Page 1

Principles, testing methods and applications

EARTH GROUNDING

RESISTANCE

EARTH GROUNDING

RESISTANCE

EARTH GROUNDING

RESISTANCE

EARTH GROUNDING

RESISTANCE

DIAGNOSE intermittent electrical problems

AVOID unnecessary downtime

LEARN earth ground safety principles

Page 2

Why ground, why test?

Why ground?

Poor grounding not only contributes to

unnecessary downtime, but a lack of good

grounding is also dangerous and increases

the risk of equipment failure.

Without an effective grounding system,

we could be exposed to the risk of electric

shock, not to mention instrumentation errors,

harmonic distortion issues, power factor

problems and a host of possible intermittent

dilemmas. If fault currents have no path to

the ground through a properly designed and

maintained grounding system, they will find

unintended paths that could include people.

The following organizations have recommendations and/or standards for grounding

to ensure safety:

• OSHA (Occupational Safety Health

Administration)

• NFPA (National Fire Protection Association)

• ANSI/ISA (American National Standards

Institute and Instrument Society of America)

• TIA (Telecommunications Industry

Association)

• IEC (International Electrotechnical

Commission)

• CENELEC (European Committee for

Electrotechnical Standardization)

• IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics

Engineers)

However, good grounding isn’t only for

safety; it is also used to prevent damage to

industrial plants and equipment. A good

grounding system will improve the reliability

of equipment and reduce the likelihood of

damage due to lightning or fault currents.

Billions are lost each year in the workplace

due to electrical fires. This does not account

for related litigation costs and loss of personal and corporate productivity.

Why test

grounding systems?

Over time, corrosive soils with high moisture content, high salt content, and high

temperatures can degrade ground rods and

their connections. So although the ground

system, when initially installed, had low earth

ground resistance values, the resistance of the

grounding system can increase if the ground

rods are eaten away.

Grounding testers, like the Fluke 1623-2 and

1625-2, are indispensable troubleshooting tools

to help you maintain uptime. With frustrating,

intermittent electrical problems, the problem

could be related to poor grounding or poor

power quality.

That is why it is highly recommended that all

grounds and ground connections are checked

at least annually as a part of your normal Predictive Maintenance plan. During these periodic

checks, if an increase in resistance of more

than 20 % is measured, the technician should

investigate the source of the problem, and

make the correction to lower the resistance, by

replacing or adding ground rods to the ground

system.

What is a ground

and what does it do?

The NEC, National Electrical Code, Article 100

defines a ground as: “a conducting connection,

whether intentional or accidental between an

electrical circuit or equipment and the earth, or

to some conducting body that serves in place of

the earth.” When talking about grounding, it is

actually two different subjects: earth grounding

and equipment grounding. Earth grounding is an

intentional connection from a circuit conductor,

usually the neutral, to a ground electrode placed

in the earth. Equipment grounding ensures that

operating equipment within a structure is properly grounded. These two grounding systems are

required to be kept separate except for a connection between the two systems. This prevents

differences in voltage potential from a possible

flashover from lightning strikes. The purpose of a

ground besides the protection of people, plants

and equipment is to provide a safe path for the

dissipation of fault currents, lightning strikes,

static discharges, EMI and RFI signals and interference.

2

Page 3

What is a good ground

resistance value?

There is a good deal of confusion as to what

constitutes a good ground and what the ground

resistance value needs to be. Ideally a ground

should be of zero ohms resistance.

There is not one standard ground resistance

threshold that is recognized by all agencies.

However, the NFPA and IEEE have recommended a ground resistance value of 5.0 ohms

or less.

The NEC has stated to “Make sure that system

impedance to ground is less than 25 ohms

specified in NEC 250.56. In facilities with sensitive equipment it should be 5.0 ohms or less.”

The Telecommunications industry has

often used 5.0 ohms or less as their value for

grounding and bonding.

The goal in ground resistance is to achieve

the lowest ground resistance value possible

that makes sense economically and physically.

Table of

contents

2

Why ground?

Why test?

4

Why test? Corrosive soils.

Grounding basics

6

Methods of earth

ground testing

Why ground? Lightning strikes.

Use the Fluke 1625-2 to determine the

health of your earth ground systems.

12

Measuring

ground resistance

3

Page 4

Grounding basics

Components of a

ground electrode

• Ground conductor

• Connection between the ground conductor

and the ground electrode

• Ground electrode

Locations of resistances

(a) The ground electrode and its connection

The resistance of the ground electrode and

its connection is generally very low. Ground

rods are generally made of highly conductive/low resistance material such as steel

or copper.

(b) The contact resistance of the surrounding

earth to the electrode

The National Institute of Standards (a gov-

ernmental agency within the US Dept. of

Commerce) has shown this resistance to be

almost negligible provided that the ground

electrode is free of paint, grease, etc. and

that the ground electrode is in firm contact

with the earth.

