Page 1

BASIC ELECTRONIC COMPONENTS

MODEL ECK-10

Instruction Manual

by Arthur F. Seymour MSEE

It is the intention of this course to teach the fundamental operation of basic

electronic components by comparison to drawings of equivalent mechanical

parts. It must be understood that the mechanical circuits would operate much

slower than their electronic counterparts and one-to-one correlation can never

be achieved. The comparisons will, however, give an insight to each of the

fundamental electronic components used in every electronic product.

Resistors

Capacitors Coils

Semiconductors

Others

Transformers

ELENCO

®

Copyright © 2012, 1994 by Elenco®Electronics, Inc. All rights reserved. Revised 2012 REV-M 753254

No part of this book shall be reproduced by any means; electronic, photocopying, or otherwise without written permission from the publisher.

Page 2

-1-

RESISTORS

RESISTORS,

What do they do?

The electronic component known as the resistor is

best described as electrical friction. Pretend, for a

moment, that electricity travels through hollow pipes

like water. Assume two pipes are filled with water

and one pipe has very rough walls. It would be easy

to say that it is more difficult to push the water

through the rough-walled pipe than through a pipe

with smooth walls. The pipe with rough walls could

be described as having more resistance to

movement than the smooth one.

Pioneers in the field of electronics thought electricity

was some type of invisible fluid that could flow

through certain materials easily, but had difficulty

flowing through other materials. In a way they were

correct since the movement of electrons through a

material cannot be seen by the human eye, even

with the best microscopes made. There is a

similarity between the movement of electrons in

wires and the movement of water in the pipes. For

example, if the pressure on one end of a water pipe

is increased, the amount of water that will pass

through the pipe will also increase. The pressure on

the other end of the pipe will be indirectly related to

the resistance the pipe has to the flow of water. In

other words, the pressure at the other end of the

pipe will decrease if the resistance of the pipe

increases. Figure 1 shows this relationship

graphically.

Electrons flow through materials when a pressure

(called voltage in electronics) is placed on one end

of the material forcing the electrons to “react” with

each other until the ones on the other end of the

material move out. Some materials hold on to their

electrons more than others making it more difficult

for the electrons to move. These materials have a

higher resistance to the flow of electricity (called

current in electronics) than the ones that allow

electrons to move easily. Therefore, early

experimenters called the materials

insulators

if they

had very high resistance to electon flow and

conductors

if they had very little resistance to

electron flow. Later materials that offered a medium

amount of resistance were classified as

semiconductors

.

When a person designs a circuit in electronics, it is

often necessary to limit the amount of electrons or

current that will move through that circuit each

second. This is similar to the way a faucet limits the

amount of water that will enter a glass each second.

It would be very difficult to fill a glass without

breaking it if the faucet had only two states, wide

open or off. By using the proper value of resistance

in an electronic circuit designers can limit the

pressure placed on a device and thus prevent it from

being damaged or destroyed.

SUMMARY: The resistor is an electronic

component that has electrical friction. This friction

opposes the flow of electrons and thus reduces the

voltage (pressure) placed on other electronic

components by restricting the amount of current that

can pass through it.

Figure 1

Low Resistance

Pipe

High Resistance

Pipe (rough walls)

Low Pressure

High Pressure

Through Same

Size Opening

Water Tank

Page 3

-2-

RESISTORS

RESISTORS,

How are they made?

There are many different types of resistors used in

electronics. Each type is made from different

materials. Resistors are also made to handle

different amounts of electrical power. Some

resistors may change their value when voltages are

placed across them. These are called voltage

dependent resistors or

nonlinear

resistors. Most

resistors are designed to change their value when

the temperature of the resistor changes. Some

resistors are also made with a control attached that

allows the user to mechanically change the

resistance. These are called variable resistors or

potentiometers. Figure 2 shows physical shapes of

some different types of resistors.

The first commercial resistors made were formed by

wrapping a resistive wire around a non-conducting

rod (see Figure 3). The rod was usually made of

some form of ceramic that had the desired heat

properties since the wires could become quite hot

during use. End caps with leads attached were then

placed over the ends of the rod making contact to

the resistive wire, usually a nickel chromium alloy.

The value of wirewound resistors remain fairly flat

with increasing temperature, but change greatly with

frequency. It is also difficult to precisely control the

value of the resistor during construction so they

must be measured and sorted after they are built.

By grinding carbon into a fine powder and mixing it

with resin, a material can be made with different

resistive values. Conductive leads are placed on

each end of a cylinder of this material and the unit is

then heated or cured in an oven. The body of the

resistor is then painted with an insulating paint to

prevent it from shorting if touched by another

component. The finished resistors are then

measured and sorted by value (Figure 4). If these

resistors are overloaded by a circuit, their resistance

will permanently decrease. It is important that the

power rating of the carbon composition resistor is

not exceeded.

Figure 2

Carbon Film

Variable

Carbon Composition

THE WIREWOUND RESISTOR

Figure 3

THE CARBON COMPOSITION RESISTOR

Ceramic Rod

Wire

End CapProtective Coating

Figure 4

Insulating Paint Carbon & Resin

Mixture

Conductive Wire

Page 4

-3-

RESISTORS

CARBON FILM RESISTORS

Carbon film resistors are made by depositing a very

thin layer of carbon on a ceramic rod. The resistor

is then protected by a flameproof jacket since this

type of resistor will burn if overloaded sufficiently.

Carbon film resistors produce less electrical noise

than carbon composition and their values are

constant at high frequencies. You can substitute a

carbon film resistor for most carbon composition

resistors if the power ratings are carefully observed.

The construction of carbon film resistors require

temperatures in excess of 1,000

O

C.

Metal oxide resistors are also constructed in a

similar manner as the carbon film resistor with the

exception that the film is made of tin chloride at

temperatures as high as 5,000

O

C. Metal oxide

resistors are covered with epoxy or some similar

plastic coating. These resistors are more costly than

other types and therefore are only used when circuit

constraints make them necessary.

Metal film resistors are also made by depositing a

film of metal (usually nickel alloy) onto a ceramic

rod. These resistors are very stable with

temperature and frequency, but cost more than the

carbon film or carbon composition types. In some

instances, these resistors are cased in a ceramic

tube instead of the usual plastic or epoxy coating.

