CRU RAX215DC Installation Manual

Curr Pediatr Res 2017; 21 (1): 148-157

ISSN 0971-9032

www.currentpediatrics.com

Curr Pediatr Res 2017 Volume 21 Issue 1

148

Introduction

According to the International Association for the Study of

Pain (IASP) Pain is “an un-pleasant sensory and emotional

experience associated with actual and potential tissue

damage”. Pain has also been dened as “existing whenever

they say it does rather than whatever the experiencing

person says” [1-4]. It is one of the most dreading and

devastating symptom commonly propagated in peoples

with advanced chronic conditions including cancer patents.

Pediatric patients are the most under treated and present to

hospital for pain compared to adults; because of the wrong

belief that they neither suffer pain nor they remember

painful experiences [5]. The quality of life experienced

by the patient can greatly reduce, regardless of their basic

diagnosis. Thus, if pain will be poorly managed, it can

reect the inuence on family and careers causing different

which may leads to increased rates of hospital admission

[5,6]. Uncontrolled pain has also direct impact on health

outcomes and more than a few effects on all areas of life.

The emotional, cognitive, and behavioral components of

pediatric patient are also important to assess pain and to

simplify the management practices [7,8].

A long-term negative effect of untreated pain on pain

sensitivity, immune functioning, neurophysiology,

attitudes, and health care behavior are supported with

numerous evidences. Health care professionals’ who care

for children are mainly responsible for abolishing or

assuaging pain and suffering when possible [5,7,9]. The

practice of pediatric pain treatment protocol has made

great progress in the last decade with the development

and validation of pain valuation tools specic to pediatric

patients. Almost all the major children hospitals now

have dedicated pain services to provide evaluation and

immediate treatment of pain in any child [10,11].

In pediatric age, it is more difcult to assess and treat pain

effectively relatively to adults. The lack of ability to notice

pain, immaturity of remembering painful experiences

and other reasons are the reection of persistence of

myths related to the infant’s ability to perceive pain [12].

However, the treatment of pain in childhood is like the adult

management practice which includes pharmacological and

non-pharmacological interventions. On the other hand,

it critically depends on an in-depth understand of the

developmental and environmental factors that inuence

nociceptive processing, pain perception and the response

to treatment during maturation from infancy to adolescence

[13,14].

The practice of assessing pain and its management in

pediatric patients can show a discrepancy based on the

different countries and their respective health institutions.

So, this review focused on the contemporary practice

and new advances in pediatric pain assessment and its

management.