(c) The resistance of the surrounding

body of earth

The ground electrode is surrounded by earth

which conceptually is made up of concentric shells all having the same thickness.

Those shells closest to the ground electrode

have the smallest amount of area resulting

in the greatest degree of resistance. Each

subsequent shell incorporates a greater area

resulting in lower resistance. This finally

reaches a point where the additional shells

offer little resistance to the ground surrounding the ground electrode.

What affects the

grounding resistance?

First, the NEC code (1987, 250-83-3) requires a

minimum ground electrode length of 2.5 meters

(8.0 feet) to be in contact with soil. But, there are

four variables that affect the ground resistance of

a ground system:

1. Length/depth of the ground electrode

2. Diameter of the ground electrode

3. Number of ground electrodes

4. Ground system design

Length/depth of the ground electrode

One very effective way of lowering ground

resistance is to drive ground electrodes deeper.

Soil is not consistent in its resistivity and can

be highly unpredictable. It is critical when

installing the ground electrode that it is below

the frost line. This is done so that the resistance

to ground will not be greatly influenced by the

freezing of the surrounding soil.

Generally, by doubling the length of the

ground electrode you can reduce the resistance

level by an additional 40 %. There are occasions where it is physically impossible to drive

ground rods deeper—areas that are composed of

rock, granite, etc. In these instances, alternative

methods including grounding cement are viable.

Diameter of the ground electrode

Increasing the diameter of the ground electrode

has very little effect in lowering the resistance.

For example, you could double the diameter of a

ground electrode and your resistance would only

decrease by 10 %.

So based on this information, we should focus

on ways to reduce the ground resistance when

installing grounding systems.

