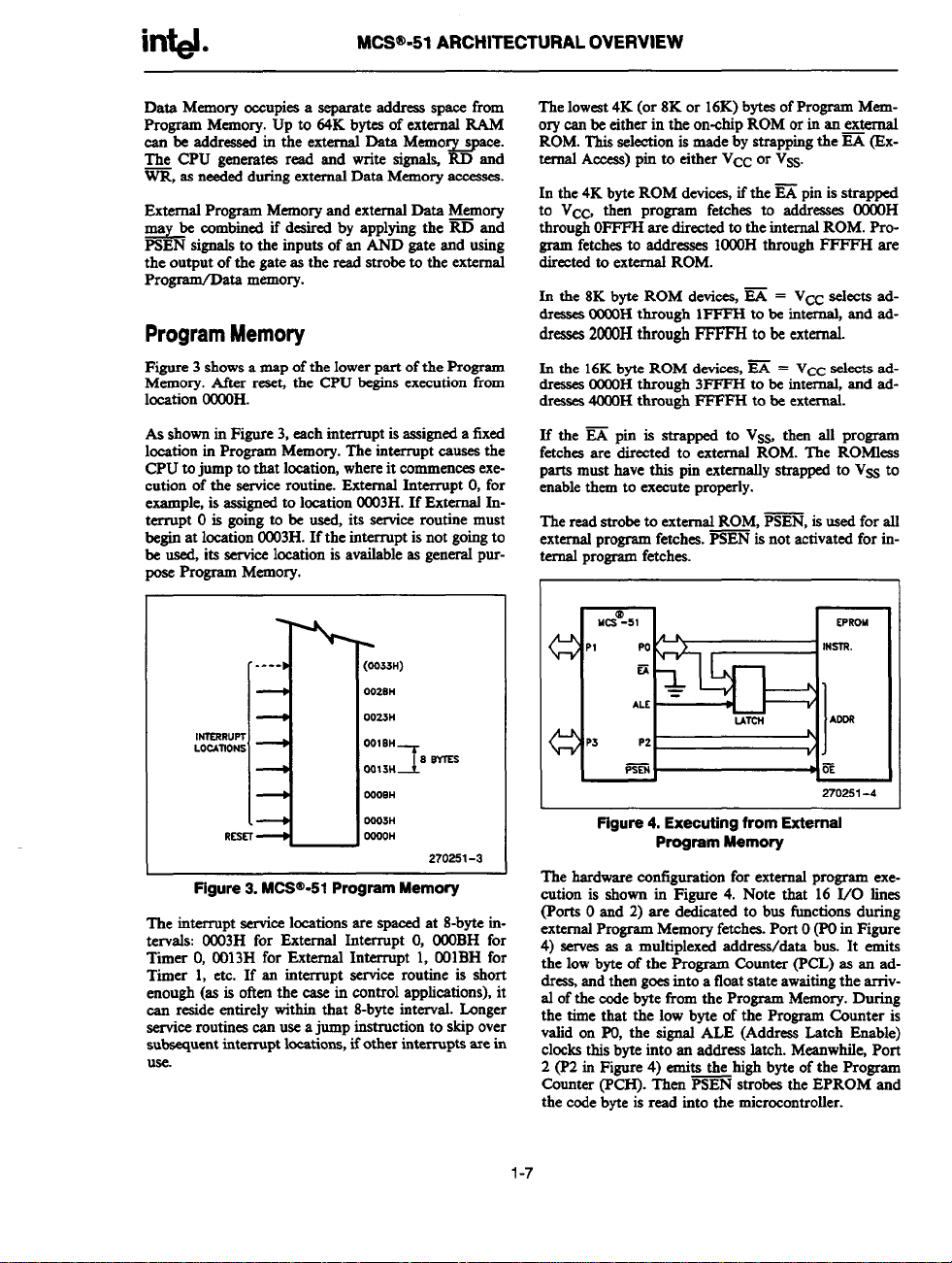

Figure 3 shows a map of the lower part of the Program

Memory. After reset, the CPU begins execution from

location OWOH.

AS shown in F@ure 3, each interrupt is

location in Program Memory. The interrupt causes the

CPU to jump to that location, where it commences execution of the serviee routine. External Interrupt O,for

example, is assigned to location 0003H. If External Interrupt O is going to & used, its service routine must

begin at location 0003H. If the interrupt is not going to

be used, its service location is available as general purpose Program Memory.

..-.

INTSRRUPT

LOCATIONS

R2S~

i

Figure 3. MCW’-51 Program Memory

The interrupt aeMce locations are spaced at 8-byte intervak 0U03H for External Interrupt O, 000BH for

Tmer O, 0013H for External Interrupt 1, 00IBH for

Timer 1, etc. If an interrupt service routine is short

enough (as is often the case in control applications), it

can reside entirely within

service routinea can use a jump instruction to skip over

subsequent interrupt locations, if other interrupts are in

use.

that 8-byte interval. Longer

assigned a tixed

&

(O033H)

002EH

002SH

00IBH

0013H

II

000SH

0003H

0000H

Ssvrm

270251-3

The lowest 4K (or SK or 16K) bytes of Program Memory can be either in the on-chip ROM or in an external

ROM. This selection is made by strapping the ~ (External Access) pin to either VCC or Vss.

In the 4K byte ROM devices, if the= pin is strapped

to VcC, then program fetches to addresses 0000H

through OFFFH are directed to the internal ROM. Program fetches to addresses 1000H through FFFFH are

directed to external ROM.

In the SK byte ROM devices, = = Vcc selects addresses (XtOOHthrough lFFFH to be internal, and ad-

dresses 2000H through F’FFFH to be external.

In the 16K byte ROM devices, = = VCC selects ad-

dresses 0000H through 3FFFH to be internal, and addresses 4000H through FFFFH to be external.

If the ~ pin is strapped to Vss, then all program

fetches are directed to external ROM. The ROMleas

parts must have this pin externally strapped to VSS to

enable them to execute properly.

The read strobe to externally: PSEN, is used for all

external oro.cram fetches. PSEN LSnot activated for in-

m%

‘s

m

=

ALE

l==

LArcn

Po

1

a’s ‘z~

Figure 4. Executing from External

Program Memory

The hardware configuration for external program execution is shown in Figure 4. Note that 16 I/O lines

(Ports O and 2) are dedicated to bus fictions during

external Program Memory f~hes. Port O(PO in Figure

4) servex as a multiplexed address/data bus. It emits

the low byte of the Program Counter (PCL) as an address, snd then goes into a float state awaiting the arrival of the code byte from the Program Memory. During

the time that the low byte of the Program Counter is

valid on PO, the signal ALE (Address Latch Enable)

clocks this byte into an address latch. Meanwhile, Port

2 (P2 in Figure 4) emits the high byte of the Program

Countex (WI-I). Then ~ strobex the EPROM and

the code byte is read into the microcontroller.

EPROM

INSTR.

AOOR

1

270251-4

1-7

Page 14

MCS@-51 ARCHITECTURAL OVERVIEW

Program Memory addresses are always 16 bits wide,

even though the aotual amount of Program Memory

used ntSy be kSS than 64K bytes. External prOq

exeoutiorssacrifices two of the 8-bit ports, PO and P2, to

the fisnction of addressing the Program Memory.

Data Memory

Theright

nal Dats Memory spaces available to the MCS-51 user.

F@ure 5 shows a hardware configuration for accessing

up to 2K bytes of external RAM. The CPU in this ease

is executing from internal ROM. Port O serves as a

multiplexed address/data bus to the RAM, and 3 lines

of Port 2 are bein~d to page the RAM. The CPU

generates = and WR signals as needed during exter-

ial WM

There ean be up to 64K bytea of external Data Memo-

ry. External Data Memory addresses can be either 1 or

2 bytes wide. One-byte addresses are often used in cxm-

junction with one or more other 1/0 lines to page the

R4M, as shown in Figure 5. Two-byte addresws ears

atso be used, irz which case the high address byte is

emitted

half of Figure 2 shows the internal and exter-

ameases. -

1’

Figure 5. Accessing External Data Memory.

If the Program Memory is Internal, the Other

Bits of P2 are Available as 1/0.

at Port 2.

I

270251-5

I

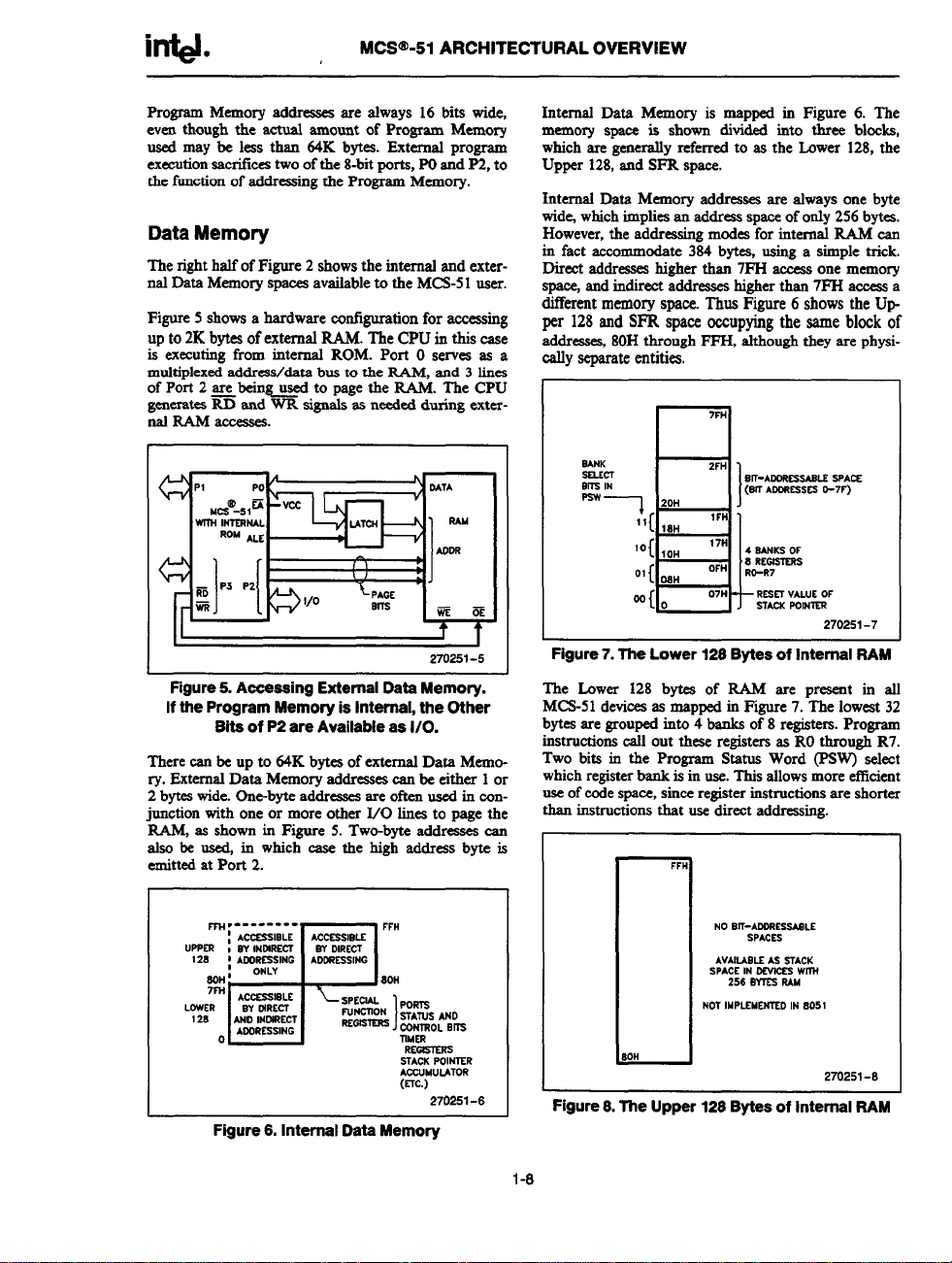

Internal Data Memory is mapped in Figure 6. The

memory space is shown divided into three bloeka,

which are generally referred to as the Lower 128, the

Upper 128, and SFR space.

Internal Data Memory addresses are always one byte

Wid%which implies an address space of only 256 bytes.

However, the addressing modes for intemssl RAM ean

in fact seeommodate 384 bytes, using a simple trick.

Direct addresses higher than 7FH awes one memory

space, and indirect addresses higher than 7FH access a

different memory space. Thus Figure 6 shows the Up-

per 128and SFR

addrq

cally separateentities;

BANK

SELECT

BRS IN

‘1 20H

Figure 7. The Lower 128 Bytes of internal RAM

The

Imwer 128 bytes of W are present in all

MCS-51 devices as mapped in F@ure 7. The lowest 32

bytes are grouped into 4 banks of 8 registers. Program

instructions call out these registers as RO through R7.

Two bits in the Program Status Word (PSW) seleet

which register bank is in use. This allows more effieient

use of code space, since register instructions are shorter

than instructions that use direet addreasiig.

spaceoccupyingthe ssme blockof

80H throu~ FFH, slthoud they are physi-

7FH

n

2FH

SN-ACORESSASLSSPACE

(S~ A~ESSES O-7F)

1

“{ lSH

‘0{ 10H

0’{ OBH

eo{o

1FH

17H

OFH

07H RESETVALUEOF

Ill

FFH

4 SANKSOF

8 REGIS7SRS

RO-R7

S7ACKPOIN7ER

270251-7

~:.. .-... -

, AC=IELE ACCESSIBLE

UPP~ , SV INDIREC7 BV OIRECT

: AtORESSING AODRSSSING

ONLY

SDH9 80H

‘m ACCESSIBLE

LOWER

SY 01REC7

128

ANOINC+REC7

o AGGRESSING

EP

Figure 6. Internal Data Memory

SPWAL

NC710N &oAmm~o

W

‘E~m CONTROLems

FFH

1

TIMER

RE—

STACKiolN7ER

ACCUMULATOR

(’nC.)

270251-6

NO SIT-AOORSSSABLE

SPACES

AVAIUBLE AS S7ACK

SPACEIN DEVICESWMI

256 BWES RAM

NOTIMPLE14EN7EDIN 8051

80H

I

Figure 6. The Upper 128 Bytes of Internal RAM

I-6

270251-8

Page 15

in~.

