Page 1

Page 2

FCC COMPLIANCE STATEMENT

FOR AMERICAN USERS

This equipment generates and uses radio frequency energy and if not installed and used

properly, that is, in strict accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions, may cause

interference to radio and television reception. It has been type tested and found to comply

with the limits for a Class B computing device in accordance with the specifications in

Subpart J of Part 15 of FCC rules, which are designed to provide reasonable protection

against such interference in a residential installation. However, there is no guarantee that

interference will not occur in a particular installation. If this equipment does cause interference to radio or television reception, which can be determined by turning the equipment off and on, the user is encouraged to try to correct the interference by one or more of

the following measures:

- Reorient the receiving antenna

- Relocate the computer with respect to the receiver

- Move the computer into a different outlet so that computer and receiver are on

different branch circuits.

If necessary, the user should consult the dealer or an experienced radio/television technician for additional suggestions. The user may find the following booklet prepared by the

Federal Communications Commission helpful:

This booklet is available from the U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington DC

20402, Stock No. 004-000-00345-4.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system,

or transmitted, in any form or by any means, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Epson America, Inc. No patent liability is

assumed with respect to the use of the information contained herein. While every precaution

has been taken in the preparation of this book, Epson America, Inc. and the author assume no

responsibility for errors or omissions. Neither is any liability assumed for damages resulting

from the use of the information contained herein.

Baby printout on cover reprinted with permission of Apple Computer Inc., copyright 1984

Apple is a registered trademark of Apple Computer, Inc.

Centronics is a registered trademark of Data Computer Corporation.

Concept is a trademark of Corvus Systems, Inc.

DEC is a registered trademark of Digital Equipment Corporation.

FX-80, FX-100, RX-80, and RX-100 are trademarks of Epson America, Inc.

HX-20 Notebook Computer is a trademark of Epson America, Inc.

IBM-PC is a registered trademark of International Business Machines Corporation.

Microsoft is a trademark of Microsoft Corporation.

NEC is the NEC Information Systems, Inc., a subsidiary of Nippon Electronic Company, Ltd.

QX-10 is a trademark of Epson America, Inc.

TRS-80 is a registered trademark of Radio Shack, a division of Tandy Corporation.

80 Micro is published by Wayne Green Publishers.

“How to Identify and Resolve Radio-TV Interference Problems.”

Copyright© 1984 by Epson America, Inc.

Torrance, California 90505

ii

P8294017

Page 3

Preface

The User’s Manual for the FX Series printers consists of two volumes: Tutorial and Reference. This volume, the Tutorial, is arranged

in the following logical groupings:

Introduction (for everyone)

Programmer’s Easy Lesson (for experienced users)

Hardware description: Chapter 1

Software introduction: Chapter 2

Control of the way characters look: Chapters 3 to 6

Control of the way pages look: Chapters 7 to 9

Printer graphics: Chapters 10 to

User-defined characters: Chapters 15 and 16

Using everything together: Chapter 17

A complete table of contents for this volume is after this preface. For

your convenience, there is an index at the end of each volume covering the complete two-volume set. You can therefore find all the references to any topic in either one.

Conventions Used in This Manual

14

We provide sample BASIC programs that allow you to see how

various commands control the printer’s capabilities. Frequently we

start with a few program lines and then make several changes and

additions to end up with a substantial program. We suggest that you

use your SAVE command after each change to prevent losing programs because of power fluctuations or other accidents. When you

can RUN a program, we show the results you should expect.

In our sample programs, we use Microsoft’” BASIC, which is

widely used in personal computers. Because there are several slightly

different versions of Microsoft BASIC and because your computer

iii

Page 4

may use a version of BASIC other than Microsoft, you may need to

modify some of the programs in this manual before they will run.

Appendix F offers help, as do the next several paragraphs.

Methods for sending BASIC print and listing commands to the

screen and to the printer vary widely. We have used PRINT and LIST

as the commands for the screen display, and LPRINT and LLIST as

commands for the printer. You may have to change those to the form

used by your system.

If, for example, your system uses the

you will need to change all instances of PRINT in our programs. Since

we use PRINT to report progress to your screen and that command

does not affect the printing, the easiest modification is to delete such

PRINT statements. For example,

PR#1 and

PR#0 commands,

38 FOR D=1 TO 17: PRINT "ROW";D

would become:

39 FOR D=1 TO 17

because the only purpose of the PRINT statement is to display on the

screen information that is not absolutely essential to the program.

Any BASIC system automatically provides a carriage return (and

some BASICS add a line feed) after every program line that includes a

PRINT or LPRINT command, whether that line prints text or not. To

prevent the carriage return, we have you place a semicolon at the end

of such program lines. You will see this technique throughout the

manual.

A few versions of BASIC use semicolons between any two control

codes that fall on one program line, as in:

LPRINT CHR$(27);CHR$(52)

If you use such a version of BASIC, you will need to add semicolons

as appropriate.

After the ESCape code-CHR$(27)-the FX always expects another code. The second code tells the printer which mode to turn on or

off, and you may enter it in either of two formats. One format is like

the ESCape code-you use a number in parentheses after CHR$, such

as CHR$(l). The other format is shorter since it uses only an alphanumeric symbol within quotation marks, such as “E” or “@“. We usually

use the latter format.

iv

Page 5

This format allows you to shorten a program line by combining a

command and its print string. In the case of Double-Strike, for instance, the quoted letter “G” turns the mode on and "H" turns it off. To

see how combining the code with a print string works, compare:

10 LPRINT CHR$(27)"G";"DOUBLE-STRIKE PRINT"

with:

10 LPRINT CHR$(27)"GDOUBLE-STRIKE PRINT"

The second program line may look peculiar, but it gives the same

output that the first version does. The G is not printed on the paper;

instead, it is interpreted by the printer as part of the ESCape sequence.

In long programs with DATA statements or subroutines, we use

END after the line that is executed last, but older BASIC systems require the use of STOP at such points. If yours is one of these, you

should change our ENDS to STOPS.

When the presence of one or more blank spaces in a program line is

especially important, we use a special character ( , pronounced

‘blank’) to represent the spaces. This makes it easier for you to count

the number you need. For example, the following:

SAMPLE STRING"

means that you should type in one blank space for each

"

The use of the symbol makes it easy for you to count the eight spaces

needed between the quotation mark and the beginning of the first

word. The also calls your attention to single blank spaces that are

needed immediately before or after a quotation mark. For example,

the following makes clear that you must type one space between the

quotation mark and the word “and’:

SAMPLE STRING"

LPRINT " AND EASY TO TURN OFF"

When we include a programming REMark in a program line, it is

always preceded by an apostrophe (‘), the short form of the BASIC

command, REM. For example, we use:

10 LPRINT CHR$(27)"@"

and

99

' Data lines for graphics

' Reset Code

V

Page 6

The computer ignores these remarks; they merely serve to help programmers understand at a glance the way a program is working. You

may type them in or not, depending on whether you think you will

want them in the future.

We use the caret symbol (^) to indicate exponents. For example:

x =

Y^2

means let X equal Y raised to the second power. Some computer systems use an up-arrow (t), which prints as a left bracket ([) on FX

printers.

At the end of each chapter, a Summary section provides a concise

review of the chapter’s subject matter and a list of the control codes (if

any) that have been covered. For listings of the control codes in numerical order and in functional groupings, see Appendixes B and C.

When we refer to an FX mode by name, we capitalize it:

Compressed Mode

Italic Mode

Pica Mode

Script Modes

and, for clarity, we capitalize such names even when the word mode

does not appear: Script characters and Italic print.

vi

Page 7

FX Series Printer User’s Manual

Volume

Preface

Conventions Used in This Manual

List of Figures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

List of Tables

Introduction

Inside the Printer

Inside This Manual

Programmer’s Easy Lesson

First Steps

Ticket Program

Ticket Program Description

1

The FX Printers

Additional Supplies and Accessories

Printer Location

Printer Preparation

Paper Loading

Starting Up

......................................

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

..................................

..............................

....................................

...............................

...............................

...............................

Paper separator

Covers

Manual-feed knob

DIP switches

Ribbon Installation

FX-80: built-in tractor feed

FX-80 and FX-100: friction feed

FX-80 and FX-100: removable

Top-of-form position

Paper-thickness lever

Control panel

The FX tests itself

....................................

..............................

................................

tractor unit (optional on the FX-80)

...................................

...............................

1

Contents

................

............................

......................

.....................

..............

............................

.............................

...........................

..........................

....................

................

...........

.........................

.........................

............................

iii

iii

xiii

xvii

1

2

2

7

7

8

10

13

16

16

17

17

18

19

20

23

24

24

28

29

32

32

32

35

35

vii

Page 8

BASIC and the Printer

2

BASIC Communications

Character strings

BASIC print commands

ASCII and BASIC basics

Control codes

...............................

