Page 1

Sun VirtualBox

User Manual

Version 3.1.0_BETA2

c

2004-2009 Sun Microsystems, Inc.

http://www.virtualbox.org

R

Page 2

Contents

1 First steps 9

1.1 Why is virtualization useful? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

1.2 Some terminology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

1.3 Features overview . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

1.4 Supported host operating systems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

1.5 Installing and starting VirtualBox . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

1.6 Creating your first virtual machine . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

1.7 Running your virtual machine . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

1.7.1 Keyboard and mouse support in virtual machines . . . . . . . . . 21

1.7.2 Changing removable media . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

1.7.3 Saving the state of the machine . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

1.8 Snapshots . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

1.9 Virtual machine configuration . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

1.10 Deleting virtual machines . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

1.11 Importing and exporting virtual machines . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

2 Installation details 32

2.1 Installing on Windows hosts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

2.1.1 Prerequisites . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

2.1.2 Performing the installation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

2.1.3 Uninstallation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

2.1.4 Unattended installation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

2.2 Installing on Mac OS X hosts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

2.2.1 Performing the installation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

2.2.2 Uninstallation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

2.2.3 Unattended installation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

2.3 Installing on Linux hosts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

2.3.1 Prerequisites . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

2.3.2 The VirtualBox kernel module . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

2.3.3 USB and advanced networking support . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

2.3.4 Performing the installation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

2.3.5 Starting VirtualBox on Linux . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

2.4 Installing on Solaris hosts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

2.4.1 Performing the installation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

2.4.2 Starting VirtualBox on Solaris . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42

2.4.3 Uninstallation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42

2.4.4 Unattended installation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42

2

Page 3

Contents

2.4.5 Configuring a zone for running VirtualBox . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

3 Configuring virtual machines 44

3.1 Supported guest operating systems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

3.2 64-bit guests . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

3.3 General settings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

3.3.1 “Basic” tab . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

3.3.2 “Advanced” tab . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

3.3.3 “Description” tab . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

3.4 System settings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

3.4.1 “Motherboard” tab . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

3.4.2 “Processor” tab . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

3.4.3 “Acceleration” tab: hardware vs. software virtualization . . . . . 49

3.5 Display settings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

3.6 Storage settings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

3.7 Audio settings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54

3.8 Network settings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54

3.9 Serial ports . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55

3.10 USB support . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56

3.10.1 USB settings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56

3.10.2 Implementation notes for Windows and Linux hosts . . . . . . . 58

3.11 Shared folders . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58

3.12 Alternative firmware (EFI) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58

4 Guest Additions 60

4.1 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 60

4.2 Versions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61

4.3 Windows Guest Additions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 62

4.3.1 Installing the Windows Guest Additions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 62

4.3.2 Updating the Windows Guest Additions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63

4.3.3 Unattended Installation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 64

4.3.4 Manual file extraction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 64

4.3.5 Windows Vista networking . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 64

4.4 Linux Guest Additions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65

4.4.1 Installing the Linux Guest Additions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65

4.4.2 Video acceleration and high resolution graphics modes . . . . . 66

4.4.3 Updating the Linux Guest Additions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 67

4.5 Solaris Guest Additions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 67

4.5.1 Installing the Solaris Guest Additions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 67

4.5.2 Uninstalling the Solaris Guest Additions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68

4.5.3 Updating the Solaris Guest Additions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68

4.6 OS/2 Guest Additions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68

4.7 Folder sharing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68

4.8 Seamless windows . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71

4.9 Hardware 3D acceleration (OpenGL and Direct3D 8/9) . . . . . . . . . 72

3

Page 4

Contents

4.10 Hardware 2D video acceleration for Windows guests . . . . . . . . . . . 73

4.11 Guest properties . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73

5 Virtual storage 76

5.1 Hard disk controllers: IDE, SATA (AHCI), SCSI . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 76

5.2 Disk image files (VDI, VMDK, VHD, HDD) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79

5.3 The Virtual Media Manager . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 80

5.4 Special image write modes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 81

5.5 Differencing images . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 83

5.6 Cloning disk images . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 85

5.7 Writing CDs and DVDs using the host drive . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 85

5.8 iSCSI servers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 86

5.8.1 Access iSCSI targets via Internal Networking . . . . . . . . . . . 86

6 Virtual networking 88

6.1 Virtual networking hardware . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 88

6.2 Introduction to networking modes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89

6.3 Network Address Translation (NAT) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 90

6.3.1 Configuring port forwarding with NAT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 90

6.3.2 PXE booting with NAT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91

6.3.3 NAT limitations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91

6.4 Bridged networking . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 92

6.5 Internal networking . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93

6.6 Host-only networking . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 94

7 Alternative front-ends; remote virtual machines 96

7.1 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 96

7.2 Using VBoxManage to control virtual machines . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 97

7.3 VBoxSDL, the simplified VM displayer . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 98

7.4 Remote virtual machines (VRDP support) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 99

7.4.1 Common third-party RDP viewers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100

7.4.2 VBoxHeadless, the VRDP-only server . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 101

7.4.3 Step by step: creating a virtual machine on a headless server . . 102

7.4.4 Remote USB . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103

7.4.5 RDP authentication . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 104

7.4.6 RDP encryption . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 105

7.4.7 VRDP multiple connections . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 105

8 VBoxManage reference 106

8.1 VBoxManage list . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 111

8.2 VBoxManage showvminfo . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 112

8.3 VBoxManage registervm / unregistervm . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 113

8.4 VBoxManage createvm . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 113

8.5 VBoxManage modifyvm . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 114

8.5.1 General settings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 114

4

Page 5

Contents

8.5.2 Networking settings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 116

8.5.3 Serial port, audio, clipboard, VRDP and USB settings . . . . . . 117

8.6 VBoxManage import . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 118

8.7 VBoxManage export . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 120

8.8 VBoxManage startvm . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 120

8.9 VBoxManage controlvm . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 121

8.10 VBoxManage discardstate . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 122

8.11 VBoxManage snapshot . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 122

8.12 VBoxManage openmedium / closemedium . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 123

8.13 VBoxManage storagectl / storageattach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 123

8.13.1 VBoxManage storagectl . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 124

8.13.2 VBoxManage storageattach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 124

8.14 VBoxManage showhdinfo . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 125

8.15 VBoxManage createhd . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 125

8.16 VBoxManage modifyhd . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 126

8.17 VBoxManage clonehd . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 127

8.18 VBoxManage convertfromraw . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 127

8.19 VBoxManage addiscsidisk . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 128

8.20 VBoxManage getextradata/setextradata . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 129

8.21 VBoxManage setproperty . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 130

8.22 VBoxManage usbfilter add/modify/remove . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 130

8.23 VBoxManage sharedfolder add/remove . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 131

8.24 VBoxManage metrics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 131

8.25 VBoxManage guestproperty . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 132

8.26 VBoxManage dhcpserver . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 133

9 Advanced topics 135

9.1 VirtualBox configuration data . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 135

9.2 Automated Windows guest logons . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 137

9.3 Automated Windows system preparation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 138

9.4 Custom external VRDP authentication . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 139

9.5 Secure labeling with VBoxSDL . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 141

9.6 Custom VESA resolutions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 142

9.7 Multiple monitors for the guest . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 143

9.8 Releasing modifiers with VBoxSDL on Linux . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 143

9.9 Launching more than 120 VMs on Solaris hosts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 144

9.10 Using serial ports . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 144

9.11 Using a raw host hard disk from a guest . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 145

9.11.1 Access to entire physical hard disk . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 145

9.11.2 Access to individual physical hard disk partitions . . . . . . . . . 146

9.12 Allowing a virtual machine to start even with unavailable CD/DVD/floppy

devices . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 148

9.13 Fine-tuning the VirtualBox NAT engine . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 148

9.13.1 Configuring the address of a NAT network interface . . . . . . . 148

5

Page 6

Contents

9.13.2 Configuring the boot server (next server) of a NAT network in-

terface . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 149

9.13.3 Tuning TCP/IP buffers for NAT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 149

9.13.4 Binding NAT sockets to a specific interface . . . . . . . . . . . . 149

9.13.5 Enabling DNS proxy in NAT mode . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 150

9.13.6 Using the host’s resolver as a DNS proxy in NAT mode . . . . . . 150

9.14 Configuring the maximum resolution of guests when using the graphi-

cal frontend . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 150

9.15 Configuring the BIOS DMI information . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 151

9.16 Configuring the guest time stamp counter (TSC) to reflect guest execution152

9.17 Configuring the hard disk vendor product data (VPD) . . . . . . . . . . 152

10 VirtualBox programming interfaces 154

11 Troubleshooting 155

11.1 General . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 155

11.1.1 Collecting debugging information . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 155

11.1.2 Guest shows IDE/SATA errors for file-based images on slow host

file system . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 155

11.1.3 Responding to guest IDE/SATA flush requests . . . . . . . . . . . 156

11.2 Windows guests . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 157

11.2.1 Windows bluescreens after changing VM configuration . . . . . 157

11.2.2 Windows 0x101 bluescreens with SMP enabled (IPI timeout) . . 157

11.2.3 Windows 2000 installation failures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 157

11.2.4 How to record bluescreen information from Windows guests . . 158

11.2.5 No networking in Windows Vista guests . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 158

11.2.6 Windows guests may cause a high CPU load . . . . . . . . . . . 158

11.3 Linux and X11 guests . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 159

11.3.1 Linux guests may cause a high CPU load . . . . . . . . . . . . . 159

11.3.2 AMD Barcelona CPUs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 159

11.3.3 Buggy Linux 2.6 kernel versions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 159

11.3.4 Shared clipboard, auto-resizing and seamless desktop in X11

guests . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 159

11.4 Windows hosts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 160

11.4.1 VBoxSVC out-of-process COM server issues . . . . . . . . . . . . 160

11.4.2 CD/DVD changes not recognized . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 160

11.4.3 Sluggish response when using Microsoft RDP client . . . . . . . 161

11.4.4 Running an iSCSI initiator and target on a single system . . . . . 161

11.5 Linux hosts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 162

11.5.1 Linux kernel module refuses to load . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 162

11.5.2 Linux host CD/DVD drive not found . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 162

11.5.3 Linux host CD/DVD drive not found (older distributions) . . . . 162

11.5.4 Linux host floppy not found . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 163

11.5.5 Strange guest IDE error messages when writing to CD/DVD . . . 163

11.5.6 VBoxSVC IPC issues . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 163

6

Page 7

Contents

11.5.7 USB not working . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 164

11.5.8 PAX/grsec kernels . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 165

11.5.9 Linux kernel vmalloc pool exhausted . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 165

11.6 Solaris hosts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 165

11.6.1 Cannot start VM, not enough contiguous memory . . . . . . . . 165

11.6.2 VM aborts with out of memory errors on Solaris 10 hosts . . . . 166

12 Change log 167

12.1 Version 3.1.0 Beta 2 (2009-11-19) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 167

12.2 Version 3.0.12 (2009-11-10) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 169

12.3 Version 3.0.10 (2009-10-29) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 170

12.4 Version 3.0.8 (2009-10-02) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 171

12.5 Version 3.0.6 (2009-09-09) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 173

12.6 Version 3.0.4 (2009-08-04) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 176

12.7 Version 3.0.2 (2009-07-10) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 177

12.8 Version 3.0.0 (2009-06-30) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 179

12.9 Version 2.2.4 (2009-05-29) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 182

12.10Version 2.2.2 (2009-04-27) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 183