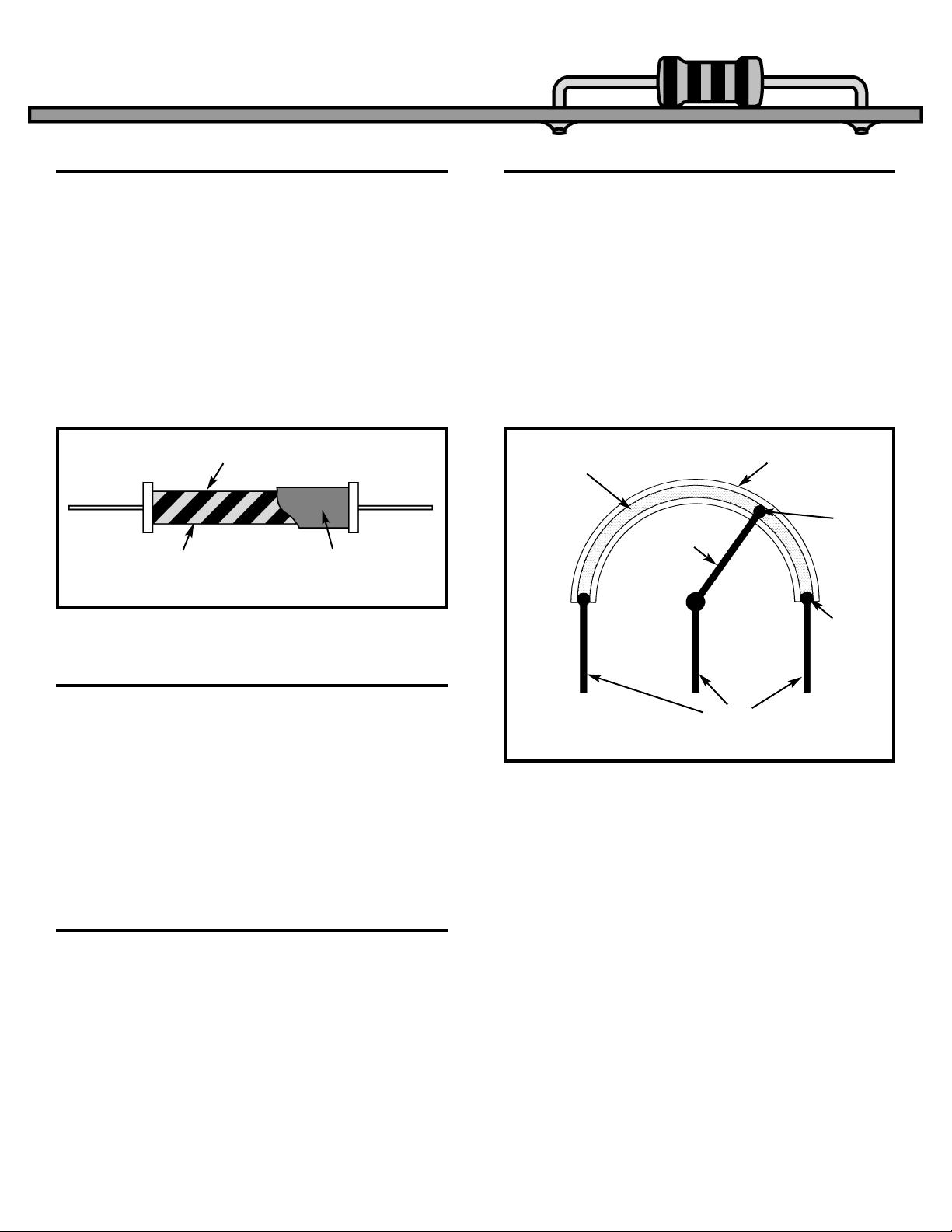

When a resistor is constructed so its value can be

adjusted, it is called a variable resistor. Figure 6

shows the basic elements present in all variable

resistors. First a resistive material is deposited on a

non-conducting base. Next, stationary contacts are

connected to each end of the resistive material.

Finally, a moving contact or wiper is constructed to

move along the resistive material and tap off the

desired resistance. There are many methods for

constructing variable resistors, but they all contain

these three basic principles.

Figure 5

METAL OXIDE RESISTORS

METAL FILM RESISTORS

THE VARIABLE RESISTOR

Figure 6

Carbon Film

Ceramic Rod Flameproof Jacket

Leads

Movable

Arm

Wiper

Contact

Stationary

Contact

Thin Layer

of Resistive

Material

Non-conductive

Base Material

Page 5

-4-

RESISTORS

RESISTOR VALUES AND MARKINGS

The unit of measure for resistance is the ohm, which

is represented by the Greek letter Ω. Before

technology improved the process of manufacturing

resistors, they were first made and then sorted. By

sorting the values into groups that represented a 5%

change in value, (resistor values are 10% apart),

certain preferred values became the standard for

the electronics industry. Table 1 shows the standard

values for 5% resistors.

Resistors are marked by using different colored

rings around their body (see Figure 7). The first ring

represents the first digit of the resistor’s value. The

second ring represents the second digit of the

resistor’s value. The third ring tells you the power of

ten to multiply by. The final and fourth ring

represents the tolerance. For example, gold is for

5% resistors and silver for 10% resistors. This

means the value of the resistor is guaranteed to be

within 5% or 10% of the value marked. The colors

in Table 2 are used to represent the numbers from 0

to 9.

Note: If the third ring is gold, you multiply the first

two digits by 0.1 and if it is silver, by 0.01. This

system can identify values from 0.1Ω to as high as

91 x 10

9

, or 91,000,000,000Ω. The amount of power

each resistor can handle is usually proportional to

the size of the resistor. Figure 8 shows the actual

size and power capacity of normal carbon film

resistors, and the symbols used to represent

resistors on schematics.

10 11 12 13 15 16 18 20

22 24 27 30 33 36 39 43

47 51 56 62 68 75 82 91

Table 1

Figure 7

OrangeRed

Violet Gold

27 X 103= 27,000 Ω,

with 5% Tolerance

COLOR VAL UE

Black 0

Brown 1

Red 2

Orange 3

Yellow 4

Green 5

Blue 6

Violet 7

Gray 8

White 9

Table 2

Figure 8

Regular Variable

Resistor Symbols

1/8 Watt

1/4 Watt

1/2 Watt

Page 6

-5-

RESISTORS

SELF TEST

1. A flow of electrons through a material:

a) Voltage c) Current

b) Resistance d) Conductance

2. The pressure that pushes electrons through a

material:

a) Voltage c) Conduction

b) Current d) Resistance

3. A material that has very high resistance to electron

flow:

a) Conductor c) Resistor

b) Semiconductor d) Insulator

4. A material that allows electrons to flow easily:

a) Conductor c) Resistor

b) Semiconductor d) Insulator

5. A material that produces electrical friction and

restricts the flow of electrons:

a) Conductor c) Resistor

b) Semiconductor d) Insulator

6. A resistor that is made by wrapping a wire around a

ceramic rod:

a) Carbon Film c) Thermistor

b) Carbon Composition d) Wirewound

7. A resistor made by heating powder and resin in an

oven:

a) Carbon Film c) Thermistor

b) Carbon Composition d) Wirewound

8. A resistor made by depositing a very thin layer of

resistive material on a ceramic rod:

a) Carbon Film c) Thermistor

b) Carbon Composition d) Wirewound

9. One of the preferred values for a 5% resistor:

a) 4000Ω c) 77Ω

b) 560Ω d) 395Ω

10. The amount of wattage a resistor can handle is

determined by:

a) Value c) Current

b) Voltage d) Size

THEORY

Circle the letter that best fits the description.

PRACTICE

Open the bag marked “resistors” and fill in the table below.

Color 1 Color 2 Color 3 Color 4 Value Percent Wattage

EXTRA CREDIT

Using a razor blade or sharp knife, scrape away the paint on the body of one resistor and determine the type of

construction used to make it. Try and determine all of the materials used including the metals used to make the

leads.

Page 7

-6-

CAPACITORS,

What do they do?

Capacitors are components that can store electrical

pressure (Voltage) for long periods of time. When a

capacitor has a difference in voltage (Electrical

Pressure) between its two leads it is said to be

charged. A capacitor is charged by forcing a one

way (DC) current to flow through it for a short period

of time. It can be discharged by letting an opposite

direction current flow out of the capacitor. Consider

for a moment the analogy of a water pipe that has a

rubber diaphragm sealing off each side of the pipe

as shown in Figure 9.

If the pipe had a plunger on one end, as shown in

Figure 9, and the plunger was pushed toward the

diaphragm, the water in the pipe would force the

rubber to stretch out until the force of the rubber

pushing back on the water was equal to the force of

the plunger. You could say the pipe is charged and

ready to push the plunger back. In fact, if the

plunger is released it will move back to its original

position. The pipe will then be discharged or with no

charge on the diaphragm.

Capacitors act the same as the pipe in Figure 9.

When a voltage (Electrical Pressure) is placed on

one lead with respect to the other lead, electrons are

forced to “pile up” on one of the capacitor’s plates

until the voltage pushing back is equal to the voltage

applied. The capacitor is then charged to the

voltage. If the two leads of that capacitor are

shorted, it would have the same effect as letting the

plunger in Figure 9 move freely. The capacitor

would rapidly discharge and the voltage across the

two leads would become zero (No Charge).

