Page 1

Page 2

Contents

Microphone Design . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3

Microphone Types . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3

Capsule Size . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4

The Backplate . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5

Patterns . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6

Top Address vs. Side Address Designs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8

Microphone Electronics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8

Manufacturing Standards . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .10

Caring for Microphones . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .13

Shock Protection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .13

Pop Filters and Windscreens . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .13

Temperature and Humidity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .13

Cleaning and Storage . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14

Basic Miking Concepts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .15

Close-Miking vs. Distance-Miking Techniques . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .15

Large Capsules vs. Medium Capsules . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16

Dealing with Unwanted Low-Frequencies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16

The Mic Preamp . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16

The Recording Environment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17

Phasing Issues with Multiple Microphones . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .18

Stereo Miking Techniques . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .21

X-Y . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .21

Blumlein . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .22

ORTF . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .22

Mid-Side . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .22

Spaced Omni . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .23

Decca Tree . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .23

Specific Miking Applications . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .25

Vocals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .25

Acoustic Guitar . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .26

Electric Guitar . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .27

Grand Piano . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .27

Drums . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .28

The M-Audio Family of Microphones . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .33

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

oubleshooting

r

T

Contact Information . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .35

Tips

34

Page 3

Chapter 1

output signal

voltage

coil

fixed magnet

+

-

diaphragm

output signal

voltage

coil

fixed magnet

+

-

metal ribbon diaphragm

fixed magnet

output signal voltage

+

-

diaphragm

Choosing & Using Microphones

Microphone Design

While all micr

ophones are designed for the common purpose of converting variations in sound

pressure to electronic signals, different technologies have their benefits depending upon the

a

pplication.This chapter examines the merits of different design types, capsule sizes, polar patterns,

electronics and more.

Microphone Types

The three main types of microphones in common use today are dynamic, ribbon and condenser.

Each has unique attributes appropriate for different applications.

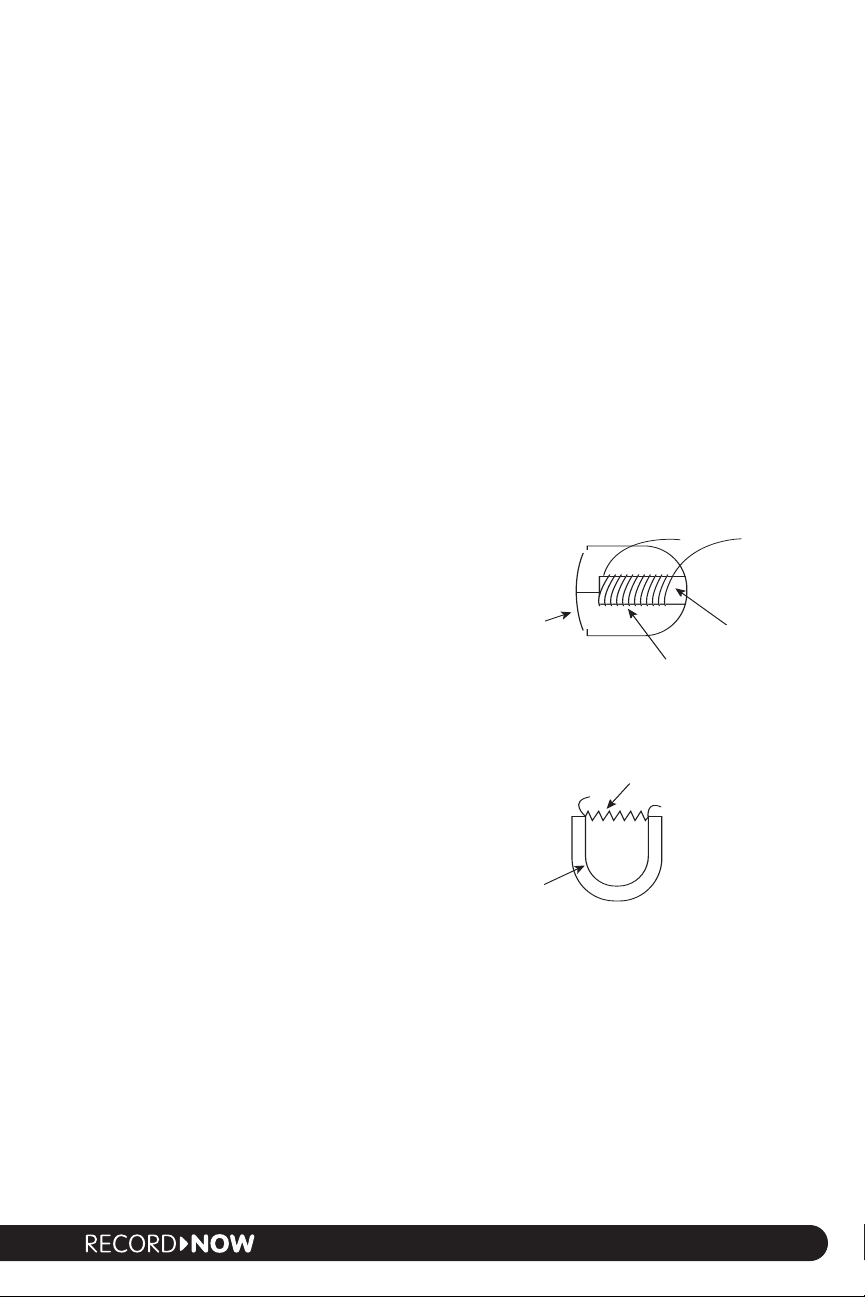

Dynamic microphones

The dynamic or moving-coil microphone is the easiest to understand. It is the classic technology

taught in grade school as the inverse of the common speaker. A plastic or metal diaphragm is

attached to a copper coil that is, in turn, suspended in a magnetic field.Sound pressure waves hitting

the diaphragm cause it to move, and with it, the coil within the magnetic field. The resulting

magnetic fluctuations translate to electrical fluctuations

generally corresponding to the physical fluctuations of the

original sound wave.

Due to the requirement of attaching the coil directly to the

diaphragm, dynamic diaphragms are thicker and, therefore, less

sensitive than the ribbon and condenser microphones

discussed shortly.These same design considerations also give

the ability to take the greatest amount of sound pressure

before distorting, as well as the greatest amount of physical

abuse. Dynamics are also the easiest and least expensive to

make. Dynamics also to tend to color the sound in the range of

about 5k to 10k, and start to sound thinner when more than

about a foot away from the source.

In dynamic mics, sound pressure moving the

diaphragm causes the attached voice coil to interact

with a magnetic field to produce an electric signal

For these reasons, dynamic mics are most often found in

the average stage situation. After all, live performance

environments are much more likely to subject mics to

torture such as high volume, sweat, the elements, shock

and being dropped. In the studio, dynamic mics are most

often used to close-mic drums due to the possibility of

wayward drum sticks. Large-diaphragm dynamics are often

used on kick drums due to high sound pressure levels and

low-frequency content.

Ribbon microphones

Ribbon mics are another form of dynamic microphone distinct from the moving-coil variety. A very

thin metal ribbon suspended between the poles of a powerful magnet moves in response to sound

waves, thus cutting through the magnetic field and inducing a flow of electrons. The resulting

low-voltage output is typically fed to a step-up transformer and sent down the mic cable. The

extreme thinness of the ribbon makes this type of mic the most sensitive, especially at very low

sound levels.They are most often used in close-miking situations and, because they are also the

most fragile and costly mic design, ribbons are typically reserved for very controlled conditions.

Like moving-coil dynamics, ribbon mics color the sound in a way that is often employed to warm

up brassy sounds. (Ribbons are a great choice for recording sax, for example.) They also tend to

In ribbon mics, sound waves cause a thin metal

ribbon to mov

e within a magnetic field to produce

a current

3

Page 4

have very low output, thereby requiring more electronic gaina factor that necessitates

small capsule

medium capsule

large capsule

20 20k10k 15k1k

20 20k10k 15k

1k

20 20k10k 15k1k

ultra -thin diaphragm

solid backplate

capacitance

output

signal

Choosing & Using Microphones

high

-quality preamp electronics in order to avoid noise.

