Page 1

Microsoft® Combat Flight Simulator 3.0

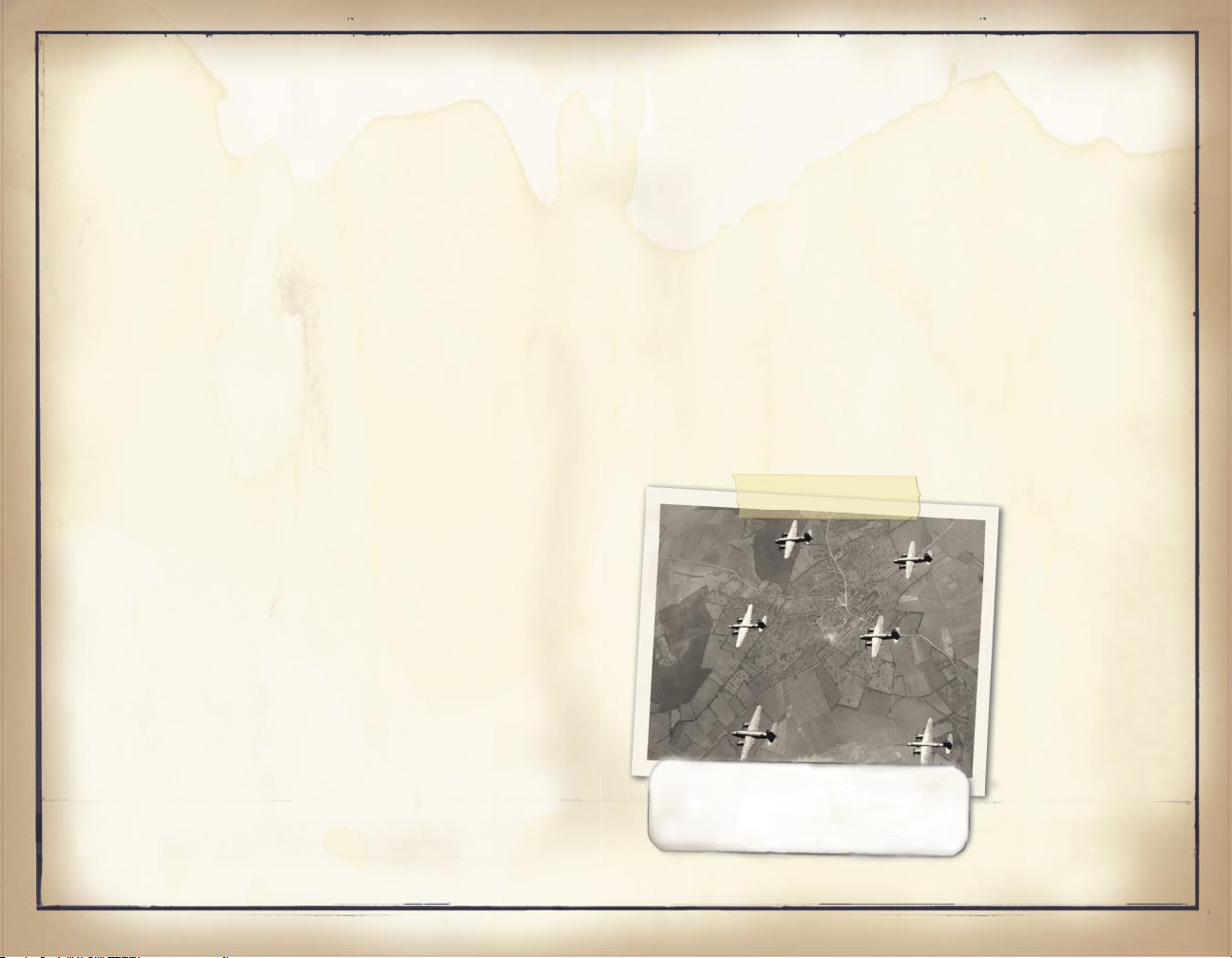

Air Force Historical Research Agency Photo

UNDERSTANDING THE TACTICAL AIR WAR

handbook

Page 2

Subject: CONTENTS

Contents

Welcome to the

Tactical Air War! ... 1

Events and People in

the Tactical Air

War ................. 7

Key Players in the

Tactical Air War:

The CFS3 Hall of

Fame ............... 21

Acknowledgements...... 30

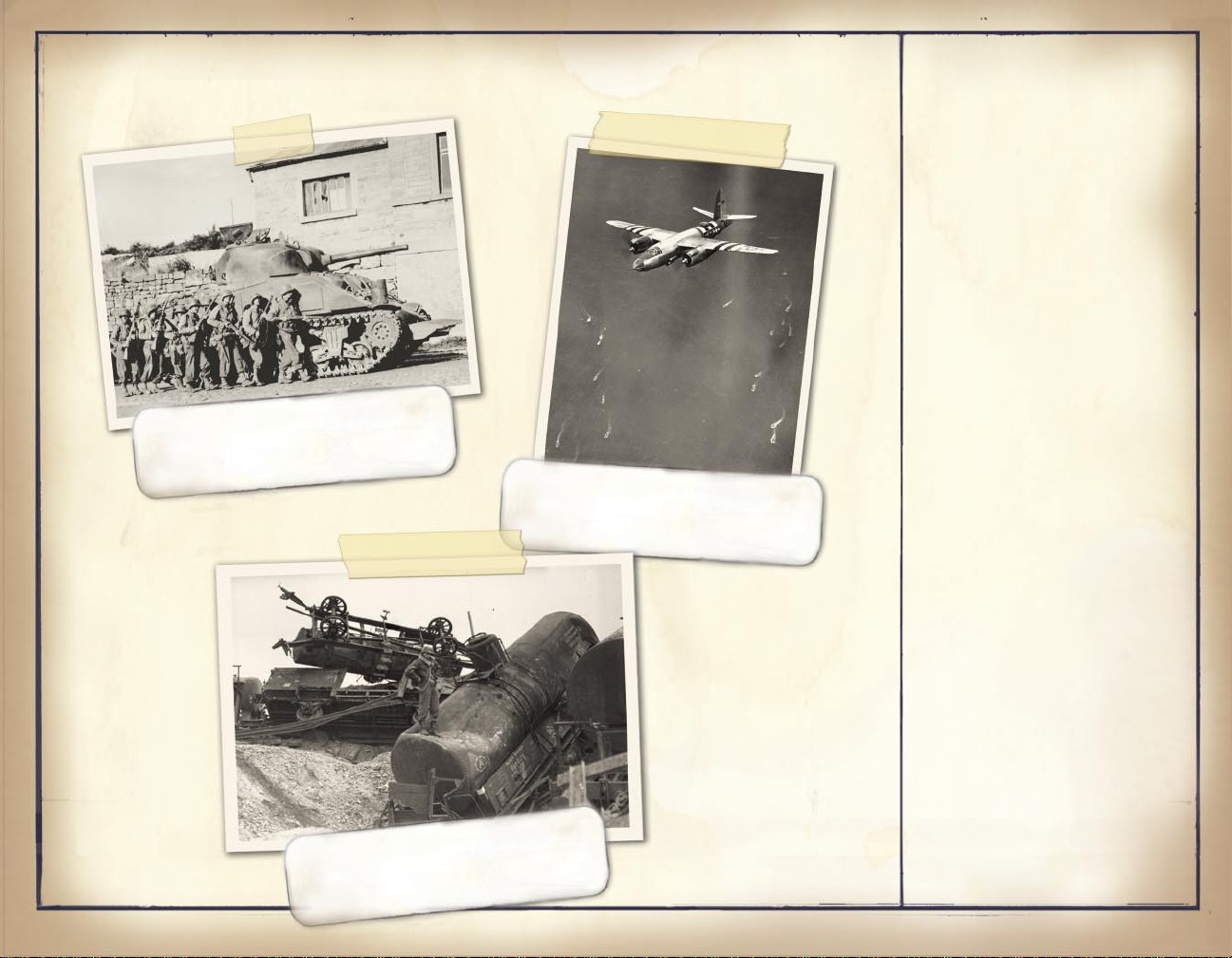

REMEMBER: OUR MEN AND MACHINES

ON THE GROUND LOOK A LOT LIKE

THEIRS.

RAIL CARS AFTER A POUNDING BY

ALLIED FIGHTER BOMBERS.

National Archives and Records Administration Photo

A B-26 MARAUDER FLIES OVER THE

NORMANDY INVASION FLEET.

Air Force Historical Research Agency Photo

Air Force Historical Research Agency Photo

Recommended Reading... 32

Glossary.............. 36

* * *

Authorized licensees of this game

may print (or have printed at their

expense) a single copy of this

manual for their personal home use

in conjunction with the play and

use of the game on this CD.

Page 3

Subject: TACTICAL AIR WAR

- 1 -

Welcome to the Tactical Air War!

“Schlachtfliegerei”

Schlacht means slaugh-

ter. Schlachtfliegerei

means ground attack, the

most dangerous and least

glamorous part of wartime

flying. There is no room

here for romantic illusion,

no pretense of chivalry;

one is down on the deck

where the targets (people,

vehicles, installations,

and fortifications) may be

clearly seen. The ground

attack pilot is exposed to

every bit of flak, every

machine gun, every rifle,

every pistol. Denied him

is the acclaim accorded

fighter pilots. The chances

of winning fame as a

Schlachtflieger are as slim

as those of survival....

--From Jay P. Spenser,

Focke-Wulf 190: Workhorse

of the Luftwaffe

So you thought you were going to be

a “knight of the air,” jousting high in

the clean blue sky, far above the clouds

and even farther from the mud and squalor of the war on the ground.

Instead you nd yourself in a ghter

bomber, scraping over hostile territory

at 200 feet with the terrain rising to

meet you. You’re ying down the muzzles

of massed antiaircraft guns and dodging

small arms re to attack enemy air elds,

trains, tanks, trucks, and troops.

Performing masthead-level attacks on

enemy shipping adds its own thrills and

threats. Some of your targets have more

and bigger guns than a whole formation

of bombers. If enemy re doesn’t get

you, the blast and debris from your own

low-level bombing and stra ng can bring

you down. In this kind of war there’s

more danger and less glory for everyone.

Welcome to the tactical air war,

pal!