4

Page 5

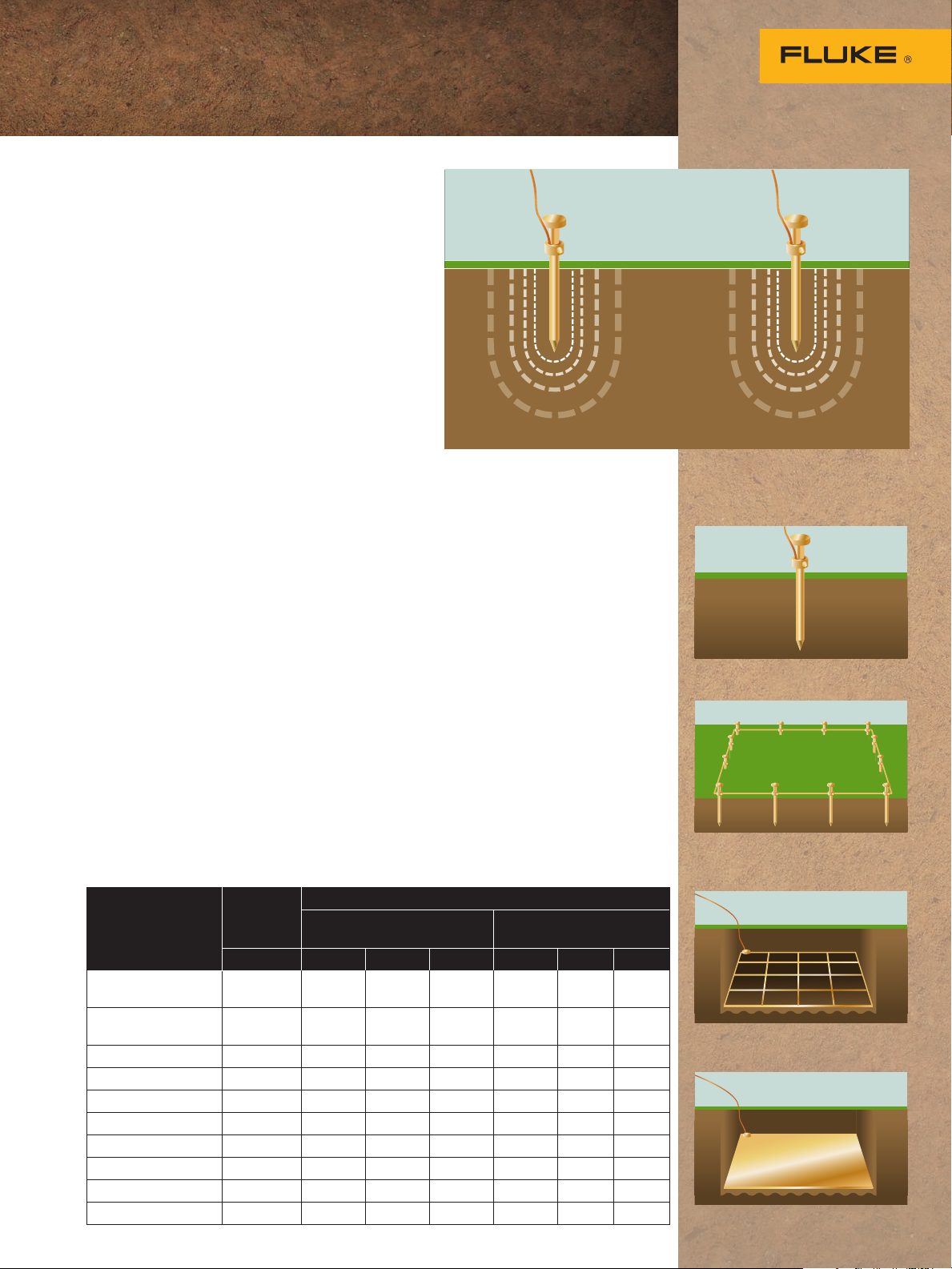

Number of ground electrodes

Another way to lower ground resistance is to use

multiple ground electrodes. In this design, more

than one electrode is driven into the ground and

connected in parallel to lower the resistance. For

additional electrodes to be effective, the spacing

of additional rods need to be at least equal to

the depth of the driven rod. Without proper

spacing of the ground electrodes, their spheres

of influence will intersect and the resistance will

not be lowered.

To assist you in installing a ground rod that

will meet your specific resistance requirements,

you can use the table of ground resistances,

below. Remember, this is to only be used as a

rule of thumb, because soil is in layers and is

rarely homogenous. The resistance values

will vary greatly.

Ground system design

Simple grounding systems consist of a single

ground electrode driven into the ground. The use

of a single ground electrode is the most common

form of grounding and can be found outside your

home or place of business. Complex grounding

systems consist of multiple ground rods, connected, mesh or grid networks, ground plates,

and ground loops. These systems are typically

installed at power generating substations, central offices, and cell tower sites.

Complex networks dramatically increase the

amount of contact with the surrounding earth

and lower ground resistances.

Each ground electrode has its own

‘sphere of influence’.

Ground

systems

Single ground electrode

Soil

Type

of soil

Very moist soil,

swamplike

Farming soil, loamy

and clay soils

Sandy clay soil 150 50 25 15 60 30 15

Moist sandy soil 300 66 33 20 80 40 20

Concrete 1:5 400 - - - 160 80 40

Moist gravel 500 16 0 80 48 200 100 50

Dry sandy soil 1000 330 165 100 400 200 100

Dry gravel 1000 330 16 5 100 400 200 100

Stoney soil 30,000 1000 500 300 120 0 600 300

Rock 10

resistivity

R

E

ΩM 3 6 10 5 10 20

30 10 5 3 12 6 3

100 33 17 10 40 20 10

7

Ground electrode depth

- - - - - -

Earthing resistance

(meters)

Earthing strip

(meters)

Multiple ground electrodes

connected

Mesh network

Ground plate

5

Page 6

What are the methods of earth ground testing?

There are four types of earth ground testing

methods available:

• Soil Resistivity (using stakes)

• Fall-of-Potential (using stakes)

• Selective (using 1 clamp and stakes)

• Stakeless (using 2 clamps only)

Soil resistivity

measurement

Why determine the soil resistivity?

Soil Resistivity is most necessary when determining the design of the grounding system for

new installations (green field applications) to

meet your ground resistance requirements.

Ideally, you would find a location with the

lowest possible resistance. But as we discussed

before, poor soil conditions can be overcome

with more elaborate grounding systems.

The soil composition, moisture content, and

temperature all impact the soil resistivity. Soil

is rarely homogenous and the resistivity of the

soil will vary geographically and at different

soil depths. Moisture content changes seasonally, varies according to the nature of the sub

layers of earth, and the depth of the permanent

water table. Since soil and water are generally

more stable at deeper strata, it is recommended

that the ground rods be placed as deep as

possible into the earth, at the water table if

possible. Also, ground rods should be installed

where there is a stable temperature, i.e. below

the frost line.

For a grounding system to be effective, it

should be designed to withstand the worst

possible conditions.

How do I calculate soil resistivity?

The measuring procedure described below

uses the universally accepted Wenner method

developed by Dr. Frank Wenner of the US Bureau

of Standards in 1915. (F. Wenner, A Method

of Measuring Earth Resistivity; Bull, National

Bureau of Standards, Bull 12(4) 258, p. 478496; 1915/16.)

The formula is as follows:

r = 2 π A R

(r = the average soil resistivity to depth A in ohm—cm)

π = 3.1416

A = the distance between the electrodes in cm

R = the measured resistance value in ohms from

the test instrument

Note: Divide ohm—centimeters by 100 to

convert to ohm—meters. Just watch

your units.

Example: You have decided to install

three meter long ground rods as part of

your grounding system. To measure the

soil resistivity at a depth of three meters,

we discussed a spacing between the test

electrodes of nine meters.

