Page 1

Page 2

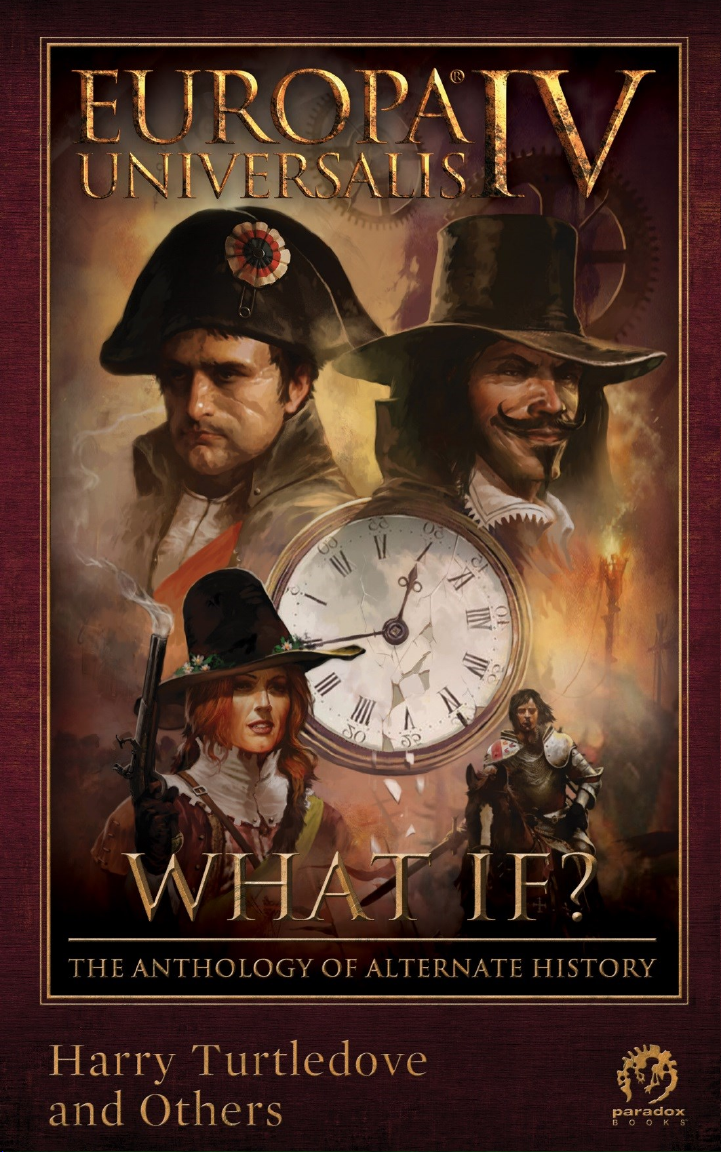

WHAT IF?

THE ANTHOLOGY OF

ALTERNATE HISTORY

by

Harry Turtledove and Others

Page 3

Pressname: Paradox Books

Copyright © 2014 Paradox Interactive AB

All rights reserved

Authors: Harry Turtledove, Janice Gable Bashman,

Lee Battersby, Luke Bean, Raymond Benson, Felix

Cook, Aidan Darnell Hailes, Jordan Ellinger, James

Erwin, Anders Fager, David Parish-Whittaker, Rod

Rees, Aaron Rosenberg

Editor: Tomas Härenstam

Cover Art: Ola Larsson

ISBN: 978-91-87687-50-1

www.paradoxplaza.com/books

Page 4

CONTENTS

Introduction – Troy Goodfellow ................................... 1

Company – Luke Bean .................................................... 4

The More it Changes – Harry Turtledove ................. 24

A Single Shot – Rod Rees ............................................ 43

The Buonapartes – Anders Fager ............................... 64

Let No Man Put Asunder – Aaron Rosenberg ......... 84

Roaring Girl – David Parish-Whittaker ................... 106

Defeat of the Invincible – Janice Gable Bashman . 132

Rising Sun – James Erwin .......................................... 153

Écureuils – Aidan Darnell Hailes .............................. 171

English Achilles – Jordan Ellinger ............................ 185

The Great Work – Felix Cook................................... 206

To Be Or Not To Be – Raymond Benson .............. 227

The Emperor Of Moscow – Lee Battersby ............. 249

Afterword ..................................................................... 268

Other Titles by Paradox Books ................................. 269

Page 5

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

There is an ongoing debate in academic history

about the value of what they call “counterfactual”

history—the idea that we can learn about how we got

where we are by asking ourselves how things might

have changed if the past took a different road. The

plague doesn’t get to Byzantium. The Germans do

get across the Marne. China doesn’t stop the treasure

fleets. These puzzles ask us to examine what we

mean when say that an historical event was “caused”

by one factor or another.

Academic debate aside, alternate histories undoubtedly provide as much entertainment as they do illumination. Whether it’s a question of seeing how far a

writer can push the “want of a horseshoe nail” or

simply imagining how all of our lives would be different in a world where, say, Hitler stuck to art school, the

possibilities generated by an infinite range of stories

can tickle the imagination.

This is not to say that writing a good alternate history is easy. You must have an interesting starting

point, you must have plausible connections between

1

Page 6

EUROPA UNIVERSALIS IV: ANTHOLOGY OF ALTERNATE HISTORY

events, and you must have an intuitive understanding

of the motivations of men and women, great and small.

Paradox grand strategy games are where history

starts going off the rails the moment you press PLAY,

and, for as long as we’ve made these games, fans have

entertained us with After Action Reports (AARs); descriptions of their experiences in the game, sometimes

with decisions up for community vote. An AAR can be

either a straight summary of what happened on screen

or a deeper meditation on what it is like to live in this

new, computer-generated world, sometimes told from

the perspective of a leader or citizen in this newly generated past. Both approaches have their advocates, but

both are best done with a strong eye to how the past is

always a foreign country.

This anthology is a celebration of the story-telling

power of our games, especially Europa Universalis, a series that launched Paradox Development Studio (and

Paradox Interactive). Strategy games like ours make for

good stories because there are never two experiences

that are remotely identical to each other. Thuringia replaces Austria as the ruler of Central Europe in one

game, in another France bulldozes through the Holy

Roman Empire, and in a third Vienna pulls it all together to rebuild the empire of Charlemagne.

Now imagine an alternate timeline where there is no

Europa Universalis; a dark timeline where an experimental title did not find a global audience willing to

embrace the uncertainties of history and the challenges

of the greatest of men and women. There are still

games, of course, and even strategy games. But they are

likely both less grounded in our common love for our

history and less celebratory of the wonderful improvisational nature of gamers.

2

Page 7

INTRODUCTION

Enough sadness. We bring you stories—tales of

great deeds, small heroisms and how everything could

have been different.

