Page 1

Air Conditioning

Clinic

Chilled-Water Systems

One of the Systems Series

TRG-TRC016-EN

Page 2

NO POSTAGE

NECESSARY

IF MAILED

IN THE

UNITED STATES

BUSINESS REPLY MAIL

FIRST-CLASS MAIL

PERMIT NO. 11

LA CROSSE, WI

POSTAGE WILL BE PAID BY ADDRESSEE

THE TRANE COMPANY

Attn: Applications Engineering

3600 Pammel Creek Road

La Crosse WI 54601-9985

NO POSTAGE

NECESSARY

IF MAILED

IN THE

UNITED STATES

BUSINESS REPLY MAIL

FIRST-CLASS MAIL

PERMIT NO. 11

LA CROSSE, WI

POSTAGE WILL BE PAID BY ADDRESSEE

THE TRANE COMPANY

Attn: Applications Engineering

3600 Pammel Creek Road

La Crosse WI 54601-9985

Page 3

Comment Card

We want to ensure that our educational materials meet your ever-changing resource development needs.

Please take a moment to comment on the effectiveness of this Air Conditioning Clinic.

Chilled-Water Systems

Level of detail (circle one) Too basic Just right Too difficult

One of the Systems Series

Rate this clinic from 1–Needs Improvement to 10–Excellent

…

TRG-TRC016-EN Content 12345678910

Booklet usefulness 12345678910

Slides/illustrations 12345678910

Presenter’s ability 12345678910

Training environment 12345678910

Other comments? _________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________________________

About me … Type of business _________________________________________________________

Job function _________________________________________________________

Optional: name _________________________________________________________

phone _________________________________________________________

address _________________________________________________________

Give the completed card to the

presenter or drop it in the mail.

Thank you!

The Trane Company • Worldwide Applied Systems Group

3600 Pammel Creek Road • La Crosse, WI 54601-7599

www.trane.com

An American-Standard Company

Response Card

We offer a variety of HVAC-related educational materials and technical references, as well as software tools

that simplify system design/analysis and equipment selection. To receive information about any of these

items, just complete this postage-paid card and drop it in the mail.

Education materials

❏

Air Conditioning Clinic series About me…

❏

Engineered Systems Clinic series Name ___________________________________________

❏

Trane Air Conditioning Manual Title ___________________________________________

❏

Trane Systems Manual Business type ___________________________________________

Software tools

❏

Equipment Selection Phone/fax _____________________ ____________________

❏

System design & analysis E-mail address ___________________________________________

Periodicals

❏

Engineers Newsletter Company ___________________________________________

Other?

❏

_____________________________ Address ___________________________________________

___________________________________________

___________________________________________

Thank you for your interest!

The Trane Company • Worldwide Applied Systems Group

3600 Pammel Creek Road • La Crosse, WI 54601-7599

www.trane.com

An American-Standard Company

Page 4

Chilled-Water Systems

Chilled-Water Systems

One of the Systems Series

A publication of

The Trane Company

Page 5

Preface

Chilled-Water Systems

A Trane Air Conditioning Clinic

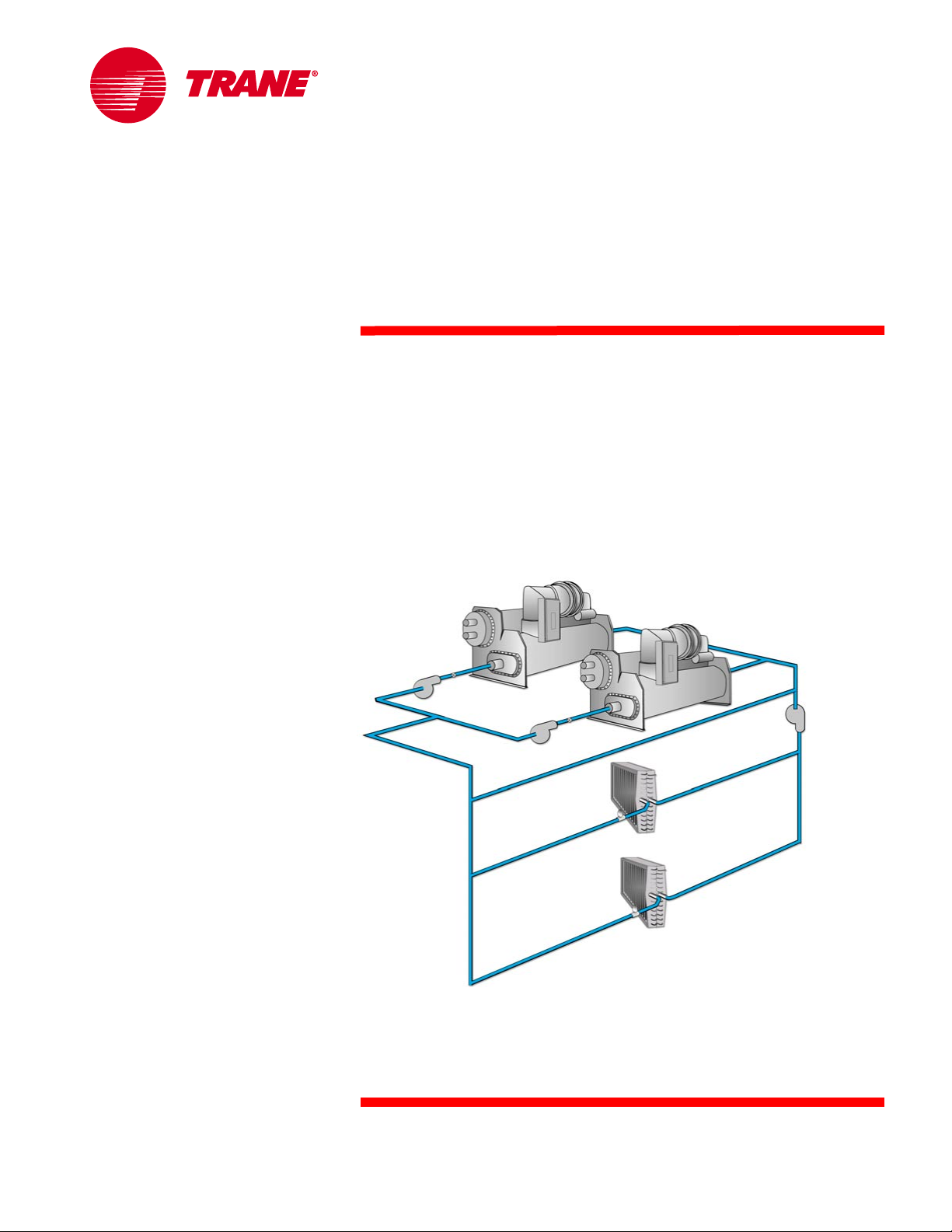

Figure 1

The Trane Company believes that it is incumbent on manufacturers to serve the

industry by regularly disseminating information gathered through laboratory

research, testing programs, and field experience.

The Trane Air Conditioning Clinic series is one means of knowledge sharing.

It is intended to acquaint a nontechnical audience with various fundamental

aspects of heating, ventilating, and air conditioning. We have taken special

care to make the clinic as uncommercial and straightforward as possible.

Illustrations of Trane products only appear in cases where they help convey

the message contained in the accompanying text.

This particular clinic introduces the reader to chilled-water systems.

© 2001 American Standard Inc. All rights reserved

i

TRG-TRC016-EN

Page 6

Contents

period one Types of Water Chillers ...................................... 1

Vapor-Compression Water Chillers .......................... 3

Air-Cooled or Water-Cooled Condensing .................. 6

Packaged or Split Components .............................. 11

Absorption Water Chillers ...................................... 15

Equipment Rating Standards ................................. 18

period two Chilled-Water System Design ........................ 26

Load-Terminal Control ........................................... 28

Parallel Configuration ............................................. 35

Series Configuration .............................................. 38

Primary-Secondary System Operation .................... 53

period three System Variations ............................................. 59

Alternate Fuel Choice ............................................ 59

Low-Flow Systems ............................................... 61

Variable-Primary-Flow Systems .............................. 64

Preferential Loading .............................................. 66

Heat Recovery ...................................................... 68

Asymmetric Design ............................................... 72

“Free” Cooling ...................................................... 75

Application Outside the Operating Range

of the Chiller

......................................................... 78

period four Chiller-Plant Control .......................................... 79

Chiller Sequencing ................................................ 82

Failure Recovery and Contingency Planning ........... 90

System Tuning ...................................................... 92

System Optimization ............................................. 96

Operator Interface ............................................... 100

period five Review ................................................................. 103

Quiz ....................................................................... 108

Answers .............................................................. 110

Glossary .............................................................. 112

TRG-TRC016-EN ii

Page 7

iii TRG-TRC016-EN

Page 8

notes

period one

Types of Water Chillers

Chilled-Water Systems

period one

Types of Water Chillers

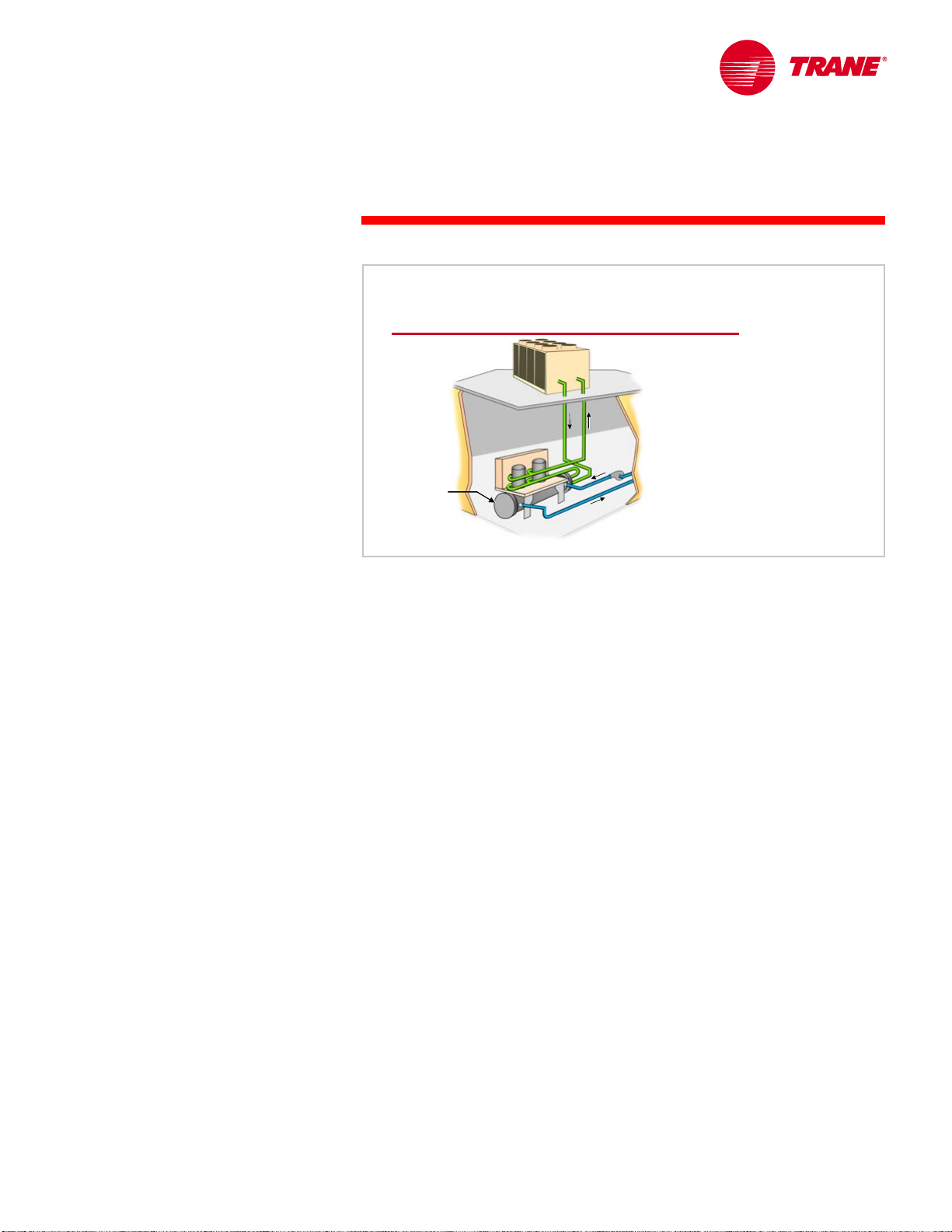

Figure 2

Water chillers are used in a variety of air conditioning and process cooling

applications. They cool water that is subsequently transported by pumps

and pipes. The water passes through the tubes of coils to cool air in an air

conditioning system, or it can provide cooling for a manufacturing or industrial

process. Systems that employ water chillers are commonly called chilled-

water systems.

