Page 1

Pretty Good Privacy™

PGP for Personal Privacy, Version 5.0

For the Mac OS

User’s Guide

PGP

™, Inc.

Page 2

© 1997 by Pretty Good Privacy, Inc . All rights reserved.

5-97. Printed in the United Stat es of America.

PGP for Personal Privacy, Version 5.0

Record the serial number from your License Agreement in the space provided below:

Copyright © [1990], 1997 by Pretty Good Privacy, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

PGP, Pretty Good, and Pretty Good Privacy are registered trademarks of Pretty Good Privacy, Inc. All other

trademarks and registered trademarks are the property of their respective owners.

Pretty Good Privacy, Inc. may have patents and/or pending patent applications covering subject matter

in this document. The furnishing of this document or the software does not give you any license to these

patents.

PGP uses public key algorithms described in U.S. Paten t numbers 4,200,770, 4,218,582, 4,405,829, and

4,424,414, licensed exclusively by Public Key Partners.

PGP uses the IDEA cryptographic cipher described in U.S. Patent number 5,214,703 and is licensed from

Ascom Tech AG. IDEA

The compression code in PGP is by Mark Adler and Jean-loup Gailly, taken with permission from the free

Info-ZIP implementation.

LBalloonTracker is © 1996-1997 Corporate Software & Technologies Int. Inc. (CS&T). Permission is granted for use of LBalloonTracker free of charge, other than acknowledgement of Paul Lalonde and CS&T in

any program using LBalloonTracker (perhaps in an About box or in accompanying documentation).

is a trademark of As c o m T ec h , AG .

The software provided with this documentation is licensed to you for your individual use under the terms

of the End User License Agreement and Limited Warranty provided with the software. The information in

this document is subject to change without notice. Pretty Good Privacy, Inc. does not warrant that the information meets you requirements or that the information is free of errors. The information may include

technical inaccuracies or typographical errors. Changes may be made to the inf ormation and in corporated in new editions of this document, if and when made available by Pretty Good Privacy, Inc.

Export of this software and documentation may be subject to compliance with the rules and regulations

promulgated from time to time by the Bureau of Export Administration, U nited States Department of Commerce, which restrict the export and re-export of certain products and technical data.

PRETTY GOOD PRIVACY, INC.

2121 South El Camino Real, Suite 902

San Mateo, C A 94403

(415) 631-1747

(415) 572-1932 fax

info@pgp.com

http://www.pgp.com

Page 3

LIMITED WARRANTY. Pretty Good Privacy, Inc. warrants that the Softwarewill perform substantially in accordance with the written materials in this package for a period of 90 days from the date of original purchase.

Pretty Good Privacy, Inc.'s entire liability and yo ur exclusive remedy shall be, at Pret ty Good Privacy, Inc.'s

option, either (a) return of the purchase price paid for the license or (b) repair or replacement of the Software

that does not meet Pretty Good Privacy, Inc.'s limited warranty and which is returned at your expense to Pretty

Good Privacy, Inc. with a copy of your receipt. This limited warranty is void if failure of the Software has resulted from accident, abuse, or misapplication. Any repaired or repl ac ement Software will be warranted fo r

the remainder of the original warranty period or 30 days, whiche v er is lo nger.

IF THE SOFTWARE IS EXPORT CONTROLLED (SEE BELOW), THESE REMEDIES ARE NOT AVAILABLE OUTSIDE THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA. NO OTHER WARRANTIES. EXCEPT FOR THE

WARRANTIES SET FORTH HEREIN, THE SOFTWARE AND DOCUMEN TATION ARE PROVIDED "AS IS"

AND PRETTY GOOD PRIVACY, INC. DISCLAIMS ALL OTHER WARRANTIES, EITHER EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS

FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE, CONFORMANCE WITH DESCRIPT ION, AND NON-INFRINGEMENT

OF THIRD PARTY RIGHTS. THIS LIMITED WARRANTY GIVES YOU SPECIFIC LEGAL RIGHTS. YOU

MAY HAVE OTHERS, WHICH VARY FROM STATE TO STATE. LIMITATION OF LIABILITY. PRETTY

GOOD PRIVACY, INC.'S CUMULATIVE LIABILITY TO YOU OR ANY OTHER PARTY FOR ANY LOSS OR

DAMAGES RESULTING FROM ANY CLAIMS, DEMANDS OR ACTIONS ARISING OUT OF OR RELATING

TO THIS AGREEMENT SHALL NOT EXCEED THE PURCHASE PRICE PAID FOR THE LICENSE. IN NO

EVENT SHALL PRETTY GOOD PRIVACY, INC. OR ITS SUPPLIERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY INDIRECT, INCIDENTAL, CONSEQUENTIAL, SPECIAL OR EXEMPLARY DAMAGES OR LOST PROFITS WHATSOEVER (INCLUDING, WITHOUT LIMITATION, DAMAGES FOR LOSS OF BUSINESS PROFITS, BUSINESS

INTERRUPTION, LOSS OF BUSINESS INFORMATION, OR OTHER PECUNIARY LOSS) ARISING OUT

OF THE USE OR INABILITY TO USE THE SOFTWARE, EVEN IF PRETTY GOOD PRIVACY, INC. HAS

BEEN ADVISED OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGES. BECAUSE SOME STATES DO NOT ALLOW

THE EXCLUSION OR LIMITATION OF LIABILITY FOR CONSEQUENTIAL OR INCIDENTAL DAMAGES,

THE ABOVE LIMITATION MAY NOT APPLY TO YOU.

This book was written by Mike Iannamico

special thanks to Gail Kesner Haspert

Page 4

Page 5

Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . v

Chapter 1: Introducing PGP for Personal Privacy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

A Quick Overview . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2

Create a Private and Public Key Pair . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Exchange Public Keys with Others . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Certify and Validate Your Keys . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Encrypt and Sign Your E-mail . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

Decrypt and Verify Your E-mail . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

About This Manual . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Chapter 2: Getting Started . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

System Requirements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7

Compatibility with Other Versions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7

Upgrading from a Previous Version . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9

Installing PGP . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9

Running PGP . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9

Using PGP from the PGPmenu . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

Using PGP from Supported e-mail Applications . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

Using PGP from the PGPtools Window . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

Selecting Recipients . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

PGP for Personal Privacy, Version 5.0 User’s Guide for the Mac OS v

Page 6

Taking Shortcuts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Chapter 3: Making and Exchanging Keys . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Key Concepts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Making a Key Pair . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Protecting Your Keys . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

Distributing Your Public Key . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

Making your Public Key Available Through a Key Server . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

Including your Public Key in an e-mail Message . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

Exporting your Public Key to a File . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

Obtaining the Public Keys of Others . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

Getting Public Keys from a Key Server . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

Adding Public Keys from e-mail Messages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

Importing a Public Key from a File . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

Verifying the Authenticity of a Key . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

Chapter 4: Sending and Receiving Private E-mail. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

Encrypting and Signing E-mail . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

Encrypting and Signing with Supported e-mail Applications . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

Encrypting and Signing with PGPmenu . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

Encrypting and Signing from PGPtools . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

Decrypting and Verifying E-mail . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

Decrypting and Verifying from Supported e-mail Applications . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

Decrypting and Verifying from PGPmenu . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

Decrypting and Verifying from PGPtools . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52

Chapter 5: Managing Keys And Setting Preferences. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55

Managing Your Keys . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55

The PGPkeys Window . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56

Examining a Key . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58

vi Contents

Page 7

Getting Detailed Information About a Key . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 60

Specifying a Default Key Pair . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61

Adding a New User Name or Address . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 62

Checking a Key’s Fingerprint . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63

Signing Someone’s Public Key . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63

Granting Trust for Key Validations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 64

Disabling and Enabling Keys . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65

Deleting a Key or Signature . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66

Changing your Passphrase . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66

Importing and Exporting Keys . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 67

Revoking a Key . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 69

Setting Your Preferences . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .70

General Preferences . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71

Key Files Preferences . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72

E-mail Preferences . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73

PGPmenu Preferences . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 75

Key Server Preferences . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 76

Chapter 6: Security Features and Vulnerabilities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 77

Why I wrote PGP . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 77

Encryption Basics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 82

Beware of Snake Oil . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 99

Vulnerabilities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 104

Cryptanalysis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 110

Recommended Introductory Readings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 111

Other Readings: . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 112

Glossary of Terms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 113

Index . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .117

PGP for Personal Privacy, Version 5.0 User’s Guide for the Mac OS vii

Page 8

viii Contents

Page 9

Chapter 1

Introducing PGP for Personal Privacy

With PGP™ for Personal Privacy, you can easily protect the privacy of

your e-mail messages and file attachments by encrypting them so that

only those with the proper authority can decipher the information. You

can also digitally sign the messages and files you exchange, which

ensures that they have come from the person who allegedly sent them

and that the information has not been tampered with in any way while

in transit.