M~@-51 ARCHITECTURAL OVERVIEW

CTIAC]

CARRYFLAGRECEIVESCMi/fmw;

FROU BIT 1 Of ALU OPERANOS

AUXILIARYCARRYFLAGRECEIVES

CARRYOUT FROM B17 1 OF

AOOMON OPERANOS

GENERALPURPOSES7ATUSFLAG

REGtS7ERBANKSW’% t

-. .- . . . . . .- . . . . . . .. . . . ------ ----

Figure 1u. Psw (Progrsm ssssus worn) Register m mc5w-51 t2evtces

1

Psw6—

nw5

FOIRSIIRBO[ OVI

b a a

The next 16bytea above the register bankBform a block

of bit-addressable memory apace. The MCS-51 instruction set includes a wide seleetion of single-blt instructions, and the 128 bits in this area can be directly addressed by these irsstmctions. The bit addreascs in this

area are W)H through 7FH.

All of the bytes in the LQwer 128 can be accessed by

either direct or indirect addressing. The Upper 128

(Figure 8) can only be accessed by indirect addressing.

The Upper 128 bytes of RAM are not implemented in

the 8051, but me in the devices with 256bytea of RAM.

(Se Table 1).

Figure 9 gives a brief look at the Special Funotion Register (SFR) space. SFRS include the Port latchea, timers, pe2iphA controls, etc. l%ese registers can only&

-seal by dmect addressing. In general, all MCS-51

microcontrollers have the same SFRB as the 8051, and

at the same addresses in SFR space. However, enhancements to the 8051 have additional SFRB that are not

present in the 8051, nor perhaps in other proliferations

of the family.

“u

EOH

80H

AOH

90H

m

PORT.3

Porn 2

POR7 1

B

RE~MAPPSO POR7S

AOORESSES7NATENDIN

OH OR EN ARCALSO

B~-AOORESSABLE

-POR7 PINS

-ACCUMULATOR

-Psw

(E7c.)

J-A--I

270251-9

Figure 9. SFR Spsce

P

I

A

*

I

A

KWO

PARllYOFACCLWUIATORSS7

~ NARoWARCTO 1 IF IT CONTAINS

AN 000 NUMBEROF 1S, OTHERWISE

171SRESE7TO0

— Psw 1

USEROEFINABLEFUG

Psw 2

OVERFLOWFIAO SET BY

ARITIMCWOPERAl!ONS

Psw3

REOSJERBANKSELECTBll O

270251-10

!%teers addresses in SFR mace are both byte. and bit.

addressable. The blt-addre&able SFRS are ‘those whose

address ends in 000B. The bit addresses in this ares are

throUgh FFH.

80H

THE MCS@-51 INSTRUCTION SET

All

members of the MCS-51 family execute the same

instruction set. The MCS-51 instruction set is optimized for 8-bit control applications. It provides a variety of fast addressing modes for accessing the internal

MM to facilitate byte operations on small data structures. The instruction sd provides extensive support for

one-bit variables as a separate data t% allowing direct

blt manipulation in control and logic systems that require Boolean prmessirsg.

An overview of the MCS-51 instruction set is prrsented

below, with a brief description of how certain instructions might be used. References to “the assembler” in

this discussion are to Intel’sMCS-51 Macro Assembler,

ASM51. More detailed information on the instruction

set can be found in the MCS-51 Macro Assembler User’s Guide (Grder No. 9W3937 for 1S1SSystems, Grder

No. 122752 for DOS Systems).

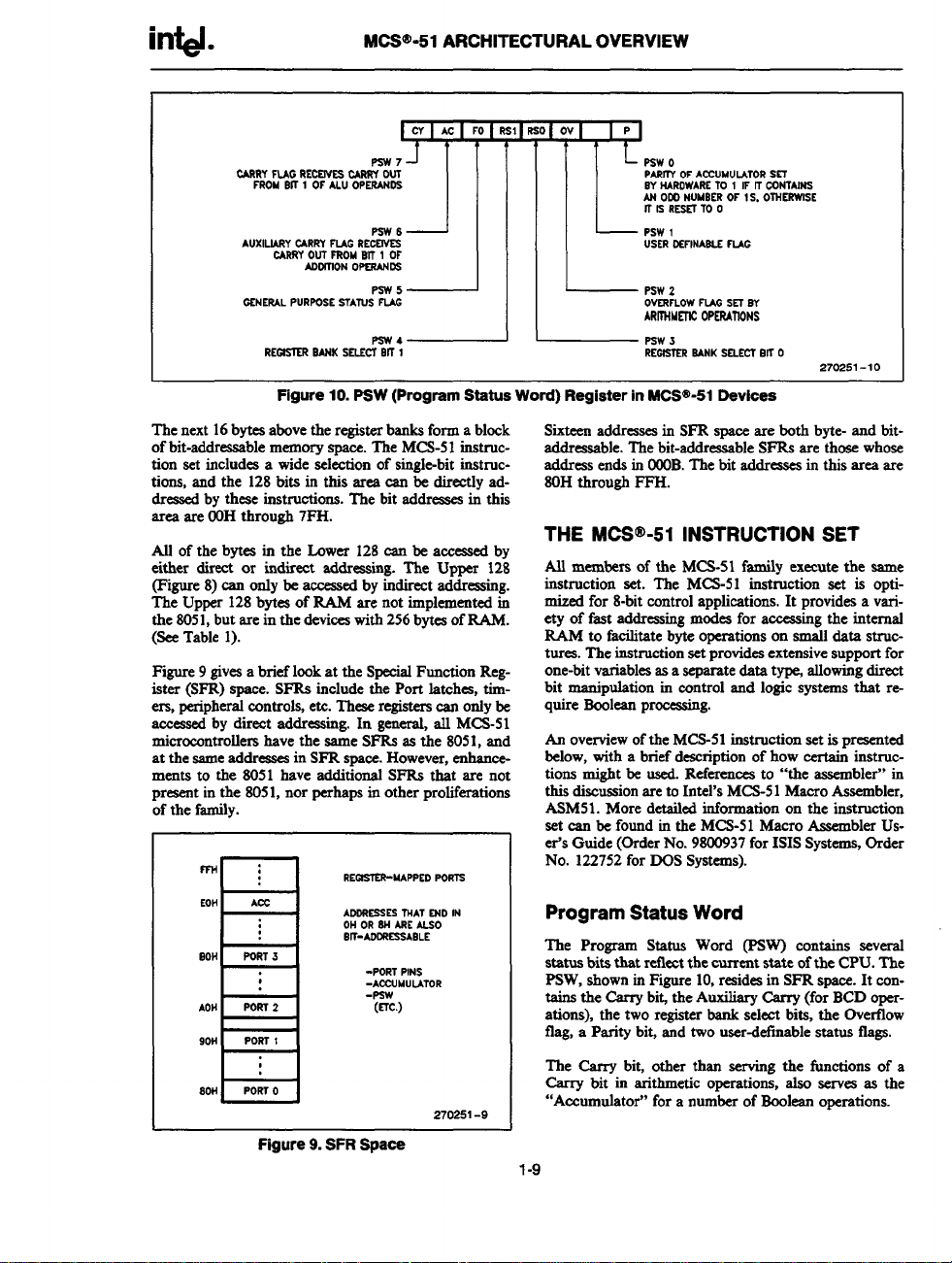

Program Status Word

The Program Status Word (PSW) contains several

status bits that reflect the current state of the CPU. The

PSW, shown in Figure 10, resides in SFR space. It contains the Csrry bi~ the Auxdiary Carry (for BCD operations), the two register bank select bits, the Gvesflow

flag, a Parity bit, and two userdefinable status tlags.

The Carry bit, other than serving the functions of a

Carry bit in arithmetic operations, also sesws as the

“Accumulator” for a number of Boolean operations.

1-9

Page 16

MCS@-51 ARCHITECTURAL OVERVIEW

The bits RSOand RSl are wed to select one of the four

register banks shown in Figure 7. A number of instructions refer to these RAM locations as RO through R7.

The selection of which of the four banks is being referred to is made on the basis of the bits RSO and RS1

at execution time.

The Parity bit reflects the number of 1s in the Accumulator P = 1if the Accumulator contains an odd number of 1s, and P = O if the Accumulator contains an

even number of 1s.Thus

thenumber of 1s in the Accu-

mulator plus P is always even.

Two bits in the PSW are uncommitted and maybe used

as general purpose status flags.

Addressing Modes

The

addressing modes in the MCS-51 instruction set

are as follows

DIRECT ADDRESSING

In direct addressing the operand is specitied by an 8-bit

addreas field in the instruction. Only internal Data

RAM and SFRS can be directly addressed.

INDIRECT ADDRESSING

In indirect addressing the instruction specifies a register

which contains the address of the operand. Both internal and external RAM can be indirectly addressed.

The address register for 8-bit addresses can be RO or

RI of the selected register bank, or the Stack Pointer.

The addreas register for id-bit addresses can only be the

id-bit “data pointer” register, DPTR.

REGISTER INSTRUCTIONS

The

register banks, containing registers ROthrough R7,

can be accemed by certain instructions which carry a

3-bit register specification within the opcode of the instruction. Instructions that access the registers this way

are code efficient, since this mode elirninatez an addreas

byte. When the instruction is executedj one of the eight

registers in the selected bank is amessed. One of four

banks is selected at execution time by the two bank

select bits in the PSW.

IMMEDIATE CONSTANTS

The value of

a constant can follow the opcode in Pro-

gram Memory. For example,

MOV A, # 100

loads the Accumulator with the decimal number 100.

The same number could be specified in hex digitz as

64H.

INDEXED ADDRESSING

only

Program Memory can be amessed with indexed

addressing, and it can only be read. This addressing

mode is intended for reading look-up tables in Program

Memory. A Id-bit base register (either DPTR or the

Program Counter) points to the base of the table, and

the Accumulator is setup with the table entry number.

The address of the table entry in Program Memory is

formed by adding the Accumulator data to the base

pointer.

Another type of indexed addreaaing is used in the “case

jump” instruction. In this case the destination address

of a jump instruction is computed as the sum of the

base pointer and the Accumulator &ta.

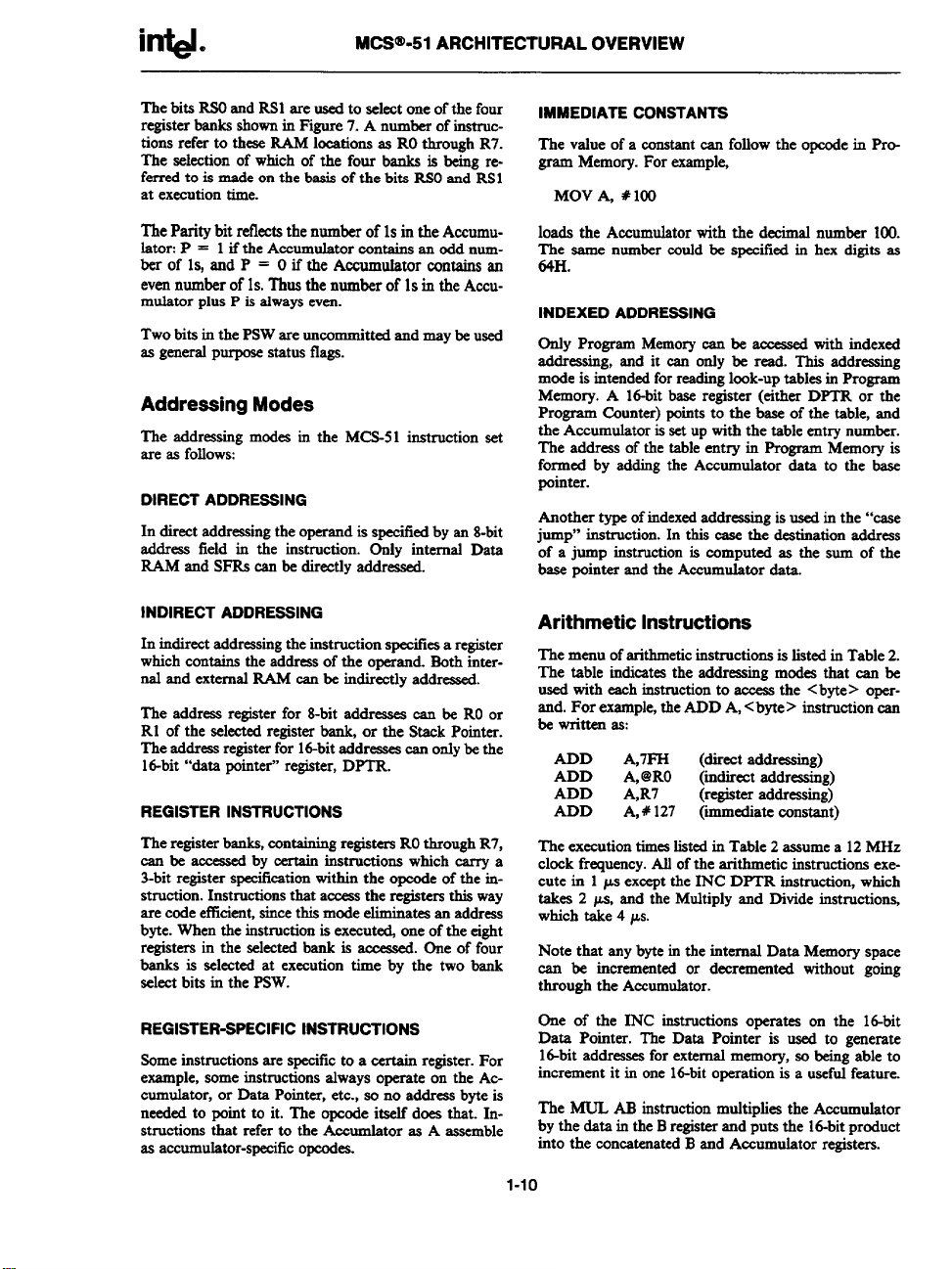

Arithmetic Instructions

The

menu of arithmetic instructions is listed in Table 2.

The table indicates the addressing modes that can be

used with each instruction to access the <byte> operand. For example, the ADD A, <byte> instruction can

be written as

ADD A,7FH

ADD A,@RO (indirect addressing)

ADD A,R7 (register addressing)

ADD A, # 127 (iediate constant)

The execution times listed in Table 2 assume a 12 MHz

clock frequency. All of the arithmetic instructions execute in 1 ps except the INC DPTR instruction, which

takes 2 W, snd the Multiply and Divide instructions,

which take 4 ps.

Note that any byte in the internal Data Memory space

can be incremented or decremented without going

through the Accumulator.

(directaddressing)

REGISTER-SPECIFIC INSTRUCTIONS

Some instructions are specific to a certain register. For

example, some instructions always operate on the Accumulator, or Data Pointer, etc., so no address byte is

needed to point to it. The opcode itself does

that.In-

structions that refer to the Accurrdator as A assemble

as accumulator-specific opcmdes.

One of the INC instructions operates on the Id-bit

Data Pointer. The Data Pointer is used to generate

16-bit addresses for external memory, w being able to

increment it in one 16-bit operation is a usefirl feature.

The MUL AB instruction multiplies the Accumulator

by the data in the B register and puts the Id-bit product

into the concatenated B and Accumulator registers.