When designing a chilled-water system, one of the first issues that must be

addressed is to determine which type of water chiller to use. This period

discusses the primary differences in chiller types.

absorption

water chiller

centrifugal

water chiller

The refrigeration cycle is a key differentiating characteristic between chiller

types. The vapor-compression and absorption refrigeration cycles are the two

most common cycles used in commercial air conditioning.

Figure 3

TRG-TRC016-EN 1

Page 9

period one

Types of Water Chillers

notes

Water chillers using the vapor-compression refrigeration cycle vary by the type

of compressor used. Reciprocating, scroll, helical-rotary, and centrifugal

compressors are common types of compressors used in vapor-compression

water chillers.

Absorption water chillers make use of the absorption refrigeration cycle.

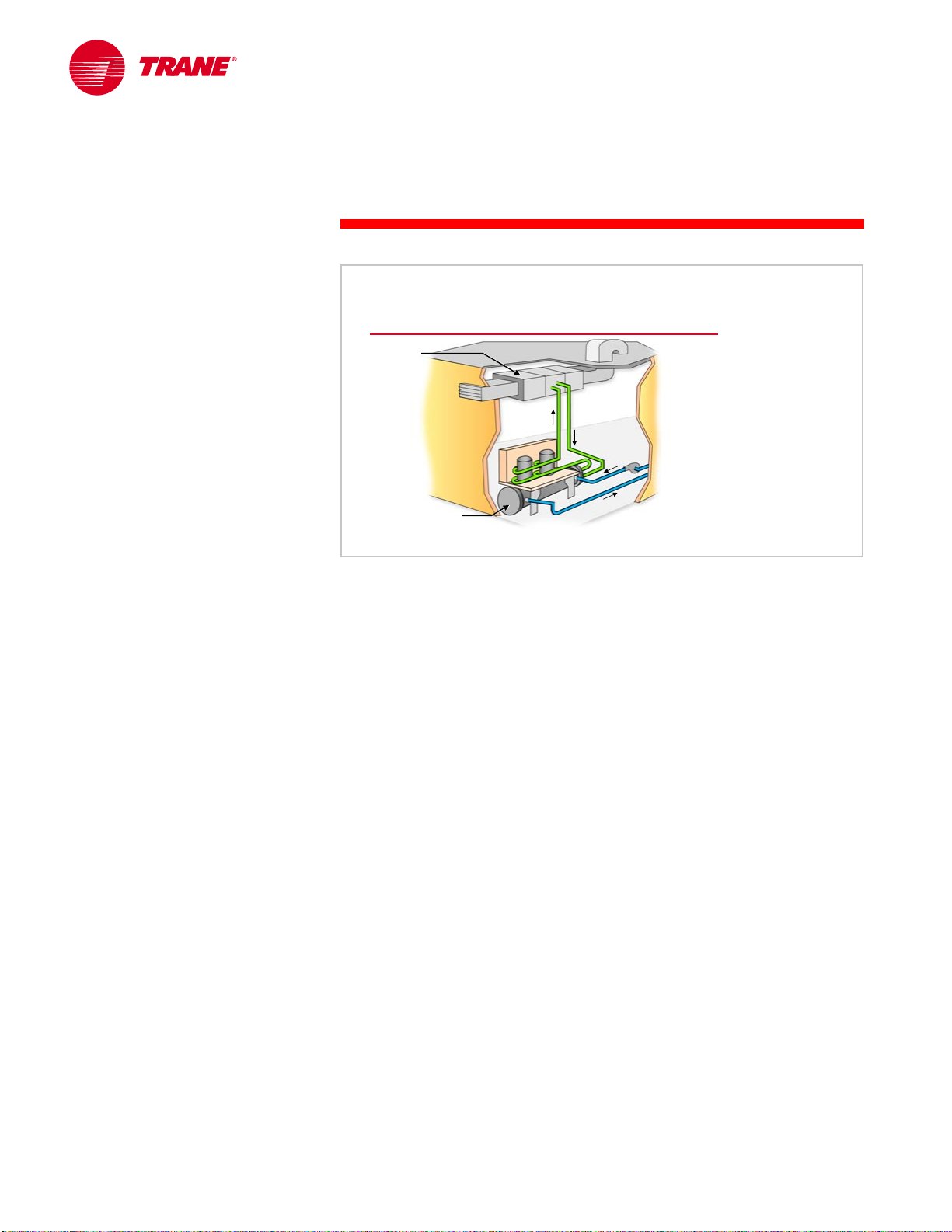

Driving Sources

compressor-driven

Vapor-compression water chillers use a compressor to move refrigerant around

the system. The most common energy source to drive the compressor is an

electric motor.

heat-driven

Figure 4

Absorption water chillers use heat to drive the refrigeration cycle. They do not

have a mechanical compressor involved in the refrigeration cycle. Steam, hot

water, or the burning of oil or natural gas are the most common energy sources

for these types of chillers.