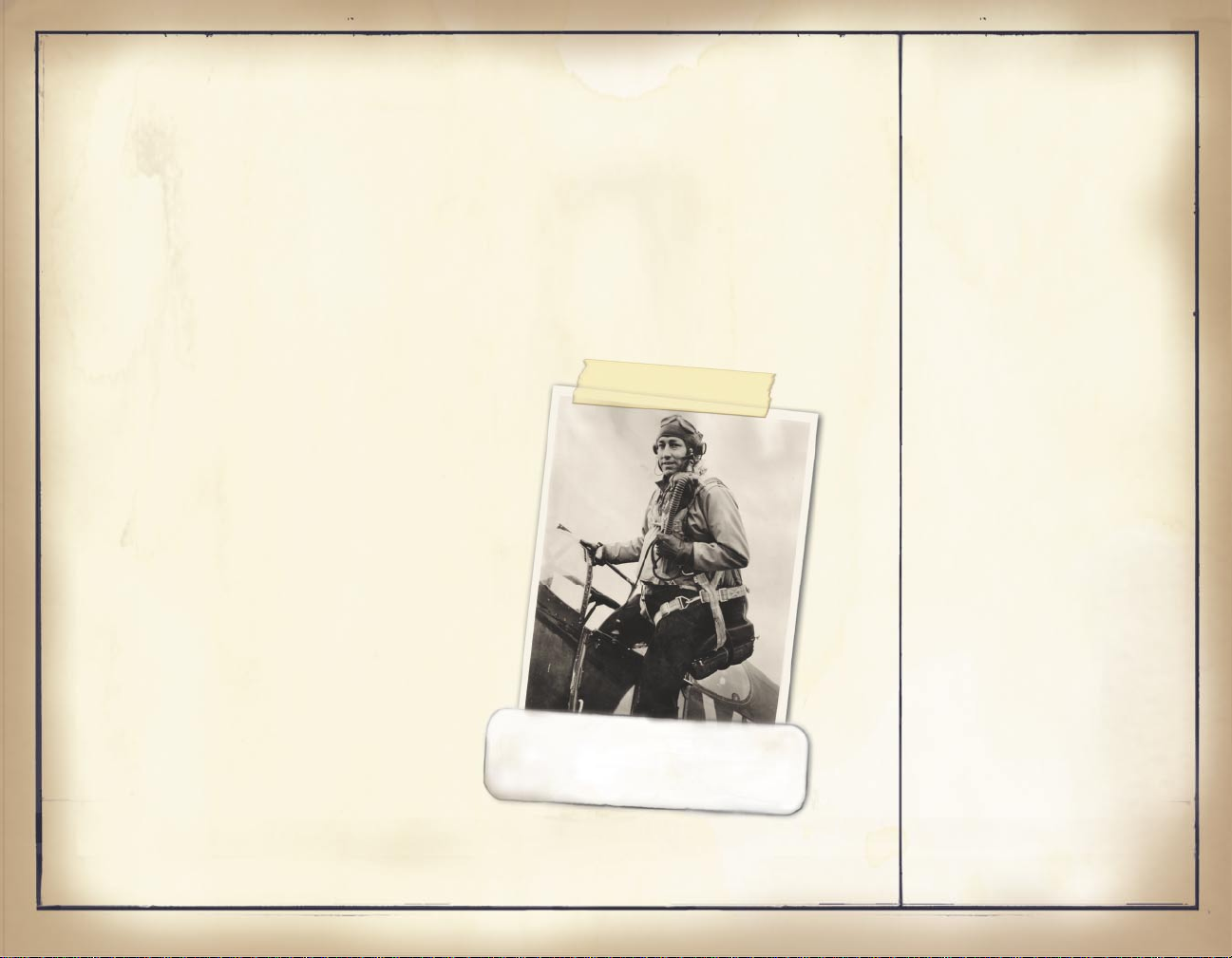

Air Force Historical Research Agency Photo

“WE TOOK A BIT OF A BEATING ON

THE GROUND BUT BOY DID WE DISH

IT OUT IN THE AIR.”

--General Elwood “Pete” Quesada

Page 4

Subject: TACTICAL AIR WAR

WHAT REALLY HAPPENED: The lowdown on the tactical air war

BY MID-1943 THE AIR WAR IN EUROPE HAD SETTLED

INTO A DEADLY PATTERN FOR FIGHTER PILOTS ON BOTH

SIDES. MOST WERE INVOLVED IN THE STRATEGIC AIR WAR;

ESCORTING OR ATTACKING BOMBERS WAS THEIR PRIMARY ROLE,

AND COMBAT IN THE FRIGID SKIES AT 20,000 TO 30,000

FEET WAS THE NORM.

AS THE POSSIBILITY OF AN ALLIED INVASION OF

THE CONTINENT TOOK ON GROWING CERTAINTY, THE TACTI

CAL AIR WAR IN THE WEST HEATED UP AND EMPHASIZED A

DIFFERENT PILOT ROLE--FLYING CLOSE AIR SUPPORT. THIS

ROLE PUT WOULD-BE HIGH FLYERS DOWN ON THE DECK FOR A

DIFFERENT KIND OF WARFARE BASED ON AIR-GROUND TEAM

WORK. FIGHTER-BOMBER PILOTS WERE PART OF THE ARMY

TEAM, WITH DIRECT RESPONSIBILITY TO ASSIST THE ADVANCE

OF FRIENDLY FORCES ON THE GROUND, WHILE KEEPING ENEMY

TROOPS AND SUPPLY LINES REELING UNDER BULLETS, BOMBS,

AND ROCKETS.

THE GERMAN ARMY HAD ALWAYS VIEWED AIR POWER AS

SUBORDINATE TO THE FORCES ON THE GROUND. CLOSE AIR

SUPPORT, USING AIRCRAFT TO ASSIST THE ADVANCE OF

TROOPS AND MOBILE FORCES ON THE GROUND, WAS A CEN

TRAL PART OF THE BLITZKRIEG ACROSS EUROPE BETWEEN 1939

AND 1940. IT WAS ALSO A BASIC FEATURE OF COMBAT IN

THE CAULDRON OF THE EASTERN FRONT. AS THE WAR IN THE

WEST INTENSIFIED, ESPECIALLY AFTER THE ALLIED INVA

SION OF FRANCE COMMENCED IN JUNE 1944, THE GERMANS

PRESSED MORE AND MORE AIRCRAFT INTO TACTICAL SER

VICE EVEN AS THE STRATEGIC BOMBING CAMPAIGN AGAINST

-

-

-

-

-

GERMANY INCREASED THE LUFTWAFFE’S NEED FOR HIGH-ALTI

TUDE INTERCEPTORS. BF 109 AND FW 190 PILOTS HAD TO

STRAFE AND DIVE BOMB TO STOP OR SLOW THE FLOOD OF

MEN AND MATERIEL OF THE INVADING ARMIES. JU 88 MEDIUM

BOMBERS SWOOPED DOWN FROM NORMAL BOMBING ALTITUDE

TO PLACE THEIR ORDNANCE WHERE IT WOULD DO THE MOST

GOOD: RIGHT IN THE LAPS OF THE ENEMY. EVEN THE NEW

GERMAN JETS SAW SOME SERVICE IN THE TACTICAL AIR WAR.

THE ALLIES TOOK LONGER TO FULLY EMBRACE THE

POTENTIAL OF A TACTICAL ROLE FOR COMBAT AIRCRAFT,

BUT PERFECTED CLOSE AIR SUPPORT BETWEEN 1943 AND 1945

BY ADDING NEW TECHNOLOGICAL VARIATIONS TO THE TAC

TICAL THEME. ALLIED PILOTS (BEING DIRECTED BY AIR

FORCE LIAISON OFFICERS ON THE GROUND TO ENEMY GROUND

TARGETS, FRIENDLY FORMATIONS IN NEED OF ESCORT,

OR INCOMING BANDITS) CARRIED OUT A BLITZKRIEG OF

THEIR OWN AGAINST ANYTHING THAT MOVED IN THE ENEMY

SECTOR. THUNDERBOLTS, LIGHTNINGS, MUSTANGS, TYPHOONS,

TEMPESTS, AND SPITFIRES FLEW FIGHTER BOMBER DUTY

TO SUPPORT THE WAR ON THE GROUND, WHILE MITCHELL,

MARAUDER, AND MOSQUITO BOMBERS ADDED THE FORMIDABLE

STRAFING POWER OF MULTIPLE GUNS AND CANNON TO THE

DESTRUCTIVE FORCE OF THEIR BOMBS.

FOR BOTH SIDES, DETERMINING THE PRECISE LINE

BETWEEN FRIENDLY AND ENEMY TERRITORY IN A FLUID AND

CLOSE-FOUGHT SITUATION ADDED TO THE DIFFICULTIES TAC

TICAL PILOTS ALREADY FACED.

-

-

-

- 2 -

Page 5

Subject: TACTICAL AIR WAR

- 3 -

Altitude is still your friend...but

you’ve got less of it to work with!

From a tactical pilot’s point of

view, you’ve got one strike against

you as soon as you leave your base and

head into enemy territory--you’re ying

close to the deck without the luxury of

altitude. Altitude is life to a ghter

pilot, providing the high ground from

which to attack enemy aircraft, as

well as room in which to dive away from

attackers. Flying ve or six miles above

the ground provides plenty of room for

maneuvering, attacking, and evading.

“The Mission of the

Tactical Air Force”

MISSIONS--The mission

of the tactical air force

consists of three phases of

operations in the following

order of priority:

First priority--To gain

the necessary degree of

air superiority. This will

be accomplished by attacks

against aircraft in the

air and on the ground, and

against those enemy installations that he requires

for the application of air

power.

Second priority--To pre-

vent the movement of hostile troops and supplies

into the theater of operations or within the theater.

Third priority--To

participate in the combined effort of the air

and ground forces, in the

battle area, to gain objectives on the immediate

front of the ground forces.

--From War Department

Field Manual FM 100-20:

Command and Employment of

Air Power (21 July 1943)

Air Force Historical Research Agency Photo

For a ghter bomber pilot altitude is still your friend, but you’ve

got a lot less of it to work with since

most missions are own at 12,000 feet

or lower (usually much lower), right

on down to the deck.

USAF Museum Photo Archives

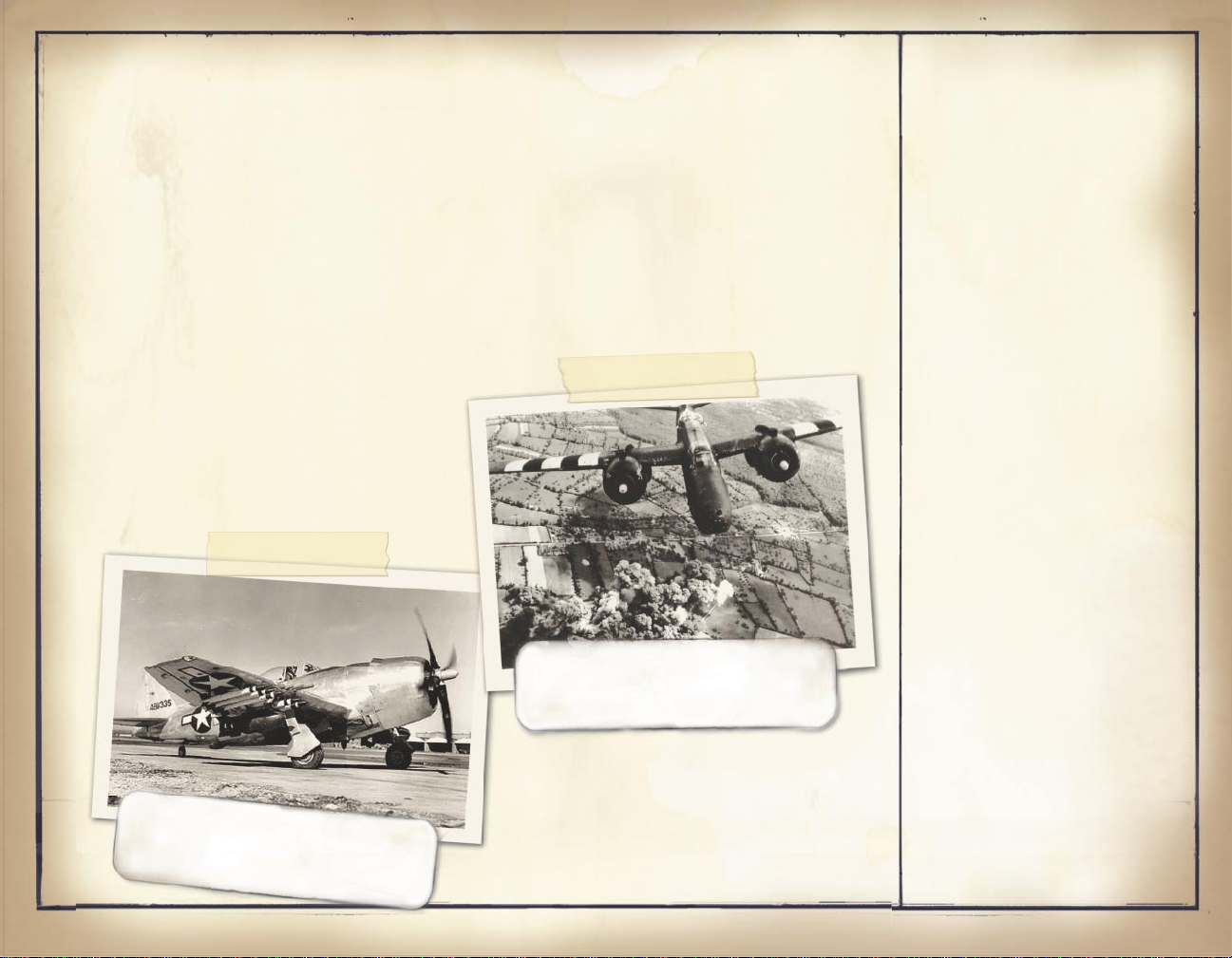

A THUNDERBOLT CARRIES THE COM-

PLETE GROUND ATTACK ARSENAL:

GUNS, BOMBS, AND ROCKETS.

