Page 1

Fontographer User's Manual

Contents

Introduction: What a Long,

Strange Trip It’s Been

Introducing Fontographer

How to get the most out of your

Fontographer materials

Tips icon

Before you begin

Getting started

Read me...

Registering your software to receive technical

support

Network Copy Protection

Chapter One: Modifying Your Fonts

Steps to modifying your font

Opening a font

Changing the character’s weight

Naming your font

Saving your work

Generating your font

Installing the font

Using the font

Creating an oblique font

Skewing multiple characters

Creating a fraction using composite

characters

Unlinking a reference character

Table of Contents Page #1

Page 2

Fontographer User's Manual

Creating a ligature

Changing the character width

Creating a condensed character or font

Setting the basepoint

Chapter Two: Creating New Fonts

Autotracing

Tracing an image

Advanced tracing options

Curve fit

Allow curve fit errors

Balance lines

Eliminate close points

Make straight lines

Look for cusps

Treat nearly flat paths as straight lines

Find extrema points

Transformation options

Flip

Move

Rotate

Scale

Scale uniformly

Skew

Multiple transformations

3-D transformations using the Transform dialog

Guidelines

Setting guidelines

Setting guidelines from the Font Info dialog

Adding new guidelines

Hiding guidelines

Snap to guides

Table of Contents Page #2

Page 3

Fontographer User's Manual

Creating a stroked font

Outline vs. stroked characters

Setting stroke attributes

End caps and joins

Expand stroke

Clean Up Paths

Creating calligraphic characters

Calligraphic tutelage from Judith Sutcliffe

Creating variable weight characters

Blend Fonts to create new fonts

When things go wrong...

Jonathan Hoefler sez...

Chapter Three: Altering Outlines

Altering a logo

Pasting EPS outlines from the clipboard

Paths and points

Closed paths

Path direction and fills

Normal fill

Even/odd fill

Correct path direction

Reverse path direction

Types of points

Curve points

Corner points

Tangent points

Selecting multiple points

Changing a point type

Inserting points

Duplicating points

Table of Contents Page #3

Page 4

Fontographer User's Manual

Power duplicating

Removing points

Splitting a path

Splitting line segments

Joining points

Adding Serifs

Merging points

Moving a point

Demagnified move

Keyboard commands to move points:

Accurate point placement

Point and path preferences

Path display

Point display

Show and hide control points

Editing and placing BCPs

BCP principles

Dragging a control point’s BCPs

Dragging a curve point’s BCPs

Dragging a corner point’s BCPs

Dragging a tangent point’s BCPs

Retracting BCPs

Auto Curvature

Chapter Four: Editing Bitmaps

Using the Bitmap Window

The Bitmap Window

Editing a bitmap

The central edit area

Ascent and descent values

Offset and width values

Visible layers

Tools in the Bitmap Window

Table of Contents Page #4

Page 5

Fontographer User's Manual

Undo and Redo

Changing bitmap views

Enlarging using the View Menu

Switching characters in the Bitmap Window

Next and previous character

Next and previous point size

When should you recalculate bitmaps?

Preserving your original bitmaps

Chapter Five: Metrics: Spacing

and Kerning

Spacing

Pair kerning

Auto Spacing

Auto Kerning

The Metrics Window

Character display

The spreadsheet area

Importing Metrics

Clearing kerning pairs

Exporting Metrics

The Fontographer Metrics file

Copying widths

More powerful spacing and kerning

commands

Set Width

Equalize Sidebearings

Advanced Metrics operations

Set Metrics

Assisted Metrics

Table of Contents Page #5

Page 6

Fontographer User's Manual

Metrics Assistance

Kerning Assistance

Advanced Auto Spacing

Advanced Auto Kerning

Chapter Six: Printing

Sample text

Sample file

PostScript file

Key map

Kerning pairs

Characters

The print header

Chapter Seven: Generating and

Exporting Fonts

Before you do anything...

Easy or Advanced?

Macintosh fonts

PostScript Type 1

The PostScript ID Field

TrueType

Include vertical and horizontal hints

Include diagonal hints

Dropout prevention

Character mapping

PostScript Type 3

Other Type 3 Formats

None

Encoding Options

When should you use Hints?

A word about Flex

A special note to designers of nonRoman Macintosh fonts!

Table of Contents Page #6

Page 7

Fontographer User's Manual

Windows fonts

PostScript Type 1

Other Options

Overwrite existing files

Output AFM file

Output PFM file

Output INF file

The CFG file

TrueType for Windows

Symbol Encoded PC fonts

PostScript Type 3

NeXT and Sun PostScript fonts

Pack your Suitcase: Bitmap fonts

Bitmaps vs. Outlines

Adding bitmap sizes

Deleting bitmap sizes

Bitmap format

None

NFNT

BDF

FON

The ID Field

The menu name

Creating bitmaps for cross-platform use

Exporting files

Exporting EPS files

Exporting Macintosh PICT

Exporting Encoding

Chapter Eight: Creating a Font

Family

Families: Windows, SUN, NeXTSTEP

Font families on the Macintosh

Table of Contents Page #7

Page 8

Fontographer User's Manual

How Style Merger works

Things you should know about Style Merger

Adobe Type Reunion (ATR) compatibility

Chapter Nine: Installing and

Removing Fonts

Installing Macintosh PostScript fonts

Installing PostScript fonts in System 6 or earlier

Installing PostScript fonts in System 7.0.x

Installing PostScript fonts in System 7.1 or

later versions

Installing PostScript fonts with Suitcase or

MasterJuggler

Macintosh TrueType font installation

Installing TrueType

Installing TrueType fonts in System 7.0.x

Installing TrueType fonts in System 7.1 or later

Installing Windows fonts

Installing PostScript fonts in Windows 3.x or

higher with Adobe Type Manager 2.x

Windows TrueType and .fon installation

Installing TrueType and .fon fonts in Windows 3.1 or later

versions

Installing TrueType Fonts in Windows 95

Transferring Windows fonts from the Macintosh

to your PC

Transferring fonts from the PC to your Macintosh

Porting NeXT PostScript fonts to

NEXTSTEP

From the Macintosh

Installing PostScript fonts in NEXTSTEP

Porting Sun PostScript fonts to the SUN

Installing PostScript fonts

Table of Contents Page #8

Page 9

Fontographer User's Manual

Installing Type 1 fonts in OS/2 Version

2.0

Removing installed fonts

Removing a Macintosh font

In System 6.0

In System 7.0

In System 7.1 or higher

Removing a Windows font

PostScript

TrueType

Removing fonts from the NEXTSTEP operating

system

Removing fonts from Solaris 2/Open Windows

3 on the SUN

Removing fonts from OS/2 2.0

Chapter Ten: Expert Advice

General preferences

Options for Undo

Using the keyboard to choose a character

When reading an outline font

Editing behavior

Distances

Behavior of Snap to Point

When a path is clicked on

Point display

Windows and dialogs

Window preferences

Dialog box

Defaults

Font blending—the technical details

The blending process

Table of Contents Page #9

Page 10

Fontographer User's Manual

Font hinting

Are you still with us?

What is hinting all about?

Hinting controls

Autohint

Editing hints in the Outline Window

Removing hints

Making new hints

Selection Info for hints

Hint type

Apply to

The buttons

Vertical Alignment Zones

Hint Parameters

Hints to include

Hint order

Hint direction

Common stems

Changing the default

What happens when Fontographer opens up

PostScript Type 1 fonts

What happens when Fontographer opens

TrueType fonts

Using a resource editor to tweak Fontographer

4.1 on your Macintosh

Adding custom encoding vectors

Creating the names resource

Setting Developer IDs

Customizing Sample Text printout

Customizing Fontographer sounds on your

Macintosh

Customizing Fontographer sounds on your PC

Chapter Eleven: Reference Section

Windows

Table of Contents Page #10

Page 11

Fontographer User's Manual

Font Window

View by menu

Outline Window

Tool palette

Layers palette

Changing and hiding layers

Magnification

Switching characters

Bitmap Window

Tool palette

Ascent/Descent/Offset/Width

From outline

Magnification

Scrolling

Switching characters

Changing point sizes

Metrics Window

The keys to using the Metrics Window are:

Kerning and sidebearing lines

Key commands to change spacing and/or

kerning:

Kerning

File

Menus

About Fontographer

The File Menu

New Font

Open Font

Close

Save

Save As

Revert

Table of Contents Page #11

Page 12

Fontographer User's Manual

Preferences

Generate Font Files

Import

Export

Print

Quit/Exit

The Edit Menu

Undo

Redo

Cut

Copy

Paste

Clear

Copy Widths

Copy Reference

Unlink Reference

Select All

Duplicate

Clone

The View Menu

Preview

Show points

Magnification

Next Character

Next Kerning Pair

Next Point

Next Point Size

Previous Character

Previous Kerning Pair

Previous Point

Previous Point Size

Snap to Points

Snap to guides

Table of Contents Page #12

Page 13

Fontographer User's Manual

Snap to Grid

The Element Menu

Transform

Flip

Move

Rotate

Scale

Scale uniformly

Skew

Arrange

Font Info

Selection Info

Bitmap Info

Auto Trace

Change Weight

Clean Up Paths

Expand Stroke

Recalc Bitmaps

Remove Overlap

Correct path direction

Clockwise

Counterclockwise

Blend Fonts

Multiple Master

(Macintosh only)

The Points Menu

Align Points

Align Points to Grid

Merge Points

Retract BCPs

Split Points

Auto Curvature

Curve Point

Table of Contents Page #13

Page 14

Fontographer User's Manual

Corner Point

Tangent Point

Set Basepoint

Reset Basepoint

The Metrics Menu

Auto Space

Auto Kern

Kerning Assistance

Metrics Assistance

Set Metrics

Set Width

Equalize Sidebearings

Clear Kerning Pairs

The Window(s) Menu

Open Outline Window

Open Bitmap Window

Open Metrics Window

View Windows by

Show Layers Palette

Show Tool Palette

The Window Choices

Make Vertical Stem

Make Horizontal Stem

Make Vertical Serif

Make Horizontal Serif

Make Diagonal Hint

Build Serif

Split Serif

Flip Hint Direction

Hint Parameters

Vertical Alignment Zones

Autohint

The Help Menu (PC Only)

