Page 1

Page 2

3

THE ART OF TANK WARFARE

A Guide to World War II Armored Combat for Players of Panzer Elite

By Christopher S. Keeling

Contents

1. The History of Tank Warfare ----------------------------------5

World War I

Between the Wars

World War II

2. Tank Academy ----------------------------------13

Tank Basics

Firepower

Protection

Mobility

Other factors

3. Tanks in Battle ----------------------------------21

Tanks in the Offensive

Tanks in the Defensive

Tank against Tank

Tank against Infantry

Antitank Warfare

4. The Campaigns ----------------------------------34

North Africa

Italy

Normandy

5. The Wehrmacht ----------------------------------38

German Tactics

German Artillery

German Unit Options

German Armaments

German Units

6. The U.S. Army ----------------------------------85

American Tactics

American Artillery

American Unit Options

American Armaments

American Units

7. Glossary and Abbreviations ----------------------------------118

Page 3

4

HOW TO USE THIS BOOK

This book is designed as both a historical reference for the armored warfare enthusiasts among us, and as a

primer for the novice. The history and development of the tank, covered in the first chapter, is provided in

order to give some background on the state of armored vehicle technology in World War II. The second

chapter gives much more specific information on the “current” technologies and how they were used in

combat. Chapter three covers the tactics associated with armored fighting vehicles in different roles and

against different types of targets. Chapter four is a supplement to the overall historical guide, detailing the

historical campaigns included with the game (for in-depth data on the specific scenarios, see the Gameplay

Manual, chapter seven). Reference data for all of the units in Panzer Elite is provided in chapters five and

six. Finally, a glossary of armored vehicle terminology and abbreviations is given in chapter seven. Before you

begin play, we recommend that you should at least read chapters two and three.

Page 4

1. THE HISTORY OF TANK WARFARE

5

Armored fighting vehicles are a relatively recent development of military capability. Superceding the horse

cavalry shortly after the First World War, new theories on armored warfare slowly displaced the age-old

concepts of infantry and cavalry driven offensive battle by the eve of the Second World War. The history of

armored warfare, like any other technological advancements designed for the military, have suffered at the

hands of politicians, languished on the books of economists and been compromised by the higher echelons of

command. Fortunately, for the armor theorists, their ideas were eventually proven sound and the tank took

its place as a major battlefield component, forging the way for maneuver warfare and the further

development of combined arms theory.

Page 5

6

WORLD WAR I

Although the tank first came into use during the First World War, the basic principles of armored warfare

had been used for hundreds, even thousands, of years. The notion of a heavily armed and armored mobile

force which could strike deep into enemy territory was first embodied by the heavy cavalry and chariot units

of ancient times, as well as by the infantry tactic known as the “tortoise” which was used to assault fortified

installations. However the need for a self-propelled armored vehicle was recognized much earlier in history.

The Spanish used horse-towed sleds with small cannons mounted on them to provide close artillery support

for their troops in the field. The famous inventor and artist Leonardo de Vinci recognized the need for a

heavily armored and mobile engine of war and drew up plans accordingly. In World War I, the need became

apparent for a vehicle that could resist the machinegun, a weapon that had completely dominated the fleshand-blood battlefield of man and horse. At first, the use of simple armored cars was common, however, it

was soon obvious that these vehicles, based on the limited suspensions of the current automobile and truck,

were impractical on a battlefield which was covered with bomb craters, trenches, and barbed wire. A new

solution was needed and, thanks to the invention of the caterpillar track, the tank was born.

The First Tanks. The British were the first to recognize the need for an armored vehicle capable of

traversing the battlefield. Their first design, ordered by Winston Churchill (then First Lord of the

Admiralty), called the No. 1 Lincoln machine, was built in 1915 and subsequently modified through the

addition of superior tracks to become the ‘Little Willie’. This vehicle could easily cross a five-foot (1.52 m)

trench and climb up a four-and-a-half foot (1.37 m) obstacle. For performance and armament, it had a top

speed of 3.5 MPH (5.6 km/h), light armor, and fittings for a 40mm gun in a small turret. This early design

was superceded by Big Willie, a now-familiar design utilizing the rhomboidal-shaped chassis and tread system

with guns mounted on the hull sides instead of in a turret. The frontal armor was only 10mm thick, with a

crew of eight men, a top speed of 4 MPH (6.4 km/h), two 57mm guns in hull sponsons, and four pivoting

machineguns. This basic vehicle was tested in early 1916 and ordered into production in two versions; the

“male” version, mounting the twin 57mm guns, and the “female” version which replaced the two cannons

with two more machineguns. Although used mainly for local testing, the British armies first major use of

tanks in combat took place on November 20, 1917, at the Battle of Cambrai, where the British used 400

tanks to penetrate almost ten kilometers into German lines.

The German Army had their own tank in development, the A7V, which had a maximum of 30mm of

armor, a 57mm gun in the hull front, six machineguns, and a crew of 18 men. The A7V was unwieldy, with

generally poor performance, and a requirement for an enormous crew of 18 men. As a result, less than 35

were actually produced. The French, also seeing the need for such a vehicle early in the war, had produced

several heavy tank designs and one exceptional light tank design, the Renault FT-17. This tank, along with

the British Mk.VI, a late-war version of the Big Willie, was adopted by the US Expeditionary Forces, which

did not come up with an indigenous design until after the war ended in 1918. The FT-17 was the first

“modern-style” tank design, mounted with a 37mm gun in a small, one-man turret, with the hull suspended

between low tracks, and the engine situated in a rear compartment. The crew consisted of a muchoverworked commander/gunner/loader and a driver. Italy had also produced an improved version of this

vehicle known as the Fiat Tipo 3000 Modello 1921, which did not enter service until after the war.

Page 6

7

The First Tankers. Nearly every major nation had its own outspoken supporter of the tank during this

critical period of armor development. Colonel Ernest Swinton was the most outspoken advocate of armored

warfare in Great Britain, and was heavily supported by future Prime Minister Winston Churchill, as well as

Major J. F. C. Fuller, who later invented and refined many of the early tactics and techniques of armored

warfare. It was largely due to Swinton’s efforts that the British tank design program was initiated in 1915.

General Elles, the commander of the successful British armored attack at Cambrai, was also one of the early

pioneers. Lieutenant Colonel George S. Patton, Jr., who was later to become famous as commander of the

Third Armored Division in World War II, was also an early supporter, and one of the first American tank

officers to fight in September, 1918. The first American armored warfare school, located in Pennsylvania,

was established by another officer whose experiences would heavily influence the outcome of WWII: Captain

Dwight D. Eisenhower. Among the French, it was Colonel Jean Baptiste Estienne who managed to convince

his commander, General Joffre, of the need for armored fighting vehicles. It was he who envisioned the first

successful light tank, the Renault FT-17, and obtained the authority to have them designed and built. It was

not until after the war had ended and the effectiveness of the tank in action tested, that Germany and the

Soviet Union, the two major proponents and innovators in armored warfare in World War II, took

an interest.

BETWEEN THE WARS

The results of the First World War proved the initial usefulness of the concept of armored warfare, however,

the war was over before the technical and tactical aspects of armored warfare could be completely worked

out. In the years immediately following the war, the world fooled itself into believing that The Great War

had also been The War to End all Wars, and like most immediate responses to peace after a prolonged

conflict, most countries drastically cut all military recruiting, research and production. The horse cavalry

once again moved to the fore, and the advancement of the airplane and antitank rifle, also used in combat for

the first time during World War I, were seen as doom for the tank. Never the less, every army contained diehard advocates of armored vehicles, and they continued preparing for the next war, even amid the taunts and

ridicule of their compatriots in the more “traditional” military branches.

