Page 1

lighting guide

A lighting and lighting accessories

Page 2

Table of ContentsTable of Contents

the power of light

Photography. The literal meaning is “Writing” (graphy) with “light” (photo).

When you press the shutter, you are capturing light. The more effectively you

control that light, the better your photographs will be.

The pages within this guide are designed to provide examples and solutions

to assist you in capturing light effectively in both natural and artificial light.

We will start with an overview of different types of natural light, lighting

concepts and how you can make a dramatic difference to your photographs

by adding artificial light in the form of a single flash. We will then explore using

single and multiple wireless flash to further customize how light is captured.

Portraits, action, landscape, daytime, nighttime, close-ups and much more

are here for you to discover, learn and hopefully implement.

capturing light

06 Light Temperature

06 Direction of Light

07 Time of Day

07 Distance of Light

using artificial light

10 Hard vs. Soft

10 Light Coverage

11 Diffused Light

11 Guide Number (GN)

on-camera flash basics

14 Using Bounce Flash

16 Quick Shift Bounce Advantage

18 Fill Flash

20 High Speed Sync

22 Slow Sync Flash

24 Rear Sync Flash

26 Multi Flash, Stopping Motion

off-camera flash basics

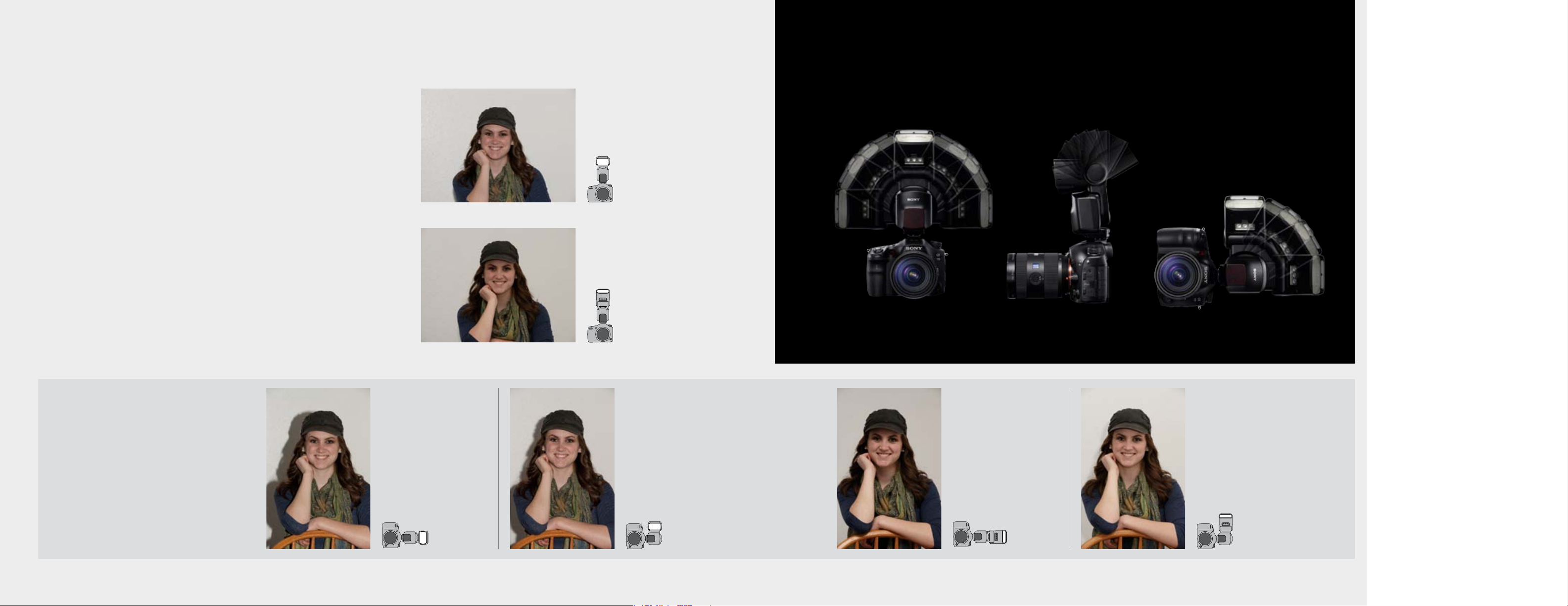

30 On-camera vs. Off-camera Flash Effect

32 One Flash, Two Lights

34 One Flash, Three Lights

36 Wireless Ratio Control

38 Isolate the Subject

40 Mixing Light

products

42 HVL-F60M

44 HVL-F43AM

46 HVL-F20AM

48 HVL-F20S

specialized

50 Macro Photography

52 Ring Light - HVL-RL1

54 Twin Flash - HVL-MT24AM

56 Video Light - HVL-LE1

57 Lighting Accessories

03

Page 3

capturing light

Capturing Light

To capture a photograph, light has to be present in

some shape or form. Used effectively, lighting can even

become the subject or that supporting player that

works behind the scenes elevating the quality of our

image. When not used effectively, lighting will leave

the image too light, too dark, blurry or even filled with

poorly placed shadows.

Tackling light is one of the most challenging and

rewarding things one will face as a photographer.

Learning how to include light effectively in our

photographs will take them from simple snapshots

to images you would be proud to share with anyone.

The following pages outline some considerations to think

about when preparing for lighting and photography.

05

Page 4

understanding light

S

ky Light

1

0

,000 K

9

,

0

00

8,0

K

K

0

0

7,0

Light

Temperature

K

0

0

5,000 K

K

6,000

Flash

Electronic

K

0

1,00

00 K

0

2,

3,000

K

4,00

0

K

D

ay

l

i

g

h

t

Fl

a

sh

b

C

Flood Lamp

u

l

b

andlelig

Light B

t

h

u

lb

Aperture

F/ 11 F/5.6 F/2.8 F/1.4

2ftDistance

4ft 8ft 16f t

Capturing Light

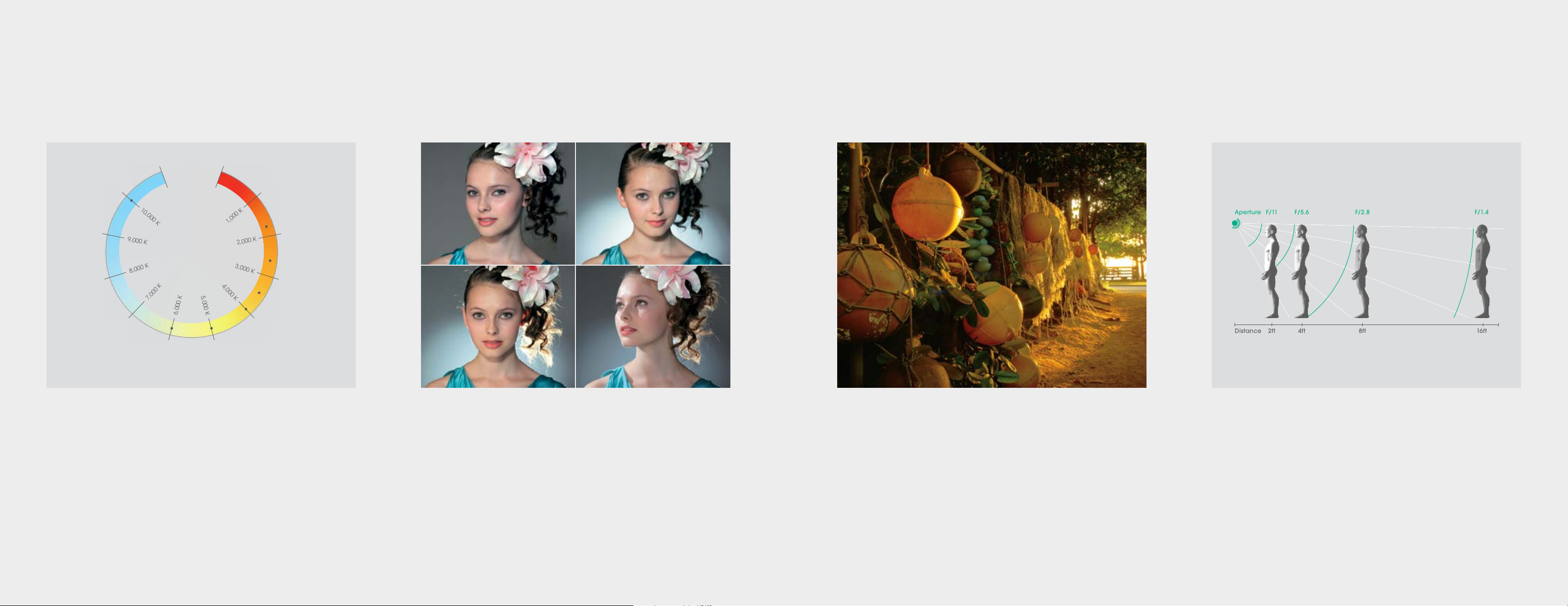

Light Temperature

Every light source—whether the sun, a candle or camera flash—emits a color

temperature that can be measured in the Kelvin scale; named after physicist

William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin.