.........................

........................

............................

......................

......................

Escape-CHR$(27)-and other CHR$ commands

Change Commands

Reset Code

Mode cancelling codes

DELete and CANcel

............................

.................................

........................

.........................

Alternate Formats for ESCape Sequences

Summary

....................................

..........

37

38

39

39

40

41

42

44

45

45

46

46

47

3 Print Pitches

Dot-Matrix Printing

Main columns

..................................

............................ 49

..............................

Intermediate positions

Modes for Pitches

Pica and Elite Modes

Compressed Mode

Mode priorities

.............................

......................... 52

...........................

.............................

Pitch Mode Combinations

Expanded Mode

.............................

Multiple print pitches on one line

Summary

4

Print Quality

Bold Modes

Double-StrikeMode

Emphasized Mode

Proportional Mode

Mixing Modes

Summary

Dress-Up Modes and Master Select

5

Four Modes

Underline Mode

....................................

.................................

..................................

.........................

...........................

..........................

................................

....................................

...................................

.............................

Script Modes: Super and Sub

Italic Mode

.................................

More Mode Combinations

Master Select

...............................

Master Select combinations

Summary

....................................

........................

......................

...............

............... 69

..................

......................

...................

49

50

51

52

53

55

56

56

58

59

61

61

61

62

64

65

66

69

69

71

72

73

73

76

78

viii

Page 9

Special Printing Features

6

Backspace

....................................

Overstrikes

Offsets

.....................................

Unidirectional Mode

International Characters

Special Speeds

Half-SpeedMode

Immediate-Print Mode (FX-80 only)

Summary

....................................

........................

.................................

...........................

........................

................................

............................

............

81

81

81

82

83

85

88

89

89

90

7

Line Spacing and Line Feeds

Line Spacing

..................................

Preset line spacing

Variable line spacing

Microscopic line spacing

Line Feeds

....................................

One-time, immediate line feed

Reverse feed (FX-80 only)

Summary

Forms Control

8

....................................

................................

Form Length Control

Form feed distance

Not-so-standard forms

Paper Perforation Skip

Skip command

DIP switch skip

..............................

.............................

Single-Sheet Adjustment

Summary

....................................

.....................

...........................

.........................

...................... 98

.................

.....................

...........................

...........................

.......................

.........................

........................

93

93

93

95

98

99

99

101

103

103

103

105

107

107

109

109

110

ix

Page 10

Margins and Tabs

9

Margins..

Left margin

Margins and pitches

Right margin

Both margins

Tabs..

Horizontal tab usage

Variable horizontal tabs

Vertical tab usage

Ordinary vertical tabs

Vertical tab channels

Summary

.............................

....................................

.................................

.........................

...............................

...............................

.......................................

.........................

......................

............................

........................

.........................

....................................

113

113

113

114

116

118

118

119

121

122

123

126

128

10

Introduction to Dot Graphics

Dots and Matrixes

Print Head

.............................

Graphics Mode

Pin Labels

....................................

.............................

...............................

First Graphics Programs

Straight line

Slash

......................................

Large caret

Wave pattern

Diamond pattern

Summary

Varieties of Graphics Density

11

................................

.................................

...............................

............................

....................................

Graphics Programming Tips

Graphics and the Reset Code

Graphics and low ASCII codes

Density Varieties

..............................

High-Speed Double-Density Graphics Mode

Low-Speed Double-Density Graphics Mode

Quadruple-Density Graphics Mode

Moredensities

..............................

More Graphics Programming Tips

Reassigning alternate graphics codes

Nine-Pin Graphics Mode

Pin Combination Patterns

Repeated patterns

...........................

Repeated DATA numbers

Summary

....................................

....................

........................

....................

.....................

..................

................

.....

......

.............

...............

............

.....................

.......................

.....................

131

131

132

134

135

137

138

139

139

140

141

142

143

143

144

144

145

146

148

149

149

150

150

152

154

155

156

157

x

Page 11

12

Design Your Own Graphics

Planning

Process

..............................

STRATA Program

Three-Dimensional Program

First version of 3D program

Other versions

Summary

....................................

..............................

.....................

159

159

............................. 160

....................

...................

163

165

170

171

Plotter Graphics

13

Arrays

.......................................

...............................

DIMension and arrays

Filling arrays

Circle Plotting

Ones become dots

Pin firing sequences

Code solutions

Higher resolution

Reflections

Exploding galaxy

Big bang

Summary

14

Symmetrical Graphics Patterns

...............................

................................ 177

...........................

..........................

.............................. 180

............................

................................. 183

............................

...................................

....................................

Pin Pattern Calculation

Graphics Width Settings

Pattern Printout

Variations

Summary

15

User-Defined Characters

Preparation

Character Definition

Design

.....................................

Dots into DATA

Attribute byte

Proportional print

...............................

....................................

....................................

.................................

...........................

............................ 202

..............................

...........................

Printing User-Defined Characters

Downloading Command

Defining More Characters

Redefining Control Codes

Mode Strings

STRATA

Summary

.................................

.....................................

....................................

.......................

..................

.........................

........................

........................

.................

....................... 207

.......................

.......................

173

173

176

176

178

179

181

184

185

187

189

192

193

193

195

197

199

200

200

201

203

203

205

207

208

211

212

212

xi

Page 12

16

Combining User-Defined Characters

Large Letters: Double Wide

Large Letters: Double High

.....................

......................

Giant Letters: Double High and Double Wide

Core Sets

Line Graphics

Summary

....................................

.................................

....................................

..............

......

215

215

217

217

223

225

226

17

Business Application

...........................

Preparation .................................

Barchart

Statement Form

999 REM: The End

.....................................

...............................

............................

Index ......................................... 239

227

227

227

231

238

xii

Page 13

List of Figures

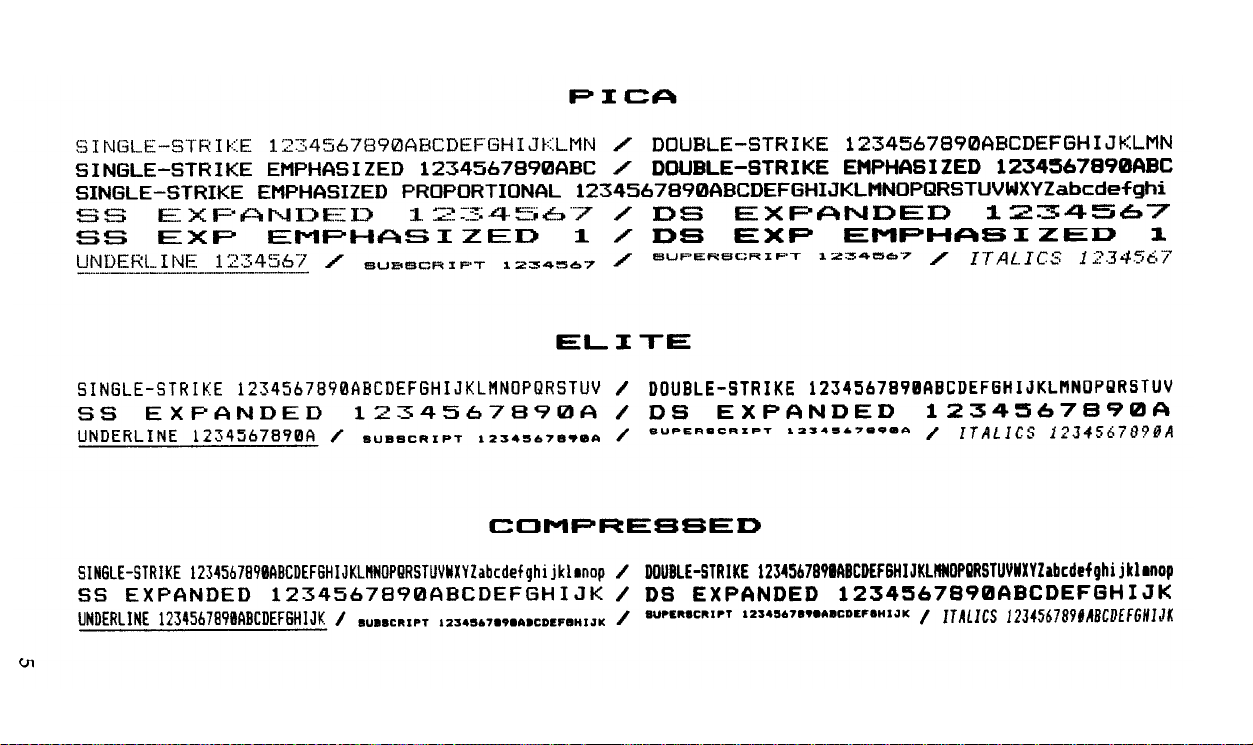

Easy-1

Easy-2

1-1

1-2

1-3

1-4

1-5

1-6

1-7

1-8

1-9

1-10

1-11

1-12

1-13

1-14

1-15

1-16

1-17

1-18

1-19

1-20

1-21

1-22

FX ticket program

Ticket to success

The FX-80 and FX-100 printers

Printer parts

Paperpath

Paper separator

Protective lids

Tractor covers

Manual-feed knob

DIP switch vent

DIP switch location

DIP switch factory settings

Ribbon insertion

Printer readied for paper insertion

Pin feeder adjustment

Loading the FX-80

Tractor unit release

Tractor unit installation

Hook and stud

Adjusting the pin feeders

Top of form

Paper thickness adjustment

Cable connection

Sample automatic test

................................