Table of Contents Page #14

Page 15

Fontographer User's Manual

Contents

Keys

How to Use Help

About Fontographer

Special keys

Keyboard alternatives

Appendix A: Tips

Appendix B: Answers to

commonly asked questions

Appendix C: General information

Type terminology

Fontographer background

Bitmap background

PostScript background

Filling techniques

LaserWriter background

Appendix D: A Short Bibliography

of Typography and Allied Subjects

Overviews of Printing Types

Type Designs from Various Periods

Typography

Type Designers

Typeface Reference Works

History of Printing

Electronic Typography

Bibliographies

Book Dealers/Publishers Specializing in

Typography

The Fontographer User Guide Bibliography

Table of Contents Page #15

Page 16

Glossary

Fontographer User's Manual

Table of Contents Page #16

Page 17

Fontographer User's Manual

Introduction

What a Long, Strange Trip It’s

Been

Introducing Fontographer

How to get the most out of your Fontographer materials

Before you begin

by David Berlow

They say that good things come in small packages. When it

comes to Fontographer, this has never been so true. In

1985, I was working at Bitstream designing type on a large

proprietary font design system. For those of you who don’t

know what this means, I’ll tell you. Large means it wouldn’t

fit on a desktop because it was larger than a desk. We had

workstations that were about six feet wide by six feet deep

by four feet tall, with a 19" vector-monitor, a mouse with

four or five buttons, and a keyboard with a few dozen extra

keys. If you must know, this was trucktop publishing.

Proprietary means that we developed the software and

some of the hardware ourselves so no one else could use it,

and there were only two or three engineers in the world

who knew how to make changes, additions or fixes to the

software and this happened quite infrequently and very

slowly. In addition, proofing the fonts required a series of

conversions, and mastery of a typesetting command

language about as friendly as Kanji.

Into this world, one day, came two visitors from somewhere

down south. They carried a little box that, because it was so

small, I thought was surely a kitchen appliance, a toaster or

blender perhaps. But when they plugged it in there seemed

to be type drawing going on inside of the little box. There

were about ten Bitstream type designers in the room and

we all gasped. I climbed upon the table to get a closer look

and sure enough, there was a letter on that tiny screen. But

Introduction Page #1

Page 18

Fontographer User's Manual

there were not enough points on the character and not

enough buttons on the mouse and the screen was smaller

than my face—how could this possibly work? Well, within

two months I had a Mac Plus and Microsoft Word, so I

could “correspond with our clients.” I also purchased my

first copy of Fontographer from Altsys. I played around and

drew a few characters. It took a while to get the hang of

the Bezier tools. At first I thought I had a tiger by the tail.

But for me, used to the real estate of the big screen, and

the point structures of Bitstream outline fonts, this “toaster”

font design system was like painting a picture through a

porthole.

A bit later though, the Mac II came out. It didn’t take me

long to convince the powers at Bitstream

that “corresponding with our clients” would be a lot easier if

I had a more powerful machine and a bigger screen and a

LaserWriter and a 300 dpi scanner. (I can’t remember how

I got the scanner, I think it had something to do with OCR.)

The first upgrade of Fontographer also was bought and now

I was able to cook. I started making characters that were

much more complex than what we could make on our

proprietary system and I was making them in much less

time. But still I wasn’t making fonts. I will never forget the

first time I actually made a font on Fontographer.

Roger Black, the well-known publication designer who

worked at Newsweek back then, wanted a font for his

redesign of California Magazine. Roger had visited the

letterdrawing offices at Linotype where I worked in the

70’s, and he had visited Bitstream as well in the 80’s in

several failed attempts to get Linotype and Bitstream to

make custom fonts for him and his clients. When he came

back to strafe us again in the winter of 1986, we were

ready. Matthew Carter, Bitstream’s VP of design,

deflected him at me and I told Roger that we had never

actually made a font with Fontographer and the Mac, but

we would love to try. He sent me the artwork of a long

neglected type from an Italian foundry which I scanned,

and went to work on digitizing and spacing. I was totally

stunned at how quickly it was done and the quality of the

results. It was great, and Roger loved it as well. Most

especially because it took less than a working week to

accomplish. From the time we agreed to do the face to the

time it appeared in the magazine was about a month!

Introduction Page #2

Page 19

Fontographer User's Manual

By 1989, Fontographer was getting better and better. Things

like remove overlap, correct path direction, merge point, the

ability to generate Type 1 fonts and more, were all making

it a pleasure to design fonts for the first time in my life.

The Mac was getting more powerful and there were a lot

of graphic designers, droves in fact, moving to the Mac. But

they were constrained in their graphic design by the limited

availability of fonts on the Mac. When Fontographer got

hinted generation of Type 1 fonts into the market in 1990,

the font world was truly changed. By this time I had left

Bitstream to concentrate fully on The Font Bureau, the type

design company I have founded with Roger Black. We

released our first retail fonts that year. The general

impression was that they were as good as any fonts

available for the Mac. Needless to say, Altsys had become

my best friend. Throughout these years, from 1985 to 1990,

the most astonishing thing to me was that Altsys was

constantly improving the features, performance and ease-ofuse of Fontographer in spite of the fact that there was no

competition in the field for Fontographer. When competition

and a larger user base developed, Altsys went into

overdrive. Through Fontographer 3.0 and 3.5, TrueType

and PC font generation, improved printing functionality,

Multiple Masters, change weight, and all the rest—Altsys

was always doing the right things at the right time for all the

right reasons. Today, you have before you the next

generation of this great tool. Macromedia Fontographer 4.1

is a truly revolutionary change in the quality and

functionality of type design tools. Letter spacing is treated

like a database, scaling, rotation, skewing and such are

totally interactive functions, and autotrace is amazing! The

Font Bureau tested and tempted itself with version 4 as

soon as the specification came to us in 1991. Throughout

our review and use of version 4, we had the feeling that we

had only scratched the surface of what it can do for type

designers like us. In the coming year we think we’ll be

finding out that we’ve got a tiger by the tail—again!

Good luck to all, and thanks to the Fontographer team!

Introducing Fontographer

Welcome to Fontographer!

Introduction Page #3

Page 20

Fontographer User's Manual

First of all, thank you for buying our product. Second, thanks

for opening this manual. We hope you’re reading it not

because you’re having trouble, but because you want to

learn more about this exciting program.

Our manuals are written by people who actually use (and

create) Fontographer and who have graphic arts and

typography backgrounds. We’ve tried to be as informative

as possible without being stuffy.

We hope you’ll find every aspect of this program easy:

from our unique approach to learning, to the panoramic

interface of the program itself, and finally, to the actual

process of creating fonts. We want your experience with

Fontographer to be so satisfying and painless that when

you’re through, you’ll agree that this is the best font design

program in the world!

As a matter of fact, Fontographer has been the standard for

professional typeface and logo design since its introduction

in 1986. Before Fontographer, typed images could only be

produced by using complex, expensive, and time-consuming

procedures. With the advent of personal computers

however, typography became attainable to everyone: from

the graphic illustrator to the desktop publisher to the

business executive. And now, Fontographer provides this

capability to you.

So, on with the manual—we hope you enjoy it.

Fontographer 4.1 allows you to generate ATM-compatible

Type 1 fonts, as well as Type 3 PostScript fonts, TrueType

fonts, PICTs and multiple masters on the Macintosh, and

Encapsulated PostScript (EPS) files. You can import EPS

files directly, and use their outlines in the drawing window.

You can also use metrics information from a variety of

sources, and export information to those sources, as well.

Additionally, you can import kerning tables from Adobe

Font Metrics (AFM) and other files. You can also take

advantage of the PostScript graphics you create in

Macromedia FreeHand and Adobe Illustrator by pasting

them directly into your characters.

Many dialogs in the program give you two options: Easy

and Advanced mode—letting you have total control of the

program if you want it, or allowing you to rely on its simple

Introduction Page #4

Page 21

Fontographer User's Manual

and automatic settings.

For advance users who don’t always want to rely on

automatic hint settings, we have a menu of hinting controls.

And in the Metrics arena, Fontographer lets you space and

kern faster and easier than ever. With autospace, autokern,

and assisted kerning and metrics you can save yourself

from having to kern and space each individual character or

font separately. Now you can ask Fontographer to do it

automatically, or you can use the same kerning and spacing

information from one font, for others that kern and space

similarly.

So whether you are a novice or an experienced graphic

designer, Fontographer allows you to assign your characters

and graphic images to any key or combination of keys, and

gives you the added ability to instantly repeat and resize

these images in any application.

Fontographer makes it easy to create new typefaces or add

your logo to existing typefaces. Fontographer’s drawing

tools help you create a professional-quality character in

minutes and print that character on any Post-Script or

TrueType compatible printer. Now, with Fontographer and

your personal computer, you can create designs that rival

those produced by professional typographers.

How to get the most out of your Fontographer

materials

Our User’s Manual is designed for both Macintosh and

PC users. We placed keyboard alternatives after certain

menu commands; the Macintosh command is always

followed by the command for the PC. Get into the habit of

using these “quick commands” that our more experienced

users prefer.

For basic information about using Fontographer on the

Macintosh, and for information about how to set up

Macintosh multiple master fonts and KHCRs refer to

Using Fontographer on Your Macintosh. For the PC,

refer to Using Fontographer on Your PC.

For an update on the changes made to the newest version

of Fontographer, see the What’s New guide for current

users. What’s New is in two parts: Part I: Best New

Introduction Page #5

Page 22

For the PC version of Fontographer 4.1, you will need a 386

Fontographer User's Manual

Features and Abilities, and Part II: Tips for Previous

Fontographer Users.