In general, higher temperature objects (sun, sun through clouds) are referred to as

cool, and contains more blue colors—while lower temperatures (candles and

light bulbs) are referred to as warm, which contain more red and orange colors.

Objects absorb or reflect light rays to give us color. While our human eyes can

recognize the changes in reflected color, digital cameras often “see” light

differently. We may adapt to the yellow glow from a candle light on a white piece of

paper, but your camera may see the paper as yellow. White Balance is a camera

setting, which allows you to adjust the color tone to approximate what you see.

Direction of Light

We normally see objects in everyday life lit from above, whether the sun or a

light fixture in the ceiling. Light can also come from different angles; front, side,

left, right or even below. There are also times when multiple light sources can

illuminate an object from different sides at the same time.

Pay close attention to where the light source is coming from as this can

dramatically affect how your photograph will turn out. Further on in this guide

we will discuss how to bounce light to get a natural look by lighting from

above and adding multiple light sources to improve your image quality and

open your creative freedom.

Time of Day

Consider the time of day when deciding to photograph outdoors. Distance,

direction, quality/quantity of light will change throughout the course of the

day and play an important role in how your images turn out.

Typically, the best time of day to shoot is sunrise or sunset. Also known as “The

Golden Hours”, they provide warmer color tones and long shadows which

deliver a desirable photographic effect. “The Blue Hour” refers to dawn and

dusk, one hour before sunrise and one hour after sunset. This is the time of

day when the light is a clean, cold, blue in color and no shadows are cast.

At midday when the sun is highest, you often get dark shadows and your images

can appear flat, lacking detail, color or dimension. On a cloudy day shadows

will be diminished through diffusion, giving your photos a softer feel.

Distance of Light

It seems obvious to state, but light will be more powerful closer to the source and

weaker farther away from it. In fact, an object that is twice the distance from a

source of light will receive a quarter of the illumination. This is known as the

“Inverse Square Law” which states; “The amount of light is inversely proportional

to the square of the distance between the light source and subject”.

In other words, a subject that is four feet from a light source will need four times

as much light as a subject that is only two feet away. With this in mind, you

will need to compensate for the changing amount of light by adjusting your

camera’s aperture, shutter speed or add more artificial lighting.

06 07

Page 5

using

artificial light

Using Artifical Light

Without light, we would not have photography. The lower

the amount of light on our subject, the longer it will take

to capture our photograph. While we sometimes can use

this to our creative advantage, low levels of light make it

very difficult to capture the subject without blur, especially

if we are not using a tripod or other stabilizing device.

When natural light is diminished, we need to introduce

artificial lighting to capture our image quickly. Lamps,

streetlights, headlights are all examples of commonly seen

artificial light. In photography, all of these can be used

as well as adding artificial light with flash photography.

08 09

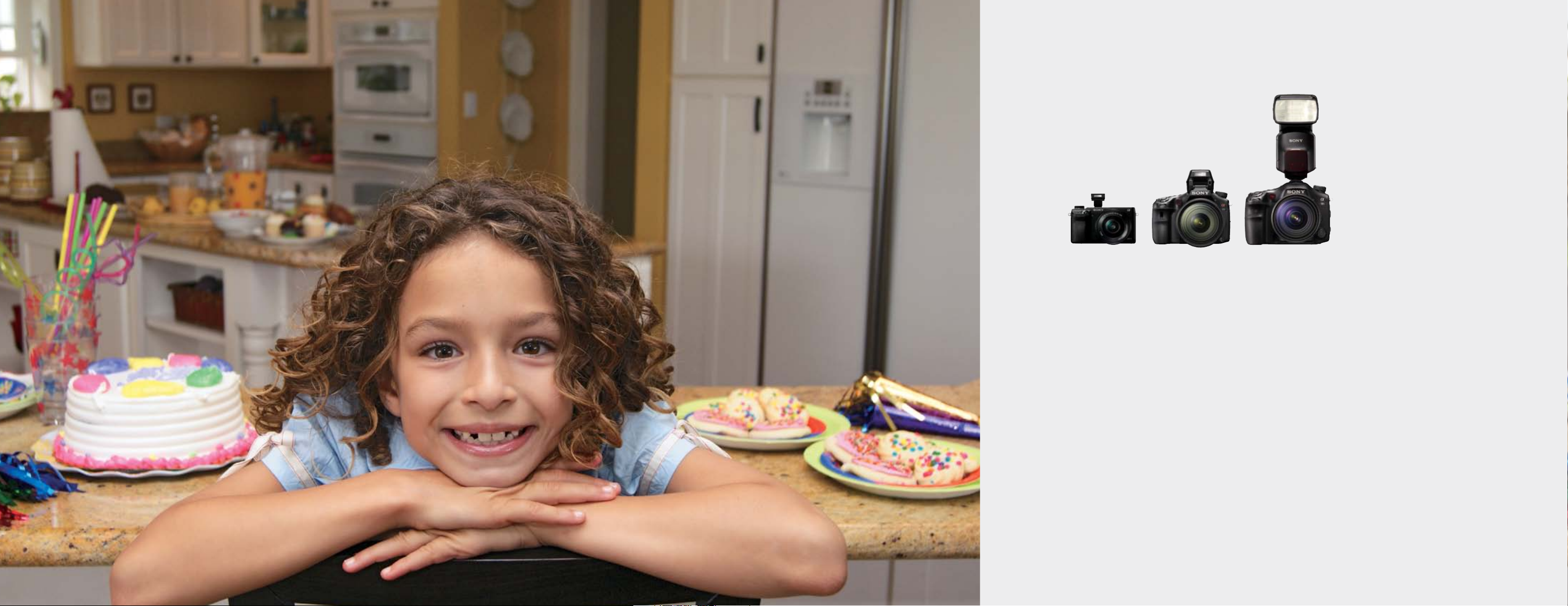

Many cameras have an on-camera flash. While an

on-camera flash can be handy in a pinch, it limits our

options due to the fact that the flash is attached at a

single position to the camera, and has limited power.

Adding an external flash provides us with a more

powerful light with a flash head that can be aimed in

multiple directions allowing us to position our light more

creatively and effectively.

Some flashes can also be used wirelessly, which allows

for even greater creative control. With wireless flash,

our camera can trigger one or more flashes to fire, even

when it is not attached to the camera. This allows us to

add artificial lighting at a variety of locations and angles.

When we combine artificial and natural lighting,

a new level of dynamic photography is achieved.

Page 6

understanding artificial light

Using Artifical Light

Hard vs. Soft

Hard light produces stark shadows and bright highlights. You will typically see

hard light in your photographs when your main light source falls directly on your

subject. A cloudless, midday sun produces hard light, as would a light-bulb or

direct flash from a camera.

Soft light smooths hard lines and edges, reveals more shadow detail and

produces softer highlights. You will typically see soft light in your photographs

when your main light source is close to your subject, reflected off another

surface or diffused. Sun hitting clouds first before hitting the subject, light from

multiple sources and directions, light from a very large light source close to

the subject or light passed through a diffuser are all examples of soft light.

light

light

subject

subject

Light Coverage

When using artificial light, you can control the amount of hard vs. soft light you

want on your subject. If you move the subject further away, the light source

becomes proportionally smaller, casting a harder light. If you move the subject

closer, the light source becomes proportionally larger, casting a softer light.

Using a larger light source and diffusers have the same effect as moving your

subject closer as the light source becomes proportionately larger. Conversely,

using a smaller light source will have the same effect as moving your subject

away from the light source.

Diffused Light

Light that has been scattered by first hitting a translucent property before

hitting our subject is called “diffused light”. Diffused light creates a soft light,

which is more even, with softer shadows.

Diffusers can be anything from a window, white sheet, clouds or even an

actual diffuser, which is commonly used in photography.

Illumination range

85mm ISO100 Aper ture F4

~3m

built-in flash

~11m

HVL-F43AM

~15m

HVL-F60AM

HVL-F60M

Guide Number (GN

Every flash system has a guide number, or GN. It is used to measure the system’s

ability to illuminate the subject to be photographed. It’s good to know the GN when

deciding to buy a flash and how best to use it. The GN represents the output of

illumination that is metered at a distance of 1 meter (3 feet) from the subject at ISO

100. The larger the GN, the larger the amount of illumination the flash produces.

The optimum ap erture set ting can be determined as:

(

f-stop) = GN/(Illumination range between subject and flash in meters).

The optimum illumination range can be calculated as:

Illumination range (m) = GN/(f-stop

For example, when the GN i s 60 and t he aperture is F4, th e illuminat ion

range = 6 0/F4 = 15m (Approx.

