Page 1

CLASSIC

MOVIE

HOUSES

G O D I G I T A L

BY ANDREAS FUCHS

DCI or D I E

he time has come. The Capri Theatre needs to get

digital.” Continuously operating since 1941—when the

‘T

was still known as The Clover—the Capri Community Film

Society, its nonprot operator since 1983, was faced with the

daunting task to go “DCI or DIE.” (We gratefully—and with

permission—lifted those catchy words for our headline.) Noting

“the studios made us do it,” cinema director Martin McCaffery

launched a Kickstarter campaign in April, ultimately raising more

than the $80,000 requested, in addition to “a generous grant”

from The Daniel Foundation of Birmingham that provided the

rst $25,000. DCI it is.

rst neighborhood theatre in Montgomery, Alabama,

the Capri,

nee Clover, 1958

reel life,

before digital

While certainly lucky to have such good friends, the

Capri (www.capritheatre.org) is not alone in overcoming the

challenges of digital conversion and in hoping for good things

to come with it. Putting it into perspective, that amount

of money is “more than we spent on 35mm in 30 years,”

McCaffery says in his video pitch. “And it is also more than

we had in ticket sales last year.” Other successful Kickstarters

such as the Catlow (http://bit.ly/fji1012catlow), Patio, Harbor

and Rose theatres as well as Lyric Cinema Café (http://bit.ly/

fji1112kickstarter) have already been proled in these pages.

And McCaffery credits the Crescent Theatre in Mobile, Ala.

as his inspiration, along with the discussions at the Sundance

DCI or Die! Kickstarter

Arthouse Convergence last January. “After that, I just

decided we had nothing to lose, so why not give it a try?”

How are independents dealing with this seismic

change? In the rst of a two-part series, we examine

the work of passionate individuals and groups of people

not only at the Capri but in Tampa, Florida (www.

tampatheatre.org), and Berkeley Springs, West Virginia

(www.starwv.com). They will be joined next month by

equally good folks from Stamford, Connecticut (www.

avontheatre.org), as well as theatres in Santa Monica and

Hollywood, Calif. (www.americancinematheque.com), and

Lichtervelde, Belgium (www.cinemadekeizer.be). All of

them exclusively share with Film Journal International their

thoughts on timing, how they nanced the conversion,

specic challenges they encountered due to their unique

surroundings—and, of course, how programming

philosophies are being impacted. As McCaffery says,

“We’re hoping digital will allow us to expand our

programming.”

SayS CEO JOhn BEll On thE fundraiSing

Campaign fOr digital COnvErSiOn Of thE

nOnprOfit tampa thEatrE, “WE ElECtEd

tO gO With a mOrE graSSrOOtS Campaign.

m

OSt pEOplE gavE uS $10 Or $50 giftS, But

WE raiSEd aBOut $104,000.”

ll of our exemplary movie houses have been around for a

A

long, long time. At 72 years, the Capri is the youngest in

the bunch (barely, by one year). The Aero Theatre opened in

1940 and is operated by the American Cinematheque, which

also runs the Egyptian in Hollywood. Exhibitor-showman Sid

Grauman launched the exotic landmark in 1922, four years

after the Million Dollar Theatre in downtown Los Angeles

and ve years before his world-famous Chinese Theatre down

the boulevard. The Avon was part of that magical movie year

1939 and our small-town wonders in Berkeley Springs and

Lichtervelde were established in 1928 and 1924, respectively.

“I have to remind people that the Tampa Theatre was

built before sound was even invented,” laughs John Bell, the

president and CEO of the 1926 atmospheric movie palace

that the MPAA recently placed on its list of “the world’s best”

(www.thecredits.org/2013/05/ten-of-the-worlds-best-movietheaters). “Since lm is our core business, we were well aware

for several years that digital cinema was coming,” he reassures.

“In July 2012, however, we realized it wasn’t just coming but

that it was here. While there wasn’t any one distributor that

went on record saying they would stop distributing lm prints

to the Tampa Theatre in 2013, that was the message we were

hearing nonetheless. Part of why we had been waiting was our

hope that the digital conversion would be like plasma TVs,” he

laughs. “You know, prices coming way, way down after the rst

ones had come out. Unfortunately that has not been the case.”