12.11Version 2.2.0 (2009-04-08) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 185

12.12Version 2.1.4 (2009-02-16) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 188

12.13Version 2.1.2 (2009-01-21) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 190

12.14Version 2.1.0 (2008-12-17) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 194

12.15Version 2.0.8 (2009-03-10) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 196

12.16Version 2.0.6 (2008-11-21) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 197

12.17Version 2.0.4 (2008-10-24) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 198

12.18Version 2.0.2 (2008-09-12) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 199

12.19Version 2.0.0 (2008-09-04) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 201

12.20Version 1.6.6 (2008-08-26) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 202

12.21Version 1.6.4 (2008-07-30) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 204

12.22Version 1.6.2 (2008-05-28) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 205

12.23Version 1.6.0 (2008-04-30) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 207

12.24Version 1.5.6 (2008-02-19) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 209

12.25Version 1.5.4 (2007-12-29) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 211

12.26Version 1.5.2 (2007-10-18) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 213

12.27Version 1.5.0 (2007-08-31) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 215

12.28Version 1.4.0 (2007-06-06) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 218

12.29Version 1.3.8 (2007-03-14) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 221

12.30Version 1.3.6 (2007-02-20) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 222

12.31Version 1.3.4 (2007-02-12) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 223

12.32Version 1.3.2 (2007-01-15) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 224

12.33Version 1.2.4 (2006-11-16) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 225

12.34Version 1.2.2 (2006-11-14) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 225

12.35Version 1.1.12 (2006-11-14) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 226

12.36Version 1.1.10 (2006-07-28) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 227

12.37Version 1.1.8 (2006-07-17) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 227

7

Page 8

Contents

12.38Version 1.1.6 (2006-04-18) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 228

12.39Version 1.1.4 (2006-03-09) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 228

12.40Version 1.1.2 (2006-02-03) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 229

12.41Version 1.0.50 (2005-12-16) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 231

12.42Version 1.0.48 (2005-11-23) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 231

12.43Version 1.0.46 (2005-11-04) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 232

12.44Version 1.0.44 (2005-10-25) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 232

12.45Version 1.0.42 (2005-08-30) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 233

12.46Version 1.0.40 (2005-06-17) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 234

12.47Version 1.0.39 (2005-05-05) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 235

12.48Version 1.0.38 (2005-04-27) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 235

12.49Version 1.0.37 (2005-04-12) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 236

13 Known limitations 237

14 Third-party licenses 240

14.1 Materials . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 240

14.2 Licenses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 242

14.2.1 GNU General Public License (GPL) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 242

14.2.2 GNU Lesser General Public License (LGPL) . . . . . . . . . . . . 247

14.2.3 Mozilla Public License (MPL) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 254

14.2.4 MIT License . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 261

14.2.5 X Consortium License (X11) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 262

14.2.6 zlib license . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 262

14.2.7 OpenSSL license . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 262

14.2.8 Slirp license . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 263

14.2.9 liblzf license . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 264

14.2.10libpng license . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 264

14.2.11lwIP license . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 265

14.2.12libxml license . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 265

14.2.13libxslt licenses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 266

14.2.14gSOAP Public License Version 1.3a . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 267

14.2.15Chromium licenses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 273

14.2.16curl license . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 276

15 VirtualBox privacy policy 277

Glossary 279

8

Page 9

1 First steps

Welcome to Sun VirtualBox!

VirtualBox is a cross-platform virtualization application. What does that mean? For

one thing, it installs on your existing Intel or AMD-based computers, whether they are

running Windows, Mac, Linux or Solaris operating systems. Secondly, it extends the

capabilities of your existing computer so that it can run multiple operating systems

(inside multiple virtual machines) at the same time. So, for example, you can run

Windows and Linux on your Mac, run Windows Server 2008 on your Linux server, run

Linux on your Windows PC, and so on, all alongside your existing applications. You

can install and run as many virtual machines as you like – the only practical limits are

disk space and memory.

VirtualBox is deceptively simple yet also very powerful. It can run everywhere from

small embedded systems or desktop class machines all the way up to datacenter deployments and even Cloud environments.

The following screenshot shows you how VirtualBox, installed on a Linux machine,

is running Windows 7 in a virtual machine window:

In this User Manual, we’ll begin simply with a quick introduction to virtualization

and how to get your first virtual machine running with the easy-to-use VirtualBox

graphical user interface. Subsequent chapters will go into much more detail covering

more powerful tools and features, but fortunately, it is not necessary to read the entire

User Manual before you can use VirtualBox.

9

Page 10

1 First steps

You can find a summary of VirtualBox’s capabilities in chapter 1.3, Features overview,

page 12. For existing VirtualBox users who just want to see what’s new in this release,

there is a detailed list in chapter 12, Change log, page 167.

1.1 Why is virtualization useful?

The techniques and features that VirtualBox provides are useful for several scenarios:

• Operating system support. With VirtualBox, one can run software written for

one operating system on another (for example, Windows software on Linux or

a Mac) without having to reboot to use it. Since you can configure what kinds

of hardware should be presented to each virtual machine, you can even install

an old operating system such as DOS or OS/2 in a virtual machine if your real

computer’s hardware is no longer supported by that operating system.

• Testing and disaster recovery. Once installed, a virtual machine and its virtual

hard disks can be considered a “container” that can be arbitrarily frozen, woken

up, copied, backed up, and transported between hosts.

On top of that, with the use of another VirtualBox feature called “snapshots”,

one can save a particular state of a virtual machine and revert back to that state,

if necessary. This way, one can freely experiment with a computing environment.

If something goes wrong (e.g. after installing misbehaving software or infecting

the guest with a virus), one can easily switch back to a previous snapshot and

avoid the need of frequent backups and restores.

Any number of snapshots can be created, allowing you to travel back and forward in virtual machine time.

• Infrastructure consolidation. Virtualization can significantly reduce hardware

and electricity costs. Servers today typically run with fairly average low system

loads and are rarely used to their full potential. A lot of hardware potential as

well as electricity is thereby wasted. So, instead of running many such physical

computers that are only partially used, one can pack many virtual machines onto

a few powerful hosts and balance the loads between them.

With VirtualBox, you can even run virtual machines as mere servers for the

VirtualBox Remote Desktop Protocol (VRDP), with full client USB support. This

allows for consolidating the desktop machines in an enterprise on just a few RDP

servers, while the actual clients only have to be capable of displaying VRDP data.

• Easier software installations. Virtual machines can be used by software ven-

dors to ship entire software configurations. For example, installing a complete

mail server solution on a real machine can be a tedious task. With virtualization

it becomes possible to ship an entire software solution, possibly consisting of

many different components, in a virtual machine, which is then often called an

“appliance”. Installing and running a mail server becomes as easy as importing

such an appliance into VirtualBox.

10

Page 11

1 First steps

1.2 Some terminology

When dealing with virtualization (and also for understanding the following chapters

of this documentation), it helps to acquaint oneself with a bit of crucial terminology,

especially the following terms:

Host operating system (host OS): the operating system of the physical computer

on which VirtualBox was installed. There are versions of VirtualBox for Windows, Mac OS X, Linux and Solaris hosts; for details, please see chapter 1.4,

Supported host operating systems, page 14. While the various VirtualBox versions

are usually discussed together in this document, there may be platform-specific

differences which we will point out where appropriate.

Guest operating system (guest OS): the operating system that is running inside

the virtual machine. Theoretically, VirtualBox can run any x86 operating system (DOS, Windows, OS/2, FreeBSD, OpenBSD), but to achieve near-native

performance of the guest code on your machine, we had to go through a lot

of optimizations that are specific to certain operating systems. So while your

favorite operating system may run as a guest, we officially support and optimize

for a select few (which, however, include the most common ones).

See chapter 3.1, Supported guest operating systems, page 44 for details.

Virtual machine (VM). When running, a VM is the special environment that

VirtualBox creates for your guest operating system. So, in other words, you

run your guest operating system “in” a VM. Normally, a VM will be shown as

a window on your computer’s desktop, but depending on which of the various frontends of VirtualBox you use, it can be displayed in full-screen mode or

remotely by use of the VirtualBox Remote Desktop Protocol (VRDP).

Sometimes we also use the term “virtual machine” in a more abstract way. Internally, VirtualBox thinks of a VM as a set of parameters that determine its behavior. They include hardware settings (how much memory the VM should have,

what hard disks VirtualBox should virtualize through which container files, what

CD-ROMs are mounted etc.) as well as state information (whether the VM is

currently running, saved, its snapshots etc.).

These settings are mirrored in the VirtualBox graphical user interface as well as

the VBoxManage command line program; see chapter 8, VBoxManage reference,

page 106. In other words, a VM is also what you can see in its settings dialog.

Guest Additions. With “Guest Additions”, we refer to special software packages that

are shipped with VirtualBox. Even though they are part of VirtualBox, they are

designed to be installed inside a VM to improve performance of the guest OS and

to add extra features. This is described in detail in chapter 4, Guest Additions,

page 60.

11

Page 12

1 First steps

1.3 Features overview

Here’s a brief outline of VirtualBox’s main features:

• Portability. VirtualBox runs on a large number of 32-bit and 64-bit host oper-

ating systems (again, see chapter 1.4, Supported host operating systems, page 14

for details).

To a very large degree, VirtualBox is functionally identical on all of the host

platforms, and the same file and image formats are used. This allows you to

run virtual machines created on one host on another host with a different host

operating system; for example, you can create a virtual machine on Windows

and then run it under Linux.

In addition, virtual machines can easily be imported and exported using the

Open Virtualization Format (OVF, see chapter 1.11, Importing and exporting vir-

tual machines, page 29), an industry standard created for this purpose. You can

even import OVFs that were created with a different virtualization software.

• No hardware virtualization required. For many scenarios, VirtualBox does

not require the processor features built into newer hardware like Intel VT-x or

AMD-V. As opposed to many other virtualization solutions, you can therefore use

VirtualBox even on older hardware where these features are not present. More

details can be found in chapter 3.4.3, “Acceleration” tab: hardware vs. software

virtualization, page 49.

• Guest Additions: shared folders, seamless windows, 3D virtualization. The

VirtualBox Guest Additions are software packages which can be installed inside

of supported guest systems to improve their performance and to provide additional integration and communication with the host system. After installing the

Guest Additions, a virtual machine will support automatic adjustment of video

resolutions, seamless windows, accelerated 3D graphics and more. The Guest

Additions are described in detail in chapter 4, Guest Additions, page 60.

