Page 1

Page 2

Microsoft ®

®

Visual Studio

A Beginner’s Guide

2010

Page 3

About the Author

Joe Mayo started his software development career in 1986, working on an RCA

Spectrum 70 mainframe computer, programming in assembly language where input was

via Hollerith card, output was a line printer, and the debugging experience was a light

panel where you had to push buttons to load registers and step through commands. Since

then, Joe has worked with various mini-computers, workstations, and PCs. The operating

systems he’s worked on include proprietary, UNIX-based, MS-DOS, and Windows.

Besides assembly and dozens of scripting languages, Joe has worked professionally with

C, C++, VBA, Visual C++, Forte Tool, Java, VB.NET, and C#. In addition to software

engineering, he has worked in many positions, including team lead, supervisor, manager

(even running a 24×7 computer operations center with over 50 people). Today, Joe runs

his own company, Mayo Software, providing custom software development services

and specializing in Microsoft .NET technology. He is the author of LINQ Programming

(McGraw-Hill Professional, 2008) and other books. Joe is also the recipient of multiple

Microsoft MVP awards. You can follow Joe on Twitter: @JoeMayo.

About the Technical Editor

Roy Ogborn has worn almost every hat one time or another during his interesting and

continuing career in the Information Technology field. He was systems manager and

developer for Texaco Europe Research, Inc., in Moscow, USSR, during the attempted coup.

Back in the United States, he has designed and implemented a GIS system for managing

oil and gas wells and leases, and has architected and implemented an enterprise workflow

system that managed the business process of taking wells from conception to completion.

He architected a system for Forest Oil in Denver that linked disparate accounting, lease

management, and production tracking systems for business intelligence for senior executives’

daily and strategic decisions. Recently he architected and designed a SharePoint-, Silverlight-,

and CSLA-based greenhouse gas emissions evaluation, prediction, and decision tool for a

multinational environmental engineering firm using the new Visual Studio 2010 Architecture

Edition tools. Roy is an independent software architect consultant in the Denver Metro Area

specializing in custom solutions that leverage SharePoint. In January 2010 he presented

SharePoint 2010 for Developers at the Denver Visual Studio .NET User Group.

Page 4

Microsoft ®

®

Visual Studio

A Beginner’s Guide

Joe Mayo

2010

New York Chicago San Francisco

Lisbon London Madrid Mexico City

Milan New Delhi San Juan

Seoul Singapore Sydney Toronto

Page 5

Copyright © 2010 by The McGraw-Hill Companies. All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976,

no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without

the prior written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978-0-07-166896-5

MHID: 0-07-166896-9

The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: ISBN: 978-0-07-166895-8, MHID: 0-07-166895-0.

All trademarks are trademarks of their respective owners. Rather than put a trademark symbol after every occurrence of a trademarked name,

we use names in an editorial fashion only, and to the benefi t of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark.

Where such designations appear in this book, they have been printed with initial caps.

McGraw-Hill eBooks are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales promotions, or for use in corporate training

programs. To contact a representative please e-mail us at bulksales@mcgraw-hill.com.

Information has been obtained by McGraw-Hill from sources believed to be reliable. However, because of the possibility of human or

mechanical error by our sources, McGraw-Hill, or others, McGraw-Hill does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of any

information and is not responsible for any errors or omissions or the results obtained from the use of such information.

TERMS OF USE

This is a copyrighted work and The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. (“McGrawHill”) and its licensors reserve all rights in and to the work. Use

of this work is subject to these terms. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act of 1976 and the right to store and retrieve one copy of the

work, you may not decompile, disassemble, reverse engineer, reproduce, modify, create derivative works based upon, transmit, distribute,

disseminate, sell, publish or sublicense the work or any part of it without McGraw-Hill’s prior consent. You may use the work for your own

noncommercial and personal use; any other use of the work is strictly prohibited. Your right to use the work may be terminated if you fail to

comply with these terms.

THE WORK IS PROVIDED “AS IS.” McGRAW-HILL AND ITS LICENSORS MAKE NO GUARANTEES OR WARRANTIES AS

TO THE ACCURACY, ADEQUACY OR COMPLETENESS OF OR RESULTS TO BE OBTAINED FROM USING THE WORK,

INCLUDING ANY INFORMATION THAT CAN BE ACCESSED THROUGH THE WORK VIA HYPERLINK OR OTHERWISE,

AND EXPRESSLY DISCLAIM ANY WARRANTY, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO IMPLIED

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. McGraw-Hill and its licensors do not warrant

or guarantee that the functions contained in the work will meet your requirements or that its operation will be uninterrupted or error free.

Neither McGraw-Hill nor its licensors shall be liable to you or anyone else for any inaccuracy, error or omission, regardless of cause, in the

work or for any damages resulting therefrom. McGraw-Hill has no responsibility for the content of any information accessed through the

work. Under no circumstances shall McGraw-Hill and/or its licensors be liable for any indirect, incidental, special, punitive, consequential

or similar damages that result from the use of or inability to use the work, even if any of them has been advised of the possibility of such

damages. This limitation of liability shall apply to any claim or cause whatsoever whether such claim or cause arises in contract, tort or

otherwise.

Page 6

To my son, Kamo.

Page 7

This page intentionally left blank

Page 8

Contents at a Glance

PART I Understanding Visual Studio 2010 Essentials

1 Introducing Visual Studio 2010 . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . . 3

2 Learning Just Enough C# or VB.NET: Basic Syntax . .. .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . 35

3 Learning Just Enough C# and VB.NET: Types and Members . .. . . .. . . .. . 67

4 Learning Just Enough C# and VB.NET: Intermediate Syntax . . . .. .. . . . . 89

PART II Learning the VS 2010 Environment

5 Creating and Building Projects . . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . 113

6 Debugging with Visual Studio . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . 143

7 Working with Data . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . 181

PART III Building Programs with VS 2010

8 Building Desktop Applications with WPF . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . . . 217

9 Creating Web Applications with ASP.NET MVC . . .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . 249

vii

Page 9

10 Designing Silverlight Applications . . . . .. .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . 285

11 Deploying Web Services with WCF . . .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . 299

PART IV Enhancing the VS 2010 Experience

12 Customizing the Development Environment . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . 341

13 Extending Visual Studio 2010 . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . . 371

PART V Appendixes

A Introduction to XML . .. .. . . . .. .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . 403

B Introduction to XAML . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . 409

Index . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . . 417

Page 10

Contents

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . xvii

INTRODUCTION . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. . xix

PART I

1 Introducing Visual Studio 2010 . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . . 3

Understanding Visual Studio 2010 Essentials

What Is Visual Studio 2010 About? . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. . 4

Automatically Generated Code . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. . 4

Rapid Coding Experience . .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. 5

Everything at Your Fingertips . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. 5

Customizability and Extensibility . .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. . 5

Installing Visual Studio 2010 . . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. 6

Navigating the Visual Studio 2010 Environment . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . 13

The Menu . . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. . 14

Toolbar . .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. . 15

Work Area . .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. 15

Toolbox . .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . 16

Solution Explorer . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. . 16

Status Bar . . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. 16

Managing VS Windows . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. 16

Expanding and Collapsing Windows . .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. . 17

Docking Windows .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 18

ix

Page 11

Floating Windows . .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 19

Tabbed Windows . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. 20

Closing and Opening Windows . .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. . 21

Modifying Environment Settings after Setup .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 22

Exporting Selected Environment Settings . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . 23

Importing Selected Environment Settings . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . 24

Resetting All Settings . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. . 28

Familiarization with Visual Studio Project Types . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. . 30

Windows Projects . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . 32

Web Projects . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. 33

Office Projects . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . 34

SharePoint Projects . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . 34

Database Projects . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. . 34

Summary . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. 34

2

Learning Just Enough C# or VB.NET: Basic Syntax . . . . .. .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . 35

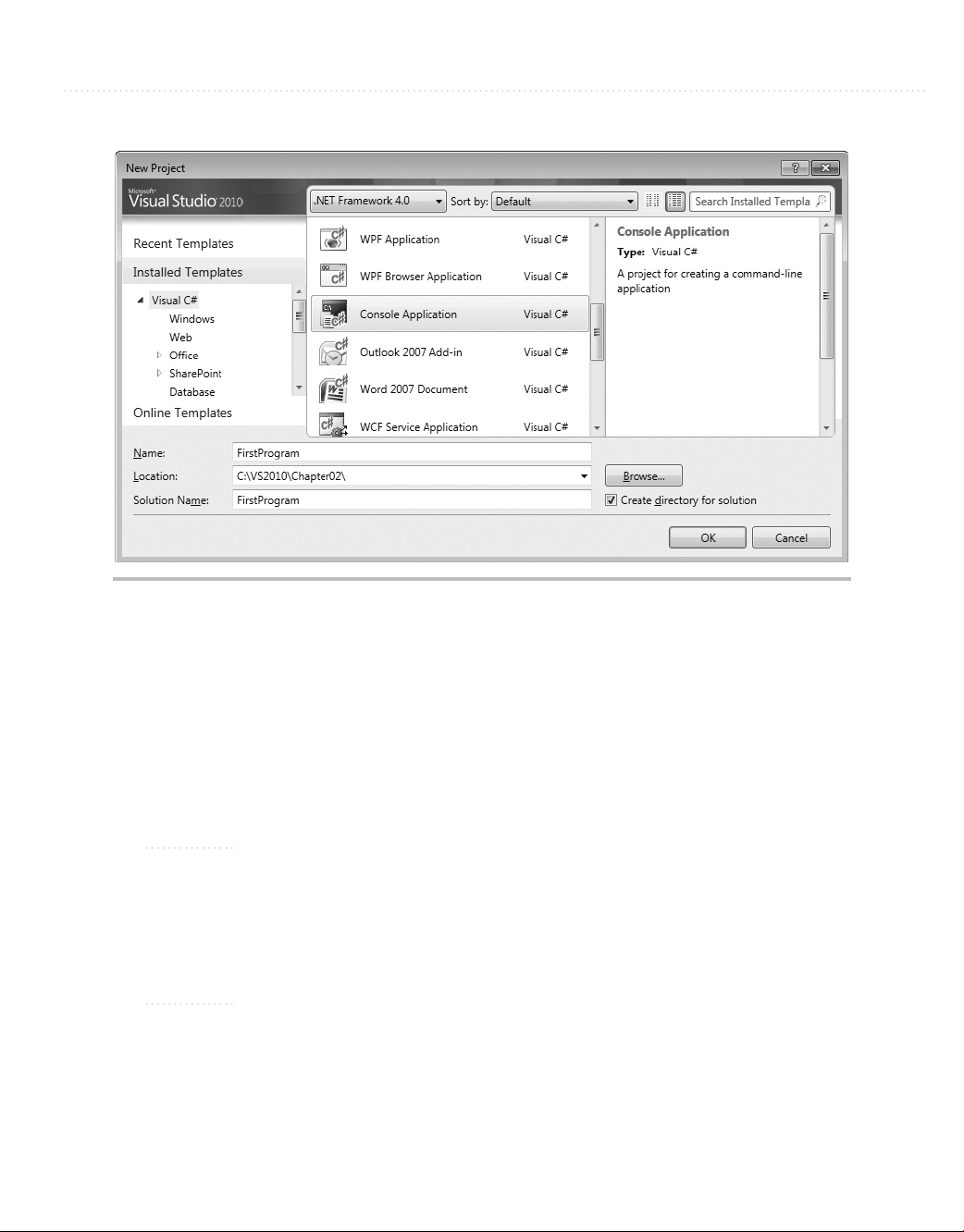

Starting a Bare-Bones Project . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. 36