1-1o

Page 17

inl#

Mnemonic Operation

ADD A,<byte> A = A + <byte>

I ADDOA, <byte> I A= A+< byte>+C I X I X I X I X ] 1 I

SUBB A, <byte> A= A–<byte>-C

INC A

I INC . <byte>

I lhJC DPTR I DPTR = DpTR + 1 I

I DEC A

DEC <byte>

MUL

AB B.A=Bx A ACC and B only 4

DIV AB

I

IDAA I Decimal Adjust

MCS@-51 ARCHITECTURAL OVERVIEW

Table 2 A Ust of the MCS@I-51 Arithmetic Instructions

Addressing Modes

Dk I Ind Rq lmm

x

x x

I A=A+l I Accumulator onlv I 1

<byte> =<byte>+l I X I X I X I

I

I A= A-l

<byte> = <byte> – 1

A = Int [A/B]

B = MOd[A/Bl

I

I

x

I

x

Data Pointer only

Accumulator only

x x

I

ACC and

Accumulatoronly

B only

x x

x

x 1

Execution

Time (@

11-1

121

Ill

I

I

Ill

1

1

4

I

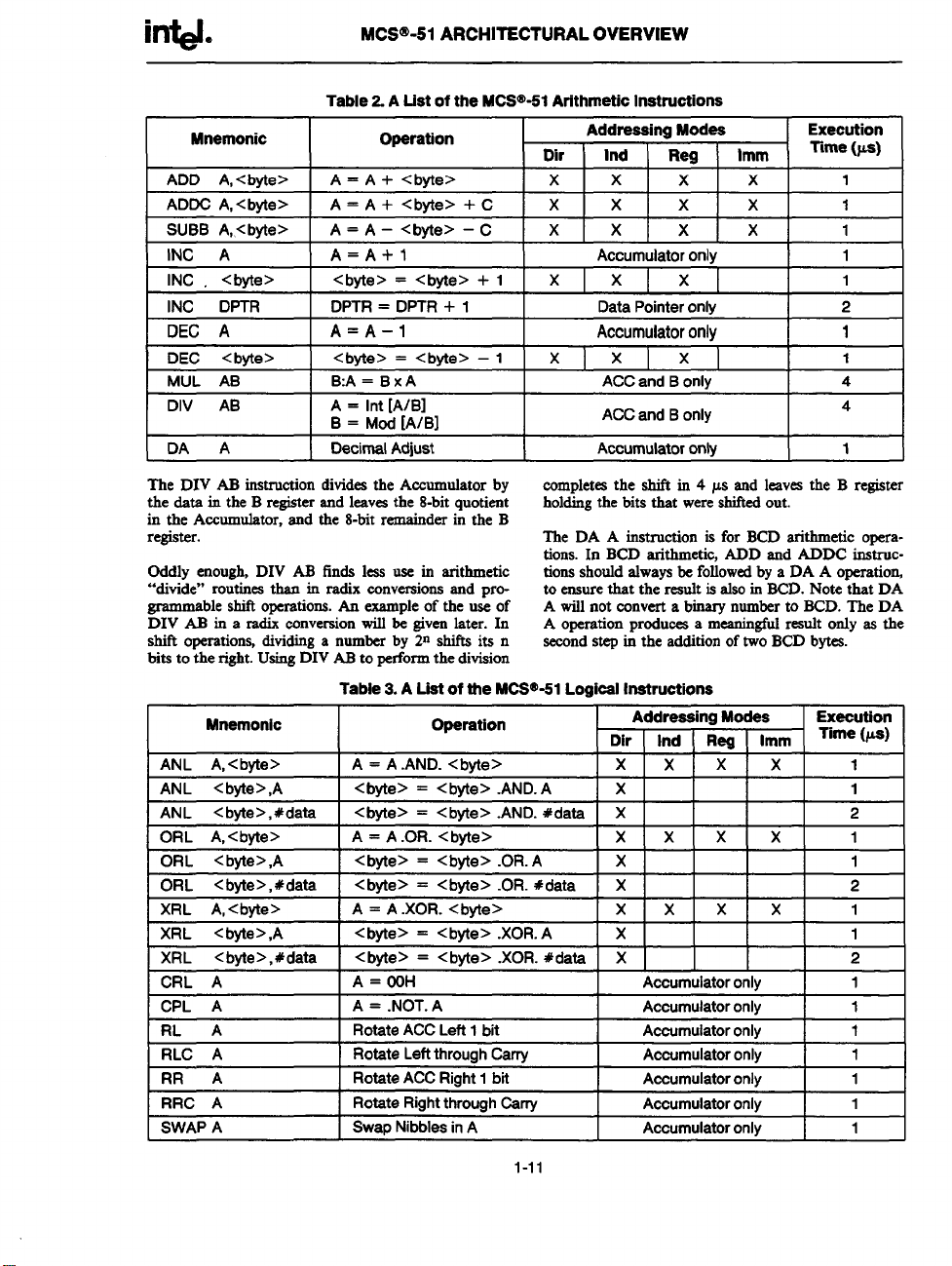

The DIV AB instruction divides the Accumulator by

the data in the B register and leevea the 8-bit quotient

in the Accumulator, and the 8-bit remainder in the B

register.

Oddly enough, DIV AB finds lees use in arithmetic

“divide” routines than in radix eonversions and pro-

~ble shift operstioILs. k example of the use of

DIV AB in a radix conversion will be given later. In

s~ operations, dividing a number by 2n shifts its n

bits to the right. Using DIV AS to perform the division

Table 3. A Uet of the MCS@J-51Logical Instructions

I

IRL A I Rotate ACC Left 1 bit I

Mnemonic

I

ANL A,< byte> A = A .AND. <byte> x x x x

ANL <byte>,A

ANL <bvte>, #data

ORL A,< byte>

ORL <bvte>,A

ORL <byte>, #data

XRL A,< byte> A = A .XOR. <byte> X1X1X

XRL <byte>,A

XRL <byte>, #data

CRL A

CPL A

RLC A

RR A

RRC A

SWAP A

<byte> = <byte> .AND. A

<byte> = <byte>

A = A.OR. <byte>

I

<byte> = <byte> .OR. A

<byte> = <byte> .OR. #data

I

<byte> = <byte> .XOR. A

I

<byte> = <byte> .XOR. #data I X

A=OOH

A =

Rotate Left through Csrry

I

Rotate ACC Right

Rotate Right through Carry

Swap Nibbles in A

Operation

.NOT. A

1 bit

eompletcs the shift in 4 p.s and leaves the B register

holding the bits that were shifted out.

The DA A instruction is for BCD arithmetic opera-

tions. In BCD arithmetic, ADD and ADDC instructions should always be followed by a DA A operation,

to ensure that the

A will not convert a binary number to BCD. The DA

A operation produces a meaningfid

second step in the addition of two BCD bytes.

red is also in BCD. Note that DA

Addressing Modes

Dir

Ind I Reg I

x 1

.AND. #data

x 2

X1X1X1X

I

x 1

x

x

I

Accumulator only 1

Accumulator

Accumulator onlv

Accumulator only

I

Accumulator only 1

Accumulator only 1

Accumulator

only

onlv 1

result only as the

Imm

x

I

I

I

Ill

I

Execution

Time (ps)

1

1

2

1

1

2

1

1

I

1-11

Page 18

irrtel.

MCS@-51 ARCHITECTURAL OVERVIEW

Logical Instructions

Table 3 shows the list ofMCS-51 logical instructions.

The instructions that perform Boolean operations

(AND, OIL Exclusive OIL NOT) on bytes perform the

operation on a bit-by-bit bssis. That is, if the AecumuIator contains 001101OIB and <byte> contains

O1OIOOIIB,then

ANL

will leave the Accumulator holding OOO1OOOIB.

The addrcasing modes that can be used to access the

<byte> operand are

A, <byte> instruction may take any of the forms

ANL A,7FH (direct addressing)

ANL A,@Rl

ANL

ANL

AU of the logical instructions that are Accumulatorspecflc execute in lps (using a 12 MHz clock). The

othem take 2 ps.

Note that Boolean operations can be performed on any

byte in the lower 128 internal Data Memory space or

the SFR space using direct addressing, without having

to use the Accumulator. The XRL <byte >, #data instruction, for example offets a quick and easy way to

invert port bits, as in

XRL Pl,#oFFH

If the operation is in response to an interrupt, not using

the Accumulator saves the time and effort to stack it in

the service routine.

The Rotate instructions (3U & RLC A, etc.) shift the

Aeeurtmlator 1 bit to the MI or right. For a left rota-

tion, the MSB rolls into the LSB position. For a right

rotation, the LSB rolls into the MSB position.

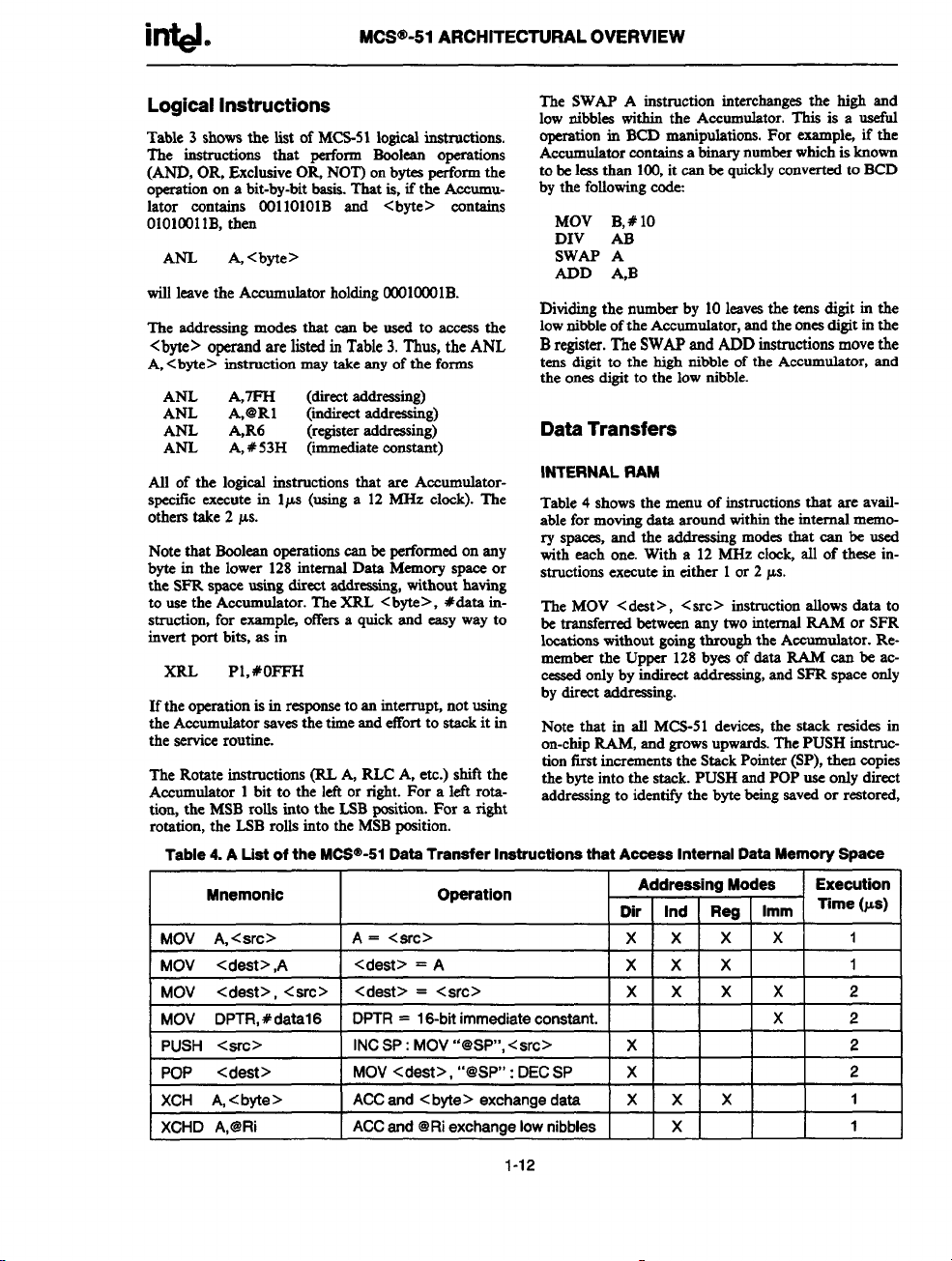

Table 4. A List of the MCS@-51 Data Tranafer Instructions that Access Internal Data Memory Space

MOV A, <src>

MOV <cleat> ,A

MOV <dest>, <src>

MOV DPTR,#data16

PUSH <WC>

POP

XCH A, <byte>

XCHD A,@Ri

A, <byte>

listedinTable 3. Thus, the ANL

A,R6 (register addressing)

A, # 53H (immediate constant)

Mnemonic Operation

<dest>

(indirect addressing)

A = <src>

<dest> = A

<dest> = <src>

DPTR = 16-bit immediate constant.

INCSP: MOV “@’SP’, <src>

MOV <dest>, “@SP”: DECSP x

ACCand <byte> exchange data

ACCand @Riexchange low nibbles

The SWAP A instruction interchanges the high and

low nibbles within the Accumulator. This is a useful

operation in BCD manipulations. For exampie+ if the

Accumulator contains a binary number which is known

to be leas thsn IQ it can be qnickly converted to BCD

by the following code:

MOV B,# 10

DIV AB

SWAP A

ADD A,B

Dividing the number by 10 leaves the tens digit in the

low nibble of the Accumulator, and the ones digit in the

B register. The SWAP and ADD instructions move the

tens digit to the high nibble of the Accumulator, and

the onea digit to the low nibble.

Data Transfers

INTERNAL RAM

Table 4 shows the menu of instructions that are available for moving data around within the internal memo-

ry spaces, and the addressing modes that can be used

with each one. Wkh a 12 MHz clock, all of these instructions execute in either 1or 2 ps.

The MOV < dest >, < src > instruction allows dats to

be transferred between any two internal RAM or SFR

lwations without going through the Accumulator. Remember the Upper 128 byes of data RAM can be acwased only by indirect addressing, and SFR space only

by direct addressing.

Note that in all MCS-51 devices, the stack resides in

on-chip RAM, and grows upwards. The PUSH instruc-

tion first increments the Stack Pointer (SP), then copies

the byte into the stack. PUSH and POP use only dkcct

addressing to identify the byte being

Addressing Modes

Ind Reg

Dir

saved or restored,

Execution

Time (ps)

Imm

x x x x

x x x

x x x x

x

x

x x x

x

1

1

2

2

2

2

1

1

1-12

Page 19

i~o

MCS@-51 ARCHITECTURAL OVERVIEW

but the stack itself is accessed by indirect addressing

using the SP register. This means the stack can go into

the Upper 128, if they are implemented, but not into

SFR space.