..........................

...........................

...............

...............................

............................

.............................

.............................

..........................

............................

.........................

..................

...........................

.............

.......................

..........................

.........................

......................

...........................

....................

...............................

..................

...........................

.......................

8

10

14

15

17

18

19

19

20

21

22

22

25

26

27

27

28

30

30

31

33

34

35

36

2-1

3-1

3-2

3-3

3-4

3-5

3-6

3-7

4-1

4-2

4-3

Italic listing

Dot-matrix characters

Theprinthead

Main columns

Intermediate positions

Pica and Elite letters

Pitch comparison

Pica and Expanded letters

Single-Strike and Double-Strike letters . . . . . . . . .

Single-Strike, Expanded and Emphasized letters .

Mode priorities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

.......................

.............................

.............................

.......................

........................

..........................

....................

43

49

50

51

51

53

53

57

62

63

66

xiii

Page 14

5-1

5-2

5-3

Master Select Program

Master Select choices

.......................

Dress-up combinations

......................

......................

74

75

77

6-1

6-2

7-1

7-2

7-3

8-1

8-2

8-3

8-4

9-1

9-2

9-3

9-4

9-5

9-6

9-7

9-8

9-9

9-10

9-11

9-12

9-13

Bidirectional line

Unidirectional line

Default line spacing

Cascading STAIR STEPS

Staggering STAIR STEPS

Setting the top of form

Two-inch form feed

Two-line form feed

Standardskip

Left margin setting

Listing at new margin

Absolute left margin

Right margin set incorrectly

Right margin set correctly

Default horizontal tabs

Tabs with text and numbers

Variable horizontal tabs

Absolute horizontal tabs

Ordinary vertical tabs

Text at tab stop

Absolute vertical tabs

...........................

..........................

.........................

....................

....................

......................

.........................

.........................

.............................

.........................

.......................

........................

..................

...................

......................

..................

.....................

....................

......................

............................

.......................

Printout of multipage channels

...............

84

84

94

96

100

104

106

106

108

114

115

115

116

117

119

120

121

122

124

125

126

128

10-1

10-2

10-3

10-4

11-1

11-2

11-3

11-4

11-5

11-6

11-7

xiv

Pins numbered sequentially

Dot pattern in two line spacings

Pins labelled uniquely

Pin combinations

..........................

High-Speed Double-Density dots

No overlapping dots

Overlapping dots

Seven density modes

Nine-pin usage

........................

..........................

........................

.............................

Printout using bottom pin

Curling design

.............................

..................

..............

.......................

..............

...................

133

133

136

137

147

147

148

150

153

154

155

Page 15

12-1

12-2

12-3

12-4

12-5

12-6

12-7

12-8

12-9

12-10

12-11

STRATA layout

STRATA logo

STRATA program

...........................

.............................

..........................

Corner of the FX-80 design

FX-80 figure

Program for FX-80 figure

FX-100 figure

...............................

....................

..............................

Program for FX-100 figure

More distinct version

Most distict version

Reversed version

.......................

.........................

...........................

...................

...................

161

162

163

164

168

168

169

170

171

172

172

13-1

13-2

13-3

13-4

13-5

13-6

13-7

14-1

14-2

14-3

14-4

14-5

14-6

15-1

15-2

15-3

15-4

15-5

16-1

16-2

16-3

16-4

16-5

16-6

16-7

16-8

16-9

Computer memory as sketch pad

Array in memory and on paper

.............

...............

Ones and zeros become dots and blanks

Labelled cell

Plotting a circle

Displaying an array

Divide and conquer

Printing the array contents

Pattern sets

Program for SYMMETRY

Symmetric pattern 1

Symmetric pattern 2

Symmetric pattern 3

ROM and user-defined characters

User-defined E

Incorrectly designed E

Pins chosen by attribute byte

Attribute byte conversions

Side-by-side characters

Double high and wide character

Program for giant G

Giant G

Data for AMES

Games seem same

Messages in three pitches

Tracks

Interlace

...............................

............................

........................

........................

...................

...............................

...................

........................

........................

........................

.............

.............................

.......................

.................

...................

......................

..............

........................

..................................

............................

..........................

....................

....................................

..................................

.......

174

174

175

175

177

178

182

191

191

194

195

196

196

199

201

202

203

204

216

218

220

221

222

222

223

224

225

xv

Page 16

17-1

17-2

17-3

17-4

Barchart

..................................

Program for BARCHART

Statement form

............................

Program for STATEMENT

...................

..................

228

230

232

234

xvi

Page 17

List of Tables

1-1

2-1

2-2

2-3

3-1

4-1

5-1

5-2

6-1

6-2

6-3

6-4

7-1

11-1

14-1

DIP switch functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Several computers’ print LIST commands . . . . . .

Several computers’ printer activating commands .

ASCII codes on the FX . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Summary of print pitches . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Summary of modes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Master Select Quick Reference Chart

Print types

Some special characters

................................

..................... 85

International characters in Roman typeface

International characters in Italic typeface

International DIP switch settings

..........

.....

.......

..............

Line-spacing commands . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Graphics Modes

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Variables for SYMMETRY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

23

38

40

42

60

67

76

78

87

87

88

102

151

190

15-1

16-1

International character locations . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

ASCII pattern

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

210

219

xvii

Page 18

Introduction

FX Features

Epson’s MX series of printers attracted enough attention to become

the most popular line of printers in the industry. Our FX printers fol-

low in the same grand tradition. The FX printers’ power-packed

assortment of features includes:

l

Upward compatibility with most MX III features

l

Several different print modes that can be combined to produce a

variety of print styles. These include:

Roman and Italic print fonts

Six different print pitches

Two kinds of bold printing

l

Master Select feature for instant use of any one of

combinations

l

Proportionally spaced characters for professional looking documents

l

Easy-to-use Underline and Super/Subscript Modes

16

popular print

l

Detailed forms handling capability, including the setting of horizontal and vertical tabs, margins, form length, a skip-over-perforation

feature, and variable line feeds

l

Up to 233 characters per line with the FX-100™ for spreadsheet users

l

User-definable character sets. With this powerful feature you can

create your own alphabets and special symbols

l

High-resolution graphics capability with six densities to let you create your own charts, diagrams, figures, and illustrations

l

International character sets

l

Typewriter simulation mode with the FX-80™

Page 19

l

Program debugging mode (hexadecimal dump of codes received

from the computer)

l

Fast print speed-160 characters per second-for rapid processing

of documents

l

2K print buffer for smooth operation

l

Adjustable tractor unit for narrow forms

l

Both friction- and tractor-feed capability

l

Replaceable print head

l

Easy-to-reach DIP switches to customize printer features.

l

Epson reliability, quality, and support

In short, the FX is loaded with features

that

will challenge your ability

to put them to work. This manual can help you use one or all of them.

Inside the Printer

The FX printers contain two kinds of internal memory: ROM (Read

Only Memory) and RAM (Random Access Memory). There are 12K

bytes (approximately 12,000 characters) of ROM. This unchangeable

memory contains all the logic required for the various print features as

well as the patterns for all the built-in character sets.

The FX also contains a RAM memory buffer that stores up to 2K

bytes of text and printer commands as they are received from the computer. This frees your computer so that you can continue working

while the FX is printing. You can also use RAM another way; you can

define your own set of characters and then store them in RAM so that

you can print them at will.

It is always tempting (though not always wise) to start playing with

a new printer the instant it is out of the box. Because the FX is a sophis-

ticated piece of equipment, it is important that you understand what

the printer will do and how to operate it before you start printing.

Inside This Manual

This manual will guide you on a carefully planned tour of the vari-

ous features of the FX printers. In these pages, you

use your computer to control the printer for a large variety of applications.

