Page 1

GHOST Contents 1

Page 2

2 GHOST Contents

Manual written by Dominick J. Fontana

© Harman International Industries Ltd. 1999

All rights reserved

Parts of the design of this product may be protected by worldwide patents.

Part No. ZM0168

Issue 5

Soundcraft is a trading division of Harman International Industries Ltd.

Information in this manual is subject to change without notice and does not represent a commitment on the part of the vendor. Soundcraft shall not be liable for

loss or damage whatsoever arising from the use of information or any error contained in this manual.

No part of this manual may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, electrical, mechanical, optical,

chemical, including photocopying and recording, for any purpose without the

express written permission of Soundcraft.

It is recommended that all maintenance and service on the product should be carried out by Soundcraft or its authorised agents. Soundcraft cannot accept any liability whatsoever for any loss or damage caused by service, maintenance or repair

by unauthorised personnel.

Harman International Industries Limited.

Cranborne House,

Cranborne Road,

Cranborne Industrial Estate,

Potters Bar,

Herts.,

EN6 3JN

UK.

Tel: 01707 665000

Fax: 01707 660482

¨

Page 3

GHOST Contents i

CCoonntteennttss

1 Introduction 1.1

Features of Ghost and Ghost LE 1.3

2 Installation 2.1

Optional Meterbridge 2.3

User Modifications to Ghost 2.4

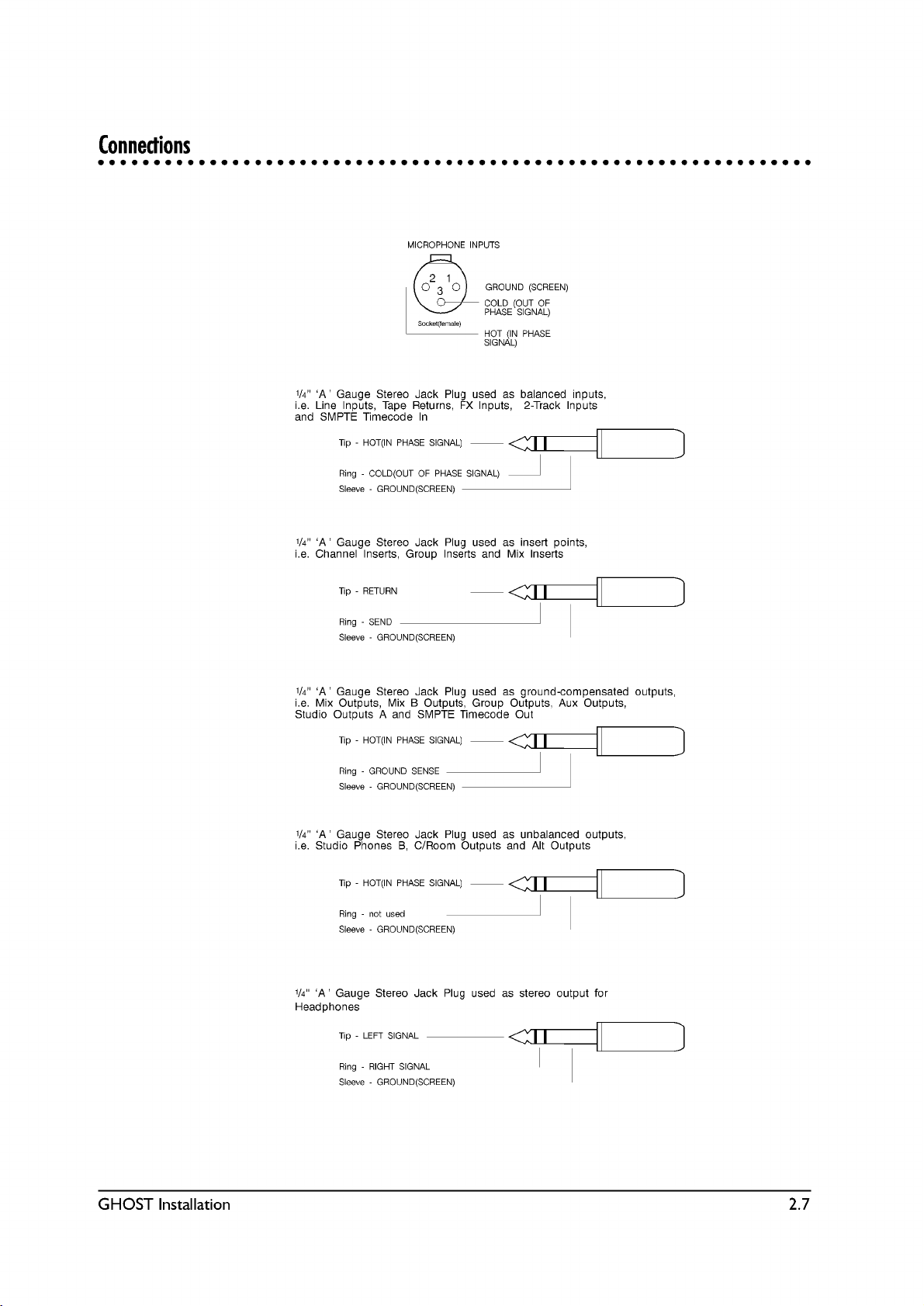

Connections 2.7

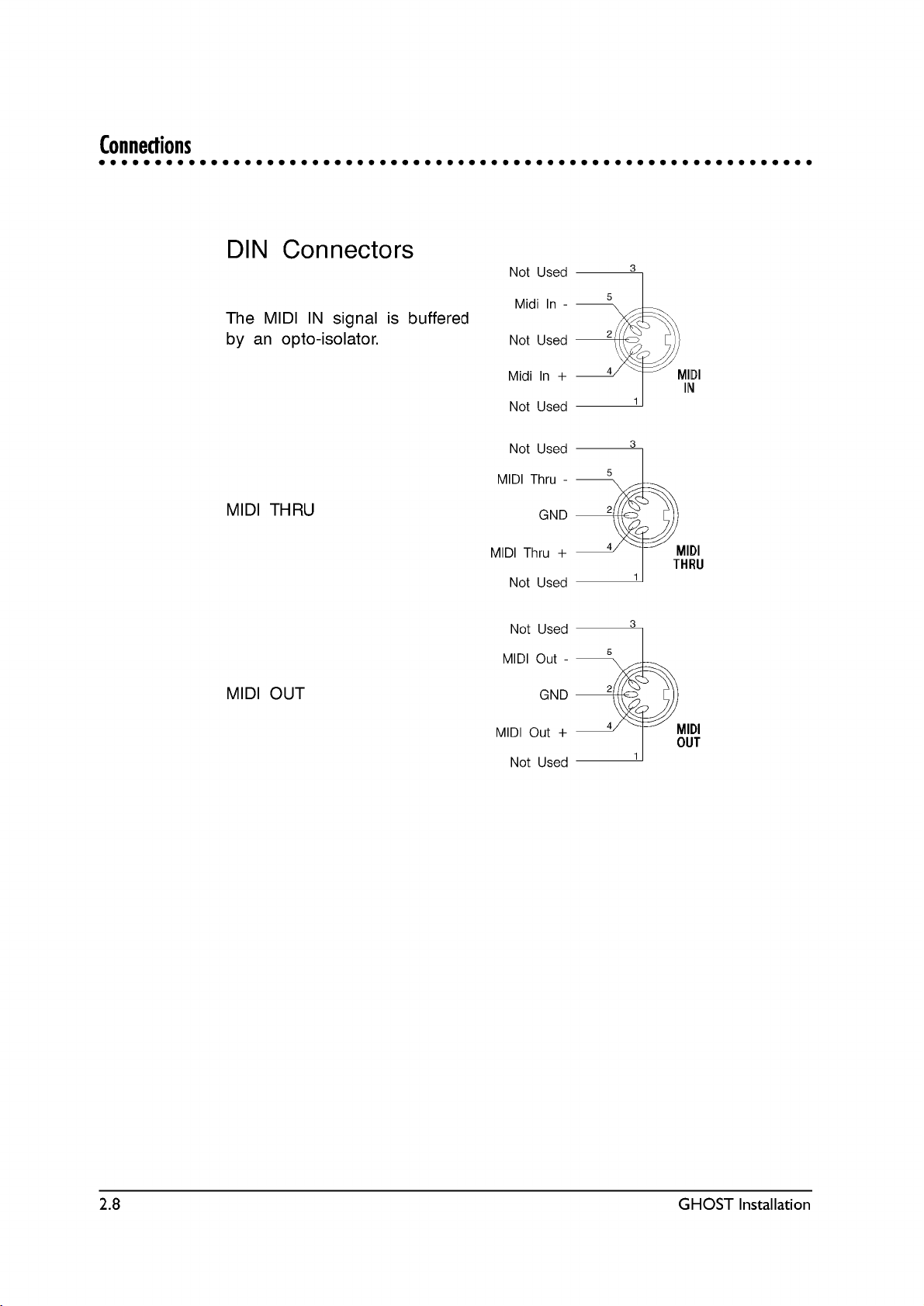

Din Connectors 2.8

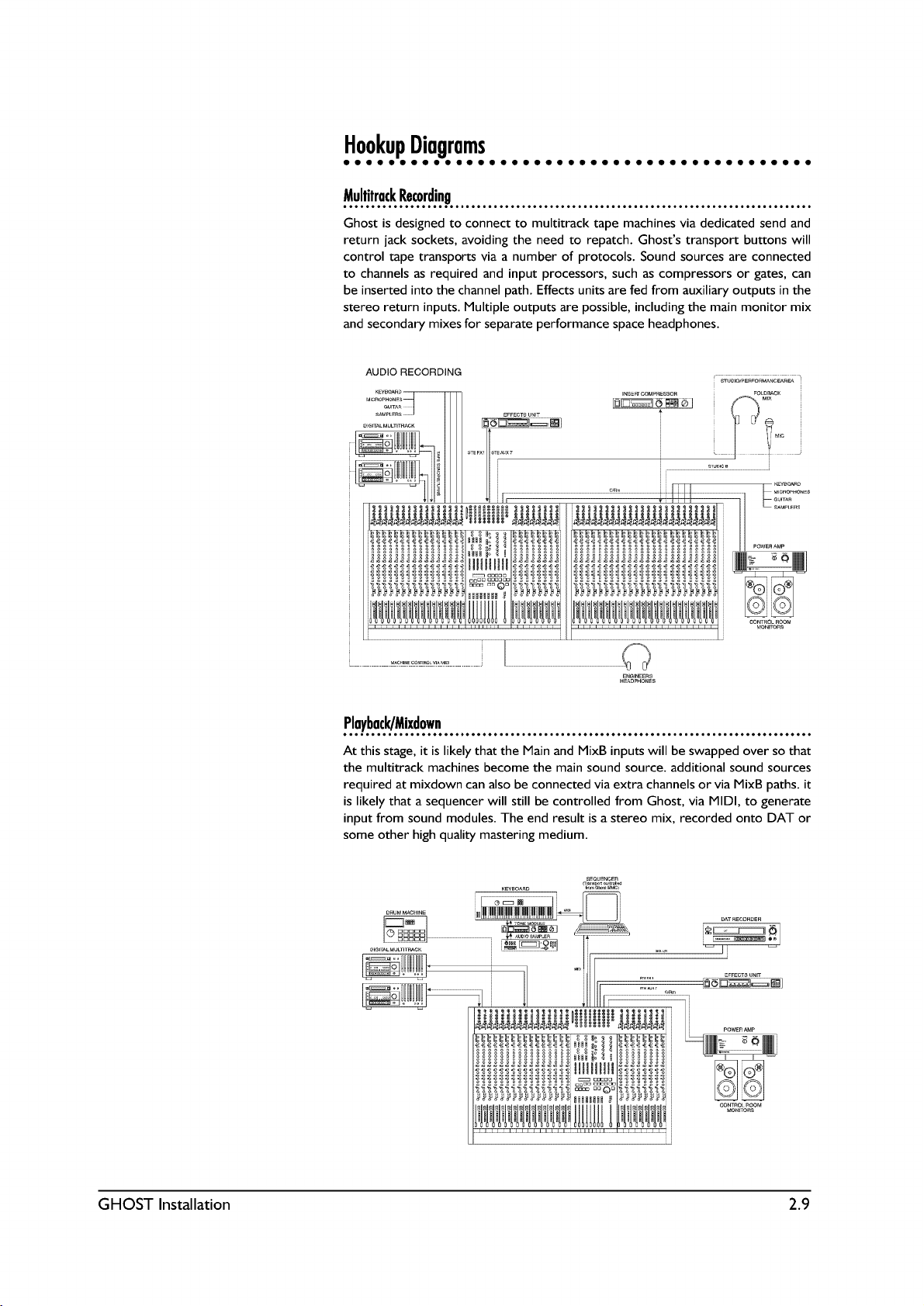

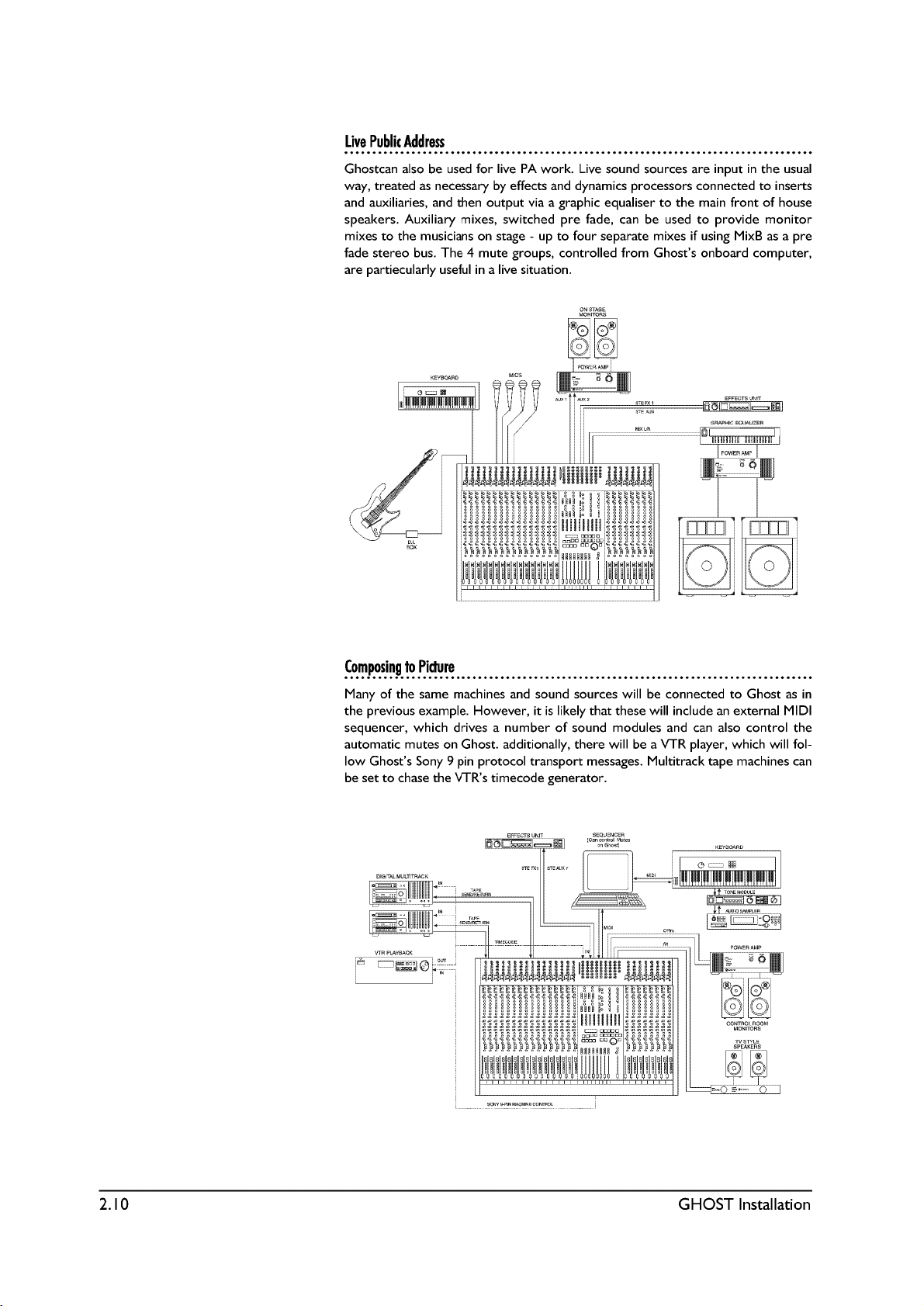

Hookup Diagrams 2.9

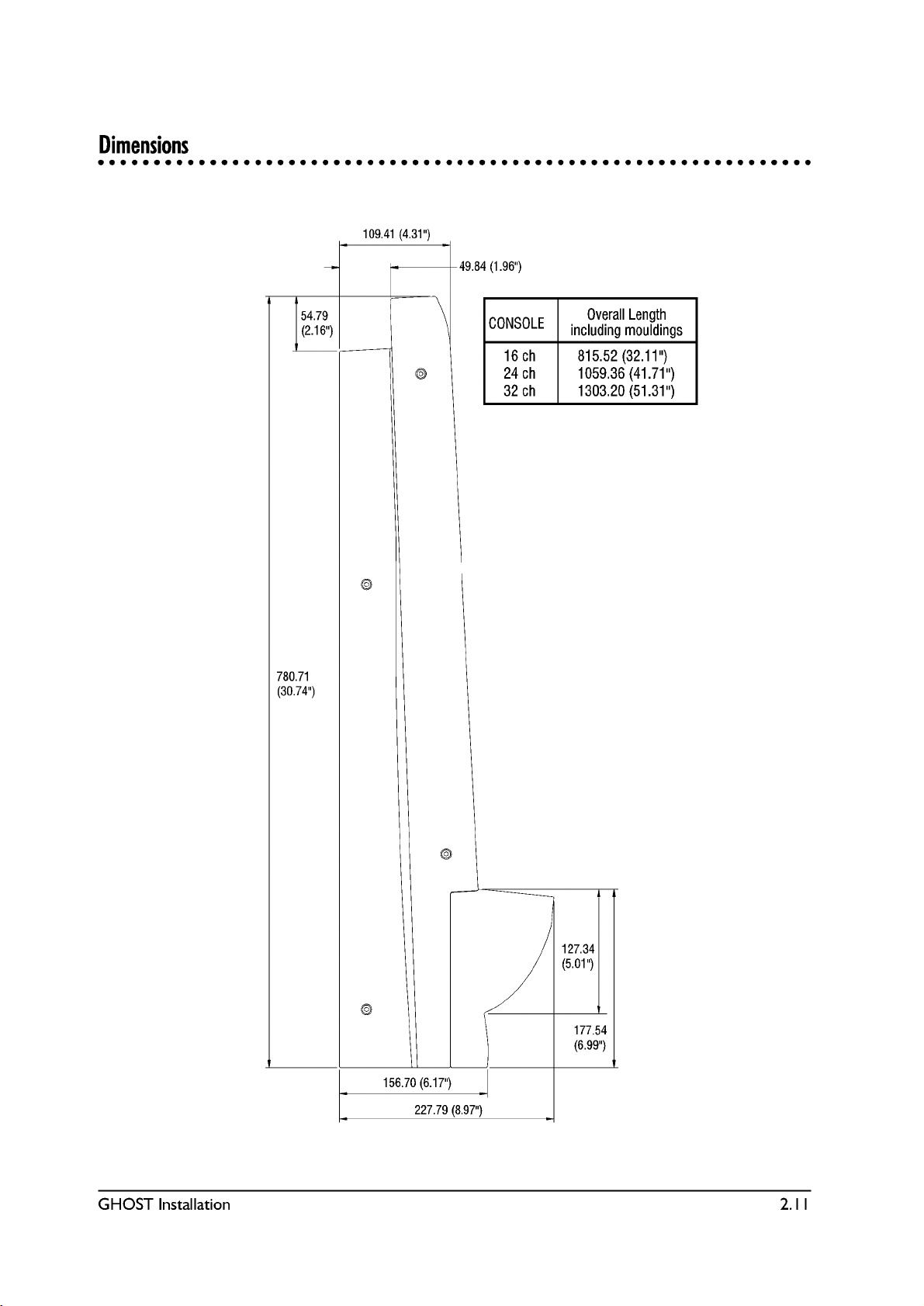

Dimensions 2.11

3 Quick Start Guide 3.1

Control Room Monitoring 3.6

Studio Monitoring 3.7

Adding Effects and Processors 3.9

4 Block Diagram 4.12

