Page 1

3B SCIENTIFIC® PHYSICS

Satz 4 Kalorimeterzylinder U30070

Bedienungsanleitung

11/08 ALF

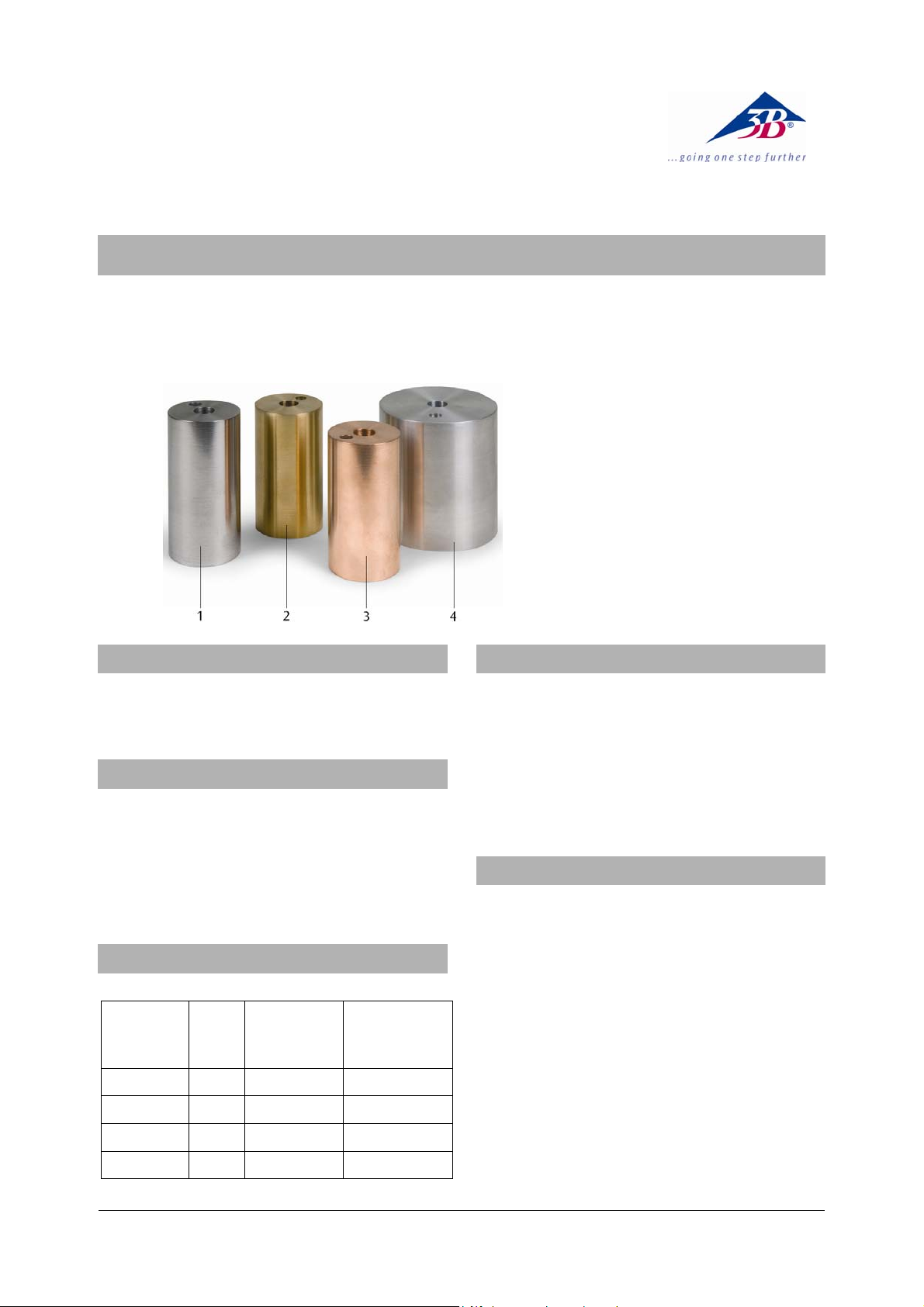

1 Kalorimeter, Stahl

2 Kalorimeter, Messing

3 Kalorimeter, Kupfer

4 Kalorimeter, Aluminium

1. Sicherheitshinweise

Verbrennungsgefahr durch Heizelement oder

Kalorimeter.

• Apparatur vor dem Abbau abkühlen lassen.

2. Beschreibung

Der Satz 4 Kalorimeterzylinder dient zur Bestimmung

der spezifischen Wärmekapazitäten von Aluminium,

Messing, Kupfer und Stahl.

Die Kalorimeterzylinder sind mit zwei Bohrungen

versehen, um einen Heizstab (12,5 mm Durchmesser)

sowie ein Thermometer oder eine Temperatursonde (8

mm Durchmesser) aufzunehmen.

