Page 1

ManuScript Language Guide

for Sibelius® | Ultimate Software

Page 2

Legal Notices

© 2019 Avid Technology, Inc., (“Avid”), all rights reserved. This guide may not be duplicated in whole or in part without the written consent of Avid.

For a current and complete list of Avid trademarks visit: www.avid.com/legal/trademarks-and-other-notices

Bonjour, the Bonjour logo, and the Bonjour symbol are trademarks of Apple Computer, Inc.

Thunderbolt and the Thunderbolt logo are trademarks of Intel Corporation in the U.S. and/or other countries.

This product may be protected by one or more U.S. and non-U.S. patents. Details are available at www.avid.com/patents.

Product features, specifications, system requirements, and availability are subject to change without notice.

Guide Part Number 9329-66040-00 REV A 01/19

Page 3

Contents

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Rationale. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Technical Support . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

System Requirements and Compatibility Information . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

Conventions Used in Sibelius Documentation. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

Resources. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Sibelius ManuScript Language Tutorial. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

Edit Plug-ins . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

Editing the Code. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Loops . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Objects . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

Representation of a Score. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

The “for each” Loop. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Indirection, Sparse Arrays, and User Properties . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Dialog Editor. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Set Creation Order . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Debugging Plug-ins . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

Storing and Retrieving Pref er ences . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

Object Reference . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

Syntax. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

Expressions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

Operators . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

Object Reference . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

Hierarchy of Objects . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

All Objects . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

Accessibility. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

AnnotationItem. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

Bar. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

Barline. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

Barlines. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

BarObject . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42

BarRest . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

Bracket . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

Brackets and Braces . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

Clef . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

Comment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

ComponentList. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

Component. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

ManuScript Language Guide iii

Page 4

DateTime . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

Dictionary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

DocumentSetup . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

DynamicPartCollection. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

DynamicPart . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50

EngravingRules . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50

File. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52

Folder . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52

GuitarFrame . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53

GuitarScaleDiagram . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55

HitPointList . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55

HitPoint . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56

InstrumentChange . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56

InstrumentTypeList. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56

InstrumentType. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 57

KeySignature . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58

Line . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58

LyricItem . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58

NoteRest . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 59

Note . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61

NoteSpacingRule . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63

PageNumberChange. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 64

PluginList . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65

Plugin . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65

RehearsalMark . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65

Score. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66

Selection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71

Sibelius . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73

SoundInfo . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79

SparseArray . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 80

SpecialBarline . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 81

Staff. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 81

Syllabifier . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 83

SymbolItem and SystemSymbolItem. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 84

SystemObjectPositions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 84

SystemStaff, Staff, Selection, Bar and, all BarObject-derived Objects . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 85

SystemStaff. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 85

Text and SystemTextItem. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 85

TimeSignature. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 86

TreeNode. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 86

Tuplet . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 87

Utils . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 87

VersionHistory . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 90

Version . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91

VersionComment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91

ManuScript Language Guide

iv

Page 5

Global Constants . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 92

Global Constants . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 92

ManuScript Language Guide

v

Page 6

Introduction

ManuScript is a simple, music-based programming language used to write plug-ins for Sibelius | Ultimate. ManuScript is based on

Simkin, an embedded scripting language developed by Simon Whiteside, and has been extended by him and the rest of the Sibelius

team ever since. (Simkin is a spooky pet name for Simon sometimes found in Victorian novels.) For more information on Simkin,

and additional help on the language and syntax, visit the Simkin website at www.simkin.co.uk.

Throughout this guide, “Sibelius” refers to Sibelius | Ultimate for the sake of readability.

Rationale

Providing a plug-in language for Sibelius | Ultimate addresses several different issues:

• Music notation is complex and infinitely extensible, so some users will sometimes want to add to a music notation program to

expand its possibilities with these new extensions.

• It is useful to allow frequently repeated operations (for example, opening a MIDI file and saving it as a score) to be automated,

using a system of scripts or macros.

Certain more complex techniques used in composing or arranging music can be partly automated, but there are too many to include

as standard features in Sibelius.

There were several conditions that we wanted to meet in deciding what language to use:

• The language had to be simple, as we want normal users (not just seasoned programmers) to be able to use it.

• W e wanted plug-ins to be usable on any computer , as the use of computers running both Windows and Mac OS X is widespread

in the music world.

• We wanted the tools to program in the language to be supplied with Sibelius.

• We wanted musical concepts (pitch, notes, bars) to be easily expressed in the language.

• We wanted programs to be able to talk to Sibelius easily (to insert and retrieve information from scores).

• We wanted simple dialog boxes and other user interface elements to be easily programmed.

C/C++, the world’s “standard” programming language(s), were unsuitable as they are not easy for the non-specialist to use, they

would need a separate compiler, and you would have to recompile for each different platform you wanted to support (and thus create multiple versions of each plug-in).

The language Java was more promising as it is relatively simple and can run on any platform without recompilation. However, we

would still need to supply a compiler for people to use, and we could not express musical concepts in Java as directly as we could

with a new language.

So we decided to create our own language that is interpreted so it can run on different platforms, integrated into Sibelius without

any need for separate tools, and can be extended with new musical concepts at any time.

The ManuScript language that resulted is very simple. The syntax and many of the concepts will be familiar to programmers of

C/C++ or Java. Built into the language are musical concepts (Score, Staff, Bar, Clef, NoteRest) that are instantly comprehensible.

Introduction 1

Page 7

Technical Support

Since the ManuScript language is more the province of our programmers than our technical support team (who are not, in the main, programmers), we can’t provide detailed technical help on it, any more than Oracle will help you with Java programming. This document

and the sample plug-ins should give you a good idea of how to do some simple programming fairly quickly.

We would welcome any useful plug-ins you write – please contact us at www.sibelius.com/plugins and we may put them on our web

site; if we want to distribute the plug-in with Sibelius itself, we’ll pay you for it.

Mailing list for plug-in developers

There is a growing community of plug-in developers working with ManuScript, and they can be an invaluable source of help when writ-

ing new plug-ins. To subscribe, go to http://avid-listsrv1.avid.com/mailman/listinfo/plugin-dev.

System Requirements and Compatibility Information

Avid can only assure compatibility and provide support for hardware and software it has tested and approved.

For complete system requirements and a list of qualified computers, operating systems, hard drives, and third-party devices, visit:

www.avid.com/compatibility

Conventions Used in Sibelius Documentation

Sibelius documentation uses the following conventions to indicate menu choices, keyboard commands, and mouse commands:

:

Convention Action

File > Save Choose Save from the File tab

Control+N Hold down the Control key and press the N key

Control-click Hold down the Control key and click the mouse but-

Right-click Click with the right mouse button

ton

The names of Commands, Options, and Settings that appear on-screen are in a different font.

The following symbols are used to highlight important information:

User Tips are helpful hints for getting the most from your Sibelius system.

Important Notices include information that could affect data or the performance of your Sibelius system.

Shortcuts show you useful keyboard or mouse shortcuts.

Cross References point to related sections in this guide and other Avid documentation.

Introduction

2

Page 8

How to Use this PDF Guide

This PDF provides the following useful features:

• The Bookmarks on the left serve as a continuously visible table of contents. Click on a subject heading to jump to that page.

• Click a + symbol to expand that heading to show subheadings. Click the – symbol to collapse a subheading.

• The Table of Contents provides active links to their pages. Select the hand cursor, allow it to hove r ove r the he ading until it turns

into a finger. Then click to locate to that subject and page.

• All cross references in

• Select Find from the Edit menu to search for a subject.

• When viewing this PDF on an iPad, it is recommended that you open the file using iBooks to take advantage of active links within

the document. When viewing the PDF in Safari, touch the screen, then touch

blue are active links. Click to follow the reference.

Open in “iBooks”.

Resources

The Avid website (www.avid.com) is your best online source for information to help you get the most out of Sibelius.

