Microsoft Forza Motorsport 2 User Manual

Lim ite d C oLL eCt or’ s e dit ion

http://www.replacementdocs.com

http://www.replacementdocs.com

Lim ite d C oLL eCt or’ s e dit ion

0207 Part No. X12-87636-01

TAB LE OF C ONT EN TS

Welcome ........................................................................ 2

The Vision

An Interview with Lead Designer Dan Greenawalt ....................................3

Car Manufacturers ........................................................ 18

The Art

An Interview with Art Director John Wendl ............................................71

A Sampling from the Stable .......................................... 80

The Sounds

An Interview with Audio Lead Greg Shaw ............................................108

Real-World Tracks ......................................................... 114

Racing School .............................................................

Turn Types ...........................................................................................129

Basic Turn Strategy ..............................................................................132

Braking and Cornering .........................................................................133

Managing Weight Transfer ..................................................................138

Coping with Understeer and Oversteer.................................................142

Professional Insights

An Interview with Racing Driver Gunnar Jeannette ...............................148

Industry Credits .......................................................... 152

Team Credits ............................................................... 155

126

All trademarks, trade dress, design patents, copyrights, and logos are the property of their respective owners.

All rights reserved.

© & p 2007 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.

Microsoft, Forza Motorsport, Halo, Midtown Madness, the Microsoft Game Studios logo, OptiMatch, PGR, Project

Gotham Racing, Turn 10, Xbox, Xbox 360, Xbox LIVE, the Xbox logos, and/or other Microsoft products referenced

herein are trademarks of the Microsoft group of companies.

Uses Bink Video. Copyright © 1997–2007 by RAD Game Tools, Inc.

ForzaMotorsport.net

.

Welcome

WE LCO ME

TH E V IS ION

Welcome to the Forza Motorsport™ 2 Limited Collector’s Edition, your passport

to the world of automobile racing, both simulated and real.

Forza Motorsport 2 players have two things in common: a passion for cars and

racing, and a consuming desire to win, and this book is designed to feed that

passion. In its pages you will:

Get a behind-the-scenes look at what went into the making of the most

detailed and immersive racing simulation to date.

Find a wealth of information on the cars and tracks you can experience in

Forza Motorsport 2.

Learn about racing techniques that can fuel your success in Forza

Motorsport 2.

An Interview with Lead Designer

Dan Greenawalt

Lead Designer Dan Greenawalt is the keeper of

the vision for the Forza Motorsport franchise. In

this revealing interview Dan takes you behind the

scenes for a better understanding of that vision,

and of the physics that underlie this extraordinarily

realistic auto racing simulation. From the tire

physics that determine whether your car will stay

stuck to the road or spin off the course, to his

views on the automotive playground he is creating

and constantly improving, to his emphasis on the

joy of driving and his plans for the future of Forza

Motorsport, this interview provides an intriguing

look into the world behind the game.

“I envision Forza

Motorsport as the

place where car lovers

can gather to talk and

argue about cars they

like and racing they’re

interested in. I want

to bring people with

this passion together

regardless of their

other differences.

My goal for the

Forza Motorsport

franchise is broad

and inclusive.”

The Vision

Th e V is ion

Q: What are the physics behind the Forza Motorsport 2

racing simulator? What are the components of real-world

racing you had to re-create?

We spent a ton of time working on the physics. We used a lot of sources, but

especially Milliken & Milliken’s Race Car Vehicle Dynamics, a very reputable

source on vehicle dynamics and tuning, with the graphs and the math as

well as general theory. It’s used a lot, not only for racing sims, but also by

racing engineers. It was the single biggest influence for us; it became the

way we spoke.

We made a technology demo with five meticulously researched cars to

prove our physics engine. In many ways we were just trying to see what we

could do. We poured six months into that demo, and the results were really

incredible. There were no licensing agreements at this point, so we had cars

rolling over, taking heinous damage, shedding parts—but you’ve got to make

some allowances when you have agreements with fifty different premium car

manufacturers. It was an all-star team of guys who had all been involved in one

racing franchise or another—Rally Sport Challenge, Project Gotham Racing®,

or Midtown Madness®. The physics was where we were at our purest, and I

haven’t seen many simulations that match the accuracy of Forza Motorsport.

Q: So you slowly moved away from an entirely purist

approach to an emphasis more on game design

and gameplay.

I love physics, and I like working on that aspect of the game in particular.

While we were working on the demo, I was also working on the vision and the

“pillars”—the features—that support that vision. I had to flesh it out from the

top down. We all threw features at the wall to see what would stick. I worked

to pull it all together and create a cohesive game design. We repeated this

process for six months to get our vision honed. Not just the vision for Forza

Motorsport version one, but for the franchise. This helped me get a better

vision of where I want us to be in six or ten years—the game I want Forza

Motorsport version six to be. This sort of forethought allows us to start planting

little road signs in the game, minor features we could develop over time into

major ones.

Q: It sounds like your vision of the user experience shifted

over time to become an online multiplayer experience,

much more involved in version two.

In many ways, Project Gotham Racing and Forza Motorsport are brother and

sister products. We share technology; but more than anything, we share a

charter to keep pushing the bounds of online play. Microsoft in general and

our teams in particular believe that online play is where gaming is at today.

We also believe that the most influential innovations in this genre are going to

come in the online space. Our goal every time Project Gotham Racing or Forza

Motorsport ships a new version is to make sure it just keeps getting better

and better. We pushed the boundaries in the original Forza Motorsport; no

game had so many scoreboards. We write to multiple scoreboards at once; no

one had ever done that, and we had a seamless online to single-player Career

mode. At the Xbox 360™ launch, Project Gotham Racing 3 (PGR® 3) came

out with even more fantastic online features, like Spectator mode. Now we’re

pushing the boundaries again with our Auction House, tournaments, and

other new features. I really want to get us to a new way of experiencing racing

games in the future, so we’ve got to keep making forward progress.

The Vision

Th e V is ion

Q: Tire simulation is a big part of the physics model, and

people don’t usually focus on that in racing games. What

did you learn in trying to develop a realistic tire formula?

We tried different tire models after our “green light” demo. We kept tuning

the physics model, finding bugs, and working on it. New cars exposed new

issues. We had two basic ways of expressing the tire physics. The traditional

way that simulation racing games do this is Pacejka’s Magic Formula—no joke,

that’s what it’s called. It’s got a whole slew of variables you tune and input,

and it spits out friction values. But the cars didn’t control the way we wanted

and the results didn’t mesh with a lot of our real-world data. I’ve had enough

experience tuning with that formula that I can feel it at work when I play some

racing simulations. It’s not quite right, but it’s close. Toyo put me in contact

with their tire engineers. It was hard to understand the data they were giving

me, and I had to ask a lot of questions, but they slowly brought me up to

speed to where I could understand what their graphs and data were saying.

Pacejka’s formula is close, and really good in most situations, but not all, and

not for transitions between states. It just doesn’t feel right.

So we went to what could best be described as a table system. We have a table

that linearly interpolates between the curves we have for different weights, tire

pressures, and other variables. It’s a very big, computationally difficult system.

That’s what was nice about Pacejka’s formula when we were using it—it’s

very lightweight, where our approach is extremely heavy. That’s why in Forza

Motorsport, drifting, for example, is very real and very responsive. Drifting is

all about weight transition, and you can control it with your throttle in Forza

Motorsport because in our model the movement between those curves is very

smooth and precise. We spent a lot of time getting it right. The tire model

is amazing, but there are always things to improve. There are things in our

physics model I’ll want to improve forever.

