Page 1

HP-UX Directory Server deployment guide

HP-UX Directory Server Version 8.1

HP Part Number: 5900-0315

Published: September 2009

Edition: 1

Page 2

© Copyright 2009 Hewlett-Packard Development Company, L.P.

Confidential computersoftware. Valid license from HP required for possession, use or copying. Consistent with FAR 12.211 and 12.212, Commercial

Computer Software, Computer Software Documentation, and Technical Data for Commercial Items are licensed to the U.S. Government under

vendor's standard commercial license.

The informationcontained hereinis subject to change without notice. Theonly warranties for HPproducts andservices are set forth in the express

warranty statements accompanying such products and services. Nothing herein should be construed as constituting an additional warranty. HP

shall not be liable for technical or editorial errors or omissions contained herein.

Page 3

Table of Contents

1 Introduction to directory services..................................................................................9

1.1 About directory services...................................................................................................................9

1.1.1 About global directory services................................................................................................9

1.1.2 About LDAP............................................................................................................................10

1.2 Introduction to Directory Server.....................................................................................................10

1.2.1 Overview of the server frontend.............................................................................................10

1.2.2 Server plug-ins overview........................................................................................................11

1.2.3 Overview of the basic directory tree.......................................................................................11

1.3 Directory Server data storage..........................................................................................................12

1.3.1 About directory entries...........................................................................................................13

1.3.1.1 Performing queries on directory entries.........................................................................13

1.3.2 Distributing directory data......................................................................................................13

1.4 Directory design overview..............................................................................................................13

1.4.1 Design process outline............................................................................................................14

1.4.2 Deploying the directory..........................................................................................................14

1.5 Other general directory resources...................................................................................................15

2 Planning the directory data.........................................................................................17

2.1 Introduction to directory data.........................................................................................................17

2.1.1 Information to include in the directory...................................................................................17

2.1.2 Information to exclude from the directory..............................................................................17

2.2 Defining directory needs.................................................................................................................18

2.3 Performing a site survey..................................................................................................................18

2.3.1 Identifying the applications that use the directory.................................................................19

2.3.2 Identifying data sources..........................................................................................................20

2.3.3 Characterizing the directory data...........................................................................................20

2.3.4 Determining level of service....................................................................................................21

2.3.5 Considering a data master......................................................................................................21

2.3.6 Determining data ownership..................................................................................................22

2.3.7 Determining data access..........................................................................................................23

2.4 Documenting the site survey...........................................................................................................24

2.5 Repeating the site survey................................................................................................................25

3 Designing the directory schema.................................................................................27

3.1 Schema design process overview....................................................................................................27

3.2 Standard schema.............................................................................................................................27

3.2.1 Schema format.........................................................................................................................27

3.2.2 Standard attributes..................................................................................................................28

3.2.3 Standard object classes............................................................................................................29

3.3 Mapping the data to the default schema.........................................................................................30

3.3.1 Viewing the default directory schema....................................................................................30

3.3.2 Matching data to schema elements.........................................................................................30

3.4 Customizing the schema.................................................................................................................31

3.4.1 When to extend the schema....................................................................................................32

3.4.2 Getting and assigning object identifiers..................................................................................32

3.4.3 Naming attributes and object classes......................................................................................32

3.4.4 Strategies for defining new object classes...............................................................................32

3.4.5 Strategies for defining new attributes.....................................................................................34

3.4.6 Deleting schema elements.......................................................................................................34

Table of Contents 3

Page 4

3.4.7 Creating custom schema files..................................................................................................34

3.4.8 Custom schema best practices.................................................................................................35

3.4.8.1 Naming schema files.......................................................................................................35

3.4.8.2 Using 'user defined' as the origin....................................................................................36

3.4.8.3 Defining attributes before object classes.........................................................................36

3.4.8.4 Defining schema in a single file......................................................................................36

3.5 Maintaining consistent schema.......................................................................................................36

3.5.1 Schema checking.....................................................................................................................37

3.5.2 Selecting consistent data formats............................................................................................37

3.5.3 Maintaining consistency in replicated schema.......................................................................37

3.6 Other schema resources...................................................................................................................38

4 Designing the directory tree........................................................................................39

4.1 Introduction to the directory tree....................................................................................................39

4.2 Designing the directory tree............................................................................................................39

4.2.1 Choosing a suffix.....................................................................................................................39

4.2.1.1 Suffix naming conventions..............................................................................................40

4.2.1.2 Naming multiple suffixes................................................................................................40

4.2.2 Creating the directory tree structure.......................................................................................41

4.2.2.1 Branching the directory...................................................................................................41

4.2.2.2 Identifying branch points................................................................................................42

4.2.2.3 Replication considerations..............................................................................................44

4.2.2.4 Access control considerations.........................................................................................45

4.2.3 Naming Entries.......................................................................................................................46

4.2.3.1 Naming person entries....................................................................................................46

4.2.3.2 Naming group entries.....................................................................................................47

4.2.3.3 Naming organization entries..........................................................................................47

4.2.3.4 Naming other kinds of entries........................................................................................48

4.3 Grouping directory entries..............................................................................................................48

4.3.1 About roles..............................................................................................................................48

4.3.2 Deciding between roles and groups........................................................................................49

4.3.3 About class of service..............................................................................................................49

4.4 Virtual directory information tree views........................................................................................50

4.4.1 About virtual DIT views.........................................................................................................50

4.4.2 Advantages of using virtual DIT views..................................................................................53

4.4.3 Example of virtual DIT views.................................................................................................54

4.4.4 Views and other directory features.........................................................................................55

4.4.5 Effects of virtual views on performance.................................................................................55

4.4.6 Compatibility with existing applications................................................................................55

4.5 Directory tree design examples.......................................................................................................56

4.5.1 Directory tree for an international enterprise.........................................................................56

4.5.2 Directory tree for an ISP..........................................................................................................57

4.6 Other directory tree resources.........................................................................................................57

5 Designing the directory topology...............................................................................59

5.1 Topology overview..........................................................................................................................59

5.2 Distributing the directory data........................................................................................................59

5.2.1 About using multiple databases..............................................................................................60

5.2.2 About suffixes.........................................................................................................................61

5.3 About knowledge references...........................................................................................................62

5.3.1 Using referrals.........................................................................................................................62

5.3.1.1 The structure of an LDAP referral..................................................................................63

5.3.1.2 About default referrals....................................................................................................63

4 Table of Contents

Page 5

5.3.1.3 Smart referrals.................................................................................................................64

5.3.1.4 Tips for designing smart referrals...................................................................................66

5.3.2 Using chaining.........................................................................................................................67

5.3.3 Deciding between referrals and chaining...............................................................................67

5.3.3.1 Usage differences............................................................................................................68

5.3.3.2 Evaluating access controls...............................................................................................68

5.4 Using indexes to improve database performance...........................................................................70

5.4.1 Overview of directory index types..........................................................................................70

5.4.2 Evaluating the costs of indexing.............................................................................................71

6 Designing the replication process..............................................................................73

6.1 Introduction to replication..............................................................................................................73

6.1.1 Replication concepts................................................................................................................73

6.1.1.1 Unit of replication...........................................................................................................73

6.1.1.2 Read-write and read-only replicas..................................................................................74

6.1.1.3 Suppliers and consumers................................................................................................74

6.1.1.4 Replication and changelogs............................................................................................74

6.1.1.5 Replication agreement.....................................................................................................75

6.1.2 Data consistency......................................................................................................................75

6.2 Common replication scenarios........................................................................................................75