The Enlightenment. J. F. C. “Boney” Fuller was one of the first British armor theorists to advocate the

concept of combined-arms warfare; a melding of tactics utilizing armored units, infantry, artillery, and

aircraft (although he later modified his concepts to include only different types of tanks). Apparently, only

the German and Soviet armies paid attention to the ideas of this British officer! While J. Walter Christie, an

American engineer, had designed a more advanced suspension system for armored vehicles, he was unable to

convince the US government of the usefulness of a more reliable armored vehicle. The Soviet Union,

however, took his research to heart and went on to produce one of the best tanks of the Second World War;

the T34. Adna R. Chaffee was the prime promoter of mechanization in the United States, and eventually

went on to command the first American mechanized cavalry brigade. In France, Charles de Gaulle, later to

become famous as the leader of the Free French in World War II, advocated the need for armored fighting

vehicles in the French army. He was so successful in his advocacy, that when Germany did attack France

early in the Second World War, France actually maintained an armored force, both more numerous and of

higher quality, than that of Germanys. Unfortunately, these units were ineffectively utilized in the field,

being commanded by “Old Heads”, who had not thought much beyond the tactics of the man, the horse

and the artillery tube. Heinz Guderian was the German visionary who successfully organized, with Hitler’s

support, the concepts of the German Panzer Division and Corps. His grasp of armor tactics, first espoused

Page 7

8

by Fuller, but further expanded to combine all units of the Wehrmacht, including the Luftwaffe, was made

clear long before the first Panzer crossed the border into Poland in 1939. Many of these units were secretly

trained in the Soviet Union, where Misha Tukhachevski and Kliment Voroshilov had built up the Soviet

armored force during the 1920s and ‘30s. The Soviets and Germans learned a great deal from each other

during this period, with the Germans specializing in tactics and vehicle quality, while the Soviets

concentrated on vehicle simplicity and mobility. These lessons, learned and applied by Guderian during the

buildup and training of the German Panzer Corps, culminated in one of Hitler’s most effective military tools,

the Blitzkrieg, or ‘Lightning War’. Guderian’s book, Achtung! Panzer!, which was published in 1937, outlined

this armored warfare concept, and should have been proof enough and a warning to the world that

Germany’s military might was sleeping restlessly.

Tank Designs. Due to the short-sighted expectations of a lasting peace by many nations’ governments and

people’s desire for an end to the bloodshed, armored forces were generally not supported after the First World

War. Advancements made during this time in armored vehicle development were made at a much slower

“peacetime” pace, leading to some unusual (and mostly useless) vehicles that, luckily, didn’t reach much

further than the prototype stages of development. Britain, for example, fielded a large number of one and

two-man tankettes. These small, open-topped vehicles were armed with light infantry weapons, usually only

a machinegun. Thinly armored, but highly mobile, these vehicles were adopted as an economizing measure

by many countries that could not afford real tanks. Vickers Arms also developed a light tank, and with the

manufacturing license for the design being sold around the world, formed for many nations the foundation

of their experimentation with domestic tank production. In the US, this design was the basis for the T1

tank, in Poland, for the 7TP, and in the Soviet Union for the T26. These tanks were usually armed only with

machineguns or light (37mm-40mm) cannon, and had frontal armor ranging from 15mm to 40mm thick.

The majority of these early armored forces were divided into light, fast vehicles used for reconnaissance and

penetration, taking on the traditional role of the cavalry, and the slower tanks with heavier armor designed to

closely support the infantry during their attacks. These vehicles often had 50mm-80mm of frontal armor,

and were also armed with machineguns and a light cannon although these were occasionally replaced by a

mortar or light howitzer for more mobile indirect support. The final tank concept that evolved between the

wars, was that of the heavy “breakthrough” tank. Although this circuitous development cycle culminated in

such sound designs as the German Tiger tank and the Soviet KV-1, the process of development also included

the construction of what have become known as “land battleships” by several nations. These slow, heavy

tanks were designed to engage massed enemy formations and fortifications, pushing forward against any

resistance to allow the deployment of the infantry and light tanks in their wake. These vehicles were huge,

often larger than some of the First World War behemoths, and mounted several machineguns and multiple

cannon, often in several turrets or half-turrets surrounding an elevated central turret. The Soviets were

especially fond of this type of vehicle, and produced several models (the T-28, T-35, T-100, and SMK), some

of which were actually used in the Second World War until replaced by the superior and more operationally

effective KV series.

Page 8

9

WORLD WAR II

Armored warfare, as a professional branch of military service and a tool for battlefield dominance in modern

times, culminated within the crucible of the Second World War. No conflict, before or since, has seen such

extensive development and use of the tank in combat, either in numbers, time, or variants. This

developmental explosion had such a profound influence on later concepts of armored vehicle design and their

tactical application, that land combat would never be the same again. From the earliest Blitzkrieg into

Poland until the final assault on Berlin, no other conflict has seen such a rapid evolution of what was and still

is, considered by many to be the decisive arm of battle. An infantryman will usually go into great detail

concerning their indispensable role in holding a piece of real estate, once it’s been won. What they often

forget to mention is that the armored vehicle is what got them there in the first place.

A short overview of the war in Europe is provided in the following synopsis.

Blitzkrieg. Prior to 1939 and the Invasion of Poland, the early German victories of WWII had been

predominantly bloodless. This included the annexation of the Sudetenland, the occupation of

Czechoslovakia and Austria, and the expulsion of occupation forces from the Ruhr. Although Britain and

France had been wary of German expansion, they did not declare war on Germany until she invaded Poland

on September 1, 1939. By offering half of Poland, as well as the Baltic states of Latvia, Lithuania, and

Estonia to the Soviet Union, Germany managed to secure a measure of security to the east. This agreement,

based on the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, was the culmination of many years of military co-operation between

the two nations. This agreement included allowances for Guderian’s training of German tank forces in the

Soviet Union when it was still illegal for Germany, under the Versailles Treaty (which ended the First World

War), to develop and field any armed forces other than a 100,000 man army. This ban also precluded the

development of a standing German air force, which was developed in secret, paralleling the armor forces as a

second major component of Guderian’s Blitzkrieg. Of the 62 divisions making up the two German Army

groups that took part in the invasion, six of the divisions were tank units and ten were mechanized infantry

divisions. The entire Polish army, at that time, was composed of only 40 divisions, none of them armored

units, and all of their equipment was inferior in both quality and quantity to that of the invading Germans.

The battle was over in a few short weeks, to be followed by several months of inactivity from both sides

(known as the “Phoney war” to the British and as “Sitzkrieg” in Germany).

Hitler then turned to Scandinavia, which he invaded on April 9th, 1940, taking both Denmark, which fell

without a fight, and Norway, which resisted bitterly for just over a month. On May 10th, the Wehrmacht

invaded France through Belgium and the Netherlands, which fell before a concentrated attack of armor,

airpower, airborne engineers and infantrymen who demolished fortifications and secured bridges all along

their attack routes. This northern thrust was flanked by a southern thrust through the Ardennes, terrain that

had been considered impassable to tanks due to its thick woods and rough hills. Both of these offensives

neatly bypassed the heavily fortified Maginot Line, upon which the French had come to rely for defense

against German aggression. A combination of excellent planning and training by the veteran German forces

and poor operational techniques and low morale among the green French and British forces allowed the

Wehrmacht to capture France in only six weeks. In the fighting for France’s defense, the French army

counted their losses at nearly 90,000, while the British army was decimated, (even though much of its

manpower was rescued at Dunkirk, it was forced to abandon or destroy much of its equipment on the

docks). Throughout the entire operational move west through France, the German army only lost

approximately 27,000 of its number. England stood alone.

Page 9

10

Italy, meanwhile, as Germany’s ally, had annexed Albania and subsequently invaded Greece, where

Mussolini’s forces were still stalled, as they were in North Africa. In order to save the Italian forces, and to

secure the mineral-rich Balkans prior to the upcoming attack on the Soviet Union, the Wehrmacht invaded

Yugoslavia from Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, and Austria, all of whom were now members of the Tripartite

Pact, commonly known as the Axis. From the outset of the battle on April 6, 1941, the 31 Yugoslavian

divisions were outclassed. Hostilities against Greece were also opened on this date from Bulgaria. The entire

Balkan campaign lasted less than three weeks, and eliminated the last ally of the British in the region.