The accelerated timing put the nonprot Tampa Theatre

SEPTEMBER 201346 WWW.FILMJOURNAL.COM WWW.FILMJOURNAL.COM 47SEPTEMBER 2013

Page 2

in what Bell calls an odd position. “We were already planning

for major upgrades to the building, electrical and HVAC work,

seating… Digital cinema was always a part of that larger,

multi-million-dollar package that requires nding substantial

donors to become successful. We realized we had to move up

the timetable on digital and that we needed to bring it out of

the main campaign.” Instead of asking major donor prospects

for less money than they might actually be willing and able to

gift in order to secure the Tampa’s future overall, “for digital

we elected to go with a more grassroots campaign,” he says.

“Most people gave us $10 or $50 gifts, but we raised about

$104,000 that way and were able to approach a friendly local

bank for a bridge loan on the rest because we had to go digital

now.” Bell is convinced that “without the great support that

the Tampa received from the community, we would not have

been able to get bank nancing.”

What about virtual-print-fee support? Every theatre in this

survey responded that to take that option was not an option

for them at all. “I know VPFs make a lot of sense for some

folks,” Bell reasons, “but in our business model, such a deal

has the unintended consequence that you lose a bit of control,

right? We prefer more of an in-house curatorial approach in

how we select and book our lms. It was important for us to

maintain that exibility and control.”

As part of the technology selection process, the Tampa

team sent out requests for proposals. “We started getting

bids at the same time as we were raising money constantly,”

he elaborates about using the website, e-mail blasts and

dedicated mailings to members of the Tampa Theatre. Because

of “specic site challenges due to the historical structure

[including] a pretty steep angle from the booth to our screen

and acoustic issues”—additional upgrades were to be done as

part of the $150,000 project overall.

The Capri as well has bigger plans, and cinema director

McCaffery would also have preferred to put digital off until

“we restore and rehabilitate the building,” he admits. “We

knew the day of digital was coming, but we were stalling as

long as we could. Frankly, I thought the studios would end

their 35mm distribution by the end of 2013, but that the indie

distribs would hold on to lm prints as long as possible. In

retrospect, that didn’t make sense. The indies were the rst

to start losing 35mm because they had to have DCPs for their

lms that played in big-city multiplexes. They don’t have the

money to carry dual inventory, so more and more of their

lms were digital only. As I was missing out on several lms, I

knew we would have to add digital sooner than I hoped.”