Forza Motorsport 2 is a simulation, not a complete emulation—no one has

ever done that, no matter what they claim. We can’t completely emulate tire

technology until the scientists learn it, and they haven’t learned it all yet. Tires

do some funky things. They’ve got load sensitivity, which involves nonNewtonian physics. A tire with a coefficient of friction of 1.0 at 500 kg actually

develops a smaller coefficient of friction at 1,000 kg. With 500 kg on the tire,

it might require a value of 500 kg force to push it. But with a 1,000 kg load, it

might require a value of 800 kg force to push it. Understanding this is huge in

understanding how tires function. It’s a big deal to simulate this, though few

people know about it. When I told the tire engineers, they were amazed we

were doing it.

Q: Please elaborate on why tires are so important in

racing. Why do most people give more thought to parts

upgrades than to tires?

People tend to take their tires for granted; you see the tires on your car every

day. But turbochargers and computer-controlled fuel injection systems are

like alien technology to many folks—they’re high tech and people don’t see

them every day. People think they understand everything about tires, and

unfortunately tires are the part of the car they usually understand least.

Tire compounds are really crazy. We were at an American Le Mans Series

(ALMS) race in Portland, Oregon, under very hot conditions, and saw how tires

have a huge impact on racing. The science behind tire technology is always

changing. We can get amazing performance out of tires, and the tires of today

are much better than tires even just five years ago. That extreme rate of rapid

iteration doesn’t happen with turbos or many other engine technologies.

Your car talks to the road through four little tire contact patches, and it’s how

you manage those patches that makes everything work. After the ALMS race

the manager of the winning team said the only reasons they won were their

drivers and their tires, that both really came through in the heat.

The tires have many layers, all of which are meant to react to heat, torque, and

force in various ways. If they do what they’re supposed to do, they create the

The Vision

Th e V is ion

necessary coefficient of friction. When you start twisting that contact patch

the tire winds up like a spring and gives you the slip angle required to hit peak

friction. Doing that is a very complex process. It’s interesting that different tire

compounds, like a Y-rated tire, or a DOT-spec tire, or a racing tire, have very

different characteristics. You look at them—they’re just some rubber on a rim.

It’s not just the tread that gives tires their characteristics. Tread quality is

essential, but it mostly comes down to the composition and construction of

the tire. How sticky it is, how it reacts to heat, how the sidewalls flex, all make

a huge difference.

Q: Is there ever a reason not to use sticky tires?

As someone who tracks his car, I can tell you that sticky is more expensive to

buy and that you’re going to go through them faster because they’re softer,

so you have to buy more of them. They also generally react badly to high heat.

In that hot ALMS race, most teams were running on their hardest-compound

tires. Because of the heat, those hard tires were getting soft and losing rubber,

leaving “marbles” all over the track. On a cool day you would go with a softer

compound and might only have to pit, say, once an hour. On a hot day you’d

go with your hardest compound, and might also have to pit at the same rate.

If you had stuck with the soft tires on that hot day, you might have had to

pit twice as often. Also, on a hot day the softer tires might blister and fail. In

Forza Motorsport, tire pressure increases as the tires heat up. This changes the

contact patches and tire friction, and affects your handling.

Q: What is the process of tuning more than 300 cars to

make them feel right?

We use roughly 9,000 individual variables just to define the physics for a single

car—not including the tires, but for the variables that define the car and its

upgrade parts (from spring rates, damping bump and rebound, to weight,

aerodynamics, and so on). Even race cars that can’t be upgraded involve 5,000

numeric values to define each car.

It all started when we were figuring out and iterating on the physics, and I was

trying to determine whether there were patterns. We were reading Milliken

& Milliken as well as other vehicle dynamics books and trying to identify how

the cars relate to each other. Basically, we were developing a math model for

tuning the cars. The hardest thing is, you can’t find, for example, spring rate

data for all 300 cars. You’re lucky if you can get it for 20% of them, from the

manufacturers and from research. Sometimes you can get that kind of data

on fan Web sites, which can be freaky that way. Sometimes we contacted

the spring manufacturers, not the car manufacturers. The manufacturers we

contacted were based on the continuum of all of the cars, so we could get

a really even spread of data on low-end cars to high-end cars to race cars,

finding out about progressive springs versus linear springs, and so on.

Then we looked at ride height, the weight of the car, and what we call the

“goodness rating,” from reading reviews and learning a lot about each car.

We ranked the cars based on their “goodness,” and arranged those values

into buckets. For example, we might put a Ford Focus SVT a little lower than

a Subaru WRX STi. When we set the spring rates for those cars, and we don’t

have the actual spring rates for them, we use a formula, a mathematical model,

to automatically tune those numbers for us. Then we put in critical damping,

and offset damping with “goodness,” ranking cars by region. A lot of this we

call “automagic”—it’s our voodoo magic that we do in the game, and it’s the

only thing that makes it possible to tune 9,000 numbers on 300 cars.

The Vision

Th e V is ion

Proving that this automagic model could work to tune the cars was a big part

of our getting the green light for version one. And there’s a ton of testing that

goes on. We list and graph the numbers we get, looking for anomalies, and

then we test the cars by hand. For example, one may come out with a really

loose spring rate. Sometimes we find that our formula isn’t taking weight

distribution into account as well as it should. Then we rework the formula,

reexport all the cars’ values, and retest. That’s a lot of systems—engine systems,

such as turbo pressure, rpm, inertia, and so on. Some things we get to research

a lot, like all of our stock turbo pressures. We went through and tested them,

and made sure that they were in the right stack rank relative to each other and

that their results in the game matched our research and knowledgebase.

Q: For the original Forza Motorsport, racing driver Gunnar

Jeanette made some suggestions about cars he had

driven, and you were able to change some numbers on

the fly to make the car more realistic. Is that something

you’re doing for Forza Motorsport 2?

There are two sides to it. Some of the cars drive the way they do because it’s

completely predictable. You look at the car’s behavior and it’s easy to see why

it behaves that way. If it understeers and you see that it’s front-weighted with

no downforce, all the tires are the same size and its spring rate is tighter on

the front, obviously it’s going to understeer. In a front-drive car with 60% of

the weight on the front wheels, it’s just physics that the car will understeer. So

there are a whole bunch of characteristics people comment on—“You really got

that right!” I say, “We didn’t have to get it right—the physics got it right!”

Q: So we’re really talking about hand tuning.

After the automagic has done its thing, then you go in and hand tune.

For instance, getting the nuances of the suspension right is less about oversteer

and understeer and more about controlling the car with the throttle through

a turn; how getting onto, off of, and back onto the brakes creates oversteer;

how braking and throttle techniques affect the car. We’ve got a really good

team—guys who are rally drivers, guys who have driven all kinds of cars. So

we start tuning that way. But inevitably there are cars no one on the team has

driven, like the Lancia Stratos. We had trouble finding reviews on it; we just

knew it was a famous rally car, but our physics got a ton of that stuff right.

You start putting in the weight distribution, the size of the car, its moment of

inertia, and it starts getting better and better.

Q: How do you handle implementing upgrades? When does

the upgrade variable come in?

Some of the upgrade variables are researched heavily in order to create the

model. The issue is that our Level 3 upgrades are full racing upgrades, as if

you had a million dollars to burn, which very few people have, especially on

a lower-class car. No one is going to spend so much upgrading cars like that,

so we have some cars people don’t race much, and have no idea how much

power that engine can really make. So we have to use some math and our

model to figure it out. The car has a certain displacement and configuration,

it’s a certain size, has a certain rpm redline and top speed, and we take all

those things and put them together and come up with what we think is its

theoretical maximum torque and horsepower. But believe me, gas velocity out

of the valves and headers can be a real pain to estimate.

The Vision

Th e V is ion

Q: Since you have to account for things you can’t find in

reality but that can exist in the sim, are there times

when the potential for so many car modifications seems

too crazy and unbelievable even though the math says

the model is right?