To measure the soil resistivity start the

Fluke 1625-2 and read the resistance

value in ohms. In this case assume the

resistance reading is 100 ohms. So, in

this case we know:

A = 9 meters, and

R = 100 ohms

Then the soil resistivity would equal:

r = 2 x π x A x R

r = 2 x 3.1416 x 9 meters x 100 ohms

r = 5655 Ωm

6

Page 7

aaa

1/3 a

H/C2

OFF

3

POLE

4

POLE

4

POLE

2

POLE

S/P2

ES/P1

E/C1

START

TEST

DISPLAY

MENU

CHANGE

ITEM

SELECT

1625-2

ADVANCED EARTH / GROUND TESTER GEO

E S HES

AC

Rresistance

300kΩEarth/Ground Resistance 300kΩ

DC

Resistance 3kΩ

RA

R

—

R

~

2

POLE

3

POLE

3

POLE

4

POLE

How do I measure soil resistance?

To test soil resistivity, connect the ground tester

as shown below.

As you can see, four earth ground stakes are

positioned in the soil in a straight line, equidistant from one another. The distance between

earth ground stakes should be at least three

times greater than the stake depth. So if the

depth of each ground stake is one foot (30 centimeters), make sure the distance between stakes

is greater than three feet (91 centimeters).

The Fluke 1625-2 generates a known current

through the two outer ground stakes and the

drop in voltage potential is measured between

the two inner ground stakes. Using Ohm’s Law

(V = IR), the Fluke tester automatically calculates

the soil resistance.

Because measurement results are often distorted and invalidated by underground pieces

of metal, underground aquifers, etc. additional

measurements where the stake’s axis are

turned 90 degrees is always recommended. By

changing the depth and distance several times,

a profile is produced that can determine a suitable ground resistance system.

Soil resistivity measurements are often corrupted by the existence of ground currents and

their harmonics. To prevent this from occurring,

the Fluke 1625-2 uses an Automatic Frequency

Control (AFC) System. This automatically selects

the testing frequency with the least amount of

noise enabling you to get a clear reading.

Setup for soil resistivity testing using the Fluke 1623-2 or

1625-2 .

7

Page 8

What are the methods of earth ground testing?

ADVANCED EARTH / GROUND TESTER GEO

1625-2

Earth

electrode

>20 m (65 ft) >20 m (65 ft)

Inner

stake

START

TEST

DISPLAY

MENU

CHANGE

ITEM

SELECT

H/C2

S/P2

E S H

AC

Rresistance

DC

300kΩEarth/Ground Resistance 300kΩ

Resistance 3kΩ

—

RA

R

~

R

4

3

POLE

POLE

2

3

POLE

POLE

2

4

POLE

POLE

4

3

ES/P1

POLE

POLE

OFF

E/C1

Outer

stake

Fall-of-Potential

measurement

The Fall-of-Potential test method is used to

measure the ability of an earth ground system or

an individual electrode to dissipate energy from

a site.

How does the Fall-of-Potential

test work?

First, the earth electrode of interest must be

disconnected from its connection to the site.

Second, the tester is connected to the earth

electrode. Then, for the 3-pole Fall-of-Potential

test, two earth stakes are placed in the soil in a

direct line—away from the earth electrode. Normally, spacing of 20 meters (65 feet) is sufficient.

For more detail on placing the stakes, see the

next section.

A known current is generated by the Fluke

1625-2 between the outer stake (auxiliary earth

stake) and the earth electrode, while the drop in

voltage potential is measured between the inner

earth stake and the earth electrode. Using Ohm’s

Law (V = IR), the tester automatically calculates

the resistance of the earth electrode.

Connect the ground tester as shown in

the picture. Press START and read out the RE

(resistance) value. This is the actual value of

the ground electrode under test. If this ground

electrode is in parallel or series with other

ground rods, the RE value is the total value of

all resistances.

How do you place the stakes?

To achieve the highest degree of accuracy when

performing a 3–pole ground resistance test,

it is essential that the probe is placed outside

the sphere of influence of the ground electrode

under test and the auxiliary earth.

If you do not get outside the sphere of influence, the effective areas of resistance will

overlap and invalidate any measurements that

you are taking. The table is a guide for appropriately setting the probe (inner stake) and

auxiliary ground (outer stake).

To test the accuracy of the results and to

ensure that the ground stakes are outside the

spheres of influence, reposition the inner stake

(probe) 1 meter (3 feet) in either direction and

take a fresh measurement. If there is a significant change in the reading (30 %), you need

to increase the distance between the ground

rod under test, the inner stake (probe) and the

outer stake (auxiliary ground) until the measured

values remain fairly constant when repositioning

the inner stake (probe).

