Sony DSLR-A100H, DSC-W80, DSC-W55BDL, DSC-W35, DSC-W200 Guide

...

Guide to Digital Photography

Spring 2007

Getting the shot you really want.

Any camera will take pictures. Sony®cameras are designed to help

you take great pictures – even when the circumstances are less than

great. Sony cameras shine when the light is low. When subjects are

distant. Or moving quickly. Sony uses the latest digital technology

to help you get the shot you really want.

Sony innovation comes from a mastery of all things digital, from the

sensors that capture your picture to the processor that manages it to

the media that stores it to the battery that powers the entire system.

Backed by these vast resources, we’re free to create digital cameras

that change the way you see the world.

This guide tells you what you need to know about digital photography

and digital photo printing. Along the way we’ll point out the unique

Sony features that help you get the results you’re looking for.

Getting the shot you really want 2

Shooting the digital way: Camera systems 16

Taking your best shot: Camera control 34

Sharing your pictures 44

Sony product guide 50

Digital still camera specifications 54

Index 56

CONTENTS

Television and monitor pictures simulated.

Have you ever seen pictures with the faces bleached out

because the flash was too strong? Or blurry faces because

the camera didn’t know where to focus? Or faces too

dark because light was coming from behind? Sony’s supremely

powerful BIONZ™processor – originally used in the award-winning

a100 Digital SLR – solves these problems automatically. A BIONZ

function called Face Detection analyzes the scene, identifying and

tracking up to eight faces at a time. Then the camera automatically

adjusts for optimum focus, exposure, white balance and flash. The

result? Great pictures, every time!

DSC-W200

Sony solves common exposure, focus, flash

and white balance problems with Face

Detection technology. (Sample photos for

illustration purposes.)

See page 26 for details

or visit www.sony.com/dsctraining.

Actual photo taken with a Sony

®

digital camera. Shutter 1/60 sec. Aperture f7.1. Flash Off. ISO 200.

FACE DETECTION

Monitor picture simulated.

3

Exposure

Without

Face Detection

With Face Detection

Without

Face Detection

With Face Detection

Without

Face Detection

With Face Detection

Without

Face Detection

With Face Detection

Focus Flash White Balance

Face Detection

Friends and family will look their best because Sony has taught cameras

how to recognize – and optimize – the human face.

Sony has helped to deliver a brilliant new canvas on

which you can share your digital pictures. It’s called

HDTV and Sony is the industry leader. Thanks to the Full

HD 1080 output capability of Sony’s latest Cyber-shot®cameras,

you can now enjoy your pictures with more than four times the

detail of conventional, Standard Definition TV. It’s a great way to

share your still pictures – and a stunning way to show off the

performance of your HDTV – especially your Sony BRAVIA™HDTV!

Many cameras even offer an HD Slide Show with music. (HD

connecting cables sold separately.)

DSC-W80

Full HD 1080

A spectacular new way to share your still pictures with the whole crowd:

on your HDTV in HD resolution!

Enjoy High Definition using the optional

VMC-MHC1 cable, optional CSS-HD1

Cyber-shot

®

Station cradle or the

DSC-W80HDPR bundle connected to

your HDTV (sold separately). (Sample

photos for illustration purposes.)

See page 44 for details

or visit www.sony.com/dsctraining.

FULL HD 1080

Actual photo taken with a Sony®digital camera. Shutter 1/60 sec. Aperture f5.6. Flash Off. ISO 200.

Television, monitor and print pictures simulated.

5

Option 1:

HD Component Cable

Option 2:

HD Cradle Solution

Option 3:

HD Camera/Printer Bundle Solution

Result:

HD Photo Sharing

Professional photographers carefully avoid exposure

mistakes like “blown out” highlights and “crushed”

shadow detail. But sometimes, back-lighting, intense

highlights and other tricky situations make these problems hard to

avoid. Until now. A Sony function called Dynamic Range Optimizer

(DRO) preserves highlight and shadow detail, for beautifully exposed

images that are far less like snapshots, far more like what the human

eye actually sees. DRO is a bit of digital wizardry made possible by

Sony’s exclusive BIONZ™processor.