3. Technische Daten

Masse Zylinder: ca. 1 kg (Genauigkeit ±2 %)

Material

Aluminium 84 75 896

Messing 84 44 377

Kupfer 85 43 385

Stahl 92 44 452

Höhe

(mm)

Durchmesser

(mm)

Spezifische

Wärme

J/(kg*K)

4. Zusätzlich erforderliche Geräte

1 DC-Netzgerät 0 - 20 V, 0 - 5 A (230 V, 50/60 Hz)

U33020-230

oder

1 DC-Netzgerät 0 - 20 V, 0 - 5 A (115 V, 50/60 Hz)

U33020-115

1 Heizelement, 12 V U30075

1 Thermometer, -20°C bis +110°C U40911

1 Mechanische Stoppuhr, 30 min U40800

5. Bedienung

• Kalorimeterzylinder wiegen und die Masse

notieren.

• Kalorimeterzylinder auf eine hitzefeste Unterlage

stellen und ihn mit isolationsmaterial umgeben,

so dass der Wärmeverlust so klein wie möglich ist.

• Heizelement und Thermometer in die

entsprechenden Bohrungen einsetzen. Zuvor

einige Tropfen Öl oder Wasser in die

Thermometerbohrung geben, um einen guten

thermischen Kontakt zwischen Thermometer und

Kalorimeter herzustellen.

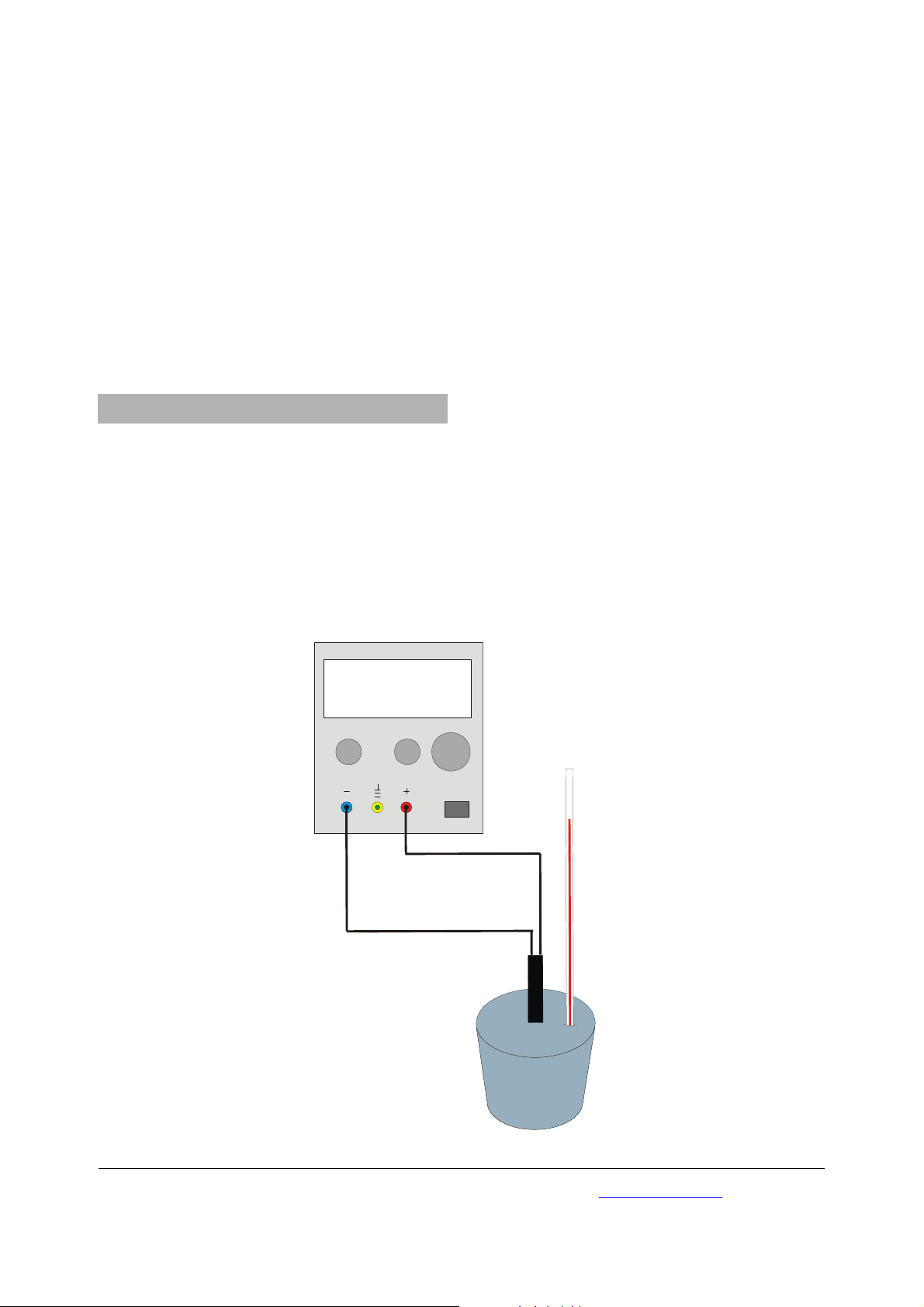

• Schaltung gemäß Fig. 1 herstellen.

• Netzgerät einschalten und einen Strom von ca. 4 A

einstellen. Danach Netzgerät wieder ausschalten.

1

Page 2

• Vor Start des Messlaufs einige Minuten warten.