Here are some of the features offered by PGP 5.0:

• Widely-trusted encryption and decryption incorporating maximumstrength cryptographic technologies

• Digital signature and verification for certifying messages and files

• Quick access to all functions from easily selectable menu items

• Integrated plug-in support for popular e-mail applications

• Implementation of PGP/MIME for quick encryption and decryption

of messages and file attachments when sendi ng and r ecei ving e-mai l

• Simple key generations with up to 4096-bit keys and support for

multiple key formats (RSA and DSS/Diffie-Hellman)

• Sophisticated key management with graphical representations of

key properties

PGP for Personal Privacy, Version 5.0 User’s Guide for the Mac OS 1

Page 10

• Integrated support for distributing and retrieving keys from public

key servers

NOTE:

If you are running the DSS/Diffi e-Hellman version of PGP for Person al

Privacy, it does not generate keys using the RSA algorithm nor does it

encrypt, decrypt, sign, or verify using RSA keys. If you find that you

need to generate keys or otherwise use the RSA algorithm, see the vendor from whom you bough t your PGP product.

The most convenient way to use PGP is through one of the popular email applications supported by the plug-ins. This allows you to encrypt

and sign as well as decrypt and verify your messages while you are

composing and reading your mail. In addition, if you are

communicating with another PGP user who is using an e-mail

application that adheres to the PGP/MIME standard, you can perform

all of the PGP functions on both your messages and any file attachments

by simply clicking a button when sending or receiving your e-mail.

If you are using an e-mail application that is not supported by the plugins, you can easily transfer the text of your e-mail messages to the

Clipboard and perform the necessary PGP functions from there.

A Quick Overview

PGP is based on a widely accepted encryption technology known as

“public key cryptography” in which two complementary keys are used

to maintain secure communications. One of the keys is a private key to

which only you have access and the other is a public key which you

freely exchange with other PGP users. Both your private and public keys

are stored in keyring files which are accessible from the PGPkeys

window in which you perform all your key management functions.

To send someone a private e-mail message, you use a copy of that

person’s public key to encrypt the information, which only they can

decipher by using their private key. Conversel y, when someone wants to

send you encrypted mail, they use a copy of your public key to encrypt

the data, which only you can decipher by using your private key.

You also use your private key to sign the e-mail you send to others. The

recipients can then use their copy of your public key to determine i f you

really sent the e-mail and whether it has been altered while in transit.

2 Chapter 1: Introducing PGP for Personal Privacy

Page 11

When someone sends you e-mail with their digital signature, you use a

copy of their public key to check the digital signature and to make sure

that no one has tampered with the contents.

With PGP you can easily create and manage your keys and access all of

the functions for encrypting and signing as well as decrypting and

verifying your e-mail messages and file attachments.

The following section provides a quick run-through of the procedures

you normally follow in the course of using PGP.

Create a Private and Public Key Pair

Before you can begin using PGP, you need to generate a key pair

consisting of a private key to which only you have access and a public

key that you can copy and make fr eely avail able to everyone with whom

you exchange e-mail. After you install PGP and have restarted your

computer, you can them run PGPkeys and create a new keypair.

Exchange Public Keys with Others

After you have created a key pair, you can begin corresponding with

other PGP users. To do so, you will need a copy of their public key and

they will need a copy of your public key. Since your public key is just a

block of text, it is really quite easy to trade keys with someone. You can

either include your public key in an e-mail message, copy it to a file or

you can post it on a public key server where anyone can get a copy when

they need it.

Certify and Validate Your Keys

Once you have a copy of someone’s public key, you can add it to your

public keyring. You should then check to make sure that the key has not

been tampered with and that it really belongs to the purported owner.

You do this by comparing the unique “fingerprint” on your copy of

someone’s public key to the fingerprint on their key. When you are sure

that you have a valid public key, you sign it to indicate that you feel the

key is safe to use. In addition, you can grant the owner of the key a lev el

of trust indicating how much confidence you have in them to vouch for

the authenticity of someone else’s public key.

PGP for Personal Privacy, Version 5.0 User’s Guide for the Mac OS 3

Page 12

Encrypt and Sign Your E-mail

After you have generated your key pair and have exchanged public

keys, you can begin encrypting and signing e-mail messages and file

attachments.

• If you are using an e-mail applicat ion supported by the plug-i ns, you

can encrypt and sign your messages by selecting the appropriate

options from your application’s tool bar. In addition, if you are

communicating with other PGP users who are using an e-mail

application that adheres to the PGP/MIME standard, you can

encrypt and sign messages as well as file attachments automatically

when you send your mail.

• If your e-mail application is not supported by the plug-ins, you can

use PGPmenu or PGPtools to encrypt your e-mail messages and file

attachments.

Decrypt and Verify Your E-mail

When someone sends you encrypted e-mail, you can unscramble its

contents and verify any appended signature to make sure that the data

originated with the alleged sender and that its contents have not been

altered.

• If you are using an e-mail application that is supported by the plugins, you can decrypt and verify your messages by selecting the

appropriate options from your application’s tool bar. In addition, if

your e-mail application supports the PGP/MIME standard, you can

decrypt and verify messages and file attachments sent using this

format by clicking on an icon when reading your mail.

• If your e-mail application is not supported by the plug-ins, you can

use PGPmenu or PGPtools to decrypt and verify your e-mail

messages and file attachments.

4 Chapter 1: Introducing PGP for Personal Privacy

Page 13

About This Manual

This manual is organized in the following manner:

Chapter 1

Describes the purpose of the program, delves into the concept of public

key encryption and digital signatures and provides a quick overview of

how you will use the program.

Chapter 2

Runs through the steps needed to install and run the PGP program with

a brief discussion of the main components and primary functions.

Chapter 3

Explains how to generate your private and public key pair and de scribes

the methods for exchanging, protecting and authenticating keys.

Chapter 4

Explains how to send and receive e-mail messages and file attachments

depending on the type of e-mail application you and the recipients of

your e-mail are using.

Chapter 5

Explains how to examine and alter a key’s attributes and how to

establish preferences for the PGP program.

Introducing PGP for Personal Privacy

Getting Started

Making and Exchanging Keys

Sending and Receiving Private e-mail

Managing Keys And Setting Preferences

Chapter 6

This chapter is provided by Phil Zimmermann. It describes the basic

concepts behind public key encryption and elaborates on some of the

vulnerabilities.

PGP for Personal Privacy, Version 5.0 User’s Guide for the Mac OS 5

Security Features and Vulnerabilities

Page 14

6 Chapter 1: Introducing PGP for Personal Privacy

Page 15

Chapter 2

Getting Started

This chapter explains how to run PGP and provides a quick

overview of the procedures you will normally follow in the course

of using the product. Based on this information, you will have a

fairly good understanding of how to use PGP which should be

especially appreciated by those who don’t want to read through

the entire manual before beginning to use the product.

System Requirements

• Macintosh II or later model with 68020 or above

• System software 7.5 or later

• 8 MB RAM

• 10 MB hard disk space

• 68K Macs must be running Apple’s CFM 68K 4.0 or above. The PGP

installer will install this if necessary.

Compatibility with Other Versions

PGP has gone through many revisions since it was released by Phil

Zimmermann as a freewar e pr oduct b ack in 1991, and it is estima ted that

there are now over 2 million copies in circulation. Although this version

of PGP represents a significant rewrite of the original program and

incorporates a completely new user interface, it has been designed to be

PGP for Personal Privacy, Version 5.0 User’s Guide for the Mac OS 7

Page 16

compatible with earlier versions of PGP. This means that you can

exchange secure e-mail with those who are still using these older

versions of the product:

PGP 2.6 (Released by MIT)

PGP 4.0 (Released by ViaCrypt)

PGP 4.5 (Released by PGP, Inc.)

Along with the new user interface and other improvements, one of the

distinct differences between this version of PGP and its predecessors is

the ability to generate a new type of key. In addition to the RSA keys

used by previous versions, PGP for Personal Privacy, Version 5.0 gives

you the option of using keys based on the DSS/Diffie-Hellman

encryption and digital signature technologies. Although the DSS/DiffieHellman keys are pr ovided as an alt ernative t o the traditiona l RSA keys,

you can take advantage of these newer keys only if you are exchanging

e-mail with another user who is using one of the newer versions of PGP

which is capable of recognizing these new keys.

Considering that it will take a while befor e the DSS/Dif fie-Hellman keys

gain widespread use in the user community, you will probably want to

reserve a set of RSA keys so that you can continue to communicate with

those who have earlier versions of PGP. If you are encrypting e-mail to

multiple recipients, where some have RSA keys and others have DSS/

Diffie-Hellman keys, the e-mail will be encrypted using the appropriate

type of key for each individual. However, in order for users of older

versions of PGP to handle “mixed” public key e-mail, they must

upgrade their versions of PGP.

Another improvement in this version of PGP is the implementation of

the PGP/MIME standard for some of the plug-ins that integrate PGP

functions directly into popular e-mail applications. If you are using an

application such as Eudora, you will be able to take advantage of this

emerging standard, which lets you encrypt and sign as well as decrypt

and verify your e-mail messages and file attachments automatically

when you send or receive e-mail. However, you should only send this

kind of e-mail to those who are also using PGP with an e-mail

application which adheres to the PGP/MIME standard.

