Page 1

© 2000 Crown International, All rights reserved.

PZM® , PCC®, SASS® and DIFFEROID®, are registered trademarks of

Crown International, Inc. Also exported as Amcron

131374-1

®

6/00

Crown International, Inc

P.O. Box 1000, Elkhart, Indiana 46515-1000

(219) 294-8200 Fax (219) 294-8329

www.crownaudio.com

Page 2

MICROPHONE TECHNIQUES FOR VIDEO

No matter what your video application — sports,

news, corporate training — the soundtrack quality

depends on the microphones you choose and where

you place them. This booklet covers microphone

techniques to help you achieve better audio for

your video productions.

There are many types of microphones, each designed to help you solve a specific audio problem.

We’ll sort out these types and tell where each one is

useful. Then we’ll cover specific applications — how

to use microphones effectively in various

situations.

TRANSDUCER TYPES

A microphone is a transducer, a device that converts energy from one form into another. Specifically, a microphone converts acoustical energy

(sound) into electrical energy (the signal).

A ribbon microphone works the same, except that

the diaphragm is also the conductor. It is a thin metal

foil or ribbon suspended in a magnetic field.

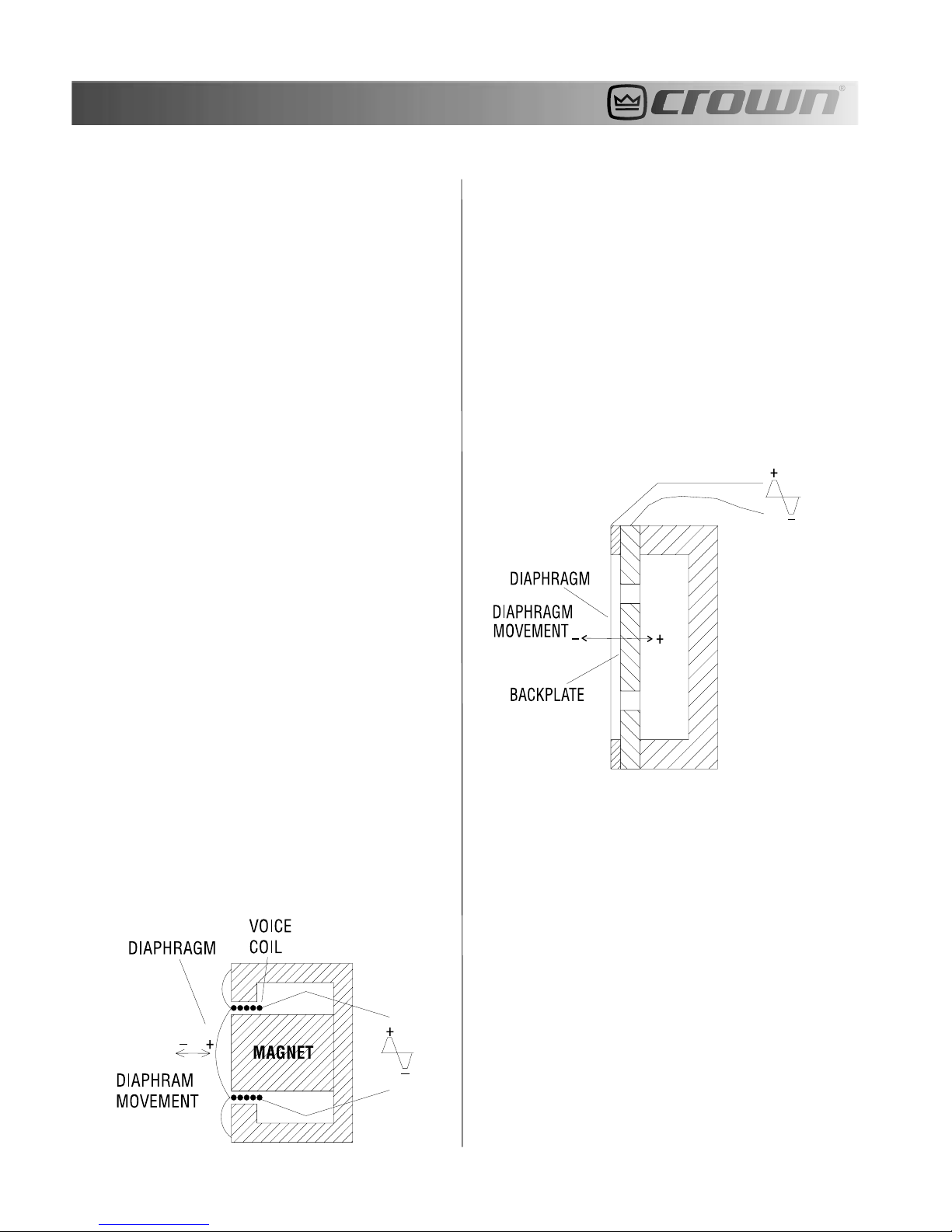

In a condenser microphone (Figure 2), a diaphragm

and an adjacent metallic disk (backplate) are

charged to form two plates of a capacitor. Sound

waves striking the diaphragm vary the spacing between the plates; this varies the capacitance and

generates an electrical signal similar to the incoming sound wave.

