Page 1

pass

Pass Rushmore

Background

In the 1950’s most audiophiles only had

maybe 10 watts of tube amplifier available, but

they achieved realistic concert performances

with loudspeakers whose design emphasized

powerful and efficient motor assemblies and

diaphragm materials chosen for musicality, low

mass, and large radiating surfaces. Enclosures

were designed with the same thought that goes

into musical instruments, with a live harmonic

characteristic and an appreciation for fine

wood craftsmanship. Many of these products

endure as classics, and are still highly prized by

audiophiles as treasures from a golden age. They

were as much a result of refined taste and trial

and error as they were science and engineering.

For years we have asked ourselves why these

old designs are so good, and why modern

high-end audio does not show all the audible

improvements to be expected of 50 years of

technological advances.

In the 60’s and 70’s, high power amplifiers

became available, and loudspeaker design took

a left turn onto the road it follows today. With

mighty solid state amplifiers at the designer’s

disposal, efficiency was no longer an issue, and

the design goals revolved around raising the

power handling ratings and sacrificing efficiency

in order to deliver low bass frequencies in small

enclosures. Never mind that the bass was

boomy and that the music sounded like it was

pushed through a sock; it fit on a shelf, and it

used up the higher power of the amplifier the

industry was eager to sell.

Many of the differences between then and

now are obvious. With efficiency as a priority,

classic high-end loudspeakers had sensitivities

in the range of 100 dB/watt. The old designs

used expensive magnetic circuits and tightly

toleranced motor assemblies to achieve high

force from a small amount of electrical current,

and they coupled these to lightweight paper

cones whose sonic signature was the result of

much trial and error – more art than science and

engineering.

Today, most speakers are about 87 to 92 dB/

watt, which is about 1/10 the acoustic output of

the old classics. This is the difference between

10 and 100 watts of amplifier for the same

level. The cones are heavy and the magnets

are working into wide voice coil gaps. Why is

this? It costs a lot less to do it this way, and

also loudspeaker enclosures can be made less

Page 2

conspicuous while retaining some low frequency

response. Much of loudspeaker science operates

on the presumption of the cone material as a

rigid piston, which plays well into the use of

heavy, thick materials in order to achieve the

character of a piston. The high mass of the

cone results in slow attack and decay response

to impulses from the amplifier, but this has been

considered an acceptable trade off. Of course,

there really is no such thing as a loudspeaker that

acts as a true piston.

The old designers knew they were never going

to get a really rigid neutral piston, so they

researched cone materials that were light, well

damped, and whose deviations from the ideal

were at least musical. This philosophy was

in keeping with the approach to the old tube

amps as well; they didn’t measure that great,

but their faults were at least musical and fairly

inoffensive. The old designers measured and

listened carefully, and were persistent. Most of

them had taste, and they knew what they wanted

when they heard it.

These light diaphragms and efficient motors

have a very dynamic quality. From silence they

spring to life in response to musical transients.

Well done, they articulate infinitesimal details

and have a warm, spacious, easy character. The

paradox is, of course, that modern designs in

many ways are not as sonically pleasing as the

old classics. For all the power available, they

have traded off dynamic range, transient attack

and decay, and articulation. They have sold their

musical souls, and they sound uneasy about it.

The old speakers came in big enclosures, made

of spruce, maple and other acoustically live

woods designed to get the last bit of bottom

end performance from a big lightweight paper

cone. Large bass-reflex boxes and horns filled

audiophile listening rooms. The wood in the

enclosures was flexible and had a sonic signature

of its own. Like the material used in the paper

cones, it was chosen for sonic harmony with the

drivers, and was the object of craftsmanship in

construction and finish.

Today? Monkey caskets: Medium density

fiberboard, or worse, particle board rules the

marketplace. It’s cheap, easy to machine, and

is supposed to be acoustically dead. Actually,

it pretty much is…… dead, lifeless and

uninteresting.

As speakers have gotten less efficient, amplifiers

have gotten bigger and more powerful. In

an evolution similar to speakers, amplifiers

achieved better specifications through the use

of more complex circuitry and greater amounts

of feedback. The old simple ways of building

good amplifiers gave way to a specifications race,

and similar to the loudspeaker paradox, we find

ourselves with complex circuits achieving lots

of feedback in order to correct for the poorer

linearity of more complex circuits.

The big difference between then and now is that

much of the industry relies more on science and

engineering than persistence and good taste in

the development of products. Even the most

ardent subjectivist designer has a rack of test

equipment, and he keeps at least one eye on it

all the time.

The Pass Rushmore loudspeaker design

originated with speculation as to how

loudspeakers would have evolved if in the 60’s

designers had stayed with high efficiency drivers,

Page 3

industries. We used the prototype XVR1

crossover network to mate these to each other

in test systems in order to evaluate each driver

objectively and subjectively, separating the wheat

from the chaff. Over the course of two years of

testing, we isolated a few candidate components

from hundreds. No horn driver made the cut,

nor did any dome. The bass to upper midrange

drivers that met our requirements ended up

all paper cone type drivers, and only ribbon

tweeters satisfied us at the top two octaves.