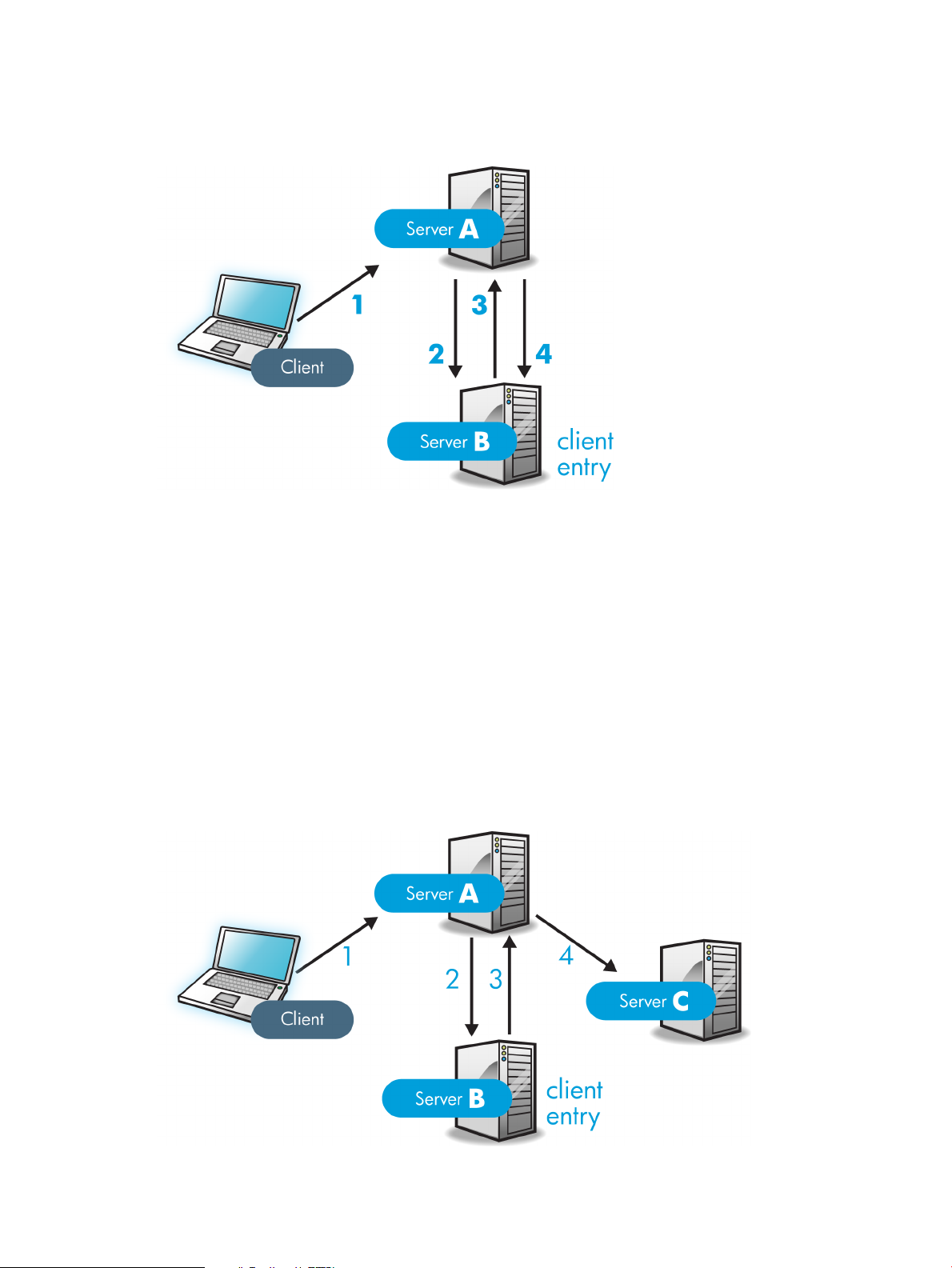

6.2.1 Single-master replication.........................................................................................................76

6.2.2 Multi-master replication..........................................................................................................76

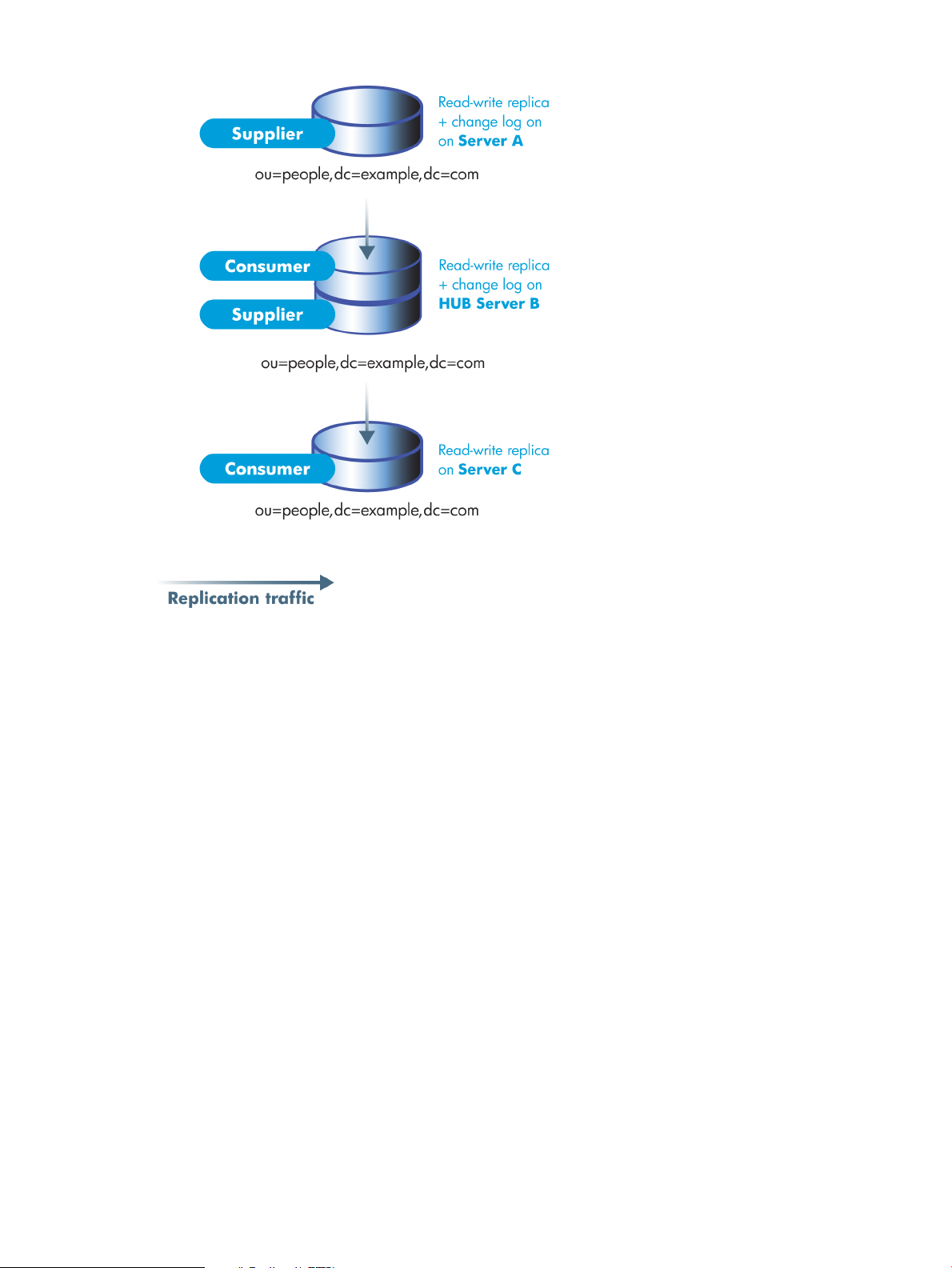

6.2.3 Cascading replication..............................................................................................................79