What would happen if the plunger in Figure 9 was

wiggled in and out many times each second? The

water in the pipe would be pushed by the diaphragm

then sucked back by the diaphragm. Since the

movement of the water (Current) is back and forth

(Alternating) it is called an Alternating Current or

AC. The capacitor will therefore pass an alternating

current with little resistance. When the push on the

plunger was only toward the diaphragm, the water

on the other end of the diaphragm moved just

enough to charge the pipe (transient current). Just

as the pipe blocked a direct push, a capacitor clocks

direct current (DC). An example of alternating

current is the 60 cycle (60 wiggles each second)

current produced when you plug something into a

wall outlet.

SUMMARY: A capacitor stores electrical energy

when charged by a DC source. It can pass

alternating current (AC), but blocks direct current

(DC) except for a very short charging current, called

transient current.

CAPACITORS

Pipe Filled with Water

Rubber Diaphragm

Sealing Center of Pipe

Plunger

Figure 9

Page 8

-7-

CAPACITORS,

How are they made?

There are many different types of capacitors used in

electronics. Each type is made from different

materials and with different methods. Capacitors

are also made to handle different amounts of

electrical pressure or voltage. Each capacitor is

marked to show the maximum voltage that it can

withstand without breaking down. All capacitors

contain the same fundamental parts, which consist

of two or more conductive plates separated by a

nonconductive material. The insulating material

between the plates is called the dielectric. The basic

elements necessary to build a capacitor are shown

in Figure 10.

Perhaps the most common form of capacitor is

constructed by tightly winding two foil metal plates

that are separated by sheets of paper or plastic as

shown in Figure 11. By picking the correct insulating

material the value of capacitance can be increased

greatly, but the maximum working voltage is usually

lowered. For this reason, capacitors are normally

identified by the type of material used as the

insulator or dielectric. Consider the water pipe with

the rubber diaphragm in the center of the pipe. The

diaphragm is equivalent to the dielectric in a

capacitor. If the rubber is made very soft, it will

stretch out and hold a large amount of water, but it

will break easily (large capacitance, but low working

voltage). If the rubber is made very stiff, it will not

stretch far, but will be able to withstand higher

pressure (low capacitance, but high working

voltage). By making the pipe larger and keeping the

stiff rubber we can achieve a device that holds a

large amount of water and withstands a high amount

of pressure (high capacitance, high working voltage,

large size). These three types of water pipes are

illustrated in Figure 12. The pipes follow the rule that

the capacity to hold water, (Capacitance) multiplied

by the amount of pressure they can take (Voltage)

determines the size of the pipe. In electronics the

CV product determines the capacitor size.

CAPACITORS

THE METAL FOIL CAPACITOR

Soft Rubber

Figure 12

Stiff Rubber

Stiff Rubber

Larger Size

Large Capacity

Low Pressure

Low Capacity

but can withstand

High Pressure

High Capacity and can withstand High Pressure

Figure 10

Lead 1

Nonconductive Material

Conductive Plate

Lead 2

Figure 11

Lead 1

Paper or Plastic Insulator

Conductive Foil

Lead 2

Page 9

-8-

DIELECTRIC CONSTANT,

What is it?

The dielectric (rubber diaphragm in the water pipe

analogy) in a capacitor is the material that can

withstand electrical pressure (Voltage) without

appreciable conduction (Current). When a voltage is

applied to a capacitor, energy in the form of an

electric charge is held by the dielectric. In the

rubber diaphragm analogy the rubber would stretch

out and hold the water back. The energy was stored

in the rubber. When the plunger is released the

rubber would release this energy and push the

plunger back toward its original position. If there

was no energy lost in the rubber diaphragm, all the

energy would be recovered and the plunger would

return to its original position. The only perfect

dielectric for a capacitor in which no conduction

occurs and from which all the stored energy may be

recovered is a perfect vacuum. The

DIELECTRIC

CONSTANT

(K) is the ratio by which the

capacitance is increased when another dielectric

replaces a vacuum between two plates. Table 3

shows the Dielectric Constant of various materials.

To make a variable capacitor, one set of stationary

aluminum plates are mounted to a frame with a

small space between each plate. Another set of

plates are mounted to a movable shaft and designed

to fit into the space of the fixed plates without

touching them. The insulator or dielectric in this type

of variable capacitor is air. When the movable plates

are completely inside the fixed plates, the device is

at minimum capacitance. The shape of the plates

can be designed to achieve the proper amount of

capacitance versus rotation for different

applications. An additional screw is added to

squeeze two insulated metal plates together

(Trimmer) and thus set the minimum amount of

capacitance.

CAPACITORS

Air, at normal pressure 1 Mica 7.5

Alcohol, ethyl (grain) 25 Paper, manila 1.5

Beeswax 1.86 Paraffin wax 2.25

Castor Oil 4.67 Porcelain 4.4

Glass flint density 4.5 10 Quartz 2

Glycerine 56 Water, distilled 81

Table 3

THE VARIABLE CAPACITOR

Figure 13

Fram e

Movable

Plates

Shaft

Fixed Plates

Trimmer

Page 10

The amount of charge a capacitor can hold

(capacitance) is measured in Farads. In practice,

one farad is a very large amount of capacitance,

making the most common term used micro-farad or

one millionth of a farad. There are three factors that

determine the capacitance that exist between two

conductive plates:

1. The bigger the plates are (Surface Area),

the higher the capacitance. Capacitance

(C) is directly proportional to Area (A).

2. The larger the distance is between the two

plates, the smaller the amount of

capacitance. Capacitance (C) is indirectly

proportional to distance (d).

3. The larger the value of the dielectric

constant, the more capacitance (Dielectric

constant is equivalent to softness of the

rubber in our pipe analogy). The

capacitance (C) is directly proportional to

the Dielectric Constant (K) of the insulating

material. From the above factors, the

formula for capacitance in Farads becomes:

C = 0.244K Picofarads *

C = Capacitance in Picofarads (Farad x 10

-12

)

K = Dielectric Constant

A = Area of one Plate in square inches

N = Number of Plates

d = Distance between plates in inches

Example Calculation for Capacitor shown in Figure 14.

C = 2.24 x (1 x 1)(2 - 1) / (.01) = 224 Picofarads or

0.000224 Microfarads.

* If A and d are in centimeters change 0.224 to

0.0885.

The older styles of capacitors were marked with

colored dots or rings similar to resistors. In recent

years, the advances in technology has made it

easier to print the value, working voltage, tolerance,

and temperature characteristics on the body of the

capacitors. Certain capacitors use a dielectric that

requires markings to insure one lead is always kept

at a higher voltage than the other lead. Figure 15

shows typical markings found on different types of

capacitors. Table 4 gives the standard values used

and the different methods for marking these values.

-9-

CAPACITANCE,

How is it calculated?

CAPACITORS

A(N-1)

d

Figure 14

0.01 inch

Glass K=10

1 inch

1 inch

CAPACITOR VALUES AND MARKINGS

Figure 15

B

682K

K

+10

+16V

2200μF 25V

10μF 25V

Radial

Electrolytic

Axial

Electrolytic

Disc

Tantalum

Electrolytic

Chip

(no

markings)

Page 11

-10-

CAPACITORS

Voltage

1

Code

2

Cap. Value3Typical Markings

4 5

Tolerance (%)

6

Markings

7

4 0G 100pF 100pF 101 +5% J

5.5 0L .001μF .001 102 +10% K

6.3 0J .015μF .015 152 +20% M

10 1A .002μF .002 202 –10% +30% Q

16 1C .0022μF .0022 222 –10% +50% T

25 1E .003μF .003 302 –20% +80% Z

35 1V .033μF .033 333 SPECIAL A

50 1H .047μF .047 473

63 1J .05μF .05 R05 Temperature

Markings

80 1K .068μF .068 R068

100 2A .1μF .1 104 NP0 {<10ppm / OC}

110 2Q .15μF .15 154 N100 {<100ppm / OC}

125 2B .2μF .2 204 N220 {<220ppm / OC}

160 2C 2.2μF 2.2 2R2 N820 {<820ppm / OC}

180 2Z 22μF 22 22 Y5F

200 2D 100μF 100 100 Y5T

220 2P 220μF 220 220 Y5V

250 2E 470μF 470 470 X5F

315 2F 1000μF 1000 1000 Z5U

Capacitor markings vary greatly from one

manufacturer to another as the above table shows.