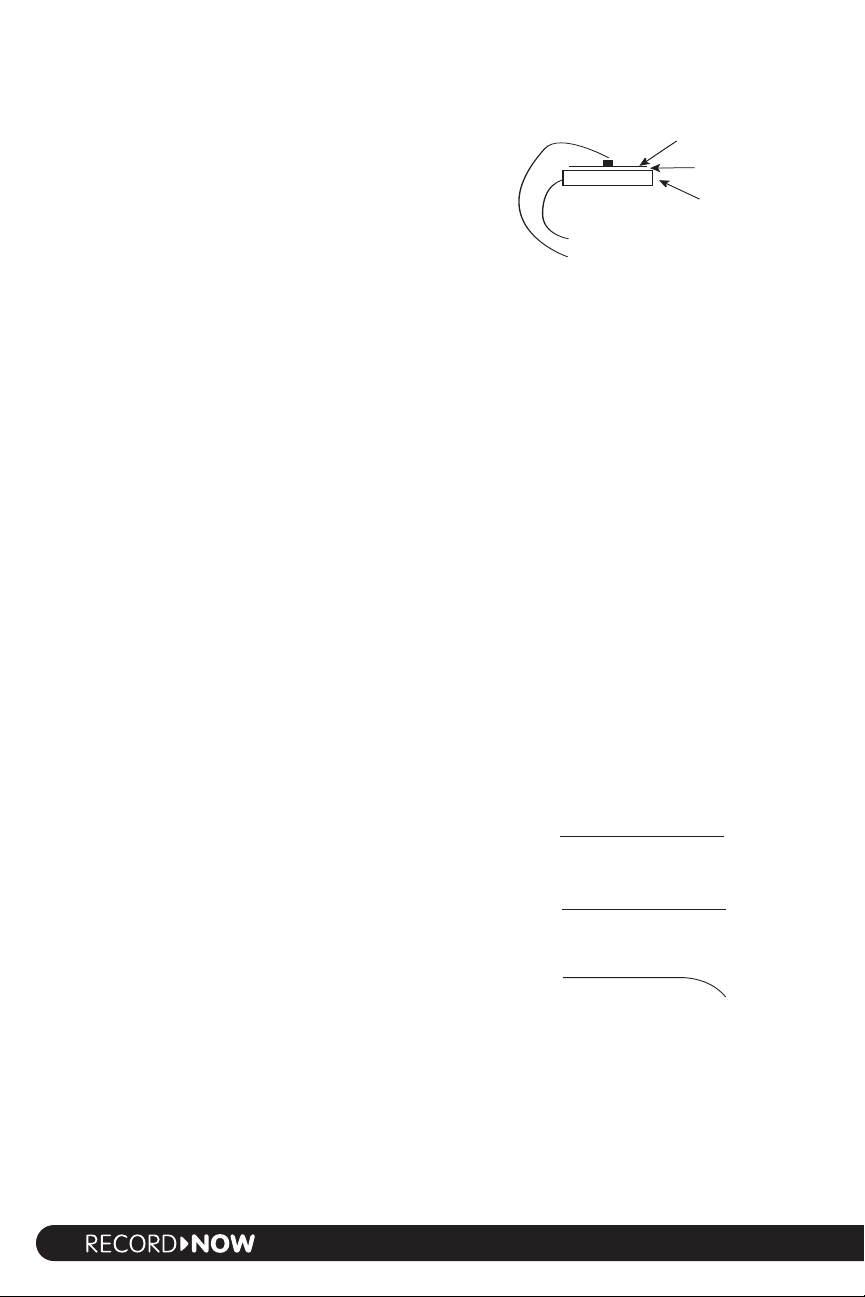

Condenser microphones

Condenser mics are the most common for studio use. A thin

electrically conductive diaphragm is suspended over a back plate,

forming a delicate flexible capacitor.When sound waves excite the

diaphragm, the distance between the diaphragm and back plate

changesand with it the capacitance. This capacitance change, in

turn, produces a voltage change. Associated circuitry converts

these variations in voltage to a signal that is sent to the preamp.

The power required by this design is serviced by the 48-volt

phantom power commonly found on preamps and mixer inputs.

The diaphragms of condenser microphones are made of extremely thin metal or metalized plastic

similar in thickness to kitchen plastic wrap.Their thinness makes condenser mics very accurate in

frequency response and extremely sensitive to transients, such as the initial crack of a drum being

struck. In addition to imparting the least sonic coloration of any microphone design, the sensitivity

of condensers extends much further from the source than other mics, thus allowing greater

flexibility.This greater sensitivity also provides the engineer with the option of picking up more the

room ambiencea factor that can add a great deal of realism to a recording.

Condensers are more delicate than moving-coil dynamics, yet much more resilient than ribbons.

Due to sensitivity to low-frequency handling noise and the delicacy of the diaphragm, condensers

are invariably used in conjunction with a shock mount, and often with the addition of a pop filter.

The sonic characteristics of condensers and the need for TLC make them more ideally suited for

studio recording. That is not to say that condensers cant be used for so me tas ks on stage

just that the environment should be controlled, such as in a professional show where cables

are secured, mics are shock-mounted against vibration, and the stage is restricted to

professional personnel.

In condenser mics, sound waves hitting

the diaphragm change the capacitance

in the field between the charged

diaphragm and backplate

Since condenser construction technology is much more labor-intensive and sophisticated

compared to that of dynamics, good quality condensers tend to cost comparatively more money.

Condensers are excellent choices for miking vocals, acoustic guitar, piano, orchestral instruments,

saxophone, percussion and sound effects.As condensers are the predominant type of microphone

for studio use, this guide will focus on condenser applications.

Capsule Size

The capsule incorporates the all-important diaphragm

assembly that translates sound pressure into an electric

signal. Condenser capsules come in three basi c sizes

small, medium and large. Generally speaking, frequency

response is a function of diaphragm size. Consider what

happens with speakers of different size. As woofers get

larger, they become more efficient at producing low

frequencies and less efficient at producing high frequencies.

In general, the same is true as the diameters of diaphragms

ease (with some ca

incr

Signal-to-noise ratio of the micr

more surface area that a diaphragm has, the greater its potential sensitivity to sound pressure and

onger the output signal.

the str

signa-to-noise ratios than do small ones.

veats well cover in a minute).

ophone as a whole generall

large dia

esult,

As a r

Without intervention, microphones tend to be

less linear as the diaphragm size increases

es in par

w

y o

phragms inher

t to diaphragm size.The

y exhibit m

entl

uch better

4

Page 5

Small Capsules

patented Disk Resonator boosts

high frequencies for full

frequency response

backplate

sound waves

3-micron evaporated gold

diaphragm

Choosing & Using Microphones

Small capsules ar

e typically those with diaphragm diameters of less than about 1/2. Categorically,

they are extremely accurate through the audible range of 20Hz to 20kHz. Their poor signal-tonoise ratio

, however, requires tricks with electronics and relegates small capsules to being most

useful for measurement rather than recording.

Medium Capsules

Medium capsules have diaphragms that are approximately 1/2 inch to 3/4 inch in diameter. Given

the right design and manufacturing, they typically exhibit flat frequency response from about 20 to

18k. Their diaphragms are also large enough to deliver signal-to-noise ratios acceptable for

professional use.

Large Capsules

Large capsules have diaphragms measuring 3/4 inch to one inch or even greater. Since larger

diaphragms yield better signal-to-noise ratios and greater sensitivity without having to induce

additional gain stages, bigger is typically considered better. Large capsules also tend to produce

greater low frequency detaila quality that cant be measured so much as heard. Large capsules

exhibit a proximity effect (most predominantly in the cardioid polar pattern), meaning that they

tend to sound more boomy as they get closer to the source. Large diaphragm M-Audio mics

include the Solaris, Luna and Nova.

The Diaphragm

The diaphragm is a critical component because it is

responsible for responding directly to sound waves. The

sensitivity of a mic is partially related to the thinness of its

diaphragm. (Recall that the comparatively thin diaphragm of

a condenser is largely what makes this type of mic much

more linear and sensitive to detail than a dynamic

moving-coil mic.)

Originally, condenser diaphragms were made from very thin, light metal such as nickel. As

technology evolved, it became possible to use synthetic materials such as mylar in order to create

tissue-thin membranes. Since condenser diaphragms need to conduct electricity, these synthetic

materials have a thin layer of gold applied to themthe thinner, the better. Most modern

condenser diaphragms are 6 to 12 microns in thickness. (A human hair is 40 microns in diameter.)

The M-Audio large capsule mic, the Solaris, employs a special ultra-thin 3-micron, highly resilient

mylar diaphragm. This delivers a degree of sensitivity unparalleled in the industry. (Physics dictates

that we employ 6-micron diaphragms in our Luna and Nova models.)

In the old days, manufacturers would apply the gold to the diaphragm using a process known as

sputtering.They would place the diaphragm substrate in a vacuum jar, atomize the gold, and then

blow the gold onto one side of the material.Todays vacuum chambers are far superior, allowing us

to use a refined technique where we place our ultra-thin mylar film in a complete vacuum and

evaporate the gold in such a way that it adheres uniformly to the mylar.The result is a diaphragm

that is we feel is the most sensitive in the industry.

Condenser diaphragms can be extremely sensitive to humidity and temperature changes. In order

to minimize that, we temper our diaphragms by baking them for specific times at specific

temperatures in order to insure maximum stability and performance.

The Backplate

In a condenser mic, the diaphragm is suspended over a backplate that carries one half of the

electrical charge that r

microphones were made of solid brass.In an effort to cut costs, most modern manufacturers make

the backplate out of injection-molded plastic and metalize them in some wa

esults in the ca

pacitance

The backplates of the best classic condenser

.