Dann die Anfangstemperatur des

Kalorimeterzylinders ablesen.

• Netzgerät einschalten und gleichzeitig die

Zeitmessung starten.

• Abwarten bis die Temperatur um ca. 20° C

gestiegen ist. Zeit und Endtemperatur notieren.

Die spezifische Wärmekapazität ist gegeben durch die

Gleichung:

mit I: Strom, U: Spannung, t: Zeit, m: Masse des

Kalorimeterzylinders c: spezifische Wärmekapazität,

θ

: Anfangstemperatur, θ2: Endtemperatur

1

6.1 Hinweise zur Fehlerminimierung

Angenommen, dass die Strom- und Spannungsanzeigen hinreichend genau sind, liegen die zwei

Hauptfehlerquellen des Experiments beim Ablesen der

Temperatur und im Wärmeverlust.

Der Wärmeverlust ist davon abhängig, wie hoch die

Endtemperatur über der Raumtemperatur liegt. Er

lässt sich dadurch minimieren, dass der

Temperaturanstieg möglichst klein gehalten wird.

()

θ−θ⋅⋅=⋅⋅ cmtUI

12

6. Allgemeine Hinweise

U33020

Wenn die Ablesegenauigkeit des Thermometers 1° C

beträgt, dann ergibt sich ein relativ großer Fehler von

10% bei einem Temperaturanstieg um 10° C.

Deshalb gilt es einen Ausgleich zu finden zwischen

dem Fehler, der durch Wärmeverlust bei einem

großen Temperaturanstieg verursacht wird, und dem

relativ großen Fehler beim Ablesen der Temperatur

bei einer geringen Temperaturerhöhung.

Eine Erhöhung der Temperatur um 20° C ergibt eine

Fehlerquote von 5% (bei einer Ablesegenauigkeit des

Thermometers von 1° C) und einen relativ geringen

Fehler durch Wärmeverlust.

6.2 Vermeidung von Wärmeverlust nach Rumford

Nach Rumford kann der Wärmeverlust durch

folgenden Prozess vermieden werden. Wird der

Kalorimeterzylinder vor dem Experiment für einige

Stunden in einem Kühlschrank aufbewahrt, so liegt

seine Anfangstemperatur um θ unter Raumtemperatur. Wenn dann seine Endtemperatur um θ über

Raumtemperatur liegt, dann ist die aufgenommene

Wärmemenge, solange seine Temperatur unter

Raumtemperatur ist, gleich der Wärmemenge, die er

abgibt, wenn seine Temperatur über Raumtemperatur

ist. Es findet dann kein Wärmeverlust statt.

0 0 0 4

.

0...5 A 0...20 V

2 0 1

.

VA

Fig. 1 Experimenteller Aufbau

3B Scientific GmbH • Rudorffweg 8 • 21031 Hamburg • Deutschland • www.3bscientific.com