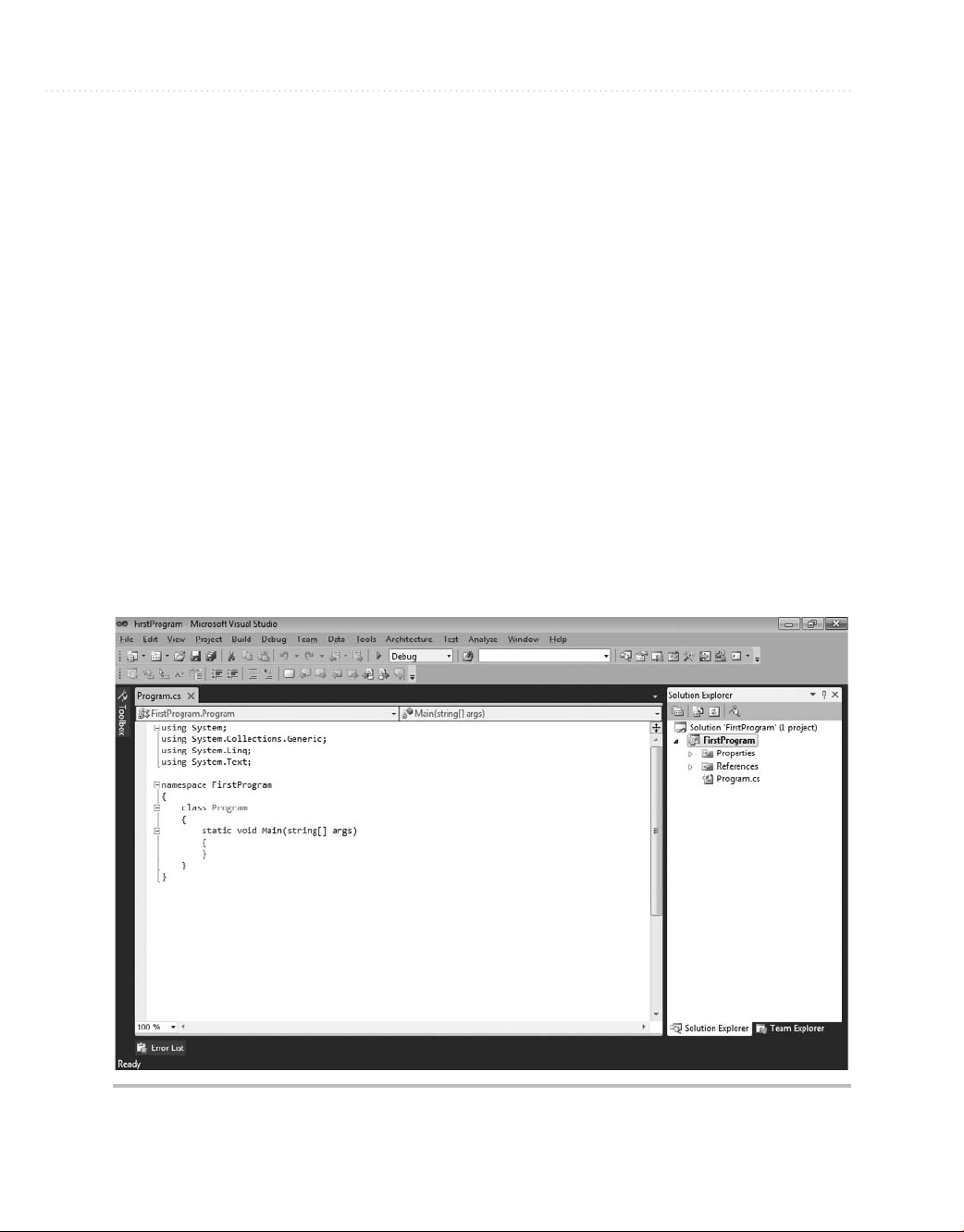

Examining the Code Skeleton .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . 39

The Main Method . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . . 40

The Program Class . . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. 41

The FirstProgram Namespace . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . . 42

An Overview of the VS Code Editor .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. 43

Class and Member Locators . .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . 4

Bookmarks .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . 44

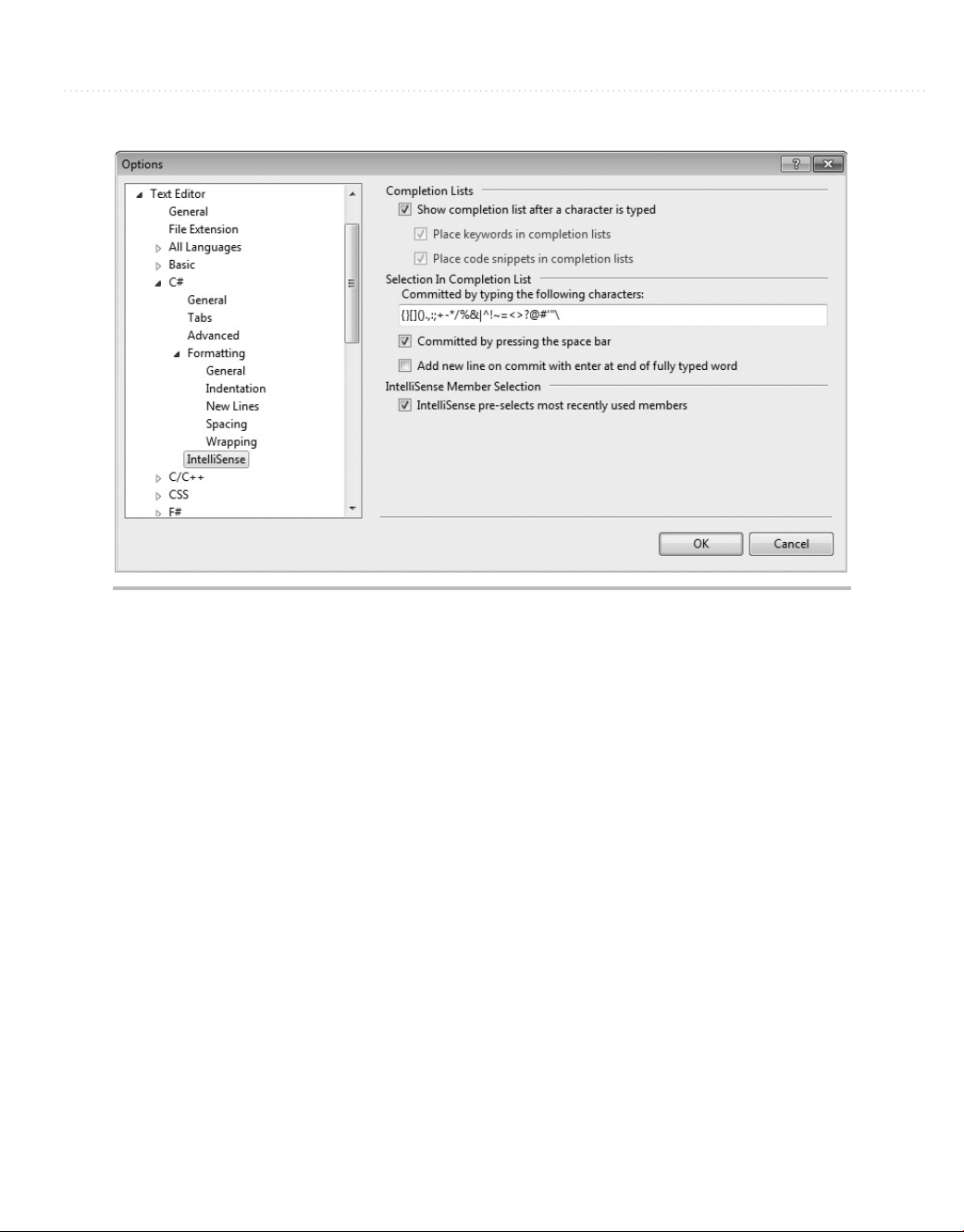

Setting Editor Options .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. 45

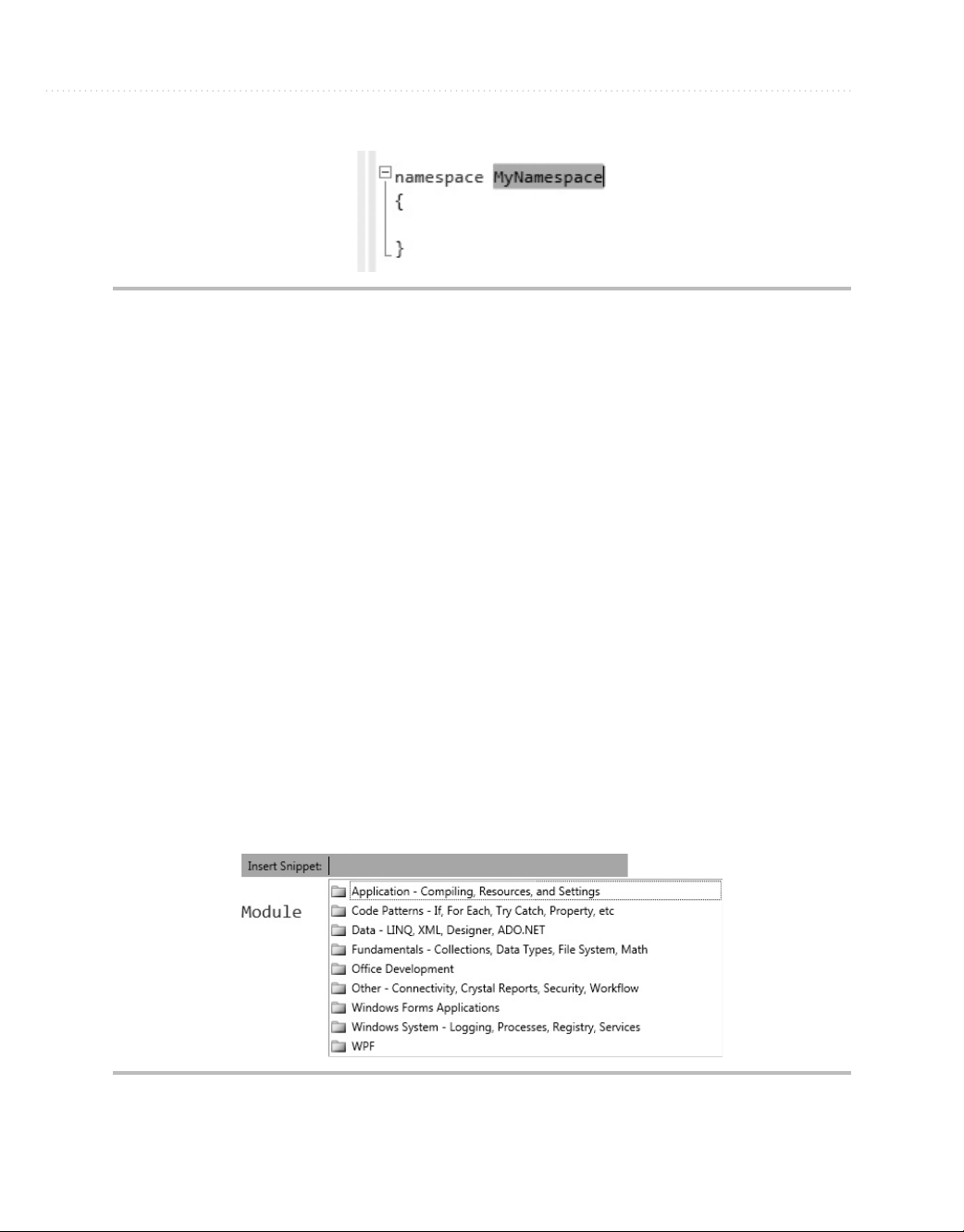

Saving Time with Snippets . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. 47

Coding Expressions and Statements .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. 49

Making Intellisense Work for You . .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . 49

Running Programs . .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. . 51

Primitive Types and Expressions . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . 52

Enums .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 55

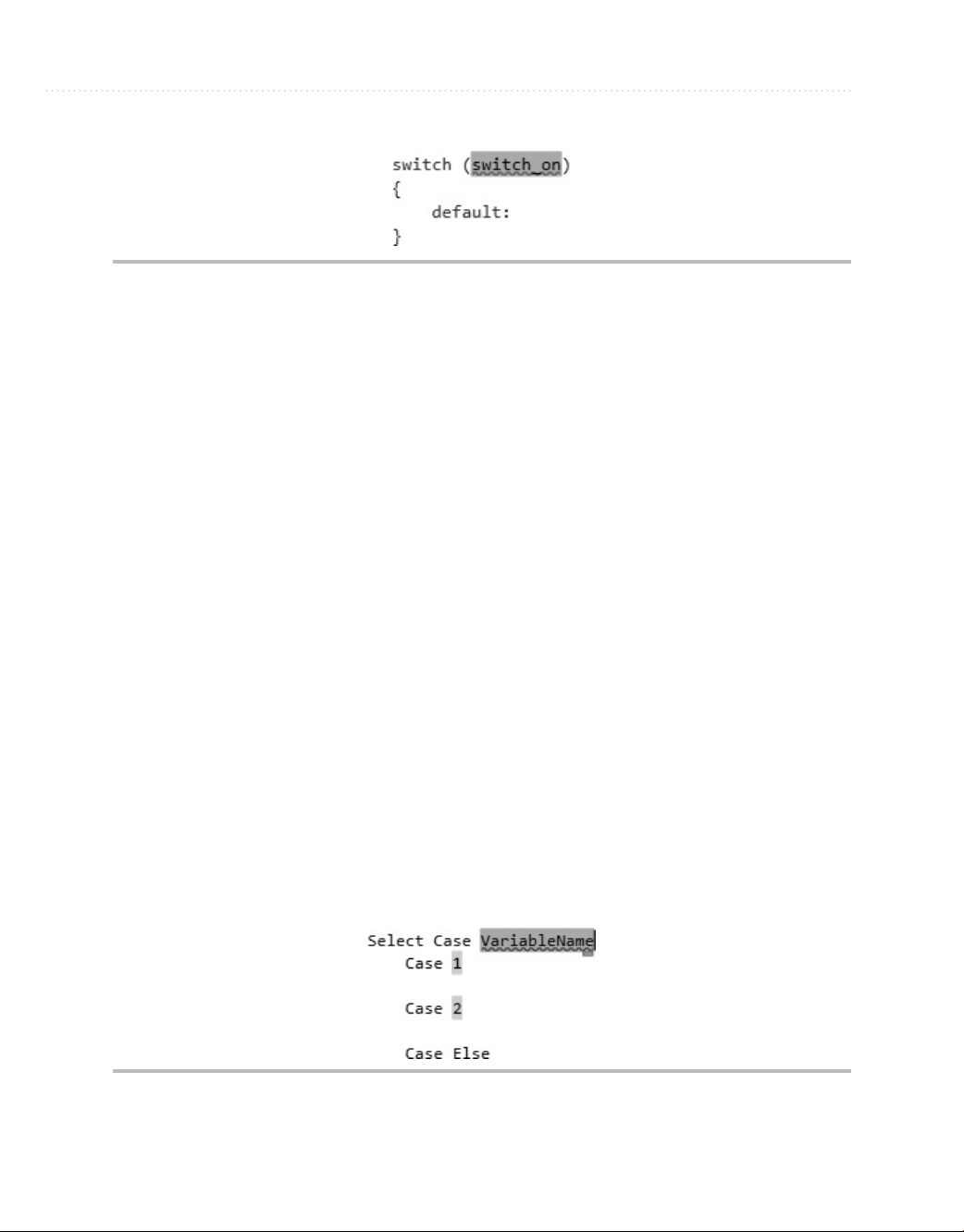

Branching Statements . .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. 57