Critical listeners

.

y

5

Page 6

invariably prefer the sound of solid brass. Needless to say,

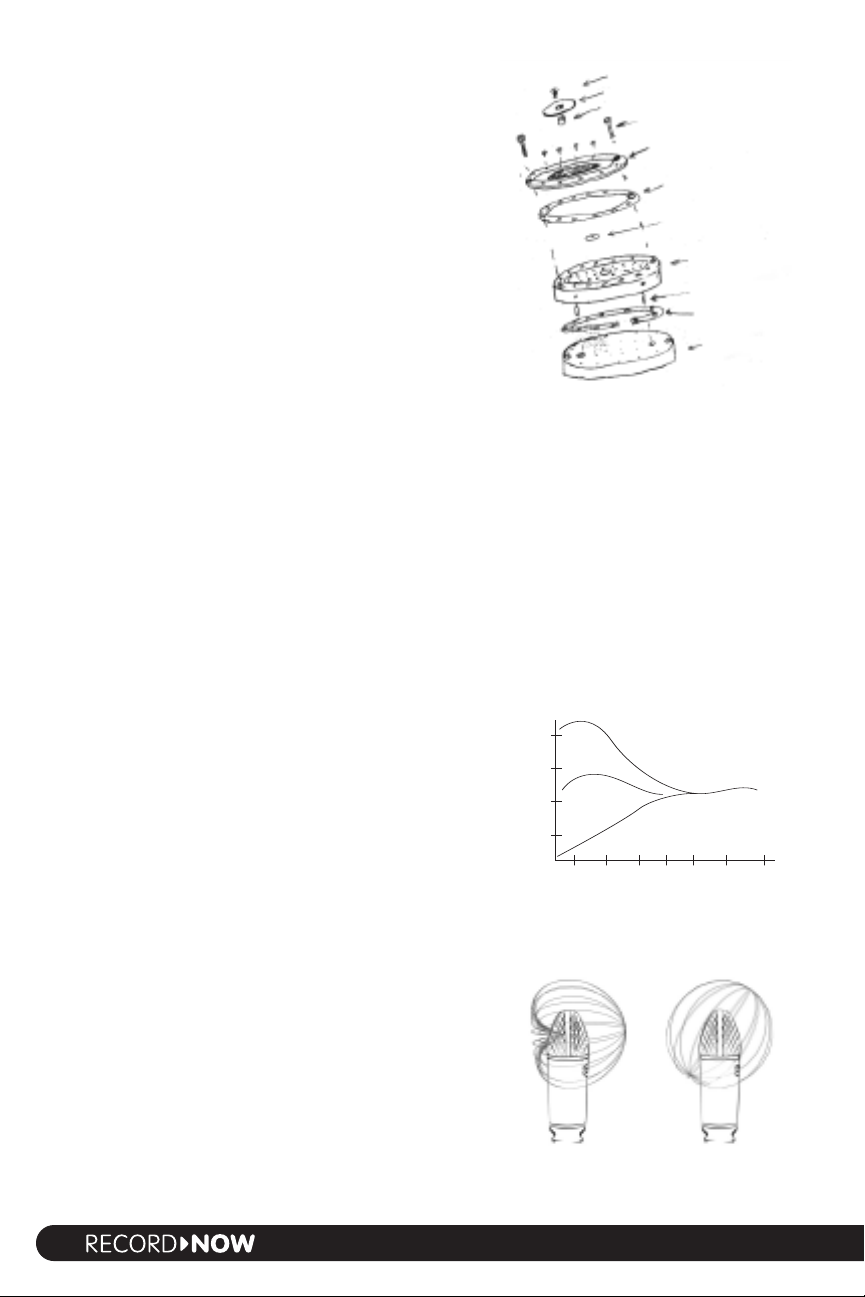

screw/contact

resonator disk

disk spacer

backplate screws

diaphragm

w/ mounting ring

ring spacer

center spacer

backplate

registration pins

backplate spacer

backplate base

Choosing & Using Microphones

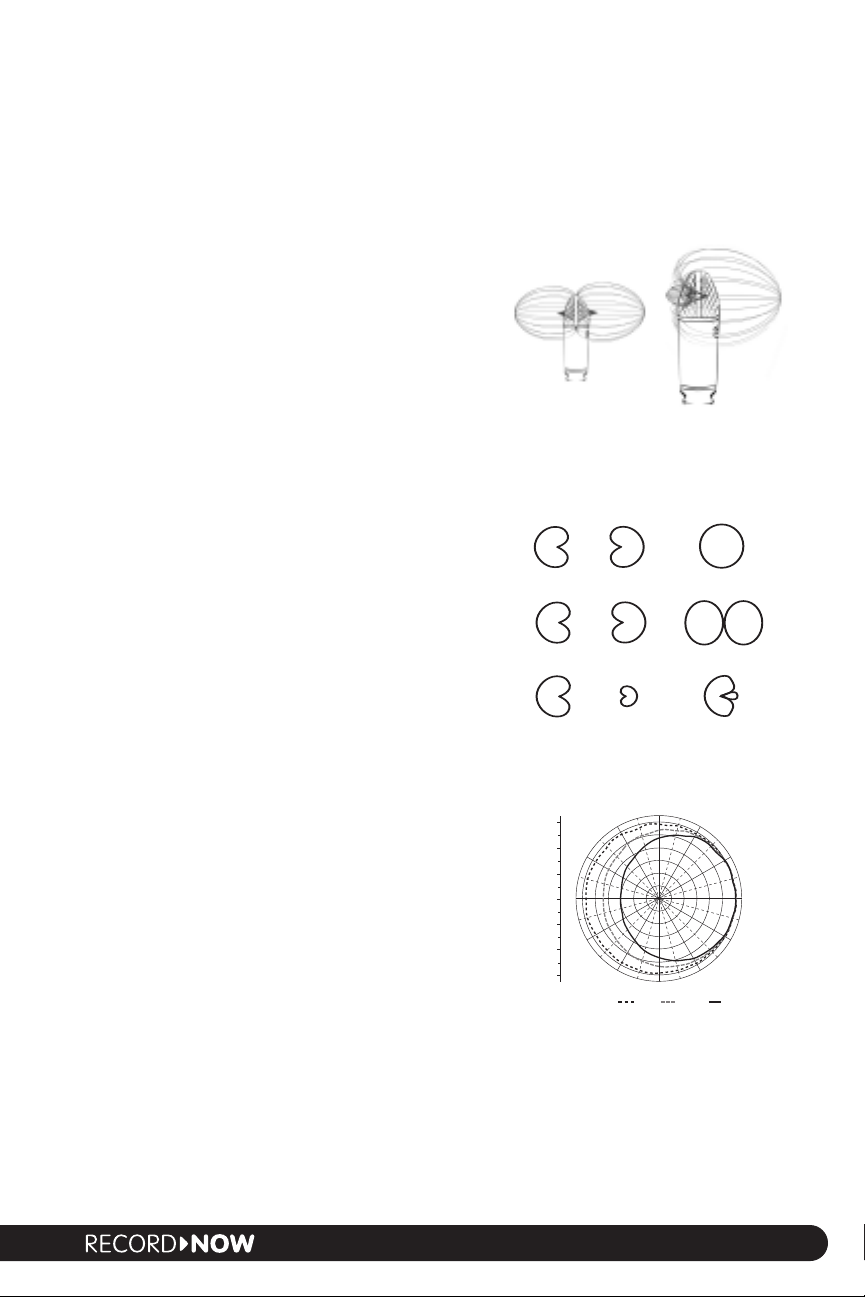

30 cm (1')

7.5 cm (3")

0.6 cm (1/4")

10

5

0

-5

--10

50 100 200 500 1k 2k 5k 10k

Frequency (Hz)

Relative level (dB)

w

e use solid brass backplates in all M-Audio mics.

The spacing betw

een the diaphragm and backplate is

critical. In order to avoid problems with barometric

pressure, the spacer ring has a break in order to allow air

to move freely between these two components. We

precision drill approximately 100 extremely fine holes in

the backplate, some going all the way through and some

only going partially through. This combination further

allows the appropriate amount of damping for the

diaphragm.We then lap the surface in order to ensure that

it is completely flat.This operation requires such precision

that we measure the results not with a ruler, but with

reflected light.

This level of precision is only possible due to modern

computer-controlled manufacturing techniques. The

important distinction is that these operations are

The major components of a large M-Audio condenser

capsule are a solid brass backplate and an ultra-thin

evaporated gold diaphragm

programmed and supervised by human technicians at

every step. All-in-all, there are several hundred precision operations that go into making each of

our solid-brass capsules.Thats more than the number involved the crafting of the average Martin

gu ita ran d were talking about something the size of a 50-cent piece.

Patterns

The term polar pattern is used to describe the response of a microphone to sound sources from

various directions. Each type of polar pattern has its own place and usage in the recording process.

Note that the classic polar pattern definitions apply most accurately when sounds hit the

microphone on axisthat is to say, approaching perpendicular to the planar surface of the

diaphragm. In general, microphones tend to become more directional in focus as frequencies

increase. Put another way, capsules are generally less sensitive to high frequencies off axis. This

phenomenon is typically less significant in medium capsules than in large capsules.

Cardioid pattern

The cardioid is the most common polar pattern found in

microphones. The name derives from this patterns

resemblance to a heart shape. Cardioids are unidirectional,

meaning that they pick up sound primarily from the front

of the capsule. The back of the capsule rejects sound,

allowing the engineer to isolate the signal source from

other performance elements or background noise. More

noticeable in larger capsule designs, cardioid patterns

typically exhibit a

proximity effecta boost in low-mid

frequencies as the proximity between the source and mic

increases. Proximity effect is also more prominent with

both larger capsules and lower frequencies.

Omni pattern

As the name implies, the omni-directional, or omni pattern,

picks up sounds equall

used to ca

thereby yielding a more open sound compared to the more

ocused quality of car

f

Foley sound effects, and realistic acoustic instruments

assuming that acoustic space of the r

is desirable.

pture room resonance along with the source,

dioid.

y w

ell fr

om all dir

ections.

