Page 1

A2ASIMULATIONS

CHEROKEE

ACCU-SIM CHEROKEE 180

Page 2

ACCU-SIM CHEROKEE 180

© 2014 A2A Simulations Inc. All rights reserved.

Published by A2A Simulations Inc.

ATTENTION!

Accu-Sim Cherokee 180, including sounds, aircra, and all content is under

strict, and enforceable copyright law. If you suspect anyone has pirated any

part of Accu-Sim Cherokee 180 Trainer, please contact piracy@a2asimulations.com

RISKS & SIDE EFFECTS

Ergonomic Advice

▶ Always maintain a distance of at least 45cm to

the screen to avoid straining your eyes.

▶ Sit upright and adjust the height of your chair so that

your legs are at a right angle. The angle between your

upper and forearm should be larger than 90º.

▶ The top edge of your screen should be at eye level or be-

low, and the monitor should be tilted slightly backwards, to prevent strains to your cervical spine.

▶ Reduce your screen’s brightness to lower the con-

trast and use a flicker-free, low-radiation monitor.

▶ Make sure the room you play in is well lit.

▶ Avoid playing when tired or worn out and take

a break (every hour), even if it’s hard…

Epilepsy Warning

Some people experience epileptic seizures when viewing flashing lights or

patterns in our daily environment. Consult your doctor before playing computer games if you, or someone of your family, have an epileptic condition.

Immediately stop the game, should you experience any of the follow-

ing symptoms during play: dizziness, altered vision, eye or muscle twitching, mental confusion, loss of awareness of your surroundings, involuntary

movements and/or convulsions.

Page 3

A2ASIMULATIONS

CHEROKEE

ACCU-SIM

CHEROKEE 180

Page 4

CONTENTS

6

34

36

38

40

44

48

54

PIPER CHEROKEE PA-28-180 AN

AEROPLANE FOR THE REST OF US

CHEROKEE SPRING

DEVELOPER’S NOTES

FEATURES

QUICK-START GUIDE

ACCU-SIM AND THE CHEROKEE 180

ACCU-SIM AND THE COMBUSTION ENGINE

PROPELLERS

58

GENERAL

60

LIMITATIONS

4

A2ASIMULATIONS

:::

CHER OKEE 180 MAN UAL www.a2asimulations.com

Page 5

62

NORMAL PROCEDURES

68

76

78

86

90

94

102

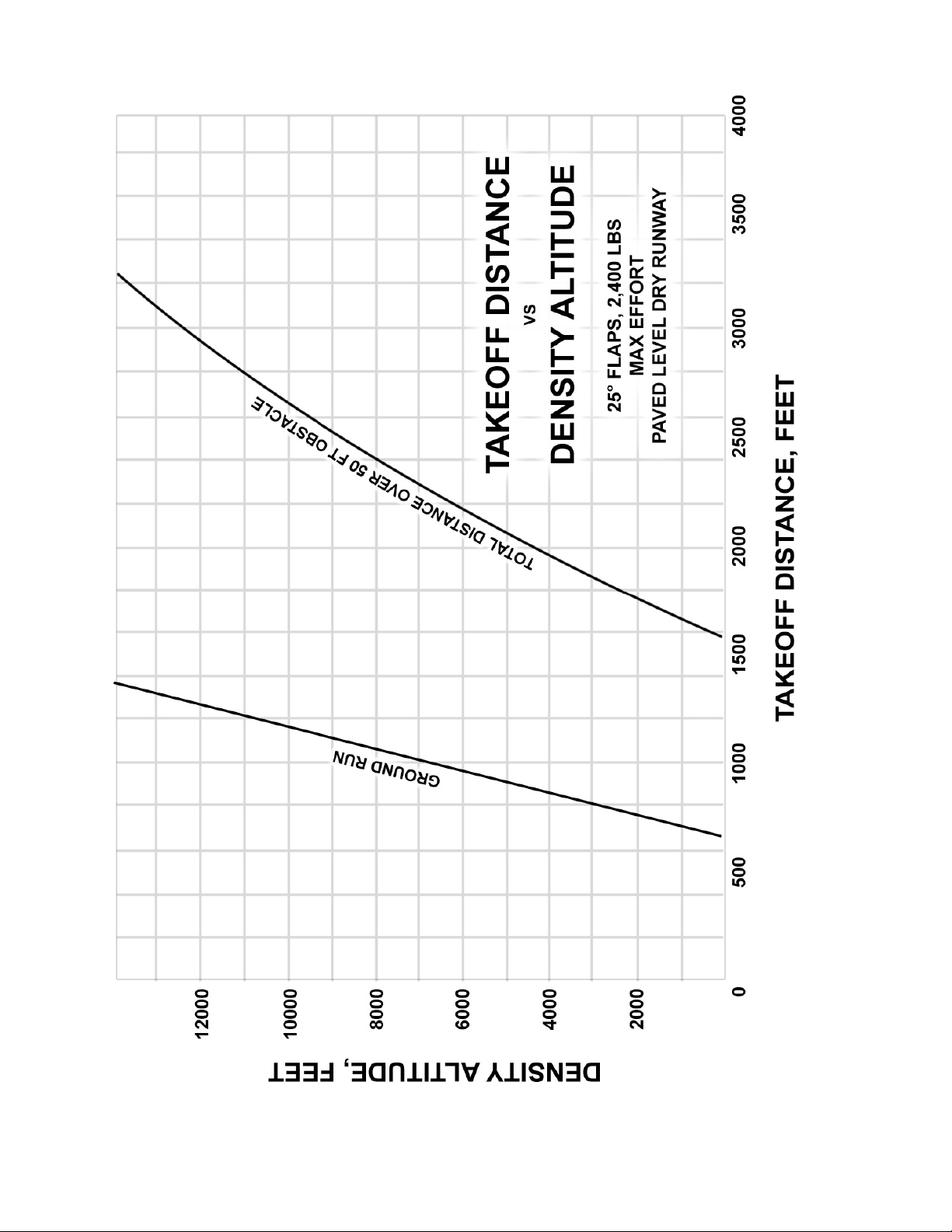

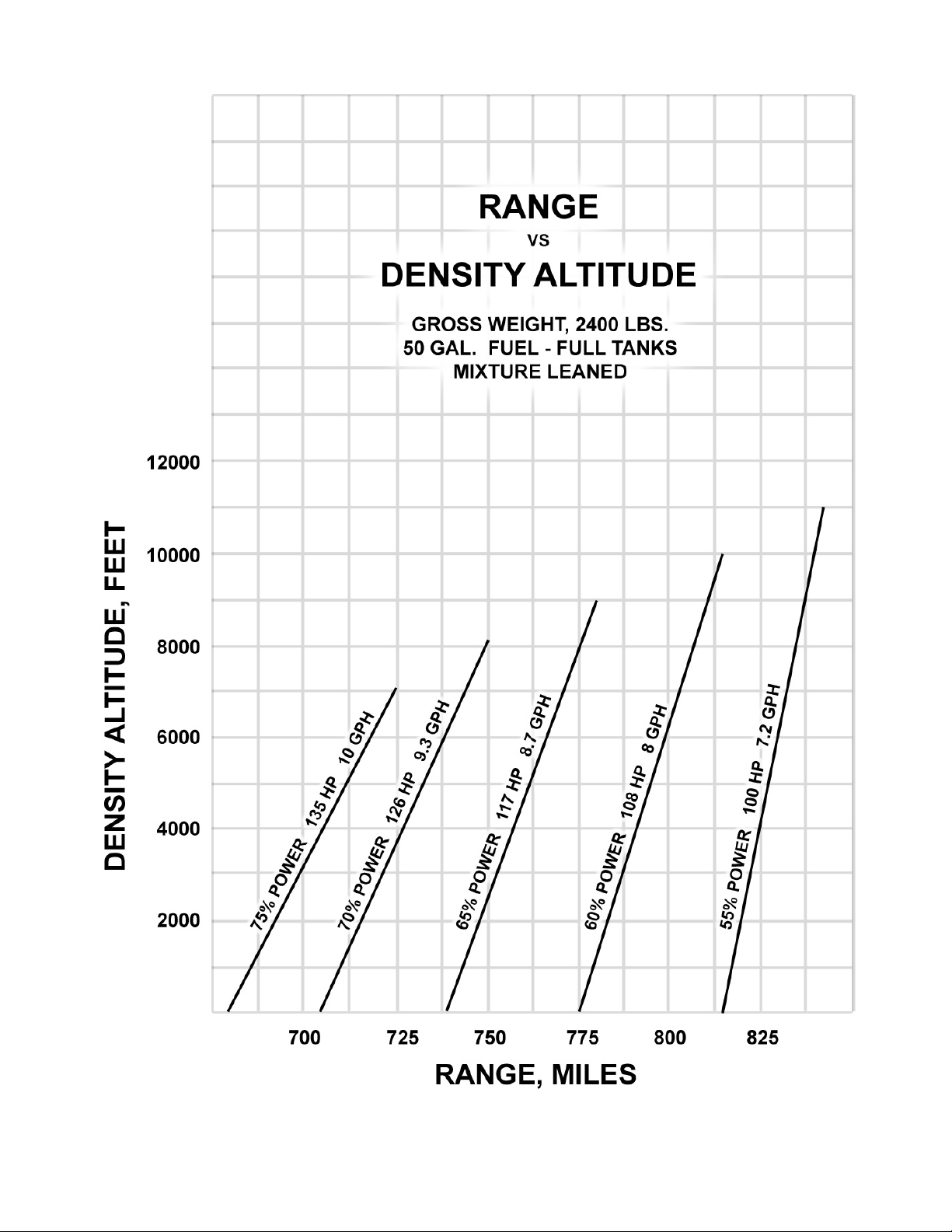

PERFORMANCE

WEIGHT AND BALANCE

AIRPLANE & SYSTEM DESCRIPTIONS

EMERGENCY PROCEDURES

EMERGENCY PROCEDURES EXPLAINED

AIRPLANE HANDLING,

SERVICE & MAINTENANCE

CREDITS

www.a2asimulations.com CHERO KEE 180 MAN UAL

:::

A2ASIMULATIONS

5

Page 6

PIPER CHEROKEE PA-28-180 AN AEROPLANE FOR THE REST OF US

By Mitchell Glicksman

This flying machine may rightly be called a “Goldilocks”

aeroplane. It is not too big and not too small, not too

complex and not too simple, etc. The Piper Cherokee

180 is, as the little flaxen-haired girl so famously declared, “Just right!”

The entire PA-28 Cherokee line from the humble

two- seat 150 h.p. PA-28-140 to the swi, retractable undercarriage PA-28R-200 Arrow, to the powerful, heavy

load-carrying 235 h.p. PA-28-235 Dakota, is respected as

being one of the most popular, commercially successful series of aircra containing within some of the most

pilot-friendly aeroplanes ever built. Each member of

the Cherokee family fills its particular niche at least as

well as, and oen better than other aircra of similar

type. However, of all of the many Cherokees the Cherokee 180, sitting as it does right in the middle of the pack

has proven itself to be most popular and justifiably so.

Introduced to the public in 1961, the first Cherokee,

the 150 hp PA-28-150 was immediately well-received

setting the pace for its later siblings who went on to

provide pilots of all levels of experience with honest,

6

A2ASIMULATIONS

:::

CHER OKEE 180 MAN UAL www.a2asimulations.com

dependable and well-performing aircra which are fun

and satisfying to fly, reliable, safe and economical to

own and operate. However, getting to this place took

some time and some very astute business and aeronautical skills and sense.

HIGH FLYING ON HIGH WINGS

Aer a necessary hiatus during World War II the industry

known as “General Aviation” (GA) which encompasses

all privately (as opposed to government and airline)

owned aircra recommenced in a far better economic

environment, the Great Depression not actually having ended until the U.S. entered W.W.II on December 8,

1941. For the first post-war years of the later 40’s, however, it was very slow going in the GA market. The virtually universally held high expectations that droves of exservice pilots would enthusiastically seek to own their

own aeroplanes turned out to be more than somewhat

optimistic.

As the turbulent and violent early 40s and the uncer-

tain, transitory late 40’s passed into history, and aer

Page 7

1961 Piper PA-28-150 Cherokee 150

the first three years of the next decade in which a new,

smaller, but no less vicious conflict in Korea came and

went, a new, thriving American middle class began to

enjoy the substantial positive changes engendered by

the new peacetime culture and economy. As the economic boom of the ‘50s began to improve the lives of

so many, all markets, and no less the GA market, began

to grow and thrive as well. By the end of the ‘50s very

few aircra of the pre-war era were still being manufactured; however, in their place promising, new, exciting,

and for those times revolutionary aeroplanes began to

become available.

But old conventions die hard. In the immediate postwar era and for more than a decade most GA aeroplanes

still had wings which sat up atop of the fuselage (known

as the “high wing” design) as they had in the pre - war

years. The prominent post-war manufacturers of GA

aeroplanes, Piper, Cessna, Taylorcra, Stinson, Aeronca, Luscombe and such all exclusively oered aircra

with high wings and, naturally, that was how the public

pictured all GA aeroplanes, all of which they generally

deemed to be “Piper Cubs”.

