Page 1

A2ASIMULATIONS

COMANCHE

www.a2asimulations.com COMANCHE 250 MANUAL

FOR SIM ULATIO N USE ONLY

ACCU-SIM COMANCHE 250

:::

A2ASIMULATIONS

1

Page 2

ACCU-SIM COMANCHE 250

© 2015 A2A Simulations Inc. All rights reserved.

Published by A2A Simulations Inc.

ATTENTION!

Accu-Sim Comanche 250, including sounds, aircra, and all content

is under strict, and enforceable copyright law. If you suspect anyone has pirated any part of Accu-Sim Comanche 250, please contact

piracy@a2asimulations.com

RISKS & SIDE EFFECTS

Ergonomic Advice

▶ Always maintain a distance of at least 45cm to

the screen to avoid straining your eyes.

▶ Sit upright and adjust the height of your chair so that

your legs are at a right angle. The angle between your upper and forearm should be larger than 90º.

▶ The top edge of your screen should be at eye level or be-

low, and the monitor should be tilted slightly backwards, to prevent strains to your cervical spine.

▶ Reduce your screen’s brightness to lower the con-

trast and use a flicker-free, low-radiation monitor.

▶ Make sure the room you play in is well lit.

▶ Avoid playing when tired or worn out and take

a break (every hour), even if it’s hard…

Epilepsy Warning

Some people experience epileptic seizures when viewing flashing lights or

patterns in our daily environment. Consult your doctor before playing computer games if you, or someone of your family, have an epileptic condition.

Immediately stop the game, should you experience any of the following

symptoms during play: dizziness, altered vision, eye or muscle twitching,

mental confusion, loss of awareness of your surroundings, involuntary

movements and/or convulsions.

Page 3

A2ASIMULATIONS

COMANCHE

ACCU-SIM

COMANCHE 250

Page 4

Page 5

CONTENTS

6

30

32

34

38

42

48

52

54

DYNAMIC ELEGANCE

DEVELOPER’S NOTES

FEATURES

QUICK-START GUIDE

ACCU-SIM AND THE COMANCHE 250

ACCU-SIM AND THE

COMBUSTION ENGINE

PROPELLERS

GENERAL

LIMITATIONS

62

70

74

84

88

92

100

PERFORMANCE

WEIGHT AND BALANCE

AIRPLANE & SYSTEM

DESCRIPTIONS

EMERGENCY PROCEDURES

EMERGENCY PROCEDURES

EXPLAINED

AIRPLANE HANDLING,

SERVICE & MAINTENANCE

CREDITS

56

NORMAL PROCEDURES

Page 6

DYNAMIC ELEGANCE

Mitchell Glicksman

6

A2ASIMULATIONS

:::

COMANCHE 250 MANUAL www.a2asimulations.comFOR SIM ULATIO N USE ONLY

Page 7

O AIRPLANE PERSONIFIES THE EPITHET

“Dynamic Elegance” more aptly than does

N

the Piper Comanche 250.

The unique conjoining of many

superlative aeronautic and aesthetic

qualities marks this very special aeroplane. It has been said that if an aeroplane looks right, it will fly right. In this

it is supposed that the eye’s natural

ability to sense the pleasing proportion

and intrinsic eiciency of a design is a

reliable predictor of similarly excellent

aeronautic performance. The Comanche

250 proves that this adage may be relied

upon and bears validity. The Piper

Comanche takes its well-deserved place

on an illustrious list of aeroplanes which

are both so very pleasing to the eyes and

which are equally capable of superior

performance.

There are many including this writer

who hold that the Comanche is among

the most beautiful of all General Aviation

(GA) aircra, if not the most beautiful.

From any angle the Comanche treats the

eyes. This is what provides its elegance.

Its superlative performance is a matter

of record and this provides its dynamism. These two great and rare qualities, beauty and performance would be

enough in and of themselves to place the

Comanche at the pinnacle of GA aircra,

but the Comanche possesses an additional quality, one which, aer all, may

be its most endearing.

Of all of the high performance GA aircra the Comanche is arguably the least

demanding of the relatively low- time

pilot. That this is so is not an accident

or a fortuitous circumstance -- William

Piper specifically intended that it should

be so. The Comanche’s forgiving flight

characteristics and its refusal to turn and

bite an unwary pilot without plenty of

warning, its relatively gentle stall, easy

handling at low airspeeds and its overall

delightful handling at all airspeeds are

confidence boosters for its fortunate

pilots.

The Comanche is also particularly

exceptional in that it does not achieve

its excellent aerodynamic performance

at the expense of interior room and

comfort; it is among the roomiest and

most comfortable of “high performance”

aeroplanes. Neither does the Comanche

sacrifice useful load nor its generous

weight and balance envelope at the altar

of high airspeed. It is a highly capable

heavy load hauler and its capacious

useful load as well as its ability to safely

carry baggage and substantial rear seat

passengers without straining its a load

limits is far better than its closest competitors of equal horsepower -- including and specifically the V-tail Beechcra

Bonanza. Perhaps most importantly, the

Comanche does not achieve its performance by the intrinsic design features

which compromise stable flying characteristics. Its light airframe weight and its

generous, high aspect-ratio, laminar flow

wing provides the Comanche with high

eiciency as well as a low wing loading.

Accordingly, Comanche pilots and

owners are particularly loyal and satisfied, and for good reason; the Comanche

delivers extraordinarily dynamic performance while embodying the highest

degree of aeronautic elegance.

So, how is it that all of these superlative qualities came together in this aeroplane? Well, therein lays the Comanche’s

tale, one redolent of aeronautic expertise, prescience, confidence and also of

a fierce competitive spirit. As it happens,

it all began a little more than ten years

before the first Comanche ever flew.

Once upon a time…

www.a2asimulations.com COMANCHE 250 MANUAL

FOR SIM ULATIO N USE ONLY

:::

A2ASIMULATIONS

7

Page 8

DYNAMIC ELEGANCE

THE MODERN AGE OF

THE PRIVATE AIRPLANE

BEGINS — ENTER THE

BEECHCRAFT BONANZA

Summer, 1945 -- While the world is joyously celebrating the Allied victory in

Europe, World War II is still savagely raging

in the Pacific. The United States’ combined

armed services along with those of its

valiant Allies are pressing forward, island

by terrible island at horrific human cost,

drawing an ever- tightening noose around

the neck of the Imperial Empire of Japan.

As the final victory and a new era of peace

looms nearer and nearer the American

General Aviation (GA) industry made up

of companies such as Piper, Cessna, Ryan,

Stinson, Luscombe and Beechcra is

already making plans for what they expect

and fervently hope will come aer the

War is finally over. Unfortunately or perhaps inevitably, expectations, which are

so oen fragile and which are ultimately

as insubstantial as vapour are also as precious as dreams; and like dreams expectations are oen rendered irrelevant and are

ultimately crushed by brutish reality. Aer

almost four years of stifling limitations

incurred by the unavailability of raw materials, machinery and workers, all of which

and whom went into the War eort, the

GA industry had become, or perhaps more

accurately had succumbed to becoming

manufacturers of solely that which the War

Department required and demanded.

Thus, those American GA companies

who persevered performed their needed

part as highly regulated cost-plus cogs in

the War’s wheels, first under the WPB (War

Production Board) and then under the

OWM (Oice of War Mobilisation), subject

as well to the rules and regulations of the

OPA (Oice of Price Administration) and

the WMC (War Manpower Commission).

Piper, for instance, just as it was beginning to achieve the blessings of it’s longworked- for financial success in the late

1930’s was compelled in 1941 to convert

its popular J-3 Cub into a military scout,

an artillery spotter, a short- field, short

distance transport vehicle for a pilot and

a single V. I. P., and for a (mercifully) short

while, amazingly, a motorless three-place

glider trainer. Cessna turned out the AT-17

“Bamboo Bomber”, a multi-engine trainer,

the AT-17, etc., Beechcra built the AT-7

Navigator/C-45/UC-45/CT-128 Expeditor

From its inception

the Bonanza was

intended to largely

appeal to the

corporate/business

community as we

see here. However,

in this one we also

see a little of the

Western, “Camp

out with your

Bonanza” outdoor

flavour which was

another intended

part of the appeal

that Beechcraft

wanted to make.

There would be a

lot more of this kind

of appe al in ads to

come and all of this

coming long before

the television show

of the same name.

The main picture is

interesting. These

men must have

been as small as

elves to have that

much head and

shoulder room in

the Bonanza’s cabin.