Loops . .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. . 61

Summary . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. 66

4

3

Learning Just Enough C# and VB.NET: Types and Members . .. .. . . .. . . . 67

Creating Classes . . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. . 68

Class Syntax . .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. . 68

Class Inheritance . .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. 70

The class Snippet . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . 71

Writing Methods . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. 72

Declaring and Using a Method . .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. . 72

Declaring Parameters and Passing Arguments . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . 75

Page 12

Contents xi

Returning Data and Using Method Results .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. 78

Method Snippets . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. 80

Coding Fields and Properties . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. . 81

Declaring and Using Fields . .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . 81

Declaring and Using Properties . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 83

The Property Snippet . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. 86

Summary . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. 87

4

Learning Just Enough C# and VB.NET: Intermediate Syntax . . .. .. . . . .. 89

Understanding Delegates and Events . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . 90

Events . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. . 91

Delegates . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. 94

Event, Delegate, and Handler Code Completion . .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. 95

Implementing Interfaces .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. 96

Creating an Interface . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . 97

Making Classes Implement the Interface .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . 98

Writing Code That Uses an Interface .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. . 101

The interface Snippet .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . 106

Applying Arrays and Generics . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . 107

Coding Arrays .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . 107

Coding Generics . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 109

Summary . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. 110

PART II

5 Creating and Building Projects . . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . 113

Learning the VS 2010 Environment

Constructing Solutions and Projects .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. . 114

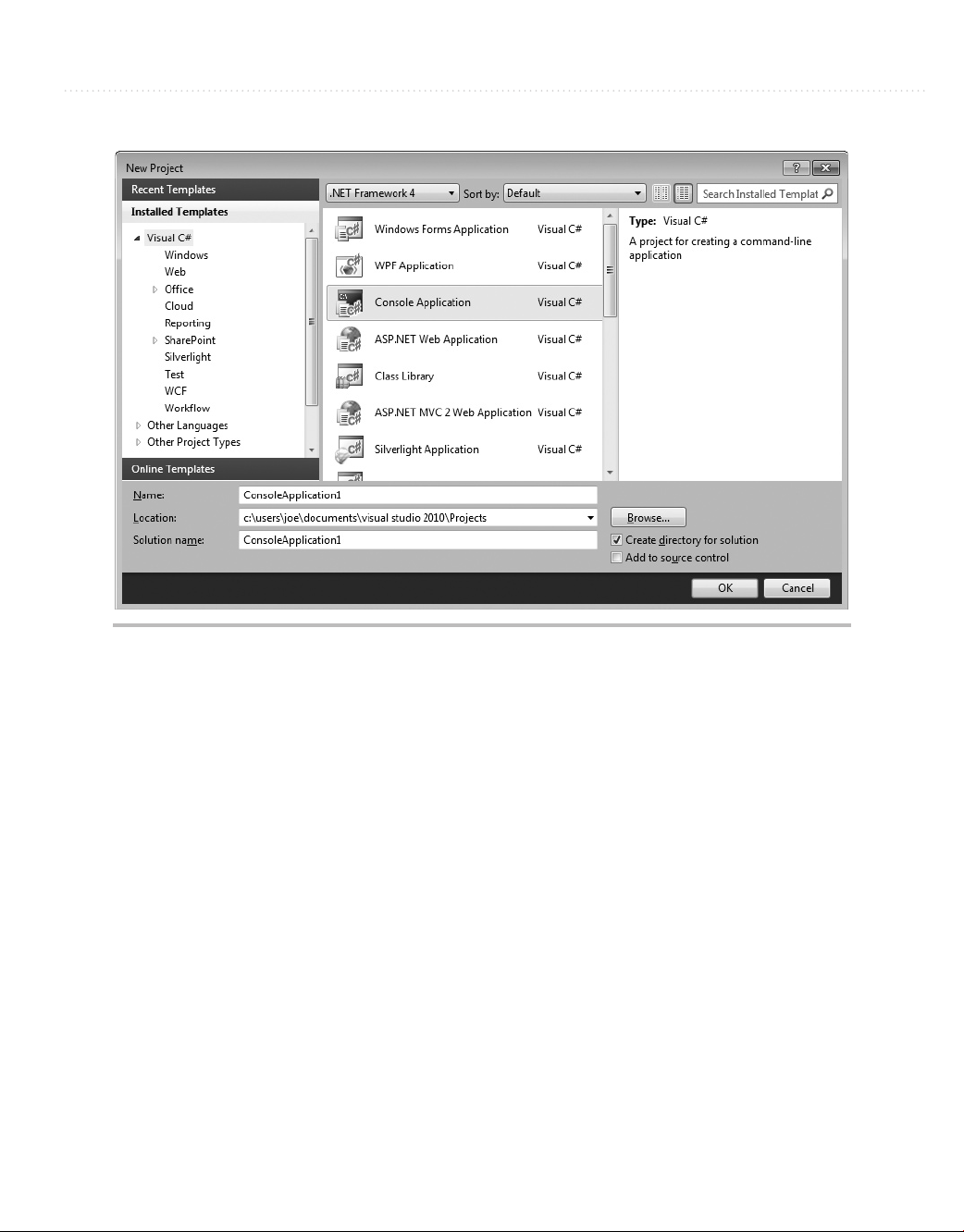

Creating a New Project . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. 115

Navigating the Solution Explorer . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. . 116

Examining Property Settings .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . 118

Assembly Name . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. 119

Default Namespace . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. 119

Target Framework .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. 119

Output Type .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 119

Startup Object .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . 120

Icon and Manifest . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. 120

Assembly Information .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 121

Referencing Assemblies .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. . 122

Adding a .NET Assembly Reference .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 123

Managing Assembly References . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. . 124

Referencing Your Own Class Libraries . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. . 125

Using Code in Class Libraries . .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. 126

Page 13

Compiling Applications . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 129

Building Solutions/Projects .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . 129

Rebuilding Solutions/Projects .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. 130

Cleaning Solutions/Projects . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 130

Managing Dependencies and Build Order . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. 131

Managing Compilation Settings .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. . 133

Navigating a Project with Class View .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . . 136

Using the Class Designer . . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. 137

Class Designer Visualization . .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. 137

Class Designer Code Generation . .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . . 138

Summary . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. 141

6

Debugging with Visual Studio . . . .. . . .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . 143

Example Code for This Chapter .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. . 144

Development-Time Code Tools . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . 148

Configuring Debug Mode . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 150

Setting Breakpoints . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 155

Creating a Breakpoint . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. . 156

Customizing a Breakpoint . .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . . 157

Managing Breakpoints . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . 158

Stepping Through Code . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . 158

Inspecting Application State . . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . 160

Locals and Autos Windows . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. . 16

Watch Windows . .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . 161

The Immediate Window . .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. . 162

The Call Stack Window . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. 163

The Quick Watch Window . .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . . 163

Watching Variables with Pin To Source .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. 164

Working with IntelliTrace . . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. 165

Solving Problems with VS Debugger . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . 166

A Program with Bugs .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. . 167

Finding the Bug . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. . 171

Fixing the First Bug . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . 174

Debugging and Resolving NullReferenceException Problems .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . 175

Summary . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. 180

0

7

Working with Data . . .. .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . 181

Working with Databases .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. 182

Introduction to Server Explorer . .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . . 182

Creating a Database . .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. . 183

Adding Tables . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . . 185

Relating Tables with Foreign Keys . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. . 187

Adding Stored Procedures . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . 192

Configuring Database Options .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. 193

Page 14

Contents xiii

Learning Language Integrated Query (LINQ) . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. 194

Querying Object Collections with LINQ . .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. 194

Creating a LINQ Projection with Anonymous Types . .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. . 198

Using LINQ to Sort Collection Results . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . 199

Handling Data with LINQ to SQL .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. 200

Setting Up LINQ to SQL . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . 200

Working with the LINQ to SQL Designer . .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. 201

Introduction to Querying LINQ to SQL . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 203

Performing Queries on Multiple Tables . .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 205

Inserting Data with LINQ to SQL .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . 210

Updating Data with LINQ to SQL .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . 211

Deleting Data with LINQ to SQL . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. 212

Summary . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. 214

PART III

8 Building Desktop Applications with WPF . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . . . 217

9

Building Programs with VS 2010

Starting a WPF Project . .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. 218

Understanding Layout . .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . 220

Grid Layout . .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. . 220

StackPanel Layout . .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. . 222

DockPanel Layout . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. . 223

WrapPanel Layout .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 224

Canvas Layout . .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 225

Using WPF Controls

Managing Windows for Controls . .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. 226

Setting Properties . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. . 228

Handling Events . . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . . 228

Coding Event Handlers . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. . 233

Working with Data in WPF . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 234

Setting Up a Data Source . .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. . 235

Configuring a ComboBox . .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. . 241

Reading and Saving Data .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . 243

Using the DataGrid .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . 244

Summary . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. 247

.. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. 226

Creating Web Applications with ASP.NET MVC . .. . . .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . . 249

Understanding ASP.NET MVC .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. 250

Starting an ASP.NET MVC Project .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . 251

Creating the Models . .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . . 254

Building Controllers . .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . 254

Displaying Views . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. . 256

Looking Inside a View . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. . 256

Organizing View Files . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. . 258

Page 15

Assigning MasterPage Files . . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. 258

Partial Views (a.k.a. User Controls) .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . 260

Managing Routing . .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. . 262

Building a Customer Management Application . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . 264

Creating a Repository .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . . 265

Creating a Customer Controller . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. 268

Displaying a Customer List .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. . 269

Adding a New Customer .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 274

Updating Existing Customers . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. 279

Deleting a Customer . .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . . 281

Summary . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. 284

10

Designing Silverlight Applications . . . . .. .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . 285

Starting a Silverlight Project .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . 286

Navigating the Silverlight Designer . .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. . 290

Using Silverlight Controls . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. 290

Running Silverlight Out-of-Browser (OOB) . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . 294

Deploying Silverlight Applications . .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . 297

Summary . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. 298

11

Deploying Web Services with WCF . . .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . 299

Starting a WCF Project . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 301

Specifying a Contract with WCF Interfaces . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . 302

Implementing Logic with WCF Classes . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. ..