8 Chapter 2: Getting Started

Page 17

Upgrading from a Previous Version

If you are upgrading from a previous version of PGP (from either PGP,

Inc. or ViaCrypt) you may want to remove the old program files before

installing PGP to free-up some disk space. However, you should be

careful not to delete the private and public keyring files used to store

any keys you have created or collected while using the previous versi on.

When you install PGP you are given the option of retaining your

existing private and public keyrings so you won’t have to go through the

trouble of importing all of your old keys. You must copy your old

keyring into the PGP keyrings folder to save them for future use.

Installing PGP

To Install PGP from a CD ROM

1. Start your Macintosh.

2. Insert the CD ROM.

3. Run the Installer.

4. Follow the on-screen prompts.

To Install PG P fr om PG P’s Web Site

1. Download the PGP program onto your computer’s hard drive.

2. Double-click the PGP installation program icon.

3. Follow the on-screen prompts.

Running PGP

PGP works on the data generated by other applications. As such, the

appropriate PGP functions are designed to be immediately available to

you based on the task you are performing at any given moment. There

are three primary ways to use PGP:

• From the PGPmenu

• From within supported e-mail applications

PGP for Personal Privacy, Version 5.0 User’s Guide for the Mac OS 9

Page 18

• From the PGPtools window

Using PGP from the PGPmenu

You can perform most PGP functions from the Finder or from within

most applications by choosing the appropriate options from the

PGPmenu icon in the menubar. This feature provides immediate access

to the PGP functions regardless of which application you are using and

is especially useful if you are using an e-mail application that is not

supported by the PGP plug-ins.

While using e-mail or other text-based applications, you can encrypt and

sign and decrypt and verify text by selecting the appropr iate options

from the pull-down menu. While using the Finder, you can encrypt and

sign and decrypt and verify files and even entire folders.

(If you cannot find this icon in one of your applicati ons, you need to add

the application from the PGPmenu pane of the Prefer ences dial og box in

the PGPkeys application).

Opening the PGPkeys Application

By choosing PGPkeys from the PGPmenu or from the PGP folder, you

open the PGPkeys window that shows the private and public key pairs

you have created for yourself as well as any publi c keys you have a dded

to your public keyring. (If you have not already created a new key pair,

the PGP Key Generation Wizard leads you through the steps necessary

to create a new key pair. However, before going through the process of

creating a new key pair, you should see Chapter 3 for complete details

regarding the various options.)

10 Chapter 2: Getting Started

Page 19

From the PGPkeys window you can create new key pairs and manage all

of your other keys. For instance, this is where you examine the attributes

associated with a particular key, specify how confident you are that the

key actually belongs to the alleged owner, and indicate how well you

trust that person to vouch for the authenticity of other user’s keys. For a

complete explanation of the key management functions you perform

from the PGPkeys window, see Chapter 5.

Setting Preferences

By choosing the Preferences option from the Edit menu in PGPkeys, you

can access the Preferences dialog box where you specify settings which

affect how PGP functions.

PGP for Personal Privacy, Version 5.0 User’s Guide for the Mac OS 11

Page 20

By clicking on the appropriate tab, you can advance to the preference

settings you want to modify. For a complete explanation of these

settings, see Chapter 5.

Getting Help

By choosing the PGP Help option when using PGPkeys or PGPtools

from the Apple Guide menu on the menu bar, you can access the PGP

help system which provides a general overview and instructions for all

of the procedures you are likely to perform.

Using PGP from Supported e-mail Applications

If you have one of the popular e-mail applica tions supported by the PGP

plug-ins, you can access the necessary PGP functions by clicking the

appropriate buttons in your application’s icon bar. For example, you

click the lock icon to indicate that you want to encrypt your message and

the quill icon to indicate that you want to sign it. You then send your

mail the way you normally do

.

When you receive e-mail from another PGP user, you decrypt the

message and verify the person’s digital signature.

To make things even simpler, if you are exchanging e-mail with another

party who is also using PGP and an e-mail application which adher es to

the PGP/MIME standard, both of you can automatically encrypt and

decrypt your e-mail messages and any attached files when you send or

12 Chapter 2: Getting Started

Page 21

retrieve your mail. All you have to do is turn on the PGP/MIME

encryption and signatory functions from the PGP Preferences dialog

box.

When you receive e-mail from someone who uses the PGP/MIME

feature, the mail arrives with an icon in the message window indicating

that it is PGP/MIME encoded.

When you receive PGP/MIME encapsulated mail, all you need do to

decrypt its contents is to double-click the lock icon and to verify

signatures, double-click the quill icon.

Using PGP from the PGPtools Window

If you are using an e-mail application which is not supported by the

plug-ins or if you want to perform PGP functions from within other

applications, you can encrypt and sign or decprypt and verify messages

and files directly from the PGPtools window. You open the PGPtools

window by several means:

• Open the PGP folder and double-click the PGPtools icon.

• Store an alias of PGPtools in the Apple menu, and select PGPtools

from that menu. You can also store an alias on your desktop. You

then double-click on the alias to open PGPtools.

PGP for Personal Privacy, Version 5.0 User’s Guide for the Mac OS 13

Page 22

When the PGPtools window appears, you can begin your encryption

work.

If you are working with text, you perform your encryption/decryption

and signature/verification functions by selecting the text then dragging

it onto the appropriate button in the PGPtools window.

If you are working with files, you can simply drag them to the

appropriate button where the function is performed.

Selecting Recipients

When you send e-mail to someone whose e-mail application is

supported by the PGP plug-ins, the recipient’s e-mail address

determines which keys to use when encrypting the contents. However , if

you enter a user name or e-mail address that does not corre spond to any

14 Chapter 2: Getting Started

Page 23

of the keys on your public keyring or if you are encrypting from

PGPmenu or PGPtools, you must manually select the recipient’s public

key from the Key Selection Dialog box.

All you need do to select a recipient’s public key is to drag the icon

representin g their key into the Recipient’s list box and then click OK. For

complete instructions on how to encrypt and sign and decrypt and

verify e-mail, see Chapter 4.

Taking Shortcuts

While you will find that PGP is quite easy to use, a number of shortcuts

are available to help you accomplish your encryption tasks even quicker.

You can drag a file containing a key into the PGPkeys window to add it

to your key ring. These keyboard shortcuts are shown on all of the PGP

menus and other shortcuts are described in their proper context

throughout this manual.

PGP for Personal Privacy, Version 5.0 User’s Guide for the Mac OS 15

Page 24

16 Chapter 2: Getting Started

Page 25

Chapter 3

Making and Exchanging Keys

This chapter describes how to generate the private and public key

pairs that you need to correspond with other PGP users. It also

explains how to distribute your public key and obtain the public

keys of others so that you can begin exchanging private and

certified e-mail.

Key Concepts

PGP is based on a widely accepted and highly trusted “public key

encryption” system by which you and other PGP users generate a key

pair consisting of a private key and a public key. As its name implies,

only you have access to your private key, but in order to correspond with

other PGP users, you need a copy of their public key and they need a

copy of your public key. You use your private key to sign the

messages and file attachments you send to others and to decrypt the

messages and files they send to you. Conversely, you use the public keys

of others to send them encrypted mail and to verify their digital

signatures.

e-mail

NOTE:

PGP for Personal Privacy, Version 5.0 User’s Guide for the Mac OS 17

Without going into too much technical detail, you might be interested to

know that it is not actually the content of the

using the public key encryption scheme. Instead, the data is encrypted

using a much faster single-key algorithm, and it is this single key that is

actually encrypted using the recipients public key. The recipient then

uses their private key to decry pt this k ey, which allows them to decipher

the encrypted data.

e-mail

that is encry pted

Page 26

Your private key is also used to sign the contents of a given

e-mail

message or file attachment. Anyone who has a copy of your public key

can check your digital signature to confirm that you are the originator of

the mail and that the contents have not been altered in any way during

transit. In the same way, if you want to verify somebody else’s digital

signature or check the integrity of the

e-mail

they send to you, then you

need a copy of their public key to do so.

This version of PGP supports two distinct types of keys—the RSA key

used in older versions of PGP and a new type of key called DSS/DiffieHellman which is based on the latest advancements in cryptographic

technologies. If you plan to exchange

e-mail

with someone who has

PGP for Personal Privacy, Version 5.0 or later, then you can take

advantage of the new DSS/Diffie-Hellman keys. However, if you are

corresponding with someone who is using a previous version of PGP,

you have to use the traditional RSA keys to communicate with them.

NOTE:

If you are upgrading from an earlier version of PGP, you have probably

already generated a private key and have distributed its matching public

key to those with whom you correspond. In this ca se you don’t have to

make a new key pair (as described in the nex t section). I f you ha ve existing

keys, you can copy them into your PGP keyrings folder after installation.