Voltages may be marked directly (200V) or coded

(2D). The value of capacitance may be marked

directly on the part as shown in columns 4 and 5

(note that .001μF and 1000μF have the same

marking, but the difference in size makes the value

obvious). The number 102 may also be used to

represent 1000 (10+2 zeros). In some instances the

manufacturer may use an R to represent the

decimal point. The tolerance is usually printed

directly on the capacitors. When it is omitted, the

standard tolerance is assumed to be +80% to –20%

for electrolytics. Capacitance change with

temperature is coded in parts per million per degree

C, {N220 = 220/1,000,000 or .022%}, or by a

temperature graph. See manufacturers

specifications for complete details.

CAPACITOR SYMBOLS

Figure 16 shows the schematic symbols used to represent

capacitors. The + symbol indicates that the capacitor is

polarized and the lead marked with the + sign must always

have a

higher

voltage than the other lead. The curved

plate, plate with sides, and minus sign also indicate the

capacitor is polarized and these leads must always be at a

lower

voltage than the other lead. The arrow crossing

through the capacitor indicates of capacitance is variable.

Figure 16

+

–

Standard VariablePolarized

Page 12

-11-

CAPACITORS

SELF TEST

1. A flow of electrons in one direction:

a) AC Voltage c) Alternating Current

b) Direct Voltage d) Direct Current

2. When two conductive plates are moved closer

together Capacitance will:

a) Increase c) Stay the Same

b) Decrease d) Vary Downwards

3. The name given to the material between a capacitor’s

plates:

a) Air c) Conductor

b) Dielectric d) Insulator

4. Electrons flowing in and out of a wire:

a) AC Voltage c) Alternating Current

b) Direct Voltage d) Direct Current

5. If the size of the conductive plates is increased,

capacitance will:

a) Increase c) Stay the Same

b) Decrease d) Vary Downwards

6. A capacitor will block:

a) AC Voltage c) Alternating Current

b) Direct Voltage d) Direct Current

7. When electrons are forced onto one plate of a

capacitor:

a) Polarization c) Storage

b) Discharging a) Charging

8.

A capacitor lead that is marked with a + must always be:

a) Grounded c) At higher voltage than

the other lead

b) At highest voltage d) b & c

9. A small disc capacitor marked 100 has a value of:

a) 100μF c) 100pF

b) .00001F d) 100F

10. A large electrolytic capacitor marked 100 has a value

of:

a) 100μF c) 100pF

b) .00001F d) 100F

11. If a dielectric is changed from air to distilled water the

capacitance will:

a) remain the same c) decrease

b) increase 81 times d) drop in half

12. A dielectric that stores energy with no loss:

a) Does not exist c) Pure Glass

b) Air d) A perfect vacuum

THEORY

Circle the letter that best fits the description.

PRACTICE

Open the bag marked “capacitors” and fill in the table below.

EXTRA CREDIT

What happens to the total capacitance if you connect two

capacitors as shown in Figure 17. Hint, use water pipe

analogy and try to calculate equivalent if one water pipe.

Type Capacitance

Value

Working

Voltage

Polarized

(Y/N)

Other

Markings

Figure 17

10μF

20μF

? μF

Table 4

Page 13

-12-

INDUCTORS

INDUCTORS,

What do they do?

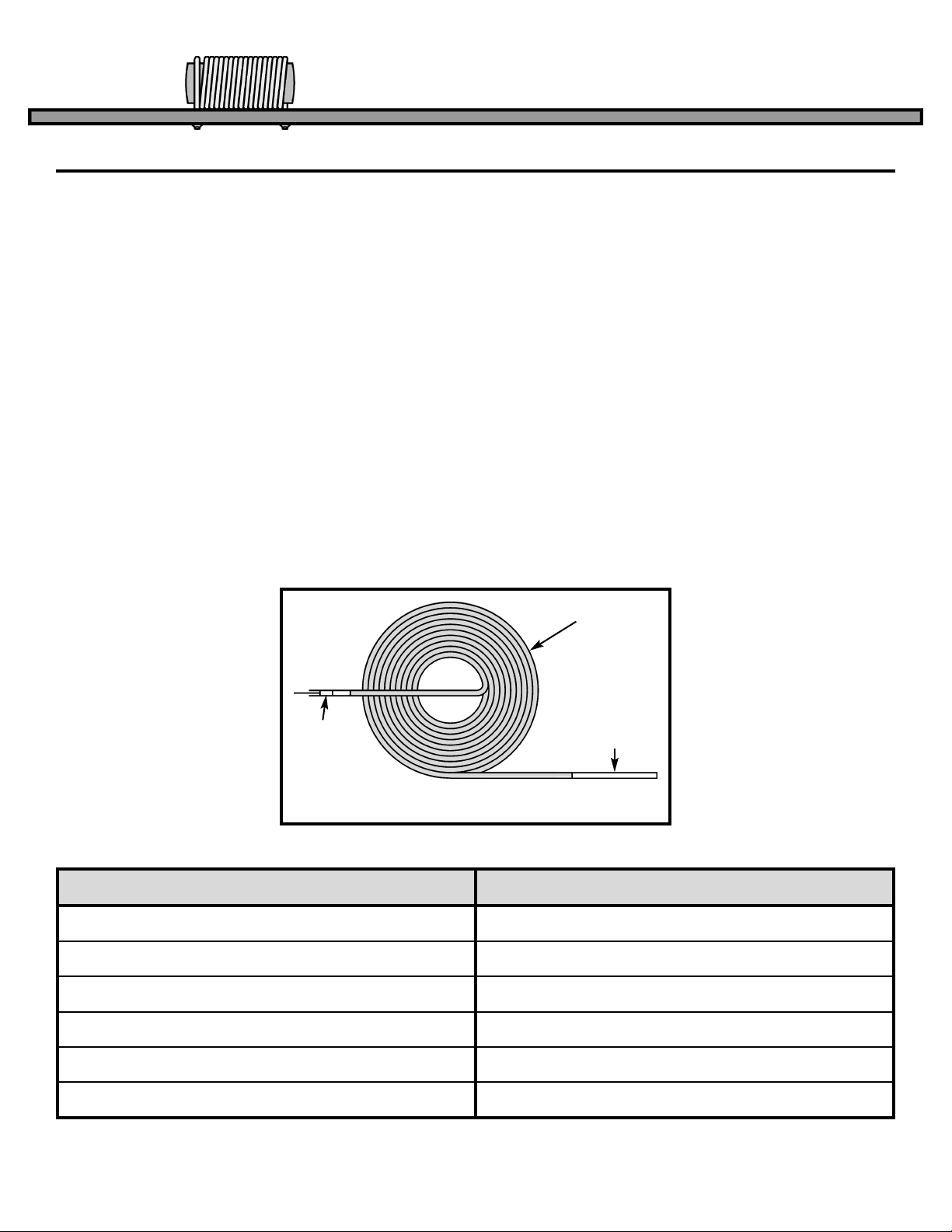

The electronic component known as the inductor is

best described as electrical momentum. In our

water pipe analogy the inductor would be equivalent

to a very long hose that is wrapped around itself

many times (see Figure 18). If the hose is very long

it will contain many gallons of water. When pressure

is applied to one end of the hose, the thousands of

gallons of water would not start to move instantly. It

would take time to get the water moving due to

inertia (a body at rest wants to stay at rest). After a

while the water would start to move and pick up

speed. The speed would increase until the friction of

the hose applied to the amount of pressure being

applied to the water. If you try to instantly stop the

water from moving by holding the plunger, the

momentum (a body in motion wants to stay in

motion) of the water would cause a large negative

pressure (Suction) that would pull the plunger from

your hands.