DSC-T100

Out of the shadows

The interplay of highlights and shadows is the soul of photography. Now Sony

helps you make the most of it.

The unprocessed picture (left) is marred

by lost detail in both the highlights and

shadows. The improvement with Sony’s

DRO (right) is plain to see. (Sample photos

for illustration purposes.)

See page 41 for details

or visit www.sony.com/dsctraining.

DYNAMIC RANGE OPTIMIZER (DRO)

Actual photo taken with a Sony®digital camera. Shutter 1/80 sec. Aperture f5.6. Flash Off. ISO 200.

Monitor picture simulated.

7

Without Dynamic Range Optimizer With Dynamic Range Optimizer

Shooting in low light means long exposure times. And

that means that even slight camera motion ends up

destroying the shot with blur. You could set the camera

up on a tripod, but only if you have one handy! You could turn on

the camera’s flash, but that would spoil the mood! Sony has a better

way. Our Clear RAW™noise reduction reduces the picture “noise”

common to low-light exposures. High ISO Sensitivity enables you

to shoot at faster shutter speeds. And Super SteadyShot®optical

image stabilization compensates for camera shake.

DSC-T20

Bye-bye, blur

Handheld shots in low light have been the perfect recipe for blur. Sony uses

three powerful technologies to kiss blur goodbye.

The system uses separate vertical and

horizontal sensors that detect camera

shake. The camera sends an equal-but-

opposite correcting signal to a stabilization

lens, which moves to compensate for shake.

(Sample photos for illustration purposes.)

See page 27 for details

or visit www.sony.com/dsctraining.

Without Super SteadyShot With Super SteadyShot

SUPER STEADYSHOT OPTICAL IMAGE STABILIZATION

Actual photo taken with a Sony®digital camera. Shutter 1/8 sec. Aperture f4.5. Flash Off. ISO 400.

Monitor picture simulated.

9

Do you shoot kids’ sports? Our DSC-H7 and DSC-H9

offer a 15x optical zoom lens that gets you far closer

than conventional lenses. Since optical quality is

critical, Sony uses a Carl Zeiss®lens. Since 15x optical zoom can

magnify the effect of camera shake, Super SteadyShot®optical

image stabilization helps keep your pictures clearer. And since

sports can mean blur, our Advanced Sports Shooting mode,

intelligent continuous Auto Focus and ultra-fast 1/4000 second

shutter speed deliver razor-sharp results.

DSC-H9

Get into the action

You may be on the sidelines. But your pictures can get right into the action

with Sony high zoom cameras.

Digital zoom (left) sacrifices resolution.

The original pixels can become painfully

obvious. Optical zoom (right) maintains the

full resolution of the image sensor. (Sample

photos for illustration purposes.)

See page 18 for details

or visit www.sony.com/dsctraining.

DIGITAL VS. OPTICAL ZOOM

Actual photo taken with a Sony®digital camera. Shutter 1/500 sec. Aperture f4.8. Flash On. ISO 160.

Monitor picture simulated.

Digital Zoom Optical Zoom

11

To grab a baby’s smile or a soccer goal before it’s

gone, your camera processor needs to be as fast

as your subject. Sony’s BIONZ™processor typically adjusts focus and

exposure in less than half a second. After that, there’s almost no

“shutter lag.” The shutter typically opens less than 0.01 second after

you fully press the release button. (Times vary by camera.) The power

of the BIONZ processor is also the secret behind Sony Face Detection,

Dynamic Range Optimizer, Full HD 1080 output and even in-camera

retouching!

DSC-W90

Shoot at the speed of life

Life moves fast. Thanks to the Sony BIONZ™processor, you can catch the

most memorable moments before they pass you by.