2 TRG-TRC016-EN

Page 10

notes

period one

Types of Water Chillers

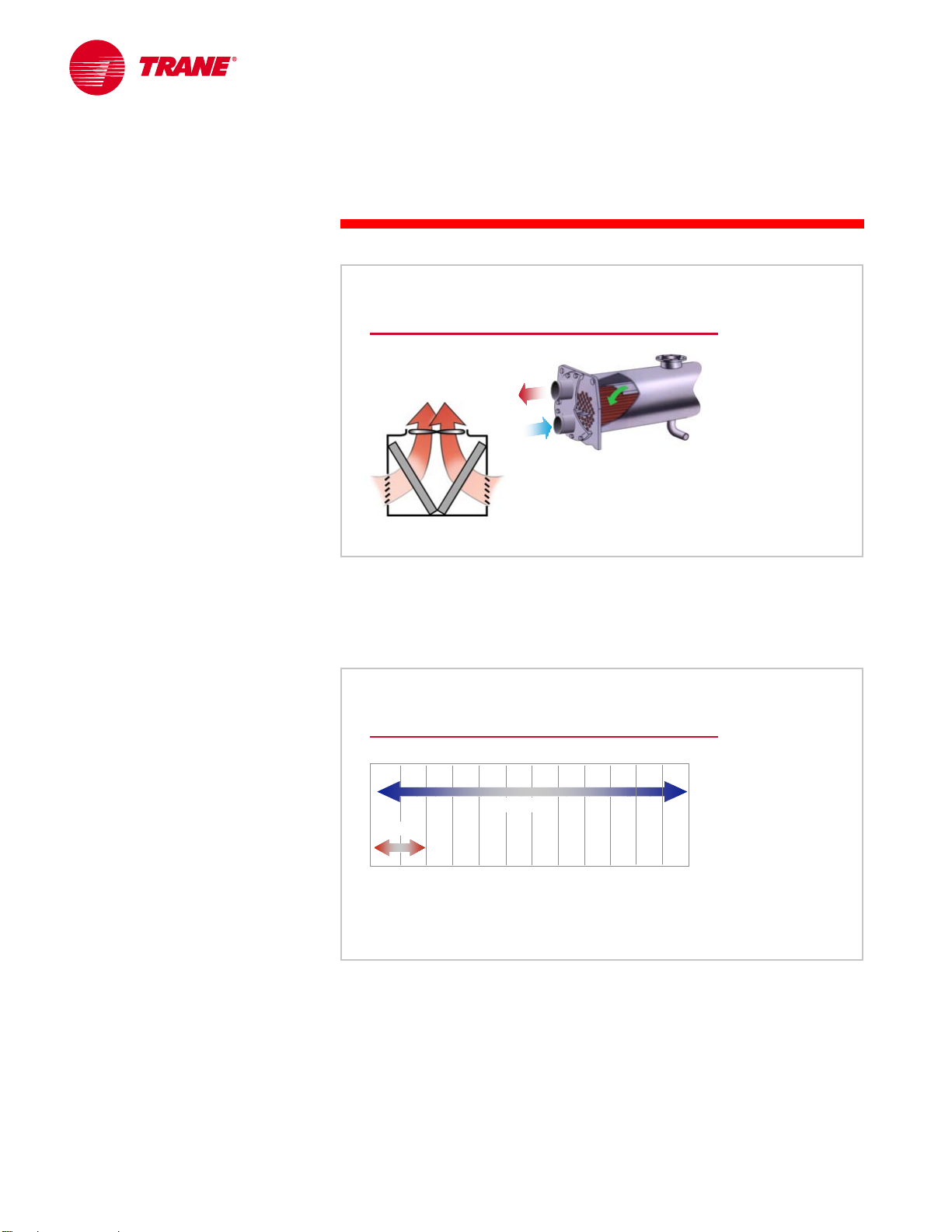

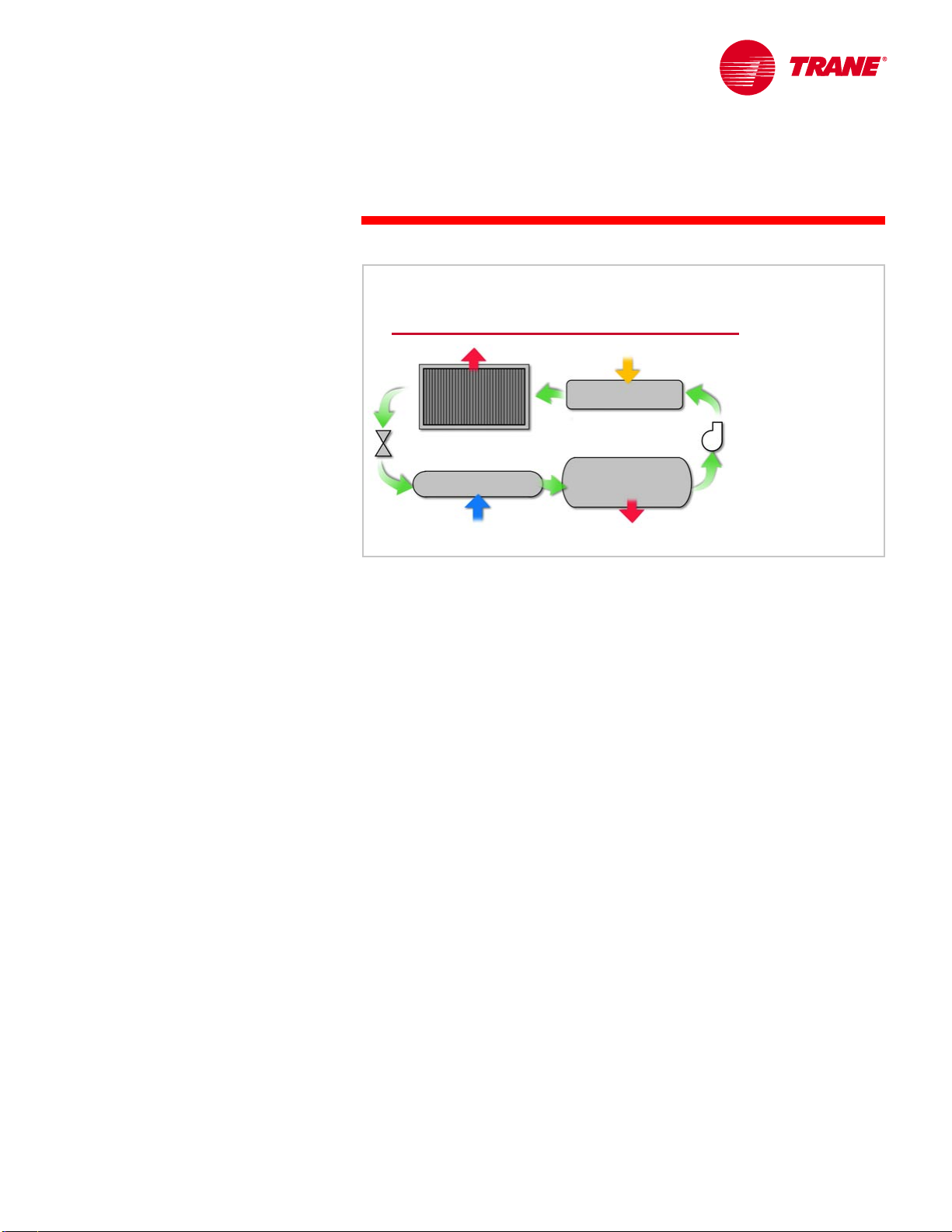

Vapor-Compression Cycle

reject heat

reject heat

expansion

expansion

device

devi ce

D

condenser

condenser

evaporator

A

evaporator

absorb heat

absorb heat

C

compressor

compressor

B

energy in

energy in

Figure 5

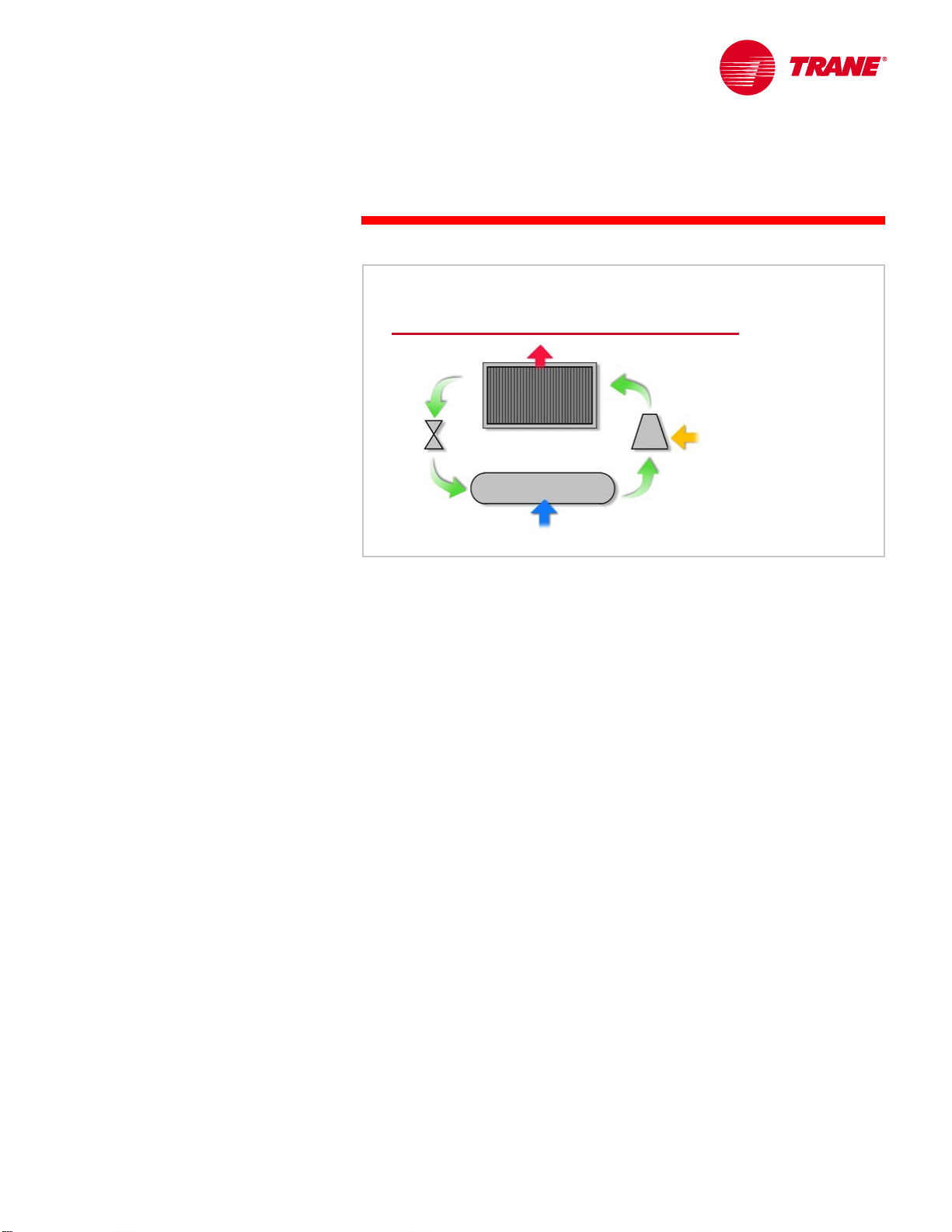

Vapor-Compression Water Chillers

In the vapor-compression refrigeration cycle, refrigerant enters the evaporator

in the form of a cool, low-pressure mixture of liquid and vapor (A). Heat is

transferred from the relatively-warm air or water to the refrigerant, causing

the liquid refrigerant to boil. The resulting vapor (B) is then drawn from the

evaporator by the compressor, which increases the pressure and temperature

of the refrigerant vapor.

The hot, high-pressure refrigerant vapor (C) leaving the compressor enters

the condenser, where heat is transferred to ambient air or water at a lower

temperature. Inside the condenser, the refrigerant vapor condenses into a

liquid. This liquid refrigerant (D) then flows to the expansion device, which

creates a pressure drop that reduces the pressure of the refrigerant to that of

the evaporator. At this low pressure, a small portion of the refrigerant boils

(or flashes), cooling the remaining liquid refrigerant to the desired evaporator

temperature. The cool mixture of liquid and vapor refrigerant (A) travels to the

evaporator to repeat the cycle.

The vapor-compression refrigeration cycle is reviewed in detail in the

Refrigeration Cycle Air Conditioning Clinic.

TRG-TRC016-EN 3

Page 11

notes

period one

Types of Water Chillers

Compressor Types

scroll

reciprocating

helical-rotary

The type of compressor used generally has the greatest impact on the efficiency

and reliability of a vapor-compression water chiller. The improvement of

compressor designs and the development of new compressor technologies

have led to more-efficient and -reliable water chillers.

The reciprocating compressor was the workhorse of the small chiller market

for many years. It was typically available in capacities up to 100 tons [350 kW].

Multiple compressors were often installed in a single chiller to provide chiller

capacities of up to 200 tons [700 kW].

Scroll compressors have emerged as a popular alternative to reciprocating

compressors, and are generally available in hermetic configurations in

capacities up to 15 tons [53 kW] for use in water chillers. As with reciprocating

compressors, multiple scroll compressors are often used in a single chiller to

meet larger capacities. In general, scroll compressors are 10 to 15 percent more

efficient than reciprocating compressors and have proven to be very reliable,

primarily because they have approximately 60 percent fewer moving parts than

reciprocating compressors. Reciprocating and scroll compressors are typically

used in smaller water chillers, those less than 200 tons [700 kW].

Helical-rotary (or screw) compressors have been used for many years in

air compression and low-temperature-refrigeration applications. They are now

widely used in medium-sized water chillers, 50 to 500 tons [175 to 1,750 kW].

Like the scroll compressor, helical-rotary compressors have a reliability

advantage due to fewer moving parts, as well as better efficiency than

reciprocating compressors.

centrifugal

Figure 6

Centrifugal compressors have long been used in larger water chillers.

High efficiency, superior reliability, reduced sound levels, and relatively low

cost have contributed to the popularity of the centrifugal chiller. Centrifugal

compressors are generally available in prefabricated chillers from 100 to

3,000 tons [350 to 10,500 kW], and up to 8,500 tons [30,000 kW] as built-up

machines.

4 TRG-TRC016-EN

Page 12

period one

Types of Water Chillers

notes

These various types of compressors are discussed in detail in the Refrigeration

Compressors Air Conditioning Clinic.

Variable-Speed Drives

variable--

variable

speed

speed

drive

drive

Figure 7

The capacity of a centrifugal chiller can be modulated using inlet guide vanes

(IGV) or a combination of IGV and a variable-speed drive (adjustable-frequency

drive, AFD). Variable-speed drives are widely used with fans and pumps, and as

a result of the advancement of microprocessor-based controls for chillers, they

are now being applied to centrifugal water chillers.

Using an AFD with a centrifugal chiller will degrade the chiller’s full-load

efficiency. This can cause an increase in electricity demand or real-time pricing

charges. At the time of peak cooling, such charges can be ten (or more) times

the non-peak charges. Alternatively, an AFD can offer energy savings by

reducing motor speed at low-load conditions, when cooler condenser water

is available. An AFD also controls the inrush current at start-up.

Certain system characteristics favor the application of an adjustable-frequency

drive, including:

n A substantial number of part-load operating hours

n The availability of cooler condenser water

n Chilled-water reset control

Chiller savings using condenser- and chilled-water-temperature reset, however,

should be balanced against the increase in pumping and cooling-tower energy.

This is discussed in Period Four. Performing a comprehensive energy analysis

is the best method of determining whether an adjustable-frequency drive is

desirable. It is important to use actual utility costs, not a “combined” cost, for

demand and consumption charges.

Depending on the application, it may make sense to use the additional money

that would be needed to purchase an AFD to purchase a more efficient chiller

instead. This is especially true if demand charges are significant.

TRG-TRC016-EN 5

Page 13

notes

period one

Types of Water Chillers

Condenser Types

air-cooled

water-cooled

Figure 8

Air-Cooled or Water-Cooled Condensing

The heat exchangers in the water chiller (the condenser and evaporator) have

the second greatest impact on chiller efficiency and cost. One of the most

distinctive differences in chiller heat exchangers continues to be the type of

condenser selected—air-cooled versus water-cooled.