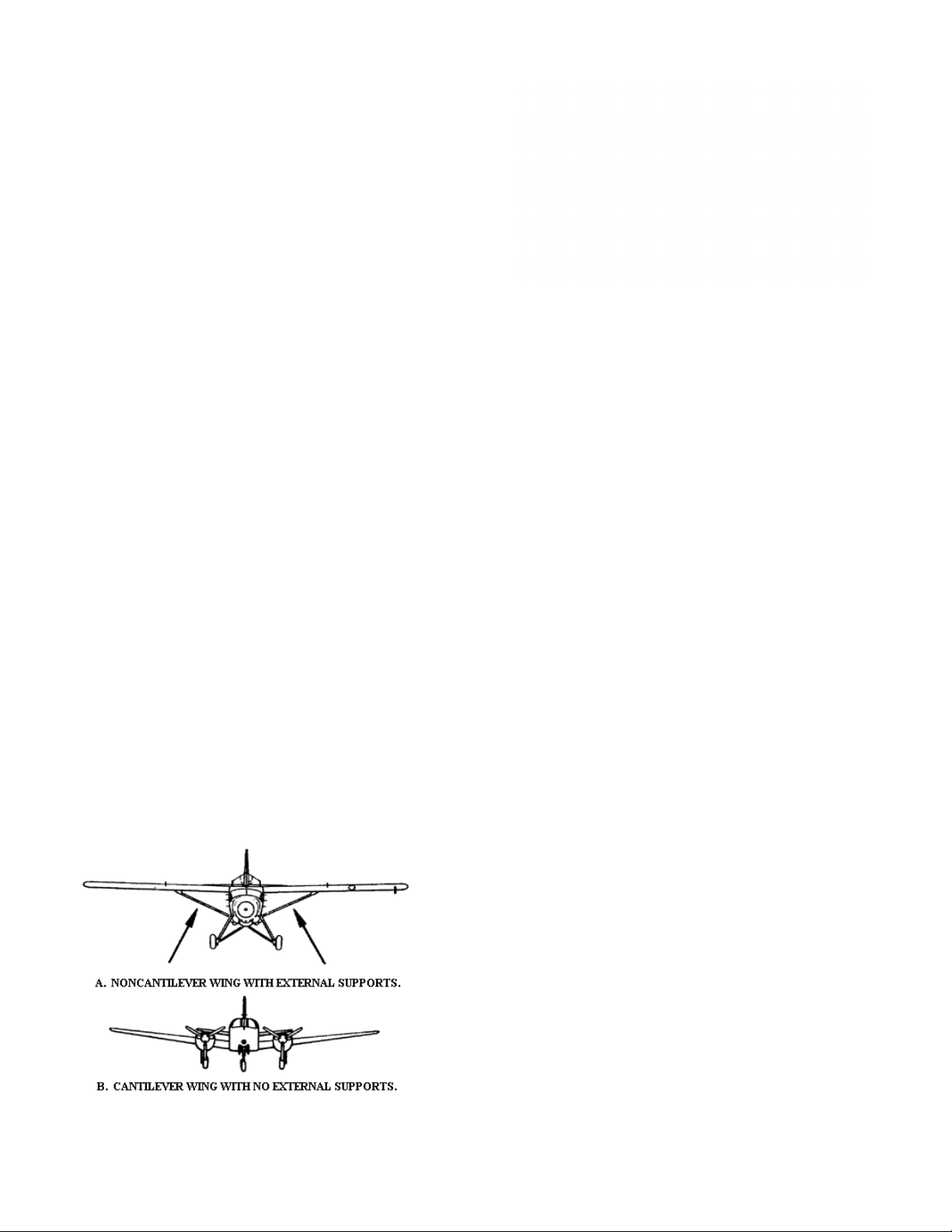

The prolific and successful high-wing design has a

number of virtues: it is easier to design and build a wing

which does not have to support itself (non-cantilever),

but which may be held up with struts attached to the

wings and the bottom of the fuselage. The high- wing

A real Piper J-3 “Cub”

1948 Stinson 108-2

1947 Luscombe 8a Silvaire

1948 Taylorcraft BC-12d

1950 Aeronca 7AC Champ

www.a2asimulations.com CHERO KEE 180 MAN UAL

:::

A2ASIMULATIONS

7

Page 8

AN AEROPLANE FOR THE REST OF US

Left: 1947 Cessna

190 showing

an unusual

cantilever

high wing

design was also the choice of most GA aircra manufacturers because a strut- braced wing is economical to

build being that it is lighter, thinner, and requires fewer

parts than a cantilever wing. Except for aeroplanes like

the Cessna 190/195 models, the Helio Courier STOL

(short take-o and landing), and the Dornier Do. 27/28,

high-wing aeroplanes of the 50’s were virtually all strut

braced.

Of course, the struts themselves add back some the

weight savings of a non-cantilever high wing and additionally impose a drag penalty which the cantilever wing

design, requiring no support struts, does not. However,

while more aerodynamically clean, the weight penalty

of the heavier and bulkier cantilever wing may be as

great a detriment in its way to overall aircra performance as is the drag coeicient produced by wing support struts. Properly designed, a wing strut’s production of drag may be minimised. Aside from economical

concerns, another of the virtues of a high-wing design is

that the pilot’s and passengers’ are granted an almost

unobstructed view of the ground during flight. In addition, for purposes of visual navigational orientation as

well as for sightseeing, a high wing gives good service.

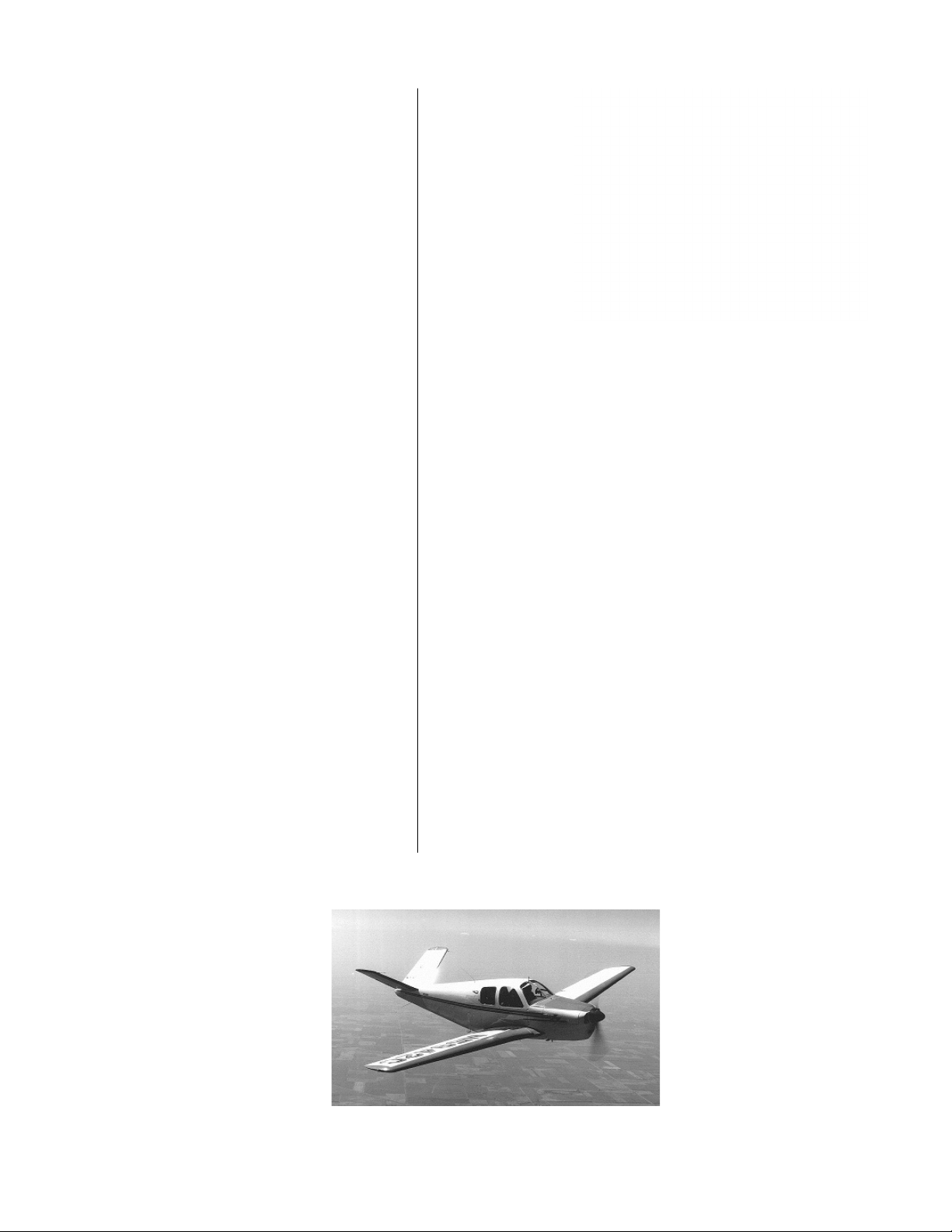

Today, and since the introduction of the Cherokee

series of aircra in 1961, Piper Aircra has come to be

known as a manufacturer of mostly low- wing GA aeroplanes, the PA-18-150 Super Cub being the lone exception. However, for 24 years, from its founding in 1930,

when businessman and oil speculator William T. Piper

purchased the assets of the bankrupt Taylor Aircra

Company for $761.00, except for a small number of

interesting Piper low-wing prototypes along the way

(PT-1 Trainer-1942, PA-7 Skycoupe-1944, PA-6 Skysedan-1945, and PA-8 Skycycle-1945, none of which went

into production), Piper Aviation had exclusively produced high- wing aircra until the twin-engine PA-23

Apache in 1954. The Taylor/Piper Cub and its progeny,

the PA-15/17 Vagabond, the PA-16 Clipper, PA-18 Super

Cub and the PA-20 Pacer with its variants including the

revolutionary tricycle- undercarriage PA-22 Tri-Pacer

were all high- wing, fabric- covered aeroplanes. The PA22 Tri-Pacer which was introduced to the public as early

as February 1951 predated Cessna’s first tri-gear singles,

the 172 and 182 by five years.

Typical wing struts

1960 Piper Pa-18-150 Super Cub 1954 Piper PA- 23-150 Apache

8

A2ASIMULATIONS

:::

CHER OKEE 180 MAN UAL www.a2asimulations.com

Piper Pa-22-150 Tri-Pacer

Page 9

THE BONANZA BONANZA

Of course, amongst all of this GA high-wing high-jinx

there were a few exceptions with one very strong standout, the remarkably prescient Beechcra Bonanza

Model 35, designed in 1945 and introduced in 1947. Well

named, this aeroplane was a remarkable economic success for Beechcra, the first GA success story of the immediate post-war times. In fact, it was the enormously

positive response to the Bonanza in 1947 that fuelled

many GA aircra manufacturer’s starry-eyed optimism

and belief in the sales boom that never happened.

Designed by Ralph Harmon and his associates in

1945 as the war was coming to an end, Bonanza Model

35 had its first test flight on December 22, 1945. Incorporating what was then known of aerodynamics, aviation

technology and modern manufacturing techniques, its

clean, stressed skin (monocoque) all-metal structure

was reminiscent of the recently lionised Spitfires and

Mustangs and in many ways was a distinct departure

from previous GA aircra. With a retractable undercarriage, V-tail, seats for four adults, constant speed propeller and powered by a simple to manage and inexpensive to run six-cylinder, horizontally opposed, air cooled

165 hp Continental 0-470- E165 engine, it was the first

of a new breed.

In its class and for its time the Bonanza was the

epitome of aeronautical design and engineering — fast,

sturdy, and looking like nothing that had come before.

Sure, it was pricey at the then great sum of $7,975.00

($7,975.00 in 1947 had the same buying power as

$85,165.95 in 2013, annual inflation over this period

being 3.65%), but to its purchasers it was worth every

dime. Upon its introduction, corporations, businesses

and wealthy professionals placed almost 1,500 orders in

advance of its release making the Bonanza an unqualified and immediate roaring success.

While Cessna and many other manufacturers

seemed to be still tied to old, pre-war designs and concepts, Beechcra’s Bonanza was an entirely new breed,

a leap forward that looked like and in every way was

“the very model of a modern” aeroplane. Throughout

the 50’s the Bonanza’s sales continued to soar and its

place at the top of the food chain remained essentially

unchallenged.

1947 Beechcraft

Bonanza Model 35

instrument panel with

50’s style non- “T”

instrument layout and

early classic Narco

“Omnirange” VOR

receiver as almost an

afterthought. Note- no

ILS equipment and

30’s-40’s throwback

throw-over yoke system,

toe brakes only on left

rudder pedals.

Continental 0-470

1947 Beechcraft

Bonanza Model

35 3-view

1947 Beechcraft Bonanza Model 35

www.a2asimulations.com CHERO KEE 180 MAN UAL

:::

A2ASIMULATIONS

9

Page 10

AN AEROPLANE FOR THE REST OF US

1958 Piper PA-24-250 Comanche with one piece windshield and aftermarket spinner

THE BONANZA KILLER

Most painfully cognizant of the Beechcra Bonanza’s

well-deserved success, by the end of the 1950s Piper

Aviation was anxious to produce its own modern, all

metal, retractable undercarriage, high performance single-engine aeroplane. Seeking to enter and to dominate

the high-performance GA business aeroplane market

and unseat the Bonanza, Piper Aviation made ready to

topple the King and to take its place on the GA high- performance throne.

To this end, Piper designed and developed the PA-24

Comanche, “The Bonanza Killer”. Piper Aircra’s ambitious intent was to not only put an end to the Bonanza’s

long- held high-performance single- engine commercial

reign, but to put Piper firmly on the map as GAs leading

and most advanced aircra manufacturer. Piper knew

that to do all of this would require an exceptional aeroplane, one that performed to the highest standards,

was fast, comfortable and safe. Of all, this last requirement was key.

Piper Aviation has traditionally leaned heavily towards flight safety in its designs. Gentle and predicable

stall characteristics, inter-connected rudder and ailerons to prevent inadvertent spins on some models,

slow landing speeds and the like had been regularly

and scrupulously designed into Piper aircra from the

beginning. Accordingly, by the mid 1950s Piper had not

been historically known for producing fast, all-metal,

high-performance aircra; but all that was going to dramatically change before the decade was out.