Block Diagram Explanation 4.3

Signal Flow 4.6

Overview of Main Signal Paths 4.12

5 Back and Rear Panel Description 5.1

Back Panel 5.2

6 Functional Description 6.1

The Mono Input Module 6.2

Output and Master section 6.15

7 Tutorial 7.1

Multitrack Tutorial 7.2

Studio Monitoring 7.8

GGHHOOSSTT

Page 4

ii GHOST Contents

8 Application Notes 8.1

Overview 8.2

9 CPU Application Guide 9.1

(NOT APPLICABLE TO GHOST LE)

10 Troubleshooting 10.1

General 10.2

Troubleshooting Chart 10.3

11 Specifications 11.1

12 Glossary 12.1

Appendix A A.1

Notes for Machine Control A.2

Appendix B B.1

MIDI Controller Numbers B.2

Appendix C C.1

MIDI Note Numbers to Mutes Conversion Chart C.2

MIDI Note Numbers to Expander Mutes Conversion Chart C.3

MIDI Note Numbers by Octave C.4

Appendix D D.1

MIDI Implementation Chart D.2

Appendix E E.1

Upgrading the Software E.2

Page 5

GHOST Introduction 1.1

GGHHOOSSTT

IInnttrroodduuccttiioonn

1

Page 6

1.2 GHOST Introduction

IInnttrroodduuccttiioonn

Thank you for purchasing the Soundcraft Ghost Music Production console. It has

been designed to give you many years of trouble-free service. Please read this

entire guide before using the console and then retain it for future reference. The

terms console, mixer, and board are used interchangeably throughout this guide.

This guide covers two versions of the Ghost console, namely Ghost (with a CPU

section containing a Timecode reader/generator, MIDI Machine Control, MIDI

Mute Automation, and MIDI Controller Faders) and Ghost LE (with no CPU sec-

tion). Both Ghost and Ghost LE are identical, except that Ghost LE does not have

a CPU section above the Group faders. The top panel views in this guide some-

times show Ghost and sometimes Ghost LE. Except for the sections dealing with

the CPU, which applies to Ghost only, everything else in this guide applies to both

Ghost and Ghost LE.