All of the Fontographer manuals assume that you are

familiar with the computer and that you have a working

knowledge of how your system operates. If you need

more information on these topics, refer to your

Macintosh or PC owner’s manual.

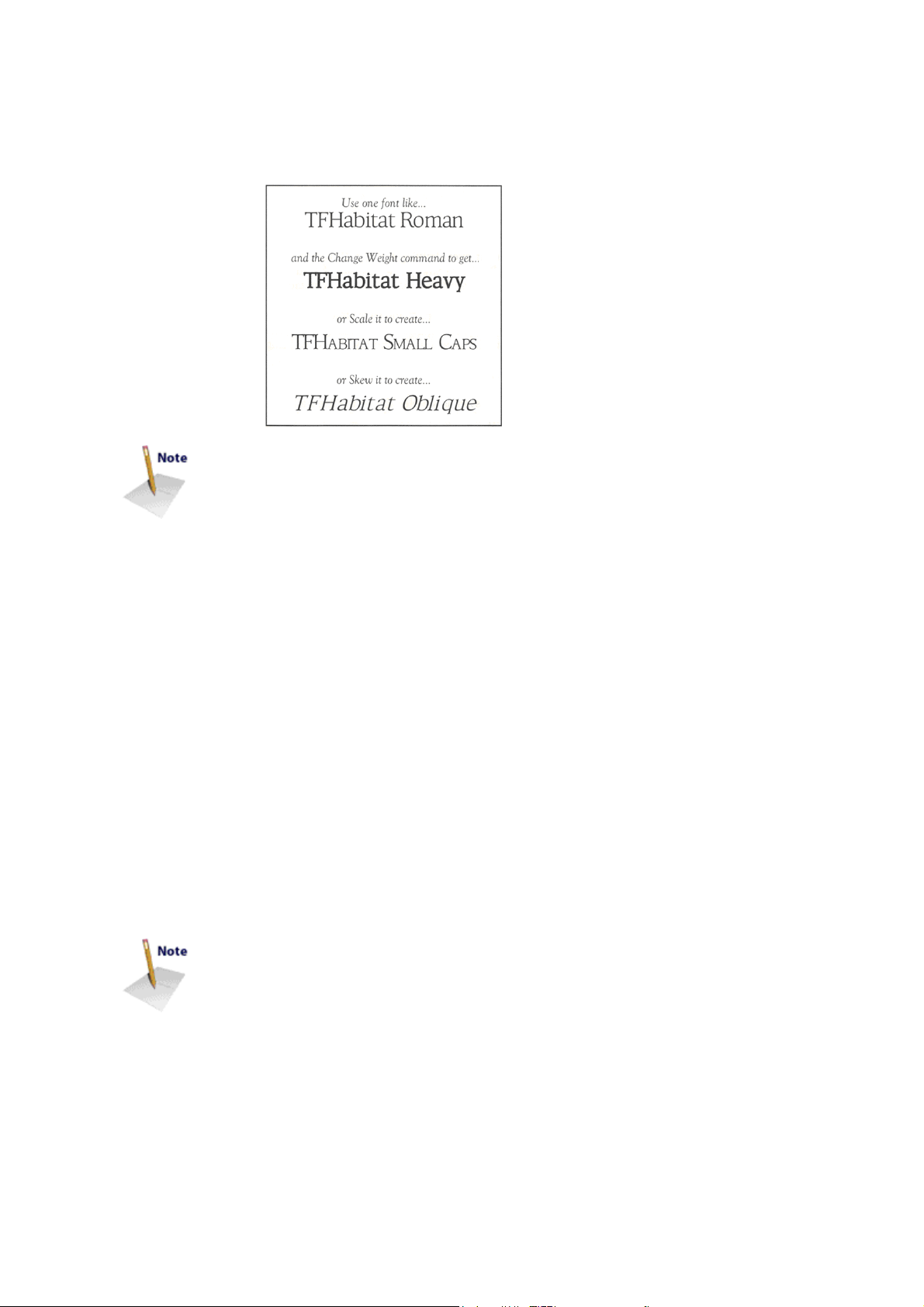

Tips icon

We’ve also compiled a truly excellent collection of tips you

can use to create your fonts. Tips are also easy to find.

Look for this tip icon throughout the manual or find them

under “Tips” in the Index.

Before you begin

Getting started

Before you can actually start using Fontographer, you need

to check to make sure your package is complete. Your

package should include a “User’s Manual” (this

book), “What’s New,” “Using Fontographer on Your

Macintosh” OR “Using Fontographer on Your PC,” a

Quick Reference Card, a product registration card, and—of

course—a CD ROM. In the event you don’t have access

to a CD ROM reader, you will also find a floppy disk

request card with which you can request software on 3.5

diskettes.

Make sure that you have everything you need to be able to

use Fontographer. If you are using the Macintosh version

of Fontographer 4.1, you must have a Macintosh Plus (or

higher) computer running a System 6 or later operating

system with 5.1 MB hard drive space, and at least 4 MB of

available RAM. It’s also a good idea to make sure you have

the latest version of Apple’s Hardware System update for

your machine. Otherwise you may encounter unexpected

results. You can get this utility from your Apple dealer,

through local user’s groups, or from Apple’s on-line

service AppleLink™.

Introduction Page #6

Page 23

Fontographer User's Manual

For the PC version of Fontographer 4.1, you will need a 386

(or better) computer running Windows 3.1, 3.11, NT, or

Windows 95 with 5.5 MB hard drive space, VGA video,

and at least 6 MB of available RAM. If you want to print

PostScript files from your PC, you will also need have an

HP driver dated after September 1993, or use Adobe 3.01

PostScript driver.

Read me...

All Macromedia release and update disks contain a

document titled ReadMe (.txt). It contains late-breaking

information about the product which may not be present in

the User’s Manual. You should read this file before

attempting to use the program.

Registering your software to receive technical

support

To become a registered user and receive technical support,

you must complete and return the registration card included

in this package.

Macromedia believes in customer support, and wants to

resolve any problems you have.

Our support lines are available Monday through Friday from

6:00 a.m., to 5:00 p.m. Pacific Time. The technical support

phone number for Fontographer is (415) 252-9080. Please

have your serial number on-hand when you call. You can

also try the MacroFacts faxback at (800) 449-3329, or

check out Macromedia’s web site at http://www.

macromedia.com.

Network Copy Protection

No, Fontographer is not “copy protected.” We know that

most people view copy protection with the contempt usually

reserved for root canals and tax audits. The last thing we

want to do is make it difficult to use Fontographer. We

have, however, given Fontographer the ability to detect

copies of itself running elsewhere on a network. Should you

receive the following message, “Sorry, the user

Introduction Page #7

Page 24

Fontographer User's Manual

named ‘blah blah’ is using a duplicate of this program...,”

this means that more than one copy has inadvertently been

personalized with the same serial number.

In order to alleviate this problem, simply discard the

Fontographer preferences file (located in the Preferences

folder in your System folder on the Macintosh, or in the

FOG41 directory on the PC), restart Fontographer, and fill

out the Fontographer personalization dialog with a different

serial number. If you have only one serial number (meaning

you only purchased one copy of Fontographer), you must

purchase additional copies of Fontographer in order to run

more than one copy at the same time. (For additional

copies, call Macromedia at (415) 252-2000, or your nearest

Fontographer dealer).

Introduction Page #8

Page 25

Fontographer User's Manual

Chapter One

Modifying Your Fonts

Steps to Modifying Fonts

Opening Fonts

Changing Character Weight

About Font Piracy

Creating Oblique Fonts

Creating Fractions

Creating Ligatures

Creating Condensed Characters

Imagine an ideal world where you can create completely

new fonts without ever drawing a thing. Picture yourself in

this “Font Utopia,” creating new weights of your font, new

small caps versions, and new oblique typefaces—without

drawing a line, placing a point, or manipulating a curve.

Does the very concept sound so far-fetched as to be

beyond belief? Well, it’s not...because Fontographer lets

you create completely new fonts by modifying your existing

fonts.

Why would you want to modify a font instead of buying a

new one? The answer is simple: You’ve invested a lot of

money in the typefaces you own. Although many talented

people create their own from scratch, the easiest way to

create a completely new typeface is by modifying the fonts

you already have. Fontographer makes it so easy to modify

your existing typefaces, that you practically don’t even have

to think about it. So, if you don’t have to think about it...

what’s the point of this section? This section gives you

some quick ways to make modifications. Hopefully, it will

encourage you to create some outstanding typefaces of

your own.

1: Modifying Your Fonts Page #1

Page 26

Fontographer User's Manual

Steps to modifying your font

1. Open a font.

2. Modify it; for example, you can simply change the

weight.

3. Save the file (Optional).

4. Generate an installable font.

5. Install the font.

6. Put it to work!

Opening a font

You start Macromedia Fontographer the same way you

start other applications—by double-clicking the program

icon. In a few seconds, Fontographer’s About box appears.

Choose “Open Font” from the File menu to open one of the

fonts in your System, a folder, a file server, or a disk (or

you can use one of the fonts provided in the Sample Fonts

folder).

The standard file selection dialog works in the normal

fashion, so you can change drives or directories, open a file,

or cancel. You can also specify which types of font file

formats you want to display. On the Macintosh you can

eject disks as well.

Once the selection dialog is open, you can select a font file

by clicking on its name and then “Open,” or simply by

double-clicking on its name.