At press time, the Capri anticipates its digital debut for the

fall, for which Boston Light & Sound (www.blsi.com), who also

worked wonders on the Tampa Theatre, will install a Christie

projector. “We are now working on all of the coordination

that will be needed, such as construction, electricity, HVAC,

curtains,” McCaffery explains. “The projection booth is barely

big enough for our 35mm projectors, so guring out where to

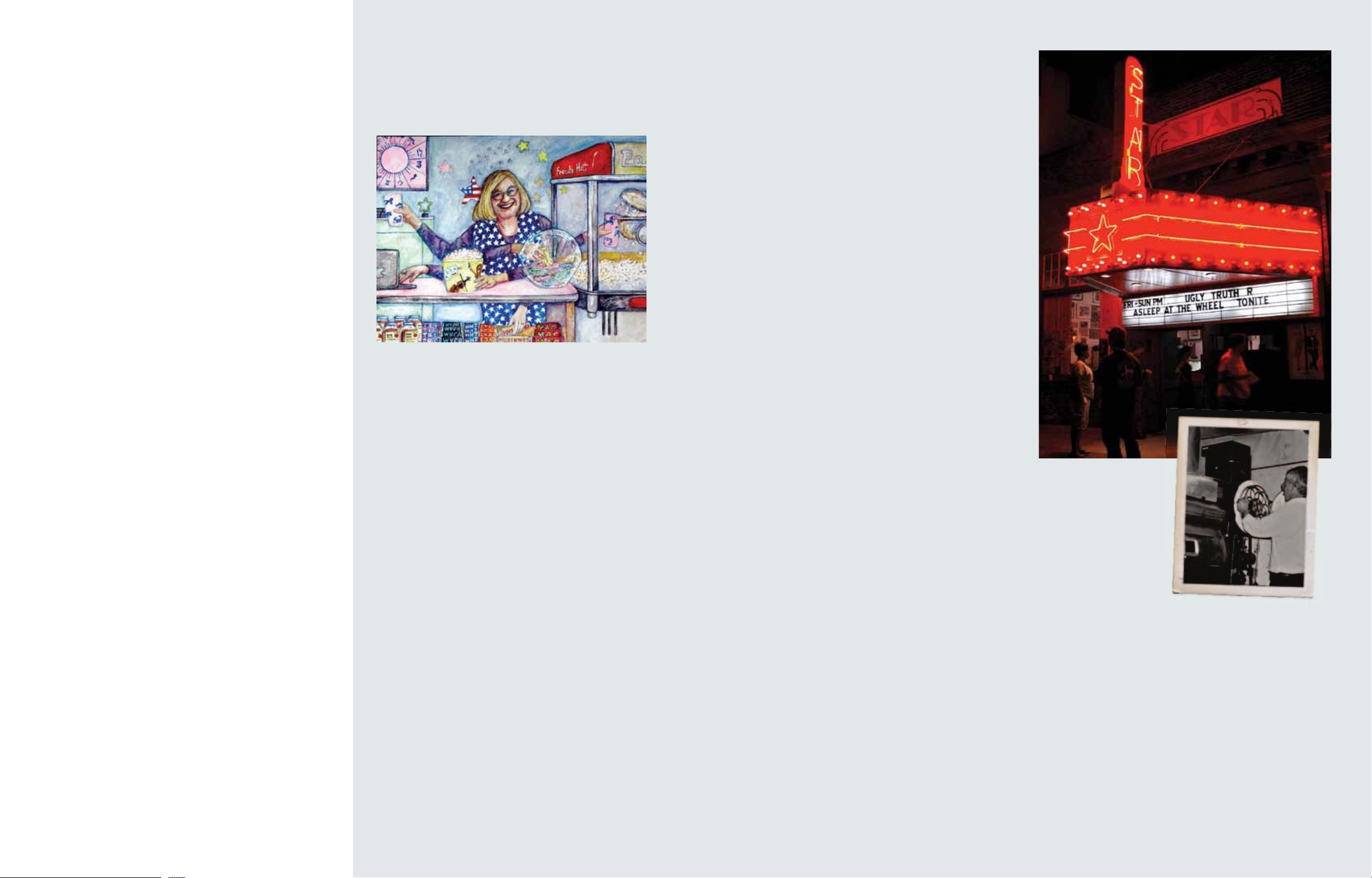

The Day Our STar WenT DigiTal

by Jeanne MOzier

OWner anD POPcOrn eMPreSS,

Tar TheaTre

S

t was a shock when we

received the rst letter.

Twentieth Century Fox

I

announced they would offer

no more movies on 35mm

lm by the end of 2013. My

husband, Jack Soronen, and

I had to make a decision—a

very expensive decision.

The Star Theatre is a

nearly 100-year-old movie

house that is the main night-

life in the small historic spa

town of Berkeley Springs,

West Virginia. It is both the

shining light of weekend

nights with its 1949 marquee,

and an important economic

factor in a town where tour-

ism is a major industry. We

had to go digital or close. We

knew we couldn’t abandon

our town to no movies and

an economic hole, so we

made the only decision pos-

sible.

The Star is a true mom-

and-pop operation. Jack and I

are the sole employees along

with various volunteers and

family who ll in occasional

gaps. It’s our year-round

weekend job. Jack takes tick-

ets, runs the projectors and

keeps everything functioning.

I book movies and make the

best popcorn in four states.

We both sweep, mop and

vacuum. We’ve owned and

operated the Star since 1977

and are only the third own-

ers since movies were rst

shown there in 1928.

The abstract decision

was easy to make: Digital or

die. It was the high cost of the

equipment that gave us pause.

We calculated it would cost

virtually every dime in prot

we’d made since we opened,

and about twice what we paid

for the business and building

originally. The movie industry

offered no nancial assistance

and we interpreted the VPF

systems as something akin to

serfdom. The Star is our pri-

vate business, so we did not

think public fundraising was

appropriate. In the end,

we gured we were commit-

ting to work until we were

90 to earn it all back.

Jack set off in May 2012 to

the Mid-Atlantic NATO confer-

ence in northern Virginia to

see what he could learn about

the digital world. Arriving early,

he met up with the folks from

Ballantyne-Strong in Omaha,

Nebraska. It was love at rst

sight and they provided us with

the newest used system we’ve

ever seen: an NEC NC2000C

projector using a GDC SX-

2001A server.

