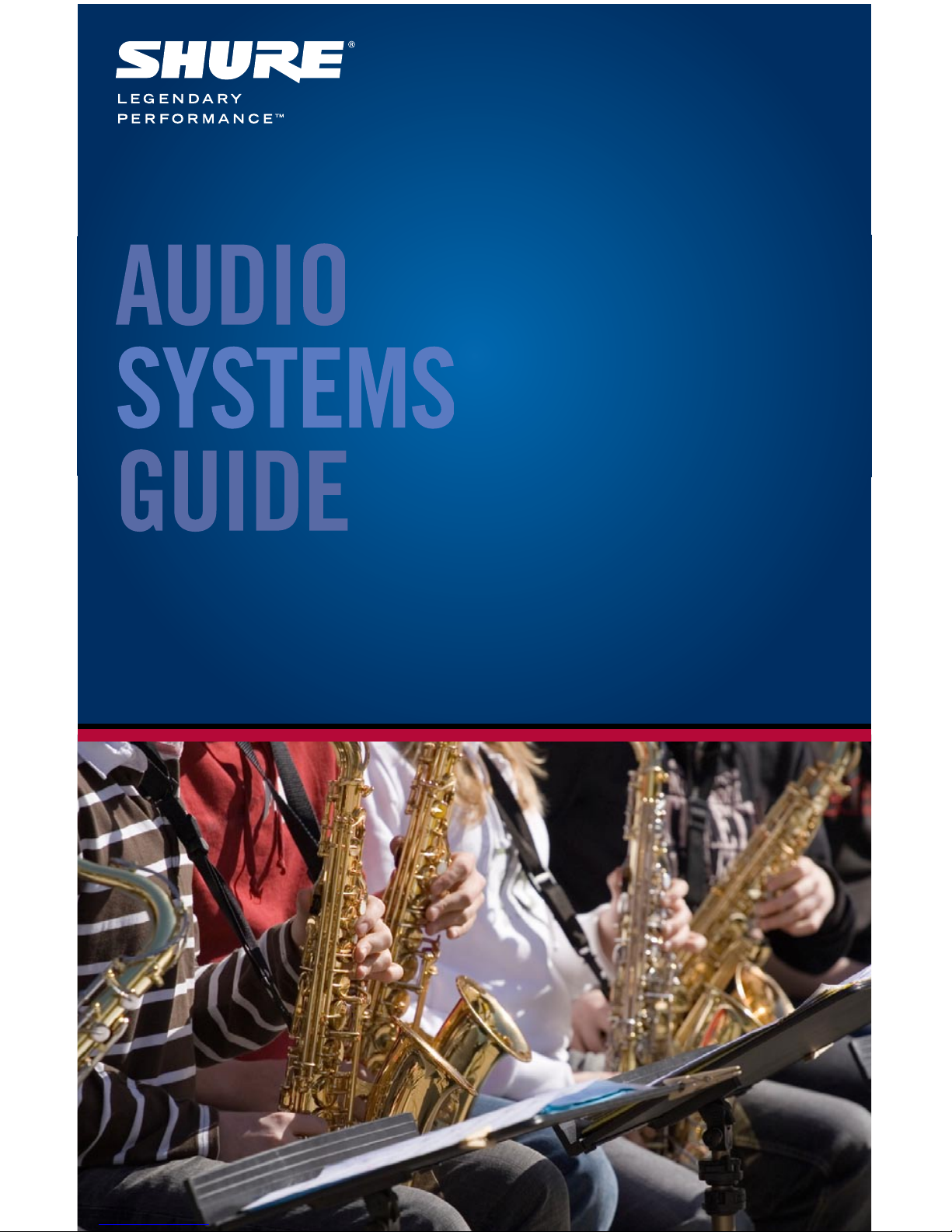

Shure MUSIC EDUCATORS, SM81, PG81, KSM109, Beta 58A User Manual

...

MUSIC EDUCATORS

By Gino Sigismondi

A Shure Educational Publication

Gui

d

Educators

index

e

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

Recording . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

The Parts of a Recording System . . . . . . . . 5

Microphones . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Recording Devices . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Mixers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

Hooking it up . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

Sound Reinforcement for Music . . . . . . . 11

A Basic Sound System . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

Microphones . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

Mixers, Amplifiers and Loudspeakers . . 16

Signal Processors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Hooking it up . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Sound Reinforcement for Theater . . . . . . 22

The Realities of Theater Sound . . . . . . . . . . 22

Lavalier Microphone Techniques for Theater 24

Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

Appendix . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

Glossary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

About the Author . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

Introduction

An often overlooked yet vital part of modern musical performances is the sound

reinforcement (PA) system. In a perfect world, a trained professional would always

be available to purchase, setup, and operate the school’s sound system. In reality,

most educational facilities do not have the available funds for such a luxury.