DOUGLAS A-20 MEDIUM BOMBER IN

LOW-LEVEL ATTACK ON CHERBOURG

PENINSULA.

Page 6

Subject: TACTICAL AIR WAR

A few additional worries

In addition to reduced altitude

and the hail of ak and small arms re

coming up at you as you approach targets

on the ground, you have a few additional

worries as a ghter-bomber pilot:

- Encountering aireld defenses. If you

and your buddies swoop down to beat

up an enemy aireld, the guy who ies

through rst is the lucky one, because

he might catch the antiaircraft

defenses off guard. By the time the

rest of you approach the target those

gunners are wide awake and lling the

air with ak.

- Pulling up in time. Diving a heavy,

powerful aircraft from low altitude makes for a thrilling pullout,

if you’re lucky. If you’re not both

attentive and lucky, you may xate

on the target until it’s too late

to pull out.

- Identifying appropriate targets--now!

While you’re thinking about the

target, the ak, and the need to pull

out before you become part of the

landscape, you also need to make

sure that the target you’re attacking belongs to the enemy. Skimming

along at low altitude and high speed

over a crowded battleeld doesn’t give

you a lot of time to make vital decisions. Are those enemy troops? Are you

sure the squat form of a heavy tank

glimpsed through foliage is an appropriate target? You may never know for

sure whose cause will prot from the

bombs you just dropped.

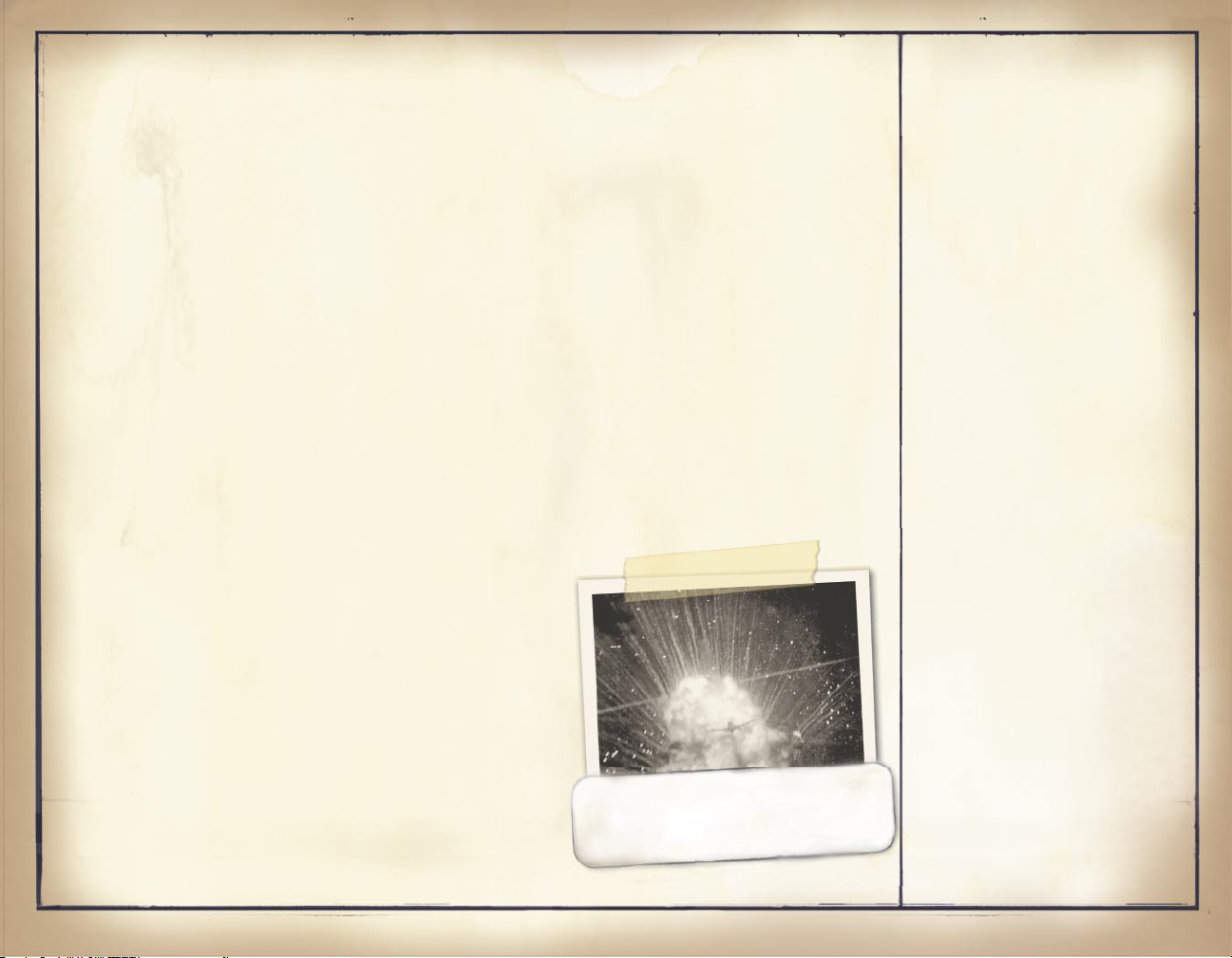

- And nally, getting caught in your

own explosions. When you attack surface targets from low altitude you

risk getting caught in explosions of

your own making. Trains and motorized transport full of fuel and ammo,

the volatile contents of fuel and

ordnance dumps, and even locomotives

with a boiler full of high-pressure

steam--all of these targets can blow

up in a big way, lling a once empty

piece of sky with pinwheeling chunks

of shrapnel. Even the roadway beneath

enemy vehicles can be hazardous, as

bomb blasts can heave hunks of pavement into the same airspace you’re

occupying.

Three Critical Factors

for Fighter Bomber

Pilots

...strafing passes...

bring out three critical

factors in a fighter bomber

pilot’s war.... One, any

misjudgment, target fixation, or too-late attempts

at aiming corrections will

send the airplane into the

target, ground, or nearby

trees or other obstructions. Two, if the target

is a load of ammunition or other explosives,

it can--and very likely

will--explode right in the

pilot’s face, sending up

a fireball, truck parts,

slabs of highway, stillto-explode ammo, and other

debris right into the path

of the airplane. Three, if

a pilot is seriously hit by

flak in [a] low-altitude

attack, his chances of ever

reaching enough altitude

to allow a bailout are slim

indeed....

--From Bill Colgan,

War II Fighter Bomber Pilot

World

- 4 -

Page 7

Subject: TACTICAL AIR WAR

- 5 -

Another little problem: Enemy fighters

While you’re concentrating on the

enemy below, don’t forget the most dangerous and persistent threat any combat

pilot faces: enemy ghters attacking

from superior altitude. Getting bounced

from above while going after ground targets is an ever-present danger, so you

and your buddies have got to take turns

ying combat air patrol over the target

area to keep the opposition busy while

the rest of the team beats up targets

on the ground.

Now this kind of teamwork is what

you joined up to do, right? Not quite.

You’ll be craning your neck and straining your eyes to spot incoming bandits,

mixing it up with enemy ghters as you

match your skills against skilled adversaries, but remember, this is dog ghting with a difference. Even if you’re

ying a relatively light and nimble

ghter, your plane’s ordnance load makes

it heavier and less responsive; you can

drop like a rock in a dive. Power and

gravity combine to eat up altitude in

a hurry, and the ground is never very

far away.

If you’re ying one of the heavyweights in your air force’s inventory,

the ground can reach up and grab you.

In a P-47 Thunderbolt or a Do 335 Arrow,

or even a big German jet, you’ve got

to juggle the need to get the target

in your sights against the need to pull

out in time. If you cut it too ne,

you can haul back on the stick to point

the nose up at what appears to be the

last moment and discover that your

plane simply won’t cooperate. With all

its weight and power, it will continue

to sink despite your best efforts and

“mush” right into the ground.

“I don’t believe in all this divebombing [stuff], it ain’t natural.”

Many new ghter-bomber pilots

longed for the classic ghterpilot role

they’d read and dreamed about, in which

the ground was for the ground-pounders and the sky above the clouds was

reserved for dashing aviators. This

made for a dif cult adjustment:

...fighter pilots were slow to

appreciate the value of close-support operations. One flyer aptly

summarized the rank-and-file perception of the new task when he

said... “I don’t believe in all

this dive-bombing [stuff], it

ain’t natural.”

--Thomas A. Hughes,

Over Lord:

General Pete Quesada and the

Triumph of Tactical Air Power

in World War II

Results You Can See

“There were times we

could actually see our

troops move forward after

we had knocked out a German

88 or tank that was holding

up the column. We knew we

were making a difference.”

--Veteran fighter bomber

pilot Quentin Aanenson

Air Force Historical Research Agency Photo

A GERMAN MK IV TANK DESTROYED

BY AERIAL ATTACK.

Page 8

Subject: TACTICAL AIR WAR

- 6 -

The payoff: Unique satisfactions

So given the catalog of dangers, why

would you want to y close air support

missions? Because this job provides some

unique satisfactions:

- Even if you’re a loner--and many

ghter pilots are--there’s a lot to

be said for being part of a team;

especially if it’s a winning team.

Protecting your guys on the ground and

helping them to advance by suppressing enemy troops and weapons adds real

meaning to your part of the struggle.

- There’s also a lot to be said for

instant grati cation--and few things

are as gratifying to a combat pilot as

seeing a tempting target blow up in a

big way.

- Seeing close-up the effect of your

guns, bombs, and rockets on the enemy

does a lot for your con dence and your

feeling that the results are worth the

risks. Flying close air support also

provides a sense of personal power and

effectiveness that is only tempered by

the fact that the “clean blue sky” of

high-altitude plane-to-plane combat is

replaced by distressing glimpses into

the hellish landscape of the war on

the ground.

- Another plus for the tactical pilot

is the knowledge that just being there

over the front lines gives a real

lift to your guys on the ground, while

depressing the spirits of the enemy.

- There’s also plenty of encouragement in knowing that your contribution isn’t just emotional--all armies

understand that close air support

plays an important role in making

progress on the battle eld and in the

theater of operations. Your missions

are a signi cant part of the bigger

picture. What you do or fail to do

every day can contribute to the larger

success or failure of your nation’s

forces in this war.