When I was developing the franchise vision, I hit on the idea early that this is

an automotive playground, a sandbox. We could have gone the route of

a super-credible, licensed parts catalogue. We could have said, “Exactly what

parts really are available for, say, the Mark II GTI? Oh, these parts are available

in the real world—okay, then that’s exactly what the player will get—no

more and hopefully no less. It’s sort of limiting for cars that for one reason or

another have never gotten a lot of race R&D in the real world.

Also, we could have exposed the player to the money pit and no-win situations

that define tuning in the real world. One turbo is more reliable; one has better

low-end spool-up. Why use this suspension part instead of that one? One is

better at low-speed bump compression and the other is better at high-speed

bump compression. Which one is better? Neither, but one is more expensive.

That’s real tuning. That’s what I’ve got to do on my own car. That’s why my

“check engine” light is always on for one reason or another and my fenders rub

during track days.

I want to make this a sandbox or playground where people can safely

experiment. I want to invite people in and teach them a ton of things, but not

require them to already know it all. If we throw them into the deep weeds

and expect them to already know everything there is to know about cars and

upgrades, most won’t even know where to start. I didn’t feel it would be

very inviting. Moreover, it wouldn’t be as good a place for people to learn. If

you buy a car that in the real world doesn’t have many upgrade options or a

tuning community, we’d have to say, “Sorry, this car doesn’t get any substantial

upgrades.” It’s not that parts couldn’t be made for those cars; there simply

isn’t demand for them in the real world.

What we want to do is make it all about real-world potential: “Hey man, if you

had three million dollars and really like a particular car, you can go ahead and

upgrade it. We’ll do the legwork to make sure the results are plausible and

rooted in real science.” This makes our upgrade system a really cool playground

where people can learn about cars and upgrades.

Q: Someone in the Forza Motorsport community tuned an

Integra to go over 250 mph, so I guess in the sandbox

it’s theoretically possible?

It’s hard to know. We simulated cars driving on an open plane at their top

speed and tried with gearing to match theoretical top speed in our database.

In some cases we ended up tuning drag coefficient and driveline losses quite a

bit. What’s important to me is that we really do our homework, really do our

math to figure it all out, so if you see it in the Forza Motorsport games, it really

is possible.

Q: So it’s a balance between the sandbox element and also

being credible.

It’s all about being credible. It’s whether or not our math shows it could be

done in the real world given time, money, and expertise. We look at the math

and say, “Wait a minute—with that frontal area and drag, you need this much

power to put enough torque onto the ground to reach that speed”—it’s

mathematical. Sometimes I don’t believe our results and we have to test them.

Sometimes we have to rework the system to provide better results.

The Vision

Th e V is ion

Q: What do you think people responded best to in the

original Forza Motorsport?

First and foremost, Forza Motorsport is a fantastic simulator. The thing we

really did well was the thing we had to do well, the thing we’re always going

to have to do well: create a fun, deep, and rewarding driving experience.

We had to create an experience that was fun to drive and easy to get into

while maintaining a deep and rewarding path to mastery. You pick up Forza

Motorsport and if you’re not really good at it, you can use driving assists. We

don’t dumb the physics down; we bring the player up using assists. Players can

start turning them off one by one as they advance down the path to mastery.

I want Forza Motorsport to have all the depth of a great sim, but I also want

people to be able to play it. Once you start turning the assists off, you can

start expressing yourself in your driving, the way you can in the real world. You

can be really fast, you can drift, you can be stylish, and you can recover when

you start to screw up. Once you get skilled at the game, it no longer feels

like a razor-thin edge, where if you get any yaw going in your car—goodbye,

you’re out of here. You can start playing with the physics and making the car

obey your every command. In the real world it all comes down to sensitivity

and timing. You see a guy like Juan Pablo Montoya in a car with racing slicks.

Racing slicks are the most intolerant tires there are, and he can still get the

car’s back end out a little bit and whip it back in and not spin out because

he can feel it and he’s on it instantly. You can do that in Forza Motorsport.

We can build a game around the player’s path of mastery, but at heart Forza

Motorsport is a fantastic simulator, and it’s a fun simulator.

Q: Now that version two is wrapped up, as the visionary,

what do you see down the road for the Forza

Motorsport franchise?

We’ve only built a small percentage of the game I see in my head. In some

instances, the technology isn’t there yet. In others, we just haven’t had time to

fully realize the experience I’m chasing. As before, we’ve made little road signs

about what’s coming in the future. In a lot of ways it’s about experimentation.

We try little bits of things to see how people react, whether people have fun

and maybe even learn a thing or two. It’s one thing to design something and

proclaim, “People are going to love this!” It’s another thing to put a little bit

out there and ask, “How does this taste?” Give them a little sample. It’s a

chance for me to watch them. People say they like a feature or don’t like it.

Players are rarely good at articulating what they like or don’t like, but they are

spot on at identifying whether or not they are having a good time. To learn

what they’re really feeling and enjoying, it’s important to watch them, watch

how they play. They might say, “Oh, I’m really frustrated with this!” But they’re

smiling. Or they might say, “I’m really enjoying that,” but it looks like they’re

fidgeting, like they want to leave. Often there is some other aspect of the

experience that they do not perceive that is having a greater effect than what

they identify. It’s our job to sniff that out.

Q: So you’re going to be perfecting that fun-to-drive

experience for every version of the game?

What I’m trying to capture is the joy of being a race car driver and sports car

enthusiast, not the experience of having to pay for fuel, pay for tires, blow

your engine, get scammed by a shady tuner, and so on. We don’t want to

simulate the struggle to get a ride with a team, because that’s not the joy

of driving. There are people who may want that game, but that’s not what

this game is about. This game is about the joy of collecting, customizing,

and driving amazing cars and learning how to get good at it. We don’t just

dumb the physics down. We let the player experience the car in its full glory

and supplement their skills with powerful assists. We’ve got to build a game

that grabs people. Where car collecting, car upgrading, car customization,

car owning, car trading, and living in a community and interacting with other

people are all great things to do. At any moment you can go in there and have

a great experience. I want to get gamers excited about cars, and car people

excited about games.

The Vision

Th e V is ion

Q: So the game is really built around the core experience—

the joy of driving.

The driving experience is definitely the core mechanic of the game—it’s what

we had to get right. However, at the heart of the vision, the grain that got this

whole thing growing is “car lust,” a passion for cars. That’s what sprouted

the simulation, sprouted the upgrades and customization, what sprouted this

community. Everything came from that. So simulation is the core mechanic,

but it’s not the seed of the game. The seed is that emotional response you have

when you see an amazing car on the street. That’s car lust.

Q: Can you give us a hint of what you’re thinking about for

Forza Motorsport 3? What would you like to add to the

experience that will significantly change it?

For me the future of gaming is all about pushing online and community.

Online gaming plays to that seed, that car lust, but not everyone is good at

driving. Having car lust doesn’t mean you have a big bank account, doesn’t

mean you’re a male, doesn’t mean you’re good at driving, doesn’t mean

you’re a dexterous gamer with fast reactions. That nugget of car lust is way

more universal. It’s shared by a lot of people in all walks of life. So for me, the

future is about getting more people who share car lust to experience the game;

bringing them together to play. They don’t all have to be driving; they can be

doing different things to be part of the community. They can be equally valued

in the community if we give them the right tools. Even if I like muscle cars and

you like European cars, we’ve still got something to talk about. You may be

more dexterous, a really good sim racer. Maybe I’m not so good at it. But let’s

say I’m really good at painting, or tuning, or strategizing, or getting people

together in a community. There are a lot of skills you can use to be part of the

Forza Motorsport community. It’s all about giving a diverse group of people

brought together by “car lust” the tools they need to add value in

the community.

Q: So races are won by collaborative effort?