This guide is composed of a Table of Contents, 12 chapters, 5 appendices, and an

index. Following is an overview of the guide:

Chapter Title Description

- Table of Contents Allows you to find broad topics easily.

1 Introduction What you are currently reading.

Contains basic information about Ghost.

2 Installation Contains information about installing

Ghost and modifying some of its default

settings. Also has detailed hookup and

connections diagrams.

3 Quick Start Allows you to quickly get up and running

Guide with Ghost.

4 Block Diagram Contains a standard pictorial block diagram,

as well as a plain English signal flow explana

tion of that diagram.

5 Back and Rear Contains a detailed description of all of

Panel Description Ghosts back and rear

panel jacks.

6 Functional Contains a detailed description of all of

Description Ghosts controls.

7 Tutorial Explains in detail how to use Ghost for

tracking, overdubbing, monitoring, adding

effects and processors, punching in/out,

bouncing tracks, and mixing down.

8 Application Explains some of Ghosts more advanced

Notes uses.

9 CPU Application Explains how to use the CPU section of

Guide Ghost. (Not Applicable to Ghost LE.)

Page 7

GHOST Introduction 1.3

10 Troubleshooting Contains some common problems, causes,

and solutions.

11 Specifications Lists complete specifications of Ghost.

12 Glossary Contains some common audio terms and

their definitions.

- Appendices Contain information on MIDI Machine

A through E: Control, Controller Numbers, Note

Numbers, MIDI Implementation Chart, and

upgrading Ghosts software.

- Index Contains a detailed index, which allows

you to find a specific topic.

It is suggested that you read this entire manual. If youre the type that doesnt like

to read manuals, then we suggest the following:

For Advanced Users: Read the Introduction (up to "The Basics of In-Line

Consoles"), Installation, Block Diagram, Back and Rear Panel Description, and

Functional Description chapters, and the Appendices.

For Intermediate Users: Read the Introduction (up to "The Basics of In-Line

Consoles"), Installation, Quick Start Guide, Block Diagram, Back and Rear Panel

Description, Functional Description, and Application Notes chapters, and the

Appendices.

For Beginning Users: You should read the entire manual, but at the very least you

should read the entire Introduction, Installation, Block Diagram, Back and Rear

Panel Description, Functional Description, Tutorial, Application Notes chapters,

and the Appendices. Refer to the Troubleshooting and Glossary chapters, as need-

ed.

For All Users: If you have the Ghost console with the CPU (not Ghost LE), then

you should also read the CPU Application Guide chapter.

Page 8

1.4 GHOST Introduction

FFeeaattuurreess ooff GGhhoosstt aanndd GGhhoosstt LLEE

Ghost is a professional 8-bus mixing console, primarily designed for multitrack

recording and music production applications. It is an In-Line console, having a main

input path and a secondary Mix B input path on each channel. This doubles the

number of inputs at mixdown, yet the console remains compact. Following are

some of Ghosts features:

l Soundcrafts ProMic ultra-low-noise mic preamp, with +60dBu input sensi-

tivity, is included on every channel.

l Every channel features a mic input, a line input, individually switched

phatom power, mic/line switch, phase reverse, and 100Hz Low-Cut Filter.

l Multi-busing on every channel allows Direct Outs on each channel to also

be used as Group Outs, allowing you to send a signal from any channel to

any of 32 tape tracks (24 tape tracks with 24 channel Ghost).

l Powerful 4-band "British" EQ, featuring high/low shelving EQ and two fully-

parametric mid EQs, with continuously variable Q (bandwidth) control and

EQ In/Out switch.

l 6 mono (4 usable at once per channel) and 2 stereo auxiliary sends. Sends

1/2 are switchable as a pair between pre-fader and post-fader. Sends 3/4

can be routed as a pair to Sends 5/6.

l 100mm faders and inserts for channels, groups, and main L/R mix.

l Variable brightness Signal Present LED for each channel.

l Peak LED for each channel.

l Automated/Manual Mutes (Cut) for each channel. (Mutes cannot be auto-

mated on Ghost LE.)

l Solo (either PFL or Solo-in-Place) for each channel.

l Mix B section on each channel features a line input, source select (tape or

channel), rotary fader, pan, PFL Solo, and automated/manual Mutes (Cut).

(Mutes cannot be automated on Ghost LE.)

l Tape Input Trim pot for the Mix B line input.

l High/Low shelving EQ and Auxs 3/4 (5/6) may be switched into the Mix B

path.

l Reverse switch allows you to route the channel input to the Mix B path and

the Mix B input to the channel path.

l 8 Group buses with AFL solo and routing to the L/R bus.

l 4 stereo effects returns, each with PFL Solo and routing to the L/R bus or

any of the group buses.

l 2 separate Studio Foldback monitoring sections with AFL Solo.

l Control Room monitoring section with headphone jack, mono check, pro-

visions for two stereo line inputs (DAT deck, two-track deck, CD player,

etc.), and two sets of control room monitors.

l A 2-frequency oscillator.

l Talkback section with built-in mic.

l 8 Aux Send Master pots with AFL Solo.

Page 9

GHOST Introduction 1.5

l Mix B Master pot with provision for routing Mix B to the L/R bus.

l PFL/AFL Trim pot with Solo LED and Solo-in-place switch with LED.

l 12-segment vertical peak LED meters for the 8 Groups and for the Control

Room/Solo outputs.

l By using the channel inputs, Mix B inputs, and 4 stereo FX returns at mix-

down, you have a total of 56 inputs from the 24 channel Ghost and a total

of 72 inputs from the 32 channel Ghost.

l Optional 24 channel expander module is available.

l Optional meterbridge is available.

AAddddiittiioonnaall ffeeaattuurreess ooff GGhhoosstt ((NNoott FFoouunndd oonn GGhhoosstt LLEE))

l MIDI In/Out/Thru jacks.

l SMPTE timecode In/Out jacks and Sony 9-pin connector.

l SMPTE/MTC timecode reader/generator/converter.

l MIDI Machine Control transport control buttons with jog/shuttle wheel for

controlling external tape machines, video machines, hard disk recorders,

and MIDI sequencers.

l 4 mute groups.

l 128 snapshots for MIDI muting, which may be recalled manually, from

timecode, or from MIDI Program Change Messages.

l Dynamic Mute Automation (with an external MIDI sequencer).

l 4 MIDI Controller Faders for controlling external MIDI effects and other

MIDI parameters by transmitting MIDI Control Change data.

FFrraammee SSiizzeess && EExxppaannddeerr MMoodduullee

Ghost is available in two frames sizes:

l 24 Input Channels

l 32 Input Channels

There is also an optional 24 channel expander module available, which allows you

to expand Ghost to 48 channels or 56 channels. With the 4 stereo FX returns, this

will give you either 104 or 120 inputs at mixdown.

MMeetteerrbbrriiddggee

There is an optional meterbridge for each console size and for the expander mod-

ule. The meterbridge contains a vertical 12 segment peak LED meter for each

channel, which can be internally configured to show either the Mix B (tape) inputs

or the channel inputs. It also includes two

20-segment LED VU meters for the Control Room/Solo outputs.

PPoowweerr SSuuppppllyy

Use only the power supply that comes with the console and make sure it is config-

ured for the country you will be using it in.

Page 10

1.6 GHOST Introduction

CCoonnttaacctt IInnffoorrmmaattiioonn

You may write, phone, fax, or EMAIL Soundcraft at the following places:

In Europe:

Soundcraft Telephone: +44 (0) 1707 665000

Harman International Industries LTD. FAX: +44 (0) 1707 660742

Cranborne House, Cranborne Rd., EMAIL: info@soundcraft.co.uk

Potters Bar, Herts, EN6 3JN, UK.

In the United States:

Soundcraft USA Telephone: 1(615) 360-0471

1449 Donelson Pike FAX: 1(615) 360-0273

Nashville, Tennessee 37217

TThhee BBaassiiccss ooff IInn--LLiinnee CCoonnssoolleess

When using a console for traditional multitrack recording, it is necessary to be able

to record the consoles channel inputs to tape, while at the same time monitoring

previously recorded tape tracks. When youre finished recording, you must be

able to play the finished multitrack master tape through the console, make adjust-

ments to the tape tracks, and then record your mix to your 2-track mixdown

deck. This means that the outputs of the mixer (group outs or direct outs) have to

be connected to the inputs of the multitrack deck for recording purposes, while at

the same time the outputs of the multitrack deck have to be connected to the

inputs of the mixer (tape returns) for monitoring and mixdown purposes.

However, the requirements for simply monitoring tape tracks while overdubbing

are different than what is needed when mixing down those tracks.

Before in-line consoles, split console designs were used. Since this is not a primer

on split consoles, just the basics will be given here. With split consoles the channel

strips and the tape returns were split, with the channels on the left side and the

tape returns located above the group masters on the right side of the board. While

tracking and overdubbing, the channel outputs were routed to the multitrack

inputs and the multitrack outputs were routed to the tape returns. The channels

were used for recording and the tape returns were simply used to monitor previ-

ously recorded tape tracks. This meant that if you wanted to monitor 32 tape

tracks, you had to have 32 separate tape returns located apart from the channel

strips. And those returns might have only provided level and pan controls for each

track. Since the tape returns didnt offer all the features of the channel strip (such

as EQ and Aux Sends), and didnt provide a way to route the tape tracks to the

mixdown deck, when it came time for mixdown, the multitrack outputs had to be

repatched from the tape returns to the channel strip inputs. This allowed you to

use all of the features of the channel strip and to route the tape tracks to the

2-track deck during mixdown. While this is an oversimplification of the process, it

is sufficient to illustrate the point.

The drawbacks of a split console design are as follows: the console usually has to

be very wide to accommodate all the tape returns; as the number of tape returns

increases on a console, so do the number of channel strips, so if you need 32 tape

returns, you might have to buy a console with 64 or more channel strips; you have

to repatch when you want to mixdown and then repatch again when you want to

track and overdub; while mixing down, the tape returns are unused; and split con-

sole designs cost more than an equivalent in-line design.

An in-line console solves these problems, while remaining compact and affordable.

With todays digital multitrack recorders, hard disk recorders, and MIDI

sequencers, many studios have 24 or more tracks (whether tape, disk, or

sequenced) that need to be monitored, yet not as many channel inputs are needed

for recording purposes. With an in-line console, the tape return controls are physi-

cally located right in the channel strip, or "in-line" with the channel strip, hence,

Page 11

GHOST Introduction 1.7

the name. You have as many tape returns as you have channel strips, yet no extra

width is added to the console regardless of the number of returns, although there

is a slight increase in the depth of the console.

As mentioned, Ghost is an in-line console. There are 2 separate inputs for each

channel strip. The main channel input is called "Channel" and the tape return input

is called "Mix B." Note that you can connect any line level source to Mix B; it does-

nt have to be the output of a tape deck. Normally, whatever is connected to the

mic or line input on the rear panel is routed to the channel strip and you use the

channel strips controls to process that input. And whatever is connected to the

Mix B/Tape Ret jack on the rear panel is routed to the Mix B section, located with-

in the same channel strip, and you use Mix Bs controls to process the Mix B input

separately from the channel input.