In particular, Guest Additions provide for “shared folders”, which let you access

files from the host system from within a guest machine. Shared folders are

described in chapter 4.7, Folder sharing, page 68.

• Great hardware support. Among others, VirtualBox supports:

– Guest multiprocessing (SMP). VirtualBox can present up to 32 virtual

CPUs to a virtual machine, irrespective of how many CPU cores are actually

present in your host.

– USB 2.0 device support. VirtualBox implements a virtual USB controller

and allows you to connect arbitrary USB devices to your virtual machines

without having to install device-specific drivers on the host. USB support

is not limited to certain device categories. For details, see chapter 3.10.1,

USB settings, page 56.

12

Page 13

1 First steps

– Hardware compatibility. VirtualBox virtualizes a vast array of virtual de-

vices, among them many devices that are typically provided by other virtualization platforms. That includes IDE, SCSI and SATA hard disk controllers,

several virtual network cards and sound cards, virtual serial and parallel

ports and an Input/Output Advanced Programmable Interrupt Controller

(I/O APIC), which is found in many modern PC systems. This eases cloning

of PC images from real machines and importing of third-party virtual machines into VirtualBox.

– Full ACPI support. The Advanced Configuration and Power Interface

(ACPI) is fully supported by VirtualBox. This eases cloning of PC images

from real machines or third-party virtual machines into VirtualBox. With its

unique ACPI power status support, VirtualBox can even report to ACPIaware guest operating systems the power status of the host. For mobile

systems running on battery, the guest can thus enable energy saving and

notify the user of the remaining power (e.g. in fullscreen modes).

– Multiscreen resolutions. VirtualBox virtual machines support screen res-

olutions many times that of a physical screen, allowing them to be spread

over a large number of screens attached to the host system.

– Built-in iSCSI support. This unique feature allows you to connect a vir-

tual machine directly to an iSCSI storage server without going through the

host system. The VM accesses the iSCSI target directly without the extra

overhead that is required for virtualizing hard disks in container files. For

details, see chapter 5.8, iSCSI servers, page 86.

– PXE Network boot. The integrated virtual network cards of VirtualBox

fully support remote booting via the Preboot Execution Environment (PXE).

• Multigeneration branched snapshots. VirtualBox can save arbitrary snapshots

of the state of the virtual machine. You can go back in time and revert the virtual

machine to any such snapshot and start an alternative VM configuration from

there, effectively creating a whole snapshot tree. For details, see chapter 1.8,

Snapshots, page 25.

• Clean architecture; unprecedented modularity. VirtualBox has an extremely

modular design with well-defined internal programming interfaces and a clean

separation of client and server code. This makes it easy to control it from several

interfaces at once: for example, you can start a VM simply by clicking on a

button in the VirtualBox graphical user interface and then control that machine

from the command line, or even remotely. See chapter 7, Alternative front-ends;

remote virtual machines, page 96 for details.

Due to its modular architecture, VirtualBox can also expose its full functionality

and configurability through a comprehensive software development kit (SDK),

which allows for integrating every aspect of VirtualBox with other software systems. Please see chapter 10, VirtualBox programming interfaces, page 154 for

details.

13

Page 14

1 First steps

• Remote machine display. You can run any virtual machine in a special

VirtualBox program that acts as a server for the VirtualBox Remote Desktop Protocol (VRDP), a backward-compatible extension of the standard Remote Desktop Protocol. With this unique feature, VirtualBox provides high-performance

remote access to any virtual machine.

VirtualBox’s VRDP support does not rely on the RDP server that is built into

Microsoft Windows. Instead, a custom VRDP server has been built directly into

the virtualization layer. As a result, it works with any operating system (even

in text mode) and does not require application support in the virtual machine

either.

VRDP support is described in detail in chapter 7.4, Remote virtual machines

(VRDP support), page 99.

On top of this special capacity, VirtualBox offers you more unique features:

– Extensible RDP authentication. VirtualBox already supports Winlogon

on Windows and PAM on Linux for RDP authentication. In addition, it

includes an easy-to-use SDK which allows you to create arbitrary interfaces

for other methods of authentication; see chapter 9.4, Custom external VRDP

authentication, page 139 for details.

– USB over RDP. Via RDP virtual channel support, VirtualBox also allows

you to connect arbitrary USB devices locally to a virtual machine which is

running remotely on a VirtualBox RDP server; see chapter 7.4.4, Remote

USB, page 103 for details.

1.4 Supported host operating systems

Currently, VirtualBox runs on the following host operating systems:

• Windows hosts:

– Windows XP, all service packs (32-bit)

– Windows Server 2003 (32-bit)

– Windows Vista (32-bit and 64-bit1).

– Windows Server 2008 (32-bit and 64-bit)

– Windows 7 (32-bit and 64-bit)

• Mac OS X hosts:

– 10.5 (Leopard, 32-bit)

1

Support for 64-bit Windows was added with VirtualBox 1.5.

2

Preliminary Mac OS X support (beta stage) was added with VirtualBox 1.4, full support with 1.6. Mac OS

X 10.4 (Tiger) support was removed with VirtualBox 3.1.

2

14

Page 15

1 First steps

– 10.6 (Snow Leopard, 32-bit and 64-bit)

Intel hardware is required; please see chapter 13, Known limitations, page 237

also.

• Linux hosts (32-bit and 64-bit3). Among others, this includes:

– Debian GNU/Linux 3.1 (“sarge”), 4.0 (“etch”) and 5.0 (“lenny”)

– Fedora Core 4 to 11

– Gentoo Linux

– Redhat Enterprise Linux 4 and 5

– SUSE Linux 9 and 10, openSUSE 10.3, 11.0 and 11.1

– Ubuntu 6.06 (“Dapper Drake”), 6.10 (“Edgy Eft”), 7.04 (“Feisty Fawn”),

7.10 (“Gutsy Gibbon”), 8.04 (“Hardy Heron”), 8.10 (“Intrepid Ibex”), 9.04

(“Jaunty Jackalope”).

– Mandriva 2007.1, 2008.0 and 2009.1

It should be possible to use VirtualBox on most systems based on Linux kernel

2.6 using either the VirtualBox installer or by doing a manual installation; see

chapter 2.3, Installing on Linux hosts, page 34.

Note that starting with VirtualBox 2.1, Linux 2.4-based host operating systems

are no longer supported.

• Solaris hosts (32-bit and 64-bit4) are supported with the restrictions listed in

chapter 13, Known limitations, page 237:

– OpenSolaris (2008.05 and higher, “Nevada” build 86 and higher)

– Solaris 10 (u5 and higher)

1.5 Installing and starting VirtualBox

VirtualBox comes in many different packages, and installation depends on your host

platform. If you have installed software before, installation should be straightforward

as on each host platform, VirtualBox uses the installation method that is most common

and easy to use. If you run into trouble or have special requirements, please refer

to chapter 2, Installation details, page 32 for details about the various installation

methods.

After installation, you can start VirtualBox as follows:

• On a Windows host, in the standard “Programs” menu, click on the item in the

“VirtualBox” group. On Vista or Windows 7, you can also type “VirtualBox” in

the search box of the “Start” menu.

3

Support for 64-bit Linux was added with VirtualBox 1.4.

4

Support for OpenSolaris was added with VirtualBox 1.6.

15

Page 16

1 First steps

• On a Mac OS X host, in the Finder, double-click on the “VirtualBox” item in the

“Applications” folder. (You may want to drag this item onto your Dock.)

• On a Linux or Solaris host, depending on your desktop environment, a

“VirtualBox” item may have been placed in either the “System” or “System Tools”

group of your “Applications” menu. Alternatively, you can type VirtualBox in

a terminal.

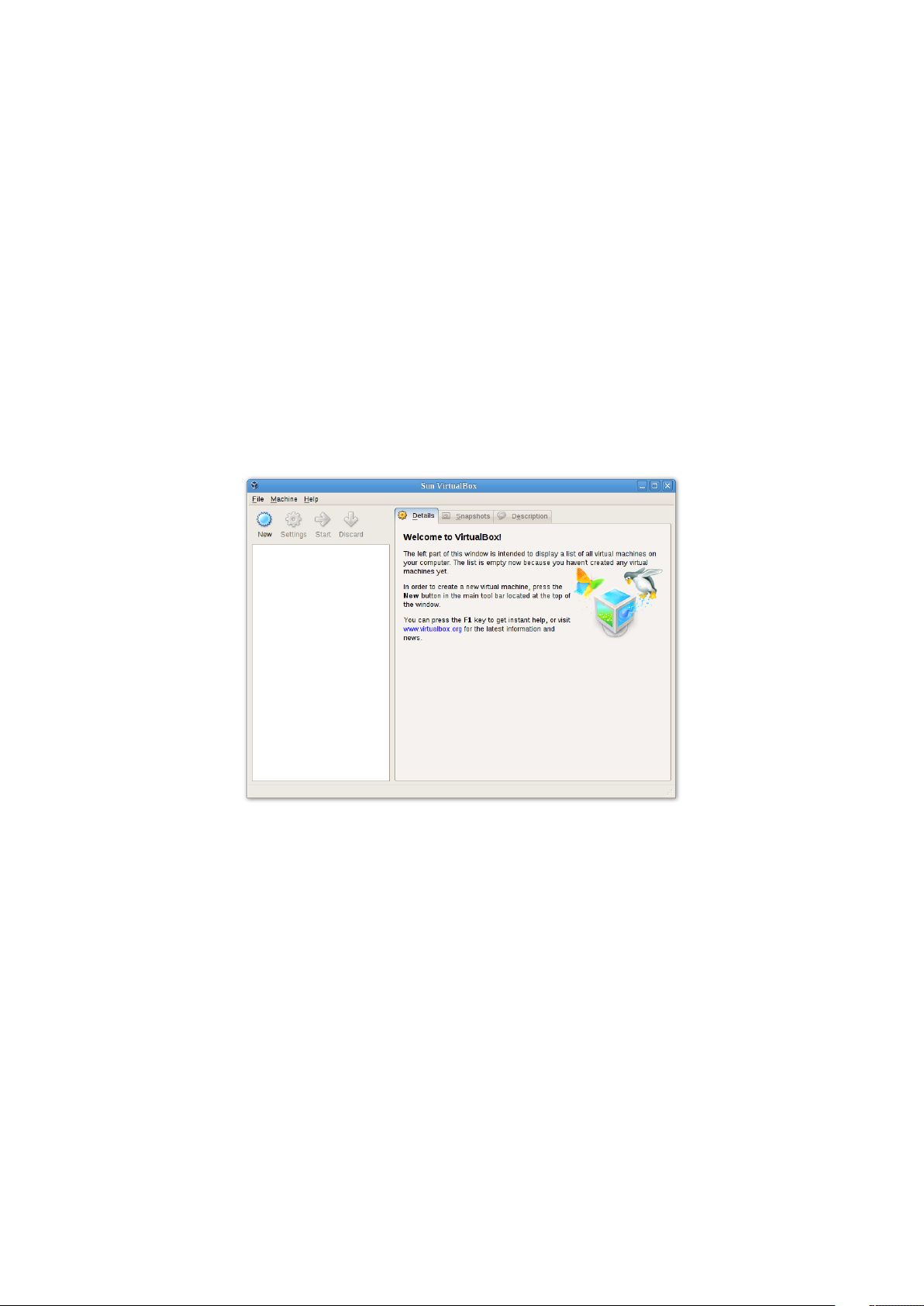

When you start VirtualBox for the first time, a window like the following should

come up:

On the left, you can see a pane that will later list all your virtual machines. Since

you have not created any, the list is empty. A row of buttons above it allows you to

create new VMs and work on existing VMs, once you have some. The pane on the

right displays the properties of the virtual machine currently selected, if any. Again,

since you don’t have any machines yet, the pane displays a welcome message.