Account Activation and Product Registration

Activate your product to access downloads in your Avid account (or quickly create an account if you do not have one). Register your

purchase online, download software, updates, documentation, and other resources.

www.avid.com/account

Support and Downloads

Contact Avid Customer Success (technical support), download software updates and the latest online manuals, browse the Compatibility documents for system requirements, search the online Knowledge Base or join the worldwide Avid user community on the User Conference.

www.avid.com/support

Training and Education

Study on your own using courses available online, find out how you can learn in a classroom setting at an Avid-certified training center,

or view video tutorials and webinars.

www.avid.com/education

Products and Developers

Learn about Avid products, download demo software, or learn about our Development Partners and their plug-ins, applications, and

hardware.

www.avid.com/products

Introduction

3

Page 9

Sibelius ManuScript Language Tutorial

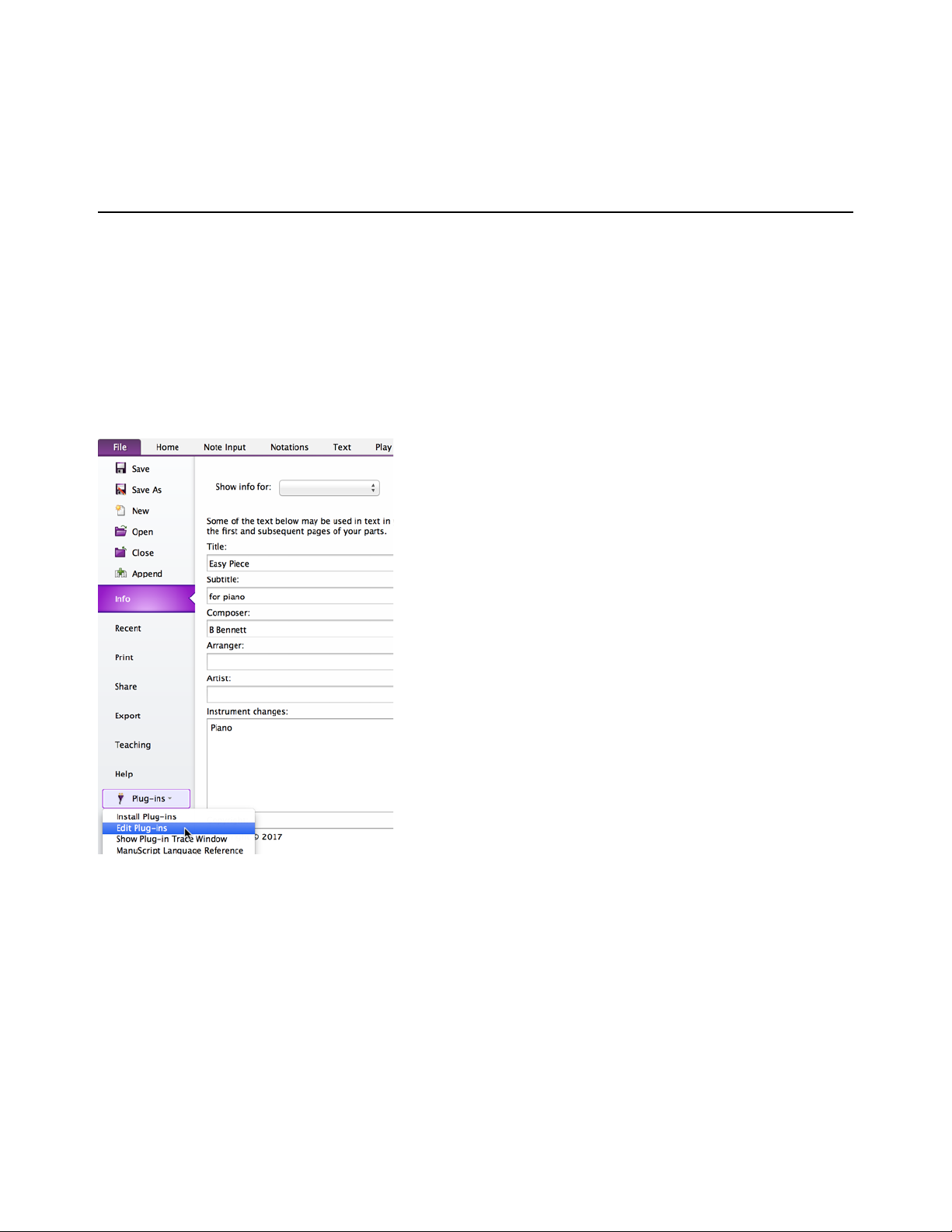

Edit Plug-ins

A Simple Plug-in

Let’s start a simple plug-in. You are assumed to have some basic experience of programming (such as BASIC or C), so you’re already familiar with ideas like variables, loops, and so on.

To create a new Sibelius plug-in:

1 Start Sibelius and open or create a new score.

2 Choose File > Plug-ins > Edit Plug-ins.

Selecting Edit Plug-ins in the File tab

Sibelius ManuScript Language Tutorial 4

Page 10

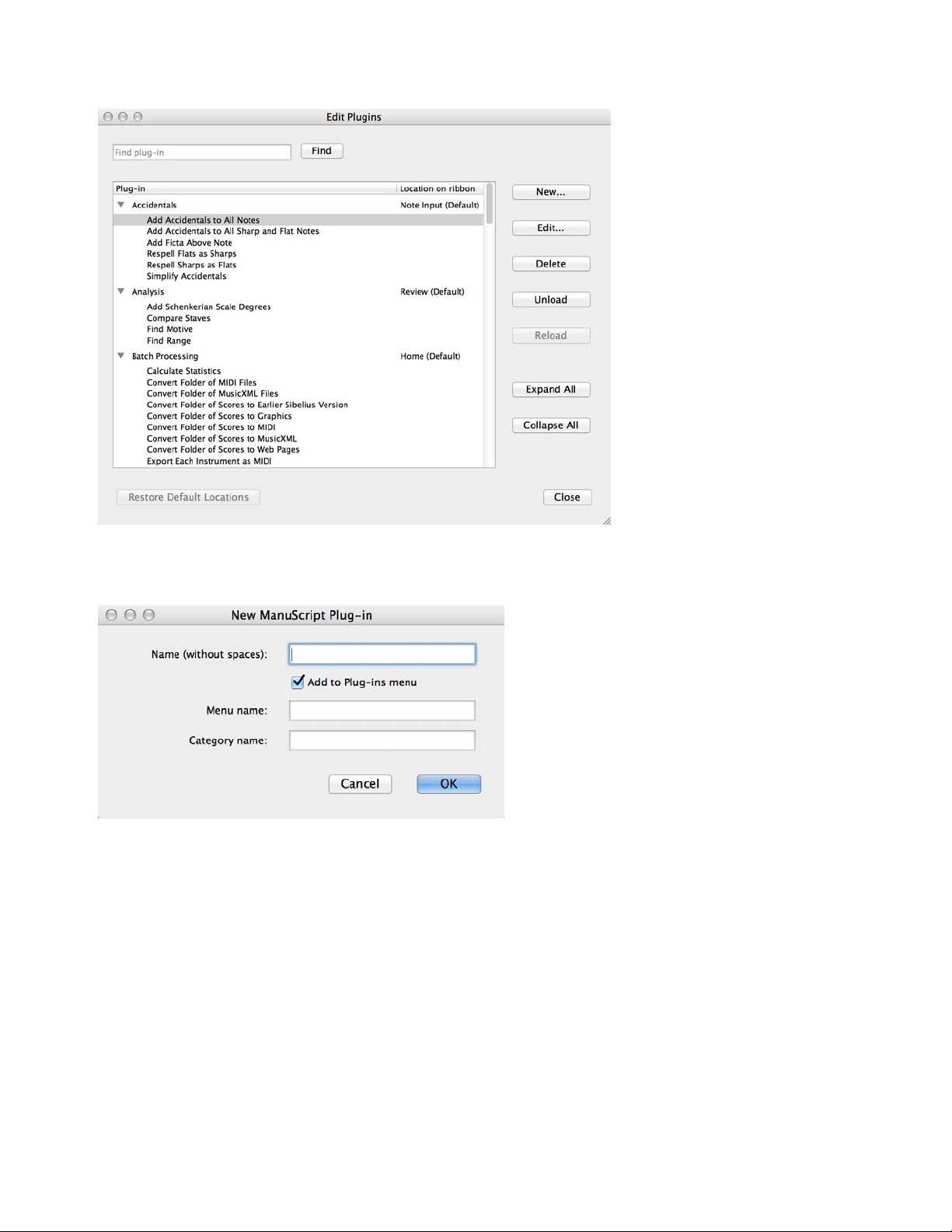

3 The following dialog appears:

Edit Plug-ins dialog

4 Click New.

New ManuScript Plug-in dialog

5 Y ou are asked to type the internal name of your plug-in (used as the plug-in’s filename), the name tha t should appear on the menu and

the name of the category in which the plug-in should appear, which will determine which ribbon tab it appears on.