2

can

learn how to

Page 20

You can use this manual as a reference, a tutorial study guide, or

some combination of the two.

l

For those of you who want to use the printer for one simple application (like listing BASIC programs or using a word processing package), a description of the hardware and an overview of the software

may be all that’s necessary. In this case, you need only Chapter

1,

the Quick Reference Card at the back of Volume 2, and a knowl-

edge of the program you are using. You can always learn about the

FX’s advanced features at a later time. (You might, for instance,

someday want to modify a word processing software package so

that its printer driver uses special FX features.) The lessons will be

waiting for you.

l

For those who prefer to roll up their sleeves and see how the printer

works, we’ve included sample programs to demonstrate each of the

printer’s features.

l

For those who want only a quick and easy reference, the comprehensive Table of Contents, the Appendixes, and the Index provide

ready access to information.

l

For computer professionals and other experienced users who simply

can’t wait to find out what the printer will do, regardless of the

consequences, we have a special section entitled “Programmer’s

Easy Lesson.” It gets you up and running fast, then turns you loose

on a program that demonstrates several of the printer’s features.

This program, the Appendixes, and the Quick Reference Card will

bring you quickly up to speed.

l

For those who are already familiar with the MX or RX series of

printers, Appendix E provides a summary of the differences

between the FX, the RX, and the MX.

3

Page 21

Think of the manual as your personal guide in your exploration of

the FX’s many features.

For a preview of what your programs can produce, take a look at the

following potpourri of print modes and graphics.

4

Page 22

Page 23

Page 24

Programmer’s Easy Lesson

Before you start, note that we haven’t claimed that one easy lesson

will make you an FX maestro. It takes more than one lesson to learn

the full value of the feature-packed FX printer. In fact, the more time

you spend with this manual, the more your printer will cooperate

with your every command. But some of you want to see something

from a new printer right now-no matter what. The next few pages

are especially for you.

If you get stuck, the proper set-up procedures are covered in full in

Chapter 1.

First Steps

1. Make all connections with the power OFF! Connect your FX to

your computer via the printer cable that you purchased separately.

(Some computers require special printer interface boards, also purchased separately).

2. To use continuous-feed printer paper with pin-feed holes, set the

friction-control lever and the paper bail toward the front of the

printer. If you are using the FX-80, pull the paper under the plastic

separator and through the paper path. If you are using the FX-100,

you may need to first install the tractor unit, then pull the paper

under it. In case the paper starts to jam on either model, refer to

Chapter 1 for tips on inserting paper. As you straighten the paper,

you will probably need to adjust the pin feeders.

To use either a single sheet of paper or roll paper without pin-

feed holes on the FX-80, first move the pin feeders out of the way. If

a tractor unit is installed on your FX-100, you will need to remove

it. Then, for either model, push the friction-control lever toward

the rear of the printer, pull the paper bail forward, and insert the

paper under the plastic separator. Use the manual-feed knob to

7

Page 25

feed the paper through. If you use single sheets of paper, the paper-

out sensor will cause a beep and stop the printing whenever the

bottom edge passes the sensor. You can shut off the sensor by

changing DIP switches as shown in Chapter

3.

Turn the printer and computer on and load a short BASIC program. Then send a listing to the printer (using LLIST, LIST “I”‘, or

whatever your computer’s listing command is). You should get a

single-spaced listing. If the printout is double-spaced or printed

without line spacing, you’ll have to change a DIP switch.

Since there are many implementations of the BASIC programming language, it is impossible to write one set of programs that

will work on every computer system. This means you may need to

modify our programs to suit your system. In Appendix F we discuss such compatibility problems and suggest solutions for several

popular computers.

1.

Ticket Program

Here is an example program, written in BASIC, that shows off a lot

of the FX printer’s features. The program can give you a good survey

of print control. If you don’t understand one or more features, you

can check the index to find what part of this manual covers it.

10 N=29: E$=CHR$(27): H$=CHR$(137)

20 LPRINT E$"1";E$"D"CHR$(26)CHR$(1);

30

LPRINT E$":"CHR$(0)CHR$(0)CHR$(0);

40 LPRINT E$"%"CHR$(1)CHR$(0);

50 LPRINT E$"&"CHR$(0)"0:";

60 FOR Y=1 TO 11: LPRINT CHR$(11);

70 FOR X=1 TO 11: READ D: LPRINT CHR$(D);: NEXT X

80 NEXT Y: LPRINT E$"U1";

90 FOR X=1 TO N: LPRINT CHR$(95);: NEXT X:

LPRINT E$"A"CHR$(6)

100 LPRINT "7"H$" 9";E$"1"

110 LPRINT "7 ";:

FOR X=1 TO 25: LPRINT ":";:

NEXT X: LPRINT H$" 9"

120 LPRINT "7 :"H$": 9"

Figure Easy-1. FX ticket program

8

Page 26

Page 27

Ticket Program Description

This is not a complete explanation of the program. That’s what the

rest of the manual is for. But this brief, line-by-line description should

help those of you who wish to analyze the program.

10 Stores values in variables for easy access. E$ holds the ESCape

code, CHR$(27).

20 Uses ESCape "1" to set the line spacing to 7/2X-inch and the

ESCape “D” sequence to set a horizontal tab stop at column 26.

30 Uses the ESCape

set into RAM.

40

Designates RAM as the source for the active character set.

50 Prepares the printer to redefine characters “0” through “:“.

60 Sets a counter for the 11 letters being defined, and selects the

attribute byte of each new character.

70 Reads the data that defines the letters

15 for additional information on lines 30 through 70.)

80 Turns on the Unidirectional Print Mode.

90 Prints the top of the ticket and sets the line spacing to 6/72-inch.

100 Prints the newly defined symbol “7” (left ticket border), tabs to

the next stop, prints the other border (9) and sets the line spacing

back to 7/72-inch.

":" sequence to copy the entire ROM character

(11

sets of ll). (See Chapter

10

Page 28

110

Prints the outside border, then the top of the inside border (which

was defined as the “:” character).

120 Prints another line of borders.

130 Prints more borders, then uses the Master Select to turn on

Emphasized Double-Strike Pica. Also turns on Italic and Under-

line Modes.

140

Prints TICKET TO SUCCESS, then resets the FX to its defaults,

including Pica, but does not affect the redefined characters.

150 Produces two more border lines.

160

Prints the upper half of the FX letters in Expanded Emphasized

printing. The user-defined character 0 produces the top of the F

and 2 produces the top of the X.

170 Turns off Expanded and Emphasized Modes and prints SERIES in

Superscript Mode and then prints the right side of the border.

180 Prints the bottom half of the FX letters.

190 Turns OFF the codes, prints PRINTERS in Subscript, then prints

a border.

200 Prints borders.

210 Prints borders, then switches to Compressed and prints BY. Sets,

with ESCape ”!X”, Emphasized Double-Strike Pica, and prints

EPSON. This new mode automatically turns off Compressed.

220 Sets Superscript Mode (Escape “SO”), returns to normal print

(Escape”!@“), prints INC in Superscript, then cancels Script

Mode, then prints borders.

230 Prints another line of borders, then sets Master Select with

ESCape ”!Q”, giving Double-Strike Elite.

240 Prints GENERAL ADMISSION, resets the FX to its defaults, and

prints right borders.

250 Prints the outside borders and the bottom of the inside border.

260 Prints the outside borders and sets line spacing to l/72-inch.

270 Prints the bottom of the outside border.

11

Page 29

280 Returns the printer to its defaults.

300-330 Provides data for the FX letters as user-defined characters

0-3.

350-410

Provides data for the ticket borders.

12

Page 30

Chapter 1

The FX Printers

Once you’ve unpacked your new printer, the first thing you should

do is make sure you have all of the parts. With the FX-80 or FX-100

printer, you should receive the items shown in Figure

1. The printer itself

2. A manual-feed knob

3. A paper separator

4. Two protective lids

5. One ribbon cartridge (in a box)

6. This FX Series Printer User’s Manual

The FX-80 has a tractor built into its platen for handling continuousfeed paper between 91/2 and

continuous-feed paper, you must purchase the optional FX-80 tractor

unit.

10

inches in width. To handle narrower

1-1:

On an FX-100 you will find these items installed:

7. A tractor unit

8. A dust cover for the tractor unit

As you unpack your printer, you may want to save all protective

plastic, paper, and cardboard to use in the future for repacking. Figure

1-2 displays with labels the parts of each model that we discuss in this

chapter.

13

Page 31

14

Figure 1-1. The FX-80 and FX-100 printers

Page 32

Figure 1-2. Printer parts

15

Page 33

Additional Supplies and Accessories

The following items may be purchased separately from your Epson

dealer:

Printer cable or interface kit. Each computer system has its own way

of connecting to a printer. Some computers need a cable only, others

require both a cable and board. The FX printers use the Centronics

standard parallel interface scheme described in Appendix K. If your

computer expects to communicate through a serial rather than

through a parallel interface, you must purchase a serial board for your

FX. Your Epson dealer stocks a variety of FX interface boards as well

as cables.