Technische Änderungen vorbehalten

© Copyright 2008 3B Scientific GmbH

Page 3

3B SCIENTIFIC® PHYSICS

Set of 4 Metal Block Calorimeters U30070

Instruction Sheet

11/08 ALF

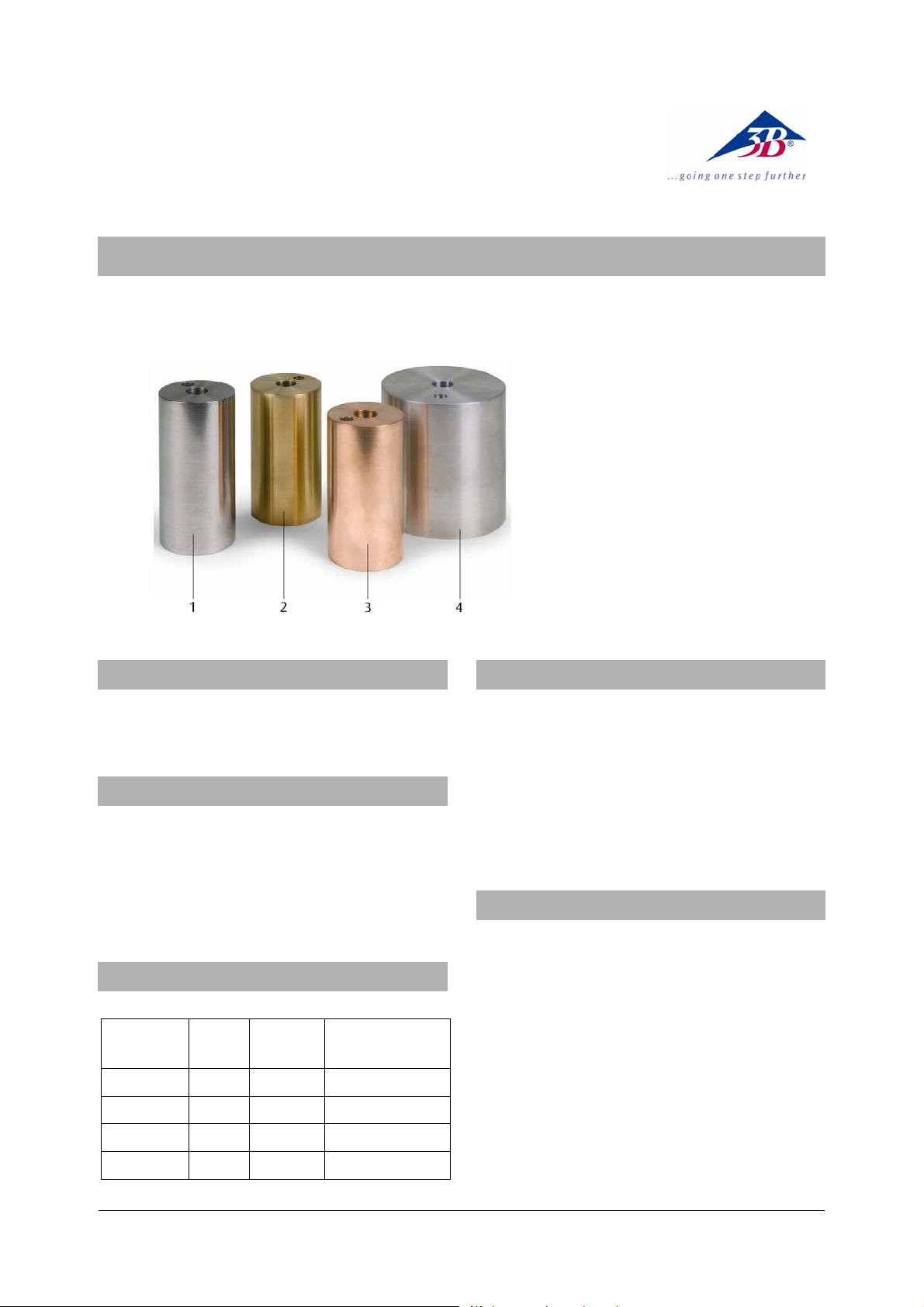

1 Steel calorimeter

2 Brass calorimeter

3 Copper calorimeter

4 Aluminium calorimeter

1. Safety instructions

There is a risk of burns from heater or calorimeter.

• Allow apparatus to cool before moving it.

2. Description

The set of 4 metal block calorimeters is used to

determine the specific heat capacity of aluminium,

brass, copper and steel.

The metal blocks are drilled with two holes to

accommodate an immersion heater (12.5 mm dia.)

and a thermometer or temperature probe (8 mm dia.).

3. Technical data

Mass of block: approx. 1 kg (±2% accuracy)

Material

Aluminium 84 75 896

Brass 84 44 377

Copper 85 43 385

Steel 92 44 452

Height

(mm)

Diameter

(mm)

Specific heat

J/(kg*K)

4. Additionally required equipment

1 DC Power Supply 0 - 20 V, 0 - 5 A (230 V, 50/60 Hz)

U33020-230

or

1 DC Power Supply 0 - 20 V, 0 - 5 A (115 V, 50/60 Hz)

U33020-115

1 Immersion Heater, 12 V U30075

1 Thermometer -20°C to +110°C U40911

1 Mechanical stopwatch, 30 min U40800

5. Operation

• Weigh the calorimeter block and record its mass.

• Place the calorimeter block on a heat proof mat

surrounded by insulation, so that the heat losses

are kept to the minimum.

• Insert the immersion heater and the thermometer

into the appropriate hole. Drop some oil or water

into the thermometer hole to ensure good

thermal contact between the thermometer and

the block.

• Set up the circuitry according fig. 1.

• Switch on the power supply and adjust it to give a

current of about 4 A. Switch the heater off.

1

Page 4

• Before starting the experimental run, wait for a

few minutes before taking the temperature of the

calorimeter block.

• Switch on the heater and start the clock.

• Wait until the temperature has risen about 20

o

C

and record the time and final temperature.

The specific heat capacity can then be calculated from

the equation:

()

θ−θ⋅⋅=⋅⋅ cmtUI

12

with I: current, U: voltage, t: time, m: mass of calorimeter block, c: specific heat capacity, θ

temperature, θ

: final temperature

2

: initial

1

6. General notes

6.1 Explanation of how to minimise the error

Assuming that the readings for the current and voltage

are reasonable accurate, the two main sources of error

in the experiment will be the readings of the

temperature change and the effects of any heat loss.

Obviously the heat loss will depend on the excess

temperature above the room temperature, so this can

be minimised by keeping the temperature rise as

small as possible.

U33020

If the thermometer can only be read accurately to 1

then a temperature rise of 10

o

would give a 10% error,

o

,

which is really too large for this type of experiment.

Therefore, it is a balance between the error

introduced by a large temperature increase causing

heat losses, and a small temperature increase giving a

large percentage error in the temperature readings. A

o

20

rise in temperature will give a 5% error in reading

the thermometer (assuming it can only be read

accurately to 1

o

) and a reasonable low error due to

heat loss.

6.2 Rumford’s correction

Rumford argued that heat losses could be eliminated

by the following process. If the metal block is kept in a

fridge for several hours before the experiment, then it

will start at, say, θ below room temperature. If its final

temperature after the experiment was θ above room

temperature, then the heat it took in while below

room temperature would be equal to the heat it gave

out while above room temperature, so there would be

no heat loss.

0 0 0 4

.

0...5 A 0...20 V

2 0 1

.