Troy Goodfellow

Assistant Developer

Paradox Interactive

3

Page 8

EUROPA UNIVERSALIS IV: ANTHOLOGY OF ALTERNATE HISTORY

COMPANY

By Luke Bean

I first met Duckie Wooler when I was sixteen. He had

come to Mecklenburg to start a war, and I figured I

could get a pack or two of cigarettes out of it. The idea

of being invaded didn’t worry me much. War, as far as

my town was concerned, was the natural state of affairs. Indeed, it was the idea that the invaders might

bring peace that troubled the locals. So when this

strange American showed up waving around a camera

and talking of an age of peace to come, he found nothing but closed doors and pursed mouths. I took pity on

this lonely man, and I do not think it is an exaggeration

to say we saved each other’s lives. Today, of course,

Silas “Duckie” Wooler is the New York Journal’s fabled international correspondent, the man who built

the case for the Pacification of Germany. And though

my name, Erich Kalb, is little remembered, I too am

famous: I am the subject of Mr. Wooler’s most iconic

photograph, “The Boy and the Banner.”

4

Page 9

COMPANY – LUKE BEAN

In 1950, Mr. Wooler asked me to write a short foreword for the 20th anniversary edition of Duckie in Ger-

many. (It is a fascinating work of journalism, and I strongly

encourage you to read it.) I found it difficult to bottle my

feelings on the topic. The story of my travels as Duckie’s

translator meant little to me without the context of how

I had arrived at that point in my life. Soon my short foreword had exploded into a hundred pages of anecdotes,

arguments, and explanations. “If you want to make me

look like an idiot,” Duckie eventually told me, “You can

do it in your own damn book.”

With all respect to Mr. Wooler, I believe there is an

error at the heart of his reporting on Germany. My world

was not divided into predatory mercenaries and innocent

victims. The companies maintained their grip on Germany by making everyone an accomplice to their crimes.

At some point, we had all housed them, fed them, traded

with them, fought for them. Everyone knew their local

company men, and counted family and friends among

them. When a boy turned thirteen, Mecklenburg’s largest

company, the Duke’s Rifles, would come to their door.

“Fight with us,” the sergeant would say, “You’ll come

home rich or you’ll come home in a box, but either way

you’ll be a man.” They wouldn’t actually waste effort car-

rying your coffin home, but you understood. Duckie

once asked me why people didn’t turn on the companies.

The question made me laugh. Who was there to turn? We

were the companies, every last one of us.

1. The Balloon

One of my earliest memories is of a hot air balloon. I

was in town with my mother when it appeared in the

distance. She lifted me onto her shoulders to see. We

5

Page 10

EUROPA UNIVERSALIS IV: ANTHOLOGY OF ALTERNATE HISTORY

walked around like that, Mother going about her business and me craning my neck to always keep an eye on

the distant balloon, as if it was waiting for a chance to

slip away. When the balloon came closer, Mother took

me off her shoulders and told me not to look at it anymore, but I looked anyway, and she didn’t stop me.

Three men dangled from nooses tied to the basket.

Mother needn’t have worried about me. I thought they

were just taking a ride.

I still don’t understand this. It’s clear the hangman

wanted everyone to see his handiwork. If it could be

read as a threat, that I could accept. “This is what hap-

pens if you resist conscription!” “These men collaborated with Wehrwolves.” Cause and effect. But if the

balloon knew who hung those men, or who they were,

or what they did, then it wasn’t telling. Maybe someone

just wanted death to remain familiar to us, so we would

not recoil from its touch.

2. The Lübeck Watch

I grew up near Grevesmühlen, on the very edge of

company lands. To the east was Hansestadt Wismar, to

the west Hansestadt Lübeck. The Hanseatic Cities

were an object of fear and fascination for me, lands of

unimaginable debauchery. It was held as unimpeachable fact at my school that the merchant princes of the

Hansa considered the flesh of children a fine delicacy,

and nearly everyone had a friend whose cousin had

been sold to Lübeck to be devoured. But alongside the

lurid stories, there was the recognition that these

strangers were somehow like us. People from Russia or

England or the United Kingdoms seemed unimaginably alien, but our wayward brothers talked like us and

6

Page 11

COMPANY – LUKE BEAN

traded with us. They sung foreign tunes in our native

tongue. This combination of strangeness and familiarity excited me. Lübeck was a wicked and dangerous

place, and I wanted desperately to see it, to slouch between cinemas and cabarets and strangers’ bedrooms

through streets foggy with cigar smoke.

But nobody was allowed into the Hanseatic Cities.

The Rifles didn’t want us getting seduced by their decadent ways. Thinking too much about the outside

world was discouraged. We were told history had

ended with Wallenstein, and outside Germany nothing

of interest had happened ever again. When the Duke’s

Rifles raided beyond Germany, they would target rich

Dutch cities, weak Polish towns—some companies

braver and more foolish than the Rifles even crossed

west into the United Kingdoms before the wall went

up—but the Hanseatic Cities were untouchable. They

bought the companies’ plunder, processed our poppies, and made the money flow. We were expected to

hate and fear them, but not to live without them.

There was a lieutenant in the Rifles, Erich Gersten,

who spent time with my mother. She often had men

over; it kept her in good standing with the Rifles. Most

of them ignored me, but Erich was kind to me, and I

think Mother loved him a little bit for it. He acted like

it was terribly significant that we had the same first

name. “We Erichs have to stick together,” he would

tell me. “Listen to your mother and fight bravely for

your company and you’ll do our name proud.” Some-

times I liked to imagine he was my father, and I was

named after him, but my mother said that wasn’t true.

Erich was more pretty than handsome, and could

have almost been mistaken for a woman without his

sleek red beard. He often tried to keep his face from

7

Page 12

EUROPA UNIVERSALIS IV: ANTHOLOGY OF ALTERNATE HISTORY

smiling, but it always found a way. I’d seen Mother get

angry with him for laughing when she banged her head

on a doorframe, things like that—he wasn’t a sadist, he

just couldn’t help but find things funny. Erich loved

boasting about his adventures, and I loved listening to

him. He was proud to be a member of the Rifles. This

gentle, happy man was surely responsible for more

deaths than he could remember, but that was just part

of the job. When he paced back and forth making up

stories about daring raids and desperate escapes, I

didn’t doubt for a moment that I was going to be a

company man with the Rifles, and I was going to follow him into battle.

One of Erich’s most sacred duties was the Lübeck

Watch. Once a year he would gather together a band of

fifteen trusted men from all over Mecklenburg. They

would meet in the Hart’s Head Tavern and speak in whispers just loud enough to make sure everyone knew they

had secret business. When night fell, they would buy everyone a round of drinks, swear them to secrecy, and

march off towards Lübeck. They would return the next

day, nodding grimly to each other. I could only imagine

they were infiltrating Lübeck to some unknown (but pre-

sumably exciting) end. I couldn’t get Erich to tell me anything about the Lübeck Watch. “I was making sure

Lübeck’s still there,” he said blandly. “It is.”

When I was thirteen I was short for my age, with a

young face. If I couldn’t look like a man, I was deter-

mined to at least act like one, which to my mind mostly

involved fighting over imagined insults. The Rifles

weren’t shy about wasting boys my age as cannon fodder, but I was regarded as officer material. I was just

annoyed that it meant they would not take me with

them into combat. So when Erich Gersten came to my

8

Page 13

COMPANY – LUKE BEAN

door in full uniform and announced that he was enlisting me for the Lübeck Watch, I was giddy. I expected

Mother to set her jaw and growl her disapproval, but

she nodded calmly.