Omni is great for vocal groups,

ding en

ecor

Omni is

onment

vir

The proximity effect causes increased output in

the low-mids as distances between the mic and

Cardoid patterns are most

sensitive on the side of

the capsule

source increase

Omni patterns are

sensitive to sound from all

directions

6

Page 7

Omni also exhibits significantly less proximity effect than cardioids. One result is that omnis are

Choosing & Using Microphones

+

=

-

=

-

=

30dB

30dB

20dB

10dB

0dB

10dB

2

0dB

1

20

90

60

30

0

330

300

270

240

210

180

150

100 Hz 1 kHz 10 kHz

some

what less sensitive to the movements of an animated vocalist. Another is that omnis tend to

have less need for EQ. As mentioned earlier,while omnis pick up 360 degrees of sound, they tend

to be mor

e directional as frequencies increase espec ially in larger capsules.

Figure 8 or bidirectional pattern

The figure 8 or bidirectional pattern is equally sensitive on the two opposing faces of the

microphone, yet rejects sound from the sides.This pattern does exhibit the proximity effect found

in cardioid patterns.

The figure 8 is excellent for capturing a duet or face-to-face

interviews with a single mic. The —40dB side rejection spec

also makes it great for isolating an instrument like a snare

from the rest of the drum kit.Figure 8 is also one of the key

components of M/S (mid-side) mikingan advanced stereo

recording technique well look at little later.

Super-cardioid pattern

The super-cardioid pattern exhibits an even narrower area of

sensitivity than the classic cardioid and is used for very

sonically focused recording. Super-cardioid is great for

zeroing in on that perfect sweet spot for instruments such

as piano or drum.This pattern is also ideal for live recording

sessions where isolation is important, including minimizing

bleed between a vocalist and their own instrument.

Single pattern vs. multi-pattern mics

The most inexpensive way to make a microphone is with a

single fixed pattern. Cardioids have openings in the backs of

the capsules that produce the physics of a unidirectional

pattern.This is an inherently fixed pattern design.An omnidirectional pickup pattern can be achieved by sealing the

back of the capsule, resulting in another fixed pattern.

Super-cardioids employ yet a different design. In most cases,

different back-end electronics are required for each pattern,

thus making it difficult to make interchangeable capsules.

The secret to building a single mic with multiple pickup

patterns is placing two cardioids back-to-back in

combination with various electronic tricks. An omnidirectional pattern occurs as the result of wiring two backto-back cardioids in phase with each other. Similarly, those

same two opposing cardioids wired out of phase yield a

figure 8 or bi-directional pattern*. Tweaks to the polarity

and output level result in a super-cardioid pattern. While

the presence of two high-quality diaphragm/backplate

assemblies incr

eases the cost, this solution provides the

best polar pattern performance and is still significantly less

expensive than buying multiple microphones in order to

have a choice of patterns at your disposal.

Figure 8 patterns are

sensitive on opposing sides

and exhibit strong rejection

at 90 degr

ees off axis

In multi-pattern microphones, two cardioids combine

in different ways to create other patterns

All microphones are less sensitive to high

frequencies off axis (omni example shown)

The super-cardioid

pattern has an even

greater focus of sensitivity

than cardioid

This approach to capsule design can be seen in the M-Audio Solaris. The Solaris employs an

opposing pair of the same diaphragm/backplate assemblies, thus allowing for the selection of

ultiple patterns via s

m

*Tip:

uninitiated. One side will sound strange to a vocalist or speaker who is simultaneously monitoring the mic

witches on the body of the mics.

Note that the out-of-phase wir

ing of the two sides of a f

e 8 capsule can play tr

igur

icks on the

7

Page 8

signal through headphones.That’s because one side of the mic is in phase with the performer (and therefore

top address

side address

Choosing & Using Microphones

reinforcing their perception of their own sound) while the other side is not. Addressing the in-phase side

while monitoring produces optimal monitoring results.

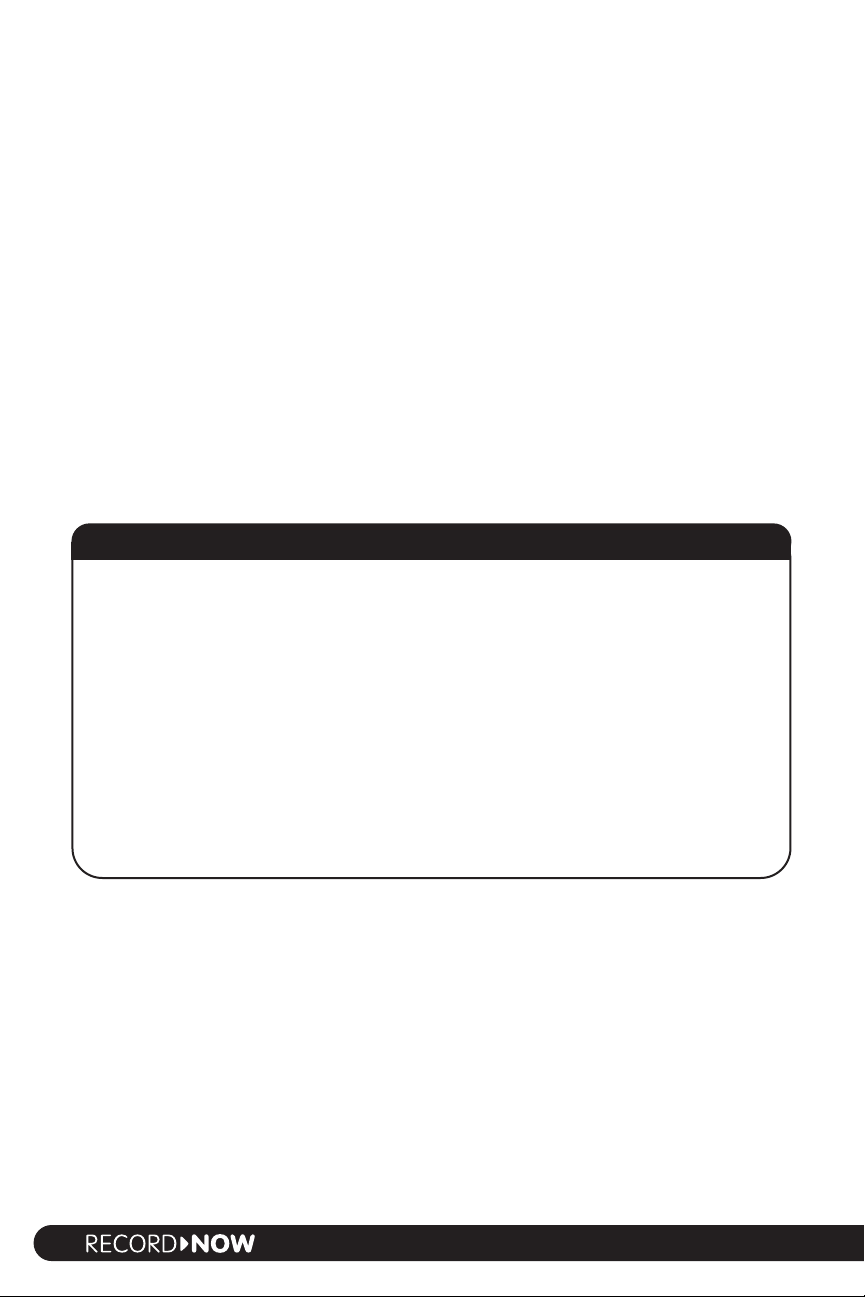

Top Address vs. Side Address Designs

The orientation of the diaphragm within the head of the

microphone determines if the microphone is addressed

from the top or the side. While not an absolute rule,

medium diaphragms are typically top-address while large

diaphragms are usually side-address. As you might

surmise from the previous discussion about design

considerations in attaining various polar patterns,

top-address mics typically have single pattern (at least

without physically changing the capsule) while sideaddress mics lend themselves to the possibility of back-toback capsules for switchable patterns. Note that on side-

Side addr

ess and top address

microphone designs

address mics, the side with the logo is usually the primary

or cardioid side.

Polar patterns aside, the practicality of side-address versus top-address designs also has to do with

logistics. Top-address microphones can usually fit into tighter spots than can side-address mics

(between drums, for example).This is yet another reason why pro engineers keep a variety of mics

in their arsenal.

Microphone Electronics

As weve seen, the microphone capsule is responsible for translating sound waves into electrical

signals. The other important part of the microphone is the head amp that conditions the sound

coming from the capsule so that it can be transmitted through a length of cable to an external

preamp or console.

Part of a head amps job is impedance conversion. (See A Word About Impedance for more

information on impedance.) The average line-matching transformer found in dynamic or ribbon

microphones has to convert on the order of several thousand ohms down to around 200 ohms

(or from half an ohm up to about 200 ohms).The condenser microphone presents a challenge of

a different magnitudeconverting a signal in the range of two billion ohms down to 200 ohms.This

incredible leap is beyond the scope of most output transformers, requiring the addition of a

specialized amplifier.

Impedance essentially describes the resistance in a circuit.Water flowing through a pipe is a good analogy to electrons

flowing through a wire. Lets say youve got a pump designed to put 100 pounds of pressure into an eight-inch pipe. If you

double the size of the pipe to 16 inches, you get half the pressure.While the pressure is now only 50 lbs,there is no damage

to the system. Halving the size of the pipe, on the other hand,yields twice the pressure that the system was designed for.