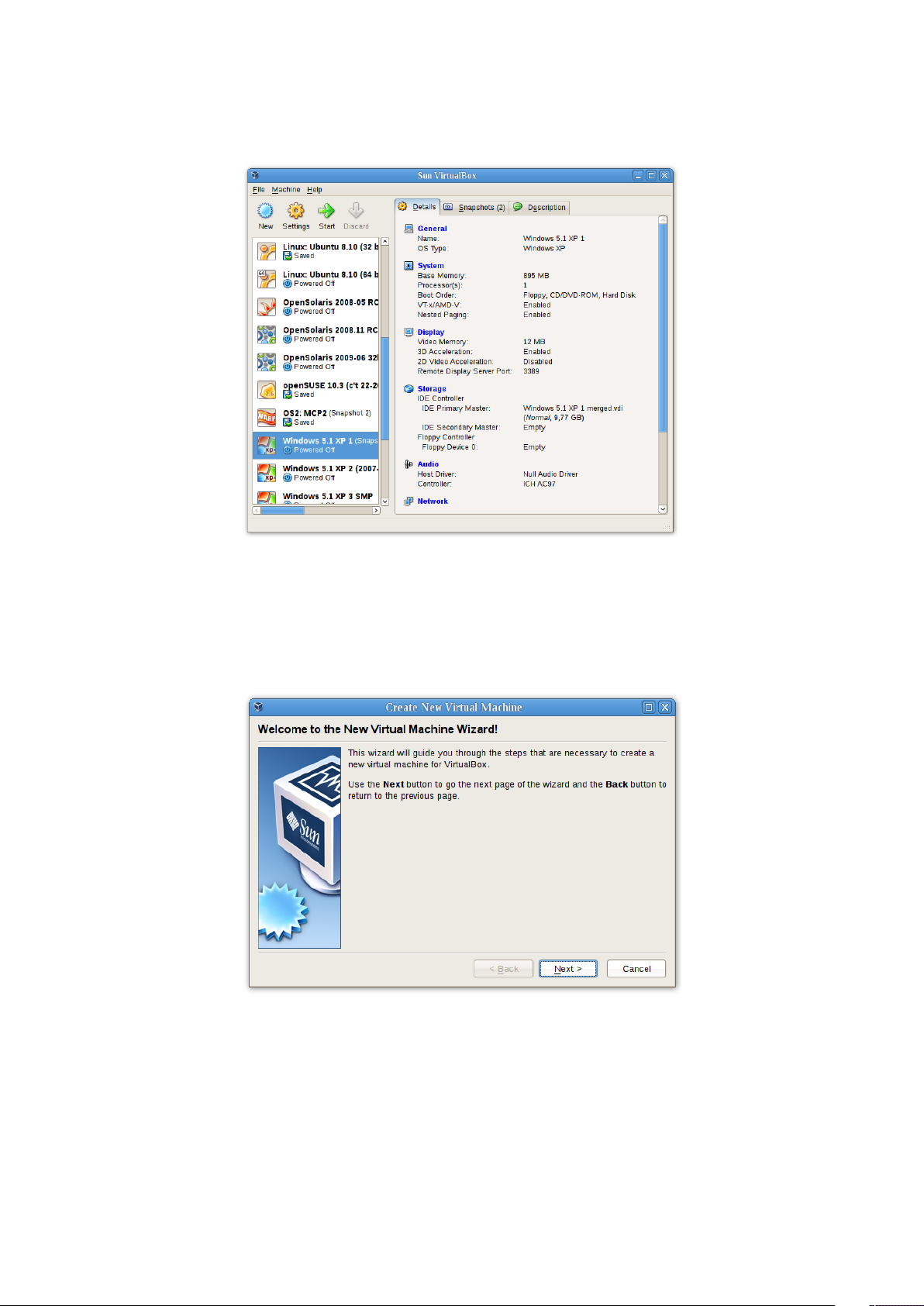

To give you an idea what VirtualBox might look like later, after you have created

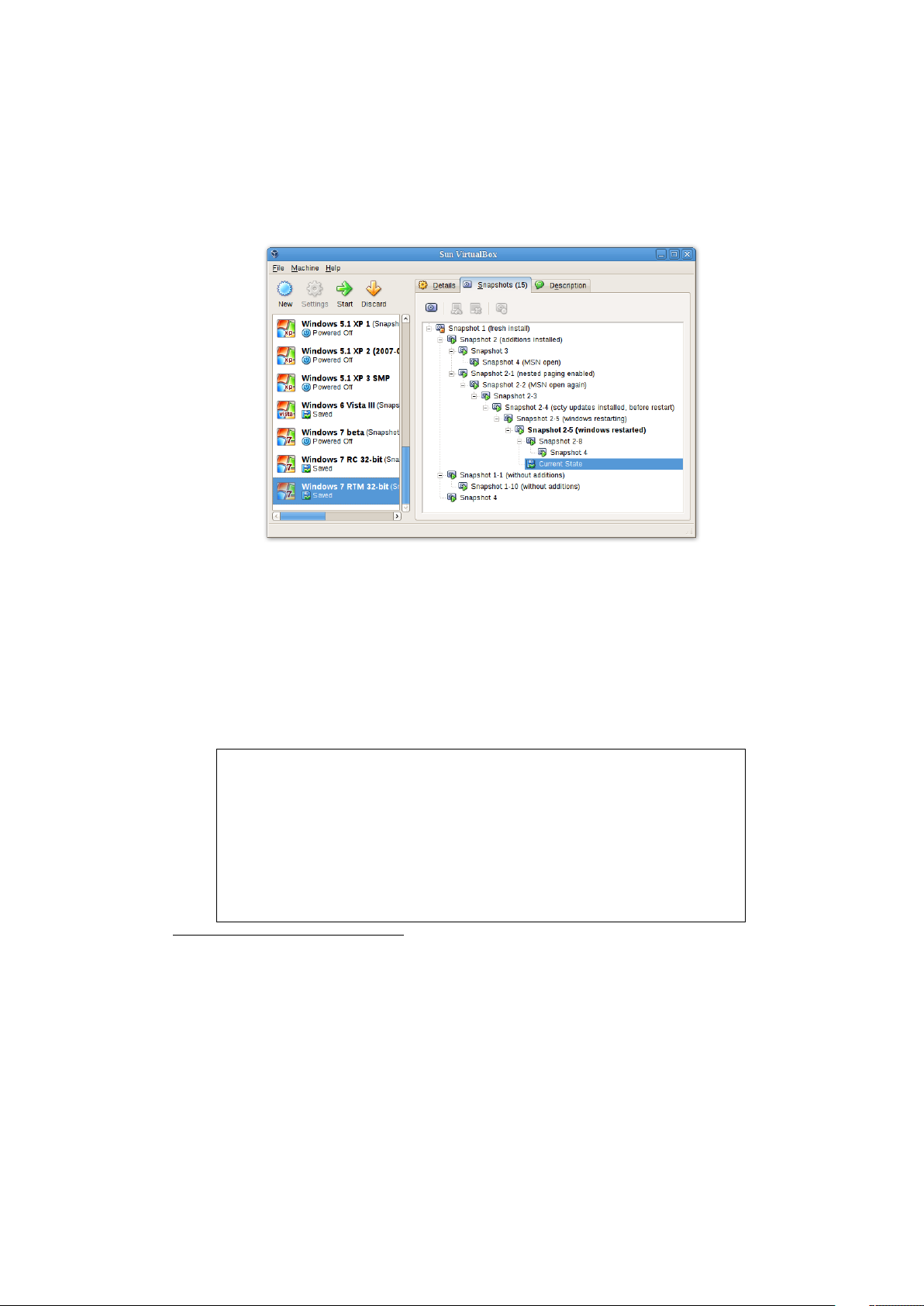

many machines, here’s another example:

16

Page 17

1 First steps

1.6 Creating your first virtual machine

Click on the “New” button at the top of the VirtualBox window. A wizard will pop up

to guide you through setting up a new virtual machine (VM):

17

Page 18

1 First steps

On the following pages, the wizard will ask you for the bare minimum of information

that is needed to create a VM, in particular:

1. A name for your VM, and the type of operating system (OS) you want to install.

The name is what you will later see in the VirtualBox main window, and what

your settings will be stored under. It is purely informational, but once you have

created a few VMs, you will appreciate if you have given your VMs informative

names. “My VM” probably is therefore not as useful as “Windows XP SP2”.

For “Operating System Type”, select the operating system that you want to install

later. Depending on your selection, VirtualBox will enable or disable certain VM

settings that your guest operating system may require. This is particularly important for 64-bit guests (see chapter 3.2, 64-bit guests, page 45). It is therefore

recommended to always set it to the correct value.

2. The amount of memory (RAM) that the virtual machine should have for itself.

Every time a virtual machine is started, VirtualBox will allocate this much memory from your host machine and present it to the guest operating system, which

will report this size as the (virtual) computer’s installed RAM.

Note: Choose this setting carefully! The memory you give to the VM will

not be available to your host OS while the VM is running, so do not specify

more than you can spare. For example, if your host machine has 1 GB of

RAM and you enter 512 MB as the amount of RAM for a particular virtual

machine, while that VM is running, you will only have 512 MB left for all the

other software on your host. If you run two VMs at the same time, even more

memory will be allocated for the second VM (which may not even be able to

start if that memory is not available). On the other hand, you should specify

as much as your guest OS (and your applications) will require to run properly.

A Windows XP guest will require at least a few hundred MB RAM to run properly,

and Windows Vista will even refuse to install with less than 512 MB. Of course,

if you want to run graphics-intensive applications in your VM, you may require

even more RAM.

So, as a rule of thumb, if you have 1 GB of RAM or more in your host computer,

it is usually safe to allocate 512 MB to each VM. But, in any case, make sure you

always have at least 256 to 512 MB of RAM left on your host operating system.

Otherwise you may cause your host OS to excessively swap out memory to your

hard disk, effectively bringing your host system to a standstill.

