Page 1

1

March/April 2007~CoastalContractor

I

In the Ocean State — where wind-swept

rains aren’t restricted to nor’easters, tropical storms, and hurricanes — I count on

a vented rain screen coupled with carefully detailed flashings to keep water out

of walls.

A rain screen is a cladding system with

a vent space (or a series of vent channels)

between the back side of the cladding and

the weather-resistive barrier. Openings

along the top and bottom of the vent

space let air flow freely. This vent space

provides a channel for any water that gets

past the cladding surface to drain out, and

the air flowing through this space carries

away moisture vapor that dries off the

back side of the siding. In both instances,

the vent space reduces the chance of

water and moisture vapor being driven

into the wall cavity by wind or sunshine.

Installing any cladding as a vented rain

screen is the best way to make the

cladding last. However, it’s easier to do

with lap sidings than with shingles. Lap

siding, such as cedar clapboard and fibercement planks, easily bridges air channels

between vertical furring strips nailed over

studs. But a vented rain screen with sidewall shingles requires horizontal furring,

which presents some complications.

RAIN-SCREEN OPTIONS

I’ve built cedar-shingle rain-screen sidings

in three ways. The differences mostly

involve the material that forms the vent

space, but this inevitably affects other

details as well.

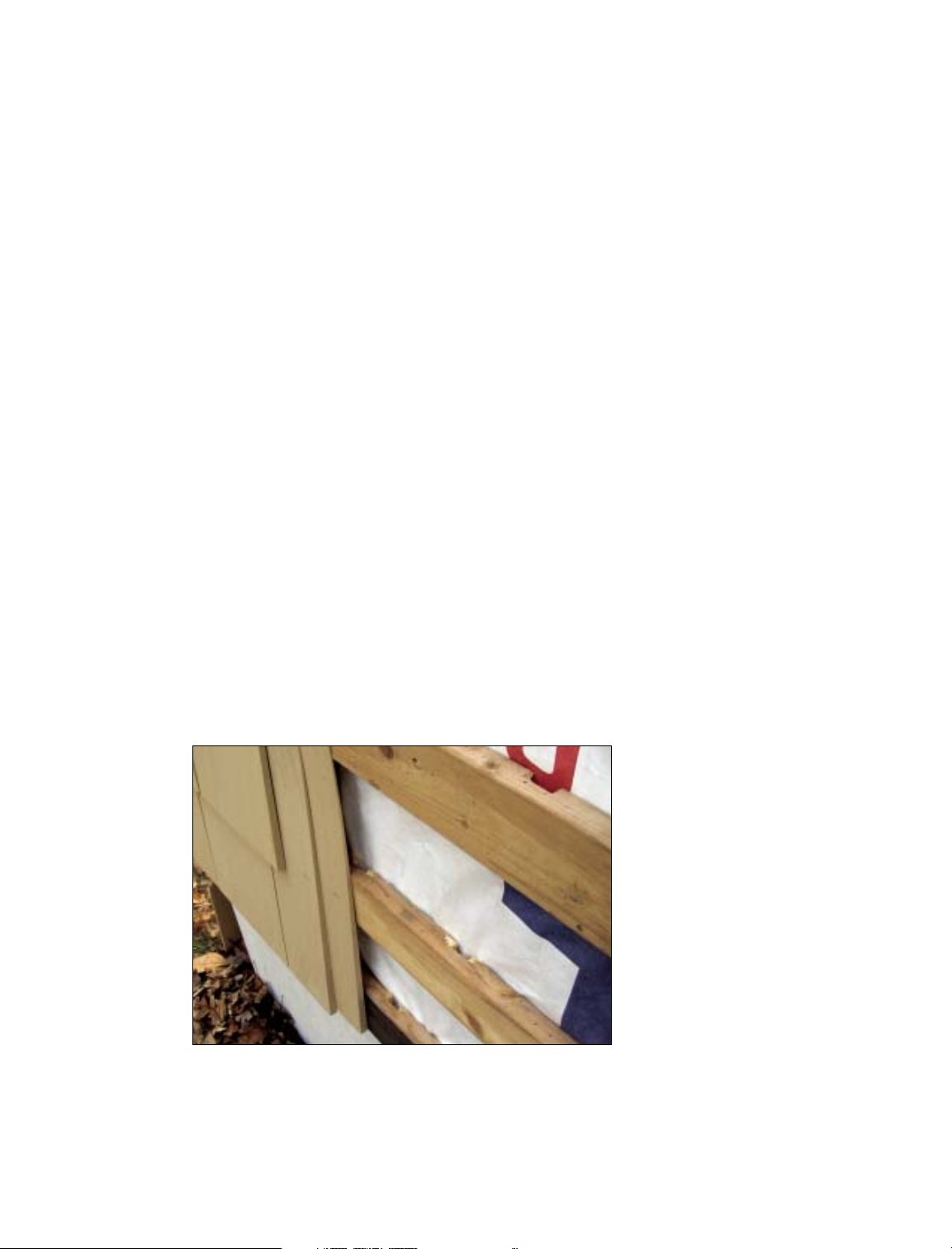

Vented furring strips. The first time I

built a cedar-shingle vented rain screen, I

laid shingles over a series of back-kerfed

1x3 furring strips (Figure 1). These back

by Mike Guertin

Best-Practice

Wall Shingles

A rain screen offers the ultimate defense against

water intrusion, provided you get the details right

FIGURE 1. The author’s first experiences with venting shingles relied on

back-kerfed 1x3 furring strips. These back kerfs are essential for allowing

water to drain out and air to flow between the horizontal strips, but cutting

the kerfs with a dado blade in a radial arm saw proved too labor intensive.

Page 2

2

kerfs are essential for allowing drainage

and airflow between the horizontal strips,

but they take a considerable amount of

cutting and time: I mounted a dado blade

in a radial arm saw and cut

3

/8- by 3/8inch kerfs a few inches apart along what

seemed like thousands of 12-footers. I

then nailed the furring strips over the

housewrapped wall sheathing, positioning

each strip above every butt line on each

course of shingles. The shingles went up

fine, but I didn’t plan my window, door,

and corner trim details very well. Shingle

butts stood proud of some trim elements,

and I cobbled together less-than-perfect

solutions to mask other problems caused

by the

3

/4-inch furring thickness.