The “Moral” Effect of

Attack from the Air

Moral Effect--The moral

effect of heavy air attack

against land forces can

hardly be exaggerated.

Not only will air attack

lower the morale of the

enemy, but the sight of

our own aircraft over the

battlefield raises the

morale of our own troops

to a corresponding degree.

Seeing enemy aircraft shot

down has an encouraging

effect.... On the other

hand, the constant appearance of unmolested enemy

aircraft tends to demoralize troops and disorganize plans. Apprehension

of heavy air attack

restricts military activity by ...confining troops

to areas that afford concealment, and by preventing

movement during daylight.

Soldiers are naturally

quick to react to the general air situation in their

neighbourhood....

--

Army/Air Operations

(British War Office, 26/GS

Publications/1127, 1944)

Air Force Historical

Research Agency Photo

A THUNDERBOLT SCORES A DIRECT

HIT ON AN AMMUNITION TRUCK.

Page 9

Subject: EVENTS AND PEOPLE

- 7 -

Events and People in the Tactical Air War

The campaign in CFS3...

As a pilot in Microsoft Combat

Flight Simulator 3, you y in the historical framework of the tactical air

war in northwest Europe starting in

mid-1943, but there’s a signi cant

difference. The skill and perseverance

you and your squadron or Staffel bring

to each battle can alter the tactical situation and the timeline of the

campaign. This open-ended and exible

campaign means you can in uence events,

alter history, and extend the timeline

to add new technology to your arsenal.

How you handle these tactical and technological advantages will determine the

outcome.

Before you take to the sky, it

helps to understand what really happened

during WWII. This will not only give you

something to shoot at--but also something to shoot for.

In CFS3, it’s 1943, and no one

knows what’s going to happen, or how

the war will turn out--but here’s the

way it was.

...and what really happened

The campaign in northwest Europe

during 1943 and 1945 marked a dramatic

high point in the events of WWII and

the fortunes of the warring nations.

It began with the Third Reich in rm

control of “Fortress Europa,” and ended

with Germany--and much of Europe--in

ruins.

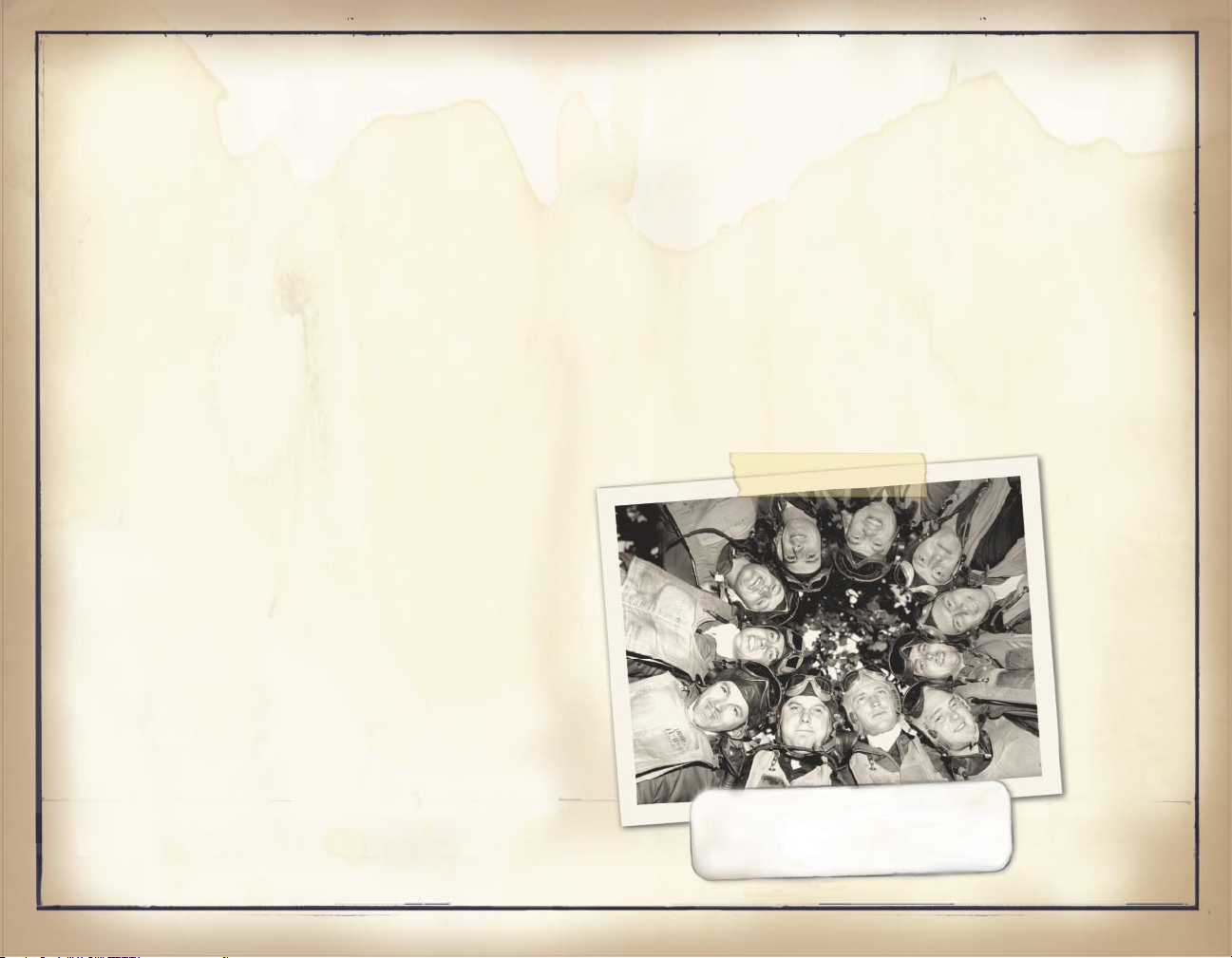

Air Force Historical Research Agency Photo

ACES OF THE 354TH “PIONEER

MUSTANG” FIGHTER GROUP.

Page 10

Subject: EVENTS AND PEOPLE

- 8 -

The situation in mid-1943

In mid-1943 there were no dedicated

tactical air forces operating in northwest Europe. Of course the tactical role

was always part of the Luftwaffe’s mandate, but most of its tactical efforts

were focused against Russia. The Allied

focus was on a strategic goal--using

heavy bomber forces, escorted by ghters, to destroy Germany’s ability

to make war. German day- and night ghter pilots’ rst responsibility was

to attack the bomber formations that

threatened the expanding Reich.

All this began to change as planning for the Allied invasion of Europe

took shape. It became clear to the

Allies that the invasion would never

take place without air power. Air power

techniques worked out in North Africa

and Sicily during 1943 showed how effective tactical air power could be, and

plans were put in motion to use this

weapon to the fullest. Air power would

pave the way for forces on the ground

by providing close air support.

Pre-invasion activities

In 1943 the U.S. Ninth Air Force

moved from Italy to England, and the RAF

created the Second Tactical Air Force

(2TAF). These Allied tactical air forces

faced two daunting pre-invasion tasks:

- To disrupt the German army’s ability

to transport reinforcements and supplies by road, rail, or river.

- To reduce the Luftwaffe’s ability to

seriously impede the planned Allied

invasion.

For its part, the Luftwaffe had to

do its best to resist the mounting tide

of Allied air and land forces, and to

support the German army. Even in reduced

circumstances, the Luftwaffe’s best

efforts remained formidable.

Air Force Historical Research Agency Photo

BRIDGE AT BULLAY, GERMANY

AFTER ATTACK BY THUNDERBOLT

FIGHTER BOMBERS.

Page 11

Subject: EVENTS AND PEOPLE

- 9 -

The “Mighty Eighth” goes looking for

trouble on the ground

Even before tactical air forces

were in place, ghter pilots of the

strategic U.S. Eighth Air Force (the

Mighty Eighth) assigned to escort the

heavy bombers into Germany were increasingly freed to roam further a eld from

their lumbering charges in search of

enemy ghters. The idea was to nd

trouble before trouble found the bombers. To meet this threat, more Luftwaffe

ghter pilots were ordered to take on

the Allied escorts instead of focusing

entirely on the bombers.

By January 1944, General Jimmy

Doolittle, in charge of the Mighty

Eighth, made destroying the German

ghter force a top priority. To encourage his ghter pilots, Doolittle offered

ace status to those who destroyed ve

aircraft on the ground. Some pilots

who had won aerial victories by out ying their opponents complained that this

was the “easy” way to become an ace, but

ying into a wall of ak and small-arms

re while attacking an air eld didn’t

seem so easy to those who tried it.

In February, the Eighth Air Force

launched its “Big Week” operation with

a series of heavy bomber raids against

the German aircraft industry coordinated

with medium bomber and ghter bomber

attacks on Luftwaffe assets in France,

Belgium, and Holland. Throughout the

spring, German ghter losses in the air

and on the ground mounted; more signi cantly, the Luftwaffe lost half of its

irreplaceable veteran pilots before the

invasion began.

Air Force Historical Research Agency Photo

B-26G MARAUDER MEDIUM BOMBERS

IN ATTACK FORMATION.

Page 12

Subject: EVENTS AND PEOPLE

The tactical air forces join the fray

The U.S. Nineth Air Force and the

RAF’s Second Tactical Air Force soon

joined these efforts and, as winter

turned to spring, the pre-invasion air

campaign intensied. Two Tactical Air

Commands of the U.S. Ninth Air Force

(IX TAC under General Ellwood “Pete”

Quesada and XIX TAC under General O.P.

“Opie” Weyland) combined efforts with

the British Second Tactical Air Force

to smash rail transport, bridges, and

airelds.

Phase 1: Railways. Sixty days

before D-Day (D-60), the Allies’ focus

fell on rail centers, with ghter bombers (as well as medium and heavy bombers) striking marshaling yards and major

rail junctions. The railway phase continued right up to and after the Allied

armies fought their way onto the shores

of France on June 6.

Phase 2: Bridges. At D-46, the

Allies began to isolate the German

troops that occupied the invasion

battleeld from reinforcements and supplies by destroying bridges on the

Seine below Paris and on the Loire below

Orléans. Both medium bombers and ghter

bombers participated in this phase, but

the nimble ghter bombers proved to be

the best tool to achieve the pinpoint

accuracy this task required. Like the

rail phase, this bridge-busting duty

continued on after the Allied invasion

had begun.

Phase 3: Airelds. At D-21, the

Allies added German airelds within

130 miles of the invasion area to

their target list. This phase continued

until D-Day.

Between these attacks and the

demands on German ghter resources

resulting from the Allies’ strategic bombing campaign, by June 6 the

Luftwaffe simply wasn’t a factor in

Normandy. This situation wouldn’t last

for long, as the German ghter force

wasn’t nished yet. Within weeks the

Luftwaffe increased its strength in

Normandy, ying from small, improvised

airstrips to avoid attack by Allied

ghter bombers. Soon, the tactical

air war would reach its furious height

as the American, British, and German

armies engaged in their winner-take-all

struggle for control of Europe.

“If I didn’t have

air superiority,

I wouldn’t be here.”

On June 24, Eisenhower’s

son John, a recent West

Point graduate, rode with

his father to view the

invasion area.

“The roads we traversed

were dusty and crowded.

Vehicles moved slowly,

bumper to bumper. Fresh

out of West Point, with all

its courses in conventional

procedures, I was offended

at this jamming up of traffic. It wasn’t according

to the book. Leaning over

Dad’s shoulder, I remarked,

“You’d never get away with

this if you didn’t have air

supremacy.” I received an

impatient snort:

“If I didn’t have air

supremacy, I wouldn’t be

here.”