Making a Key Pair

Unless you have already done so while using another version of PGP,

the first thing you need to do before sendi ng or receiving encrypted and

certified

e-mail

a private key that only you possess and a public key that you freely

distribute to those with whom you correspond.

is create a new key pa ir. A key pair consists of two keys:

18 Chapter 3: Making and Exchanging Keys

Page 27

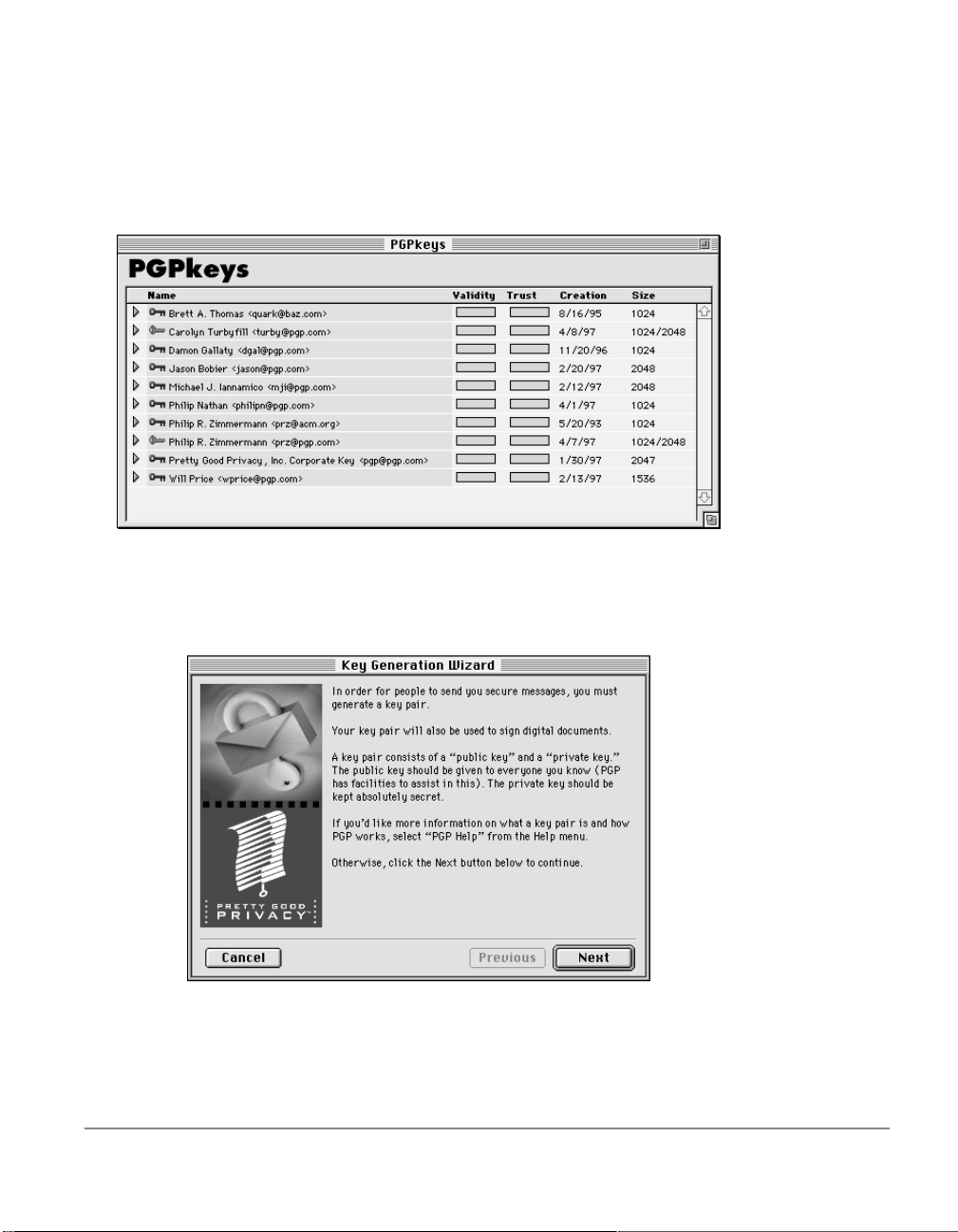

To Create a New Key Pair

1. Either choose the PGPkeys option from PGPmenu or double-click on

the PGPkeys icon from the program folder.

The PGPkeys window opens:

2. Choose New Key option from the Keys menu.

The Key Generation W iz ard pr ovides some intr oductory informa tion

on the first screen.

3. When you are through reading this information, click Next to

advance to the next dialog box.

PGP for Personal Privacy, Version 5.0 User’s Guide for the Mac OS 19

Page 28

The Key Generation Wizard then asks you to enter your user name

and

e-mail

address.

4. Enter your name on the first line and your

second line.

It’s not absolutely necessary to enter your real name or even your

mail

address. However, using your real name makes it easier for

others to identify you as the owner of your public key. Also, by using

your correct

one of a plug-in feature that automatically looks-up the appropriate

key when you address mail to a particular recipient.

5. Click Next to advance to the next dialog box.

e-mail

address, you and others can take advantage of

e-mail

address on the

e-

20 Chapter 3: Making and Exchanging Keys

Page 29

The Key Generation Wizard then asks you to choose a key type.

6. Select a key type, either DSS/Diffie-Hellman or RSA.

Earlier versions of PGP use an older technology referr ed to as RSA to

generate keys. Beginning with this version of PGP, you have the

option of creating a new type of key based on the newer DSS/DiffieHellman technology.

• If you plan to correspond with individuals who are still using the

older RSA keys, you will probably want to generate an RSA key

pair that is compatible with older versions of the program.

• If you plan to correspond with individuals who have the latest

version of PGP, you can take advantage of the new technology and

generate a pair of DSS/Diffie-Hellman keys.

• If you want to be able to exchange

should make a pair of RSA keys and a pair of DSS/Diffie-Hellman

keys and then use the appropriate set depending on the version of

PGP that is being used by the recipient.

7. Click Next to advance to the next dialog box.

PGP for Personal Privacy, Version 5.0 User’s Guide for the Mac OS 21

e-mail

with all PGP users, you

Page 30

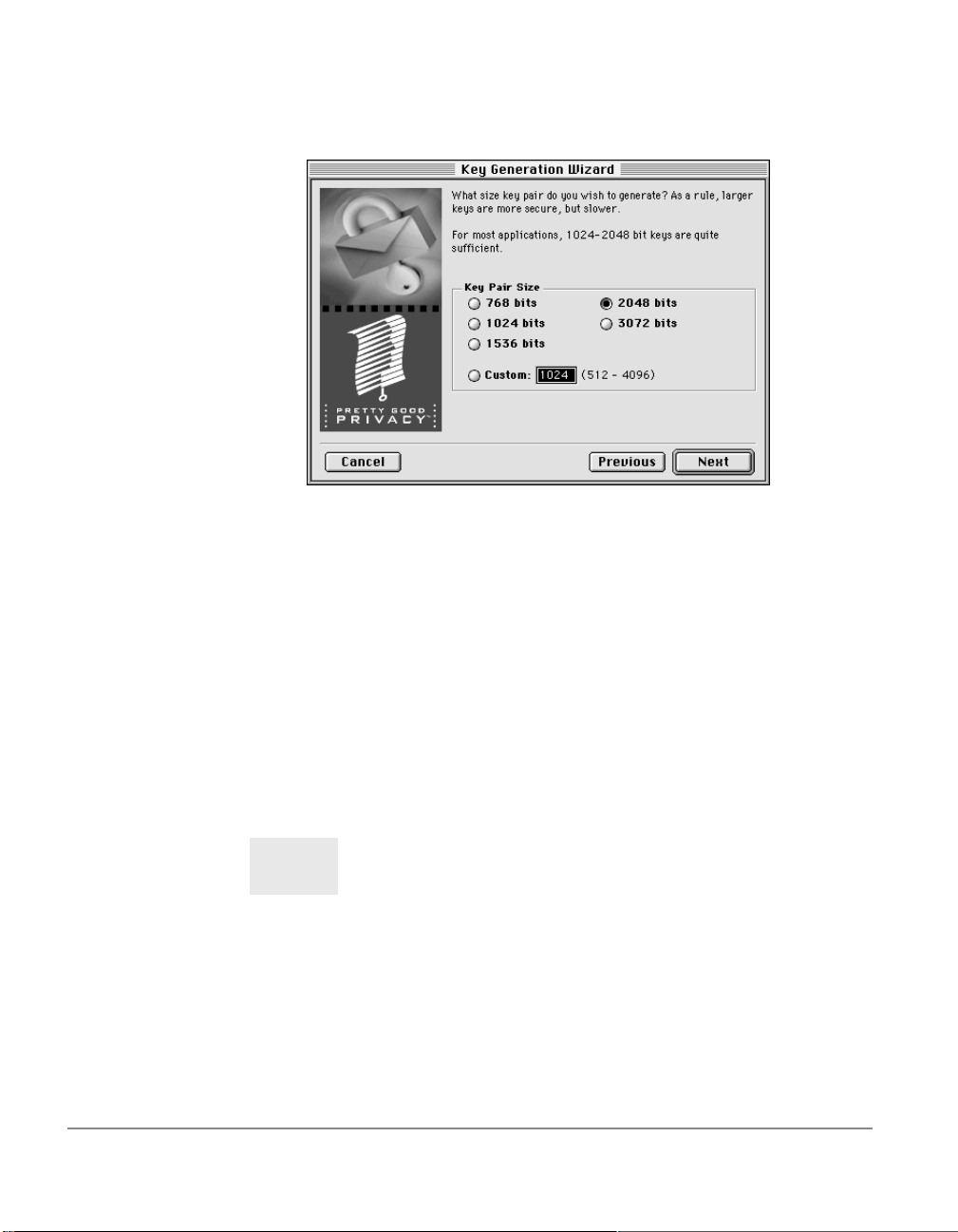

The Key Generation Wizard asks you to specify a size for your new

keys.