Air-Cooled or Water-Cooled

wat er--

cooled

wat er

cooled

air--

cooled

air

cooled

0 tons

0 tons

[0 kW]

[0 kW]

500 tons

500 tons

[1,759 k W]

[1,759 kW]

1,000 tons

1,000 tons

[3,517 kW]

[3,517 kW]

1,500 tons

1,500 t ons

[5,276 k W]

[5,276 k W]

chiller capacity

chiller capacity

2,000 t ons

2,000 t ons

[7,034 k W]

[7,034 k W]

When comparing air-cooled and water-cooled chillers, available capacity is the

first distinguishing characteristic. Air-cooled chillers are typically available in

packaged chillers ranging from 7.5 to 500 tons [25 to 1,580 kW]. Packaged

water-cooled chillers are typically available from 10 to 3,000 tons [35 to

10,500 kW].

2,500 t ons

2,500 t ons

[8,793 k W]

[8,793 k W]

3,000 tons

3,000 t ons

[10,551 kW]

[10,551 kW]

Figure 9

6 TRG-TRC016-EN

Page 14

notes

period one

Types of Water Chillers

air-cooled or water-cooled

Maintenance

▲ Water treatment

▲ Condenser tube brushing

▲ Tower maintenance

▲ Freeze protection

▲ Makeup water

cooling tower

cooling tower

A major advantage of using an air-cooled chiller is the elimination of the cooling

tower. This eliminates the concerns and maintenance requirements associated

with water treatment, chiller condenser-tube cleaning, tower mechanical

maintenance, freeze protection, and the availability and quality of makeup

water. This reduced maintenance requirement is particularly attractive to

building owners because it can substantially reduce operating costs.

Figure 10

Systems that use an open cooling tower must have a water treatment program.

Lack of tower-water treatment results in contaminants such as bacteria and

algae. Fouled or corroded tubes can reduce chiller efficiency and lead to

premature equipment failure.

TRG-TRC016-EN 7

Page 15

notes

period one

Types of Water Chillers

air-cooled or water-cooled

Low Ambient Operation

air--

cooled

air

cool ed

chiller

chiller

Figure 11

Air-cooled chillers are often selected for use in systems that require year-round

cooling requirements that cannot be met with an airside economizer. Air-cooled

condensers have the ability to operate in below-freezing weather, and can do so

without the problems associated with operating the cooling tower in these

conditions. Cooling towers may require special control sequences, basin

heaters, or even an indoor sump for safe operation in freezing weather.

For process applications, such as computer centers that require cooling yearround, this ability alone often dictates the use of air-cooled chillers.

8 TRG-TRC016-EN

Page 16

notes

period one

Types of Water Chillers

air-cooled or water-cooled

Efficiency

dry bulb

dry bulb

wet bul b

wet bul b

outdoor temperature

outdoor temperature

12

12

midnight

midnight

Water-cooled chillers are typically more energy efficient than air-cooled chillers.

The refrigerant condensing temperature in an air-cooled chiller is dependent

on the ambient dry-bulb temperature. The condensing temperature in a

water-cooled chiller is dependent on the condenser-water temperature, which

is dependent on the ambient wet-bulb temperature. Since the wet-bulb

temperature is often significantly lower than the dry-bulb temperature, the

refrigerant condensing temperature (and pressure) in a water-cooled chiller

can be lower than in an air-cooled chiller. For example, at an outdoor design

condition of 95°F [35°C] dry-bulb temperature, 78°F [25.6°C] wet-bulb

temperature, a cooling tower delivers 85°F [29.4°C] water to the water-cooled

condenser. This results in a refrigerant condensing temperature of

approximately 100°F [37.8°C]. At these same outdoor conditions, the refrigerant

condensing temperature in an air-cooled condenser is approximately 125°F

[51.7°C]. A lower condensing temperature, and therefore a lower condensing

pressure, means that the compressor needs to do less work and consumes

less energy.

This efficiency advantage may lessen at part-load conditions because the

dry-bulb temperature tends to drop faster than the wet-bulb temperature

(see Figure 12). As a result, the air-cooled chiller may benefit from greater

condenser relief.

Additionally, the efficiency advantage of a water-cooled chiller is much less

when the additional cooling tower and condenser pump energy costs are

considered. Performing a comprehensive energy analysis is the best method

of estimating the operating-cost difference between air-cooled and water-cooled

systems.

12

12

noon

noon

12

12

midnight

midnight

Figure 12

TRG-TRC016-EN 9

Page 17

notes

period one

Types of Water Chillers

air-cooled or water-cooled

Comparison

air-cooled

▲ Lower maintenance

▲ Packaged system

▲ Better low-ambient

operation

Another advantage of an air-cooled chiller is its delivery as a “packaged

system.” Reduced design time, simplified installation, higher reliability, and

single-source responsibility are all factors that make the factory packaging of

the condenser, compressor, and evaporator a major benefit. A water-cooled

chiller has the additional requirements of condenser-water piping, pump,

cooling tower, and associated controls.

Water-cooled chillers typically last longer than air-cooled chillers. This

difference is due to the fact that the air-cooled chiller is installed outdoors,

whereas the water-cooled chiller is installed indoors. Also, using water as the

condensing fluid allows the water-cooled chiller to operate at lower pressures

than the air-cooled chiller. In general, air-cooled chillers last 15 to 20 years, while

water-cooled chillers last 20 to 30 years.

To summarize the comparison of air-cooled and water-cooled chillers, air-cooled

chiller advantages include lower maintenance costs, a prepackaged system for

easier design and installation, and better low-ambient operation. Water-cooled

chiller advantages include greater energy efficiency (at least at design

conditions) and longer equipment life.

water-cooled

▲ Greater energy efficiency

▲ Longer equipment life

Figure 13

10 TRG-TRC016-EN

Page 18

notes

period one

Types of Water Chillers

Packaged Air-Cooled Chiller

air-cooled chill er

Figure 14

Packaged or Split Components

Water-cooled chillers are rarely installed with separable components. Air-cooled

chillers, however, offer the flexibility of separating the components in different

physical locations. This flexibility allows the system design engineer to place

the components where they best serve the available space, acoustic, and

maintenance requirements of the customer.

A packaged air-cooled chiller has all of the refrigeration components

(compressor, condenser, expansion device, and evaporator) located outdoors.

A major advantage of this configuration is factory assembly and testing of all

chiller components, including the wiring, refrigerant piping, and controls.

This eliminates field labor and often results in faster installation and improved

system reliability. Additionally, all noise-generating components (compressors

and condenser fans) are located outdoors, easing indoor noise concerns.

Finally, indoor equipment-room space requirements are minimized.

TRG-TRC016-EN 11

Page 19

notes

period one

Types of Water Chillers

Remote Evaporator Barrel

condensing unit

condensing unit

remote

evaporator

refrigerant

piping

Figure 15

An alternative to the packaged air-cooled chiller is to use a packaged

condensing unit (condenser and compressor) located outdoors, with a remote

evaporator barrel located in the indoor equipment room. The two components

are connected with field-installed refrigerant piping. This configuration locates

the part of the system that is susceptible to freezing (evaporator) indoors and

the noise-generating components (compressors and condenser fans) outdoors.

This usually eliminates any requirement to protect the chilled-water loop from

freezing during cold weather.

This configuration is particularly popular in schools and other institutional

applications, primarily due to reduced seasonal maintenance for freeze

protection. A drawback of splitting the components is the requirement for

field-installed refrigerant piping. The possibility of system contamination

and leaks increases when field-installed piping and brazing are required.

Additionally, longer design time is generally required for the proper selection,

sizing, and installation of this split system.

12 TRG-TRC016-EN

Page 20

notes

period one

Types of Water Chillers

Remote Air-Cooled Condenser

air--

cool ed

air

cooled

condenser

condenser

refrigerant

ref riger ant

piping

piping

condenserless

condenserless

chiller

chiller

Figure 16

Another popular configuration is to use an outdoor air-cooled condenser

connected to a packaged compressor and evaporator unit (also called a

condenserless chiller) that is located in the indoor equipment room. Again,

the components are connected with field-installed refrigerant piping.

The primary advantage of this configuration is that the compressors are located

indoors, which makes maintenance easier during inclement weather and

virtually eliminates the concern of refrigerant migrating to the compressors

during cold weather.

TRG-TRC016-EN 13

Page 21

notes

period one

Types of Water Chillers

Indoor Air-Cooled Condenser

indoor

indoor

air--

cooled

air

cooled

condenser

condenser

refrigerant

refr igerant

pipi ng

piping

condenserless

condenserless

chiller

chiller

The final configuration includes a packaged compressor-and-evaporator unit

that is located in an indoor equipment room and connected to an indoor,

air-cooled condenser. The air used for condensing is ducted from outdoors,

through the condenser coil, and rejected either outdoors or inside the building

as a means for heat recovery. Indoor condensers typically use a centrifugal fan

to overcome the duct static-pressure losses, rather than the propeller fans used

in conventional outdoor air-cooled condensers. Again, the components are

connected with field-installed refrigerant piping.

Figure 17

This configuration is typically used where an outdoor condenser is

architecturally undesirable, where the system is located on a middle floor of a

multistory building, or where vandalism to exterior equipment is a problem.

A disadvantage of this configuration is that it typically increases condenser fan

energy within compared to a conventional outdoor air-cooled condenser.

Similarly, a packaged cooling tower in a water-cooled system can also be

located indoors. This configuration also requires outdoor air to be ducted to

and from the cooling tower, and again, typically requires the use of a centrifugal

fan. Centrifugal fans use about twice as much energy as a propeller fan, but can

overcome the static-pressure losses due to the ductwork. Alternatively, the

tower sump can be located indoors, making freeze protection easier.

14 TRG-TRC016-EN

Page 22

notes

period one

Types of Water Chillers

Absorption Refrigeration Cycle

reject heat

reject heat

D

expansion

expansion

device

device

A

condenser

condenser

evaporator

evaporator

absorb heat

absorb heat

C

B

Absorption Water Chillers

So far, we have discussed water chillers that use the vapor-compression

refrigeration cycle. Absorption water chillers are a proven alternative to vaporcompression chillers. The absorption refrigeration cycle uses heat energy as the

primary driving force. The heat may be supplied either in the form of steam or

hot water (indirect-fired), or by burning oil or natural gas (direct-fired).

There are two fundamental differences between the absorption refrigeration

cycle and the vapor-compression refrigeration cycle. The first is that the

compressor is replaced by an absorber, pump, and generator. The second is

that, in addition to the refrigerant, the absorption refrigeration cycle uses a

secondary fluid called the absorbent. The condenser, expansion device, and

evaporator sections, however, are similar.

Warm, high-pressure liquid refrigerant (D) passes through the expansion

device and enters the evaporator in the form of a cool, low-pressure mixture of

liquid and vapor (A). Heat is transferred from the relatively-warm system water

to the refrigerant, causing the liquid refrigerant to boil. Using an analogy of the

vapor-compression cycle, the absorber acts like the suction side of the

compressor—it draws in the refrigerant vapor (B) to mix with the absorbent.