Generally speaking, while recording basic tracks and overdubbing, you connect the

sources you want to record to the channel inputs and you connect the sources

you want to monitor to the Mix B inputs. Youll usually want to monitor previously

recorded tape tracks, hard disk tracks, and MIDI sequenced tracks. At mixdown,

youll press the Reverse switch on each channel, which will route the Mix B inputs

to the channel strip and the channel inputs to Mix B. Youll also be able to route all

of the Mix B outputs as a group to the L/R bus for mixdown to a 2-track recorder.

This is how you double the number of inputs at mixdown. By doing this, all of your

tape tracks are now routed to the channel strips, with the full complement of

channel strip controls available to the tape tracks for mixdown, while at the same

time allowing you to connect sources, such as MIDI tracks, that dont need as

much processing, to the Mix B inputs, which can also be recorded to the 2-track

deck. This means that Mix B, which is normally used as a tape return, can also be

used for recording during mixdown. In addition, Mix B has access to some of the

channel EQ and Aux Sends.

Complete descriptions of all the features, a Quick Start Guide, and a Tutorial fol-

low later in this guide.

Page 12

1.8 GHOST Introduction

Page 13

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

Page 19

Page 20

Page 21

Page 22

Page 23

Page 24

Page 25

GHOST Quick Start Guide 3.1

GGHHOOSSTT

QQuuiicckk SSttaarrtt GGuuiiddee

3

Page 26

3.2 GHOST Quick Start Guide

QQuuiicckk SSttaarrtt GGuuiiddee

We suggest that you read this entire manual before using Ghost; but for those who

want to get started right away, we have provided this QUICK START GUIDE.

This will get you up and running quickly. The basic procedures given here are

taken from the TUTORIAL chapter, which contains much more detailed informa-

tion. If you dont understand something in this chapter, then refer to the TUTORI-

AL. However, to get the full benefit of Ghosts many features, it is suggested that

at some point you read this entire manual.

RReeccoorrddiinngg BBaassiicc TTrraacckkss ((TTrraacckkiinngg))

Procedure:

1.

Reset Console. "Zero Out" or reset the console. That means to set all

controls to their off or neutral positions.

2. Connections. Connect your input sources to the channel MIC and LINE

inputs.

3. Select Inputs. Use the MIC/LINE switch to select the appropriate input

for each channel. Press the 48V switch for condenser mics, where

required. Make sure the REV switch is not depressed.

4. Recording methods. There are 3 methods you can use to send the chan-

nel signal to a multitrack tape recorder (MT), and they are outlined below:

a. Using the Group Output jacks. Use this method if the GRP 1-8 output

jacks are connected to the inputs of your multitrack recorder. The group

number should match the tape input number. In the channel strip, press the

assign switch for the tape track(s) you want to record on. Next, use the

pan pot to send the signal to the Group output jack for the track(s) you

wish to record on. Pan left for odd-numbered tracks; right for even-num-

bered tracks; and centre for both tracks. Then, turn up the channel fader

to its nominal position, as indicated by the fader marking 3/4 of the way up.

Finally, turn up the appropriate Group fader(s) to its nominal position.

b. Using the DIR/TAPE SND jack as a Group Output. Use this method if

the DIR/TAPE SND jacks are connected to the inputs of your multitrack

recorder, and you wish to use the Groups for recording. The channel num-

ber should match the tape input number.

First, press the DIR/GRP n switch (on the rear connector panel) on the

channel that represents the tape track you wish to record on. Then note

the GRP n number on the switch. For instance, both channels 2 and 10 will

have a switch that reads DIR/GRP 2. This means that the channel 2 and

channel 10 DIR/TAPE SND jacks will act as Group 2 output jacks, when

their DIR/GRP 2 switches are pressed.

Next assign all the inputs youre recording to the appropriate Group num-

ber(s) and use the pan pot to send the signal to the appropriate Group bus.

Pan left for odd-numbered groups; right for even-numbered groups; and

centre for both groups.

Then, turn up the channel fader to its nominal position, as indicated by the

fader marking 3/4 of the way up. Finally, turn up the Group fader(s) to its

nominal position.

c. Using the DIR/TAPE SND jack as a Direct Output: Use this method if the

DIR/TAPE SND jacks are connected to the inputs of your multitrack

recorder, and you wish to record directly from the channel outputs. The

channel number should match the tape input number.

Page 27

GHOST Quick Start Guide 3.3

This method differs from method (b), above, because youre using the

DIR/TAPE SND jack as a Direct Output from the channel and the Group

buses are not involved at all. The channel signal, post-fader and post-mute,

will be routed to this jack for direct recording to your multitrack.

To use this method, first make sure the DIR/GRP n switch (on the rear con-

nector panel) is in the DIR (UP) position for all channels that you wish to

record. Then, turn up the channel fader to its nominal position, as indicated

by the fader marking 3/4 of the way up. The pan pot and assign switches will

have no effect on the Direct Output signal.

Select one of the above three recording methods and then proceed to step 5.

5. Setting Up The MT. On the MT, insert a tape, wind to where you wish to

begin recording, set the counter to zero, put the appropriate tracks into

RECORD-READY mode, and set the recording level controls of the MT, if

any, to their nominal positions.

6. Monitoring. To learn how to listen to the sound you are recording, see the

section below entitled, "Control Room Monitoring." To learn how to send the

sound you are recording to the musicians in the studio, see the section below

entitled, "Studio Monitoring."

With the musicians playing, set up preliminary monitor mixes for the Control

Room and Studio.

7. Gain Structure. If you have the optional meterbridge and its set for channel

input monitoring, then gradually turn up the Input Sensitivity knob until the

meterbridge channel input meter indicates 0.

In all other instances, press the channel SOLO switch. Make sure the SIP

switch in the master section is off. This will display the channel signal on the

CRM/SOLO-L/R meters in the master section. Gradually turn up the Input

Sensitivity knob until the meters indicate 0, then turn the SOLO switch off.

In either case, the Signal Present LED should be brightly lit, and the PK LED

should light only occasionally, if at all.

8) LCF & Phase. Use the Low-Cut Filter (LCF) switch to get rid of low fre-

quency noise. The Phase switch should be in the up position, unless you

know your input cables are wired incorrectly or if youre employing M-S

recording techniques.

9. EQ. If you want to add EQ to the channel inputs, first press the EQ IN switch

and make sure the EQ MIX B button is up. Then apply the EQ as needed.

The HF/LF shelving EQ can be boosted or cut 15dB. The HMF/LMF EQ are

true parametrics and allow you to select the centre frequency, the bandwidth

of that frequency (with the Q control), and apply boost or cut of 15dB.

10. Effects & Processing. If you want to add effects or processing, then see the

section below, entitled, "Adding Effects and Processors."

11. Adjust Faders. Adjust the channel and group faders, as required, so that the

multitracks meters display the desired recording level.

12. Recording. Set up your final monitor mixes, and then have the musicians

stop playing. Put the MT into RECORD mode and have the musicians play the

song. When the song is over, STOP the multitrack and rewind the tape to

zero.

13. Playback. Play back the tracks you have just recorded. To let the musicians

in the Studio hear the take, select CRM as the Source in the appropriate

Studio Foldback section.

Page 28

3.4 GHOST Quick Start Guide

14. Record Another Take. If dissatisfied, record over the first take or add

another take after it. Before recording again, remember to unselect CRM

and select AUX 1-2 as the Studio Foldback Source, if necessary.

15. Proceed With Overdubbing. When you are satisfied with the take of the

basic tracks, you can proceed to "Overdubbing," below.

OOvveerrdduubbbbiinngg

Procedure:

1. Tape Channels. On all channels that contain the outputs of previously

recorded tape tracks, press the REV switch and set the MIX B SRCE switch

to CHAN. This routes the Tape Returns to both the Channel and MIX B

paths. These are your Tape channels and are for monitoring purposes only.

2. Connections. Connect your input sources for the overdub to the channel

MIC and LINE inputs. Do not connect them to any Tape channels. These

are your Input channels.

3. Select Inputs. On the Input channels, use the MIC/LINE switch to select

the appropriate input for each channel. Press the 48V switch for condenser

mics, where required. Make sure the REV switch is not depressed and set

the MIX B SRCE switch to TAPE.

4. Select Recording Method. Select one of the 3 recording methods, from

above, and follow the directions for signal routing and channel/group fader

positioning for each Input channel.

5. Setting Up The MT. On the MT, rewind the tape to the beginning of the

song, or to a point before the overdub will be recorded, set the counter to

zero, and put the appropriate track(s) into RECORD-READY mode. Make

sure that all previously recorded tracks are not in RECORD-READY mode.

Then set the recording level controls of the MT, if any, to their nominal

positions and start playing the tape.

6. Monitoring And Gain Structure. With the musicians playing along with

the tape, set up Control Room and Studio preliminary monitor mixes of the

overdub being recorded and of previously recorded tape tracks. (See

Control Room/Studio Monitoring, below.) Then use the INPUT SENSITIVI-

TY knob to set your input gain structure for the overdub, using the optional

meterbridge or the CRM/SOLO-L/R meters, and the SIG and PK LEDs.

(See "Recording Basic Tracks," above.)

7. LCF & Phase. Use the LCF and PHASE switches, as required. (See above.)

8. EQ. Apply EQ, as required. (See above.)

9. Effects & Processing. If you want to add effects or processing, then see

the section below, entitled, "Adding Effects and Processors."

10. Adjust Faders. Adjust the channel and group faders, as required, so that

the multitracks meters display the desired recording level.

11. Recording. Set up your final monitor mixes, of both the live signal and of

previously recorded tape tracks, and then have the musicians stop playing.

Put the MT into RECORD mode and have the musicians play the overdub.

When the overdub is over, STOP the multitrack and rewind the tape to

zero or to a point right before the overdub.

12. Playback. Play back the overdub you have just recorded. To let the musi-

cians in the Studio hear the take, select CRM as the Source in the appropri-

ate Studio Foldback section.

Page 29

GHOST Quick Start Guide 3.5

13. Record Another Take. If dissatisfied, record over the first take of the

overdub. Before recording again, remember to unselect CRM and select

AUX 1-2 as the Studio Foldback Source, if necessary.

14. Proceed With Overdubs & Mixing Down. When you are satisfied with

the take of the overdub, proceed to record the next overdub. When youre

satisfied with all the tracks on the tape, you can proceed to "Mixing Down",

below.

MMiixxiinngg DDoowwnn

Procedure:

1. Inputs. "Zero Out" the console and then press the REV switches to route

all your tape tracks to the channel path. Channel inputs on those channels

will be routed to the MIX B path. If you have additional input sources, such

as MIDI tracks, and extra channels available (that are not being used for

tape tracks), then route the additional sources to the channel path. If you

have more input sources than channels, then connect some to the channel

inputs and some to the MIX B inputs. Then decide where best to route

those extra sources, between the channel and MIX B paths. You can also

use the Effects Returns as line level source inputs, but remember that youll

probably also need inputs for the outputs of your effects devices. Make

sure the MIX B SRCE switch is set to TAPE (UP) on all channels, unless you

wish to use it as a pre-fader send for the channel path.

2. Assignment & Master Levels. Assign all channels and Effects Returns that

are in use to the L/R MIX by pressing the L/R assign switch on the channels

and the MIX assign switch on the Effects Returns. Press the MIX B TO MIX

switch in Ghosts MIX B master section and set the MIX B rotary master

fader about 75% up. Set the MIX L/R master fader to the top of its travel.

3. Using Groups. If youre grouping some sources, assign them to the appro-

priate Group buses and then assign the Group buses to the L/R MIX, using

the TO MIX- L, R, and L+R switches in the Group master section. Turn

the appropriate Group faders about 75% up.