Fortunately, there are now a couple of

commercial products available for creat-

ing vented rain screens with shingles. I’ve

used both nylon spacer mats and plastic

battens over the past few years and found

advantages and disadvantages with each. I

also worked out details for windows,

doors, and trim for these rain-screen systems, as described below.

Spacer mat. Home Slicker by

Benjamin Obdyke is the best-known

spacer mat available. It’s marketed specifically for use with sidewall shingles and

lap siding, though other companies make

similar products for EIFS and masonry

walls that will also work with shingles

(see “Resources,” page 28). Home Slicker

is a corrugated matrix of nylon strands

about

3

/8 inch thick that comes in approximately 40-inch-wide rolls. It gets applied

with staples or cap nails over house-

March/April 2007~CoastalContractor

A spacer mat such as Home

Slicker goes up quickly with no

special layout, creating a

1

/4-inch

ventilation gap behind shingles.

It is important to cut Home

Slicker close to trim such as window casing and corner boards: If

you leave a space wider than

about

3

/4 inch, the unsupported

shingle edge is likely to split.

Page 3

3

wrapped walls, and the matrix compresses

a little when the shingles are installed on

top, leaving an effective

1

/4-inch air

space. The corrugations should be oriented vertically for the best drainage and

airflow, and the edges of the mat should

not be overlapped.

On the plus side, Home Slicker is only

1

/4 inch thick — not nearly the 3/4 inch my

furring strips padded out the shingles. The

butt lines of each shingle course laid over

Home Slicker flush out with

5

/4-inch corner boards applied directly over the housewrap. And the butt lines come close to, but

not past, most flanged window jambs. The

sheets go up quickly with no special layout, but it is important to cut Home

Slicker close to trim such as window casing and corner boards. If you leave a wide

space (

3

/4 inch or more), the unsupported

shingle edge is likely to split.

On the downside, fastening shingles

over Home Slicker takes a deft hand.

The bottom few shingle courses are the

hardest to install. The matrix is spongy, so

hand-driving nails is a challenge, and

pneumatically driven staples or nails easily overdrive even with the air pressure set

low. You’ll end up splitting more shingles

in the first two rows than on the rest of

the wall. Subsequent courses are supported by the shingles beneath, so the

going gets a little easier. There’s a noticeable cushioning of hammer blows when

hand-driving nails into shingles applied

over Home Slicker. The bounce makes it

hard to start nails in the shingles. You

must also use fasteners long enough to

pass through the vent space and penetrate all the way through the sheathing.