--Richard P. Hallion,

Air Power Over the Normandy

Beaches and Beyond

- 10 -

Page 13

Subject: EVENTS AND PEOPLE

- 11 -

The invasion: Off the beaches-and into the bocage

Once the invasion was under way,

the Allied tactical air forces took on

their toughest task: direct participation in the land battle. This included

attacking enemy forces and providing

close air support for friendly troops

and armor on the ground.

On June 6, 1944, 150,000 Allied

troops stormed ashore on the Calvados

coast of Normandy. A cloud of Allied

aircraft, newly adorned in black and

white “invasion stripes” to make their

identity clear to nervous gunners on

the ground, controlled the air over the

beachhead. American and British ghters

ew continuously over the invasion area,

ending their patrols with attacks on

coastal defenses, enemy strong points,

bridges, and rail targets. These attacks

slowed the arrival of German reinforcements, giving the invading armies additional time to consolidate their toehold

on the Continent.

Both invading armies made initial

progress inland, but they soon ground

to a halt as German resistance stiffened. The British were stuck outside

Caen, blocked by the armor of Panzer

Group West. The Americans punched

their way off the beaches, only to nd

themselves stymied north of Saint-Lô

by what General Omar Bradley called

“the damndest country I’ve seen,” the

Norman hedgerow country, or bocage.

This 20-mile swath of small elds

enclosed by towering ancient hedges saw

some of the most vicious infantry combat

of the war. American troops groped their

way into the maze of hedgerows, which

the Germans had already in ltrated,

and came under attack from three sides

in each gloomy enclosure. Every eld

was like a small fortress with preplanned elds of machine gun, mortar,

and artillery re. With no more than a

hundred yards of visibility this determined defense was unnerving. The bocage

had been there for a thousand years,

but nothing in the Allied planning had

addressed ghting through this nightmarish terrain.

General Quesada on the

Hedgerow Stalemate

“We were flabbergasted

by the bocage.... Our

infantry had become paralyzed. It has never been

adequately described how

immobilized they were by

the sound of small-arms

fire among those hedges.”

--General Elwood Quesada,

U.S. IX TAC

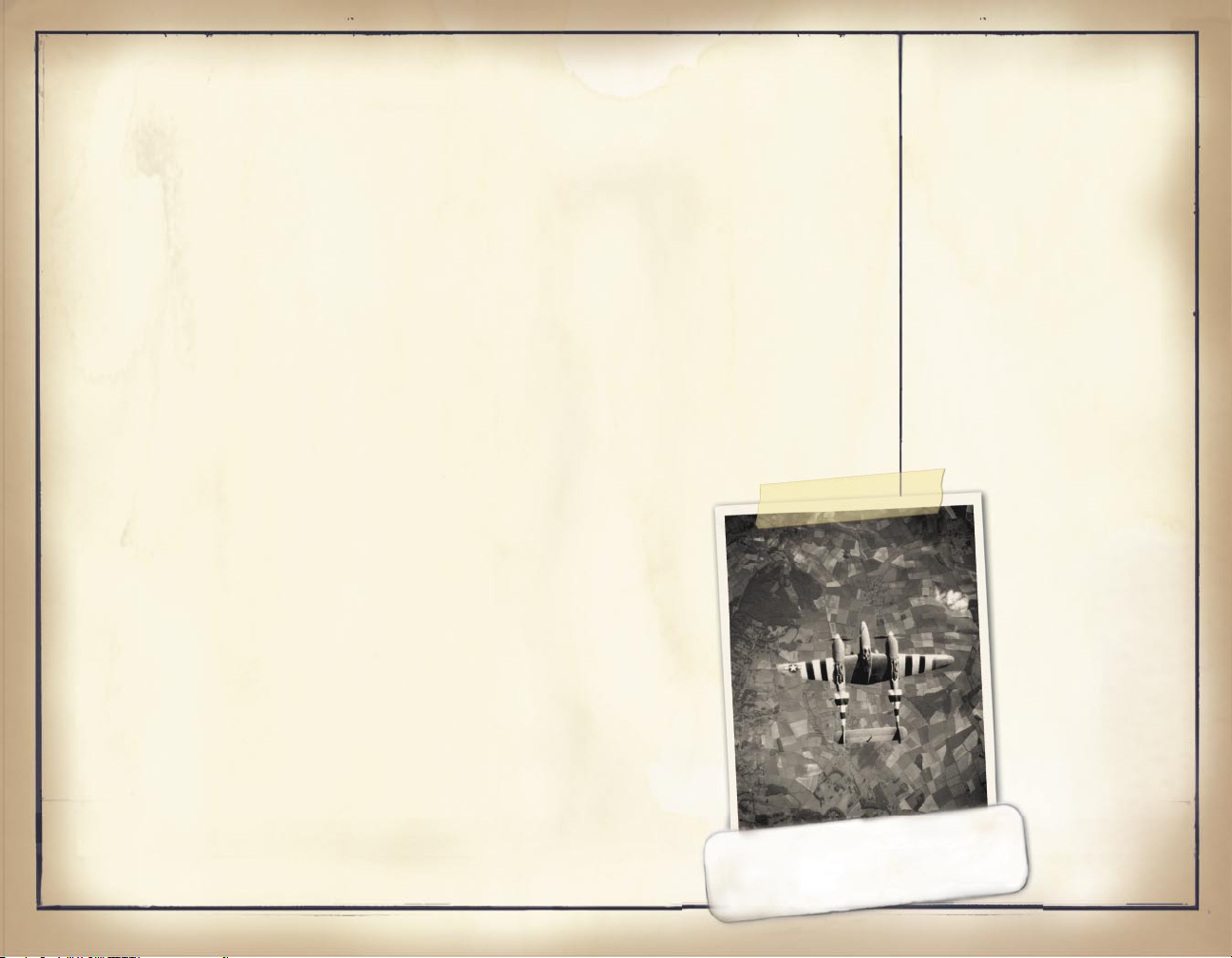

Air Force Historical Research Agency Photo

P-38 LIGHTNING WITH BLACK AND

WHITE “INVASION STRIPES.”

Page 14

Subject: EVENTS AND PEOPLE

Ending the impasse

Goals set to be attained within

days by the Allied command remained out

of reach for weeks, and each small gain

of ground came at a staggering cost.

To end this impasse, the Allies once

again turned to air power. Two operations, codenamed GOODWOOD and COBRA,

were intended to break the stalemate on

the ground by pouring ordnance onto the

battleeld from the air.

GOODWOOD was designed to help the

British break out of the stalemate

around Caen and into the open country

to the east, where tanks could operate effectively. The operation began

on July 18 when 4,500 aircraft from

the RAF Bomber Command and the U.S.

Eighth and Ninth Air Forces attacked

the area held by Panzer Group West.

This enormous bombardment, violent

enough to ip 60-ton tanks and drive

hardened combat veterans into hysteria, allowed the British to force their

way onto the Caen-Falaise plain. This

forward movement was supported by the

tactical air forces, which blasted enemy

tanks, suppressed mortar and antitank

re, and delivered ordnance beyond the

range of friendly artillery. However,

within two days the advance lost its

momentum, in part due to this operation’s success in achieving its secondary goal of drawing German armor

away from the American sector, where

Bradley’s forces were stuck in the

bocage.

In the American sector, operation

COBRA beneted from the British breakout effort. Devised by General Omar

Bradley, COBRA began on July 25 with

a massive but botched aerial bombardment that blasted holes in the enemy

lines and sent German forces reeling,

but also killed or wounded hundreds of

U.S. troops. Bradley quickly capitalized

on these gaps; his First Army forces

attacked across a moonscape of bomb

craters in an advance that moved four

armored divisions almost 35 miles--all

the way from the hedgerows around SaintLô to the open country near Avranches.

As the speed of the assault increased,

good weather allowed IX Tactical Air

Command ghter bombers, under the command of General Elwood “Pete” Quesada,

to provide devastating close air support. Guided onto targets by Army Air

Force liaison ofcers riding in command

tanks, Thunderbolts and Mustangs littered the roads with the burning wrecks

of German vehicles. This air-ground

teamwork proved to be a winning combination that would come into its own in

the Allied dash across France and into

Germany.

No Headlines for

Tactical Pilots,

but High Praise from

Omar Bradley

...On June 20, Bradley

asked Quesada to thank

his pilots for “the fine

work they have been doing

and the close cooperation

they have given the ground

troops. Their ability to

disrupt the enemy’s communications, supply, and

movement of troops has been

a vital factor in our rapid

progress in expanding our

beachhead. I realize that

their work may not catch

the headlines any more than

does the work of some of

our foot soldiers, but I

am sure that I express the

feelings of every groundforce commander, from squad

leaders to myself as Army

Commander, when I extend

my congratulations on their

very fine work.”

--Thomas A. Hughes,

Lord: General Pete Quesada

and the Triumph of Tactical

Air Power in World War II

Over

- 12 -

Page 15

Subject: EVENTS AND PEOPLE

The breakout: Air-ground teamwork

and the dash across France

On August 1, with the momentum of

the breakout growing, Bradley activated the Third Army under the command of General George S. Patton. From

now on, Weyland’s XIX TAC would support

the Third Army advance, while Quesada’s

IX TAC was assigned to aid Bradley and

the First Army.

Patton’s forces raced west from

Normandy into Brittany, and then pushed

south into the Loire valley before

swinging east toward Le Mans. Bradley’s

First Army also swung to the east to

provide added pressure on the Germans.

Meanwhile, General Bernard Montgomery

coordinated the advance of his British

and Canadian forces in a drive south

from Caen, catching German General von

Kluge’s Seventh Army between Allied pincers and effectively encircling it.

To support this increasingly rapid

movement, the tactical air commands had

to revise their priorities and methods.

Pre-planned missions didn’t work in a

uid and rapidly changing situation-by the time the ghter bombers arrived

at their objective, friendly forces

might already have taken it. Two types

of impromptu missions proved especially

effective in this environment:

- Flying armed reconnaissance missions,

pilots received radioed updates on

the current location of the “bomb

line” that marked the boundary between

friendly and hostile territory. They

also reported threats on the ground

and hammered enemy troops, tanks, and

guns wherever they found them.

- At the same time, armored column cover

missions coordinated air power with

tanks by radio to protect the advance

of friendly armor while suppressing enemy resistance. With little air

opposition, pilots were often given

permission to sweep the roads up to

30 miles ahead of the columns they

were assigned to protect, clearing

the way for a rapid advance.

The result of using these two

new types of missions was a far more

rapid advance than even the Allies had

anticipated, creating a growing threat

to all German forces west of the Seine.

This threat became reality when the

Germans planned a counterattack.

The Allies intercepted and decrypted

von Kluge’s orders and, combining resistance on the ground with air strikes,

they stopped the German counterattack

at Mortain.

On August 15, the Canadian First

Army took Falaise, and the Allied armies,

converging from the north, south, and

west, squeezed the retreating German

forces into a “pocket” between Falaise

and Argentan. This pocket was less than

15 miles wide and was shrinking rapidly,

with the only exit to the east.

Armored Column Cover

Speeds the Allied

Advance

Four- and eight-ship

flights hovered over the

lead elements of armored

columns, ready to attack on

request, to warn the tanks

of hidden opposition, to

eliminate delaying actions.

These flights never returned

to base until new flights

came to relieve them. With

this airplane cover always

present...obstacles, which

might have taken hours to

surmount, were eliminated

in a few minutes.