Finally, the Greek island of Crete was captured in a battle initiated by large airborne drops. Starting on May

20th, the operation lasted just over a week and inflicted horrendous losses on the attacking German

paratroopers. The campaign ended just in time for the majority of the German troops involved to be

transferred to the east, where they would participate in the invasion of the Soviet Union, commencing

in June.

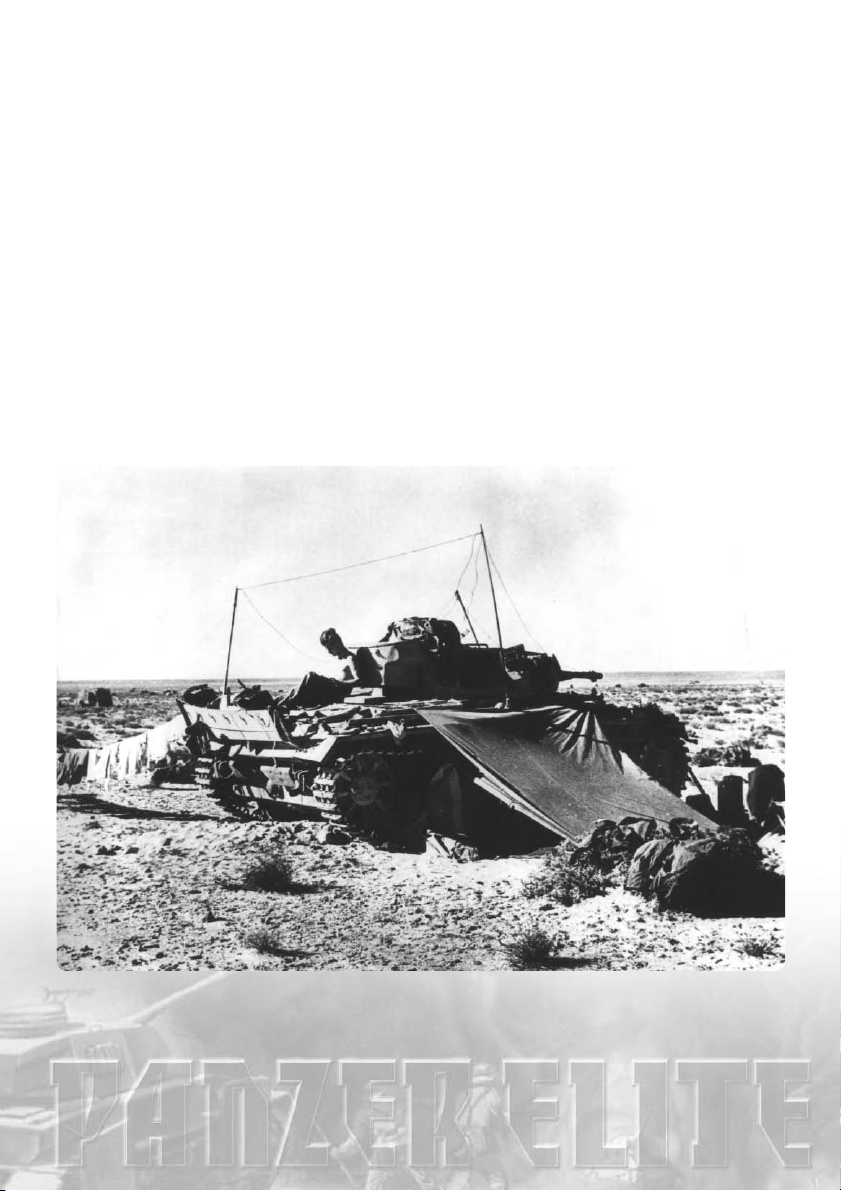

The Desert War. Once again coming to the aid of an ally, Germany sent the Afrika Korps to Libya in an

attempt to support the failed advances of the Italian forces there against the British and Free French. General

(later Fieldmarshall) Erwin Rommel, a hero of the First World War and winner of the Pour le Merite, or

“Blue Max,” arrived in Tripoli with two divisions on February 12, 1941. By the 11th of April, Rommel had

recaptured all of the territory lost to the British offensive of four months prior, and Tobruk was under siege.

After a series of abortive counterattacks in 1941, Rommel withdrew. He resumed the offensive on January

21, 1942 and chased the British back into Egypt. By October, he had exhausted most of his supplies, which

had been arriving only occasionally since the domination of the Mediterranean by the British Navy. The

British counterattack in October, combined with Anglo-American landings in French North Africa on

November 8, 1942, forced Rommel back to Tunisia. The last German forces in Tunis surrendered on

May 13, 1943.

The Eastern Front. Having conquered or intimidated nearly every major nation in Europe, Hitler decided

to move east, into the open country of the Soviet Union. Although Stalin, General-Secretary of the

Communist Party of the Soviet Union and its de facto leader, had known there would be a clash eventually,

he had hoped it would come later, and with the Soviets on the offensive. Operation Barbarossa, as the

invasion was codenamed, therefore came as a surprise to the Soviet forces. It involved the use of nearly the

entire Wehrmacht: almost 4 million soldiers in 180 divisions, over 3,000 tanks, 7,000 artillery pieces, and

2,000 aircraft, plus more than 20 allied divisions. On June 22, 1941, the first day of the attack, over 1,200

aircraft of the Soviet air forces were destroyed on the ground and in the air. In the first two weeks, 89 Soviet

divisions were eliminated, with 300,000 prisoners captured, and 2,500 tanks and 1,400 artillery pieces seized

in just the central region. By July 20, another 310,000 prisoners, 3,200 tanks, and 3,100 artillery pieces had

been captured in Smolensk alone. Although Soviet industry was producing 1,000 tanks and 1,800 planes

every month, their losses were even higher. Three months into the engagement, German troops had taken

the remains of Poland, conquered Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, the majority of the Ukraine, and had

moved the front to a line with Leningrad at its northern tip and the Crimea at its southern end.

Page 10

11

The German Heer, however, was unprepared for the Russian winter. Since they expected that the fighting

would end before the frosts began, the German High Command had not thought to issue winter clothing

and equipment to the Wehrmacht. By December 6, 1941, the German forces had penetrated as far towards

Moscow as they would ever reach. Some German reconnaissance units had even scouted the suburbs of the

city before the first Soviet counterattack of the war struck in the area around Moscow. Leningrad was under

siege. German offensives were halted until the following summer.

In the summer of 1942, the Wehrmacht attacked into the Caucasus region, hoping to capture that oil and

mineral-rich region and deny its resources to the Soviets. Although this thrust gave some impressive successes

at the outset, it culminated in the loss of Feldmarshall von Paulus and his 6th Army at Stalingrad in the

winter of 1942-43. After this battle, the Red Army of Workers and Peasants took the offensive, and the

Wehrmacht was forced to retreat. On July 5th, 1943, the German army conducted its last major offensive in

the area around Kursk. This operation, codenamed Citadel, was known to the Soviets through their

intelligence network, and was prepared for. Their defenses included around 10,000 artillery pieces, including

anti-tank guns and multiple-rocket launchers, and 60 divisions. An average of 3,000 mines were laid along

each kilometer of the front. 300,000 civilians labored to create a defensive network of eight separate

defensive lines, the farthest being almost 150 kilometers behind the front lines. The attackers brought about

2,700 tanks and 1,800 aircraft in 34 divisions into the battle. Such was their strength, that Stalin was forced

to make early counterattacks on August 3rd. This was the most decisive battle on the Eastern Front, and

after this the Wehrmacht would never again be allowed to take the strategic offensive. In the south, the

Soviets advanced through the Ukraine, Romania, and Hungary in 1944. In the north, they recaptured the

Baltic states, and moved into Poland and East Prussia. In early 1945, the Red Army invaded Germany and

captured Berlin, which fell on May 2, 1945, just ahead of the combined US and British advances, pushing

back the struggling Wehrmacht in its final defense of Germany.