Fig. 2 – A condenser microphone.

Microphones differ in the way they convert sound

to electricity. Three popular transducer types are dynamic, ribbon, and condenser.

In a dynamic microphone (Figure 1), a coil of wire

attached to a diaphragm is suspended in a magnetic field. When sound waves vibrate the diaphragm, the coil vibrates in the magnetic field and

generates an electrical signal similar to the incoming sound wave.

Fig. 1 – A dynamic microphone.

The diaphragm and backplate can be charged either by an externally applied voltage or by a permanently charged electret material in the diaphragm

or on the backplate.

Because of its lower diaphragm mass and higher

damping, a condenser microphone responds faster

than a dynamic microphone to rapidly changing

sound waves (transients).

Dynamic microphones offer good sound quality, are

especially rugged, and require no power supply.

Condenser microphones require a power supply to

operate internal electronics, but generally provide

a clear, detailed sound quality with a wider,

smoother response than dynamics.

2

Page 3

Currently, all Crown microphones are the electret

condenser type — a design of proven reliability and

studio quality.

POLAR PATTERNS

Microphones also differ in the way they respond to

sounds coming from different directions. The sensitivity of a microphone might be different for

sounds arriving from different angles. A plot of microphone sensitivity verses the angle of sound incidence is called its polar pattern. Several polar

patterns are shown in Figure 3.

Fig. 3 – Polar patterns.

Three types of unidirectional patterns are the cardioid, supercardioid, and hypercardioid pattern. The

cardioid pattern has a broad pickup area in front of

the microphone. Sounds approaching the side of

the mic are rejected by 6 dB; sounds from the rear

(180 degrees off-axis) are rejected 20 to 30 dB. The

supercardioid rejects side sounds by 8.7 dB, and

rejects sound best at two “nulls” behind the microphone, 125 degrees off-axis.

The hypercardioid pattern is the narrowest pattern

of the three (12 dB down at the sides), and rejects

sound best at two nulls 110 degrees off-axis. This

pattern has the best rejection of room acoustics,

and provides the most gain-before-feedback from

the main sound reinforcement speakers.

Choose an omnidirectional mic when you need:

All-around pickup

Best pickup of room acoustics (ambience or

reverb)

An omnidirectional (omni) microphone is equally

sensitive to sounds coming from all directions. A

unidirectional microphone is most sensitive to

sounds coming from one direction — in front of

the microphone. A bidirectional (figure-eight)

microphone is most sensitive in two directions:

front and rear.

An omni microphone is also called a pressure mi-

crophone; a uni- or bi-directional microphone is

also called a pressure-gradient microphone.

Extended low-frequency response

Low handling noise

Low wind noise

No up-close bass boost

Choose a unidirectional mic when you need:

Selective pickup

Rejection of sounds behind the microphone

Rejection of room acoustics and leakage

More gain-before-feedback

Up-close bass boost

An omnidirectional boundary microphone (such as

a PZM) has a half-omni or hemispherical polar pattern. A unidirectional boundary microphone (such

as a PCC-160 or PCC-170) has a half-supercardioid

polar pattern. The boundary mounting increases the

directionality of the microphone, thus reducing

pickup of room acoustics.