TAKING THE LOW (WING) ROAD

TO SLAY THE KING

William T. Piper knew that in seeking to enter the highperformance, single-engine business aeroplane market

and challenging the iconic Bonanza that he was he was

taking on a very tough, commercially risky task.

By January 1958 the first Piper PA-24-180-Comanche

was delivered to the public. Its cruising speed at 75%

1960 Piper PA-24-250 Comanche instrument panel with 50’s style

non- “T” instrument layout. As in contemporary Bonanza, radios

seem to be almost an afterthought. Note- modern-style VOR but

no ILS equipment, dual controls but toe brakes on only left rudder

pedals, large ap handle but no Johnson bar brake handle.

1964 Piper PA-24250 Comanche with

unpainted spinner,

aftermarket onepiece windshield

and tip-tanks

1967 Piper PA-24250 Comanche with

3-blade propeller,

aftermarket

spinner, onepiece windshield

and tip-tanks

1959 Piper PA24-250 Comanche

Note- tail low

ground stance,

large nose wheel

and short main

undercarriage legs.

10

A2ASIMULATIONS

:::

CHER OKEE 180 MAN UAL www.a2asimulations.com

Page 11

at 8,000’ is 139 knots (159.85 mph) which in its day was

excellent for a four-seat, 180 hp aeroplane, but not quite

fast enough to seriously compete with the 165 knot

(189.75 mph) 240 hp Bonanza 35H at 75% power.

The first low-wing GA aeroplane produced in over a

decade, the Comanche was something new and exciting. A breathtakingly beautiful design, its novel sweptback tail, its gracefully tapering wings and sleek fuselage gave it the look of innovative modernity in the

same way that Lancaire and the Cirrus aircra appear

to us today.

Accordingly, Piper began to immediately test the

installation of a 250 hp Lycoming O-540 engine in the

Comanche. The PA-24-250, introduced in April 1958 has

a very competitive 75% cruise speed at 8,000’ of 160

knots (184 mph).

So, did the Comanche actually kill the Bonanza?

Well, the answer is clearly, no. However, it did compete

well with it and better in that regard than anything else

in its time. Piper and Beechcra continued to strive

with each other until the Comanche suddenly ceased

production in 1972, along with the excellent, sleek and

speedy Twin-Comanche, as a result of catastrophic

damage to Piper’s Lock Haven, PA factory caused by

the record rising of the nearby Susquehanna River due

to Hurricane Agnes. Today, as newer and even sleeker

modern composite designs vie with it for top dog in the

GA high-performance, single- engine market the Bonanza lives on, albeit in the shape (if not the name) of

the venerable, conventional tail Debonaire, and is still

in production with no end in sight.

While its time in the market as a new aeroplane

was relatively short (1958-72), since its introduction

the Piper Comanche has been and still is one the most

highly- respected and desirable GA aeroplanes. A good

one in good condition is considered a prime find on the

used aircra market. Today there are many thousands

of loyal Comanche adherents who firmly believe, and

with good reason, that it is the most beautiful, elegant

and overall best performing single-engine GA aeroplane

ever built. Right, Scott?

Second test

proto-type of

Piper PA-24-180

Comanche

1958 Beechcraft

Bonanza H35

with tip-tanks

1959 Beechcraft

Bonanza 35J

Lycoming 0-360

Piper PA-24- 250 all original contemporary Beechcraft Bonanza G36Piper PA-30- 160 Twin Comanche - R. I. P.

www.a2asimulations.com CHERO KEE 180 MAN UAL

:::

A2ASIMULATIONS

11

Page 12

AN AEROPLANE FOR THE REST OF US

HOW ABOUT AN AEROPLANE

FOR THE REST OF US?

Without any question, the Bonanza and the Comanche

were and are very high performance single-engine GA air

cra aimed at distinctly well-heeled potential private/corporate owners. However, there also existed a significant

segment of the GA market that wished to own a new, rea

sonably fast (if not the fastest), modern, all-metal, fourseat aeroplane, but who could not aord the Comanche’s

and especially the Bonanza’s high price tag. FBOs (fixedbase operators), flight school operators and flying clubs

were also looking for aircra that they could rent out at

rates that the average weekend private pilot could aord.

As the prosperous second half of the 1950s came to a

close, Piper understood that the time of the fabric- covered Tri-Pacer and Colt had come to its end. Studies within Piper Aviation in the mid- 50’s showed that with modern manufacturing techniques it was actually now more

cost-eective to produce an all-metal aeroplane than to

continue to produce the old school parts and labour- intensive, metal frame, fabric- covered Tri-Pacer and Colt.

Even with plans to build the Comanche already

drawn, the factory tooling up to manufacture it, and

with Piper’s well-founded hopes and expectations that

its new beauty would well-establish Piper Aviation in

the high-performance single-engine, business aeroplane market, William T. Piper knew that if Piper was going to survive and flourish into the next decade and beyond that, further aeronautical invention and progress

was wanted. He, his son Pug and the entire Piper team

knew that they had to produce a new, modern entry to

mid-market level aeroplane as soon as possible in order

to compete with Piper’s true rival, the only other major

aircra company that was actively and successfully servicing that segment of the GA market, Cessna.

Immediately upon the introduction of the all- metal

Cessna 172 in 1956 Piper knew that its internal evaluations regarding the obsolescence of fabric-covered aircra were indeed valid and that their then single-engine

star, the Tri-Pacer, had already been eclipsed. While the

exceptional Comanche had, in fact, turned out to be

highly competitive in the high-end GA niche, giving the

equally exceptional Beechcra Bonanza a good run for

the money, Piper well understood that in order to compete in and command a viable position in the entry/

middle price market it needed to oer something new,

-

-

Rib- stitching a

fabric covered

Tri-Pacer’s

wing before

doping —

one of this

process’s

many labourintensive steps.

something that would give potential owners an attractive alternative to Cessna’s popular 172.

Looking to produce a four-seat design which would

be simpler and which could be produced less expensively than the complex, retractable gear, constant- speed

propeller Comanche, Piper also knew that in order to be

competitive in the lucrative trainer market they needed

to build a replacement for the two- seat Colt which had

been commercially greatly overtaken by the all metal

Cessna 150. If these two needs could be resolved by one

overall design, so much the better.

A product of the prosperity and economic confidence

of the late ‘50’s in the United States was a wave of new

student pilots. Flight schools and clubs were popping

up at virtually every local airport and business was very

brisk. Since its introduction in 1958, the all-metal, twoseat Cessna 150 had become by far the most popular

aircra in this burgeoning trainer market. As the last of

the J-3’s, Aeronca Champs and other similar tail-wheel

(then called “conventional undercarriage”) aircra

began to disappear from attrition mostly due to tailwheel induced taxiing and landing accidents, they were

quickly being replaced by the tricycle undercarriage 100

hp Cessna 150 and, to Piper’s disappointment, to a far

lesser extent the 108 hp, two seat version of the old TriPacer, the fabric- covered Piper Colt. It was understood

that the old tail- wheel trainers did not oer as relevant

a training experience to student pilots who looked for-

12

1961 Cessna 172

A2ASIMULATIONS

1959 Cessna 150

1960 Piper PA-22-108 Colt

:::

CHER OKEE 180 MAN UAL www.a2asimulations.com

Page 13

1956 Cessna 172

1956 Cessna 172 interior

ward to soon flying higher performance aircra, all of

which had tricycle undercarriages.

Also, unlike the J-3, etc. where the student and instructor sit in tandem, in the new trainers the instructor and

student sit side- by- side, facilitating communication as

well as increasing the confidence of the student and mak

ing it easier for the instructor to demonstrate maneouvers

and to teach the lesson. Additionally, and most signifi

cantly for FBOs, flight schools and clubs, with the advent

of these new tricycle- undercarriage trainers, ground

loops and nose overs whilst landing as well as collisions

whilst taxiing became a thing of the un- mourned for past.

The Tri-Pacer shared the same market as Cessna’s

172; however, except that they were both high-wing,

four place aeroplanes of similar power, they actually

shared few similarities, particularly with regard to construction and appearance.

Firstly, the Tri-Pacer was fabric covered whilst the

172 was all metal. The higher maintenance cost of a

fabric covering as well as the anticipated expense of an

inevitable fabric re-covering was a strong market motivator toward the all- metal l72.

Secondly, the Tri-Pacer’s frame has many steel components within which can and do rust, and eventually cause

major repair headaches. The 172’s stressed-skin covered

airframe is sturdy, low- maintenance and is all aluminium.

Thirdly, the Tri-Pacer, which had been introduced

in 1951 was distinctly showing its age and was, in fact,

something of an anachronism by the beginning of the

following decade. Its foreshortened appearance gave it

a somewhat stodgy look and sitting seemingly precariously upon its closely spaced undercarriage, it garnered

the unfortunate nickname “Flying Milk Stool”. Piper

-

had to face it; the Tri-Pacer just didn’t imply a clear and

definite sense of modernity as surely as the Cessna 172.

-

Taking everything into consideration, Piper saw the

writing on the wall.

Ironically, the Tri-Pacer’s performance is excellent,

competing well with and in some instances beating the

newer Cessna 172. The 160 hp Tri-Pacer climbs at approximately 800 fpm loaded at or near MGW with a top speed

of 123 k (141.5 mph) and a 75% cruise of 117k (134.5 mph)

at 7,500’. Its useful load is 890 lbs., and its take-o and

landing performance as well as its slow and departed

flight performance is overall better than the 172’s. The

Tri-Pacer is more responsive than the Cessna 172 and

many pilots have found it to be more fun to fly. Nevertheless, by the end of the 1950’s the more modern-looking

Cessna 172 was running away with the middle GA market.

Before 1961 one might well be excused for thinking

that with the exception of the low-wing twin-engine

Apache, the Comanche and the Pawnee crop-duster

that Piper leaned heavily towards the production of

high-wing aeroplanes. Aer three decades and thousands of fabric-covered, high- wing Pipers this trend

changed dramatically, marking the end of one era and

1959 Piper PA22-150 Tri-Pacer

www.a2asimulations.com CHERO KEE 180 MAN UAL

1967 Cessna 172/Skyhawk

1960 Piper PA-25-235

Pawnee crop duster

:::

A2ASIMULATIONS

13

Page 14

AN AEROPLANE FOR THE REST OF US

Left: Fred Weick’s

brilliant and

innovative 1936

Erco 315CD

“Ercoupe”

Center: Very

rare photograph

of experimental

retractable

Ercoupe

Right: Fred

Weick with his

Ercoupe Noteconstant speed

propeller with

anti- icing boots

the beginning of a new one when the first of the all metal low-wing PA-28-150 and PA-28-160 Cherokees were

introduced to replace the Tri-Pacer and the Colt which

were then withdrawn from production.

CREATING AN AFFORDABLE LEGEND

In 1957, Karl Bergey, Assistant Chief Engineer at Piper’s

brand new Vero Beach facility which was built to design,

test and ultimately manufacture the Cherokee, led the

team of engineers and designers whose task it was to

create an aeroplane that would establish the new, modern Piper Aviation in the present and secure it well into

the future. Pug Piper sought to create a small team of

engineer/designers who had reputations for having the

foresight and imagination to create something new. To

that end, Pug Piper’s friend, the talented, progressive

and imaginative 1928 Collier Trophy winner, Fred Weick

was invited to join the team.

Weick was one of the first American aeronautical engineers who had, among other things, worked closely with

the United States Postal Service in the early 1920s to establish and to develop the U.S. Air Mail Service. In 1925,

whilst an engineer working for the National Advisory

Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), Weick was the chief

design engineer and responsible for developing streamlined cowlings to improve aerodynamic eiciency while

enhancing engine temperature control. He also helped to

design the first full-scale propeller wind tunnel.

By 1936, as chief designer at ERCO, Mr. Weick designed the revolutionary ERCO 310, better known as the

“Ercoupe”, designed to be virtually stall and spin-proof

with integrated rudder and aileron controls (no rudder

pedals), a crosswind resistant undercarriage, and one of

the first aeroplanes designed with a tricycle undercarriage.

Both William Piper and his son, Pug greatly admired

the extraordinary talents of the brilliant and prolific

aeronautical engineer/designer John W. Thorp who

agreed to join the team. In the course of creating the

Cherokee this stellar design team found Thorpe’s keen

aeronautical mind to be a great and powerful resource.

The design of the Cherokee ultimately greatly benefited

from many of John Thope’s ideas and from his excellent

past designs. In particular, the team incorporated many

features from Thorp’s amazingly ahead of its time, the

1945 all- metal T-211.

A MOST DELICIOUS WING

The first thing that Pug Piper told his team was that the

new aeroplane would have a low wing for a new Piper

look and so that drag producing struts of any kind could

be avoided. He wanted Piper Aviation to build on the

excellent reputation that the low-wing Comanche had

already established and envisioned an aeroplane that

would look and be as entirely dierent from the Cessna

172 as possible.

John W. Thorp

14

A2ASIMULATIONS

1945(!) Thorp “Skyshooter” T211 showing the true

genesis of the Cherokee design. Note the Hershey

Bar wing, undercarriage conguration, corrugated

skin rudder and the stabilator with anti-servo tab.