In devices that do not implement the Upper 128,if the

SP points to the Upper 128,PUSHed bytes are lost, and

POPped bytes are indeterminate.

The Data Transfer instructions include a id-bit MOV

that can be used to initialise the Data Pointer (DPTR)

for look-up tables in Program Memory, or for Id-bit

external Data Memory accesw.

The XCH A, <byte> instruction causes the Amu-

lator snd addressed byte to exchsnge data. The

A,@Ri instruction is similar, but only the low nibbles

are involved in the exchange.

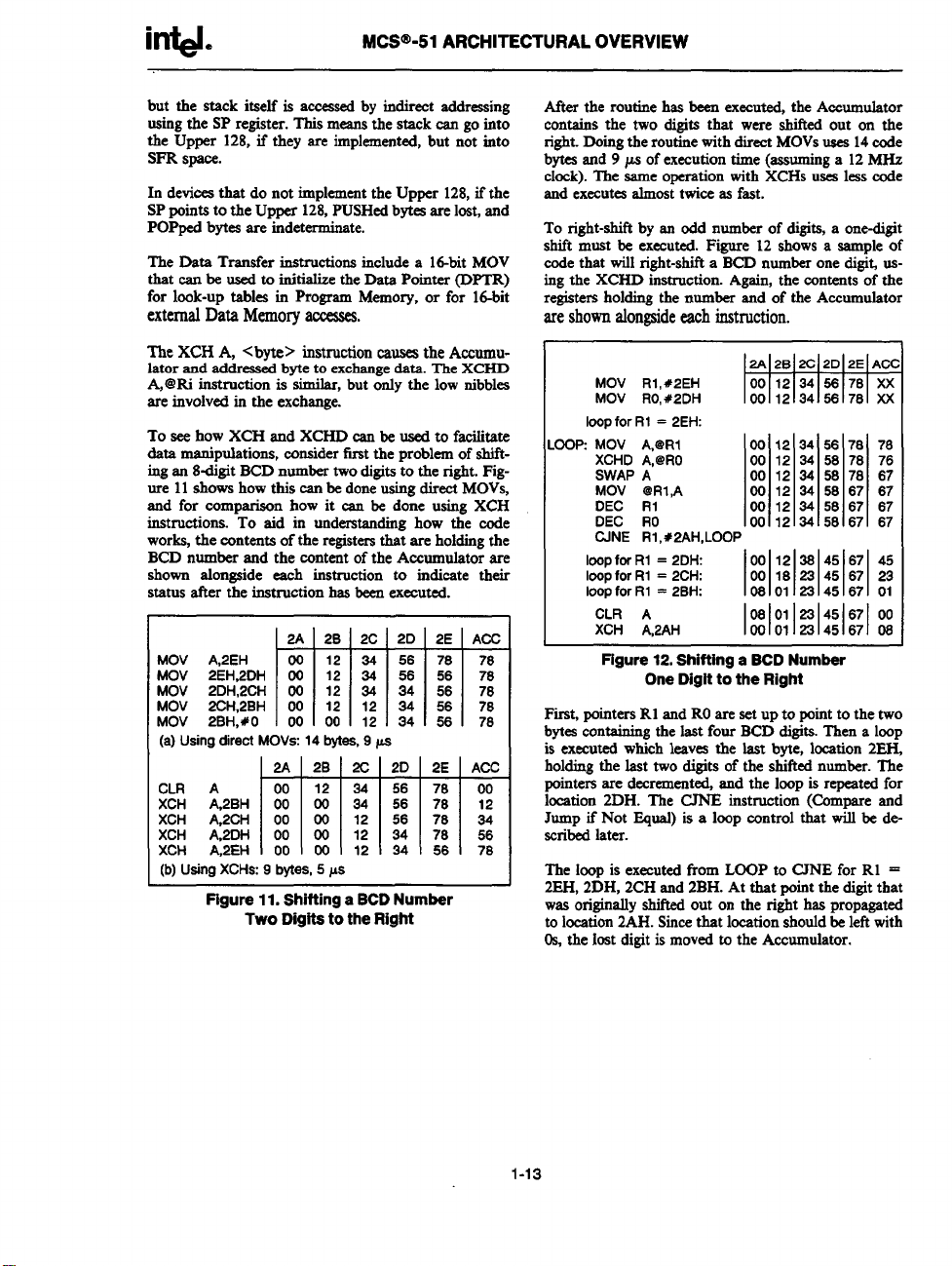

To see how XCH and XCHD can be used to fatitate

data manipulations, consider first the problem of shit%ing an 8digit BCD number two digits to the right. Figure 11 shows how this can be done using direct MOVS,

and for comparison how it can be done using XCH

instructions. To aid in understanding how the code

works, the contents of the registers that are holding the

BCD number and the content of the Accumulator are

shown alongside each instruction to indicate their

status after the instruction has been executed.

MOV A,2EH

MOV 2EH2DH % ;; : % ~

MOV 2CH:2BH 00 12

n3JMm

(a) Using direct MOVS 14 bytes, 9 ps

~

gm

(b) Using XCHS 9 bytes, 5 ps

Figure 11. Shifting a BCD Number

Two Dlgite to the Right

. .

XCHD

Atler the routine has been executed, the Accumulator

contains the two digits that were shitled out on the

right. Doing the routine with direct MOVSuses 14code

bytes and 9 ps of execution time (assuming a 12 MHs

clock). The same operation with XCHS uses less code

and executes almost twice as fast.

To right-shift by an odd number of digits, a one-digit

shift must be executed. Figure 12 shows a sample of

code that will right-shii a BCD number one digi~ using the XCHD instruction. Again, the contents of the

registers holding the number and of the Accumulator

areshownalongsideeachinstruction.

First, pointers RI and ROare setup to point to the two

bytea containing the last four BCD digits. Then a loop

is executed which leaves the last byte, location 2EIL

holding the last two digits of the shifted number. The

pointers are decrernented, and the loop is repeated for

location 2DH. The CJNE instruction (Compare and

Jump if Not Equal) is a loop control that will be described later.

The loop is executed from LOOP to CJNE for R1 =

2EH, 2DH, 2CH and 2BH. At that point the digit that

was originally shii out on the right has propagated

to location 2AH. Siice that location should be left with

0s, the lost digit is moved to the Accumulator.

MOV Rl, #2EH

MOV RO,#2DH

loop for R1 = 2EH

.00P MOV A,@Rl 00 12 34 56 78 76

XCHD A,@RO

SWAP A

MOV @Rl,A

DEC RI

DEC RO

CJNE Rl,#2AH,LOOP

Imp for RI = 2DH

loop for R1 = 2CH:

ioop for RI = 2BH:

CLR A

XCH A,2AH

Figure 12. Shifting a SCD Number

One Digit to the Right

m

00 12 34 56 78 76

00 12 34 58 78 67

00 12 34 58 67 67

00 12 34 58 67 67

00 12 34 56 67 67

00 12 36 45 67 45

00 18 23 45 67 23

0s

01 22 45 67 01

06

01 23 45 67 00

00 01 23 45 67 06

1-13

Page 20

M~@.51 ARCHITECTURAL OVERVIEW

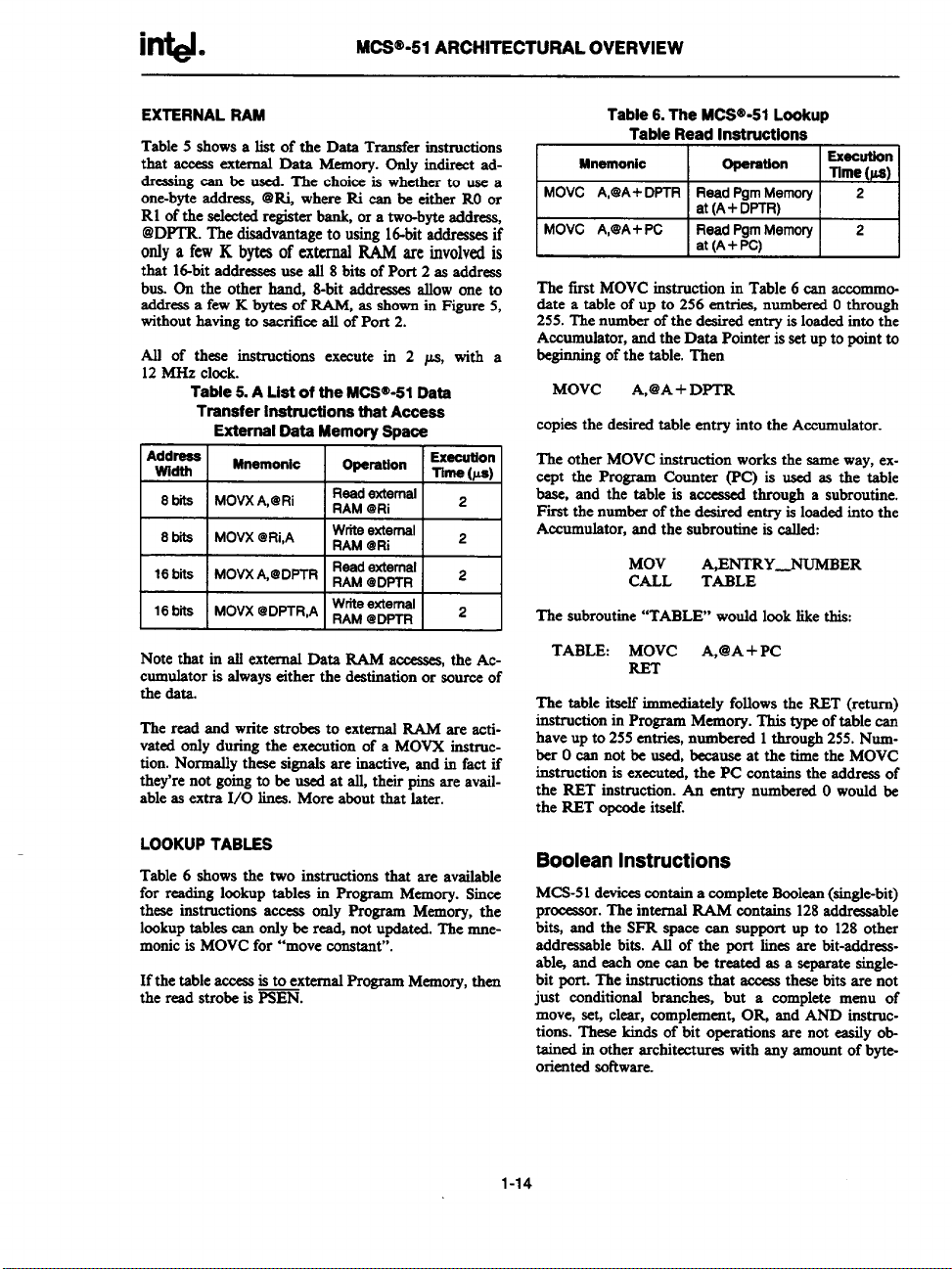

EXTERNAL RAM

Table 5 shows a list of the Data Transfer inatmctions

that acceas external Data Memory. Only indirect ad&easing can be used. The choice is whether to use a

one-byte address, @M where Ri can be either RO or

RI of the selected register bank, or a two-byte address,

@DPTR. The disadvantage to using 16-bit addresses if

only a few K

16-bit addresses use alf 8 bits of Port 2 as addreas

that

bytesof externalRAMare involvedis

bus. On the other hand, S-bit addresses allow one to

address a few K bytes of RAM, as shown in Figure 5,

without having to sacrifice all of Port 2.

Alf of these instructions execute in 2 pa, with a

12 MHz clock.

Tabfe 5. A

Trsnafer Instructions that Accees

Address

Width

8 b~

8 bb MOVX @Ri,A

‘6 bns ‘ovx “@DpTR

16 bfia

List of the MCS@-51 Data

Extarnsl Data Memory Spaoe

Mnemonic

MOVX A,@’Ri

‘ovx ‘DmR’A

Operation

Read external ~

RAM @Ri

Write external

RAM @Ri

Read external

RAM @DPTR

Writa exlemal

RAM @DPTR

Execution

Time (*)

2

2

2

Note that in all external Data RAM acaases, the Ac-

cumulator is always either the destination or source of

the data.

The read and write strobes to external RAM are activated only during the execution of a MOVX instruc-

tion. Normally these signals are inactive and in fact if

they’re not going to be used at u their pins are available as extra 1/0 lines. More about that later.

Table 6. Tha MCS3’-51 Lookup

Table Read Inetmctions

I

The first MOVC instruction in Table 6 can accommodate a table of up to 256 entries, numbered Othrough

255. The number of the desired entry is loaded into the

at (A + PC) -

Accumulator, and the Data Pointer is setup to point to

beginning of the table. Then

MOVC A,@A+DPTR

copies the desired table entry into the Accumulator.

The other MOVC instruction works the same way, except the Program Counter (PC) is used as the table

base, and the table is accewed through a subroutine.

First the number of the desired entry is loaded into the

Accumulator, and the subroutine is cslled:

MOV &ENTRY_NUMBER

CALL TABLE

The subroutine “TABLE” would look like this:

TABLE: MOVC A,@A + PC

The table itself immediately follows the RET (return)

instruction in Program Memory. This type of table can

have up to 255 entries, numbered 1through 255. Number O can not be used, because at the time the MOVC

instruction is executed, the PC contains the address of

the RET instruction. An entry numbered O would be

the RET opcode itseff.

1

LOOKUP TABLES

Table 6 shows the two instructions that are available

for reading lookup tables in Program Memory. Since

these instructions access only Program Memory, the

lookup tablea can only be read, not updated. The nmemonic is MOVC for “move constant”.

If the table access is to external Program Memory, then

the read strobe is PSEN.