Erich gave me a uniform. I didn’t care that the

sleeves covered my hands. I trailed his band of men,

trying to match their gait and catch their jokes. I

couldn’t do either very well, so I ended up spending

most of the journey to Lübeck petting the pack mule.

We left the road before reaching the city and stopped

in a grove of trees. The sloping fortifications in the distance marked the end of company lands.

Erich’s men began unpacking the mule’s bags. They

contained folding wooden chairs. Everyone took one,

and we marched out of the trees, straight towards the

walls of Lübeck. I had no idea what was going on, but

I followed along. We unfolded our chairs and sat them

in a line at the base of the wall. One of the men opened

his backpack and spilled a small pile of rocks on the

ground. Another passed around bottled beer.

Guards started pooling at the top of the fortifications. They were armed, but seemed more curious than

hostile. Erich picked up a stone and flung it up at the

guards. It fell short, scuttling down the wall into the

trench at the bottom. The guards laughed. Some peeled

away to go back to patrols, but others stayed to watch.

Erich handed me a stone and grinned. I flung it as hard

as I could. And so fifteen company men and I sat and

spent hours drinking and flinging stones at the walls of

Lübeck. The guards shouted insults down and we

shouted insults back. Soon my hand was sore and my

elbow numb. I loved it.

It was about an hour before someone managed to

actually hit one of the guards, but the stone struck him

9

Page 14

EUROPA UNIVERSALIS IV: ANTHOLOGY OF ALTERNATE HISTORY

square in the face, splitting the guard’s lip and drawing

an audible yelp of pain. We all hooted and cheered and

lifted the soldier who made the throw into the air like

he’d just taken the city singlehandedly. The crack of rifle fire interrupted our celebration, and one of the folding chairs was split open by a bullet. I wanted to run,

but Erich stopped me. “They’re aiming around us.

Those cowards know what will happen to them if they

provoke the Rifles.” Sometimes the men would wander

off to find more stones, or spend a few minutes swapping jokes and stories, but always they returned to

throwing stones, until late until the night.

We had picked the area clear of stones. Some of the

soldiers had gone to sleep or passed out drunk. I

helped Erich start a campfire. Erich looked away from

the wall and into the fire and was quiet. He smiled to

himself, and for a moment the man who told me adventure stories was replaced with the man who looted

cities for a living. “It’s all well to play at war with them.

But we’re going to do it one of these days. I know people have been saying that for years, but we’re really going to do it. I’m going to reach down those fat bastards’

throats and pull the food right out of their bellies. I’m

going to get myself a Bernardi Autocycle, and I’m going to get your mother a radio.”

That was in 1925. The next summer was the Sack

of Lübeck, and Erich Gersten got his wish.

3. The Brown Banner

The Brown Banner was a tradition handed down to the

Duke’s Rifles from the Sixty Years’ War. When the Rifles wanted to punish someone, they would peel a strip

of skin off of them, tan it into leather, and sew it onto

10

Page 15

COMPANY – LUKE BEAN

the Banner. Stealing from the Rifles might lose you a

square of skin the size of your hand; betray them and

they’d take every inch of skin. You could tell exactly

how each square of skin was forfeited, because the offender’s name and a short description of their crimes

were etched into every patch. When old Banners grew

too heavy to carry they were retired to the Great Barracks in Schwerin, where they hung from every rafter

like sagging folds on an old woman’s bones.

This is one of Erich Gersten’s stories, most of

which were pure fantasy, but something about the way

he told this one made me believe it. The Duke’s Rifles

were skinning a man for the Banner. He’d murdered

his wife, and if you wanted to murder someone in

Mecklenburg, you’d damn well better belong to the Rifles. When Erich took him from his cage and led him

to the Tannery he was quiet, almost bored-looking.

They laid him on the table and he went limp. The moment the knife touched his back he giggled. As it sliced

his flesh he started laughing. It wasn’t that he didn’t

feel the pain; he was crying and clenching his fists so

tight his fingernails broke skin. But the more the flaying hurt, the more he laughed, cackling so loud it

started to frighten Erich’s men. Erich gagged him, and

that stopped the noise, but they could still see his face

contorted in laughter. In the end they killed him to

make him stop. They took the rest of his skin, but they

didn’t add it to the Banner. The cut was too sloppy—

from the laughing, and from Erich’s hands trembling.

4. History

Schooling was sparse in Grevesmühlen, and ended at a

young age, but my school made sure we took pride in

11

Page 16

EUROPA UNIVERSALIS IV: ANTHOLOGY OF ALTERNATE HISTORY

the parts of our history they were willing to tell us

about. I assume my readers have been raised on the

Western history of Germany: three hundred years of

anarchy and bloodshed. Here is the version I was

taught.

The age of the companies began with the Sixty

Years’ War. Sometimes books called it the Fifty Years’

War, or the Ninety Years’ War, or basically any number

they felt like. It was confusing because the war hadn’t

really remembered to end properly. I suppose one day

nobody showed up to battle, and then it was over.

Every town had its own local heroes from the Sixty

Years’ War, lords or generals or mercenaries who had

taken the town under their wing. Grevesmühlen’s patron savior was none other than the Father of our

Country himself, Albrecht von Wallenstein. Some

called him the First Captain, or the Great Liberator, or

the King Who Broke His Crown. He’d held a hundred

titles from Admiral to Emperor, but he was the Duke

of Mecklenburg, so to us he was the Good Duke. He

led the first companies to war for the Emperor to drive

out the foreigners. But as Wallenstein grew strong, the

Emperor came to fear him, until he tried to have Wallenstein killed. Wallenstein evaded the assassins, and

when the companies saw how the Emperor betrayed

his most loyal servant, they proclaimed Wallenstein the

only man they’d ever kneel to again. Even the companies that fought for the foreigners were impressed by

his promises of land, wealth, and freedom. He deposed

the tyrannical Emperor and drove off the wicked foreigners, and from that day all the people of Germany

grew strong and free. The Duke’s Rifles were directly

descended from Wallenstein’s armies. Plenty of companies could make the same claim, but Grevesmühlen

12

Page 17

COMPANY – LUKE BEAN

had few enough things to be proud of, so we took

whatever we could get.

Among company men, the reverence for Wallenstein was genuine. He had liberated us from the tyranny

of the state. Only in Germany was a man free to do as

he pleased. If you and your brothers were strong

enough, you could take what you wanted. And if you

were weak, well, Germany had no patience for weakness—as it should be. You could pay a company if you

wanted protection, and if you didn’t, it was your loss.

Everyone wanted protection. Once in a while you’d

hear rumors of a town that had the audacity to try to

elect a mayor and govern themselves. This kind of Statist corruption inevitably met swift justice.

Change came slow to Germany. Old companies grew

strong, upstart companies toppled them, and the Duke’s

Muskets started using rifles, but the German way of life

changed little over the centuries between the Sixty Years’

War and my birth. This was by design. The Maxim War

was a typical example of how the companies reacted to

change. In 1889 the Redshanks Company returned from

a contract in Swedish West Africa with ten Maxim machine guns. Within a month, a coalition of twenty-eight

companies had formed to oppose the Redshanks, and by

the end of the year the Redshanks Company had been

wiped out, their company towns sacked, and their Maxim

guns smashed to pieces. There was no point, the captains

all agreed, in turning war into slaughter. One did not need

machine guns to prey on the weak.