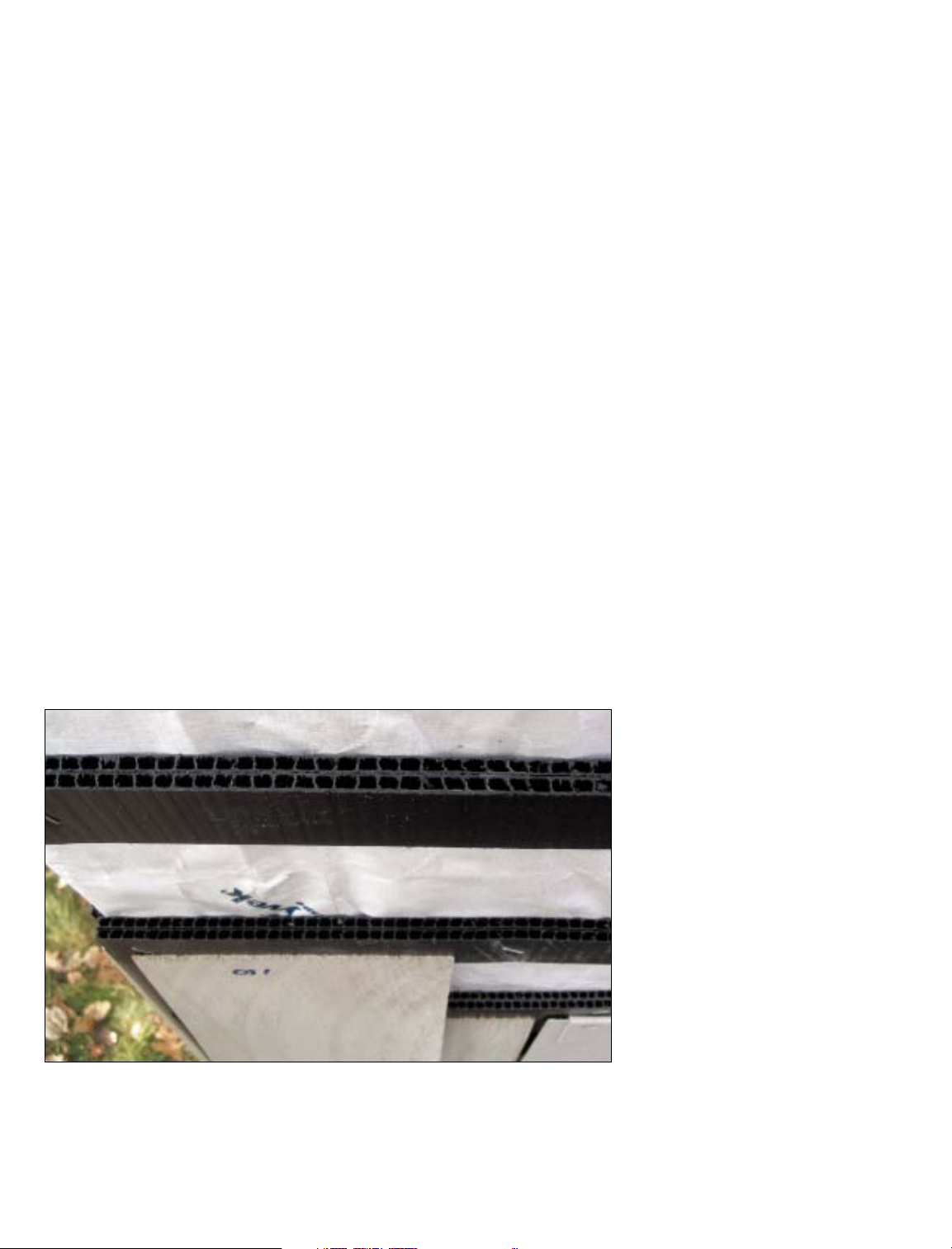

Plastic battens. Corrugated plastic

battens offer a good alternative to my furring-strip rain screen. These have hollow

channels that let water and air flow

through them (Figure 2).

The only ones I’ve found marketed

specifically for shingle installation are those

from DCI Products — CedarVent and

RafterVent — but similar products are

available (see “Resources,” page 7).