The Western Front. The Second Front, which had been promised to Stalin by Churchill and Roosevelt in

order to effectively split Germany’s concentration of troops, did not materialize as promised in 1942. It did

not even take place in 1943. As a concession for the delay, however, the Western Allies decided to invade the

Third Reich’s “soft underbelly” in Italy. On July 10, 1943, an Allied landing codenamed Operation Husky

took place on the southern beaches of Sicily. This attack, unexpected by the Wehrmacht, also had the side

effect of precipitating a rebellion among Mussolini’s Italian generals, who had him arrested. They

immediately began to negotiate their surrender to the Allies. By the end of August, Sicily had been secured.

The “boot” of Italy was invaded beginning on September 3rd, the day Italy officially surrendered to the

Allies. German occupation forces quickly disarmed the remaining Italian forces, and stubbornly resisted the

Allied advances up both sides of the Italian peninsula. By the end of 1943, the Allied advance had only just

reached the heavily defended Gustav Line, just south of Rome. Difficulties in overcoming the stiff German

resistance, compounded by friction between the Allies, enabled the German forces to hold Rome until just

two days before the Normandy invasion. They moved quickly northwards through the summer, but were

stopped again at the Gothic Line, across the top of the Italian peninsula at Florence. This line held until the

beginning of 1945, but by the end of hostilities in May, the entire country had been occupied by the

Allied forces.

Page 11

12

Operation Overlord, the famous landings on the beaches of Normandy in northern France, was the largest

campaign of the Western Allies and the long-awaited opening of the Second Front in Europe. The invasion

fleet numbered nearly 6,500 vessels, of which about 4,000 were actual landing craft. Of 12,000 aircraft

flown into the battle by the Allies, over 5,000 were fighters. More than 10,000 tons of bombs were dropped

on or near the landing beaches the night of June 5th, along with three airborne divisions, which were

dropped on the flanks of the invasion beaches. Five American, British, and Canadian divisions were landed

on the morning of the 6th of June. Although the landing was difficult, the subsequent breakout from the

beachhead was more costly. The Cotentin peninsula with the valuable port of Cherbourg was captured

quickly, however, nearly two months after the landings, the Allies were still being kept on the peninsula and

mostly within 30 kilometers of the invasion beaches. This stalemate was broken when Patton’s Third Army

broke through the German left flank at Avranches, pouring two infantry and two armored divisions through

a narrow corridor in less than 24 hours. This maneuver outflanked the defending German Fifth Panzer and

Seventh Armies, and opened northern France up to continued Allied advances. With the exception of the

short-lived German attempt to capture the port of Antwerp from the Ardennes shortly before Christmas, the

Germans were being pushed back at every turn. This slow, but steady rate of advance held until the Western

Allies joined-up with the Soviet forces at the Elbe river in May. The last holdouts of the Wehrmacht

surrendered on May 11th, 1945 and the war in Europe, for the Allies, was won.

Page 12

2. TANK ACADEMY

13

Essential Qualities of an

Armoured Commander

(British Royal Armoured Corps)

It is essential that a tank crewman understand how his tank is built,

the reasoning behind the design and how these factors will influence

the tactics used in the field. The commander of an armored unit,

regardless of its size and force composition, must also become familiar

with the all the tactics and techniques of tank warfare and how they

are applied in practice.

TANK BASICS

Tanks are made up of three primary facets: Firepower, Protection, and

Mobility, all of which are explained in detail below. In addition to

these three basics, there are several other factors that can heavily

influence the capabilities of individual tanks and their functions in

relation to other military units. These include training, crew

positions, visibility, optics, communications, ammunition stowage,

vulnerabilities, and size.

FIREPOWER

The cannon on a tank is essentially a giant gun barrel. The longer the

barrel, the more accurate and powerful the tank cannon is. The

cannon barrel can have a smooth bore, like a shotgun, or rifling

grooves engraved along its length which impart spin (and therefore

greater accuracy) to the shell in its flight. However, most W.W.II

cannon used some degree of spin-stabilization. An additional feature

which affects the accuracy of the tank gun is the use of a muzzle

brake, also called “muzzle whip”, which reduces the movement of the

barrel during firing, as well as reducing the recoil and its effects on the

tanks structure and crew. The accuracy of the shell is also affected by

several other factors, which together are called the “ballistics” of the

weapon. These factors include the rate of spin, wind resistance and

crosswind. Gravity, range, and the duration of the shell’s flight will

also affect the accuracy of the shell. The ammunition used in tank

guns is generally of the “fixed” type, which means that the powder

charge is fully enclosed and attached to the shell, like a rifle cartridge.

Some of the larger cannon, especially howitzers and most large naval

guns, may use separate-loading ammunition, which means that the

shell is inserted into the breech, then individual bags of powder are

forced in behind it.

a. Sense of Awareness. The

armoured commander must be

tactically aware. He will look

outwards at what the enemy

and other friendly forces are

doing. If he becomes obsessed

with the detailed actions of his

crew or sub-unit, he will miss

opportunities for destroying

enemy and fail in his task.

b. Grip and Leadership. Every

leader has his own style, and

this is right and proper.

However, an armoured

commander must lead from the

front, must be clear and concise

in his actions and orders, and

must not accept second best

from those under him.

c. Speed of Reaction and

Anticipation. A commander

without a flexible attitude of

mind and a sense of urgency

will get left behind in armoured

warfare. Quick reaction,

initiative and the ability to

anticipate are vital.

d. Knowledge. A commander

must know his enemy, his men

and his equipment. Modern

warfare is complex and he must

also understand the procedures

and capabilities of the other

arms with whom he may be

grouped if he is to cooperate

effectively with them.

e. Commonsense. Commonsense

tempers the more volatile

qualities and prevents mistakes.

Page 13

14

As the armor used on armored vehicles grew thicker and more advanced, it became obvious that smaller guns

were incapable of penetrating it. At first, this meant that the production of smaller guns ceased and the

production of larger guns increased. When the development of armor quickly outstripped the capabilities of

even the largest of the currently produced guns, new ammunition was designed to increase the penetrating

power of the guns already in use. Initially, the ordinary solid shot, or armor piercing (AP) round, was used

against tanks, while an ordinary high explosive (HE) shell was used against infantry and other ‘soft’ targets.

The problem with solid shot was that its penetrating power could only be increased through greater weight

that created an increase in the caliber of the gun, higher muzzle velocities, or increase in the chamber pressure

or barrel length. A ballistic cap (APCBC) could also be mounted in order to keep the shot from shattering

against thick armor. This problem was solved first by the Germans. By utilising a shell with a heavy

tungsten-carbide core, (APCR), surrounded with a softer metal and fired through a barrel which tapered as it

reached the muzzle, the softer metal would be squeezed from around the shot and as the barrel pressure

increased, so did the muzzle velocity of the round. An unfortunate side effect was a rapid drop-off in

velocity, which reduced the long-range performance of the round. A simplified version of this, called

discarding-sabot (APDS), used a lightweight collar that fitted around the tungsten carbide core, and dropped

off when fired. This had the advantage that it could be fired out of ordinary barrels and did not require a

tapering bore to maintain the higher barrel pressure.

For low velocity guns and rockets, another technological advance was required. This appeared in the form of

the shaped charge (HEAT), in which the explosive filler was moulded so as to leave a cone-shaped space in

the end facing the target. When the charge detonated, the concentration of explosive forces in that coneshaped cavity created a solid jet of plasma (known as the Monroe Effect) capable of punching through armor.

This generally required a large warhead (at least 75mm) for good effect, but since the round was not

dependent on higher velocity for penetrating power, it could penetrate the same amount of armor at 1,000

Page 14

15

meters that it could at 10 meters. A shaped charge round mounted on the end of a stick and muzzle-loaded

into the 37mm antitank gun was even developed by the Germans! Other types of ammunition, such as

smoke producing shells, was also produced, but was reserved mainly for signalling and for screening troops,

not for fighting. As a final note, ammunition and barrel qualities, due mainly to materials quality and

workmanship, were also a limiting factor in main gun accuracy and effectiveness. These arguments go a long

way towards explaining why the significantly larger 122mm cannons of the Soviet Union were inferior to the

German 88mm and the American 90mm guns at the end of the war.