Printer paper. FX printers are designed to accommodate several types

and sizes of paper. Both printers include tractors so that you can use

continuous-feed paper with pin-feed holes and friction mechanisms so

that you can use paper without these holes.

Ribbon cartridge replacement. The expected life of a cartridge is three

million characters (roughly 1,000 pages of text).

Print head replacement. The expected life of a print head is one hundred million characters (over 30,000 pages of text).

Roll paper holder. For the FX-80, you may purchase an optional roll-

paper holder.

Printer Location

Naturally, your printer must sit somewhere near the computer (the

length of the cable is the limiting factor), but there are other considerations in finding a choice location for your computer/printer setup.

For instance, you may want to find an electrical outlet that is not

controlled by a switch-since a switch may be accidentally shut off

while you have valuable information stored in memory Be sure the

outlet is grounded (do not use an adapter plug). To minimize power

fluctuations, avoid using an outlet on the same circuit breaker with

large electrical machines or appliances. Finally, for continuous-feed

operations you must allow enough room for the paper to flow freely,

as in Figure 1-3.

16

Page 34

Figure 1-3. Paper path

Printer Preparation

Once you’ve found a good home for FX, you’ll need to do some

preparing before you can print. This section describes the first steps,

which include installing a few parts, checking the setting of some

internal switches, and then inserting the ribbon cartridge.

Note: The printer should be turned OFF during all set-up operations.

Paper separator

To install the paper separator, hold it vertically so that it rests on the

two slots at the back of the metal frame as shown in Figure

down gently but firmly until the separator snaps into place.

To remove the separator, pull up on the left side first, letting the

right side slide out of its slot.

1-4.

Press

17

Page 35

Figure 1-4. Paper separator

Covers

For protection from dust and foreign objects and for quiet opera-

tion, FX printers use two types of covers. When you use the friction

feed on either the FX-80 or the FX-100 or the built-in tractor on the

FX-80, use the pair of flat protective lids (Figure 1-5). When you use

the removable tractor unit, use the tractor cover (Figure

Install the center protective lid by inserting tabs into slots (one tab

per side on the FX-80, two on the

FX-100).

Fit the left side of the lid

over the friction-control lever (you may need to slightly bow the middle of the lid before you can snap the tabs into their slots). When you

need to change the setting of the pin feeder on the

tractor unit on either model, remove this lid by giving it a slight

upward tug.

Install and remove either the front protective lid or the tractor cover

by using the hinge posts at the front of the printer opening. This

arrangement allows you to easily raise and lower the cover to load

paper or ribbon. To install the cover, hold it at its full vertical position,

slide the right hinge fitting over the right hinge post, and set the left

FX-80

1-6).

or install a

18

Page 36

fitting over its post. Lower the cover. To remove the cover, move it to

its full vertical position and then lift it up and a little to the left.

Figure 1-5. Protective lids

Figure 1-6. Tractor cover

Manual-feed knob

The manual-feed knob (Figure 1-7) can aid you in loading and

adjusting paper. To install the manual-feed knob, hold it in position on

19

Page 37

the right side and twist until the flat sides of rod and fitting match.

Push the knob straight in with a steady pressure. To remove, pull

straight out.

Figure 1-7. Manual-feed knob

DIP switches

Several tiny switches, called DIP (for Dual In-line Package)

switches, are located inside the FX. They control a number of important printer functions, such as line-feed adjustment, the paper-out sen-

sor, the beeper, and the default print modes. You can check these

switches now, or you can skip to the ribbon section and check the

switches later.

The design of the FX printer allows easy access to the internal

switches. They are located under the upper-right vent. To remove the

vent, you need a Phillip’s-head screwdriver. Once the top screw is

removed, take the vent off by pressing down and sideways with the

palm of your hand (Figure

Do not replace the screw because in the course of this manual, we

will sometimes suggest that you reset switches. Keep the screw in a

safe spot so that you can replace it later.

Locate the two DIP switch assemblies as shown in Figure

check that they are set as shown in Figure

20

1-8).

1-10.

1-7

and

Page 38

Figure 1-8. DIP switch vent

21

Page 39

These switches are set at the factory, and most of them you will

never need to touch. You may, however, want to take the time now to

match up the switches with their functions, as shown in Table 1-1. For

a further discussion of the DIP switches, see Appendix E.

Figure 1-9. DIP switch location

Figure 1-10. DIP switch factory settings

Always turn the power off (with the switch on the left side of the

printer) before touching any internal switch. The printer checks most

switch settings only at power-up. If you make changes when the

power is on, they may be ignored until you turn the printer off, then

back on. So set all switches with the power off. Use a non-metallic

object, such as the back of a pen, to change the DIP switches.

One switch deserves your immediate attention; it is the switch

labelled 4 on switch assembly 2. This switch (let’s call it 2-4) adjusts the

automatic line feed (the movement of the paper up one line) at the end

of each print line to match your computer system’s needs.

22

Page 40

Table 1-1. DIP switch functions

Switch 1

Some computer interfaces automatically send a line-feed code to

the printer at the end of each print line. Other interfaces send only a

carriage return (which returns the print head to its left-most position),

and rely on the printer to perform the automatic line feed. Switch

enables the FX to match either requirement. With switch

2-4

printer automatically adds a line feed to every carriage return it

receives from the computer; with the switch off, it expects the computer to provide the line feed. If you are not sure what your system

requires, leave the switch the way you find it, but remember that you

can adjust this if your first printing occurs either all on one line or with

the lines spaces twice as far apart as you requested.

2-4

on, the

We recommend two changes now. Turning switch 1-2 on adds a

slash to the zero character, which makes program listings easier to

read. If you are not going to create your own characters, turn switch

1-4

on to take advantage of the internal

2K

buffer.

Ribbon installation

First, be sure the printer is turned off and move the print head to the

middle of the platen.

Remove the ribbon cartridge from its packing materials. Holding

the cartridge by the plastic fin on the top, guide the pair of tabs at each

23

Page 41

end of the cartridge into the corresponding slots in the printer frame

(Figure 1-11). The cartridge should snap neatly into place.

With the paper bail resting on the platen, you can tuck the ribbon

between the metal ribbon guide and the black print head.

As Figure 1-11 suggests, you can ease the ribbon into place with the

deft application of a dull pencil. To remove any slack in the ribbon,

turn the ribbon knob in the direction of the arrow.

Note: When you replace a ribbon, remember that the print head may

be hot from usage; be careful.

Paper Loading

How you load your paper depends on which model of FX you have

and which type of paper and feeder you are using. This section covers

each type of paper loading and then illustrates the top-of-form position on both models.

Both the FX-80 and the FX-100 include tractors so that you can use

continuous-feed paper with pin-feed holes and friction mechanisms so

that you can use paper without these holes.

Continuous-feed paper usually comes fanfolded into a box and has

pin-feed holes arranged on half-inch tear-off strips at each side. This

allows the printer’s pin feeders to engage the paper and pull it evenly

through the printer. After printing you can remove the tear-off strips

and separate the pages.

The FX-80’s built-in tractor handles continuous-feed paper that is

9½ inches wide, which is the standard 8½-inch width with the tearoff strips removed. The FX printers’ removable tractor units (optional

on the FX-80, standard on the FX-100) handle continuous paper in

widths from 4 inches to the width of the platen - 10 inches on the

FX-80,16 inches on the FX-100. The friction feeder on each FX handles

all papers narrower than the width of the platen.

To refresh your memory about names of the parts, refer back to

Figure 1-2.

FX-80: built-in tractor feed

The FX-80’s built-in tractor will accommodate 9½- to 10-inch wide

continuous-feed paper with pin-feed holes. You should have few problems loading it if you follow these instructions carefully.