The pump acts like the compression process itself—it pushes the mixture of

refrigerant and absorbent up to the high-pressure side of the system. The

generator acts like the discharge of the compressor—it delivers the refrigerant

vapor (C) to the rest of the system.

generator

generator

absorber

absorber

heat energy i n

heat energy in

pump

pump

reject heat

reject heat

Figure 18

The refrigerant vapor (C) leaving the generator enters the condenser, where

heat is transferred to cooling-tower water at a lower temperature, causing the

refrigerant vapor to condense into a liquid. This high-pressure liquid refrigerant

(D) then flows to the expansion device, which creates a pressure drop that

reduces the pressure of the refrigerant to that of the evaporator, repeating

the cycle.

The absorption refrigeration cycle is discussed in more detail in the Absorption

Water Chillers Air Conditioning Clinic.

TRG-TRC016-EN 15

Page 23

notes

period one

Types of Water Chillers

Absorption Chillers Offer Choice

▲ Avoid high electric

demand charges

▲ Minimal electricity

needed during

emergency situations

▲ Waste heat recovery

▲ Cogeneration

Figure 19

Absorption water chillers generally have a higher first cost than vaporcompression chillers. The cost difference is due to the additional heat-transfer

tubes required in the absorber and generator(s), the solution heat exchangers,

and the cost of the absorbent. This initial cost premium is often justified when

electric demand charges or real-time electricity prices are a significant portion

of the electric utility bill. Because electric demand charges are often highest at

the same time as peak cooling requirements, absorption chillers are often

selected as peaking or demand-limiting chillers.

Because the absorption chiller uses only a small amount of electricity, backupgenerator capacity requirements may be significantly lower with absorption

chillers than with electrically-driven chillers. This makes absorption chillers

attractive in applications requiring emergency cooling, assuming the alternate

energy source is available.

Some facilities, such as hospitals or factories, may have excess steam or hot

water as a result of normal operations. Other processes, such as a gas turbine,

generate waste steam or some other waste gas that can be burned. In such

applications, this otherwise wasted energy can be used to fuel an

absorption chiller.

Finally, cogeneration systems often use absorption chillers as a part of their

total energy approach to supplying electricity in addition to comfort cooling

and heating.

16 TRG-TRC016-EN

Page 24

notes

period one

Types of Water Chillers

Absorption Chiller Types

single-effect

There are three basic types of absorption chillers. They are typically available

in capacities ranging from 100 to 1,600 tons [350 to 5,600 kW].

Indirect-fired, single-effect absorption chillers operate on low-pressure

steam (approximately 15 psig [205 kPa]) or medium-temperature liquids

(approximately 270°F [132°C]), and have a coefficient of performance (COP) of

0.6 to 0.8. In many applications, waste heat from process loads, cogeneration

plants, or excess boiler capacity provides the steam to drive a single-effect

chiller. In these applications, absorption chillers become conservation devices

and are typically base-loaded. This means that they run as the lead chiller to

make use of the “free” energy that might otherwise be wasted.

Indirect-fired, double-effect absorption chillers require medium-pressure

steam (approximately 115 psig [894 kPa]) or high-temperature liquids

(approximately 370°F [188°C]) to operate and, therefore, typically require

dedicated boilers. Typical COPs for these chillers are 0.9 to 1.2.

The direct-fired absorption chiller includes an integral burner, rather than

relying on an external heat source. Common fuels used to fire the burner are

natural gas, fuel oil, or liquid petroleum. Additionally, combination burners are

available that can switch from one fuel to another. Typical COPs for direct-fired,

double-effect chillers are 0.9 to 1.1 (based on the higher heating value of the

fuel). Higher energy efficiency and elimination of the boiler are largely

responsible for the increasing interest in direct-fired absorption chillers. These

types of absorption chillers have the added capability to produce hot water for

heating. Thus, these “chiller–heaters” can be configured to produce both chilled

water and hot water simultaneously. In certain applications this flexibility

eliminates, or significantly down-sizes, the boilers.

double-effect

direct-fired

Figure 20

TRG-TRC016-EN 17

Page 25

notes

period one

Types of Water Chillers

Equipment Rating Standards

▲ Air-Conditioning &

Refrigeration Institute (ARI)

◆ Standard 550/590–1998:

centrifugal and helical-rotary

water chillers

◆ Standard 560–1992:

absorption water chillers

Figure 21

Equipment Rating Standards

The Air-Conditioning & Refrigeration Institute (ARI) establishes rating standards

for packaged HVAC equipment. ARI also certifies and labels equipment through

programs that involve random testing of a manufacturer’s equipment to verify

published performance. These equipment rating standards have been

developed to aid engineers in comparing similar equipment from different

manufacturers. Chiller full-load efficiency is described in terms of kW/ton and

coefficient of performance (COP). Additionally, two efficiency values developed

by ARI that are receiving increased attention are the Integrated Part-Load

Value (IPLV) and Non-Standard Part-Load Value (NPLV).

ARI’s part-load efficiency rating system establishes a single number to estimate

both the full- and part-load performance of a stand-alone chiller. As part of ARI

Standard 550/590–1998, Water-Chilling Packages Using the Vapor-Compression

Refrigeration Cycle, and ARI Standard 560–1992, Absorption Water Chilling-

Heating Packages, chiller manufacturers may now certify their chiller part-load

performance using the IPLV and NPLV methods. This gives the engineering

community an easy and certified method to evaluate individual chillers.

Understanding the scope and application limits of IPLV and NPLV is, however,

crucial to their validity as system performance indicators.

18 TRG-TRC016-EN

Page 26

notes

period one

Types of Water Chillers

Part-Load Efficiency Rating

▲ Integrated Part-Load Value (IPLV)

◆ Weighted-average load curves

◆ Based on an “average” single-chiller installation

◆ Standard operating conditions

▲ Non-Standard Part-Load Value (NPLV)

◆ Weighted-average load curves

◆ Based on an “average” single-chiller installation

◆ Non-standard operating conditions

Figure 22

The IPLV predicts chiller efficiency at the ARI standard rating conditions, using

weighted-average load curves that represent a broad range of geographic

locations, building types, and operating-hour scenarios, both with and without

an airside economizer. The NPLV uses the same methods to predict chiller

efficiency at non-standard rating conditions. Although these weighted-average

load curves place greater emphasis on the part-load operation of an average,

single-chiller installation, they will not—by definition—represent any

particular installation.

Additionally, ARI notes that more than 80 percent of all chillers are installed in

multiple-chiller systems. Chillers in these systems exhibit different unloading

characteristics than the IPLV weighted formula indicates. Appendix D of

Standard 550/590–1998 explains this further:

The IPLV equations and procedure are intended to provide a singlenumber, part-load performance number for water-chilling products.

The equation was derived to provide a representation of the average

part-load efficiency for a single chiller only. However, it is best to use a

comprehensive analysis that reflects the actual weather data, building

load characteristics, operational hours, economizer capabilities, and

energy drawn by auxiliaries, such as pumps and cooling towers, when

calculating the chiller and system efficiency.

Here is the important part:

This becomes increasingly important with multiple-chiller systems

because individual chillers operating within multiple-chiller systems

are more heavily loaded than single chillers within single-chiller

systems.

TRG-TRC016-EN 19

Page 27

notes

period one

Types of Water Chillers

Standard Rating Conditions

chiller type

vapor-compression

• reciprocating

•scroll

• helical-rotary

• centrifugal

absorption

• single-effect

• double-effect,

indirect-fired

• double-effect,

direct-fired

water leaving evaporator = 44°F [6.7°C]

water entering condenser = 85°F [29.4°C]

evaporator

flow rate

2.4 gpm/ton

[0.043 L/s/kW]

2.4 gpm/ton

[0.043 L/s/kW]

2.4 gpm/ton

[0.043 L/s/kW]

condenser

flow rate

3.0 gpm/ton

[0.054 L/s/kW]

3.6 gpm/ton

[0.065 L/s/kW]

4.0 gpm/ton

[0.072 L/s/kW]

4.5 gpm/ton

[0.081 L/s/kW]

The standard rating conditions used for ARI certification represent a particular

set of design temperatures and flow rates for which water-cooled and air-cooled

systems may be designed. They are not suggestions for good design practice

for a given system—they simply define a common rating point to aid

comparisons.

rating

standard

ARI

550/590–1998

ARI

560–1992

Figure 23

In fact, concerns toward improved humidity control and energy efficiency have

changed some of the design trends for specific applications. More commonly,

chilled-water systems are being designed with lower chilled-water

temperatures and lower flow rates. The water flow rate required through the

system is decreased by allowing a larger temperature difference through the

chiller.

20 TRG-TRC016-EN

Page 28

notes

period one

Types of Water Chillers

Flow Rates and Temperatures

Q

Btu/hr

[ Q

W

The temperature difference (∆T) through the chiller and the water flow rate are

related. For a given load, as the flow rate is reduced, the ∆T increases, and vice

versa.

Q 500 flow rate ∆T××=

Q 4,184 flow rate ∆T××=[]

where,

n Q = load, Btu/hr [W]

n flow rate = water flow rate through the chiller, gpm [L/s]

n ∆T = temperature difference (leaving minus entering) through the chiller,

ºF [°C]

Realize that 500 [4,184] is not a constant! It is the product of density, specific

heat, and a conversion factor for time. The properties of water at conditions

typically found in an HVAC system result in this value. Other fluids, such as

mixtures of water and antifreeze, will cause this factor to change.

Density of water = 8.33 lb/gal [1.0 kg/L]

= 500 × flow rate ×∆∆∆∆T

= 4,184 × flow rate ×∆T ]

equation for water only

Figure 24

Specific heat of water = 1.0 Btu/lb°F [4,184 J/kg°K]

8.33 lb/gal 1.0 Btu/lb° F 60 min/hr 500=××

1.0 kg/L 4,184 J/kg° K4,184=×[]

TRG-TRC016-EN 21

Page 29

notes

period one

Types of Water Chillers

Flow Rates and Temperatures

95°F

95°F

[35°C]

[35°C]

85°F

85°F

[29.4°C]

[29.4°C]

54°F

54°F

[12.2°C]

[12.2°C]

ARI conditions

evaporator

flow rate

condenser

flow rate

2.4 gpm/ton

[0.043 L/s/kW]

3.0 gpm/ton

[0.054 L/s/kW]

44°F

44°F

[6.7°C]

[6.7°C]

100°F

100°F

[37.8°C]

[37.8°C]

85°F

85°F

[29.4°C]

[29.4°C]

57°F

57°F

[13.9°C]

[13.9°C]

low-flow conditions

evaporator

flow rate

condenser

flow rate

1.5 gpm/ton

[0.027 L/s/kW]

2.0 gpm/ton

[0.036 L/s/kW]

In the example system shown in Figure 25, the chilled water is cooled from 57°F

[13.9°C] to 41°F [5°C] for a 16°F [8.9°C] ∆T. This reduces the water flow rate

required from 2.4 gpm/ton [0.043 L/s/kW] to 1.5 gpm/ton [0.027 L/s/kW].

41°F

41°F

[5°C]

[5°C]

Figure 25

Reducing water flow rates either: 1) lowers system installed costs by reducing

pipe, pump, valve, and cooling tower sizes, or 2) lowers system operating costs

by using smaller pumps and smaller cooling tower fans. In some cases, both

installed and operating costs can be saved. Low-flow systems will be discussed

in more detail in Period Three.

The two ARI rating standards mentioned previously, as well as ASHRAE/IESNA

Standard 90.1–1999 (the energy standard), allow reduced chilled-water

temperatures and flow rates. System design engineers should examine the use

of reduced flow rates to offer value to building owners.