But progress whittled away at Germany. Not five

years after the Maxim War, a gunsmith with the Württemberg Knights invented the Daimler Automated Rifle. Unlike the Redshanks, the Knights were willing to

share. The Daim-Aut could be finicky, and if it broke

13

Page 18

EUROPA UNIVERSALIS IV: ANTHOLOGY OF ALTERNATE HISTORY

you might not be able to find the parts to fix it, but it

was a treasured status symbol and a viciously effective

weapon. During the Sack of Lübeck a platoon of Quartered Men with Daim-Auts held off a Swedish landing

force outnumbering them eight to one.

As long as the companies spent all their energy on

raiding and backbiting, they were regarded as a benign

tumor, more harm to operate on than to tolerate. Napoleon had tried to excise the tumor, and look how

that turned out for him! But the Sack of Lübeck

changed everything. Too many companies had cooperated to make it possible, their new automatic weaponry was too powerful, and it was a violation of the

implicit accord between the companies and the Hansa.

But worst of all, nobody had seen the Sack of Lübeck

coming. The companies were no longer predictable.

The West began building the case for surgery.

5. The Wehrwolf

When I was eleven, I came in from the poppy fields

one night and found my mother talking with a man.

This man was different from most of the company

men who buzzed around my mother—filthy and unshaven, but with a preacher’s voice and urgent eyes.

Mother told me to go upstairs, but the man said no, I

should hear this. He spoke to us of a land of freedom

to the south, where a woman did not have to give her

body to the companies, where a boy would only be

called to war to defend his home, not to burn someone

else’s. He didn’t spell it out, but I knew enough to figure out that he was a Wehrwolf.

We ate with him, and then Mother sat with him for

hours, nodding and letting him talk. I had a thousand

14

Page 19

COMPANY – LUKE BEAN

questions, but Mother grabbed my arm, telling me to

close my mouth and open my ears for once. Eventually

she sent me to bed. She came upstairs with me, and

told me to stay in my room until she came for me in

the morning, and to never breathe a word of what happened that night to anyone.

In the morning, the Rifles came to our house. They

thanked my mother and added the man’s skin to the

Brown Banner.

The present German government would have you

believe the Wehrwolves were virtuous liberators. Don’t

believe a word of it. They were no better than the companies. They looted towns, raped women, and conscripted boys just the same; they just did it with Justice’s name on their lips, as if one more blasphemy

could turn their sins to virtue. Whichever Wehrwolf

band sent that man to Grevesmühlen was looking to

expand their turf, not set us free. But even if he was

lying, that man was the first person to tell me about a

world without companies. The second was Duckie.

6. My Hand

The air itself seemed to vibrate with excitement before

a raid departed. We wanted the wealth. We wanted the

food. We wanted the victory. Every indignity the Rifles

ever inflicted on Mecklenburg was forgiven in the

weeks before and after a raid. I practiced my aim until

my trigger finger blistered, popped, and blistered again.

I going to see Lübeck, and I was going to bring back

whatever I could carry. It took hours of staring at the

ceiling before I fell asleep.

I woke to unbearable pain. I tried pushing myself

out of bed, but my right arm collapsed under me. I

15

Page 20

EUROPA UNIVERSALIS IV: ANTHOLOGY OF ALTERNATE HISTORY

dragged my right hand onto my chest to look. It was a

bulging, purple mess of swelled meat and jumbled

bones. A brief glimpse of my mother standing at the

door with a hammer was all I needed to understand

what had happened.

I screamed every foul word I knew until I ran out

of words and then I screamed incoherent gibberish and

then my tongue gave up and I just screamed. By the

time I’d worked up the strength to stand, Mother was

long gone. I raced into town without even pausing to

tend to my hand. I don’t know what I intended to do.

Would I have reported my mother? I’m not sure. But

by the time I got to Grevesmühlen the Rifles had already left for Lübeck. It didn’t matter. I’d never be able

to fire a rifle, let alone be one.

Mother had never spoken ill of the companies, or

argued when I talked about joining them. She was loyal

to the Rifles and they were loyal to her. But I thought

I understood. I thought my mother didn’t want me to

grow up, that she was scared to let her son risk his life,

that she wanted me to be a coward so I could be her

boy forever. We didn’t talk about it properly until years

later, when she joined me in Philadelphia. It wasn’t that

she was scared of me dying. She was scared of me dying

for a company. Quietly but fervently, she hated them

with every fiber of her being.

7. The Radio

Two days after the Rifles set out for Lübeck, a small

group of recruits rode back into town, and with them

was every horse the Rifles had brought. I was with the

crowd waiting for our company to return. Word rushed

through the crowd that these were the only survivors,

16

Page 21

COMPANY – LUKE BEAN

then in the very next breath, the story changed. The

men were on their way, they just didn’t need to ride

their horses home.

The Duke’s Rifles drove into town four hours later,

and every last one of them at the wheel of a Bernardi

Autocycle. Most of them kept on driving to Schwerin,

but our local Rifles were heroes like never before. Everyone wanted to drive an autocycle, or ride in one, or

at least just honk the horn. By the time people started

creeping home to sleep, three cycles were stuck in

ditches, one had crashed through the wall of a house,

and nearly half of them were out of fuel. Throughout

the night and into the next morning, Rifles trickled in

on foot from the road to Schwerin, having also crashed

their cycles or run out of gas. The men had brought

back several barrels of petrol, but it quickly became

clear that it wasn’t enough to keep the cycles fuelled

for long, and within a year or so the last of them had

run dry. They remained chained up outside houses as

rusting monuments, testifying that the men who lived

here’d had their way with the Queen of the Hansa.

Erich got Mother her radio. He pulled up at our

house the morning after the Rifles returned with this

huge cabinet radio taking up the driver’s seat and him

leaning out the side, barely keeping control of the autocycle. Just a week before I’d have laughed my head

off. Mother still hadn’t come home after breaking my

hand, and I wasn’t able to help him carry it, so he had

to nudge the radio into our house inch by inch. Erich

was disappointed that Mother wasn’t home to greet

him, and probably a little worried. He said what a

shame it was about my hand, but he didn’t ask for an

explanation, and we never really talked about the Rifles

anymore after that.

17

Page 22

EUROPA UNIVERSALIS IV: ANTHOLOGY OF ALTERNATE HISTORY

My mother came home the next day. We didn’t talk,

but she found the radio, and she read the note Erich

had left, and they seemed to cheer her up a little. With

my broken hand, I couldn’t train to join the Rifles anymore, and it was weeks before I could work the poppy

fields. The radio became the new center of my life. At

first, every broadcast was about Lübeck. It amused me

to hear Rostock and Hamburg lamenting our victory.

When the Swedes tried and failed to relieve Lübeck

from the companies that had stayed to pick it clean, the

radio wept and I cheered. At night I stayed quiet to see

if I could hear gunfire, but it was too far away.

After a few days some of the pleasure went out of

the constant coverage of Lübeck. Grevesmühlen was

raided only rarely, and not as harshly as a town without

company protection would have been, but even so

Lübeck’s plight was not impossible for me to relate to.