24

Page 42

Figure 1-11. Ribbon insertion

25

Page 43

Figure 1-12. Printer readied for paper insertion

l

Be sure the printer is turned off. Lift the front protective lid and

move the print head to the middle of the platen.

l

Remove the center protective lid.

l

Pull the paper bail and the friction-control lever toward the front of

the printer. Your printer should now look like Figure 1-12.

l

Adjust the pin-feed levers to approximate the width of paper you

are using. Pull the levers forward to release the pin feeders, move

them so their arrows line up with the correct position on the scale

(e.g., for 9.5 for 9½ -inch paper), and push the levers backward to

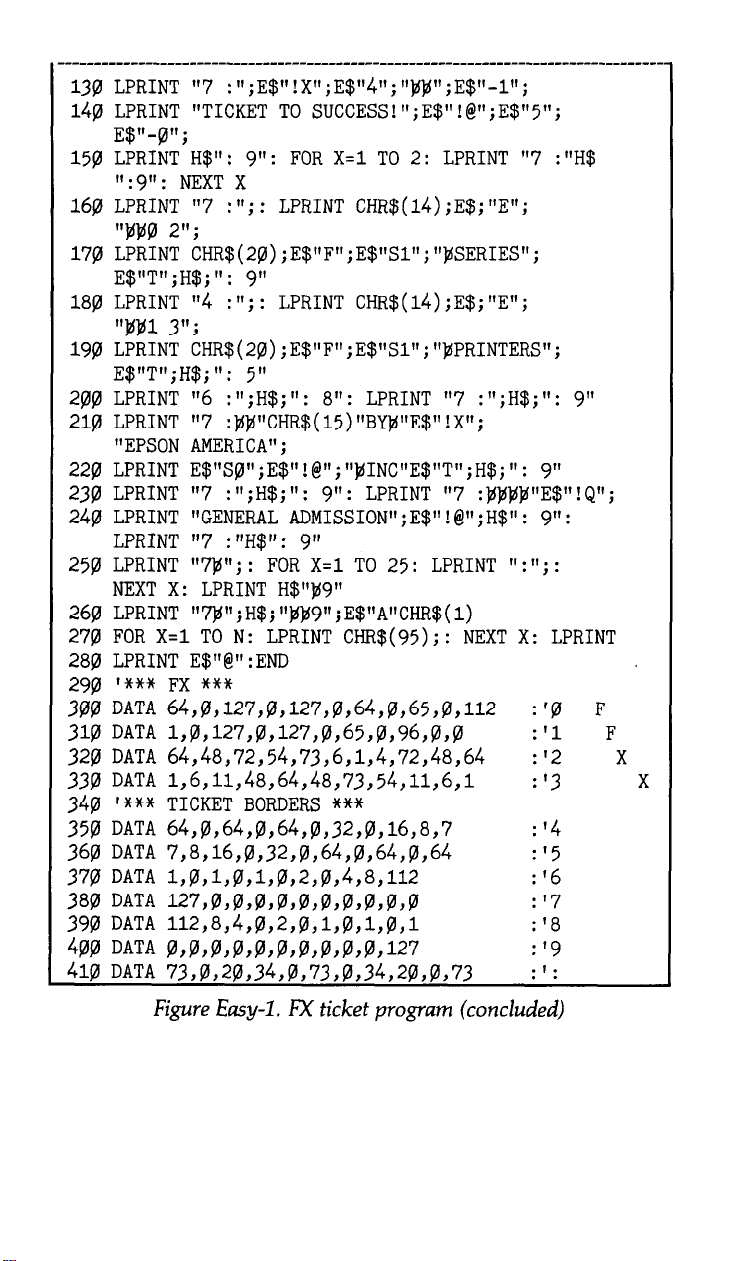

lock them into position (Figure 1- 13).

If you are using fanfold paper, start by positioning your paper

directly beneath or behind the printer, as in Figure 1-14, so that the

paper won’t kink or pull to one side.

l

Insert the paper under the plastic separator, guiding it with your left

hand while you slowly roll the manual-feed knob clockwise. It is

26

Page 44

Figure 1-13. Pin feeder adjustment

very important to keep the paper straight so that the pins on both

sides engage at the same time. If the paper does not move smoothly,

remove it by reversing the manual-feed knob and start again with an

unwrinkled sheet.

Figure 1-14. Loading the FX-80

27

Page 45

l

As the paper comes up the front of the platen, watch to be sure that

it is feeding under the black edges of the pin feeders. If your paper is

wrinkling as it comes through, you may need to readjust the pin

feeders.

l

Reinstall the center protective lid underneath the paper. Push the

paper bail back against the paper and close the front protective lid.

You are now ready to set the top of form, as shown at the end of this

section.

l The friction-control should remain toward the front of the

printer as long as the tractor is used.

FX-80 and FX-100: friction feed

The friction feed is for paper without pin-feed holes.

Before using the friction feed on the FX-80, disengage the pin feeders

by pulling the levers forward, then move the feeders as far toward the

edges as possible. Remove the center protective lid if it is on.