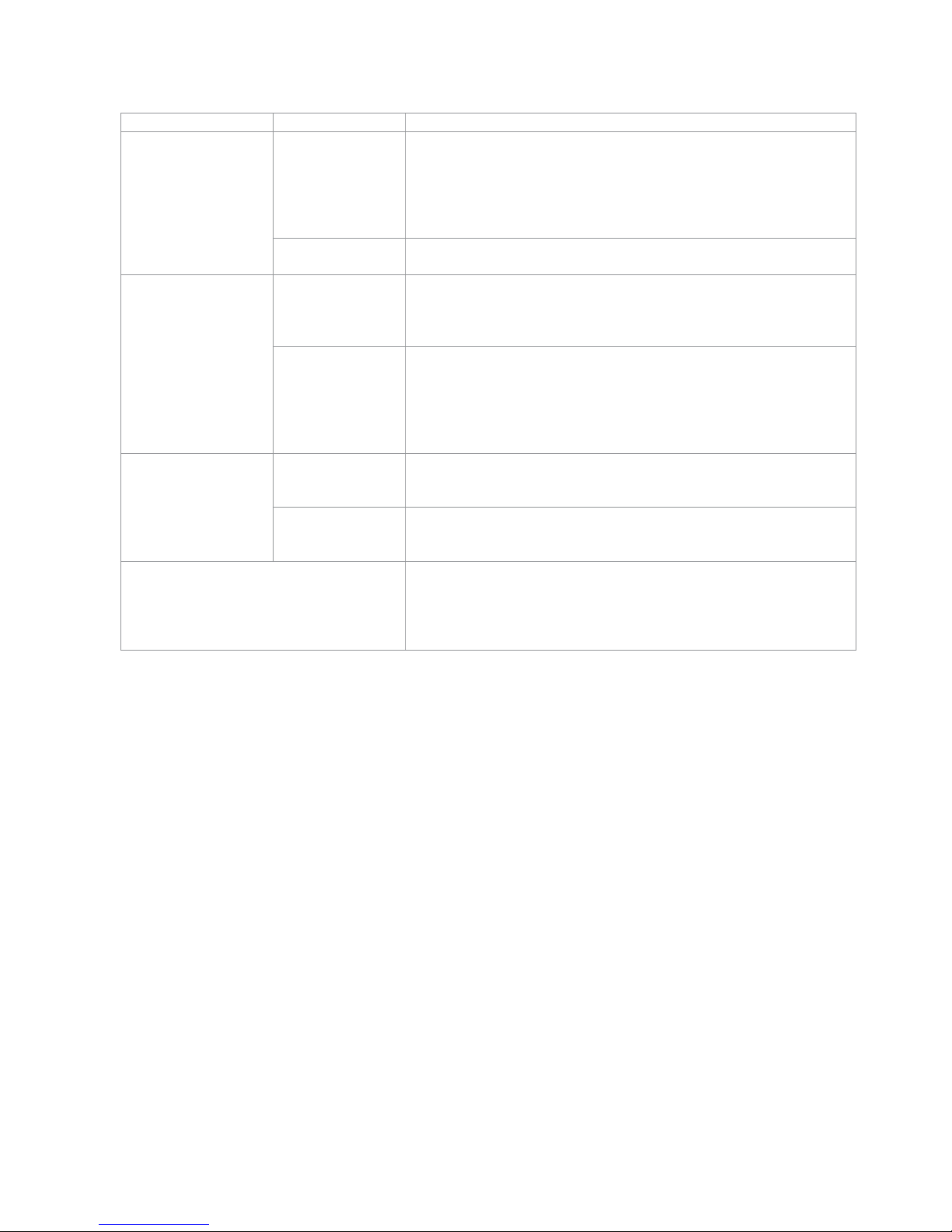

Classication of Pain

Many classication systems are used to describe the

different types of pain. The most common classication

schemes refer to pain as acute or chronic; malignant or

nonmalignant; and nociceptive or neuropathic [15]. Most

studies are agreed with the following classication of pain

(Table 1).

Assessment and treatment of pain in pediatric patients.

Halefom Kahsay

Department of Pharmacy, Collage of Health Science, Adigrat University, Adigrat, Ethiopia.

Pediatric patients experience pain which is more difcult to assess and treat relatively to

adults. Evidence demonstrates that controlling pain in the pediatrics age period is benecial,

improving physiologic, behavioral, and hormonal outcomes. Multiple validated scoring

systems exist to assess pain in pediatrics; however, there is no standardized or universal

approach for pain management. Healthcare facilities should establish pediatrics pain control

program. This review summaries a collection of pain assessment tools and management

practices in different facilities. This systematic approach should decrease pediatric pain and

poor outcomes as well as improve provider and parent satisfaction.

Abstract

Keywords: Pain, Pain assessment, Pain management, Pediatric patients.

Accepted January 30, 2017

Assessment and treatment of pain in pediatric patients.

Curr Pediatr Res 2017 Volume 21 Issue 1

149

Assessment of Pain in Pediatrics

Pain is often referred to as the “fth vital sign” and it should

be assessed and recorded as often as other vital signs.