:::

CHER OKEE 180 MAN UAL www.a2asimulations.com

Page 15

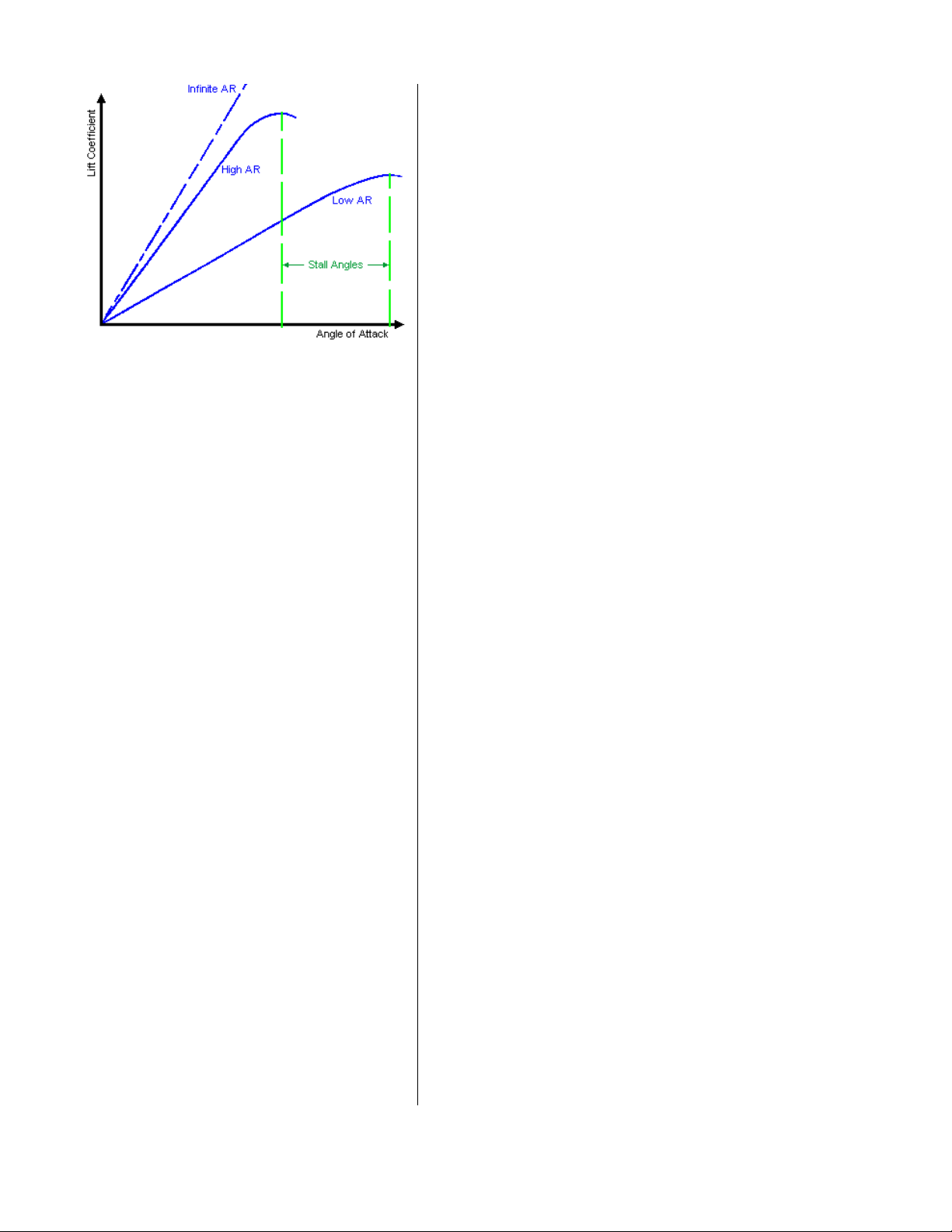

An all metal, cantilever 160 sq. . (15.14 m), 30’ (9.2

m) span, 5’ 3” (1.6m) constant-chord (non-tapering)

wing, popularly called the “Hershey Bar” wing because

of its similarity in shape to that most famous rectangular confection, became the basic platform upon which

this new aeroplane was built. This wing’s aspect ratio

(span divided by chord) is on the low side at 5.63. This

was not a problem or a new situation at Piper. The immediate predecessors of the Cherokee, the so- called

“short wing” Pipers, the Vagabond, the Clipper, the Pacer, the Tri-Pacer and the Colt which the Cherokee series

of aircra was to replace had even lower aspect ratios.

By comparison Cessna 172’s aspect ratio was 7.448.

It was a deliberate design choice to raise the new

Cherokee’s wing’s aspect ratio a bit from the shortwinged Pipers in order to increase its Cl (coeicient of li)

and thereby its eiciency. Up to a point, a higher aspect

ratio wing promotes better high altitude cruise, climb

and glide performance. However, a wing with a lower aspect ratio has at least one advantage — it has a higher

critical angle of attack (Alpha), i.e., the positive Alpha

at which it will stall; additionally the stall itself tends to

be gentle. The old short-wing Pipers were not very eicient power-o gliders (I recall that the Colt, particularly,

glided like a stone); however, they were extremely forgiving at low airspeeds and in extreme departed flight attitudes. They could, with suicient power applied, seem to

“hang on their propellers” with their noses sitting way up

in the air whilst flying at very low airspeeds. It had been

Fred Weick’s lifelong goal to build aeroplanes such as the

Ercoupe that were easy to fly and by extension, safe. All

agreed that forgiving flight characteristics would be a

most attractive feature to the low-time pilots and FBOs

that were Pipers commercial target.

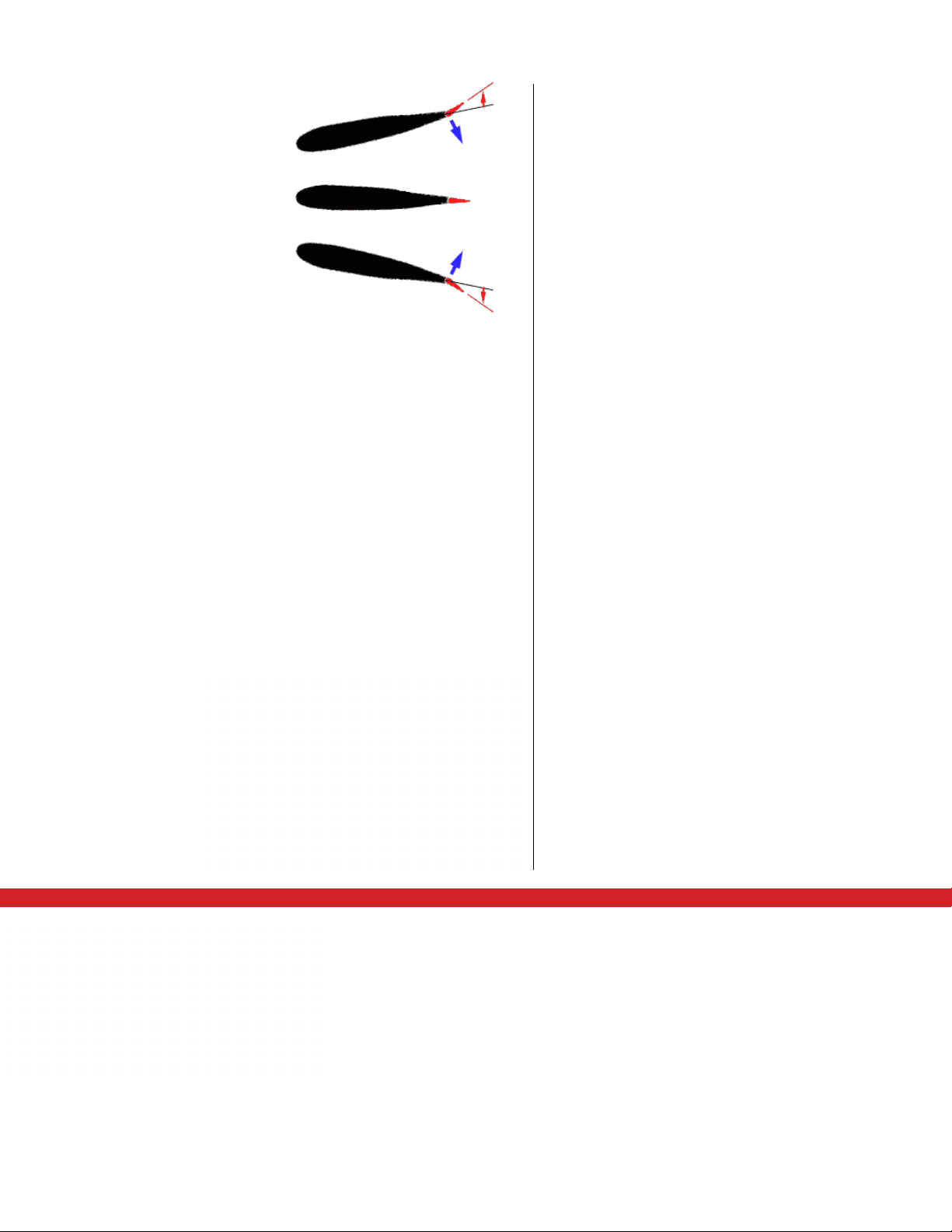

The team designed the Cherokee’s wing to be

mounted at an angle of +2º to the fuselage’s longitudinal datum line in order to permit a distinctly nose-down

attitude, thus promoting good forward visibility for the

aeroplane’s occupants on the ground and in flight, and

Aspect Ratio - wing

span (tip to tip) divided

by average chord

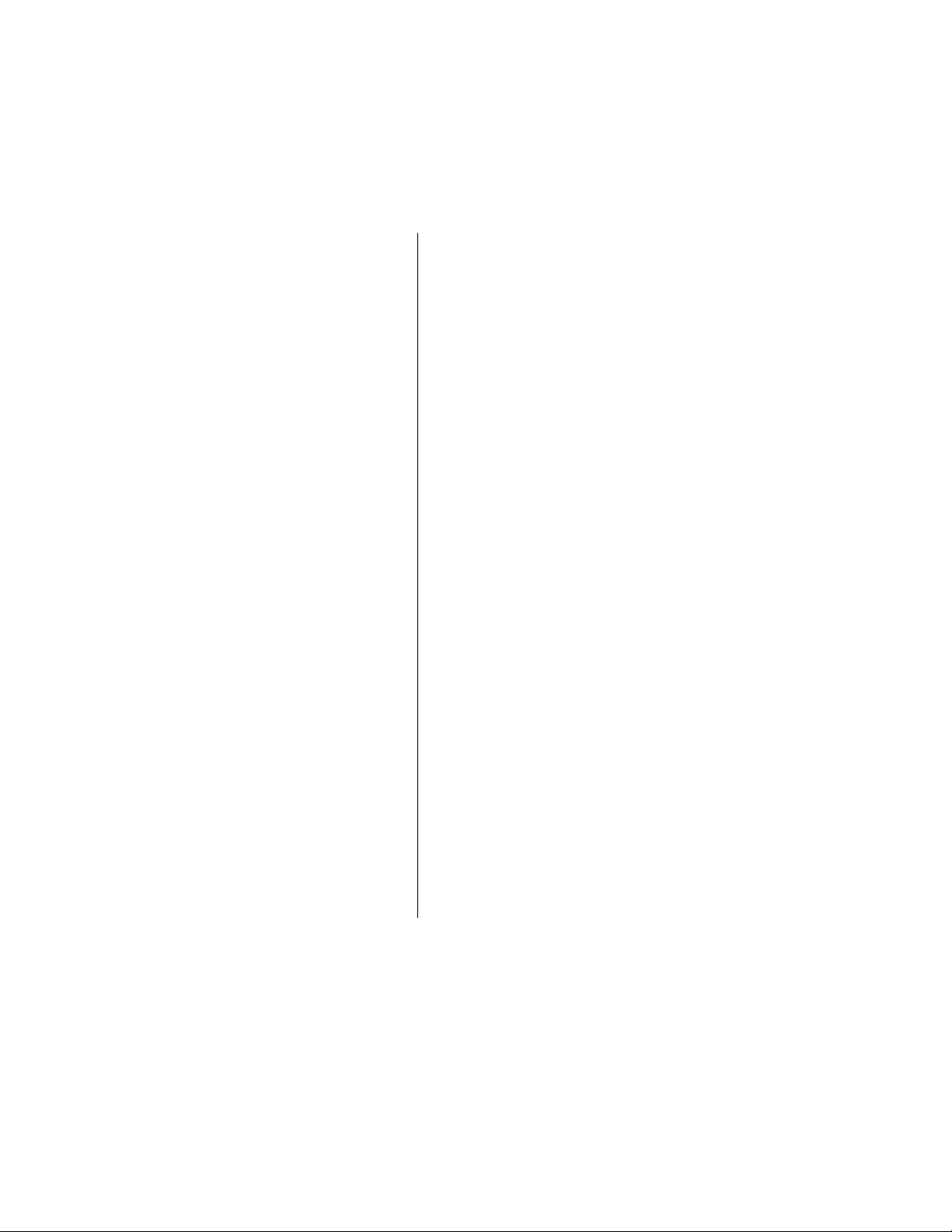

reducing P-eect (combination of twisting slipstream*

and induced propeller yaw in the opposite direction of

the turning of the propeller when at positive Alpha) during the takeo run. They wanted to improve upon the

Comanche’s distinctly nose-high stance on the ground

which creates a good deal of P-eect on takeo requiring lots of right rudder to keep it on the centreline.

*For what it’s worth, this writer does not hold very

much with the theory of a twisting slipstream as a major

P-eect force for a number of reasons to lengthy to go

into here. Also, remember, P-eect operates in the yaw

axis, torque in the roll axis.