6 Type Test as the internal name, Test plug-in as the menu name and Tests as the category name, then click OK.

7 Y ou’ll see Test (user copy) added to the list in the Edit Plug-ins dialog under a new T ests branch of the tree view. Click Close. This

shows the folder in which the plug-in is located (Tests, which Sibelius has created for you), the filename of the plug-in (minus the

standard .plg file extension), and (user copy) tells you that this plug-in is located in your user application data folder , not the Sibelius

program folder or application package itself.

8 If you look in the Home > Plug-ins gallery again you’ll see a Tests category, with a Test plug-in underneath it.

Sibelius ManuScript Language Tutorial

5

Page 11

9 Choose Home > Plug-ins > Tests > Test and the plug-in will run. Y ou may first be prompted that you cannot undo plug-ins, in which

case click Y es to continue (and you may wi sh to switch on the Don’ t say this again option so that you’re not bothered by this warning

in future.) What does our new Test plug-in do? It just pops up a dialog which says Test (whenever you start a new plug-in, Sibelius

automatically generates in a one-line program to do this). You’ll also notice a window appear with a button that says

Stop Plug-in,

which appears whenever you run any plug-in, and which can be useful if you need to get out of a plug-in you’re working on that is

(say) trapped in an infinite loop.

10 Click OK on the dialog and the plug-in stops.

Three Types of Information

Let’s look at what’s in the plug-in so far. Choose File > Plug-ins > Edit Plug-ins again, then select Tests/Test (user copy) from the list

and click

make up a plug-in:

Edit (or simply double-click the plug-in’s name to edit it). You’ll see a dialog showing the three types of information that can

Methods

Dialogs

Data

Similar to procedures, functions, or routines in some other languages.

The layout of any special dialogs you design for your plug-in.

Variables whose value is remembered between running the plug-in. You can only store strings in these variables, so they’re useful

for things like user-visible strings that can be displayed when the plug-in runs. For a more sophisticated approach to global variables,

ManuScript provides custom user properties for all objects—see

Edit Plug-ins.

Example: Test plug-in

Methods

The actual program consists of the methods. As you can see, plug-ins normally have at least two methods, which are created automatically for you when you create a new plug-in:

Initialize

This method is called automatically whenever you start up Sibelius. Normally it does nothing more than add the name of the plug-in to

the Plug-ins menu, although if you look at some of the supplied plug-ins you’ll notice that it’s sometimes also used to set default values

for data variables.

Run

This is called when you run the plug-in, you’ll be startled to hear (it’s like main() in C/C++ and Java). In other words, when you

Home > Plug-ins > Tests > Test, the plug-in’s Run method is called. If you write any other methods, you have to call them from

choose

the Run method—otherwise how can they ever do anything?

6

Sibelius ManuScript Language Tutorial

Page 12

Click on Run, then click Edit (or you can just double-click Run to edit it). This shows a dialog where you can edit the Run method:

ManuScript Method dialog

In the top field you can edit the name; in the next field you can edit the parameters (the variables where values passed to the method are

stored); and below is the code itself:

Sibelius.MessageBox("Test");

This calls a method MessageBox which pops up the dialog box that says Test when you run the plug-in. Notice that the method name

is followed by a list of parameters in parentheses. In this case there’s only one parameter: because it is a string (that is, text) it is in double

quotes. Notice also that the statement ends in a semicolon, as in C/C++ and Java. If you forget to type a semicolon, you’ll get an error

when the plug-in runs.

What is the role of the word Sibelius in

Sibelius.MessageBox? In fact it’s a variable representing the Sibelius program; the state-

ment is telling Sibelius to pop up the message box (C++ and Java programmers will recognize that this variable refers to an “object”).

If this hurts your brain, we’ll go into it later.

Editing the Code

Now try amending the code slightly. You can edit the code just like in a word processor, using the mouse and arrow keys, and you can

also use Command+X/C/V (Mac) or Control+X/C/V (Windows) for cut, copy and paste respectively. If you right-click, you get a menu

with these basic editing operations on them as well.

Change the code to this:

x = 1;

x = x + 1;

Sibelius.MessageBox("1 + 1 = " & x);

You can check this makes sense (or, at least, some kind o f sense) by clicki ng the Check Syntax button. If there are any blatant mistakes

(e.g. missing semicolons) you will be notified where they are.

Then close the dialogs by clicking

with the answer

1 + 1 = 2 should appear.

How does it work? The first two lines should be obvious. The last line uses

only for numbers (if you try it in the example above, you will get an interestin g answer!).

One pitfall: try changing the second line to:

x += 1;

OK, OK again then Close. Run your amended plug-in from the Plug-ins menu and a message box

& to stick two strings together. You cannot use + as this works

Then click Check syntax. You will encounter an error: this syntax (and the syntax x++) is allowed in various languages but not in

ManuScript. You have to do

Sibelius ManuScript Language Tutorial

x = x+1;.

7

Page 13

Where Plug-ins are Stored

Plug-ins supplied with Sibelius are stored in folders buried deep within the Sibelius program folder on Windows, and inside the application package (or “bundle”) on Mac. It is not intended that end users should add extra plug-ins to these loc ations themselves, as we have

provided a per-user location for plug-ins to be installed instead. When you create a new plug-in or edit an existing one, the new or modified plug-in will be saved into the per-user location (rather than modifying or adding to the plug-ins in the program folder or bundle):

• On Windows, additional plug-ins are stored at

• On Mac, additional plug-ins are stored in subfolders at

This is worth knowing if you want to give a plug-in to someone else. The plug-ins appear in subfolders which correspond to the cate-

gories in which they appear in the various Plug-ins galleries. The filename of the plug-in itself is the plug-in’s internal name plus the

.plg extension, such as Test.plg.

C:\Users\<username>\AppData\Roaming\Avid\Sibelius\Plugins.

/Users/<username>/Library/Application Support/Avid/Sibelius/Plugins.

(Sibelius includes an automatic plug-in installer, which you can access via

File > Plug-ins > Install Plug-ins. This makes it easy to

download and install plug-ins from the Avid website.)

Line Breaks and Comments

As with C/C++ and Java, you can put new lines wherever you like (except in the middle of words), as long as you remember to put a

semicolon after every statement. You can put several statements on one line, or put one statement on several lines.

You can add comments to your program, again like C/C++ and Java. Anything after

/* and */ is ignored, whether just part of a line or several lines:

tween

// comment lasts to the end of the line

/* you can put

several lines of comments here

*/

// is ignored to the end of the line. Anything be-

For instance:

Sibelius.MessageBox("Hi!"); // print the active score

or:

Sibelius /* this contains the application */ .MessageBox("Hi!");

Variables

x in the Test plug-in is a variable. In ManuScript a variable can be any sequence of letters, digits or _ (underscore), as long as it does

not start with a digit.

A variable can contain an integer (whole number), a floating point number, a string (text) or an objec t (such as a note )—more about ob-

jects in a moment. Unlike most languages, in ManuScript a variable can contain any type of data—you do not have to declare what type

you want. Thus you can store a number in a variable, then store some text instead, then an object.

Try this:

x = 56; x = x+1;

Sibelius.MessageBox(x); // prints '57' in a dialog box

x = "now this is text"; // the number it held is lost

Sibelius.MessageBox(x); // prints 'now this is text' in a dialog

x = Sibelius.ActiveScore; // now it contains a score

Sibelius.MessageBox(x); // prints nothing in a dialog

Variables that are declared within a ManuScript method are local to that method; in other words, they cannot be used by other methods

in the same plug-in. Global Data variables defined using the plug-in editor can be accessed by all methods in the plug-in, and their values

are preserved over successive uses of the plug-in.

A quick aside about strings in ManuScript is in order at this point. Like many programming languages, ManuScript strings uses the

back-slash

to include a new line you should use

Sibelius ManuScript Language Tutorial

\ as an “escape character” to represent certain special things. To include a single quote character in your strings, use \', and

\n. Because of this, to include the backslash itself in a ManuScript string one has to write \\.

8

Page 14

Converting Between Numbers, Text, and Objects

Notice that the method MessageBox is expecting to be sent some text to display. If you give it a number instead (as in the first call to

MessageBox above) the number is converted to text. If you give it an object (such as a score), no text is produced.