Standard CedarVent comes in strips 3 feet

long. The four-ply version is

3

/4 inch thick

by 2

3

/4 inches wide. But a two-ply version

that’s just

3

/8 inch thick (my preference)

and a three-ply version that’s

9

/16 inch thick

are also available. While 1

1

/2-inch-wide

strips can be special ordered, I typically just

rip the two-ply version in half (from 2

3

/4

inches down to 13/8 inches) to save material and expose more of the shingle back to

the air. CedarVent is wrapped with a thin

fabric to keep insects out, so it’s great along

the undercourse at the bottom of the wall

and last course at the top. RafterVent can

be used instead of CedarVent in the field of

the wall. It’s essentially CedarVent without

the fabric wrap.

Battens require precise placement, so

they aren’t as fast to install as spacer

mats, but they do provide solid support for

nailing. I lay out a story pole for shingle

course exposure and use it to mark locations for the battens. After I transfer these

layout marks onto window and door trim

and corner boards, I snap chalk lines on

the housewrap between my marks. The

battens get applied above the lines. Since

shingles are nailed about 1 inch above the

butt line of the overlapping course, the

battens are positioned perfectly behind

the nail line. Extra battens are needed

under windowsills and horizontal bandboard trim elements to support the top

edges of the shingles.

Other than selecting longer fasteners,

there’s no special precaution to applying

shingles over battens.

TRIM DETAILS

The devil is always in the details. Corner

boards, woven corners, window and door

trim, band boards, and other trim elements

Best-Practice

Wall Shingles

March/April 2007~CoastalContractor

FIGURE 2. Plastic battens have hollow channels that let water and air flow through them.

Shown here is the two-ply version of CedarVent, which the author rips to 13/8 inches wide

to save material and expose more of the shingle back to air.

Page 4

4

Best-Practice

Wall Shingles

March/April 2007~CoastalContractor

must be planned to account for the extra

thickness of the rain-screen “sandwich.”

I address some of the challenges this

presents here, but this is by no means an

exhaustive list. It will, however, give you

a foundation to come up with your own

solutions for those yet-to-be-encountered

trouble spots.

Pests and nests. Wasps and hornets

love to make nests in rain-screen spaces,

so along the bottom (intake) vent slot and

the top (exhaust) vent slot you need to

block bug entry. Simple strips of insect

screen wrapped around the edge of spacer

mat or battens are all you need. Slicker

Screen is a companion to Home Slicker,

and DCI’s CedarVent already has an

insect-blocking fabric covering. When

I’m not using those products, I staple

3- or 4-inch-wide screen to the bottom

edge of the wall before installing battens

or spacer mat (Figure 3). After the vent

material is applied, I wrap the screen

onto the face and staple it in place.

Once the trim or shingles are applied,

the screen is trapped securely.

Weaving shingle corners. Hand-weaving outside and inside corners over Home

Slicker is a challenge. The shingles drift a

little when planning, because the fastener

shanks flex in the air space and the sponginess of the matrix makes it hard to keep

the shingles from moving around. Rather

than get frustrated, I avoid the issue by

wrapping outside and inside building corners with 6-inch strips of

1

/4-inch plywood.

The plywood gives solid support for fastening and provides crisp lines to plane the

shingle edges to. For extra weather resistance, I staple 16- to 24-inch-wide strips

of housewrap or building paper over these

plywood backing strips, letting it lap over

the edges of the Home Slicker.

Plastic battens don’t pose the same

trouble because they’re more stable. I run

the battens around the corner and weave

the corners like normal. The only tricky

FIGURE 3. Wasps and

hornets love to build

their nests in the vent

space of any rain

screen, so exposed

edges (at the bottom

and top of walls and

over windows and

doors) must be protected with screening.

Fastener selection: Use hot-dip galvanized, stainless steel, or

aluminum — not electrogalvanized — fasteners, especially in

coastal areas. I prefer stainless staples or nails for the best

performance, and they eliminate the chances of streaking.

Staples (16 gauge with

7

/16-inch to 1/2-inch crown) and

nails (box type with blunt points) are both acceptable. The

fastener must penetrate through the shingles, vent space,

and all the way through the sheathing.