The appropriate intervention of pain is planned based

on the accurate valuation of pain. Organized and routine

pain assessment by using the standardized and validated

measures is accepted as a corner stone for effective pain

management in patients, unrelatedly to the age or other

conditions [21]. A study in Brazil suggests that consistent

accomplishment of assessments of pain using ordinary

scales, such as Face, Legs, Activity, Cry and Consolability

score and other bodily parameters are mandatory to

optimize pain management in pediatric intensive care

units [22]. As pain is a subjective experience, individual

self-reporting is the favorite method for assessing

pain. However, when valid self-report is not available

as in children who cannot communicate due to age or

developmental status, the observational and behavioral

assessment tools are acceptable substitutions [5,7,22].

The use of the pain management algorism on Stollery

children’s hospital shows signicant improvement for

assessment of pain in pediatrics. The pre and post analysis

indicated in a staff (n=17) given that a feedback of 41.2%

felt that the algorism improved their ability to assess and

manage pain in children equally, 35% felt that it increased

their capacity to communicate a child’s pain with other

health care team members, 52.9% felt that the algorism

should be further applied on other units across the hospital

[23]. Even though, the assessment of pain symptoms is

easy in adults, selection of appropriate pain assessment

tools should consider age, cognitive level and the presence

of eventual disability, type of pain and the situation in

which pain is occurring in children. Therefore, healthcare

professionals need to be aware of their limitations in

addition to trained in the use of pain assessment tools

[7,24,25].

The assessment in Canadian pediatric teaching hospitals

indicated out of 265 children, majority (63%) of them

found with a minimum of one documented pain assessment

tool, 30% of children had at least two assessment tools,

17% had 3-5 measurement tools and 16% had at least

six assessments in 24 h of admission. Most (63%) of

the children were nd a different document of 666 pain

assessment tools, with a median of three assessments per

one child [14]. Parent, patient, as well as staff satisfaction

is positively associated with accurate assessment of pain in

addition to well improvement of pain management. Brief

and well validated tools are available for the assessment

of pain in non-specialist settings. Nevertheless, each tool

cannot be broadly suggested for assessment of pain in all

Category Sub-classication Description

Pathophysiological

Nociceptive pain

This type of pain arises as the tissue injury activates specic pain receptors

named nociceptors, which are sensitive to noxious stimuli. These

receptors’ can respond to different stimulus and chemical substances

released from tissues in response to oxygen deprivation, tissue disruption

or inammation. It can be somatic or visceral pain based on the site of

the activated receptors.

Neuropathic pain

This type of pain arises when the abnormal processing of sensory input

recognized by the peripheral or central nervous system.

Etiologically

Non-malignant

It includes the pain due to chronic musculoskeletal pains, neuropathic

pains, visceral pain (like distension of hollow viscera and colic pain) and

chronic pain in some specic anemia. Rehabilitation care is there main

treatment protocol.

Malignant

This is the pain in potentially life-limiting diseases such as multiple

sclerosis cancer, HIV/AIDS, end stage organ failure, amyotrophic lateral

sclerosis, advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Parkinsonism

and advanced congestive heart failure. These illnesses are indicating for

similar pain treatment that emphases more on symptom control than

function.

Based on duration

Acute

This is pain of recent onset and probable limited duration. It usually has

an identiable temporal and causal relationship to injury or disease. Most

acute pain resolves as the body heals after injury.

Chronic

It is the pain which lasts a long time mostly 6 months, which commonly

persisting beyond the time of curing of an injury and may be without any

clearly identiable cause.

Based on location

When Pain is often classied by body site (e.g. on head, on the back

or neck) or it can be the anatomic function of the affected tissue (e.g.

vascular, rheumatic, myofascial, skeletal, and neurological). It does not

provide a background to resolve pain, but it can be useful for differential

diagnoses.

Table 1. The general classication of pain in pediatrics [3,4,8,15-20]

Kahsay

Curr Pediatr Res 2017 Volume 21 Issue 1

150

after observing the infant for 1 min. Among two observers

a reliability of FLACC was established in a total of 30

children in the post anesthetics care unit (PACU) (r=0.94).