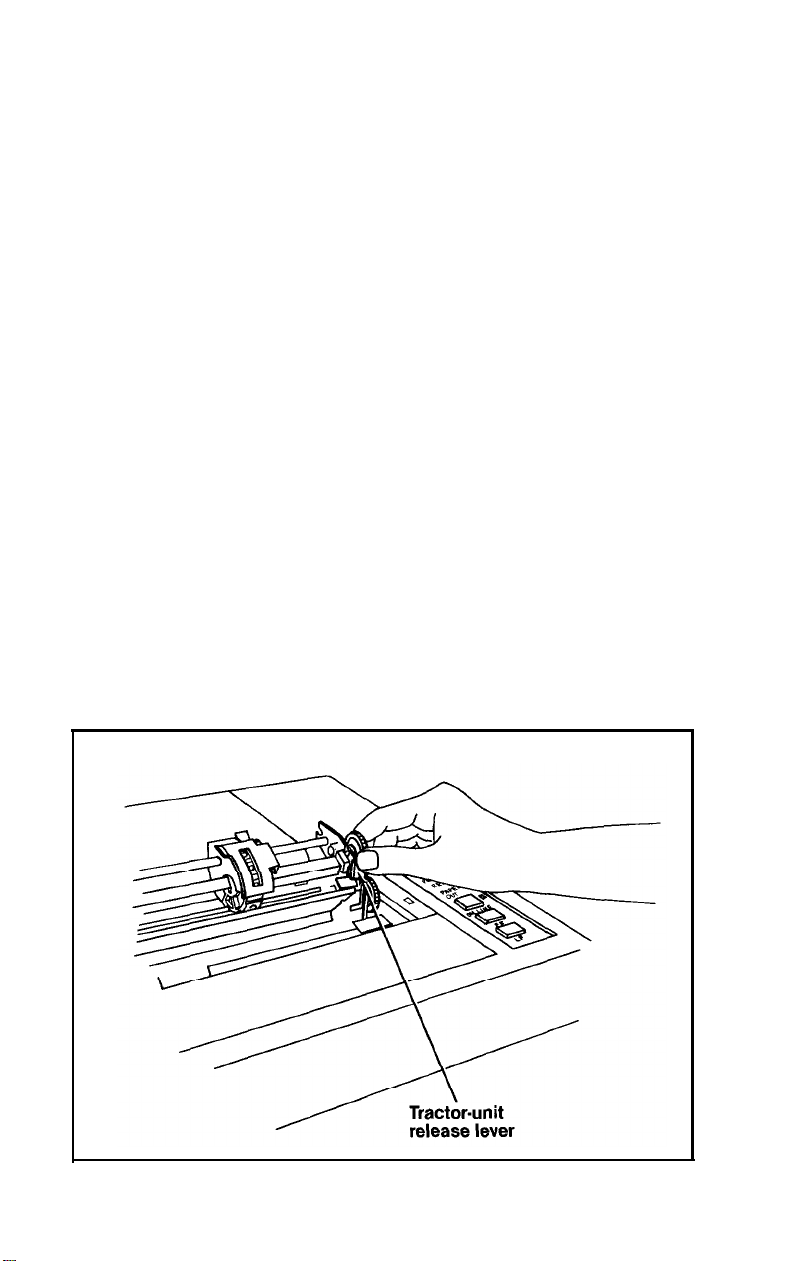

If a tractor unit is installed on the top, remove it. Push both tractor-

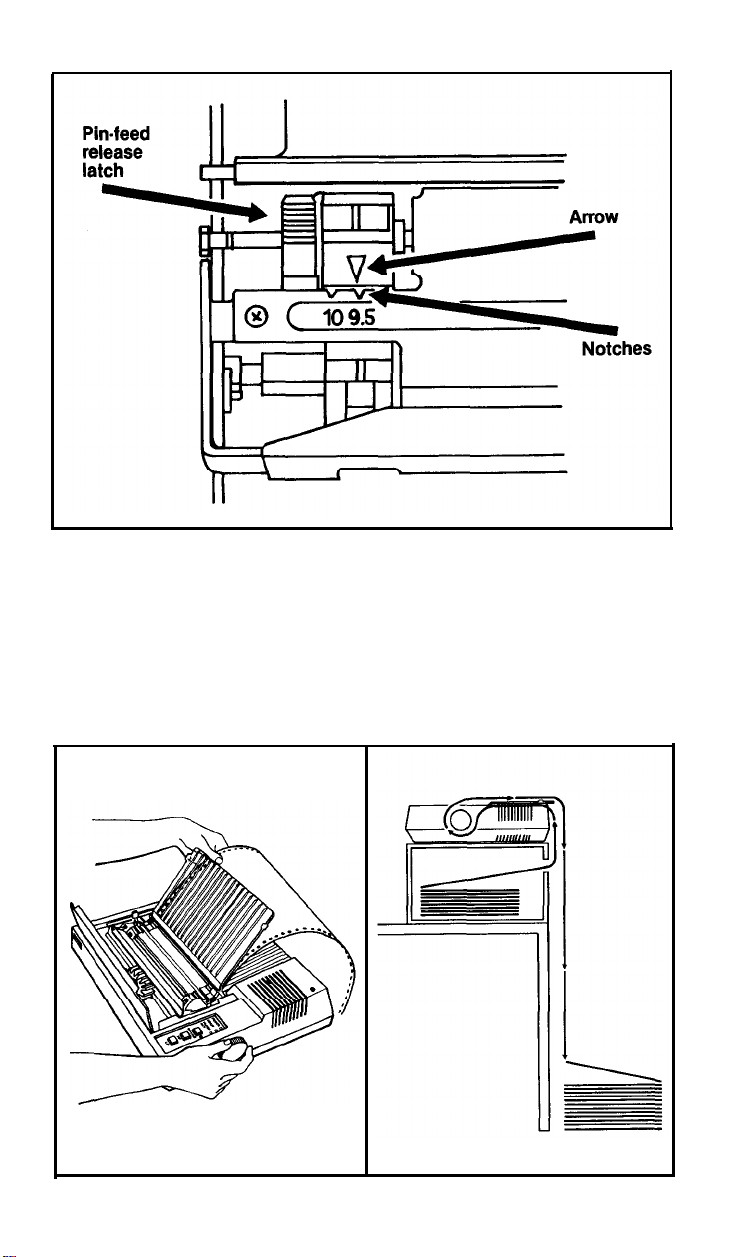

unit release levers back (one is shown close up in Figure

the unit up and back, pulling it gently toward the rear of the printer.

The tractor will come off easily-you should not have to tug on the

unit to remove it.

1-15).

Rock

28

Figure 1-15. Tractor unit release

Page 46

Now follow these steps to load your paper into the friction feeder:

l

Be sure the printer is turned off, Lift the front protective lid and

move the print head to the middle of the platen (refer back to Figure

1-12). Pull the paper bail up.

l

Engage the friction-control mechanism by pushing the friction-

control lever to the back.

l

Guide the paper under the paper separator and the platen with your

left hand, while turning the manual-feed knob with your right

hand.

If you hear a crinkling noise, stop. This can result from the paper

getting slightly wrinkled; it is best to remove the paper and start

over with an unwrinkled sheet.

l

Do not pull on the paper as it comes up from the platen; leave the

friction feeder in charge. Push the paper bail back against the paper,

close the front protective lid and reinstall the center protective lid.

You are now ready to set the top of form, as shown at the end of this

section.

There is one more point to consider if you are printing on single

sheets of paper. DIP switch 1-3 is set to active at the factory, and this

means that the paper-out feature will sound the FX’s beeper and halt

printing whenever it senses the bottom of your sheet of paper. In prac-

tice, this means that without deactivating the sensor, you won’t be

able to print on the bottom of a single sheet of paper. You can, usually,

deactivate the paper-out sensor easily by changing switch 1-3. Some

computer systems, however, ignore the setting of DIP switch 1-3 (See

Appendix F.)

FX-80 and FX-100: removable tractor unit

(optional on the FX-80)

The removable tractor will accommodate pin-feed paper in any

width from four inches to the width of the platen.

To install the optional tractor unit on the FX-80, begin by removing

the center protective lid if it is on. Move the built-in pin feeders as far

as possible to the right.

To add the tractor unit to either the FX-80 or the FX-100, hold the

tractor unit over the printer with the gears to your right as shown in

Figure 1-16. Lower the rear hooks over the rear studs as shown in

Figure 1-17, pushing the unit back against the studs to ensure that both

29

Page 47

sides of the tractor assembly are firmly in place. Rock the front of the

unit downward, pressing firmly until it locks into place.

Figure 1-16. Tractor unit installation

30

Figure 1-17. Hook and stud

Page 48

To load the paper into the unit, use this procedure:

l

Be sure the printer is turned off; then open the front protective lid to

move the print head to the middle of the platen.

l

Pull the paper bail and the friction-control lever toward the front of

the printer (refer back to Figure

l

Insert the paper under the paper separator and the platen and push

1-12).

the paper through to the front.

l

Position the pin feeders, using the pin-feed locking levers to make

the adjustment. One is shown in Figure

l

Raise the black covers of both pin feeders and ease the paper over

1-18.

the pins. Adjust the paper or pin feeders as necessary so that there

are no wrinkles or dips in the paper. Now you are ready to set the

top of form.

Figure

1-18.

Adjusting the pin feeders

31

Page 49

Top-of-form position

After you have loaded the paper, you should set it to the top of

form, which is the position of the print head when you turn the printer

on. (Since the computer term form corresponds to the word page, it

may be easier for you to think of this as the top of the page.) To make

this setting, advance the paper until a perforation lies slightly below

the top of the ribbon.

The relationship between the perforation and the printhead is the

same on both models of the printer, as you can see in Figure 1-19. You

need to leave some paper above the ribbon so that the paper moves up

smoothly.

When you have the position set, lower the bail and replace or repo-

sition the lids or cover.

Although you have arranged the paper correctly, you are not done.

The printer will not recognize the top of form until the next time you

turn it on. The FX considers a form to be 66 lines long unless you

change this length as discussed in Chapter 8.

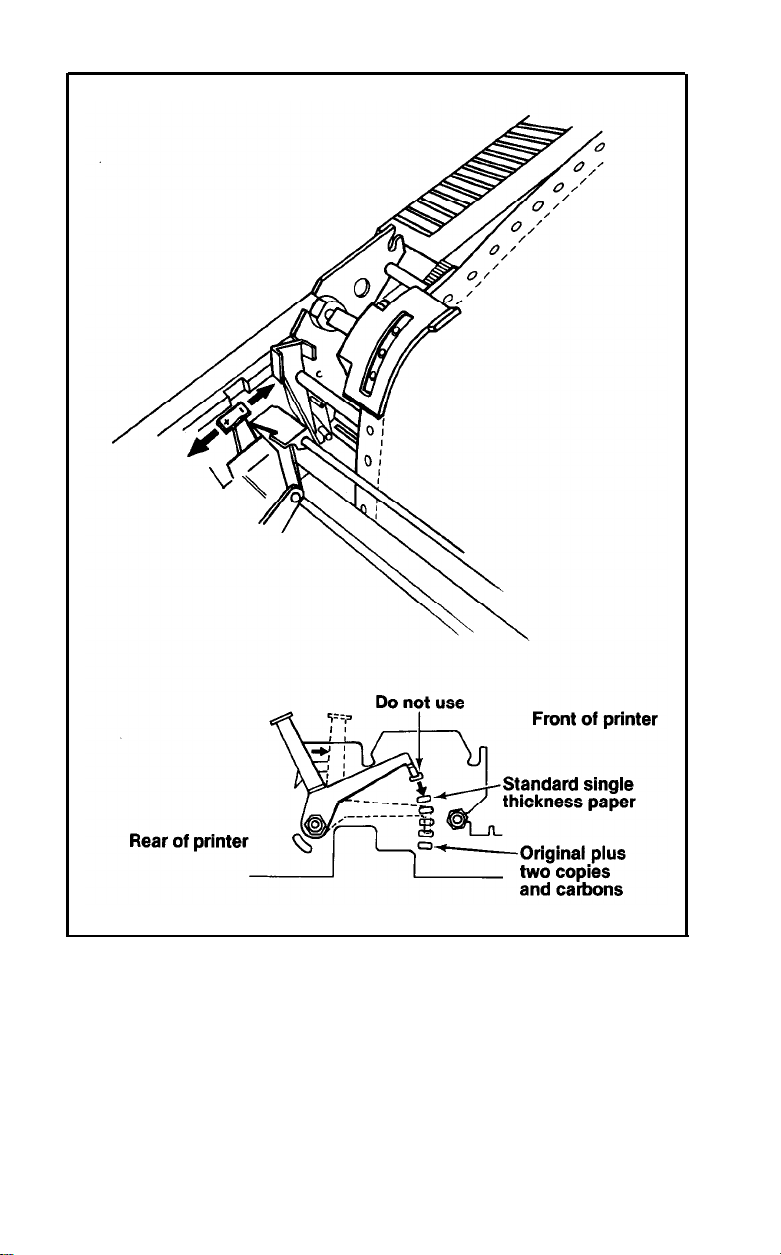

Paper-thickness lever

The paper-thickness lever shown in Figure 1-20 moves the print

head to accommodate various paper thicknesses. The factory sets it

for ordinary paper (which is 1/5OOth of an inch thick), but you can

adjust it for printing one original and up to two copies. For thick paper

or multiple copies, move it toward the front. Do not use the extreme

rear setting, however. This position is used for head alignment and

will shorten the life of the print head if used in normal operation.

starting up

It is finally time to connect the printer to the computer; remember

that some computers need interface kits and all need cables. First make

sure the power switch is off. Connect the printer end of the printer

cable to the connector at the right rear of the FX (as shown in Figure

32

Page 50

Figure 1-19. Top of form

1-21). The other end of the cable plugs into your computer. If your

cable includes grounding wires, be sure to fasten the wires to the

grounding screws at each end.