4. Monitoring. Set the CRM SRCE to monitor MIX A only, turn up the level

control, and make sure MONO CHECK is off. To send the mix to the stu-

dio, select CRM as the source in the appropriate Studio Foldback section

and turn up its level control.

5. Input Gain. Adjust the INPUT SENSITIVITY and TAPE TRIM knobs, if

needed. (See above.)

6. Setting Up The MT. Rewind the MT tape, set the counter to zero, and

start playback. If the MT has an output level control, set it to its nominal

position. If youre syncing a sequencer to the tape, make sure its set up

properly, so that the MIDI tracks are also playing.

7. Practice The Mix. As the tape plays, set the relative levels of the

tape/MIDI tracks using the channel and MIX B faders, (and the FX level

controls, if they are being used as inputs). Use the PAN and BAL controls

to set the stereo perspective. USE EQ, effects, and processors, as needed.

(See "Effects and Processors," below.) Use the MUTE Automation system,

as needed. (Not Ghost LE). (See the "CPU Application Guide" in this manu-

al.) Use the MONO CHECK switch periodically to check for mono com-

patibility. Listen to the mix through your main speakers, your alternate

speakers, if any, and headphones. Keep practicing the mix, until youre

happy with it, then rewind the MT tape to the beginning of the song.

Page 30

3.6 GHOST Quick Start Guide

8. Setting Up The 2-Track. Insert a new tape in your 2-track recorder and

rewind it to the beginning. Roll about one minute into the tape and use the

TO TAPE switches in the Talkback and Oscillator sections to record any

announcements and tones that are needed. Allow the tape to roll a bit past

the tones, stop the 2-track, and set the counter to zero. Then, set the deck

to RECORD-READY mode and set its input level control to its nominal

position.

9. Setting Levels. Play the MT tape again, and adjust the MIX L/R Master

fader, MIX B Master fader, and Group Master faders, to retain the proper

balance of your mix, while at the same time, achieving the proper level on

your 2-track recorders meters. The proper recording level should be

achieved with the 2-tracks input control at its nominal position. Then

rewind the MT tape to the beginning of the song.

10. Recording The Mix. To commit your final mix to tape, start the 2-track in

RECORD mode and then start playback of the MT tape. Make any mix

moves that are necessary and when the song is completed, stop the 2-

track, then stop the MT. Press the appropriate 2-TK switch in the CRM

SRCE section, unselect MIX A, and then rewind and play back the 2-track

tape. If youre not satisfied with the final mix, then unselect the 2-TK CRM

SRCE switch, select MIX A, and try the mix again. If you are satisfied with

the mix, then make a dub of the 2-track master and play the dub on as

many systems as you can. If youre not satisfied, then mix it again. If the mix

meets with your approval on these other systems, then make a backup

copy of the 2-track master and label everything. This final 2-track stereo

master tape is now ready for mastering and/or duplication.

Page 31

GHOST Quick Start Guide 3.7

CCoonnttrrooll RRoooomm MMoonniittoorriinngg

CCRRMM SSiiggnnaall MMoonniittoorriinngg

Procedure:

1. Follow the procedures under "Recording Basic Tracks" to send your live

signals to the MT for recording.

2. On Ghost, make sure all CUT and SOLO/PFL/AFL switches are off, and

that the REV switch is OFF (UP) in the MIX B channel(s) you will use for

monitoring.

3. On the MT, press the RECORD-READY switches for the track(s) you wish

to record on and set the record level control, if any, to its nominal position.

4. In the CRM SRCE section, make sure that only MIX B is pressed and that

MONO CHECK is off. Turn the CRM LEVEL knob about 75% up.

5. Turn the MIX B master fader in Ghosts master section about 75% up.

6. On the appropriate MIX B section that corresponds to the track you are

recording on, make sure the SRCE switch is set to monitor TAPE (UP

Position).

7. With the performers playing their parts, (there should be a reading on the

MTs meters for the track(s) you are recording), adjust the TAPE TRIM

knob in the appropriate channel strips input section, if necessary. Then

turn up the appropriate MIX B level control to attain the volume you want

and use its pan pot to determine the stereo placement. You will now be

monitoring all signals sent to the appropriate tape track.

8. The Channel faders, Group faders (if youre recording with the Group

buses), TAPE TRIM knob, MIX B master fader, MIX B level control, CRM

LEVEL knob, and the MT record level control, if any, will all affect the vol-

ume of the monitored signal.

CCRRMM TTaappee MMoonniittoorriinngg

Procedure:

1. On Ghost, make sure all CUT and SOLO/PFL/AFL switches are off, and

that the REV switch is ON (Down) in the MIX B channel(s) you will use for

monitoring tape playback.

2. In the CRM SRCE section, make sure that only MIX B is pressed and that

MONO CHECK is off. Turn the CRM LEVEL knob about 75% up.

3. Turn the MIX B master fader in Ghosts master section about 75% up.

4. On the appropriate MIX B section that corresponds to the tape track you

wish to monitor, make sure the SRCE switch is set to monitor CHAN

(DOWN Position). You are really monitoring TAPE, since the channel and

MIX B paths have been reversed.

5. Set the output level control on the MT, if any, to its nominal position, and

with the MT tape playing, adjust the TAPE TRIM knob in the channel strips

input section, if necessary. Then turn up the appropriate MIX B level con-

trol to attain the volume you want and use its pan pot to determine the

stereo placement. You will now be monitoring the tape playback of the

appropriate track.

6. The TAPE TRIM knob, MIX B master fader, MIX B level control, CRM

LEVEL knob, and the MT output level control, if any, will all affect the vol-

ume of the monitored signal.

Page 32

3.8 GHOST Quick Start Guide

SSttuuddiioo MMoonniittoorriinngg

SSttuuddiioo SSiiggnnaall MMoonniittoorriinngg

Procedure:

1. Follow the procedures under "Recording Basic Tracks" to send your live

signals to the MT for recording.

2. On Ghost, make sure all CUT and SOLO/PFL/AFL switches are off, and

that the REV switch is OFF (UP) in the channel(s) that you are going to

monitor.

3. In the STUDIO FOLDBACK section, decide whether you are using STU-

DIO A or STUDIO B/PHONES and make sure that only AUX 1-2 is

pressed. Turn the STUDIO LEVEL knob about 75% up.

4. Turn the AUX 1 and AUX 2 master fader pots in Ghosts master section

about 75% up and make sure their AFL switches are off.

5. On the appropriate channels that correspond to the channel inputs you are

about to record, make sure the AUX 1-2 PRE switches are depressed, so

that you are monitoring Pre-Fader.

6. With the performers playing their parts, turn up the AUX 1-2 level con-

trols, on all channels whose signals you want to monitor, to attain the vol-

ume (and balance) you want. AUX 1 will be sent to the left headphone

(speaker) and AUX 2 will be sent to the right headphone (speaker). You

will now be monitoring all channel input signals.

7. The AUX 1-2 master faders, AUX 1-2 level controls, and STUDIO LEVEL

knob, will all affect the volume of the monitored signal.

SSttuuddiioo TTaappee MMoonniittoorriinngg

Procedure:

1. On Ghost, make sure all CUT and SOLO/PFL/AFL switches are off, and

that the REV switch is ON (Down) in the channel(s) you will use for moni-

toring tape playback.

2. In the STUDIO FOLDBACK section, decide whether you are using STU-

DIO A or STUDIO B/PHONES and make sure that only AUX 1-2 is

pressed. Turn the STUDIO LEVEL knob about 75% up.

3. Turn the AUX 1 and AUX 2 master fader pots in Ghosts master section

about 75% up and make sure their AFL switches are off.

4. On the appropriate MIX B sections that correspond to the tape tracks you

wish to monitor (in the control room), make sure the SRCE switch is set to

monitor CHAN (DOWN Position). You are really monitoring TAPE, since

the channel and MIX B paths have been reversed. This has no effect on

Studio Tape Monitoring, but must be done in order to use MIX B for CRM

Tape Monitoring.

5. On the appropriate channels that correspond to the tape tracks you wish

to monitor, make sure the AUX 1-2 PRE switches are depressed, so that

you are monitoring Pre-Fader.

6. Set the output level control on the MT, if any, to its nominal position, and

with the MT tape playing, adjust the TAPE TRIM knob in the appropriate

channel strips input section, if necessary. Then turn up the AUX 1-2 level

controls, on all channels that correspond to the tape tracks you want to

monitor, to attain the volume (and balance) you want. AUX 1 will be sent

Page 33

GHOST Quick Start Guide 3.9

to the left headphone (speaker) and AUX 2 will be sent to the right head-

phone (speaker). You will now be monitoring the tape playback of the

appropriate tracks.

7. The TAPE TRIM knob, AUX 1-2 master faders, AUX 1-2 level controls,

STUDIO LEVEL knob, and the MT output level control, if any, will all affect

the volume of the monitored signal.

MMoonniittoorriinngg SSuummmmaarryy

To sum up, if tracks 1 and 2 were already recorded and you were currently

recording on track 3 through the channel 10 input, then for control room moni-

toring, you would use the MIX B sections of channels 1 and 2 to monitor the tape

playback of tracks 1 and 2, and you would use the MIX B section of channel 3 to

monitor what you were currently recording to track 3. For studio monitoring, you

would use AUX 1-2 of channels 1 and 2 to monitor the tape playback of tracks 1

and 2, and you would use AUX 1-2 of channel 10 (where the input is located) to

monitor what you were currently recording to track 3.

Page 34

3.10 GHOST Quick Start Guide

AAddddiinngg EEffffeeccttss aanndd PPrroocceessssoorrss

1. External Treatment. With this method you alter the signal before it

reaces Ghost. It is commonly used by guitarists, when using "stomp boxes."

For example, you connect a guitar cable to the input of a delay box, then

you connect the output of the box to one of Ghosts LINE inputs. You use

the effects mix control to determine the balance of wet and dry signals that

enters Ghost. External treatment does not require using any of Ghosts

controls. You simply plug the treated signal into one of Ghosts inputs.

2. Using Processors. Outboard processors are connected to Ghost using a

send/return Y-cable connected to one of Ghosts Insert jacks. The signal

from Ghost is sent to the outboard device, processed, and then the

processed signal is returned to Ghost. You use this method when you want

to treat the entire signal, as opposed to blending the wet and dry signals.

Youll generally use outboard EQ or dynamics processors with the Inserts.

Ghost has Inserts on all Channels, Groups, and the L/R Mix. Using proces-

sors with Ghost just requires that you connect them properly to Ghosts

Insert jacks. It does not require using any of Ghosts controls.

3. Using Effects. To use effects with Ghost, you can use the AUX system.

This method involves sending a copy of a channel/MIX B signal to the out-

board effect, processing it, and then returning it to Ghost. This wet signal is

then combined with the dry signal within Ghost.

NNoottee aabboouutt SSttuuddiioo MMoonniittoorriinngg aanndd EEffffeeccttss

The FX Returns were designed to add effects during mixdown, or while multi-

tracking in the control room and only using the control room monitor section.

When using the FX Returns, you cannot monitor the wet signal in the Studio

Foldback sections. However, you can record the wet signal to the multitrack or

the mixdown deck and you can monitor it in the Control Room. If youre record-

ing the effect and the performers dont care if they hear the effect while perform-

ing, then you can use the FX Returns. However, if the performers want to hear

the effect while recording, or if you want to record dry, but monitor wet, then

you should not use the FX Returns. You should connect the stereo outputs of

your effects device to 2 channel inputs and use those channels to route the wet

signal to the Group or L/R buses for recording, if desired, and to the Control

Room and Studio monitoring sections.