Also, those guys in

the back had better

have been very slim

and lightweight,

the V-tail Bonanza

cannot take much

of an af t load.

versions of its sturdy and thoroughly excellent twin-engine Model 18, and so on with

regard to all within the GA industry.

The irony of it was that for all of the

splendid work and muscular energy spent

producing aircra for the war eort, none

of these very mission- specific wartime

airplanes were designed for or expected to

ever be made available to the public at any

future time. And so, while a small profit

(very small to be sure) was earned from

their military manufacturing eorts, the

commercial aspects of GA manufacturers,

at least for the duration of the War, came to

a complete halt.

This is not to say that Piper and the

other GA manufacturers did not sincerely

desire to do their part in helping to win the

war. Their oicers and employees were as

patriotic as the best Americans and their

strenuous eorts substantially enabled

the inevitable victory. That being said, as

the War progressed they patiently waited

and anxiously looked forward to the postwar era wherein they might finally reap the

sweet commercial rewards of their recent

sacrifices by selling great shiploads of civilian airplanes to hoards of distinctly aviation- friendly and flight- familiar ex-service

pilots.

In the summer of 1945, as the War

wound down to its end, the owners, CEOs

and Boards of American General Aviation

manufacturers expected, or if you prefer,

dreamed that their anxiously anticipated

heighday was truly nigh. Aer all, they

reasoned (with a heavy dose of wishful

thinking) that when all of those young

aviators come home aer having experi

enced the joy and freedom of flying, they

would surely wish to continue in a simi

lar vein and become owners and pilots

of their own airplanes. They further rea

soned that when these young men (and

some young women as well) having been

released from the armed services sal

lied forth en masse, clamouring for airplanes to buy, the American GA Industry

would be right there, blithely and heartily

ready, cheerfully awaiting their chance

-

-

-

-

8

A2ASIMULATIONS

:::

COMANCHE 250 MANUAL www.a2asimulations.com

FOR SIM ULATIO N USE ONLY

Page 9

Notice the slow-moving automobile traffic

below over which the sleek, sparkling

silver Bonanza effortlessly travels.

More “C ampout with your Bonanza”. Business

and pleasure combined — irresistible appeal.

Pure business appeal. Note the oil rig pictured.

The upscale and super- expensive Bonanza was

strongly pitched to the burgeoning oil business.

to supply the anxious needs and desires

of these valiant and victorious aerial vet

erans. In any event, it sounded right and

no one apparently thought that there was

any flaw in that analysis and expectation.

One aircra manufacturer however,

Beechcra, did more than merely dream.

With the surrender of the Empire of Japan

on September 2, 1945 which marked the

end of W.W. II, the world commenced to dig

itself out of mountains of ruin and rubble,

account for and mourn numberless victims, and as soon as might be possible to

get on with life in the bright and promising era of Peace. In the United States that

which had been interrupted by the war was

now busy re-commencing. GA manufacturers were now free to produce aeroplanes

for the public with an unlimited supply of

necessary materials and workers.

While virtually all of the other GA manufacturers planned on oering pretty much

the same aircra or types of aircra that

they has built in the pre-war 30’s; Piper

oering the J-3 “Cub”, Cessna oering a

distinctly pre-war style aeroplane, the 5

seat C-190/195 as well as the two-place,

tailwheel equipped C-120, Taylorcra,

Aeronca, Stinson and Luscombe all once

again oering their pre-war designs;

Beechcra had another idea, a new idea.

Beechcra was bent upon producing

a brand- new aeroplane, something not

only entirely dierent from anything that

they had previously built, but something

new and exciting that had not yet been

seen in the GA world. This was the seminal

Bonanza Model 35 which was to become

the airplane that sparked and kick-started

post-war modern General Aviation.

Remarkably prescient in every way,

Beechcra well-named the new aeroplane, “Bonanza”. Even before Beechcra

had actually sold a single aeroplane, it

was already a remarkable economic success. Shortly aer its grand introduction

to the public by way of press releases and

magazine advertisements, corporations,

businesses and wealthy professionals

placed almost 1,500 orders in advance of

its release with thousands more orders

soon to come. Without any question the

Bonanza was an unqualified and immediate roaring success.

In 1947 Beechcra embarked upon a

very powerful and sweeping advertising

campaign to debut and introduce to the

public what it was confident would create

a sea-change in GA aviation. Beechcra

was right on all counts.

Let’s take a close look at a variety of

advertisements that illustrate the new

market Beechcra expected to serve with

the Bonanza. Here are some early (1947)

ads which were part of the campaign to

introduce the Bonanza to the public:

BEECHCRAFT’S BIG IDEA

Designed by Ralph Harmon and his associates in 1945 as the war was coming to an

end, the Model 35 Bonanza had its first test

flight on December 22, 1945. Incorporating

all of what was then known about aerodynamics, aircra structure and aviation

technology, the Bonanza’s clean, stressed

skin (monocoque) all-metal structure

was reminiscent of the recently lionised

Spitfires and Mustangs and in virtually

every way was a distinct departure from

previous mostly fabric covered, fixedundercarriage, tailwheel GA aircra.

The first Bonanza, the Model 35, had a

retractable tricycle undercarriage, a distinctive V-tail which was unique for GA

aircra and had seats for four adults. The

first Bonanzas were originally equipped

with an interesting and curious laminated

wood, electrically controlled, pilot adjustable, fixed pitch propeller. This was not an

automatic constant speed propeller which

was a common item even by 1945, but was

a variable pitch unit electrically adjustable

by the pilot to meet power requirements.

Some early Bonanzas that are still flying

still have this kind of propeller; however,

most of these propellers have been converted to metal blades.

The Model 35 was powered by a simple

to manage and inexpensive to run sixcylinder, horizontally opposed, air cooled

www.a2asimulations.com COMANCHE 250 MANUAL

FOR SIM ULATIO N USE ONLY

:::

A2ASIMULATIONS

9

Page 10

DYNAMIC ELEGANCE

165 hp Continental E-165 engine (O-470

family). High performance GA aircra,

including Beechcra’s, had traditionally

been powered by large 7 or 9 cylinder,

round radial engines which were thirsty

of fuel and oil. A moderate sized, horizontally opposed engine in the Bonanza was

a breath of fresh air which engendered the

colour of progressive modernism while

promising low fuel and oil consumption

and a much quieter cabin.

Unsurprisingly, the Bonanza spectacularly burst onto the GA market and was

undisputedly and justly acclaimed by all to

be the first of a new breed of GA aircra.

In 1945 at the time that the Bonanza

was being conceptualised, what late in the

following decade would become a new GA

culture largely populated by casual weekend aviation hobbyists who were primarily relatively low-time VFR-only pilots and

who flew in order to take their friends and

families alo for pleasant, good-weather

aerial jaunts and vacations and to consume that $100 hamburger in a restaurant

at some distant airport, did not yet exist,

nor could it then have then been foreseen.

Accordingly, in 1945 Beechcra’s design

philosophy and the targeted market for

the Bonanza was, as we shall see, in no

way aimed at the part-time aviation aficionados to come, but at an entirely different group of highly experienced pilots

who it was expected would own and/or be

hired to fly Bonanzas for businesses and

corporations.

Beechcra’s goal and expectations

for the Bonanza were clear: To create the

fastest aeroplane for its horsepower that

could carry up to four in relative comfort

which would be primarily purchased by

prosperous individuals, corporations and

businesses to be used as a luxury executive transport flown by experienced, exmilitary service pilots.

Yes, all during the war most Americans

hoped for, waited for, and expected that

peace would bring forth a brave and

prosperous New World, a World which

in August, 1945 had finally arrived.

Beechcra’s particularly clear prescience

was that this New World’s skies would

be greatly populated with aircra of all

shapes and sizes in general and with its

new, game changing Bonanza in particular.

As said, Beechcra’s plan included

the idea that those who would mostly be

flying the Bonanza would be primarily

those valiant young ex-Army, Navy and

Marine Corps aeroplane drivers who had

of late been regularly flying and fighting

at 40,000’ and at up to 400 MPH +. Many

of these soon- to- be Bonanza pilots had

regularly flown massive, heavy, fourengine aircra on perilous high-altitude,

long-range missions over Europe, East

Asia and throughout the Pacific Theatre.