)

)

)

10 11

Page 7

On-Camera Flash Basics

on-camera flash basics

An on-camera flash is either the built-in pop-up flash

or an external flash that can be easily added to any

camera that has a hot shoe.

On-camera flash provides the photographer with a

more powerful light source and the ability to better

control the direction of light being emitted.

On-camera flash works with most exposure modes.

The most basic setting on the flash is Auto. Simply

choose your camera mode then set your flash to

Auto. The flash will use a built-in sensor to survey the

surrounding light, fire the flash, and add additional

light to properly illuminate the subject.

Adding flash when needed to your images adds

control and creativity to your results. The Following are

some common practices for using an on-camera flash.

13

Page 8

On-Camera Flash Basics

using bounce flash

Bounce flash should be used when trying to achieve a more natural look.

We normally see the world with light from above, whether the sun or an overhead

light fixture in the ceiling. Using the camera’s built-in flash normally creates

unnatural highlights on our subject or casts shadows on walls and surfaces

behind our subject.

One of the simplest ways to cut back on harsh shadows in our photograph

is to use a bounce flash.

Point the flash at any reflective surface instead of your subject. Ceilings, walls

and white cards are commonly used. Light emitted from the flash will first hit the

flat reflective object, which will then reflect diffused soft light onto the subject.

This effectively makes our light source larger, which produces soft light and soft,

more natural, shadows.

Without flash

With built-in camera flash

What is it?

Technique of reflecting light off of

a nearby surface to change light

direction and soften light source.

How to use it?

• Point your flash to any reflective

surface instead of the subject

• The lighter the surface the

more light will be diffused into

your photo

• Experiment by bouncing your

flash off of walls and different

colored surfaces

Where to use it?

Use bounce flash to create

more natural light and

pleasing shadows.

With external flash HVL-F20AM (bounce flash)

Bounce Sheet

Some flashes have a bounce sheet built into the

camera. Bounce sheets make the subject look more

vibrant. They also add catch lights in the subject’s

eyes. In this case, it also removed some of the

shadows present under the subject’s hat.

14 15

Extras

Would you ever use direct flash? While used rarely, direct

flash is effective when there is minimal ambient light

and you do not have any items to bounce light off of.

Photographing a subject with harsh shadows is better

than not photographing the subject at all.

No Wall? No Ceiling? You can still bounce your flash when

you do not have a wall or ceiling to work with. Simply use

a large white surface instead. It can be a large card,

reflector or even someone’s white shirt.

Page 9

quick shift

bounce

Landscape: Direct Flash

Camera horizontal with flash

pointed directly at the subject in

the standard position.

quick shift bounce

On-Camera Flash Basics

What is it?

Exclusive range of motion offered

on some Sony flashes that allows

for the flash head to remain in

proper orientation, regardless of

camera position or angle.

advantage

A unique feature—exclusive to Sony—Quick Shift Bounce* enables you to

quickly pivot the flash head 180 degrees around the flash body. The head

of the flash can also tilt forward for direct flash and backwards to bounce

off surfaces behind you.

Not only does this give you faster creative control, it also allows you to set the same

bounce flash position while holding your camera horizontally, as well as vertically.

Bouncing flash off walls and objects on either side of the camera is as easy as

pivoting and pointing the flash to the object you want the light to bounce off.

*Quick Shift Bounce is available on the HVL-F43M, HVL-F58AM and HVL-F60M

Taking it vertical

The great thing about Quick Shift Bounce is

that it allows you to easily change and shoot

in portrait orientation and still keep the light

direction consistent. Previously that would

have required a complicated bracket that

attached to the camera. That functionality is

now built into this type of flash.

Portrait: Direct Flash

Camera turned vertical

with flash pointed directly at

the subject in the standard

position. The harsh shadow

on the left is due to the flash

now hitting the subject at an

angle and not straight on.

Landscape: Bounce Flash

Camera horizontal with flash tilted up

45 degrees to bounce light off the

ceiling and further eliminate shadow

and harsh light.

Portrait: Quick Shift Flash

Camera turned vertical with

quick shift used so flash is still

aimed directly at the subject,

but is closer to the camera.

By moving the Quick Shif t

Flash 90 degrees, we are

able to tone down the harsh

shadow behind the subject

by positioning the flash closer

to the camera, and in a more

direct path to the subject.

180° Left/Right 156° Front/Back

Portrait: Bounce

Camera turned vertical with

flash tilted up 45 degrees to

bounce light of f the wall or

reflective surface on the side.

Bouncing Flash off of walls and

objects on either side of the

camera is as easy as pivoting

and pointing the flash to the

object you want to bounce off

of. In this example, we pointed

our flash to a wall on the right.

How to use it?

Simply pivot the flash head

around the body of the flash.

You can move the camera

horizontally or vertically and

re-adjust the flash to keep your

lighting results consistent.

Where to use it?

Use Quick Shift Bounce when you

want to reposition the flash head

or camera quickly and efficiently.

Proper orientation when shooting

portrait compositions

Portrait: Quick Shift Bounce

Camera turned vertical

with quick shift used and

flash tilted up 45 degrees to

bounce light of f the ceiling to

further reduce shadows and

harsh light.

16 17

Page 10

fill flash

Fill flash is a technique used to brighten deep shadow areas, particularly

when photographing backlit subjects. Fill flash is typically used outdoors

on sunny days, though the technique is useful any time the background is

significantly brighter than the subject, or your subject has harsh shadows

caused by an overhead light (like the sun).

To use fill flash, the aperture and shutter speed are adjusted to correctly

expose the background, and the flash is fired to lighten the foreground.

In the first sample image (1) a tree shades our subject, but the rocks behind

her are directly in the sunlight. Changing our camera settings to properly

expose for our subject makes the rocks behind her overexposed.

The second image (2) is the same scene, but this time we have adjusted our

exposure for the rocks in the background. Now our subject standing in the

shade of the tree is grossly underexposed.

Since we now have the rocks properly exposed, all we have to do is add flash.

We used the same settings for the final image as used in shot (2), the only

difference is that the flash fired.

We were able to use the natural light to illuminate our background as well

as use artificial fill flash to illuminate our subject in the foreground.

1. Over-exposed background

2. Under-exposed subject

Properly exposed with fill flash on subject

On-Camera Flash Basics

What is it?

Technique used to add light to

shadows to balance exposure

between the foreground and

background.

How to use it?

Fill flash works with any flash in

any camera mode. For a flash

built into a camera, make sure

you are at least 10ft or closer to

the item you want to illuminate.

Where to use it?

• To remove unwanted shadows

from your subject

• Balance lighting by adjusting

for an overexposed background

and use fill flash to illuminate an

underexposed foreground

• Landscapes where you want to

illuminate the foreground

F5.6, 1/125 SEC, ISO 100

Split-second Breakdown

Shutterblade position over time

Set it up in advance.

When photographing a person, do a test shot

before the model is in the scene to get the exposure

spot-on in advance.

18 19

Flash

Total exposure: 1/125 SEC

Page 11

high speed

sync (HSS

)

Standard Sync Fill Flash

High Speed Sync Fill Flash

On-Camera Flash Basics

What is it?

Allows for use of flash on bright

days with fast shutter speeds

that would normally not sync,

avoiding shutter curtain shadows.

A sunny day gives us the ability to take nice fast photos, but chances are we

might also have to deal with shadows and shade and need to use a fill flash.

We may also want to maintain a nice defocused background at the same time.

In normal fill flash mode we would be limited to a shutter speed of 1/160 to 1/250

sec. depending on our camera, in turn, this would limit our aperture which would

be forced to a high f-stop and result in not much of a defocused background.

In normal flash photography, an instantaneous flash illuminates the subject

when the shutter is fully open. At shutter speeds up to 1/160 or 1/250 sec. the

first curtain shutter opens to completely reveal the sensor before the second

curtain starts moving. When the sensor is fully exposed your flash can fire to

illuminate your subject. However, in faster shutter speeds the second curtain

starts moving while the first curtain is still in motion. If your fill flash had to fire,

only a portion of your image would be illuminated.

In “High-Speed Synchronization” mode (HSS), the flash will emit multi-bursts of

light, illuminating each sliver of sensor exposed while high-speed shutters are open

as slits. This enables flash synchronization up to 1/4000 sec. high-speed shutters.

F14, 1/200 SEC, ISO 160

How to use it?

• High Speed Sync can be found

in the Custom Settings of your

Flash. It is usually labeled HSS

• Set your camera to wireless flash

mode for High Speed Sync to

work or attach an off-camera

flash cord

• Activating High Speed Sync

gives you access to the entire

range of shutter speeds that

your camera offers

Where to use it?

Portraits where the available

light is so abundant that

exposing for your subject leaves

too much depth of field or an

overexposed background.