Once we decided to go

digital, we made other upgrades

as well. Jack wanted to be sure

that people would see changes

beyond what a digital image

brings to the screen. We bought

an MDI screen and the Star got a

new coat of paint inside and out.

There was no way around it. We

would have to raise prices.

Even with new, higher prices,

the Star remains a bargain. Adult

tickets increased from $3.75 to

$4.50. Not one person has ever

mentioned the higher ticket price.

The only reaction comes from

our city friends who laugh and

claim that we’re now approaching

1995 level.

Going digital was a chal-

lenging learning experience

for Jack, who has been the

projectionist since we opened.

Originally he used the two

carbon-rod Brenkert projec-

tors installed by the Alpine

chain which leased the theatre

in 1949. In 2002, when the last

American manufacturer of the

carbon rods stopped produc-

tion, we decided to upgrade to

a xenon bulb and platter system.

It was a major quality-of-life

improvement for Jack. No more

Cinema Paradiso. But also, no

more sweating in the projec-

tion booth through the whole

movie waiting to switch from

one projector to another, every

20 minutes or so, to replace the

rods which burned to provide

the light.

Jack gathered a posse of

four friends to help empty the

existing projection booth of the

2002 system and move in the

new equipment. He contracted

with our technical advisers and

suppliers at Cardinal Sound in

Elkridge, Maryland. A pair of

Cardinal technicians came to

Berkeley Springs and spent sev-

eral hours hooking up the digital

equipment, setting image and

sound. Jack was on the phone

with them all the next day as

they worked to adjust software.

Then came the digital opening

night and we held our collec-

tive breaths as Jack ipped the

switch on the server.

Our rst digital movie was

Twilight, Breaking Dawn Part 2.

We gured that audience would

be forgiving should there be a

crisis. There was none until the

following weekend with Lincoln.

We had booked the movie for an

additional day to accommodate

a group of seniors who wanted a

daytime showing. Unfortunately,

the digital key was set to expire

Sunday night and we did not

know enough to recognize that.

There we were with a hundred-

plus old folks patiently waiting

nearly an hour for this newfan-

gled technology to work. While

Jack spent the time frantically

on the phone with Deluxe and

Cardinal techs, I did the obvious:

I went on stage and blamed it all

on Disney.

With our calendar system

where a single movie shows for

a weekend, we have not noticed

any big change in how quickly

we can show a particular title.

One improvement for us is that

trailers are now easily available

in bulk. The digital system is

another step up in easing the

thE Star thEatrE

and JaCk SOrOnEn

job of the projectionist. No

more hauling heavy reels of

lms up and down narrow

steps, splicing and breaking

down reels for the platters.

No more breathing xenon

fumes. Once mastered, the

loading and showing of mov-

ies is much easier, which

makes it possible to train back-

up projectionists.

We’re excited about the

possibilities of digital. The

acoustics of the Star’s 325-seat

auditorium are exceptional and

have delighted performing musi-

cians and those who used it as

a recording studio. Someday we

hope to be streaming live opera

from Lincoln Center—or maybe

World Wide Wrestling.

For our audiences, it is

the crisp image and almost 3D

quality even on our 2D system

that impresses them the most.

Local patron Ken Troy says,

“The image is great and the

prices are still the best around.

But the most important part is

they didn’t change the popcorn

machine.”

Located in a brick building

on a main corner in town, the

Star Theatre is on the West

Virginia Historic Theater Trail.

Check www.starwv.com or call

304-258-1404 for what’s playing.

SEPTEMBER 201348 WWW.FILMJOURNAL.COM WWW.FILMJOURNAL.COM 49SEPTEMBER 2013

Page 3

put the digital equipment was a challenge. The new projector

will go in the empty space under the current booth and that

will require blowing a hole in the wall.”

On a positive note, that means the beloved classic

hardware can remain in place. “Our current projectors are

Simplex XLs, which we bought used in 1994,” he further

notes. “They are probably from the 1960s. We have a 16mm

Hortson that we bought used from a DC porno theatre in

1986, likely from the late 1970s. The Capri’s 1941 wiring is the

other challenge. Being in the South, heat and humidity is always

a problem, especially in a building that doesn’t have efcient

HVAC. We will have a separate AC for the digital projector.