6.2.4 Mixed environments...............................................................................................................81

6.3 Defining a replication strategy........................................................................................................82

6.3.1 Conducting a replication survey.............................................................................................83

6.3.2 Replicated selected attributes with fractional replication.......................................................83

6.3.3 Replication resource requirements..........................................................................................84

6.3.4 Managing disk space required for multi-master replication..................................................84

6.3.5 Replication across a wide-area network.................................................................................85

6.3.6 Using replication for high availability....................................................................................85

6.3.7 Using replication for local availability....................................................................................86

6.3.8 Using replication for load balancing.......................................................................................86

6.3.8.1 Example of network load balancing................................................................................87

6.3.8.2 Example of load balancing for improved performance..................................................88

6.3.8.3 Example replication strategy for a small site..................................................................89

6.3.8.4 Example replication strategy for a large site...................................................................89

6.4 Using replication with other Directory Server features..................................................................90

6.4.1 Replication and access control................................................................................................90

6.4.2 Replication and Directory Server plug-ins..............................................................................90

6.4.3 Replication and database links................................................................................................90

6.4.4 Schema replication..................................................................................................................91

6.4.5 Replication and synchronization.............................................................................................92

7 Designing synchronization..........................................................................................93

7.1 Windows synchronization overview..............................................................................................93

7.1.1 Synchronization agreements...................................................................................................93

7.1.2 Changelogs..............................................................................................................................94

7.1.3 Controlling synchronization...................................................................................................94

7.2 Planning windows synchronization...............................................................................................94

7.2.1 Resource requirements............................................................................................................94

7.2.2 Managing disk space for the changelog..................................................................................95

7.2.3 Defining the connection type..................................................................................................95

Table of Contents 5

Page 6

7.2.4 Considering a data master......................................................................................................95

7.2.5 Determining the subtree to synchronize.................................................................................96

7.2.6 Interaction with a replicated environment.............................................................................96

7.2.7 Identifying the directory data to synchronize.........................................................................97

7.2.8 Synchronizing passwords and installing password services..................................................98

7.2.9 Defining an update strategy....................................................................................................98

7.2.10 Editing the sync agreement...................................................................................................98

7.3 Schema elements sycnhronized between Active Directory and Directory Server..........................98

7.3.1 User attributes synchronized between Directory Server and Active Directory.....................99

7.3.2 User schema differences between Directory Server and Active Directory...........................100

7.3.2.1 Values for cn attributes..................................................................................................100

7.3.2.2 Password policies..........................................................................................................100

7.3.2.3 Values for street and streetAddress..............................................................................101

7.3.2.4 Contraints on the initials attribute................................................................................101

7.3.3 Group attributes synchronized between Directory Server and Active Directory................101

7.3.4 Group schema differences between Directory Server and Active Directory........................102

8 Designing a secure directory...................................................................................103

8.1 About security threats...................................................................................................................103

8.1.1 Unauthorized access..............................................................................................................103

8.1.2 Unauthorized tampering.......................................................................................................103

8.1.3 Denial of service....................................................................................................................104

8.2 Analyzing security needs..............................................................................................................104

8.2.1 Determining access rights.....................................................................................................104

8.2.2 Ensuring data privacy and integrity.....................................................................................105

8.2.3 Conducting regular audits....................................................................................................105

8.2.4 Example security needs analysis...........................................................................................105

8.3 Overview of security methods......................................................................................................105

8.4 Selecting appropriate authentication methods.............................................................................106

8.4.1 Anonymous access................................................................................................................106

8.4.2 Simple password...................................................................................................................107

8.4.3 Certificate-based authentication............................................................................................108

8.4.4 Simple password over SSL/TLS.............................................................................................108

8.4.5 Simple authentication and security layer..............................................................................108

8.4.6 Proxy authentication.............................................................................................................108

8.5 Preventing authentication by account deactivation......................................................................109

8.6 Designing a password policy........................................................................................................109

8.6.1 How password policy works.................................................................................................109

8.6.2 Password policy attributes....................................................................................................113

8.6.2.1 Password change after reset..........................................................................................113

8.6.2.2 User-defined passwords................................................................................................113

8.6.2.3 Password expiration......................................................................................................114

8.6.2.4 Expiration warning........................................................................................................114

8.6.2.5 Grace login limit............................................................................................................114

8.6.2.6 Password syntax checking.............................................................................................114

8.6.2.7 Password length............................................................................................................115

8.6.2.8 Password minimum age................................................................................................115

8.6.2.9 Password history...........................................................................................................115

8.6.2.10 Password storage schemes..........................................................................................116

8.6.3 Designing an account lockout policy....................................................................................116

8.6.4 Designing a password policy in a replicated environment..................................................116

8.7 Designing access control................................................................................................................117

8.7.1 About the ACI format............................................................................................................117

8.7.1.1 Targets...........................................................................................................................118

6 Table of Contents

Page 7

8.7.1.2 Permissions....................................................................................................................118

8.7.1.3 Bind rules.......................................................................................................................119

8.7.2 Setting permissions................................................................................................................119

8.7.2.1 The precedence rule......................................................................................................119

8.7.2.2 Allowing or denying access..........................................................................................119

8.7.2.3 When to deny access.....................................................................................................120

8.7.2.4 Where to place access control rules...............................................................................120

8.7.2.5 Using filtered access control rules.................................................................................120

8.7.3 Viewing ACIs: Get effective rights........................................................................................121

8.7.4 Using ACIs: Some hints and tricks........................................................................................122

8.8 Database encryption......................................................................................................................123

8.9 Securing server to server connections...........................................................................................124

8.10 Other security resources..............................................................................................................124

9 Directory design examples.......................................................................................125

9.1 Design example: A local enterprise...............................................................................................125

9.1.1 Local enterprise data design..................................................................................................125

9.1.2 Local enterprise schema design.............................................................................................125

9.1.3 Local enterprise directory tree design...................................................................................126

9.1.4 Local enterprise topology design..........................................................................................127

9.1.4.1 Database topology.........................................................................................................127

9.1.5 Local enterprise replication design.......................................................................................128

9.1.5.1 Supplier architecture.....................................................................................................128

9.1.5.2 Supplier consumer architecture....................................................................................129

9.1.6 Local enterprise security design............................................................................................130

9.1.7 Local enterprise tuning and optimizations...........................................................................131

9.1.8 Local enterprise operations decisions...................................................................................131

9.2 Design example: A multinational enterprise and its extranet.......................................................131

9.2.1 Multinational enterprise data design....................................................................................132

9.2.2 Multinational enterprise schema design...............................................................................132

9.2.3 Multinational enterprise directory tree design.....................................................................132

9.2.4 Multinational enterprise topology design.............................................................................134

9.2.4.1 Database topology.........................................................................................................134

9.2.4.2 Server topology.............................................................................................................135

9.2.5 Multinational enterprise replication design..........................................................................137

9.2.5.1 Supplier architecture.....................................................................................................137

9.2.6 Multinational enterprise security design..............................................................................139

10 Support and other resources..................................................................................141

10.1 Contacting HP..............................................................................................................................141

10.1.1 Information to collect before contacting HP........................................................................141

10.1.2 How to contact HP technical support.................................................................................141

10.1.3 HP authorized resellers.......................................................................................................141

10.1.4 Documentation feedback.....................................................................................................141

10.2 Related information.....................................................................................................................141

10.2.1 HP-UX Directory Server documentation set.......................................................................141

10.2.2 HP-UX documentation set...................................................................................................142

10.2.3 Troubleshooting resources...................................................................................................143

10.3 Typographic conventions............................................................................................................143

Glossary.........................................................................................................................145

Table of Contents 7

Page 8

Index...............................................................................................................................155

8 Table of Contents

Page 9

1 Introduction to directory services

This document provides information on deploying the HP-UX Directory Server

HP-UX Directory Server provides a centralized directory service for intranet, network, and

extranet information. Directory Server integrates with existing systems and acts as a centralized

repository for the consolidation of employee, customer, supplier, and partner information.