--

Air-Ground Teamwork

on the Western Front

(published by Headquarters,

Army Air Forces,

Washington, D.C.)

- 13 -

Page 16

Subject: EVENTS AND PEOPLE

The Falaise “pocket”: Tac air in all

its glory and horror

The next four days demonstrated

the full and terrible potential of

tactical air power. As more and more

German troops and armor were crowded

into the shrinking pocket, British and

U.S. ghter bombers reduced the milling

men and vehicles to a bloody, burning

shambles.

Rocket-ring Typhoons and strang

Spitres, in coordination with Allied

infantry and armor, relentlessly pounded

the packed enemy columns. U.S. Ninth

Air Force pilots ew deep interdiction missions against enemy road, rail,

and bridge targets, as well as aggressive sweeps to maintain air superiority,

swatting down Luftwaffe ghters before

they could get into the air.

Allied tactical pilots stayed on

the job as long as the daylight lasted,

ying as many as ve or six missions a

day, stopping only to refuel and re-arm.

The air over the Falaise pocket was so

crowded with aircraft that coordination

became an issue, and midair collisions

took a toll among pilots focused on

destroying the enemy.

As the Allied advance gained momentum and the carnage reached a crescendo,

one Allied air objective changed signicantly. Instead of destroying bridges

and routes by which German forces and

supplies could enter the area, bridges

were to be left intact for the pursuing

Allied ground forces; the goal now was

to prevent the Germans from escaping and

reforming the remnants of the Seventh

Army to ght another day.

Thus bottled up, 10,000 German soldiers died along a road that came to

be called the le Couloir de la Mort-the “Corridor of Death.” Another 50,000

were taken prisoner. And the remnant of

von Kluge’s army--perhaps 20,000 men-managed to escape to the east only after

abandoning almost all their vehicles

and heavy weapons. Some ghter bomber

pilots who swooped down to strike the

eeing enemy were shocked by the devastation and carnage. What they found

was a hellish scene beneath a blackened sky full of the smoke and stench

of the battleeld. The piled corpses of

men and horses, the shattered and burning remnants of soft-skinned and armored

vehicles, and a litter of abandoned

equipment were all that remained along

the cratered roads near Falaise.

For those who had wondered about

the effectiveness of tactical air power,

Falaise was a gruesome revelation. Even

for those who had counted on its effectiveness, the results, while benecial

to the Allied cause, were disturbing.

Falaise: A Scene

from Dante--or

Hieronymous Bosch

“The battlefield at

Falaise was unquestionably

one of the greatest “killing grounds” of the war.

I encountered scenes which

could be described only by

Dante.”

--Allied Supreme

Commander Dwight Eisenhower

* * *

Perhaps the twisted allegories of Hieronymous Bosch

would have been more fitting a choice, for Dante,

at least, offered hope.

--Air Force Historian

Richard P. Hallion,

Power Over the Normandy

Beaches and Beyond

Air

- 14 -

Page 17

Subject: EVENTS AND PEOPLE

The race toward the Rhine

As the remnants of the shattered

Seventh Army ed eastward, additional

German forces in Normandy swelled the

retreat. However, like all major German

retreats of the war, this was an organized and disciplined process. Despite

hot pursuit by the Allied armies and

continuing harassment by the tactical air forces, 240,000 Germans got

across the Seine in the last dozen days

of August and streamed toward Belgium,

Luxembourg--and Germany. Patton’s army

began its pursuit on August 21 by crossing the Seine, and in the next ten days

pushed almost 200 miles eastward to the

river Meuse. Other British and U.S.

forces liberated Paris on August 25 and

pushed on into Belgium and Luxembourg.

Seeking an opportunity to counterattack, the Germans deployed troops near

the mouth of the river Scheldt, denying the Allies use of the vital port

of Antwerp. This move was part of a

plan (called “Autumn Mist”) to drive

an armored wedge through the Ardennes

forest and across the Meuse to Antwerp,

separating the British in the north

from the Americans in the south. The

resulting struggle, which began with

an assault that bulged and almost broke

the Allied lines, is better known as

the Battle of the Bulge.

The Battle of the Bulge

Like many major actions of the

Second World War, the outcome of the

Battle of the Bulge was decided by air

power. When the Germans began their

last major offensive of the war on

December 16, the dense, heavy cloud

cover over the battle zone made lowlevel ghter bomber patrols difcult

to impossible, temporarily negating

Allied air superiority, but also limiting the effectiveness of the German

tactical aircraft assembled to assist

the offensive.

For this ght all Allied tactical air power--including the U.S. Nineth

Air Force’s IX and XIX Tactical Air

Commands and the British Second Tactical

Air Force--was concentrated under

the command of RAF Air Marshal Arthur

Coningham, who in turn assigned General

“Pete” Quesada of the U.S. IX TAC to control air power on the north side of the

bulge, while the British 2TAF focused on

the south side. There were three Allied

air priorities:

- To achieve and maintain air superior-

ity over the battleeld.

- To cooperate with ground forces in

the destruction of enemy weapons and

transport.

- To interdict enemy supplies by attack-

ing road, rail, and communication

centers.

Jack Stafford Follows

Orders on His First

Mission

“Ready for your first

show, Staff?” asked Woe

Wilson. “Keep up with me.

I’ll be busy enough without looking after you--just

watch my arse.”

We took off for the

French coast. Woe watched

the heading--I watched

Woe’s tail.

When we returned the

intelligence officer asked

if we had encountered much

flak. “Yes, quite a bit,”

said Woe. “Dieppe was the

heaviest but they hosed us

a bit from all the other

ports.”

I stood there, my mouth

open. “Flak! What bloody

flak?” Good-natured laughter rocked the room.

Woe said, “He was watching my arse and doing it

well.” Just then a ground

staff man approached with

a jagged piece of steel in

his hand. “This was just

removed from your aircraft’s spinner, Staff.”

—Veteran fighter pilot

and CFS3 historical advisor

Jack Stafford

- 15 -

Page 18

Subject: EVENTS AND PEOPLE

- 16 -

Strict radio silence had kept the

Germans’ plans from being intercepted,

and the surprise was complete when 24

Wehrmacht

divisions crashed through

the Allied lines. Twenty-four hundred

tactical aircraft had been assembled

to support this thrust, and a 60-milewide breech in the Allied line quickly

became the westward “bulge” that gave

this battle its name. For three days the

Allied air forces fought the Luftwaffe

above the cloud cover, keeping the

German ghters from carrying out their

close-support duties beneath the overcast and claiming 136 victories in

the process. The Luftwaffe pilots were

hampered not only by bad weather, but

also by inadequate training and lack

of experience in tactical air support,

since by this stage of the war their

leadership understandably emphasized

air-to-air combat skills to counter

the tactical bombing campaign that was

reducing German cities to rubble.

The Battle of the Bulge took place

over some of the roughest terrain in

Europe, during the hardest winter in

memory. The weather soon deteriorated

to the point that, for the four days

between December 19th and the 22nd,

Allied and German aircraft alike could

hardly get off the ground. Once again,

the opposing air forces were ghting

on equally unfavorable terms.

To restrict enemy supplies and slow

the German advance, Eisenhower’s strategy required U.S. forces to take and

hold the crossroads at Saint Vith and

Bastogne, an already perilous task that

became practically impossible without

tactical air support. The “bulge” soon

grew to its maximum depth, extending

about 50 miles west of what had been the

American lines. U.S. forces soon evacuated Saint Vith, but the 101st Airborne

Division hung on at Bastogne.

National Archives and Records Administration Photo

U.S. SOLDIERS GET SOME CHOW

IN THE WINTER LANDSCAPE OF THE

“BATTLE OF THE BULGE.”

Page 19

Subject: EVENTS AND PEOPLE

Patton’s “weather prayer” pays off

Chang at the uncooperative weather

that made life miserable for infantryman and airman alike, General George

Patton ordered the Third Army chaplain to devise a “weather prayer” to be

published throughout the Third Army by

December 14, two days before the Battle

of the Bulge began:

“Almighty and most merciful

God, we humbly beseech thee, of

thy great goodness, to restrain

these immoderate rains with which

we have had to contend. Grant us

fair weather for battle. Graciously

hearken to us as soldiers who call

upon thee that, armed with thy

power, we may advance from victory

to victory, and crush the oppression and wickedness of our enemies,

and establish thy justice among men

and nations. Amen.”

This higher version of “air-ground

teamwork” apparently did the trick,

and on December 23 the murky weather

that had hung over the Ardennes broke,

unleashing Allied air and ground forces

and dooming the last major German offensive of the war to failure.

With massive numbers of American

and British ghter bombers lling the

sky and blasting ground targets at will,

the Luftwaffe could no longer affect the

situation on the ground. Even returning

from a mission was dangerous for German

pilots, as their Allied counterparts

timed aireld attacks to coincide with

the return of ghters low on fuel and

ammunition.

Now Allied medium bombers joined

in to cut off rail transport into the

area, while U.S. and British ghter

bombers pursued enemy tank columns down

increasingly narrow roads. Once they

hit the lead tank, the immobilized column

could be destroyed in detail, a scene

played out over and over again. German

troop concentrations suffered the same

fate as the tank columns. Thunderbolts

bombed enemy positions just a few hundred yards from friendly forces. German

road and rail trafc fell under the same

hammer blows.

By Christmas Eve, the German advance

ground to a halt. On Christmas day, the

Allies counterattacked, Patton relieved

the 101st Airborne in Bastogne, and

Montgomery’s forces attacked from the

north to cut off a German retreat.

Allied tactical aircraft ruled the skies

over the battleeld, but they would soon

face the Luftwaffe in a decisive air

battle.

The Tactical Air War

from Two Points

of View

“We took a bit of a

beating on the ground but

boy did we dish it out in

the air.”

--General “Pete” Quesada,

IX TAC after the

Battle of the Bulge

* * *

“The Third Reich received

its death blow in the

Ardennes offensive.... The

American fighter bomber

destroyed us.”

--General der Jagdflieger

Adolf Galland

- 17 -

Page 20

Subject: EVENTS AND PEOPLE

- 18 -

The Luftwaffe’s last gamble:

Operation Bodenplatte

With their nal ground offensive collapsing under the intolerable pressure of Allied tactical air

power, the Luftwaffe planned an all-out

air assault on 27 Allied airbases in

Belgium, Holland, and France. The goal

of Operation

Bodenplatte

(“Baseplate”)

was to break the air supremacy of the

Allied ghter force and allow the weakened Luftwaffe to focus on the strategic

bomber threat. Set for early morning on

New Year’s Day--January 1, 1945--it was

a desperate gamble that would cost the

Luftwaffe dearly.

Poor planning, inadequate briefings, a lack of experienced pilots, and

poor coordination with ak gunners on

the ground cost the Luftwaffe a third

of the 900 aircraft it threw into this

large-scale surprise attack. More signi cantly, over 200 pilots, including

almost 80 experienced leaders and commanders, never lived to see more than

the rst day of 1945. About a third of

the aircraft lost fell to “friendly”

antiaircraft gunners, some of whom

remained uninformed about the ight

schedule. In other cases, bad weather

delayed takeoff, putting pilots in the

air over batteries that had expected

them earlier.

The one thing

Bodenplatte

pilots

had going for them was surprise. The

last thing the Allies expected was

a massive attack by an air force they

knew was on the ropes, least of all on

New Year’s morning. Some Allied air elds suffered extremely heavy damage,

while others were visited ineffectually

by very small numbers of ghter bombers.

It took awhile for the Allied air forces

to react, but they were soon ying multiple sorties to blunt or entirely stave

off the low-level attacks.