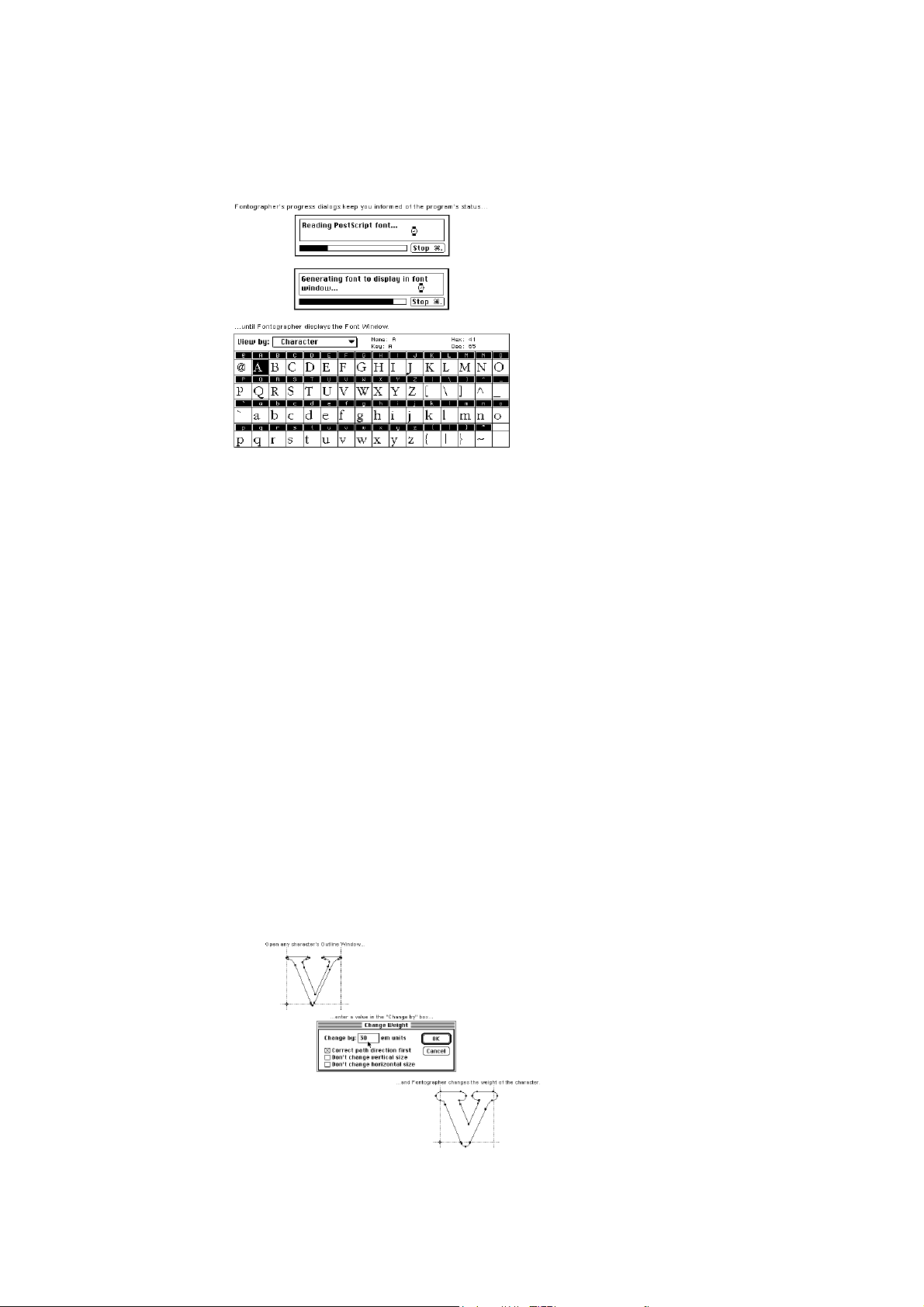

One or more progress dialogs will appear before

1: Modifying Your Fonts Page #2

Page 27

Fontographer User's Manual

Fontographer displays the Font Window. To cancel

progress dialogs, type Command-period on the Macintosh,

or Esc on the PC.

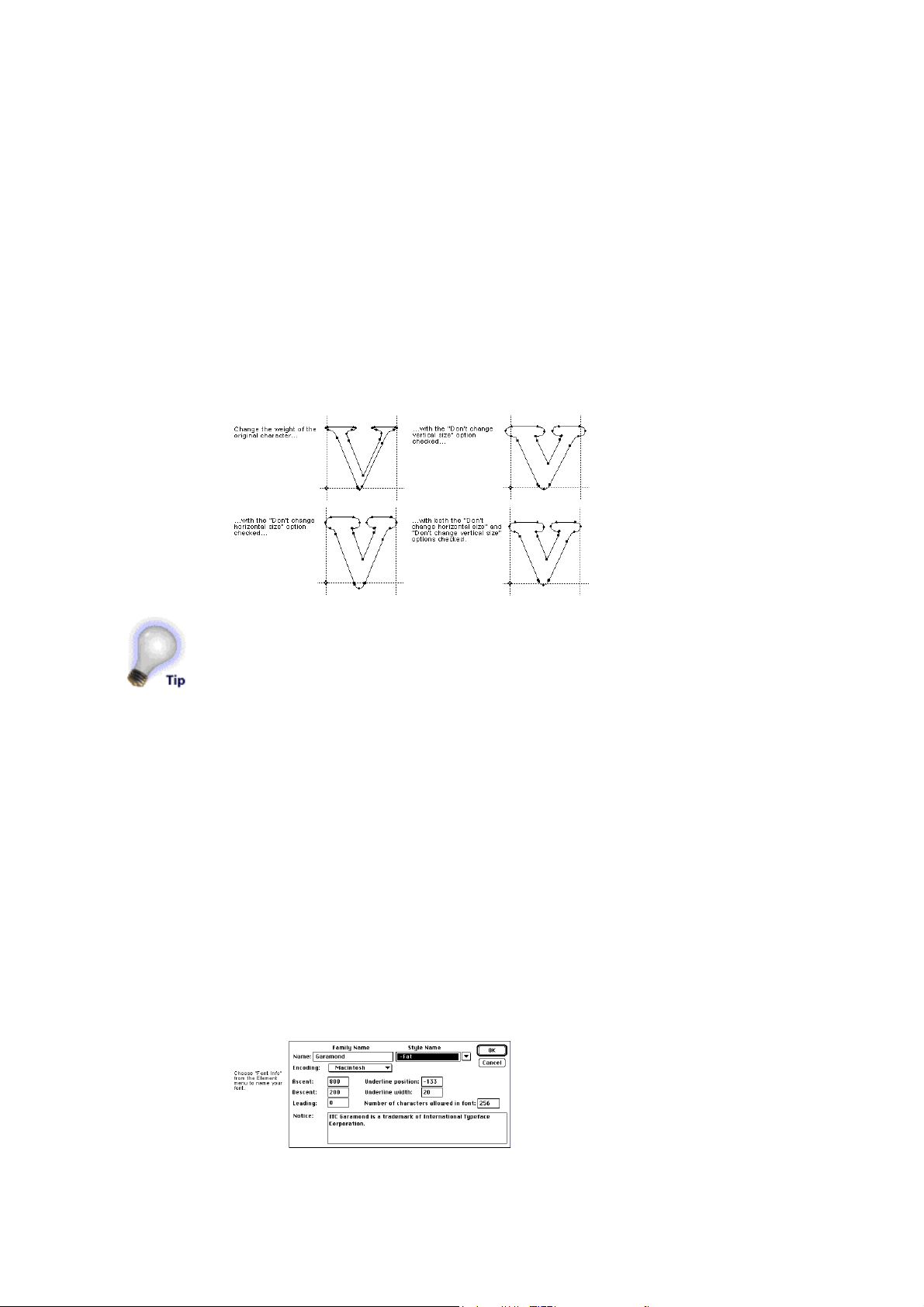

Changing the character’s weight

You can quickly create a heavier or lighter version of your

character (or the entire font) by using Fontographer’s

Change Weight command.

To change weight:

1. Go to the Font Window and double-click on the “v”

to open it.

2. Choose “Change Weight” from the Element menu.

The “Change Weight” dialog appears.

3. Enter “30” in the “Change by” text edit box and

click “OK.”

Fontographer increases the weight of the “v” by 30 em

units.

Fontographer also gives you the option of changing the

1: Modifying Your Fonts Page #3

Page 28

Fontographer User's Manual

weight of your character (or entire font) without affecting

the vertical or horizontal size of the character.

Go back to the “v” and select “Undo Change Weight” from

the Edit menu to undo the changes you performed in the

last exercise. Repeat the exercise above, but check

the “Don’t change vertical size” option before you

click “OK.”

Look at the difference in the two options. You can try the

option with the “Don’t change horizontal size” option next.

Now try the exercise with both options checked.

You can now apply the desired weight to the entire font, or

just selected characters. From the Font Window, use the

pointer tool to click and Shift-click on the desired

characters. (You can choose them all by choosing “Select

All” from the Edit Menu.) Then repeat the procedure above

to apply the selected changes to the desired characters.