The responsibility then falls to the next most likely person at school to run the sound

system, the music director. After all, you just need a few microphones and a couple

of loudspeakers, and it’s time to go on tour! And we want it recorded as well!

Unfortunately , sound system setup is not quite that simple. It doesn’t, however, need

to be overly complicated. While the extreme quantity of choices available at your

local music shop may seem daunting (Cardioid? Dynamic? Low Impedance! Help!),

with a few basic guidelines, you can learn what you need, how to connect it, and

even how to make it sound good.

This guide will help you choose equipment for a variety of applications.

For simplicity sake, we will make recommendations of the Shure microphones you

might consider for each application. For those interested in the more technical aspects

of audio equipment, Shure publishes several booklets on a variety of audio topics,

including specific microphone techniques and wireless microphone operation.

Typical scenarios for school music applications include:

• Sound Reinforcement for Large Ensembles

(Concert Band, Orchestra, Choir)

• Sound Reinforcement for Small Ensembles

(Jazz Combo, Vocal Jazz or "Swing" Choir, Rock bands)

• Recording small ensembles

• Recording large ensembles

• Sound for theatrical productions

Recording will be discussed first, due to the smaller number of required

components, and reduced complexity. Feedback and room acoustics play a small

(or even non-existent) role in basic ensemble recording. Additionally, many of the

microphone, and possibly mixer, choices made for recording are equally applicable

in live sound reinforcement. Remember, there are few rules in audio – if it sounds

good to you, it is good. For every application, there will be a good, better, and best

option. A little knowledge and some common sense will allow you to choose a good

system with a reasonable budget and a minimum of frustration.

4

Recording

What do I need?

The parts of a recording system.

To make a decent recording there are two or

three components to consider:

1. The first, and most important, is the microphone. Choosing the right micro-

phone ensures accurate pickup of the desired sounds.

2. Next, consider the recording device. Recording equipment comes in many

shapes and sizes, from simple cassette tape recorders to advanced digital

multitrack machines.

3. Lastly, depending on the capabilities of the recording device, you may need a

mixer. A mixer’s purpose is two-fold; they are used to combine (or "mix")

multiple microphones together, and to properly interface microphones to the

recording device. Most consumer-quality cassette tape recorders, for example,

do not allow a microphone to be directly connected to the record inputs.

A microphone has an extremely low output level that would result in little or no

signal actually making it to tape. A mixer provides gain, which raises the

signal level from the microphone to a level that is acceptable to recorders that

don’t have microphone inputs.

Microphones

The most important questions to ask when choosing microphones are:

a) what are you recording? and

b) what are you using to record?

First, a little about microphones. Microphones are basically simple devices designed

to do one thing: convert sound waves in the air to their electrical equivalent. One

of the first questions you may encounter is, "Do you want a dynamic or condenser

microphone?" These are the two most popular types of microphones in the world.

• Dynamic microphones are typically inexpensive and rugged, with fairly low

sensitivity. In layman’s terms, this means they are good for handheld or

"close-miked" applications. Dynamics are commonly used for solo vocalists

and on drum kits.

• Condenser microphones, on the other hand, are typically (but not always) much

more sensitive than dynamics. Make a good quality condenser microphone your

first choice for miking ensembles, or other applications where the microphone

will be placed at a distance (> 2 ft.) from the sound source. Condensers are

typically used for recording orchestras, choirs, and in other applications where

you wish to capture the sound of the ensemble, versus individual sounds.