Depth of

the ground

electrode

2 m 15 m 25 m

3 m 20 m 30 m

6 m 25 m 40 m

10 m 30 m 50 m

Distance

to the

inner stake

Distance

to the

outer stake

8

Page 9

Selective measurement

Selective testing is very similar to the

Fall-of-Potential testing, providing all the same

measurements, but in a much safer and easier

way. This is because with Selective testing, the

earth electrode of interest does not need to be

disconnected from its connection to the site! The

technician does not have to endanger himself

by disconnecting ground, nor endanger other

personnel or electrical equipment inside a nongrounded structure.

Just as with the Fall-of-Potential test, two

earth stakes are placed in the soil in a direct

line, away from the earth electrode. Normally,

spacing of 20 meters (65 feet) is sufficient. The

tester is then connected to the earth electrode

of interest, with the advantage that the connection to the site doesn’t need to be disconnected.

Instead, a special clamp is placed around the

earth electrode, which eliminates the effects of

parallel resistances in a grounded system, so

only the earth electrode of interest is measured.

Just as before, a known current is generated

by the Fluke 1625-2 between the outer stake

(auxiliary earth stake) and the earth electrode,

while the drop in voltage potential is measured

between the inner earth stake and the earth

electrode. Only the current flowing through the

earth electrode of interest is measured using

the clamp. The generated current will also flow

through other parallel resistances, but only

the current through the clamp (i.e. the current

through the earth electrode of interest) is used to

calculate resistance (V = IR).

If the total resistance of the ground system

should be measured, then each earth electrode

resistance must be measured by placing the

clamp around each individual earth electrode.

Then the total resistance of the ground system

can be determined by calculation.

Testing individual ground electrode resistances of high

voltage transmission towers with overhead ground or static

wire, requires that these wires be disconnected. If a tower

has more than one ground at its base, these must also be

disconnected one by one and tested. However, the Fluke

1625-2 has an optional accessory, a 320 mm (12.7 in)

diameter clamp-on current transformer, which can measure

the individual resistances of each leg, without disconnecting any ground leads or overhead static/ground wires.

Connect the ground tester as

shown. Press START and read out

the RE value. This is the actual

resistance value of the ground

electrode under test.

9

Page 10

What are the methods of earth ground testing?

Stakeless measurement

The Fluke 1625-2 earth ground tester is able to

ON

OFF

ON

OFF

ON

OFF

ON

OFF

ON

OFF

ON

OFF

ON

OFF

ON

OFF

ON

OFF

Source

E

IN

TRA

I-1

DUCING CU

NS

62

FO

AC

RM

E

RRE

R

N

T

Measure

EI-1

S

ENS

T

62

RA

I

N

X

N

G

S

CURRE

F

O

RMER

N

ADVANCED EARTH / GROUND TESTER GEO

1625-2

START

H/C2

TEST

DISPLAY

S/P2

E S H

MENU

AC

DC

Rresistance

Resistance 3kΩ

Earth/Ground Resistance 300kΩ

300kΩ

—

RA

R

~

R

4

3

POLE

POLE

2

3

POLE

POLE

2

4

POLE

POLE

4

3

CHANGE

ES/P1

POLE

POLE

ITEM

OFF

E/C1

T

SELEC

T

Test current paths in the stakeless method.

ADVANCED EARTH / GROUND TESTER GEO

1625-2

START

TEST

DISPLAY

MENU

RA

3

POLE

3

POLE

4

POLE

3

CHANGE

POLE

ITEM

OFF

SELECT

POLE

E S H

Rresistance

300kΩEarth/Ground Resistance 300kΩ

R

4

POLE

H/C2

S/P2

AC

DC

Resistance 3kΩ

—

R

~

2

2

POLE

4

ES/P1

POLE

E/C1

TRANSFORMER

INDUCING CURRENT

EI-162AC

TRANSFORMER

SENSING CURRENT

EI-162X

measure earth ground loop resistances for multigrounded systems using only current clamps.

This test technique eliminates the dangerous

and time consuming activity of disconnecting

parallel grounds, as well as the process of

finding suitable locations for auxiliary ground

stakes. You can also perform earth ground tests

in places you have not considered before: inside

buildings, on power pylons or anywhere you

don’t have access to soil.

With this test method, two clamps are placed

around the earth ground rod or the connecting

cable and each are connected to the tester.

Earth ground stakes are not used at all. A known

voltage is induced by one clamp, and the current

is measured using the second clamp. The tester

automatically determines the ground loop resistance at this ground rod. If there is only one path

to ground, like at many residential situations, the

Stakeless method will not provide an acceptable

value and the Fall-of-Potential test method must

be used.

The Fluke 1625-2 works on the principle that

in parallel/multi-grounded systems, the net

resistance of all ground paths will be extremely

low as compared to any single path (the one

under test). So, the net resistance of all the

parallel return path resistances is effectively

zero. Stakeless measurement only measures

individual ground rod resistances in parallel to

earth grounding systems. If the ground system

is not parallel to earth then you will either have

an open circuit, or be measuring ground loop

resistance.