F2.8, 1/4000 SEC, ISO 160

Split-second Breakdown

Shutterblade position over time

Flash

Total exposure: 1/200 SEC

This photo is a perfect example. To minimize shadows

and shade, a flash was used. However, the goal was

to have the rocks defocused. We can see that did not

happen. Why? With a flash set to a standard setting, it

could not sync with a shutter speed faster than 1/160 to

1/250 sec. With this in mind, the camera adjusted the

aperture accordingly. In this case, in manual mode,

we were limited to an aperture of F16, which allowed in

enough light to give undesired detail to the rocks.

In this photo, High Speed Sync allowed us to use our flash

throughout the entire shutter speed/aperture range

of the camera. This works in both Aperture Priority and

Manual Mode. For the above photo, we turned on High

Speed Sync, put the camera in Manual Mode set an

aperture of F2.8* and a shutter speed of 1/4000 sec.

The flash fired, illuminating our subject. Aperture F2.8 gave

the rocks behind our subject a soft focus and the fast

shutter speed made sure the rocks were not overexposed.

* It is imp ortant to note tha t lenses vary in aper ture settings and wh ile our

lens was a ble to set an aper ture of 2.8, your lens might not. Refer to your

lens owners manual for its specifications.

Split-second Breakdown

Shutterblade position over time

Flashes

Total expos ure: 1/4000 SEC

HSS all owed for use of flas h to fill-in shadows

from sun in bright conditions

20 21

Page 12

slow sync

flash

Standard Fill Flash

Slow Sync Flash

On-Camera Flash Basics

What is it?

Creates a long exposure with

flash to allow ambient light to be

seen and balance natural light

with flash light.

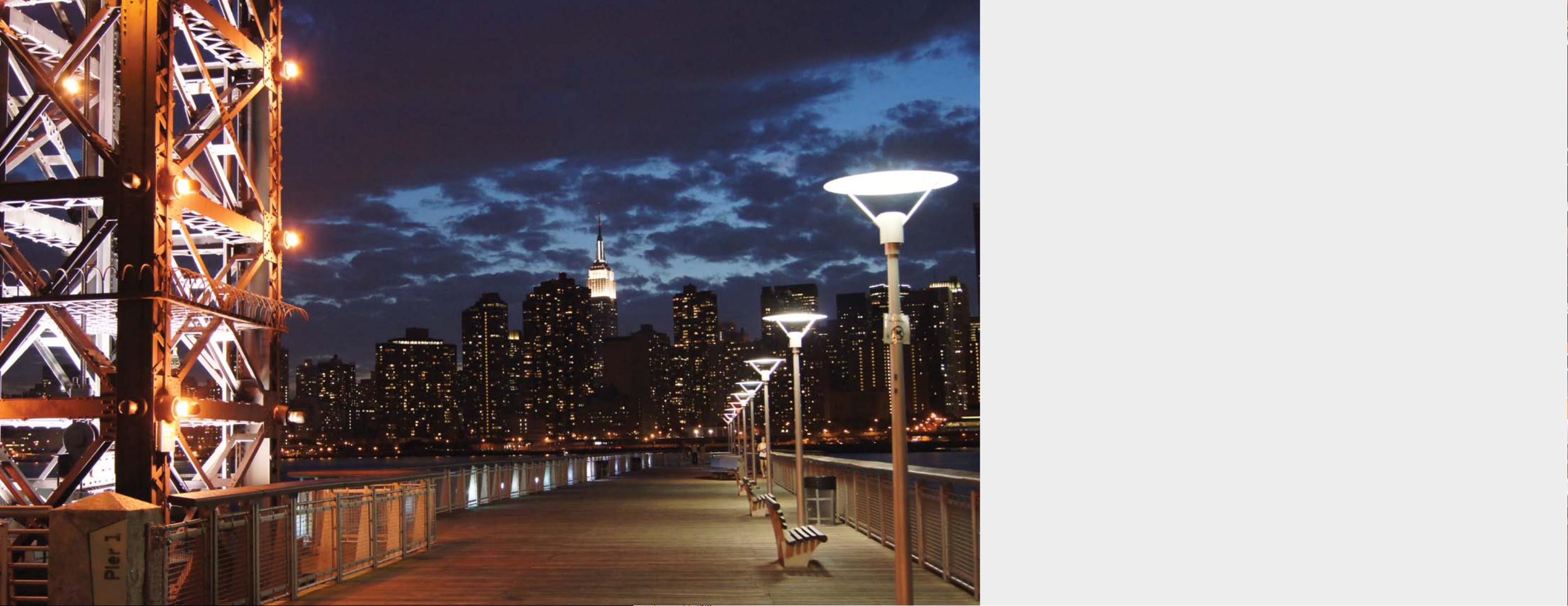

Recreate what your eyes see and tell the whole story.

It’s a lovely evening and you’re out for a stroll when you come across the

perfect setting for a photograph, but you face a problem. Your camera

will either need a long exposure to capture the ambient detail of the lights

which would leave your subject in the foreground in the dark, or your fill

flash will illuminate your subject leaving the background dark and lacking

the mood you originally wanted to capture.

F5, 1/60 SEC, ISO 320

F5, 1/8 SEC, ISO 320

How to use it?

• Set your camera to Slow

Sync Mode

• Place your camera down or use

a tripod to keep it stable

• Set the self-timer or use the

optional wired or wireless remote

control so you are not moving

the camera while it is capturing

the image

• If photographing a person, have

them remain still for the duration

of the photo

Where to use it?

Nighttime shots where the

background is important to

the overall image. Great for

capturing ambient light from

decorations or city lights, while

keeping your subject sharp.

Split-second Breakdown

Shutterblade position over time

Flash

Background Under Exposed

Total expos ure: 1/60 SEC

Most of the time, capturing a moment at night will

require a flash to illuminate the image. However, if you

simply fire the flash you will not be telling the entire story.

The main goal of a flash is to illuminate what is directly in

front of it. At night, this is useful for capturing the subject

but not for capturing what is happening beyond the

range of your flash.

Slow Sync flash allows you to capture both the subject

as well as the background. How? Slow Sync flash will

slow down your shutter speed as well as fire the flash

later in the exposure. A slower shutter speed will allow

more ambient light to be captured and the flash will

ensure your subject and the background behind them

are properly lit.

Split-second Breakdown

Shutterblade position over time

Capturing Ambient Light

Total exposure: 1/200 SEC

Flash

22 23

Page 13

rear sync

flash

Adding motion to your image presents an added level of creativity. Being

able to capture some blur followed by freezing the action allows you to tell a

story about the direction your subject was moving in. To do this; activate the

Rear Sync function in your flash settings and select a slow shutter speed.

1. Without Rear Sync Flash

2. With Rear Sync Flash

On-Camera Flash Basics

What is it?

Triggers flash at end of exposure

instead of beginning to allow for

ambient light to be captured.

How to use it?

• Rear Sync Flash is found within

the flash options of your camera

menu and can be used with a

built in or external flash

In these photographs, we wanted to capture a runner in motion. The photo 1

shows the correct use of Rear Sync. Photo 2 shows what happens when the

standard flash settings are used such as Auto, Fill-Flash or Slow Sync. As you

can see, it looks like the runner is running backwards. Why? A flash set to a

standard setting will fire right after the shutter has been released freezing

the action at the beginning of the motion and capturing the light trail

during the long exposure. This will create an interesting effect that almost

looks like reversed motion.

Split-second Breakdown Split-second Breakdown

Shutterblade position over time Shutterblade position over time

F5.6, 2 1/2 SEC, ISO 250

Manual Mode. Flash set to Fill Flash. 2.5 seconds

F5.6 250 ISO. Because the flash fires first, the remaining

exposure time captures an unnatural trail of light.

• You will need to use a longer

shutter speed so keep the

camera still by using a tripod or

other stabilizing device

• Consider using a remote shutter

release to cut back on-camera

movement

Where to use it?

Use it when you want to capture

the trail of an object in motion or

flowing light more naturally.

F5.6, 2 1/2 SEC, ISO 250

With Rear Sync, the flash does not fire when the shutter

has been released. The flash fires as the shutter closes

at the end of the exposure. This will create a blur of motion

during the exposure and then capture the subject at the

very end creating a more natural trailing light.

Flash Flash

24 25

Blurred motion exposed Blurred motion exposed

Total expos ure: 2.5 S EC Total expos ure: 2.5 S EC

Page 14

multi flash,

On-Camera Flash Basics

What is it?

Fires flash multiple times in same

exposure to capture movement.

stopping motion

To capture the subject in motion, you can set your flash to trigger multiple times

during a single exposure when the subject is moving.

Multi Flash will only work in Manual Mode, you should set your shutter speed

based on the speed that your subject is moving and the desired number of

times you want to freeze the action in a single exposure.