3

Page 4

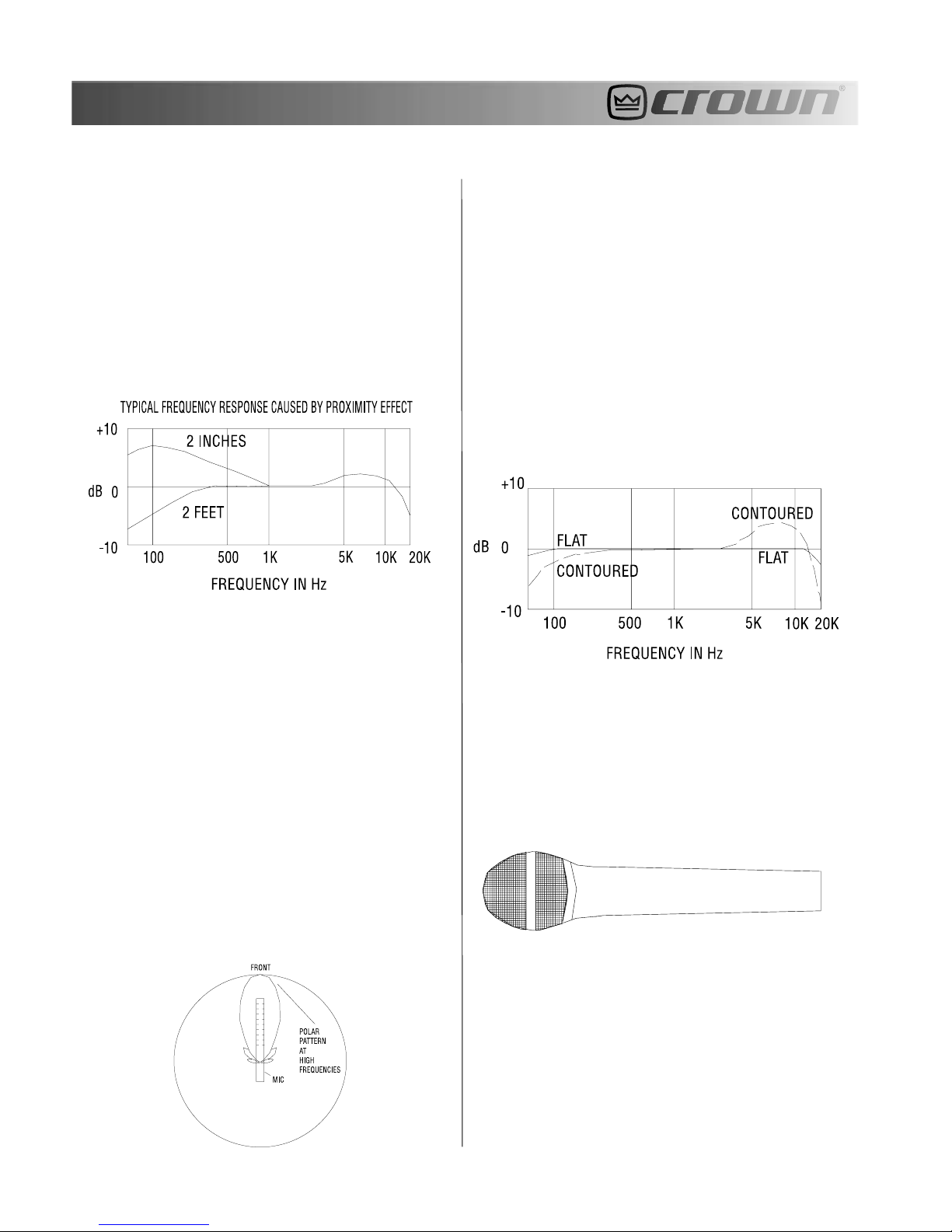

Most unidirectional mics have proximity effect, a

rise in the bass when used up close. Figure 4 is a

frequency-response graph that illustrates proximity effect. When the microphone is 2 feet from the

sound source, its low-frequency response rolls off.

But when the microphone is 2 inches from the sound

source, its low-frequency response rises, giving a

warm, bassy effect.

Fig. 4 – Proximity effect.

A special type of unidirectional microphone is the

variable-D type. Compared to a standard single-D

directional microphone, the variable-D has almost

no proximity effect, so it sounds natural when used

close up. The variable-D type also has less handling

noise and pop.

The most highly directional pattern is that of the

shotgun or line microphone (Figure 5). The shotgun microphone is used mainly for distant miking

(say, for dialog pickup where you want the mic to

be off-camera). It is highly directional at high

frequencies and hyper-cardioid at low frequencies.

The longer the shotgun mic is, the more directional

it is at mid-to-low frequencies.

Fig. 5 – Shotgun microphone and its polar pattern.

FREQUENCY RESPONSE

Each microphone has a different frequency response, which indicates the tonal characteristics

of the microphone: neutral, bright, bassy, thin, and

so on. Figure 6 shows two types of frequency response: bright (contoured) and flat. A bright frequency response has an emphasized or rising highfrequency response, which adds clarity, brilliance,

and articulation. A flat frequency response sounds

natural.

Fig. 6 – Frequency response.

FORMS OF MICROPHONES

Microphones come in many shapes that have different functions:

Fig. 7 – Handheld microphone.

Handheld (Figure 7). Used in the hand or on a mic

stand. An example is the Crown CM-200A cardioid

condenser microphone.