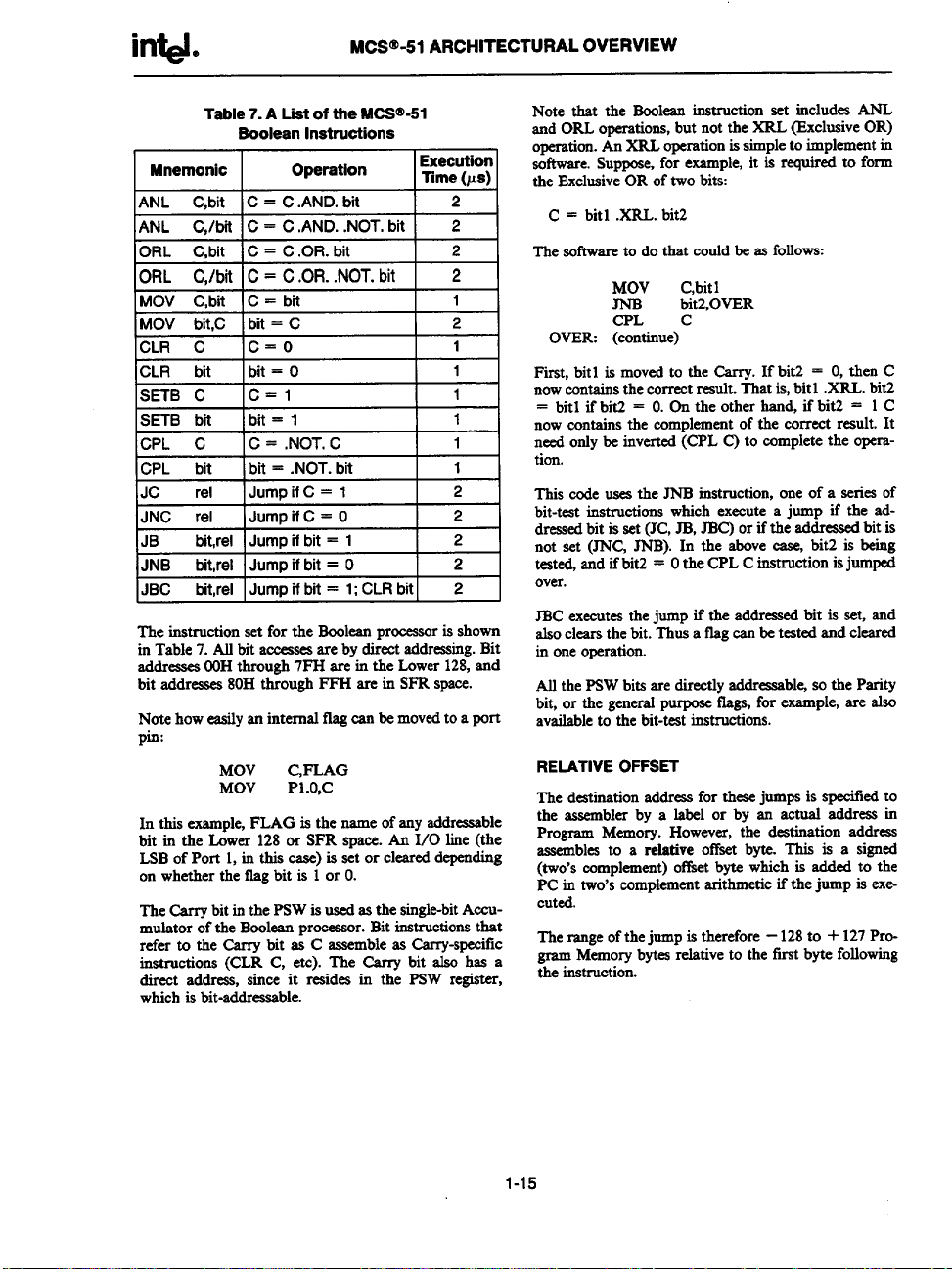

Boolean Instructions

MCS-51 devices contain a complete Boolean (single-bit)

processor. The internal RAM contains 128 addressable

bits, and the SFR space can support up to 128 other

addressable blta. Afl of the port lines are bWaddressabl% and each one csn be treated as a separate singleblt port. The instructions that access these bits are not

just conditional branches, but a complete menu of

move, aeL clear, complement, OR and AND instmctions. These kinds of bit operations are not essily obtained in other architectures with any amount of byteOriented Sottware.

1-14

Page 21

intd.

MCS@-51 ARCHITECTURAL OVERVIEW

Table

7. A List of the MCS’@-51

Boolean Instrutilons

Mnemonic

ANL C,bit IC = C .AND. bit

ANL C./bit !C = C .AND. .NOT. bit I 2

nnl

n G.

Operation

I 1

16= C.OR. bit 2

Execution

Time (us)

2

I

MO\

MO\ UIL,U

F

ICLR c

CLR bit

SETB C

SETB bn Ibit= 1 1

CPL C IC = .NOT. C

CPL bit Ibit = .NOT. bit

JC

JNC rel Jump if C = O

JB bit,rel

JNB bit,rel Jump if bit = O

JBC bit,rel IJump if bti = 1; CLR bitI 2

The instruction set for the Boolean processor is shown

in Table 7. Alt bit ameaaca are by direct addressing. Blt

addreases OOHthrough 7PH are in the Lower 128, and

bit addresses 80H through FFH are in SFR space.

Note how easily an internal ilag can be moved to a port

pin:

In this example, FLAG is the name of any addressable

bit in the Lower 128 or SFR space. An 1/0 line (the

LSB of Port 1, in this case) is set or cleared depending

on whether the flag blt is 1 or O.

The bTy

mulator of the Boolean processor. Bit instructions that

refer to the Carry bit as C assemble as Carry-specflc

instructions (CLR C, etc). The Carry bit also has a

direct addreas, since it resides in the PSW register,

which is bit-addressable.

I UIL – w

Ic=o

]bit=o

Ic=l

rel

lJumpif C= 1

Jump if bti = 1

MOV C,PLAG

MOV

P1.o,c

1= I

1

1

1

I

1

1

2

2

2

2

bitinthePsW isused as the single-bitACCU.

Note that the Boolean instruction set includes ANL

and ORL operations, but not the XRL (_ExclusiveOR)

operation. An XRL operation is simple to implement in

sof?.ware.Suppose, for example, it is Wuired @ form

the Exclusive OR of two bits

C = bitl .XRL. bit2

The sot%vare to do that could be as follows:

MOV

OVER (continue)

1

Fkst, bit1 is moved to the Carry. If bit2 = O, then C

now contains the correct reauh. That is, bit 1 .XRL. bit2

= bitl ifbiti = O.On the other hand, ifbit2 = 1 C

now contains the complement of the correct result. It

need only be inverted (CPL C) to complete the opcrstion.

This code uses the JNB instruction, one of a series of

bk-teat instructions which execute a jump if the addressed bit is set (JC, JB, JBC) or if the addressed bit is

not set (JNG JNB). In the above case, blt2 is being

tested, and if bitZ = Othe CPL C instruction is jumped

over.

JBC executes the jump if the addressed bit is set, and

also clears the bit. Thus a fig can be teated and cleared

in one operation.

All the PSW bits are directly addressable so the Parity

bit, or the general purpose flags, for example, are also

available to the bit-test instructions.

RELATIVE OFFSET

The

the assembler by a label or by an actual address in

Program Memory. However, the destination address

assembles to a relative offset byte. This is a signed

(two’s complement) oftket byte which is added to the

PC in two’s complement arithmetic if the jump is exe-

cuted.

The range of the jump is therefore -128 to + 127Pro-

gram Memory bytes relative to the first byte following

the instruction.

CPL C

destination address for these jumps is specitied to

C,bit 1

bit2,0VER

1-15

Page 22

i~.

MCS@-51 ARCHITECTURAL OVERVIEW

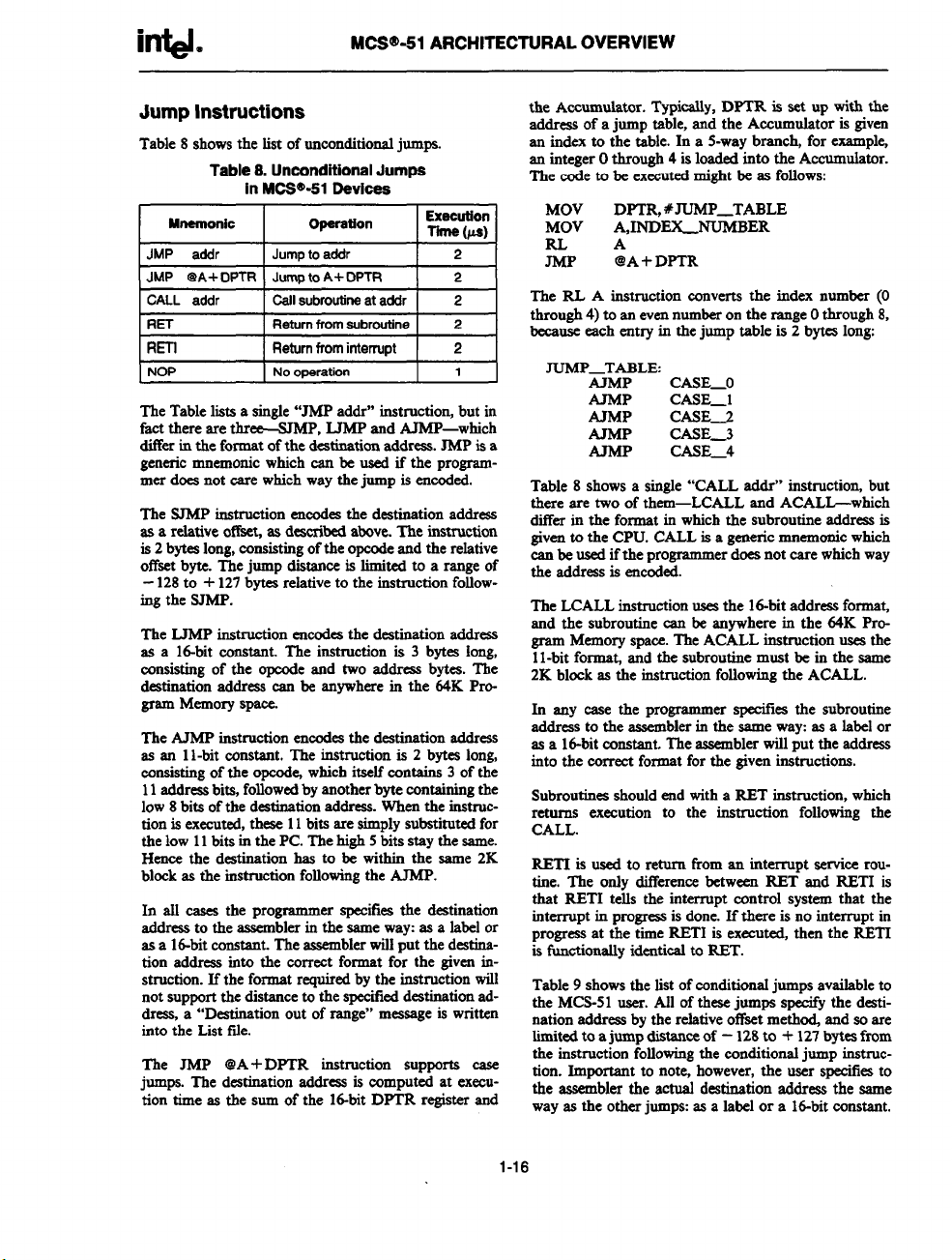

Jump lnstruMlons

Table 8 shows the list of unconditional jumps.

Table 8. Unconditional Jumps

in MCW’-51 Oavices

Mnarnonic

I

I JMP addr

JMP @A+ DPTR I Jump to A+ DPTR

CALL addr I Call subroutine at addr

1RET

IRETI

NOP

The Table lists a single “JMP addr” instruction, but in

fact there are three-SJMP, LJMP and AMP-which

differ in the format of the destination address. JMP is a

generic mnemonic which can be used if the programmer does not care which way the jump is eneoded.

The SJMP instruction eneodes the destination address

as a relative offset, as deaeribed above. The instruction

is 2 bytes long, eonsiating of the opeode and the relative

offset byte. The jump distance is limited to a range of

-128 to + 127bytes reIative to the instruction follow-

ing the SJMP.

The LJMP instruction eneodea the destination address

as a Id-bit constant. The instruction is 3 bytes long,

consisting of the opeode and two address bytes. The

destination address ean be anywhere in the 64K Program Memory

The AJMP instruction encodesthe destination address

asan 1l-bit constant. The instruction is 2 bytee long,

eonaisting of the opode, which itself contains 3 of the

11address bits, followed by another byte containing the

low 8 bits of the destination address. When the instruction is executed, these 11bits are simply substituted for

the low 11 bits in the PC. The high 5 bits stay the same.

Hence the destination has to be within the same 2K

block as the instruction following the AJMP.

In all eases the programmer specifies the de&nation

address to the assembler in the same way as a label or

as a id-bit constant. The assembler will put the destination address into the eormct format for the given instruction. If the format required by the instruction will

not support the distance to the specified destination rtddresa, a “Destination out of range”

into the Lkt fde.

The JMP @A+ DPTR instruction supports ease

jumps. The destination address is computed at exeeu-

tion time as the sum of the lti-bit DPTR register and

SPSW.

Operation

I

I Jumo to addr

I Returnfromsubroutine I z I

Returnfrominterrupt I 2 I

I

No oparation

Exeeution

Tilna (us)

121

2

I

2

1

message is written

the Accumulator. Typically, DPTR is set up with the

addms of a jump table, and the Accumulator is given

an index to the table. In a 5-way branch, for examplq

an integer Othrough 4 is loaded into the Accumulator.

The code to be executed might be ax follows

MOV

MOV

RLA

JMP

The RL A instruction converts the index

through 4) to an even number on the range Othrough 8,

because each entry in the jump table is 2 bytee long:

~P_TABLE

Table 8 shows a single “CALL addr” instruction, but

there are two of them-LCALL and ACALL-which

differ in the format in which the subroutine address is

given to the CPU. CALL is a generic mnemonic which

ean be used if the programmer does not care which way

the address is encoded.

The LCALL instruction uses the Id-bit address format,

and the subroutine ean be anywhere in the 64K Program Memory space. The ACALL instruction uses the

1l-bit format, and the subroutine most be in the same

2K bkxk as the instruction following the ACALL.

In any case the programmer specifies the subroutine

address to the assembler in the same way as a label or

as a 16-bit constant. The assembler will put the address

into the correct format for the given instructions.

Subroutines should end with a RET instruction, which

returns execution to the instruction following the

CALL.

RETI is used to return from an interrupt service rou-

tine. The only difference between RET and RETI is

that RETI tells the interrupt control system that the

interrupt in progress is done. If there is no interrupt in

progress at the time RETI is executed, then the RETI

is functionally identical to RBT.

Table 9 shows the list of conditional jumps available to

the MCS-51 user. All of these jumps specify the desti-

nation address by the relative ot%et meth~ and so are

lindted to a jump distance of – 128to + 127 bytes from

the instruction following the conditional jump instruc-

tion. Important to note, however, the user speeifies to

the assembler the actual destination address the same

way as the other jump as a label or a id-bit constant.

DPTR, #JUMP_TABLE

A,INDEX_NUMBER

@A+DPTR

MMP

AJMP

AJMP

AJMP

CASE_O

CASE_l

CASE_2

CASE_3

CASE_4

number (O

1-16

Page 23

i~.