PROTECTION

The primary feature of a tank is its use of thick armor specifically designed to protect the crew and the

internal components from harm. Tanks were originally outfitted with just enough armor to protect them

from rifles, machineguns, and artillery fragments. It soon became obvious that the armor needed to

withstand attacks from antitank rifles and other tank guns. As these weapons were improved, the armor of

the tank was required to follow or become obsolete and vulnerable. Some weaknesses could be found in

every tank, including places where transmission or exhaust systems passed through the armor, the connecting

ring of the turret to the hull, hatches and viewports, suspension and tracks, and anywhere else that the armor

tended to be thin. These disadvantages were learned by every tanker in an effort to increase his life

expectancy on the battlefield and shorten that of his opponent.

Metallurgical developments prior to World War II included the development of face-hardened armor. This

involved taking a piece of ordinary “homogeneous” plate armor, and heating the front face to a higher

hardness than that of plain steel (normally compounded with nickel) alone. Although it was possible to

harden the entire thickness, it was soon discovered that this caused the armor to become brittle, and

shattered when struck by a solid shot of the same diameter as the armor thickness. Face-hardening allowed

for a harder, but more brittle, front face, which was backed up by a more pliable, easily worked softer plate.

As the war progressed, tanks were outfitted with thicker and thicker plates of face-hardened armor. A

sufficient thickness of face-hardened plate could also cause the solid shot of smaller guns to shatter on

impact, leading to further experimentation in ammunition design.

Tank designers in some countries, most notably the Soviet Union, realized that by making the armor steeply

angled or rounded it was possible to increase the apparent thickness. This had the additional effect of

increasing the likelihood that a solid shot would ricochet off of the hull, and reduced the amount of metal

required to obtain the same apparent thickness, thus decreasing overall weight and increasing mobility.

Rounded armor, especially for turrets, was often made by casting, which was cheaper and faster than welding

or bolting. Bolt-on armor was abandoned early in the war, when it was discovered that following an impact

the bolts flew off and bounced around the inside of the tank killing the crew. Welded armor was often used

when flat plates of angled armor were fastened together, particularly in vehicle hulls. The Germans also

tended to use this method to build their distinctively angled turrets and hulls. When they discovered the

inherent weakness of welded armor seams, they compensated for this by fitting the armor pieces together

using interlocking pieces, like a jigsaw puzzle. The angling of armor was also related to the discovery of “shot

traps.” These were places where the armor could unintentionally cause an enemy shell to ricochet into

another part of the vehicle, and were most often found around the turret. When this caused a ricochet into

the thinner armor of the upper hull, it could allow a relatively weak gun to destroy a very well

armored vehicle.

Page 15

16

As new types of ammunition were developed, tank armor was forced to keep pace. Alternatives to extremely

thick armor were developed. At first, it was simply a matter of making the frontal armor thicker and the rear

armor thinner, since an attack from the rear was less likely. Later, supplemental armor plates were attached

over weak spots. In the field, crews often supplemented their armor with sandbags and spare track links.

Late in the war, wood and cement were used to disrupt the effects of the shaped-charge ammunition used by

low-velocity guns and antitank rockets, and also to protect the hull from magnetic mines and grenades. The

Germans were the first to attach stand-off armor, called Schuerzen, to their tanks. These thin steel plates

were attached to the sides of the turret and the hull by brackets that left a gap between the armor and the

hull. This dissipated the effects of shaped-charge ammunition and also interfered with the flight of ordinary

solid shot, reducing its effectiveness.

Page 16

17

MOBILITY

Most tanks are heavy, slow, and have tracks instead of wheels. Combined with the unusual controls and poor

visibility for the driver, World War II tanks were difficult to drive well. Most tanks were steered by two

levers, each one controlling the speed of one of the tracks. This enabled the driver to turn the tank by

slowing the track in the direction of the turn and speeding up the track on the opposite side. One advantage

of this method of steering was the “neutral steer,” in which one track was moved forward and the other left in

neutral or reverse. This enabled a stationary tank to swivel quickly and this was often combined with, or

used in place of, turning the turret to bring the main gun on to a target as quickly as possible. A large diesel

or gasoline engine provided power.

Tank mobility was dependent upon several interrelated functions, and had to be considered both by its

tactical and strategic implications. These included the power of the engine, its fuel consumption, the weight

of the vehicle, ground pressure, and the expected life of the tracks, roadwheels, suspension, transmission, and

engine. The power of the engine compared to the weight of the vehicle determined the top speed of the

tank. An underpowered vehicle was susceptible to breakdown due to excessive wear on the engine

components. Too powerful an engine could cause excessive wear to the tracks and drivetrain, as well as using

a large quantity of fuel. A large fuel requirement and excess weight, making it difficult to transport or cross

smaller bridges could easily hamper tanks strategic mobility. The ground pressure of the vehicle was one of

the most important tactical considerations, as a vehicle with a low ground pressure could still be mobile in

wet or sandy terrain. The ground pressure could be found by dividing the kg weight of the vehicle by the

number of square centimeters of track on the ground at any given moment, resulting in an expression of

ground pressure as kg/cm2. The lower this number is the greater the area over which the tanks weight is

distributed, preventing it from becoming easily stuck in mud or sand, sliding down hills, and bogging down

in streams or swampy terrain.

Early in World War II, tanks were light, did not require as much power to maintain a good tactical speed,

could be transported easily, and had a low ground pressure even with fairly narrow tracks. This included

such tanks as the German PzKpfw I, II, III, and IV, the American Stuart, Lee and Grant, the British

Crusader, Comet, and Churchill, and the Soviet BT7, T60, and T70. Later, as heavier armor and guns were

introduced, it became necessary to increase the engine power and it was soon discovered that the greater

stress brought on by these developments required wider and stronger tracks and suspension systems. Wide

track pioneers included the German Tiger and Panther tanks and the Soviet T34 series. These tanks were

more maneuverable than tanks of equivalent weight with thinner tracks, and even more maneuverable than

many lighter tanks, including the American Sherman. In an attempt to improve the maneuverability of the

Sherman, American engineers made a set of adapters that were clipped to the existing tracks to spread the

weight out farther. Known as “duckbills” these were not very effective, and wider tracks were eventually

made standard.

The two main types of suspension used were the supported or “roller” type and the unsupported or

“Christie” type. Supported suspensions used smaller roadwheels and included small return rollers on the top

of the track to guide it to the drive wheel. Examples of this type of suspension include the German PzKpfw

I, early PzKpfw II, and PzKpfw II and IV tanks, and the American Stuart, Grant, Lee, and Sherman tanks.

Unsupported suspensions used large roadwheels, with the track riding along the top of the wheel on its

return movement. This type of suspension was pioneered by an American named J. Walter Christie, and had

the advantage that the track could be removed and the tank run on the roadwheels alone in an emergency.

Examples of this type of suspension include the German Panther and Tiger tanks, the British Crusader and

Cromwell tanks, and the Soviet T34 series.

Page 17

18

OTHER FACTORS

A tank could have a powerful gun, thick armor, and excellent maneuverability, and still be unable to beat

inferior tanks in combat if several other factors were not addressed. The Afrika Korps was able to fight while

heavily outnumbered, with older equipment, and hold out for long periods against fresh Allied units due to

their attention to these other factors.