Music

Guide

Educators

5

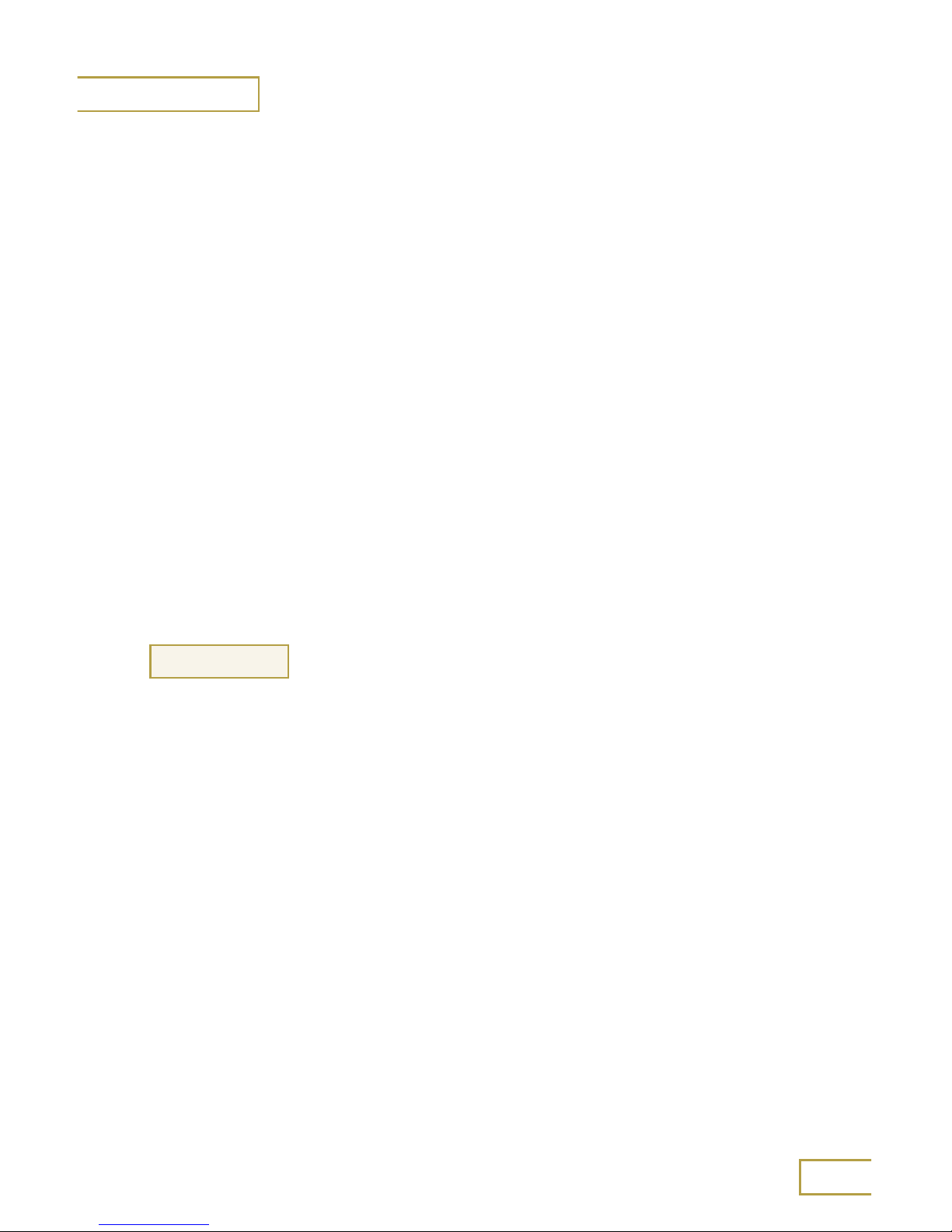

Large ensembles (band, orchestra, choir)

Use a stereo microphone setup to most accurately

capture the sound of a large ensemble. Stereo

recording is not as complicated as it sounds. For

simplicity sake, we’ll use the most basic type of stereo

microphone techniques, the X-Y pattern. Use two

microphones of the same model with the two mic

capsules placed as close as possible, and facing each

other at an angle ranging from 90 – 135 degrees,

depending on the size of the sound source. (see

figure 1). For a wider coverage area, the larger angles

should be used. The X - Y pattern results in good stereo

separation and excellent mono compatibility.

A second, somewhat simpler way to record in stereo uses what is known as a

"single-point" stereo microphone, such as the VP88. The VP88 has a single microphone housing that contains two microphone elements, electrically combined to

produce a stereo output. The advantage to this type of microphone is simplicity; put

the microphone on a stand and point it at what you want to record.