For connecting effects devices to the FX Returns. Studio Monitoring is not

possible

Procedure:

1. First, select which AUX Send you wish to use, based on whether you wish

to use it with a Channel or MIX B input and whether your effect has mono

or stereo inputs. Lets say you want to use AUX 1. (If you use AUX 1 or 2,

make sure the PRE switch is not pressed.) Connect the AUX 1 output jack

to the input of your effects device. Connect the L/R outputs of your effects

device to the FX 1-L/R jacks. (Note that you can use any FX RETURN.)

2. On the effects device, set the input level and output level controls to their

nominal positions. Make sure the effects unit is set for 100% wet output

and select the effect you wish to use.

3. Turn the AUX 1 rotary master fader control about 75% up. With a signal

present, turn the AUX 1 Send controls about 75% up on all channels that

you wish to be treated with the effect. This sends the channel signals to the

effects device.

Page 35

GHOST Quick Start Guide 3.11

4) There should be a reading on the input meter of the effects device, showing

that there is a signal present. If youre recording to a multitrack deck, then

set the Control Room Source to MIX B. If youre mixing down, then set the

Control Room Source to MIX A. Turn the Control Room Level knob 75%

up. You cannot monitor the effect in the Studio Foldback sections.

5. Use the Channel ASSIGN switches and PAN Pots to route the dry signals to

the appropriate buses, as usual. Use the FX 1 ASSIGN switches and BAL

knob to route the wet signal to the appropriate buses. You can record the

wet signal on the same tape tracks as the dry signals or on their own tape

tracks. Turn the appropriate Group Faders about 75% of the way up (if mul-

titracking) and set the MIX fader to the top of its travel (if mixing down).

This sends the wet and dry signals to the buses.

6. In the control room, to monitor the effect while youre recording to a multi-

track deck, you use the MIX B section in the channel strip that represents

the tape track the effect is being recorded on. To monitor the effect while

mixing down, you should assign the FX Return to the L/R Mix by pressing the

MIX switch, and then monitor MIX A in the control room, as usual. To

record dry and monitor wet, assign the FX Return to the L/R Mix by pressing

the MIX switch, but dont assign it to the Groups. Set the Control Room

Source to monitor both MIX A and MIX B. MIX B is what you normally use

for control room monitoring and MIX A would be used to monitor the

effect.

7. Turn the FX 1 level control about 75% up. This returns the wet signal from

the effects device to Ghost.

8. With a signal present in the channels youre using, you should be able to hear

the effect. Adjust the AUX 1 Send controls to determine how prevalent the

effect will be for each channel. For instance, all other things being equal, if

the AUX 1 Send control is turned 75% up for one channel and 50% up for

another channel, you will hear the effect more for the former channel.

9. After setting the AUX 1 Send levels for all the channels, press the AUX 1

Master Fader AFL switch. This will send all AUX 1 levels, post-AUX 1 mas-

ter fader, to the CRM/SOLO-L/R meters. Adjust the AUX 1 Master Fader so

that the meters read 0, then turn AFL off.

10. Adjust the input level of the effects device to achieve the meter reading on

the effects device, suggested by the devices manual.

11. Then press the PFL switch in the FX 1 section. This will display the effects

signal returned to Ghost, pre-FX 1 level control, on the CRM/SOLO-L/R

meters. Adjust the output level of the effects device so that the meters read

0, then turn PFL off.

12. Finally, adjust the FX 1 level control, together with the channel faders, to

achieve the blend of wet/dry signals that you desire. The channel faders con-

trol the dry signal and the FX 1 level knob controls the wet signal. The

Group/MIX faders control the overall signal sent to the Group/MIX buses.

Remember that the individual AUX 1 Send knobs and AUX 1 master fader

determine the level of the signal sent to the effects device and the FX 1 level

knob determines the level of the signal returned to Ghost.

Page 36

3.12 GHOST Quick Start Guide

For connecting effects devices to 2 Channel LINE Inputs (Channel

Returns).

Studio Monitoring is possible.

Procedure:

1. First, select which AUX Send you wish to use, based on whether you wish

to use it with a Channel or MIX B input and whether your effect has mono

or stereo inputs. Lets say you want to use AUX 1. (If you use AUX 1 or 2,

make sure the PRE switch is not pressed.) Connect the AUX 1 output jack

to the input of your effects device. Connect the L/R outputs of your effects

device to any 2 adjacent Channel LINE inputs. Make sure their REV switch-

es are not engaged and set their MIX B SRCE switches to CHAN (Down).

2. On the effects device, set the input level and output level controls to their

nominal positions. Make sure the effects unit is set for 100% wet output

and select the effect you wish to use.

3. Turn the AUX 1 rotary master fader control about 75% up. With a signal

present, turn the AUX 1 Send controls about 75% up on all channels that

you wish to be treated with the effect. This sends the channel signals to the

effects device.

4. There should be a reading on the input meter of the effects device, show-

ing that there is a signal present. If youre recording to a multitrack deck,

then set the Control Room Source to MIX B. If youre mixing down, then

set the Control Room Source to MIX A. Turn the Control Room Level

knob 75% up. For multitrack recording, select AUX 1-2 as the Studio

Foldback Source and turn its level control 75% up.

5. Use the Channel ASSIGN switches and PAN Pots to route the dry signals

to the appropriate buses. If you want to record the wet signal, then using

the Channel Returns, set their ASSIGN switches and PAN Pots to route the

wet signals to the appropriate buses. You can record the wet signals on the

same tape tracks as the dry signals or on their own tape tracks. Turn the

appropriate Group Faders about 75% of the way up (if multitracking) and

set the MIX fader to the top of its travel (if mixing down). This sends the

wet and dry signals to the buses.

6. In the control room, to monitor the effect while youre recording to a mul-

titrack deck, you use the MIX B section in the channel strip that represents

the tape track the effect is being recorded on. To monitor the effect while

mixing down, you should assign the Channel Returns to the L/R Mix by

pressing the L/R switch, and then monitor MIX A in the control room, as

usual. To record dry and monitor wet, dont assign the effect to the Groups

and use the MIX B sections in the Channel Returns to monitor the effect.

7. Set the Channel Return Faders to their nominal positions. This returns the

wet signal from the effects device to Ghost.

8. With a signal present in the channels youre using, you should be able to

hear the effect. Adjust the AUX 1 Send controls to determine how preva-

lent the effect will be for each channel. For instance, all other things being

equal, if the AUX 1 Send control is turned 75% up for one channel and

50% up for another channel, you will hear the effect more for the former

channel.

9. To send the effect to the performers in the Studio, whether or not you are

recording the effect, use the AUX 1-2 Sends on the Channel Returns.

These AUX 1-2 controls should be set up as Pre-Fader Sends by pressing

the PRE switch.

Page 37

GHOST Quick Start Guide 3.13

10. After setting the AUX 1 Send levels for all the channels, press the AUX 1

Master Fader AFL switch. This will send all AUX 1 levels, post-AUX 1 mas-

ter fader, to the CRM/SOLO-L/R meters. Adjust the AUX 1 Master Fader

so that the meters read 0, then turn AFL off.

11. Adjust the input level of the effects device to achieve the meter reading on

the effects device, suggested by the devices manual.

12. Then press the SOLO switches (with SIP Off) in the Channel Returns. This

will display the effects signal returned to Ghost, pre-channel fader, on the

CRM/SOLO-L/R meters. Adjust the output level of the effects device so

that the meters read 0, then turn SOLO off.

13. Finally, adjust the Channel Faders and Channel Return Faders for the wet

and dry signals, to achieve the wet/dry recording mix that you desire.

Adjust the MIX B level controls and AUX 1-2 Sends to achieve the wet/dry

monitoring mix that you desire for the control room and studio, respective-

ly. The Channel Faders that contain the signal sources control the dry signal

and the Channel Return Faders control the wet signal. The Group/MIX

faders control the overall signal sent to the Group/MIX buses. The MIX B

controls are used for control room monitoring and the AUX 1-2 controls

are used for studio monitoring. Remember that the individual AUX 1 Send

knobs and AUX 1 master fader determine the level of the signal sent to the

effects device and the 2 Channel Return Faders determine the level of the

signal returned to Ghost.

Page 38

3.14 GHOST Quick Start Guide

Page 39

GHOST Block Diagram 4.1

GGHHOOSSTT

BBlloocckk DDiiaaggrraamm

4

Page 40

4.2 GHOST Block Diagram

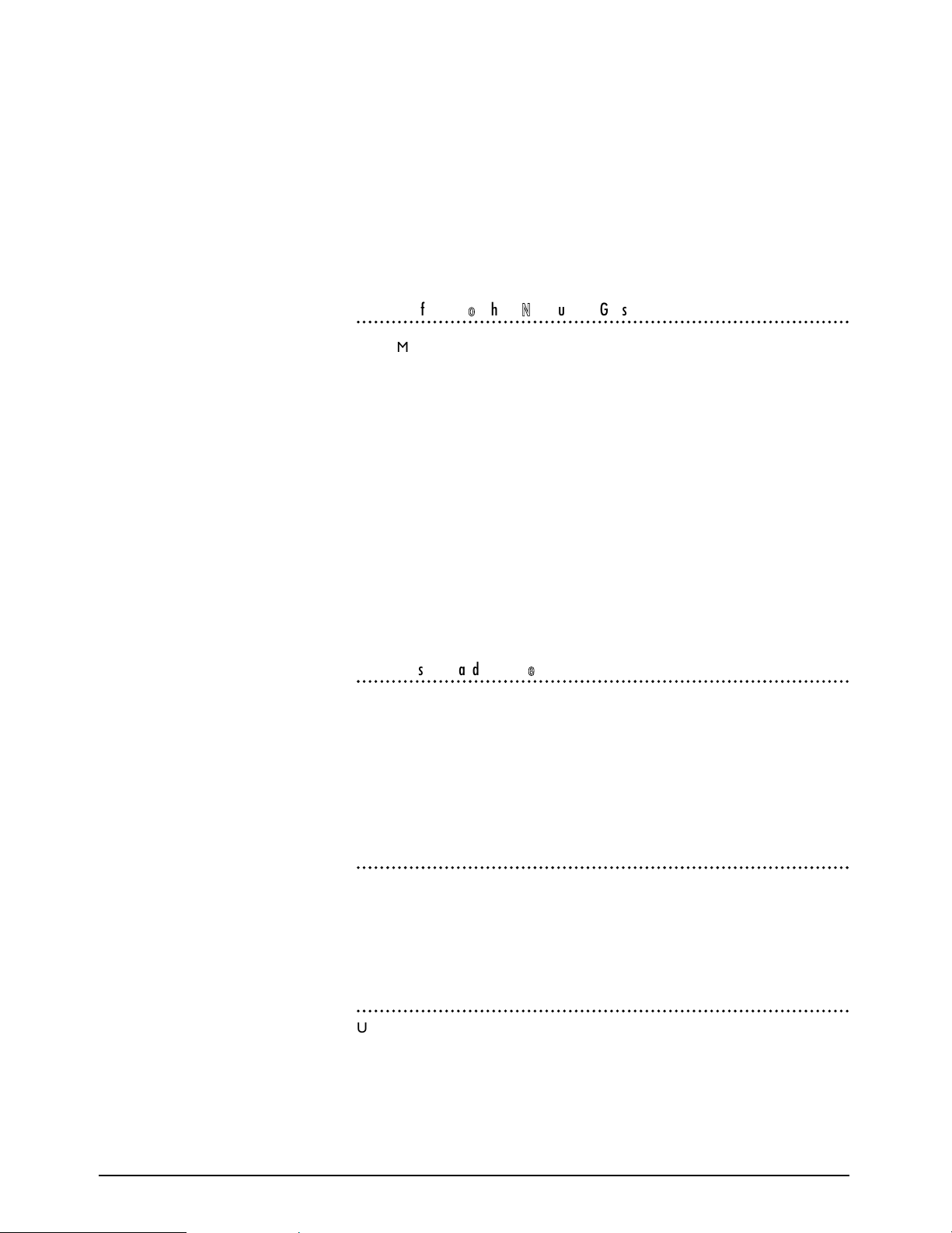

BBlloocckk DDiiaaggrraamm

PAN

L-R

1-2

3-4

5-6

7-8

AUX 7

(STEREO)