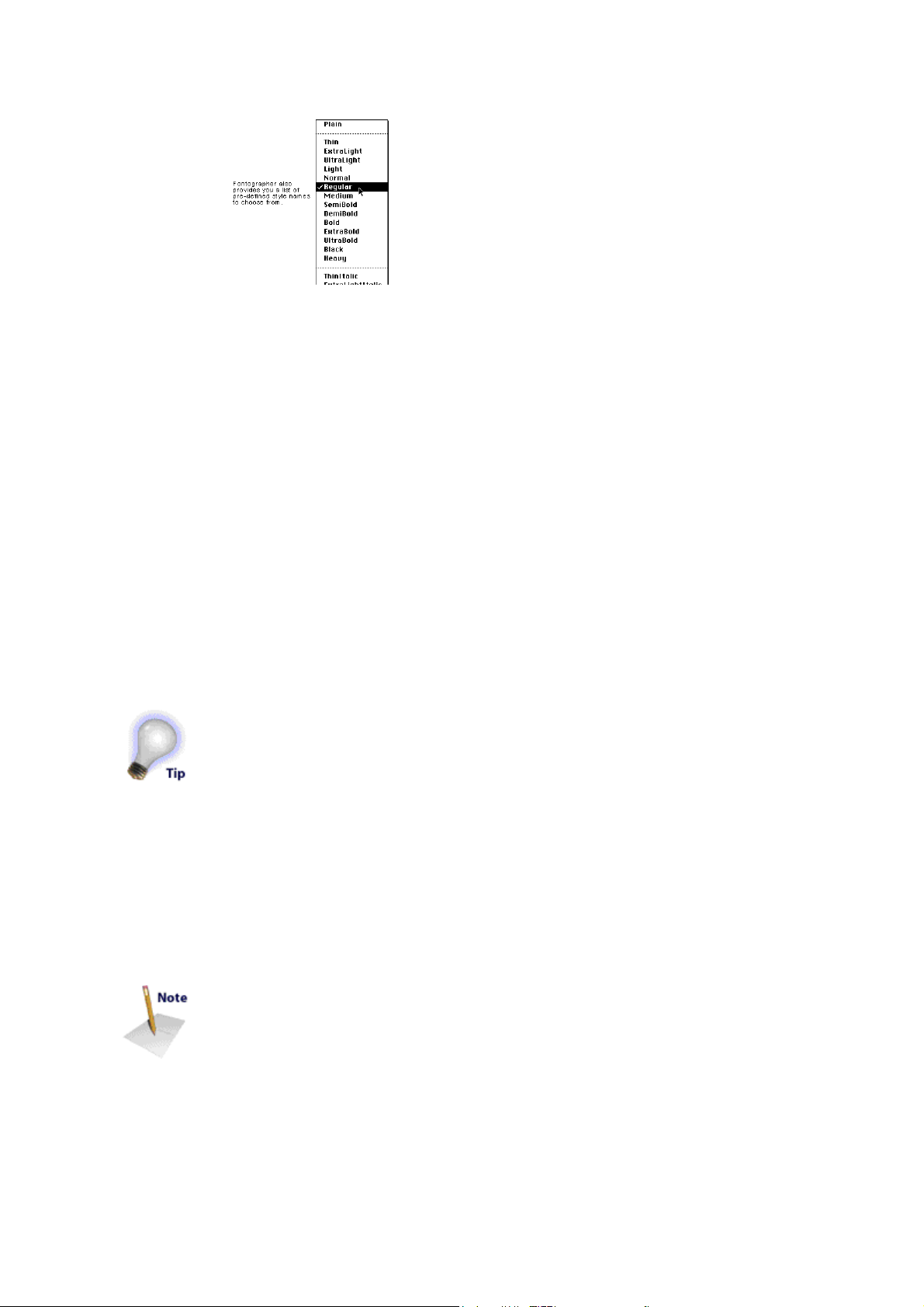

Naming your font

You can name your font by choosing “Font Info” (-General

on the PC) from the Element menu. The Font Information

dialog appears. For this exercise, name your font something

simple like “Garamond-Fat.” (Don’t forget the hyphen

before the Style Name.) For more information about

naming your font, refer to the section “The menu name” in

Chapter 7, “Generating and Exporting Fonts.”

1: Modifying Your Fonts Page #4

Page 29

Fontographer User's Manual

If you want to use a custom style name, be sure to let

Fontographer assign a standard style name first and then reassign your custom name. So, if you want to call your bolditalic version of a font “fat slanted,” use the pull-down menu

and select “bold italic” first, then change the style name

to “fat slanted.”

This will allow Fontographer to recognize and assign the

proper style to your custom name.

Be sure to name your font before you save your database

file and generate a font. Otherwise your fonts will end up

with unusable names like “Untitled.ttf” (for a TrueType

font), and you’ll have to start over.

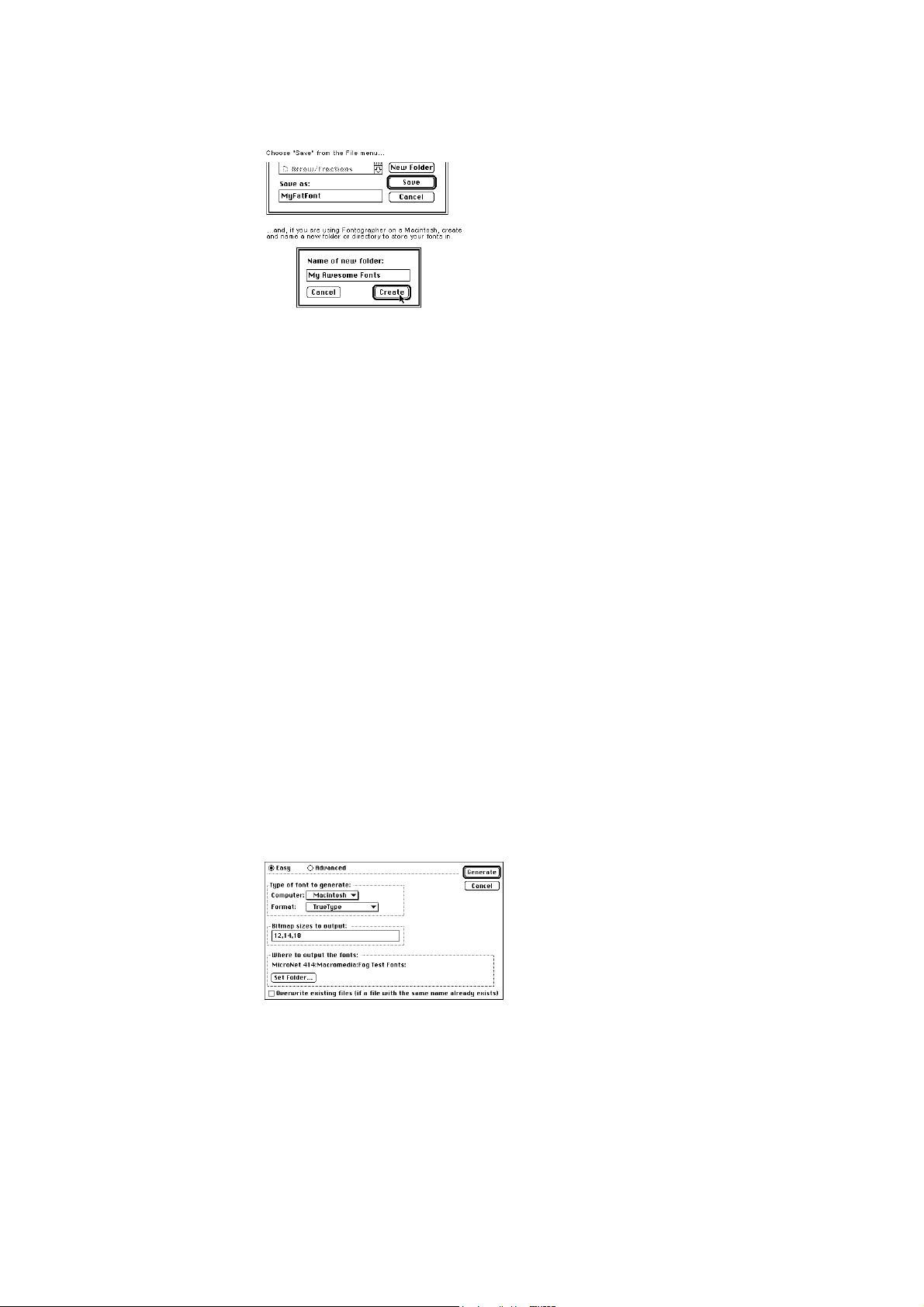

Saving your work

You save Fontographer database files via the Save or Save

As commands in the File menu. The database file is where

Fontographer stores all the parts needed to construct any

font. Just like you save documents in Microsoft Word, or

graphics in Macromedia FreeHand™, the database is

where you save your fonts in Fontographer.

The standard file saving dialog appears. You can name

your databases anything you like, because there’s no

relationship between the name of the actual font you’ll use

in your programs and the name of the database itself.

1. Choose “Save as” from the File menu.

Macintosh users have the option of creating and naming a

new folder to store a font in. You can save your font

directly to another folder, drive, or directory on all platforms.

2. Type in “MyFatFont.”

PC users will note that Fontographer automatically gives

you the name “MyFatFon.fog” if you also named

1: Modifying Your Fonts Page #5

Page 30

Fontographer User's Manual

it “MyFatFont” in Font Info.

Generating your font

After you save the file, it’s time to generate an installable

font. You will have to do this if you want to use the font in

another application besides Fontographer.

Fonts are composed of different files which you will need to

install before you can use the font. For more about installing

fonts, refer to Chapter 9, “Installing and Removing Fonts.”

1. Choose “Generate Font Files” from the File menu.

The Generate Font Files dialog offers a number of options

(including the ability to generate fonts for several

computer platforms), but for the purposes of this exercise

you’ll use the Easy mode. Choose the computer you’re

generating fonts for and select TrueType for the Format.

We’ve typed some commonly used bitmap sizes in our

example and you can do the same. However, bitmaps are

only necessary if you’ll be using a PostScript font on the

Macintosh.

The Set Folder/Directory button gives you the option of

generating your fonts directly into a specific folder. This

saves you the extra step of moving files into folders later.

The Overwrite existing files option lets you replace an

existing file (that has the same name) with a new file. If

you don’t choose this option (and have a font with the

1: Modifying Your Fonts Page #6

Page 31

Fontographer User's Manual

same name), Fontographer will create a new font with the

same name followed by a bullet ( ), on the Macintosh, or a

dollar sign ($) on the PC.

Installing the font

Since installing fonts is different depending on the platform

and operating system you’re using, we can’t really cover

this in a quick “how-to” here. If you need more information

about installing fonts, refer to Chapter 9 or your System’s

User’s Manual.

Using the font

Once you’ve installed the font, go to the application of your

choice, type some text, and select your font (just like you

would any other font) from the Font menu.