Similarly, if a calculation is expecting a number but is given some text, the text will be converted to a number:

x = 1 + "1"; // the + means numbers are expected

Sibelius.MessageBox(x); // displays '2'

If the text doesn’t start with a number (or if the variable contains an object instead of text), it is treated as 0:

x = 1 + "fred";

Sibelius.MessageBox(x); // displays ‘1’

Loops

“for” and “while”

ManuScript has a while loop which repeatedly executes a block of code unti l a certain expressi on becomes True. Crea te a new plug-in

called Potato. This is going to amuse one and all by writing the words of the well-known song “1 potato, 2 potato, 3 potato, 4.” Type

in the following for the Run method of the new plug-in:

x = 1;

while (x<5)

{

text = x & " potato,";

Sibelius.MessageBox(text);

x = x+1;

}

Run it. It should display “1 potato,” “2 potato,” “3 potato,” “4 potato,” which is a start, though annoyingly you have to click OK after

each message.

while statement is followed by a condition in ( ) parentheses, then a block of statements in { } braces (you don’t need a semi-

The

colon after the final

} brace). While the condition is true, the block is executed. Unlike some other languages, the braces are compulsory

(you can’t omit them if they only contain one statement). Moreover, each block must contain at least one statement.

In this example you can see that we are testing the value of

construct could be expressed more concisely in ManuScript by using a

for x = 1 to 5

{

text = x & " potato,";

Sibelius.MessageBox(text);

}

x at the start of the loop, and increasing the value at the end. This common

for loop. The above example could also be written as follows:

Here, the variable x is stepped from the first value (1) up to the end value (5), stopping one step before the final value. By default, the

“step” used is 1, but we could have used (say) 2 by using the syntax

for x = 1 to 5 step 2, which would then print only “1 potato”

and “3 potato”!

Notice the use of

& to add strings. Because a string is expected on either side, the value of x is turned into a string.

Notice also we’ve used the Tab key to indent the statements inside the loop. This is a good habit to get into as it makes the structure

clearer. If you have loops inside loops you should indent the inner loops even more.

Sibelius ManuScript Language Tutorial

9

Page 15

The if statement

Now we can add an if statement so that the last phrase is just “4,” not “4 potato”:

x = 1;

while (x<5)

{

if(x=4)

{

text = x & ".";

}

else

{

text = x & " potato,";

}

Sibelius.MessageBox(text);

x = x+1;

}

The rule for if takes the form if (condition) {statements}. You can also optionally add else {statements}, which is executed if the condition is false. As with

by putting braces on the same line as other statements:

x = 1;

while (x<5)

{

if(x=4) {

text = x & ".";

} else {

text = x & " potato,";

}

Sibelius.MessageBox(text);

x = x+1;

}

while, the parentheses and braces are compulsory, though you can make the program shorter

The position of braces is entirely a matter of taste.

Now let’s make this plug-in really cool. We can build up the four messages in a variable called

valuable wear on your mouse button. We can also switch round the

for syntax we looked at earlier.

the

text = ""; // start with no text

for x = 1 to 5

{

if (not(x=4)) {

text = text & x & " potato, "; // add some text

} else {

text = text & x & "."; // add no. 4

}

}

Sibelius.MessageBox(text); // finally display it

if and else blocks to show off the use of not. Finally, we return to

text, and only display it at the end, saving

Sibelius ManuScript Language Tutorial

10

Page 16

Arithmetic

Here is a complete list of the available arithmetic operators in ManuScript:

a + b

a – b

a * b

a / b

a % b

–a

a)

ManuScript evaluates operators strictly from left-to-right, unlike many other languag es; so

expect. To get the answer 14, you’d have to write

add

subtract

multiply

divide

remainder

negate

evaluate first

2+3*4 evaluates to 20, not 14 as you might

2+(3*4).

ManuScript supports both integers and floating point numbers. Use at least one floating point value in any arithmetic operation that

might result in a floating point number, otherwise the result is rounded to the nearest integer (unless you are using literal strings). For

instance, when calculating division using only integer values, the result is truncated; for example, the result of

3/2 i s 1. However, using

at least one floating point value in the calculation results in a floating point number (this is true if any or all of the values are a floating

point number); for example, the result of

Conversion from floating point numbers to integers can be achieved with the

3.0/2 is 1.5.

RoundUp(expr), RoundDown(expr), and Round(expr)

functions, which can be applied to any expression.

Objects

Now we come to the neatest aspect of object-oriented languages like ManuScript, C++ or Java, which sets them apart from traditi onal

languages like BASIC, Fortran and C. Variables in traditional languages can hold only certain types of data: integers, floating point

numbers, strings and so on. Each type of da ta has pa rticu lar op era ti ons you ca n do to it : numb ers can be multiplied and divided, for instance; strings can be added together, converted to and from numbers, searched for in other strings, and so on. But if your program deals

with more complex types of data, such as dates (which in principle you could compare using =, < and >, convert to and from strings, and

even subtract) you are left to fend for yourself.

Object-oriented languages can deal with more complex types of data directly. Thus in the ManuScript language you can set a variable,

let’s say

If this seems magic, it’s just analogous to the kind of things you can do to strings in BASIC, where there are very special operations

which apply to text only:

In ManuScript you can set a variable to be a chord, a note in a chord, a bar, a staff or even a whole score, and do things to it. Why would

you possibly want to set a variable to be a whole score? So you can save it or add an instrument to it for instance.

thischord, to be a chord in your score, and (say) add more notes to it:

thischord.AddNote(60); // adds middle C (note no. 60)

thischord.AddNote(64); // adds E (note no. 64)

A$ = "1"

A$ = A$ + " potato, ": REM add strings

X = ASC(A$): REM get first letter code

Sibelius ManuScript Language Tutorial

11

Page 17

Objects in Action

We’ll have a look at how music is represented in ManuScript in a moment, but for a little taster, let’s plunge straight in and adapt Potato

to create a score:

x = 1;

text = ""; // start with no text

while (x<5)

{

if (not(x=4)) {

text = text & x & " potato, "; // add some text

} else {

text = text & x & "."; // add no. 4

}

x = x+1;

}

Sibelius.New(); // create a new score

newscore = Sibelius.ActiveScore; // put it in a variable

newscore.CreateInstrument("Piano");

staff = newscore.NthStaff(1); // get top staff

bar = staff.NthBar(1); // get bar 1 of this staff

bar.AddText(0,text,"Technique"); // use Technique text style

This creates a score with a Piano, and types our potato text in bar 1 as Technique text.

The code uses the period (

.) several times, always in the form variable.variable or variable.method(). This shows that the

variable before the period has to contain an object.

If there’s a variable name after the period, we’re getting one of the object’s sub-variables (called “fields” or “member variables” in some

languages). For instance, if

n.Name is a string describing its pitch (“C4” for middle C). The variables available for each type of object are listed later.

If there’s a method name after the period (followed by

ically a method called in this way will either change the object or return a value. For instance, if

s.CreateInstrument("Flute") adds a flute (changing the score), but s.NthStaff(1) returns a value, namely an object con-

n is a variable containing a note, then n.Pitch is a number representing its MIDI pitch (60 fo r middle C), and

() parentheses), one of the methods allowed for this type of object is called. Typ-

s is a variable containing a score, then

taining the first staff.

Let’s look at the new code in deta il . T he re is a pr e -def i ne d variable called Sibelius, which contains an object representing the Sibelius

program itself. We’ve already seen the method

Sibelius.MessageBox(). The method call Sibelius.New() tells Sibelius to cre-

ate a new score. Now we want to do something to this score, so we have to put it in a variable.

Fortunately, when you create a new score it becomes active (i.e. its title bar highlights and any other scores become inactive), so we can

just ask Sibelius for the active score and put it in a variable:

newscore = Sibelius.ActiveScore

Then we can tell the score to create a Piano: newscore.CreateInstrument("Piano"). But to add some text to the score you

have to understand how the layout is represented.

Representation of a Score

A score is treated as a hierarchy: each score contains 0 or more staves; each staff contains bars (though every staff contains the same

number of bars); and each bar contains “bar objects.” Clefs, text and chords are all different types of bar objects.