When recording a large ensemble, you may choose to use more than two microphones

to adequately cover each section. A technique known as "area" coverage uses multiple

microphones to cover small sections of the ensemble. Using a choir as an example,

use one microphone for each 6-9 foot wide section, and aim the microphone capsule

towards the last row . Microphones should be placed 2-3 feet in front of the first row of

the choir (see figure 2). The same technique can be applied to concert band or

orchestra, by using one microphone per section.

6

0.6 - 1m

(2 - 3 ft)

0.6 - 1m

(2 - 3 ft)

Figure 2: Area miking - side view

Figure 1: Choir microphone positions - stereo

top view

Recommended Equipment/

Suggested Models:

• 2 cardioid-pattern

condenser microphones

(SM81, PG81, KSM109)

• Microphone stand(s)

• Shure A27M – an accessory that allows you

to mount two microphones on one stand.

• Microphone cables with XLR connectors

• Stereo microphone mixer with at least

2 microphone inputs

• Recording device (see next section)

• Cables to connect mixer to recording device

Small ensembles (jazz combos, string quartet, vocal jazz groups)

The stereo techniques described above can also be successfully applied to smaller

ensembles, but to achieve a more "pop" sound, use multiple close microphones,

generally one per instrument. On the following page are some simple techniques for

getting good sounds for a variety of instruments or vocals.

Recommended Equipment/Suggested Models:

• Vocal microphone (Beta 58A, SM58, PG58)

• Guitar amplifier microphone (SM57, PG57)

• Drum microphones (Beta 52 or PG52, SM57,

two PG81 or SM81)

• Piano microphone (PG81, SM81, or KSM27)

• Woodwinds (SM57, PG57)

• Brass (SM57, PG57)

• Microphone stands

• Microphone cables with XLR connectors

• Microphone mixer with enough inputs to handle

the desired number of microphones

• Recording device (see next section)