22 TRG-TRC016-EN

Page 30

notes

period one

Types of Water Chillers

ASHRAE/IESNA Standard 90.1–1999

▲ Energy Standard

◆ Building design and

materials

◆ Minimum equipment

efficiencies

◆ HVAC system design

Figure 26

ASHRAE/IESNA Standard 90.1–1999, Energy Standard for Buildings, Except

Low-Rise Residential Buildings, went into effect in October 1999. ASHRAE

is the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning

Engineers and IESNA is the Illuminating Engineering Society of North America.

This standard addresses all aspects of buildings except low-rise residential

buildings. It contains specific requirements for both water chillers and

chilled-water systems.

standard 90.1-1999 efficiency requirements

Electric Vapor-Compression Chillers

chiller type

chiller type

air cool ed

air cool ed

water-cool ed

water-cool ed

recipr ocating

recipr ocating

heli cal-rotar y, scroll

heli cal-rotar y, scroll

centri fugal

centri fugal

* as of October 29, 200 1

* as of October 29, 200 1

Standard 90.1 contains minimum full- and part-load efficiency requirements

for packaged water chillers. The table in Figure 27 is an excerpt from Table

6.2.1C of Addendum J to the standard. It includes the minimum efficiency

requirements for electric vapor-compression chillers operating at standard ARI

conditions. The standard also contains tables of minimum efficiency

requirements for these chillers operating at nonstandard conditions. The test

procedure for these chillers is ARI Standard 550/590–1999. Notice that these

requirements go into effect on October 29, 2001.

TRG-TRC016-EN 23

capacity

capacity

all capacit ies

all capacit ies

all capacit ies

all capacit ies

< 150 tons [ 528 kW]

< 150 tons [ 528 kW]

150 to 300 tons [528 t o 1,056 kW]

150 to 300 tons [528 t o 1,056 kW]

> 300 tons [1,056 kW]

> 300 tons [1,056 kW]

< 150 tons [ 528 kW]

< 150 tons [ 528 kW]

150 to 300 tons [528 t o 1,056 kW]

150 to 300 tons [528 t o 1,056 kW]

> 300 tons [1,056 kW]

> 300 tons [1,056 kW]

minimum efficiency*

minimum efficiency*

2.8 COP 3.05 IPLV

2.8 COP 3.05 IPLV

4.2 COP 5.05 IPLV

4.2 COP 5.05 IPLV

4.45 COP 5.2 IPLV

4.45 COP 5.2 IPLV

4.9 COP 5.6 IPLV

4.9 COP 5.6 IPLV

5.5 COP 6.15 IPLV

5.5 COP 6.15 IPLV

5.0 COP 5.25 IPLV

5.0 COP 5.25 IPLV

5.55 COP 5.9 IPLV

5.55 COP 5.9 IPLV

6.1 COP 6.4 IPLV

6.1 COP 6.4 IPLV

Figure 27

Page 31

period one

Types of Water Chillers

notes

Note: Addendum J updates the minimum IPLV efficiency requirements in the

standard to match the methods included in the most current version of the ARI

rating standard. At the time this booklet was printed, Addendum J had not been

formally adopted as part of the standard. However, its adoption was deemed

sure enough to include in this publication.

The standard requires that both full- and part-load conditions be met. For

example, the efficiency of a water-cooled centrifugal chiller with a capacity

greater than 300 tons [1,056 kW] must be 6.1 COP, or better, at ARI standard

conditions. This is equivalent to 0.576 kW/ton. The part-load (IPLV) efficiency

must also be 6.4 (based on the efficiency units of COP) or better. This is

equivalent to an IPLV of 0.549 kW/ton.

Coefficient of performance (COP) is a unitless expression of efficiency, defined

as useful energy out divided by energy input. A higher COP designates a higher

efficiency.

kW/ton

standard 90.1-1999 efficiency requirements

3.516

-------------- -=

COP

Water-Cooled Absorption Chillers

chiller type

chiller type

singl e-effect

singl e-effect

capacity

capacity

all capacities

all capacities

minimum efficiency*

minimum efficiency*

0.7 COP

0.7 COP

double-ef fect

double-ef fect

indi rect-f ired

indi rect-f ired

direct -fi red

direct -fi red

* as of Oc tober 29, 2001

* as of Oc tober 29, 2001

all capacities

all capacities

all capacities

all capacities

1.0 COP 1.05 IPLV

1.0 COP 1.05 IPLV

1.0 COP 1.0 IPLV

1.0 COP 1.0 IPLV

Figure 28

The table in Figure 28 includes the minimum efficiency requirements for

absorption water chillers. For an absorption chiller, COP is defined as

evaporator cooling capacity divided by the heat energy required by the

generator, excluding the electrical energy needed to operate the pumps, purge,

and controls.

Again, these minimum efficiency requirements take effect on October 29, 2001.

The test procedure for these chillers is ARI Standard 560–1992. Note that the

efficiency requirement for single-effect absorption chillers is higher than many

manufacturers have offered in the past.

Section 6.3.4 of Standard 90.1 includes additional requirements for the design

and operation of chilled-water systems. These requirements will be mentioned

in later periods.

24 TRG-TRC016-EN

Page 32

notes

period one

Types of Water Chillers

ASHRAE Standard 15–1994

▲ Safety standard for

refrigerating systems

▲ Mechanical equipment

room

◆ Refrigerant monitors

◆ Alarms

◆ Mechanical ventilation

◆ Pressure-relief piping

Figure 29

Another standard that is related to chilled-water systems, ASHRAE Standard

15–1994, Safety Code for Mechanical Refrigeration, is intended to specify

requirements for safe design, construction, installation, and operation of

refrigerating systems. This standard covers mechanical refrigeration systems

of all sizes that use all types of refrigerants. Because absorption chillers use

water as the refrigerant, however, they are exempt from this standard.

For many chilled-water systems in which the chillers are located indoors, the

standard requires the refrigeration equipment to be installed in a mechanicalequipment room. The requirements for this mechanical-equipment room

include refrigerant monitors and alarms, mechanical ventilation, pressure-relief

piping, and so forth.