VA

3B Scientific GmbH • Rudorffweg 8 • 21031 Hamburg • Germany • www.3bscientific.com

Fig. 1 Experimental set up

Subject to technical amendment

© Copyright 2008 3B Scientific GmbH

Page 5

3B SCIENTIFIC® PHYSICS

Blocs calorimétriques en métal, jeu de 4 U30070

Manuel d'utilisation

11/08 ALF

1 Bloc calorimétrique, acier

2 Bloc calorimétrique, laiton

3 Bloc calorimétrique, cuivre

4 Bloc calorimétrique, aluminium

1. Consignes de sécurité

Risques de brûlures provenant de l'élément de

chauffage ou du calorimètre !

• Laissez toujours refroidir l'appareillage avant de

le démonter.

2. Description

Ces blocs calorimétriques en métal de forme

cylindrique servent à déterminer la capacité

thermique spécifique de l'aluminium, du laiton, du

cuivre et de l'acier.

Les blocs en métal présentent deux alésages

permettant d'y rattacher un thermoplongeur

(diamètre de 12,5 mm) et un thermomètre ou une

sonde de température (8 mm Ø).

3. Caractéristiques techniques

Masse de chaque bloc: env. 1 kg (précision de ±2%)

Matériau

Aluminium 84 75 896

Laiton 84 44 377

Cuivre 85 43 385

Acier 92 44 452

Hauteur

(mm)

Diamètre

(mm)

Chaleur

spécifique

J/(kg*K)

4 Accessoires supplémentaires requis

1 Alimentation CC 0 - 20 V, 0 - 5 A (230 V, 50/60 Hz)

U33020-230

ou

1 Alimentation CC 0 - 20 V, 0 - 5 A (115 V, 50/60 Hz)

U33020-115

1 Thermoplongeur, 12 V U30075

1 Thermomètre, -20°C - +110°C U40911

1 Chronomètre mécanique, 30 min U40800

5. Commande

• Pesez le bloc calorimétrique de forme cylindrique

et notez-en la masse.

• Posez le bloc calorimétrique de forme cylindrique

sur une surface résistant à la chaleur et

enveloppez-le d'un matériel isolant afin de

minimiser au maximum la déperdition de

chaleur.

• Insérez l'élément de chauffage et le thermomètre

dans les alésages correspondants. Mettez

auparavant quelques gouttes d'huile ou d'eau

dans l'alésage destiné au thermomètre afin

d'assurer un bon contact thermique entre le

thermomètre et le calorimètre.

• Formez le circuit conformément à la figure 1.

• Allumez le bloc d'alimentation et réglez un

courant d'environ 4 ampères. Éteignez ensuite de

nouveau le bloc d'alimentation.

1

Page 6

• Attendez quelques minutes avant de démarrer le

cycle de mesures. Relevez ensuite la température

initiale du bloc calorimétrique de forme

cylindrique.

• Allumez le bloc d'alimentation tout en démarrant

simultanément la mesure du temps.

• Attendez que la température soit montée à

environ 20° C. Notez le temps ainsi que la

température finale.

L'équation suivante permet d'obtenir la capacité

thermique spécifique :

I : étant le courant, U : étant la tension, t : étant le

temps, m : étant la masse du bloc calorimétrique de

forme cylindrique, c : étant la capacité thermique

spécifique, θ

étant la température finale

6.1 Conseils utiles permettant de minimiser les

erreurs

Si nous partons de l'hypothèse que les affichages de

courant et de tension sont suffisamment précis, dans

cet essai expérimental, les deux sources principales

d'erreurs sont d'une part liées à la lecture de la

température et d'autre part à la déperdition de

chaleur.

La déperdition de chaleur dépend de combien la

température finale dépasse la température ambiante.

Il est possible de minimiser cette déperdition en

réduisant autant que possible la montée en

température.

()

θ−θ⋅⋅=⋅⋅ cmtUI

12

: étant la température initiale et θ2 :

1

6. Remarques générales

U33020

Si la précision de lecture du thermomètre est de 1° C,

l'erreur relativement élevée prend alors une valeur de

10 % pour une montée en température de 10° C.

Il s'agit donc de trouver une compensation entre

d'une part l'erreur liée à la déperdition de chaleur

provenant d'une montée en température élevée et

d'autre part l'erreur relativement élevée se produisant

lors de la lecture de la température pour une

augmentation faible de température.

Une augmentation de la température de 20° C se

traduit par un taux d'erreur de 5 % (pour une

précision de lecture du thermomètre de 1° C) et un

taux d'erreur relativement faible lié à la déperdition

de chaleur.

6.2 Prévention d'une déperdition de chaleur selon

Rumford

Selon Rumford, il est possible d'éviter une déperdition

de chaleur en appliquant la procédure suivante. Si le

bloc calorimétrique de forme cylindrique est conservé

quelques heures au réfrigérateur avant l'essai

expérimental, sa température initiale est alors

inférieure de θ à la température ambiante. Lorsque

sa température finale dépasse la température

ambiante de θ, et tant que sa température est

supérieure à la température ambiante, la quantité de

chaleur absorbée est alors égale à la quantité de

valeur dégagée par le bloc calorimétrique lorsque sa

température est supérieure à la température

ambiante. Il ne se manifeste alors aucune déperdition

de chaleur.