Hosting a WCF Service . .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. 314

Following General Hosting Procedures . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. 315

Installing IIS 7 on Windows 7 .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. . 315

Creating a Web Site on IIS 7 on Windows 7 . .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 317

Deploying the WCF Service to IIS . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. . 321

Communicating with a WCF Service . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . . 326

Creating a Service Reference . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. 326

Coding Web Service Calls . .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . 329

Deploying a Client That Consumes a Web Service . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. . 336

Creating a Web Service in a Web Site . .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. 337

Summary . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. 338

308

PART IV

12 Customizing the Development Environment . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . 341

Enhancing the VS 2010 Experience

Implementing Custom Templates . .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. . 342

Creating New Project Templates .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . 343

Creating New Item Templates . .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. 347

Creating Custom Snippets . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . 353

Creating a New Snippet . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. 353

Managing the Snippet Library . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . . 358

Page 16

Contents xv

Writing Macros . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . 360

Recording a Macro . .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. 360

Saving a Macro . .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. 364

Editing Macros .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . 365

Summary . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. 370

13

Extending Visual Studio 2010 . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . . 371

Creating a Visual Studio Add-In .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . 372

Running the Add-In Project Wizard . . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . 372

Examining an Add-In Wizard Solution . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . 377

Drilling into the Connect Class . .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. 378

Adding Functionality to an Add-In .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. 383

Reviewing the OnConnection Method . .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 384

Implementing the Exec Method . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. 391

Setting Status with QueryStatus .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. 395

Deploying an Add-In . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. . 397

Where to Go Next . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . 399

Summary . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. 4 00

PART V

A Introduction to XML . .. .. . . . .. .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . 403

B

Appendixes

VS 2010 XML Editor .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. . 404

XML Prefixes .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. 404

XML Elements . . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. 405

Attributes . .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. . 405

Namespaces .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. 406

The XML Menu . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . 407

Configuring XML Options . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. . 407

Summary . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. 407

Introduction to XAML .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . 409

Starting a WPF Project . .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. 410

Elements as Classes . .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. 411

Attributes as Properties . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. . 411

Executing the XAML Document .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. 411

Property Elements .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. 412

Markup Extensions .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. 414

Summary . .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. 416

Index .. .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. .. . . .. . . .. . . . .. . 417

Page 17

This page intentionally left blank

Page 18

Acknowledgments

work of this magnitude is never the ramblings of a single author, but a successful

combination of dedication from a team of highly skilled professionals. I would like

A

to personally thank several people who helped make this book possible.

Jane Brownlow, Executive Editor, helped kick off the book and got it started on the

right path. Megg Morin, Acquisitions Editor, took the reins from Jane and led the rest

of the way. Joya Anthony, Acquisitions Coordinator, helped keep the flow of chapters

moving. Madhu Bhardwaj, Project Manager, and Patty Mon, Editorial Supervisor, helped

coordinate copy edits and final layout. I would really like to thank you all for your

patience and assistance. There are many more people at McGraw-Hill who helped put this

book together, and I am appreciative of their contributions and professionalism.

Roy Ogborn was the technical editor for this book. I’ve known Roy for several years

and was delighted when he agreed to tech edit the book. Besides catching many of my

errors, Roy provided valuable insight that made a difference in several areas, continuously

asking the question of whether a beginner would understand a concept, what is the proper

application of the language to accomplish a goal, and perspective on what parts of a

technology needed emphasis. Thanks to Roy for outstanding technical editing and advice.

xvii

Page 19

This page intentionally left blank

Page 20

Introduction

isual Studio has been the primary integrated development environment (IDE) for

Microsoft software development for several years. Visual Studio 2010 (VS), the

V

subject of this book, is therefore a mature evolution, building upon the success of its

predecessors. This book will show you how to leverage Visual Studio 2010 to your

advantage, increasing your skill set, and helping you become more productive in building

software. The software you will learn to write will be for .NET (pronounced “Dot Net”),

which is a Microsoft platform for writing different types of applications.

As the title suggests, this is a book for beginners. However, there are many opinions

about who a beginner is, so let’s discuss what beginner means in the context of this book.

You should probably have some understanding of what programming is from a general

perspective. It would help to have at least written a batch file, macro, or script that

instructed the computer to perform some task. A beginner could also be someone who

has written software with technology, such as Cobol, Dreamweaver, or Java, but who is

unfamiliar with Visual Studio. Whatever your background, this book provides a gradual

on-ramp to developing applications with Visual Studio 2010.

xix

Page 21

This book has 13 chapters and is divided into four parts and a couple of appendixes as

reference material. The following provides an overview of each section:

● Part I: Understanding Visual Studio 2010 Essentials Chapter 1 begins with an

explanation of what VS is, its benefits to you, and what type of applications VS will

help you build. Hands-on guidance starts at the point of installation, giving you tips

as to what is being installed and where it goes on your computer. Chapters 2 through

4 are an introduction to C# and VB, two of the most widely used programming

languages supported in VS. Notice that the titles of these chapters include “Just

Enough,” indicating that you will learn the language features you need throughout

this book. As you progress through the book, you’ll be exposed to all of the language

features discussed and see how they are used. Even if you already know how to

program, you might want to peruse the programming language chapters anyway

because I’ve sprinkled in dozens of valuable tips that will make your coding

experience in VS much more pleasurable.

● Part II: Learning the VS 2010 Environment There are a few universal tasks most

developers perform every day, which include working with projects, debugging code,

and manipulating data. While Chapter 5 is titled “Creating and Building Projects,”

there is much involved when working with projects. Pay particular attention to the

guidance on assemblies and class libraries, as they tend to become more prominent

as your development activities progress beyond simple programs. Regardless of your

development philosophy, the need to fix bugs has always existed and will continue

to be important in the future. Chapter 6 is designed to help you use the many tools of

VS to find and fix bugs. Another common task you’ll have is working with data. VS

allows you to create databases, add tables, and much more. When the database is ready

to use, you’ll learn how to write code that works with the database. I chose to cover

LINQ to SQL because it’s one of the simpler database technologies, yet powerful

enough for professional application development.

● Part III: Building Programs with VS 2010 With the foundations of programming

languages and a feel for the VS environment, you’ll be ready to use VS to build

applications. The .NET platform supports various technologies, and this book takes

a forward-looking approach, choosing technologies that were the most recently

introduced. The focus in these chapters is not to teach you everything about these

technologies, which can fill entire books themselves, but rather to show you how to

leverage VS in building applications. You’ll get the foundations that will give you a

head start in building your own applications. Both Chapters 8 and 10 use a form of

Page 22

Introduction xxi

Extensible Markup Language (XML) called XML Application Markup Language

(XAML). Considering that this is a beginner’s book, I added a couple of appendixes

that cover XML and XAML. I recommend that you read the appendixes before

reading Chapters 8 and 10. Additionally, you should read Chapter 8 before reading

Chapter 10, because many of the same concepts used to work with Windows

Presentation Foundation (WPF), a technology for building desktop applications,

are applicable to Silverlight, a technology to build Web applications. The other two

chapters in this part will show you how to build Web applications with ASP.NET

MVC and how to create Web services with Windows Communications Foundation.

● Part IV: Enhancing the VS 2010 Experience In addition to all of the wizards,

tools, and editing help that VS offers, you can extend VS to make it work even better.

Chapter 12 shows you how to create your own project and project item wizards, how

to create code snippets that automatically generate code, and how to create macros

that automate the VS environment. If the macro capability you learn about in VS

isn’t powerful enough, read Chapter 13, which shows you how to build an Add-In,

a program that you can install to add new features to VS.

From installation to customization of the IDE, VS is a helpful and powerful tool.

I hope you enjoy this book and that it helps you learn how to make VS work for you.

Page 23

This page intentionally left blank

Page 24

Part I

Understanding Visual

Studio 2010 Essentials

Page 25

This page intentionally left blank

Page 26

Chapter 1

Introducing Visual Studio 2010

3

Page 27

4 Microsoft Visual Studio 2010: A Beginner’s Guide

Key Skills & Concepts

● Learn What Visual Studio 2010 Can Do for You

● Install and Choose Among Installation Options

● Understand What Types of Applications You Can Build

our first experience with Visual Studio (VS) 2010 is often installation. As with most

software, VS is rather easy to install; this chapter describes the installation process

Y

and gives you tips to help understand available options. Once installation is complete,

you’ll open VS for the first time and need to know how to navigate the VS environment;

this chapter gives you a high-level view of how VS is organized, how to find the features

you need, and how to work with windows. Finally, you’ll learn how to find the different

application types that VS helps you build. At this point, you know that VS will help you

build .NET applications, but let’s start off with a more detailed explanation of what VS

will do for you.

What Is Visual Studio 2010 About?

Visual Studio 2010 (VS) is an integrated development environment (IDE); a set of tools

in a single application that helps you write programs. Without VS, you would need to

open a text editor, write all of the code, and then run a command-line compiler to create

an executable application. The issue with the text editor and command-line compiler is

that you would lose a lot of productivity through manual processes. Fortunately, you have

VS to automate many of the mundane tasks that are required to develop applications. The

following sections explain what VS will do for you and why VS is all about developer

productivity.

Automatically Generated Code

VS includes a suite of project types that you can choose from. Whenever you start a new

project, VS will automatically generate skeleton code that can compile and run immediately.

Each project type has project items that you can add, and project items include skeleton

code. In the next chapter, you’ll learn how to create projects, add project items, and view

Page 28

Chapter 1: Introducing Visual Studio 2010 5

automatically generated code. VS offers many premade controls, which include skeleton

code, saving you from having to write your own code for repetitive tasks. Many of the more

complex controls contain wizards that help you customize the control’s behavior, generating

code based on wizard options you choose.

Rapid Coding Experience

The VS editor optimizes your coding experience. Much of your code is colorized; you

have Intellisense, tips that pop up as you type; and keyboard shortcuts for performing a

multitude of tasks. There are a few refactorings, features that help you quickly improve

the organization of your code while you’re coding. For example, the Rename refactoring

allows you to change an identifier name where it is defined, which also changes every

place in the program that references that identifier. VS introduces even more features,

such as a call hierarchy, which lets you see the call paths in your code; snippets, which

allow you to type an abbreviation that expands to a code template; and action lists for

automatically generating new code.

Everything at Your Fingertips

You’ll really want to learn how to navigate the VS environment because a plethora of

tools are available to aid you in your quest to rapidly create quality software. Y

the Toolbox jam-packed with controls, a Server Explorer for working with operating

system services and databases, a Solution Explorer for working with your projects, testing

utilities, and visual designers. By the way, there are compilers too.

ou have

Customizability and Extensibility

You can customize many parts of the VS environment, including colors, editor options,

and layout. The options are so extensive that you’ll need to know where to look to find

them all. If the out-of-the-box VS development environment doesn’t offer a feature you

need, you can write your own macros to automate a series of tasks you find yourself

repeating. For more sophisticated customization, VS exposes an application programming

interface (API) for creating add-ins and extensions. Several third-party companies

have chosen to integrate their own applications with VS. For example, Embarcadero’s

Delphi language and development environment is hosted in Visual Studio. The rich and

customizable development environment in VS helps you work the way you want to.

As you move through this book, keep these important concepts in mind and look for

all of the tips that will help you use VS to your advantage. Your first step in using VS will

be installation, which is discussed in the next section.

Page 29

6 Microsoft Visual Studio 2010: A Beginner’s Guide

Installing Visual Studio 2010

Hopefully the preceding discussion whets your appetite on what VS can do for you. If

you haven’t already installed VS, this section walks you through the setup process. The

guidance along the way will explain how to choose among available options to customize

the installation to your needs. The following steps explain how to install VS:

System Requirements

As of this writing Microsoft recommends you have a 32-bit x86 or 64-bit (x64) CPU,

at least 1GB RAM, a 5400 RPM hard disk drive, 3GB hard disk space, DVD-ROM,

DirectX video at 1280 × 1024 resolution, and a 1.6 GHz processor. Recommended

operating systems include

SP2 or later (all versions except for Starter), Windows 7 (only Ultimate at the time this

chapter was written), Windows 2003 (SP1 or R2 or later), and Windows 2008 (SP1 or

R2 or later). Be sure to check Microsoft Developer Network (MSDN) online, as system

requirements can change over time.