• Cables to connect mixer to recording device

Music

Guide

Educators

7

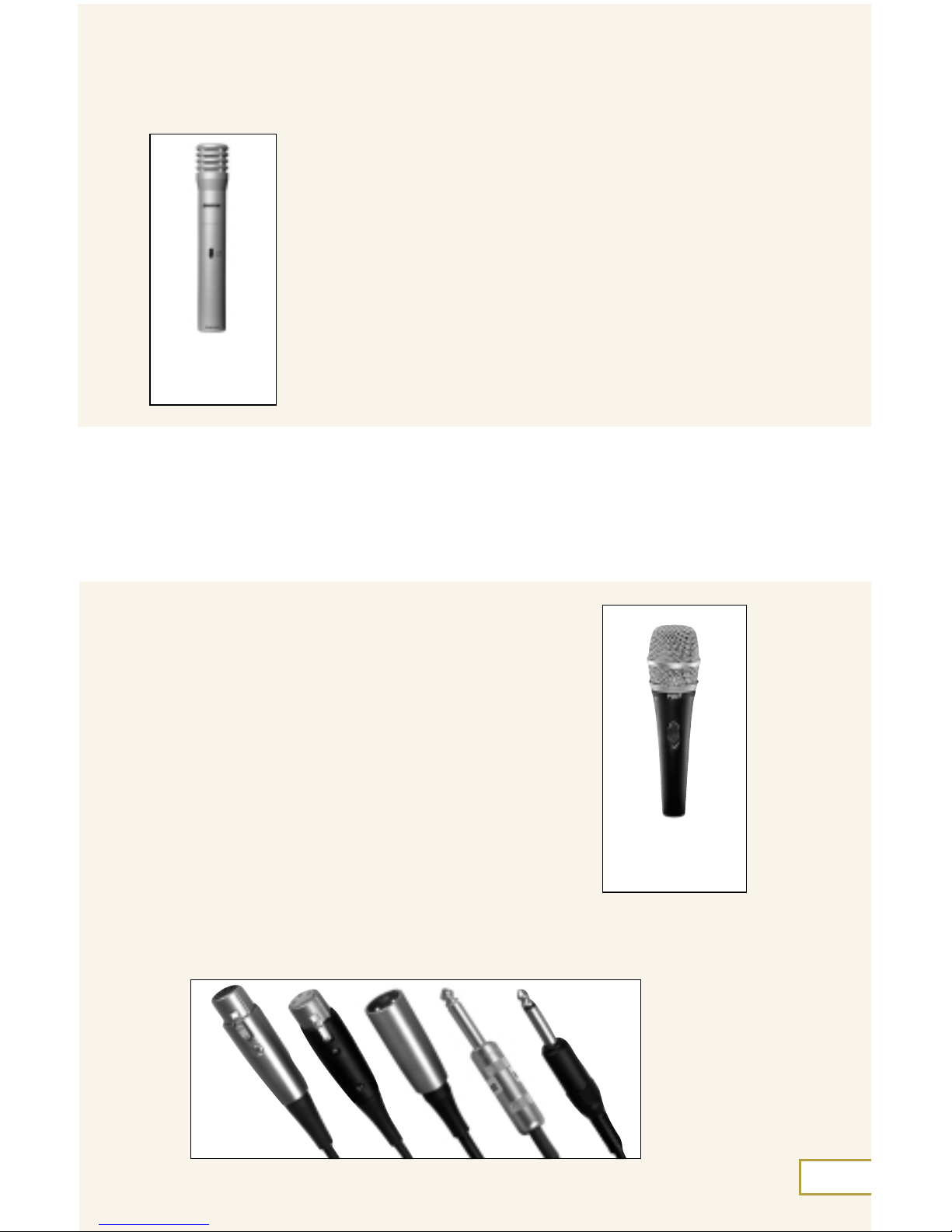

Connectors commonly

used for audio

(from left to right:

3-Pin XLR female,

3-Pin XLR female – black,

3-Pin XLR male,

1/4” mono plug,

1/4” mono plug – black

PG57

Dynamic

Microphone

KSM109

Condenser

Microphone

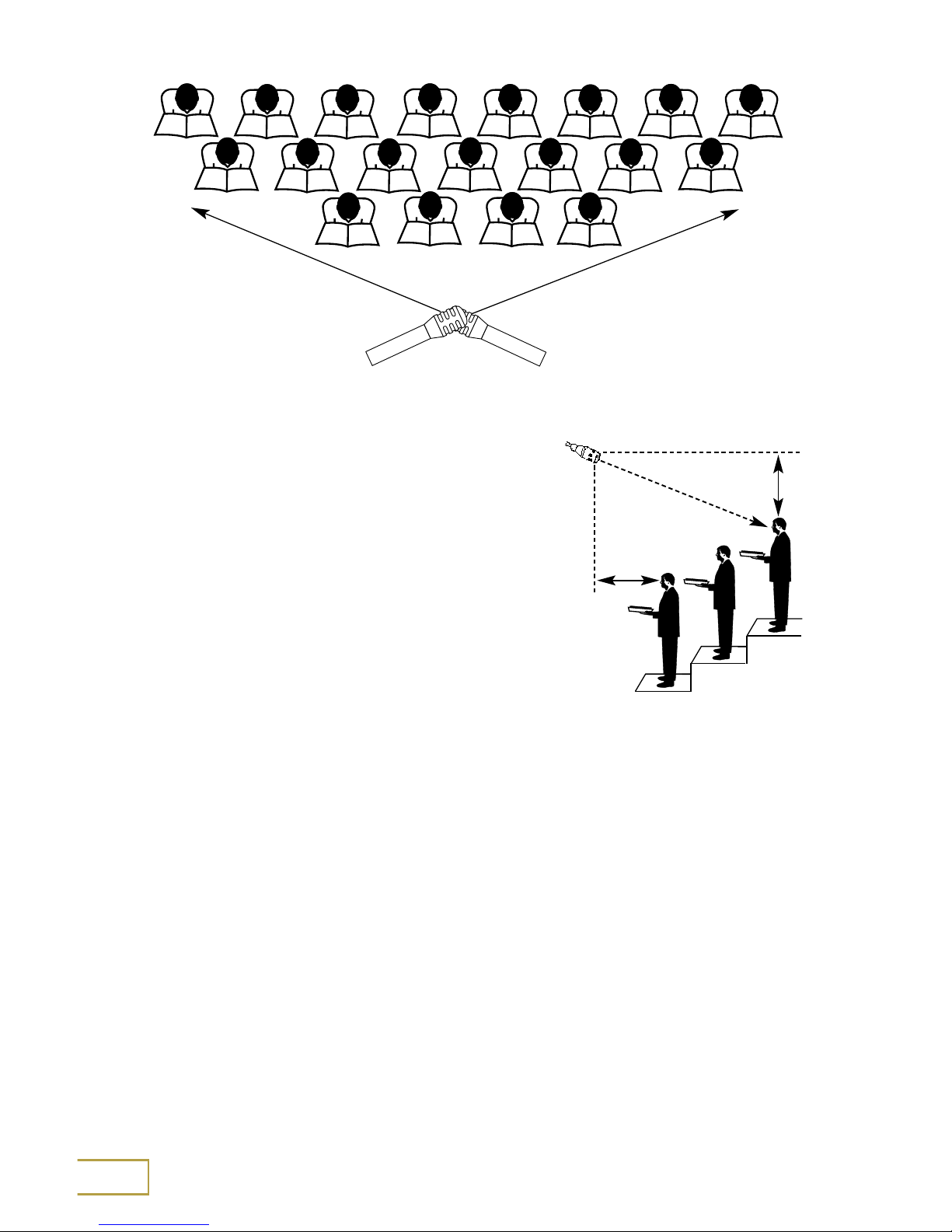

Vocals – T ry using a handheld style (although mounted on

a stand to reduce handling noise) dynamic microphone,

such as the SM58 or Beta 58A. Place the microphone

roughly 3-4 inches away, and pointed somewhere

between the nose and mouth. If possible, try to isolate the

vocalist from any unwanted sounds – in another room

would be ideal (see figure 3).

Electric Guitar Amplifier –

Use an SM57 microphone roughly 1-4 inches

from the loudspeaker, pointed toward the center

of the speaker cone (see figure 4).