Since Inductors are made by coiling a wire, they are

often called Coils. In practice the names Inductor

and Coil are used interchangeably. From the above

analogy, it is obvious that a coiled hose will pass

Direct Current (DC), since the water flow increases

to equal the resistance in the coiled hose after an

elapsed period of time. If the pressure on the

plunger is alternated (pushed, then pulled) fast

enough, the water in the coil will never start moving

and the Alternating Current (AC) will be blocked.

The nature of a Coil in electronics follows the same

principles as the coiled hose analogy. A coil of wire

will pass DC and block AC. Recall that the nature of

a Capacitor blocked DC and passed AC, the exact

opposite of a coil. Because of this, the Capacitor

and Inductor are often called Dual Components.

Table 5 compares the properties of capacitors and

inductors.

Plunger

Water Pipe

Large Hose Filled

with Water

Figure 18

Capacitor Inductor

Blocks Direct Current Blocks Alternating Current

Passes Alternating Current Passes Direct Current

Voltage in Capacitor cannot change instantly Current in an Inductor cannot change instantly

Quick Voltage change produces large Current Quick Current change produces large Voltage

Stores Energy in Electric Field Stores Energy in Magnetic Field

Current leads Voltage Voltage leads Current

Table 5

Page 14

-13-

INDUCTORS,

How are they made?

In order to understand how inductors are made, we

have to change our water pipe analogy slightly to

include the effect of magnetic fields. Consider two

pipes filled with water and small magnets attached

to the walls of the pipes with rubber bands as shown

in Figure 19. The moving magnets, due to the

original current, pull the magnets in the second pipe

and force a small current to flow in the same

direction as the original current. When the rubber

bands are fully stretched, the induced current will

stop, even though the initial DC current is still

flowing. If the original current is an AC current

however, it will induce a continuous AC current in the

second pipe because the magnets will move back

and forth, pulling the magnets in the second pipe

back and forth.

Consider the two coiled pipes shown in Figure 20.

When the pipe is stretched out (increased length) as

in coil 1, the adjacent turns have little affect on each

other. In coil 2 (decreased length) the magnets in

each turn of the pipe are linking and the amount of

“apparent mass” in the pipe seems to increase. In

an inductor, pushing the coiled wire closer together

causes the inductance of the coil to also increase,

and stretching the coil out will lower the inductance

of the coil. In other words, the inductance of a coil

is indirectly proportional to its length. If the diameter

of the coil is increased, it will take more hose to form

a loop, and the amount of water will therefore

increase. More water means a larger “apparent

mass”. Inductance will also increase in a coil if the

cross sectional area increases. Inductance is

directly proportional to area.

Consider the affect of adding more turns to coiled

pipe. The amount of material to push (mass) is

increased and the amount of linkage is increased

due to more magnets available. This causes the

“apparent mass” to increase at a greater rate than

would be expected. When making an inductor, the

actual inductance is directly proportional to the

square of the number of turns.

The final factor to consider when making a coil is the

core material at the center of the coil. If our pipe

wrapped around a material that contained many

magnets, they would also link to the magnets in the

pipe. This would increase the “apparent mass” of

the water in the pipe.

The tiny magnets in

the core would rotate

as shown in Figure 21

and force the water to

keep moving in the

same direction.

Placing an iron core at

the center of an

inductor will directly

increase the

inductance by an

amount equal to the

permeability of the

core material.

INDUCTORS

Figure 20

Figure 21

Coil 1

Coil 2

Many tiny

magnets

IN

OUT

Figure 19

Induced

Current

Initial

Current

Page 15

-14-

INDUCTORS

INDUCTANCE,

How is it calculated?

Reviewing how coils are made will show the

following:

1. Inductance of a coil is indirectly proportional to

the length of the coil.

2. Inductance is directly proportional to the cross

sectional area.

3. Inductance is proportional to the square of the

number of turns.

4. Inductance is directly proportional to the

permeability of the core material.

From the above information the formula for

inductance of a simple iron core would be:

L =

Where:

L = Inductance in microhenrys

N = Number of turns

μ = Permeability of core material

A = Cross-sectional area of coil, in square inches

l = Length of coil in inches

This formula is good only for solid core coils with

length greater than diameter.

N

2

μA

10l

TRANSFORMERS,

How are they made?

Placing different coils on the same iron core as

shown in Figure 22 produces the electronic

component known as the Transformer. If a DC

current is forced through the center coil, the other

two coils will only produce a current when the

original current is changing. Once the DC current

reaches a constant value, the other two coils will

“unlink” and produce no flowing current if loaded. If

the generator voltage is continuously changing as in

Figure 22, it will produce a current that changes with

time. This changing current in the center coil will

produce similar currents in both of the end coils.

Since the bottom coil has twice the number of turns

(twice the magnetic linkage), the voltage across this

coil will be twice the generator voltage. The power

in an electronic device is equal to the voltage across

the device times the current through the device

(P=VI). If the voltage doubles on the bottom

winding, then the current must become 1/2 due to

the law of conservation of power (Power cannot be

created or destroyed, but can be transformed from

one state to another). Since the bottom coil is

wound in the same direction as the generator coil,

the voltage across the coil (top wire to bottom wire)

will be the same polarity as the generator voltage.

The top coil is wound in the opposite direction

forcing the core magnet rotation (Called flux by the

Pros) to push the current in the opposite direction

and produce a voltage of the opposite polarity.

Since the number of turns in the top coil are the

same as the generator coil, the voltage and current

(Power that can be taken from the coil) will also be

equal. This ability to transform AC voltages and AC

currents influenced early experimenters to call this

device a Transformer.

Figure 22

Voltage

Generator

Iron Core –V

Opposite

Voltage

i

i

½i

2V

2N Turns

N Turns

Direction of

Core Magnet

Rotation Due

to Current i

Page 16

-15-

TWO MORE LAWS ABOUT INDUCTORS

Faraday’s Law states that any time a conductor

moves through a magnetic field (Figure 23) a

voltage is generated. Because of this principle, it is

possible to attach a magnet (or coil) to a rotating

device and produce large amounts of electrical

power (the Hoover Dam for example).

Lenz’ Law states that the induced currents in a

conductor passing through a magnetic field will

produce a magnetic field that will oppose the motion

between the magnet and the conductor. To produce

a large amount of electrical power, a large

mechanical force is required (conservation of

power).

Most inductors are custom made to meet the

requirements of the purchaser. They are marked to

match the specification of the buyer and therefore

carry no standard markings. The schematic

symbols for coils and transformers are shown in

Figure 24. These symbols are the most commonly

used to represent fixed coils, variable coils, and

transformers.

The Q (figure of merit) of a coil is the ratio of the

inductive reactance to the internal series resistance

of the coil. Since the reactance and resistance can

both change with frequency, Q must be measured at

the desired frequency. Anything that will raise the

inductance without raising the series resistance will

increase the Q of the coil; for example, using an iron

core. Lowering the series resistance without

lowering the inductance will also raise the Q, more

turns of larger wire for example. Q is important

when the inductor is used in a resonant circuit to

block or select desired frequencies. The higher the

Q, the tighter the selection of frequencies become.