It was assumed that they would not likely

regard flying the neat and trim little fourseat Bonanza with its 165 h.p. engine to be

much of a challenge. These were the pilots

whom Beechcra expected would be filling the rolls of those who would be flying

corporate V.I.P. s, business oicers and representatives to and from board and sales

meetings all over the country in post-war

peacetime America. Beechcra’s mission

was to see that as many of them as possible would be flying Bonanzas.

Beechcra’s vision turned out to be

at least partly true as it was primarily extransport and bomber pilots who filled

out applications with businesses and corporations of all kinds to become aerial

chaueurs. Apparently most of the fighter

pilots had had more than their fill of what

was, from their perspective, the “joy” and

“thrill” of flying.

What this meant regarding the design of

the Bonanza was that Beechcra properly

understood that these ex-military pilots

would need no coddling when it came

to providing an aeroplane suitable for

them to fly. Accordingly, taking extra care

to design the Bonanza to be a gentle and

easy handing aeroplane for a multitude of

casual, weekend, sportsman pilots did not

appear to be any part of Beechcra’s intent

or concern. It seemed that a clean design

was paramount, which could be sold most

readily, i.e. performance -- high speed, fast

climb, long range, eiciency, comfort, as

well as owner’s prestige and a kind of modern-world cool sexiness -- everything that

makes an aeroplane exciting and satisfying

to behold and to fly.

Not surprisingly the Bonanza’s fastgrowing reputation as the “best”, and

“most modern” private aeroplane

attracted a great many wealthy and wellhealed professionals and “sportsmen”,

many of whom had no more than perhaps

a few hundred hours flight time, if that

much, and who were largely of limited

aeronautic experience. They were used

to possessing whatever they wished and

could easily aord the newest of the new

and the best of the best. Not accidentally

Beechcra had placed Bonanza squarely in

that class of possessions; but therein was

the rub.

All aeroplanes are subject to that most

basic law of physics: where one thing

is gained, another must be diminished.

Accordingly, the design of all aeroplanes

necessitates many compromises. For

instance, maximum airspeed and performance for available power is generally

and most readily obtained at the expense

of various other flight characteristics that

would, say, make the aeroplane suitable

as a casual touring aeroplane, and vice

versa. Compromises in design must be

made favouring that which the manufacturer sees as its goal for any particular aeroplane. To achieve specific design

goals such as high airspeed, comfortable

cabin space, long range, heavy load carrying, gentle handling, moderate runway

requirements, etc. designers make choices

regarding an aircra’s dimensions, geometry, proportion, materials, weight, airfoils,

thicknesses, shapes, wing and power loading, etc. In creating a design which would

extract maximum airspeed from available

power, the Bonanza’s designers clearly

made specific choices and compromises,

many of which did not favour the low-time

pilot.

Aer a tragic V-tail separation during

early flight testing in 1946 which caused

the death of the test pilot and extensive

re-design and re-testing of the tail surfaces

(but not to a suicient degree as we shall

see), the existing problems seemed to be

cured and all went well. By the end of 1947

the first gleaming silver Bonanzas rolled

o the assembly lines. In its class and for

its time it was the epitome of GA aeronautical design and engineering -- fast,

beautiful and looking like nothing that

had come before. Sure, it was pricey at the

then great sum of $7,975.00 ($84,613.32 in

2015), however a 2015 Bonanza G36 costs

approximately $691,390 depending upon

installed electronics, equipment, etc.),

but to its well-healed purchasers price

was no object. In fact, the Bonanza’s high

price guaranteed exclusivity and granted

its owner distinct prestige and pride of

ownership.

10

A2ASIMULATIONS

:::

COMANCHE 250 MANUAL www.a2asimulations.com

FOR SIM ULATIO N USE ONLY

Page 11

The would-be fighter pilot ’s dream, the Cavalier Mustang appe ars

here in civilian pain t. Many were finished in “military” colours and

some wi th authentic camouflage and markings. While surely an

exciting prospective mount for any pilot, the Cavalier required long and

extensive training and was expensive to both purchase and to maintain.

It wasn’t for everyone and was not produced in large numbers.

The Bonanza early safety record might

have been bet ter if more of these pilots

entered general aviation after the war.

Upon the pre-production introduction of the Bonanza through an extensive advertising campaign (see above)

more than 1,400 paid pre-orders for the

aeroplane flowed into Beechcra’s sales

oices like a raging tide. Once production

commenced the waiting list to purchase a

Bonanza was in the many thousands.

Unfortunately, in those transitory and

awkward post-war years the Bonanza’s

commercial success story was not at all the

rule but the great exception. Encouraged

by the early and enormous success of

Beechcra’s Bonanza the other GA aeroplane manufactures breathlessly anticipated that they, too, might experience

similar success and so they waited for the

long- predicted hordes of customers to

come crashing in and snatching up their

aeroplanes. They waited, and waited and

waited.

As virtually all of the rest of the GA

industry lay substantially dormant, the

Bonanza firmly and thoroughly established Beechcra as the cutting edge and

the undisputed leading GA aircra manufacturer throughout the late 40’s and

through 1950s.

From its introduction the Bonanza had

been and was intended to be an instant

status symbol, a totem upon which its

owner might boldly announce apparent success and wealth. Very like Rolex,

Cadillac or Rolls-Royce, its exclusive high

price and universally recognised quality put the Bonanza in an exclusive class

which was highly attractive to businesses

and individuals who wished to be seen and

regarded as having the means to indulge

themselves in such conspicuous, “goldhatted, high- bouncing” consumerism.

And so it was that throughout the 50’s the

Bonanza’s reputation and sales continued

to soar and dominate the GA industry;

its place at the top of the GA food chain

remaining essentially unchallenged.

However, during the late 40’s and early

50’ the Bonanza did have a few notable

ambitious would-be competitors such as

the ultimate exotic, the civilianised P-51

fighter -- The Cavalier Mustang, the North

American/Ryan Navion, a four place lowwing, all- metal GA aircra based, no less,

upon the airframe of the P-51, the sleek

and swi Meyers 200, the eicient but cosy

Mooney MK-20, the classic Bellanca 14-13

Cruisair Senior and the 14-19-2 “230”

www.a2asimulations.com COMANCHE 250 MANUAL

FOR SIM ULATIO N USE ONLY

:::

A2ASIMULATIONS

11

Page 12

DYNAMIC ELEGANCE

North American /Ryan Navion. If it looks a lot like a four-place Mustang, it’s not a coincidence.

Its spacious interior and good handling made and continues to make the Navion

a popular choice. Around 3,00 0 were built and many are s till flying.

Meyer s 200. Similar in appearance and per formance

to the Navion but without the Navion’s “Mustang”

heritage, the excellent Meyers 200 nevertheless should

have been but was not a commercial success.

The Globe Swift. Two place and aerobatic it was and is the classic “poor man’s”

fighter aircraft. Many were sold, but being so small and lightweight, it was not

really in competition with the Bonanza and was never a real challenge.

The Bellanc a Cruisemaster. A totally original

design, fabric covered plywood struc ture with

a wooden spar wing. Quirky in appearance

and manufactured using old-school

construction methods and materials, the

otherwise excellently performing Bellanca

was not a popular post-w ar choice.

Cruisemaster, and the sporty, aerobatic,

two-place Globe/Temco Swi. However,

as excellent as these aeroplanes were

and are, not one of them, nor all of them

together put an appreciable dent in the

sales and popularity of Beechcra’s star

and king of the single-engine GA hill.

PIPER STEPS UP

TO THE PLATE

During Wold War II while it was perforce

turning out militarized versions of the J-3

and, of all things, glider trainers created

by cutting o a J-3’a engine and replacing

it with a streamlined nose section, Piper

Aircra did not entirely intend to rest upon

the popularity of its J-3 Cub as its sole

post-war product. The Comanche which

was to come to light in 1958 was Piper’s

first low-wing, all metal, single engine

aeroplane, but it was not the first one of

that type that they contemplated. At least

two Piper designs intended to be produced

aer the war were created in 1944, the PA-6

Sky Sedan and the PA-7 Skycoupe.

Originally named the PWA-6 and looking very like the Ryan Navion, the prototype Sky Sedan was a fabric-covered metal

frame, four-place, low-wing, “family” oriented aeroplane. Originally designed to be

powered by a 140 hp Franklin engine, the

prototype was later actually powered by

a 165 hp Continental E-165 engine (ironically the same engine as was used in the

Bonanza). While a favourite of William

Piper, the Sky Sedan’s performance with

its relatively anaemic engine was predictably unexceptional and disappointing,

so the project was laid to rest until aer

the war. In 1947 the second and last Sky

Sedan, named PA-6, was now all metal,

was now powered by a more appropriate

205hp Continental E-185 engine, and had

a one-piece windscreen.