As with the other settings, you can change this setting later, after you have created the VM.

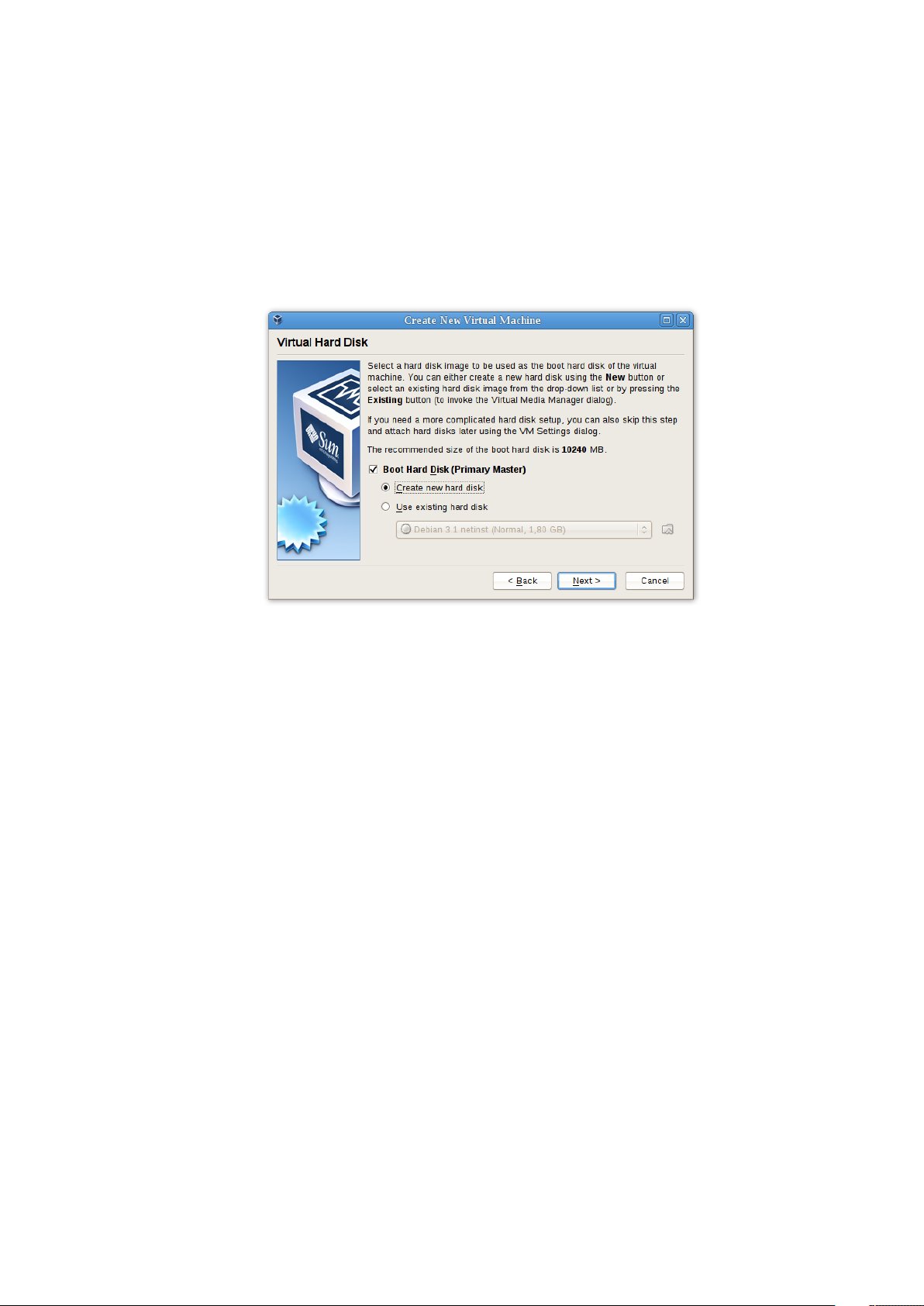

3. Next, you must specify a virtual hard disk for your VM.

18

Page 19

1 First steps

There are many and potentially complicated ways in which VirtualBox can provide hard disk space to a VM (see chapter 5, Virtual storage, page 76 for details),

but the most common way is to use a large image file on your “real” hard disk,

whose contents VirtualBox presents to your VM as if it were a complete hard

disk.

The wizard shows you the following window:

The wizard allows you to create an image file or use an existing one. Note also

that the disk images can be separated from a particular VM, so even if you delete

a VM, you can keep the image, or copy it to another host and create a new VM

for it there.

In the wizard, you have the following options:

• If you have previously created any virtual hard disks which have not been

attached to other virtual machines, you can select those from the dropdown list in the wizard window.

• Otherwise, to create a new virtual hard disk, press the “New” button.

• Finally, for more complicated operations with virtual disks, the “Existing...“

button will bring up the Virtual Disk Manager, which is described in more

detail in chapter 5.3, The Virtual Media Manager, page 80.

Most probably, if you are using VirtualBox for the first time, you will want to

create a new disk image. Hence, press the “New” button.

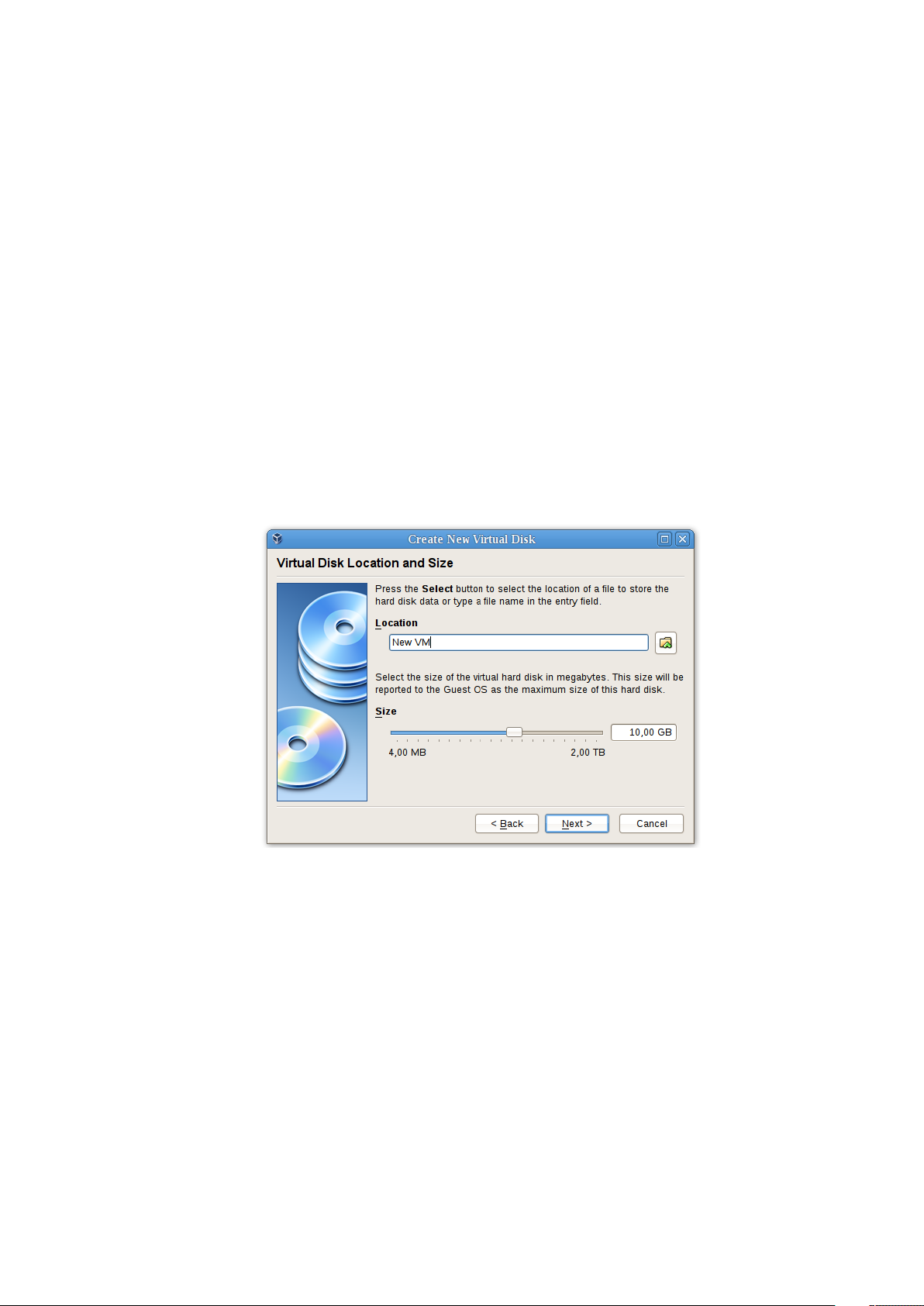

This brings up another window, the “Create New Virtual Disk Wizard”.

VirtualBox supports two types of image files:

19

Page 20

1 First steps

• A dynamically expanding file will only grow in size when the guest actu-

ally stores data on its virtual hard disk. It will therefore initially be small

on the host hard drive and only later grow to the size specified as it is filled

with data.

• A fixed-size file will immediately occupy the file specified, even if only a

fraction of the virtual hard disk space is actually in use. While occupying

much more space, a fixed-size file incurs less overhead and is therefore

slightly faster than a dynamically expanding file.

For details about the differences, please refer to chapter 5.2, Disk image files

(VDI, VMDK, VHD, HDD), page 79.

To prevent your physical hard disk from running full, VirtualBox limits the size

of the image file. Still, it needs to be large enough to hold the contents of

your operating system and the applications you want to install – for a modern

Windows or Linux guest, you will probably need several gigabytes for any serious

use:

After having selected or created your image file, again press “Next” to go to the

next page.

4. After clicking on “Finish”, your new virtual machine will be created. You will

then see it in the list on the left side of the main window, with the name you

have entered.

20

Page 21

1 First steps

1.7 Running your virtual machine

You will now see your new virtual machine in the list of virtual machines, at the left of

the VirtualBox main window. To start the virtual machine, simply double-click on it,

or select it and press the “Start” button at the top.

This opens up a new window, and the virtual machine which you selected will boot

up. Everything which would normally be seen on the virtual system’s monitor is shown

in the window, as can be seen with the image in chapter 1.2, Some terminology, page

11.

Since this is the first time you are running this VM, another wizard will show up

to help you select an installation medium. Since the VM is created empty, it would

otherwise behave just like a real computer with no operating system installed: it will

do nothing and display an error message that it cannot boot an operating system.

For this reason, the “First Start Wizard” helps you select an operating system

medium to install an operating system from. In most cases, this will either be a real

CD-ROM or DVD (VirtualBox can then configure the virtual machine to use your host’s

drive), or you might have an ISO image of a CD-ROM or DVD handy, which VirtualBox

can then present to the virtual machine.