When setting the Flash to Multi, set the number of times you want the flash to

fire and the hertz (time delay) between each flash. For the photo to the left, the

flash was set to fire 5 times at 3hz, which gave us a shutter speed of 1.6 seconds.

Split-second Breakdown

Flash

How to use it?

•Use a tripod

•Set your camera to Manual

• Press the MULTI function on your

flash (check the manual as flash

setting change by model). Then

set the number of flashes you

want to fire and the duration

between each flash.

• Set a longer shutter speed based

on the number of flashes/Hz

• Shoot this in a dark room or

outside at night with minimal

ambient light

Where to use it?

Use it when you want to capture

multiple images showing your

subject in motion.

3Hz 3Hz 3Hz 3Hz

Total exposure: 1.6 SEC

How to calculate:

5/3hz = 1.6 seconds (Frequency/Hz = shutter speed

)

Final Shot

Elegant sequence showing progression of an athlete.

F8, 1.6 SEC, ISO 100. Flash at 1/8 power.

26 27

Page 15

off-camera

flash basics

Off-camera Flash Basics

Sometimes you need light to come from an angle that

the on-camera flash just cannot create, even with

bounce. Or, you need multiple light sources to create

the masterpiece you envision.

Off-camera flash, either wired or wireless, allows us

to fire the flash at the precise moment, intensity and

duration required.

In this section, we’ll cover various off-camera flash

basics, show you how to get multiple light sources from

one flash and dive into wireless ratio control

29

Page 16

on-camera

vs. off-camera

flash effect

On-Camera with Bounce Flash Wired Off-Camera Flash

Off-camera Flash Basics

What is it?

A technique used to move flash

off-camera and change light

direction. Wired flashes use a

physical sync cable to connect

to the camera. Wireless flashes

give you more flexibility than a

wired flash.

Using the on-camera flash has many advantages such as providing more light

where there isn’t enough, or filling in shadows to highlight detail. Although good

to have, on- camera flash is still limited to a single light source close to the lens.

Off-camera flash increases your creative control and greatly improves the

images we can get by enabling us to move the flash away from the camera.

This allows us to get the angle shot we need, as well as the desired lighting

angle—which can be different.

The examples on these pages show how a good image using on-camera flash

with bounce can become a great image by taking the flash off the camera

and lighting the subject from the side.

11f t

The flash is on the camera, which

is 11ft from the subject. The

photographer used bounce flash

to soften the light on subject.

11f t

Same distance, but this time, the

photographer moved slightly to the

left of the subject and placed the

wired flash 4ft right of the camera.

How to use it?

• Wired: Attach the wired flash

cable for one flash and use the

flash to flash cable for each

additional flash. Your flash will

work with the flash settings in

your camera

• Wireless: Set the camera and

flash setting to wireless. Place

the flash within line- of-sight of

the camera

Where to use it?

When you need to light your

subject from different angles

than where you’re taking the

photograph from.

F7.1, 1/125 SEC, -0.3 EV, ISO 200

30 31

F7.1, 1/125 SEC, -0.3 EV, ISO 200

Page 17

one flash,

two lights

Being able to place the flash separate from the camera opens a world of creative

possibilities. We now have better control over the location, amount and

direction of the artificial light added to our images. With the flash on the camera,

this photograph looks flat with harsh shadows.

Now, let’s remove the flash from the camera and position if elsewhere.

The cloth diffuser was able to reduce the shadows, but the right side of the

subject’s face is not as illuminated as her left side. To address this, we simply

placed a white reflective card on the right of the subject. We now have a

single wireless flash illuminating a white cloth to create diffused light on one

side of the subject, which then reflects off of a white card to illuminate both

sides of the subject’s face. This gives us a nice soft light with depth and costs

no more than a single flash and a bit of ingenuity.

On-camera flash

03

SETUP

02

01

Off-camera Flash Basics

What is it?

A technique used to create

a studio looking shot with two

indirect light sources.

How to use it?

• Set the camera and flash

to wireless

• Position the flash on one side

of your subject

• Aim the flash at your subject

through a white diffuser or

simply use a piece of white

linen with translucent qualities

like a tablecloth

• Place a reflector or reflective

surface on the other side of

your subject

Where to use it?

When you only have one flash, but

Off-camera bounce flash, diffuser, reflector

01

Flash

2:1 Light ratio

Different levels of light on your subject can highlight detail and make

your photograph more interesting. These are expressed as ratios. In

this photograph there are two light sources; one direct (Key Light) and

one reflected (Fill Light). The direct light is about twice as strong as

the reflected light. Therefore we have a light ratio of 2:1.

32 33

HVL-60M for adjustable power

and Quick Shift maneuverability.

Attached to included stand for

easy wireless positioning.

02

Diffuser

White linen tablecloth. Translucent

quality allows for diffused soft light

to pass through and increase the

size of our light source.

03

Bounce Card

3' x 2' sheet of white foam

core board.

want to create a studio looking

shot with two indirect light sources.

Commonly used for portrait or

product shots to get a 2:1 ratio.

Off-camera Setup

For an even softer light, we moved

the position of both the flash

and white cloth. The flash still

hits the white cloth first, but then

it bounces off of the reflective

surface behind it.

Page 18

one flash,

three lights

Adding a rim light to our subject creates a halo glow around her helping

define our subject from the background. We now have the flash sitting on a

shelf behind the subject. The flash is backlighting her hair but not much else.

With the flash in the same position we added two white cards in front and to

the sides of the subject at an angle towards the light. The flash now backlights

her hair and then reflects off the white cards to illuminate each side of her

face. The result is a well composed image lit from three sides with one flash.

Off-camera as rim light

Off-camera as rim light with bounce cards

SETUP

02

01

Off-camera Flash Basics

What is it?

A technique used to create a

studio looking shot with three

indirect light sources.

How to use it?

• Set the camera and flash to

wireless

• Position the flash above and

behind your subject

• Aim the flash at your subject, this

will create the rim light

02

• Place two reflectors or reflective

surfaces in front of your subject on

either side. These will reflect the

light back creating a nice fill light

Where to use it?

When you only have one flash,

but want to create a studio

looking shot with three light

sources. Commonly used for

portrait shots to get a 2:1:1 ratio.

01

Flash

2:1:1 L ight ratio

This photograph has a 2:1:1 ratio where the direct light (Rim Light)

from the back is twice as strong as the two reflected light sources

(

Key Light, Fill Light).

34 35

HVL-F60M for adjustable power

and Quick Shift maneuverability.

Attached to included stand for

easy wireless positioning.

02

Bounce Card

3' x 2' sheet of white foam

core board.

Off-camera Setup

For this photograph, the flash was

placed above and behind the

subject pointing down at them.

Two white cards were placed at

an angle in front of the subject

to bounce the light back at her,

illuminating her from three sides.

Page 19

SETUP

14ft

01

wireless

ratio control

Off-camera Flash Basics

What is it?

Dynamically control the volume

of light that is emitted from each

flash in a multiple light setup.

03

01

Background

A flash is placed 14ft away to illuminate

the water behind the subject and is

controlled from the secondary remote

channel of the flash–RMT2.

03

(1+2) Left/right balanced

6ft

02

6ft

02

Camera Right Full

With the flash off behind the subject, we

focus on setting the two flashes slightly

in front and on each side. Here, the right

flash was set to a ratio of 8 while the left

flash was set.

Getting Creative

The light ratio represents how much stronger one light

source is compared to another. A direct light source

could be twice as strong as that same light from a

reflected surface. Therefore, we would have a 2:1 ratio

of direct light vs. reflected light.

Wireless Ratio Control allows us to control the volume

of light that is emitted from each flash or set of flashes

wirelessly. Each set can include more than one flash.

This is easy to do and allows us to set the ratio of the

control flash on the camera plus two more flashes or sets

of flashes. Being able to control all of our flashes from one

source saves time while also allowing for more creativity.

01

0:1

1:2

1:1

How to use it?

Set all your flashes in wireless

mode (WL). Set your flash on

the camera to control (CTL) and

the other flashes to one of the

wireless zone settings (RMT1 or

RMT2). Then set the Ratio Control

in the “control” flash settings.

Here you can set the ratio of

the control flash on the camera

plus two more flashes or sets

of flashes. (Refer to Instruction

Manual for more details

)

Where to use it?

Use this when you want to control

the amount of light emitted from

your wireless flashes.

Two flashes are 6ft away on each side of

the subject. Here is the result of all three

flashes firing at equal power of 16.

Because we were able to change the

Flash Ratio from our on camera flash

we were able to quickly experiment with

different ratios until we achieved the

desired result.

Final Shot

In this three flash setup, we want to add some

dramatic lighting to the subject’s face. We could

move one flash further or closer to the subject

adjusting the amount of light hitting one side

of her face but that would be cumbersome.