Most painfully cognizant of the

Beechcra Bonanza’s well-deserved success, by the middle 1950s Piper Aircra

was anxious to produce its own modern, all

metal, retractable gear, high performance

single-engine aeroplane. Seeking to enter

and to dominate the high-performance GA

business aeroplane market and unseat the

now long-term, highly successful Bonanza,

Piper Aircra made ready to topple the

King and to take its place on the GA highperformance business aeroplane throne.

To this end, what became the Piper

12

A2ASIMULATIONS

:::

COMANCHE 250 MANUAL www.a2asimulations.com

FOR SIM ULATIO N USE ONLY

Page 13

PA-24 Comanche was developed to be

“The Bonanza Killer”. It was Piper Aircra’s

ambitious intention to not only put an end

to the Bonanza’s reign, but to put Piper

firmly on the map as GA’s leading and most

advanced aircra manufacturer. Piper

knew that to do all of this would require

an exceptional aeroplane, one that was

built and performed to the highest standards, was roomy and comfortable on long

flights, had solid, stable, predictable handling and exhibited gentle and forgiving

flight characteristics.

Of all, this last requirement was key.

Piper, having analysed the Bonanza design

was well-aware that as a trade-o for its

outstanding performance, Beechcra

had incorporated features in the Bonanza

which compromised pitch and roll stability, C. G. loading, slow and departed flight

regimes (stall/spin) and ease of flying,

making their otherwise excellent aeroplane more than a bit if a handful for lowtime and less experienced pilots. Piper

could clearly see the potential commercial

benefit of creating a better handling and

performing aircra using more modern

techniques and knowledge, and was confident that their new aeroplane would

be highly competitive and would deliver

excellent performance without going

down the same route of the Bonanza.

Another 1945 press release

regarding the PA-6.

A 1945 advertisement to tes t the water as to how the

public might react to the Sky Sedan. The performance

claims therein are, well…a bit optimistic.

THE CRACK IN THE

KING’S MIRROR

For all of its beauty, innovation, performance and commercial success the

Bonanza, when Piper more closely looked

upon it, showed that it possessed a

number of serious design compromises

which Piper believed were dubious at best

and alarmingly dangerous at worst. Mr.

Piper was convinced that he and his company had the ability to design and produce

an equal or better performing aeroplane in

every respect. By applying more advanced

aerodynamics and with a stronger, better

configured airframe, their new airplane

would possess overall gentle and predictable handling as well as solid, high speed

performance without compromise.

To be fair to Beechcra, by the time that

Piper began to design the Comanche in

1957, the Bonanza design was then more

than a decade old, and had fundamentally changed very little and was showing its age. Yes, over the years Beechcra

1947 Piper PA-6 Sk y Sedan planned advertisement photo.

This is the second and the last one to be built.

Note: GA aircr aft adver tising then and today makes all aeroplanes look roomier than they

may actually be by placing in the cock pit the smallest available passengers it can find

for photographs. Note the emaciated looking pilot and the miniature children.

Piper PA-7 Skycoupe

looking like something

from the film “H. G.

Well’s Things to Come”.

The only Skycoupe ever

built. An interesting and

futuristic design,

“It didn’t fly worth a

damn!” said Pug Piper of it.

www.a2asimulations.com COMANCHE 250 MANUAL

FOR SIM ULATIO N USE ONLY

:::

A2ASIMULATIONS

13

Page 14

DYNAMIC ELEGANCE

THE HENRY FORD

OF AVIATION

illiam T. Piper was an

extraordinary person.

W

dream perhaps, that the light,

private aeroplane would become

as ubiquitous in American society

as had the automobile. Merely

having an idea (or a dream) was

not; however, what made Mr.

Piper extraordinary. Mr. Piper

was, one might reasonably say,

a stubborn man. Once this idea

had firmly situated itself in his

imagination, he went to work to

make it become a reality, and

through fire and flood he never

ceased applying all of his being

towards that end.

aeroplane manufacturing

business until 1929 just as the

Great Depression was about

to commence. He was not an

engineer nor even at that time

a pilot (he did eventually obtain

his private pilot’s licence in

1941 at the age of 60). Up until

then Piper had been a successful crude petroleum developer

operating a number of lucrative

oil wells in and around Bradford,

Pennsylvania. Piper only became

aware of the Taylor Aircra

Company and its economic

failure by accident in that he was

one of a number of successful

local businessmen who were

seeking to shore up failing businesses in Bradford so as maintain

and foster local industry.

He had an idea, a

Piper did not enter the

In 1929 Piper, seeing that the

Taylor company was about to

drown he purchased $600 worth

of Taylor Co.’s then worthless

stock. Unfortunately this salvatory investment was insuicient

to stave o incipient commercial

disaster and Taylor went bankrupt in 1931. Piper then bought

the land and buildings owned

by Taylor Co. at the bankruptcy

sale for $761.00 and permitted

Taylor to use the facilities rentfree. Piper became the treasurer

and a board member of the new

Taylor Aircra Company with C.

G. Taylor the President in charge

of engineering. Piper reserved for

himself the responsibility to raise

capitol for the new company

and was, appropriately, the chief

salesman.

Aer a few abortive and tentative attempts to re-invigorate

Taylor Aircra Piper persuaded

C. G. Taylor to design an entirely

new and far simpler aeroplane

than the old complex Taylor

“Chummy” which was expensive

to build and, accordingly, carried

too high a sales price. That new

aeroplane eventually became the

J-3 Cub.

There are many similarities

between Henry Ford and William

T. Piper. Both men recognized

early in their careers that there

was an untapped market for their

particular products that could

be opened wide if an aordable

and reliable product became

available. They both understood

that a good, solid but no-frills

automobile/aeroplane could

be designed and so economically manufactured that it could

be oered at a price that most

Americans could aord. Like

Ford, Piper also implemented a

kind of assembly line to produce

aeroplanes, cannibalising an old,

broken carnival Ferris wheel and

parts from an old barn.

Despite his eorts to streamline the Piper aircra assembly

process, the hard fact is that

aeroplanes require far more

skilled hands-on work to build

that do automobiles. Accordingly,

Piper needed a fairly large, well

trained work force in his factory.

By 1940, with America still deep

in the throes of the Depression,

he employed more than 1,000

men and women full time,

average age 23, to build Piper

aeroplanes.

In the United States in the late

1930’s and early 1940’s the volume

of all light aircra sales did not

even approach one- hundredth

the volume of sales of automobiles and Piper Aircra Co.’s share

of the aviation business was, of

course, only a percentage of that.

Piper could only aord to pay his

employees a maximum wage of

.40¢ per hour while the contemporary automobile worker made

as much as .93¢ per hour. To keep

his employees he oered them

incentives, as had Henry Ford in

his early days.

He oered his factory workers the opportunity to rent a

Piper Cub to take lessons in

or to just to fly if they already

were pilots for no more than

the cost of the gasoline and oil,

which equalled approximately

$1.00 per hour. In an article

about William T. Piper Fortune

magazine said, ‘’He could tap

an unlimited reservoir of smart,

eager boys, so crazy about flying

that they were willing to work for

nothing if they could only start

their days o by laying hands on

a Cub wing.” As a sales incentive Piper also oered any J-3

purchaser eight hours free flight

instruction. As a kind of gentle

“payola” he extended this to the

media as well, oering free flight

training to writers who would

help to expose the public to

Piper’s aeroplanes.

Like Ford, Piper had a

firm conception of what his

company’s economic place was

and how he could use it to foster

Piper sales. Regarding the vast

economic Depression that was

overtaking the world in the 1930s

Piper later said, ‘’Everyone who

was still flying was starved into

using Cubs.’’ Also like Ford, Piper

chose a single colour for his aeroplanes. Ford had chosen black,

Piper chose yellow.

14

A2ASIMULATIONS

:::

COMANCHE 250 MANUAL www.a2asimulations.com

FOR SIM ULATIO N USE ONLY

Page 15

F-4U-1 Corsair

“Birdcage” landing

during aircraft

carrier trials on the

USSSangamon on

25 September 1942.

With flaps full down

the left wing has

suddenly stalled

befor e the right wing,

a trait common to the

NACA 23000 series

airfoil which was

incorporated in this

aeroplane. (notice that

the pilot has applied

full right rudder to

try to prevent going

over the side. He has

correctly applied no

right aileron because

trying to pick up a

wing with aileron when

in a stalled condition

in an aeroplane of

this class is usually

a fatal mist ake.)

had made a scant few improvements and

changes to the original Model 35, specifically with regard to higher performance

specs created by simply increasing horsepower, but the Bonanza of the middle to

late 50’s was essentially and substantially

the same as the 1946 model.