To add a bar object (i.e. an object which belongs to a bar), such as some text, to a score:

1 Specify which staff you want (and put it in a variable): staff = newscore.NthStaff(1).

2 Specify which bar in that staff you want (and put it in a variable): bar = staff.NthBar(1); finally you tell the bar to add the

bar.AddText(0,text,"Technique").

text:

3 Specify the name (or index number – see Text styles on page 141) of the text style to use (and it has to be a staff text style, because

we’re adding the text to a staff).

12

Sibelius ManuScript Language Tutorial

Page 18

Notice that bars and staves are numbered from 1 upwards; in the case of bars, this is irrespective of any bar number changes that are in

the score, so the numbering is always unambiguous. In the case of staves, the top staff is no.1, and all staves are counted, even if they’re

hidden. Thus a particular staff has the same number wherever it appears in the score.

AddText method for bars is documented later, but the first parameter it takes is a rhythmic position in the bar. Each note in a bar

The

has a rhythmic position that indicates where it is (at the start, one quarter after the start, etc.), but the same is true for all other objects

in bars. This shows where the object is attached to, which in the case of Technique text is also where the left hand side of the text goes.

Thus to put our text at the start of the bar, we used the value 0. To put the text a quarter note after the start of the bar, use 256 (the units

are 1024th notes, so a quarter is 256 units):

bar.AddText(256,text,"Technique");

To avoid having to use obscure numbers like 256 in your program, there are predefined variables representing different note values

(which are listed later), so you could write:

bar.AddText(Quarter,text,"Technique");

or to be quaint you could use the British equivalent:

bar.AddText(Crotchet,text,"Technique");

For a dotted quarter, instead of using 384 you can use another predefined variable:

bar.AddText(DottedQuarter,text,"Technique");

or add two variables:

bar.AddText(Quarter+Eighth,text,"Technique");

This is much clearer than using numbers.

The System Staff

As you know from using Sibelius, some objects don’t apply to a single staff but to all staves. These include titles, tempo text, rehearsal

marks and special barlines; you can tell they apply to all staves because (for instance) they get shown in all the instrumental parts.

All these objects are actually stored in a hidden staff, called the system staff. You can think of it as an invisible staff which is always

above the other staves in a system. The system staff is divided into bars in the same way as the normal staves. So to add the title “Potato”

to our score we’d need the following code in our plug-in:

sys = newscore.SystemStaff; // system staff is a variable

bar = sys.NthBar(1);

bar.AddText(0,"POTATO SONG","Subtitle");

As you can see, SystemStaff is a variable you can get directly from the score. Remember that you have to use a system text style (here

Subtitle is used) when putting text in a bar in the system staff. A staff text style like Technique won’t work. Also, you have to specify

a bar and position in the bar; this may seem slightly superfluous for text centered on the page as titles are (though in reality even this

kind of page-aligned text is always attached to a bar), but for Tempo and Metronome mark text they are obviously required.

Representation of Notes, Rests, Chords, and Other Musical Items

Sibelius represents rests, notes and chords in a consistent way. A rest has no noteheads, a note has 1 notehead and a chord has 2 or more

noteheads. This introduces an extra hierarchy: most of the squiggles you see in a score are actually a special type of

contain even smaller things (namely, noteheads). There’s no overall name for something which can be a rest, note or chord, so we’ve

invented the pretty name

NoteRest. A NoteRest with 0, 1 or 2 noteheads is what you normally call a rest, a note or a chord, respec-

tively.

n is a variable containing a NoteRest, there is a variable n.NoteCount which contains the number of notes, and n.Duration

If

which is the note-value in 1/256ths of a quarter. You can also get

notes (assuming

lownote.Pitch (a number) and lownote.Name (a string). Complete details about all these methods and variables may be found

as

Object Reference.

in

n.NoteCount isn’t 0). If you set lownote = n.Lowest, you can then find out things about the lowest note, such

n.Highest and n.Lowest which contain the highest and lowest

Bar object that can

Other musical objects, such as clefs, lines, lyrics and key signatures have corresponding objects in ManuScript, which again have various variables and methods available. For example, if you have a

Line variable ln, then ln.EndPosition gives the rhythmic posi-

tion at which the line ends.

13

Sibelius ManuScript Language Tutorial

Page 19

The “for each” Loop

It’s a common requirement for a loop to do some operation to every staff in a score, or every bar in a staff, or every Bar object in a bar,

or every note in a NoteRest. There are other more complex requirements which are still common, such as doing an operation to every

Bar object in a score in chronological order, or to every Bar object in a multiple selection. ManuScript has a for each loop that can

achieve each of these in a single statement.

The simplest form of for each is like this:

thisscore = Sibelius.ActiveScore;

for each s in thisscore // sets s to each staff in turn

{ // ...do something with s

}

Here, since thisscore is a variable containing a score, the variable s is set to be each staff in thisscore in turn. This is because

staves are the type of object at the next hierarchical level of objects (see

Hierarchy of Objects).

For each staff in the score, the statements in

Score objects contain staves, as we have seen, but they can also contain a Selection object, e.g. if the user has selected a passage

of music before running the plug-in. The

is only a single

Selection object; if you use the Selection object in a for each loop, by default it will return Bar objects (not

{} braces are executed.

Selection object is a special case: it is never returned by a for each loop, because there

Staves, Bars or anything else!).

Let’s take another example, this time for notes in a NoteRest:

noterest = bar.NthBarObject(1);

for each n in noterest // sets n to each note in turn

{

Sibelius.MessageBox("Pitch is " & n.Name);

}

is set to each note of the chord in turn, and its note name is displayed. This works because Notes are the next object down the hierarchy

n

after NoteRests. If the NoteRest is, in fact, a rest (rather than a note or chord), the loop will never be executed—you do n’t have to check

this separately.

The same form of loop will get the bars from a staff or system staff, and the

Bar objects from a bar. These loops are often nested, so

you can, for instance, get several bars from several staves.

This first form of the for each loop got a sequence of objects from an object in the next level of the hierarchy of objects. The second form

of the for each loop lets you skip levels of the hierarchy, by specifying what type of object you want to get. This saves a lot of nested

loops:

thisscore = Sibelius.ActiveScore;

for each NoteRest n in thisscore

{

n.AddNote(60); // add middle C

}

By specifying NoteRest after for each, Sibelius knows to produce each NoteRest in each bar in each staff in the score; otherwise it would

just produce each staff in the score, because a

Staff object is the type of object at the next hierarchical level of objects. The NoteRests

are produced in a useful order, namely from the top to the bottom staff, then from left to right through the bars. This is chronological

order. If you want a different order (say, all the NoteRests in the first bar in every staff, then all the NoteRests in the second bar in every

staff, and so on) you’ll have to use nested loops.

So here’s some useful code that doubles every note in the score in octaves:

score = Sibelius.ActiveScore;

for each NoteRest chord in score

{

if(not(chord.NoteCount = 0)) // ignore rests

{

note = chord.Highest; // add above the top note

chord.AddNote(note.Pitch+12); // 12 is no. of half-steps (semitones)

}

}

14

Sibelius ManuScript Language Tutorial

Page 20

It could easily be amended to double in octaves only in certain bars or staves, only if the notes have a certain pitch or duration, and so on.

This kind of loop is also very useful in conjunction with the user’s current selection. This selection can be obtained from a variable con-

taining a

Score object as follows:

selection = score.Selection;

We can then test whether it’s a passage selection, and if so we can look at (say) all the bars in the selection by means of a for each

loop:

if (selection.IsPassage)

{

for each Bar b in selection

{

// do something with this bar

…

}

}

Be aware that you can not add or remove items from bars during iterating. The example of adding notes to chords above is fine because

you are modifying an existing item (in this case a NoteRest), but it’s not safe to add or remove entire items, and if you try to do so, your

plug-in will abort with an error. However, it’s very useful to add or remove items from bars, so you need to do that in a separate

for

loop, after first collecting the items you want to operate on into a ManuScript array, something like this:

num = 0;

for each obj in selection

{

if (IsObject(obj))

{

n = "obj" & num;

@n = obj;

num = num + 1;

}

}

selection.Clear();

for i = 0 to num

{

n = "obj" & i;

obj = @n; // get an object from the pseudo array

obj.Select();

}

The @n in this example is the array.