Mnemonic

JZ rei

JNZ rel

DJNZ <byte>

CJNE A, <byte> ,rei

CJNE <byte> ,#data,rei

,rel

MCS@-51 ARCHITECTURAL OVERVIEW

Table 9. Conditions Jumps in MCS@-51 Devioes

Operation

Jump if A = O

Jumpif A+O

Deorement and jump if not zero x

Jumpif A # <byte>

Jumpif <byte> # #data

Addressing Modes

ind

Dir

Accumulator oniy

Accumulator oniy

x

x x

Rag imm

x

x

Execution

Time (ps)

2

2

2

2

2

There is no Zero bit in the PSW. The JZ and JNZ

instructions test the Accumulator data for thst ccmdition.

The DJNZ instruction (Dezrement and Jump if Not

Zero) is for loop control. To execute a loop N times,

load a counter byte with N and tersnina

a DJNZ to the beginning of the loop, as shown below

for N = 10:

LOOP: (begin loop)

The CJNE instruction (Compare and Jump if Not

Equal) can also be used for loop control as in Figure 12.

Two bytes are specified in the operand field of the instruction. The jump is executed only if the two bytes

are not equal. In the example of Figure 12, the two

bytes were the data in R1 and the constant 2AH. The

initial data in R1 was 2EH. Every time the loop was

executed, R 1 was decresnertted,and the looping was to

continue until the R1 &ta reached 2AH.

Another application of this instruction is in “great=

than, less than” comparisons. The two bytes in the op

erand field are taken as unsigned integers. If the first is

less than the second, then the Carry bit is set (l). If the

first is greater than or equal to the second, then the

Carry bit is cleared.

CPU TIMING

All

which can be used if desired as the clock source for the

CPU. To use the on-chip oscillator, connect a crystal or

ceramic resonator between the XTAL1 and XTAL2

pins of the microcontroller, and capacitors to ground as

shown in Figure 13.

MOV

(;d Imp)

DJNZ

(continue)

MCS-51 microcontrollers have an on-chip oscillator

com~#lo

●

*

COUNTER,LOOP

te the loop with

1-17

@

Mes-51

HIAOS

ORCHMOS

57.

SmLS

STAL2

STAL1

Vss

nut

Vss

STAL7.

S-TAL1

Vss

=

w’%

HMOS

ORCnuos

Mcs”-51

HMOS

ONLY

Mm%!

CHMOS

ONLY

270251-11

270251-12

270251-13

270251-14

OUART&&~WA; > Cl

RrsONAmR

‘4-J

Figure 13. Using the On-Chip Oeciilator

CLOCK STAL1

SIGNAL

-4-I

EilSRNAL

WRNAL

Figure 14. Using an Externai Ciock

=

A. HMOS or CHMOS

CLOCK

-i-l

=

B. HMOS Only

(w) STU.2

L=

u

s

C. CHMOS only

Page 24

i~.

MCS’5’-51 ARCHITECTURAL OVERVIEW

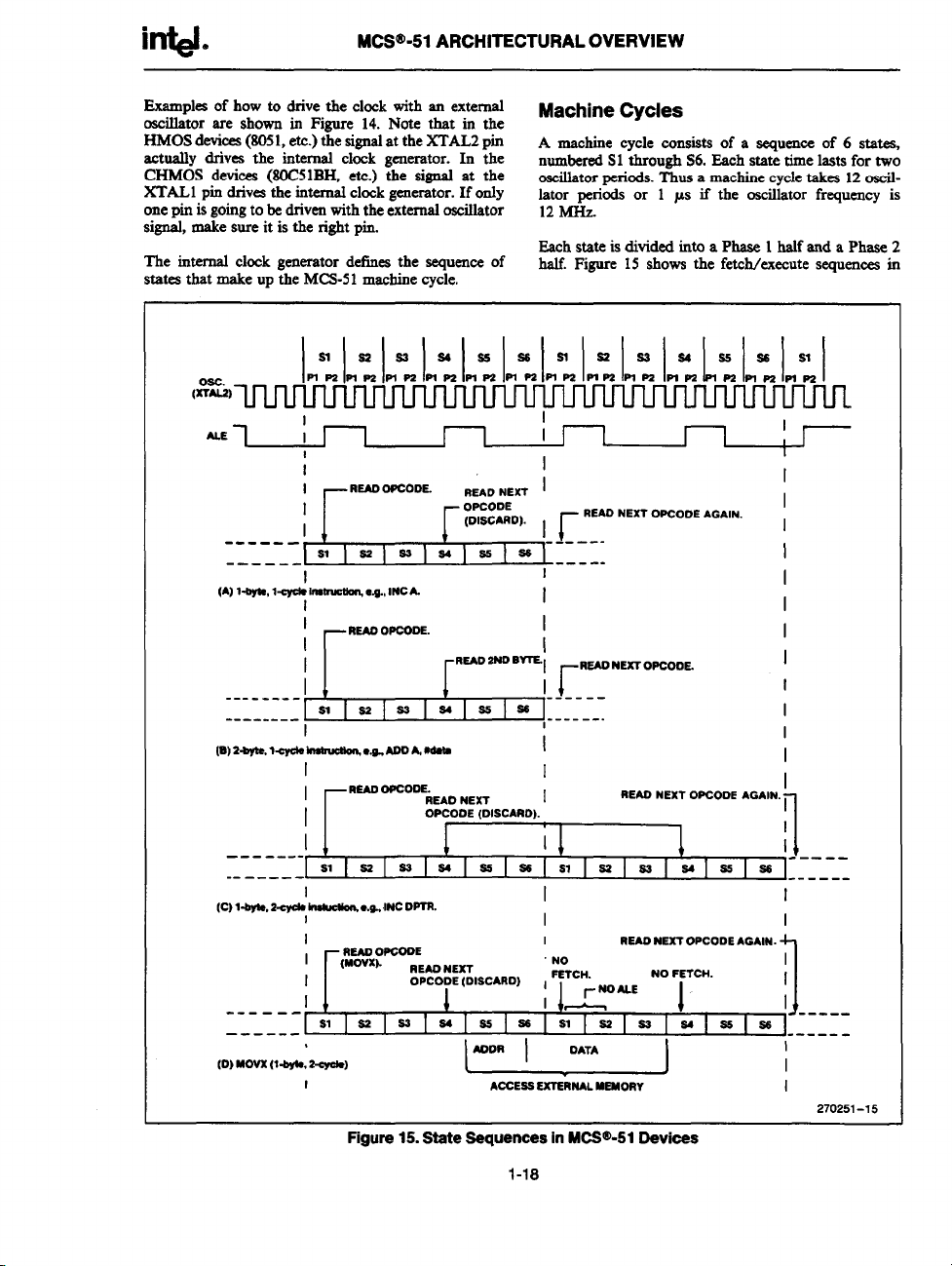

Examples of how to drive the clock with an external

oscillator are shown in Figure 14. Note that in the

HMOS devices (S051, etc.) the signal at the XTAL2 pin

actually drives the internal clock generator. In the

CHMOS devices (SOC5lBH, ete.) the signsl at the

XTAL1 pin drives the internal clock generator. If only

one pin is going to be driven with the external oscillator

signal, make sure it is the right pin.

The internal clock generator defmea the sequence of

states that make up the MCS-51 machine cycle.

51 52 as se as .% s 52 as S4.SE as 51

Plm Prps PIP2 PIPS PIPs

(%L)

ALE

!

I

I - nw OPCODE.

READ NEXT

:,,-4ir-NEmo”oOEAGA~

(A)t-byts,l-eydshs2mdh,

I

I

I

e.g., WC A.

READ OPCODE.

r I

Machine Cycles

A machine cycle consists of a sequence of 6 statea,

numbered S1through S6. Each state time lasts for two

oscillator periods. Thus a machine cycle takes 12 Oscillator periods or 1 ps if the oscillator frequency is

12 MHz.

Each state is divided into a Phase 1 half and a Phase 2

half. Figure 15 shows the fetch/execute sequences in

Pips PIPS Pips PIP2

I

I

I

mm

L

P2 PIPS

Pips

I

1

I

J

I

I

I

(B)

2-byte. 1*

I

lm@s2b. *.e.. Aoo A,mdma

I

I

-------

-------

[c)

l-byle,2qs4C imhlesm ●.s., INC DPTR.

------

----- -

[0)

MOW (l-, S-c@@

S1 as es e4ae Seslases e4aEes

I

I

— READ OPCOOE

I

(MWX).

I

I

?

sla2a2s4] as eel S11S21S2]24SSSS

I

Figure 15. Stete Sequences in MCS@’-5l Devices

i

I

OPCOOE (DISCARD).

[

READ NEXT

OPCOOE (OISCARD) , ‘1=””

AOOR

I

I

I I

I

NO

1~

I

ACCESS EXTERNAL MEMORY

1-18

READ NEXT OPCODE AGAIN. ~

RSAO NEXT OPCODE AGAIN.

~NOALE

DATA

NO FETCH.

J

I

I

I

I

1

I

I

I

1

1

, j

-----

------

I

I

I

I

-----

.-----

I

270251-15

,,;

Page 25

in~e

MCS@-51 ARCHITECTURAL OVERVIEW

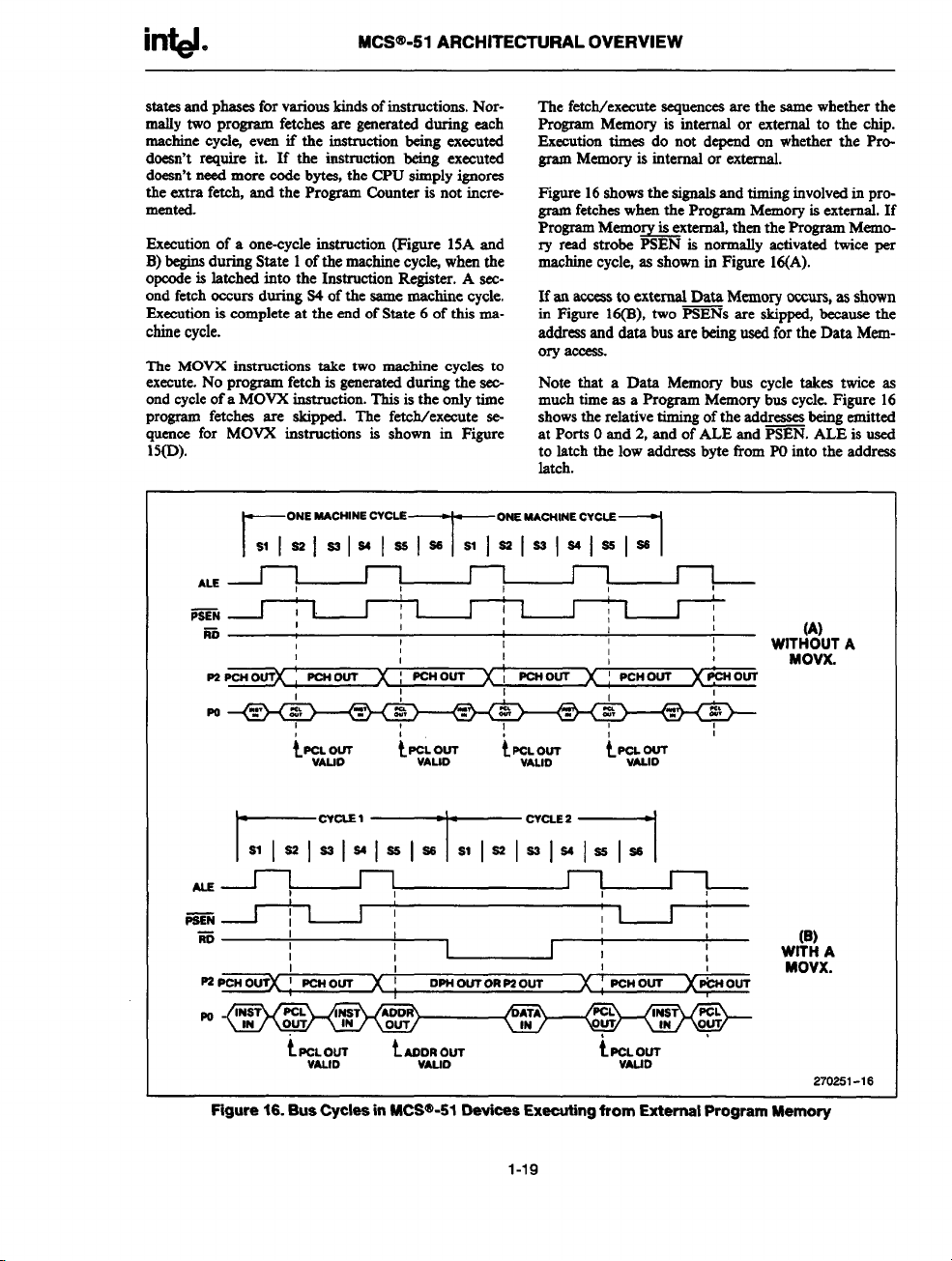

states and phases for various kinds of instructions. NormalIy two program fetches sre generated during each

machine cycle, even if the instruction being executed

doesn’t require it. If the instruction being executed

doesn’t need more code bytes, the CPU simply ignores

the extra fetch, and the Program Counter is not incremented.

Execution of a one-cycle instruction (Figure 15A and

B) beginsduring State 1of the machine cycle when the

opcode is latched into the Instruction Register. A second fetch occurs during S4 of the same machine cycle,

Execution is complete at the end of State 6 of this mschine cycle.

The MOVX instructions take two machine cycles to

execute. No program fetch is generated during the see

ond cycle of a MOVX instruction. This is the ordy time

program fetches are skipped. The fetch/execute sequence for MOVX instructions is shown in Figure

15(D).

ONE MACHINE CVCLS

ALE

-N ~

ro

P2

sl[a21s21s41aslss SIIS21S21S41SE 126

r

I

I

I

1

1

1

PCH OUTX

PCH OUT

1

I

t~::$m

T

I

1

I

L

PCH OUT

r

x’

I

I

I

1

[

x

t5i:F

The fetch/execute sequences are the same whether the

Program Memory is internal or external to the chip.

Execution times do not depend on whether the Program Memory is internal or external.

Figure 16 shows the signals and timing involved in program fetches when the Program Memory is external. If

Program Memo~xternsl, then the Program Memory read strobe PSEN is normally activated twice per

machine cycle, as shown in Figure 16(A).

If an access to external Data Memory occurs, as shown

in Figure 16(B), two PSENS are skippe$ because the

address and data bus are being used for the Data Memory access.

Note that a Data Memory bus cycle takes twice as

much time as a Program Memory bus cycle. Figure 16

shows the relative timing of the addresses being emitted

at Ports Oand 2, and of ALE and PSEN. ALE is used

to latch the low address bvte from PO into the address

latch.