By the end of the day nearly 500

Allied aircraft had been destroyed,

almost all of them on the ground, with

the heaviest damage falling in the

British sector. This was a weighty blow,

but all of these wrecked aircraft were

replaced within a couple of weeks, while

German losses, especially in pilots, were

irreplaceable. Now the full weight of

the Allied tactical air forces fell on

the German army, making

it impossible to move

troops or supplies

on the ground without

drawing the unwelcome

attentions of freeroaming ghter bombers with their guns,

bombs, and rockets.

Air Force Historical Research Agency Photo

WRECKED THUNDERBOLT ON U.S.

AIRFIELD AT METZ, FRANCE AFTER

GERMAN ATTACK, JANUARY 1, 1945.

Page 21

Subject: EVENTS AND PEOPLE

- 19 -

By January 18, the Battle of the

Bulge was over. For Germany, the outcome was a double catastrophe: its last

offensive in the west was decisively

defeated on the ground, with the loss

of 100,000 men and 600 tanks, and the

Luftwaffe was nished as an effective

ghting force at a time when Allied

air power had never been greater. With

Russian armies advancing into Germany

from the east and British and American

armies advancing toward the Rhine from

the west, the outlook for the Third

Reich was bleak.

To the Rhine--and beyond

In February, the western Allies

started their push toward the Rhine.

Their goal was to drive the German

armies back into Germany and encircle

them. To achieve this, forces under

Montgomery pushed toward the southeast,

while the U.S. Ninth Army drove northeast. To slow the Allied advance north

of the Rhine, the Germans had ooded

the Ruhr valley (the gateway to the

industrial heart of the Reich), but by

February 23 the waters had subsided.

American armies crossed the Ruhr into

Germany, while to the south, the Allies

pushed through the remnants of

the “West Wall” into west-central Germany. (The West Wall, also

known as the Siegfried Line, was

an array of concrete pillboxes and

antitank defenses stretching 300

miles from Basel to Cleves.)

On March 7, the Americans

achieved a major coup by capturing, intact, the Ludendorff bridge

over the Rhine at Remagen. Allied

troops and vehicles poured across

and soon established a solid

bridgehead east of the Rhine. Over

the next two weeks, U.S. forces

crossed the Rhine and built up

their bridgehead to solidify their position. In the last week of March, the

British crossed the Rhine at several

points north of the Ruhr.

Air Force Historical Research Agency Photo

Air Force Historical Research Agency Photo

EIGHT RAF SPITFIRES ON PATROL.

OUT WITH THE OLD, IN WITH

THE NEW: THE USAAF OCCUPIES A

GERMAN AIRBASE AT FRANKFURT.

Page 22

Subject: EVENTS AND PEOPLE

The situation as it was in the spring

of 1945...

These aggressive Allied moves in

March, supported by tactical and strategic air power, clinched the encirclement

of German Army Group B and opened the

way for the Allied drive eastward to the

Elbe River. On April 25, U.S. and Russian forces linked up at Torgau on the

Elbe, effectively splitting Germany in

two and ending organized German resistance. With the fall of Berlin to the

Russians and the suicide of Hitler on

April 30, control of the crumbling Reich

fell to the Führer’s chosen successor,

Admiral Doenitz. A cascade of regional

surrenders--in Italy, Holland, Denmark,

and Germany--culminated in the unconditional surrender of all German forces,

signed for Doenitz by General Alfred

Jodl, on May 7, 1945.

...and the flexible timeframe and

tactical situation in CFS3

While the tactical air campaign

in CFS3 is rooted in the historical

events described in this Handbook, as

a CFS3 pilot, you have more opportunity to inuence short- and long-term

events and outcomes than any pilot on

either side enjoyed between 1943 and

1945. Your own performance and persistence can alter the tactical situation

and the timeline at every major turning point in this long and grueling

struggle--in the pre-invasion battle

to control transport routes in north-

west France, in the Normandy campaign and

the Allied breakout, in the battle for

France, in the Battle of the Bulge, in

the ght for the Rhine and the Ruhr, and

in the nal run to victory or defeat.

Along the way you can increase your

advantage by earning the privilege of

ying advanced aircraft that would have

remained out of reach in a strictly historical scenario. While you may be able

to take advantage of assets, including

personal skill and advanced technology

to take lesser objectives or even the

enemy capital, one major aspect of the

tactical air war as it really happened

remains: No matter how good you and your

squadmates are, no matter how awesome

your aircraft and weapons may be, the

grim realities of your job as a tactical

pilot never change. Flying at low altitude over masses of enemy troops, guns,

and vehicles leaves no room for romantic illusions about the glamour of war.

Danger is ever-present, and glory is hard

to come by.

The Nighttime Air War

Adds Extra Dangers

“In 1942 I flew 40 missions for the RAF. Piloting

a Wellington bomber on

night missions was the most

hair-raising duty I ever

did. Everyone was trying

to put you out of action-enemy night fighters,

antiaircraft guns, searchlights, mid-air collisions,

and weather all teamed up

to make it miserable and

hazardous.

In 1943 I transferred

to the USAAF, flying 48

night missions in P-61

Black Widows. To locate

and destroy targets such

as trains, vehicles, and

airfields, we would enter

enemy territory at low

altitude--200 to 500 feet.

We used radar and the radio

altimeter to avoid obstacles and the terrain, and

followed the rail lines and

highways until sighting a

target, which was difficult unless the moon was

out. Then we would use our

bombs, cannon, and machine

guns.”

--Veteran combat pilot

and CFS3 historical advisor

Al Jones

- 20 -

Page 23

Subject: LEADERS IN THE TACTICAL AIR WAR

Key Players in the Tactical Air War: The CFS3 Hall of Fame

The tactical air war didn’t grab a

lot of headlines, and didn’t produce many

aces. Like the foot soldiers who formed

the other side of the air-ground team,

tactical pilots had a rough job to do,

and faced many dangers without much

chance of winning individual fame. For

that reason this “Hall of Fame” focuses

primarily on leaders of the tactical air

war, individuals who formulated doctrine on the use of tactical air power

and then put that doctrine into practice

in the air over Europe. The pilots who

translated doctrine into combat reality

are represented by our three historical advisors, men who stepped up to the

dangerous job of teaming with the guys

on the ground during the momentous events

of WWII, and then returned to their

lives as veterans who put those events

behind them.

About Leadership and

Pilot Initiative

A look at the leaders on both sides

who were instrumental in forming tactical

air doctrine in WWII reveals an interesting difference of approach, a difference with important implications for the

pilots who had to transform doctrine into

ordnance on the battleeld.

Germany took an early lead in developing the collaboration of air and ground

forces, and used the Spanish Civil War of

1936-1939 as a proving ground for new

weapons and techniques. This experience

paved the way for the

to 1940, when Germany stunned the world

by rapidly defeating Poland, France,

Belgium, Holland, and Denmark with coordinated attacks by armor, air power,

and mobile infantry. Throughout the war

Germany used this combination of forces

wherever possible. However, the Luftwaffe

leadership failed to rene its use of

air power, while the Allies embraced new

technologies and techniques that made

their tactical air forces into sharper,

more focused and effective weapons.

This failure put German pilots at

a double disadvantage. As Allied material superiority grew to an overwhelming

ood of military power directed against

Germany, the problem was compounded by

leaders preoccupied with maintaining

favor and casting blame instead of assuming responsibility for the success of

their pilots.

What made the Luftwaffe a formidable weapon as the war went on was the

dedication, skill, and perseverance of

its pilots. The often murky nature of

combat in the air low over the battleeld

always demanded a high degree of pilot

initiative for all nationalities, but

for German pilots that initiative took

on greater importance, given decreasing

direction from above.

Blitzkrieg

of 1939

- 21 -

Page 24

Subject: LEADERS IN THE TACTICAL AIR WAR

- 22 -

dismay of naval of cers who saw

the battleship as the ultimate

expression of military power,

Mitchell led Army bombers in

trials that sank a variety of

vessels, including a submarine, a destroyer, a cruiser,

and nally the captured German

battleship Ostfriesland. This

earned him enemies in high

places, as did his criticism of

government policies and de ance

of the military leadership.

In 1924, after a visit to

Japan, Mitchell wrote a report

that warned of Japanese ambitions

in the Paci c. He foresaw a war

with Japan that he said would

begin with an aerial attack on

American naval and air facilities

at Pearl Harbor, starting with

bombardment of the base on Ford

Island at 7:30 a.m., to be followed by an attack on Clark Field

in the Philippines.

In 1925, after accusing Army leadership of criminal negligence in the

loss of the airship Shenandoah, he was

court-martialed for insubordination and

resigned from the service. Mitchell died

in 1936, before he could see air power

triumphant in World War II. In 1941 Lee

Atwood, vice president and chief engineer of North American Aviation, proposed naming the new B-25 medium bomber

“Billy” Mitchell was an air power

pioneer, visionary, and evangelist. He

was also an irritant to American military commanders who lacked his vision

and enthusiasm. As commander of American

combat squadrons in World War I Mitchell

was one of the rst to show what the airplane could do to advance the war on the

ground, proving it to be a potent weapon

against enemy positions and surface targets on land or sea.

Mitchell joined the U.S. Army

in 1898 and showed an early interest

in technology, rst as a telegrapher

in the Signal Corps. When the Signal

Corps formed its Aeronautical Division,

Mitchell bought his own ight lessons.

By 1913 he informed a congressional committee that America was falling behind

in what he saw as a vital new technology. In 1917 he was sent to observe air

operations in Europe, and, with America’s

entry into the war, he was soon in charge

of ghting units and promoted to Brigadier General.

In September 1918 Mitchell planned

and led a bombing attack on the Germanheld St.-Mihiel salient in which almost

1,500 aircraft dropped their bombs on

German positions in coordination with

an infantry assault on the ground.

After the war, Mitchell tirelessly

advocated an independent Air Service and

sought every opportunity to demonstrate

what air power could do. In 1921, to the

GENERAL WILLIAM “BILLY” MITCHELL (1879-1936)

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

“BILLY” MITCHELL: IN THE 1920S

HE SHOWED THE SKEPTICS WHAT

AIR POWER COULD DO.

Page 25

Subject: LEADERS IN THE TACTICAL AIR WAR

- 23 -

in honor of Billy Mitchell, and although

it was unusual to name aircraft for real

people living or dead, the Army Air Corps

agreed. No one could have devised a more

appropriate honor, as the B-25 Mitchell

went on to prove its worth as a potent

weapon in all theaters of operation, from

Doolittle’s Tokyo Raid in 1942 through

the end of the air war in Europe.

Although his court-martial was never

reversed, Mitchell was honored posthumously in 1946 with a unique Special

Congressional Medal of Honor featuring a likeness of Mitchell in aviator’s

helmet and goggles.

Billy Mitchell

on the Tasks of

Tactical Air Power

Billy Mitchell’s definition of the air objectives

of the St.-Mihiel offensive

was one of the first systematic statements about

the role of what would

become tactical air power:

“We had three

tasks to accomplish:

one, to provide

accurate information

for the infantry and

adjustment of fire

for the artillery of

the ground troops;

second, to hold off

the enemy air forces

from interfering

with either our air

or ground troops;

and third, to bomb

the back areas so as

to stop the supplies

from the enemy and

hold up any movement

along the roads.”

--Alan F. Wilt,

Coming of Age: XIX TAC’s

Roles During the 1944

Dash Across France

.S

. Air

F

orce

Mu

seum

hoto p

r

ovided c

ourtesy

.S

. Air

F

orce

Mu

seum

“Billy” Mitchell’s special

Congressional Medal

of Honor, awarded

posthumously in 1946.