Indirection, Sparse Ar rays, and User Properties

Indirection

If you put the @ character before a string variable name, then the value of the variable is used as the name of a variable or method. For

instance:

var="Name";

x = @var; // sets x to the contents of the variable Name

mymethod="Show";

@mymethod(); // calls the method Show

This has many advanced uses, though if taken to excess it can cause the brain to hurt. For instance, you can use @ to simulate “unlimited”

arrays. If

sets variable x10 to 0. The last two lines are equivalent to x[i] = 0; in the C language. This has many uses; however, you’ll also

want to consider using the built-in arrays (and hash tables), which are documented below.

Sibelius ManuScript Language Tutorial

name is a variable containing the string "x1", then @name is equivalent to using the variable x1 directly. Thus:

i = 10;

name = "x" & i;

@name = 0;

15

Page 21

Sparse Arrays

The method described above can be used to create “fake” arrays through indirection, though this is a little fiddly. ManuScript also provides Javascript-style sparse arrays, which can store anything that can be stored in a ManuScript variable, including references to objects. Like a variable, storing a reference to an object in a sparse array will preserve the lifetime of that object (because objects are reference counted), but the underlying object in Sibelius may become invalid if (say) a Score is modified.

To create a sparse array in ManuScript, use the built-in method

ray simply by passing in no variables to the

CreateSpareArray method.

CreateSparseArray(a1,a2,a3,a4...an). You can create an empty ar-

Sparse arrays provide a read/write variable called Length that returns or sets the length of the array: when you set Length to a number

greater than the present size of the array, the array is padded with null values; if you set Length to a number smaller than the present size

of the array, any values beyond this number are removed.

To push one or more values to the end of the array, use the method

array, use the method

Pop().

Push(a1, a2, ... an). To remove and return the last element of an

An example of how to use a sparse array:

array = CreateSparseArray(4,5,6);

array[10] = 19; // creates 11th element of array, intervening elements are null

array.Length = 20; // extends array to 20 elements, new elements are all null

Sparse arrays by their nature may not have values in every array element. To return a new sparse array containing only the populated

indices of the original sparse array (those that are not null), use the array’s

ValidIndices variable. For example, using the above

sparse array:

array2 = array.ValidIndices; // will contain values 0, 1, 2, 10 and 19

return array[array2[0]]; // returns the first populated element of array

You can compare two sparse arrays for equality, for example:

if (array = array2) {

// do something

}

To access the end of an array, it’s convenient to use negative indices; e.g. array[-1] returns the last element, array[-2] returns the

penultimate element, and so on. It’s not possible to access elements before the start of the array, so if you do e.g.

six element array, you will get

array[0] returned.

array[-100] on a

Some things to remember when using sparse arrays:

• Sparse arrays use a zero-based index.

• Elements that have not been initialized are null, and do not cause an error when referenced.

• Assigning to an index beyond the current length increases the Length to one greater than the index is assigned to.

• If an array contains references to objects, whether the arrays are equal or not depends on the implementation of equality for those

objects.

User Properties

All ManuScript objects other t han tho se liste d bel ow, incl udi ng objects created by Sibelius, can have user properties attached to them,

allowing for convenient storage of extra data, encapsulation of several items of data within a single object, and returning more than one

value from a method, among other things.

To create a new user property, use the following syntax:

object._property:property_name = value;

where object is the name of the object, property_name is the desired user property name, and value is the value to be assi gned to

the new user property. User properties are read/write and can be accessed as

To get a sparse array containing the names of all the user properties belonging to an object:

names = object._propertyNames;

object.property_name.

Sibelius ManuScript Language Tutorial

16

Page 22

Here is an example of creating a user property:

nr = bar.NoteRest;

nr._property:original = true;

if (nr.original = true) {

// do something

}

Some things to remember when using user properties:

• If you attempt to get or set a user property that has not yet been created, your plug-in will exit with a run-time error.

• To check whether or not a user property has been created without causing a run-time error, use the notation

erty:

property_name, which will be null if no matching user property has been created yet.

• User properties cannot be created or accessed for normal data types (e.g. strings, integers, etc.), the global

old-style ManuScript arrays created by

• User properties that conflict with an existing property name cannot be accessed as

accessed using the

._property: notation).

CreateArray(), old-style hashes created by CreateHash(), and null.

object.property_name (though they can be

object._prop-

Sibelius object,

• User properties belong to a particular ManuScript object and disappear when that object’s lifetime ends. To stop an object dying,

you can (for example) store it in a sparse array, but be aware that its contents may become invalid if (say) the underlying score

changes.

Dictionary

Dictionary is a programmer extensible object, simply allowing the use of user properties as above with convenient construction. It

also has methods allowing the use of arbitrarily named user properties, and can also have methods in plug-ins attached to it allowing the

creation of encapsulated user objects (i.e. objects with variables and methods attached to them).

To create a dictionary, use the built-in function

CreateDictionary(name1, value1, name2, value2, ... nameN, valueN). This creates

a dictionary containing user properties called name1, name2, nameN with values value1, value2, valueN respectively.

A dictionary can contain named data items (like a

struct in languages like C++), or data that is indexed by string, so that you can use

strings to look items up within it.

The values in a dictionary can be accessed using square bracket notation, so you can use a dictionary like a hash table. For example:

test = CreateDictionary("fruit",apple,"vegetable",potato);

test["fruit"] = banana;

test["meat"] = lamb;

You can even put other objects, such as sparse arrays, inside dictionaries. For example:

test2 = CreateDictionary("fruit",

CreateSparseArray(apple,banana,orange));

You can access the user properties within a dictionary using the ._property: notation. For example:

return test2._property:fruit;

which would return the array spec ified above. Even more di rect, you can access user propert ies in a dictionary as if they were variables

or methods, like this:

test2.fruit;

which would also return the array specified above. You can also return more than one value from any ManuScript method using a dictionary, such as:

getChord()

value = CreateDictionary("a", aNote, "b", anotherNote);

return value;

//... in another method somewhere

chord = getChord();

trace(chord.a);

trace(chord.b);

which returns two values, a and b, which you can access via e.g. chord.a and chord.b.

Sibelius ManuScript Language Tutorial

17

Page 23

You can compare two dictionaries for equality. For example:

if (test2 = test3) {

// do something

}

Whether or not dictionaries containing objects evaluate as equal depends on the implementation of equality for those objects.

If you’re comfortable with programming in general, you may find it useful to be able to add methods to dictionaries, particularly if you

are writing code designed to act as a library for other methods or plug-ins to call. Writing code in this way provides a degree of encapsulation and can make it easy for client code to use your library.

To add a method to a dictionary, call the dictionary’s

pluginmethod "(obj,x,y) {

// a method that does something to obj

}"

test4 = CreateDictionary();

test4.SetMethod("doSomething",Self,"pluginmethod");

test4.doSomething(3,4);

// call pluginmethod within the current plug-in, passing in

// test4 (obj in the method above) and 3 (x in the method

// above) and 4 (y in the method above)

SetMethod() method. For example:

In the example above, doSomething is the name of the method belonging to the dictionary, Self tells the plug-in that the method is

defined in the same plug-in, and pluginmethod is the name of a method elsewhere in the plug-in (shown at the top of the example).

To return a sparse array containing the names of the methods belonging to a dictionary, use the dictionary’s

method. You can also check the existence of a particular method using the dictionary’s

CallMethod() method to call a specific method, where the name of the method is the first parameter, and any parameters to

nary’s

MethodExists() method. Use the dictio-

GetMethodNames()

be passed to the specified method follow.

For example:

array = test4.GetMethodNames(); // create sparse array containing method names

first_method_name = array[0]; // sets first_method_name to name of first method

methodfound = test4.MethodExists("doSomething"); // returns True in this case;

test4.CallMethod("doSomething",5,6);

Everything you put into a dictionary is a user property, so all of the methods outlined in User properties above can be used on data in

dictionaries too.

Using User Properties as Global Variables

You can store SparseArray and Dictionary objects, and indeed any other object, as user properties of the Plugin object itself.

In the example below,

plug-in, containing a Dictionary:

Self._property:globalData = CreateDictionary(1,2,3,4);

// globalData and Self.globalData can be used interchangeably

trace(globalData);

trace(Self.globalData);

User properties assigned to the plug-in are persistent between invocations. Take care to ensure that these user properties are created before you attempt to use them, otherwise your plug-in will abort with a run-time error. Using the

never causes run-time errors, but direct references to property_name force a runtime error if property_name hasn't been created yet.