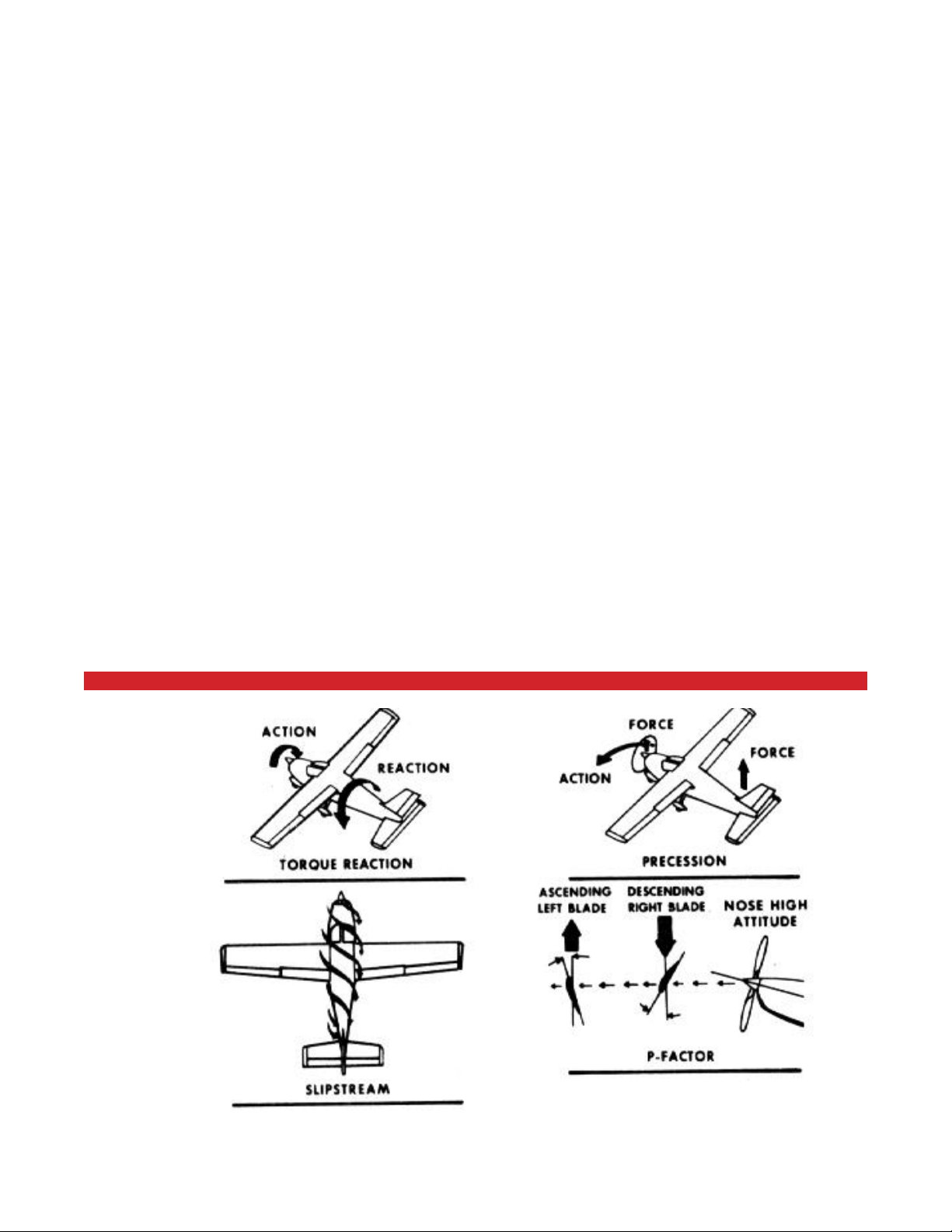

Being a low-wing aeroplane, the Cherokee’s overall

vertical centre of gravity (C.G. v) is low, however, it is

necessarily at a point above its low wing. This promotes

poor stability in the lateral (roll) axis while enhancing

maneouverability. While enhanced maneouverability is a good thing in a fighter, aerobatic show or sport

aeroplane, it is not necessarily so good in an aeroplane

Left to right:

1) Piper PA-16

Clipper

2) Piper PA- 17

Vagabond

3) Piper PA-22

Pacer (Tri-Pacer

in red above)

4)1964 Piper

PA-28-140

showing original

“Hershey Bar”

rectangular wing

www.a2asimulations.com CHERO KEE 180 MAN UAL

:::

A2ASIMULATIONS

15

Page 16

AN AEROPLANE FOR THE REST OF US

Angle of Attack (AOA) also called “Alpha”

16

A2ASIMULATIONS

P (propeller) -Effect

:::

CHER OKEE 180 MAN UAL www.a2asimulations.com

Page 17

Hershey Bar Cherokee showing 7 degrees of dihedral

Cessna 172 showing 3.5 degrees dihedral

designed to be used for training new pilots and for comfortable and easy touring. To create good lateral stability a low- wing aeroplane requires dihedral, more dihedral than is required for a high wing aeroplane. Also, a

low wing aeroplane requires greater dihedral to provide

for adequate wingtip clearance when on the ground

and when a wing may be lowered during a cross-wind

landing. Accordingly, the Cherokee’s low wing has 7º of

dihedral which gives it very good lateral stability which

is especially welcome on long trips and when in mildly

turbulent conditions.

The vertical centre of gravity (C.G. v) of a high-wing

aeroplane is also low, but at a point below the wing

which promotes good stability in the lateral axis. This

means that less dihedral is required for high-wing aeroplanes. Accordingly, the high wing Cessna 172’s dihedral

is only 3.5º.

Dihedral causes a self-levelling force to occur when

the aeroplane is displaced from level in the roll axis. As

any force, such as turbulence, begins to roll an aeroplane from level, the downward moving wing’s Alpha

increases, creating li. In addition, the lowered wing assumes a more horizontal attitude than the higher wing

and, concurrently, the lower wing creates more li because of this, as well. Both of these eects tend to roll

the aeroplane back towards level.

Of course, too much dihedral can lead to a reduced

roll rate as well as over-sensitivity in turbulence, making for an uncomfortable ride in all but the calmest air.

Compensating for its generous dihedral, the rectangular wing Cherokee’s large and most eective ailerons

produce a rapid roll rate which is faster than that of

most GA aeroplanes. This is due in part to the reduced

lateral damping eect of the low aspect- ratio, slightly

foreshortened Hershey Bar wing. The Cessna 172’s

wingspan is 6’ greater than that of the rectangular wing

Cherokee and, accordingly, it creates more lateral axis

damping which somewhat reduces its roll rate. Accord-

www.a2asimulations.com CHERO KEE 180 MAN UAL

:::

A2ASIMULATIONS

17

Page 18

AN AEROPLANE FOR THE REST OF US

ingly, the Cherokee is maneouverable, laterally stable

and rides quite well in all kinds of turbulent air. Accordingly, it seems that the Cherokee’s wing’s dihedral, like

so much else about this aeroplane, appears to be just

right.

Adverse yaw is the tendency for an aeroplane’s nose

to yaw in the opposite direction of bank and is caused

by the rising wing pulling back because of increased

induced drag created by li. To reduce adverse yaw,

virtually all modern aeroplanes, including the Cherokee, have ailerons which are dierentially rigged; that

is, there is more upward aileron movement than down,

causing there to be less li- induced drag in the rising

wing and thereby reducing its tendency to yaw the aeroplane away from the turn.

To simplify the Cherokee’s construction and to keep

costs to a minimum, a few new wing mounting techniques were incorporated. As mentioned, the Comanche’s le and right wings are joined in the middle in the

factory making the wing one piece. The entire wing is

then attached to the bottom of the fuselage, the main

spar being bolted to a receiving 3-sided box. This construction makes for a very strong +7g wing, perhaps

stronger than necessary in a non-aerobatic GA aeroplane. It is also quite costly. Piper’s team looked for another way to mount the wing to the fuselage that would

be strong enough but also simple and economical.

What they came up with is this: The Cherokee’s wings

are attached individually to each side of the fuselage.

Each of the Cherokee’s wings’ main spar is in the form of

an “I” beam which is inserted into to a box beam built as

a part of the fuselage frame located under the rear passenger’s seat, spanning the width of the fuselage. Once

the wings’ spars are seated within the box beam they

are secured with eight heavy bolts essentially making

the wing one piece. The inner ends of the forward and

a wing sub- spars are bolted to the fuselage through

matching mounting plates in the wing root and on the

fuselage. This greatly simplifies assembly as well as

making major wing repairs or replacement less expensive. An additional plus is that this method of mounting

the wings separately permits the use of a much shorter

shipping crate, thus saving transportation costs of the

unassembled airframe.

Piper reports that it has thoroughly tested the Cherokee’s wing mounting system, running at least 480,000

load and unload cycles with no damage to the wing

mounts.

The Cherokee’s constant-chord, rectangular wing

planform did not, however, come about without some

friction and dissent within the design team. “Pug” Piper

wanted tapered wings as on the Comanche, both for

aesthetic and aerodynamic reasons. Both Thorp and

Bergey also initially thought that a tapered wing for

the new aeroplane would be best even though Thorp,

in particular, had been a long-time, outspoken advocate of non-tapered wings for GA aircra (see the Thorp

T-112).

Supermarine

Spitres showing

elliptical wings

18

A2ASIMULATIONS

:::

CHER OKEE 180 MAN UAL www.a2asimulations.com

Page 19

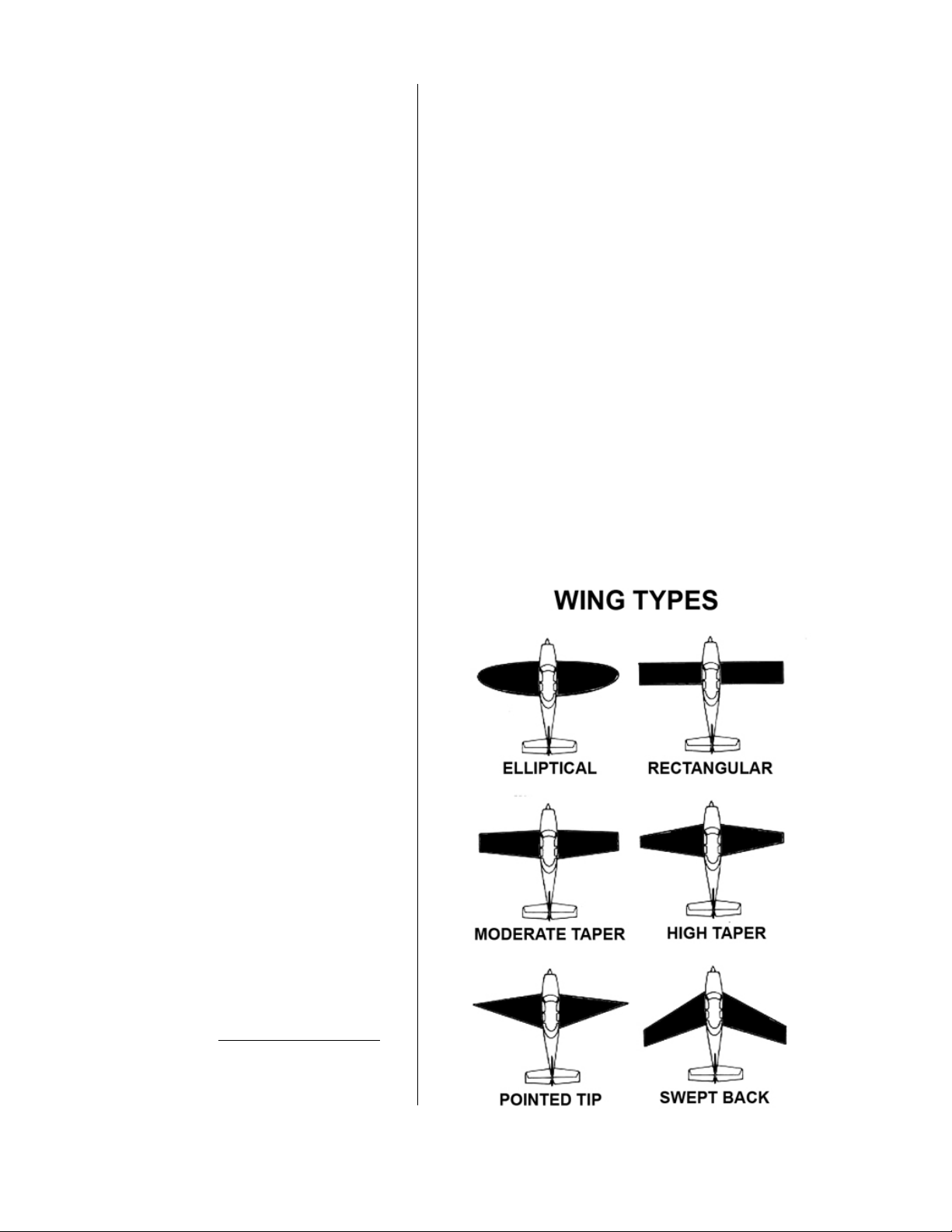

The team considered a tapered wing for three basic

reasons:

At first, Karl Bergey was, as was his boss, Pug Piper,

in favour of a tapered wing for the new design which he

said more closely emulated the commonly accepted

ideal wing plan form, the ellipse, as found on R. J. Mitchell’s spectacular and beautiful Supermarine Spitfire.

Piper, Bergey and Thorp initially agreed that an elliptical wing produces less overall li-induced drag than a

rectangular wing and is quite eicient.

The second argument for a tapered wing was that

since the tapered outer part of the wing has a shorter

chord it has less overall area than the inner part of the

wing. This reduced wing area would cause less upward

bending pressure on the root of the wing when in flight

than if it the chord was constant to the tip. With less

bending to worry about, a simpler, lighter inner wing

structure could be designed.

The third and perhaps the most practical reason for

a tapered wing (from a marketing perspective at least)

was that they look sleek and aerodynamically “correct”.

Always most aware of the importance of marketing with

regard to of any commercial product, Pug Piper, as had

his father so many times before him, found this argument to be highly persuasive.