The Inductor prevents current from making any

sudden changes by producing large opposing

voltages. Magnetic coupling can be used to

transform voltages and currents, but power must

remain the same. Coils and transformers can be

used to select frequencies.

INDUCTORS

Figure 23

Wire

Lines of Flux

Motion of

Magnet

S

N

INDUCTANCE SYMBOLS AND MARKINGS

THE Q FACTOR IN COILS

SUMMARY

Figure 24

Fixed Coils Variable Coils

Iron Core

Transformer

Tunable Transformer

X

L

r

Page 17

-16-

SELF TEST

1. The inductor is best described as:

a) Induced Voltage c)

Electrical Storage Device

b) Long Wire d) Electrical Momentum

2. When wires in a coil are moved closer together, the

inductance will:

a) Increase c) Stay the Same

b) Decrease

3. Another word used to represent an inductor:

a) Wire c) Transformer

b) Coil d) Conductor

4. If the diameter of a coil is increased, the inductance

will:

a) Increase c) Stay the Same

b) Decrease

5. If the number of turns in a coil is decreased, the

inductance of that coil will:

a) Increase c) Stay the Same

b) Decrease

6. An inductor will block:

a) Alternating Voltage c) Alternating Current

b) Direct Voltage d) Direct Current

7. When an iron core is placed into the center of a coil,

the inductance will:

a) Increase c) Stay the Same

b) Decrease

8. If voltage in a transformer is stepped down, the current

will:

a) Increase c) Must Stay the Same

b) Decrease

9. When a conductor is moved through a magnetic field:

a) Power is created c) Magnetic field is

reduced

b) A voltage is d) a & c

generated on the wire.

10. The Q factor of a coil is equal to:

a) Wire quality c) Ratio of inductance

b) Ratio of reactance to resistance

to resistance

11. If windings on a straight rod are in the same direction,

the induced voltage will have:

a) Same amplitude c) Same polarity

b) Different amplitude d) Different polarity

12. An inductor stores energy in its:

a) Electric field c) Core

b) Magnetic field d) Wires

THEORY

Circle the letter that best fits the description.

PRACTICE

Using the coil supplied, answer the following questions.

EXTRA CREDIT

What happens to the total inductance if you connect two

coils as shown in Figure 25. Hint, remember the coiled

hose analogy and try to calculate equivalent if one coiled

hose.

Figure 25

10μH

? μH

INDUCTORS

(Hold the leads and peel the tape off).

Is the coil wound on an iron form? Yes ____ No ____

What prevents the wire from shorting? ________________________________________

How many turns are on the coil? _____________________

Example: Using a length of 0.1”, a radius of 0.02”, permeability of 14 for the iron core, and 56 turns, calculate

the inductance of the coil and record here: ________________________

20μH

Page 18

-17-

SEMICONDUCTORS

THE DIODE,

what is it?

The diode can be compared to the check valve

shown in Figure 26. The basic function of a check

valve is to allow water to flow in only one direction.

Once the force of the spring is exceeded, the plate

moves away from the stop allowing water to pass

through the pipe. A flow of water in the opposite

direction is blocked by the solid stop and plate. If it

took a pressure of 0.7lb to exceed the spring force,

the flow of water versus pressure might look like

Figure 27. In electronics, this curve would represent

the typical silicon diode if pounds per square inch

equaled volts and gallons per minute equaled

amperes. Of course, the amount of current that

flows through the diode must be limited or the device

could be damaged. Just as too much water through

the check valve could destroy the plate (shorted

diode). If the diode is made of Gallium Arsenide, it

would take approximately twice the voltage to

produce a flow of current (spring in Figure 26 is

twice as strong). The energy level required to “turn

on” a Gallium Arsenide diode is so high, that light is

generated when current starts to flow. These diodes

are called “Light Emitting Diodes”, or simply LED’s.

The transistor is best described as a device that

uses a small amount of current to control a large

amount of current (Current Amplifier). Consider a

device fabricated as shown in Figure 28. A small

amount of “Base Current” pushes on the L

1

portion

of the lever arm forcing check valve D

1

to open, even

though it is “reverse biased” (pressure is in direction

to keep check valve shut). Keep in mind the base

current would not start to flow until the check valve

D

2

allowed current to flow (0.7lb). If the current ratio

through D

1

and Base was equal to the lever arm

advantage, then I1/ Ib= L1/ L2. Call this ratio Beta

(β) and let L1= 1 inch and L2= 0.01 inch. Then β =

100 and I

1

will be 100 times Ib. Since both currents

must pass through D

2

, I2= I1+ Ib. These same

principles apply to a silicon NPN transistor. I

1

becomes collector current (IC), and I2would be

emitter current (I

E

). β = IC/ IBand IE= IB+ IC.

THE TRANSISTOR,

what is it?

Spring

Solid Stop

Movable Plate

Water-tight Pivot

Figure 26

Figure 27

0.7

Pressure (lbs per square inch)

Current (gals. per min.)

Figure 28

Base Current

I

b

L

1

L

2

I

1

D1

D2

I

2

Lever

Arm

NPN Transistor

Pivot

Page 19

-18-

SEMICONDUCTORS

THE PNP TRANSISTOR

Figure 29 represents the water pipe equivalent of a

PNP transistor. The emitter releases current that

splits into two paths. The base current “forces open”

the collector check valve which collects all the

current except the small amount that goes into the

base. The direction of current in the PNP transistor

is opposite that of the NPN transistor. Because of

these differences, the emitter of the PNP is usually

referenced to the power supply voltage and the

emitter of the NPN is usually referenced to ground

or zero voltage. In both transistors, the current

amplification factor (I

c/Ib

) is called Beta (β).

In Figure 30 the center of a small section of a pipe

is made of thin, flexible rubber and that rubber is

surrounded by water from a third pipe called the

gate. When pressure is applied to the gate, the

rubber pinches off the current from the source to the

drain. No current flows from gate to drain or source.

This device uses a change in gate pressure to

control the current flowing from source to drain.

Since there are no check valves, the current can

flow in either direction. In other words, this device

acts like a variable resistor. The Field Effect

Transistor (FET) also controls current between

source and drain by “pinching off” the path between

them. The level of voltage on the gate controls the

amount of current that will flow. Since no DC current

flows in or out of the gate (only momentarily a small

amount will flow to adjust to new pressures as in a

capacitor), the power used by the gate is very close

to zero. Remember, power equals voltage times

current, and if the current is zero, the power is zero.

This is why FET’s are used in the probes of test

equipment. They will not disturb the circuit being

tested by removing power during a measurement.

When a second gate section is added (pipe and

rubber) between the source and drain it is called a

Dual Gate FET. In our water pipe analogy of the

FET transistor, the rubber must be very thin and

flexible in order to “pinch off” the current from the

source to the drain. This means it could be easily

damaged by a small “spike” of high pressure. The

same is true of an electronic FET. A high voltage

“spike” (Static Electricity) can destroy the gate and

ruin the FET. To protect the FET, they are

sometimes packaged with metal rings shorting their

leads, and a fourth lead may be added to the metal

case containing the transistor.

Figure 29

Base

I

B

IE= IB+ I

C

PNP Transistor

THE FIELD EFFECT TRANSISTOR

Figure 30

Collector

Emitter

I

E

I

C

Drain

Source

Gate

FET Transistor

Page 20

-19-

SEMICONDUCTORS

THE INTEGRATED CIRCUIT

If the water pipe analogies of the resistor, diode,

transistor, and very small capacitors could be

etched into a single block of steel you would have

the equivalent of the Integrated Circuit in

Electronics. Figure 31 represents such a device.

This block of steel would have to be very large to

include all the mechanical parts needed. In

electronics, the actual size of a diode or transistor is

extremely small. In fact, millions can be fabricated

on a piece of silicon no larger than the head of a pin.

Photographic reduction techniques are used to

generate the masking needed to isolate each part.