We spent a year with the permutations of

systems which could be built with these drivers

in combination with each other, tweaking,

listening, and measuring, until we settled on the

best combination of parts and the crossover

and amplifier characteristics most ideal to each

component.

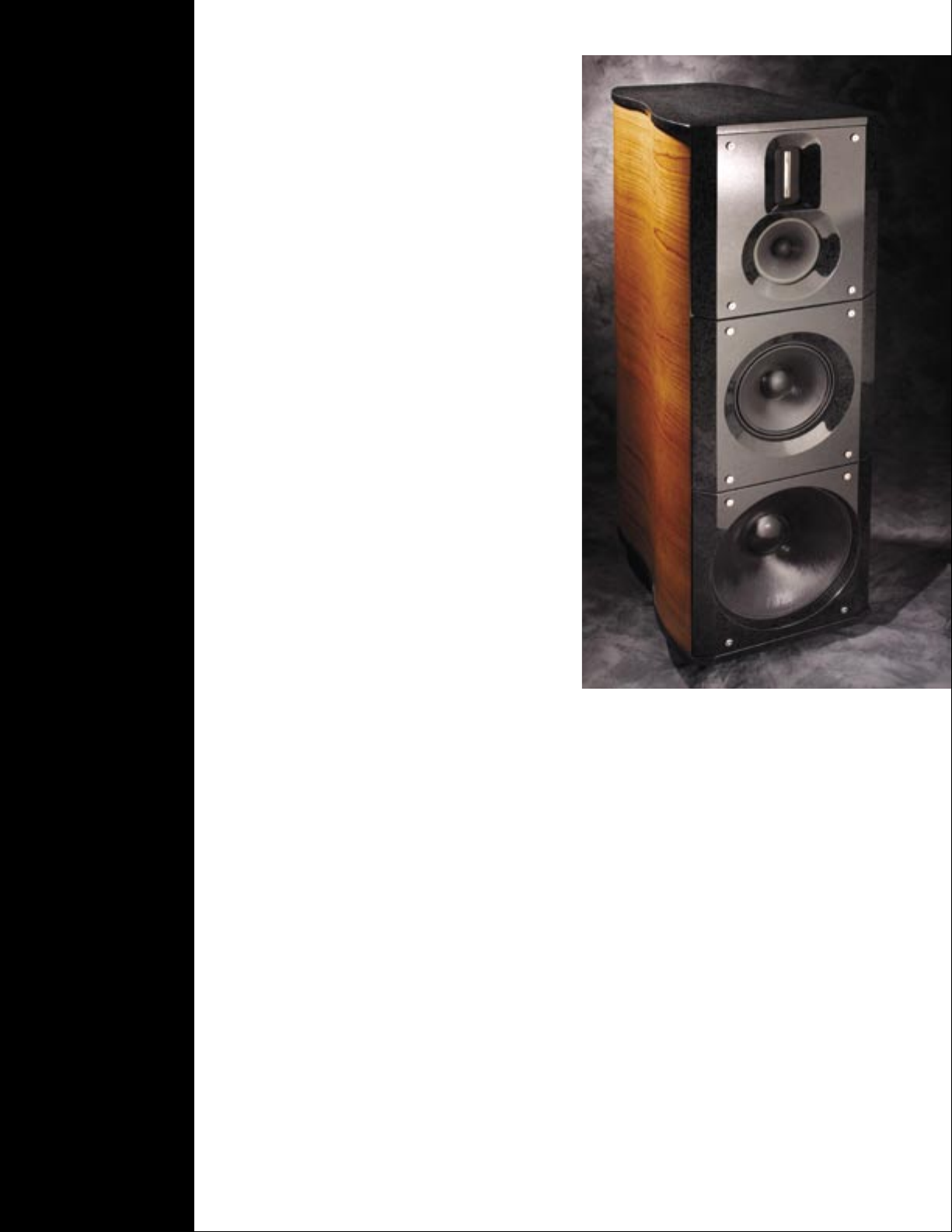

The result is a four-way system, with a 15 inch

deep bass driver, a 10 inch mid bass driver, and a

6 inch midrange, and a ribbon tweeter. The bass

driver is 97 dB/watt efficient, and the remaining

drivers are at least 98 dB/watt. The cone drivers

are all high quality professional drivers rated at

high wattage levels which by coincidence work

very well together. As a group, they were the

best we could find.

relatively low amplifier power and live sounding

enclosures.

So what are we doing here that’s different?

Some parts of this design are similar to other

commercial offerings, but no product embodies

such a comprehensive integration of design

and technique with this level of taste and

performance.