It looked like the Cherokee was going to have a tapered wing similar to the Comanche’s when Thorp began to advocate for a rectangular wing instead. Aer

ruminating about the issue for a while and he began to

discount the structural argument for a tapered wing. He

reasoned that the dierence in the structural weight of

a tapered verses rectangular wing of the same size was

too small to consider. Combining this with his aerodynamic analysis he said that aerodynamic scale eect

makes it possible to use a smaller rectangular wing

(rather than a larger tapered wing) for a given stalling

speed. He went on to explain that therefore the tapered

wing, though possibly inherently slightly lighter, must

ultimately be of greater span in order to provide equal

wing area to that of the un-tapered wing, thereby erasing any weight saving.

As to the elliptical wing planform theory, Thorp rejoined Piper and Bergey’s opinions and held that there

was more to the issue than that so- called “ideal”.

He argued that while the total of aerodynamic forces

indeed seemed to favour an elliptical wing form, where

the wing’s chord was shorter near and at the tip of such

a wing, or in any tapered wing seeking to emulate an

elliptical form, the Reynolds Number (RN)* is similarly

lower near and at the wing tip, therefore causing a great

propensity for the wing tip to stall before the rest of the

wing.

Reynolds Number =

V(speed) x L (length of chord)

Kv (kinematic viscosity)

“stickiness” of the air. For simplicity you can use the

value 6327 for the Kv of air at the standard temperature

of 59 degrees Fahrenheit at Sea Level. The speed value

is in feet per second and the length is the chord of the

wing in linear feet.

The Reynolds Number is an essential measurement

of wing/aircra performance and if you are a serious

student of aerodynamics you will want to know a good

deal about it.

The others recognized Thorp’s argument to be sound

because, as is well-known, where the RN is lower the

maximum Cl is necessarily lower, creating less li at

any given airspeed as compared to any other part of the

wing where the chord is longer. Accordingly, it follows

that where the maximum Cl is smaller, that part of the

wing must stall first.

Thorp further argued that the relatively small size

of GA aircra’s wings and their relatively slow takeo

and landing speeds exacerbates the tip stall problem

in a tapered or elliptical wing as the outer wing’s RN is

therefore even lower. Additionally, a tapered or elliptical wing is more readily likely to have reduced aileron

eectiveness. While it makes sense that the aileron on

a tapered wing may be less eective being mounted

at the tapered portion of the wing which has a shorter

chord and thus a lower RN causing lower eiciency and

Without getting too deep into the math of this for-

mula, the kinematic viscosity (Kv) is a measure of the

www.a2asimulations.com CHERO KEE 180 MAN UAL

:::

A2ASIMULATIONS

19

Page 20

AN AEROPLANE FOR THE REST OF US

Some xes

for tip stall

a lower maximum Cl; it is also true that the tapered

wing’s outer section produces less aerodynamic lateral

damping force in a roll than does a constant chord wing.

Therefore, all else being equal, with properly designed

ailerons a tapered wing could have as fast or a faster

rate of roll than a constant chord wing of identical area

and span.

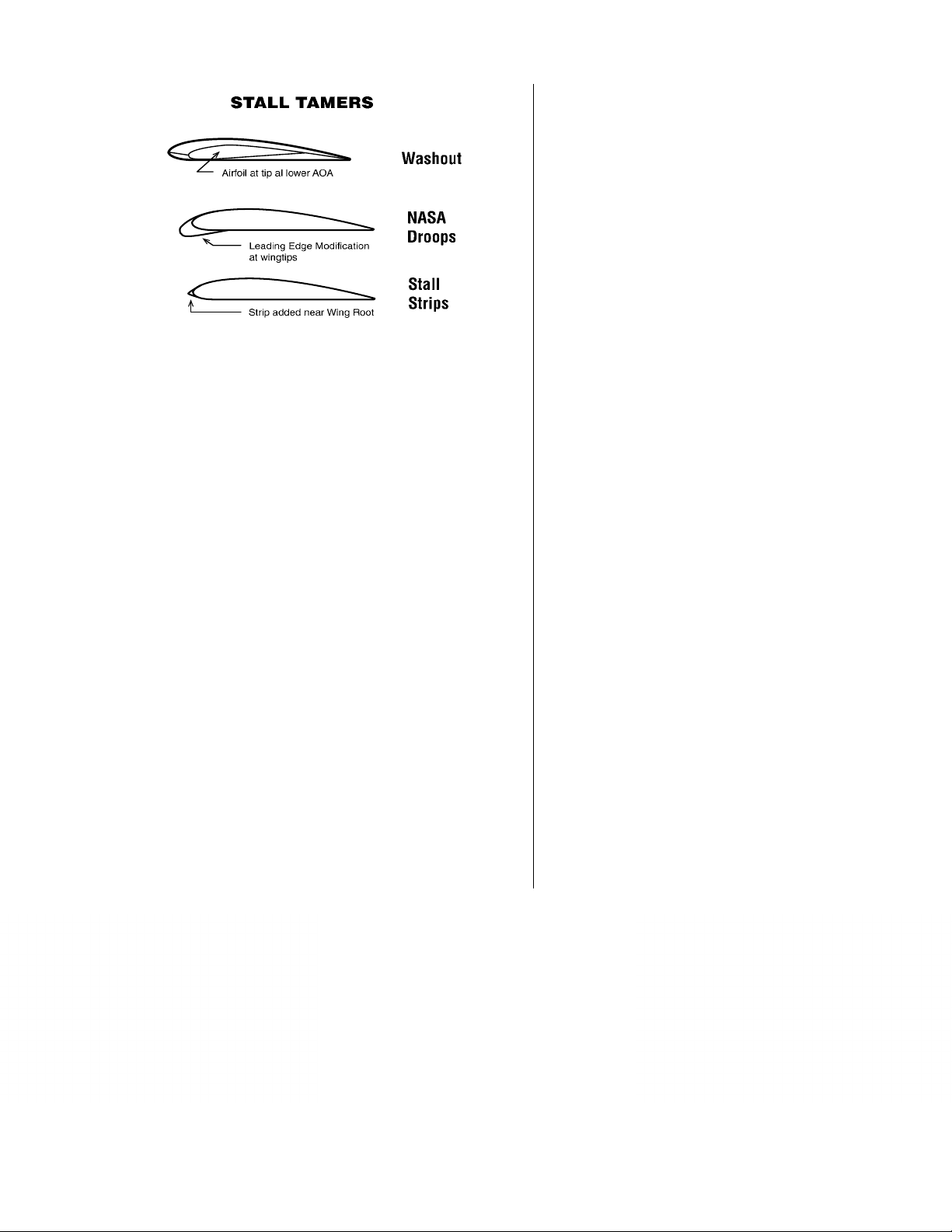

As a tapered wing for the Cherokee was being seriously discussed, the various known “fixes” for tip stall

were considered. The commonest of these is wing twist

or “washout” where the outer portion of the wing’s trailing edge is built to ride slightly higher than the leading

edge (producing lower local static Alpha). Additional

preventative measures for tip stall are aerodynamic devices which are attached and/or added to the wing such

as drooped or enlarged leading edges, stall strip at leading edge, more greatly cambered (curved) outer- wing

airfoil sections, fixed or automatic leading edge slots or

slats, and downward curved wing tips.

While these fixes do help the problem to some degree, they all add complexity, and/or weight to the

wing and all produce additional airspeed- robbing drag

which tends to negate the advantage that the tapered

wing was supposed to deliver in the first place.

In final analysis, Thorp, Bergey and Weick (who ad-

Piper PA-28-161

showing semitapered wing

PA-28-181 Archer

showing semitapered wing

mired Thorp’s sound reasoning on the matter) agreed

that nothing of any value, especially airspeed, would be

gained by incorporating a tapered wing, and admitted

that, in fact, the tapered wing in its pure “unfixed” form

was more prone to tip stalls and spins. They agreed that

a rectangular wing with a few degrees of washout would

be as or more eicient as an elliptical or tapered wing

without any of the tapered wing’s attendant tip-stall

problems and without the complexity and additional

expense of building a more complicated tapered wing

structure.

The team finally agreed upon a rectangular, constant- chord, “Hershey Bar” wing for the Cherokee,

which indeed proved to possess a high degree of cruise

eiciency, near to ideal li distribution characteristics,

and which is highly stable at low airspeeds, near-stall,

stall and departed flight conditions.

Always seeking to improve the Cherokee, in 1969 an

extension of the wing span was proposed in order to improve load carrying ability and rate of climb. However,

preliminary tests showed that a longer wing would necessarily increase positive bending pressure on the wing

root and inboard wing structure requiring an entirely

new and more robust inner wing design which would

necessarily add to manufacturing costs. The idea was

tabled for the time being.

In 1973 Piper revisited the Cherokee’s wing design

and decided to go with the original idea of a tapered

wing. While Thorp and Weick’s original theories regarding tapered vs. rectangular wings were correct and had

been well-proved, much to the dismay of many within

and without Piper Aviation, a new, tapered wing was approved for the PA-28-150.

This aeroplane also incorporated a few other upgrades, improved wing fairing and seals and was renamed the PA-28-151 “Warrior”. Thereaer, if a Piper

aeroplane has a “1” as its last number, as in PA-28-151,

etc. it has a semi-tapered wing. The “Warrior” broke Piper’s tradition which began in 1954 with the twin engine

Apache of exclusively naming its aircra aer the English language names of Native American tribes, and began a new tradition of also naming aircra using words

such as “Tomahawk”, “Arrow”, “Archer”, “Papoose”, etc.

that closely suggested and alluded to that noble culture.

The new PA-28-151 was very similar to the old PA-28150, except for its tapered wing, which is actually only

tapered from the mid - span point to the tip on each side

and therefore ought to more properly be called “semitapered”. The new wing was also increased by 5’ in

span to make up for the decreased area of the tapered

20

A2ASIMULATIONS

:::

CHER OKEE 180 MAN UAL www.a2asimulations.com

Page 21

section, as Thorp had said would be necessary. The increase in span raised this new wing’s aspect ratio to 6.66

from 5.63 and likewise slightly raised its Cl. The product

of the additional span is a slight gain in rate of climb and

high altitude cruise speed and a flatter power-o glide.

Some of these performance gains were initially credited solely to the new semi- tapered wing itself; but

upon closer inspection and analysis it was discovered

that they were at least partially, if not mostly due to the

improved wing/fuselage seals and fairing incorporated

in the PA-28-151. At the same time, the semi-tapered

wing’s increased aspect ratio, which in addition to its

said performance enhancements also reduces the eective range of Alpha at which the Cherokee may fly before

stalling. This causes the semi-taper wing Cherokee’s Alpha at the stall to be lower than that of the Cherokee

with a rectangular wing.

In 1976 the PA-28-180 was re-designed with a semitapered wing becoming the PA-28-181 “Archer”; and by

1979 all Piper single- engine aircra had received semitapered wings, all of them, accordingly, both gaining

and losing therefore as mentioned above.

As far as performance goes between the Cherokee

with a rectangular or semi-taper wing, all else being

equal and without wheel pants, from sea-level to approximately 6,000’ the rectangular wing is actually faster than the semi-tapered wing. However, as altitude increases past 6000’ the rectangular wing loses airspeed

more rapidly. As mentioned, the semi-taper wing Cherokee has a slightly better rate of climb and also a flatter

glide. Flatter glide is good in itself, but has a down side

in that the semi-tapered wing Cherokee is more sensitive to airspeed when landing than is the rectangular

wing. This means that if there is any amount of excess

airspeed at the flair, the semi-tapered wing tends to

float a while before touching down where the rectangular wing settles down more quickly and with less float.

Whatever the reasons may be, the semi-taper wing’s

performance increases are very slight. This writer, having flown both versions of Cherokees prefers the rectangular wing over the semi-tapered wing for its speed,

sprightlier handling and its excellent landing, low-airspeed and stall characteristics; or perhaps it’s also out

of a sense of tradition and nostalgia.

Hershey Bar vs. semi-tapered wings

FOILED AGAIN

Aer careful analysis, the team selected the rather thick

at 15% NACA 652-415 laminar-flow airfoil as it was highly eicient at the airspeeds and altitudes at which the

Cherokee was expected to cruise while still preserving

good low airspeed characteristics and a most gentle,

benign stall.

This airfoil is an NACA “6” series airfoil, has its area

of minimum pressure 50% of the chord from the leading

edge, maintains low drag at 0.2 above and below the li

coeicient of 0.4, has a maximum thickness of 15% of

the chord, a= 0.5 means that the airfoil maintains laminar flow over 50% of the chord.

Despite the NACA numbers, the Cherokee’s wing’s

thickest point is actually closer to 40% back from the

leading edge.