As a result, back-pressure affects the pump, further reducing its efficiency and increasing the potential of an explosion.

In terms of audio electronics, the pipe scenario is analagous to inputting the output from a 100-watt amp into 8-ohm

While using 16

ers.

speak

almost certainly blow up the amp.Thats why guitar amps designed to run into different speaker ratings often have

output transformers with 4-, 8- and 16-ohm taps which appropriately condition the output signal.

Guitar pickups and most dynamic mics are considered to be high impedance, meaning that they exhibit an

impedance of many thousands of ohms. Low-impedance signals are generally around 200 ohms or less.While the

high-impedance signals typically exhibit greater voltage, they can only be run through about 20 feet of cable before

they begin to lose high frequencies (or require additonal amplification in order not to). Low-impedance signals can

y be run m

typicall

-

uch fur

A Word About Impedance

ohm speak

ers is safe (though it reduces output power), switching to 4-ohm speakers will

ther without detriment.

8

Page 9

An output transformer and/or amplifier serves as a sort of translator and, in audio, we expect that

Choosing & Using Microphones

translation to be excellent in or

signal-to-noise ratio. Just as a professional language translator costs more than someone who just

took a f

ew years of foreign language in high-school, pro-quality output transformers and amplifiers

cost more than garden-variety ones. (A single transformer like those used in each channel of pro

consoles and outboard preamps can cost more than a complete inexpensive multi-channel mixer.)

Because the quality of this formidable translation is so critical in a professional-quality microphone,

all M-Audio mics employ high-quality Class A electronics in the head amp.

Tubes vs. solid state

The head amp can employ either tube electronics or less expensive solid state electronics. Before

we can effectively compare these two technologies, it is important to understand some

fundamental concepts.There are three main ways to measure how accurately an electronic circuit

passes soundfrequency response, total harmonic distortion (THD), and dynamic distortion.

Frequency response is the simplest to understand.Were simply talking about whether any highs or

lows are rolled off, or if any frequencies are cut or boosted to exhibit a non-linear frequency

response. Both tube and solid state electronics can be made without significant deficiencies in

frequency response.

Regarding THD,all electronics induce some kind of harmonic distortion, i.e. harmonics that are not

present in the original source. The nature of the harmonic distortion has more to do with the

associated circuitry than with tubes versus solid state.

components handle the entire signal waveform) tends to produce lower-order harmonics. On the

other hand,

separate devices) tend to produce higher-order harmonics. For this reason, Class A strikes most

people as sounding warmer. (All M-Audio mics employ Class A circuitry.)

That brings us to the third, more mysterious element called dynamic distortionsomething that

the industry didnt even have the technology to measure until quite recently. Dynamic distortion

refers to the accuracy or transparency over time,particularly critical regarding the transient at the

very beginning of a sound.Take the recording of a finger snap,for example.You can roll off the highs

and lows and/or introduce a good amount of distortion, yet still perceive the sound as a snapping

finger. Change the dynamic, however, and that snap can quickly lose its characteristic snap. In

general, accuracy in reproducing dynamics can make the difference between something sounding

full and three-dimensional or flat and two-dimensional.

Class B (where the positive and negative parts of the waveform are amplified by two

der to maintain frequency response, dynamic range, and

Class A circuitry (where all amplifying

Ironically, the discussion comes down to measuring things that dont matter and not measuring

things that do.Tubes measure greater in THD than solid state.While one can measure the difference

between .01 percent THD and .001 percent THD, its practically impossible to hear that difference.

On the other hand, while its difficult to measure dynamic distortion you can definitely hear it. Solid

state electronics exhibit many orders of magnitude more dynamic distortion than tubes.This is a

major reason why tube mics make recordings sound truer to life.

Tube electronics

Tubes cost more money to manufacture than comparable solid state electronic components. In fact,the

music industry is one of the few places where tubes have value in the face of more modern electronics.

Its a known fact that the average tube exhibits more inherent noise than solid state electronics. In

general, the smaller the tube, the better. Larger tubes have a greater propensity for being

microphonic, i.e. generating noise from mechanical movement of the internal parts. They also use

higher voltages that result in more heatand subsequently more noise. Most manufacturers tube

mics employ larger 12-volt tubes like the 12AX7an older tube design that is noisier when used

in microphone design.

TIP: One of the first things to be aware of is that not all products advertised as being tube mics employ

tubes in the main signal path.

a tube in the side-chain. (You can literally cut the tube out of the circuit on some models and the mic will

Some popular lo

w-cost mics utiliz

e less expensive solid-state circuitr

, putting

y

9

Page 10

still work.) The theory there is that the tube is used as a sort of processor to “warm” up the sound.The

Choosing & Using Microphones

reality is that these are still solid state mics masquerading as tube mics as cheaply as possible.

Because of the ph

ysics behind tube operation, tube mics have classically been subject to certain

physical restriction on the length of the cable between the microphone and power supply. As a

result, tube mics are normally restricted to cable lengths of about 15 feet. This has sometimes

required the use of solid state mics in scenarios such as drum overheads, remote recording or

orchestral recording.

Solid state electronics

Solid state microphones cost significantly less to manufacture than tube mics. As such, they are

found in the less expensive condenser mics on the market. (As stated earlier, some manufacturers

put low-quality tubes in their solid state mics like an effects circuit in order to advertise products

as being tube mics.)

In most solid state condensers, the key components are a series of op amps. All M-Audio mics employ FETs

(field effect transistors) instead. Logic says that op amps should be preferable because they have lower

measured amounts of THD. As discussed previously, while that difference in THD specs is measurable it is not

audible in well-executed microphone applications. Op amps, however, can have much more dynamic distortion

than FETssomething you can hear. Moreover, many designs use multiple op amps to do the job of one FET.

The difference is so profound that many people think that our solid state mics sound like most manufacturers

tube mics.

The Myth of Tube Warmth

There is a common myth that tubes are warmer sounding. It certainly can be said that cranking up a

tube amp will make an electric guitar sound warm, fat or distorted. That scenario, however, is one

in which distortion is desirable. On the other hand, distortion is the enemy of the engineer who is

attempting to record a sound source faithfully and realistically. Here, you want accuracy and transparency

rather than any coloration that might be described subjectively with a word like warmth. Fortunately,

there are many types of tubes and related circuitry that result in comparatively transparent sound.

It has also been said that tubes warm up digital recordings.This implies that there is something inherently

deficient in digital recording.While some purists will always make a case for analog over digital, the fact

is that a vast number of todays pro recordings are made with digital technology such as M-Audios

24-bit/96k Delta cards, USB and FireWire solutions.

Digital recording significantly increased the dynamic range, allowing us to better hear the dynamics of

recorded material. As a result, people were quick to label digital recording as cold, when using solid

state mics. When using a tube mic, everything suddenly sounded warmer by comparison. In actuality,

digital recording simply gave us the means of hearing differences we didnt hear before (such as how tube

output is dynamically truer than solid state).

Manufacturing Standards

e are quite a number of condenser microphones to choose from on the market today. Many

Ther

look pr

is that most companies engineer for profit.This guide was designed to help you think about whats

inside those shin

The story behind affordable matched pairs for stereo-miking

One of the factors that make a significant difference between amateur and professional recordings

is the use of stereo miking techniques. Pro engineers have long relied on matched pairs of

microphones to attain optimal results from stereo recording methods. Why a matched pair? You

wouldnt consider monitoring with a mismatched pair of speakers, right? Similarly, you want the left

and right mics hearing exactly the same way in order to achieve a balanced sound.

essional on the outside and, indeed, most will give you acceptable sound. However,the fact

of

y casesand m

uch of that comes do

wn to man

ufacturing standar

ds.

10

Page 11

From a technical perspective, the two mics need to be as identical as possible in frequency

Choosing & Using Microphones

r

esponse. A flat frequency response implies that there is no deviation in the output level versus

the input level at any and all frequencies across the audible spectrum. While a flat frequency

r

esponse is theoretically ideal, it is rarely achieved completely in any audio component. For

example, a mic might exhibit a 1dB boost at 1kHz and start rolling off 3dB per octave at 14kHz.A

perfectly matched pair would exhibit the same exact characteristics in both mics. Here again, such

an exacting match is rare.Therefore manufacturers each establish their own window of acceptable

deviation that they will certify as a being a matc hed p air there is no industry standard. (Please

note that we are actually talking about two different variables that are subject to interpretation and

little disclosurethe d eviation between two matched microphones of the same model, as well

as their deviation from the given manufacturers standard reference mic for that model.)

Even the most famous of classic microphones have exhibited disparities in frequency response of

6dB of more from unit to unit. In such circumstances, manufacturers must search through a batch

of mics to select a pair that is relatively close in responseon the order of 2dB up or down for a

total window of about 4dB. It is often necessary to place a special order (and pay surcharge as large

as 20 percent of normal cost) for such matched pairs. This is not the case with M-Audio

microphones. In order to pass inspection, all mics in our line must be within +/-1dB of not only

each other, but of our golden reference mic for that modelthe one we wont sell for any price.

Higher standards

M-Audio is able to offer incredibly high quality and tight tolerances at affordable prices for several

reasons.The first is that highly skilled technicians use the latest computer-controlled equipment for

manufacturing and testing.