Shutter lag (left) could cause you to miss

the moment. The BIONZ processor (right)

reduces shutter lag to 0.01 second. (Times

vary by camera.) (Sample photos for

illustration purposes.)

See page 26 for details

or visit www.sony.com/dsctraining.

BIONZ™PROCESSOR

Actual photo taken with a Sony®digital camera. Shutter 1/1600 sec. Aperture f6.3. Flash Off. ISO 400.

Monitor picture simulated.

Without BIONZ Processor With BIONZ Processor

13

Time

Press Shutter Release

Processing

Captured Image

Reduced Shutter LagTime

“If only.” It’s a familiar comment to anyone

who prints out pictures. If only the camera’s

flash hadn’t caused those ghoulish red eyes. If only the focus had been

a little better. If only the exposure had been a little brighter. Sony’s

latest printers announce the end of “if only.” Thanks to the BIONZ

™

processor, the printers actually analyze the content of your pictures,

identify defects and correct issues in focus, exposure, red-eye* and

more! We call it the Auto Touch-Up™function. You’ll call it amazing.

DPP-FP90

Picture perfect printing

Any printer can print your pictures. Sony printers improve them – actually

correcting defects and achieving quality that will amaze you.

With the touch of a single button, Sony

printers will analyze your picture data, identify

faults and correct them automatically!

(Sample photos for illustration purposes.)

See page 48 for details

or visit www.sony.com/dsctraining.

AUTO TOUCH-UP FUNCTION

Monitor and print pictures simulated.

* Auto red-eye correction uses technology

from USA FotoNation Inc.

15

Without Auto Touch-Up With Auto Touch-Up

Integral and

interchangeable lenses

Most digital cameras have “integral” lenses,

fixed to the body. Some offer interchangeable

lenses that can be swapped and upgraded.

Both types have their advantages and

Sony makes both types. (See chart for

more information.)