We will also be installing new curtains and masking, as well as

some additions to the sound system. Our sound processor is a

Dolby CP650 bought new in 2002.”

t the Tampa Theatre, some $30,000 of the budget was

A

devoted to improving sound, John Bell estimates. Prior

to installing the upgraded and “very well-designed” screen

speaker arrays with narrow dispersion angles that were

“literally aligned with laser beams,” there were problems, he

notes. “The muddiness of the olden days, especially in the

speech intelligibility spectrum, was caused by the sound from

behind the screen bouncing off this very ornate 1926 plaster

work. Now the sound is completely focused on the seats and

nothing directed at any of the walls.” On those very beautiful

walls, “the 24 surround speakers that we already had from a

5.1 upgrade ten years prior were sufcient enough” to remain

in place “after BL&S tuned them up, with a lot of queuing and

balancing.” (By the way, the Tampa’s three-manual, 14-rank

Mighty Wurlitzer theatre pipe organ doesn’t need any of that.)

“The new Datasat processor is great,” Bell says, praising

its manifold options of auxiliary input. “That capability is

important to us, because we have a custom input panel to

accommodate all kinds of different formats that our guests

bring in when we host lm festivals here.” On the visual side

as well, “you plug in what you have. We select an input and,

boom, it magically shoots through the d-cinema projector and

goes up to the screen. All the while being scaled up so that it

looks the best it can possibly look.”

“For us, it was never an either/or decision, but about

adding d-cinema technology rather than converting,” Bell

continues. “We have the space to keep our two 35mm

projectors—and the platters we used for rst-run product—

in place for showing archival prints in the future.” Where then

did the Christie CP-2220 projector and Doremi servers go?

“I wouldn’t say the Tampa Theatre was designed for digital

projection,” he chuckles, “but fortunately, we have three

projector ports with one sitting right in the middle that was

not in use.” The 24-degree angle—with a 105-foot throw to a

24-foot-wide screen that lls the entire proscenium—was not

quite as convenient. “There is not a digital-cinema projector

on this planet that can function properly—and remain within

warranty terms—at an angle greater than 20 degrees. After

some head-scratching, the design team gured out to go with

a series of optical mirrors bouncing the image up and out in

a periscopic system. It’s quite ingenious, actually, and works

quite beautifully.” To optimize the picture quality, the mirror

array system had to be prevented from vibrating, so as not to

cause jittery images on the screen. BL&S fabricated a projector

frame, which was afxed tightly to the projector.

The alternative to those mirrors would have been to

construct an unwanted new booth in the mezzanine of the

historic auditorium. “That was not going to happen. Finding

an engineering solution was a great sigh of relief for us,” Bell

says, giving due credit. “Our stage manager and projectionist

worked it all out with Boston Light & Sound. I can’t sing

their praises enough. They offered the most detailed design

itineration and planning. They weren’t the highest and they

weren’t the lowest bid, but I knew we were going to end up

with a really good system. The installation went just great.

And the quality of the image is so crisp and pure… Frankly, all

we’ve gotten since debuting digital are rave reviews about the

beautiful picture and the awesome sound.”

aybe it is because Martin McCaffery hasn’t had his digital

M

systems installed yet at the Capri, but his perspective is a

little more astringent: “I am hoping for a revelation that digital

causes some horrible disease, but your audience probably isn’t

interested,” he jokes. In turn, John Bell admits to being “one of

the lm purists, honestly, that lamented the demise of 35mm…

but I have become a convert. I think it sucks that it costs so

much for theatres having to install all the equipment that…

primarily benets the distributors. But, at the Tampa Theatre,

it has also brought a huge increase in the quality of the

experience for our audience.” To him, it all “still comes down

to what you put up on the screen, the stories that lmmakers

tell us. Going digital is also about choices, so that we could

program what we wanted to show without being blocked from

new opportunities simply because of a technology we didn’t

have. At the end of the day, technology is the means. Going

to the movie theatre is still about the lms we show and how

good they are. It’s all about the experience for the audience.”

For more about lm versus digital choices and experiences of

movie houses and their audiences, check in again next month.

SEPTEMBER 201350 WWW.FILMJOURNAL.COM

Loading...

Loading...