The 1957 Bonanza “H” was the first of

the high-powered Bonanzas. Except for

the marked increase in horsepower it,

too, remained essentially the same as the

1947 Model 35. It has the Model 35’s highly

tapered wing with an area of only 177.6 sq.

. to liing its 3,050 lb. gross weight (aer

various supplemental type certificates (S T

Cs). This puts its wing loading (maximum

gross weight divided by wing area) at 17.17

lbs. /sq. ., which was then the highest

wing loading for a single-engine GA aeroplane of its class and size (excepting the

Cavalier which was, of course, a civilianized P-51). As a comparison, a lighter Piper

Comanche at 2,800 lbs. gross weight with

a wing area of 178 sq. . has a lower wing

loading of 15.7 lbs. /sq. .

That the Bonanza’s wing was smaller

than perhaps it ought to have been was a

deliberate design choice. The shorter span

and less wetted area of the Bonanza’s wing

permitted greater airspeed but, of course,

greatly increased the Bonanza’s wing loading. Such airspeed gains as may be had

thereby come at the expense of ease of

flying for less experienced pilots and more

importantly, of safety for all pilots.

An aeroplane with a higher wing loading is more critical of less- than- expert

piloting techniques, particularly at lower

airspeeds and is more likely to literally turn

and bite if not handled expertly and well.

Aircra with high wing loadings are more

likely to suddenly enter an accelerated

stall (reaching critical Alpha) even whilst

airspeed is well above normal stalling airspeed (Vso) by turning too sharply and/or

suddenly applying positive pitch. Also, a

high wing loaded aircra is usually more

likely to spin out of an ordinary stall and

more likely to spin out of an uncoordinated

turn at low airspeeds.

While Beechcra actually experimented with a laminar flow airfoil on early

Bonanza prototypes, it ultimately and conservatively selected the old NACA 23000

series airfoils (wing root - 23016.5, wingtip - 23012) for the Bonanza. The NACA

23000 series airfoil dates back to 1935 and

was very widely used throughout that and

the following decade. The U. S. Navy F-4U

Corsair and F-8-F Bearcat incorporate this

airfoil.

While the NACA 23000 series airfoils

are reasonably useful for higher airspeed applications provided appropriate power is available, it does not produce as predictable and benign departed

flight characteristics as the Comanche’s

even faster and far more modern, scientifically designed NACA 64(2)-A215 laminar airfoil. This is partially but primarily

because the 23000 series of airfoils exhibit

a rapid Cl (Coeicient of Li) decline when

approaching stall Alpha (angle of attack)

and thereby are likely to produce a rather

abrupt stall/spin.

Precipitous le wing drop during landing was a serious and dangerous problem for the F-4U-1 Corsair which, like the

Bonanza, incorporates a NACA 23000 series

airfoil. This and other problems initially

disqualified the Corsair for U.S. Navy aircra carrier duty (although the Royal Navy,

desperate for a real, purpose-designed

carrier aeroplane, gladly accepted it even

with its serious low speed handling flaws

in June 1943 as the “Corsair I.”)

Accordingly, if for example when flying

an aeroplane with this airfoil such as the

Bonanza a pilot should overshoot his turn

to final, pulling harder to tighten the turn

may result in a sudden stall with an accompanying sharp wing drop or possibly an

over- the- top spin. Even during a normal

landing with full flaps, getting too slow in a

Bonanza can result in a sudden wing drop,

etc. Both of these scenarios have resulted

in numerous fatal accidents during landings in the Bonanza.

The Bonanza’s V-tail, so designed to

www.a2asimulations.com COMANCHE 250 MANUAL

FOR SIM ULATIO N USE ONLY

:::

A2ASIMULATIONS

15

Page 16

DYNAMIC ELEGANCE

reduce drag by eliminating one entire tail

surface and to look very cool has its advantages and also some apparent detriments.

In addition to its distinctive appearance

and even though each of the two surfaces

of the V-tail are larger in both span and

chord than any of the surfaces of a comparable three - surface conventional cruciform tail, Beech believed that the V-tail

would save weight and possibly create a

bit less drag. While not hard scientific fact,

perhaps the V-tail does help Bonanzas fly a

bit faster, but it is reported by many pilots

to be not as stable at slower airspeeds

as a conventional tail. Some pilots have

reported that they “ran out of rudder” in

strong cross-wind landings in a Bonanza.

This phenomenon might have actually

been caused by the Bonanza’s yoke and

rudder pedals bungee interconnect system

designed to enable coordinated turns with

the yoke only. Some pilots have reported

that the V-tail’s stall/spin characteristics

are, to put it politely, not as benign as

those of aeroplanes with a conventional

tail; although this may be more due to the

Bonanza’s high Alpha- sensitive airfoil. As

to V-Tail characteristics, opinions may vary.

Wind-tunnel tests later showed that the

Bonanza’s V-tail was also not structurally

suiciently robust and it would become the

focus of inquiry with regard to fatal accidents involving airframe failure in flight.

Some believe that Beechcra’s original

design philosophy regarding the Bonanza,

i.e. that since it would be largely flown by

highly experienced, professional pilots

that its flight characteristics need not lean

towards ease of flying for low-time pilots,

came home to roost as the number reports

of a number of structure-related accidents

began to toll during the 1950s. It was discovered that in virtually all of these accidents where the airframe had failed in

flight that the probable cause was attributable to either the pilot’s loss of control and/

or the pilot’s over control upon attempting a correction. Most of these accidents

occurred whilst a relatively inexperienced

pilot was hand-flying the Bonanza in IFR

conditions and in many instances while

the aeroplane was loaded so that the C.

G. (centre of gravity) was chock up against

or beyond its maximum permissible a

location.

A very serious V-tail Bonanza characteristic is that it is quite sensitive to

Compare

how the

Comanche’s

main wing is

set further

back, making

it more

suitable for

carr ying heav y

aft loads while

staying within

safe centre of

gravity limits.

You can

see, by

comparison,

the

Comanche’s

wing is 1-2

feet further

back.

weight and balance/C.G. considerations.