My goal is to look at the kinds of things people can be good at. If they have

that car lust, they can find ways to be successful and rewarded and valued in

the community. While in a lot of ways this resembles a racing team, I’m not

interested in simulating a racing team per se. What I want is for someone

who isn’t necessarily a great gamer but who loves cars, to feel they should be

playing Forza Motorsport to connect with other car lovers. When a new car

comes out and people read about it, they should be able to drive it in

our simulation.

I envision Forza Motorsport as the place where car lovers can gather to talk

and argue about cars they like and racing they’re interested in. I want to bring

people with this passion together regardless of their other differences. My goal

for the Forza Motorsport franchise is broad and inclusive.

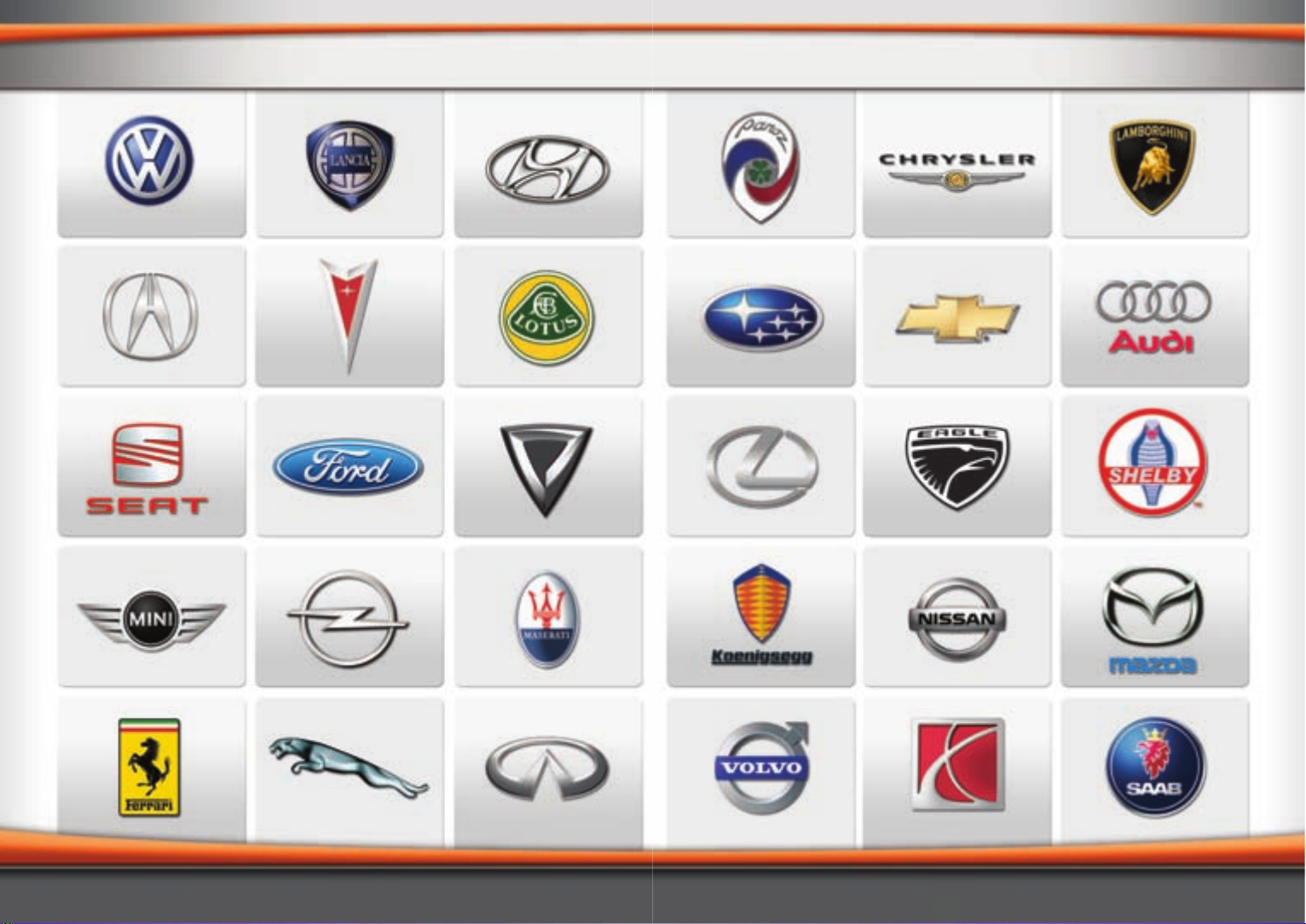

CA R M AN UFAC TU RER S

Car Manufacturers

2

Ca r M an ufaC tu rer s

AC URA

In creating a very large stable of cars for our players, the Forza Motorsport

team has worked with fifty car manufacturers from all over the world. Each

manufacturer has a history of its own, and each has made its contribution to the

evolution of the automobile.

In this section of the Forza Motorsport 2 Limited Collector’s Edition book you will

learn about the following automobile manufacturers:

Acura

Aston Martin

Audi

Bentley

BMW Motorsport

Buick

Cadillac

Chevrolet

Chrysler

Dodge

Eagle

Ferrari

Ford

Honda

Hyundai

Infiniti

Jaguar

Koenigsegg

Lamborghini

Lancia

Lexus

Lotus

Maserati

Mazda

McLaren

Mercedes-Benz

MINI

Mitsubishi

Nissan

Opel

Pagani

Panoz

Peugeot

Plymouth

Pontiac

Porsche

Proto Motors

Renault

Saab

Saleen

Saturn

Scion

SEAT

Shelby

Subaru

Toyota

TVR

Vauxhall

Volkswagen

Volvo

In 1986, Honda Motor Co. of Japan started producing the Acura line of cars

for several markets, including the U.S., becoming the first of three Japanese

manufacturers to launch separate luxury brands. The first Acura models—the

Legend, Integra, and especially the avant-garde NSX—set the tone for the new

brand, with a dual emphasis on luxury and performance. The late Formula One

champion Ayrton Senna consulted on the NSX’s suspension and chassis

tuning, and the car was both a stunning performer and suitable for everyday

street driving.

Acura also produced some very desirable special models with an extra emphasis

on performance. The 195-hp Integra Type-R features a race-tuned suspension,

high-performance tires, powerful brakes, and special seats. The NSX-R, introduced

in 1992 for Japan and Europe and updated in 2002, is a lightened version of

this already super car. Its 290-hp V6, aggressive suspension, and improved

aerodynamics allow it to compete successfully against more powerful cars.

2001 Acura Integra Type-R

Car Manufacturers

2

AS TON M ARTIN

AU DI

This British manufacturer of hand-crafted high-performance sports cars was

founded in 1914. After early competition successes (the Aston name was derived

from an English hillclimb course), Aston Martin focused on racing during the

1920s and 1930s. In 1947, Aston Martin was acquired by David Brown Limited,

which launched the long line of “DB” high-performance sports cars for which the

company is best known. The series began with a few examples of the Two Litre

Sports/DB1 in 1948 and the DB2 in 1950. Racing versions of the Aston Martin

sports cars achieved great racing success during the 1950s, culminating in a

first-place finish at the Le Mans 24-hour road race in 1959.

In the 1960s, Aston Martin decided to concentrate on road car production,

creating perhaps its most famous car, the DB5, in 1963. This sports car began

a long relationship with secret agent James Bond after appearing in the film

Goldfinger in 1964, and gained the company and its cars many new admirers.

The DB line of sports cars continues to this day, with the award-winning DB9.

Aston Martin returned to motor racing in 2005 with a racing version, the DBR9.

The current three-car lineup also includes the V8 Vantage and the Vanquish S.

August Horch, who founded a car company under his own name in 1899, started

Audi (the Latin translation of Horch) in 1909. Early Audis were luxurious, and

also had some competition success. In 1932, four German car companies (Audi,

Horch, DKW, and Wanderer) merged to form Auto Union; the four linked rings

of the current Audi logo represent the four companies. Along with racers from

Mercedes-Benz, mid-engine Auto Union race cars designed by Ferdinand Porsche

dominated motor racing in the 1930s.