Creating an oblique font

By using Fontographer’s Skew feature, you can create your

own oblique font. You can consider this an easy way to

make an oblique typeface. Actually, it’s sort of like cheating

since an oblique font is just a right-slanted version of a

Roman typeface; a true italic typeface has redesigned

characters that compliment the face. But, skewing is a

really easy way to create a new typeface that can add

emphasis to your text.

1: Modifying Your Fonts Page #7

Page 32

Fontographer User's Manual

Again, Fontographer allows you to skew one, several, or all

characters at once. As in our previous example, we

recommend that you try out your modifications on one

character before you apply the transformation to the entire

font.

Follow the steps given in the “Change Weight” exercise to

open your font.

To skew a character:

1. Go to the Font Window and double-click on the

character “k” to open it.

2. Choose “Transform” from the Element menu.

3. Drag down in the “First transformation” pop-up

menu until you’ve selected the Skew option and

made sure the other pop-up menus say: “Do

nothing.”

Fontographer defaults to a horizontal skew value of -12

degrees (the appropriate angle for an oblique font,

depending on who you ask).

4. Click the Transform button, and Fontographer skews

the “k.”

Fontographer gives you the option of applying other

transformations at the same time you skew the character.

To apply more than one transformation:

1. Double-click on the “k” and select “Undo

Transform” from the Edit menu to undo your last

move.

2. Select “Skew” from the Transform dialog and

1: Modifying Your Fonts Page #8

Page 33

Fontographer User's Manual

enter -12 degrees Horizontal (leave Vertical at 0).

3. Then select “Scale” and enter “80” in the Horizontal

text box.

4. Select “Basepoint” from the Center

Transformations around pop-up menu.

5. Click “Transform.”

Fontographer skews and condenses the “k” at the same

time.

Try some of the other transformation options to see what

effects they have on your character.

Once you’ve finished trying out all the options, you can

apply the transformation to several characters or the entire

font, by selecting groups of characters in the Font Window.

Skewing multiple characters

You can skew, scale, flip, or move either a single character

or a range of characters. Select more than one character in

the Font Window by holding down the Shift key while

clicking on characters. Select a range of characters by

dragging through the characters. In this way you can apply

transformations to one, several, or all characters.

Creating a fraction using composite characters

1: Modifying Your Fonts Page #9

Page 34

Fontographer pastes the number “8” on top of the “3.”

Fontographer User's Manual

Have you ever checked out how many fractions are in your

font? If you have, you know that most commercial fonts

have a small number of fractions, if any. Historically, if you

wanted to type the fraction 3/8, you had to type the 3, the

forward slash, and the 8, and even then the fraction didn’t

look so hot! Fontographer makes it extremely easy to add

composite characters made up of more than one character

combined in a single character slot to your font. So you can

now have traditional fractions in all your fonts!

To create a fraction:

1. Go to the Font Window and double-click on the “3”

to open it.

2. Click on the “8” character slot in the Font Window

(it’s not necessary to open the Outline Window to

copy the character) and then select “Copy

Reference” from the Edit menu.

3. Click on the “3” Outline Window and

choose “Paste” from the Edit menu.

1: Modifying Your Fonts Page #10

Page 35

Fontographer User's Manual

Fontographer pastes the number “8” on top of the “3.”

4. Select everything in the Outline Window by

choosing “Select All” from the Edit menu.

5. Go to the Transform menu, select “Scale

Uniformly” as your first transformation, enter 60%,

and make sure all the other transformation pop-ups

say “Do nothing.”

Fontographer scales both characters to 60% of their

original size.

6. Position your pointer away from the characters, and

click on nothing to deselect everything (or simply

press the tab key, which always deselects

everything). Then click the mouse on the outline of

the “8.”

A box will appear around the number “8” (this represents

the composite character’s bounding box). Composite

characters do not show the points you normally see. (You

cannot edit points in a composite character unless you first

choose “Unlink Reference.”)

7. Drag the box containing the “8” toward the lower

right-hand corner.

8. Double-click on the path or on any point on the

number “3” to select all of it, and then move the “3”

toward the top left corner.

You can create the divisor line by copying the forward

1: Modifying Your Fonts Page #11

Page 36

Fontographer User's Manual

slash into your character. You can also draw the divisor

line if you prefer. However, it is often much easier to use

existing characters to create parts.

9. Select the forward-slash character in the Font

Window.

10. Choose “Copy” from the Edit menu.

11. Paste the forward-slash character into the “3”

character slot.

To change a reference character:

1. Open the Outline Window for the actual

character “8.”

2. Modify some part of it.

You’ll see any changes you make to the original eight

reflect in the denominator you created in your fraction

character.

Unlinking a reference character

Fontographer also lets you remove the link from any

composite character. This gives you access to the points in

the character as well as removing the link to the original

character.

To unlink a reference character:

1. Click on the fraction you created (in the “3”

character slot).

2. Choose “Unlink Reference” from the Edit menu.

As you can see in our illustration, the character’s points

are now visible and you can move them individually, or

together as a group.

Creating a ligature

1: Modifying Your Fonts Page #12

Page 37

Fontographer User's Manual

A ligature is a character made up of one or more

characters. Most commercial fonts have some commonly

used ligatures like “,” and “ú.” However, Fontographer

makes it easy to create ligatures of your own without

drawing a thing.

To create a ligature:

1. Open the Outline Window for the “f.”

2. Choose “Select All” and then choose “Duplicate” to

create another “f.”

3. Move the new “f” to the right.

4. Go back to the Font Window.

5. Copy the “l” into the same window using the “Copy

Reference” command from the Edit menu.

6. Move the referenced “l” to the right of the second “f.”

7. Choose “Unlink Reference” from the Edit menu.

8. Choose “Remove Overlap” from the Element menu.

Changing the character width

You probably noticed the vertical line that runs through the

second “f.” This is the character width line. Width is a

moveable vertical line which specifies the width of each

character. (Width is covered in more detail in Chapter 5.)

When you print a line of text, the origin line of the next

character is placed on top of the width line of the current

1: Modifying Your Fonts Page #13

Page 38

Fontographer User's Manual

character. Since you changed the contents of this

particular Outline Window, it’s important that you change

the width as well.

To change the character’s width:

1. Make sure you still have the Outline Window for

the “f” open.

2. You can choose “Preview” and turn off Show Points

from the View menu to get a better look at the

character if you like.

3. Move the width line with the selection pointer.

That’s all there is to it! So, if your font doesn’t contain the

ligature you want, you now know how to create your own

with Fontographer.

In some word processing and page layout programs you can

set the preferences to automatically substitute curly quotes

for straight ones, or the fl ligature if you type “fl.” For the

substitutions to occur, you’ll need to be sure to use an

Adobe encoded font.

Creating a condensed character or font

Fontographer has the ability to modify character images to

produce interesting special effects. You can create these

effects in either the Outline Window (on one particular

character) or the Font Window (on the whole font). For

example, you can create an oblique font by selecting all the

characters in the Font Window and skewing them -12

degrees (like we did in the earlier exercise “To skew a

character”). Or you can create an extended font, by

increasing the horizontal scaling factor of the font. Your

options are limitless.

You can also create a condensed font by scaling the

character 80% horizontally. Condensed versions of a font

1: Modifying Your Fonts Page #14

Page 39

Fontographer User's Manual

You can also create a condensed font by scaling the

character 80% horizontally. Condensed versions of a font

are the same height as their counterparts, but are narrower

to fit into a more compact space.

To create a condensed character:

1. Click on the Font Window to make it active, and

then press and hold the mouse button while you

drag through the characters “a” through “e.”

2. Choose “Transform” from the Element menu.

The Transform dialog appears.

As you can see from the screen shots on this page,

Fontographer scales the characters horizontally without

changing their height.

1: Modifying Your Fonts Page #15

Page 40

Fontographer User's Manual

Setting the basepoint

The baseline is the line upon which the letters sit. The

baseline position is always at a vertical location of zero. The

dot at the intersection of the origin line and baseline is the

basepoint.

The basepoint is used to accurately and quickly align points

and characters. The basepoint is generally at the

character’s origin (where the origin line and the baseline

intersect at 0,0); but, you can position the basepoint

anywhere. Fontographer allows you to set each character’s

basepoint differently. It can be moved as needed by

selecting the pointer tool and dragging it to a new location,

or by entering a specific horizontal and vertical location.

1: Modifying Your Fonts Page #16

Page 41

Fontographer User's Manual

For precise numeric entry, choose “Set Basepoint” from

the Points menu. To reset the basepoint back to the origin

point, choose “Reset Basepoint” from the Points menu.

If you select one point and choose “Set Basepoint,”

Fontographer will move the basepoint to that point.

However, if you select more than one point, Fontographer

will set the basepoint to the center of selection.

In the position display in the Outline Window, distance from

the basepoint is continuously updated as the pointer moves

within the drawing area. This on-screen measuring tool

makes it easy to measure character parts. Just place the

basepoint on a reference point of the character and watch

the position display as you move the pointer. Horizontal or

vertical alignment of points is very easy to check; set a

basepoint on one point then drag the other until the

horizontal or vertical delta is zero.

1: Modifying Your Fonts Page #17

Page 42

Fontographer User's Manual

Chapter Two

Creating New Fonts

Autotracing

Transformation Options

Guidelines

Creating a Stroked Font

Clean Up Paths

Creating Calligraphic Characters

Creating Variable Weight Characters

Blending Fonts to Create New Fonts

Somewhere in the dark recesses of a second-hand

bookstore, there is probably a well-worn and dust-covered

book that contains an old-fashioned typeface no one has

seen for years. Imagine being able to digitize that typeface

and transfer it to your documents. Or how about that logo

you created with a pen or pencil before you ever heard of a

graphics program? What about the beautiful effects that are

created with calligraphy fountain pens? Wouldn’t it be great

if you could use all of these in your word processor? With

Fontographer, any of these scenarios is simple.

Fontographer takes what used to be possible with only pen

and pencil, and puts it into the hands of the desktop designer.