Instead we used Wireless Ratio Control from the

flash on our camera.

F7.1, 1/160 SEC, ISO 125

36 37

Page 20

isolate the

subject

Put the focus on the subject. Using a wireless flash is

also a great way to minimize a background. This photo

was captured at a pool with a white wall 8 feet behind

the subject. Firing the flash directly at the subject would

also illuminate the wall behind her. We were able to

direct the light away from the background by placing a

wireless flash on each side of the swimmer. The flashes

emit a more powerful light than the ambient light, to

effectively minimizing the background behind the

swimmer. The resulting shot is a creative way to capture

just the subject without a distracting background.

03

SETUP

22ft

02

11f t

11f t

Off-camera Flash Basics

What is it?

A technique used to isolate

the subject and drop out the

background. This is achieved by

exposing only for the subject

and overpowering the surrounding

ambient light that hits

the background.

01

How to use it?

Aim any and all light sources at

the subject and avoid light spill

onto the background. Avoid any

direct flash when shooting.

Where to use it?

• Any image where the background

is not important to the overall

image. Use this technique when

highlighting the subject’s role in

the image

05

Final Shot

A bucket of water was poured over the subject to

add drama and a sense of action. The flash froze the

droplets in time, adding a narrative to this image.

F9, 1/200 SEC, ISO 400

01

Key Light

The key light, or primary light, is the

main light that defines the image. It

is the first light setup and is generally

the brightest, giving definition to the

subject of the image.

02

Rim Light

The rim light is added for a finishing

highlight that gives definition to

an edge, or rim of an object or

subject. It gives an additional stylistic

element that helps add detail. It is

usually placed above or behind a

subject at a sharp angle, creating a

small but very intense highlight.

03

Fill Light

The fill light is added to reduce the

intensity of the shadows cast by the

key light. It is usually added second

and is less intense than the key

light, providing detail in areas that

would normally be too dark with

just a key light.

• To illuminate boring or distracting

backgrounds

Creative lighting removes this busy background

from the final ima ge

39

Page 21

SETUP

01

mixing light

A new world of creative photography emerges when we

can turn night into day.

Off-camera Flash Basics

What is it?

Multiple flashes synced wirelessly

to allow for freedom of movement

and lighting techniques not

possible with wired flashes.

10ft

02

01

Key Light

The main light is placed 15 feet away

to light up the entire subject and

surrounding scene.

15ft

02

Rim Light

A second flash is placed to the rear

of the subject to give a defining

highlight and help separate him from

the background and add depth.

Set the tone.

The night sky plays a key role in establishing the mood and drama in

this shot. The flash is used to light the subject after we have exposed

the scene for the night sky. This gives a beautiful background for a

properly lighted bicycle rider in action.

Freezing action in a photograph is simple when we

have a lot of available light. However, trying to capture

movement when there is minimal available light usually

results in the subject being blurry. Using wireless flash in

an environment with minimal ambient light will help us

capture our subject in motion while cutting back on the

amount of blur.

In this scenario, we want to illuminate the bicycle rider.

We are too far away (20ft) from the subject to illuminate

him with on-camera flash. Also, we want to increase the

light coverage by lighting him from the front and back.

Knowing that we will be adding flash to this image,

we work on our camera settings to properly capture

the clouds and sky behind him.

Once we are happy with the background we add two

wireless flashes. One is 10ft behind the subject and the

other is 15ft away directly in front of the subject. If we

wanted, we could change the power of each flash or

use wireless ratio control to customize the amount of

flash being added to the image.

Final Shot

Exposing for the background creates a beautiful

contrast with the bicyclist’s yellow uniform and the

flash freezes the motion in place.

How to use it?

• Set your camera to Wireless

Flash Mode

• With your Flash in TTL, press the

Mode button to display WL

• Set the on-camera flash to

control (CTL

• Set your Flash to RMT1 or RMT2

which are two unique channels

your flashes can operate on

• A red blinking light will be

displayed at the base of the flash

showing you it is in wireless mode

• Make sure the blinking red

light is in the direction of your

camera to ensure the camera

can see and operate the

wireless flash effectively

)

Where to use it?

In this situation, a wireless flash

helped us capture motion in a

low ambient light environment.

However, wireless flash can be

used anytime you want to add

creative artificial lighting to

your image.

F7.1, 1/160 SEC, -0.3 EV, ISO 125 DAYLIGHT

F5.6, 1/15 SEC, ISO 400

40 41

Page 22

HVL-F60M

Products

Specifications

60

High-illumination output

Delivers high-illumination output in a compact, lightweight

body, with an effective range of more than 90ft (28m)

and guide number 60. (Guide number measures the

illumination capability of the flash; the higher the number,

the higher the light output. Tested at ISO100, 105mm).

New LED video light

With the new built-in LED video light it has never been

easier to switch between stills and movie shooting even

in low-light conditions. LED enables checking and setting

the light and shadow conditions before shooting still

image or movie with live view function of EVF equipped

camera. Maximum luminance of 1200 lux/(0.5m), with

illuminating distance of approximately 6-1/2ft (2m) at

ISO 320 0/F5.6.

Quick Shift Bounce

Sony’s patented “Quick Shift Bounce” system allows

the HVL-F60M to quickly orbit 90 degrees left and right,

allowing you to maintain horizontal light distribution even

The Sony® HVL-F60M is the flagship flash

with LED light features the “Quick Shift

Bounce” system, “Quick Navi” interface

and Wireless Ratio Control for advanced

lighting in still/movie.

when shooting vertically. In addition to pivoting side-toside, the flash unit can also tilt down 10 degrees or back

150 degrees, ensuring customers the lighting freedom

they need to capture that perfect shot.

Quick Navi and Large Dot Matrix LCD

Quick Navi control is the intuitive User Interface from Sony

A camera bodies that make it a snap to locate and

change settings. A large dot matrix LCD display is easy-to

see and intuitive button layout makes it easy to configure

the HVL-F60M for a variety of shooting needs.

Wireless Ratio Control

Wireless Ratio Control allows customers to wirelessly

control up to three groups of flashes, as well as specify

the luminosity ratio for each group, so they can enjoy

multiple-flash lighting techniques without the need for

special equipment or tedious exposure settings.

Flash

• Flash Type: Auto electronic flash (clip-on type

• Flash Modes: Automatic Light Control (TTL), Continuous

(

10 flashes/sec., up to 40),

pre-flash control, manual control

• Flash Coverage: Covers the angle of view at focal

length between 24mm and 105mm. Automatically

switched at changes in focal length. Manual

24/28/35/50/70/105mm. Covers the angle of view

of at 15mm focal length with the wide panel

• Flash Metering System: Direct TTL

• Guide Number: 6 0

• Modes: High- Speed sync, Wireless, Bounce, Modeling,

Multi-burst

• Function: LED light

• Number of Flashes: 10/sec. up to 40 total

• Recycling Time: 2.6 sec. Ni-MH/3.5 sec. Alkaline

)

Weights and Measurements

• Dimensions (Approx.): (W x H x D) 3-1/4 x 6 x 4-1/8"

(

80 x 150 x 102mm

• Weight (Approx.): 450g (15.9 oz)

(

excluding AA batteries

)

)

Power

•Batter y Type: AA Alkaline /AA Ni-MH- requires 4

General

•Material: Poly-carbonate plastic

42 43

Page 23

HVL-F43AM

56 6020

Products

Specifications

43

High-power illumination

High-power illumination (guide number: 43

Longer effective range

Longer effective range of over 30ft (10.5m

“Quick Shift Bounce”

The innovative “Quick Shift Bounce” system allows the

HVL-F43M to orbit 90 degrees left and right, allowing

you to maintain horizontal light distribution even when

shooting vertically. In addition to pivoting side-to-side,

the flash unit can also tilt down 8 degrees or back 150

degrees, ensuring customers the lighting freedom they

need to capture that perfect shot.

Versatile bounce angles

Versatile bounce angles: 90° up, 90° left. This allows

the flash head to be rotated while maintaining the

set bounce angle, so you can quickly switch between

horizontal and vertical format without changing

the light angle.

)

)

Sony A System HVL-F43AM Flash Unit.

Powerful range, fast recharging, versatile

bounce angles, intelligent features like

auto WB, auto zoom, wireless operation

(

guide number: 43).

Built-In Bounce sheet

The built-in bounce sheet can be used even when

shooting in a vertical position without changing the

angle of reflected light.

Auto white balance

Auto white balance (signals color temp. to camera

Auto zoom

Auto zoom optimized for camera sensor size

Dust and Moisture resistant design

Sealing materials are set at joints of outer materials

(

body, LCD panel, Mounting Foot etc.) and around

movement/operating parts thereby increasing the life

of your flash unit.

Modeling light capability

Modeling light capability allows the HVL-F43M to pulse,

helping photographers determine where shadows will

fall before taking the picture, so they can alter lighting

or subject positioning as necessary.