0 0 0 4

.

0...5 A 0...20 V

3B Scientific GmbH • Rudorffweg 8 • 21031 Hamburg • Allemagne • www.3bscientific.com

Fig. 1 : Appareillage expérimental

Sous réserve de modifications techniques

© Copyright 2008 3B Scientific GmbH

2 0 1

.

VA

Page 7

3B SCIENTIFIC® PHYSICS

Blocchi calorimetrici di metallo, set di 4 U30070

Istruzioni per l'uso

11/08 ALF

1 Corpo calorimetro, acciaio

2 Corpo calorimetro, ottone

3 Corpo calorimetro, rame

4 Corpo calorimetro, alluminio

1. Norme di sicurezza

Pericolo di ustioni dovute all'elemento termico o al

barometro.

• Lasciare raffreddare l’apparecchio prima di

smontarlo.

2. Descrizione

Blocchi calorimetrici cilindrici in metallo, per la

determinazione della capacità termica specifica di

alluminio, ottone, rame e acciaio.

I blocchi di metallo presentano due fori in cui

posizionare un riscaldatore a immersione (12,5 mm Ø) e

un termometro o una sonda di temperatura (8 mm Ø).

3. Dati tecnici

Massa dei blocchi: ca. 1 kg (±2% precisione)

Materiale

Alluminio 84 75 896

Ottone 84 44 377

Rame 85 43 385

Acciaio 92 44 452

Altezza

(mm)

Diametro

(mm)

Calore specifico

J/(kg*K)

4. Altri apparecchi necessari

1 Alimentazione CC 0 - 20 V, 0 - 5 A (230 V, 50/60 Hz)

U33020-230

oppure

1 Alimentazione CC 0 - 20 V, 0 - 5 A (115 V, 50/60 Hz)

U33020-115

1 Riscaldatore a immersione, 12 V U30075

1 Termometro da -20°C a +110°C U40911

1 Cronometro meccanico, 30 min U40800

5. Utilizzo

• Pesare i cilindri calorimetrici e annotarne la

massa

• Collocare il cilindro calorimetrico su una base

resistente al calore e circondarlo con materiale

isolante in modo che la dispersione termica sia la

minore possibile.

• Inserire l'elemento termico e il termometro nei

fori corrispondenti. Versare prima alcune gocce

d'olio o di acqua nel foro del termometro, per

creare un buon contatto termico tra termometro e

calorimetro.

• Realizzare il collegamento come illustrato in Fig. 1.

• Attivare l'alimentatore e impostare una corrente

di ca. 4 A. Quindi spegnere di nuovo

l'alimentatore.

1

Page 8

• Attendere alcuni minuti prima di avviare

l'esecuzione della misura. Leggere quindi la

temperatura iniziale del cilindro calorimetrico.

• Accendere l'alimentatore e contemporaneamente

avviare la misurazione del tempo.

• Attendere fino a che la temperatura non è salita

fino a circa 20°C. Annotare tempo e temperatura

finale.

La capacità termica specifica è data dall'equazione:

con I: corrente, U: tensione, t: tempo, m: massa del

cilindro calorimetrico c: capacità termica specifica, θ

temperatura iniziale, θ

6.1 Indicazioni per la minimizzazione degli errori

Assunto che le indicazioni della corrente e della

temperatura siano sufficientemente esatte, le due

fonti principali di errore dell'esperimento stanno

nella lettura della temperatura e nella dispersione

termica.

La dispersione termica dipende da quanto la

temperatura finale è superiore alla temperatura

ambiente. Essa può essere minimizzata grazie al fatto

che l'incremento di temperatura viene mantenuto il

più basso possibile.

()

θ−θ⋅⋅=⋅⋅ cmtUI

12

: temperatura finale

2

6. Indicazioni generali

U33020

:

1

Se la precisione di lettura del termometro è pari a 1°

C, risulta n errore relativamente grande del 10% in

caso di un incremento di temperatura di 10° C.

Pertanto si tratta di trovare un compromesso tra

l'errore dovuto alla dispersione termica, in caso di un

elevato incremento di temperatura, e l'errore

relativamente grande nella lettura della temperatura

in caso di un aumento della temperatura ridotto.

Un aumento della temperatura di 20° C dà come

risultato una percentuale di errore del 5% (con una

precisione di lettura del termometro di 1° C) e un

errore relativamente ridotto a causa della dispersione

termica.

6.2 Evitare la dispersione termica in base a Rumford

Secondo Rumford la dispersione termica può essere

evitata mediante il seguente processo. Se il cilindro

calorimetrico prima dell'esperimento viene

conservato per alcune ore in un frigorifero, la sua

temperatura iniziale rispetto alla temperatura

ambiente è θ volte inferiore.

Se in seguito allo svolgimento dell’esperimento la

temperatura del calorimetro è θ superiore alla

temperatura ambiente, la quantità di calore assorbita

è pari alla quantità di calore che esso cede,

fintantoché la sua temperatura non cala al di sotto

della temperatura ambiente. Non avviene quindi

nessuna dispersione termica.