Directory Server can even be extended to manage user profiles, preferences, and authentication.

This chapter describes the basic ideas and concepts for understanding what a directory service

does to help begin designing the directory service.

1.1 About directory services

The term directory service refers to the collection of software, hardware, and processes that store

information about an enterprise, subscribers, or both, and make that information available to

users. A directory service consists of at least one instance of Directory Server and at least one

directory client program. Client programs can access names, phone numbers, addresses, and

other data stored in the directory service.

An example of a directory service is a domain name system (DNS) server. A DNS server maps

computer host names to IP addresses. Thus, all the computing resources (hosts) become clients

of the DNS server. Mapping host names allows users of computing resources to easily locate

computers on a network by remembering host names rather than IP addresses. A limitation of

a DNS server is that it stores only two types of information: names and IP addresses. A true

directory service stores virtually unlimited types of information.

Directory Server stores all user and network information in a single, network-accessible repository.

Many kinds of different information can be stored in the Directory Server:

• Physical device information, such as data about the printers in an organization, such as

location, color or black and white, manufacturer, date of purchase, and serial number.

• Public employee information, such as name, email address, and department.

• Private employee information, such as salary, government identification numbers, home

addresses, phone numbers, and pay grade.

• Contract or account information, such as the name of a client, final delivery date, bidding

information, contract numbers, and project dates.

Directory Server serves the needs of a wide variety of applications. It also provides a standard

protocol and application programming interfaces (APIs) to access the information it contains.

1.1.1 About global directory services

Directory Server provides global directory services, which means that it provides information

to a wide variety of applications. Rather than attempting to unify proprietary databases bundled

with different applications, which is an administrative burden, Directory Server is a single

solution to manage the same information.

For example, a company is running three different proprietary email systems, each with its own

proprietary directory service. If users change their passwords in one directory, the changes are

not automatically replicated in the others. Managing multiple instances of the same information

results in increased hardware and personnel costs; the increased maintenance overhead is referred

to as the n+1 directory problem.

A global directory service solves the n+1 directory problem by providing a single, centralized

repository of directory information that any application can access. However, giving a wide

variety of applications access to the directory service requires a network-based means of

communicating between the applications and the directory service. Directory Server uses LDAP

for applications to access to its global directory service.

1.1 About directory services 9

Page 10

1.1.2 About LDAP

LDAP provides a common language that client applications and servers use to communicate

with one another. LDAP is a "lightweight" version of the Directory Access Protocol (DAP)

described by the ISO X.500 standard. DAP gives any application access to the directory through

an extensible and robust information framework but at a high administrative cost. DAP uses a

communications layer thatis not the Internetstandard protocol and hascomplex directory-naming

conventions.

LDAP preserves the best features of DAP while reducing administrative costs. LDAP uses an

open directory access protocol running over TCP/IP and simplified encoding methods. It retains

the data model and can support millions of entries for a modest investment in hardware and

network infrastructure.

1.2 Introduction to Directory Server

HP-UX Directory Server includes the directory itself, the server-side software that implements

the LDAP protocol, and a client-side graphical user interface that allows end-users to search and

change entries in the directory.

Without adding other LDAP client programs, Directory Server can provide the foundation for

an intranet or extranet. Every Directory Server and compatible server applications use the

directory as a central repository for shared server information, such as employee, customer,

supplier, and partner data.

Directory Server can manage user authentication, create access control, set up user preferences,

and centralize user management. In hosted environments, partners, customers, and suppliers

can manage their own portions of the directory, reducing administrative costs.

When Directory Server is installed and set up, the following components are installed:

• The coreDirectory ServerLDAP server, the LDAP v3-compliant network daemon (ns-slapd)

and all the associated plug-ins, command-line tools for managing the server and its databases,

and its configuration and schema files. For more information about the command-line tools,

see the HP-UX Directory Server configuration, command, and file reference.

• Administration Server, a web server which controls the different portals that access the

LDAP server. For more information about the Administration Server, see Using the Admin

Server.

• Directory Server Console, a graphical management console that dramatically reduces the

effort of setting up and maintaining the directory service. For more information about the

Directory Server Console, see HP-UX Directory Server console guide.

• Web applications such as Admin Express that allow users to search for information in the

Directory Server, in addition to providing access to their own information, including

password changes, to reduce user support costs.

• SNMP agentto monitor the Directory Server using the Simple Network Management Protocol

(SNMP). For more information about SNMP monitoring, see the HP-UX Directory Server

administrator guide.

1.2.1 Overview of the server frontend

Directory Server is a multithreaded application. This means that multiple clients can bind to the

server at the same time over the same network. As directory services grow to include larger

numbers of entries or geographically-dispersed clients, they also include multiple Directory

Servers placed in strategic places around the network.

The server frontend of Directory Server manages communications with directory client programs.

Multiple clientprograms can communicate with the server using both LDAP over TCP/IP (Internet

traffic protocols) and LDAP over Unix sockets (LDAPI). The Directory Server can establish a

secure (encrypted) connection with SSL/TLS, depending on whether the client negotiates the use

of Transport Layer Security (TLS) for the connection.

10 Introduction to directory services

Page 11

When communication takes place with TLS, the communication is usually encrypted. If clients

have been issued certificates, TLS/SSL can be used by Directory Server to confirm that the client

has the right to access the server. TLS/SSL is used to perform other security activities, such as

message integrity checks, digital signatures, and mutual authentication between servers.

NOTE:

Directory Server runs as a daemon; the process is ns-slapd.

1.2.2 Server plug-ins overview

Directory Server relies on plug-ins to add functionality to the core server. For example, a database

layer is a plug-in. Directory Server has plug-ins for replication, chaining databases, and other

different directory functions.

Generally, a plug-in can be disabled, particularly plug-ins that extend the server functionality.

When disabled, the plug-in's configuration information remains in the directory, but its function

is not used by the server. Depending on what the directory is supposed to do, any of the plug-ins

provided with Directory Server can be enabled to extend the Directory Server functionality.

(Plug-ins related to the core directory service operations, like backend database plug-in, naturally

cannot be disabled.)

For more information on the default plug-ins with Directory Server and the functions available

for writing custom plug-ins, see the HP-UX Directory Server plug-in reference.

1.2.3 Overview of the basic directory tree

The directory tree, also known as a directory information tree (DIT), mirrors the tree model used

by most file systems, with the tree's root, or first entry, appearing at the top of the hierarchy.

During installation, Directory Server creates a default directory tree.