Early V-tail Bonanza’s (Model 35 through

35J) have a rather narrow C. G. range of

9.2”; i.e., between 76” and 85.2” a of

the horizontal reference datum line. As

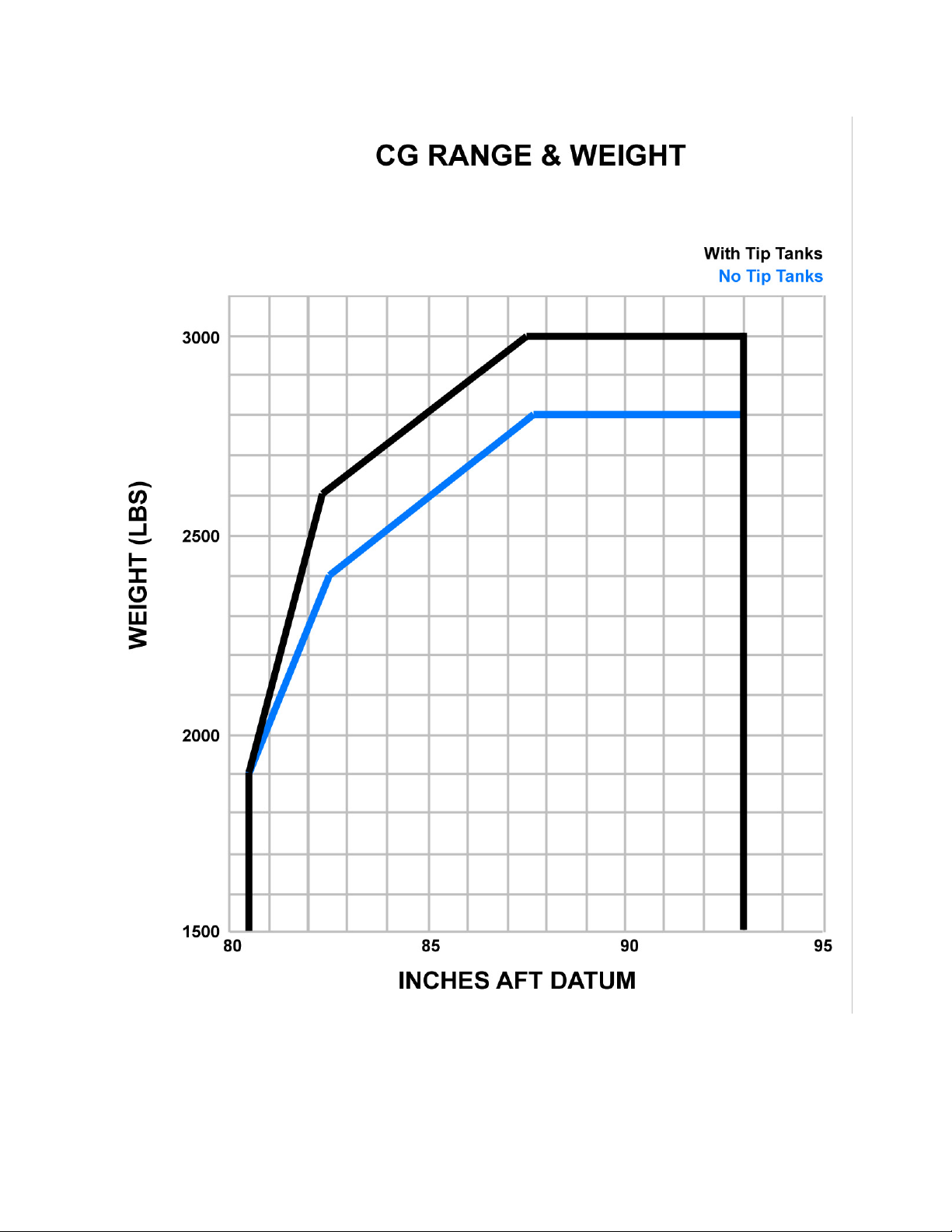

a comparison the 1958 Comanche 250’s

C. G. range is 12.5”; that is, between

80.5” and 93.0” of the datum line.

This indicates the Comanche 250 may

be loaded over a far greater distance

a of the datum line than a Bonanza

35H. Accordingly, it is particularly easy

to inadvertently load an early V-Tail

Bonanza a of its rear limits.

It is not well known, but all V-tail

Bonanzas, from the first until almost the

last, have a down spring connected to the

elevator control system which imparts

a constant forward push on the control

wheel. The elevator trim could override this

but it is always “on” and cannot be turned

“o”. An elevator control down spring is a

very unusual item for a GA aeroplane. That

Beechcra felt that it was necessary to

install this on the Bonanza speaks volumes

about the V-Tail design. It also makes one

wonder if Beechcra knew full well that

its speedy little aeroplane had some serious control issues at low airspeeds which

additionally would be greatly exacerbated

by a too-a C. G. loading. With this revelation one may justly wonder how the V-tail

Bonanza originally passed and continued

to pass airworthiness muster with the CAA

(Civil Aviation Administration) and later

the FAA (Federal Aviation Administration).

Ironically, it is the Bonanza’s greatest

characteristic, its aerodynamic cleanliness, that has been the cause of a good

deal of the peril experienced by low-time

Bonanza pilots who have recently transitioned to the Bonanza from lower-performance aircra. Unlike slower fixed gear airplanes, higher performance, streamlined,

16

A2ASIMULATIONS

:::

COMANCHE 250 MANUAL www.a2asimulations.com

FOR SIM ULATIO N USE ONLY

Page 17

retractable-gear airplanes will pick up

speed at an alarming rate by comparison

when the nose is lowered in flight. Once

airspeed is well-into the airspeed indicator’s yellow arc and certainly if it is past

the red line, any attempt to level the wings

and/or bring the nose back up which is not

executed with extreme delicacy and expertise (and in many instances even when performed so) will result in exceeding design

G-load, over-stressing and ultimately distorting the wings and/or the V-tail which

then is rendered useless to positively alter

the aircra’s pitch so as to regain level

flight causing the wings to fail and resulting in the aircra breaking up in flight.

Essentially, it requires very gentle rearward yoke pressure and some good fortune

to safely pull an over-speeding Bonanza

back to level flight and to slow it down

before something breaks. Too much rearward pressure when flying too fast and a

wing or two “may assume an independent

flight path from the rest of the airframe”

(credit to Darryl H.). Combine this trait

with an obscured or not visible horizon

situation or in actual IFR conditions and

where the unstable roll axis causes one of

the wings to drop as it will eventually do

if not strictly attended to, you have the alltoo-common deadly spiral dive. To make

things even worse, if the aircra is loaded

near, at or beyond its maximum permissible a C. G., which as said is all-too-easy

to do in a V-tail Bonanza, elevator response

becomes considerably more sensitive and

catastrophic over- control in an attempted

pull out becomes even more likely.

Assembling and analysing all of the

information at hand over more than a

decade the CAB determined that a VFR

pilot hand-flying the V-tail Bonanza in IFR

conditions was virtually certain to quickly

enter into a spiral dive and ultimately

suer a fatal crash.

ABOUT SPIRAL DIVES…

On 16 July 1999, John Kennedy Jr., was

flying his new Piper Saratoga II HP, the 300

hp retractable undercarriage Cherokee Six

from Essex County Airport, New Jersey to

Martha’s Vineyard on a hot and hazy summer’s evening with his wife and her sister

also on board. He had only 310 total flying

hours and only 36 hours in this demanding, high-performance aeroplane, some

instrument training but no instrument

Spiral Dive

ticket. At some point over the water he lost

sight of the horizon and suered from spatial disorientation. Inevitably, one of the

Saratoga’s wings went down and the nose

dropped. As airspeed wildly increased he

tried to pull up nose to slow the aeroplane

but merely tightened the spiral until the

Saratoga hit the water.

Many Bonanza pilots who were not professionals and those who were not used

toflying such a clean airplane which was

additionally unstable in roll found the

aeroplane to be more than a safe handful.

In the 1950s and early 1960s legal IFR

flying activity by GA pilots was very rare.

The IFR system was then still fairly crude

and not so widely available as it is today.

Additionally, in those days very few GA

and even ex-military pilots had instrument

ratings or had received any serious IFR

training. Accordingly, the vast majority of

Bonanza pilots were strictly VFR rated and

this was what got so many of them into

serious trouble.

As time passed and more and more

V-tail Bonanza in-flight structural breakups were reported, in 1989 Beechcra performed a series of wind-tunnel and other

practical tests on the V-tail Bonanza. It was

discovered that as designed the sensitive

V-tail could not be relied upon to permit

safe pilot application in the pitch axis even

when the aeroplane was flown within and

at one corner of its certified flight performance envelope. This could result in

structural failure of the V-tail which would

cause the aircra to quickly exceed its

safe airspeed limit and break up in flight.

V-TAIL AND C.G.

hen the C.G. is too far a in any

aeroplane the pilot will experi-

W

is able to takeo without mishap, overly

sensitive elevator control at cruising airspeeds and a sharp deficiency of elevator

control at low airspeeds, such as when

taking o and landing.

predecessor to the NTSB - National

Transportation Safety Board) accident

records show that a too far a C. G. was

tragically all-too-oen the probable

cause of fatal accidents involving early

V-tail Bonanza’s. They found that in many

instances an inexperienced or negligent

V-tail Bonanza pilot loaded the aeroplane

even slightly too far a and thereaer

experienced serious, oen fatal lowairspeed pitch control deficiency and/

or pitch over- control at high airspeeds

leading to structural failure.

that modern, cruciform- tail Bonanza

(which is actually the Debonair) have very

generous horizontal weight and balance

envelopes and do not suer from the

above mentioned condition.

considered to be rather light and sensitive in normal operations, and while the

aeroplane is only modestly stable in the

pitch axis (constant hunting whilst cruising), it is far less stable in the roll axis.

Reinforcements, stieners and cus

were applied to the V-tail which caused

Beechcra a good deal of angst as this was

proof positive that the Bonanza’s original

design which was produced for 35 years

was not adequate and was a contributing

cause of many fatal accidents.

In 1960, Beechcra produced the

Debonair, a slightly dressed- down

Bonanza with a conventional cruciform

tail. Many pilots report that the Debonair is

a better flying aeroplane than the Bonanza

at all times and particularly when in turbulence and that it does not tend to “hunt”

in pitch during normal cruise as do V- tail

Bonanzas. Most significantly, the conventional tail Debonair’s fatal accident record

is 24 times better than the V-tail Bonanza’s.