Fastener location: Place two fasteners per shingle about 1

inch above the overlying course line and

3

/4 inch in from each

edge. If the shingles are wider than 10 inches (Cedar Shake

& Shingle Bureau) or 8 inches (IRC), apply an additional pair

of fasteners spaced 1 inch apart near the middle of the shingle. Orient the pair of fasteners so the 1-inch space between

them is not within 1

1

/2 inches of a shingle joint below.

Keyway spacing: When shingles are wet or green when

applied to the wall, it’s okay to butt the shingles edges

together. Dry shingles must be spaced apart to prevent

buckling when they absorb moisture and swell. As a rule of

thumb, I space shingles up to 6 inches wide with a

1

/8-inch

keyway. I space shingles that are between 6 and 9 inches

wide

3

/16 inch apart. I space shingles wider than 9 inches

1

/4 inch apart.

Joint offset: Joints in successive shingle courses must be

offset by a minimum of 11/2 inches (IRC and CSSB).

Keep in mind that if there are any defects in the top lap

of a shingle, you should space joints 1

1

/2 inches away

from the defect.

— M.G.

SHINGLE SPECS

Page 5

5

part is starting the first two courses at the

bottom; but once they are secured, the

rest of the corner shingles go fine.

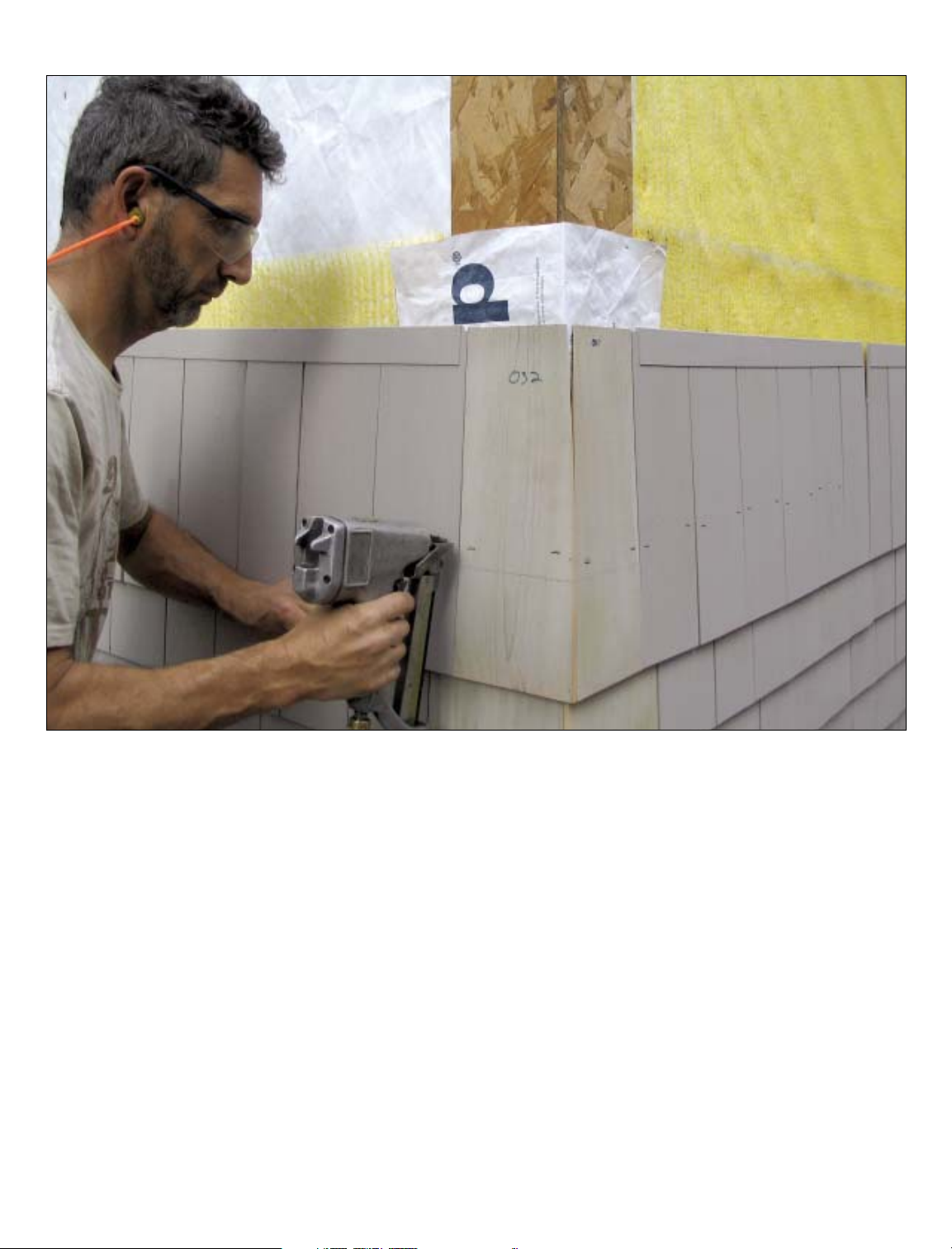

Corner boards. Ideally, corner boards

and other trim elements should be

applied over the rain-screen space. They

benefit from the drainage and “back-venting” just like the shingles. Plus, installing

the trim over the vent material keeps it in

the same plane as the shingles. However,

this is practical only over battens. Over

the less stable spacer mats, the corner

boards are hard to line up.

One way to deal with this is to apply

1

/4-inch plywood or OSB spacers to the

building corner, which provides solid nailing and a vent space (Figure 4). I use

4-inch-wide plywood or OSB spacers positioned 12 to 24 inches apart up both sides

of each building corner. I cut the block

width

1

/2 inch greater than the cornerboard width and snap vertical plumb chalk

lines over the blocks that give me a reference for aligning the corner boards. These

spacer blocks are easier to install before

the matrix mat is installed. There’s no

need to cut the mats around the blocks

either — just trim at the outside edge.

Horizontal band boards or skirt

boards present a similar challenge. I treat

them the same as corner boards. With bat-

tens, I run one strip at the bottom and

one at the top, which is placed so half the

batten supports the top edge of the board

and the other half is exposed to support

the first course of shingles. When using

Best-Practice

Wall Shingles

March/April 2007~CoastalContractor

FIGURE 4. Corner boards should be

applied over a rain screen just