Setup for the stakeless method

using the 1625-2.

10

>10 cm (4 in)

Page 11

Ground impedance measurements

When attempting to calculate possible short

circuit currents in power plants and other high

voltage/current situations, determining the complex grounding impedance is important since

the impedance will be made up of inductive

and capacitive elements. Because inductivity

and resistivity are known in most cases, actual

impedance can be determined using a complex

computation.

Since impedance is frequency dependent,

the Fluke 1625-2 uses a 55 Hz signal for this

calculation to be as close to voltage operating

frequency as possible. This ensures that the

measurement is close to the value at the true

operating frequency. Using this feature of the

Fluke 1625-2, accurate direct measurement of

grounding impedance is possible.

Power utilities technicians, testing high voltage

transmission lines, are interested in two things:

the ground resistance in case of a lightning

strike, and the impedance of the entire system

in case of a short circuit on a specific point in the

line. Short circuit, in this case, means an active

wire breaks loose and touches the metal grid of

a tower.

Two-pole ground resistance

In situations where the driving of ground stakes is neither

practical nor possible, the Fluke 1623-2 and 1625-2 testers give you the ability to do two-pole ground resistance/

continuity measurements, as shown below.

To perform this test, the technician must have access to a

good, known ground such as an all metal water pipe. The

water pipe should be extensive enough and be metallic

throughout without any insulating couplings or flanges.

Unlike many testers, the Fluke 1623-2 and 1625-2 perform the test with a relatively high current (short circuit

current > 250 mA) ensuring stable results.

ADVANCED EARTH / GROUND TESTER GEO

1625-2

START

ST

TEST

DISPLAY

MENU

RA

3

POLE

3

POLE

4

POLE

3

CHANGE

POLE

ITEM

OFF

SELECT

H/C2

S/P2

SES

AC

Rresistance

DC

Resistance 3kΩ

300kΩEarth/Ground Resistance 300kΩ

—

R

~

R

4

POLE

2

POLE

2

POLE

4

ES/P1

POLE

E/C1

Equivalent circuit for

two-point measurement.

11

Page 12

Measuring ground resistance

MGB

MGN

Building

steel

The layout of a typical central office.

At central offices

When conducting a grounding audit of a central

office there are three different measurements

required.

Before testing, locate the MGB (Master Ground

Bar) within the central office to determine the

type of grounding system that exists. As shown

on this page, the MGB will have ground leads

connecting to the:

• MGN (Multi-Grounded Neutral) or incoming

service,

• ground field,

• water pipe, and

• structural or building steel

Ground

field

Water pipe

First, perform the Stakeless test on all the

individual grounds coming off of the MGB. The

purpose is to ensure that all the grounds are

connected, especially the MGN. It is important to

note that you are not measuring the individual

resistance, rather the loop resistance of what

you are clamped around. As shown in Figure 1,

connect the Fluke 1625-2 or 1623-2 and both

the inducing and sensing clamps, which are

placed around each connection to measure the

loop resistance of the MGN, the ground field, the

water pipe, and the building steel.

Second, perform the 3-pole Fall-of-Potential

test of the entire ground system, connecting

to the MGB as illustrated in Figure 2. To get to

remote earth, many phone companies utilize

unused cable pairs going out as much as a mile.

Record the measurement and repeat this test at

least annually.

Third, measure the individual resistances of

the ground system using the Selective test of

the Fluke 1625-2 or 1623-2. Connect the Fluke

tester, as shown in Figure 3. Measure the resistance of the MGN; the value is the resistance of

that particular leg of the MGB. Then measure

the ground field. This reading is the actual

resistance value of the central office ground

field. Now move on to the water pipe, and then

repeat for the resistance of the building steel.

You can easily verify the accuracy of these

measurements through Ohm’s Law. The resistance of the individual legs, when calculated,

should equal the resistance of the entire system

given (allow for reasonable error since all

ground elements may not be measured).

These test methods provide the most accurate

measure of a central office, because it gives

you the individual resistances and their actual

behavior in a ground system. Although accurate, the measurements would not show how

the system behaves as a network, because in

the event of a lightning strike or fault current,

everything is connected.

12

Page 13

To prove this, you need to perform a few

EI-16

2AC

I

NDUC

I

N

G

CURRENT

TRANS

FO

RMER

EI-162AC

IN

DU

CING CURR

ENT

TRANSFORMER

EI-162AC

INDUCING CURRENT

TR

ANSFORMER

additional tests on individual resistances.

First, perform the 3-pole Fall-of-Potential

test on each leg off the MGB and record each

measurement. Using Ohm’s Law again, these

measurements should be equal to the resistance

of the entire system. From the calculations you

will see that you are from 20 % to 30 % off the

total RE value.