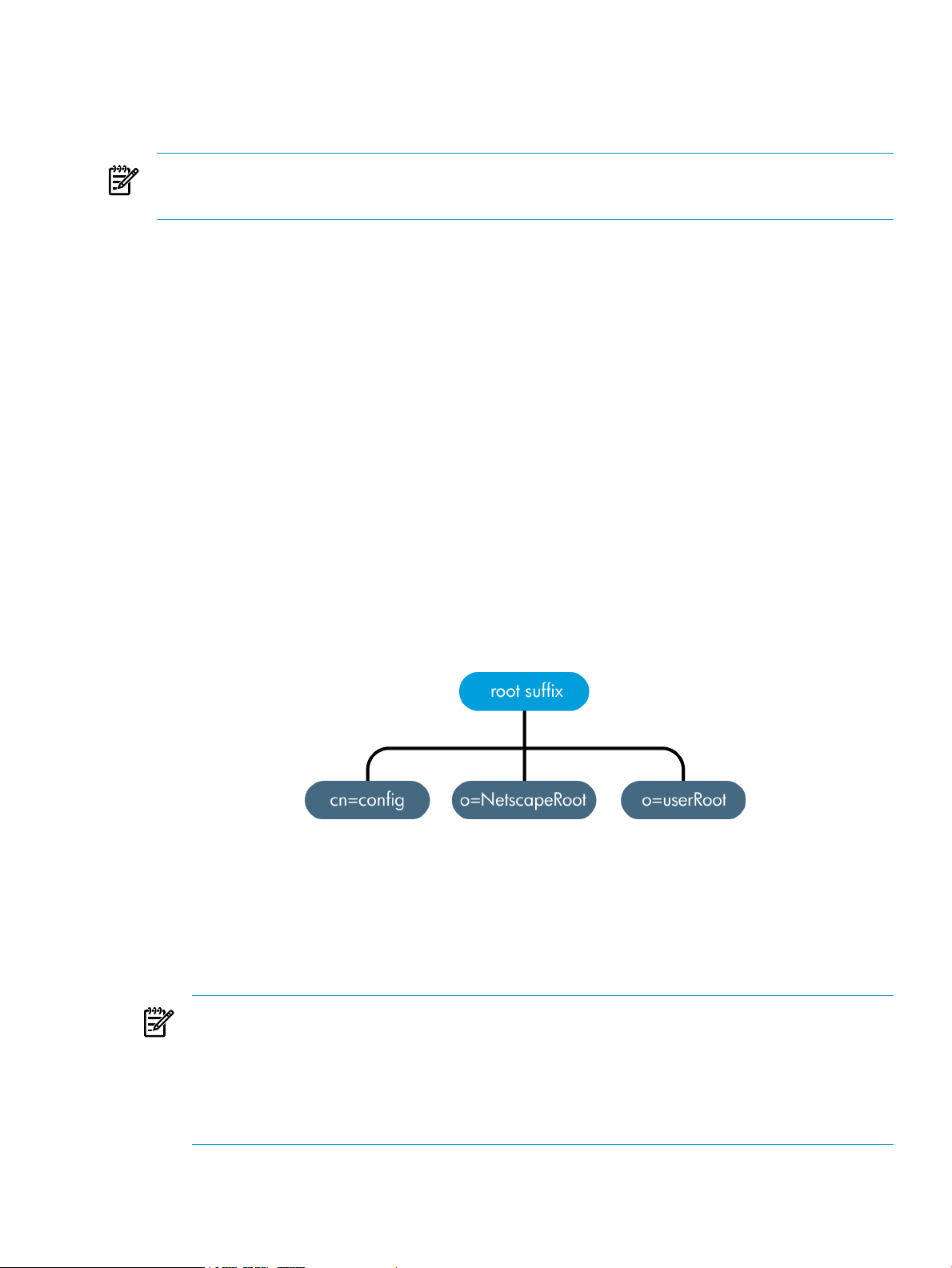

Figure 1-1 Layout of default Directory Server directory tree

The root of the tree is called the root suffix. For information about naming the root suffix, see

“Choosing a suffix”.

After a standard installation, the directory contains three subtrees under the root suffix:

• cn=config, the subtree containing information about the server's internal configuration.

• o=NetscapeRoot, the subtree containing the configuration information of the Directory

Server and Administration Server.

NOTE:

When additional instances of Directory Server are installed, they can be configured not to

have an o=NetscapeRoot database; in that case, the instances use a configuration directory

(or the o=NetscapeRoot subtree) on another server. See the HP-UX Directory Server

installation guide for more information about choosing the location of the configuration

directory.

• cn=monitor, the subtree containing Directory Server server and database monitoring

statistics.

1.2 Introduction to Directory Server 11

Page 12

• cn=schema, the subtree containing the schema elements currently loaded in the server.

• user_suffix, the suffix for the default user database created when the Directory Server is

setup. The name of the suffix is defined by the user when the server is created; the name of

the associated database is userRoot. The database can be populated with entries by

importing an LDIF file at setup or entries can be added to it later.

The user_suffix suffix frequently has a dc naming convention, like dc=example,dc=com.

Another common naming attribute is the o attribute, which is used for an entire organization,

like o=example.com.

The default directory tree can be extended to add any data relevant to the directory installation.

For more information about directory trees, see Chapter 4 “Designing the directory tree”.