In 1964, Volkswagen acquired the company and revived the Audi name. The car

that launched Audi’s modern reputation as a technology leader and maker of

advanced, competitive cars was the four-wheel drive Audi quattro in 1980. The

Group B racing version of the Audi 200 quattro dominated the TransAm series

in 1988, and sent competitors back to the drawing board. Audi’s popular A4, A6,

and A8 series cars first appeared in 1996. The high-performance all-wheel-drive

S-series versions of these cars have been successful in amateur competition, and

Audi’s Le Mans Prototype race cars have played a dominant role at the top level

of motor racing, led by the 550-hp R8, which won the 24 Hours of Le Mans three

times in a row. In 2006, Audi introduced its latest Le Mans Prototype, the Dieselpowered R10 TDI, which won in its first outing at the Twelve Hours of Sebring, as

well at the 2006 24 Hours of Le Mans.

2001 Aston Martin Vanquish

2006 Audi RS 4

Car Manufacturers

2

BE NTL EY

BM W M OT ORS PO RT

W. O. Bentley founded this legendary British marque in 1919, and decided to

prove and promote his cars through competition. In 1924 a 3-liter, 4-cylinder

Sport model won Bentley’s first victory at Le Mans. In 1926–1927, Bentley

introduced the 6.5-liter Speed Six and the sportiest Bentley, the 4.5-liter 4cylinder. This was Bentley’s golden age, with four consecutive Le Mans wins

in 1927–1930 shared among the three models. The drivers, who came to

be called “The Bentley Boys,” were amateur sportsmen who drove fast and

lived glamorously. Their big, British racing green Bentleys stood out for both

performance and size, dwarfing most continental racers. Ettore Bugatti compared

them to trucks, commenting that Bentley built “the world’s fastest lorries,” but

Bentleys quickly built a reputation as the world’s best sports cars.

With the Great Depression Bentley sales plummeted and in 1931 the company

was sold to Rolls-Royce. For many years most Bentleys were Rolls-Royces with a

different radiator shell. One major exception was the 1952 R Type Continental,

a beautiful 120-mph, four-seat fastback that still turns heads today. In the late

1980s, Bentleys again emphasized performance with turbocharged power and

roadholding to match. This transformation continued in 1998 when German

manufacturer Volkswagen bought Bentley and invested heavily in new models.

After a seventy-one-year lapse Bentley returned to racing with the Speed 8 Le

Mans Prototype, taking third place in 2001, second place in 2002, and winning

a sixth Le Mans victory in 2003.

German automobile and motorcycle manufacturer BMW (the Bavarian Motor

Works) began as a manufacturer of aircraft engines during the First World War,

so the BMW logo, a roundel of alternating blue and white quadrants, represents

a whirling aircraft propeller. The company produced its first car in 1927. By the

late 1930s, BMW was building two pre-war classics, the 327 sedan and the

328 roadster.

After WWII BMW resumed automobile production in 1952, and produced the

legendary 507 sports car in 1957. During the 1960s, BMW launched a series of

increasingly sophisticated models. With their independent suspensions, front

disc brakes, and emphasis on performance, BMW established its reputation as a

maker of cars for driving enthusiasts. In 1972, BMW created its racing subsidiary,

BMW Motorsport, which started producing the “M” high-performance versions

of standard BMW models in 1979.

2004 Bentley Continental GT

2002 BMW Motorsport M3-GTR (street version)

Car Manufacturers

2

BU ICK

CA DIL LA C

David Dunbar Buick, a Scottish immigrant to the U.S., started making gasoline

engines in 1899 and built his first car in 1902. He incorporated Buick Motor

Company in 1903, which was taken over the following year by William Durant,

later the founder of General Motors. By 1908, Buick® was producing about 8,000

cars annually, more than any other manufacturer. Buick pioneered the overhead

valve engine and started a racing team featuring Louis Chevrolet. Early racing

successes and a growing reputation for reliability solidified Buick’s reputation. It

became the first brand in the General Motors stable in 1908.

By the mid-1920s, Buick was producing more than a quarter-million cars a year,

but its sales slumped early in the Great Depression. In 1936, stylish new models

conceived by GM design chief Harley Earl revived Buick’s popularity. During WWII,

Buick built aircraft engines and military vehicles. Buick sales boomed during

the 1950s heyday of big, stylish American cars. In the 1960s and 1970s, Buick

introduced smaller, lighter, more innovative cars powered by V6 engines. In the

1980s and early 1990s, Buick again emphasized racing and competition, building

engines for the Indianapolis 500 and performance cars powered by turbocharged

V6s, especially the 1987 Regal GNX “muscle car.” Buick continues to be a

mainstay of the General Motors Corporation today.

Cadillac Automobile Company was founded by Henry Leland in 1902. In 1903

its first production car was an instant success, and in 1909 Cadillac® became

General Motors’ prestige brand and a leading innovator. Cadillac introduced fullyenclosed bodies in 1910, the first reliable electric starter in 1912, and a powerful

V8 engine in 1915. These and other innovations in the 1920s, including a betterbalanced V8 engine, a synchromesh transmission, and safety glass, enhanced

Cadillac’s reputation. In 1930, Cadillac introduced luxurious V16- and V12powered models. Soon Cadillac offered independent front suspensions (pioneered

by Chevrolet) and automatic transmissions.

During WWII, Cadillac V8s and transmissions powered American tanks. After

the war, Cadillac combined technical innovations and styling, introducing a

trendsetting overhead-valve V8 and tail fins. A British Allard powered by the

Cadillac V8 finished third at Le Mans in 1950, and a stock Cadillac coupe finished

10th, proving how potent the new engine was. Over the years Cadillacs grew

larger and more flamboyant, but in 1992 Cadillac introduced the twin-cam

Northstar V8, renewing an emphasis on performance. In 2000, Cadillac returned

to Le Mans with its Prototype racer, the LMP02, which it also campaigned in the

American Le Mans Series. The 2003 CTS and the 400-hp CTS-V race car continue

Cadillac’s return to performance-oriented production cars.

2004 Cadillac CTS-V1987 Buick Regal GNX

Car Manufacturers

2

CH EVR OL ET

CH RY SLE R

In 1911, William Durant enlisted Swiss-born racing star Louis Chevrolet to design

a car with broad appeal, and in 1912 the new Chevrolet Motor Car Company

introduced its first sedan with a long list of standard features. In 1915, Chevrolet®

introduced the 490 (priced at US$490) to compete directly with the best-selling

Ford Model T, and it was an instant success. By 1927, Chevrolet was the most

popular American car. When WWII started, the division was building over 1.5

million vehicles per year. After the war, Chevrolet reclaimed its place as the bestselling brand with popular features including automatic transmission and power

brakes, seat, and windows.

In 1953, Chevrolet launched what would become America’s most successful

sports car, the Corvette, and when Chevrolet introduced its legendary small-block

V8 two years later, it quickly found its way into the Corvette. The 1963 Sting Ray

with its fully independent suspension added to the Corvette’s popularity and

competitiveness. The compact, sporty Camaro debuted in 1967, and became

another instant best-seller. Today, Chevrolet continues to offer a car for nearly

every market niche, and the company’s nickname, “Chevy,” shows the popular

impact of this brand.

In 1910, Walter P. Chrysler became works manager for Buick Motor Company,

and then vice president of General Motors in 1919. In 1925 he founded Chrysler®

Corporation, and rapidly expanded it to become a serious rival to General Motors

and Ford. Chrysler started Plymouth® and DeSoto, and in 1928 acquired the large

and successful Dodge Brothers Corporation, which had sold two million cars

under its own name. In 1934, Chrysler introduced the Airflow, a streamlined car

that pointed to the future, but found few buyers. By 1937, Chrysler was building

more than a million cars a year.