Sometimes they would broadcast lists of survivors who

had been separated from their loved ones, and I turned

off the radio for that. But eventually the mournful tributes to Lübeck waned, and my love affair with radio

began in earnest.

I became a hermit and a man of the world at the

same time. I listened to American jazz and English

marches and Hansa cabaret and strange atonal Russian

music and just about anything else they’d put on the

air. Mother took up some of the slack in the poppy

fields, partly in penance for my hand and partly on a

condition: I was to learn English. The Hanseatic Cities

had a significant population of refugees who had fled

England when the Leveller Party took power, enough

to have English-language radio stations. They played

detective stories and Westerns brought over from the

18

Page 23

COMPANY – LUKE BEAN

US, and even before I understood what they were saying I understood the sound of a gruff man and a sultry

woman and a gunshot. This was my life for two years:

hunched over a radio, listening to a world I’d never

known.

As young love often does, my relationship with the

radio came to an end. The radio was hidden in a storage

cellar. It was a treasured item, and it was better not to

attract attention to it. This worked for a time, but Erich

could not be kept from boasting about how he’d

brought his woman a radio. Eventually, the Rifles were

contracted to go off and fight in some foreign war (I’d

stopped keeping track) and Grevesmühlen was raided.

The Stranger’s Band was led by a man named Heinrich Robledo. He was not born to the life of a company

man. He had chosen it. He was from the United Kingdoms—his real name was Enrique—and had fought

with the Spanish separatists for a long time. They got

tired of fighting before he did, so he came to Germany

so he could keep fighting forever. The captain of the

Rifles had offended him somehow, and we suffered the

consequences.

Robledo came to our door himself with a small

group of men. He’d heard we had a radio. My mother

had made sure to be far away by the time the Stranger’s

Band arrived, but I had remained behind to help them

find anything they needed. It was best not to let raiders

look for things on their own, because if they couldn’t

find them they got frustrated, and that could put them

in a destructive mood.

I led Robledo to the cellar. He took one look at the

radio and spat. “It’s too big. Why’s it so big?” he said,

as if I’d somehow enlarged it to spite him. I said I didn’t

know. His men tied a rope around it and hauled it out

19

Page 24

EUROPA UNIVERSALIS IV: ANTHOLOGY OF ALTERNATE HISTORY

of the cellar. It banged against the wall as it rose,

knocking off a chip of its sleek casing with each strike.

And then Robledo didn’t know what to do with it.

He’d imagined a newer, smaller model of radio. His

wagons were with the main force, looting Schwerin.

His men could lift it, but couldn’t carry it far. They tried

tying it to a horse and the horse collapsed. They

dragged the radio out in front of our house. Robledo

smashed it to pieces with his rifle butt so that if he

couldn’t have it, at least we couldn’t either. By the time

the Quartered Men arrived to reinforce Grevesmühlen,

Heinrich Robledo was long gone.

8. Duckie

The wreckage of the radio was still outside my house

when Duckie Wooler arrived in Grevesmühlen. It had

been there for nearly a month, but neither Mother nor

myself had the heart to get rid of it. He was taking a

photograph of the broken radio, and I accidentally

stepped into the back of the shot. He made an “out of

the way” gesture, and I told him to fuck off, and he

said “What?” in English, and I told him to fuck off in

English, and he offered to hire me as a translator, and

I told him to fuck off again, and off he fucked.

Duckie lingered in town, and quickly became a local

laughingstock. He had not yet grown fat, but already

he gave the impression of one destined for fatness.

People tolerated his pictures at first, then let him take

pictures if he paid them in cigarettes. He was sometimes flanked by two blank-faced men that everyone

assumed, probably correctly, were Hansa agents. It was

thanks to these men, whose names I’ve forgotten, that

I came to work for Duckie. I happened to be in the

20

Page 25

COMPANY – LUKE BEAN

Hart’s Head on an errand, and I overheard him introducing them as the Duck’s Rifles. The pun didn’t work

in German, but I couldn’t help but bark a quick laugh.

He noticed.

As I left the tavern, I found Duckie matching my

stride. He explained his situation to me. Grevesmühlen

had sucked Duckie in like mud. He had spent all his

money bribing his way past the Hanseatic border, and

now he had an escort but no translator and no way of

getting around. He said he needed someone to provide

a local touch. But more than that, I think he needed

someone to care. He thought his photographs could

set us free from the companies. He was starting to realize that we were our own prisoners. He needed just

one person to ask to be free.

Duckie walked me all the way home. He gave

speeches about liberty, and when those made my eyes

glaze over he told horror stories he’d heard about the

companies, and when that didn’t move me he gave me

a box of cigarettes and promised me two whole cartons. Something about him reminded me of the Wehrwolf. Not just the things he said, but the way he talked,

even the way he carried himself. Maybe that’s why I

told him I’d think about it, as a way of apologizing. I

don’t know. He didn’t want to let me go before I’d

agreed to help him, but I insisted I was going to sleep.

He scrunched up his face like a wounded dog and said

“Don’t you want to do something about all this?”

I manipulated the question in my head as I lay in

bed. “Don’t you want to do something about all this?”

It shocked me that I’d never considered the question.

I dreamt of the men hanging from the balloon, and

throwing rocks at the walls of Lübeck, and laughing at

Erich’s jokes so hard I cried, and that man laughing as

21

Page 26

EUROPA UNIVERSALIS IV: ANTHOLOGY OF ALTERNATE HISTORY

they peeled his skin off, and the joy that ran through

the town after a successful raid, and my beloved radio,

and the look on the Wehrwolf’s face as they dragged

him away, and in the morning, I knew my answer.

***

IN ACTUAL HISTORY

Albrecht von Wallenstein was the commander of the

Habsburg armies in the Thirty Years’ War. His forces

were largely made up of mercenaries, who were supported by looting the countryside. Though a highly capable general, Wallenstein was erratic, ambitious, and

untrustworthy, traits that eventually lead to his assassination on the orders of his own Emperor. Company

imagines a world in which the 1634 attempt on Wallenstein’s life fails, and his conspirators depose Emperor Ferdinand II.

The Thirty Years’ War—known to the characters of

Company as the Sixty Years’ War—was devastating to

Germany in real life, but the Holy Roman Empire survived as a patchwork of states rather than devolving

into a no-man’s-land ruled by mercenary companies.

The Holy Roman Empire helped defeat France in the

War of Spanish Succession and Spain in the War of the

Quadruple Alliance, averting the Franco-Spanish union known in Company as the United Kingdoms. In real

life, of course, the United Kingdom refers to the union

of the English and Scottish thrones, which here has

been divided by a powerful France’s support of the Jacobite Rebellions.

The 1910 book Der Wehrwolf, about peasants defending their town from raiders in the Thirty Years’

22

Page 27

COMPANY – LUKE BEAN

War, inspired a very different guerrilla organization in

real life: the Nazis’ Wehrwolf commando force. And

Gottlieb Daimler, inventor of the Daimler Automated

Rifle, abandoned gunsmithing at 18 to focus on mechanical engineering. Instead of the first assault rifles,

he would go on to create the first modern cars. Cars

are replaced in Company by the more rudimentary auto-

cycle, a motorized tricycle descended from the designs

of Enrico Bernardi.