Windows Vista (all versions except for Starter), Windows XP

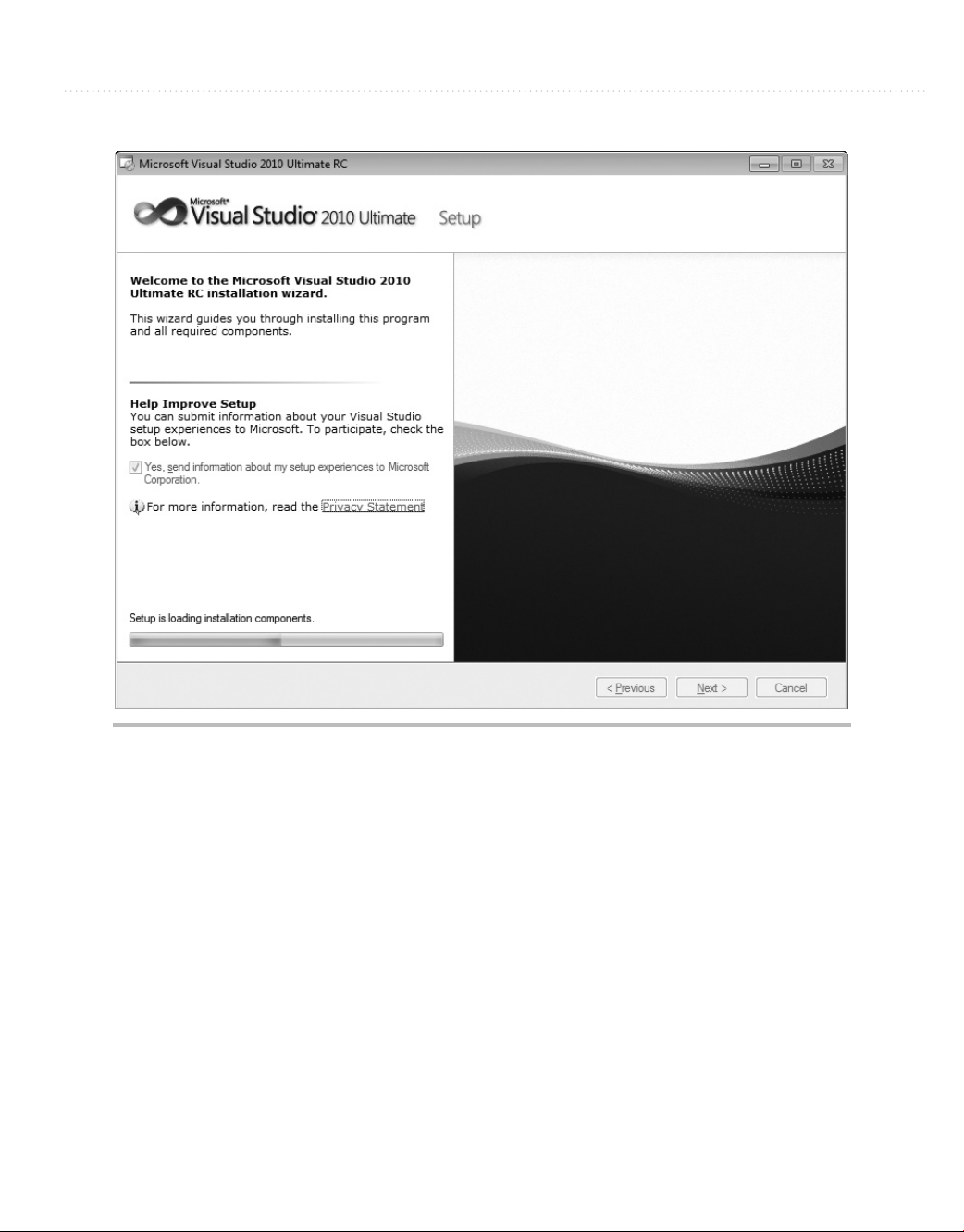

1. When you first place the VS DVD into the drive, you’ll see the Microsoft Visual Studio

2010 window, shown in Figure 1-1. Available options are to Install Microsoft Visual

Studio 2010 and Check For Service Releases. Click Install Microsoft Visual Studio 2010.

Figure 1-1 Microsoft Visual Studio 2010 Setup window

Page 30

Chapter 1: Introducing Visual Studio 2010 7

Figure 1-2 Setup Welcome window

2. The next window you’ll see, Figure 1-2, is the welcome window, titled Microsoft Visual

Studio 2010. Figure 1-2 shows that I’m installing the Ultimate version. Installation for

other versions is similar, but the number of features available to install varies.

If you check the box on this page in the Help Improve Setup section, the installer

will gather logs produced during the setup process and send them across the Internet

to Microsoft after the setup is complete. To help you make an informed choice as to

whether to check this box, there is a Privacy Statement link under the check box to

click and read if you would like more information about what Microsoft does with

setup information. When you’re ready, click Next. After setup components are loaded,

you’ll see the licensing screen in Figure 1-3.

Page 31

8 Microsoft Visual Studio 2010: A Beginner’s Guide

Figure 1-3 Setup Licensing window

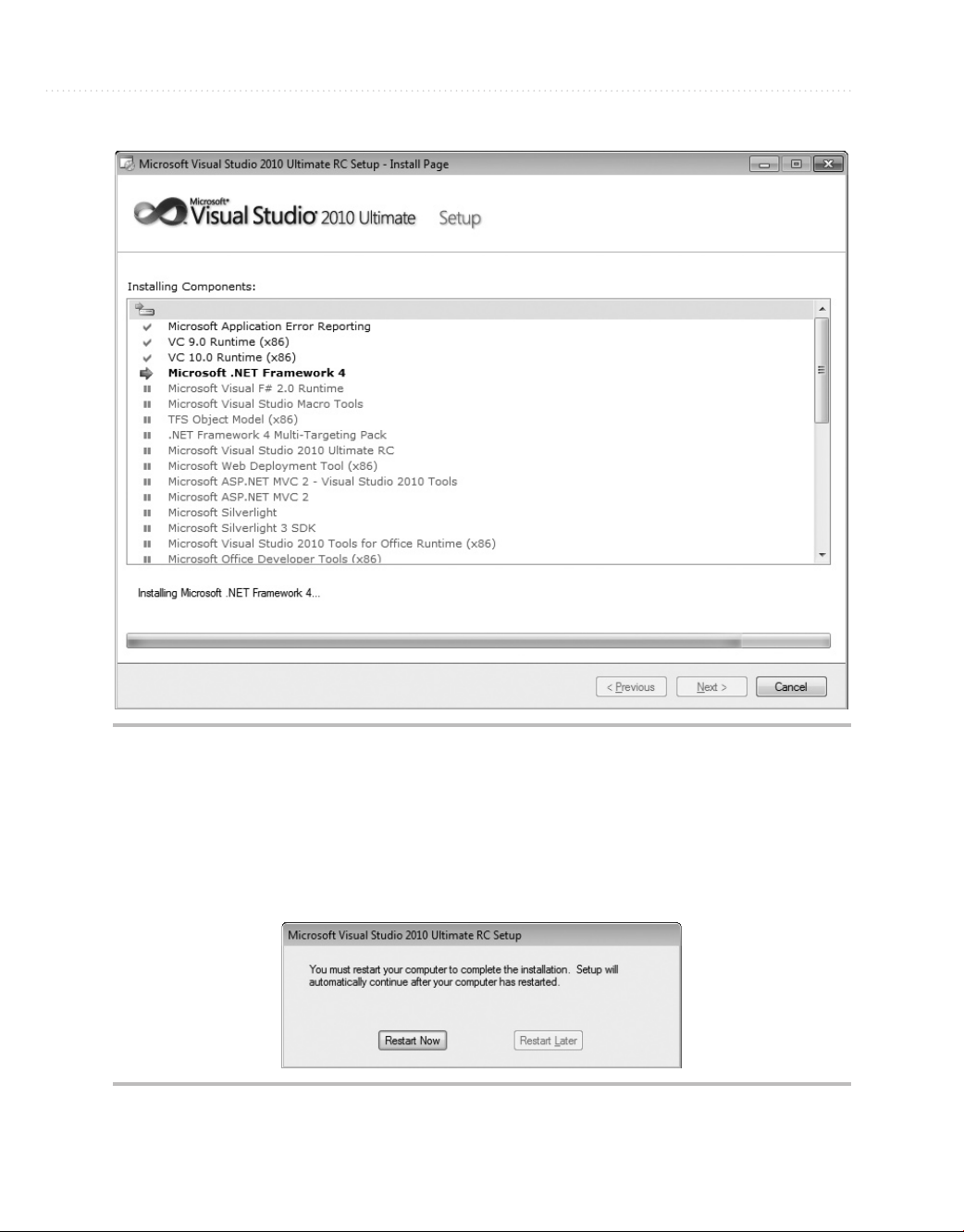

3. In Figure 1-3, you’ll see what components will be installed. You’ll need to read the VS

license to ensure you understand what the terms are. The licensing terms can differ,

depending on what type of package you acquired and your particular country or region.

Once you’ve read the license, you’ll need to check “I have read and accept the license

terms” to proceed. Next, enter the license key that comes with your software and enter

your name. The installer will automatically fill in the product key if you downloaded

VS via Microsoft Developer Network (MSDN). Click Next and you’ll see options for

customizing product installation.

4. Figure 1-4 lets you choose between full and custom installation. If you click the

Custom option, you’ll be able to choose precisely which components should be

installed. This is a good opportunity to uncheck the items you won’t ever use. If this is

Page 32

Chapter 1: Introducing Visual Studio 2010 9

Figure 1-4 Setup Customization window

your first installation and you have plenty of storage, you might want to go through the

list and check everything to take a look at what is available. You can always return to

this installation later and make adjustments.

The configuration screen in Figure 1-4 shows that you can also change the location of

where to install VS. Take note of the installation location because this is where you will

go to find sample code, common assemblies, and more items affecting the development

environment. Evaluate the disk space requirements to ensure you have enough available

storage. You’ve now completed the configuration options for installation. Click Install to

start the installation. You’ll see a screen similar to Figure 1-5 during the installation process

where the small check marks indicate which VS components have successfully installed.

Page 33

10 Microsoft Visual Studio 2010: A Beginner’s Guide

Figure 1-5 Setup Progress window

5. During the installation, the VS installer will need to reboot your computer, showing the

restart message in Figure 1-6. Make sure you close any applications you currently have

open so that you don’t lose your work, and then click Restart Now.

Figure 1-6 Setup Restart window

Page 34

Chapter 1: Introducing Visual Studio 2010 11

Figure 1-7 Setup Success window

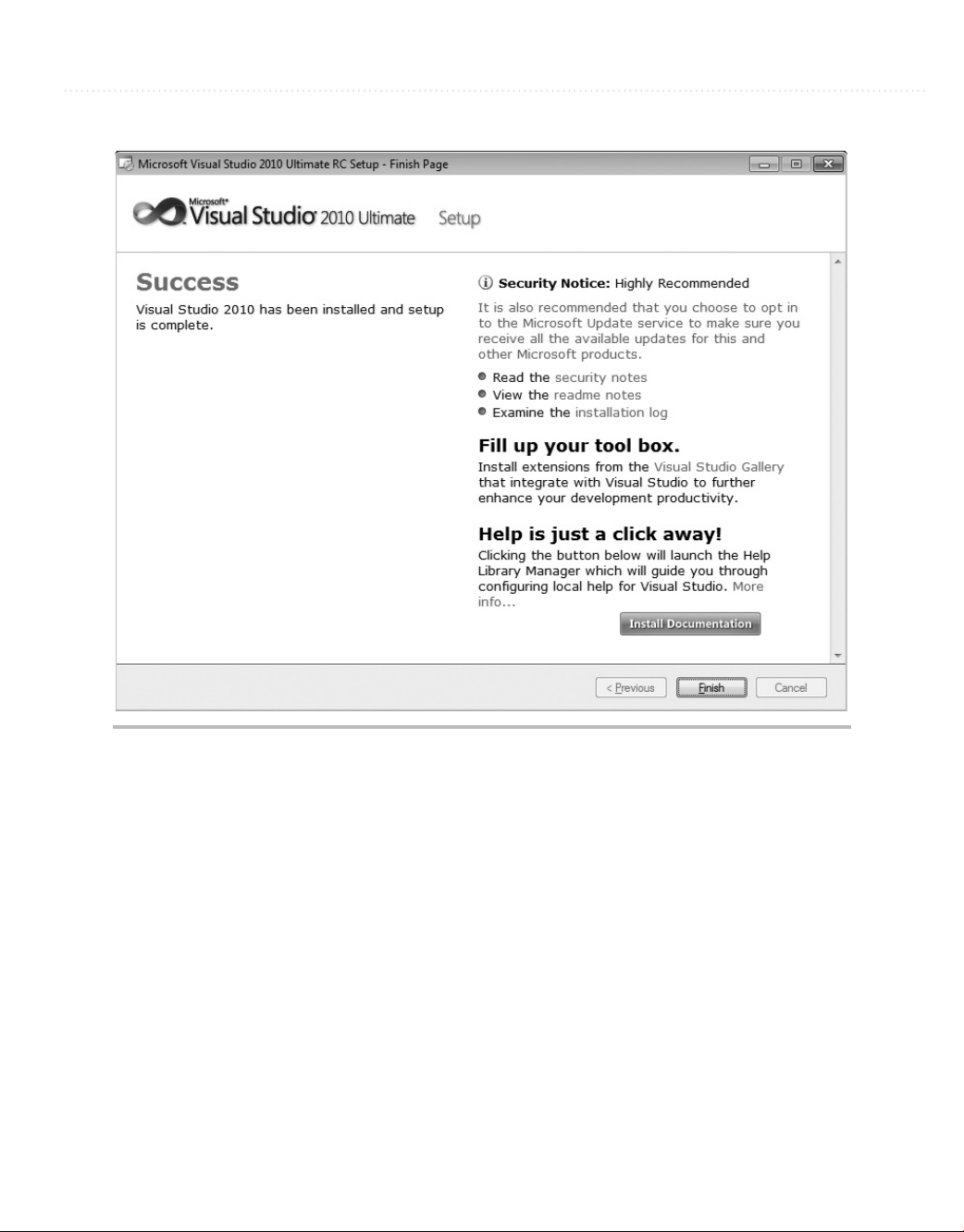

6. When installation completes without error, you’ll see the Success window, shown in

Figure 1-7. If you have errors during installation, this window will give you guidance

on what to do to solve the problem.