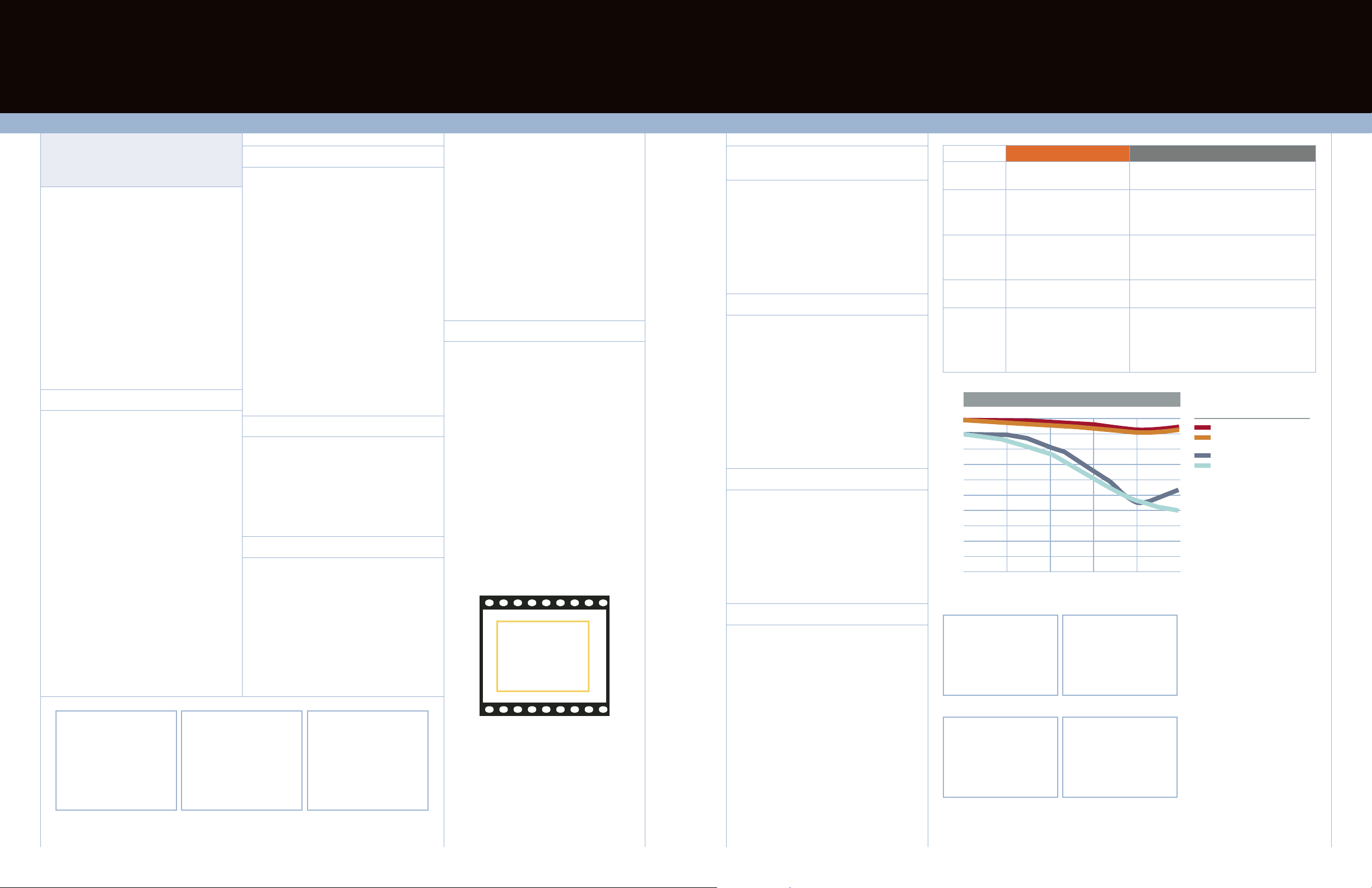

Resolution

When we think of digital camera resolution,

we immediately think of the image sensor.

But an image sensor can only resolve the

detail that the lens presents. A good lens

maintains high contrast at high resolution.

In fact, a special family of graphic curves

called the Modulation Transfer Function

(MTF) describes how well a lens maintains

both resolution and contrast.

Geometric accuracy

The lens is also responsible for rendering

straight lines as straight. While the task

seems simple enough, it is difficult to

achieve at the wide end of zoom lenses,

which tend toward either pincushion or

barrel distortion.

Color convergence

When Isaac Newton demonstrated that a

prism could break white light into its

component colors, he also demonstrated

what would become a drawback in lenses.

Without careful correction, lenses cause

colors to break apart. You can see color

fringing or “chromatic aberration” as

unwanted color along the edges of objects

in the picture. Chromatic aberration is

especially noticeable on the edges between

very bright and very dark areas of the scene.

Chromatic aberration takes the form of

unwanted color fringing, especially on

the edges between very bright and very

dark areas of the scene. (Sample photos

for illustration purposes.)

Barrel distortion (left) and pincushion

distortion (right) are inaccuracies that

lenses can introduce. (Sample photos

for illustration purposes.)

This set of four MTF curves describes

the ability of a lens to maintain contrast

(vertical scale) across the image area

(horizontal scale). As you can see, a

lens can’t be described by a single

resolution number.

Size

Zoom range

Live Preview

off the main

image sensor

Versatility

Migration

17

INTEGRAL LENS

Compact. Tailored to the specific size

of the sensor.

Good. Varies by camera. Sony

15x optical zoom cameras have

phenomenal range from full wide

to full telephoto.

Yes. You see what the camera sees

on the LCD monitor, with indication

of white balance, exposure and

depth of focus.

Good. Zoom lens and conversion

adaptors cover many needs.

No. The body and lens are

permanently joined.

INTERCHANGEABLE LENSES

Larger. Typically optimized for 35mm image size.

Best. Varies by lens selection. However, it’s often difficult

to get wide angle because 35mm lenses undergo a 1.5x

telephoto conversion when used with the smaller,

APS-size image sensor.