4

Page 5

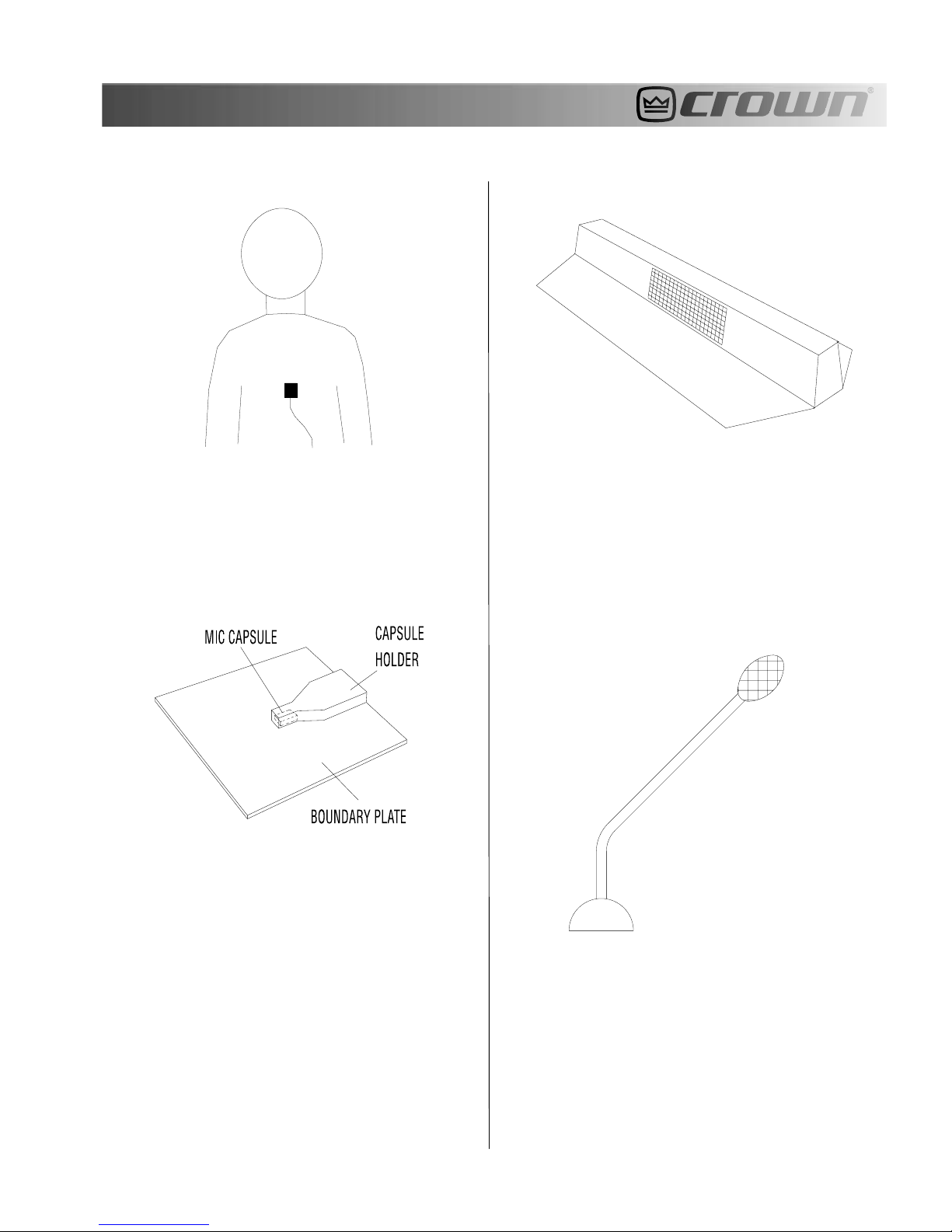

Fig. 8 – Lavalier microphone.

Lavalier (Figure 8). A miniature microphone which

you clip onto the clothing of the person speaking.

Two examples are the Crown GLM-100 (omni) and

GLM-200 (hypercardioid).

Fig. 9 – Boundary microphone.

Fig. 10 – Unidirectional boundary microphone.

The PCC (Figure 10) is a unidirectional boundary

microphone. When you place it on a surface, it has

a half-supercardioid polar pattern. The rugged PCC160 is especially useful for stage-floor pickup of

drama and musicals; the PCC-170 has a sleeker look

for miking a group discussion at a conference table.

Fig. 11 – Lectern microphone

Boundary (Figure 9). Boundary microphones are

meant to be used on large surfaces such as stage

floors, piano lids, hard-surfaced panels, or walls.

Boundary mics are specially designed to prevent

phase interference between direct and relected

sound waves, and have no off-axis coloration. Free-

field microphones are meant to be used away from

surfaces, say for up-close miking.

Crown Pressure Zone Microphones® (PZMs®) and

Phase Coherent Cardioids® (PCCs®) are boundary

microphones; Crown GLMs, CMs, and

LMs are free-field microphones.

Lectern A lectern microphone (Figure 11) is designed to mount on a lectern or pulpit. For example,

the Crown LM-300A and LM-300AL are slim, elegant units that plug into an XLR connector in the

lectern. The LM-301A screws onto a mic stand or

desk stand. Each has a silent-operating gooseneck.

The Crown LM-201 mounts permanently on the lectern, and has a rugged ball-and-socket swivel that

adjusts without any creaking.

5

Page 6

Fig. 12 – Stereo microphone.

A mid-side microphone is mono-compatible; that

is, it has the same frequency response in mono or

stereo. That’s because there is no spacing between

the mic capsules. If there were a spacing, this would

create a delay between left and right signals which

can cause phase cancellations in mono. The Crown

SASS stereo microphone, explained next, has

spaced mic capsules but is still mono-compatible

because of its special design.

Stereo: A stereo microphone combines two directional microphone capsules in a single housing for

convenient stereo miking (Figure 12). A special type

of stereo microphone is called mid-side or MS. It

uses two capsules: a MID unit aiming toward the

middle of the sound source, and a SIDE unit with a

bi-directional pattern aiming to the sides (Figure 13).