Your installation is now almost complete. You can install product documentation by

clicking the Install Documentation button, shown in Figure 1-7. The initial installation

screen that appeared when beginning the installation will reappear, as shown in Figure 1-8.

You should also check for service releases; not only for the updated functionality to VS,

but also because service releases often include important security updates.

You are now ready to run VS for the first time. At that point, you’ll need to perform

one more easy configuration step, where you will choose your default environment

settings, as shown in Figure 1-9.

Page 35

12 Microsoft Visual Studio 2010: A Beginner’s Guide

Figure 1-8 Checking for service releases

Figure 1-9 Default Environment Settings window

Page 36

Chapter 1: Introducing Visual Studio 2010 13

The choice you make for default environment settings depends a lot on what

language or environment you’ll use to write software in. The environment settings

choice isn’t locked in stone and can be reset if you decide you don’t like the settings.

A later section of this chapter, “Modifying Environment Settings after Setup,” explains

how to change environment settings. This book covers both VB and C#, so you would

most likely want to choose the setting specific to the language you will use. The

examples in this book will use either VB or C# settings, depending on the topic. The

choice of settings determines how VS will lay out the windows and the default options

that are set throughout the VS IDE.

NOTE

C# or VB, which Should I Choose? Both C# and VB are first-class languages on the

.NET platform. The languages themselves are stripped down to bare syntax, with all

additional services moved into the .NET Framework Class Library, which is common

to all languages. There are a few small differences between the languages, but in

reality, the choice really comes down to personal preference. In practice, knowing

both languages is an advantage because much has been written in articles and books

showing how to use .NET techniques that doesn’t depend on which language was

used. You’ll not want to miss out on excellent content regardless of the language it is

written in.

You should now have a good installation with the configuration and environment

settings of your choosing. With VS open for the first time, the next section describes the

high-level parts of the Start page.

Navigating the Visual Studio 2010 Environment

This section is a high-level view of VS, describing what is available when you first

start Visual Studio 2010, also known as the Visual Studio integrated development

environment, commonly known as the IDE, which is pronounced by saying the letters

I-D-E. Seeing what is available will help you find features more quickly. Additionally,

knowing what is available by default will help you differentiate between default

functionality and the context-sensitive features of the software items you’re working on.

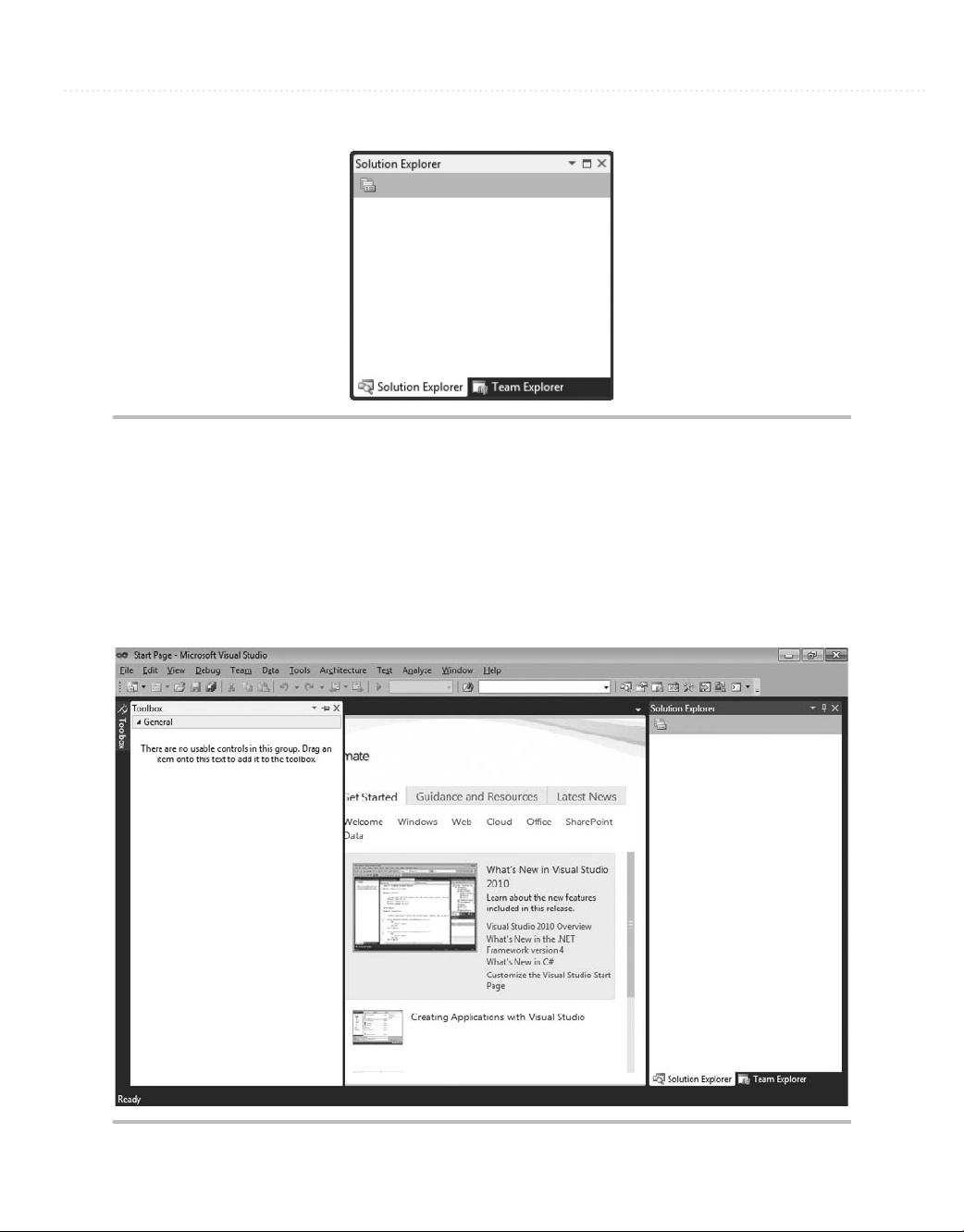

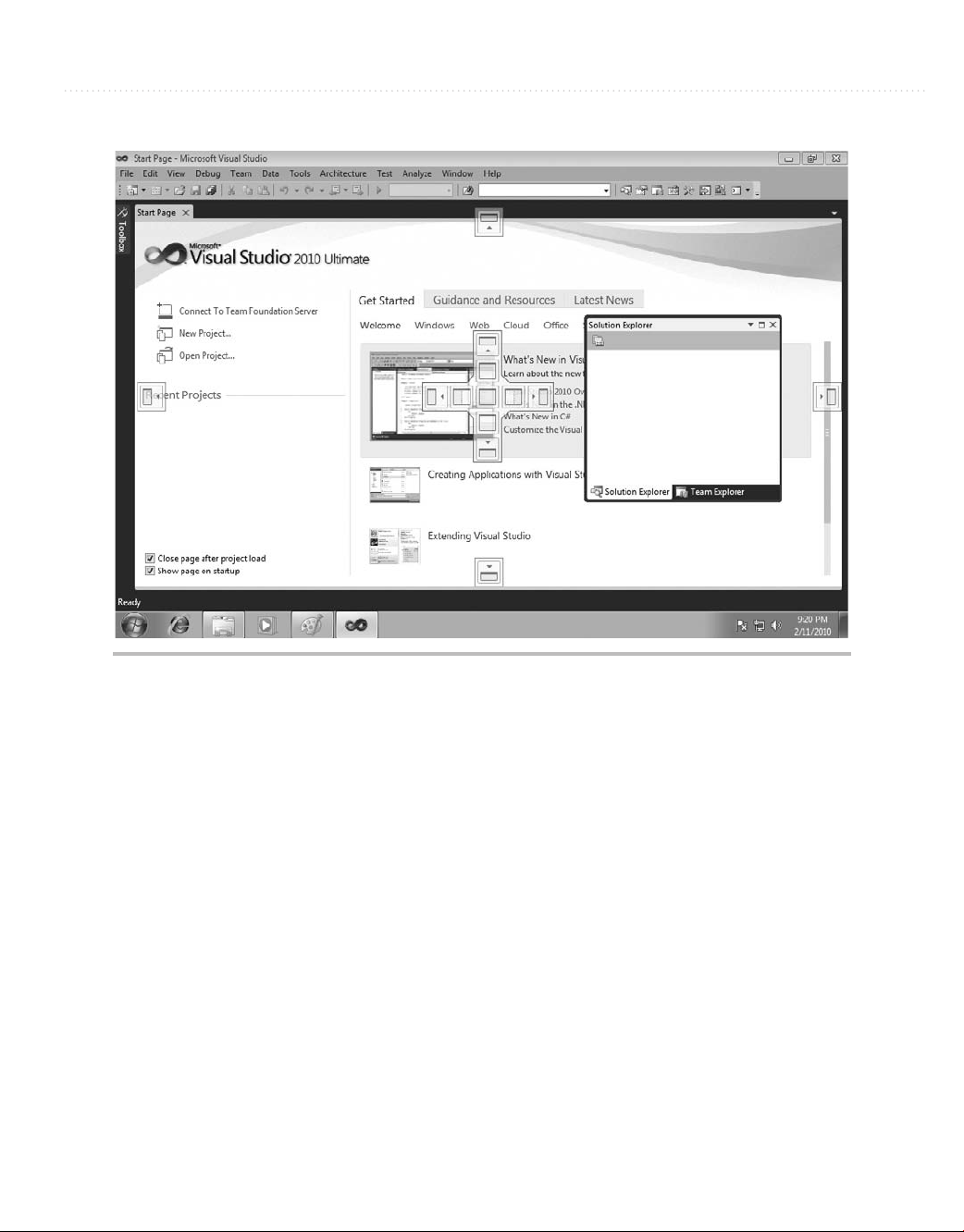

Figure 1-10 shows how VS appears when first started. It refers to portions of the screen,

helping you see how the IDE is organized. The following description will associate each

feature with a name so that you can understand where to look when discussing these features

in more depth throughout the rest of this book.

The following sections describe portions of the Start screen shown in Figure 1-10.

Page 37

14 Microsoft Visual Studio 2010: A Beginner’s Guide

Figure 1-10 Visual Studio 2010 Start screen

The Menu

At the very top left of Figure 1-10, you’ll see the menu bar, which includes the words

“File,” “Edit,” “View,” “Tools,” and so on. The menu bar is a standard part of most

windows applications. Besides standard file management functionality, the File menu is

where you visit to create new projects. The File menu also gives you access to recently

opened files and projects.

The Edit menu has your standard cut, copy, and paste operations. It also gives you

access to a bookmark feature for providing easy navigation through source code.

It would be worth your effort to explore the View menu to see what is available, but if

you are just learning Visual Studio and how to write software, it’s best to not click these

different views just yet; we’ll explore most of those views and what they’re used for later.

The View menu gives you access to all of the tool windows in VS. The View menu also

has a menu item named Other Windows that includes more application windows that will

come in handy as you create new software.

Page 38

Chapter 1: Introducing Visual Studio 2010 15

The Tools menu contains a grab-bag of functionality; for instance, you can attach a

debugger to see your other programs run, line by line; connect to a database for data; set

add-ins, macros, and more. One very important menu item on the Tools menu is Options,

which exposes hundreds of settings for customizing your VS environment.

You can use the Test menu to find all of the functionality for performing unit tests to

test your new software one part at a time. This is also where other editions of VS include

access to other types of testing tools.

The Analyze, Architecture, and Team menus have advanced functionality for improving

the performance of an application, working with application architecture, and integrating

with Microsoft’s Team Foundation Server.

The Windows and Help menus are similar to most other application types, where the

Windows menu allows you to manipulate the VS windows and the Help menu is where

you visit to find the technical documentation on VS.

TIP

Many menu items contain shortcut keys that perform the same action as selecting the

menu item. If you are curious about what shortcut keys are associated with a particular

action, you can often find them by opening the menu to see if there are shortcuts

associated with that action. For example, to open the Solution Explorer window and

visit the View menu, the shortcut keys are

CTRL-W, S.

Toolbar

Beneath the menu in Figure 1-10, you’ll find a toolbar. The toolbar contains frequently

accessed functionality that is a subset of what is available via menus. The toolbars are

context-sensitive, showing and hiding depending on what you are doing in VS.

display any toolbar by selecting View | Toolbars.

You can also customize toolbars by right-clicking the toolbar of your choice, scrolling

to the bottom of the list, and selecting Customize. The toolbar customization window

allows you to add any feature you would like to the current toolbar.

You can

Work Area

In the center of Figure 1-10, you can see the Start page. This is the same area that you’ll

use to write code and work with visual designers. The Start page is divided into two

sections: project management and information. The project management side of the page,

on the left, offers a quick way to start new projects or work with a list of recently opened

projects. The information side of the page, on the right, contains resources to help you get

started with VS, such as links to the Microsoft Web site, walkthroughs to help you learn

new features, and a tab that updates with the latest developer news from Microsoft.