8. Select a key size (from 768 to 3072 ) or enter any custom key size fr om

(from 512 to 4096).

The key size corresponds to the number of bits used to construct

your digital key. The larger the key, the less chance that someone will

ever be able to crack it, but the longer it will take to perform the

decryption and encryption process. You will need to strike a balance

between the convenience of performing PGP functions quickly with

a smaller key and the increased level of security provi ded by a larger

key. Unless you are exchanging extremely sensitive information that

is of enough interest that someone would be willing to mount an

expensive and time consuming cryptographic attack in order to r ead

it, you are probably safe using a key composed of 2048 bits.

NOTE:

When creating DSS/Diffie-Hellman keys, the size of the DSS portion of the key is limited to 1024 bits.

9. Click Next to advance to the next dialog box.

22 Chapter 3: Making and Exchanging Keys

Page 31

The Key Generation Wizard asks you to indicate when the key pair

should expire.

10.Indicate when you want your keys to expire. You can either go with

the default selection which is “never”, or you can enter a specific

number of days after which the keys will expire.

Once you create a key pair and have distributed your public key to

the world, you will probably continue to use the same keys fr om that

point on. However, under certain conditions, you may want to create

a special set of keys that you plan to use for only a limited period of

time. In this case, when the public key expires it can no longer be

used by someone to encrypt mail for you but it can still be used to

verify your digital signature. Similarly, when your private key

expires, it can still be used to decrypt mail that was sent to you

before your public key expired but can no longer be used to sign

mail for others.

11.Click Next to advance to the next dialog box.

PGP for Personal Privacy, Version 5.0 User’s Guide for the Mac OS 23

Page 32

The Key Generation Wizard asks you enter a passphrase.

12.In the “Passphrase” entry box, enter the string of characters or words

you want to use to gain exclusive access to your private keys. To

confirm your entry, press the Tab key to advance to the next line,

then enter the same passphrase again. You will notice that the

passphrase bar fills in to indicate the quality of the passphrase you

are entering .

Normally, as an added level of security, the characters you enter for

the passphrase do not appear on the screen. However, if you are sure

that no one is watching over your shoulder, and you would like to

see the characters of your passphrase as you type, clear the “Hide

Typing” check box.

TIP:

Your passphrase should contain multiple words and may include spaces,

numbers, and other printable characters. Choose something that you can

remember easily but that others won’t be able to guess, and keep in mind

that the passphrase is case sensitive. The longer your passphrase, and the

wider the variety of characters it contains, the more secure it is. Try to

include equal numbers of upper and lowercase alphabetic characters,

numbers, punctuation marks and so on.

13.Click Next to begin the key generation process.

24 Chapter 3: Making and Exchanging Keys

Page 33

The Key Generation Wizard indicates that it is busy generating your

key.

If you have entered an inadequate passphrase (less than 8

characters), a warning message appears before the keys are

generated and you have the choice of accepting the bad passphrase

or entering a more secure one before continuing.

If there is not enough random information upon which to build the

key, the PGP Random Data dialog box appears. As instructed on the

screen, move your mouse around and enter a series of random

keystrokes until the progress bar in the dialog box is completely

filled in. Your mouse movements and keystrokes generate random

information that is needed to create a unique key pair.

After the key generation process begins, it may take several minutes

to generate the keys, depending on the speed of your computer.

Eventually the Key Generation Wizard indicates that the key

generation process has completed.

14.Click Next to advance to the next dialog box.

PGP for Personal Privacy, Version 5.0 User’s Guide for the Mac OS 25

Page 34

The Key Generation Wizard indicates that you have successfully

generated a new key pair.

When the Key Generation process completes a pair of keys representing

your newly created keys appears in the PGPkeys window. You will

notice that the older RSA keys are blue and the newer DSS/DiffieHellman keys are yellow. At this point you can examine your keys by

checking their properties and the values associated with them; you may

also want to add other user names or

details on how to examine the pr operties associ ated with a key or how to

included additional user names or addresses, see Chapter 5.

e-mail

addresses. For complete

26 Chapter 3: Making and Exchanging Keys

Page 35

Protecting Your Keys

Once you have generated a set of keys with PGPkeys, it is wise to save a

backup copy of your keyring, and put them in a safe place just in case

something happens to the originals. In fact, when you close the PGPkeys

window after creating a new key pair, you are prompted to save a

backup copy:

Your private keys and your public keys are stored in separate keyring

files, which you can copy just like any other files to another location on

your hard drive or to a floppy disk. By default, the private keyring and

the public keyring are stored along with the other program files in the

PGP file directory, but you can save your backups in any location you

like.

When you specify that you want to save a backup copy of yo ur keys, the

Save As dialog box appears asking you to specify the location in which

to store a backup of your private and public keyring files.

Besides making backup copies of your keys, you should be especially

careful about where you store your private key. Even though your

private key is prote cted by a pass phrase that only you should know, it is

possible that someone could discover your passphrase and then use

PGP for Personal Privacy, Version 5.0 User’s Guide for the Mac OS 27

Page 36

your private key to decipher your

For instance, somebody could look over your shoulder and watch the

keystrokes you enter or intercept them on the network or even over the

airwaves.

To prevent anyone who might happen to get hold of your passphrase

from being able to use your private key, you should only store it on your

own computer. If your computer is attached to a network, you should

also make sure that your files are not automatically included in a

system-wide backup where others might gain access to your private key.

Given the ease with which computers are accessible over today’s

networks, if you are working with extremely sensitive information, you

may want to keep your private key on a floppy disk which you can

insert like an old fashioned key whenev er you want to read or sign your

private mail.

e-mail

or forge your digital signature.

Distributing Your Public Key

After you create your keys , you need to make them availabl e to others so

that they can send you encrypted

signature. You have several alternatives for distributing your public key:

• Make your public key available through a public key server

e-mail

and verify your digital

• Include your public key in an

• Export your public key or copy it to a text file

Since your public key is basically composed of a block of text, it is really

quite easy to make it available through a public key server, include it in

e-mail

an

use whatever method is most convenient to add your public key to their

public keyring.

message or export or copy it to a file. The recipient can then

e-mail

message

Making your Public Key Available Through a Key Server

Probably the best long-term and hassle-free method for making your

public key available is to place it on a public key server where anyone

can access it. By storing your publ ic key on a key server, people can send

e-mail

you

also relieves you and others from having to maintain a large number of

public keys that you rarely use.

28 Chapter 3: Making and Exchanging Keys

without having to explicitly request a copy of your key. It

Page 37

There are a number of key servers, such as those offered by PGP, Inc.

where you can make your public key available for anyone to access. It

doesn’t really matter which key server you use to initially submit your

public key, because once you submit your key to one server it is

automatically propagated to all the other major servers in the world.

Each site provides a slightly different interface for submitting a public

key, but the procedure basically requires you to copy the text content of

your key and then paste it into the proper place on the key server.

However, instead of going through the time-consuming proc ess of fi ring

up a browser and then contacting a public key server, with this version

of PGP you can immediately send or retrieve public keys from a server

whenever you create a new key or at any time ther eaf ter fr om within the

PGPkeys window.

To Send your Public Key to a Key Server

1. If you are not already connected to the Internet, do so now.

2. Open the PGPkeys window.

3. Select the icon that represents the publi c key you want to post on the

key server.

4. Choose Send Selected Keys from the Keyserver submenu of the

Keys menu.

After placing a copy of your public key on a key server, you can tell

those who want to send you encrypted mail or verify your digital

signature to get a copy of your key from the server. Even if you don’t

explicitly point someone to your public key, they can get a copy by

searching the key server for your name or

include the Web address for their public key in the footer of their

messages; with some e-mail applications, the re cipient can just doubleclick the address to access a copy of your key on the server.

If you ever need to change your

signatures, all you have to do to r eplac e your old key is send a new copy

to the server and the information is automatically updated. However,

you should be aware that while new information is added to a key on

the server, deleted information is not removed. This means that if you

delete a signature or user name, the key on the public server is not

updated to reflect these deletions.

PGP for Personal Privacy, Version 5.0 User’s Guide for the Mac OS 29

e-mail

e-mail

address or you acquire new

address. Many people

e-mail

Page 38

If your key is ever compromised, you can revoke your key which tells

the world to no longer trust that version of your key. (See Chapter 5 for

more details on how to revoke a key).