AUX 8

(STEREO)

AUX 1

AUX 3

PRE

MON

AUX 2

AUX 4

MIX B

FADER

CUT

PFL

PAN

5-6

LEFT

RIGHT

CUT

SOLO CUT

SOLO DETECT

PFL DETECT

PFL/AFL L

PFL/AFL R

AUX 1

GRP 1

GRP 2

GRP 3

GRP 4

GRP 5

GRP 6

GRP 7

GRP 8

GRP O/P BUS (1-8)

CPU MUTE BUS A

CPU MUTE BUS B

MIX L

MIX B L

MIX R

MIX B R

AUX 2

AUX 3

AUX 4

AUX 5

AUX 6

AUX 7 L

AUX 8 L

AUX 7 R

AUX 8 R

SOLO

PEAK

PFL

MUTE

SOURCE

MUTE

100mm

CHANNEL

FADER

100mm

MASTER

FADER

MIX B

MASTER

FADER

AUX7

MASTER

FADER

PFL

AFL

PFL

LEVEL

BAL

AUX 8 CIRCUIT

IS SIMILAR

TO AUX7

EQ TO MON

INSERT

POINT

LF/HF

EQ

EQ

IN/OUT

EQ

IN/OUT

GROUP N/

DIRECT

LMF/HMF

EQ

MIX LEFT

INSERT

CPU

MIX RIGHT

INSERT

MIX B

TO MIX

MIX LEFT

OUTPUT

MIX B LEFT

OUTPUT

AUX7 LEFT

OUTPUT

TB

MIC

TALKBACK

1k/10k

AUX1

OUTPUT

AUX2 TO AUX6 CIRCUITS

ARE SIMILAR TO AUX1

STUDIO B OUTPUT

IS SIMILAR TO

STUDIO A OUTPUT

MIX RIGHT

OUTPUT

MIX B RIGHT

OUTPUT

AUX7 RIGHT

OUTPUT

AFL

DIRECT

OUTPUT

PEAK

DETECT

SIGNAL

DETECT

MIC I/P

LINE I/P

TAPE I/P

+4/-10

(SNIP RESISTORS

TO SELECT

-10dBV)

48V

PHANT

POWER

FROM

48V

LINE

PHASE

INPUT

SENS

LCF

LCF

-20

REV

TAPE

TRIM

LEFT

RIGHT

FX INPUT 1

FX INPUTS 2 TO 4

ARE SIMILAR TO

FX INPUT 1

SIP

AFL/PFL

TRIM

AUX 1

SOLO

L

R

MASTER

METER

AFL/PFL

OVERRIDE

2-TRACK B L

2-TRACK A L

2-TRACK B R

-10dBV

+4dBu

2-TRACK A R

SIP

LF/HF

EQ

2TKB

2TKA

MIX B

MIX A

CONTROL-ROOM

SOURCE SELECT

CRM

MIX B

AUX 1-2

STUDIO A

SOURCE SELECT

TAPE

OSC TO

TAPE

DIM CTL

STU

OSC

OSC

AUX 1-2

TALKBACK

ROUTING

DIM

MONO

CHECK

CRM

LEVEL

STUDIO A

HEADPHONES

ALT R

CRM R

ALT L

ALT

CRM L

LEFT

RIGHT

STUDIO A

OUTPUT

MIX

1-2

3-4

5-6

7-8

L+R

AFL

MIX R

100mm

GROUP

FADER

GROUP 2

INSERT

GROUP 2

OUTPUT

GROUPS 4, 6 & 8

ARE SIMILAR TO GROUP 2

METER

L+R

AFL

MIX L

100mm

GROUP

FADER

GROUP 1

INSERT

GROUP 1

OUTPUT

GROUPS 3, 5 & 7

ARE SIMILAR TO GROUP 1

METER

OPTIONAL

INPUT METER

+4

-10

INTERNAL

JUMPERS

+4

-10

INTERNAL

JUMPERS

Page 41

GHOST Block Diagram 4.3

BBlloocckk DDiiaaggrraamm EExxppllaannaattiioonn

A Block Diagram of Ghost appears on the previous page. What follows is a plain

English explanation of that diagram. It is primarily intended for those who are

unfamiliar with how to read a Block Diagram, but can also be useful for the more

experienced user. You can follow the diagram as you read the explanation, but just

reading the explanation alone will also be helpful.

TThhee BBaassiiccss

If you want to follow along, first position the diagram so that the top of the page is

facing to the right. The diagram is read from left to right, but not necessarily from

top to bottom. The diagram is a pictorial representation of Ghosts signal flow.

Generally, the inputs are on the left and the outputs are on the right. Youll notice

vertical lines in the middle of the diagram. These represent the various buses in

Ghost. A bus is a signal path that can contain many signals.

The pictures in the diagram represent all the controls and the input/output jacks of

Ghost, as well as some internal circuits. Most of the pictures and the buses are

labeled. We wont discuss the unlabeled pictures, such as summing amplifiers

(which appear as unlabeled triangles), but will concentrate instead on the labeled

pictures. For instance, if a connection is actually to a summing amplifier and then

to a control, we will describe the connection as being to the control and not to the

summing amplifier. This should not present a problem in understanding Ghosts

signal flow.

The other lines with the black dots represent the signal flow within Ghost. The

black dots indicate a connection with either a control, a jack, another signal flow

line, or a bus. If a lines crosses a control, a jack, a signal flow line, or a bus in the

diagram, but is not connected by a black dot, then there is no connection between

them.

Generally, the signals enter Ghost through the input diagrams on the left, travel to

the buses in the middle, and then continue to the output diagrams on the right.

There are exceptions, however. For instance, the Direct Output jacks appear on

the left of the diagram and the 2-Track Inputs appear on the right, because it is

clearer to represent them in this fashion.

To save space when there a number of identical controls, the diagram usually only

shows the signal flow for one of them and makes a note that the other controls

are similar (meaning that they function in an identical manner). For instance, the

diagram only shows the signal flow for one channel and for one FX Input, but all

channels are the same and all FX Inputs are the same.

TThhee BBuusseess

NNoottee

To read the labels for the buses, you should temporarily turn the diagram so the

top of the page is facing up.

Ghost has 31 buses represented by the 31 lines in the middle of the diagram. They

are labeled on the left. A bus is a circuit where similar signals are sent to, so that

these signals can be sent as a group to their next destination within Ghost. For

instance, all signals assigned to Group 1 are sent to the GRP 1 bus. Usually, the

buses are connected on both the input side and output side of the diagram. Most

buses carry audio signals, but some buses are used for other purposes.

Following is a brief description of each bus, starting from the bottom of the

diagram. The input side and output side of the buses are described separately.

Note that some buses are described together, such as the GRP buses and any L/R

buses, even though they are labeled separately in the diagram.

Page 42

4.4 GHOST Block Diagram

SSoolloo CCuutt

Input: This bus is connected to the channel mute circuits and operates

only when SIP is engaged. When SIP is on, if a channel SOLO switch is

engaged, it mutes all channels that dont have their SOLO switches

engaged.

Output: This bus is connected to the SIP switch.

SSoolloo DDeetteecctt

Input: This bus is connected to the channel SOLO switches and it detects

when the switch has been engaged.

Output: This bus is connected to the SIP switch, the Master SOLO LED in

the Master section, and to the AFL/PLF Override circuit.

PPFFLL DDeetteecctt

Input: This bus is connected to all PFL/AFL switches and it detects when

the switch has been engaged. (It is more accurately called PFL/AFL Detect.)

Output: This bus is connected to the Master SOLO LED in the Master

section and to the AFL/PLF Override circuit.

PPFFLL//AAFFLL LL//RR..((22 bbuusseess))--

Input: These buses are connected to all channel SOLO switches and to all

PFL/AFL switches. Whenever any PFL/AFL switch is engaged, its signal is

sent to this stereo bus. If SIP is off, then whenever any channel SOLO

switch is engaged, its signal is also sent to this stereo bus. If SIP is on, then

the channel SOLO switches operate in conjunction with the SOLO CUT

bus.

Output: These buses are connected to the AFL/PFL TRIM control in the

Master section.

AAUUXX 11--22:: ((22 bbuusseess))--

Input: These buses are connected to the AUX Send 1 and AUX Send 2

level controls. Turning up these controls, respectively, sends signals to

these buses. They are also connected to the AUX 1-2 routing switch in the

TALKBACK section.

Output: These buses are respectively connected to the AUX 1 and AUX 2

Master level controls in the Master section. They are also connected to the

AUX 1-2 Source Select switches in the STUDIO A and STUDIO B sections.

AAUUXX 33--66:: ((44 bbuusseess))--

Input: These buses are connected to the 5-6 switch which is connected to

the AUX Send 3 and AUX Send 4 level controls. If the 5/6 switch is not

engaged, then the AUX Send 3 and AUX Send 4 level controls send the

signal to the AUX 3 and AUX 4 buses. If the 5/6 switch is engaged, then the

AUX Send 3 and AUX Send 4 level controls send the signal to the AUX 5

and AUX 6 buses.

Output: These buses are respectively connected to the AUX 3-6 Master

level controls in the Master section.

Page 43

GHOST Block Diagram 4.5

AAUUXX 77 LL//RR:: ((22 bbuusseess))--

Input: These buses are connected to the AUX 7 (Stereo) level control.

Turning up this control sends signals to both buses simultaneously.

Output: These buses are connected to the AUX 7 (Stereo) Master level

control in the Master section.

AAUUXX 88 LL//RR:: ((22 bbuusseess))--

Input: These buses are connected to the AUX 8 (Stereo) level control.

Turning up this control sends signals to both buses simultaneously.

Output: These buses are connected to the AUX 8 (Stereo) Master level

control in the Master section.

GGRRPP 11--88:: ((88 bbuusseess))--

Input: These buses are connected to the 1/2, 3/4, 5/6, 7/8 Routing Matrix

switches in the channel fader section and in the effects return section. They

are also connected to the TO TAPE switches in the OSCILLATOR and

TALKBACK Routing sections.

Output: These buses are respectively connected to the Group 1-8 Insert

jacks in the Master section rear connector panel and to their respective

Group Master Faders.