In 1951, Chrysler introduced its powerful “Hemi” V8, which was continually

developed in the 1960s, growing in displacement from 331 cubic inches (5.4

liters) to 426 inches (7 liters) to become a major force in American automobile

racing. In 1998 the Chrysler Corporation merged with Daimler-Benz AG to

form DaimlerChrysler. Two products of this merger appeared in 2004. The

Chrysler Crossfire® sports car shares many components with the first-generation

Mercedes-Benz SLK. The Crossfire SRT-6 is a supercharged high-performance

model with a 320-hp version of the standard V6. The Chrysler ME Four-Twelve,

produced as a prototype, is a 250-mph, V12 powered mid-engine supercar billed

by the company as the “ultimate engineering and design statement from Chrysler

in terms of advanced materials, aerodynamic efficiency, and vehicle

dynamic performance.”

2006 Chrysler Crossre SRT62006 Chevrolet Corvette Z06

Car Manufacturers

DO DGE

EA GLE

Like the Wright brothers, the Dodge brothers (John and Horace) began in the

bicycle business, but around the turn of the twentieth century they switched

to making automobile parts. From 1902 until 1914, when they started the

Dodge Brothers Motor Vehicle Company, the brothers made parts for other

manufacturers, including transmissions for Olds and engines for Ford. The engine

deal netted them a ten percent interest in Ford Motor Company, which they sold

back to Ford in 1919 for US$19,000,000. Dodge Brothers cars, with their all-steel

bodies, rugged construction, and attention to detail, quickly built a reputation for

“dependability,” a word invented by a copywriter to describe them. After 10 years

the brothers had built a million cars, and made another million by 1928, when

they sold their company to the Chrysler Corporation.

Some of the most potent post-WWII Dodges, including the late-1960s Chargers,

were powered by a 426-cubic-inch (7-liter) version of Chrysler’s Hemi V8. In

1992, Dodge introduced the V10-powered Dodge Viper, a muscular retro sports

car that has competed internationally, winning in its class at Le Mans and in the

GT2 World Championship. Dodge has also produced performance versions of its

small cars, notably the Neon-based SRT4 and the PT Cruiser GT Turbo. For 2006,

Dodge reintroduced a Hemi V8-powered Charger, the SRT8.

Eagle was the last reincarnation of American Motors Corporation (AMC), which

had been formed by the merger of Hudson Motorcar Company and NashKelvinator in 1954. In 1970, AMC acquired the Jeep name and facilities from

Kaiser-Willys, but fell on hard times in the 1980s. After a brief collaboration with

France’s Renault, AMC was sold in 1987 to Chrysler Corporation, which ran AMC

as its Jeep/Eagle division from 1988 to 1998. Chrysler’s goal was to attract driving

enthusiasts and would-be buyers of imported cars.

The division’s most successful model was the sporty Eagle Talon, based on the

Mitsubishi Eclipse. The Eclipse and the Talon, as well as the Plymouth version,

called the Laser, were manufactured in Normal, Illinois by a Chrysler/Mitsubishi

joint venture called Diamond Star Motors. From 1990 to 1998, these two-door,

front-wheel drive hatchbacks (powered by a Mitsubishi 4-cylinder engine and

turbocharged in the all-wheel-drive TSi model) were Eagle’s best-selling car. Its

success wasn’t enough to save Eagle, and Chrysler stopped producing the brand

in 1998.

2006 Dodge Charger SRT8

1998 Eagle Talon TSi Turbo

Car Manufacturers

FE RRA RI

FO RD

Ferrari is a legendary name. For 60 years this elite Italian manufacturer has built

some of the world’s fastest and most beautiful cars, and has won innumerable

races. Founder Enzo Ferrari drove his first race in 1919, and started Scuderia

Ferrari in 1929 sponsoring amateur drivers, many competing in cars built by Alfa

Romeo. In 1947 he founded Ferrari and started the string of stunning cars and

racing victories that continues today. In a sense, Ferrari’s intent was to build a

race car that could also be used on the street, but from the beginning Ferrari built

sports and Grand Touring cars to finance its racing efforts.

The first postwar Ferrari, the sleek Tipo 125S roadster, was powered by a 1.5-liter

V12, and started Ferrari’s long record of racing victories. In 1950 the Formula

One World Championship series began, and Ferrari soon won the first of 14 F1

championships to date. These victories and many more at Le Mans and elsewhere

have added to the fervor of Ferrari fans (Tifosi in Italian). Famous Ferrari cars

include the 250 GTO, the Testarossa, the Dino, the 550 Maranello, the F40,

the F50, the F430, and the Enzo. Pininfarina and a few leading designers and

coachbuilders have always created striking bodies for these cars, and Ferrari cars

continue to offer an outstanding blend of technical and esthetic excellence.

Henry Ford incorporated Ford Motor Company in 1903, and it rapidly grew to

become a major force in the fledgling automobile industry. The Ford Model

T, introduced in 1908, revolutionized the mass-production of affordable

automobiles. Key to its huge production was Ford’s pioneering use of the moving

assembly line. In nineteen years Ford manufactured more than fifteen million

Model Ts.

Ford entered the luxury market by purchasing the Lincoln Motor Company in

1922, and started the mid-priced Mercury brand in 1939. By 1927 the Model T

was losing sales to more modern cars from other companies, so Ford replaced

it with the more competitive Model A, and produced four million Model As in

four years. In 1932, Ford Motor Company became the first auto manufacturer

to offer an affordable V8-powered car. In the mid-1950s, Ford added the sporty

Thunderbird to its lineup, and the 1960s saw the introduction of the best-selling

Mustang. Ford introduced the exotic GT-40 in 1964, which won the Le Mans

24-hour road race four straight times in 1966–1969. In 2004, Ford began

producing a new street version of the Ford GT, directly inspired by the GT-40 race

car. At the other end of the spectrum, Ford entered the sport compact market

with the affordable high-performance SVT Focus.

2003 Ford Focus SVT1999 Ferrari 360 Modena

Car Manufacturers

HO NDA

HY UND AI

Starting in 1948, Soichiro Honda filled an important niche in post-WWII

Japan by building motorized bicycles, but his Honda Motor Company soon

grew to become one of the world’s largest and most successful motorcycle

manufacturers. This success allowed Honda to start building small cars in

1960. The energy crisis of the 1970s made Honda’s efficient Civic, with its lowemission CVCC engine, a best-seller in many markets. The mid-size Honda Accord

introduced in 1976 also added to the worldwide reputation of Honda. In the

1980s the company started building cars in the U.S. and Canada.

Soichiro Honda had always been interested in motorsports, and by 1961

his motorcycles were international winners. He sought the same success in

automobile racing at the highest level—in Formula One and Indy Car racing.

In 1964–1968, Honda campaigned its own cars in the Formula One World

Championship, and since 1983 has supplied engines to other constructors. In

1988, Honda-powered F1 cars won fifteen of sixteen races. In 2006, Honda once

again began running its own cars in the Formula One World Championship.

South Korean industrialist Chung Ju-Yung founded Hyundai Motor Company

in 1967 as part of his Hyundai Group, a major engineering, construction, and

shipbuilding enterprise. The company grew to become South Korea’s major car

manufacturer. Hyundai exported cars to Asia, Europe, and the Middle East in

the 1970s and 1980s, and entered the U.S. market in 1986 with the

subcompact Excel.

Hyundai soon established its reputation as a maker of affordable cars, starting

with subcompact models for entry-level buyers, then added both sportier and

more luxurious models to its lineup. Current Hyundai models include the Tuscani

sport coupe (called the Tiburon in the U.S. market). Now the seventh-largest car

maker in the world, Hyundai sells its vehicles in up to 193 countries across several

continents, and has sold around 2.5 million units worldwide.