Page 39

16 Microsoft Visual Studio 2010: A Beginner’s Guide

Toolbox

On the far left side of Figure 1-10 is a vertical tab, titled Toolbox, which contains a contextsensitive list of controls that can be dragged and dropped onto the current designer surface.

The term “context-sensitive” means that certain items are visible or hidden, depending on

where you’ve clicked last or what context you are working in, such as creating or editing

a new Web page. If you’re following along, you don’t have a designer surface open right

now, so the Toolbox is empty.

Solution Explorer

The Solution Explorer window, to the right of the Start page in Figure 1-10, is where your

solutions, projects, and project items will appear. This is where you can find and organize

all of the files and settings that belong to a project. In Figure 1-10, the Solution Explorer

is blank because there isn’t an open solution. If you close this window and need to find it

again, just remember the View menu discussed earlier.

Status Bar

At the very bottom of Figure 1-10 is the Status bar, which communicates what is happening

with VS at the current time. In Figure 1-10, the Status bar displays the word “Ready” to

indicate you can begin using VS at any time. As you work with VS, the Status bar changes

in a context-sensitive way to give you information specific to the task you are working on.

For example, the editor displays line, column, and other information pertaining to the status

of the editor.

Managing VS Windows

Looking at the VS screen in Figure 1-10, you can see how the windows in the work area—

Toolbox, Start, and Solution Explorer—are decorated with various title bars. Window

title bars include a set of three icons: Window Position (down arrow), Maximize/Restore

Down (window), and Close (cross). Figure 1-11 shows the Solution Explorer with these

three icons on its title bar at the top-right corner.

The Window Position allows you to treat the window as Dock, Float, Dock As Tabbed

Document, Auto Hide, and Hide. You can expand a window to fill the entire work area or

allow the window to be resized and float freely around the work area with the Maximize/

Restore Down icon. In the docked position, the Maximize/Restore Down icon becomes

a pin that can be used to pin the window open or allow it to slide shut. The Close icon

allows you to close a window. The following sections describe how use these title icons to

manipulate these windows through expanding and collapsing, docking, floating, tabbing,

and closing and opening.

Page 40

Chapter 1: Introducing Visual Studio 2010 17

Figure 1-11 Window title bar icons

Expanding and Collapsing Windows

Hovering over the Toolbox tab will expand the Toolbox and display a set of three icons in

the title bar of the Toolbox window: Window Position (down arrow), Hide (pin), and Close

(cross). You can see what the Toolbox window looks like when expanded in Figure 1-12;

the pin in the Hide icon is sideways and the vertical tab still appears in the left margin.

Figure 1-12 Expanded Toolbox

Page 41

18 Microsoft Visual Studio 2010: A Beginner’s Guide

If you move the carat away from the Toolbox, the Toolbox will collapse and turn back

into a tab on the left side of the screen.

For any collapsed window, such as the Toolbox, you can expand that collapsed

window and click the Hide (pin) icon to pin the window, which will make the window

layout similar to the Solution Explorer. Figure 1-13 shows the pinned window; the pin in

the Hide icon (above the Auto Hide tooltip) is vertical and you no longer see the Toolbox

tab in the left margin.

Clicking the Hide icon on any expanded window will cause the window to collapse

and display as a tab, similar to the Toolbox. Another way to collapse a window is by

selecting the Auto Hide option on the Window Position (down arrow) menu.

Docking Windows

The Dock option displays the window in an open docked position, similar to the Solution

Explorer in Figure 1-10. You can move a docked window to any position in the work

area. To move a docked window, select its title bar and drag the window out of its current

position. Figure 1-14 shows VS when you’re dragging a window.

Figure 1-13 Pinned Toolbox

Page 42

Chapter 1: Introducing Visual Studio 2010 19

Figure 1-14 Dragging a window for docking

As shown in Figure 1-14, you’ll see a visual set of icons appear over the workspace,

indicating the docking zones where you can move the window to. The shadow of the

window will show what the new location will be whenever you drag a window into a

docking zone. Dropping the window into the docking zone will move the window from its

old docking zone into the new docking zone.

Floating Windows

The Float option allows windows to appear anywhere in the VS IDE, where you can move

them at will. You move a floating window by selecting the floating window’s title bar and

moving the carat to the new location where you want the window to be. Alternatively,

you can double-click on the title bar. Figure 1-15 shows the Toolbox floating over other

windows.

Page 43

20 Microsoft Visual Studio 2010: A Beginner’s Guide

Figure 1-15 Floating a window

Tabbed Windows

An example of using the Dock As Tabbed Document option is the Start page. Any window

set as Dock As Tabbed Document will appear as a new tab in the work area, along with all

the other windows set as Dock As Tabbed Document. For example, if the Toolbox is set

as Dock As Tabbed Document, it will become a tabbed document in the same group as the

Start window, as shown in Figure 1-16.

TIP

Position windows in a way that makes you most productive. In practice, you probably

don’t want your Toolbox to be a tabbed window. You’ll see examples in later chapters

of this book that drag-and-drop items from the Toolbox to a designer page, which is

also laid out as a tabbed document window. So, trying to drag-and-drop between two

tabbed document windows can be cumbersome. There are several options for working

with Windows in VS, and after working with VS for a while, you’ll want to pick the

layout that works best for you.

To change a window from a tabbed document, select the tab and drag the window

away from the other documents, making it a floating window.

Page 44

Chapter 1: Introducing Visual Studio 2010 21

Figure 1-16 Tabbed document windows

Closing and Opening Windows

Clicking the Close icon on a window title bar will close the window. Another way to close

the window is by selecting the Hide option from the Window Position icon menu.

Reopening a window depends on what type of window it is: VS or Project Item. If the

window is from VS, you can re-visit the View menu and select the window you need to

open. Alternatively, you can use a keyboard shortcut key to open a window. These shortcut

keys for the windows are displayed on the right side of the menu item in the V

Other windows are for project items in the Solution Explorer. In most cases, you

would re-open a project item by locating it in the appropriate project of Solution Explorer

and double-clicking it. There are edge cases where you open project items by rightclicking the project item in Solution Explorer and selecting a menu item, but I’ll explain

those cases when I discuss them specifically in the rest of this book.

You can now manipulate windows, customizing the layout of your VS environment as

you need. Sometimes, though, you’ll want to reset your layout to the original default, as

you’ll learn about in the next section.

iew menu.

Page 45

22 Microsoft Visual Studio 2010: A Beginner’s Guide

Modifying Environment Settings after Setup

Reasons for modifying environment settings include wanting to reset everything back to a

default, importing shared settings from another developer, or switching between settings

for different projects. This section will explain how to modify your settings and achieve

each of these goals.

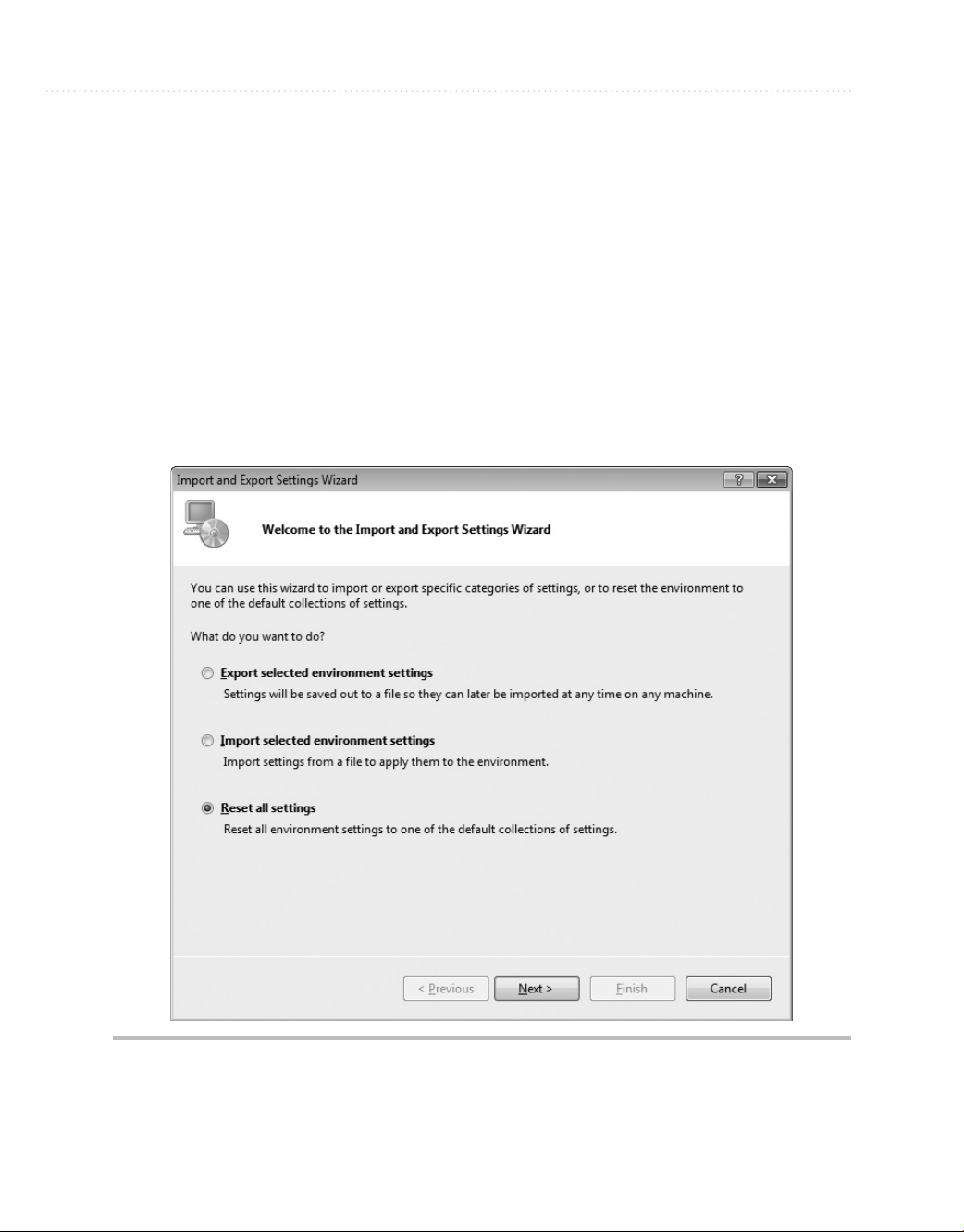

With VS open, select Tools | Import And Export Settings, which will start the Import

and Export Settings Wizard shown in Figure 1-17.

From Figure 1-17, you can see the options to Export, Import, and Reset settings. The

following sections explain each of these options.

Figure 1-17 Import and Export Settings Wizard

Page 46

Chapter 1: Introducing Visual Studio 2010 23

Exporting Selected Environment Settings

We’ll start off with export, which you might use to share your settings with another

developer. This could also be useful if you planned to make significant changes to your

settings and wanted a backup in case you wanted to revert to previous settings. T

the export, choose the “Export selected environment settings” option from Figure 1-17