With the paper loaded, turn the printer on with the toggle switch at

the left-rear comer of the FX. You get a little dance from the print head

and three lights go on: the POWER light, the READY light, and the

ON LINE light. If the ON LINE and READY lights are not on, push

the button marked ON LINE. If the PAPER OUT light is on, the paper

is not loaded correctly.

33

Page 51

34

Figure

1-20.

Paper thickness adjustment

Page 52

Figure 1-21. Cable connection

Control panel

When the control panel’s ON LINE light is on, the printer and computer are in direct communication and the FF (form feed) and LF (line

feed) buttons have no effect. Go ahead, try pushing one.

To use the FF and LF button; press the ON LINE button to turn it

off. Now you can see what the other buttons do.

Press the LF button briefly, then release it. That produces one line

feed. Now hold the LF button down for a moment to produce several

line feeds.

The FF button advances the paper one complete page(form). If you

hold the button down, it advances several forms. Ideally, you’ll set the

top-of-form position before you turn on the printer. That way, your

printing can start on the first line of the paper. If you turn the printer

on while the print head is sitting in the middle of a form, that is precisely where the next form will start when you press the FF button or

your program sends the FX a form feed.

Remember that the ON LINE light has to be off for the FF and LF

buttons to work.

The FX tests itself

Now it’s time to see how your new FX operates. If you’re using an

FX-100, be sure you have full-width (15-inch printing area) paper

35

Page 53

loaded because the printer’s test uses all 136 columns. Turn the printer

completely off (with the switch on the left side of the printer), press

down the LF button, and turn the printer back on again while still

holding down the LF button.

Figure 1-22. Sample automatic test

Figure 1-22 shows the FX’s automatic test, which prints the standard

characters that are stored in the printer. The test pattern continues

until you turn the printer off. If you let it run long enough, you’ll see

two sets (Roman and Italic) of upper- and lower-case letters, plus

many other characters.

If you plan to use your FX printer primarily for word processing or

with some other commercial software, you are now ready to follow

the printer set-up instructions in your software menu or manual.

Because most software packages include set-up routines for dot matrix

printers, this set up may be merely a matter of specifying which

printer you are using.

In case your software asks for specifications that you do not understand, check the appendixes or consult your computer dealer.

Some programs allow you to insert codes to activate such FX features as Emphasized and Compressed printing. Your software manual

will tell you how to use this feature, and the Quick Reference Card in

Volume 2 will give you the necessary ESCape and control codes.

36

Page 54

Chapter 2

BASIC and the Printer

While you read this manual, you’ll be testing your FX with programs in the BASIC language. You can, of course, use another language with your printer; see Appendixes A through D for the ASCII

and ESCape codes that your software manual will explain how to use.

Here we use BASIC because it is the most popular language for personal computers.

One of the simplest things you can do with any FX printer is print

listings of your BASIC programs. You merely load a BASIC program

into the computer and send the LISTing output to the printer instead

of to the screen.

Unfortunately, different computer systems access the printer in

different ways. For example, most computers that use Microsoft

BASIC send PRINT or LIST commands to the printer by adding a

leading L to a screen command: LPRINT, LLIST, etc. Some other computer systems use PRINT# in place of LPRINT Another group uses

PR#l to route information to the printer and PR#O to restore the flow

of information to the screen. If you aren’t familiar with your system’s

command conventions, consult its manual.

We will use the LPRINT and LLIST commands for our examples in

this manual because the widespread acceptance of Microsoft BASIC

makes these commands as close to a standard as exists in this industry.

But remember that you may need to modify such commands to match

the unique aspects of your system. The Preface and Appendix F can

help.

Once you have discovered how your computer communicates with

the printer, load a BASIC program into memory. Now list it onto the

printer, using your computer’s version of the LLIST command. Some

examples are shown in Table

2-1.

37

Page 55

Table

2-1.

If your listing is more than a page long (or if you didn’t start the

listing at the top of a page), your printer may have printed right over

the perforation. Set DIP switch 2-3 to the on position, and the printer

will automatically skip over the perforation. We discuss this further in

Chapter 8.

Meanwhile, printing a program LISTing is a fundamental function

of the printer. Be sure you manage this before continuing (if you have

trouble, consult your computer’s manual for help).

Several computers’ print LIST commands

BASIC Communications

Part of the difficulty in controlling communications between computer and printer is the lack of a completely standard coding scheme.

When your computer sends out a numeric code for the letter A, you

naturally want your printer to interpret that code as an A. Most manufacturers of computers, printers, and software use the American

Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII, pronounced ask-

ee) to code such frequently used characters as the letters of the alphabet, numerals, and keyboard symbols. Of the 256 ASCII numbers,

most are codes for specific characters; some are codes for such computer or printer functions as sounding a beep or performing a carriage

return.

The ASCII standard does not yet allow for the advanced features in

today’s computers and printers. Individual manufacturers therefore

adjust the codes to suit their own needs, which means that we are

often faced with compatibility problems between printers and computers. (To compare your computer’s version of the ASCII table with

the FX’s version, see your computer manual and this manual’s Appendix A.) You can usually overcome the code inconsistencies by sending

control codes for advanced printer functions in care of a special ASCII

code that is called an ESCape code. The next five subsections discuss

these matters in more detail.

38

Page 56

Character strings

The character-string (or CHR$) function converts any decimal

number from zero through 255 to a character or action. Its format is

CHR$ followed by a number in parentheses, for example, CHR$(84).

The character-string command follows a PRINT or LPRINT command and causes your computer system to send an ASCII code to the

computer’s screen or to the printer. What gets printed or performed is

determined by the particular modified ASCII table that is used by

your system. Where the printing or action happens-on your screen

or your printer-depends on the print command that precedes the

character-string command.

For a fast check on what your computer does with this function, try

printing a few characters on your computer’s screen. The usual format

for this is PRINT CHR$(n). The n represents one of the numbers from

zero to 255, each one of which accesses a unique character or action.

Try typing this:

10 PRINT CHR$(65)

and RUNning it. Since most computers use the numbers from 32 to

127 to mean the ASCII set of characters, you should see a capital A on

the screen.

It’s the numbers less than 32 and greater than 127 that produce

different results on nearly every brand of computer. Try entering:

10 PRINT CHR$(193)

and RUNning it. If you don’t see anything on the screen, don’t worry.

Remember that this was just a quick check. We are mainly interested

in sending that 193 to the printer, and what it prints on the screen is

not as important right now.

BASIC print commands

Well then, what happens when you send such a non-standard code

as 193 to the printer? To test this out, you need to know what program

commands your computer uses to activate the printer. Some typical

command sequences are shown in Table 2-2.

39

Page 57

Table 2-2. Several computers’ printer

activating commands

Check your computer’s reference manual and type in the com-

mands appropriate to your computer. Then type RUN.

With any luck, you will get an Italic capital A on the printer:

If nothing prints, it’s time to double-check your computer manual

and cable connections. Make sure the printer is ON LINE and the

READY light is lit.

ASCII and BASIC basics

If you end up with a Roman A:

40

A

Page 58

instead of an Italic A, pay close attention to the next three paragraphs.

The original ASCII code was designed to use the decimal numbers

zero through 127. Computer systems designers soon decided to extend

this range (to 0 through

255)

in order to make room for more features.

Unfortunately, some designers did not anticipate that printers would

make use of this extended range. So they designed BASIC printer

drivers that intercept any number in the upper half of the range

255)

and automatically convert it to the lower half of the range by

subtracting

128.

(128 -

In these systems such a code as CHR$(193) never makes it to the

printer. The printer driver subtracts

128,

which means that the code

for Italic A gets to the printer as a CHR$(65). The printer then

produces a Roman A.

For many applications, you won’t need the upper half of the ASCII

codes. For others, the inability to generate codes greater than 127 will

be an obstacle. Whenever we can, we suggest ways to get around this

obstacle. In Chapter 5, for instance, we discuss Italic Mode, which is

the FX designers’ method of making Italic characters easily accessible

to all users.

If you’re patting yourself on the back because your printer printed

an Italic A, postpone your celebration for a bit. Nearly all computers’

BASIC programs intercept codes on their way to the printer and alter

some of them. For example, some popular systems intercept a