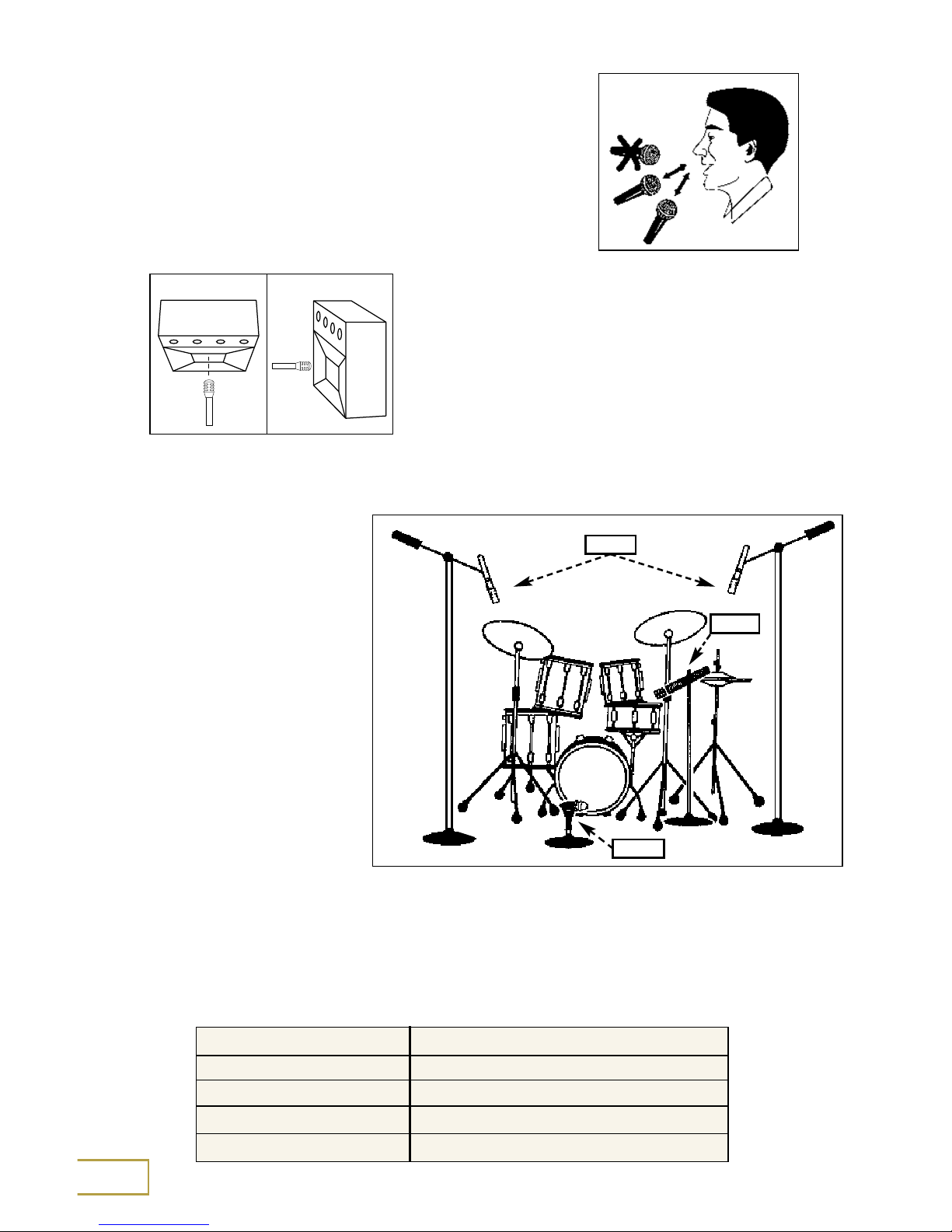

Drums (see figure 5) – While seemingly complex, you can achieve a relatively decent

drum sound with only four microphones:

– Kick Drum – Place a

Beta 52 (or PG52) inside

the drum, approximately

1-6 inches from the

beater head.

– Snare Drum – Use an

SM57 to mike the top

head, placed at a 45

degree angle.

– Toms and cymbals –

Use a pair of condenser

microphones (PG81 or

SM81) suspended over

the drum kit, either

spaced apart or using one of the stereo

microphone techniques described earlier.

If you have a limited number of microphones, use the following chart:

8

Top

Side

Number of Microphones Positioning

One Use an "overhead"