Because of all of the above in 1982

Beechcra stopped production of the V-tail

Bonanza, dropped the Debonair model

ence, assuming that he or she

CAB (Civil Aeronautics Board the

It should be mentioned in all fairness

The early V-tail Bonanza’s controls are

www.a2asimulations.com COMANCHE 250 MANUAL

FOR SIM ULATIO N USE ONLY

:::

A2ASIMULATIONS

17

Page 18

DYNAMIC ELEGANCE

Mooney M-20 with

German registration on

an airfield in Germany

and name, and continued to produce and

develop what is, in fact the conventional

tail Debonair, now calling it Bonanza.

To be fair, much of what caused lowtime pilots to have a very high rate of fatal

accidents when flying the Bonanza was,

as with John Kennedy, Jr. in the similarly

high - performance Saratoga, more due to

1958 Piper

Comanche 250

their inexperience with high-performance

aircra than any fault of the thoroughbred, high - spirited Beechcra. However,

because of its extremely high accident

rate, mostly while being flown by private

pilots without instrument ratings and no

more than 300-400 hours total flight time,

the Bonanza became popularly known as

the “The Doctor Killer”, referring to the

many well-o physicians who could aord

to purchase one, but who lacked suicient

flight time and expertise to fly it safely, and

who thereby came to a tragic end.

Additionally, as said, there have been

a rash of Bonanza structural failure accidents having to do with wings being pulled

o aer unintended over-speeding and too

abrupt pull outs.

ENTER THE COMANCHE

William T. Piper knew that in seeking to

enter the high-performance, single-engine

business aeroplane market and challenging the iconic Bonanza that he was

he was taking on a very tough, commercially risky task. As mentioned, from the

company’s inception, all production Piper

aircra had been high wing, fabric covered aircra. However, by the mid-1950’s

Piper was already planning for the future

and making changes towards the production of a more modern fleet. Indicative of

this, in 1954, in a single dramatic and bold

18

A2ASIMULATIONS

:::

COMANCHE 250 MANUAL www.a2asimulations.com

FOR SIM ULATIO N USE ONLY

Page 19

move, Piper splashed into the modern GA

market with its first low-wing, retractable

undercarriage, all- metal aeroplane -- the

four-seat, twin-engine PA-23 Apache which

was the first Piper to be named for a Native

American tribe.

Closely following his original concept of

simplicity which had created the venerable

“Cub”, Piper had his engineers design a

simple, no frills and relatively inexpensive

but well-performing light twin, the Piper

Apache. It quickly proved to be highly popular and, among other things, filled the

niche as an ideal and economical multiengine trainer and well as a personal touring aeroplane with the ostensible “safely

factor” of a second engine (some pessimists say that having two engines simply

doubles your chances of an engine failure,

but that is a minority opinion).

Besides enjoying a solid commercial

success, in the course of manufacturing

the Apache, Piper Aircra gained experience and confidence with regard to the

particular methods and ways of modern

all-metal aircra production. The days of

the highly labour- intensive fabric covered

tube frame aircra designs such as the

Tri-Pacer were quickly waning and with

success of the all metal Apache Piper saw

that the way was now clear for more of

the same.

During the four years aer the Apache

was introduced, Piper was actively planning to achieve its program reguarding

taking the Bonanza’s place in the highperformance GA market. There is more

than one popular, possibly apocryphal

version of the genesis of the Comanche

design, one of them is – Looking around

for a suitable high performance design, it

happened that a Mooney M-20, which had

been introduced in 1955 and which was

known for getting very high cruise numbers (149KTS top – 143KTS at 75% power at

7,000’) for its 150 hp (110 kW) Lycoming O

-320 engine,, was temporarily hangered at

Piper’s Lock Haven PA factory. As the story

goes, William T. Piper and his engineers

gave it a long, close look, measured every

aspect of it and used what they found to

come up with the Comanche design.

Another version goes like this -- William

T. Piper (or Howard “Pug” Piper, William’s

son, depending upon from whom you are

hearing the story) approached designer

Al Mooney with an oer to buy the M-20

design which would, with some modifications, thereaer become the new Piper

aeroplane. However, Al Mooney refused

to sell, but as an alternative Mooney

oered to design a brand-new aeroplane

for Piper to their specifications. According

to this version of the story, the specific

design features that Piper asked Mooney

to incorporate were: high cruise performance for available power (a Mooney

trademark); a relatively simple, light airframe and components which would be

economical to manufacture permitting

Piper to greatly undercut the Bonanza’s

notoriously high price; a more spacious

and comfortable cabin than that of both

the rather short and narrow M-20 and

even of the fairly capacious Bonanza;

and, especially a new, uniquely modern

appearance which would suggest speed

and eiciency to the aeroplane- buying

public.

Whatever the truth of the matter may be

(and I lean towards the second story) there

is no question that the final Comanche

design and the M-20 share many features.

Accordingly, it appears more likely that

Al Mooney and “Pug” Piper, who was in

charge of the development of the new

Piper aeroplane, cooperated to complete

the final design of what was to be Piper

Aircra’s first all-metal, low- wing, singleengine aeroplane.

To foster the “jet-age” sales concept

the Comanche’s design implemented was

what was then an innovative swept-back,

jet-like vertical fin and rudder, the first one

of its kind to appear on a mass-produced

GA aeroplane. This design feature was

something of an inside joke as it simply

reversed Mooney’s signature forward

sweeping tail.

The question always asked about swept

tails is whether with regard to an aeroplane that flies very far below trans-sonic

or supersonic airspeeds does the application of a swept tail increase airspeed? With

the Cessnas that changed to swept tails at

least there was some means to compare

the two configurations. In the instance of

the Cessnas the answer is that where all

other things are equal; no, there is no measurable increase in airspeed,

Unlike the Cessnas, there is no way to

compare a straight- tailed Comanche with

a swept tail version, so there may be no

definitive answer forthcoming. However,

taking the Cessna example into consideration, the answer is most likely that

the swept tail on the Comanche does not

cause any increase in airspeed. However, it

sure does look nice -- and fast.

Other innovative design features for

a GA aeroplane incorporated into the

Comanche’s design are the single- piece,

all- flying stabilator with anti-servo tab;

an all metal wing with a metal spar (1950’s

M-20s had fabric covered wings with a

wooden wing spar and fabric covered

wooden tail surfaces); and an NACA 64(2)A215 laminar airfoil similar to that of the

North American P-51 “Mustang” which

airfoil was designed to permit the highest possible cruising airspeed for available power. The Comanche’s wing has five

degrees of dihedral for good lateral stability while still retaining excellent roll rate.

The “laminar flow” airfoil is the invention of Eastman Jacobs, an aerodymicist

who worked for NACA (National Advisory

Committee for Aeronautics, the predecessor to today’s NASA- National Aeronautics

and Space Administration) in the 1930’s.

It was well- known by then that the thin

layer of air closest to the surface of an

airfoil, called the “boundary layer”, was

highly significant with regard to the

wing’s production of li and influenced

the way that high and low pressure areas

were distributed as they moved from the

wing’s leading to trailing edge. Jacob’s

conception was that if the boundary

layer could be made to adhere to and

remain parallel to the airfoil’s surface for

a longer distance from the leading edge of

the wing than the common airfoils being

used, drag would be markedly reduced.

Through wind-tunnel tests Jacobs determined that the thickest part of the airfoil

where the local pressure was lowest best

sustained an attached and parallel laminar flow boundary layer, but that as the

airfoil became thinner and local pressure

became higher the usual drag-producing

vortexes and eddies in the boundary layer

began to arise, eventually becoming turbulent and producing a good deal of drag.

Jacobs realised that if the thickest part of

the airfoil was moved back from its usual

25-35% position from the leading edge to,

say, the 40-50% position, that a good deal

of the drag produced by the long rear section of turbulent boundary layer could be

avoided.

www.a2asimulations.com COMANCHE 250 MANUAL

FOR SIM ULATIO N USE ONLY

:::

A2ASIMULATIONS

19

Page 20

DYNAMIC ELEGANCE

Additionally, the following is extracted

(and slightly edited) from the A2A

Cherokee 180 Manual as it applies equally

to the Comanche:

“Just a quick word or two about airfoils and what a “laminar flow airfoil” is.