ONE MACIUNE CYCLE

1

I

I

1 I

I

I

PCNOUT

I

I

ty;LL&T &T

1

1

I I

1

I

1

1

I

!

,

1

I

I

1

I

I

1

WITH%)UT A

MOVX.

G:v:m’lxm:m

)

I

-N ~

E

P2PcHc@(

Figure 16. Bus Cycles in MCS@-51 Oevices Extilng irom External Program Memory

1 1

I

I

I

! PCHOUT

t P&m&T iAC:O&UT

I I

I

I

I

I

x!

OPH OUT OR P2 OUT

1-19

I

1 I

1

I

I

PCH OUT )( PWOUT

x:

,

1

1

I

I

I

1

(B)

WITH A

MOVX.

2702!31 -16

Page 26

i~e

MCS@-51 ARCHITECTURAL OVERVIEW

When the CPU is executing from intemrd Program

Memory, ~ is not activated, and program addresses are not emitted. However, ALE continues to be activated twice per machine cycle and so is available as a

clock output signal. Note, however, that one ALE is

skipprd during the execution of the MOVX instmction.

Interrupt Structure

The

8051 core provides 5 interrupt sources 2 external

interrupts, 2 timer interrupts, and the serial pat interrupt. What follows is an overview of the interrupt

structure for the t3051.Other MCS-51 devices have ad-

ditional interrupt sources and vectors as shown in Table 1. Refer to the appropriate chapters on other devices for further information on their interrupts.

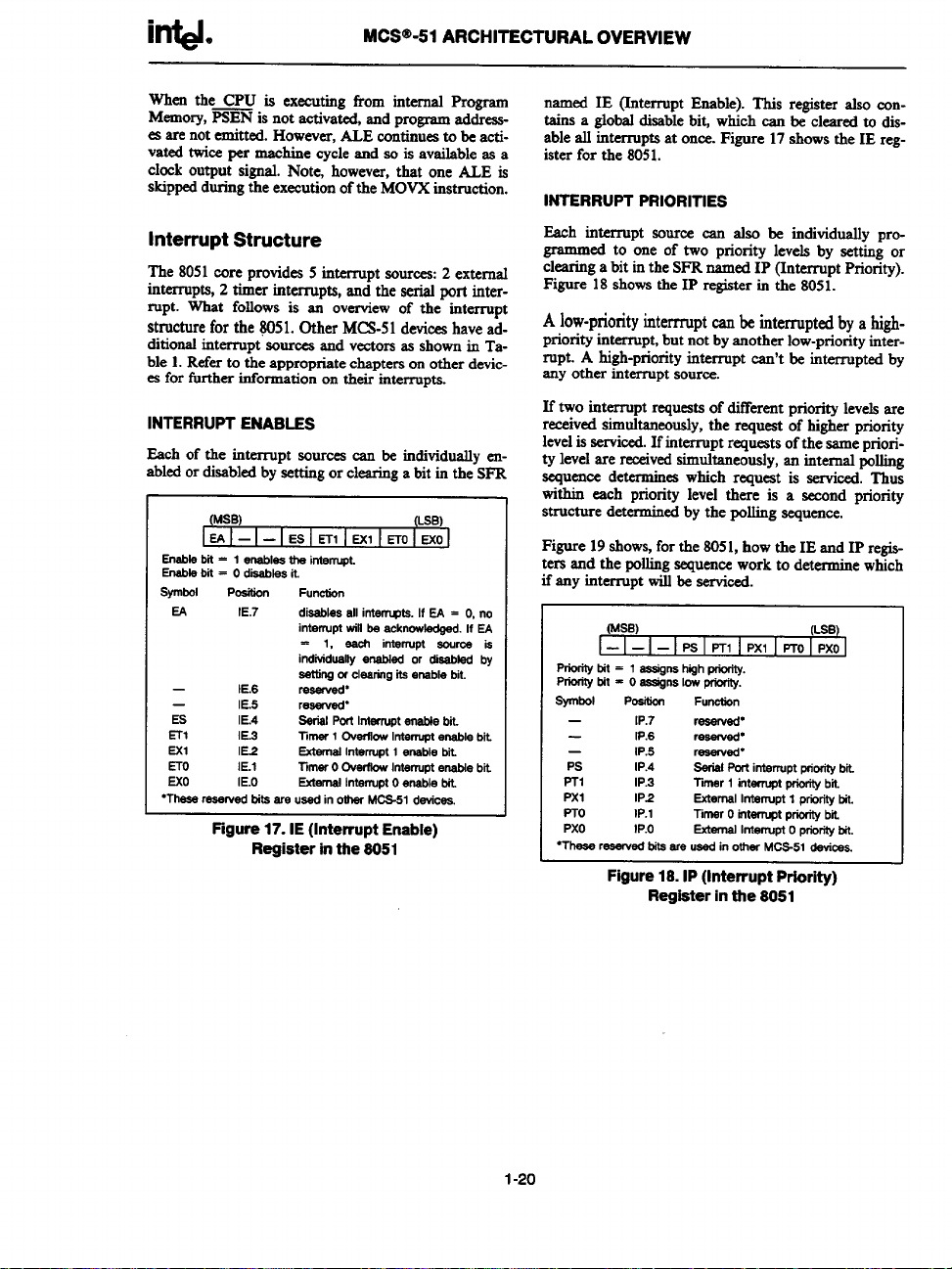

INTERRUPT ENABLES

Each of the interrupt sources can be individually enabled or disabled by setting or clearing

(MSB)

EAl —

I—IESIETI IEXIIETOIEXO

Enablebk = 1 enablesb interqf.

Ensblebk =odieabksit

symbol Pmiti9n

EA

—

—

ES

ETl IE.3

Exl

ETo IE.1 TimerOflwrffw Interruptenabfebm

Exo

“Thesereservedbiteare usedinotherMCS-51devices.

IE.7

IE.6

IE.5

IE.4

IE.2

IE.O

Figure 17. IE (Interrupt Enable)

Function

d&bles all intempts. If EA = O,no

interruptW be acknowledged.If EA

= 1, each intenupt source is

itiiuslfy enabled or disebled by

settingw clearing iteeneblebit.

reserved”

reewed”

Ser!41Pwf Intemuptenabletin.

TImw 1 OverflowInterrupteneblebit

Gtsmsl Intenupf1 enablebit

EstemslIntenuptOenablebit

Register in the 8051

a bit in the SFR

(LSB)

natned IE (Interrupt Enable). This register also contains a global disable bit, which can be cleared to disable all interrupts at once. Figure 17 shows the IE register for the 8051.

INTERRUPT PRIORITIES

Each interrupt source can also be individually pro~ed t? one of two

clearing a blt m the SFR named 1P (Interrupt Priority).

priority levels by setting or

Figure 18 shows the 1P register in the 8051.

A low-priority interrupt w be interrupted

bya high-

priority interrupt, but not by another low-priority interIUpt. A high-priority

interruptcan’tbeinterruptedby

any other interrupt source.

If two interrupt rquests of different priority levels are

received simultaneously, the request of Klgher priority

level is serviced. If interrupt requests of the same prioritylevel are received simultaneously, an interred polling

sequence determines which request is serviced. Thus

within each priority level there is a second priority

structure determined by the polling sequence.

Figure 19shows, for the 8051, how the IE and IP regieters and the polling sequence work to determine which

if any inttipt Wiilbe-serviced.

(MSB)

—

——

Prforifybit=lsssign shighpriwity.

Prioritytit = OassignslowprWity.

symbol

—

—

Ps IP.4

PTl IP.3 Timer1 intenuptpfbritybfi.

Pxl

PTo

Pxo fP.o

“Theseresewedtits are usedin otherMCB-51devices.

IPSIPTI IPXIIPTOIPXO

POeitiQn

IP.7

IP.6

IP.5 reserved-

IP2

lP.1

Functfon

resewed”

rewed”

SerialPorfinterruptp+eritybii

ExternalIntenupt1 ptirity bit.

limsr Ointerruptpriorftybii

ExternalIntellupto priorityMt.

Figure 18. 1P(Interrupt Priority)

Register in the 8051

(LSB)

1-20

Page 27

intd.

1 I

TFo

1

7FI J&o

RI

n

M~@-51 ARCHITEC~RAL OVERVIEW

IE REGISTER

+h-O+io

I

/&+.

1

-&-J.

J+

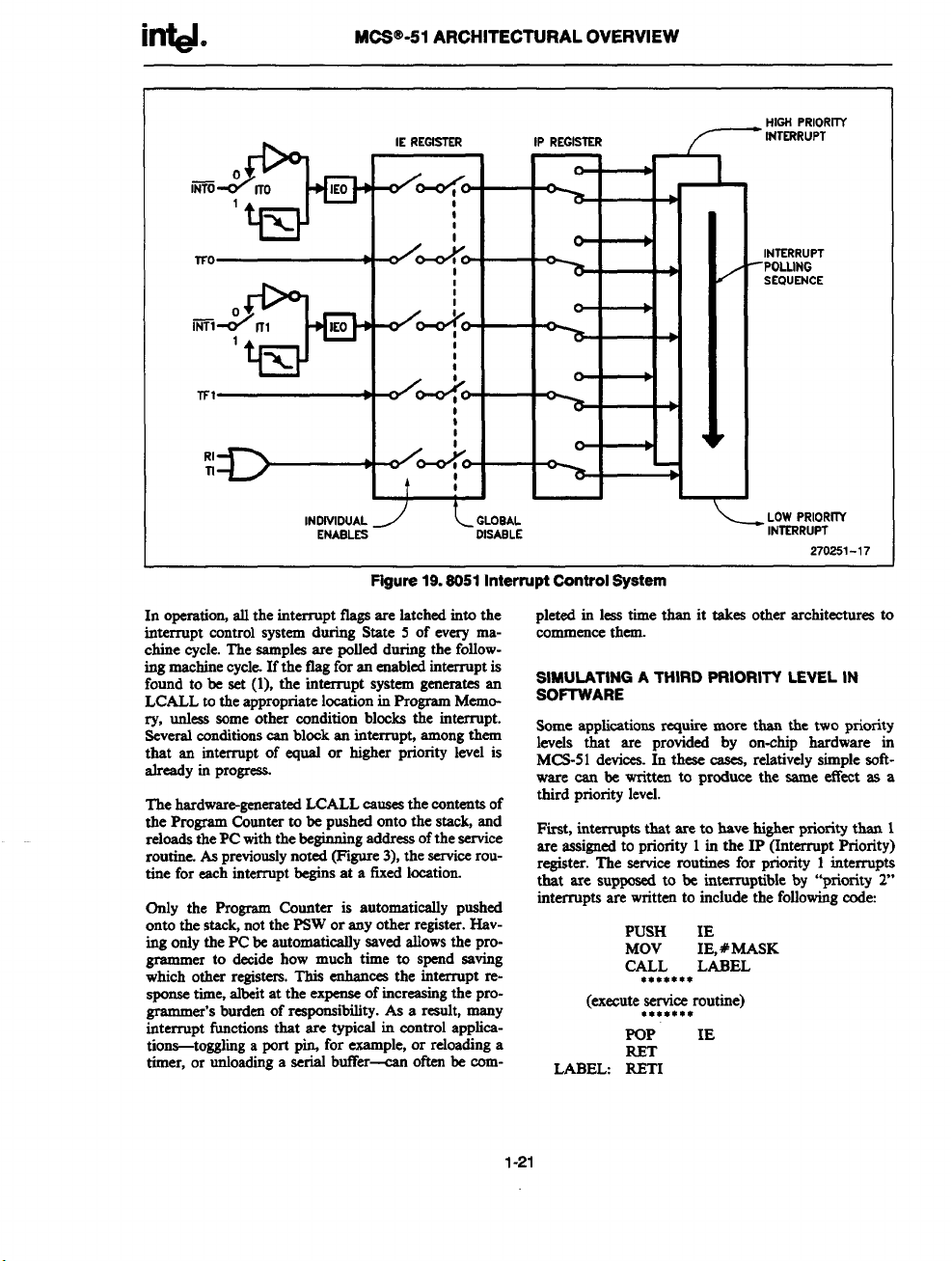

Figure 19.8051 Intermpt control system

I

:

I

I

:

I

A

.-

1PREGISTER

o

e b

o

0 b

0

b

●

➤

HIGHPRIORllY

INTERRUPT

1.

INTERRUPT

‘POLUNG

SEQUENCE

v

\

~ LyPwPNrr

270251-17

In operatiom all the interrupt tlags are latched into the

interrupt control system during State 5 of every machine cycle. The samples are polled during the following machine cycle-If the flag for an enabled interrupt is

found to be set (l), the interrupt system generates an

LCALL to the appropriate location in Program Memory, unless some other condition blocks the interrupt.

Several conditions can block an interrupt, among them

that an interrupt of equal or higher priority level is

already in progress.

The hardware-generated LCALL csusea the contents of

the Program Counter to be pushed onto the stack, and

reloads the PC with the beginning address of the service

routine. As previously noted (Rgare 3), the service routine for each interrupt begins at a fixed location.

Only the Program Counter is automatically pushed

onto the stack, not the PSW or any other register. Having only the PC be automatically saved allows the programmer to decide how much time to spend saving

which other registers. This enhances the interrupt response time, albdt at the expense of increasing the pro-

-er’s bu~en of responsibility. As a result, many

snterrupt functions that are typical in control applics-

tions-togghmg a port pim for example, or reloading a

timer, or unloading a serial but%r-can otten be mm-

pleted in lms

commence them.

SIMULATING A THIRD PRIORITV LEVEL IN

SOFIWARE

Some applications

time than it takes other architectures to

require more than the two priority

levels that are provided by on-chip hardware in

MCS-51 devices. In these cases, relatively simple software can be written to produce the same effect as a

thkd priority level.

Firat, interrupts that are to have higher priority than 1

are ssaigned to priority 1 in the 1P (Interrupt Priority)

register. The service routines for priority 1 interrupts

that are supposed to be interruptible by “priority 2“

interrupts are written to include the following code

PUSH IE

●******

●******

IE, #MASK

LABEL

MOV

CALL

(execute service routine)

POP IE

RET

LABEL RETI

1-21

Page 28

MCS@I-51 ARCHITECTURAL OVERVIEW

As soon as any priority 1 interrupt is acknowledged,

the IE (Interrupt Enable) register is m-defined so as to

disable all but “priority 2“ interrupts. Then, a CALL to

LAEEL exeoutes the RETI instruction, which clears

the priority 1 interrupt-in-program tlip-flop. At this

point SIly priority 1 interrupt that is enabled can be

seticed, but

Ody “priority’ 2“ illtCSTUptSare enabled.

POPping IE restores the original enable byte. Tberr a

normal RET (rather than another RETI) is used to

terminate the service routine. The additional software

adds 10 ps (at

12MHz) to priority 1interrupts.