TRG-TRC016-EN 25

Page 33

notes

period two

Chilled-Water System Design

Chilled-Water Systems

period two

Chilled-Water System Design

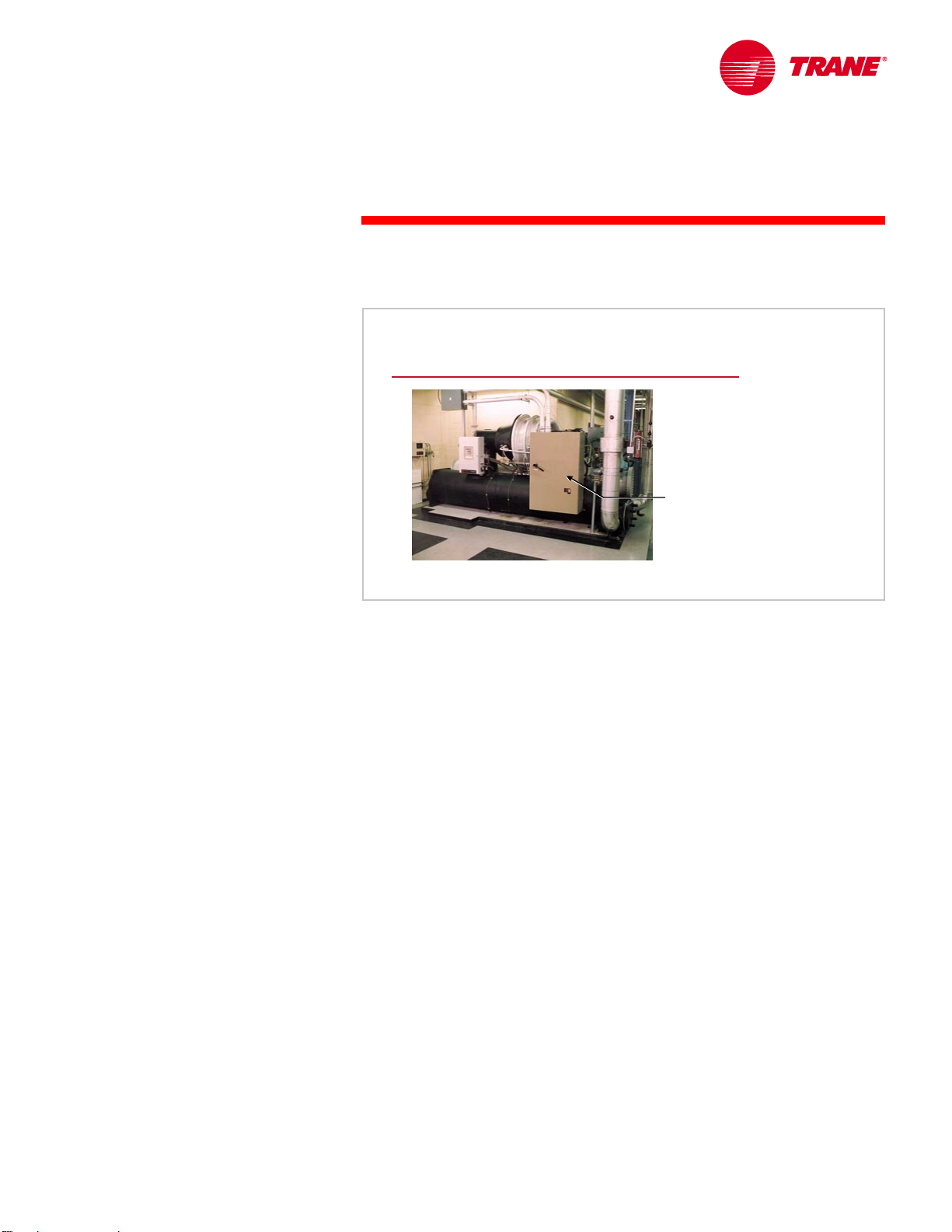

Figure 30

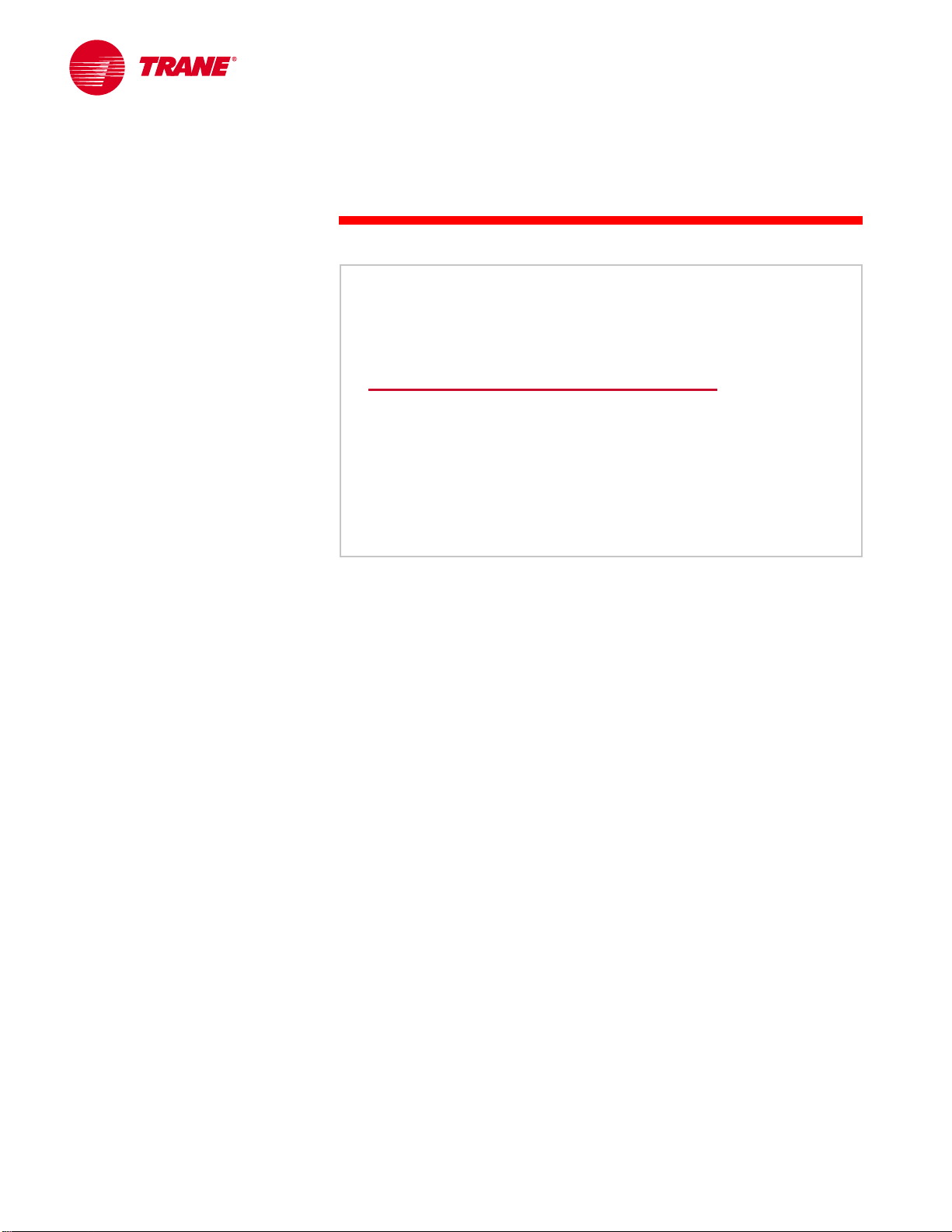

Proper design of a chilled-water system can greatly impact the first cost,

operating costs, and flexibility of the HVAC system. The purpose of this period

is to discuss the design of reliable chilled-water systems.

Chilled-Water System Components

cooling tower

cooling coil

pumps

The conventional chilled-water system consists of combinations of the

following primary components:

n Water chillers

n Load terminals (chilled-water cooling coils in comfort-cooling applications)

n Cooling towers in water-cooled systems

n Chilled- and condenser-water pumps

n Chilled- and condenser-water distribution systems that include piping,

an expansion tank, control valves, check valves, strainers, and so forth.

chiller

Figure 31

26 TRG-TRC016-EN

Page 34

notes

period two

Chilled-Water System Design

Chilled-Water System

air--

cooled

air

cooled

chiller

chiller

coil

pump

pump

control

control

valve

valve

This period focuses on the chilled-water side of the system; that is, the water

that flows through the chiller evaporator and out through the load terminals.

Specifically, we will review methods of load-terminal control and various

multiple-chiller system configurations. These topics apply to systems using

both air-cooled and water-cooled chillers.

coil

Figure 32

Fundamentally, the function of the chilled-water system is to transport the

cooling fluid from the chillers to the load terminals and back to the chillers.

Assuming that the distribution system is adequately sized, we will concentrate

on the hydraulic interaction between the load terminals and the chillers.

TRG-TRC016-EN 27

Page 35

notes

period two

Chilled-Water System Design

Load-Terminal Control Options

▲ Three-way

modulating valve

▲ Two-way

modulating valve

▲ Face-and-bypass

dampers

Figure 33

Load-Terminal Control

The purpose of load-terminal control is to modulate the flow of air or water

through the coil to maintain building space comfort. This is accomplished by

measuring the temperature of the supply air or space. The temperature then

converted to an electronic signal that modulates the capacity of the cooling

coil to match the changing load in the space.

Three methods of load-terminal control are commonly used in

chilled-water systems.

n Three-way modulating valve control

n Two-way modulating valve control

n Face-and-bypass damper control

Each of these methods has a different effect on the operation of the system.

28 TRG-TRC016-EN

Page 36

notes

period two

Chilled-Water System Design

Three-Way Valve Control

airf low

airf low

bypass

three--

way

three

way

modulat ing

mod ul at i ng

valve

valve

A three-way control valve is one method used to regulate the flow of chilled

water through a cooling coil. As the space cooling load decreases, the

modulating valve directs less water through the coil, decreasing its capacity.

The excess water bypasses the coil and mixes downstream with the water that

flows through the coil. As a result, the temperature of the water returning from

the system decreases as the space cooling load decreases.

bypass

pipe

pipe

Figure 34

Systems that use three-way valves have the following characteristics:

n The temperature of the water returning from the system varies as the

cooling load varies.

n The water flow through each load terminal (water through the coil plus

water bypassing the coil) is relatively constant at all load conditions.

n The pump energy is constant at all loads because the use of three-way

valves results in constant water flow throughout the system.

n Water-flow balance is very critical to proper operation because the flow

is constant.

TRG-TRC016-EN 29

Page 37

notes

period two

Chilled-Water System Design

Two-Way Valve Control

air flow

airf low

two--

way

two

modulating valve

modulating val ve

A two-way modulating valve is similar to a three-way valve in that the water

flow through the coil is modulated proportionately to the load. The primary

difference is that the two-way valve does not bypass any unused water, it

simply throttles the amount of water passing through the coil.

The coil and the air being conditioned experience no difference in the cooling

effect of using a two-way versus a three-way valve. The chilled-water system,

however, sees a great difference. Recall that with a three-way valve, the

terminal water flow (water through the coil plus the water bypassing the coil)

is constant at all loads. With a two-way valve, the terminal water flow varies

proportionately with the load. Because there is no mixing of coil and bypassed

water, the temperature of the water leaving the load terminal remains relatively

constant at all conditions. In fact, this return-water temperature may actually

rise slightly as the load decreases, due to coil heat-transfer characteristics.

Systems that use two-way valves have the following characteristics:

way

Figure 35

n The temperature of the water returning from the system is constant

(or increases) as the cooling load decreases. This increases the effectiveness

of options such as heat recovery, free cooling, and base-loading, which will

be discussed further in Period Three.

n The water flow through each load terminal varies proportionately to the

load, resulting in pump energy savings at part load.

n A variable-flow system is less sensitive to water balance than most

constant-flow systems.

A variable-flow, chilled-water distribution system, however, may require

another method to provide constant water flow though the chillers, or else

the chillers must be equipped to handle variable water flow.

30 TRG-TRC016-EN

Page 38

notes

period two

Chilled-Water System Design

Face-and-Bypass Damper Control

bypass

bypass

damper

damper

airf low

airf low

face

face

damper

damper

The final method of modulating the coil capacity to match the cooling load is

through the use of face-and-bypass dampers. A linked set of dampers varies

the amount of air flowing through the coil by diverting the excess air around

the coil. As the cooling load decreases, the face damper closes, reducing the

airflow through the coil and reducing its capacity. At the same time, the linked

bypass damper opens, allowing more air to bypass around the coil. A unique

characteristic of this method of load-terminal control is that the coil is allowed

to “run wild,” meaning that the water flow through the coil is constant.

Figure 36

Similar to the three-way valve, systems that use face-and-bypass dampers have

the following characteristics:

n The temperature of the water returning from the system varies as the

cooling load varies.

n The water flow through each load terminal and, therefore, pump energy are

constant at all load conditions.

An advantage of face-and-bypass control with a “wild” cooling coil is that it can

better dehumidifiy of the conditioned air when compared to varying the water

flow through the coil. As the airflow through the coil decreases at part-load

conditions, assuming that the temperature of the water entering the coil is

constant, the temperature of the air leaving the coil also decreases. That is,

the air is cooled further and more moisture is removed.

TRG-TRC016-EN 31

Page 39

notes

period two

Chilled-Water System Design

Load-Terminal Control Options

▲ Three-way modulating valve

◆ Constant water flow

◆ Variable system return-water temperature

▲ Two-way modulating valve

◆ Variable water flow (pump energy savings)

◆ Constant system return-water temperature

▲ Face-and-bypass dampers

◆ Constant water flow

◆ Variable system return-water temperature

◆ Enhanced dehumidification capability with “wild” coils

Properly designed, operated, and maintained, any of these three methods can

result in good space comfort control. However, they have different effects on

the chilled-water system.

Figure 37

The use of three-way valves or face-and-bypass dampers results in variable

return-water temperature and relatively constant chilled-water flow through

the entire system. The use of two-way valves results in constant return-water

temperature and variable water flow through the entire system. Before

choosing one of these control methods, it is necessary to determine the

effect that it will have on the other parts of the chilled-water system.

Chiller Evaporator Flow

▲ Constant flow is most

common

▲ Variable flow is

possible

◆ Can reduce energy

consumption

evaporator

◆ Use only with

advanced chiller and

system controls

In the past, the water flow rate through the chiller evaporator was to remain

as constant as possible. The vast majority of chilled-water systems employ

pumping schemes that maintain a constant flow rate of water through each

chiller evaporator. Even in the most-carefully-designed chilled-water systems,

however, the flow through the chillers will still vary slightly due to system

evaporator

Figure 38

32 TRG-TRC016-EN

Page 40

period two

Chilled-Water System Design

notes

effects. System effects include pump–system curve interaction, dynamic head

variations, and variation in distribution system flow.

There are benefits to maintaining a constant water flow rate through the chiller

evaporator. Constant flow provides more-stable and-simple chiller and system

operation. However, there is potential for energy savings by varying the water

flow in the distribution system. Applying these two seemingly-conflicting

principles to chilled-water systems requires careful planning and a thorough

understanding of hydraulic system operation.

Due to advances in technology, however, many of today’s chillers can operate

with variable evaporator water flow. Chilled-water systems that are specifically

designed to vary evaporator water flow are discussed in Period Three. This

period focuses on systems that employ constant water flow through the chiller

and either constant or variable water flow through the rest of the distribution

system.

Single-Chiller System

air--

cooled

air

cooled

chiller

chiller

coil

pump

pump

coil

three--

way val ve

three

way valve

Another factor that influences chilled-water system design is the number of

chillers used. Single chillers are sometimes used in small systems (less than

100 tons [35 kW]), while larger or critical systems typically use multiple chillers.

Many single-chiller systems resemble the one shown in Figure 39. This system

uses a single pump to move water through the chiller and load terminals. The

load terminals are controlled using three-way modulating valves. The pump

delivers a constant flow of water throughout the entire system, and flow

balance is relatively easy.

TRG-TRC016-EN 33

Figure 39

Page 41

notes

period two

Chilled-Water System Design

Multiple-Chiller Systems

▲ Redundancy

▲ Part-load efficiency

Figure 40

Multiple-chiller systems are more common than single-chiller systems for the

same reason that most commercial airplanes have more than one engine—

redundancy provides reliability. Additionally, because cooling loads typically

vary widely, multiple-chiller systems can often operate with less than the full

number of chillers. During these part-load periods, the system saves the energy

required to operate the additional chillers, pumps, and, in water-cooled

systems, cooling tower fans.