Including your Public Key in an e-mail Message

Another convenient method of delivering your public key to someone is

to include it along with your

To Include your Public Key in an e-mail Message

1. Open the PGPkeys window.

2. Select your key pair , then select the Copy option fr om the Edit menu .

e-mail

message.

3. Open the editor you use to compose your

cursor in the desired area, and then choose Paste from the Edit

menu. In some

from the PGPkeys window into the text of your

transfer the key information.

When you send someone your public key, be sure to sign the

That way, the recipient can verify your signature and be sure t hat no one

has tampered with the information along the way.

e-mail

applications, you can simply drag your key

e-mail

messages, place the

e-mail

message to

e-mail

.

Exportin g your Public Key to a File

Another method of distributing your public key is to copy it to a file and

then make this file available to the person with whom you want to

communicate. There are several ways to copy your public key to a file:

• Select the icon representing your key pair from the PGPkeys

window, then choose Export Keys from the Keys menu and enter the

name of the file where you want the key to be saved.

• Select the icon representing your key pair in the PGPkeys window,

choose Copy from the Edit menu and then choose Paste to insert the

key information into a text document.

ALERT

30 Chapter 3: Making and Exchanging Keys

If you are sending your key to colleagues who are using PCs, enter a

name of up to eight initial characters and three additional characters

for the file type extension (for example, e-mail.txt).

Page 39

Obtaining the Public Keys of Others

Just as you need to distribute your public key to those who want to send

you encrypted mail or to verify your digital signature, you need to

obtain the public keys of others so you can send them encrypted mail or

verify their digital signatures. You have several alternatives for

obtaining someone’s public key:

• Get the key from a public key server.

• Add the public key directly from an

• Import the public key from a file.

Since public keys are really just blocks of text, it is really quite easy to

add one to your keyring by importing it fr om a f ile or b y copying it f r om

e-mail

an

keyring. Here is an example of a public key block of text:

message or a key server and then pasting it into your public

e-mail

message.

Getting Public Keys from a Key Server

If the person to whom you want to send encrypted mail is an

experienced PGP user, chances are that they have placed a copy of their

public key on a key server. This makes it very convenient for you to get a

PGP for Personal Privacy, Version 5.0 User’s Guide for the Mac OS 31

Page 40

copy of their most up-to-date key whenever you want to send them mail

and also relieves you from having to store a lot of keys on your public

key ring.

There are a number of public key servers, suc h as the one maintained by

PGP, Inc., where you can locate the keys of most PGP users. If the

recipient has not pointed you to the Web address where their public key

is stored, you can access any key server and do a search for the user’s

name or

include the keys stored on all the other servers.

To Get Someone’s Public Key from a Key Server

1. Open the PGPkeys application from the PGPmenu item in the

2. Choose Find New Keys from the Keyserver submenu of the Keys

e-mail

menubar or by double-clicking the application icon in the Finder.

menu.

The “Search Keyserver” dialog box appears.

address, since all key servers are regularly updated to

3. Enter the

If a public key for the specified user is found, you are asked whether

you want to add it to your public keyring. When you add public

keys to your keyring, the keys will show up in the PGPkeys window

where you can examine them to make sure that they are valid.

e-mail

address or user name to locate the users public key.

Adding Public Keys from e-mail Messages

One convenient way to get a copy of someone’s public key is to have

them include it when they send you encrypted

mail

applications that is supported by the PGP plug-in, then adding the

sender’s public key to your public key ring can be accomplished by

simply clicking a button. For example, if you are using Eudora, and a

32 Chapter 3: Making and Exchanging Keys

e-mail

. If you have an

e-

Page 41

mail message arrives with a block of text containing someone’s public

key, you select PGP Add Keys from the message Plug-ins submenu in

the Edit menu.

If you are using an e-mail application that is not supported by the plugins, you can copy the block of text that represents the public key and

paste it into the PGPkeys window and thus add the key to your public

keyring.

Importing a Public Key from a File

Another method of obtaining someone’s public key is to have them save

it to a file from which you can import it or copy and paste it into your

public keyring. There are several methods of extracting someone’s

public key and adding it to your public keyring.

• Choose Import Keys from the Keys menu and then enter the name

of the file where the public key is stored.

• Open the text document where the public key is stored, select the

block of text representing the key, then choose Copy from the Edit

menu. Then, go to the PGPkeys window and choose Paste from the

Edit menu. The key will then show up as an icon in the PGPkeys

window.

Verifying the Authenticity of a Key

When you exchange keys with someone, it is sometimes hard to tell if

the key really belongs to that person. PGP provides a number of

safeguards by all owing you to chec k a key’ s authenticity, to vouch for its

integrity and to warn you if you are using a key that is not completely

trusted.

One of the major vulnerabilities of public key enrcryption systems is the

ability of some eavesdropper to mount a “man-i n-the-m iddle ” attac k by

replacing someone’s public key with one of their own. In this way they

can intercept any encrypted

using their own key, then encrypt it again with the person’s real key and

send it on to them as if nothing had ever happened. In fact, this could all

be done automatically through a sophisticated computer program that

stands in the middle and deciphers all of your correspondence.

PGP for Personal Privacy, Version 5.0 User’s Guide for the Mac OS 33

e-mail

intended for that person, decrypt it

Page 42

Based on this scenario, you and those with whom you exchange e-mail

need a way to determine whether you do indeed have legitimate copies

of each others keys. The only way to be complet ely sur e that a public key

actually belongs to a particular person is to have the owner copy it to a

diskette and then physically hand it to you. Since you are not always

within close enough proximity to personally hand a disk to someone,

you will generally exchange public keys via

public key server.

Even though these are somewhat less secure methods of exchanging

tamper-proof keys, you can still determine if a key really belongs to a

particular person by checking its digital fingerprint, a unique series of

numbers generated when the key is created. By comparing the

fingerprint on your copy of someone’s public key against the fingerprint

on their original key, you can be relatively sure that you do in fact have a

valid copy of their key.

The most definitive way to check a key’s fingerprint is to call the person

and have them read their fingerprint over the phone or have them give

you the key on a diskette in person.

Once you are absolutely convinced that you have a legitimate copy of

someone’s public key, you can then sign their key. By signing someone’s

public key with your private key, you are signifying to the world that you

are sure the key belongs to the alleged user. For instance, when you

create a new key, it is automatically certified with your own digital

signature, since it is a reasonably safe assumption that the person

creating the key is in fact the true owner. The reason for signing your

own key is to prevent anyone from modifying it which would

immediately invalidate your signature.

e-mail

or get them from a

PGP users often have other trusted users sign their public keys to further

attest to their authenticity. For instance, you might send a trusted

colleague a copy of your public key with a request that they certify and

return it so you can include their signature when you post your key on a

public key server. Now, when someone gets a copy of your public key,

they don’t necessarily have to check the key’s authenticity themselves,

but can instead rely on how well they trust the person who signed your

key. PGP provides the means for establishing this level of trust for each

of the public keys you add to your public keyring and shows the le vel of

trust associated with each key in the PGPkeys window. This means that

34 Chapter 3: Making and Exchanging Keys

Page 43

when you get a key from someone whose key is signed by a trusted

introducer, you can be fairly sure that the key belongs to the purported

user.

For details on how to sign keys and validate users, see Chapter 5.

PGP for Personal Privacy, Version 5.0 User’s Guide for the Mac OS 35

Page 44

36 Chapter 3: Making and Exchanging Keys

Page 45

Chapter 4

Sending and Receiving Private E-mail

This chapter explains how to encrypt and sign the e-mail you send

to others and decrypt and verify the e-mail others send to you.

Encrypting and Signing E-mail

The quickest and easiest way to encrypt and sign e-mail is with an

application supported by the PGP plug-ins. Although the procedure

varies slightly between different

encryption and signing process by clicking the appropriate buttons in

the application’s toolbar. In addition, if you are using an application

such as Eudora, that supports the PGP/MIME standard, you can

encrypt and sign your

when you send or receive your

e-mail

e-mail

messages as well as any file attachments

e-mail

applications, you perform the

.

If you are using an

plug-ins, you can encrypt and sign your

which is available in most popular text-based applications. When

accessing this menu from the Finder, you can encrypt and sign or

decrypt and verify files and even entire folders.

As an alternative to the other interfaces, you can also use the PGPtools

window to encrypt and sign text and files. When using this interface to

encrypt and sign text, you copy the text to the clipboard, perform the

desired operation by choosi ng the appropriate button and then copy the

contents back to your application. You can also encrypt and/or sign a

selected portion of text or even files by dragging them to t he appropriate

button.

PGP for Personal Privacy, Version 5.0 User’s Guide for the Mac OS 37

e-mail

application that is not supported by the PGP

e-mail

messages via PGPmenu

Page 46

NOTE:

If you do not se nd y our e mai l imm ediatel y but inste ad tempo rarily store

it in your outbox, you should be aware that when using some email

applications, the information will not be encrypted until the email is

actually transmitted. Befor e queu ing encrypted messages you sho uld

check to see if your application does in fact encrypt the messages in

your outbox. If it does not, you might want to consider encrypting the

message via the clipboard before queuing it in the outbox.