Finally, measure the resistances of the

various legs of the MGB using the Selective

Stakeless method. It works like the Stakeless

method, but it differs in the way we use the

two separate clamps. We place the inducing

voltage clamp around the cable going to the

MGB, and since the MGB is connected to the

incoming power, which is parallel to the earth

system, we have achieved that requirement.

Take the sensing clamp and place it around the

ground cable leading out to the ground field.

When we measure the resistance, this is the

actual resistance of the ground field, plus the

parallel path of the MGB. And because it should

be very low ohmically, it should have no real

effect on the measured reading. This process can

be repeated for the other legs of the ground bar

i.e. water pipe and structural steel.

To measure the MGB via the Stakeless Selective method, place the inducing voltage clamp

around the line to the water pipe (since the

copper water pipe should have very low resistance) and your reading will be the resistance

for only the MGN.

ADVANCED EARTH / GROUND TESTER GEO

1625-2

START

TEST

DISPLAY

MENU

RA

3

POLE

POLE

3

POLE

4

POLE

3

CHANGE

POLE

ITEM

OFF

SELECT

Figure 1: Stakeless testing

of a central office.

ADVANCED EARTH / GROUND TESTER GEO

1625-2

MGN

START

TEST

DISPLAY

MENU

CHANGE

ITEM

SELECT

H/C2

S/P2

E S H

AC

Rresistance

DC

300kΩEarth/Ground Resistance 300kΩ

Resistance 3kΩ

—

RA

R

~

R

4

3

POLE

POLE

2

3

POLE

POLE

2

4

POLE

POLE

4

3

ES/P1

POLE

POLE

OFF

E/C1

MGB

E S H

4

H/C2

S/P2

AC

DC

Rresistance

300kΩEarth/Ground Resistance 300kΩ

Resistance 3kΩ

—

R

~

R

2

POLE

2

POLE

4

ES/P1

POLE

E/C1

TRANSFORMER

INDUCING CURRENT

EI-162AC

TRANSFORMER

SENSING CURRENT

EI-162X

MGB

MGN

Figure 2: Perform

the 3-Pole

Fall-of-Potential

test of the entire

ground system.

Figure 3:

START

TEST

DISPLAY

MENU

CHANGE

ITEM

SELECT

ADVANCED EARTH / GROUND TESTER GEO

1625-2

RA

3

POLE

3

POLE

4

POLE

3

POLE

OFF

H/C2

S/P2

E S H

AC

Rresistance

DC

300kΩEarth/Ground Resistance 300kΩ

Resistance 3kΩ

—

R

~

R

4

POLE

2

POLE

2

POLE

4

ES/P1

POLE

E/C1

Measure the

individual

resistances of

the ground

system using the

Selective test.

TRANSFORMER

INDUCING CURRENT

EI-162AC

MGB

MGN

13

Page 14

More ground resistance applications

Electrical substations

A substation is a subsidiary station on a trans-

mission and distribution system where voltage

is normally transformed from a high value to

low value. A typical substation will contain line

termination structures, high-voltage switchgear,

one or more power transformers, low-voltage

switchgear, surge protection, controls, and

metering.

Remote switching sites

Remote switching sites are also known as slick

sites, where digital line concentrators and other

telecommunications equipment is operating.

The remote site is typically grounded at either

end of the cabinet and then will have a series of

ground stakes around the cabinet connected by

copper wire.

A typical setup at a cellular tower installation.

Application sites

There are four other particular applications

where you can use the Fluke 1625-2 to measure

the capability of the earth ground system.

Cellular sites/microwave

and radio towers

At most locations there is a 4-legged tower with

each leg individually grounded. These grounds

are then connected with a copper cable. Next to

the tower is the Cell site building, housing all

the transmission equipment. Inside the building

there is a halo ground and a MGB, with the

halo ground connected to the MGB. The cell site

building is grounded at all 4 corners connected

to the MGB via a copper cable and the 4 corners

are also interconnected via copper wire. There is

also a connection between the building ground

ring and the tower ground ring.

Lightning protection at commercial/

industrial sites

Most lightning fault current protection systems

follow the design of having all four corners of

the building grounded and these are usually

connected via a copper cable. Depending on

the size of the building and the resistance value

that it was designed to achieve, the number of

ground rods will vary.

Recommended tests

End users are required to perform the same

three tests at each application: Stakeless

measurement, 3-pole Fall-of-Potential measure-

ment and Selective measurement.

Stakeless measurement

First, perform a Stakeless measurement on:

• The individual legs of the tower and

the four corners of the building

(cell sites/towers)

• All grounding connections

(electrical substations)

• The lines running to the remote site

(remote switching)

• The ground stakes of the building

(lightning protection)

14

Page 15

For all applications, this is not a true ground

resistance measurement because of the network

ground. This is mainly a continuity test to verify

that the site is grounded, that we have an electrical connection, and that the system can pass

current.