There are several configurations used to connect multiple chillers in these

systems. Some of these configurations work well, others do not. Next, we will

look at the most-commonly-used system configurations, including their

advantages and drawbacks.

34 TRG-TRC016-EN

Page 42

notes

period two

Chilled-Water System Design

chillers piped in parallel

Single Pump

54°F

54°F

[12.2° C]

off

off

54° F

54° F

[12.2° C]

[12.2 °C]

Parallel Configuration

Parallel piping is one common configuration of multiple-chiller systems.

Figure 41 shows a system that uses a single pump to deliver chilled water both

to chillers and to the system load terminals. This configuration can be used in

systems that use constant-flow methods of terminal control (three-way valves

or face-and-bypass dampers), or in systems that use variable-flow methods of

terminal control (two-way valves). Varying the flow through the load terminals

using two-way valves in this type of system results in variable water flow

through the chiller evaporators. Chilled-water systems that are specifically

designed to vary evaporator water flow will be discussed in Period Three.

This section will focus on systems that use constant-flow methods of

terminal control.

Water is pumped through both chillers continuously, regardless of whether only

one chiller or both chillers are operating. This example system is at 50 percent

load, with one chiller operating and the second chiller off. Return water from the

system at 54°F [12.2°C] continues to flow through the non-operating chiller and

mixes with the chilled 42°F [5.6°C] water produced by the operating chiller. The

resulting mixed-water temperature leaving the plant is 48°F [8.9°C]. This rise in

supply-water temperature may result in problems with building comfort or

humidity control. A chiller-plant controller may be used to reset the set point of

the operating chiller downward, in an attempt to compensate for this condition,

and more-closely maintain the desired supply-water temperature. Reducing the

set point of the operating chiller has its limits, however, depending on the

operating characteristics and evaporator freeze limits of the specific chiller. The

more chillers in the system, the worse the problem becomes. For this reason,

this configuration is seldom used in systems with more than two chillers.

[12.2° C]

42°F

48°F

42°F

48° F

[5.6° C]

[8.9° C]

[5.6° C]

on

on

[8.9°C]

Figure 41

Additionally, ASHRAE/IESNA Standard 90.1–1999 (Section 6.3.4.2) prohibits this

type of system when the pump is larger than 10 hp [7.5 kW]. The standard

requires that, in systems that contain more than one chiller piped in parallel,

system water flow must be reduced when a chiller is not operating.

TRG-TRC016-EN 35

Page 43

notes

period two

Chilled-Water System Design

chillers piped in parallel

Dedicated Pumps

off

off

42° F

42° F

[5.6°C]

on

on

54°F

54°F

[12.2° C]

[12.2° C]

coil st arved for flow

coil starved for flow

If separate, dedicated pumps are used with each chiller, a pump-and-chiller pair

can be turned on and off together as the cooling load varies. This solves the

temperature mixing problem that occurred in the previous, single-pump

configuration, but it presents a new problem in a system that uses a constantflow method of terminal control.

[5.6°C]

60% to 70%

60% to 70%

of system flow

of system flow

Figure 42

Below 50-percent load, only one chiller and one pump are operating. The total

water flow in the system decreases significantly, typically 60 to 70 percent of

full system flow. Ideally, at this part-load flow rate, all of the coils will receive

less water, regardless of their actual need. Typically, however, some coils

receive full water flow and others receive little or no water. In either case,

heavily-loaded coils will usually be “starved” for flow. Examples of spaces

with constant heavy loads that may suffer include computer rooms, conference

rooms, photocopy rooms, and rooms with high solar loads.

36 TRG-TRC016-EN

Page 44

notes

period two

Chilled-Water System Design

chillers piped in parallel

Dedicated Pumps

2 pumps

2 pumps

1 pump

1 pump

head pressure

head pressure

system

system

curve

curve

Figure 43 shows an example of the pump–system curve relationship. When

both pumps are operating, the system receives 100 percent of design flow.

When only one pump is operating, the intersection of the pump’s performance

curve with the system curve results in about 65 percent of design flow.

This configuration also presents problems to chiller operation. The starting or

stopping of a pump for one chiller affects the flow through the other chiller.

Using this same example, if one chiller is operating and a second chiller and

pump are started, the total water flow in the system does not double. The

system and pump performance curves will “rebalance,” resulting in an increase

in system flow of only 35 percent of total flow. The new total flow rate,

however, is now divided equally between the two chillers. This results in a rapid

reduction in water flow through the original operating chiller, from 65 percent of

total system flow to 50 percent. This rapid decrease in flow often results in a

loss of temperature control and may cause the chiller to shut off on a safety.

percent flow

percent flow

65%

65%

100%

100%

Figure 43

In order to overcome this problem, the chiller-plant control system should

anticipate the starting of additional pumps and unload operating chillers prior

to the start of an additional chiller. Again, this configuration is sometimes

acceptable for two-chiller systems, but is not often used in larger systems

because the part-load system flow problems are further multiplied.

TRG-TRC016-EN 37

Page 45

notes

period two

Chilled-Water System Design

Chillers Piped in Series

elect ric

electric

chiller

chiller

absorpti on

absorpti on

chiller

chiller

three--

way val ve

three

way val ve

Figure 44

Series Configuration

Another way to connect multiple chillers is to configure the chiller evaporators

in series. Series chilled-water systems typically use three-way valves at the coils

to ensure constant system flow. With two chillers in series, both the

temperature mixing and the flow problems associated with the parallel

configurations shown previously disappear. All of the chilled water passes

through both chillers, and there is full system-water flow at all loads.

However, the flow rate through each individual chiller is equal to the entire

system flow rate. When compared to chillers piped in parallel at the same

system ∆T, this is twice as much water flowing through each chiller. This means

that the chiller-tube pass arrangement must accommodate double the water

quantity within acceptable velocity and pressure drop limits. This typically

requires a reduced number of passes in the evaporator and may impact chiller

efficiency. This efficiency impact, however, is often offset by the gain in system

efficiency due to thermodynamic staging.

System pressure drop also increases because the pressure drops through the

chillers are additive. This can result in increased pump size and energy costs.

This increase in pumping energy can be substantially reduced by designing the

system for a higher system ∆T and, therefore, a reduced water flow rate.

Because of the pressure drop limitations, it is difficult to apply more than two

chillers in series. Systems involving three or more chillers typically use either

the primary-secondary configuration or parallel sets of two chillers in series.

38 TRG-TRC016-EN

Page 46

notes

period two

Chilled-Water System Design

chillers piped in series

Equal Set Points

42° F

42°F

[5.6° C]

[5.6° C]

42°F

42° F

[5.6° C]

[5.6° C]

Figure 45

54°F

54° F

[12.2° C]

[12.2° C]

set point =

set point =

42° F

42° F

[5.6° C]

[5.6° C]

48°F

48°F

[8.9° C]

[8.9° C]

set poi nt =

set point =

Temperature control in a series system can be accomplished in several ways,

depending on the desired operating sequence. The first method, shown in

Figure 45, has both set points adjusted to the desired system supply-water

temperature. Assuming equally-sized chillers, either chiller can meet the load

below 50 percent. Above 50-percent load, both chillers operate and the

upstream chiller is preferentially loaded. This means that the upstream chiller is

operated at full capacity and any portion of the load that remains is handled by

the downstream chiller.

This strategy may be desirable in systems that benefit from preferentially

loading the upstream chiller. Examples include:

n Using a heat-recovery chiller in the upstream position. Because the chiller is

at full capacity whenever the system load exceeds 50 percent, the amount of

heat available for recovery is maximized.

n Using an absorption chiller in the upstream position. An absorption chiller

works more efficiently, and has a higher cooling capacity, with higher

leaving-chilled-water temperatures. The absorption chiller in the upstream

position provides a warmer leaving-chilled-water temperature at design

conditions, 48°F [8.9°C] in this example. This arrangement preferentially

loads the gas-burning absorption chiller, allowing the system to maximize

the use of a lower-cost fuel during periods of high electrical-energy cost.

Alternatively, equal loading of the two chillers in series can be accomplished

using a chiller-plant control system to monitor system load and balance chiller

loading. The set point for the downstream chiller is set equal to the desired

system supply-water temperature, and the set point for the upstream chiller is

then dynamically reset to maintain equal loading on both chillers. The control

system must be stable enough to prevent control hunting or chiller cycling

during periods of changing load.

TRG-TRC016-EN 39

Page 47

notes

period two

Chilled-Water System Design

chillers piped in series

Staggered Set Points

42° F

42°F

[5.6° C]

[5.6° C]

42°F

42° F

[5.6° C]

[5.6° C]

Figure 46

52°F

52° F

[11.1° C]

[11.1° C]

set point =

set point =

48° F

48° F

[8.9° C]

[8.9° C]

48°F

48°F

[8.9° C]

[8.9° C]

set poi nt =

set point =

An alternative method of controlling chillers in series involves staggering the

set points of the two chillers. This results in the downstream chiller operating

first and being preferentially loaded. Any portion of the load that the

downstream chiller cannot meet is handled by the upstream chiller.

The example in Figure 46 shows the system operating at about 80 percent of

design cooling load. As we mentioned earlier, with three-way valves at the

coils, the temperature of the water returning to the chillers decreases at part

load. At 80-percent load, the return-water temperature is 52°F [11.1°C], instead

of the 54°F [12.2°C] at 100-percent load. The upstream chiller is partially loaded,

cooling the water to the 48°F [8.9°C] set point, while the downstream chiller

remains fully loaded, cooling the water the rest of the way to 42°F [5.6°C].

40 TRG-TRC016-EN

Page 48

notes

period two

Chilled-Water System Design

Primary-Secondary Configuration

producti on

producti on

pumps

pumps

distribut ion

dist ribution

e

e

p

p

i

i

p

p

s

s

s

s

a

a

p

p

y

y

b

two--

two

b

way valve

way valve

producti on

producti on

loop

loop

dis tri bution

distribut ion

loop

loop

Primary-Secondary (Decoupled) Configuration

If the water flow through the chillers (production) could be hydraulically

isolated from the water flow through the coils (distribution), many of the

problems encountered in parallel and series configurations could be

eliminated.

pump

pump

Figure 47

Figure 47 shows a configuration that separates, or “decouples,” the production

capacity from the distribution load. This scheme is known as a primary-

secondary system, also referred to as a decoupled system. This

configuration is unique because it dedicates separate pumps to the

“production” and “distribution” loops. A bypass pipe that connects the supply

and return pipes is the key component in decoupling the system.

The chillers in the production loop receive a constant flow of water, while the

coils in the distribution loop, controlled by two-way modulating valves, receive

a variable flow of water.

TRG-TRC016-EN 41

Page 49

notes

period two

Chilled-Water System Design

Primary-Secondary System Rules

▲ The bypass pipe should be free of restrictions

◆ Sized for minimal pressure drop

◆ Avoid random mixing of supply- and return-water

streams

◆ No check valve

Figure 48

The bypass pipe is common to both production and distribution loops.

The purpose of the bypass pipe is to hydraulically decouple the production

(primary) and distribution (secondary) pumps. Because water can flow freely

between the supply and return pipes for both loops, a change in flow in one

loop does not affect the flow in the other loop.

The actual extent of hydraulic decoupling depends on the pressure drop due to

the bypass pipe. Total decoupling is accomplished only if the bypass pipe is free