)

Flash

•Flash Type: Auto electronic flash (clip-on type

• Flash Modes: Automatic Light Control (TTL),

Continuous (10 flashes/sec., up to 40), pre-flash control,

manual control

• Flash Coverage: Bounce angles: Upward - 150 degrees;

Left - 90 degrees; Right - 90 degrees; Down - 8 degrees

•Flash Metering System: Direct TTL

•Guide Number: 43

•Modes: Wireless, Bounce, Modeling, Multi-burst

•Number of Flashes: 10/sec. up to 40 total

•Recycling Time: 2.9 sec.

)

Advanced Features

•Smooth Slow Re c

Weights and Measurements

• Dimensions (Approx.): (W x H x D) 3 x 5-1/8 x 3-1/2"

(

75 x 129 x 87mm

• Weight (Approx.): 12oz (340g)

(

excluding AA batteries

)

)

Power

•Batter y Type: AA Alkaline /AA Ni-MH- requires 4

General

•Material: Poly-carbonate plastic

Operating Conditions

• Storage Temperature: -4 to +140°F

(

-20 to +60°C

)

44 45

Page 24

HVL-F20AM

36 42 43 56 60

Products

Specifications

20

Extends flash range beyond camera’s built-in flash

Though compact and lightweight, the HVL-F20AM has a

maximum range twice that of the built-in flash units on 230,

330 and 380 cameras. This is represented as the guide

number (GN) of 20 with a 50mm focal distance at ISO 100.

Bounce flash enables shadowless indirect lighting

When set to “indoor” shooting mode, the flash points up

to bounce light off the ceiling for shadowless illumination

of your subject. When set to the “outdoor” shooting

mode, the flash directs light directly at your subject.

Built-in diffuser for wide and telephoto shooting

With the built-in diffuser the flash illumination covers an

angle of view of 27mm at the default Standard Position

setting. If users want to shoot at a greater distance,

they can rotate the dial on the side of the flash unit to

the “Tele” Position. Although this reduces flash coverage

to an angle of view of 50mm, it extends the range to

illuminate more distant subjects.

Expand your creativity with the

revolutionary HVL-F20AM compact

external flash, which extends

illumination range beyond the camera’s

built-in flash. Intuitive operation, bounce

capability and TTL auto metering.

Easy intuitive operation

Unlike most external flash units, the HVL-F20AM has no

dedicated ON/OFF switch. Instead, power is automatically

switched on simply by raising the flash unit into the

shooting position. In addition, a switch on the side of the

unit offers Indoor and Outdoor settings, making it easy to

obtain flash illumination that suits the shooting situation.

A charging lamp indicates when the flash is ready to fire.

Light (90g/3.2oz), slim (24mm/1")

ultra-compact design

With a weight of only 90g (Approx.) and a thickness of

only 24mm (1 inch), the HVL-F20AM is so compact it can

simply be folded down and left mounted on the camera

when it is not in use, or detached and carried in a shirt

pocket. When removed from the camera, the flash unit’s

hot shoe can be folded to the side, making the body

even more compact.

Flash

•Flash Type: Auto electronic flash (clip-on type

• Flash Modes: Automatic Light Control (TTL),

Continuous (10 flashes/sec., up to 40), Re-flash Control,

Manual Control

• Flash Coverage: Bounce angles:

Upward - 150 degrees; Lef t - 90 degrees; Right - 90

degrees; Down - 8 degrees

•Flash Metering System: Direct T TL

•Guide Number: 43

• Modes: Wireless, Bounce, Modeling,

Multi-burst

•Number of Flashes: 10/sec. up to 40 total

•Recycling Time: 2.9 sec.

)

Advanced Features

•Smooth Slow Re c

Weights and Measurements

• Dimensions (Approx.): (W x H x D) 3 x 5-1/8 x 3-1/2"

(

75 x 129 x 87mm

• Weight (Approx.): 12oz (340g)

(

excluding AA batteries

)

)

Power

•Batter y Type: AA Alkaline /AA Ni-MH- requires 4

General

•Material: Poly-carbonate plastic

Operating Conditions

• Storage Temperature: -4 to +140°F

(

-20 to +60°C

)

46 47

Page 25

HVL-F20S

36 42 43 56 60

Products

Specifications

20

Extends flash range beyond camera’s included flash

Though compact and lightweight, the HVL-F20S has

a maximum range twice that of the included flash

units of the NEX-3, NEX-5 and NEX-C3 cameras. This is

represented as the guide number (GN) of 20 with a

50mm focal distance.

Bounce flash enables shadowless indirect lighting

When set to “indoor” shooting mode, the flash points up

to bounce light off the ceiling for shadowless illumination

of your subject. When set to the “outdoor” shooting

mode, the flash directs light directly at your subject.

Designed exclusive for Sony E-mount

cameras, the HVL-F20S external flash is

the perfect accessory for extending

illumination range and includes bounce

capability and TTL auto metering.

Built-in diffuser for wide and telephoto shooting

With the built-in diffuser, the flash illumination covers

a wider angle of view or if users want to shoot at a

greater distance, they can rotate the dial on the side

of the flash unit to the “Tele” Position. While the “Tele”

setting reduces the width of flash coverage, it extends

the range to illuminate more distant subjects.

Easy intuitive operation

Unlike most external flash units, the HVL-F20S has no

dedicated ON/OFF switch. Instead, power is automatically

switched on simply by raising the flash unit into the

shooting position. In addition, a switch on the side of the

unit offers Indoor and Outdoor settings, making it easy to

obtain flash illumination that suits the shooting situation.

A charging lamp indicates when the flash is ready to fire.

Flash

•Flash Coverag e: F4: 1m–5m

•Guide Numb er: 20

Weights and Measurements

• Dimensions (Approx.): (W x H x D) 2-3/8 x 2-7/8 x 2-1/8";

(

60 x 71 x 53mm

•Weight (Approx.)(Main unit only): 2.3oz (63g

ADI Flash Metering System

The ADI (Advanced Distance Integration) flash metering

system offers the optimum flash metering and

automatic white-balance compensation regardless of

the background conditions or the subject’s reflectance.

ADI flash metering works in combination with cameras

and lenses that incorporate a distance encoder. When

used with these lenses, the camera calculates a guide

number to control TTL (through the lens) flash metering.

This guide number is calculated according to distance

from the subject, ambient light and pre-flash reflectivity

of the subject and the background.

)

)

48 49

Page 26

Specialized

lighting

for macro

photography

Macro photography most often refers to capturing extreme close-ups of small

objects. Normally the size of the resultant image is equal to or larger than the

subject itself.

Even though macro lenses are often capable of a large aperture and very

shallow depth of field, which may be good for portrait photography, is not always

good for macro photography. Depth of field is extremely shallow when focusing

on close objects which means you may need to use a smaller aperture like F11

to get the entire subject in focus. This will require either a slow shutter speed, high

ISO or brilliant lighting. That’s where specialized lighting for macro photography

can help us take better macro photographs.

Adding a flash or ring light will introduce additional light and reduce the time

needed to take the photo. Using a flash or ring light will also allow us to remove

the need for a tripod allowing you to position the camera easier for more

creative results. We can also move quickly and effectively to capture our image.

Specialized

What is it?

Photographing small items very

close to bring out minute details.

How to use it?

•Get Close

• Stabilize the camera if not using

a flash

• Aperture Priority F11 but

experiment with different

numbers. Remember the larger

your aperture the less of your

subject will be in focus

Where to use it?

•Flowers

•Objects

•Insects

• Anything where getting closer to

the subject will uncover things

you never knew were there

Adding a flash or ring light also allows us to highlight our subject and remove the

background from our photographs.

Final Shot

Utilizing a twin flash, we added precise lighting giving a soft dynamic

mood, and capturing a beautiful floral macro shot.

F9, 1/200 SEC, ISO 100

50 51

Page 27

ring light

A Ring Light actually surrounds the entire lens with

constant light. This allows us to illuminate the entire

subject evenly from all directions. Our resulting photo will

have even lighting with minimal shadows. Ring Lights are

used frequently in Macro Photography due to the amount

of detail they are able to capture.

The intensity of the powerful LED light can also be varied

with the dimmer. In addition we can chose to light only

one side of our subject for dramatic affect or to highlight

detail. Adjust the switching from either having the entire

ring light on or have only the left side, right side on.

Direct Flash

Hard directional light, casts strong

shadows and obscures detail.

F16, 1/100 SEC, - 0.3 EV, ISO 320

01

Left side solo

02

Both sides active

03

Right side solo

What is it?

Lens mounted ring of light that

evenly lights close items with

uniform light.

How to use it?

• Attach the Ring Light and set light

intensity with the dimmer to get

the exposure you are looking for

in your selected aperture

• You can also set the Ring Light

to only illuminate the left or right

side of your subject

Where to use it?