Autotracing

The bitmap option is one of Fontographer’s most advanced

features. Autotracing is probably most useful for tracing

scanned images. Say you have an existing character, logo,

or image that you want to assign to a keystroke. On the

Macintosh, you can scan your image, save it in PICT

format, and place it into your Scrap-book or Clipboard.

2: Creating New Fonts Page #1

Page 43

A gray bounding box appears.

Fontographer User's Manual

Then you can paste your character into the Outline Window

(where it will be used like a background template) and let

Fontographer autotrace the image. On the PC, take your

scanned image to an application like FreeHand or Adobe

Streamline where you can either copy from the

application and paste into Fontographer and then autotrace,

or save/export as an EPS and then import into Fontographer.

To paste an image into the Template layer:

It’s remarkably easy to paste an image into the Template

(or background) layer. Select an image from the “Scanned

images/Scanned.bmp” file on your Fontographer CD. In

this example, we use a scanned Vivaldi “f.”

1. On the Macintosh, copy the image from the

Scrapbook or Clipboard and “Paste” it into the

Outline Window. On the PC, copy the image from

Paint/Paintbrush, and paste it into Fontographer’s

Outline Window.

Fontographer will automatically paste the image into the

Template layer where it will be shown as a grayed-out

image.

To move a Template image:

1. Click the Template layer to select it.

2. Click the template image with the selection pointer.

2: Creating New Fonts Page #2

Page 44

Fontographer User's Manual

A gray bounding box appears.

3. Move the image into place by positioning the

pointer inside the image, then dragging it to a new

location.

To resize a Template image:

1. Click the template image to select it.

2. Choose “Transform” from the Element menu

and “Scale uniformly” 90 percent.

Tracing an image

Once you have your image sized and positioned the way

you want, you can trace it

1. Make sure you are in the Outline layer.

2. Choose “Auto Trace” from the Element menu.

The Auto Trace dialog appears.

2: Creating New Fonts Page #3

Page 45

Fontographer User's Manual

You have two options: Easy and Advanced.

3. Choose “Easy” and keep the default Curve fit of “5.”

The tighter you set a curve fit, the more points will be

placed on your character. By having more points, the

tracing will more closely resemble the original image.

However, too many points will consume unnecessary

memory without appreciably improving the accuracy of

your path. It is better to use as few points as possible to

get the shape you desire.

When the Tracing progress dialog box finishes generating,

you will have a completely traced character in the

Outline Window.

You can cancel the tracing operation at any time by clicking

on the Cancel button or by typing Command-period, or Esc

on the PC.

Advanced tracing options

Fontographer’s Advanced tracing mode offers some

specific options.

Curve fit

Choosing an item from this pop-up will set all the other

controls in the dialog to recommended settings for Loose,

Normal, or Tight fit. Try changing the value of this pop-up a

2: Creating New Fonts Page #4

Page 46

Fontographer User's Manual

few times and see how the other controls respond. It might

give you an idea of how each slider affects the fit tightness.

If you change any of the other controls in the dialog, the

Curve Fit pop-up will automatically switch to “Custom” to

indicate that you have customized the values. Once you

have customized the settings you can always go back to

Loose, Normal, or Tight by changing the Curve Fit pop-up

back to one of these settings. You can switch back to

Custom as well. Normal is generally the best all-purpose

selection. Tight would be a good selection for more intricate

designs, while Loose would be good for characters with

straight angles (such as block letters) and poor quality

scans. Choose “Custom” if you want to set the Curve fit

options manually.

Allow curve fit errors

This control will have the largest affect on your tracing

results. A low value means Fontographer will allow fewer

curve fit errors, and you’ll get a very tight trace with more

points. A higher value means Fontographer will allow more

errors, and you’ll get a loose trace with fewer points.

Balance lines

This control will have very subtle, almost unnoticeable

affects on your tracing results. A low value means it will do

almost nothing. A high value means Fontographer will

attempt to align lines when it thinks it’s necessary. For

instance, it might try to align the left and right parts of the

crossbar in a “T” character.

Eliminate close points

This control can help eliminate redundant points (points that

are almost on top of each other). A low value means that

almost no points will be eliminated, and the shape of the

path will be the most accurate. A high value means that it

will eliminate as many points as necessary, but it may

slightly alter the shape of the curve in order to do so.

Make straight lines

This control has very subtle effects. It determines how

straight a curve should be before it is turned into a straight

line. This will never turn extremely curvy paths into straight

2: Creating New Fonts Page #5

Page 47

Fontographer User's Manual

lines; however, curves that appear to be almost straight to

begin with may be slightly modified so that they are

perfectly straight. A low setting for this control means

almost no curves will be straightened. A high value will

cause more curves to be straightened.

Look for cusps

When Fontographer traces an image it often finds places

where two paths join at a sharp angle. A join of this type is

called a cusp, and Fontographer will always place a corner

point at such a location. The “Look for cusps” control

determines how lenient Fontographer is in finding cusps, and

thus it will have an effect on how many corner points are

used in the tracing results. Setting this control to a low

value means it will find very few cusps, and the results

won’t have many corner points. Setting the control to a high

value means it will find many cusps, and the results will

have more corner points.

Treat nearly flat paths as straight lines

This check box is similar to the “Make straight lines”

control; however, it differs in a subtle way. The Make

straight lines control can help straighten any curves that are

nearly flat. However, the “Treat nearly flat paths as straight

lines” checkbox only straightens curves that are nearly flat,

and that only bend to one side. For example, this control can

straighten a C-shaped curve that bends to the left of the

straight line, but it can’t straighten an S-shaped curve that

bends to either side of the straight line. If you think the

difference between these two controls is too subtle for your

needs, then we recommend that you ignore this control and

just use the Make straight lines control.

Find extrema points

You should probably leave this checkbox turned on. It will

make sure that points are always placed at extrema points in

the tracing results, and this is recommended for PostScript

and TrueType fonts.

Transformation options

Fontographer’s transformation options are located under

Transform in the Element menu. Any of these can be

2: Creating New Fonts Page #6

Page 48

Fontographer User's Manual

applied from the Font Window or Outline Window. When

used from the Font Window, you can apply a transformation

to one, several, or all characters. On the other hand, in a

character’s Outline Window, you can only apply the

transformation to the selected points. If there are no

selected points, the transformation applies to the entire

character.

Flip

You can use the Flip transformation to flip the image to the

opposite side of an imaginary horizontal or vertical line.

You access the Flip transformation pop-up menu via the

Transform menu, or by double-clicking on the Flip tool in the

tool palette.

To flip selected items horizontally:

1. Select a character.

2. Choose “Flip” as the first transformation.

3. Click on the Horizontal radio button.

4. Click the Transform button.

To flip selected items vertically:

1. Choose “Flip” as the first transformation.

2. Click on the Vertical radio button.

3. Click the Transform button to apply the vertical flip.

2: Creating New Fonts Page #7

Page 49

Fontographer User's Manual

Move

The Move transformation can move whole characters, or a

specific point a specified horizontal and/or vertical amount.

To move selected items horizontally:

1. Choose “Move” as the first transformation.

2. Enter a value in the Horizontal text box.

3. Click “Transform” to move the image.

To move selected items vertically:

1. Choose “Move” as the first transformation.

2. Enter a value in the Vertical text box.

3. Click “Transform.”

Move an image horizontally and vertically by entering

2: Creating New Fonts Page #8

Page 50

Fontographer User's Manual

values in both text boxes.

Rotate

The Rotate option is used to rotate the selection a specified

number of degrees. Selected points rotate around the

reference point by a specified angle. Positive angles

indicate a counterclockwise rotation, while negative angles

specify a clockwise rotation.

You access the Rotate transformation pop-up via the

Transform menu or by double-clicking on the Rotate tool in

the tool palette.

To rotate a selected item:

1. Choose “Rotate” from the Transform pop-up.

2. Enter a rotation angle in the text box.

3. Click “Transform.”

Scale

There are two Scale pop-up menus: Scale and Scale

uniformly. Both of these options are used to increase or

decrease the size of an image by a specific scale factor.

The Scale option lets you scale horizontal and vertical

attributes independently of each other. You’ll find this

feature useful when you want to create condensed and

extended versions of a font, since you can apply the scaling

transformation to the entire font.

You access the Scale transformation pop-up via the

Transform menu or by double-clicking on the Scale tool in

the tool palette.

2: Creating New Fonts Page #9

Page 51

Fontographer User's Manual

To scale a character vertically:

1. Choose Scale from the pop-up menu.

2. Enter a vertical scaling value.

3. Click “Transform.”

To scale a character horizontally:

1. Choose the Scale pop-up menu.

2. Enter a horizontal scaling value.

3. Click “Transform.”

Scale uniformly

This option scales the entire image uniformly. If you select

a character and enter a scale factor of 50%, the image will

be reduced to 50% of its original size (both horizontally and

vertically). Doubling the size of the image would require a

scale factor of 200%.

To scale uniformly:

1. Choose the Scale uniformly pop-up menu.

2. Enter a scaling value in the text box.

2: Creating New Fonts Page #10

Page 52

Fontographer User's Manual

3. Click “Transform.”

Skew

The Skew option applies a slant to the image. Negative

values slant the character to the right, positive values to the

left. Vertical skewing can be used to create oblique

characters (sort of a “fake” italic). Italics are normally

skewed vertically by -12 degrees.

You access the Skew transformation pop-up menu via the

Transform menu or by double-clicking on the Skew tool in

the tool palette.

To skew selected characters:

1. Choose the Skew transformation pop-up menu.

2. Enter a skew value in either the horizontal or

vertical text box.

3. Click “Transform.”

Multiple transformations

There are times when you’ll probably want to do more than

one transformation at once. Fontographer lets you apply up

to four transformations (at one time) to one character, or

2: Creating New Fonts Page #11

Page 53

Fontographer User's Manual

the entire font.