Sibelius ManuScript Language Tutorial

Self is the object that corresponds to the running plug-in, and a user property globalData is assigned to the

_property:property_name syntax

18

Page 24

The example below shows how to test the existence of a specific user property, globalCounter, initialize it to 0 if it is not found, then

increment it by 1 every time the plug-in runs:

// Test the persistence of user properties

if (Self._property:globalCounter = null) {

Self._property:globalCounter = 0;

}

globalCounter = globalCounter + 1;

// this number increases by one every time the plug-in is run

trace(globalCounter);

trace(Self.globalCounter);

If you store a reference to a musical object in a user property that is assigned to the plug-in, there is an increased danger of that reference

becoming invalid due to the score being closed or edited, etc. Use the

IsValid() method to validate such data before using it.

User properties of plug-ins will be inaccessible (except by using the

variable of the same name.

_property:property_name syntax) if there is an existing global

Watch Out for Recursive Cycles!

Be careful not to create recursive cycles using arrays, user properties and dictionaries. When you use, say, an array in a dictionary, you

are not creating a copy of the array or its values, but a reference to the original array: dictiona ries and arrays are objects, not values. As

a result, you could write something where an array contains a dictionary that itself refers to the original array: this will lead to Sibelius

crashing. So be careful!

Other Things to Look Out For

The Parallel 5ths and 8ves plug-in illustrates having several methods in a plug-in, which we haven’t needed so far. The Proof-read

plug-in illustrates that one plug-in can call another – it doesn’t do much itself except call the CheckPizzicato, CheckSuspectClefs,

CheckRepeats and CheckHarpPedaling plug-ins. Thus you can build up meta-plug-ins that use libraries of others. Cool!

(You object-oriented programmers should be informed that this works because, of course, each plug-in is an object with the same powers as the objects in a score, so each one can use the methods and variables of the others.)

Dialog Editor

For more complicated plug-ins than the ones we’ve been looking at so far, it can be useful to prompt the user for various settings and

options. This may be achieved by using ManuScript’s simple built-in dialog editor. Dialogs can be created in the same way as methods

and data variables in the plug-in editor.

Showing a Dialog in a Plug-In

To show a dialog from a ManuScript method, we use the built-in call

Sibelius.ShowDialog(dialogName, Self);

where dialogName is the name of the dialog we wish to show, and Self is a “special” variable referring to this plug-in (telling Sibelius to whom the dialog belongs). Control will only be returned to the method once the dialog has been closed by the user.

Creating or Editing a Dialog

To create a new dialog, choose the Dialog radio button at the bottom of the window that lists methods, data and dialogs, and click Add.

To edit an existing dialog, select it from the Dialogs list box at the top right-hand corner of the window, and click

Sibelius ManuScript Language Tutorial

Edit.

19

Page 25

The dialog form will then appear, along with a long thin “palette” of available controls, as follows:

Radio button

Checkbox

Button

Static text

Editable text

Combo box

List box

Group box

Control palette

To create a new control, just drag and drop it from the palette onto the dialog.

Dialog Properties

With no controls selected, either double-click on a blank part of the dialog (or right-click, and then choose Properties) to access the dialog’s Properties dialog, which allows you to specify:

• Name: the value of dialogName for the

• Title: the name of the dialog as it appears in its title bar.

• Size: the Width and Height (measured in somewhat arbitrary dialog units); you can also set the size of the dialog by resizing it directly

when editing it.

• Position: the X and Y position that the dialog should open at by default.

Sibelius.ShowDialog() method call (see Showing a dialog in a plug-in above).

Laying Out Controls

The dialog editor includes a number of simple options for producing a pleasing layout:

• To select a control, either click it or hit Tab to select the next control in the creation order (Shift-Tab selects the previous control).

• To nudge a selected control, use the arrow keys.

• To align controls, select them using Command-click (Mac) or Control-click (Windows), then use Command+Left Arrow (Mac) or

• To space controls evenly, select them using Command-click (Mac) or Control-click (Windows), then use Command+Option+Op-

Sibelius ManuScript Language Tutorial

Control+Left Arrow (Windows) to align all of the selected controls with the left-hand edge of the left-most control, or Command+Up

Arrow (Mac) or Control+Up Arrow (Windows) to align all of the selected controls with the top edge of the top-most control.

tion+Down Arrow (Mac) or Control+Alt+Shift+Down Arrow (Windows) to space the controls evenly in the distance between the top

edge of the top-most and the bottom edge of the bottom-most controls, or Command+Option+Option+Left Arrow (Mac) or Control+Alt+Shift+Left Arrow (Windows) to space the controls evenly in the distance between the left-hand edge of the left-most and the

right-hand edge of the right-most controls. Once controls are spaced evenly , you can increase or decrease the spac e between them proportionally by typing Command+Option+Option+Up, Down, Right, Left Arrow keys (Mac) or Control+Alt+Shift+Up, Down, Right,

Left Arrow keys (Windows) as appropriate.

20

Page 26

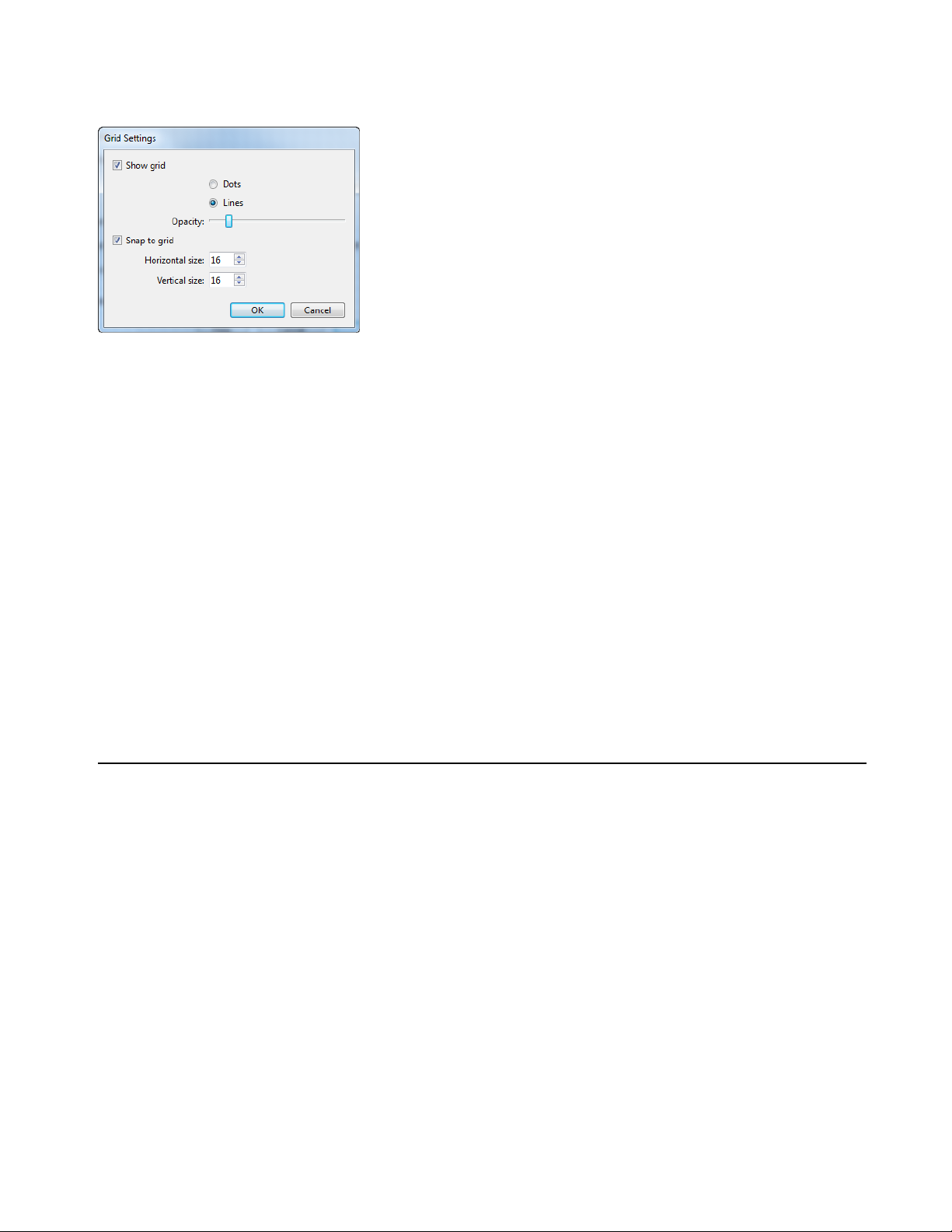

You can optionally display a grid to aid with alignment. Right-click on a blank part of the dialog and choose Grid from the context menu

to see a dialog with settings for the grid:

Grid Settings dialog

Switch on Show grid to show the grid in the editor. Choose between Dots or Lines, and specify the Opacity of the grid display by adjusting the slider. Switch on Snap to grid to enable control snapping as you drag them with the mouse. Although a control that you nudge

with the keyboard will not snap to the grid, one side of its selection outline will flash when it comes into alignment wit h the grid in either

the horizontal or vertical directions.