Encr yptin g and Signing with Supported e-mail Applications

When you are encrypting and signing with an e-mail application which

is supported by the PGP plug-ins, you have two choices depending on

what type of

e-mail

communicating with other PGP users who have an

that supports the PGP/MIME standard, you can take advantage of a

PGP/MIME feature to encrypt and sign your

file attachments automatically when you send them. If you are

communicating with someone who does not have a PGP/MIMEcompliant e-mail application, you should encrypt your messages and

file attachments with PGP/MIME turned off to avoid any compatibility

problems. You can turn this feature on and off by selecting the

appropriate options from the e-mail pane of the Preferences dialog box

application the recipient is using. If you are

e-mail

e-mail

application

messages and any

To Encrypt and Sign with Supported e-mail Applications

1. Use your e-mail application to compose your

e-mail

message just as

you normally would.

2. When you are finished composing the text of your

e-mail

message,

specify whether you want to encrypt and sign the text of your

message by clicking the encrypt and/or si gn buttons in the menuba r.

If you encrypt and sign your e-mail on a re gular basis, you can cr ea te

a stationary file with the encrypt and sign settings turned on. See the

manual or help system for information on how to set up a stationery

file.

38 Chapter 4: Sending and Receiving Private E-mail

Page 47

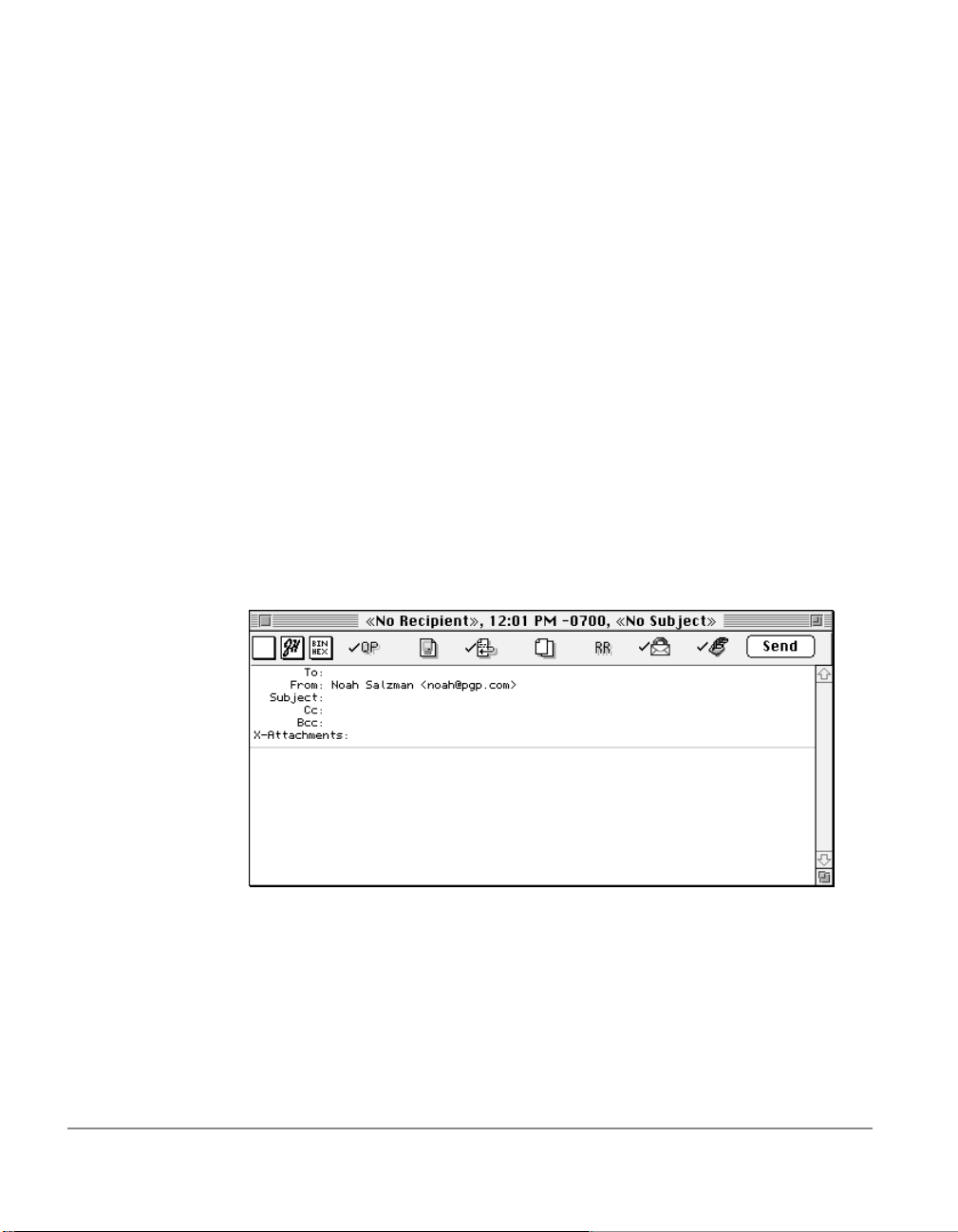

Encrypt button

Sign button

Sign

Encrypt

When you click one of these buttons, a c heck b ox appe ars next to the

selected buttons to indicate the operations you want to perform.

3. After composing your message, send your

e-mail

as you normally

do.

If you have elected to sign the encrypted data, the Passphrase dialog

box appears requesting your passphrase before the mail is sent.

4. Enter your passphrase and then click OK.

PGP for Personal Privacy, Version 5.0 User’s Guide for the Mac OS 39

Page 48

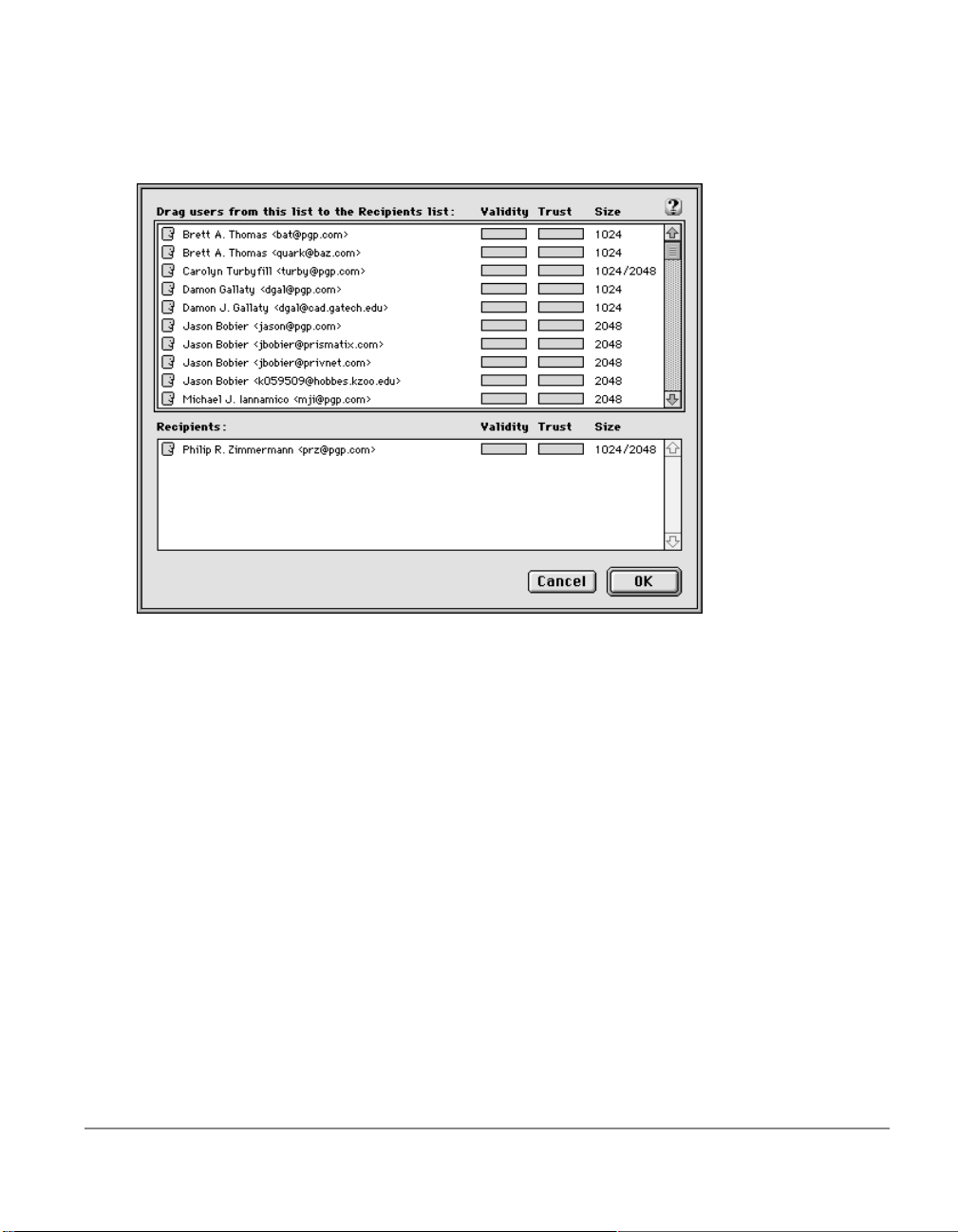

As long as you have a copy of the public keys for every one of the

recipients, the appropriate keys are used. However, if you specify a

recipient for whom there is no corresponding public key, the Key

Selection dialog box appears so you can specify the desired key.