Page 26

Subject: LEADERS IN THE TACTICAL AIR WAR

- 24 -

GENERAL ELWOOD “PETE” QUESADA (1904-1993)

ters in Normandy on D-Day+1,

and moved it constantly to keep

up with the rapidly advancing

front lines.

Under Quesada’s leadership, IX TAC provided close

air support for the American

invasion forces. He was quick

to appreciate the command-andcontrol possibilities of radar

and radio coordination, and

originated the idea of enhancing air-ground cooperation by

sending Army Air Force liaison of cers

with ground forces, often in the lead

tank of a moving column. One of his biggest challenges was to convince “seat

of the pants” pilots to put their trust

in “newfangled gadgets.” His leadership

in directing IX TAC’s air campaign, his

support of General Omar Bradley’s First

Army after the breakout in Normandy, and

his leadership of American tactical air

power in the Battle of the Bulge were

major contributions to the Allied success

in Europe.

Promoted to the rank of Lt. General

in 1947, Quesada retired from the Air

Force in 1951 and was named rst head

of the Federal Aviation Administration

in 1959. He died in 1993.

A year after General Billy Mitchell

was ejected from the U.S. Army Air Corps,

21-year-old Elwood “Pete” Quesada won his

wings as a ying cadet. In WWII he would

gain fame as head of the IX Tactical Air

Command, a role in which he was both an

active leader and an innovator, adopting new technologies to re ne and perfect

air-ground teamwork.

The son of a Spanish businessman

and an Irish-American mother, Quesada

was born in Washington, D.C. in 1904.

As part of the crew of an Army Fokker

monoplane called the Question Mark, he

helped set a sustained ight record in

1929 by remaining aloft for over 150

hours, during which the plane was refueled in the air 42 times. In 1934 he

was chief pilot on the Army’s New YorkCleveland airmail route.

Quesada’s career moved rapidly once

WWII began. Promoted to Brigadier General

at the end of 1942, within months he led

the XII Fighter Command in North Africa

and ew combat missions in Tunisia,

Sicily, Corsica, and Italy.

In 1943 he was sent to England as

head of the IX Fighter Command to prepare for the Allied invasion of Normandy.

His primary responsibility was to teach

what he had learned in tactical operations in Italy. At the end of 1943, he

was put in charge of the IX Tactical

Air Command and directed its operations

in the eld. He set up his headquar-

Air Force Historical Research Agency Photo

General Elwood “Pete” Quesada, head of

the U.S. IX Tactical Air Command.

Page 27

Subject: LEADERS IN THE TACTICAL AIR WAR

- 25 -

GENERAL OTTO PAUL WEYLAND (1902-1979)

for a pounding by the tactical air commands. The port of Brest fell in part

due to the relentless assault of XIX TAC

on shipping and port facilities, and by

the end of December, Weyland’s ghter

bombers were attacking the enemy near

the German border.

Patton called Weyland “the best

damn general in the Air Corps,” and

offered this commendation for the

unwavering support of XIX TAC:

The superior efficiency and cooperation afforded this army by the

forces under your command is the

best example of the combined use of

air and ground troops I have ever

witnessed.

Due to the tireless efforts of

your flyers, large numbers of hostile vehicles and troop concentrations ahead of our advancing columns

have been harassed or obliterated.

The information passed directly to

the head of the columns from the air

has saved time and lives.

I am voicing the opinion of all

the officers and men in this army

when I express to you our admiration

and appreciation of your magnificent

efforts.

As head of the XIX Tactical Air

Command from 1944 to 1945, O.P. “Opie”

Weyland provided the perfect partner in

the air to George S. Patton’s hard-driving Third Army on the ground. Together

they made history during Patton’s dash

across France and into Germany after

the Normandy invasion. This was the high

point in a long and distinguished career

that began with a commission in the U.S.

Army Air Service in 1923 and culminated

with Weyland’s appointment as commanding

general of the United States Air Force’s

Tactical Air Command in 1954.

Weyland arrived in Europe as a new

brigadier general in November, 1943, and

four months later was assigned to head

XIX TAC. Under his leadership XIX TAC

wrote new chapters on the possibilities

of air-ground teamwork, becoming a fastmoving and hard-hitting force that kept

pace with and protected Patton’s armored

columns and lines of supply as the Third

army surged forward, at times covering

20 miles a day. Once the Allied armies

managed to break out of the invasion

beachhead, XIX TAC set records for mobility, moving its headquarters ve times

during the month of August.

In conjunction with General “Pete”

Quesada’s IX TAC, Weyland’s XIX TAC

pilots ew three, four, or even ve missions a day, bombarding road and rail

transport and bridges. German tanks,

trucks, guns, and troops all came in

Air Force Historical Research Agency Photo

DYNAMIC DUO: GENERAL O.P.

WEYLAND (RIGHT) WITH GENERAL

GEORGE S. PATTON.

Page 28

Subject: LEADERS IN THE TACTICAL AIR WAR

- 26 -

SIR TRAFFORD LEIGH-MALLORY (1892-1944)

In November 1944 Leigh-Mallory

was assigned to head Allied air

forces in Southeast Asia, but died

in a plane crash before he could

assume command.

Trafford Leigh-Mallory fought on

the ground in WWI until 1916, when he

transferred to the Royal Flying Corps.

By 1918 he commanded a squadron, and

by 1938 had risen to the rank of Air

Vice-Marshal. During the Battle of

Britain from 1940 to 1941, he led RAF

Fighter Command’s No. 12 Group in the

English Midlands.

In 1942 Leigh-Mallory became head

of RAF Fighter Command, and in 1943 he

was knighted and made Chief Air Marshal.

In 1944 he was named commander-in-chief

of the U.S. and British units that formed

the Allied Expeditionary Air Forces,

which included the U.S. Ninth Air Force

and the British Second Tactical Air

Force. In this role he was responsible

for the air component of air-ground

teamwork in the invasion of Europe. One

of his major achievements in this period

was the “Transportation Plan,” to devastate rail transport and facilities vital

to the German resupply effort. His collaboration with Allied leaders, including Bradley and Montgomery, provided some

high points in the Anglo-American military alliance.

Air Force Historical Research Agency Photo

TRAFFORD LEIGH-MALLORY

BRIEFS RAF PILOTS IN FRANCE,

SEPTEMBER 1944.

Page 29

Subject: LEADERS IN THE TACTICAL AIR WAR

- 27 -

SIR ARTHUR “MARY” CONINGHAM (1895-1948)

Arthur “Mary” Coningham was born

in Australia and educated in New Zealand.

This New Zealand connection earned him

the nickname “Maori,” which over the

years became “Mary.” He served with the

New Zealand Expeditionary Force in WWI

before transferring to the Royal Flying

Corps in 1916. Assigned to a squadron in

1917, by the end of the war he had scored

14 aerial victories and won numerous

decorations for gallantry.

Early in WWII Coningham led RAF

forces in support of Montgomery’s campaign in North Africa, and developed an

approach to air power ultimately adopted

by Eisenhower in Europe. He called for

the concentration of air power against

key objectives, under the command of

air of cers. His most successful application of this doctrine came in 1944 when,

as commander of the RAF’s Second Tactical

Air Force (2TAF) and the Advanced Allied

Expeditionary Air Force (AAEAF), he

unleashed 2TAF on German forces from

Normandy to the Battle of the Bulge and

beyond. In cooperation with the U.S. IX

and XIX TAC, Coningham’s airmen made

signi cant contributions to the success

of the Normandy invasion and Allied

victory.

In 1945 Coningham took

charge of the RAF Flying

Training Command. He retired

in 1947; the following year his

aircraft disappeared while on

a commercial ight to Bermuda.

Sir Arthur “Mary” Coningham.

Imperial War Museum Photo

Page 30

Subject: LEADERS IN THE TACTICAL AIR WAR

- 28 -

REICHSMARSCHALL HERMANN GÖRING (1893-1946)

With the collapse of the Reich,

Göring surrendered to American forces.

Ever ingratiating when it served his

purpose, he sang the praises of the

USAAF, while ignoring the dogged sixyear contribution of the RAF:

“The Allies must thank the

American Air Force for winning the

war. If it were not for the American

Air Force the invasion would not

have succeeded. Even if it had succeeded it could not have advanced

without the American Air Force.

Further, without the American Air

Force Von Rundstedt would not have

been stopped in the Ardennes. And

who knows but that the war would

still be going on.”

--Hermann Göring,

in Thomas A. Hughes,

Over Lord:

General Pete Quesada and the

Triumph of Tactical Air Power

in World War II

Göring’s career as an airman got

off to an impressive start in the First

World War, in which he amassed 22 aerial

victories and won his nation’s highest

decoration, the Pour le Mérite, popularly

called the “Blue Max.” He nished the

war in charge of the squadron formerly

led by WWI’s ace of aces, Manfred von

Richthofen, the “Red Baron.”

In postwar Germany Göring became

second only to Hitler in the hierarchy

of the Third Reich, and in 1935 was put

in charge of the resurgent Luftwaffe.

Early successes in Spain and during the

Blitzkrieg of 1939 to 1940 showed the

world what air power could do, but his

leadership had reached its pinnacle.

In the Luftwaffe, Göring had created

a magni cent ghting machine, but squandered it by refusing to adapt to changing circumstances. His management of the

Battle of Britain during 1940 and 1941

was a debacle of miscalculation for which

he blamed his own pilots. This pattern

continued as Germany’s military situation deteriorated and pilots came to view

the grandiose Reichsmarschall with contempt. Given this leadership vacuum at

the top, the responsibility for using the

air weapon with any degree of effectiveness fell to the eld commanders who had

to lead from the cockpit, and pilots who

were willing to push themselves to the

limit to achieve some success against

the enemy.

Hermann Göring.

Bettmann/Corbis

Page 31

Subject: LEADERS IN THE TACTICAL AIR WAR

- 29 -

FELDMARSCHALL WOLFRAM VON RICHTHOFEN (1895-1945)

A cousin of Germany’s “Red Baron,”

Wolfram von Richthofen became an early

exponent and practitioner of close air

support in Europe in the 1930s and in

WWII. He served in the Imperial army

until 1917, and then transferred to

the Flying Service. He won eight victories as a pilot in Jagdgeschwader

Richthofen, the ghter squadron named

for his famous cousin. After the war

he earned an engineering doctorate, and

returned to the newly reformed Luftwaffe

as a technical expert in 1933.

In 1936, von Richthofen became commander of a small air force sent to

Spain on behalf of the Fascists under

Francisco Franco. In 1938 he was sent

back to Spain in charge of the much

larger Legion Kondor, a force that tested

dive-bombing and other close air support

techniques that would later be part of

Germany’s Blitzkrieg, the “Lightning War”

of mobile forces.

Once WWII began, von Richthofen

served in the Polish, French, Balkan,

Greek, and Russian campaigns as commander of Fliegerkorps VIII. In this role

he became a foremost promoter and practitioner of close air support using the

dive-bombing capabilities of the Junkers

Ju 87 Stuka.

During the siege of Stalingrad von

Richthofen was tasked with supplying

the encircled Sixth Army. By 1942 he rose

to command the nearly 2,000 aircraft of

a Luft otte (“Air Fleet”), and, early

in 1943, Hitler made him the youngest eld marshal in the German army.

He assumed command of Luft otte 2 in

the Mediterranean, but in 1944 was diagnosed with a brain tumor, and ended his

active service late that year. He died in

July, 1945.

Wolfram von Richthofen.