Undo and Redo

You can undo and redo everything you have done while editing a dialog using Command+Z (Mac) or Control+Z (Windows) to undo

and Command+Y (Mac) or Control+Y (Windows) to redo.

Testing the Dialog

To test the dialog within the editor, right-click a blank part of the dialog and choose Test from the context menu, or type the shortcut

Command+T (Mac) or Control+T (W indows). To fini sh testing and ret urn to the editor, press Esc or click a ny control whose pr operties

are set to close the dialog (e.g. an

OK or Cancel button, if you have created one).

Saving Changes

To save the changes to the dialog, click the close button in the dialog’s title bar. If there are any unsaved changes, Sibelius prompts you

to save the changes.

Set Creation Order

If you have done any programming in other languages that allow you to edit dialogs, you will probably be familiar with the concept of

tab order, which refers to the order in which controls are given the focus when the user repeatedly hits the Tab key to cycle through

them. ManuScript has a similar concept called cr eation or der , so named becau se the orde r in whic h the control s in a dialog are created

affects not only the tab order but also some other subtle things (including radio button grouping—see

Radio Buttons).

Sibelius ManuScript Language Tutorial

21

Page 27

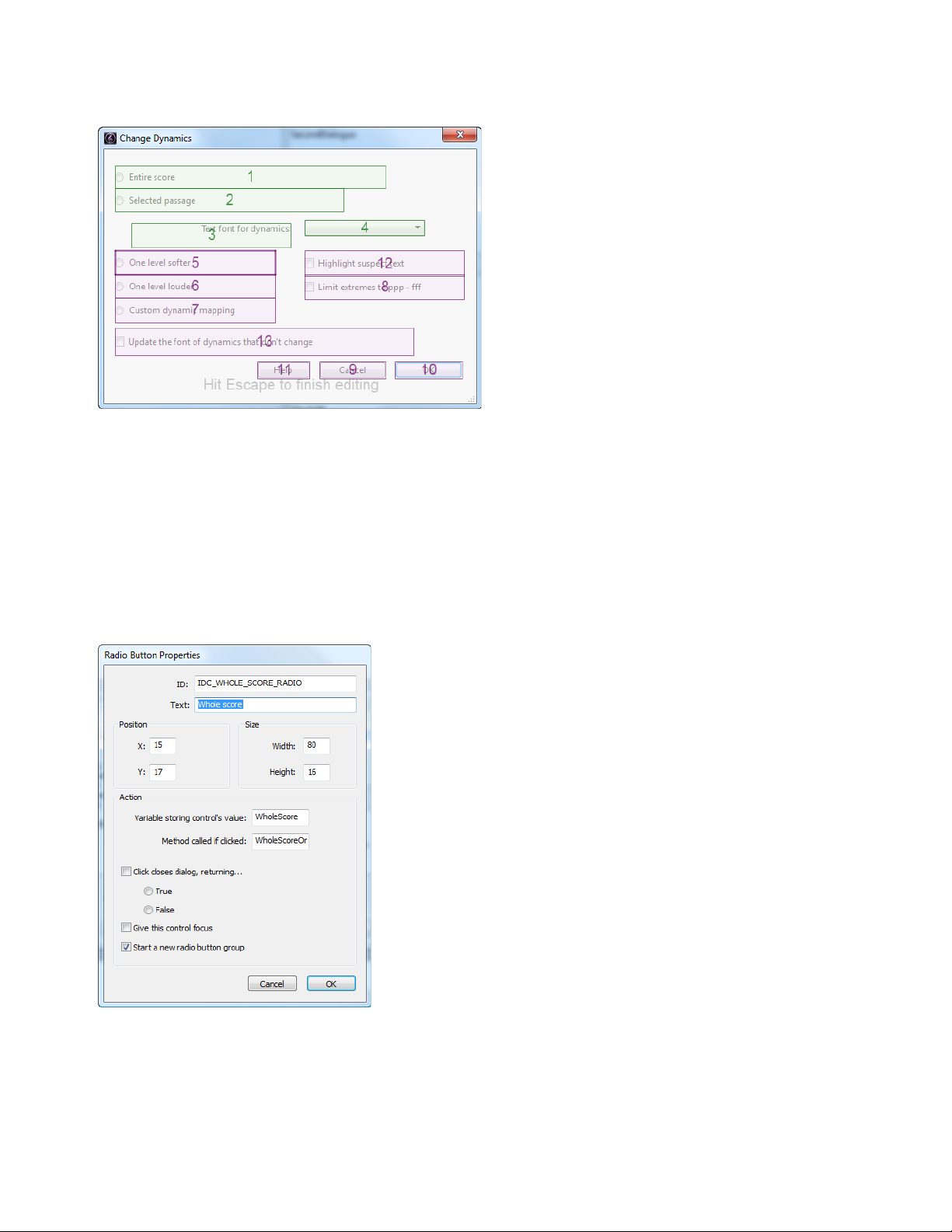

To set the creation order of controls in your plug-in’s dialog, right-click on a blank part of the dialog and choose Set Creation Order

from the context menu. A special display appears overlaid on the controls in your dialog, like this:

Plug-in dialog with creation order overlay

To set the creation order, simply click on each control in order. If you make a mistake, press Command (Mac) or Control (Window s)

and click on the last control whose order is correct to restart the sequence from that point, then release Command (Mac) or Control (Windows) and resume clicking on the remaining controls. Once you’re done, press Esc to finish editing the creation order.

Control Properties

Every control that you create also has a Properties dialog, which can be accessed by double-clicking a selected control, by right-clicking

and choosing Properties from the context menu, or by pressing Command+Return (Mac) or Control+Return (Windows). The dialog for

a radio button control, for example, is shown below:

Radio Button Properties dialog

Sibelius ManuScript Language Tutorial

22

Page 28

With a control selected, the properties window varies depending on the type of the control, but most of the options are common to all

controls, and these are as follows:

• ID: an internal string that identifies the control; Sibelius generates this for you automatically, but you can change if you like.

• Text: the text appearing in the control.

• Position (X, Y): where the control appears in the dialog, in coordinates relative to the top left-hand corner.

• Size (width, height): the size of the control.

• V ariable storing control’ s value: the ManuScript Data variable that will correspond to the value of this control when the plug-in is run.

• Method called when clicked: the ManuScript method that should be called whenever the user clicks on this control (leave blank if you

don’t need to know about users clicking on the control).

• Click closes dialog: select this option if you want the dialog to be closed whenever the user clicks on this control. The additional options Returning True / False specify the value that the

Sibelius.ShowDialog method should return when the window is closed

in this way.

• Give this control focus: select this option if the “input focus” should be given to this control when the dialog is opened (such as

whether this should be the control to which the user’s keyboard applies when the dialog is opene d). This is mainly useful for editable

text controls.

Other options vary according to the type of control selected.

Combo Boxes and List Boxes

Combo boxes and list boxes have an additional property; you can set a variable from which the control’s list of values should be taken.

Like the value storing the control’s current value, this should be a global Data variable. However, in this instance they have a rather special format, to specify a list of strings rather than simply a single string. Look at the variable

for an example – it looks like this:

_ComboItems

{

"1"

"2"

"3"

"4"

"1 and 3"

"2 and 4"

}

_ComboItems in Add String Fingering

List boxes have one further property, which is to determine whether they should allow a single selection or multiple selections. The return value from a combo box or a single-selection list box is a single string. If a list box is set to allow multiple selections, the selection

is returned as an array of strings.

Radio Buttons

Radio buttons also have an additional property that allows one to specify groups of radio buttons in plug-in dialogs. When the user clicks

on a radio button in a group, only the other radio buttons belonging to that groups are deselected; any others in the di alog are left as they

are. This is extremely useful for more complicated dialogs.