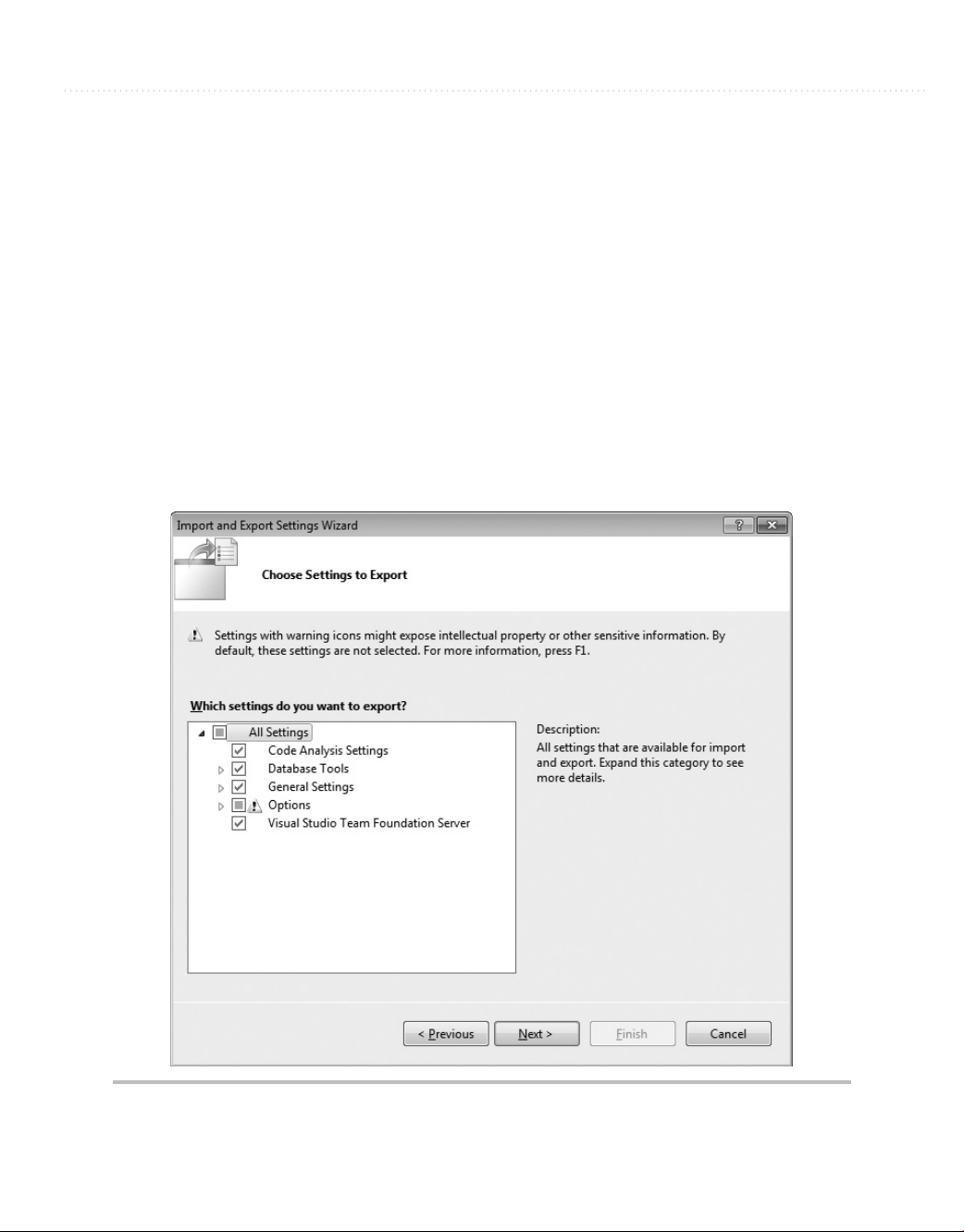

and click Next to display the Choose Settings To Export window in Figure 1-18.

There is a tree of options you can choose from to determine what settings to export.

The warning sign indicates settings that you might not want to export for personal or

security reasons. The warning settings typically have something to do with system file

paths or something outside of VS that you wouldn’t normally share with other people.

After you’ve selected options, click Next to display the Name Your Settings File window

in Figure 1-19.

o perform

Figure 1-18 Choose Settings To Export window

Page 47

24 Microsoft Visual Studio 2010: A Beginner’s Guide

Figure 1-19 Name Your Settings File window

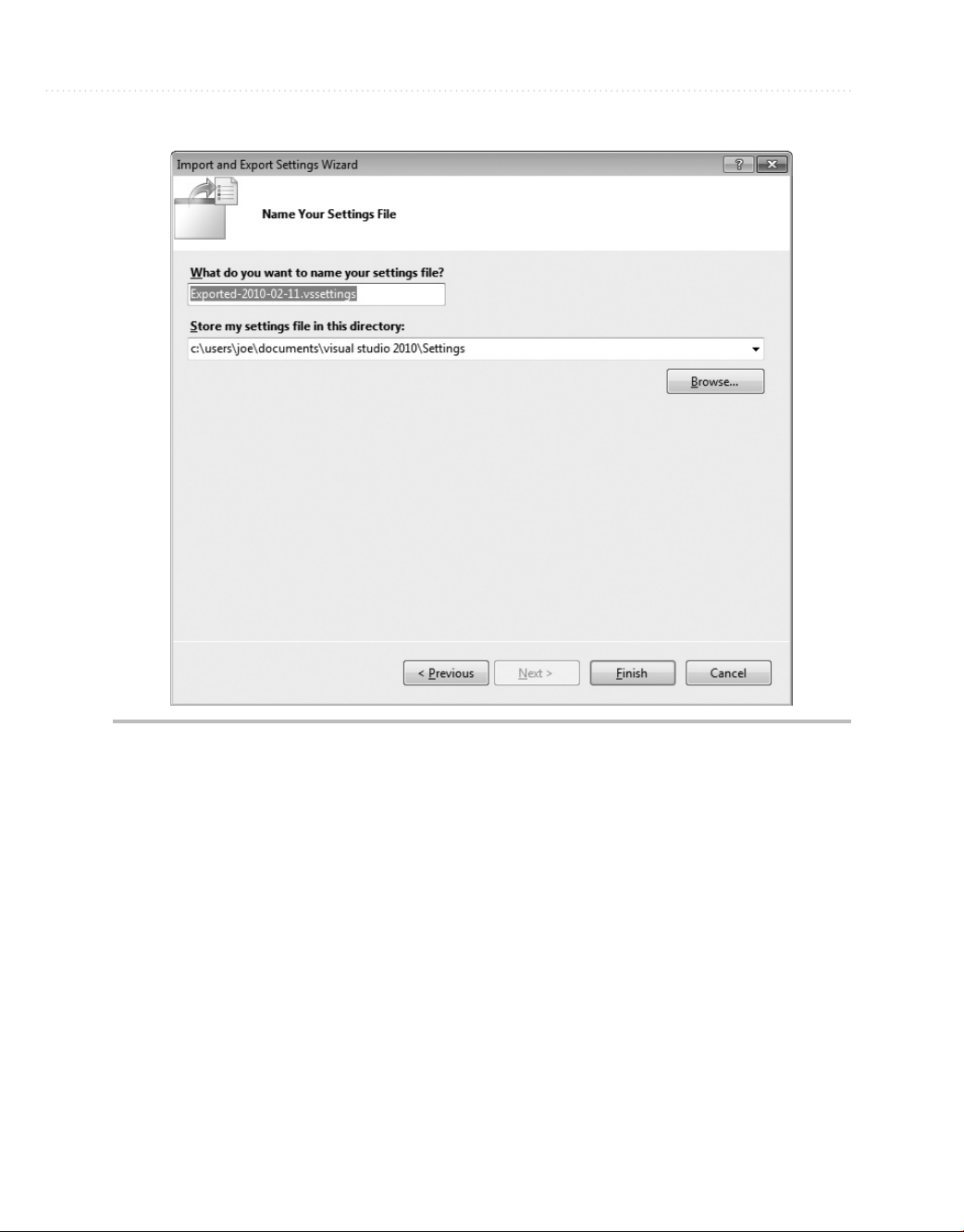

The two text boxes in Figure 1-19 are for a filename and path where the settings file

will be saved. Notice that the default filename includes the date, which could be helpful

if you ever need to restore settings. Click Finish, which will perform the export and show

you the Complete window in Figure 1-20 after the export operation is done.

Click Close to close the window. With an exported settings file, you or another person

can perform an import with that file, as described in the next section.

Importing Selected Environment Settings

You would perform a settings import to restore previous settings, import settings from another

person, or change to specific settings for a project you’re working on. To perform an import,

Page 48

Chapter 1: Introducing Visual Studio 2010 25

Figure 1-20 Export Complete window

open VS and select Tools | Import and Export Settings, which opens the Import and Export

Settings Wizard shown in Figure 1-17. Choose the “Import selected environment settings”

option and click Next to view the Save Current Settings window shown in Figure 1-21.

TIP

You can search for various color schemes for Visual Studio on the Internet to

download. One site, at the time of this writing, is http://winterdom.com/2007/11/

vs2008colorschemes; it offers schemes made for Visual Studio 2008 but that also

import into Visual Studio 2010.

Page 49

26 Microsoft Visual Studio 2010: A Beginner’s Guide

Figure 1-21 Save Current Settings window

The Save Current Settings window allows you to back up your current environment

settings before changing them. If you do a backup, you will be able to restore later in case

something doesn’t work out the way you intended with the import. You can choose not to

back up also. Click Next to view the Choose A Collection Of Settings To Import window

in Figure 1-22.

As shown in Figure 1-22, you can import some of the predefined settings that are

part of VS under the Default Settings branch or import custom settings under the My

Settings branch. Custom settings include the current settings and any other settings that

you’ve saved to the default path, shown in Figures 1-19 and 1-21. Optionally, you can

Page 50

Chapter 1: Introducing Visual Studio 2010 27

Figure 1-22 Choose A Collection Of Settings To Import window

click Browse and navigate to the location where a settings file is located. After selecting

a settings file, click Next, which brings you to the Choose Settings To Import window

shown in Figure 1-23.

The Choose Settings To Import window allows you to specify only those settings that

you want in your environment. It will only update the settings checked in Figure 1-23.

All of your other current settings, those that are unchecked in Figure 1-23, will not be

changed. Click Finish to begin the import operation. When import is done, you’ll see the

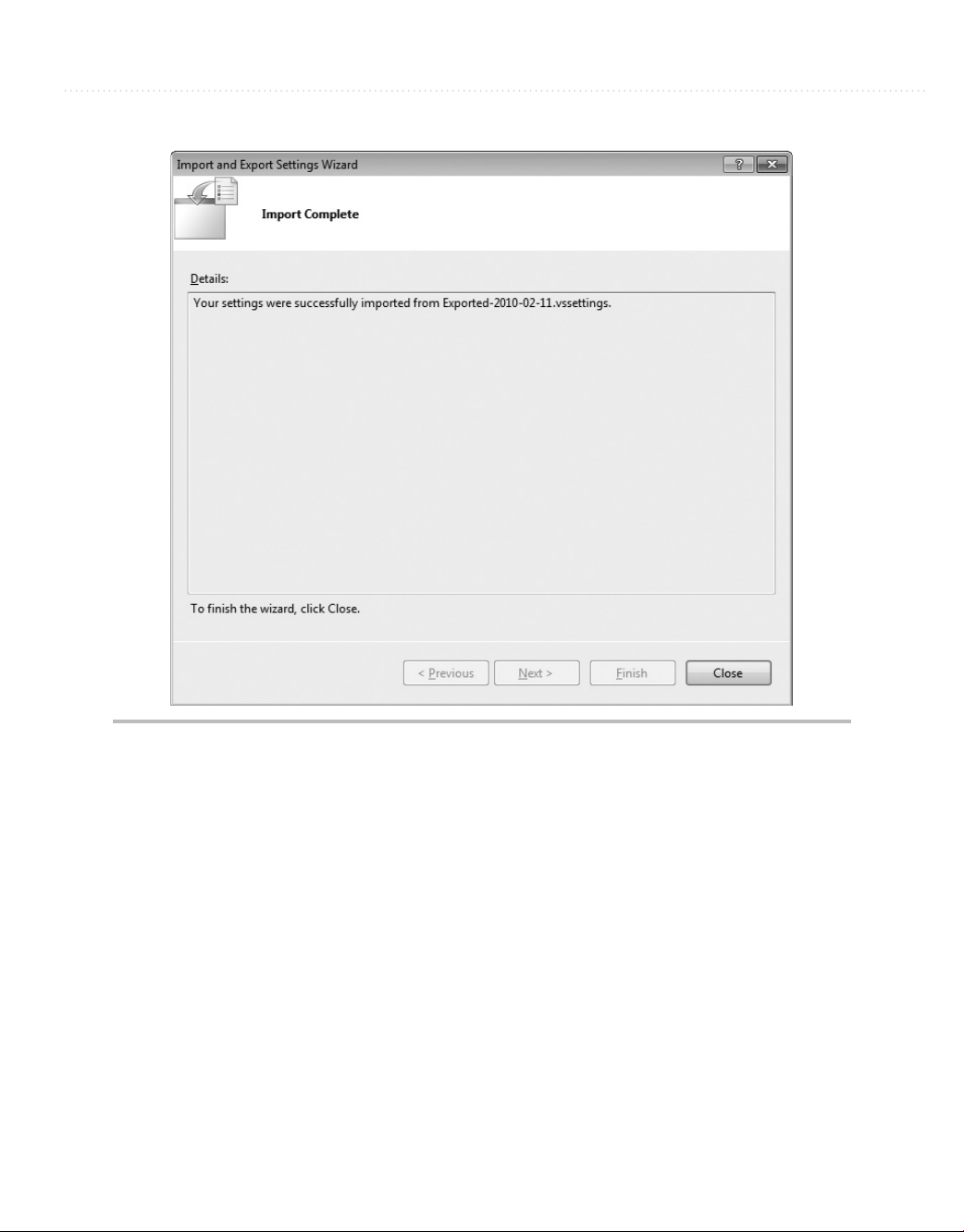

Import Complete window, shown in Figure 1-24.

Page 51

28 Microsoft Visual Studio 2010: A Beginner’s Guide

Figure 1-23 Choose Settings To Import window

Your import is now complete, and you can click the Close window. Another settings

option is to reset your current settings to one of the VS default options, explained next.

Resetting All Settings

You could reset settings if you wanted to restore the default settings in VS or if you