ADDITIONAL REFERENCES

The following application notes are found in the Em-

bedded Chstml AppIicatwns

ber: 270648)

1. AP-69 “An Introduction

gle-Chip Microcomputer Family”

2. AP-70 “Using the Intel MCW-51 Boolean Processing Capabtities”

handbook. (Order Num-

to the Intel MCS@-5I Sin.

1-22

Page 29

MCS@51Programmer’s 2

Guide and Instruction Set

Page 30

Page 31

MCWI51 PROGRAMMER’S CONTENTS

GUIDE AND MEMORYORGANIZATION

INSTRUCTION SET PROGRAM MEMORY

DataMemory

INDIRECT ADDRESS AREA,...........,.........2-6

DIRECT AND INDIRECT ADDRESS

AREA ......................................................2-6

SPECIAL FUNCTION REGISTERS............2-8

WHAT DO THE SFRS CONTAIN JUST

AFTER POWER-ON OR A RESET,......,,2-9

...............................................2-4

PAGE

........................2-3

.................................2-3

SFR MEMORY MAP

PSW: PROGRAM STATUS WORD. BIT

ADDRESSABLE

PCON: POWER CONTROL REGISTER.

NOT BIT ADDRESSABLE .....,..,........,..2-11

INTERRUPTS

IE: INTERRUPT ENABLE REGISTER.

BIT ADDRESSABLE

ASSIGNING HIGHER PRIORITY TO

ONE OR MORE INTERRUPTS..,.........,2-13

PRIORITY WITHIN LEVEL

1P:INTERRUPT PRIORITY REGISTER.

BIT ADDRESSABLE ..,..........,.,,...........2-13

TCON: TIMEFVCOUNTERCONTROL

REGISTER. BIT ADDRESSABLE ......,.2-14

TMOD: TIMEWCOUNTER MODE

CONTROL REGISTER. NOT BIT

ADDRESSABLE

TIMER SET-UP .........................................2-1 5

TIMEFVCOUNTERO

TIMER/COUNTER 1

.................................2-lo

...................................2-1 1

............................................2-1 2

............................2-12

.......................2-13

...................................2-14

,..............,..,........,.,..2-15

..................................2-16

T2CON: TIMEWCOUNTER 2 CONTROL

REGISTER. BIT ADDRESSABLE ........2-17

TIMEWCOUNTER 2 SET-UP ...................2-18

SCON: SERIAL PORT CONTROL

REGISTER. BIT ADDRESSABLE ....,...2-19

2-1

Page 32

CONTENTS

PAGE CONTENTS

PAGE

SERIAL PORTSET-UP............................

GENERATING BAUD RATES..................2-1 9

Serial PortinModeO................................ 2-19 ‘ER’AL ‘ORT ‘N ‘ODE 2 .“.”””-””-””””.”..”;-”2-20

Serial PortinMode 1................................ 2-19 SERIAL PORT IN MODE 3 ...................O. 2-20

USING TIMER/COUNTER 1 TO

GENERATE BAUD RATES ..................2-20

2-19 USING TIMEFUCOUNTER2 TO

GENERATEBAUD RATES ..................2-20

M=&51 INSTRUCTION SET .................2-21

INSTRUCTION DEFINITIONS ................. 2-28

2-2

Page 33

i~.

MCS@-51PROGRAMMER’SGUIDE

AND INSTRUCTION SET

Theinformationpreaentedinthis chapter is collected fromthe MCW-51 ArchitecturalOverviewandtheHardware

Descriptionof the 8051,8052and 80C51chapters of this book.The material has beenselected and rearrangedto

forma quickand convenientreferencefor the programmersof the MCS-51.Thisguidepertains specificallyto the

8051,8052and 80C51.

MEMORY ORGANIZATION

PROGRAM MEMORY

The 8051hasseparateaddressspacesfor ProgramMemoryand Data Memory.The Program Memorycan be upto

64Kbyteslong.The lower4K (8K for the 8052)mayresideon-chip.

Figure 1showsa map of the 8051program memory,and Figure 2 showsa map of the 8052program memory.

m.

10M

WK

BwEe

exrmful.

FFFF

— OR

Omo

Figure1.The 8051 Program Memory

64K

evree

EXTERNAL

270249-1

2-3

Page 34

MCS@-51PROGRAMMER’SGUIDE AND INSTRUCTION SET

S4K

BWEB

270249-2

Data Memory:

The 8051can addressup to 64K bytes of Data Memoryexternal to the chip.The “MOW? instmetionis used to

accessthe externaldata memory.(Refer to the MCS-51Instmction Set, in this chapter,for detaileddeaeriptionof

instructions).

The 8051has 128bytesofon-chipRAM (256bytesin the 8052)plusa numberofSpecialFunctionRegisters(SFRS).

The lower128byteaof3Uh4 can be accessedeitherbydirectaddressing(MOVdata addr) or byindirectaddressing

(MOV@Ri).Figure3 showsthe 8051and the 8052Data Memoryorganization.

2-4

Page 35

in~e

MCS”-51 PROGRAMMER’SGUIDEAND INSTRUCTION SET

“F

9—————I

DIRECT&

INomECT

Aoon~

Figure 3a. The 8051 Data Memory

OFFF

64K

Bwea

270249-3

w’

m

n=

00.

m’rEmAL

IWIRECT

ADORESSINGONLY

6

ema

OmE(n

om.Y

Olmcl&

INOIRECT

AwnEaslNG

emToFFn

Figure 3b. The 8052 Date Memory

FFFl

64K

m-me

ExnmNAL

I

270249-4

2-5

Page 36

i~.

MCS@-51PROGRAMMER’S GUIDEAND INSTRUCTION SET

INDIRECT ADDRESS AREA:

Notethat in Figure 3bthe SFRSand the indirect address RAMhave the sameaddreasea(80H-OFFH).Nevertheless,they are two separateareas and are

For examplethe instruction

MOV 8oH,#o&lH

writesOAAHto Port Owhichis one of the SFRSand the instruction

amesaedin two diiferentways.

MOV

MOV

writesOBBHin location 80Hofthe data RAM. Thus, after executionofboth of the aboveinstructionsPort Owill

containOAAHand location80of the MM will containOBBH.

Notethat the stack operationsare examplesofindirectaddressing,sothe upper 128bytesofdata MM are available

as stack spacein those deviceswhichimplement256bytesofinternal RAM.

Rr),#80H

@RO,#OBBH

DIRECT AND INDIRECT ADDRESS AREA:

The 128bytesof W whichcanbe ameased

as listedbelowand shownin Figure4.

1. RegistarBanks O-3:

bank O.To use the other register banks the user must select them in the software(refer to the MCS-51Micro

AssemblerUser’sGuide).Each registerbank contains 8 one-byteregisters,Othrough7.

Resetinitiahzesthe StackPointertolocation07H and it is incrementedonceto start from location08H whichisthe

first register(RO) of the secondregister bank. Thus, in order to usemore than oneregisterbank, the SPshouldbe

intiaked to a different locationof the RAM where it is not usedfor data storage(ie,higher part ofthe WNW).

2. Bit AddressableArex 16byteshavebeen assignedfor this segment,20H-2FH.Each one of the 128bits of this

wgmmt can be directlyaddressed(0-7FH).

Thebits can be referred

address ie. Oto 7FH.The otherwayis with referenceto bytes20Hto 2FH. Thus,bits O-7 can alsobereferredto

as bits 20.0-20.7, and bits 8-FHare the same as 21.0-21.7 and so on.

Eachof the 16bytesin this segmentcan also be addressedas a byte.

LocationsOthrough lFH (32 bytes).ASM-51and the deviceafter reset defaultto register

to in twowaysboth of whichare acaptable by the ASM-51.Onewayis to refer to their

byboth directand indirectaddressingcanbedividedinto 3 segments

3. ScratchPad Arex Bytes30Hthrough7FH are availableto the user as &ta MM. However,ifthe stack pointex

has beeninitializedto this arm enoughnumberof bytesshouldbe left asideto prevent5P data destruction.

2-6

Page 37

in~.

Figure4 showsthe difYerentsegmentsof the on-chipRAM.

MCS@-51PROGRAMMER’SGUIDE AND INSTRUCTION SET

sol

4SI

301

2s

20

18

10

0s

00

0...

3

2

1 OF

0

Figure4.128 Bytes of RAM Direct and Indirect Addreeesble

. . . 7F

SCRATCH

14P

1.7

I3F

2P

AaaRLLs

SSGMENT

27

IF

RSGISIER

1?

07

Pm

ARSA

BANKS

270249-5

2-7

Page 38

in~.

MCS@-51PROGRAMMER’SGUIDE AND INSTRIJCTlON SET

SPECIAL FUNCTION REGISTERS:

Table 1 containsa list of all the SFRsend their addressee.

ComparingTable 1and Figure 5showsthat all of the SFRs that are byteand bit addressableare locatedonthe first

col~n of-thediagramin Figure 5.

Table 1

Symbol

*ACC

*B

“Psw

SP

DPTR

DPL

DPH

*PO

*P1

●P2

*P3

*IP

*IE

TMOD

“TCON

*+ T2CON

THO

TLO

TH1

TL1

+TH2

+TL2

+RCAP2H

+RCAP2L

●SCON

SBUF

PCON

= Bitaddreaaable

+ = 8052

only

Name

Accumulator

B Register

ProgramStatusWord

StackPointer

Data Pointer2 Bytes

LowByte

HighByte

Porto

Port1

Port2

Port3

InterruptPriorityControl

InterruptEnableControl

Timer/Counter Mode Control

Timer/CounterControl

Timer/Counter2 Control

Timer/CounterOHighByte

Timer/CounterOLowByte

Timer/Counter 1 HighByte

Timer/Counter 1 LowByte

Timer/Counter2 HighByte

Timer/Counter2 LowByte

T/C 2 CaptureReg. HighByte

T/C 2 CaptureReg. LowByte

SerialControl

SerialData Buffer

PowerControl

Address

OEOH

OFOH

ODOH

81H

82H

83H

80H

90H

OAOH

OBOH

OB8H

OA8H

89H

88H

OC8H

8CH

8AH

8DH

8BH

OCDH

OCCH

OCBH

OCAH

98H

99H

87H

2-8

Page 39

int&

M~@.51 PROGRAMMERS GUIDE AND INSTRUCTIONSET

WHAT DO THE

SFRS CONTAIN JUST A~ER POWER-ON OR A RESET?

Table2 lists the contents of each SFR after power-onor a hardware reset.

Register

“ACC

“B

*PSW

SP

DPTR

*PO

*P1

*P2

*P3

*IP

*IE

TMOD

●TCON

● +T2CON

THO

TLO

TH1

TL1

+TH2

+TL2

+RCAP2H

+RCAP2L

●SCON

SBUF

PCON

= Undefined

= BitAddreassble

+ = 8052only

Table 2. Conte

DPH

DPL

) of the SFRS after reset

Value in Binary

00000000

00000000

00000000

00000111

00000000

00000000

11111111

11111111

11111111

11111111

8051 XXXOOOOO,

8052 XXOOOOOO

8051 OXXOOOOO,

8052 OXOOOOOO

00000000

00000000

00000000

00000000

00000000

00000000

00000000

00000000

00000000

00000000

00000000

00000000

Indeterminate

HMOS OXXXXXXX

CHMOS OXXXOOOO

2-9

Page 40

intd.

SFR

MEMORY MAP

F8

FO

E8

EO

D8

DO

T2CON

C8

co

B8

BO

A8

AO

98

90

88

80

M(3%51 PROGRAMMERS GUIDE AND INSTRUCTION SET

8 Bytes

B

ACC

Psw

RCAP2L RCAP2H TL2 TH2

1P

P3

IE

P2

SCON SBUF

PI

TCON TMOD TLO TL1 THO

Po SP DPL

-r

Bit

Addressable

DPH

Figure 5

TH1

PCON

FF

F7

EF

E7

DF

D7

CF

C7

BF

B7

AF

A7

9F

97

8F

87

2-1o

Page 41

i~. M=@-51 PROGRAMMER’SGUIDE AND INSTRUCTION SET

ThoseSFRsthat havetheirbitsassignedforvariousfunctionsarelistedin thissection.Abriefdescriptionofeachbit

is providedfor quickreference.For moredetailedinformationrefer to the ArchitectureChapterof this book.

PSW: PROGRAM STATUS WORD. BIT ADDRESSABLE.

CY

CY

AC

FO

Rsl

Rso

Ov

—

P

AC FO RS1

PSW.7

PSW.6

PSW.5 Flag Oavailableto the user for generalpurpose.

PSW.4

PSW.3 RegisterBank selectorbit O (SEE NOTE 1).

PSW.2

Psw.1

Psw.o Parity flag.Set/clearedby herdwareeach instructioncycleto indicateerrodd/werrnumberof

Flag.

Carry

AuxiliaryCarry Flag,

RegisterBankselectorbit 1(SEENOTE 1).

OverflowFlag.

Userdefinableflag.

RSO Ov I — I P

‘1’bitain the accumulator.

NOTE:

1.ThevaluepresentedbyRSOandRS1selectsthecorrespondingregisterbank.

RS1

o

o 1 1 08H-OFH

1

1 1

RSO Register Bank Address

0 0 OOH-07H

0

2 10H-17H

3

18H-l FH

PCON: POWER CONTROL REGISTER. NOT BIT ADDRESSABLE.

SMOD I — I — I — GF1

SMOD Doublebaud rate bit. If Timer 1 is used to generatebaudrate end SMOD = 1, the baud rate is doubled

whenthe SeriatPort is used in modes 1, 2, or 3.

—

Not implemented,reservedfor future w.*

—

Not implemented,reservedfor future w.*

—

Not implemented,r

Generalpurposeflagbit.

GF1

eservedforfuture use.”

GFO General purposeflagbit.

Power Down bit. Setting this bit activates Power Downoperation in the 80C51BH.(Availableonly in

PD

CHMOS).

Idle Modebit. %.ttittgthisbit activatesIdle Modeoperationin the 80C51BH.(Availableonlyin CHMOS).

IDL

GFO PD IDL

If 1sarewrittento PDandIDLat thesametimejPD tske$precedence,

●Usersoftwareshouldnotwrite1sto reservedbita.Thaeebitsmaybeusedin futureMCS-51 productsto invokenew

featurea.Inthatcase,theresetorinactivevalueofthenewbitwillbeO,anditsectivevaluewillbe1.

2-11

Page 42

irltele

McS@-51PROGRAMMER’SGUIDE AND INSTRUCTION SET

INTERRUPTS:

In order to use any of the interruptsin the MCS-51,the followingthree stepsmust be taken.

1. 3et the EA (enableall) bit in the IE register to 1.