Two Kick drum and overhead

Three Kick drum, snare, and overhead

Four Kick drum, snare, and two overheads

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

PG81

PG52

SM57

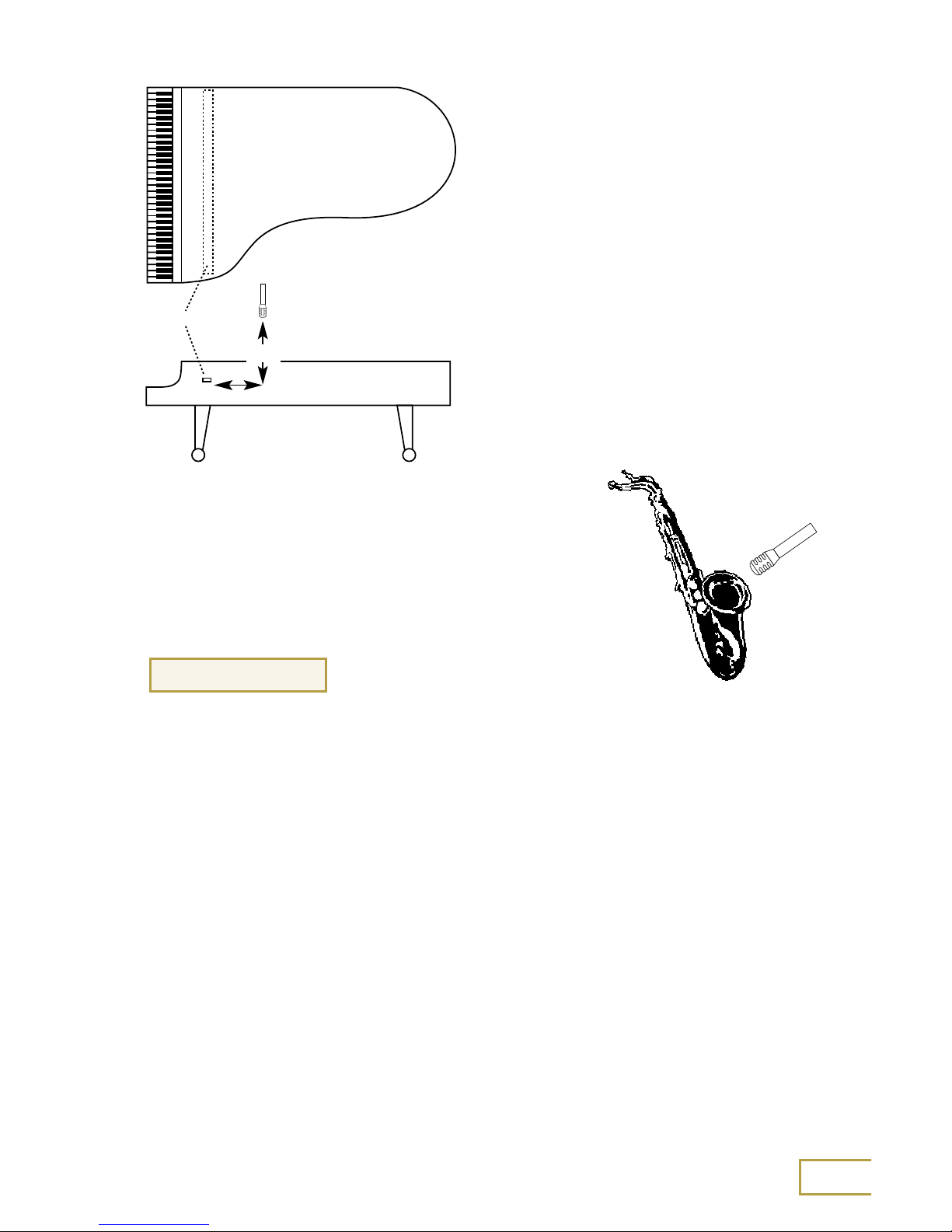

Piano – For a grand or baby grand, place

a PG81 or KSM27 roughly 12 inches

above the middle strings, and 8 inches

from the hammers. The lid should be at full

stick to allow enough clearance for the

microphone. For an upright, place a

similar microphone just over the open top,

above the treble strings (see figure 6).

Woodwinds – Use an SM57 placed a few inches above

the bell and aimed at the sound holes (see figure 7).

Brass – Place an SM57 1 to 2 feet in front of the bell.

The closer the microphone, the brighter the sound.

Recording devices

Two things to consider when choosing a recording format are sound quality and ease

of use. While it may be tempting to buy the same gear that the local recording studio

has, keep in mind your abilities, and how much time you are willing to devote to

pouring over manuals and pushing little buttons. Let’s take at look at some of the more

popular formats.

Cassette

Everyone has operated a cassette tape recorder at some point in their life, making

this a good choice for simple, straight ahead recording. Cassettes are inexpensive

and readily available. Cassette recorders can be purchased at your local electronics

superstore for attractively low prices, or more professional units are usually available

through music and sound retailers. Cassettes, however, rate near the bottom of

the sound quality totem pole. While cassette recordings are perfectly appropriate

for rehearsal or demo tapes, this is not the format to choose if you are looking for a

more "professional" sound, especially if you intend to make the finished product

available for sale.

Music

Guide

Educators

9

Hammers

6”-12”

8”

Figure 6

Figure 7

Most consumer-level tape recorders will not accept a microphone directly. A mixer

(see the next section) will be required to properly interface microphones with a

cassette deck. Certain models of professional level cassette recorders have

microphone inputs on them, but they are often considerably more expensive.

Minidisc

Introduced in the early 1990s, the minidisc format combines the ease of cassette

recording with near-CD quality results. Sound is digitally recorded onto a disk

smaller than a computer’s floppy disk. Minidiscs also allow extensive editing of

the recorded material. Tracks can be moved, divided, combined, named, and

erased, tasks that are impossible with tape (unless you are really good with a

razor blade!) Consumer minidisc recorders are very similar to cassette recorders

in terms of their operation and audio interface, so any of the recording

techniques described above will apply to both formats.

PC-based Recording

With the price of hard disk storage continuing to plummet, PC-based recording

is quickly becoming a relatively inexpensive way to record high quality audio.

Computers are very useful for making multitrack recordings, which requires

several tracks of audio recorded and later combined into a stereo mix.

Unfortunately, a full discussion of multitrack recording techniques is beyond the

scope of this booklet. (For more information on multitrack recording, see the

Shure/Tascam publication "Microphones and Multitracks". This booklet also

introduces stand-alone multitrack recorders.)

Interfacing a microphone with a computer can be a tricky proposition. Most computer

sound cards have microphone inputs that are designed for low-cost "stick" microphones that are only useful in voice recognition or internet telephony applications.

Better results are obtained with an interface that accepts professional microphones. A

computer recording interface that has microphone inputs will result in better sound

and less time spent fooling around with adapters.

Personal computers also offer an inexpensive way to produce CDs. By recording your

music into a computer, a CD recorder can take those files and "burn" them onto

a recordable CD. Even if the PC isn’t used as the main recording device, the other

formats discussed above can easily be transferred into a computer. Stand-alone CD

recorders are also available, and work on basically the same principle.

10

Loading...

Loading...