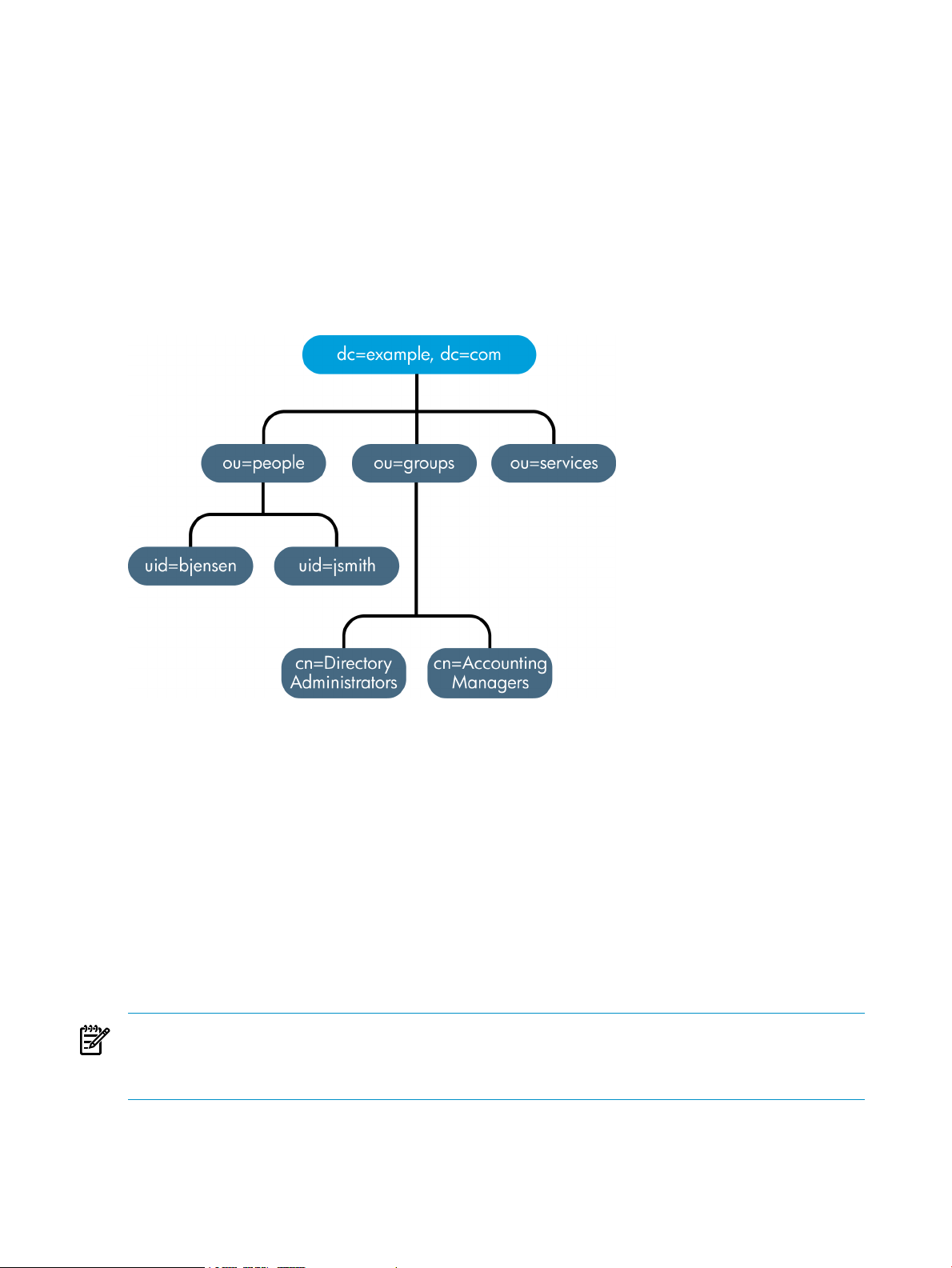

Figure 1-2 Expanded directory tree for example corp.

1.3 Directory Server data storage

The database is the basic unit of storage, performance, replication, and indexing. All Directory

Server operations (importing, exporting, backing up, restoring, and indexing entries) are

performed on the database. Directory data are stored in an LDBM database. The LDBM database

is implemented as a plug-in that is automatically installed with the directory and is enabled by

default.

By default, Directory Server uses one backend database instance for a root suffix, and, by default,

there are two databases, o=NetscapeRoot for configuration entries and userRoot for directory

entries. A single database is sufficient to contain the directory tree. This database can manage

millions of entries.

This database supports advanced methods of backing up and restoring data, in order to minimize

risk to data.

NOTE:

For database files that are larger than 2 gigabytes, the file system must support large files. Use

the vxfs file system and set the largefiles option to on.

Multiple databases can be used to support the whole Directory Server deployment. Information

is distributed across the databases, allowing the server to hold more data than can be stored in

a single database.

12 Introduction to directory services

Page 13

1.3.1 About directory entries

LDAP Data Interchange Format (LDIF) is a standard text-based format for describing directory

entries. An entry consists of a number of lines in the LDIF file (also called a stanza), which contains

information about an object, such as a person in the organization or a printer on the network.

Information about the entry is represented in the LDIF file by a set of attributes and their values.

Each entry has an object class attribute that specifies the kind of object the entry describes and

defines the set of additional attributes it contains. Each attribute describes a particular trait of

an entry.

For example, an entry might be of object class organizationalPerson, indicating that the

entry represents a person within an organization. This object class supports the givenname and

telephoneNumber attributes. The values assigned to these attributes give the name and phone

number of the person represented by the entry.

Directory Server also uses read-only attributes that are calculated by the server. These attributes

are called operational attributes. The administrator can manually set operational attributes that

can be used for access control and other server functions.

1.3.1.1 Performing queries on directory entries

Entries are storedin a hierarchical structure in the directorytree. LDAP supports tools that query

the database for an entry and request all entries below it in the directory tree. The root of this

subtree is called the base distinguished name, or base DN. For example, if performing an LDAP

search request specifying a base DN of ou=people, dc=example,dc=com, then the search

operation examines only the ou=people subtree in the dc=example,dc=com directory tree.

Not all entries are automatically returned in response to an LDAP search, however, because

administrative entries (which have the ldapsubentry object class) are not returned by default

with LDAP searches. Administrative object, for example, can be entries used to define a role or

a class of service. To include these entries in the search response, clients need to search specifically

for entries with the ldapsubentry object class. See “About roles” for more information about

roles and “About class of service” for more information about class of service.

1.3.2 Distributing directory data

When various parts of the directory tree are stored in separate databases, the directory can process

client requests in parallel, which improves performance. The databases can even be located on

different machines to further improve performance.

Distributed data are connected by a special entry in a subtree of the directory, called a database

link, which point to data stored remotely. When a client application requests data from a database

link, the database link retrieves the data from the remote database and returns it to the client.

All LDAP operations attempted below this entry are sent to the remote machine. This method

is called chaining.

Chaining is implemented in the server as a plug-in, which is enabled by default.

1.4 Directory design overview

Planning the directory service before actual deployment is the most important task to ensure the

success of the directory. The design process involves gathering data about the directory

requirements, such as environment and data sources, users, and the applications that use the

directory. This information is integral to designing an effective directory service because it helps

identify the arrangement and functionality required.

The flexibility of Directory Server means the directory design can be reworked to meet unexpected

or changing requirements, even after the Directory Server is deployed.

1.4 Directory design overview 13

Page 14

1.4.1 Design process outline

1. Chapter 2 “Planning the directory data”

The directory contains data such as user names, telephone numbers, and group details. This

chapter analyzes the various sources of data in the organization and understand their

relationship with one another. It describes the types of data that can be stored in the directory

and other tasks to perform to design the contents of the Directory Server.

2. Chapter 3 “Designing the directory schema”

The directory is designed to support one or more directory-enabled applications. These

applications have requirements of the data stored in the directory, such as the file format.

The directory schema determines the characteristics of the data stored in the directory. The

standard schema shipped with Directory Server is introduced in this chapter, as well as a

description of how to customize the schema and tips for maintaining a consistent schema.

3. Chapter 4 “Designing the directory tree”

Along with determining what information is contained in the Directory Server, it is important

to determine how that information is going to be organized and referenced. This chapter

introduces the directory tree and gives an overview of the design of the data hierarchy.

Sample directory tree designs are also provided.

4. Chapter 5 “Designing the directory topology”

Topology design means how the directory tree is divided among multiple physical Directory

Servers and how these servers communicate with one another. The general principles behind

design, using multiple databases, the mechanisms available for linking the distributed data

together, and how the directory itself keeps track of distributed data are all described in this

chapter.

5. Chapter 6 “Designing the replication process”

When replication is used, multiple Directory Servers maintain the same directory data to

increase performance and provide fault tolerance. This chapter describes how replication

works, what kinds of data can be replicated, common replication scenarios, and tips for

building a high-availability directory service.

6. Chapter 7 “Designing synchronization”

The informationstored in the HP-UX Directory Server can by synchronizedwith information

stored in Microsoft Active Directory databases for better integration with a mixed-platform

infrastructure. This chapter describes how synchronization works, what kinds of data can

be synched, and considerations for the type of information and locations in the directory

tree which are best for synchronization.

7. Chapter 8 “Designing a secure directory”

Finally, plan how to protect the data in the directory and design the other aspects of the

service to meet the security requirements of the users and applications. This chapter covers

common security threats, an overview of security methods, the steps involved in analyzing

security needs, and tips for designing access controls and protecting the integrity of the

directory data.

1.4.2 Deploying the directory

The first step to deploying the Directory Server is installing a test server instance to make sure

the service can handle the user load. If the service is not adequate in the initial configuration,

adjust the design and test it again. Adjust the design until it is a robust service that you can

confidently introduce to the enterprise.