3-pole Fall-of-Potential measurement

Second, we measure the resistance of the entire

system via the 3-pole Fall-of-Potential method.

Keep in mind the rules for stake setting. This

measurement should be recorded and measurements should take place at least twice per year.

This measurement is the resistance value for the

entire site.

Selective measurement

Lastly, we measure the individual grounds with

the Selective test. This will verify the integrity of

the individual grounds, their connections, and

determine whether the grounding potential is

fairly uniform throughout. If any of the measurements show a greater degree of variability than

the other ones, the reason for this should be

determined. The resistances should be measured

on:

• Each leg of the tower and all four corners of

the building (cell sites/towers)

• Individual ground rods and their connections

(electrical substations)

• Both ends of the remote site (remote

switching)

• All four corners of the building (lightning

protection)

A typical setup

at an electrical

substation.

Using Stakeless

testing at a remote

switching site.

ER

CURRENT

EI-162X

SENSING

TRANSFORM

T

EN

R

CING CUR

FORMER

U

S

EI-162AC

ND

AN

I

TR

ADVANCED EARTH / GROUND TESTER GEO

1625-2

START

H/C2

TEST

DISPLAY

S/P2

E S H

MENU

AC

DC

Rresistance

Earth/Ground Resistance 300kΩ

Resistance 3kΩ

300kΩ

—

RA

R

R~

4

3

POLE

POLE

2

3

POLE

POLE

2

4

POLE

POLE

4

3

CHANGE

ES/P1

POLE

POLE

ITEM

OFF

E/C1

SELECT

Using Selective

testing on a lightning protection

system.

ER

CURRENT

EI-162X

SENSING

TRANSFORM

START

TEST

DISPLAY

MENU

CHANGE

ITEM

SELECT

ADVANCED EARTH / GROUND TESTER GEO

1625-2

RA

3

POLE

POLE

3

POLE

4

POLE

3

POLE

OFF

H/C2

S/P2

E S HES

AC

Rresistance

DC

300kΩEarth/Ground Resistance 300kΩ

Resistance 3kΩ

—

R

~

R

4

2

POLE

2

POLE

4

ES/P1

POLE

E/C1

15

Page 16

Earth ground products

Fluke 1625-2 Advanced GEO Earth Ground Tester Fluke 1623-2 Basic GEO Earth Ground Tester

The most complete tester

The Fluke 1623-2 and 1625-2 are distinctive earth ground testers that can

perform all four types of earth ground measurement:

• 3-and 4-pole Fall-of-Potential (using stakes)

• 4-pole soil resistivity testing (using stakes)

• Selective testing (using 1 clamp and stakes)

• Stakeless testing (using 2 clamps only)

The complete model kit comes with the Fluke 1623-2 or 1625-2 tester, a set of

two leads, 4 earth ground stakes, 3 cable reels with wire, 2 clamps, batteries

and manual—all inside a rugged Fluke carrying case.

The complete kit

Fluke 1625-2 advanced features

Advanced features of the Fluke 1625-2 include:

• Automatic Frequency Control (AFC)—identifies existing interference and

chooses a measurement frequency to minimize its effect, providing more

accurate earth ground values

• R* Measurement—calculates earth ground impedance with 55 Hz to more

accurately reflect the earth ground resistance that a fault-to-earth ground

would see

• Adjustable Limits —for quicker testing

Optional accessories

320 mm (12.7 in) Split Core Transformer—for performing selective testing on

individual legs of towers.

Comparing earth ground testers

Product Fall of Potential Selective Stakeless 2-Pole method

3-Pole 4-Pole/Soil 1 Clamp 2 Clamp 2 Pole

Fluke 1621

Fluke 1623-2

Fluke 1625-2

Fluke 1630

Product

Fluke 1630 kit

Fluke. The Most Trusted Tools

in the World.

Fluke Corporation

PO Box 9090, Everett, WA 98206 U.S.A.

Fluke Europe B.V.

PO Box 1186, 5602 BD

Eindhoven, The Netherlands

For more information call:

In the U.S.A. (800) 443-5853 or

Fax (425) 446-5116

In Europe/M-East/Africa +31 (0) 40 2675 200 or

Fax +31 (0) 40 2675 222

In Canada (800)-36-FLUKE or

Fax (905) 890-6866

From other countries +1 (425) 446-5500 or

Fax +1 (425) 446-5116

Web access: http://www.fluke.com

©2013-2014 Fluke Corporation.

Specifications subject to change without notice.

Printed in U.S.A. 3/2014 4346628B_EN

Modification of this document is not permitted

without written permission from Fluke Corporation.

Loading...

Loading...