2003 Honda S2000

2003 Hyundai Tuscani Elisa

Car Manufacturers

IN FIN IT I

JA GUA R

Japanese manufacturer Nissan Motor Company introduced its luxury Infiniti brand

in 1989, focusing on a blend of style, comfort, and performance. The Infiniti

flagship was the potent V8-powered Q45, which featured technology such as

active suspension and four-wheel steering. Over the years the Infiniti line has

grown to include the slightly smaller M45 sedan, the sporty G35 coupe (on the

same chassis as the Nissan Skyline), and G35 sedan.

British automobile maker Jaguar began in 1922 as the Swallow Sidecar Company,

building stylish aluminum sidecars for motorcycles. By 1926 it was also producing

custom bodies for other manufacturers’ cars. In 1931 the company began

building its own cars under the SS name (for Swallow Sidecars). Long, low,

and sporty, the SS1 looked like a more expensive car than it was. In 1935 the

company used the Jaguar name for the first time on a stunning new sports car,

the SS Jaguar 100.

After WWII, the company became Jaguar Cars Ltd. The beautiful 120-mph XK120

sports car appeared in 1948. The racing version, called the C-type, won Le Mans

in 1951 and 1953. In 1954, Jaguar introduced the more powerful XK140 sports

car and the D-type racer, which won Le Mans in 1955, 1956, and 1957. The

sensational 150-mph E-type sports car, introduced in 1961, was the most visually

striking in a long line of attractive cars. Ford Motor Company acquired Jaguar

in 1989, and has carefully preserved Jaguar’s unique identity. Between 1992 and

1994 Jaguar produced 281 XJ220 supercars, and in 1995 launched the sleek,

V8-powered XK-8 sports car. Most recently Jaguar unveiled its new supercharged

sports car, the Jaguar XKR. Building on the excellence of the most technologically

advanced Jaguar ever, the all-new XK with the 4.2 V8 engine introduced in late

2005, the XKR takes the Jaguar experience to new heights. For more than seventy

years Jaguar has maintained its vision of the well-bred sporting automobile,

combining superior performance with unique style.

1993 Jaguar XJ2202003 Inniti G35 Coupe

Car Manufacturers

KO ENI GS EGG

LA MBO RG HIN I

Christian von Koenigsegg founded his Swedish supercar company, Koenigsegg

Automotive Ltd., in 1994. Its mission is to build exclusive two-seat, mid-engine

super sports cars based on state of the art Formula One racing technology for

a few select customers. Bodies and chassis are made of lightweight carbon fiber

composite reinforced with Kevlar and aluminum honeycomb. These cars

offer a combination of race car performance and superior comfort for longdistance touring.

After three years of development and testing, Koenigsegg showed its first

production prototype at the Paris Motor Show in 2000, and delivered its first

production car, the 655-hp V8-powered CC8S, in 2002. This luxurious 240-mph

supercar features a custom leather interior and fitted luggage, along with a host

of high-tech features seldom seen outside of advanced race cars. Koenigsegg

introduced the 806-hp CCR in 2004, and the CCX, which delivers the same

performance using 91-octane fuel and meets even more stringent emissions

requirements, in 2006. Koenigsegg creates each car in its very limited production

specifically for each customer. Like racing cars, these formidable vehicles can

be set up to perform on any track or set of road conditions. Unlike racing cars,

they are well-mannered on the street and offer a level of luxury no race car driver

ever enjoyed.

After WWII, Ferruccio Lamborghini started converting military vehicles into

tractors, and began producing his own tractors in 1948. Many questioned his

judgment when he decided to build sports cars to compete with Ferrari, but in

1963 he founded Automobili Ferrucio Lamborghini. The 350 GT was the first in a

long line of striking designs to wear the charging bull badge, with Lamborghini’s

own V12 engine and chassis, and coachwork by Touring of Milan. In 1966,

Lamborghini produced the first mid-engine supercar, the Miura, a barely tamed

race car for the road, named for a legendary breed of Spanish fighting bulls. Its

4-liter V12 was mounted transversely behind the cockpit, and its sensational body

by Bertone blended aggressiveness and elegance.

In 1974, Lamborghini introduced the Countach, an angular mid-engine supercar

that never lost its ability to astonish first-time viewers and drivers. Its successor

had to be extreme and spectacular; the Diablo was all that and more, with

exotic styling, a 5.7-liter V12, and all-wheel drive. In 1998, Audi AG acquired

Lamborghini, and in 2001 replaced the Diablo with the Murciélago. Aptly named

for a famous fighting bull, it combines modern sophistication and brute force,

with a potent 6.2-liter V12 (enlarged to 6.5 liters in the 2006 Murciélago LP640)

and all-wheel drive. In 2003, Lamborghini introduced the Gallardo, a highperformance sports car designed for everyday use, with all-wheel drive and a 500hp V10. Ferruccio Lamborghini’s goal to build cars that compete with the world’s

best has been fully realized.

2002 Koenigsegg CC8S

2005 Lamborghini Murciélago

Car Manufacturers

4

LA NCI A

LE XUS

Vincenzo Lancia began building cars in 1906, and this Italian car manufacturer

(part of the Fiat Group since 1969) quickly developed a reputation for technical

innovation. Its first car, the 1907 Alpha, featured a tubular front axle. The 1913

Theta included the first built-in electrical system in a European car. The 1922

Lambda featured V4 power and independent suspension, and the 1933 Augusta

was the first sedan with a load-bearing monocoque body. The 1936 Aprilia was

one of the first mass-produced cars with a truly aerodynamic shape. The 1950

Aurelia was powered by the first V6, and mounted its clutch, gearbox, and

differential in a single unit on the rear axle.

Over the years, Lancia cars made their mark in road racing and at times

dominated rally competition. Winning Lancias included the D50 Formula One

racer that appeared in 1954. When the Lancia family sold its interest in the

company, Ferrari took over the Lancia team. The renamed Lancia/Ferrari D50

won the F1 world championship in 1955. Some of Lancia’s greatest competition

successes came from rally cars. The futuristic, wedge-shaped Lancia Stratos

won the World Rally Championship three straight times in 1974–1976. Even

more successful was the HF Integrale version of the Lancia Delta and its ultimate

development, the Evoluzione. This powerful four-wheel-drive hatchback won six

consecutive Constructors Championships between 1987 and 1992.

In 1989, Toyota Motor Corporation of Japan introduced its Lexus line of luxury

cars to the U.S. market, and then Great Britain, Canada, and Australia a year

later. The V8-powered LS 400 and the mid-size ES 250 set the tone for the new

brand with excellent build quality, value, and performance. Lexus has fleshed

out the line with sport coupe and sport utility models. Lexus cars have enjoyed

major success in North America, and were offered for sale in Japan for the first

time in 2005. Lexus successfully entered the world of sports car and endurance

racing in 2004 with its Daytona Prototype, powered by a competition version of

the company’s V8. Current models include the IS300 and IS350 compact sports

sedans and the V8-powered SC430 hardtop sports convertible.

1974 Lancia Stratos HF Stradale

2006 Lexus IS350

Car Manufacturers

4

LO TUS

MA SER AT I

Compared to some other British car manufacturers, Lotus is a relative newcomer,

founded by Colin Chapman in 1952. But Lotus has packed the stuff of legend

into its 55 years, including a long string of celebrated sports cars and seven

Formula One Championships. Chapman’s innovative designs emphasized

simplicity and lightness. In 1957, Chapman introduced two cars that exemplified

this approach: the elegant Lotus Elite sports coupe and the Lotus 7, a minimalist

high-performance roadster. The 7 remains in production after almost fifty

years, built by Lotus until 1973, and then by Caterham Cars, which bought the

manufacturing rights.