Training. Crew training and experience were probably the most decisive factors of tank warfare. Individual

knowledge of friendly and enemy vehicles, how to use terrain effectively, and crew cohesion and morale were

all results of excellent crew training programs. Because of the experience gained in the early invasions of

Spain, Poland, France, Scandinavia, and the Balkans, backed by long periods of intense basic armor training,

the Wehrmacht had the best trained and most experienced crews. Soviet tank crews did not survive long

enough to gain any battle experience, and were often thrown into action with minimal training. This

problem was compounded by the Soviet penchant for centralized command, a lack of initiative among junior

officers and their adherence to outdated tactics and techniques. By mid-war, however, these problems had

been addressed and the quality of Soviet tank crews increased dramatically. British tankers, having received

some experience in the North African campaign, proved to be quick learners and fought well despite their

often outmatched vehicles. American tank crews suffered heavily at the outset of the North African

campaign, and the unexpected requirement for new replacement crews further diluted the experience levels of

the veterans until well into the French and Italian campaigns. The problems with inexperienced crews

became so troublesome that by the time the Germans began fielding the Panther tank, official policy

recommended that one German tank should be dispatched by no less than five Shermans! By the time of the

invasion of Normandy, German tank crews had often experienced three to five years of combat, while

American crews rarely had more than a year in action, and the majority even less, or none at all.

Crew positions. The crew lived in their tank during combat, and cramped and uncomfortable positions

were made more difficult by poor design. It was quickly discovered that small one or two-man turrets

quickly overburdened the commander, who was often responsible not only for directing the crew and firing,

but loading as well. Early light tanks such as the German PzKpfw I and II, American M3 Stuart, Soviet T26, T-40A, T-60, and T-70, and the French D1B and S35 all suffered from this problem. Interim solutions,

such as raising the commander’s position or giving him a smaller turret of his own gave rise to problems in

his vulnerability as well as increasing the visible height of the vehicle. Difficulties with hatches, especially

with the turretless assault guns, often led to difficulties in mounting and dismounting the vehicle, leaving it

vulnerable for precious seconds while the crew was feverishly trying to get in or out. The cramped positions

also made it difficult to adopt another crewman’s position in the case of casualties. Compared to the earlier

PzKpfw III and IV and the Lee and Grant series tanks, the later Panther and Sherman tanks were spacious.

Visibility. The ability of the crew to see outside of their tank was a very limiting factor in armored combat.

Most commanders and drivers left their hatches open for better vision, and some chose to remain exposed

even during combat. This was due to the restricted view from each position. As the design of tanks became

more important and information was received from crews using them in battle, vision ports and periscopes

were introduced and improved. These usually consisted of glass prisms or blocks through which the

crewmember could look while all of the hatches were “buttoned up”. These changes also influenced

improvements in hatch design. Some tanks, such as the Panther, had comparatively excellent visibility, while

others, such as the Stuart, were at a severe disadvantage with the hatches closed.

Page 18

19

Optics. The quality of a tank’s optics affected not only how well the crew could see out of the vehicle, but

also the accuracy and usefulness of the rangefinder and optical targeting systems. Poor quality Soviet optics

reduced the overall accuracy of their tanks. American and British optics were better than the Soviets but

German glass quality, optical designs and workmanship were the best throughout the war, although they

occasionally suffered from complexity. The utility of an optical system in viewing and determining range

improved the speed and accuracy of the main gun, while its consistent alignment to the bore was critical to

hitting any target. Different methods of gauging range were used. The most common, however, was to

include a simple mil scale on the gunner’s reticule, enabling him to quickly estimate range by the size of the

target vehicle in the sight. As a general conversion, one mil is equal to one meter of width at 1,000 meters,

thus a four meter wide tank covering only two mils on the scale is at 2,000 meters range.

Communications. By the end of the Second World War, nearly every tank had a two-way radio set. At the

beginning of the war, only the German army had realized the need for two-way communications for all

vehicles. The Soviets learned late, and often suffered horrendous casualties due to a lack of communications.

Even the Sherman was initially equipped with a receiving set, in order to allow the platoon and company

commanders to send orders down. This problem was taken care of quickly, however, unlike the Soviet radio

problem, which lasted well into the war. All armies also produced special command, artillery, and

communication vehicles with multiple radios and versions with greater power. These were used to

communicate with higher command, call for and control artillery and airstrikes, and provide reconnaissance

information from far behind enemy lines.

Ammunition stowage. All tanks face the problem of ammunition stowage. Larger supplies for the main

gun means the tank needs to resupply less often, but also leads to a higher risk of crew death by explosion.

The need for ammunition to be readily available to the loader is offset by the need to stow it safely and

securely. Improper ammunition stowage often led to disaster. Sherman crews stored several loose rounds on

the floor of the turret basket. This led to the vehicle receiving the nickname “Ronson” from the British, after

a cigarette lighter which advertised that it always lit on the first try. It also led to the development of wet

stowage, whereby the ammunition was stored in a solution of water, antifreeze, and a rust inhibitor, which

reduced the likelihood of a fire reaching the ammunition before the crew could bail out.

Vulnerabilities. Every tank has its vulnerable points, and experienced tankers knew this and protected their

own, while taking advantage of the enemy’s. Shot traps, usually caused by an angled piece of armor

deflecting shot into a weaker piece of armor (normally from the turret into the superstructure roof) could be

taken advantage of at close range. Weak spots, such as where air exhaust or intakes passed through the armor

or welded joints where face-hardening was weakest, were favorite targets, as were the thinner sides and rear

areas of any tank, gun and vision ports, tracks and roadwheels, and the gap between the turret and the hull.

Additional armor, such as the one-inch plates welded onto many American Shermans and the Schuerzen

armor skirts on many later German tanks helped a great deal, especially against HEAT rounds. Field

modifications and improvised armor, such as boards, sandbags, and spare track sections were often added as

well. This measure of added protection sometimes caused additional problems due to the extra weight and

bulk. Some of the add-on armor welded to the Sherman hull and turret sides was even used as a targeting

aid by German tank crews who knew that the armor was weaker there, effectively negating its value.

Page 19

20

Size. The larger the vehicle, the easier it is to spot and hit. This gave some advantage to the assault guns

with their lower chassis (since they had no turret). A smaller vehicle also requires less armor to cover its

smaller exposed area. Some vehicles, such as the German Tiger, could ignore their large size since their armor

was sufficient to repel almost any attack. Other vehicles, such as the American Sherman, were simply too

large for their weight, trading greater size off against adequate armour protection. The size of some vehicles

was due, in part, to the size of the gun mounted in the turret. Larger guns require larger-diameter turret

rings, which consequently require a wider hull. The larger-caliber ammunition also takes up more room in

the hull, meaning that the vehicle storage capacity for ammunition must be increased, or the number of

shells carried must be reduced. This design trend must continue further, as a larger powerplant and

transmission will be required to move this heavier vehicle at a decent speed.

Page 20

21

3. TANKS IN BATTLE

The armor tactics of World War II were developed

between the wars, primarily in Germany. These tactics

were innovative in concept, considering the armor

branch a weapon of decision and breakthrough. The

majority of other nations distributed slow and heavily

armored tanks among and in support of the “poor

bloody infantry.” The Germans concentrated their light,

fast tank forces together, in an effort to smash the enemy

at one decisive point. Combined with superior training

and excellent co-operation between the tanks and the

supporting air and artillery forces, this technique of

“Blitzkrieg” was soon proven to be sound. The German

tactics were tested in Spain during their Civil War, and

victory gave food for thought to the opposition there,

which included both American and Soviet volunteers.

As other nations recognized the advantages to these

tactics and slowly began their modernization programs,

the Germans swiftly invaded Poland, France, and the

Low Countries, then turned around and swept through

Yugoslavia and Greece, finally turning their sights on the

Soviet Union. By this time, every other modern nation

had begun a crash program to put these new tactics into

practice, and to provide new tanks that could implement

them.

This brings us to the five major roles of the tank in

modern conflict: offensive, defensive, against tanks,

against infantry, and in antitank warfare. Each of these

roles is described below, with an examination of some of

the tactics that have proven effective in that role. Keep

in mind, always, that although aggression in combat is

one of the keys to tank warfare success, as a commander

you must be decisive and flexible, and understand not

only how to fight, but also where and when to fight.

Tank Tips (Lt Col. Ernest D. Swinton, 1916)

Remember your orders.