These masks are then stepped and repeated in

order to make many separate integrated circuits at

the same time on a single substrate. Using mass

production techniques, these circuits are

manufactured, packaged, and sold at prices much

lower than the equivalent discreet circuit would cost.

SEMICONDUCTOR SYMBOLS

Figure 32 shows the common symbols used

in electronics to represent the basic

components. Integrated Circuits are usually

drawn as blocks with leads or as a triangle

for operational amplifiers. The Zener diode

(voltage reference diode) is used in the

reverse direction at the point of breakdown.

Figure 32

Diode LED

Zener

Diode

PNP NPN FET

Figure 31

The Integrated Circuit

8

7

14

1

Page 21

-20-

SEMICONDUCTORS

SELF TEST

1. The diode is best described as:

a) Switch c)

Electrical Storage Device

b) Check Valve d) Electrical Momentum

2. A silicon diode begins to conduct current at

approximately:

a) 7 volts c) 0.7 lb.

b) 0.7 volts d) 7 lbs.

3. NPN transistors have:

a) 2 leads c) 2 diodes

b) 3 leads d) b & c

4. NPN and PNP transistors are used to:

a) Create Power c) Control Current

b) Change Resistance d) Control Capacitance

5. The ratio of collector current to base current in a

transistor is called:

a) Beta (β) c) Current Control

b) Amplification d) FET

6. A diode made of Gallium Arsenide is called:

a) Zener Diode c) LED

b) Power Diode d) Detector Diode

7. A Field Effect Transistor controls Source to Drain

current by:

a) Diode Conduction c) Base Voltage

b) Base Current d) Gate Diode

8. A Zener Diode is used as:

a) Voltage Reference c) Resistance Control

b) Current Reference d) b & c

9. An Integrated Circuit contains:

a) Diodes and Resistors c) Inductors

b) Transistors and Small d) a & b

Capacitors

10. If the arrow in the symbol for a transistor points

toward the base lead, the transistor is a:

a) NPN Transistor c) FET Transistor

b) PNP Transistor

THEORY

Circle the letter that best fits the description.

PRACTICE

Open the Semiconductor bag and answer the following questions.

EXTRA CREDIT

Connect the LED (light emitting diode) to a 9 volt battery

(not provided) as shown in Figure 33. Why is the resistor

necessary? If the LED does not light up reverse the

battery leads. Why does the LED only light when

connected a certain way?

Figure 33

How many of the devices are diodes? __________

How many of the devices look like transistors? __________

How many integrated circuits are included? __________

Was a Light Emitting Diode included? __________

How are the diodes marked to show which end current will not go into? __________

Twisted

Leads

LED

1000Ω

Resistor

9V

Battery

Page 22

-21-

MECHANICAL PARTS

PRINTED CIRCUIT BOARDS,

What are they?

A printed circuit is a conductive pattern glued to one

or both sides of an insulating material. Holes are

punched or drilled through the conductor and board

to allow the interconnection of electronic parts. In

the case of a double sided board, the holes are

plated to provide a connection between the

conductors on both sides of the board. This method

provides considerable space savings over hand

wiring and allows for automated insertion and

soldering of parts. A more uniform product is

produced because wiring errors are eliminated. The

insulating material thickness may vary from 0.015”

to 0.500”. The most widely used base material is

NEMA-XXXP paper base phenolic. Copper is the

most common conductive material glued to the

base. The common thicknesses of the copper foil

are 0.0014” (1 oz./sq. ft.) and 0.0028” (2 oz./sq. ft.).

For single sided boards, the copper is laminated to

the board and then screened and etched away.

Double sided boards use a plating process and

conductive ink to achieve the desired layout.

Figure 34

Insulating

Material

Wrong

Copper

Correct

DESIGN RULES

After a the breadboard has been tested, there are

some design rules used to layout the printed circuit

board. A few of these basic rules are listed here:

1. Diameter of punched holes should not be less

than 2/3 the board thickness.

2. Distance between punched holes or between

holes and board edge should not be less than the

board thickness.

3. Holes should not exceed more than 0.020” of the

diameter of the wire to be inserted in the hole

(machine insertion may require more, but leads

should be “clinched”).

4. Conductor widths should be large enough to

carry current peaks. A width of one tenth of an

inch (1 oz./sq. ft. copper) will increase in

temperature 10

O

C at a DC current of 5A.

5. Conductor spacing must be capable of

withstanding applied voltages. If a voltage

difference of 500 volts exists between two copper

runs, they must be separated by at leads 0.03” to

prevent breakdown.

6. Avoid the use of sharp corners when laying out

copper (see Figure 34). Sharp corners produce

high electric fields that can lower breakdown.

Sharp corners will also make it easier for copper

to peel from the board.

7. Heavy parts must be mounted to prevent board

damage if the unit is dropped.

8. The printed circuit board must be fastened to

prevent leads from touching the case or any other

object mounted near the board.

9. Mounting hardware must be designed to prevent

board stress (warping or excessive torque).

Page 23

-22-

MECHANICAL PARTS

THE TOP LEGEND

The component side of a printed circuit board

should always have a drawing showing the

placement of the parts and their schematic marking

(R1, R2, etc.). This drawing is called the

To p

Legend

. When a board needs to be repaired, the

schematic becomes the “road map” and the top

legend becomes the “address” on the part. Figure

35 shows the correlation between the Schematic

and the Top Legend.

Different parts have been discussed. A printed

circuit board to interconnect these parts has been

discussed. Now it’s time to talk about the “Electronic

Glue” called Solder. Soldering wire is composed of

Tin and Copper with a rosin or acid core. Acid core

solder should never be used on electronic boards

since the acid will damage the components. Acid

core solder is mainly used to attach metals (copper

water pipes for example). When tin and copper are

mixed, the melting point of the mixture is lower than

the melting point of either tin or copper. The point at

which the melting point is the lowest is when the

mixture equals 99.3% tin and 0.7% copper. This is

called the eutectic (u tek’tik) point of the mixture.

The most common flux placed at the center of this

hollow wire alloy is Rosin based. Removing the flux

from the board requires a chemical that can dissolve

rosin. In recent years many water soluble fluxes

have been developed. These fluxes can be removed

by washing the boards in water.

After the parts are placed in the holes on the printed

circuit board, their leads should be trimmed and

bent. A good mechanical connection will improve

the soldering capability of the parts by forcing the

part and copper on the board to rise to the same

temperature. Positioning the soldering iron correctly

and using the right amount of heat are crucial to a

good solder job. Solder practicing is highly

recommended (Elenco

®

Solder Practice Kit Model

SP-1A).

SOLDER,

The Electronic Glue

Figure 35

Schematic

Printed Circuit Board

R1

C1

R2

B+

T1

D1

C2

Q1

R1

C1

R2

T1

D1

C2

Q1

Page 24

There are many other mechanical parts used by

manufacturers of electronic equipment. Most of

them fall into the category of switching or connecting

circuits. In Figure 36, five of the six parts shown are

used to switch or connect signals to the printed

circuit board. Only the spacer falls into a different

category, called mounting. The switch is used to

redirect current or voltage from one circuit to

another. The wire nut is used to hold two twisted

wires together and insulate them (prevent them from

being bare and exposed) at the same time. The PC

board male and female connectors are used to

attach wires from controls or other circuits to the

printed circuit board. The Earphone Jack is used to

bring a signal from the printed circuit board to an

earphone. The spacer holds the printed circuit

board away from the case to prevent leads from

shorting to the case.

There are many different methods for mounting

printed circuit boards. The simplest method is using

machine screws and spacers. Figure 37 shows

some of the common screw heads used by

electronic manufacturers. The oval head screw in

Figure 37 has a tapered end that will cut into the

metal and make a thread for the body of the screw.