In both cases, after making the choices in the wizard, you will be able to install your

operating system.

In general, you can use the virtual machine much like you would use a real computer. There are couple of points worth mentioning however.

1.7.1 Keyboard and mouse support in virtual machines

1.7.1.1 Capturing and releasing keyboard and mouse

Since the operating system in the virtual machine does not “know” that it is not running on a real computer, it expects to have exclusive control over your keyboard and

mouse. This is, however, not the case since, unless you are running the VM in fullscreen mode, your VM needs to share keyboard and mouse with other applications

and possibly other VMs on your host.

As a result, initially after installing a host operating system and before you install

the guest additions (we will explain this in a minute), only one of the two – your VM

or the rest of your computer – can “own” the keyboard and the mouse. You will see a

second mouse pointer which will always be confined to the limits of the VM window.

Basically, you activate the VM by clicking inside it.

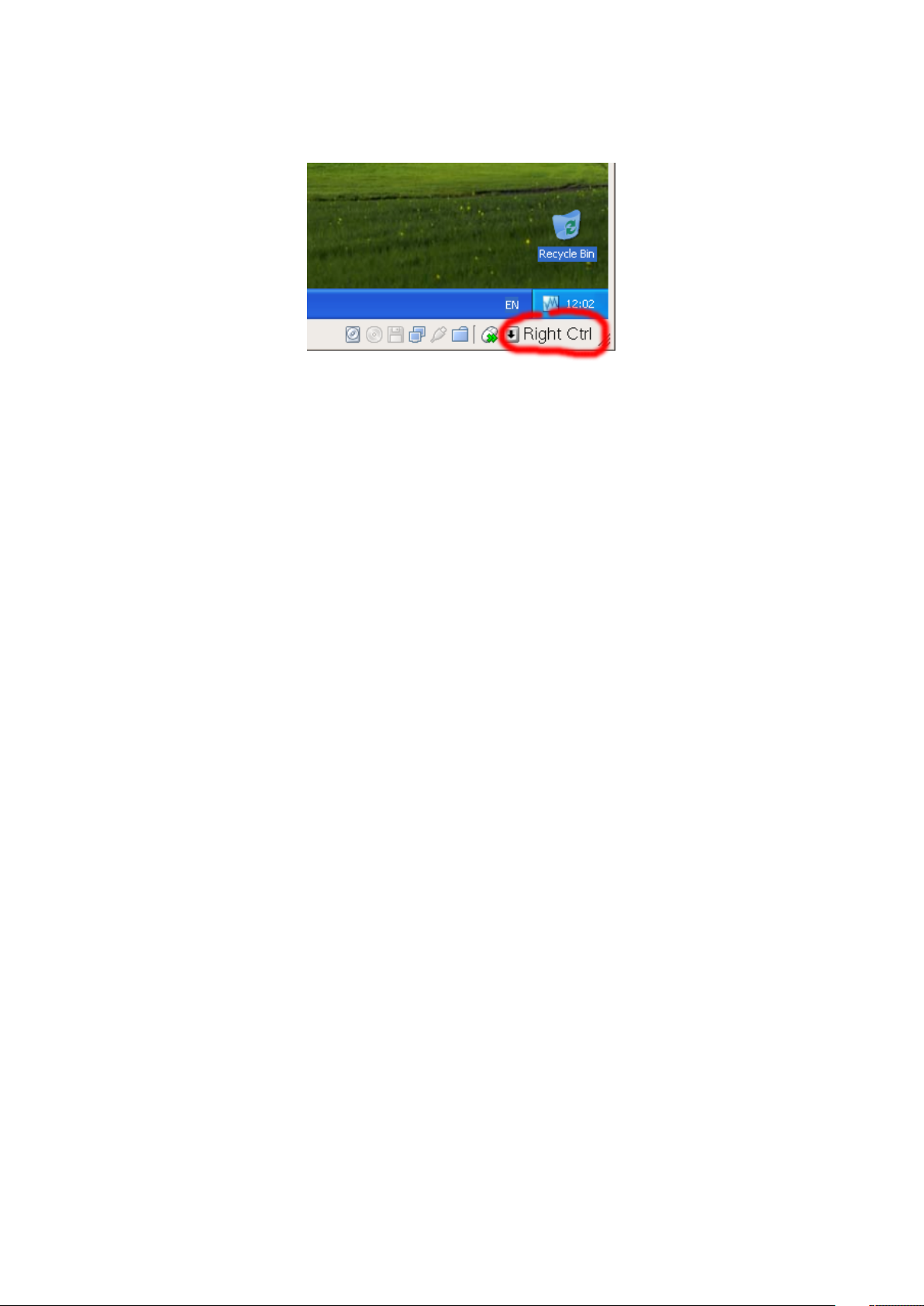

To return ownership of keyboard and mouse to your host operating system,

VirtualBox reserves a special key on your keyboard for itself: the “host key”. By

default, this is the right Control key on your keyboard; on a Mac host, the default host

key is the left Command key. You can change this default in the VirtualBox Global

Settings. In any case, the current setting for the host key is always displayed at the

bottom right of your VM window, should you have forgotten about it:

21

Page 22

1 First steps

In detail, all this translates into the following:

• Your keyboard is owned by the VM if the VM window on your host desktop

has the keyboard focus (and then, if you have many windows open in your guest

operating system as well, the window that has the focus in your VM). This means

that if you want to type within your VM, click on the title bar of your VM window

first.

To release keyboard ownership, press the Host key (as explained above, typically

the right Control key).

Note that while the VM owns the keyboard, some key sequences (like Alt-Tab for

example) will no longer be seen by the host, but will go to the guest instead.

After you press the host key to re-enable the host keyboard, all key presses will

go through the host again, so that sequences like Alt-Tab will no longer reach the

guest.

• Your mouse is owned by the VM only after you have clicked in the VM window.

The host mouse pointer will disappear, and your mouse will drive the guest’s

pointer instead of your normal mouse pointer.

Note that mouse ownership is independent of that of the keyboard: even after

you have clicked on a titlebar to be able to type into the VM window, your mouse

is not necessarily owned by the VM yet.

To release ownership of your mouse by the VM, also press the Host key.

As this behavior can be inconvenient, VirtualBox provides a set of tools and device

drivers for guest systems called the “VirtualBox Guest Additions” which make VM keyboard and mouse operation a lot more seamless. Most importantly, the Additions will

get rid of the second “guest” mouse pointer and make your host mouse pointer work

directly in the guest.

This will be described later in chapter 4, Guest Additions, page 60.

1.7.1.2 Typing special characters

Operating systems expect certain key combinations to initiate certain procedures.

Some of these key combinations may be difficult to enter into a virtual machine, as

22

Page 23

1 First steps

there are three candidates as to who receives keyboard input: the host operating system, VirtualBox, or the guest operating system. Who of these three receives keypresses

depends on a number of factors, including the key itself.

• Host operating systems reserve certain key combinations for themselves. For

example, it is impossible to enter the Ctrl+Alt+Delete combination if you want

to reboot the guest operating system in your virtual machine, because this key

combination is usually hard-wired into the host OS (both Windows and Linux

intercept this), and pressing this key combination will therefore reboot your host.

Also, on Linux and Solairs hosts, which use the X Window System, the key combination Ctrl+Alt+Backspace normally resets the X server (to restart the entire

graphical user interface in case it got stuck). As the X server intercepts this combination, pressing it will usually restart your host graphical user interface (and

kill all running programs, including VirtualBox, in the process).

Third, on Linux hosts supporting virtual terminals, the key combination

Ctrl+Alt+Fx (where Fx is one of the function keys from F1 to F12) normally

allows to switch between virtual terminals. As with Ctrl+Alt+Delete, these

combinations are intercepted by the host operating system and therefore always

switch terminals on the host.

If, instead, you want to send these key combinations to the guest operating system in the virtual machine, you will need to use one of the following methods:

– Use the items in the “Machine” menu of the virtual machine window. There

you will find “Insert Ctrl+Alt+Delete” and “Ctrl+Alt+Backspace”; the latter will only have an effect with Linux or Solaris guests, however.

– Press special key combinations with the Host key (normally the right Con-

trol key), which VirtualBox will then translate for the virtual machine:

∗ Host key + Del to send Ctrl+Alt+Del (to reboot the guest);

∗ Host key + Backspace to send Ctrl+Alt+Backspace (to restart the

graphical user interface of a Linux or Solaris guest);

∗ Host key + F1 (or other function keys) to simulate Ctrl+Alt+F1 (or

other function keys, i.e. to switch between virtual terminals in a Linux

guest).

• For some other keyboard combinations such as Alt-Tab (to switch between open

windows), VirtualBox allows you to configure whether these combinations will

affect the host or the guest, if a virtual machine currently has the focus. This

is a global setting for all virtual machines and can be found under “File” ->

“Preferences” -> “Input” -> “Auto-capture keyboard”.

1.7.2 Changing removable media

While a virtual machine is running, you can change removable media in the “Devices”

menu of the VM’s window. Here you can select in detail what VirtualBox presents to

your VM as a CD, DVD, or floppy.

23

Page 24

1 First steps

The settings are the same as would be available for the VM in the “Settings” dialog

of the VirtualBox main window, but since that dialog is disabled while the VM is in the

“running” or “saved” state, this extra menu saves you from having to shut down and

restart the VM every time you want to change media.

Hence, in the “Devices” menu, VirtualBox allows you to attach the host drive to the

guest or select a floppy or DVD image using the Disk Image Manager, all as described

in chapter 1.9, Virtual machine configuration, page 27.