The reality of todays marketplace is that most companies manufacture their products offshore in

order to be profitable. Many microphones on the market today are made in China or other

countries where labor is less expensive even the ones that say that they are made elsewhere. At

M-Audio, manufacturing is a hybrid operation. The designs all start in the USA, as do the

manufacturing of all critical path elements like transformers, capacitors, resistors and diaphragm

material.We then complete the machining and assembly in our own facility in Shanghai. In this way

we attain the best of both worldsquality and affordable pricing.

While were on the subject of standards, lets talk about the frequency response graphs that are

often included with microphones.These graphs illustrate the deviation between input and output

across the frequency spectrum. The ideal is to have as flat a line as possible indicating as little

deviation as possible. Such graphs can be misleading because the industry has no universally

accepted measurement standards that factor in distance from the mic, volume, angle relative to

axes, and so forth. Moreover, there is no standard for rendering these graphs. Major deviations

apparent on a graph calibrated vertically at +/-10dB look much more like a flat line if displayed on

a graph calibrated at +/-100dB. So in a world where everybody draws nice looking graphs because

they feel they must in order to be competitive, we simply decline to play the game until such time

that standards exist that level the playing field. As stated earlier, all M-Audio mics are manufactured

to within +/-1dB of each other and our golden reference standard.Were confident that your ears

will tell you everything else you need to know.

11

Page 12

Choosing & Using Microphones

12

Page 13

Chapter 2

Choosing & Using Microphones

Caring for Microphones

High-quality condenser mics lik

help ensure a lifetime of excellent performance.

e the M-Audio line represent an investment. A few basic tips will

Shock Protection

As you now know, condenser mics are constructed with extremely thin diaphragms and very high

tolerances. As such, condensers should be protected from abuse, especially physical shock.

(M-Audio capsules are rubber-mounted internally, but the need for caution still applies.) Keep

condenser mics away from situations in which they might be physically abused. Unlike a dynamic

microphone, condensers should always be mounted on a stand rather than hand-held (or swung

around on the end of a mic cord by a vocalist exhibiting showmanship). Similarly, wayward drum

sticks, guitar necks, violin bows and the like are not friends of condensers. As indicated earlier,

condensers should only be used live in controlled situations where the stage is protected from the

elements and is the exclusive domain of professionals. Take great care to avoid dropping a

consender mic or knocking over a mic stand holding onewe recommend duct-taping cables to

the floor in order to avoid tripping over them.

A soft mount (also know as a shock mount)one that suspends the mic in an elastic webis

usually desirable because the mount absorbs vibrations from the floor, passing trucks or airplanes,

and any modest inadvertent physical shock.While hard mounts provide no such shock absorption,

they are sometimes useful in tight situations or when exact placement is required (such as in an X-Y stereo

miking configuration).

Pop Filters and Windscreens

When pronouncing p , t and b sounds, vocalists often project extra energy toward the

microphone. A common result of this extra energy is unwanted pops in the sound, as well as the

expulsion of salivaa form of moisture detrimental to a condenser mic. For these combined

reasons, a pop filter is highly recommended when recording vocals with condenser microphones.

Typically a thin mesh stretched over a circular frame,the pop filter is mounted between the vocalist

and the mic capsule. (In a pinch, you can even construct a pop filter with a hanger and pantyhose.)

Windscreens, as the name implies, are sometimes used in outdoor recordings in order to reduce

wind noise and particulate matter striking the diaphragm. Windscreens typically consist of a

thickness of foam custom designed to fit over the capsule.Windscreens can reduce both low and

high frequency response, so they are typically not used as substitutes for pop filters.

Temperature and Humidity

The thin diaphragms and tight tolerances of condenser microphones make them susceptible to

temperature and humidity extremes. Never use condenser microphones when there is risk of

water damage (such as rain). Avoid high humidity situations such as seaside climates lacking air

conditioning.* The operating temperature of most condensers is 50…F to 95…F. If a condenser has

been outside in a colder environment (such as transporting it in winter), allow the mic to slowly

acclimate to room temperature before applying power in order to avoid condensation on the

capsule. Similarly, be careful not to leave condenser mics to bake in the trunk of your car on a hot,

sunny day.These same precautions apply to tube power supplies as well.

*Tip: Even the best condenser will start producing a crackling noise if inadvertently exposed to too much

humidity. In this event, an old trick is to place it near the heat of a light bulb for about half an hour.

13

Page 14

Choosing & Using Microphones

Cleaning and Storage

Always store a condenser microphone in its case when not in use. Particulate matter such as dust

can attach itself to the dia

wiping the metal exterior of a microphone down with a dry or slightly damp rag will be sufficient

to remove dust, dirt, fingerprints and the like. In the event that further cleaning is necessary, spray

a non-abrasive household cleaner such as Fantastik or Formula 409 onto a rag and wipe the metal

exterior with the rag. NEVER spray directly onto the microphone as it may damage the capsule.

NEVER attempt to clean the inside of a microphone. If performance degrades, contact M-Audio for

factory repair.

phragm and cause degradation of performance over time. In most cases,

14

Page 15

Choosing & Using Microphones

Chapter 3

Choosing & Using Microphones

full

sensivitiy

4'

2'

1/4

sensivitiy

1/16

sensivitiy

Basic Miking Concepts

Micr

ophone placement is an area in which art meets science. Microphone choice and placement is

somewhat subjective, much in the same way that choosing a guitar and amp is a matter of personal

pr

eference. Furthermore, each situation brings a difference confluence of performer, sound space,

recording equipment and creative forces.The question is not one of using the right or wrong mic

or technique, but simply one of what works best in each unique situation. Nonetheless,its good to

know the rules in order to break them with the greatest success. Here, then, are some

generalizations to consider. Note that since condenser mics are used in the vast majority of studio

situations, all of the following application tips apply to condenser mics.

All recording spaces have a unique ambient quality that determines how sound from the source

will be reflected. Those reflections are candidates for being picked up in the microphone(s) along

with the direct sound from the source.The choice of microphone, pattern and placement depends

in part on the balance you wish to strike between the sound source and the ambient characteristic

of the recording space. Another critical consideration is isolation from other sound sources. In

many ways, it all comes down to envisioning the sonic focus you want the mic to have.

Close-Miking vs. Distance-Miking Techniques

In general, close-miking techniques (where the microphone is very close to the sound source) are

used in conjunction with a cardioid or super-cardioid to focus the pickup pattern on the source

while simultaneously avoiding any significant influence from the surrounding space. Close-miking

with cardioids (or super-cardioids for extreme situations) is also very useful in isolating the sound

source from other performers. Note also that the closer the mic is to the source, the more

prevalent with be the performance by-products such as breath, fret noise, snare rattles and piano

hammers. With close-miking, the illusion of space is likely to

be added electronically in post-production via reverb and/or

other forms of time-delay devices.

Placing any mic at a greater distance from the source will add

more of the room reflections.

microphone placement intended to incorporate at least some

room reflections. An omni pattern really opens up the

recording to incorporate the full ambience of a room.

Regardless of the pattern, a proper balance must be found in

order to maintain the presence of the source while

incorporating surrounding ambience.When enough mics are

available, engineers often employ both close- and

distance-miking techniques simultaneously in order to control

the balance of direct and room sound.

The farther the microphone is placed from the source, the

less sensitive it is to the sound emanating from that source.

This falloff is not linear. Microphone sensitivity exhibits the

se squares

law of in

ver

microphone varies inversely as the square of the distance

or example, the typical mic is exposed to

F

.

om the sour

fr

ce

only one-quarter the sound power at twice the distance from

ou can think of this as the aural equivalent of

(Y

.

the sour

ce

the exponential falloff in light as y

light bulb.)

Recall also that large-diaphragm cardioid microphones exhibit

Distance-miking refers to

sound power reaching the

.

i.e

ou get fur

ther a

way from a

Microphones potentially receive

reflections from the room and other

objects as well as sounds emanating

directly from the source

Sound power falls off exponentially with distance

according to the law of inverse squares

15

Page 16

Choosing & Using Microphones

a proximity effect where the low-mid frequencies increase as the distance between the source and

mic decr

of any pattern.) With large diaphragms, then, the placement of the mic affects volume, room

ambiance and tonality

eases. (The proximity effect is not a big issue with omni patterns or medium-sized capsules

.

Large Capsules vs. Medium Capsules

You can achieve excellent results in most situations using our large-capsule mics.

As a rule of thumb, the large-capsule mics like ours will have more sensitivity in the low end than the medium

capsules simply because the diaphragms are larger. As previously mentioned, they also exhibit more proximity

effect in cardioid patterns (which can be a plus or a minus depending on the circumstances). Further, they take

up more physical space so they are less adaptable in tight situations. Conversely, medium capsules tend to

exhibit flatter frequency response regardless of distance and are more flexible when space is a consideration.

Youll eventually want to have both large- and medium-capsule models in your mic locker.

Dealing with Unwanted Low-Frequencies

Extraneous low-frequency content such as that induced by passing trucks or standing waves in the

room can present a problem during recording. Low frequencies are harder to compensate for with

acoustic treatment than are higher frequencies.Most condenser mics have a switch that introduces

a high-pass filter rolling off low frequencies starting at around 75Hz.This feature should be used

with care, since sound sources such as the male voice have content in this range. On the other

hand, low frequency roll-off can sometimes be used intentionally,like in a situation where you want

to reduce the boomy quality of an acoustic guitar. It is best to induce as little electronic circuitry

as possible. Use critical listening to determine if low-frequency roll-off is truly beneficial.