14 Introduction to directory services

Page 15

For a comprehensive overview of creating and implementing a directory pilot, see Understanding

and Deploying LDAP Directory Services (T. Howes, M. Smith, G. Good, Macmillan Technical

Publishing, 1999).

After creating and tuning a successful test Directory Server instance, develop a plan to move the

directory service to production, covering the following considerations:

• An estimate of the required resources

• A schedule of what needs to be accomplished and when

• A set of criteria for measuring the success of the deployment

See the HP-UX Directory Server installation guide for information on installing the directory service

and the HP-UX Directory Server administrator guide for information on administering and

maintaining the directory.

1.5 Other general directory resources

The following publications have very detailed and useful information about directories, LDAP,

and LDIF:

• RFC 2849: The LDAP Data Interchange Format (LDIF) Technical Specification, http://

www.ietf.org/rfc/rfc2849.txt

• RFC 2251: Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (v3), http://www.ietf.org/rfc/rfc2251.txt

• Understanding and Deploying LDAP Directory Services. T. Howes, M. Smith, G. Good, Macmillan

Technical Publishing, 1999.

All the HP-UX Directory Server documentation, available at http://docs.hp.com/en/internet.html,

also contain high-level concepts about using LDAP and managing directory services, as well as

Directory Server-specific information.

1.5 Other general directory resources 15

Page 16

16

Page 17

2 Planning the directory data

The data stored in the directory may include user names, email addresses, telephone numbers,

and information about groups users are in, or it may contain other types of information. The

type of data in the directory determines how the directory is structured, who is given access to

the data, and how this access is requested and granted.

This chapter describes the issues and strategies behind planning the directory's data.

2.1 Introduction to directory data

Some types of data are better suited to the directory than others. Ideal data for a directory has

some of the following characteristics:

• It is read more often than written.

• It is expressible in attribute-data format (for example, surname=jensen).

• It is of interest to more than one person or group. For example, an employee's name or the

physical location of a printer can be of interest to many people and applications.

• It will be accessed from more than one physical location.

For example, an employee's preference settings for a software application may not seem to be

appropriate for the directory because only a single instance of the application needs access to

the information. However, if the application is capable of reading preferences from the directory

and users might want to interact with the application according to their preferences from different

sites, then it is very useful to include the preference information in the directory.

2.1.1 Information to include in the directory

Any descriptive or useful information about a person or asset can be added to an entry as an

attribute. For example:

• Contact information, such as telephone numbers, physical addresses, and email addresses.

• Descriptive information, such as an employee number, job title, manager or administrator

identification, and job-related interests.

• Organization contact information, such as a telephone number, physical address,

administrator identification, and business description.

• Device information, such as a printer's physical location, type of printer, and the number of

pages per minute that the printer can produce.

• Contact and billing information for a corporation's trading partners, clients, and customers.

• Contract information, such as the customer's name, due dates, job description, and pricing

information.

• Individual software preferences or software configuration information.

• Resource sites, such as pointers to web servers or the file system of a certain file or application.

Using the Directory Server for more than just server administration requires planning what other

types of information to store in the directory. For example:

• Contract or client account details

• Payroll data

• Physical device information

• Home contact information

• Office contact information for the various sites within the enterprise

2.1.2 Information to exclude from the directory

HP-UX Directory Server is excellent for managing large quantities of data that client applications

read and write, but it is not designed to handle large, unstructured objects, such as images or

2.1 Introduction to directory data 17

Page 18

other media. These objects should be maintained in a file system. However, the directory can

store pointers to these kinds of applications by using pointer URLs to FTP, HTTP, and other sites.

2.2 Defining directory needs

When designing the directory data, think not only of the data that is currently required but also

how the directory (and organization) is going to change over time. Considering the future needs

of the directory during the design process influences how the data in the directory are structured

and distributed.

Look at these points:

• What should be put in the directory today?

• What immediate problem is solved by deploying a directory?

• What are the immediate needs of the directory-enabled application being used?

• What information is going to be added to the directory in the near future? For example, an

enterprise might use an accounting package that does not currently support LDAP but will

be LDAP-enabled in a few months. Identify the data used by LDAP-compatible applications,

and plan for the migration of the data into the directory as the technology becomes available.

• What information might be stored in the directory in the future? For example, a hosting

company may have future customers with different data requirements than their current

customers, such as needing to store images or media files. While this is the hardest answer

to anticipate, doing so may pay off in unexpected ways. At a minimum, this kind of planning

helps identify data sources that might not otherwise have been considered.

2.3 Performing a site survey

A site survey is a formal method for discovering and characterizing the contents of the directory.

Budget plenty of time for performing a site survey, as preparation is the key to the directory

architecture. The site survey consists of a number of tasks:

• Identify the applications that use the directory.

Determine the directory-enabled applications deployed across the enterprise and their data

needs.

• Identify data sources.

Survey the enterprise and identify sources of data, such as Active Directory, other LDAP

servers, PBX systems, human resources databases, and email systems.

• Characterize the data the directory needs to contain.

Determine what objects should be present in the directory (for example, people or groups)

and what attributes of these objects to maintain in the directory (such as usernames and

passwords).

• Determine the level of service to provide.

Decide how available the directory data needs to be to client applications, and design the

architecture accordingly. How available the directory needs to be affects how data are

replicated and how chaining policies are configured to connect data stored on remote servers.

See Chapter 6 “Designing the replication process” for more information about replication

and “Topology overview” for more information on chaining.

• Identify a data master.

A data master contains the primary source for directory data. This data might be mirrored

to other servers for load balancing and recovery purposes. For each piece of data, determine

its data master.

18 Planning the directory data

Page 19

• Determine data ownership.

For each piece of data, determine the person responsible for ensuring that the data is

up-to-date.

• Determine data access.

If data are imported from other sources, develop a strategy for both bulk imports and

incremental updates. As a part of this strategy, try to master data in a single place, and limit

the number of applications that can change the data. Also, limit the number of people who

write to any given piece of data. A smaller group ensures data integrity while reducing the

administrative overhead.

• Document the site survey.

Because of the number of organizations that can be affected by the directory, it may be helpful

to create a directory deployment team that includes representatives from each affected

organization to perform the site survey.

Corporations generally have a human resources department, an accounting or accounts receivable

department, manufacturing organizations, sales organizations, and development organizations.

Including representatives from each of these organizations can help the survey process.

Furthermore, directly involving all the affected organizations can help build acceptance for the

migration from local data stores to a centralized directory.

2.3.1 Identifying the applications that use the directory

Generally, the applications that access the directory and the data needs of these applications

drive the planning of the directory contents. Many common applications use the directory:

• Directory browser applications, such as online telephone books

Decide whatinformation (such as email addresses, telephone numbers, and employee name)

users need, and include it in the directory.

• Email applications, especially email servers

All email servers require email addresses, user names, and some routing information to be

available in the directory. Others, however, require more advanced information such as the

place on disk where a user's mailbox is stored, vacation notification information, and protocol

information (IMAP versus POP, for example).

• Directory-enabled human resources applications

These require more personal information such as government identification numbers, home

addresses, home telephone numbers, birth dates, salary, and job title.

• Microsoft Active Directory

Through Windows User Sync, Windows directory services can be integrated to function in

tandem with the Directory Server. Both directories can store user information (user names

and passwords, email addresses, telephone numbers) and group information (members).