Shoot quick.

Shoot low. A miss which throws dust in the

enemy’s eyes is better than one which whistles

in his ear.

Shoot cunning.

Shoot the enemy while they are rubbing their

eyes. Economise ammunition and don’t kill a

man three times.

Remember that trenches are curly and dugouts

deep – look round corners.

Watch the progress of the fight and your

neighbouring tanks.

Watch your infantry whom you are helping.

Remember the position of your own line.

Shell out the enemy’s machineguns and other

small guns and kill them first with your

6 pdrs.

You will not see them for they will be

cunningly hidden.

You must ferret out where they are, judging by

the following signs: Sound, Dust, Smoke.

A shadow in a parapet.

A hole in a wall, haystack, rubbish heap,

woodstack, pile of bricks.

They will be usually placed to fire slantways

across the front and to shoot along the wire.

One 6 pdr shell that hits the loophole of a

MG emplacement will do it in.

Use the 6 pdr with care; shoot to hit not to

make a noise.

Never have any gun, even when unloaded,

pointing at your own infantry, or a 6 pdr gun

pointed at another tank.

It is the unloaded gun that kills the

fool’s friends.

Never mind the heat.

Never mind the noise.

Never mind the dust.

Think of your pals in the infantry.

Thank God you are bulletproof and can help

the infantry, who are not.

Have your mask always handy.

Page 21

22

TANKS IN THE OFFENSIVE

The concept of armored warfare is inherently offensive. Tanks are designed to drive through enemy

positions, destroying or bypassing any enemy forces they meet, and pushing deep into enemy rear areas, in

order to wreak havoc on their command, control, communications, and supply systems. They excel in the

capacity to take on all kinds of enemy forces and survive. Offensive armor tactics are founded on the

concepts of speed, surprise, and breakthrough. Moving too quickly for the enemy to react, the armored unit

hits the enemy where they least expect it, then moves through the breach it has created and towards the soft

and complacent supporting units.

Individual tank movement. While

tanks are capable of dealing with very

rugged terrain, drivers must use certain

landscape features to their

own advantage.

Some basic assumptions that underlie

tank driving.

The driver must be careful of obstacles of

all kinds, as these may render the gun or

drive train inoperable.

Water obstacles, including mud, are very

difficult to judge, and should be avoided

whenever possible.

Care should be taken when driving

alongside rivers and streams.

Steep slopes are often impossible for a

tank to climb. Traversing a hill can be

dangerous as the tank may flip over on its

back. It is not recommended in combat

for other reasons, mainly because it

presents a

predictable target.

All of this must be kept in mind while

using the terrain to its best tactical

advantage. Roads should only be used

for travel behind friendly lines, as they are

likely spots for ambush. Thick woods

and villages should also be avoided for

the same reason. Driving across or along

Page 22

23

the top of a hill or ridge is a good way to get spotted. To keep from being silhouetted against the sky, tanks

should be driven below the crest of the hill, on the opposite side from the enemy. Obvious choke points,

such as narrow roads through forests, bridges, fords, road intersections, and mountain passes should be

avoided if at all possible.

Finally, the vehicle itself must be taken into consideration. Some vehicles are more prone to tipping than

others, while the ground pressure of others means that they may be more or less affected by mud. Care

should be taken to avoid too much driving in reverse or pivoting, as these maneuvers, especially on rough

ground, tend to wear the tracks or cause them to come off of their rollers. The engine must be maintained as

well. Naturally, there are times when the most possible power will be needed in combat. Redlining the

engine, however, may result in a blown engine rather than a quick escape. To avoid redlining, try to keep the

engine running at only about 70% of maximum on roads, and 50% of maximum when driving off-road

(lower in extremely hot environments). This will reduce the likelihood of overheating the engine enough to

blow it.

Movement as part of a Platoon. Formation control within an armored unit is as critical a component of

armored combat as the vehicles’ weapons or the ammo that feeds them. Each of the following formations

provide both tactical advantages and disadvantages, usually governed by terrain, battlefield placement and

unit positions. These formations, while not rigid in their spacing or positioning, allow increased tactical

flexibility on the battlefield.

• Column. Column formations allow for the fastest movement of an armor unit along a route, especially if a

unit is passing through restricted terrain. Firepower in the forward and rear arcs of the unit is limited to a

single vehicle each, but is alternately good to the flanks of the unit, where each alternating vehicle in the

column covers each side of the unit with large, overlapping fields of fire. This also allows for heightened

response times to the unit’s flanks by reducing the search area to be covered by each tank.

• Line. Units formed up along a Line or ‘abreast’ formation cover the largest horizontal area of any

formation, while maximizing the unit’s frontal firepower and overlapping fields of fire. The main drawback to

this is severely reduced rear and flank fire coverage and protection. The use of this formation in an assault

should be limited to areas where tactical overwatch can cover the restricted areas of the unit during its

movement or as a defensive formation within prepared positions where other units are positioned to

both flanks.

• Echelon Left and Echelon Right. The diagonal placement of vehicles in a Right or Left Echelon

formation allows the unit to maximize its firing and search arcs from their axis of advance around to include

overlapping cover for their flank. Optimum deployment of a unit in an echelon formation would be along

the edge of a larger unit formation in an advance or defensive position. This allows for added protection or as

a springboard for an encirclement maneuver. This placing, in a defensive action, allows increased flank

protection to prevent an enemy from gaining access to an area to the rear of the main battle line.

• Wedge. The Wedge allows a unit both flanks enjoying good coverage and overlap of firepower as well as

good forward firepower. This formation is best deployed in situations where the threat axis is mainly forward,

but there are possibilities of attempted flanking maneuvers. The Wedge is also good for providing overwatch

for other units and where a unit must cover many others or large areas of open ground. In an attack posture,

the Wedge should only be employed when operating in open or rolling terrain, allowing for good visibility in

all quarters or under the guns of an overwatch.

Page 23

24

• Reverse Wedge. In a Reverse Wedge or ‘Vee’ formation, the tactical concerns of the commander are on

control of the unit. It allows for good fields of fire to the flanks and rear, but severely restricts the forward fire

arcs. This formation also allows a unit the ability to provide self-overwatch capabilities. (Not currently

available to the TC in PE).

• Diamond. If a unit is alone, tactically, or is in a halted state where a threat might come from any direction

and require a perimeter-type defense in 360 degrees, then a good option for the unit commander would be

the Diamond or ‘Coil’ formation. If a unit requires a movement formation to maintain security and good

fields of fire, then another formation would probably be best. (Not currently available to a TC in PE)

Movement as part of a Company. In general, the objectives you are given as a platoon reflect and support

the greater objectives of the company as a whole. The other platoons will also be assigned similar objectives.

While one platoon may be assigned to take a bridge, another may be guarding a convoy which needs to cross

the bridge, while another may be holding a defensive position, and yet another attacking enemy positions as

a feint, in order to draw off his forces. Each of these platoon objectives is essential to the success of the

overall company mission, which, in this case, is to move a convoy safely over a bridge. Knowing where the

rest of the company is supposed to be is of primary importance when engaging distant targets, so as to avoid

accidentally firing on friendly troops. This is especially important when two or more of the platoons in a

company have been given the same objective (usually approaching from different sides). Knowing the

difference in appearance between friendly and enemy units is extremely important in this case.

Another concept of movement within a larger formation, is that of an ‘overwatch’. When there is a

requirement for a unit to safely advance into potentially hostile areas, there is also a need for mutual support

from other units within the larger division. If two or more units have objectives in the same area, one unit

will be able to cover the other as it advances and vice-versa. Each unit will move from one position of relative

safety (such as a hull-down position from one hill to the crest of the next) along the line of the units advance

while the second unit provides direct fire support. Once the first unit is able to traverse the area in question,

it will set itself up in a viable position to cover the second units advance, and so on. A ‘leapfrog’ series of

movements will develop with each unit moving safely under the guns of the other. This continuing sequence

of movements will allow both units to cover more ground, with a higher safety factor, than if both had

covered either alone or as one large force.