The mid unit can have any pattern, but cardioid is

most common.

Fig. 13 – Mid-side microphone polar patterns.

Fig. 14 & 15 – SASS-P MK

II stereo microphone.

The Crown SASS-P stereo microphone is shown

in Figure 14 (top view) and Figure 15 (front view).

It is made of two Pressure Zone Microphones

mounted on small boundaries that are angled apart

left and right. The capsules are spaced apart the

same distance as your ears. As a result, the SASS

gives very precise and spacious stereo imaging.

Between the two mic capsules is a special foam

baffle.The baffle creates amplitude or level differences between channels at high frequencies. Since

the two channels are different amplitudes, any

phase cancellations in the mono sum are incomplete, so the resulting dips in the frequency response are relatively slight. Thus, the SASS is

mono-compatible.

Inside the microphone or in an outboard box, the

mid and side signals are summed and differenced

to produce directional patterns aiming left and right.

By controlling the ratio between mid and side signals, you can control the stereo spread or stage

width. This can be done during recording or during

post-production.

6

Page 7

ELECTRICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Whatever type of microphone you use, it should

have a low-impedance balanced output with a 3pin pro audio connector. This allows long cable runs

(hundreds of feet) without hum pickup or high-frequency loss. All modern mixers are designed to work

with low-impedance microphones.

MICROPHONE-TECHNIQUE BASICS

How to reduce reverberation

Reverberation is sometimes loosely called “room

acoustics,” “ambience,” or “reverb.” It is a pattern

of sound reflections off the walls, ceiling, and floor.

For example, reverberation is the sound you hear

just after you shout in an empty gymnasium.

Too much reverberation in a recording sounds distant or muddy, and reduces intelligibility. To reduce

reverberation:

•Place the mic closer to the sound source.

•Use an automatic (gated) mixer. This device turns

off all microphones not in use, providing a clearer,

less muddy sound.

•Pick up each electric instrument with a direct box

or cable.

•Use a room or studio with dead acoustics. The

walls, ceiling and floor should be covered with

sound-absorbing material.

•Select a mic with a tighter polar pattern. Hypercardioid and super-cardioid patterns reject reverb

more than cardioid. Cardioid and bi-directional patterns reject reverb equally well, and more than an

omni.

How to reduce background noise

•Stop the noise at its source: turn off appliances

and air conditioning; wait for airplanes to pass; close

and seal doors and windows; use a quiet room.

•Mike close with directional mics.

•Pick up each electric instrument with a direct box

or cable.

•Aim the null of the polar patern at the offending

noise source. The null is the angle off-axis where

the mic is least sensitive. Different polar patterns

have nulls at different angles. Shown below and in

Figure 16 are the null angles for various polar patterns:

Cardioid:180 degrees.

Supercardioid: 125 degrees.

Hypercardioid: 110 degrees.

Bidirectional: 90 degrees.

Fig. 16 – Polar patterns

.

The table below tells how many dB of reverb rejection you can expect from various polar patterns

compared to an omni-directional pattern at the same

working distance:

Omnidirectional: 0.0 dB

Cardioid:-4.8 dB

Bidirectional: -4.8 dB

Supercardioid: -5.7 dB

Hypercardioid: -6.0 dB

How to pick up sound at a distance

The farther a microphone is placed from a sound

source, the more reverberation and background

noise you pick up. Also, you hear more mixer selfnoise relative to the signal because the mixer gain

must be higher with distant miking.

7

Page 8

To clearly pick up sound at a distance:

•Use a microphone with low self-noise (say, less

than 22 dB SPL), such as the Crown PCC-160, PCC170, CM-200A, or any PZM).

•Boost the presence range on your mixer’s EQ

(around 5 kHz).

•If necessary, compensate for air losses at high fre-

quencies by boosting EQ around 15 kHz.

•If you’re using a PZM, make it directional. To do

this, mount the tip of it cantilever (mic-capsule

holder) in a corner of the room, or in a corner made

of three plexiglass panels. Large panels provide

deeper bass and more directionality at low

frequencies than small panels.

•Use directional microphones. You can place a di-

rectional mic farther from its source than an omnidirectional mic and pick up the same amount of reverberation. The table below and Figure 17

show the distance multiplier for each pattern:

Omnidirectional: 1.0

Cardioid: 1.7

Bidirectional: 1.7

Supercardioid: 1.9

Hypercardioid: 2.0

How to reduce phase cancellations between two

mics:

If two microphones pick up the same sound source

at different distances, and their signals are fed to

the same channel, this might cause phase cancellations. These are peaks and dips in the frequency

response caused by various frequencies combining out-of-phase. The result is a colored, filtered

tone quality.

To reduce phase cancellations between two microphones:

•Mike close.

•Spread sound sources farther apart.

•Follow the 3-to-1 rule (Figure 18): The distance

between mics should be at least three times the micto-source distance. For example, if two microphones

are each 1 foot from their sound sources, the mics

should be at least 3 feet apart to prevent phase cancellations.