ABOUT LUKE BEAN

Luke Bean is an aspiring screenwriter and a recent

graduate from New York University’s Tisch School of

the Arts, where he majored in Film & Television and

History. He currently works at the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Luke Bean is one of the

three winners of the Paradox Short Story Contest 2014.

23

Page 28

EUROPA UNIVERSALIS IV: ANTHOLOGY OF ALTERNATE HISTORY

THE MORE IT CHANGES

By Harry Turtledove

Yitzkhak the cobbler loosened the vise and checked to

see whether the glue had set between the half-dozen

thicknesses of leather. Finding it had, he let out a small

grunt of satisfaction. On the topmost layer, he drew an

outline of the rears on the pair of boots that needed reheeling. The knife he reached for was sharp but sturdy.

Sturdy it had to be, to cut through that much leather.

He bore down with the knife, using all the strength

in his right arm. If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right

hand forget her cunning. The verse from Psalm CXXXVII

was seldom far from the Jew’s thoughts.

He muttered to himself as he cut. Too many people

had forgotten too many things over the course of too

many years. To Yitzkhak, it seemed as though more

people had forgotten more things lately. That might

have been because his rusty beard had more white in it

than he cared to remember. Or, on the other hand, it

might not. The way things were these days, you never

could tell. And no one ever seemed to forget trouble.

24

Page 29

THE MORE IT CHANGES – HARRY TURTLEDOVE

After cutting the new boot heels, he used brass nails

to fix them in place. Iron nails would have been

cheaper, and would have served just as well…till

Chaim the butcher walked in mud or splashed through

a puddle. After that, they would have started to rust.

Do it right the first time was one of the rules Yitzkhak’s

father had beaten into him. The habit was too deeply

ingrained now for him to lose it, or even to remember

he’d once had to acquire it.

Warm, sweet summer air and light came through

the open door and the narrow window of the cobbler’s

shop. So did the exciting, almost intoxicating gabble of

trade. Monday was market day in Kolomija—the

town’s name could be spelled at least half a dozen different ways in at least three different alphabets. The

same was true for Yitzkhak’s own name. This was a

debatable part of the world in all kinds of ways.

It was summer, yes. Just what the date was was as

debatable as the spelling of Kolomija. By the calendar

the Catholics used, it was August 24, 1772. To the Orthodox, it was August 13 of the same year. In the Jews’

system, which reckoned from the creation of the

world, it was the twenty-fifth of Av in the year 5532.

The Ottoman Empire lay not far to the south—just on

the other side of the Carpathians. To Muslims, it was

the twenty-fourth of Jumaada al-awal, 1186. And, by

the new reckoning that threatened to swallow all the

others, it was the twenty-fifth day of the eleventh

month in the year 95.

Even the frontiers in these parts rippled and shifted

like a river. Until a few months before, the Jews of Kolomija had paid taxes to a nobleman who mostly didn’t

send them to the King of Poland. Now, though, Kolomija—and that nobleman—owed allegiance to the

25

Page 30

EUROPA UNIVERSALIS IV: ANTHOLOGY OF ALTERNATE HISTORY

Emperor of Austria. If the nobleman held out on Joseph, Yitzkhak suspected he would regret it.

The cobbler looked at the boots he’d just fixed. He

looked under the counter. He had to patch a torn upper for Shmuel the rope-maker. That could keep,

though. Shmuel was down in Jablonow, fifteen miles

to the south, tending his sick mother. Unless the poor

woman took a turn for the worse and died (God forbid,

Yitzkhak thought), he wouldn’t come home for a week

or two.

Yitzkhak didn’t have anything he needed to do right

this minute. It was gloomy and stuffy inside the

cramped shop. It smelled of leather and sweat and glue.

Under that, it smelled musty.

Outside, the sun shone. Outside, the market square

would be packed. Kolomija had a fine market day. It

wouldn’t just be peasants bringing in chickens and

white radishes and peas from the countryside. Merchants came call the way from Czernowitz, sometimes

all the way from Rowne, to buy and sell and trade.

Rowne was on the other side of the border now, but

nobody yet had fussed about it.

He closed and latched the shutter, stepped outside,

and put a big iron padlock on the front door. The lock

was ancient and rusty. A half-witted child could pick it

or force it. So far, no burglar had figured that out. With

luck, none would till Yitzkhak got back. “Alevai oma-

nyn,” he murmured as he started for the market square.

His own well-made boots kicked up dust at every

step. It was hot outside. The broad brim of his foxtrimmed black hat kept the sun off his face, but sweat

sprang out on his forehead.

He wasn’t the only man who might have been working but was heading for the market instead. He called

26

Page 31

THE MORE IT CHANGES – HARRY TURTLEDOVE

greetings to Jews and to Catholic Poles. Like most people in Kolomija, he could get along in Yiddish or

Polish, German or Little Russian, or even Slovak in a

pinch. He talked to his God in Hebrew, as the Poles

talked to theirs in Latin.

Czeslaw the tavern-keeper had a bottle of plum

brandy under each arm. He was on his way back from

the square. His red nose and the veins that tracked his

cheeks said he drank up some of his profits. He and

Yitzkhak nodded to each other. Kolomija wasn’t such

a big town that everyone didn’t know everyone else, at

least by sight.

“How’s the square?” Yitzkhak asked.

“Busy. Busiest I’ve seen it for a while. With the roads

dry, people from a long way off can get here.” Czeslaw

frowned. His ice-gray eyes narrowed. “I’m not so sure

that’s a good thing, not the way it is nowadays. They’ll

go home and remind their neighbors we’re around.”

Yitzkhak made an unhappy noise. “I’m not so sure

it’s good, either. Sometimes—a lot of the time—the

most you can hope for is that everybody forgets about

you and leaves you alone.”

“Too right, it is!” Czeslaw said. “There was talk that

haidamacks are gathering.” He crossed himself to turn

aside the evil omen.

“God forbid!” Instead of thinking it, Yitzkhak said

it aloud. He wanted to give the Lord a better chance of

hearing it. Haidamacks meant rioters. They were Cossacks and other ne’er-do-wells who swarmed like locusts every so often, killing and looting and burning for

the greater glory of their notion of God—and for the

fun of it. Yitzkhak went on, “I hope the talk is wrong.

The last time they came through was only—what?—

four years ago?”

27

Page 32

EUROPA UNIVERSALIS IV: ANTHOLOGY OF ALTERNATE HISTORY

“Yes, that’s when it was,” the taverner said. “Before

that, we didn’t see them for fifteen or twenty years, and

then another fifteen before that. We were both little

boys back then.”

“I remember.” Yitzkhak touched the brim of his hat

once more. “Well, I’d better head on to the square my-

self and hear it with my own ears. May the Lord bless

you and keep you, Czeslaw.”

“And you, Jew. And you.” Bobbing his head, the

Pole headed up the street toward his place of business.

On to the market square trudged Yitzkhak. The joy,

the anticipation, were gone from his step. The only

thing he had to look forward to now was bad news.

The day felt darker, as if clouds covered the sun. They

didn’t, but the cobbler saw with his heart as much as

with his ears.