1.7.3 Saving the state of the machine

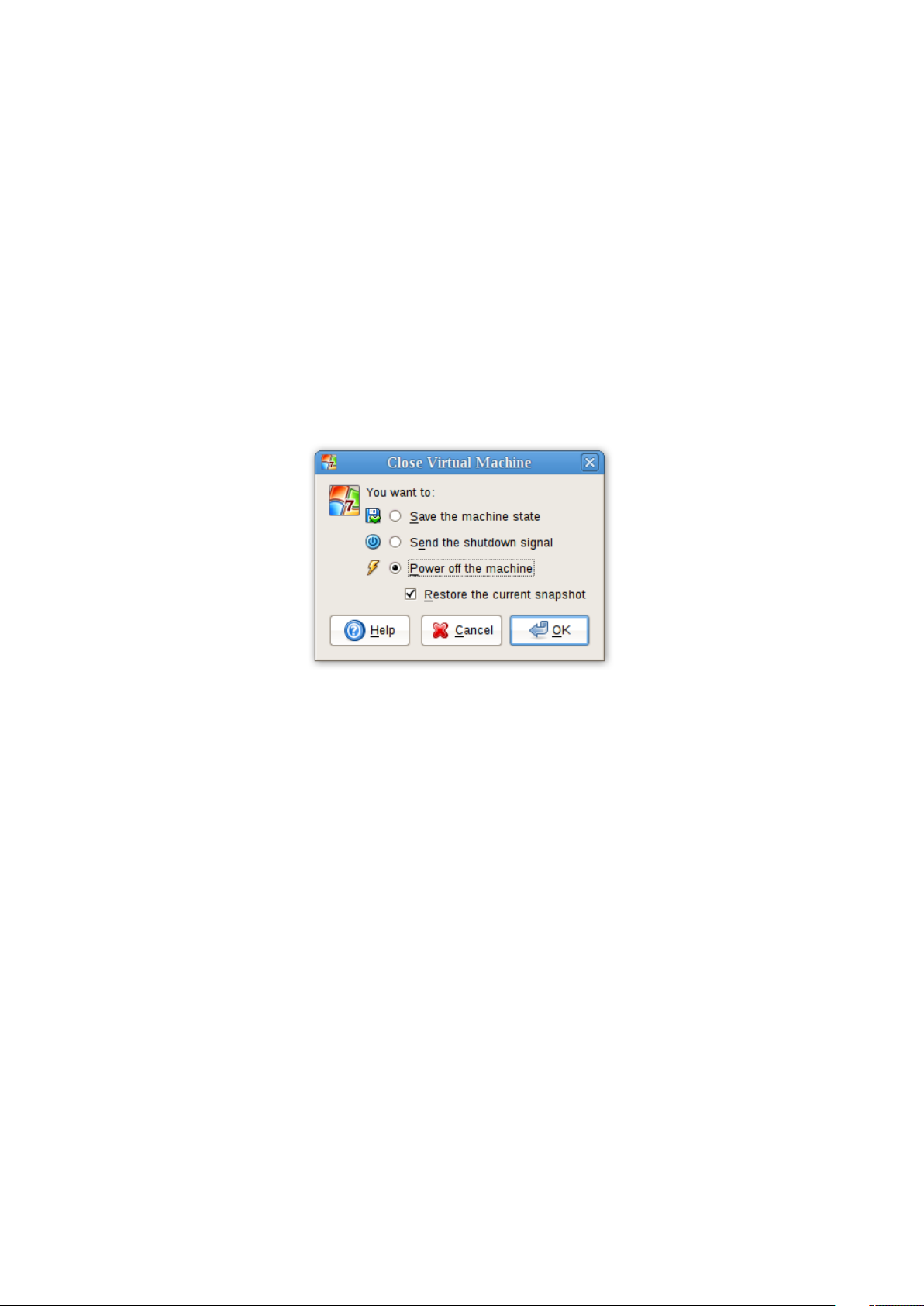

When you click on the “Close” button of your virtual machine window (at the top right

of the window, just like you would close any other window on your system) (or press

the Host key together with “Q”), VirtualBox asks you whether you want to “save” or

“power off” the VM.

The difference between these three options is crucial. They mean:

• Save the machine state: With this option, VirtualBox “freezes” the virtual ma-

chine by completely saving its state to your local disk. When you later resume the

VM (by again clicking the “Start” button in the VirtualBox main window), you

will find that the VM continues exactly where it was left off. All your programs

will still be open, and your computer resumes operation.

Saving the state of a virtual machine is thus in some ways similar to suspending

a laptop computer (e.g. by closing its lid).

• Send the shutdown signal. This will send an ACPI shutdown signal to the vir-

tual machine, which has the same effect as if you had pressed the power button

on a real computer. So long as a fairly modern operating system is installed and

running in the VM, this should trigger a proper shutdown mechanism in the VM.

• Power off the machine: With this option, VirtualBox also stops running the

virtual machine, but without saving its state.

24

Page 25

1 First steps

This is equivalent to pulling the power plug on a real computer without shutting

it down properly. If you start the machine again after powering it off, your

operating system will have to reboot completely and may begin a lengthy check

of its (virtual) system disks.

As a result, this should not normally be done, since it can potentially cause data

loss or an inconsistent state of the guest system on disk.

As an exception, if your virtual machine has any snapshots (see the next chapter),

you can use this option to quickly restore the current snapshot of the virtual

machine. Only in that case, powering off the machine is not harmful.

The “Discard” button in the main VirtualBox window discards a virtual machine’s

saved state. This has the same effect as powering it off, and the same warnings apply.

1.8 Snapshots

With snapshots, you can save a particular state of a virtual machine for later use. At

any later time, you can revert to that state, even though you may have changed the

VM considerably since then.

You can see the snapshots of a virtual machine by first selecting a machine from

the list on the left of the VirtualBox main window and then selecting the “Snapshots”

tab on the right. Initially, until you take a snapshot of the machine, that list is empty

except for the “Current state” item, which represents the “Now” point in the lifetime

of the virtual machine.

There are three operations related to snapshots:

1. You can take a snapshot.

• If your VM is currently running, select “Take snapshot” from the “Machine”

pull-down menu of the VM window.

• If your VM is currently in either the “saved” or the “powered off ” state (as

displayed next to the VM in the VirtualBox main window), click on the

“Snapshots” tab on the top right of the main window, and then

– either on the small camera icon (for “Take snapshot”) or

– right-click on the “Current State” item in the list and select “Take snap-

shot” from the menu.

In any case, a window will pop up and ask you for a snapshot name. This

name is purely for reference purposes to help you remember the state of the

snapshot. For example, a useful name would be “Fresh installation from scratch,

no external drivers”. You can also add a longer text in the “Description” field if

you want.

Your new snapshot will then appear in the list of snapshots under the “Snapshots”

tab. Underneath, you will see an item called “Current state”, signifying that the

25

Page 26

1 First steps

current state of your VM is a variation based on the snapshot you took earlier.

If you later take another snapshot, you will see that they will be displayed in

sequence, and each subsequent snapshot is a derivation of the earlier one:

VirtualBox allows you to take an unlimited number of snapshots – the only limitation is the size of your disks. Keep in mind that each snapshot stores the state

of the virtual machine and thus takes some disk space.

2. You can restore a snapshot by right-clicking on any snapshot you have taken in

the list of snapshots. By restoring a snapshot, you go back (or forward) in time:

the current state of the machine is lost, and the machine is restored to exactly

the same state as it was when then snapshot was taken.

5

Note: Restoring a snapshot will affect the virtual hard drives that are connected to your VM, as the entire state of the virtual hard drive will be reverted

as well. This means also that all files that have been created since the snapshot and all other file changes will be lost. In order to prevent such data loss

while still making use of the snapshot feature, it is possible to add a second

hard drive in “write-through” mode using the VBoxManage interface and use

it to store your data. As write-through hard drives are not included in snapshots, they remain unaltered when a machine is reverted. See chapter 5.4,

Special image write modes, page 81 for details.

5

Both the terminology and the functionality of restoring snapshots has changed with VirtualBox 3.1. Before

that version, it was only possible to go back to the very last snapshot taken – not earlier ones, and the

operation was called “Discard current state” instead of “Restore last snapshot”. The limitation has been

lifted with version 3.1. It is now possible to restore any snapshot, going backward and forward in time.

26

Page 27

1 First steps

By restoring an earlier snapshot and taking more snapshots from there, it is even

possible to create a kind of alternate reality and to switch between these different

histories of the virtual machine. This can result in a whole tree of virtual machine

snapshots, as shown in the screenshot above.

3. You can also delete a snapshot, which will not affect the state of the virtual

machine, but only release the files on disk that VirtualBox used to store the

snapshot data, thus freeing disk space.

Think of a snapshot as a point in time that you have preserved. More formally, a

snapshot consists of three things:

• It contains a complete copy of the VM settings, so that when you restore a snapshot, the VM settings are restored as well. (For example, if you changed the hard

disk configuration, that change is undone when you restore the snapshot.)

• The state of all the virtual disks attached to the machine is preserved. Going

back to a snapshot means that all changes, bit by bit, that had been made to the

machine’s disks will be undone as well.

(Strictly speaking, this is only true for virtual hard disks in “normal” mode. As

mentioned above, you can configure disks to behave differently with snapshots;

see chapter 5.4, Special image write modes, page 81. Even more formally and

technically correct, it is not the virtual disk itself that is restored when a snapshot

is restored. Instead, when a snapshot is taken, VirtualBox creates differencing

images which contain only the changes since the snapshot were taken, and when

the snapshot is restored, VirtualBox throws away that differencing image, thus

going back to the previous state. This is both faster and uses less disk space. For

the details, which can be complex, please see chapter 5.5, Differencing images,

page 83.)

• Finally, if you took a snapshot while the machine was running, the memory state

of the machine is also saved in the snapshot (the same way the memory can be

saved when you close the VM window) so that when you restore the snapshot,

execution resumes at exactly the point when the snapshot was taken.

1.9 Virtual machine configuration

When you select a virtual machine from the list in the main VirtualBox window, you

will see a summary of that machine’s settings on the right of the window, under the

“Details” tab.

Clicking on the “Settings” button in the toolbar at the top of VirtualBox main window

brings up a detailed window where you can configure many of the properties of the

VM that is currently selected. But be careful: even though it is possible to change all

VM settings after installing a guest operating system, certain changes might prevent a

guest operating system from functioning correctly if done after installation.

27

Page 28

1 First steps

Note: The “Settings” button is disabled while a VM is either in the “running”

or “saved” state. This is simply because the settings dialog allows you to

change fundamental characteristics of the virtual computer that is created for

your guest operating system, and this operating system may not take it well

when, for example, half of its memory is taken away from under its feet. As a

result, if the “Settings” button is disabled, shut down the current VM first.

VirtualBox provides a plethora of parameters that can be changed for a virtual machine. The various settings that can be changed in the “Settings” window are described

in detail in chapter 3, Configuring virtual machines, page 44. Even more parameters

are available with the command line interface; see chapter 8, VBoxManage reference,

page 106.

For now, if you have just created an empty VM, you will probably be most interested

in the settings presented by the “CD/DVD-ROM” section if you want to make a CDROM or a DVD-ROM available the first time you start it, in order to install your guest

operating system.

For this, you have two options:

• If you have actual CD or DVD media from which you want to install your guest

operating system (e.g. in the case of a Windows installation CD or DVD), put the

media into your host’s CD or DVD drive.

Then, in the settings dialog, go to the “CD/DVD-ROM” section and select “Host

drive” with the correct drive letter (or, in the case of a Linux host, device file).

This will allow your VM to access the media in your host drive, and you can

proceed to install from there.

• If you have downloaded installation media from the Internet in the form of an

ISO image file (most probably in the case of a Linux distribution), you would

normally burn this file to an empty CD or DVD and proceed as just described.

With VirtualBox however, you can skip this step and mount the ISO file directly.

VirtualBox will then present this file as a CD or DVD-ROM drive to the virtual

machine, much like it does with virtual hard disk images.

In this case, in the settings dialog, go to the “CD/DVD-ROM” section and select

“ISO image file”. This brings up the Virtual Disk Image Manager, where you

perform the following steps:

1. Press the “Add” button to add your ISO file to the list of registered images.

This will present an ordinary file dialog that allows you to find your ISO file

on your host machine.