MMIIXX LL//RR:: ((22 bbuusseess))--

Input: These buses are connected to the L/R Routing Matrix switches in

the channel fader section and to the MIX Routing Matrix switches in the

effects return section. They are also connected to the following switches:

the TO TAPE switches in the OSCILLATOR and TALKBACK Routing

sections; the MIX B TO MIX switch in the MIX B Master section; and the

TO MIX-L and TO MIX-R switches in the GROUP MASTER FADER

section. They represent the MAIN MIX or MIX A.

Output: These buses are respectively connected to the MIX L/R Insert

jacks in the Master section rear connector panel and to the Stereo MIX

Master Fader.

MMIIXX BB LL//RR:: ((22 bbuusseess))--

Input: These buses are connected to the pan controls in the MIX B

section. They represent MIX B.

Output: These buses are connected to the MIX B Rotary Master Fader in

the MIX B Master section. They are also connected to the MIX B SOURCE

SELECT switches in the Studio A and Studio B sections.

GGRRPP OOPP BBUUSS ((11--88)):: ((22 bbuusseess))--

Input: Signal is sent to these buses from a point directly before the GRP 1-

8 Output Jacks.

Output: These buses are connected to the DIR/GRP n switches located

above the DIR/TAPE SND jacks on the Input rear connector panel.

CCPPUU MMUUTTEE BBUUSS AA:: ((NNoott GGhhoosstt LLEE))--

Input: This bus is connected to Ghosts CPU and controls the Mute

Automation for the channel mutes.

Output: This bus is connected to the channel mute circuits.

Page 44

4.6 GHOST Block Diagram

CCPPUU MMUUTTEE BBUUSS BB:: ((NNoott GGhhoosstt LLEE))--

Input: This bus is connected to Ghosts CPU and controls the Mute

Automation for the MIX B mutes.

Output: This bus is connected to the MIX B mute circuits.

SSiiggnnaall FFllooww

We will now trace the signal flow through Ghost. Youll see that in many places

the signal branches off to a number of destinations. If we were to discuss all the

signal branches in detail as they appeared in the signal flow, you might lose sight of

the main signal path. So instead, we will mention when the signal branches off, but

continue with the main signal path flow. Then we will go back and trace the

branches in detail.

We will trace the input sides and output sides separately. For the inputs, we will

trace the Channel inputs, MIX B inputs, and Effects Returns inputs separately,

tracing them from their input jacks to the buses. For the outputs, we will trace

them from the buses to the output jacks. Then at the end, we will provide a quick

overview of the complete signal path from input to output. There are also some

items in the diagram that dont fit neatly into input/output categories, so we will

discuss them at the most appropriate points. Two of those items are the CUT

switches and the SOLO/PFL/AFL switches, so we will start with them, since they

are very common throughout Ghost. Then, when we encounter a CUT or

SOLO/PFL/AFL switch in a signal path, we will mention it, but not have to trace its

path each time.

Page 45

GHOST Block Diagram 4.7

SSiiggnnaall FFllooww

MMuuttee aanndd SSoolloo

CCUUTT SSwwiittcchheess

There is one Cut (Mute) switch for each channel and each MIX B section. All of

them are connected to a Mute Circuit. The channel Mute Circuits are connected

to CPU Mute Bus A and the MIX B Mute Circuits are connected to CPU Mute

Bus B. Both Mute Buses are connected to Ghosts CPU, which controls the

automation. (Not Ghost LE). In addition, the channel Mute Circuit is connected to

the Solo Cut Bus.

Engaging any Cut switch will mute the signal beyond the Mute Circuit. You engage

the Cut switch manually, by pressing it, or automatically, either with Solo-In-Place

(SIP) or by using Ghosts Mute Automation. With Automation, the CPU will send

signals to the Mute Circuits, via the Mute Buses, to automatically engage the Cut

switches. Solo-In-Place is discussed below.

SSOOLLOO//PPFFLL//AAFFLL SSwwiittcchheess

All channels have Solo switches and all MIX B sections have PFL (Pre-Fader-

Listen) switches. There are also numerous other PFL and AFL (After-Fader-

Listen) switches throughout Ghost. The channel Solo switches will function as

Solo-In-Place (SIP) switches (if SIP is on) or as PFL switches (if SIP is off). PFL

switches come before the fader or level control, so that the faders have no effect

on the switches, and signal will be sent, even if the fader is at its minimum level.

AFL switches come after the fader or level control, so that the faders will have an

effect on the switches, and no signal will be sent, if the fader is at its minimum

level.

On the channels only, if SIP is on, it sends a signal to the Solo Detect bus, telling

Ghost that when a channel Solo switch is engaged, the Solo Cut Bus should

engage the mute circuits for all channels that do not have their Solo switches

engaged. For the rest of this discussion, we will assume that SIP is off. If SIP is off,

then Ghost treats the channel Solos as PFL switches.

The channel Solo switches are connected to the Solo Detect and PFL/AFL-L/R

buses. The MIX B PFL switches and all other PFL/AFL switches are connected to

the PFL Detect bus and to the PFL/AFL-L/R buses. When SIP is off, the Solo

Detect bus functions identically to the PFL Detect bus. (For the rest of this

section, we will use the term solo to refer to all SOLO, PFL, and AFL switches.)

Both Detect buses are connected to the Global Solo LED in the Master Solo

section and when either bus detects that a solo switch has been pressed, it lights

the LED.

Both of the detect buses are connected to the AFL/PFL Override Circuit, which in

turn, is connected to the CRM/SOLO-L/R meters and then the CRM level control.

The PFL/AFL-L/R signal buses are connected to the AFL/PFL Trim Control, which

is also connected to the AFL/PFL Override Circuit. The Control Room section will

be covered in more detail below, but the point to note here is that whenever any

solo switch is depressed, the detect circuit sends a notice to the override circuit

telling it to mute the selected Control Room Source, and in its place, send the

signals from the AFL/PFL Trim Control to the Control Room Outputs.

What all of this means is that if you press any solo switch, the Global Solo LED will

light and all soloed signals (from the PFL/AFL-L/R bus) will be sent to the solo

Trim Control, where you can adjust the level of the soloed signals, and then to the

control room meters and headphones/control room outputs.

Page 46

4.8 GHOST Block Diagram

IInnppuuttss

CChhaannnneellss

The channel has 2 inputs: an XLR mic input and a ¼" line input. (They are located

in the upper-left of the diagram). The Mic input is connected to the 48V (phantom

power) switch and then to the Mic/Line switch. The line input is connected to the

Mic/Line switch. The Mic input has the 48V option and then you select the channel

input with the Mic/Line switch. From that point on, both inputs are treated

identically.

The channel signal then goes to the Phase switch, the Input Sensitivity knob, and

the Low-Cut Filter (LCF) switch and circuit. The last switch determines whether

the signal goes through the LCF circuit or not.

The signal continues to the Signal Present LED, the Peak Detect LED, and the

Reverse switch. This switch determines whether the signal continues down the

channel path or MIX B path. Note that even if Reverse is pressed, the channel

signal will still have passed through all the pre-Reverse points above. If Reverse is

pressed, then the channel signal will follow the MIX B path that comes after the

switch, as explained in the MIX B section below. We will continue tracing the

channel path, as if Reverse was not pressed.

The signal continues to the Channel Insert jack. If a send/return plug is inserted,

the signal will be sent to the outboard device, processed by it, and then returned

to the Insert jack. If nothing is connected, the signal proceeds from the Insert jack.

If you have the optional meterbridge and its set to monitor channel inputs, then

from the Insert jack the signal goes to the meterbridge input meter.

Next, the signal goes to the EQ MIX B switch, to the LF/HF EQ and LMF/HMF EQ

circuits, and to the EQ In/Out switch. If MIX B is pressed, the LF/HF EQ is

switched into the MIX B path and is not available to the channel. The EQ In/Out

switch is used to switch all 4 bands of EQ in or out of the signal path and it affects

the LF/HF EQ, whether that EQ is in the channel path or MIX B path. The outputs

of the 2 separate EQ circuits also go to the Peak Detect LED.

From this point, the pre-fader signal goes to the following 3 places: the channel

Solo switch, the Pre switch in the Aux 1/2 section, and the Source switch in the

MIX B section. These signals will be routed to the above destinations, regardless of

the level of the channel fader. This is the signal that will appear if you use the

channel Solo as a PFL, if you press the Pre switch in the Aux 1/2 section, or if you

select channel as the Source in the MIX B section.

The signal also travels to the channel fader, which will affect its level, and to the

mute circuit. Now the signal is a post-fader signal. If you press the Cut switch, the

signal will be muted beyond this point. If not muted, the signal goes to the

following 5 places: the Dir/Grp n switch (which is connected to the Dir/Tape Snd

jack), the channel pan knob, the Pre button in Aux 1/2, the Mix B button in Aux

3/4 (5/6), and the Peak Detect LED. If the Dir/Grp n switch is up, then the signal

continues to the Dir/Tape Snd jack as a Direct Output. If the Pre switch in Aux 1/2

is not depressed, then it is this post-fader signal that is routed there. If the Mix B

switch in Aux 3/4 is not pressed, then it is this post-fader signal that is routed

there.

Regardless of the above switch settings, the signal passes to the channel pan knob,

which is used to route the signal to the L/Odd signal path, R/Even signal path, or

both signal paths. These signal paths then go to the channel Routing Matrix (Assign)

switches and to the stereo Aux 7 level control. The signal from the Aux 7 control

goes to the Aux 7 L/R buses and the signal flow from the Routing Matrix switches

is as follows: the L/R switch goes to the Mix L/R buses, the 1/2 switch goes to the

Grp 1/2 buses, the 3/4 switch goes to the Grp 3/4 buses, the 5/6 switch goes to

the Grp 5/6 buses, and the 7/8 switch goes to the Grp 7/8 buses.

The pan control determines to which bus or buses the signal is routed. The signals

from the L/Odd path go to the Aux 7 L, Mix L, and Grp 1, 3, 5, 7 buses. The

signals from the R/Even path go to the Aux 7 R, Mix R, and Grp 2, 4, 6, 8 buses.

That is, if you pan full left, the signal goes to the left buses and odd groups and if

you pan right, it goes to the right buses and even groups. If the pan control is at its

Page 47

GHOST Block Diagram 4.9

centre detent position, the signal goes to the L/R buses and Odd/Even groups

equally. You can also select intermediate settings with the pan knob. You turn up

the Aux 7 level knob or press the assign switches to route the signals to the

appropriate buses.

At this point you have the channel input signal available as a source for the MIX B

section, and it is also available at Aux 1-4 (5/6) and Aux 7, the Solo switch, the

Dir/Tape Snd output jack, and the Mix L/R and Group 1-8 buses.

MMIIXX BB

MIX B has a ¼" line input jack. If you have the optional meterbridge and its set for

tape monitoring, then the signal goes from the input jack to the meterbridge input

meter. It also goes to the Tape Trim knob and then the Reverse switch. If

depressed, the Reverse switch can send MIX B to the channel path and the

channel to the MIX B path. If you reverse the signal, the MIX B input is still

monitored by the meterbridge, as described above, and controlled by the Tape

Trim knob. We will assume Reverse has not been pressed.

Next, the signal goes to the MIX B Source switch. As described above, the pre-

fader signal from the channel also appears here. The source switch determines if

the MIX B signal is routed to the MIX B path, or if the pre-fader channel signal is

routed there.

If the LF/HF EQ has been assigned to MIX B, then the signal is routed there and

then to the PFL switch. Note that the EQ In/Out switch must be engaged for the