No. The main image sensor is blocked by the mirror

until the moment of exposure. You frame via the optical

viewfinder.

Best. A selection of optional lenses gives you maximum

choice.

Yes. As a system evolves, you may be able to keep your

lenses and migrate to compatible new camera bodies.

The a100 works with Minolta Maxxum film camera

lenses from as far back as 1985!

To the casual user, it’s obvious that

the camera takes the picture. But to

accomplished photo professionals, it’s

really the lens that takes the picture. The

lens is responsible for so much of what

defines a great image, including field of view,

focus (and the selection of what objects are

in focus), color, contrast and detail.

Focal length

The angle of view that a lens takes in is

most often described by the focal length

(the distance from the image sensor to the

lens’s “rear nodal point”). Longer focal

lengths correspond to narrower angles of

view (telephoto). Shorter focal lengths

correspond to wide angles of view.

In the world of 35mm film lenses, a 50mm

lens approximates the angle of view of

natural human vision and is considered

a “normal” lens. A 28mm lens is “wide

angle” and a 200mm lens is “telephoto.”

The lens

For example, a 100mm lens with a

maximum aperture of 25mm is an f4.

This generates the same brightness as

a 40mm lens with a maximum aperture

of 10mm (also f4).

The lower the “f” number, the brighter

the lens. Zoom lenses are often brighter

at the wide end than at the telephoto end.

So it’s not unusual to see a zoom lens

specification such as 28-200mm, f2-2.8.

Lens and sensor size

The lens and the image sensor work

together as a team. In a fixed-lens camera,

the lens is carefully tailored to the specific

size and resolution of the image sensor.

Small image sensors work with smaller

lenses – ideal for ultra compact cameras.

But if you want the higher performance and

creative control of a large image sensor,

you’ll need a larger lens to go with it.

The difference becomes even more dramatic

in telephoto and high magnification zoom

lenses. For example, the Sony DSC-H7

15x optical zoom lens extends from 31 to

465mm (35mm equivalent). On a 35mm

camera, such a lens would be gigantic. Yet

the DSC-H7 is quite compact.

Shooting the digital way

“35mm equivalence”

Unfortunately, lens focal lengths are related

to image sensor sizes. And while a 35mm

film frame is always the same size, digital

camera image sensors vary greatly from

model to model, even within a single

manufacturer’s line! The same 16mm

focal length that would be considered an

extremely wide “fisheye” lens on a 35mm

camera can actually be a telephoto lens

on a compact digital camera.

To compare “apples to apples,” the industry

uses a “35mm equivalent” specification

that converts every lens to its equivalent

35mm angle of view – regardless of image

sensor size.

Optical zoom

Optical zoom lenses are specified by a

range of focal lengths, such as 24-120mm.

Because the 120mm image is magnified

five times compared to the 24mm image,

this is also called a “5x optical zoom” lens.

Maximum aperture

The lens is like a window, admitting light.

The wider the window, the more light will

be let in. The width of the window is called

the “maximum aperture” and it’s expressed

as an “f” number, the ratio of the focal

length, divided by the aperture diameter.

16

34mm 50mm 200mm

Wide, normal and telephoto views of the same subject taken with 34, 50 and 200mm focal lengths (35mm equivalent).

(Sample photos for illustration purposes.)

CAMERA SYSTEMS

CAMERA SYSTEMS

Take a lens designed for 35mm. Put it in front of

an APS-size digital image sensor. Result? A focal

length conversion of about 1.5x. (Sample photo

for illustration purposes.)

35mm film / 24mm lens

APS-size DSLR /

38.4mm equivalent

100%

90%

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

0

LENS MTF CURVES

KEY

36912mm

DISTANCE FROM CENTER

10 Line Pairs/mm Sagittal

10 Line Pairs/mm Meridional

30 Line Pairs/mm Sagittal

30 Line Pairs/mm Meridional

Loading...

Loading...