like the siding. While this is relatively easy with battens, installing

trim over a spacer mat is more

difficult because the pliable mat

doesn’t provide a stable nailing

base. To make it easier, the

author installs 1/4-inch OSB spacers to the building corner before

the matrix mat is installed.

FIGURE 5. Skirt boards over

a spacer mat also get 1/4inch plywood or OSB

blocks (far left), while battens are simply spaced so

half the batten is above

the top edge of the skirt

board (left). In both cases,

a drip cap flashing must

be installed over the horizontal trim board, but this

flashing should not extend

to the sheathing so it will

not disrupt airflow.

Corner-Board Detail

1

Spaced

OSB or plywood blocks

End rain-screen mat

at chalk line here

/4" to 3/8"

Rain-screen

mat

Corner board

Apply housewrap

on wall first

Midwall

band board

Skirt board

Spaced

1

/4" to 3/8" OSB

or plywood blocks

Screen under blocks

protects against insects

Z flashing

Midwall

band board

Housewrap

Rain-screen mat

Skirt board

DCI CedarVent includes

insect-blocking fabric

Z flashing

Plastic

battens

Page 6

6

spacer mats, I install blocking as a base

for the band boards, just like the corner

boards (Figure 5, page 5).

Regardless of the material used to create the vent space, you still need to install

drip cap flashing over horizontal trim. But

don’t run the drip cap all the way to the

wall sheathing over the band boards.

Doing so will break the continuity of the

airflow. Instead, treat the cap flashing like

a Z flashing, as shown in Figure 5. Its

main function is to redirect water that

enters at the siding/trim joint back out

and protect the top edge of the band

board. Run the “wall” leg of the flashing

over the face of the rain screen so air can

freely flow from intake to exhaust.

Windows and doors. Over windows

and doors, the flashing practice is different. Run cap flashings all the way to the

wall sheathing and integrate with the

housewrap (Figure 6). Any water draining

in the vent space will drain out over the

drip cap. Be sure to leave a

3

/8-inch air

space between the bottom of the shingles

and the cap flashing for air circulation.

And remember to provide insect screens

on the rain-screen material.

Keeping the vent space thickness down

to

1

/4 to 3/8 inch doesn’t pose much of a

problem. However, if thicker drainage

mats or battens are used (

3

/4 inch, for

instance), the windows and doors will

need to be padded out. The simplest fix is

to mount spacer blocks around the rough

openings that equal the thickness of whatever spacer material you’re using. Some

March/April 2007~CoastalContractor

Window Flange on Nailers Window Flange on Sheathing

BARK SIDE: FACE IN OR FACE OUT?