Style the Directory Server deployment after the existing Windows server deployment (or

vice versa) so that the users, groups, and other directory data can be smoothly synchronized.

When examining the applications that will use the directory, look at the types of information

each application uses. The following table gives an example of applications and the information

used by each:

2.3 Performing a site survey 19

Page 20

Table 2-1 Example application data needs

DataClass of dataApplication

PeoplePhonebook

People, groupsWeb server

After identifying the applications and information used by each application, it is apparent that

some types of data are used by more than one application. Performing this kind of exercise during

the data planning stage can help to avoid data redundancy problems in the directory, and show

more clearly what data directory-dependent applications require.

The final decision about the types of data maintained in the directory and when the information

is migrated to the directory is affected by these factors:

• The data required by various legacy applications and users

• The ability of legacy applications to communicate with an LDAP directory

2.3.2 Identifying data sources

To identify all the data to include in the directory, perform a survey of the existing data stores.

The survey should include the following:

• Identify organizations that provide information.

Locate all the organizations that manage information essential to the enterprise. Typically,

this includesthe information services, humanresources, payroll, and accounting departments.

Name, email address, phone number, user ID, password,

department number, manager, mail stop.

User ID,password, group name, groups members, group

owner.

Name, user ID, cube number, conference room name.People, meeting roomsCalendar server

• Identify the tools and processes that are information sources.

Some common sources for information are networking operating systems (Windows, Novell

Netware, UNIX NIS), email systems, security systems, PBX (telephone switching) systems,

and human resources applications.

• Determine how centralizing each piece of data affects the management of data.

Centralized data management can require new tools and new processes. Sometimes

centralization requires increasing staff in some organizations while decreasing staff in others.

During the survey, consider developing a matrix that identifies all the information sources in

the enterprise, similar to Table 2-2 “ Example information sources”:

Table 2-2 Example information sources

PeopleHuman resources database

People, GroupsEmail system

2.3.3 Characterizing the directory data

DataClass of dataData source

Name, address, phone number, department number,

manager.

Name, email address, user ID, password, email

preferences.

Building names,floor names, cube numbers, access codes.FacilitiesFacilities system

All the data identified to include in the directory can be characterized according to the following

general points:

• Format

• Size

• Number of occurrences in various applications

20 Planning the directory data

Page 21

• Data owner

• Relationship to other directory data

Study each kind of data to include in the directory to determine what characteristics it shares

with the other pieces of data. This helps save time during the schema design stage, described in

more detail in Chapter 3 “Designing the directory schema”.

A good idea is to use a table, similar to Table 2-3 “Directory data characteristics”, which

characterizes the directory data.

Table 2-3 Directory data characteristics

2.3.4 Determining level of service

The level of service provided depends on the expectations of the people who rely on

directory-enabled applications. To determine the level of service each application expects, first

determine how and when the application is used.

As the directory evolves, it may need to support a wide variety of service levels, from production

to mission critical. It can be difficult raising the level of service after the directory is deployed,

so make sure the initial design can meet the future needs.

For example, if the risk of total failure must be eliminated, use a multi-master configuration,

where several suppliers exist for the same data.

Related toOwnerSizeFormatData

User's entryHuman resources128 charactersText stringEmployee Name

User's entryFacilities14 digitsPhone numberFax number

User's entryIS departmentMany charactersTextEmail address

2.3.5 Considering a data master

A data master is a server that is the master source of data. Any time the same information is

stored in multiple locations, the data integrity can be degraded. A data master makes sure all

information stored in multiple locations is consistent and accurate. There are several scenarios

that require a data master:

• Replication among Directory Servers

• Synchronization between Directory Server and Active Directory

• Independent client applications which access the Directory Server data

Consider the master source of the data if there are applications that communicate indirectly with

the directory. Keep the processes for changing data, and the places from which the data can be

changed, as simple as possible. After deciding on a single site to master a piece of data, use the

same site to master all the other data contained there. A single site simplifies troubleshooting if

the databases lose synchronization across the enterprise.

There are different ways to implement data mastering:

• Master the data in both the directory and all applications that do not use the directory.

Maintaining multiple data masters does not require custom scripts for moving data in and

out of the directory and the other applications. However, if data changes in one place,

someone has to change it on all the other sites. Maintaining master data in the directory and

2.3 Performing a site survey 21

Page 22

all applications not using the directory can result in data being unsynchronized across the

enterprise (which is what the directory is supposed to prevent).

• Master the data in some application other than the directory, then write scripts, programs,

or gateways to import that data into the directory.

Mastering data in non-directory applications makes the most sense if there are one or two

applications that are already used to master data, and the directory will be used only for

lookups (for example, for online corporate telephone books).

How master copiesof the data are maintained depends on the specificdirectory needs. However,

regardless of how data masters are maintained, keep it simple and consistent. For example, do

not attempt to master data in multiple sites, then automatically exchange data between competing

applications. Doing so leads to a "last change wins" scenario and increases the administrative

overhead.

For example, the directory is going to manage an employee's home telephone number. Both the

LDAP directory and a human resources database store this information. The human resources

application is LDAP-enabled, so an application can be written that automatically transfers data

from the LDAP directory to the human resources database, and vice versa.

Attempting to master changes to that employee's telephone number in both the LDAP directory

and the human resources data, however, means that the last place where the telephone number

was changed overwrites the information in the other database. This is only acceptable as long

as the last application to write the data had the correct information.

If that information was out of date, perhaps because the human resources data were reloaded

from a backup, then the correct telephone number in the LDAP directory will be deleted.

With multi-mater replication, Directory Server can contain master sources of information on

more than one server. Multiple masters keep changelogs and can resolve conflicts more safely.

A limited number of Directory Server are considered masters which can accept changes; they

then replicate the data to replica servers, or consumer servers.1Having more than on data master

server provides safe failover in the event that a server goes off-line. For more information about

replication and multi-master replication, see Chapter 6 “Designing the replication process”.

Synchronization allows Directory Server users, groups, attributes, and passwords to be integrated

with Microsoft Active Directory users, groups, attributes, and passwords. With two directory

services, decide whether they will handle the same information, what amount of that information

will be shared, and which service will be the data master for that information. The best course

is to choose a single application to master the data and allow the synchronization process to add,

update, or delete the entries on the other service.

2.3.6 Determining data ownership

Data ownership refers to the person or organization responsible for making sure the data is

up-to-date. During the data design phase, decide who can write data to the directory. The

following are some common strategies for deciding data ownership:

• Allow read-only access to the directory for everyone except a small group of directory content

managers.

• Allow individual users to manage some strategic subset of information for themselves.

This subset of information might include their passwords, descriptive information about

themselves and their role within the organization, their automobile license plate number,

and contact information such as telephone numbers or office numbers.

• Allow a person's manager to write to some strategic subset of that person's information,

such as contact information or job title.

1. In replication, a consumer server or replica server is a server that receives updates from a supplier server or hub

server.

22 Planning the directory data

Page 23

• Allow an organization's administrator to create and manage entries for that organization.

This approach allows an organization's administrators to function as the directory content

managers.

• Create roles that give groups of people read or write access privileges.

For example, there can be roles created for human resources, finance, or accounting. Allow

each of these roles to have read access, write access, or both to the data needed by the group.

This could include salary information, government identification numbers, and home phone

numbers and address.

For more information about roles and grouping entries, see “Grouping directory entries”.

There may be multiple individuals who need to have write access to the same information. For

example, an information systems (IS) or directory management group probably requires write

access to employee passwords. It may also be desirable for employees themselves to have write