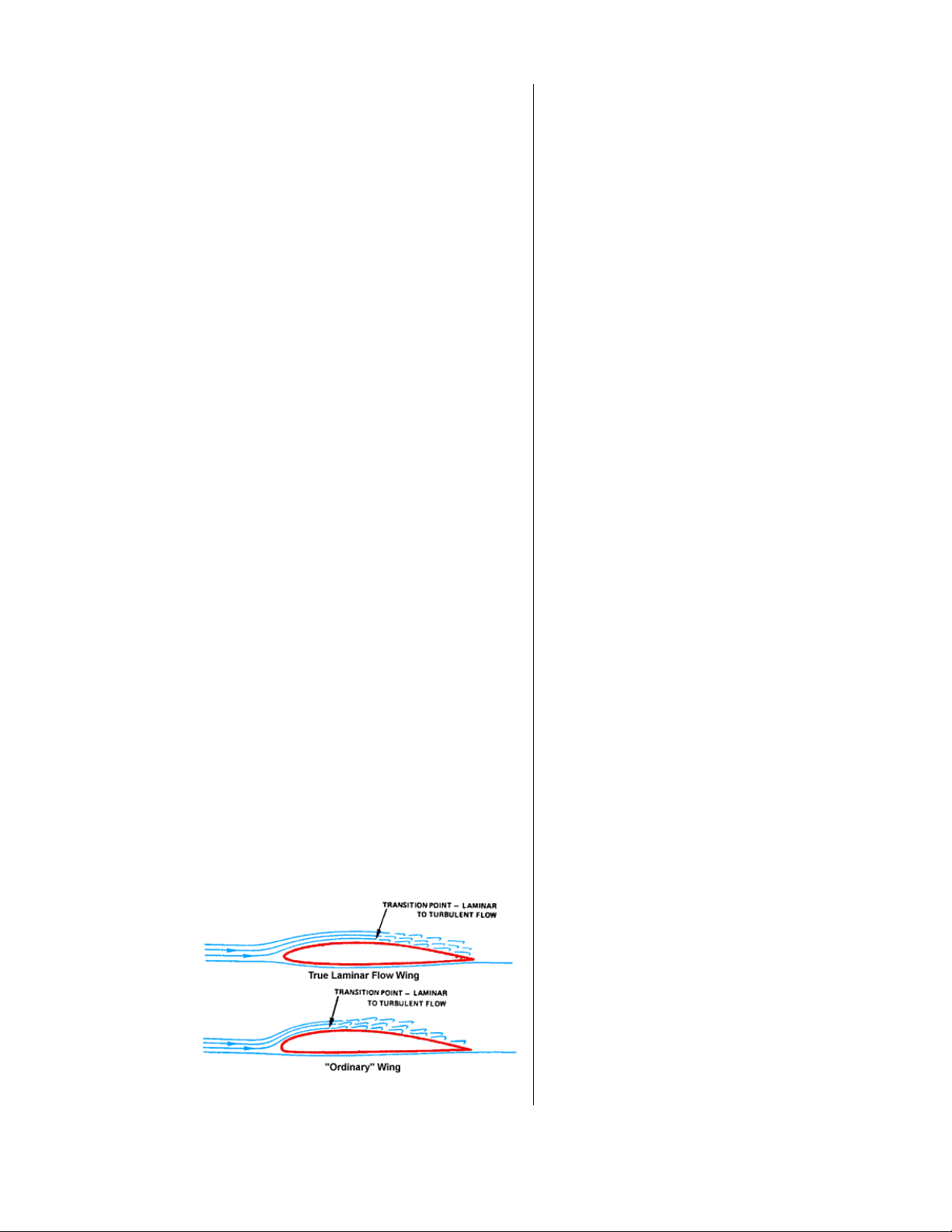

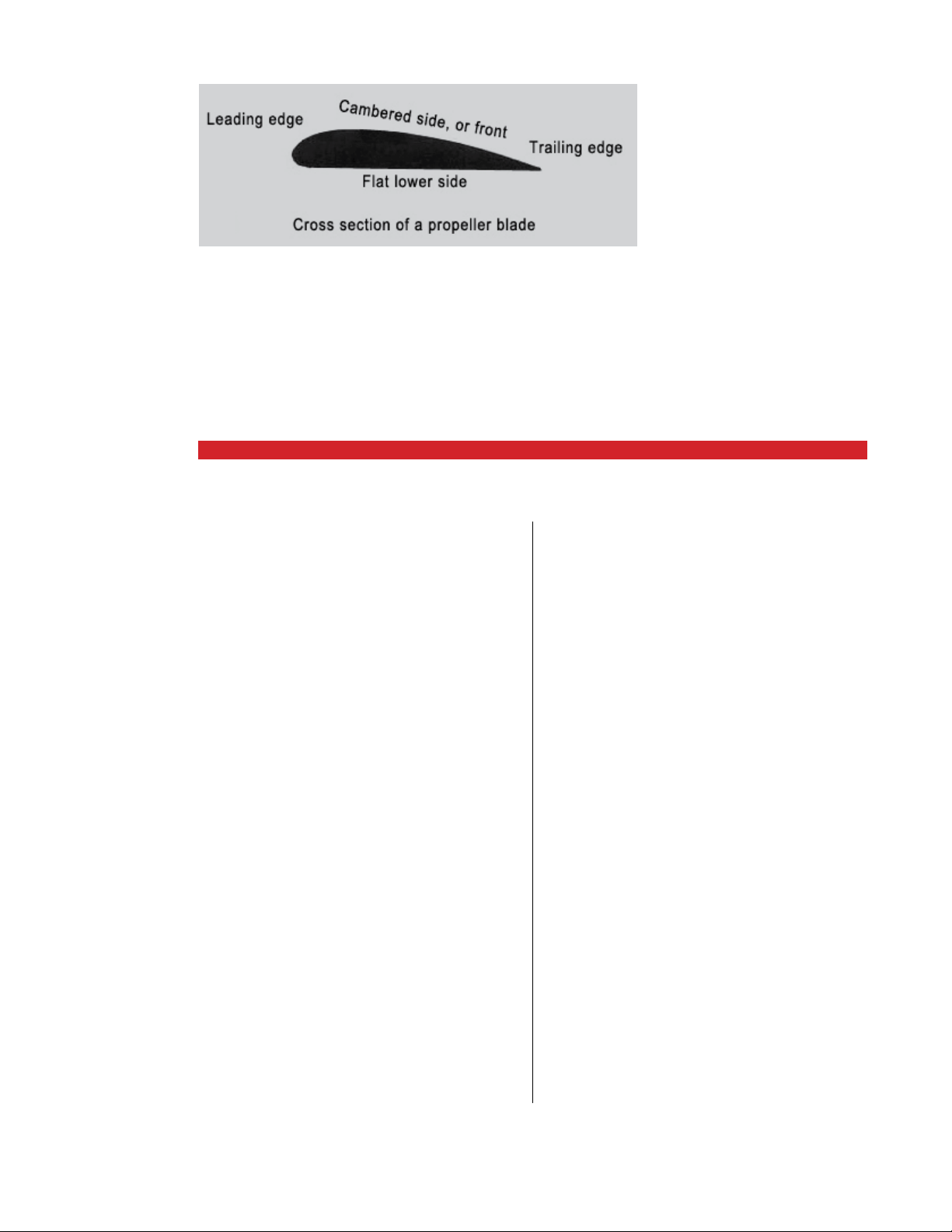

Just a quick word or two about airfoils and what a

“laminar flow airfoil” is. The wing’s airfoil is its crosssection shape from leading to trailing edge and is primarily and most importantly an air diverter*. Among

other things, the airfoil diverts the air through which an

aeroplane’s wing travels downwards at the wing’s trailing edge so that li may be generated (see Newton’s

Third Law of Motion). In order to do this the “boundary

layer”, which is the very thin, viscous layer of air closest

to the surface of the wing, must adhere to the wing and

not become turbulent or detach from the surface of the

wing. As long as the boundary layer adheres smoothly

and uninterruptedly to the surface of the wing, the wing

will continue to divert air downward at the trailing edge

and thereby produce li.

*There are many theories of li, some traditional,

some imaginative and seemingly intuitive. However, in

recent years most of the traditional theories have been

discredited as they were found to be flawed, entirely

improbable or simply wrong as aeronautical knowledge

and understanding has progressed. It is most likely that

there are numerous ways in which a wing produces li.

The airfoil as a downwash “air diverter” at the trailing

Cherokee wing

root without ap

or aileron, “wet

wing” fuel tank

removed (leading

edge facing left)

This is the

Cherokee’s airfoil

straight black

line- chord

curved grey line mid line or mean

camber line

www.a2asimulations.com CHERO KEE 180 MAN UAL

:::

A2ASIMULATIONS

21

Page 22

AN AEROPLANE FOR THE REST OF US

edge is and has for many years been what this writer

thinks is the most probable correct theory. Of course,

the true scientific mind must always be open to new

facts and disclosures. This writer awaits with great interest what is yet to be discovered.

Also, a smooth and adherent boundary layer produces minimum pressure and/or parasite drag enabling

the aeroplane to fly faster for any given amount of power. Slight micro-turbulation in the boundary layer actually increases its adherence to the surface of the wing;

but, when this turbulation becomes more severe and

becomes a turbulent flow, li is reduced and pressure

drag increases. If this turbulence becomes too severe,

which typically happens at critical positive Alpha, the

turbulent boundary layer detaches from the surface

of the wing creating random eddies and vortices causing considerable parasite and pressure drag to be produced. Upon boundary layer flow separation from the

surface of the wing the former downward diverted air

flow ceases and, concurrently, the wing ceases to generate li. This is the “stall”. An airfoil designed to produce

maximum uninterrupted, adhesive boundary layer flow

at the surface of the wing and minimum drag is called a

“laminar flow airfoil”.

Laminar Flow

NACA NUMEROLOGY

The first number, “6”, of NACA 652-415 indicates that

this is a NACA “6-series” airfoil. The second number, “5”,

indicates the position in percentage x 10 of the chord

(leading to trailing edge) where minimum pressure occurs — here indicating the 50% chord position. Minimum pressure usually occurs at the thickest part of the

airfoil.

The subscript “2” indicates that this airfoil’s drag

coeicient approximates its minimum value between

plus or minus 0.2 of the airfoil’s design Cl. The NACA

65(9)-415 airfoil which is a later refinement of the NACA

652-415 has been used in the Cherokee as well, the only

dierence between it and the NACA 652-415 being that

in the latter airfoil the airfoil’s drag coeicient approximates its minimum value between plus or minus 0.9 of

the airfoil’s design li coeicient.

The number “4” indicates the li coeicient in

tenths; here, 0.4.

The last two numbers, “15”, indicate the wing’s maximum thickness as a percentage of the chord; here, 15%

of the chord.

A laminar flow airfoil is typically designed so that its

thickest point is usually at approximately 50% of the

chord. A normal airfoil’s thickest point is usually at approximately 25% to 33% of the chord. The laminar flow

airfoil shape combined with a very smooth wing surface

best promotes a smooth and adherent boundary layer.

The North American P-51 “Mustang” was the first mathematically designed aeroplane and its wing was the first

to be deliberately designed with a “laminar flow” airfoil,

however, even a very slight ripple or bump in or on the

surface of the wing can prevent the true laminar flow effect. Despite all good intentions the P-51’s wing surface

is not suiciently smooth and uninterrupted nor was

it optimally built or usually suiciently maintained in

the field to promote true laminar flow. The Cherokee’s

wing surface, however, is actually far smoother and if

kept scrupulously clean, promotes a stable, adherent

boundary layer very well.

A salient characteristic of the Cherokee’s airfoil is

that it has a fairly flat Cd (Coeicient of Drag) curve and

thereby looses li very slowly as the stall is approached.

Unlike many others, this airfoil does not possess a single

critical angle of attack (positive Alpha) at which it will

stall. The NACA 652-415 airfoil flies within a fairly broad

range of positive Alpha and does not break sharply at

the stall unless very aggressively forced into an extreme

positive Alpha condition called a “deep stall”. Spins

are likewise very diicult to enter unless aggressively

pursued. Additionally, the Hershey Bar wing’s low 5.63

aspect ratio helps to promote the Cherokee’s distinctly

anti-stall/spin behaviour. That these gentle stall/spin

characteristics were incorporated in the Cherokee’s design is no coincidence and very much in keeping with

Fred Weick’s life-long design practices, particularly with

regard to his Ercoupe design which, as mentioned, was

22

A2ASIMULATIONS

:::

CHER OKEE 180 MAN UAL www.a2asimulations.com

Page 23

Simple Polar showing relative differences between

high and low aspect ratio wing (here - AR)

specifically designed to be virtually stall and spin-proof.

Those who have flown a Cherokee will surely attest

to its remarkably benign handling at low airspeed and

its reluctance to stall or spin. In fact, at one “g” with

power o it does not really break at all at the stall, but

merely oscillates gently forward and a while descending rapidly, which is the only indication that the wing

has in fact stalled. Pilots generally find the Cherokee to

be reluctant to stall with power on; although in this configuration the stall break may be a bit more definite with

the le wing falling due to engine torque at high power.

With power on the Cherokee rarely loses aileron control.

This is a sharp contrast to the Cessna 172 which loses

aileron control quite readily when near or at the stall.

These stall characteristics apply to both semi-tapered

and rectangular wing Cherokees, the rectangular wing

being the more benign and reluctant to stall due to its

higher Alpha before stall due to its lower aspect ratio.

Because the Cherokee’s NACA 652-415 laminar-flow

airfoil’s thickest point is near the wing’s mid-chord, approximately 40%, the main wing spar is located farther

a than is possible with non-laminar airfoils. Accordingly, as the main wing spar runs longitudinally across

the wing at its thickest point, its profile is deep and

great strength is gained therefrom. Also, the location

of the main spar so far a locates it under the rear passengers’ seat, permitting the cabin floor to be flat and

unobstructed.

surface is displaced and is more eicient than a conventional fixed stabiliser and hinged elevator. Accordingly,

it may be of less overall area than a similar conventional

fixed and hinged pitch control surface. Accordingly, the

early Cherokees’ stabilator was designed to be approximately two feet shorter in span than later ones making

these Cherokees with shorter stabilators slightly less effective in pitch control, particularly at slower airspeeds.

An anti-servo tab is located at the trailing edge of the

stabilator, similar to a trim tab; however an anti-servo

tab is mechanically linked to the stabilator to move in

the same direction as the stabilator when the stabilator is displaced by the pilot. This provides a proportional opposing force to the displaced stabilator, thus

avoiding negative aerodynamic stability (the tendency

of a balanced, moving, aerodynamic surface to deflect

further as it is displaced from neutral) and which, by

increasing the load on the stabilator as it is displaced,

prevents over- sensitivity in the pitch axis control system at all airspeeds.