• Macro photography with

minimal shadows

• Portrait photography where

you want a ring of light in the

subject’s eyes

HVL- RL1

The HVL-RL1 offers highly effective illumination of small

subjects for macro shooting. Its powerful 700 lx/0.3m

(

Approx.) LED performance is approximately 4 times

brighter than conventional models. The brightness can

also be dimmed with a control dial to achieve creative

lighting that subtly reflects your intentions. Extremely

smooth lighting effects can also be achieved without

clearly revealing the source of light.

Capture even and well-lit macro

photography with this ring light attachment

and your compatible Sony A camera. It’s

the perfect tool for creating compelling

close-up artwork.

•Full-ringilluminationforshadowlesslighting

•Half-ringilluminationforshadowsandcontrast

•Continuousilluminationallowslightingtobechecked

at any time

•Filterdiameter:49mm,55mm

•ShoeAdaptor(ADP-AMA) is included for usage with

Auto-lock Accessory Shoe cameras

Specifications

Ring Light

•Flash Type: Auto electronic ring light (clip-on type

•Lighting Modes: Full, 50% Left, 50% Right

•Luminance: 700 lux (at 0.3m

)

Advanced Features

•Dimmer for precise control

Weights and Measurements

• Dimensions (Approx.): (W x H x D) 4-7/8 x 5-1/2 x 15/16"

(

124 x 141 x 24mm

• Weight (Approx.): 6.9oz (195 g)(excluding AA batteries

)

Power

•Battery Type: AA Alkaline /AA Ni-MH-requires 4

General

•Material: Poly-carbonate plastic

Operating Conditions

• Operating Temperature: 32 to +104°F

(

0 to +40°C

)

)

Specialized

)

F16, 1/8 SEC, -0.3 EV, ISO 320

F16, 1/8 SEC, -0.3 EV, ISO 320 F16, 1/8 SEC, -0.3 EV, ISO 320

52 53

Page 28

twin flash

A Twin Flash is exactly that—two flashes. They give you far

greater control when photographing objects close-up.

The Twin Flash attaches to the front of the lens. Each

flash is on its own individual arm, which can be

adjusted in a variety of angles. You can also move the

flash arms around the ring attachment itself which gives

you a multitude of lighting possibilities. The output level

on each individual Twin Flash can also be adjusted to

create an even more dramatic lighting effect.

Using a Twin Flash in your close up photography will give

your photos additional detail, texture and dimension.

Direct Flash

Makes petals appear flat and

lacking dimension. Blows out color

and contrast.

F18, 1/200 SEC, ISO 100

Twin Flash in use

By switching to a twin flash not only were we were able

to direct the location of our light more effectively, we

were able to do this with two light sources allowing

us to capture more depth and detail. Both flashes

were extended the full seven inches from the lens and

were set at the 10 o’clock and 2 o’clock position. The

background is eliminated as the flash only highlights the

orchid in the foreground.

What is it?

Dual lens-mounted flashes

which can be extended, moved,

positioned and adjusted for close

up photography.

How to use it?

• Simply attach the twin flash to

your camera lens

• You can physically change the

length and the position of each

flash as well as change the

mode and coverage using the

included accessory shoe

• Keep changing the distance and

location of the flashes to discover

a variety of lighting effects

Where to use it?

For macro photography, when

adding dimension as well as

minimizing backgrounds.

HVL-MT24AM

Twin flashes

Twin flashes: 45° vertical, 60° horizontal. When wide

panel is mounted: 60° vertical, 78° horizontal. When

diffuser (1 flash) is mounted: 90° vertical, 90° horizontal

Wide coverage

Covers fields of view of 24mm lenses

Auto locking

Auto locking foot

Capture impeccably lit macro photographs

every time with the HVL-MT24AM macro

twin flash kit and your a DSLR camera.

Take your extreme close-up photography

to the next level by easily arranging the

twin adjustable flash heads in countless

configurations.

Specifications

Flash

• Flash Modes: Wide Panel lighting angle: Approx. 60

degrees (Vertical), Approx. 78 degrees (Horizontal

• Flash Coverage: Guide Number: 24

(

Power level 1/1

)

Convenience Features

•Media/Battery Indicator: READY Lamp

Interface

•Accessory Shoe: Intelligent Accessory Shoe

Weights and Measurements

• Dimensions (Approx.): (W x H x D) 68 x 123 x 91mm for

Macro flash controller, 43 x 41 x 37mm for Twin flash unit

• Weight (Approx.): 8.3oz (235g) for Macro flash

controller, 1.2oz (33g) for Twin flash unit

Power

• Batter y Type: AA Alkaline/AA Ni-MH

[

Weight (Approx.): AA Alkaline 23g x 4, AA Ni-MH 29g x 4

•Power Requirements: 4 batteries required

General

•Material: Poly-carbonate plastic

Operating Conditions

•Color Temperature Control: Approx. 5700K

•Storage Temperature: -4 to +140°F (-20 to +60°C

)

)

Specialized

]

The arms of the t win flash allow for preci se

lighting of sma ll obje cts that a larger flash

would miss or overpower

54 55

Page 29

Specialized

HVL-LE1

Don’t let low lighting ruin your shoot. Solve lighting issues

quickly by attaching a battery powered LED video light

and see an instant difference in the way things appear.

Choose from a variety of battery options—AA Alkaline,

AA Ni-MH, NPFV or NP-FM50—to power up this light. With

a handy battery life indicator, you’ll know ahead of time

if power is running low so you won’t miss that crucial

shot. Ships with diffuser, color conversion filter (3200K),

barn door, A shoe adaptor and ISO shoe adaptor.

Solves lighting issues quickly with the

HVL-LE1 and see an instant difference in the

way things appear. Wide choice of battery

options—AA Alkaline, AA Ni-MH, NPFV or

NP-FM50 Sony lithium-ion batteries.

Advanced Features

•Supplied3200Kcolordiffuser,barndoor

•Swivel-ableshoe,180degreesleftorright,80degrees

forwards or backwards

•IncludesAuto-lockandcold-shoeadaptersfor

maximum versatility

Specifications

Battery LED Video Light

• Light Type: Auto electronic light (clip-on type

• Lighting Modes: Adjustable brightness control

(

)

10–10 0%

•Max. Luminance: 1800 lux/0.5m, 450 lux/1m

Weights and Measurements

• Dimensions (Approx.): (W x H x D) 4-3/4 x 3 x 2-1/2"

(

120 x 75 x 63mm

• Weight (Approx.): 8.9oz (250g)

(

excluding AA batteries

)

)

Power

• Battery Type: AA Alkaline /AA Ni- MH-requires 4,

NP-FV50/FV70/FV100, NP-F50 Sony

Lithium-ion batteries

General

• Material: Poly-carbonate plastic

•Operating Conditions

•Operating Temperature: 32 to +104°F (0 to +40°C

)

lighting accessories

Multi Flash Cable - FA-MC1AM

• Connector cable enables flash illumination from

multiple flash units

)

External Battery Adaptor - FA-EB1AM

• External battery pack for HVL-F56AM

Extension Cable for Flash - FA-EC1AM

• Approx. 1.5m extension for off-camera cable

FA- C C1A M (sold separately

)

Triple Connector for Flash - FA-TC1AM

• Enables synchronized operation of up to 3 external

flash units

Off-Camera Cable - FA-CC1AM

• Connector cable for external flash units

(

HVL-58AM/HVL-F56AM: connects directly.

HVL-F42AM/HVLF20AM: requires off camera shoe FA-CS1AM.)

Off-Camera Shoe - FA-CS1AM

• Allows for easily mounting the external flash onto the

off- camera shoe and connecting to the camera body

via the off-camera-cable

Macro light adaptor - FA-MA1AM

• Adaptor for connecting Macro Light and lens

•Easy to attach and detach

Shoe Adapter - ADP-MAA

•This shoe adapter allows you to use auto-lock

shoe-compatible accessories with cameras and

camcorders that feature a new multi-interface shoe

Shoe Adapter - ADP-AMA

•This shoe adapter allows you to use new

multi-interface accessories with your Alpha DSLR

camera’s auto-lock accessory shoe

56 57

Page 30

Please visit the online training guide at

www.sonydigitalimaging.com

a is trademark of Sony Corporation

Screen displays are simulated.

Simula ted effe cts are used to illus trate some f unctions.

© 2012 Sony Electro nics Inc. A ll right s reser ved. Repro ductio n in whol e or in par t withou t writ ten perm ission i s prohib ited. All ot her trad emarks a re tradem arks of the ir respective

owners. Features and specifications are subject to change without notice.

Sony Electronics Inc. | 16530 Via Esprillo | San Diego, CA 92127 | 1-800-222-7669 | www.sony.com

DI12022

Loading...

Loading...