Lotus won its first Formula One victory in 1960 and its first World Championship

in 1963. By 1978, Lotus had won five more World Championships and continued

to innovate, experimenting with turbine power, four-wheel drive, lightweight

composites, and the use of ground effects to generate downforce. The Lotus

Esprit sports car, produced from 1976 to 2004, turned heads from the start,

particularly when it appeared in a James Bond movie as a car with submarine

capabilities. After Chapman died in 1982, the company changed hands. Under

GM ownership from 1986 to 1993, Lotus turned the modest Vauxhall Carlton

sedan into a 176-mph “super saloon.” Current models include the Elise roadster

and the Exige coupe. These diminutive fiberglass-bodied sports cars on

aluminum frames maintain Lotus’ fifty-year reputation for putting big

performance into small packages.

Officine Alfieri Maserati was founded in December, 1914, in Bologna, Italy. Since

then, Maserati has played a consistently important role in the history of sports car

culture and its development. In 1926, Alfieri Maserati and his brothers built their

first complete car, the Tipo 26, and Maserati himself drove it to a class win in its

first race. Before and after WWII, legendary racing drivers such as Tazio Nuvolari

and Juan Manual Fangio drove Maserati single-seaters to European victories. In

the U.S., Wilbur Shaw scored back-to-back wins at Indianapolis in 1939–1940

driving a Maserati 8CTF. In the early 1950s, the A6GCS sports car proved itself to

be a winner, and in 1957 the great Fangio won his fifth and final Formula One

championship in the Maserati 250F. Maserati then began building competition

cars for private entrants, including the race-winning Tipo 61, popularly dubbed

the “Birdcage” Maserati because of its complex tubular frame.

In the late 1950s, Maserati focused on building cars in larger numbers, starting

with the handsome aluminum-bodied 3500 GT. In the 1970s, Maserati produced

a series of mid-engine GT cars, including the Bora, Merak, Khamsin, and Mistral,

all named for desert winds. In 1993, Maserati was acquired by the Fiat Group.

With the technical collaboration of Ferrari, the company now makes fast and

elegant tourers including the Quattroporte sedan, and the Coupé and Gran Sport

(Coupé and Spyder) GT cars. Maserati has returned to racing with the MC12

supercar, and remains one of the great Italian makers of sports and luxury cars.

2005 Lotus Elise 111S

2004 Maserati MC12

Car Manufacturers

4

MA ZDA

The Toyo Kogyo Co. of Hiroshima, Japan, the predecessor of Mazda Motor

Corporation, built its first vehicle, the Mazda-Go three-wheeled truck, in 1931.

All of the company’s trucks were given the Mazda name, partly in reference to

Ahura-Mazda, the Zoroastrian god of light, and partly because it sounded like

the name of company founder, Jujiro Matsuda. The first Mazda passenger car, the

R360 coupe, appeared in 1960. In 1961, Mazda started technical cooperation

with the NSU of Germany for rights to develop and use the powerful, lightweight

rotary combustion engine originally designed by Dr. Felix Wankel.

Mazda started selling rotary-engined cars in Japan in 1967, the same year it

began exporting cars to Europe. Mazda entered the U.S. market in 1970 with

the rotary-powered RX-2, and introduced the slightly larger RX-3 in 1971. Their

ability to leave cars powered by larger conventional engines behind made a

big impression. Mazda introduced the RX-7 sports car powered by a twin-rotor

Wankel engine in 1978, and its combination of power and handling made it an

instant hit. The Mazda 787B prototype, powered by a four-rotor, 700-hp engine,

won at Le Mans in 1991. Current models include an updated version of MX-5/

Miata sports car, the Axela/Mazda 3 and Atenza/Mazda 6, and the latest Mazda

rotary-powered sports car, the RX-8.

Since 1990, McLaren Automotive in England has designed and produced a

limited number of exclusive, high-performance road cars. Along with Formula

One constructor and competitor Team McLaren Mercedes, the company is part

of the McLaren Group. The organization is named after the late Bruce McLaren,

a New Zealand-born racing driver, engineer, and race car designer whose

creations won races in series from Formula One to CanAm. The McLaren F1 is a

240-mph supercar that uses technology from Formula One racing, including a

strong, lightweight carbon fiber monocoque structure. Between 1992 and 1998,

McLaren built one hundred F1s, priced in excess of US$1 million each. The F1’s 6liter, 627-hp BMW V12 gives this exotic three-seat coupe tremendous speed and

acceleration, and the chassis provides handling to match. In 1995, F1s took first,

third, fourth, and fifth places at Le Mans 24 Hours, proving that a million dollars

also buys impressive durability, along with racing capability.

In 1999, McLaren started working with DaimlerChrysler to develop and build

the Mercedes-Benz SLR McLaren, which debuted in 2003. For a lucky few with

US$450,000 to spend, the new SLR provides unsurpassed levels of speed,

handling, safety, and comfort. Like the McLaren F1, the SLR wraps a very powerful

engine and a luxury interior in a lightweight composite structure. Its 5.4-liter,

617-hp AMG V8 propels the SLR to over 200 mph.

1997 Mazda RX7

1997 McLaren F1 GT

Car Manufacturers

4

ME RCE DE S-B EN Z

MI NI

Mercedes-Benz history reaches back to the dawn of the automotive era. In

Germany, Karl Benz and Gottlieb Daimler were working independently to perfect

the internal combustion engine and use it to propel a vehicle. In 1885, Benz

became the first to build and patent a gas-powered vehicle, the three-wheeled

Tri-Car. By 1900, both Benz and Daimler were selling cars in significant quantities.

Daimler distributor Emil Jellinek named a new model for his daughter, Mercedes.

In 1902 the low-slung Mercedes Simplex set a standard of performance with its

43-mph top speed. By 1911 the Blitzen (Lightning) Benz racer set a speed record

of 141 mph.

In 1926 the two companies merged to form Daimler-Benz, making cars under

the Mercedes-Benz name. Technical Director Ferdinand Porsche developed two

of Mercedes’ greatest cars, the supercharged SS and SSK in 1928–1931. Before

WWII, Mercedes became a dominant force in Grand Prix racing with a series of

technologically advanced machines. From 1952 to 1955, Mercedes returned to

racing with the Le Mans-winning 300 SL and the W196 Formula One car, which

proved equally dominant. In 1989, Mercedes started supplying engines to race

car constructors Sauber and McLaren. The company partnered with McLaren to

launch the 200-mph Mercedes-Benz SLR McLaren supercar in 2004. From the

spindly, bicycle-based Tri car to today’s SLR supercar, the history of Mercedes-Benz

is the history of the car itself.

One of the most popular cars in recent years is the new MINI, launched by BMW’s

MINI subsidiary in 2001. This small, nimble car is a modern interpretation of the

Morris Mini Minor, an even smaller car launched by British Motor Corporation in

1959 and produced until 2000. The original Mini was a revolutionary transverseengine, front-wheel drive design that devoted 80% of its petite frame to

passengers. It sipped gasoline, and handled surprisingly well, riding on tiny

ten-inch wheels. Race car builder John Cooper designed higher-performance

models called the Mini Cooper and Mini Cooper S. During its forty-year

production more than five million Minis were sold, and the original remains a

cult classic and tuner favorite.

In 1994, BMW bought the Rover Group, whose assets included the Mini, from

British Aerospace. BMW kept the little car in production while planning its

successor. The new MINI is available in three models: the basic MINI One powered

by a 90-hp, 4-cylinder engine, the 115-hp MINI Cooper, and the supercharged

170-hp MINI Cooper-S. An optional John Cooper Works tuning kit increases

horsepower to 210. In 2004 a soft-top MINI Cabriolet was added to the line.

The new MINI may be a lot bigger than the original version, but is its spiritual

successor, offering a lot of fun in what is for today a very small package.

2005 Mercedes-Benz SLR

2003 MINI Cooper S

Loading...

Loading...