In the Cherokee pitch trim is controlled by changing

the angle of the entire stabilator and anti-servo tab. At

the time that the Cherokee was being designed the allflying anti-servo stabilator was already a well-proved,

smooth and highly eicient pitch control system which

possessed the additional properties of being lighter

and, as mentioned, producing less overall drag than

Cherokee

showing

stabilator and

anti-servo tab

KEEPING THINGS STABLE

Following the successful Comanche design, instead of

the usual horizontal rear flight surface consisting of a

fixed stabilizer with a hinged elevator, the Cherokee incorporates a one piece, all- flying “stabilator” with an

anti-servo tab (also called an anti-balance tab) upon

which, not likely coincidentally, John Thorp holds the

patent. A one-piece (i.e. non-hinged), all moving stabilator pitch control surface produces less drag when the

www.a2asimulations.com CHERO KEE 180 MAN UAL

An antiservo

tab attempts

to streamline

the control

surface and is

used to make

the stabilator

less sensitive

by opposing the

force exerted

by the pilot.

:::

A2ASIMULATIONS

23

Page 24

AN AEROPLANE FOR THE REST OF US

How a

stabilator with

anti-servo

tab works

the usual hinged stabilizer and elevator. A stabilator/

anti servo tab horizontal surface very similar to that

which was incorporated in the Cherokee appeared on

John Thorp’s 1945 T11 and T211. While Thorp’s original

design for the stabilator was innovative and eective,

it was also a bit complicated as to linkages and such.

Ever seeking to economise on production costs, Piper’s

Assistant Chief Engineer Karl Bergey modified Thorp’s

system and was able to simplify it while still bestowing

its essential benefits on the new aeroplane.

Speaking of pitch trim, early Cherokees followed

Piper’s unique method of elevator trim control, a horizontal hand-crank and position indicator located in the

ceiling between the front two seats. Tri-Pacers, Colts

and the first Comanches have the same control. It works

fine except that even though it is well-marked, many pilots (me too) have a devil of time remembering which

direction to turn the handle for up or down trim. BTW,

it’s clockwise for up and anti-clockwise for down.

SWEPT AWAY

We might as well get it out of the way here — the swept

back rudder and fin — does it serve any useful aerodynamic purpose as opposed to a straight tail or was it

merely intended to sweep customers o their feet with

a sweeping new design? (apologies)

Piper had incorporated a swept vertical tail on the

1958 Comanche, which this writer believes is the first time

such appeared on any mass-produced GA aeroplane. The

Beechcra Debonaire with its swept rudder and fin was not

introduced until 1960. Having innovated this feature, Piper

made it a priority to incorporate it as a signature design

on its next and subsequent Piper aeroplanes. In any event,

the aeroplane that Piper was most competitive in the GA

entry/middle market, the 1960 Cessna 172A, now had one.

In the late 50’s a swept vertical tail on a GA aeroplane was

new. It certainly looked modern and streamlined and sug

gested the tail surfaces of jet fighters and all. The marketing strategy went something like this: Everyone knows that

jet fighters go fast and that they have swept back surfaces;

so, if your Piper has a swept back rudder/fin similar to a

jet fighter, well then, it ought to go fast as well, right? Of

course, the swept surfaces on jet fighters have much to do

with trans-sonic and super-sonic flight which Comanches,

Cessnas and Cherokees, etc. have little to worry about. For

all of that did the swept rudder/fin on the Comanche, any

of the Cessnas or, more to the point, the Cherokee enable

any of them to fly faster? No, knot at all.

From a strictly aerodynamic perspective a sweptback rudder, its uppermost portion anyway, is located

slightly farther rearward than a straight rudder mounted

in the same position. This slightly moves the rudder’s CP

(centre of pressure) rearward and increases the uppermost part of the rudder’s moment arm which therefore

ought to increase its eectiveness to a small degree.

Others have postulated that the swept back fin/rudder is actually less eective and that it somewhat compromises directional stability and spin prevention. It

may be, however, that with regard to this it was an earlier straight- tailed 172 which was compared to a 1963 or

later swept-tail Cessna 172/Skyhawk with “Omni-Vision”

. If so, it is more likely that the cause of any perceived reduced rudder/fin ineectiveness, etc. was not necessarily the swept vertical surface but was actually the later

-

Piper PA-28-160 Cruiser showing

swept-back n and rudder 1967 Mooney M-20C Ranger 1962 Mooney M-20C Ranger

24

A2ASIMULATIONS

:::

CHER OKEE 180 MAN UAL www.a2asimulations.com

Page 25

aircra’s cut - down rear fuselage which provides for the

“Omni-Vision” rear cabin window, and that the reduced

side area of the fuselage behind the C.G. is the real culprit for any directional stability or spin issues.

Also, if the aeroplane is banked a displaced sweptback rudder will tend to couple with both the aircra’s

pitch axis (as usual) and also positively to greater than

usual degree with the aircra’s roll axis. Accordingly, a

swept forward displaced rudder will couple negatively

with the aircra’s roll axis.

What a swept rudder/fin actually does as compared to a

straight one with regard to relatively low- speed GA aircra

might be able to be measured in a wind tunnel or by a very

sensitive set of in-flight instruments, but this writer is not

aware that any such study has been conducted. Having of

ten flown versions of the same aircra (C-172 and 182) with

both straight and swept tails this writer has not noticed any

appreciable dierence in the performance and handling

thereof that might be due solely to the rudder/fin configu

ration. Taking everything we know into consideration it

seems that a reasonable conclusion regarding this matter

is that the swept back rudder/fin on GA aeroplanes is noth

ing more than an eye- catching marketing tool which is, after all, still a legitimate reason for its existence.

One last, possibly definitive note on this subject; Al

Mooney ostensibly designed the Piper Comanche with

its swept back rudder/fin. However, all of his designs for

Mooney Aircra incorporate rudder/fins that famously

sweep forward.

COMFORT AND ECONOMY

Comfort: One of the important issues that Piper’s design

team had to consider was the creation of a new aeroplane that would cost far less to build and thereby be

able to be sold at a much lower price than the Comanche.

While the team considered that designing an aeroplane

that was less costly to build would not be so arduous a

task (Weick and Thorp had been designing inexpensive to

build aeroplanes for decades), simultaneously providing

the new aeroplane with a cabin as or more comfortable

than anything in its class was a bit more daunting.

Cabin size and particularly cabin width is a tricky

thing to consider when designing a small aeroplane. Every extra inch expands the frontal area and, accordingly,

increases parasite and form drag, resulting in a higher

Cd and reducing performance for available power

across a broad spectrum.

Piper’s target competition, the Cessna 172’s cabin is

a fairly cosy 39 ½” wide. This is a relatively tight fit for

full - sized adults, 1/2” narrower than Piper’s previous

single- engine flagship, the Tri-Pacer, with its snug 40”

cabin width. In years past this writer flew many pleasant

hours in Tri-Pacers and somehow does not remember

that it was such a tight fit; but then that was many years

ago and this writer was then, let’s say, a bit smaller.

The planned cabin width of the new aeroplane was

at first to be a generous 44”, the same width as their then

single-engine flagship, the Comanche. However, Piper

felt that its new, more economical aeroplane ought not

compete so closely with its flagship aeroplane and it

wanted to reserve to the Comanche just a bit more cabin comfort than its less expensive brother. Accordingly,

the Cherokee, as the new aeroplane was finally named,

would have a 40 1/2” wide cabin, still an inch wider than

its closest competitor, the Cessna 172.

Another way that the Cherokee was designed to

increase cabin space while keeping construction cost

low was by utilizing the fuselage’s external belly skin,

strengthened with external stiening members, as the

cabin floor. This was inexpensive, light and required

fewer parts than did many contemporary designs. This

ingenious design treatment added cabin headroom

without the need to expand the outer dimensions of the

fuselage and thus increase parasite and form drag.

In addition to cabin size, Piper wanted their new

aeroplane to be quieter than its competition. The Cessna 172’s design approach is towards a definite lightness

of structure which results in a less noise- insulated cabin

due to the 172 having a rather thin firewall, doors, windows and other structural members resulting in a fairly

noisy cabin. Well-understanding Cessna’s design preferences, Piper looked to find a way to gain an advantage

by reducing the Cherokee’s cabin noise. This was done

by generally using thicker, sturdier structural members

particularly in and around the cabin and by placing the

engine as far forward as possible without jeopardizing good pitch control balance. This kept the engine’s

twin exhaust stacks, which are located near the front of

the engine, as far away from the cabin as possible. The

upshot is that the Cherokee has a very quiet cabin, not

usually requiring headphones for its occupants to converse in flight.

Economy: One of the ways that an aeroplane may be

produced more economically is for it to be designed with

as few parts as possible. The Cherokee was, accordingly,

designed to be extremely simple to construct with much

redundancy (i.e., all wing ribs were the same size, identical le and right parts where possible, etc.) as well as having very few complex curves requiring more costly and

labour intensive aluminium panel construction, shaping

and fitting. Accordingly, the new Cherokee was designed

with less than ½ as many parts as the more complex and

more expensive to build Comanche. A demonstrative example of this is that the Cherokee uses 1,785 rivets while

the Comanche uses more than twice that amount at

3,714. (Yes, I did count them all myself — not)

Another example of intentional simplification is that

the Cherokee’s ailerons require ten parts to construct

while the Comanche’s ailerons require thirty-six parts.

Additionally, and in keeping with his long-held and successful design practices, John Thorp designed all of the

Cherokee’s tail surfaces, flaps and ailerons to be as lightweight, simple and thereby less expensive to construct

www.a2asimulations.com CHERO KEE 180 MAN UAL

:::

A2ASIMULATIONS

25

Page 26

AN AEROPLANE FOR THE REST OF US

Corrugated skin on 30’s W.W. II era transport Junkers

JU-52 “Iron Annie”

Piper Cherokee

rudder showing

corrugated skin

Cherokee

unpainted

stabilator

showing

corrugated skin

as possible by requiring no internal ribs or heavy internal

structures within them. This particular weight- saving

practice is also found in the designs of many GA aircra.

Stiness of the Cherokee’s tail surfaces, flaps and ailerons is provided by beaded (corrugated) surface skins,

similar to that which was pioneered by and appeared on

Junkers aircra of the W. W. I era and later and which was

also largely utilised by John Thorp on many of the aircra

which he had previously designed in order to save weight

and to foster simplicity of construction. Piper was familiar with this construction technique as its PA-18 Super

Cub’s metal ailerons and flaps are covered with the same

kind of corrugated skin for stiness.

Another parts- count, weight and cost saving was

the Cherokee’s incorporation of “wet wing” or “integral”

fuel tanks formed by the wing’s leading edge structure

rather than the usual practice of installing separate fuel

cells within each wing. The wet-wing fuel tank maximises the quantity of fuel that may be carried on board

while requiring the least amount of wing structure to

contain it. Of course, the fuel- carrying part of the wing

must be designed and built with great integrity so that

all panels, rivets, connectors, etc are leak-proof and will

not even slightly separate under flight loads. Possibly

the earliest application of wet wing fuel tanks appeared

in Fred Weick’s remarkably prescient 1936 Ercoupe.

Another cost and weight saving measure applied to

the Cherokee was the innovative and extensive use of

inexpensive- to- produce fibreglass parts in place of aluminium for the wing and stabilator tips as well as for the

cowling. The use of fibreglass in these areas was also

potentially cost-eective for the Cherokee’s owner in

the event that these parts were ever damaged and had

to be replaced as the vulnerable wing and tail tips and

cowling are oen the common victims of “hangar rash”

and other inadvertent abuse.

26

A2ASIMULATIONS

Cherokee with

Cherokee

unpainted

fuselage and

n showing

corrugated skin

:::

CHER OKEE 180 MAN UAL www.a2asimulations.com

“wet wing” fuel

tank removed

Cherokee breglass

wing tips

Page 27

WHEELS AND FLAPS

The Cherokee’s undercarriage is tri-cycle with a fully

steerable nosewheel, independently sprung but directly connected to the rudder control system which was

the same arrangement as was used in the Tri-pacer and

Comanche. In early Cherokees the main undercarriage

brakes were not operated by toe pedals but by a single,

centrally located “Johnson Bar” brake handle, also as

in the Tri-Pacer. This system somewhat limited tight,

precise ground steering and was not a popular feature.

While trying to save on manufacturing costs by using

previously designed, well-proved and readily available

parts and components from the Tri-Pacer, the fact was

that some of these were long overdue for an upgrade.

The Cessna 172 had toe- operated brakes on both sets

of rudder pedals from the get go which was a notable

feature discrepancy. Within a few years and aer many

complaints Piper relented and installed dual individual

main toe brakes for both sets of rudder pedals in the

Cherokee, operated by depressing the tops of the rudder pedals individually to turn or both together to slow

or stop.

Simple, easy to manufacture and to maintain

straight oleo (compressed nitrogen and hydraulic fluid)

struts are used throughout. The Cherokee has a distinct

advantage over the Cessna 172 in that, as a low-wing

design, its main undercarriage is attached directly to

the main wing spar providing maximum strength and

stability. The Cherokee’s 10’ wide main undercarriage

tread provides excellent and stable ground handling

under all conditions while the Cessna 172’s main undercarriage which is a pair of steel struts attached to the

fuselage, has a tread of a little more than 8’ 4”.

Fred Weick had done a number of advanced undercarriage tests when he was designing the Ercoupe which

showed that in a tri-cycle undercarriage the nosewheel

was oen under the greatest load. He also determined

that for operations on grass and on other so fields that

all three tires ought to be the same size. Accordingly,

the Cherokee has 6.00 x 6 tires on all three wheels. With

regard to the Cherokee’s undercarriage, Piper evidently

got it right as pilots have universally praised the Cherokee’s easy, dependable ground handling.

With regard to the Cherokees’ flaps, they are narrow