The Mic Preamp

Before the low-level signal from a mic can be used in the recording and mixing process, it must be

run through a preamp in order to boost the gain.Therefore, most pro recording engineers will tell

you that next most critical piece of gear after the microphone is the mic preamp.

Even the best microphone inputs on an affordable mixing board, sound card or all-in-one recorder

dont hold a candle to a dedicated mic preamp. Pro studios routinely pay thousands of dollars per

channel for dedicated outboard preamps.While thats not realistic for most project studios and

home recordists, it is indicative of the fact that good quality mic preamps are an important thing

to consider in your studio budget. If youre looking for a good preamp at budget prices, check out

M-Audios DMP3.And if youre interested in a high-end preamp that wont break the bank, see the

inset which follows, containing information about our revolutionary TAMPA preamp featuring

Temporal Harmonic Alignment.

Use of Processing During Recording

Engineers have varying opinions about the amount of processing to use during the actual recording process.

Part of it comes down to how much processing gear you have at your disposal for the subsequent mix session.

The predominant wisdom is to process as little as possible at any stageperiod.Thats a major reason why

having a good mic is essential to high-quality recordings.The more EQ and compression you have to apply, the

further you get away from a natural sound.

y engineers lik

Nonetheless,

ercome major deficiencies in the sound, and to achieve the hottest possible levels before clipping

v

o

or the highest signal-to-noise ratios.

f

to ensure that the signal is technically optimal. On the other hand, processing more specialized

effects such as reverb, chorus and delay are usually reserved for the mixing process, to yield

maximum flexibility in these more subjective and creative areas.

man

ecord with basic EQ and compression for two re a s o n s to

e to r

ding is typicall

In other w

pr

ds,

or

ocessing during r

ecor

y used

16

Page 17

The Recording Environment

Choosing & Using Microphones

Professional studios often have several different acoustic spaces avail able from small, relatively dead

isolation booth to ca

have fewer options, yet experimenting with recording in different rooms may yield interesting

results. Large rooms and tall ceilings will give a more open sound than small rooms and low ceilings.

The amount of furniture and reflectivity of various surfaces is also an influence. A carpeted floor,for

example, has a damping effect as opposed to the reflectivity

of a wood or tile floor.

There are many times when it is beneficial to create

methods of isolating the microphones or otherwise

controlling the room acoustics. Such scenarios include

having a poor sounding room, having an open mic in the

same room as recording gear exhibiting fan noise, or

recording multiple performers simultaneously. In cases like

these, consider solutions such as applying acoustic

treatment to the room, creating a temporary isolation

booth by hanging or tenting blankets, or building movable

partitions. Moving blankets,egg-crate foam and carpet are

Reflecting back on our discussion about tube versus solid state electronics, most highly revered mic

preamps are based on tube technology. Unfortunately tubes are part of what typically drives the price of

preamps into thousands of dollars.Thats why our design team set out to find out just why tubes sound

so good, and devise a way to land that sound at solid state prices. The result is far beyond tube

modeling;its a whole new technology we call Temporal Harmonic Alignment.

Natural sound sources such as strings, drum heads and vocal chords share a characteristic temporal or

phase relationship of harmonics to the fundamental when vibrating. Not coincidentally, our ears exhibit

the same qualities. Electronic circuitry induces distortion in the form of additional harmonics that do not

exhibit that relationship.Tubes strike the ear as having such a warm sound because the added harmonics

have the same temporal relationship as natural mechanismsalthough predominantly in the midrange.

This results in a sweet spot that makes things like vocals and guitars sound especially pleasing. We

designed TAMPA technology to produce that same phase relationship found in both tubes and nature.

And unlike tubes,TAMPAs sweet spot spans the full spectrum of your sound.

TAMPA also includes a dual optical servo compressor that alone is worth the price of admission.Three

fundamental problems plague engineers in designing compress ors dist ortion, noise and accuracy. The

VCA technology used in inexpensive compressors exhibits less than professional specs on all counts.

Simple optical servo technology is much more quiet and accurate, yet has its own issues with distortion.

The dual optical servo technology we use in TAMPA yields low noise, consistent accuracy and low

distortionand it comes built into a killer preamp.

TAMPAs entire signal path is designed to yield maximum fidelity without compromise, including discrete

Class A circuitry throughout.You also get tons of other professional features like an impedance selector

for optimizing vintage mics, and a massive 30dB of headroom. Audition a TAMPA for yourself and youll

see what all the fuss is about.

vernous rooms with natural reflections and long delay times. Home recordists

It is often beneficial to devise methods of

controlling room acoustics such as

constructing a tent using blankets

The Revolutionary New TAMPA Preamp

17

Page 18

Choosing & Using Microphones

common acoustic damping materials for home studio use. Music stands can also be reflective

1x

1x

3x

something y

ou can compensate for by simply draping towels over them.

While a r

easonable amount of absorption is often desirable for isolation, too much damping can

create an anechoic space that literally sucks the life out of a recording.In more permanent project

studios, consider creating a flexible acoustic environment. One solution is a series of gobos or

movable panels with a reflective surface on one side and an absorptive surface on the other.These

can then be moved and placed as desired for a given project. Another solution is to create

reflective walls with movable absorptive drapes in front of them.

Finally, dont overlook the acoustic resources you have available. Many a vocal track has been recorded by running

a mic into a tile or marble bathroom. (People like singing in the shower for good reasonthe sonic reflectivity

can make even mediocre voices sound great!) Recording engineers have frequently placed speakers and mics in

concrete stair wells to transform the concrete acoustics into reverb chambers. The drum track for Led

Zeppelins classic When the Levy Breaks was so incredibly ambient because John Bonhams drums were set up

in the stairwell of a stone castle. Similarly, some classic Jimmy Page tracks were realized by placing the guitar amp

in a fireplace and miking the top of the chimney. Again, the only real rule is to use what works for the track.

Phasing Issues with Multiple Microphones

The use of two microphones can introduce problems owing to phase discrepancies between the

micsand that potential increases with the number of microphones in concurrent use. In essence,

phasing problems occur when a sound reaches different mics at different times. Telltale signs are

different notes from the same source sounding at different volumes, or bass response that is overly

strong or overly shallow.

Here are a few tips in minimizing phasing problems when using multiple mics:

Move the mics. The first line of defense is to just get into the studio with headphones on and

move one or more of the problem mics until the phasing issue is resolved.

Check the cables. If a cable is accidentally wired out of phase, it can cancel out the signal from

a neighboring mic. Make certain that the mic cables are wired with continuity (i.e. pin 1 on one end

goes to pin 1 on the other end, and so forth).

Apply the 3:1 Rule. If possible, microphones should be

three times further away from each other than from the

source.As an example, microphones placed 5 inches away

from a sound source should be at least 15 inches apart

from each other. (This does not apply to the coincident

stereo miking techniques well discuss shortly.)

Minimize the number of microphones in

concurrent use.

The more open mics you have, the

greater the potential for phasing issues.While it might be

tempting to put a separate mic on each component of a

drum kit, for example, the tradeoff is the amount of time

it might take to eliminate phasing complexities. Less can be

more in situations where you have difficulty getting phasing

under control.

Separate the sound sources.With the exception of stereo recording,the general idea behind

using m

ultiple micr

ophones is to isolate the sound sour

to isolate the sources. Solutions include simply spreading the mics apart, putting them in separate

rooms or isolation areas,or using baffles, gobos and the like to provide additional separation. In the

case of tw

o mics on the same instrument, it is sometimes beneficial to devise a baffle that goes

between the mics.

Placing two microphones three times the distance

from each other as they are to the sound source

can eliminate phasing problems

ces. Phasing issues provide another reason

18

Page 19

Minimize reflective surfaces. Hard surfaces like wood floors, smooth walls, windows and

Choosing & Using Microphones

Choosing & Using Microphones

mir

rors are a common culprit in phase issues because they reflect sound back into the microphone.

If things sound odd, try moving the performer and/or mic. Also experiment with damping those

r

eflections with blankets, towels, baffles and the like.

Avoid boxing in mics. Microphones typically need a little breathing room in order to avoid

reflection. Omnis placed in a corner, for example, often sound like theyre, well, in a corner!

Similarly, placing the back of a cardioid too close to a surface or corner can sonically block the rear

ports, thereby distorting the effective polar pattern of the mic. Also, exercise care when using

baffles and gobos because these mechanisms do not completely absorb sound and can actually

cause reflections when placed too close to the mic.

19

Page 20

Choosing & Using Microphones

20

Page 21

Chapter 4

Choosing & Using Microphones

Choosing & Using Microphones

S

o

u

n

d

S

o

u

r

c

e

Stereo Miking Techniques

The use of stereo miking techniques utilizing matched pairs can make all the difference between

mediocre and outstanding recordings. After all, we listen to the world around us in stereo via

matched pairs of ears. Stereo miking can be used in applications ranging from individual instruments

to small ensembles to full orchestras and other concert events. In this section, well cover some of

the proven stereo miking techniques that have been used on countless professional recordings.(For

the purposes of this guide, stereo miking techniques are a subset of multi-microphone techniques

specifically aimed at accurately capturing a sound source with a left-right balance similar to the way

our ears perceive a sound source.)