Very Sensitive Drivers

When we began this project over three years

ago, we decided high efficiency drivers at least

96 dB efficient were the only ones likely to meet

our criteria for dynamic range, inner detail, and

transient response. This observation comes

through strictly personal experience with a

large number of successful classic designs.

We purchased or borrowed pairs of every

component that met this specification that

we could find, which included cones, horns,

domes, and ribbons. This was a lot of drivers,

drawn from both the consumer and pro audio

Single-Ended Class A power amplifier

devoted to each driver

The bottom end is powered by an Aleph X

balanced single-ended Class A amplifier, a cousin

of the newly released Pass XA series. Using the

two most important patented topologies available

to Pass Labs, it combines the warmth and

sweetness and detail of the Aleph series singleended output stage with the dynamic range and

control of the Supersymmetric topology of the

Pass X amplifiers.

The three mid-bass, mid-range, and highend amplifiers are conventional Aleph series

circuits, best suited to elicit the best qualities of

articulation and imaging, warmth and top end

sweetness of these very dynamic loudspeaker

drivers.

Having only two stages, these amplifiers embody

the audiophile quest for the most realistic sound

through minimalism and purity of signal path.

Single-ended Class A amplifiers have what is

known as a monotonic character; they continue

to improve as the power level goes down.

Page 4

Thus, the first watt is the best watt, and they

give a great performance at ordinary volume

levels. This character greatly complements very

sensitive drivers, and Rushmore invites you to

listen at normal loudness. You do not have to

play music at abusive levels to achieve detail and

drama with this loudspeaker.

Each amplifier is adjusted for the specific

voltage, current and gain requirements of each

driver. The cone drivers are direct coupled to the

amplifiers with no intervening passive circuitry to

make maximum use of the damping provided by

the amplifier and to assure minimum distortion

and signal loss.

The heat sink for the amplifiers is a 4 ft. long

finned extrusion that embodies the rear of

the loudspeaker from bottom to top. During

operation, it reaches approximately 55 degrees

C. in the area containing the 20 power Mosfets

which populate the 4 channels of amplification.

The power supply to the amplifiers delivers a

continuous constant 300 watts to the Class A

output stage during operation. This draw is

constant regardless of signal level, and drops

only when the speaker is powered down. The

capacitor filter bank contains 240,000 uF

capacitance and uses dual CLC pi filters to

reduce ripple and noise by a factor of 20 dB

lower than a conventional unregulated supply.

The bass amplifier is rated at 80 watts into the

woofer, the mid-bass amplifier is 20 watts, the

mid-range amplifier is 20 watts, and the ribbon

tweeter amplifier is rated at 20 watts, all singleended Class A.

The absolute maximum output of the speaker

at 1 meter is approximately 120 dB with musical

material.

Quad Amp Crossover

The filter characteristics for each driver are

determined in passive filter networks prior to

each of the four amplifier inputs per speaker.

Their specific characteristic has been trimmed

and evaluated through trial and error over a long

period of time in many rooms with many listeners

and confirmed by measurement equipment. For

best transient and phase response, the mid-bass

and mid-range band-pass filters are single-pole

types, while the bass driver sees a 2-pole lowpass filter at 22 Hz and the ribbon tweeter is

crossed with 2 poles at 8 KHz. None of these

filters uses feedback, positive or negative.

The result is a flat response that falls off at 20

Hz on the bottom and 40 KHz, above the top

of the audio band.

The individual level of each driver is calibrated,

but each has an adjustable level control

allowing for +/- 3 dB adjustment for different

environments and taste.

The input of the speaker can be made from a

line level source into either a balanced input or

single-ended input at the rear of the speaker.

The input impedance is 20 Kohm balanced and

10 Kohm single-ended. The balanced input

common mode rejection offers 40 dB of noise

rejection.

The gain of the input through the output has

been calibrated to 100 dB output at 1 meter for

1 volt input.

Granite and Piano Enclosure

We believe that this much achievement should

be housed in the finest temple, so we went to

woodworkers versed in the wood forming and

finishing of pianos. The curved sides of the

Rushmore are made of 9 individual layers of

veneer material formed and cured in a vacuum

press and mated to a 1.25 inch thick solid front

baffle faced with 0.75 inch thick granite. The top

and bottom are panels of 0.75 inch thick granite.

The rear of the loudspeaker consists entirely of

an extruded, machined and anodized heat sink

which holds all the electronic components.

The front baffle of the speaker is made

acoustically dead so that the drivers feel a firm

unyielding mounting surface, but the rest of the

enclosure has been allowed to remain relatively

live, and contributes in its own subtle way to the

overall sound of the speaker.

The Rushmore weighs approximately 300 lbs,

is 50 inches high, 18 inches wide at its widest

point, and 28 inches deep. It has been designed

by Nelson Pass, Kent English, and Desmond

Harrington.

pass

Pass Laboratories, PO Box 219, Foresthill, CA 95631 - 530.367.3690 - www.passlabs.com

Loading...

Loading...