5. Drag the public keys for those who are to receive a copy of the

encrypted

e-mail

message into the “Recipients” list box.

The “Validity” bar indicates the minimum level of confidence that

the public keys in the Recipient list are valid. This validity is based

on the signatures associated with the key and t he trust indicates how

well you can rely on the owner of the key to vouch for the

authenticity of another users key. See Chapter 5 for more details.

NOTE:

40 Chapter 4: Sending and Receiving Private E-mail

If you are not using PGP/MIME, you must encrypt any files you want to

send as attachments from the Finder before sending your message.

Page 49

Encrypting and Signing with PGPmenu

If you are using an

PGP plug-ins you can encrypt and sign your

can also encrypt files and entire directories while you are in the Finder.

NOTE

To Encrypt and Sign text with PGPmenu

1. If you want to encrypt text, use your application to compose your

text just as you normally would.

2. When you are through composing the text, click the desired

operation from the PGPmenu to encrypt and/or sign the message.

If PGPmenu does not show up in your application , you will need to add it from

the PGPmenu pane of the Preferences dialog box.

e-mail

application that is not yet supported by the

e-mail

with PGPmenu. Y ou

PGP for Personal Privacy, Version 5.0 User’s Guide for the Mac OS 41

Page 50

When you are encrypting, the Recipients dialog box appears.

3. Click and drag each of the public keys for those who are to receive a

copy of the encrypted

then click OK. The Validity and Trust bars indicate the level of

confidence that the public keys in the Recipient list are valid. This

validity is based on the signatures associated with the key and the

trust indicates how well you can rely on the owner of the key to

vouch for the authenticity of another users key. See Chapter 5 for

more details.

e-mail

message into the Recipients list box,

When you are signing, the Passphrase dialog box appears.

4. Enter your passphrase and click OK.

42 Chapter 4: Sending and Receiving Private E-mail

Page 51

5. Send your mail as you normally do.

To Encrypt and Sign Files with PGPmenu

1. While in the Finder, click the desired operation from the PGPmenu

to encrypt and/or sign a file or the contents of a folder.

When you are encrypting, the Recipients dialog box appears.

2. Click and drag each of the public keys for those who are to receive a

copy of the encrypted

then click OK. The Validity and Trust bars indicate the level of

confidence that the public keys in the Recipient list are valid. This

validity is based on who has signed the key and how trustworthy

PGP for Personal Privacy, Version 5.0 User’s Guide for the Mac OS 43

e-mail

message into the Recipients list box,

Page 52

you consider those users to vouch for the authenticity of the key. See

Chapter 5 for more details and Chapter 6 for a discussion of

Encryption Basics.

When you are signing, the Passphrase dialog box appears.

3. Enter your passphrase and click OK.

Encrypting and Signing from PGPtools

If you are using an

PGP plug-ins, you can encrypt and sign your

can also encrypt files.

To Encrypt and Sign Text from PGPtools

1. Use the editor supplied with your

ite word processing program to compose the message you want to

send.

2. When you are ready to send the message, select the text you want to

encrypt or choose Select All from the Edit menu available in most

applications.

3. Choose Copy from the Edit menu to copy the contents of your

message to the Clipboard.

You should note that anytime you copy or cut text in your

application, it is temporarily stored on the Clipboard.

e-mail

application that is not yet supported by the

e-mail

e-mail

application or your favor-

with PGPtools. You

44 Chapter 4: Sending and Receiving Private E-mail

Page 53

4. Open the PGPtools window and click Encrypt or Encrypt & Sign.

The Open dialog box appears:

5. Select the Use Clipboard button to specify that you want to encrypt

the text stored on the clipboard. The “Key Selection” dialog box

appears:

6. Click twice or drag the public keys for those who are to receive a

copy of the encrypted

PGP for Personal Privacy, Version 5.0 User’s Guide for the Mac OS 45

e-mail

message into the Recipients list box.

Page 54

The Validity and T r ust bars indicat e the minimum level of confidence

that the public keys in the Recipient list are valid. This validity is

based on the signatures associated with the key and the trust

indicates how well you can rely on the owner of the key to vouch for

the authenticity of another users key. See Chapter 5 for more details

7. Click OK when you have selected the appropriate users.

If you have elected to sign the message, the PGP Signing Passphrase

dialog box appears requesting your personal passphrase for your

default private key.

8. Enter your passphrase and click OK.

9. Return to your

from the Edit menu. This will copy the encrypted message back into

e-mail

your

10.Send your

To Encrypt and Sign Files from PGPtools

If you plan to send an encrypted file as an attachment with your

message, or if you just want to encrypt a file to protect it on your own

computer, you do so from PGPtools. Here are the steps you follow to

encrypt and/or sign a file from the desktop:

1. Start PGPtools.

2. When the PGPtools window appears, drag each file or files that you

want to encrypt onto the Encrypt or Encrypt & Sign button.

You can select multiple files, but you must encrypt and sign each of

them individually.

e-mail

application.

e-mail

application and choose the Paste command

to the intended recipient(s).

e-mail

46 Chapter 4: Sending and Receiving Private E-mail

Page 55

3. The “Recipients” dialog box appears where you can select the

recipient’s keys for the file you are encrypting or signing:

.

4. Select the public keys by clicking twice or dragging them to the

Recipients list, then click OK.

Your encrypted files will appear on the Desktop or in the folder in

which you were working as represented by the following icons..

detached signatureencrypted as textencrypted as binary

Decr ypting and Verifying E-mail

The quickest and easiest way to decrypt and verify the

you is with an application supported by the PGP plug-ins. Although the

procedure varies slightly between different

you are using an

e-mail

application supported by the plug-ins, you can

e-mail

perform the decryption and verification process by clicking a button in

your application’s toolbar. In addition, if you are using an application

PGP for Personal Privacy, Version 5.0 User’s Guide for the Mac OS 47

e-mail

sent to

applications, when

Page 56

that supports the PGP/MIME standard, you can decrypt and verify your

e-mail

in your message.

messages as well as any file attachments by just clicking an icon

If you are using an

plug-ins, you decrypt and verify your

Clipboard. Also, if your

must decrypt them separately from the Macintosh desktop.

e-mail

e-mail

application that is not supported by the PGP

e-mail

includes encrypted file attachments , you

messages via the

Decrypting and Verifying from Supported e-mail Applications

If you are communicating with other PGP users, and they have

encrypted and signed their mail using the PGP/MIME standard, a lock

icon will appear when you open your e-mail.

In this case, you can decrypt and verify the message and any attached

files by si mply double-clicking this icon.

48 Chapter 4: Sending and Receiving Private E-mail

Page 57

If you are receiving e-mail from someone who is not using a PGP/

MIME-compliant e-mail application, you will see a bock of encrypted

text.

In this case, you can decrypt the ciphertext by clicking the open

envelope icon in the message window. Also, if there are any encrypted

file attachments, you decrypt them from with the PGPtools application

or with PGPmenu from the Finder.

PGP for Personal Privacy, Version 5.0 User’s Guide for the Mac OS 49

Page 58

To Decrypt and Verify from Supported e-mail Applications

1. Open your

e-mail

message just as you normally do. If someone has

sent you mail using PGP/MIME, you will see the lock icon. Click on

the lock icon or the attached file. If the message was sent without

using PGP/MIME, then your message will contain the encrypted

text as well as any digital signature.

To decrypt and verify the contents of the

e-mail

message, click the

open lock button located in your application’s menubar.

decrypt and verify

.

The Enter Passphrase dialog box appears requesting that you enter

your passphrase:

2. Enter your passphrase and click OK.

50 Chapter 4: Sending and Receiving Private E-mail

Page 59

The message and any attachments are decrypted. If the message is

signed, a dialog box indicates whether the signature is valid.

3. At this point, you can save the message in its decrypted state, or you

can discard the changes and revert to the original encrypted version

so it remains secure.

Decrypting and Verifying from PGPmenu

If your

easily decrypt your

You can also decrypt and verify file attachments and even entire

directories when you are using PGPmenu from the Finder.

To Decrypt and Verify Text from PGPmenu

1. In the editor supplied with your

2. Choose Decrypt/Verify from PGPmenu. The PGP Enter Passphrase

3. Enter your passphrase and then click OK.

e-mail

encrypted text.

In most applications, choose Select All to highlight all of the text.

dialog box appears requesting that you enter your passphrase:

application is not supported by the PGP plug-ins, you can

e-mail