The self-threading screw eliminates the need for a

nut and lockwasher but can produce metal

fragments that must be removed to prevent shorts

from occurring.

-23-

MECHANICAL PARTS

OTHER MECHANICAL PARTS

MOUNTING HARDWARE

Figure 37

Round Head

Pan Head

Fillister Head

Flat Head

Oval Head Self-threading

Figure 36

Switch

Wire Nut

Female Connector

Earphone Jack Female

Spacer

PC Board Male

Connector

Page 25

-24-

MECHANICAL PARTS

SELF TEST

1. Copper patterns on a Printed Circuit Board should

always be:

a) As thin as possible c) Rounded

b) Sharp and square d) On one side only

2. The distance between conductors on a printed circuit

should be large enough to:

a) Etch easily c) Clean

b) Solder across d) Prevent voltage

breakdown

3. The top legend shows:

a) Copper path c) Schematic

b) Part placement d) Hole numbers

4. The schematic shows:

a) Part placement c) Hole sizes

b) Copper path d)

Electrical connections

5. The material the copper is glued to on a printed circuit

board is called a:

a) Conductor c) Resistor

b) Semiconductor d) Insulator

6. Solder with the lowest melting point has a ratio of tin

to lead of:

a) 63/37 c) 40/60

b) 60/40 d) 37/63

7. Solder made for electronic parts has a:

a) Hollow Core c) Acid Core

b) Rosin Core d) No Core

8. The type of screw NOT mentioned in this course is:

a) Sheet Metal c) Round Head

b) Machine d) Self-threading

THEORY

Circle the letter that best fits the description.

PRACTICE

Open the Mechanical bag and answer the following questions.

EXTRA CREDIT

What is the function of the mechanical part(s) included in the bag that were not mentioned in the instruction

sheets?

How many of the following parts were in the mechanical bag?

Switches ______ Female PC Board Connectors ______ Male PC Board Connectors ______

Earphone Jacks ______ Wire Nuts ______ Spacers ______ Round Head Screws ______

Pan Head Screws ______ Flat Head Screws ______

Self-threading Screws ______ Sheet Metal Screws ______

Page 26

-25-

ANSWERS TO QUIZZES

PAGE 5

Type Capacitance Value Working Voltage Polarized (Y/N) Other Markings

Disc 33pF N —

Mylar .001μF 100 volts N K

Electrolytic 10μF 25 volts Y —

Electrolytic 220μF 25 volts Y —

Electrolytic 10μF 50 volts Y —

Electrolytic 10μF 16 volts Y —

Electrolytic 160μF 330 volts Y —

Answer to Extra Credit: 30μF

COLOR 1 COLOR 2 COLOR 3 COLOR 4 VALUE PERCENT WATTAGE

Brown Black Black Gold 10Ω 5% 1/2 Watt

Brown Green Brown Red 160Ω 5% 1/2 Watt

Brown Black Red Gold 1,000Ω 5% 1/4 Watt

Brown Red Red Gold 1,200Ω 5% 1/2 Watt

Red Yellow Red Gold 2,700Ω 5% 1/2 Watt

Brown Black Orange Gold 10,000Ω 5% 1/2 Watt

Blue Red Orange Gold 62,000Ω 5% 1/4 Watt

Red Black Green Gold 3,000,000Ω 5% 1/2 Watt

Green Brown Green Gold 5,100,000Ω 5% 1/4 Watt

Brown Black Blue Gold 10,000,000Ω 5% 1/2 Watt

1.c 2.a 3.d 4.a 5.c 6.d 7.b 8.a 9.b 10.d

PAGE 11

1.d 2.a 3.b 4.c 5.a 6.d 7.d 8.c 9.c 10.a 11.b 12.d

PAGE 16

1.d 2.a 3.b 4.a 5.b 6.c 7.a 8.a 9.b 10.b 11.c 12.b

Practice: No - the coil is not wound on a metal core. Enamel coating on wire prevents it from shorting.

There are 5 turns on the coil. Calculated inductance is 64 microhenrys.

Answer to Extra Credit: 30μH

PAGE 20

1.b 2.b 3.d 4.c 5.a 6.c 7.d 8.a 9.d 10.b

Practice: 3 Diodes 3 Transistors 1 Integrated Circuit Yes, 1 LED

A line is painted around the end that blocks current. LED uses flat side to indicate blocking end.

Answer to Extra Credit: Resistor is necessary to limit current and prevent LED from damage. LED’s are

diodes that only pass current in one direction.

PAGE 24

1.c 2.d 3.b 4.d 5.d 6.a 7.b 8.a

Practice: 1 Switch 1 Female 1 Male 1 Earphone Jack 1 Wire Nut 2 Spacers 1 Round 9 Pan

1 Flat Head 2 Self Threading 2 Sheet Metal

Answer to Extra Credit: Part in bag that was not mentioned included one strain relief to hold a line cord.

Parts included for further study were 2 thicknesses of rosin core solder and 1 printed circuit board. Using a

razor blade, slice solder on an angle to see internal flux.

Page 27

-26-

Space War Gun

K-10

Rapid fire or single shot with 2

flashing LEDs.

0-15V Power Supply

K-11

A low-cost way to supply

voltage to electronic games,

etc.

Christmas Tree

K-14

LED Robot Blinker

K-17

You’ll have fun displaying the PC

board robot.

Learn about

free-running

oscillators.

Digital Bird

K-19

You probably have never heard

a bird sing this way before.

Nerve Tester

K-20

Test your ability to

remain calm.

Indicates

failure by

a lit LED or

mild shock.

Yap Box

K-22A

This kit is a hit

at parties.

Makes 6

exciting

sounds.

Burglar Alarm

K-23

Alarm for your car, house, room,

or closet.

Whooper Alarm

K-24

Can be used as a

sounder or siren.

Metal Detector

K-26

Find new money and old

treasure. Get started in this

fascinating

hobby.

Pocket Dice

K-28

To be used with any game of

chance.

FM Microphone

AK-710/K-30

Learn about microphones,

audio amplifiers, and RF

oscillators. Range up

to 100 feet.

Telephone Bug

K-35

Our bug is only the size of a quarter,

yet transmits both sides of a

telephone conversation to any FM

radio.

Sound Activated Switch

K-36

Clap and the light comes on . . .

clap again and it goes off.

Lie Detector

K-44

The sound will tell

if you are lying.

The more you lie,

the louder the

sound gets.

Motion Detector

AK-510

Use as a sentry,

message

minder, burglar

alarm, or a

room

detector.

Two IC AM Radio

AM-780K

New design - easy-to-build,

complete radio on a single PC

board. Requires 9V battery.

Transistor Tester

DT-100K

Test in-circuit

transistors and

diodes.

Telephone Line Analyzer

TWT-1K

A telephone line analyzer kit

that tests active phone lines

with RJ-11 or RJ-45 modular

jacks.

Variable Power Supply

XP-720K

Three fully regulated supplies:

1.5-15V @ 1A, –1.5 to –15V @

1A or (3-30V @ 1A) and 5V @

3A.

EDUCATION KITS

Complete with PC Board and Instruction Book

Requires 9V battery

Requires

9V battery

Requires

9V battery

Requires 9V battery

Requires

9V battery

Requires

9V battery

Requires

9V battery

Requires

9V battery

Requires 2

“AA” batteries

Training course incl.

Requires

9V battery

Requires

9V battery

Requires

9V battery

Requires 9V battery

Produces flashing

colored LEDs

and three

popular

Christmas

melodies.

Requires

9V battery

No batteries required!

Requires

9V battery

0-15VDC @ 300mA

Page 28

ELENCO

®

150 Carpenter Avenue

Wheeling, IL 60090

(847) 541-3800

Website: www.elenco.com

e-mail: elenco@elenco.com

Loading...

Loading...