Wagons and carts filled the square. Women in embroidered head scarves sat on the ground, selling eggs

or mushrooms or turnips from baskets they’d made

themselves. A donkey brayed. Stray dogs skulked,

looking for food they could steal.

Peddlers who’d come to Kolomija from bigger

towns shouted their wares: plates; big, clunky clocks

with gilded wooden cases; books in German and

French and Latin and Hebrew; the brandy Czeslaw had

bought; carved meerschaums from Vienna; singing

finches in brass cages; and almost anything else someone thought he might be able to sell.

Yitzkhak eyed the meerschaums with longing, especially one in the shape of a bare-breasted mermaid—

you smoked through her tail. His current pipe was

baked clay. It worked, but it was ugly as the mud it

came from. He asked the trader what a meerschaum

cost. The answer made him retreat in a hurry. The best

28

Page 33

THE MORE IT CHANGES – HARRY TURTLEDOVE

haggling in the world wouldn’t bring the price down to

anything he could afford.

He did buy a bagel for a copper. His jaw worked at

the chewy dough as he went through the square,

though not before he recited the brukha over bread. A

sausage-seller held up a link. Yitzkhak politely shook

his head. Tadeusz used pork in his sausages; it wasn’t

forbidden him.

The cobbler wished he had ears like a cat’s or a

fox’s, ears that could swivel and track things he particularly wanted to hear. But he turned out not to need

anything like that. People were talking about haidamacks

in several different languages. They would have talked

about a rising storm the same way when clouds were

still low on the horizon.

He wasn’t the only man from Kolomija whose face

got glummer the longer he stayed in the market square.

Alter the druggist and Casimir the stonecutter were

talking when Yitzkhak came up to them. Alter touched

his hatbrim; Casimir bobbed a token bow.

“It doesn’t sound good,” the stonecutter said.

“They’re coming, sure as sure,” the druggist agreed

sadly. “For our sins, they’re coming.”

“We must have done something awful, to make

God hate us so much,” Yitzkhak said. “Another pogrom, so soon after the last one . . .”

As Czeslaw had before, Casimir made the sign of

the cross. “I’m a good Catholic—well, as good a Catholic as an ordinary man can be,” he said. “All I want to

do is to worship God the way my father and my grand-

fathers and all my ancestors did before me.”

“That’s all I want, too.” Yitzkhak and Alter said the

same thing at the same time. The two Jews looked at

each other and laughed. It was that or burst into tears.

29

Page 34

EUROPA UNIVERSALIS IV: ANTHOLOGY OF ALTERNATE HISTORY

Casimir glowered at them from under bushy eyebrows. “That miserable . . .” The stonecutter growled

a Polish obscenity, adding, “He was just a rotten Zhyd

himself.”

“Nu?” Yitzkhak shrugged an expressive—and nerv-

ous—shrug. He didn’t want to tangle with Casimir; the

man’s trade had given him shoulders broad as a bull’s

and upper arms bulging with muscle. He tried simple

truth instead: “So was the one you go to church for.”

“It’s not the same,” Casimir said, but he stopped

glowering.

“Besides,” Yitzkhak added, “would it make any difference if he’d been a Turk? He still would have

been…what he was. What they say he was, I mean.”

“What they say he was, eh?” Casimir seemed to like

that. He nodded. “Maybe the God-cursed haidamacks

will be afraid of the Austrian Emperor. This is his land

now. Maybe they won’t come. Maybe the town can

fight them off if they do.” He lumbered away. He’d

talked himself into feeling better, anyhow.

Softly, so the stonecutter wouldn’t hear, Alter said,

“And maybe I’ll grown like an onion, with my head in

the ground.”

“Maybe you will,” Yitzkhak said. “You never can

tell.” They both laughed again. Again, Yitzkhak heard

the sorrow under the mirth.

***

Summer slipped toward fall. The High Holy Days

came and went. The Jewish year 5532 gave way to

5533. Yitzkhak fasted and prayed through Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. He begged forgiveness of

everyone he’d offended the past year, and did his best

30

Page 35

THE MORE IT CHANGES – HARRY TURTLEDOVE

to forgive everyone who apologized to him. It wasn’t

always easy, but on that day of days a man had to try.

The fall rains held off long enough to let the peasants bring in a good harvest of barley and wheat. The

winter would be hungry—winters usually were. But no

one seemed likely to starve.

As soon as the rains came, roads went from dusty

tracks to rivers of mud. Travel slowed, or else stopped

altogether. The roof in Yitzkhak’s shop leaked. He put

a chipped bowl under one drip and a dented tin cup

that had lost its handle under another. Every so often,

he would toss the water into the muddy street.

He didn’t mind one bit, not that autumn (during

which the new reckoning passed from year 95 to 96).

Every time a drop plinked into the tin cup, he would

smile. Forty days and forty nights, Lord, he thought. The

longer it rained, the longer before the haidamacks could

come, if the haidamacks did come. They swept out of

the east when they came, and the rains were usually

worse in that direction. Everybody said so.

But the rainy season didn’t last forever, no matter

how much Yitzkhak wished it would. Snow whitened

the upper slopes of the Carpathians. Frost traced magic

patterns on the glass windowpanes of rich men’s

houses. Yes, the rich—mostly Poles—in Kolomija had

glass windows, as if it were Czernowitz or Kiev or Warsaw.

And the cold weather hardened the ground, as it did

toward the end of fall every year. The muddy roads

turned to something more like rock. With the crops in,

the worst of the year’s work was done. Some men out

in the countryside lay up through the winter like sleepy

bears—though bears didn’t have vodka to help make

time spin by.

31

Page 36

EUROPA UNIVERSALIS IV: ANTHOLOGY OF ALTERNATE HISTORY

Yitzkhak didn’t mind the men who stayed in their

houses and drank their way through winter. They were

harmless. Oh, they might beat their wives and children,

but they might do that sober, too. The trouble was,

vodka also inflamed other men, the kind who loaded

their muskets and pistols, climbed into the saddle, and

went riding in the name of the Messiah—and in the

name of kicking up as much trouble as they could.

Haidamacks torched the synagogue in Zastawna.

They burned the rabbi in it, and howled with laughter

at his screams. Zastawna lay between Czernowitz and

Kolomija, west of the one but east of the other. It

wasn’t nearly far enough away to let anyone in Kolomija feel safe, in other words.

Snyatyn was a smaller town a little southwest of

Zastawna—even closer to Kolomija, that is. Two days

after people fleeing Zastawna came to Kolomija, people fleeing Snyatyn got there.

“God have mercy on us!” a Catholic woman from

Snyatyn screamed in the street as she stumbled past

Yitzkhak’s house. “Christ have mercy on us! They mur-

dered the priest, the holy father! They cut his throat on

the altar in the church, as if he were a hog! Their horses

drank from the holy-water fount! Oh, Christ have

mercy!”

Yitzkhak’s wife was a small, dark woman named

Rivka. She was quiet and steady. He could see that

those shrieks shook her even so. “They’ll be here next,

won’t they?” she said, her voice not much above a

whisper.

“I’m afraid so,” he answered.

“They went away the last time,” his son Aaron said.