2. Back to the manager window, select the ISO file that you just added and

press the “Select” button. This selects the ISO file for your VM.

The Virtual Disk Image Manager is described in detail in chapter 5.3, The Virtual

Media Manager, page 80.

28

Page 29

1 First steps

1.10 Deleting virtual machines

To remove a virtual machine which you no longer need, right-click on it in the list of

virtual machines in the main window and select “Delete” from the context menu that

comes up. All settings for that machine will be lost.

The “Delete” menu item is disabled while a machine is in “Saved” state. To delete

such a machine, discard the saved state first by pressing on the “Discard” button.

However, any hard disk images attached to the machine will be kept; you can delete

those separately using the Virtual Disk Manager; see chapter 5.3, The Virtual Media

Manager, page 80.

You cannot delete a machine which has snapshots or is in a saved state, so you must

discard these first.

1.11 Importing and exporting virtual machines

Starting with version 2.2, VirtualBox can import and export virtual machines in the

industry-standard Open Virtualization Format (OVF).

OVF is a cross-platform standard supported by many virtualization products which

allows for creating ready-made virtual machines that can then be imported into a

virtualizer such as VirtualBox. As opposed to other virtualization products, VirtualBox

now supports OVF with an easy-to-use graphical user interface as well as using the

command line. This allows for packaging so-called virtual appliances: disk images

together with configuration settings that can be distributed easily. This way one can

offer complete ready-to-use software packages (operating systems with applications)

that need no configuration or installation except for importing into VirtualBox.

Note: The OVF standard is complex, and support in VirtualBox is an ongoing

process. In particular, no guarantee is made that VirtualBox supports all appliances created by other virtualization software. For a list of know limitations,

please see chapter 13, Known limitations, page 237.

An appliance in OVF format will typically consist of several files:

1. one or several disk images, typically in the widely-used VMDK format (see chapter 5.2, Disk image files (VDI, VMDK, VHD, HDD), page 79) and

2. a textual description file in an XML dialect with an .ovf extension.

These files must reside in the same directory for VirtualBox to be able to import

them.

A future version of VirtualBox will also support packages that include the OVF XML

file and the disk images packed together in a single archive.

To import an appliance in OVF format, select “File” -> “Import appliance” from the

main window of the VirtualBox graphical user interface. Then open the file dialog and

navigate to the OVF text file with the .ovf file extension.

29

Page 30

1 First steps

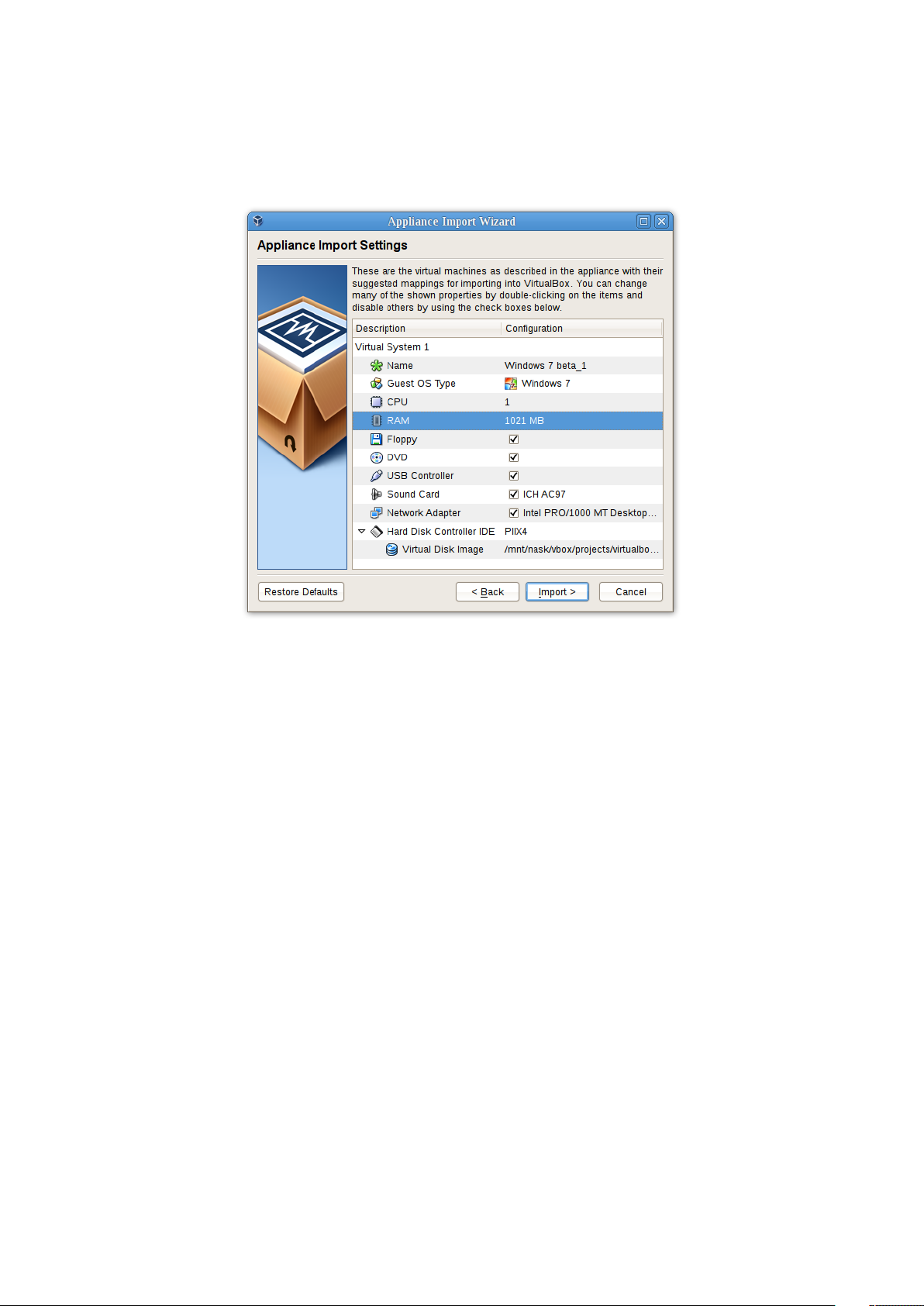

If VirtualBox can handle the file, a dialog similar to the following will appear:

This presents the virtual machines described in the OVF file and allows you to change

the virtual machine settings by double-clicking on the description items. Once you

click on “Import”, VirtualBox will copy the disk images and create local virtual machines with the settings described in the dialog. These will then show up in the list of

virtual machines.

Note that since disk images tend to be big, and VMDK images that come with virtual

appliances are typically shipped in a special compressed format that is unsuitable for

being used by virtual machines directly, the images will need to be unpacked and

copied first, which can take a few minutes.

For how to import an image at the command line, please see chapter 8.6, VBoxMan-

age import, page 118.

Conversely, to export virtual machines that you already have in VirtualBox, select

the machines and “File” -> “Export appliance”. A different dialog window shows up

that allows you to combine several virtual machines into an OVF appliance. Then, you

select the target location where the OVF and VMDK files should be stored, and the

conversion process begins. This can again take a while.

For how to export an image at the command line, please see chapter 8.7, VBoxMan-

age export, page 120.

30

Page 31

1 First steps

Note: OVF cannot describe every feature that VirtualBox provides for virtual

machines. For example, snapshot information gets lost on export; the disk

images will have a “flattened” state identical to the current state of the virtual

machine, but any snapshots that were defined for the machine will have been

merged.

31

Page 32

2 Installation details

As installation of VirtualBox varies depending on your host operating system, we provide installation instructions in four separate chapters for Windows, Mac OS X, Linux

and Solaris, respectively.

2.1 Installing on Windows hosts

2.1.1 Prerequisites

For the various versions of Windows that we support as host operating systems, please

refer to chapter 1.4, Supported host operating systems, page 14.

In addition, Windows Installer 1.1 or higher must be present on your system. This

should be the case if you have all recent Windows updates installed.

2.1.2 Performing the installation

The VirtualBox installation can be started

• either by double-clicking on its executable file (contains both 32- and 64-bit

architectures)

• or by entering

VirtualBox.exe -extract

on the command line. This will extract both installers into a temporary directory

in which you’ll then find the usual .MSI files. Then you can do a

msiexec /i VirtualBox-<version>-MultiArch_<x86|amd64>.msi

to perform the installation.

In either case, this will display the installation welcome dialog and allow you to

choose where to install VirtualBox to and which components to install. In addition to

the VirtualBox application, the following components are available:

USB support This package contains special drivers for your Windows host that

VirtualBox requires to fully support USB devices inside your virtual machines.

32

Page 33

2 Installation details

Networking This package contains extra networking drivers for your Windows host

that VirtualBox needs to support Host Interface Networking (to make your VM’s

virtual network cards accessible from other machines on your physical network).

Depending on your Windows configuration, you may see warnings about “unsigned

drivers” or similar. Please select “Continue” on these warnings as otherwise VirtualBox

might not function correctly after installation.

The installer will create a “VirtualBox” group in the programs startup folder which

allows you to launch the application and access its documentation.

With standard settings, VirtualBox will be installed for all users on the local system.

In case this is not wanted, you have to invoke the installer by first extracting it by using

VirtualBox.exe -extract

and then do as follows:

VirtualBox.exe -msiparams ALLUSERS=2

or

msiexec /i VirtualBox-<version>-MultiArch_<x86|amd64>.msi ALLUSERS=2

on the extracted .MSI files. This will install VirtualBox only for the current user.

2.1.3 Uninstallation

As we use the Microsoft Installer, VirtualBox can be safely uninstalled at any time by

choosing the program entry in the “Add/Remove Programs” applet in the Windows

Control Panel.

2.1.4 Unattended installation

Unattended installations can be performed using the standard MSI support.

2.2 Installing on Mac OS X hosts

2.2.1 Performing the installation

For Mac OS X hosts, VirtualBox ships in a disk image (dmg) file. Perform the following

steps:

1. Double-click on that file to have its contents mounted.

2. A window will open telling you to double click on the VirtualBox.mpkg installer file displayed in that window.

3. This will start the installer, which will allow you to select where to install

VirtualBox to.

After installation, you can find a VirtualBox icon in the “Applications” folder in the

Finder.

33

Page 34

2 Installation details

2.2.2 Uninstallation

To uninstall VirtualBox, open the disk image (dmg) file again and double-click on the

uninstall icon contained therein.

2.2.3 Unattended installation

To perform a non-interactive installation of VirtualBox you can use the command line

version of the installer application.

Mount the disk image (dmg) file as described in the normal installation. Then open

a terminal session and execute:

sudo installer -pkg /Volumes/VirtualBox/VirtualBox.mpkg \

-target /Volumes/Macintosh\ HD

2.3 Installing on Linux hosts

2.3.1 Prerequisites

For the various versions of Linux that we support as host operating systems, please