Movement as part of a Tank-Infantry team. Infantry units are slower and weaker than armored units.

This means that extra care must be taken to maintain contact with assisting infantry, provide them the

benefit of full (and close) armor support, and avoid becoming separated. In open terrain, this means

advancing in front of the infantry and using searching fire (firing at likely places where the enemy could be

hiding) as needed. In close terrain, especially towns and villages, the infantry should precede the tanks to

flush out enemy antitank teams. Mechanized infantry operations give commanders more tactical flexibility

and mobility in various situations. Infantry that can disembark also allows them to perform as separate unit

in cases where enemy infantry is dug in and would be difficult for armor alone to dispatch them. This type of

force combination presents the opportunity for the half-track or other APC to provide its own direct fire

support for its dismounted troops.

Page 24

25

Concentration of force. Whenever possible, the maximum amount of force should be used to secure an

objective or engage enemy forces. This enables the platoon or company to engage quickly and with

overwhelming force, in order to be immediately ready for an enemy counterattack. This will also help keep a

force from being pinned in place (and becoming an artillery target), and allow it to sustain fewer losses than

if the unit had been engaged piecemeal. In general, this means using a platoon to engage lone enemy units,

and a company to engage enemy platoons. Artillery can also be used as a force multiplier, to distract,

damage, and pin enemy troops. Although concentration of force is one of the primary ingredients of a

successful engagement, it is not necessary, or desirable, for all of the friendly forces to be bunched together.

As a rule of thumb, about half of the unit should engage the enemy unit directly, while the other half moves

around one flank or the other to make contact from the enemy side or rear. Friendly forces should be spread

out far enough to avoid suffering great casualties during an artillery attack or from an unexpected

counterattack, yet still be close enough to see one another, provide mutual support, and still be able to target

the enemy unit that is being engaged.

Breakthrough techniques. By using overwhelming force at a single location, preferably a spot where enemy

forces are known or suspected to be weak, it is possible to break through enemy lines, giving a considerable

advantage to the attacker. Artillery can be used to soften up the enemy positions and use smoke rounds to

obscure friendly movements and prevent the enemy from being able to effectively reinforce the breach. Once

the breakthrough is made, a small force (usually, a force which has sustained losses in the initial attack) is left

behind to keep the breach open, while stronger forces, often made up of fresh reserves, moves deep into

enemy territory. One of the advantages of a breakthrough is the capability to overrun enemy supply bases,

headquarters, and artillery positions. This will disrupt his communications and supply systems, often causing

great confusion among both front and rear echelon units. This, however, requires a very deep penetration

and a force capable of throwing off local counterattacks. More common is the local breakthrough, which is

used to provide a tactical, rather than strategic or operational, advantage. In this case, the breakthrough force

is used to attack the enemy front lines in the flanks and rear, often creating confusion and causing troops to

withdraw from their positions. Local penetrations can also be used to seize objectives such as bridges, road

intersections, hills, and villages. These objectives can then be held against enemy counterattack, while fresh

reserves are brought through the breach to reinforce and expand these positions behind enemy lines. By

maintaining a fast operational tempo and high mobility, exploiting even a small breach in the enemy lines

can serve to force the enemy forces to spread out and often to throw their reserves into the battle, thus

weakening their front lines and possibly enabling further breakthroughs.

Reserves on the offensive. Reserves are an essential part of any offensive, even if they are small. On a

platoon or company scale, half of the unit can be used to engage the enemy, while the other half serves as a

maneuver element and is capable of reacting to unexpected events, such as enemy counterattacks or

exploiting a sudden breach in enemy lines. When engaging using superior forces, reserves provide a layer of

protection against this kind of event. Reserve units can also be used to relieve weaker units at the front, thus

preventing a rout or by providing fresh troops for a breakthrough. A company should keep a full platoon in

reserve whenever possible, while a platoon should hold back one or two tanks. These reserve forces should be

kept close enough that they can easily be moved forward to engage the enemy, yet stay far enough back to

avoid contact with forward enemy units and be free to move around to engage their flanks or protect the rear

of forward friendly units. One technique often used by platoons is to engage an enemy with the main body,

then send the reserve tanks to attack the enemy in the flank or rear. Once they have begun their attack, the

main body then becomes the reserves, and moves up behind the rest of the platoon, with the platoon leader

normally joining up with the new main body and continuing the offensive pressure to the maximum

extent possible.

Page 25

26

TANKS IN THE DEFENSIVE

Originally designed to seize and hold the initiative by taking the offensive, tanks can also be very useful on

the defensive. Properly prepared, tanks can provide fire support from a position that is nearly invulnerable to

enemy fire, and still be able to make a tactical withdrawal to previously established positions in the rear.

They can be used as mobile support, to reinforce wherever the fighting is worst. Best of all, once the

defensive operations have destroyed the enemy’s will to fight, these same tanks can then be used to initiate

counter offensive operations against those same battle-weary troops.

Fighting positions. Tanks, like infantry, can and should take advantage of cover. By siting a tank properly

in a “hull-down” position, it is possible to protect the tank hull from enemy fire and provide a smaller target

to the enemy. This can be done by driving up to the crest of a hill, even a small one, and stopping just short

of the top, but high enough so that the main gun can be depressed to fire over it. This allows the

commander to see and the gunner to shoot at enemy vehicles without exposing the entire tank. This works

best when there are trees or buildings to the rear, so that the silhouette of the tank turret is not so obvious. A

platoon of tanks on a hill in hull-down positions is a very difficult target and a very effective antitank

position, and one from which it is relatively easy to withdraw. Trees also make good cover. Whenever

possible, move the tanks deeper into the woods and destroy the trees to the front of the vehicle, creating a

lane of fire down which the tank can see to attack enemy troops as they expose themselves through the gap.

This method is also easy to retreat from, and gives the enemy great difficulty as your tank is completely

hidden in the woods. The only problems with this method are that it takes time to prepare, including

ensuring that there is a way out of the woods, and that enemy infantry may infiltrate the forest and conduct

close assaults on the tanks, unless friendly infantry can provide flank security. Finally, buildings make good

cover for tanks on the defensive. Tanks parked inside buildings are very difficult to see, and may observe and

fire from windows and over broken sections of wall. The building itself also provides some protection, and

Page 26

27

retreat is easy, as buildings are inevitably connected to other buildings by roads. If you want to have the

tanks fall back to other buildings after they are engaged (to avoid artillery and infantry attacks), do not forget

to have infantry units protecting their flanks from close assaults, especially in urban areas where the

movements of enemy infantry may be difficult to detect.

Defensive formations. Unlike the offensive formations, which are based on a moving platoon (and are often

used on the defensive when conducting a mobile defense or counterattack), the positions of tanks in a

defending tank platoon are often dictated by the availability of good positions. Most often, the platoon is

brought on line, allowing the entire section to bring its guns to bear on any target that comes in range. This

is especially useful when the platoon is in a hull-down position firing over the crest of a hill or ridge, or

concealed in the treeline. When using terrain features such as buildings and craters for cover, each tank

should be positioned so as to make the best use of its individual cover. Additionally, each tank should be

placed so that it can provide covering fire to at least one other vehicle in the platoon. This will enable it to

assist in the event that the other tank is forced to move to the rear, thereby preventing enemy tanks from

moving in for a flank or rear shot.

Defense in depth. When the enemy is strong and he is very likely to penetrate friendly lines, a defense in

depth can be constructed to withstand this attack. This can only be done successfully if there are enough

troops on hand to fill these defenses. The use of restrictive or difficult terrain and the careful siting of

friendly forces may make this task easier. A thin line of infantry mixed with light antitank guns will slow the

enemy down, yet allow him to penetrate the first defensive line. The second line should be right behind the

first, and made up of more infantry and heavier antitank guns, which should stop him and make him

vulnerable to attacks from front and rear. Finally, the third line should be immediately behind the second

line and made up of infantry and tanks in a supporting role, which can be used to stop the enemy if the