0 0 0 4

.

0...5 A 0...20 V

2 0 1

.

VA

Fig. 1 Struttura sperimentale

3B Scientific GmbH • Rudorffweg 8 • 21031 Amburgo • Germania • www.3bscientific.com

Con riserva di modifiche tecniche

© Copyright 2008 3B Scientific GmbH

Page 9

3B SCIENTIFIC® PHYSICS

Calorímetros de bloque de metal, juego de 4 U30070

Instrucciones de uso

11/08 ALF

1 Bloque calorimétrico, acero

2 Bloque calorimétrico, latón

3 Bloque calorimétrico, cobre

4 Bloque calorimétrico, aluminio

1. Advertencias de seguridad

Peligro de quemaduras por elemento calentador o por

el calorímetro.

• Deje enfriar el aparato antes de desmontarlo.

2. Instrucciones de uso

Bloques cilíndricos calorímetros, de metal, para la

determinación del calor específico del aluminio, del

latón, del cobre y del acero.

En los bloques de metal se han practicado dos

perforaciones para el alojamiento de un calentador

sumergible (12,5 mm de diámetro), y un termómetro o

una punta de sonda de temperatura (diámetro de 8 mm).

3. Datos técnicos

Peso de bloque: aprox. 1 kg (±2% de exactitud)

Material

Aluminio 84 75 896

Latón 84 44 377

Cobre 85 43 385

Acero 92 44 452

Altura

(mm)

Diámetro

(mm)

Calor específico

J/(kg*K)

4. Aparatos requerdos adicionalmente

1 Fuente de alimentación de c.c. 0 - 20 V, 0 - 5 A (230 V, 50/60 Hz)

U33020-230

o

1 Fuente de alimentación de c.c. 0 - 20 V, 0 - 5 A (115 V, 50/60 Hz)

U33020-115

1 Calentador sumergible, 12 V U30075

1 Termómetro de,-20°C a +110°C U40911

1 Cronómetro mecánico, 30 min U40800

5. Manejo

• Se pesa el calorímetro y se anota su masa.

• Se coloca el cilindro calorimétrico sobre una

superficie resistente al calor y se envuelve con

material aislante al calor para que la pérdida de

calor sea mínima.

• Se insertan el elemento calentador y el

termómetro en sus correspondientes orificios.

Antes se vierten unas gotas de aceite o de agua en

el orificio del termómetro, para lograr un buen

contacto entre el termómetro y el calorímetro.

• Se realiza el circuito según la Fig. 1.

• Se conecta la fuente de alimentación y se ajusta

una corriente de 4 A. Se desconecta nuevamente

la fuente de alimentación.

1

Page 10

• Antes del inicio de la serie de mediciones se

esperan unos minutos. Luego se lee y anota la

temperatura inicial del cilindro calorimétrico.

• Se conecta la fuente de alimentación y al mismo

tiempo se inicia la medición del tiempo.

• Se espera a que la temperatura haya aumentado

en unos 20° C. Se anotan el tiempo y la

temperatura final.

La capacidad calorífica específica se obtiene de la

ecuación:

con I: Corriente, U: Tensión, t: Tiempo, m: Masa del

cilindro calorimétrico c: Capacidad calorífica

específica, θ

final

6.1 Indicaciones para minimizar los errores

Suponiendo que las indicaciones para la corriente y la

tensión son lo suficientemente exactas, las principales

fuentes de errores en el experimento se encuentran

en la lectura de la temperatura y en la pérdida de

calor.

La perdida de calor depende de que tan alta sea la

temperatura final con respecto a la temperatura

ambiente. Ésta se puede minimizar haciendo que el

aumento de la temperatura sea lo más mínimo

posible.

()

θ−θ⋅⋅=⋅⋅ cmtUI

12

: Temperatura inicial, θ2: Temperatura

1

6. Indicaciones generales

U33020

Cuando la exactitud de lectura del termómetro es de

1° C , entonces se tiene un error grande del 10%

cuando se tiene un aumento de temperatura de 10° C.

Se trata por lo tanto de encontrar una compensación

entre el error que se origina por la pérdida de calor

durante un aumento de temperatura grande y el error

grande en la lectura con aumento de temperatura

bajo.

Un aumento de temperatura en 20° C da una

proporción de error del 5% (con una exactitud de

medida del termómetro de 1° C) y un error

relativamente bajo por pérdida de calor.

6.2 Prevención de pérdida de calor según Rumford

Según Rumford es posible prevenir la pérdida de calor

con el siguiente proceso. Si antes de iniciar el

experimento el cilindro calorimétrico se coloca por

varias horas en un refrigerador, su temperatura inicial

estará ahora en θ por debajo de la temperatura

ambiente. Entonces cuando su temperatura final se

encuentre en θ por encima de la temperatura

ambiente, la cantidad de calor absorbida mientras la

temperatura está por debajo de la del ambiente es

igual a la cantidad de calor entregada cuando su

temperatura final está en el mismo θ por encima de la

temperatura del ambiente. No tiene lugar una

pérdida de calor.

0 0 0 4

.

0...5 A 0...20 V

Fig. 1 Montaje de experimentación

2 0 1

.