•Don’t use two mics when one will do the job. For

example, use just one mic on a lectern. If the talker

wanders, use a lavalier mic instead, such as a GLM-

100.

Fig. 18 – The 3-to-1 Rule.

Fig. 17 – For various polar patterns, distances from

the sound source that provide equal reverb pickup.

For example, if an omni mic is placed 1 foot from a

sound source, you can place a supercardioid mic at

1.9 feet and pick up the same amount of reverb as

the omni.

8

Page 9

How to reduce phase cancellations from surface

reflections:

Sometimes you must place a microphone near a

hard reflective surface. Situations where this might

occur are reinforcing drama, musicals, or opera with

the microphone near the stage floor, recording a

piano with the mic near the raised lid, or recording

an instrument surrounded by reflective baffles.

This situation can cause phase cancellations which

give a strange tone quality. Solve the problem by

using a Crown PZM or PCC microphone taped to

the piano lid, wall, floor, table, or other large flat

surface.

How to reduce handling noise and thumps

•Use an omnidirectional microphone, such as a

GLM-100 or any PZM.

•Use a directional microphone with low sensitivity

to handling noise and thump, such as the CM-200A,

CM-310A, PCC-160, PCC-170, or PCC-200.

•Use a directional microphone with an internal shock

mount.

•Use a shock-mount stand adapter, either handheld

or on a mic stand an example is the CM-SM.

•Place the mic stand on foam or sponges.

How to reduce lavalier clothing noise

•Tape the cable to clothing.

•Strain-relieve the cable by using a belt clip.

•Use an omni-directional lavalier (GLM-100) rather

than a uni-directional lavalier (GLM-200). The omni

type has less pickup of mechanical vibration.

How to reduce proximity effect:

Proximity effect is the bass boost you hear when

you mike close with a single-D directional microphone. “Single-D” means that the microphone has

a single distance from its front sound entry to the

rear sound entry. The close the mic is to the sound

source, the more bass you hear. To reduce proximity effect:

•Use an omnidirectional microphone such as a

Crown GLM-100 or PZM.

•Use a unidirectional microphone, but turn down

the excess bass with your mixer’s EQ.

•Use a variable-D unidirectional microphone.

How to reduce pop

Pop: is an explosive breath sound produced by the

letters “p,” “b,” or “t.” When a person says words

containing these sounds, a turbulent puff of air is

forced from the mouth. This air puff hits the microphone and makes a thump or little explosion called

a “pop.”

To reduce pop:

•Use an omnidirectional microphone, such as a

Crown PZM.

•Use a microphone with a built-in pop filter or ball-

shaped grille, such as the Crown CM-200A or CM310A.

•Place an external foam pop filter on the micro-

phone.

•Roll off low frequencies below 100 Hz.

•Place the microphone out of the path of pop travel

— above, below, or to the side of the mouth.

For example, Figure 19 shows an interview with the

microphone placed midway between the two people,

below their mouths. Figure 20 shows how a studio

announcer can be miked to prevent pop. The microphone is at eye level so that pops shoot under

the microphone and miss it. A hoop-type pop filter

also works quite well.

Fig. 19 – Reducing pop during an interveiw.

Fig. 20 – Miking a studio announcer to prevent

breath pops.

9

Page 10

How to reduce wind noise:

Use the same methods mentioned under “How to

reduce pop.” For best wind-noise rejection, keep

an air space between the foam windscreen and the

microphone. The bigger the windscreen, the better

it works. A large windscreen called a blimp is available for a shotgun mic. A blimp is covered in fur

and attenuates high frequencies somewhat, but is

more effective than a foam windscreen.

How to reduce distortion:

If you’re picking up a very loud sound source such

as a person yelling into a microphone, the microphone will generate a high-voltage signal that can

overdrive the mic preamp in your mixer, causing

distortion. To prevent this,

•In your mixer, switch in the pad or reduce the gain

trim, if any.

•Plug an in-line pad between the mic cable and the

mixer mic input.

•If a condenser mic has a pad built in, switch it on.

•Place the mic farther from the sound source.

To prevent shifting sound images, don’t move (pan)

a stereo microphone once it is set up.

Avoid extreme differences between sound and picture. Be careful not to reverse left and right channels (say, by inverting an end-fired stereo microphone).

Mono compatibility is important in stereo-TV productions because many people will listen to your

program in mono. For this reason, when miking with

a stereo pair of mics, use a mid-side stereo microphone or a coincident pair (Figure 21). The grille of

the left-aiming microphone is aligned vertically over

the grille of the right-aiming microphone. Since there

is no spacing between mics, there are no time or

phase cancellations to degrade the frequency response when the mics are summed to mono. The

Crown SASS stereo microphone is also mono compatible.

Fig. 21 – A coincident pair.

How to achieve a natural tone quality:

•Use a microphone with a flat frequency response,

such as a PZM-30D, GLM-100, CM-700, LM-300A,

or LM-201.