Say you want to create a condensed oblique font and move

it closer to the baseline to compensate for the skew angle.

It’s easier than you probably think.

To apply multiple transformations:

1. Select a character.

2. Choose Transform from the Element menu.

3. Select up to four transformations.

4. Enter the transformation values.

5. Click “Transform.”

3-D transformations using the Transform dialog

Using the Transform dialog to apply 3-D transformations is

simpler if you use the tools to setup the transformation.

Double-clicking on the Perspective tool will bring up the

Transform dialog ready to apply a 3-D rotation

transformation. Option double-clicking on the selection tool

will bring up the Transform dialog ready to apply a 3-D

move transformation.

Let’s do an example of a 3-D rotation. In our example, we

will draw and then transform a square/circle .

To use the Scale tool:

1. Draw a square and a circle (holding the shift key

2: Creating New Fonts Page #12

Page 54

Fontographer User's Manual

down to constrain the tools) that start at the origin

point and extend to the descent.

2. Drag the width line on top of the rightmost point on

the circle.

3. Choose “Correct Path Direction from the Element

menu.

The character should look like this with Preview selected

from the View menu (or press Command- or Ctrl+L):

4. Choose “Select all” from the Edit menu.

5. Option or Alt double-click on the Scale tool to bring

up the Transform dialog with Scale uniformly as the

first transformation.

6. Choose “Center of Selection” from the Center

transformations around pop-up menu at the top of

the dialog.

7. Type in “90” into the text edit field and press return

or click Transform.

The character should look like this in Outline mode:

To use the Perspective tool:

1. Option double-click on the Perspective tool to bring

up the Perspective Setup dialog.

2: Creating New Fonts Page #13

Page 55

Fontographer User's Manual

2. Set the Distance to 1000 and the Point to Basepoint

and press Return or click OK.

This tells the Perspective tool that the image you see in

the Outline Window is being viewed as if you are 1000 em

units away from the Basepoint.

3. Choose “Select All” from the edit menu.

4. Choose “Set Basepoint” from the Points menu.

Your basepoint just moved to the center of the

square/circle, which is defined as the perspective

point in this example.

5. Choose Copy from the Edit menu. You will paste

this copy later in this example.

6. Click and hold the mouse on the origin line (the line

that extends from the bottom of the window to the

top if the window along the left side of the character).

7. Drag the mouse to the right while holding down the

shift key.

As you drag the mouse you will notice that the information

bar looks something like this:

8. Continue dragging to the right until the number

underneath the reads -90.

You have just rotated the selected points by -90 degrees in

the XZ Plane. You can also think of it as rotating around

the Y axis.

9. Choose Paste from the Edit menu. You now can

apply the next transformation to the copy of the

original.

10. Click down with the mouse on the baseline.

11. Now drag the mouse up while holding down the

shift key until the number under the symbol

reads 90.

2: Creating New Fonts Page #14

Page 56

Fontographer User's Manual

The character in the Outline Window should now look

something like this:

To apply 3-D transformations using the Transform dialog:

Let’s do an example of a 3-D rotation. To make things

simple, you will start where you left off using the

Perspective tool. For this example to work, the

square/circle being transformed should already be copied

into the clipboard.

1. Choose “Paste” from the Edit menu.

2. Choose the Perspective tool from the tool palette.

3. Click down with the mouse on the width line and

release the mouse button immediately. The mouse

click will be used as the center of the transformation

in the Transform dialog.

4. Double-click on the Perspective tool. The Transform

dialog will be brought up ready to apply a 3-D

rotation.

5. Choose “Last mouse click” from the Center

transformations around pop-up menu.

6. Set the XY angle to 0, the XZ angle to 90, and the

YZ angle to 0.

7. Set the Perspective Point pop-up to “Basepoint.”

Important: If you wish to setup additional transforms in

this dialog, then make sure you do the perspective

transform last. Any transforms that occur after the

perspective transform will not have a three-dimensional

appearance.

When you are done, the Transform dialog should look like

this:

2: Creating New Fonts Page #15

Page 57

Fontographer User's Manual

8. Press “Return.”

You have probably noticed that a three-dimensional box or

cube is being created. The previous set of steps created

the right side of cube. The next set of steps will create the

top side of cube.

1. Choose “Paste” from the Edit menu.

2. Click down on the ascent line.

3. Double-click on the Perspective tool.

4. Set the XZ angle to 0 and the YZ angle to -90.

5. Press “Return.”

If you have been following our example from the

beginning, then your character in the Outline Window

should look something like this:

To do a 3-D Move:

Let’s continue where we left off, creating a disjointed cube.

For this example to work, the square/circle you are

transforming should still be copied into the clipboard.

You will now create the back side of the cube by moving

the selected points backward (by 800 em units) into the 3rd

dimension.

1. Choose “Paste” from the Edit menu.

2. Option double-click on the selection tool to bring up

the Transform dialog.

2: Creating New Fonts Page #16

Page 58

Fontographer User's Manual

The dialog will come up showing Move and Perspective,

ready to do a three-dimensional move.

3. Set both the transformation (at the top of the dialog)

and the Perspective transform (at the bottom of the

dialog) to Basepoint.

4. Change the Horizontal and Vertical text edit fields

to “0” and change the depth edit text field to “800.”

5. Press “Return” or click OK.

6. Select “Preview, ” and voila:

Guidelines

Setting guidelines

The Guides layer is used to construct drawing guidelines

which are common to every character of the font (such as

the x-height line). The Guides layer is similar to the

Template layer, except it is drawn in light gray or green and

appears behind every character of the font. Guides are

purposely drawn in a lighter color so they can be

distinguished from the outline and template images.

Guidelines may be edited or created from any character’s

Outline Window. Change to the Guides layer by clicking on

its name in the Layers palette or by typing “g” when the

lock icon is in the locked state.

With the Guides layer active, you can edit or draw

guidelines with the standard drawing and editing tools.

Changes made to the Guides layer will appear in every

character in the font. You can undo changes made to the

2: Creating New Fonts Page #17

Page 59

Fontographer User's Manual

Guides layer just like you would in any other layer.

Setting guidelines from the Font Info dialog

Ascent and descent are already defined and can be reset

by choosing “Font Info” from the Element menu and typing

the values in the Ascent and Descent text boxes.

Adding new guidelines

Additional guidelines can be set two ways in the Guides layer.

To create a guideline:

1. Select the Guides layer.

2. Use the selection tool to drag vertically from the

baseline or horizontally from the origin line.

You can also create a guide by drawing it with any of the

drawing tools in Fontographer.

1. Select the Guides layer.

2. Click on the drawing tool of your choice to draw a

guideline.

Hiding guidelines

2: Creating New Fonts Page #18

Page 60

Fontographer User's Manual

You can hide the guides by checking on the Guides layer

checkbox to turn it off or (when the lock icon is locked) by

typing Option-G (Macintosh) or Caps Lock+G (on the PC).

Snap to guides

Choose “Snap to Guides” from the View menu. When

points are within a predetermined distance (you set this

value in the File menu Preferences’ Editing Behavior) from

the guideline, they snap or align to that guideline.

Creating a stroked font

Outline vs. stroked characters

Up until this point in the manual, we have been discussing

outline characters. You create outline characters by

drawing a path around the character’s perimeter. Stroked

characters are constructed by drawing just the centerline

path. PostScript draws these characters by sweeping a pen

along the path. The pen has a width called the stroke

weight which is made up of em units. As PostScript sweeps

2: Creating New Fonts Page #19

Page 61

Fontographer User's Manual

along the path, it paints a line that is so many units wide.

Any character which is constructed entirely of equal weight

strokes can be drawn as a stroked character. For example,

we drew the letters in this Fontographer logo as stroked

characters. You must generate these as Type 3 fonts, since

neither TrueType nor Type 1 fonts allow stroked characters.

Fontographer gives you complete control over the type of

pen you’ll use to create your stroked font. In addition to its

width, you can specify its appearance and behavior where

segments join. Also, since some people prefer drawing with

a pen (in real life situations), Fontographer makes it easy to

change the stroked character into an outline character (or

font).

Setting stroke attributes

Before you can create a stroked character, you will need to

change the attributes of the character from filled to stroked.

To change a filled character to stroked:

1. Choose “Selection Info” from the Element menu.

2. Turn off “Fill” and turn on “Stroke.”

3. Leave the Tint set at 100%.

4. Enter a pen Weight.

2: Creating New Fonts Page #20

Page 62

Round joins draw a circle with a diameter equal to the

Fontographer User's Manual

You’ll notice that Fontographer has two pop-up menus for

Cap and Join. In our example, we use Round on both since

we want the ends of the characters to be rounded. Each of

these options is discussed after this example.

5. Click “OK” and get ready to draw a character.

6. Choose a drawing tool, or one of the control point

tools.

7. Draw an “L.”

8. Turn on Preview to see what your character actually

looks like.

End caps and joins

There are three types of end caps: butt, round, and square.

Butt end caps stop right at the end point of the line.

Round end caps project a semicircle out from the end

point. This semicircle has a diameter equal to the stroke

weight and center point at the end point.

Square end caps project out one half the stroke weight in

the direction of the path.

There are three types of line joins: miter, round, and bevel.

Miter joins extend the outer edges of the lines until they

meet at an angle, like the corners of a picture frame.

2: Creating New Fonts Page #21

Page 63

Fontographer User's Manual

Round joins draw a circle with a diameter equal to the

stroke width at each bend.

Bevel joins are drawn as if the joining segments were

stroked with butt cap ends and the resulting notch filled with

a triangle.

Expand stroke

The Expand Stroke command is used to expand stroked

characters into contoured (outline) or filled characters.

To expand the stroke width:

1. Choose “Expand Stroke” from the Element menu.

2. Click “Normal pen.”

3. Enter a Pen width value.

4. Click “OK.”

Fontographer automatically changes the stroked character

into an outline character.