The wing’s airfoil is its cross section shape

from leading to trailing edge and current aerodynamic theory holds that the

airfoil is primarily and most importantly

an air diverter. Among other things, the

airfoil diverts the air through which an

aeroplane’s wing travels downwards at

the wing’s trailing edge so that li may

be generated (see Newton’s Third Law of

Motion). In order to do this the “boundary

layer”, which is the very thin, viscous layer

of air closest to the surface of the wing,

must adhere to the wing and not become

turbulent or detach from the surface of the

wing before it can be diverted downward

at the trialing edge. There are many theories of li, some traditional, some imaginative and seemingly intuitive. However, in

recent years most of the traditional theories have been discredited as they were

found to be flawed, entirely improbable or

simply wrong as aeronautical knowledge

and understanding has progressed. It is

most likely that there are numerous ways

in which a wing produces li. The airfoil as

a downwash “air diverter” at the trailing

edge is and has for a while been what this

writer thinks is the most probable correct

theory. Of course, the true scientific mind

must always be open to new facts and

disclosures. This writer awaits with great

interest what is yet to be discovered.

Also, a smooth and adherent boundary

layer produces minimum pressure and/or

parasite drag enabling the aeroplane to

Note that the

laminar flow

airfoil’s thickest

point is farther

back from

the leading

edge than

the ordinary

airfoil’s.

fly faster for any given amount of power.

Slight micro-turbulation in the boundary layer actually increases its adherence

to the surface of the wing; but, when this

turbulation becomes more severe and

becomes a turbulent flow, li is reduced

and pressure drag increases. If this turbulence becomes too severe, which typically happens at critical positive Alpha, the

turbulent boundary layer detaches from

the surface of the wing creating random

eddies and vortices causing considerable

parasite and pressure drag to be produced.

Upon boundary layer flow separation from

the surface of the wing the former downward diverted air flow ceases and, concurrently, the wing ceases to generate li. This

is the “stall”.

An airfoil designed to produce maximum uninterrupted, adhesive boundary

layer flow at the surface of the wing and

minimum drag by moving the thickest part

of the airfoil back to the 40-50% point is

called a “laminar flow airfoil”.

NACA NUMEROLOGY

The first number, “6”, of NACA 64(2)-A215

(the Comanche’s airfoil) indicates that this

is a NACA “6-series” airfoil. The second

number, “4”, indicates the position in percentage x 10 of the chord (leading to trailing edge) where minimum pressure occurs

— here indicating the 40% chord position.

Minimum pressure usually occurs at the

thickest part of the airfoil. The subscript

“2” indicates that this airfoil’s Cd (coeicient of drag) approximates its minimum

value between plus or minus 0.2 of the

airfoil’s design Cl. (coeicient of li). The

NACA 65(9)-415 airfoil which was used for

the Cherokee is a later refinement of the

Comanche’s NACA 64(2)-415. The only significant dierence between the Cherokee’s

airfoil and the Comanche’s is that in the

Cherokee’s airfoil the Cd approximates its

minimum value between plus or minus

0.9 of the airfoil’s design Cl while the

Comanche’s Cd approximates its minimum

value between plus or minus 0.2 of the airfoil’s design Cl. The next number “2” indicates the li coeicient in tenths; here, 0.2.

The last two numbers, “15”, indicate the

wing’s maximum thickness as a percentage of the chord; here, 15% of the chord. A

laminar flow airfoil is typically designed so

that its thickest point is usually at approximately 40-50% of the chord. A normal airfoil’s (Bonanza’s) thickest point is usually

at approximately 25- 33% of the chord. The

laminar flow airfoil shape combined with a

very smooth wing surface best promotes a

smooth and adherent boundary layer fostering higher airspeed capability.

COMANCHE DESIGN

The North American P-51 “Mustang” was

the world’s first purely mathematically

designed aeroplane and its wing was

the first to be deliberately designed with

a “laminar flow” airfoil. However, even

a very slight ripple or bump in or on the

surface of the wing will prevent the true

laminar flow eect. Despite all good

intentions what with numerous hatches

and doors and such for the maintenance

of guns, reloading of ammunition and

the like the P-51’s wing surface as manufactured is not suiciently smooth and

uninterrupted nor was it optimally built

or suiciently maintained to be clean in

the field to promote true laminar flow.

The Comanche’s wing surface, however, is

actually far smoother and if kept scrupulously clean, promotes a stable, adherent

boundary layer very well. A salient characteristic of the Comanche’s airfoil is that

it has a fairly flat Cd curve right up to the

stall and thereby looses li very slowly

as the stall is approached, although

not to the extent as does the Cherokee

with its slightly more advanced laminar

flow shape. Also, the Cherokee’s airfoil

does not possess a single critical angle

of attack (positive Alpha) at which it will

stall. The Comanche’s NACA 64(2)-415

airfoil flies within a fairly broad range of

positive Alpha (limited only by the wing’s

aspect ratio as discussed below) and does

20

A2ASIMULATIONS

:::

COMANCHE 250 MANUAL www.a2asimulations.com

FOR SIM ULATIO N USE ONLY

Page 21

not break very sharply at the stall unless

very aggressively forced into an extreme

positive Alpha condition called a “deep

stall”. Spins are likewise diicult to enter

unless aggressively pursued.

Another design feature that is an innovation, at least and certainly for Piper in

the late 1950s, is the Comanche’s high

aspect ratio (AR) wing at 7.53 (see calculations below). The AR is the mean chord

(measured from the leading to the trailing

edge) divided into the overall wingspan

(which includes the width of the fuselage).

The average AR for GA single –engine aeroplanes is between 5 and 6. That is the chord

is 1/5th or 1/6th the span. AR lower than 5

is considered to be in the low AR range and

above 6 to be in the high range.

For wings that are tapered (not rectangular) as is the Comanche’s wing, the

AR is calculated as the square of the span

divided by the wing area. AR= span (sq.)/

area. The Comanche’s wingspan is 36 .

and its area is 172 sq. .

Span squared divided by the wing’s

area = aspect ratio

Span- 36 (sq.) =1,296 wing area=172;

accordingly, 1,296/172= 7.53.

This is a rather large AR which gives the

Comanche’s wing specific characteristics.

A higher AR wing is more eicient than

a wing of the same area but with a lower AR

for the following reasons:

As discussed above li is primarily a

product of downwash at the trailing edge.

Where there is more clear trailing edge

available to produce downwash, more li

will be produced.

The wingtip and its proximate area produces little to no li and produces a strong

drag - producing vortex caused by the high

air pressure below the wing swirling into

the lower air pressure above the wing, all

of which is called “tip eect”. The force

and depth tip eect into the wingspan on

wings of approximately the same area (but

not necessarily of the same AR) is roughly

equal.

Accordingly, the greater the distance

the tip of the wing and the resulting tip

eect is from the wing root the greater the

clear span of li -producing trailing edge

and lesser the relative tip eect on the

entire wing.

As shown, the tip eect is approximately

the same regardless of the length of otherwise similar wings. Accordingly, the higher

AR wing is less negatively aected by tip

eect than the lower AR wing increasing

the eiciency of the higher AR wing.

Additionally, as the AR increases the CL

increases and less Angle of Attack (Alpha)

is required to produce li, increasing eiciency once again.

However, the graph above also indicates that higher AR wings stall at a lower

Alpha. This means that the higher the AR of

the wing is the less useable positive Alpha

it has.

www.a2asimulations.com COMANCHE 250 MANUAL

FOR SIM ULATIO N USE ONLY

:::

A2ASIMULATIONS

21

Page 22

DYNAMIC ELEGANCE

Radio controlled Cur tiss Robin model popular for sailplane

towing. Note the average aspect ratio of the wing.

A PRACTICAL

DEMONSTRATION OF THE

EFFECTS OF ASPECT RATIO

This particular principle of aspect ratio

was illustrated to me in an interesting and

clearly demonstrative way one day a few

years ago when I was visiting some friends

at a local radio-controlled (R/C) model

aeroplane field. Some of the pilots had

large un-powered sailplanes which they

would get up to thermal (where the air

has natural li) altitude by having another

pilot aero-tow it. The sailplane had a radiocontrolled towline release mechanism

when the sailplane pilot was high enough.

The tow aeroplane was a very large and

sturdy, a sort- of- scale Curtiss Robin with a

96” (8’) wing and a powerful 62cc gasoline

engine with a 22x10” propeller. The AR of

the Robin’s wing was average, the average

chord approximately 17 ½”, 5.5 of the span.

However, the sailplanes were all between

4 meters (13.12’) and 5 metres (16.40’) and

had very high ARs of 20-30; that is, their very