•Place the microphone as far from the sound source

as the source is big. For example, the sound board

of a guitar is about 18" long. Place the mic at least

18" away to pick up all the parts of the guitar about

equally.

•If you must mike close to reduce feedback or leak-

age, use your mixer’s EQ to restore a natural tonal

balance.

Recommendations for stereo TV productions:

Dialog that has a lot of stereo motion is distracting,

so record dialog in mono in the center or with a

narrow stereo spread. Record effects, audience reaction, and music in stereo. You can allow off-camera sounds to be imaged away from the TV screen

because the screen is considered a window on a

larger scene.

Often your microphone setup must be invisible oncamera.Use miniature microphones such as the

GLM-100 (omni), GLM-200 (hypercardioid), CM30 or CM-31 (supercardioid). You can hang these

over an orchestra or choir, mount them onto musical instruments, or hide them under clothing. A PZM

can be hidden under a table cloth.

10

Page 11

MICROPHONE ACCESSORIES

We’ve already mentioned microphone shock

mounts, windscreens, and pads. Some other useful accessories are described below:

Combiner

If you have more mics than inputs, a combiner

comes in handy. This resistor network mixes the

outputs of two or three mics into a single output.

Stereo bar

This device mounts two directional microphones

on a single mic stand for convenient stereo miking

(Figure 22), An example is the CM-SB.

Fig. 22 – A stereo bar.

Splitter

This is a box with one input for a microphone and

two or three isolated outputs that feed individual

mixers (Figure 23).

Fig. 23 – A splitter.

SPECIFIC TECHNIQUES

The soundtrack of most video productions has four

elements: narration, ambient or environmental

sound, sound effects, and music. Let’s look at

miking techniques for each of these.

Announcer

In these examples, we’ll assume it’s all right to see

the microphone on-camera.

•Clip a lavalier mic (such as the Crown GLM-100)

onto the announcer’s shirt about 8 inches below

the chin (Figure 24). Aim the front of the microphone at the mouth.

Fig. 24 – Using a lavalier mic.

You might use a splitter to feed one mic signal simultaneously to a sound-reinforcement mixer, recording mixer, and broadcast mixer.

To prevent ground loops and hum, only one mixer

should provide phantom power and ground. To do

this, you switch in the ground-lift switches on the

splitter to remove the grounds for the other mixers.

•Use a handheld omni dynamic.

•To reject background noise, try a handheld uni-di-

rectional dynamic, variable-D type, with a foam pop

filter. Place it close to the mouth.

•If the announcer is hard to hear because of loud

background noise (sirens, rock concert), try a CM310A Differoid® with lips touching the grille. The

CM-310A is a handheld cardioid microphone that

is noise-canceling or differential.

11

Page 12

“Differential” means it cancels sounds at a distance,

and “cardioid” means it cancels sounds from behind the microphone. Because of these abilities, the

CM-310A permits extreme isolation from background noise. When used as a stage vocal mic, it

provides extremely high gain-before-feedback.

To keep from canceling the announcer’s voice, the

microphone must be used with lips touching the

grille. Also, the announcer must talk directly into

the front of the microphone, not the side, or the

voice may get canceled and sound thin.

The Differoid is used by the Indianapolis 500 Speedway announcer who announces while sitting in the

stands. Even with the loudspeakers blaring in the

background, the Differoid rejects the sound of the

P.A., the cars, and the crowd.

and mix it with a closeup mic on the announcer (Figure 26, right side). This produces mono centered

dialog with stereo ambience.

Fig. 26– Two ways to pick up an announcer and

ambience with a SASS-MK11 stereo microphone.

In the studio, the announcer’s mic is often placed

about 8" away at eye level to prevent pops (Figure

25). A hoop-type pop filter also works quite well.

Fig. 25 – Placing an annuoncer’s mic to avoid breath

pops.

Announcer with ambience. If you want to pick up

the announcer along with ambient sound in stereo,

use a SASS microphone about 4 feet away (Figure

26, left side). For more flexibility in post production, use a SASS several feet away for ambience,

Dialog at a video shoot

In this case, you don’t want to see the microphone

on camera.

•Shotgun microphone. The most common choice

is a shock-mounted shotgun mic placed above the

actor and in front, as close as possible but just out

of the camera view.

•Lavalier microphone. To hide the microphone, at-

tach it under clothing. Since clothing can attenuate

high frequencies, boost the highs with your mixer

EQ until the sound is natural. Go wireless if the actor moves around a lot. The Crown GLM-100-E is

an omni lavalier without electronics, which you plug

into a wireless transmitter.

Ambience or environmental sound:

Try a stereo mic (Crown SASS-P MK11), or two

spaced omnis 25 feet apart (such as PZMs), or a

single omnidirectional mic for mono. The ambience

mic can be handheld, on a stand, on a camera hot

shoe, or on a Steadicam platform.