After analgesic administration, validity was established

by demonstrating a proper decrease in FLACC scores.

Correspondingly, a high degree of association was found

between PACU nurse’s global pain rating scale, FLACC

scores, and with the objective scores of pains scale. This

tool has been established in various settings and in diverse

patient populations and nds that as reliable and valuable.

It provides a simple background for computing pain

behaviors in children who may not be able to put into words

the incidence or severity of pain. Lastly, the constructed

validity is supported by analgesic administration as the

scores decreases signicantly. Another recent studies

have demonstrated that FLACC was the most chosen in

terms of sensible qualities by clinicians at their respective

institutions [27,29,32-35]. Although the tool can be

used by clinicians, it is more effective with parent input

to provide a description of ‘baseline’ behavior. This is

supported by the ndings of the Malvinas study, which

suggested that the addition of unique descriptors allowed

parents to augment the tool with individual behaviors

unique to their children. In addition, for infants who show

good comprehension and motor skills, this pain assessment

tool can be used as an alternative [36]. The FLACC scale

has 98% sensitivity and 88% specicity in assessing pain

levels [34]. Therefore, those different studies concluded

that FLACC scale is the most appropriate measurement

tool for pain assessment in infants (Table 3).

Cries Pain Rating Scale

0 1 2

Crying No high pitched inconsolable

Requires O

2

for sat >95% No <30% >30%

Increased vital signs HR and BP <or=pre-op

HR and BP;

Increased <20% of

pre-op

HR and BP; Increased >20% of

pre-op

Expression None Grimace Grimace/grunt

Sleepless No

Wakes at frequent

intervals

Constantly awake

Table 2. Neonatal pain rating scale [27-29]

children and across all settings. Individual needs of the

children lead to assess and re-evaluate of pain consistently

as a mandatory in every situation. On top of that,

ethnicity, language, and cultural factors should be under

consideration as they may inuence pain assessments and

its expression [5,12,26].

Most formal and commonly used means of pediatric

assessment tools for pain are available and categorized

depending the pediatrics age.

Pain Assessment in Neonates

Neonates pain rating scale (NPR-S): Major guidelines

indicate that the assessment of pain in neonates (term

babies up to 4 weeks of age) had better be use the Crying,

Requires oxygen for saturation above 95%, Increasing

vital signs, Expression and Sleepless (CRIES) scale

(Table 2) [2,24,27-30].

Several other pain scales have been designed for the

objective assessment of neonatal pain, including the

COMFORT (“behavior”) score, pain assessment tool, scale

for use in newborns, distress scale for ventilated newborns

and infants. Although these assessments are validated as

research tools, the mainstay of appropriate management

includes the caregiver’s awareness, knowledge of clinical

situations where in pain occurs, and sensitivity to the

necessity of preventing and controlling pain [31].

Assessment of pain in infants: On a study in Australia

hospitals, Infants (1 month to approximately 4 years) were

scored using the face, leg, activity, cancelability and cry

(FLACC) measuring tool. Scoring should be done by staff

FLACC Behavioral Pain Assessment Tool

0 1 2

Face

No particular expression

or smile

Occasional grimace/frown withdrawn or

disinterested

Frequent/constant quivering

chin, clenched jaw

Legs

Normal position or

relaxed

Uneasy, restless or tense Kicking or legs drawn up

Activity

Lying quietly, normal

position, moves easily

squirming, shifting back and forth, tense Arched, rigid or jerking

Cry

No cry Moans or Whimpers, occasional complaint

Crying steadily, screams or

sobs, frequent complaints

Cancelability

Content or relaxed

Reassured by occasional touching,

hugging or being talked to, distractible

Difcult to console or comfort

Table 3. FLACC assessment tool [27,29,32-35]

Loading...

Loading...