VA

3B Scientific GmbH • Rudorffweg 8 • 21031 Hamburgo • Alemania • www.3bscientific.com

Se reservan las modificaciones técnicas

© Copyright 2008 3B Scientific GmbH

Page 11

3B SCIENTIFIC® PHYSICS

Calorímetro de bloco de metal, jogo de 4 U30070

Manual de instruções

11/08 ALF

1 Bloco calorímetro, aço

2 Bloco calorímetro, latão

3 Bloco calorímetro,

4 Bloco calorímetro, alumínio

cobre

1. Indicações de segurança

Perigo de queimaduras pelo elemento de

aquecimento ou calorímetro.

• Deixar esfriar o aparelho antes da desmontagem.

2. Descrição

Blocos cilíndricos calorímetros de metal para a

determinação da capacidade de calor específico do

alumínio, do bronze, do cobre e do aço.

Os blocos de metal são perfurados com dois furos para

acomodar um aquecedor de imersão (12,5 mm de

diâmetro) e um termômetro ou sensor de temperatura

(8 mm Ø).

3. Dados técnicos

Massa do bloco: aprox. 1 kg (± % de precisão)

Material

Alumínio 84 75 896

Latão 84 44 377

Cobre 85 43 385

Aço 92 44 452

Altura

(mm)

Diâmetro

(mm)

Calor específico

J/(kg*K)

4. Aparelhos adicionalmente exigidos

1 Fonte de alimentação DC 0 - 20 V, 0 - 5 A (230 V, 50/60 Hz)

U33020-230

ou

1 Fonte de alimentação DC 0 - 20 V, 0 - 5 A (115 V, 50/60 Hz)

U33020-115

1 Aquecedor de imersão, 12 V U30075

1 Termômetro, -20°C a +110°C U40911

1 Cronômetro mecânico, 30 min U40800

5. Operação

• Pesar o calorímetro de cilindro e anotar a massa.

• Colocar o calorímetro de cilindro sobre uma base

resistente ao calor e envolve-lo com material

isolante para que a perda de calor seja a menor

possível.

• Inserir o elemento aquecedor e o termômetro nas

suas respectivas furações. Antes colocar algumas

gotas de óleo ou água na furação do termômetro,

para estabelecer um bom contacto térmico entre

o termômetro e o calorímetro.

• Estabelecer a ligação segundo Fig. 1.

• Ligar a fonte de alimentação e colocar uma

corrente de aprox. 4 A. Depois desligar a fonte de

alimentação de novo.

1

Page 12

• Esperar alguns minutos antes de começar o curso

das medições. Depois ler a temperatura de inicio

do calorímetro de cilindro.

• Ligar a fonte de alimentação e ao mesmo tempo

começar a medição de tempo.

• Esperar até a temperatura aumentar em aprox.

20° C. Anotar o tempo e a temperatura final.

A capacidade de calor específica é dada por meio da

equação:

com I: Corrente, U: Tensão, t: Tempo, m: Massa do

calorímetro de cilindro c: Capacidade de calor

específica, θ

final

6.1 Indicações para a minimização de erros

Supondo que as marcações de corrente e tensão sejam

suficientemente exatas, as duas fontes de erro

encontram-se na leitura da temperatura e na perda de

calor.

A perda de calor é dependente de quanto alta à

temperatura final se encontre acima da temperatura

do ambiente. Ela pode ser minimizada, em que, no

possível, o aumento de temperatura seja mantido

pequeno.

()

θ−θ⋅⋅=⋅⋅ cmtUI

12

: Temperatura inicial, θ2: Temperatura

1

6. Indicações gerais

U33020

Quando a precisão de leitura do termômetro é de 1°

C, então resulta um erro relativamente grande de 10%

num aumento de temperatura em 10° C.

Por isso vale encontrar um equilíbrio entre o erro, que

é causado pela perda de calor num aumento de

temperatura muito acentuado, e do erro

relativamente grande na leitura de um aumento de

temperatura baixo.

Um aumento de temperatura em 20° C resulta numa

quota de erro de 5% (numa precisão de leitura do

termômetro de 1° C) e um erro relativamente

pequeno por perda de calor.

6.2 Evitação da perda de calor segundo Rumford

Segundo Rumford a perda de calor pode ser evitada

pelo seguinte processo. Se o calorímetro de cilindro

for guardado por algumas horas num refrigerador

antes da experiência, então a sua temperatura inicial

encontra-se por θ abaixo da temperatura de

ambiente. Se a seguir a sua temperatura final está em

θ acima da temperatura de ambiente, então a

quantidade de calor recebida, enquanto a sua

temperatura está abaixo da temperatura de ambiente,

é igual à quantidade de temperatura que ele cede,

quando a sua temperatura está acima da temperatura

de ambiente. Então não dará lugar a nenhuma perda

de calor.

0 0 0 4

.

0...5 A 0...20 V

2 0 1

.

VA

Fig. 1 Montagem experimental

3B Scientific GmbH ▪ Rudorffweg 8 ▪ 21031 Hamburgo ▪ Alemanha ▪ www.3bscientific.com

Sob reserva de alterações técnicas

© Copyright 2008 3B Scientific GmbH

Loading...

Loading...