General Television Network used two PZMs in earspaced plexiglass pyramids to create the soundtrack

of an air show and a Muzzleloaders festival. Both

12

Page 13

these soundtracks won Emmys. The SASS was used

in the Indy 500 to pick up the audience and race

cars in stereo.

Interviews

For people seated at a table, try a PZM-6D in the

center of the table (Figure 27).

Fig. 27– Miking an interveiw with a PZM.

If you want to omit the handheld mic because it is

intimidating, try a PZM in your shirt pocket.

If background noise is excessive, try a handheld unidirectional dynamic microphone, variable-D design,

with a foam windscreen. Place it close to the mouth.

Group discussions

If the group is seated at a small table, try a PZM-6D

in the center of the table (Figure 29).

If the table is large, place a PCC-160 (Figure 30) or

Fig. 29– Miking a group discussion with a PZM.

For on-the-street interviews, if a handheld mic is

acceptable, use a handheld omni dynamic. Either

place it midway between the two people (Figure 28),

or hold it about 3 inches below the chin of the person speaking. Do not move the mic while talking,

or the level will vary.

Fig. 28– Miking an interview with a handheld mic.

PCC-170 on the table between every two people.

Run the mics through an automatic (gated) mixer

for the clearest sound.

If you don’t want to see mics on the table, try hang-

Fig. 30– Miking a group discussion with PCC microphones.

13

Page 14

ing a CM-30 or CM-31 miniature supercardioid mic

over the table, about 3 feet above the talkers’ heads

(Figure 31).

Try a PZM-6D on the wall near the group.

Fig. 31– Miking a group discussion with an overhead mic.

Basketball

A typical setup employs headset mics for the announcers mixed with a another mic aiming at the

crowd.To pick up the floor action, use a shotgun

mic operated by a person seated in the bleachers.

This person should follow the action with the shotgun mic.If you don’t want to use an operator, mount

a shotgun microphone on each backboard support,

aiming at the action on the floor.Try one or two PCC160s just outside the court. To pick up backboard

sounds, tape a PZM-30D on the backboard just below the hoop.

Golf, bowling

Place PZMs on the grass or near the pins.

Speeches at a lectern

For permanent installations, use a slim gooseneck

mic such as the Crown LM-201 or LM-300 (Figure

32). Place the included foam pop filter on the microphone, leaving an airspace between the pop

filter and the microphone grille.

Use a lavalier mic (GLM-100) on each participant.

Consider running the mics through an automatic

(gated) mixer for clearer sound.

Audience:

To pick up questions in the audience, try a shotgun

mic aimed by an operator.

For a clearer pickup of questions, use a handheld

wireless mic. Have an assistant hand the mic to each

person who wants to ask a question.

Try hanging several cardioid mics over the audience.

To record audience reaction, try a single stereo mic

such as the Crown SASS-PMK11. Or try a PZM on

a 2-foot-square plexiglass panel.

Fig. 32– A lectern microphone.

For temporary setups, place a cardioid mic (Crown

CM-700) on a boom stand 8" away from the talker’s

mouth (Figure 32). Place a foam pop filter on the

mic. If necessary, use a splitter to feed the mic signal to the P.A. mixer and the broadcast mixer.

14

Page 15

Fig. 33– Miking a speech.

Fig. 34– Miking a theater stage floor.

Sound effects

To record sound effects on location, use a stereo

mic to accurately track the motion, not a spaced

pair of mics. With the spaced pair, sounds may jump

from speaker to speaker as the sound source moves.

Audio people at the Indy 500 used a SASS to record

a promo for the Dodge Viper pace car. Movies such

as

Days of Thunder

ployed the SASS for sound-effects pickup.

and

Hunt for Red October

em-

Parade

•Use a mid-side shotgun microphone.

•Use a Crown SASS-P MK11.

•Try a PCC-160 on either side of plexiglass panel

over the street. Cover the panel with silk to reduce

wind noise.

•Try a PZM-30D on a 2-foot-square plexiglass panel.

Again, cover the panel with silk.

Wedding

Place one or two PZM-30Ds on the floor near the

minister. Two PZMs on the floor can pick up the

musicians who play at the reception.

Theater

Place two or three PCC-160 supercardioid boundary mics on the stage floor a few feet from the front

edge (Figure 34). For maximum gain-before-feedback and clarity, turn up only the microphone nearest the person talking.

Security and surveillance

A microphone designed for this purpose is the

Crown PZM-11. It can be mounted in the ceiling or

wall in a standard electrical outlet box. The PZM-11

is designed to look like a light switch so as not to

draw attention.

Use it in factories, jailhouses, classrooms, subway

platforms, military installations. Put it anywhere

there’s a need to listen for intruders, listen for people

in trouble, monitor conversations, or monitor machinery noise.

Musical applications

See the Crown

Microphone Application

Guide,Microphone Application Guide for Studio

Recording,

Application Guide

Crown dealer.

and the Crown

, available free from Crown or your

Boundary Microphone

15

Loading...

Loading...