While most red cedar shingles are milled vertical grain, white cedar shingles are

usually cut flat grained. Many installers like to face the shingles “bark-side out”

hoping that the shingles will be less likely to curl at the outside edges and stay

flat on the wall. Checking every shingle’s growth rings is an extra time-consuming

step, though, and I’ve given up on the practice. Although I don’t have a study to

back up my position, I’ve noticed that I end up with many fewer curled shingles

since I began applying them over vented rain screens. I speculate that shingle

curling has more to do with the concentration of moisture inside a shingle than

with the ring orientation. Shingles will tend to curl toward the “dry side.” When

shingles are applied directly over a sheathed wall, the sun will drive moisture

toward the back (cooler) surface. Shingles applied over a rain-screen space will

be able to dry more readily, reducing the excess moisture built up on the back

surface and thereby reducing curling.

— M.G.

FIGURE 6. The best way to handle

the exterior trim is to mount the

window flange on furring strips

(far left). The alternative is to fur

out for the window trim after the

window is installed (left), which

works with a 1/4-inch to 3/8-inch

spacer material.

Self-adhesive

flashing

Housewrap

Plywood or

OSB nailer

Sill flashing

Plywood or

OSB nailer

Housewrap

under nailer

Metal Z

flashing

Housewrap

Self-adhesive

flashing

Plastic battens

Metal Z flashing

Sill flashing

Plastic battens

Housewrap

under sill

flashing

Page 7

7

builders don’t like this solution because it

requires extension jambs to pad the window and door jambs flush with drywall on

the inside. But if you’re framing 2x6 walls,

or using windows with 2

1

/4-inch-deep

jambs in a 2x4 wall, then you’re ripping

extension jambs anyway, so there’s no

extra labor and minimal materials.

EXHAUST-VENT DETAILING

Don’t forget to provide a route for the

rain-screen vent space to exhaust along

the top. I’ve used two different details:

Frieze-board vents require only a little

advance planning and can be incorporated after the soffit board has been

installed. Leave a

1

/2-inch space between

the last batten and the soffit board, and

cut the top of the shingles about

1

/2 inch

short of the soffit as well (Figure 7).

Then use blocks approximately

3

/8 inch

thick to space the frieze board off the surface of the shingles. In order to keep the

frieze plumb, I rip tapered blocks to apply

over the shingles at 16-inch centers. Air

flows freely between the rain-screen

space and the space behind the frieze.

Vented soffit. With a little more planning, you can eliminate these tapered

spacers, and just let the rain screen

exhaust into a vented soffit. Cut the soffit

board

1

/2 to 3/4 inch narrower than the

fascia-to-wall dimension, so there’s a gap

between the back edge of the soffit board

and the wall sheathing. This allows you to

run the rain-screen material right up to

the soffit space, and the frieze board will

conceal the gap. Air can then flow freely

from the rain-screen vent space and into

the soffit.

~

Mike Guertin (www.mikeguertin.com) is a

custom home builder and remodeler in

East Greenwich, R.I., and a member of

the JLC Live Construction Demonstration

Team leading sidewall shingling workshops. All photos by the author.

Illustrations by Chuck Lockhart.

Best-Practice

Wall Shingles

March/April 2007~CoastalContractor

RESOURCES

SPACER MATS

Enkamat, www.colbond-usa.com

Home Slicker, www.benjamin

obdyke.com

Waterway, www.stucoflex.com

PLASTIC BATTENS

Battens Plus, www.battensplus.com

Cor-A-Vent, www.cor-a-vent.com

CedarVent & RafterVent,

www.dciproducts.com/html/

cedarvent.htm

FIGURE 7. The vent space in a rain screen needs an air exhaust along the top. This can be detailed in two

ways: (1) by venting the space into the soffit (above left), or (2) by using a vented frieze board (above right).

Exhaust Vent into Soffit Vent Frieze Board

Plastic

battens

Soffit

Spaced

tapered

blocks

Frieze

Rain-screen

mat

board

Plastic

battens

Spaced tapered

blocks

Frieze board

Insect screen

Rain-screen

mat

Loading...

Loading...