Several factors must be considered in determining the best stereo miking technique for your

specific application. Although results vary with different polar patterns, it is common to use

distance from the source to determine the amount of room reflection versus direct source signal

desired. Physical restrictions in distance or position may also come into play, such as the need to

maintain clear lines of sight from audience to stage. It is also advisable to consider mono

compatibility, especially if the resulting material will wind up on radio or television.

The following stereo miking techniques fall into two basic categoriescoincident and spaced.

Coincident techniques rely on the microphones being placed in extremely close proximity to one

another, while

considered to be very accurate, some listeners find them to be too accurate. Common criticisms

are that the stereo field is too narrow or confined to the speakers on playback. (You can sometimes

compensate for this by moving the coincident mics slightly apart from each other in order to

introduce a time delay between sides.)

Spaced techniques are considered less accurate, yet more spacious sounding. In effect, widening the

space between mics widens the virtual placement of our ears. As with everything surrounding

microphones and their techniques, these considerations are subject to interpretation and

experimentation. In fact, it is not uncommon to find engineers employing techniques from both

categories simultaneously. In such a case,the coincident pairs provide a well-defined primary signal, while

the space pairs are placed to capture the reflected sound that provides extra control over ambience.

spaced techniques place them further apart. While the coincident methods are

X-Y

The X-Y miking technique employs a matched pair of

microphones overlapping as much as the mic bodies allow.

As pictured, place a pair of cardioid mics as close to each

other as possible with the capsules at an angle to each

other.The mic on the left captures the right signal and vice

versa. While 90 degrees is the most common angle

een the capsules, the working range is approximately

betw

60 to 135 degrees. The wider the angle, the wider the

ceiv

per

the sound source combined with the intended stereo

spread (the width of a stage, for example) will determine

ppr

the a

The use of cardioid patterns means that the X-Y configuration as a whole rejects signals from the rear. (You

can also experiment with super

imagery.) This rear rejection has several advantages.The configuration can be moved further away from a stage

eser

to pr

monaural.

eo field will be

ed ster

opriate angle

e sight lines.

v

easing the distance betw

Incr

.

The r

. In general, the distance from

X-Y miking employs a matched

pair of coincident cardioids

dioid patterns to provide more isolation between left and right sonic

-car

ting the stereo recording to

er

educed sonic clutter is also of benefit when con

een the coincident mic pair and the sound sour

v

ce decr

eases stereo

21

Page 22

Choosing & Using Microphones

separation and ca

++

--

S

o

u

n

d

S

o

u

r

c

e

S

o

u

n

d

S

o

u

r

c

e

17 cm

110

º

ptures more room reflections. In general,the X-Y technique using cardioids yields an accurate

stereo image exhibiting minimal acoustic reflections, although the separation is not as significant as some other

stereo miking techniques.

Blumlein

Named after British ster

Blumlein technique takes advantage of the polar patterns

inher

ent in figure 8 (bidirectional) mics. Recall that figure 8

patterns pick up equally well on two sides while exhibiting

strong rejection at 90 degrees off axis to those sides.In the

Blumlein technique, two figure 8 patterns are oriented 90

degrees from each other with the positive sides facing the

left and right sides of the sound source. Due to the

inherent side rejection, the area of greatest sensitivity of

one mic is the area of least sensitivity of the companion

mic. While the patterns overlap in the center, the signal

from each is 3dB down and, when combined, pick up a

uniform center signal.

The Blumlein arrangement yields very good stereo separation. Due to the fact that figure 8s are

equally sensitive on the back lobes, this configuration also picks up significant room reflections.

There are drawbacks to this technique,however.The fact that the back of the left mic is also picking

up reflections from the right rear of the room makes for poor mono compatibility. Further,

reverberant sounds coming from the sides of the acoustic space can enter the positive lobe of one

mic and the negative lobe of the other, thus causing the impression of poor localization and/or

hollow effects that can be disturbing. As a result, Blumlein is best used in situations where the

sound source, acoustic space and mic placement are optimal. Since this is a rarity, other stereo

techniques offering superior control are more frequently used.

eo pioneer Alan Blumlein, the

The Blumlein arrangement relies on a matched pair

of

coincident figure-8 patterns

ORTF

Developed by the French national broadcasting agency,

Office de Radio Tlvision Franaise, the

intended to emulate the placement of ears in the average

adult human head.Two cardioid capsules are placed 17cm

(about 6 - 3/4 inches) apart at a 110 degree angle to one

another. ORTF can produce the wide imagery and depth

common to the Blumlein technique, however the use of

cardioids means that the configuration captures much less

reverberant reflection.

The specified distance for ORTF makes wavelengths below about 500 Hz effectively phase

coherent. The time delays or phase incoherence above that frequency typically contribute to a

sense of stereo separation, along with the perception of a pleasing open or airy quality. ORTF also

exhibits adequate monophonic compatibility. Similar experiments by the Dutch broadcasting

counterpartNederlandsche Omroep Stichtingyielded the NOS technique where a pair of

cardioids are placed 30cm apart at a 90 degree angle.

Mid-Side

The Mid-Side technique utilizes special processing to capture very precise stereo imagery with

excellent mono applicability. A mid microphone (typically a cardioid) faces the center of the

sound source and captures the primary sound. A figure 8 (the side) is placed along the same

vertical axis with its lobes facing right and left, thereby picking up the extreme left and right

information due to the side rejection inherent in the figure 8 pattern.

This configuration does not constitute ster

encoder matrix such as the M-Audio Octane Preamp.The encoder adds the mid and side signals

ORTF technique is

eo until the signals ar

The ORTF technique positions a matched pair of

mics in a configuration similar to that of human ears

e processed through an M-S

22

Page 23

together to create one side of the stereo signal, and

M

+S

-S

S

o

u

n

d

S

o

u

r

c

e

D

D

_

2

D

_

3

~

S

o

u

n

d

S

o

u

r

c

e

conductor

1.5 m

2 m

S

o

u

n

d

S

o

u

r

c

e

Choosing & Using Microphones

subtracts the side signal fr

om the mid signal to create the

other.The result is a very accurate translation of the stereo

listening field.

The presence of an M-S balance control in

the encoder also allows the engineer to control the ratio

of mid signal to side signal, and therefore the perceived

width of the stereo field.

Note that Mid-Side is the only stereo miking technique

that does not rely explicitly on a matched pair of

microphones. However, high quality microphones are

imperative for overall sonic integrity, as well as to ensure

well-balanced capsules within the figure 8 mic. Note also

that Mid-Side offers a great deal of flexibility because the

The Mid-Side technique electronically

derives a stereo signal from a center mic

coincident with a figur

e 8

mid does not have to be a cardioid.If more audience noise or reflections from the back of the room

are desired,an omni could be used as the mid mic to great effect.The Mid-Side technique also offers

excellent mono compatibility because the recombination of the two out-of-phase side signals

cancels them out to leave only the mid or center signal.This process simultaneously minimizes side

reflections that can yield confusion in a mono conversion.

Spaced Omni

The spaced omni technique is often used for recording

orchestras.It employs a matched pair of omni mics typically

positioned four to eight feet in front of the sound source.

The mics are normally at the same height as the

performers, although raising them to 10 feet or more in

the air can increase perceived ambience. The distance

between the mics should be approximately 1/3 to 1/2 the

width of the sound stage. While spaced omni provides

excellent depth and stereo image, the center of the field

can tend to be less distinct. In situations where there is too

much unwanted background noise or the mics must be

placed further away due to logistics, experiment with using

carefully placed cardioids or supercardioids with this

spaced mic technique.

The spaced omni technique places omnis

at a distance of 1/3 to 1/2 of the sound

stage width from each other

As pointed out earlier, spaced miking techniques are not as technically accurate as some correlated

miking techniques. They can be susceptible to phase anomalies owing to reflections entering the

mics from various surfaces in the recording environmentalthough some people actually find this

pleasing. Many engineers consider spaced mic techniques best for recording relatively uncorrelated

sounds such as a pipe organ or outdoor ambience. Spaced techniques are also useful in creating

the surround channels for surround sound.

Decca Tree

Staff engineers at Decca Records (now Thorn-EMI)

developed a technique known as the

in the 1950s.This method and numerous variations are still

very popular today in the recording of film scores.

A T-shaped fixture houses a microphoneclassically an

omniat each of its thr

of the cross-arm are positioned approximately two meters

(approx. 79 inches) apart, while the central microphone is

1.5 meters (59 inches) away at the bottom of the T. This

structure is then mounted about eight to ten feet in the air

and positioned so that the central mic is just behind the

conductors head. The mics are tilted down at about 30

Decca Tree in England

ee ends.

The two mics at either end

The Decca Tree technique is very

popular in film scoring

23

Page 24

Choosing & Using Microphones

degrees and fanned out to cover the physical spread of the orchestra. Another pair of mics is often

placed fur

in the ambient space.

Decca Tree is favored in the film industry because it provides a spacious sound along with good

stereo imagery that works well with processes like Dolby and surround sound. There is also the

advantage of a discrete center mic for both monaural and center channel use.Variations abound,

including the substitution of other polar patterns, spreading or narrowing the distance between the

mics, and aiming the left and right mics at specific orchestra sections to be featured.

ther back in the hall on either side of the orchestra in order to capture room reflections

24

Page 25

Chapter 5