“They went away, and we’re still here, and we’re still

32

Page 37

THE MORE IT CHANGES – HARRY TURTLEDOVE

Jews.” He was fifteen. He thought he was a man. Under religious law, he was. Otherwise . . . less so. He did

have a certain gift for the Talmud, which made Yitzkhak proud. An open volume sat on the table in front

of him.

“It’s like a bad storm,” Yitzkhak said heavily. “It

blows for a while. Then it eases back, and you think

maybe it’s over. But it blows some more, stronger than

ever. And before this one is done, if it ever is, it’s liable

to blow all our houses down.”

“What will you do, then, Father?” Aaron asked.

“Will you bend to the storm?”

Yitzkhak understood what that meant. He shook

his head. “A lot of people have, but I won’t. I’ll stay a

Jew, a proper Jew, as long as I live. Hear, O Israel, the

Lord our God, the Lord is one. That was the first prayer I

learned, and those will be the last words that ever pass

my lips.”

“Some of the Catholics want to fight the haidam-

acks,” Aaron said, his voice cracking with excitement.

Talmud or no Talmud, he added, “I want to fight

alongside them.”

“What do they say about that?” the cobbler asked.

His wife looked horrified. He understood; that was

what mothers were for. He knew horror, too, but also

a grim determination.

“They say every man with a knife or a hatchet in his

hands can help,” Aaron answered. “If we don’t fight,

we’ll go under.”

No Jew in Kolomija owned anything much more

dangerous than a knife or a hatchet. The Catholics had

firearms. Some had gone to war; others hunted. That

they were willing, even happy, to have Jews stand with

them was a telling measure of how desperate they were.

33

Page 38

EUROPA UNIVERSALIS IV: ANTHOLOGY OF ALTERNATE HISTORY

Well, by the woman from Snyatyn’s cries, they had reason to be desperate. Time was when they’d looked

down their noses at Jews. They still did, some; goyim

were like that. But the passage of Kolomija from Poland to Austria was the least of their worries.

Poland, Austria, Russia, Turkey—even, from what

Yitzkhak had heard, Prussia . . . The same storm was

blowing through all of them, and showed no sign of

blowing itself out. If anything, it was spreading. Where

it touched, nothing was the same again. Would the

proud Catholic Poles of Kolomija want Jews at their

side if things were the same as they used to be?

Tell him no. Tell him he’s too young—Rivka’s eyes

begged Yitzkhak. But the cobbler could see that the

only way to keep Aaron from doing something like that

would be to tie him up and sit on him. Easier to ride a

horse in the direction it was already going.

Besides… “Enough is enough. If nobody stands up

to the haidamacks, they’ll ride roughshod over everything,” Yitzkhak said. “And if the Catholics will take

one Jew who doesn’t know much about this fighting

business, chances are they’ll take two.”

“Vey iz mir!” Rivka said. Yitzkhak could hardly hear

her through his son’s war whoop. He didn’t feel like a

warrior himself. Unlike Aaron, he didn’t want to fight.

But he didn’t think things would turn out any worse

for him if he did than if he didn’t. There was even some

small chance they might turn out better.

He got something better than a hatchet. The Catholics gave him a spear. A spear of sorts, anyhow: an old

scythe blade lashed to a staff. He had Rivka’s longest

knife on his belt, and a small one from his shop stuck

in one boot for a holdout weapon. Aaron hefted a

makeshift spear, too.

34

Page 39

THE MORE IT CHANGES – HARRY TURTLEDOVE

Casimir carried a stout wooden club with nails

driven through it. Yitzkhak wouldn’t have wanted to

be on the wrong end of a buffet from that, especially

not with the stonecutter swinging it. But the haidamacks

were horsemen. A spear at least gave you extra reach.

How much good could a club do?

A couple of Poles had iron helmets. One even wore

a back-and-breast that must have come down from his

great-grandfather. It might keep out a musket ball. It

would surely make the man very slow. Several Catholics shouldered muskets. One was a businesslike modern flintlock. The rest looked at least as old as the

corselet: wheel-locks and an ancient matchlock.

Czeslaw had a pistol. A taverner needed something

to keep himself safe. He surveyed the ragtag militia.

“We’re a fine bunch, aren’t we?” he said. “Maybe the

haidamacks will get a good look at us and laugh themselves to death. Christ, it’s our best hope!”

“If you feel that way—” Yitzkhak began.

“Why don’t I pack it in?” Czeslaw finished for him.

“Because I’m a stubborn son of a bitch, that’s why. We

all are, or we wouldn’t fight back. We’d do what the

haidamacks want, and that would be that. Only then

we’d hate our own reflections for the rest of our lives.”

Yitzkhak nodded. He felt the same way. He

wouldn’t have stood there shivering in the cold if he

hadn’t. So many, though, had gone over to the new

reckoning without so much as a backward glance at

what they’d once believed.

One of the Poles who’d done some real soldiering

before his hair grayed took command of the fighters.

He stationed them on the streets just inside the east

end of town. “We’ll make things crowded for the

35

Page 40

EUROPA UNIVERSALIS IV: ANTHOLOGY OF ALTERNATE HISTORY

haidamacks, anyway,” he said. “We’ll run up what barricades we can and hope for the best.”

“What if they swing around to the west side?” Aa-

ron asked him.

The veteran scowled. “You’re one of those damn

smart Jews, are you? If they go over there, they screw

us up the ass, that’s what. But they won’t. They aren’t

long on tactics, the haidamacks. They just charge on in

and start smashing things.”

Townswomen brought the fighters soup and stew in

big, steaming kettles. After a hurried brukha, Yitzkhak ate

whatever got ladled into his bowl without worrying much

about breaking dietary laws. He’d atone for his sins later,

if he had a later. When you went to war, you dispensed

with a lot of the formalities anyhow.

As night fell, Casimir pointed out into the gathering

gloom. “Look! You can see their fires!”

Yitzkhak cocked his head to one side. “Yes, and you

can hear them howling, too. If they aren’t already plastered, they will be soon.”

A drum began to pound out there. The first thud

was so deep and sudden, for a panicky moment Yitzkhak took it for a cannon firing. But it thumped again

and again and again. The haidamacks’ drunken shouts

coalesced into a chorus that rang out between the

drumbeats: “Sabbatai! Sabbatai!”

“God damn Sabbatai,” Casimir said in Polish at

Yitzkhak’s left hand. He spat on the ground.

“God curse Sabbatai,” Aaron said in Yiddish at

Yitzkhak’s right hand. He spat on the ground,

too.

“God’s already done whatever He chose to do with

Sabbatai Tzevi,” Yitzkhak said, first in the one lan-

guage and then in the other, though Aaron followed

36

Page 41

THE MORE IT CHANGES – HARRY TURTLEDOVE

Polish perfectly well. “It’s here on earth that we’re still

sorting things out.”

“God damn Sabbatai,” Casimir repeated. “God

damn him and the Devil broil him black!”

Sabbatai Tzevi had been dead for almost a century;

the date of his death marked the first day of the new

reckoning his followers used. He’d been born an ordinary Jew in Turkey, but he had messianic ambitions

and pretensions. He also had the kind of spellbinding

character that made people who heard him take those

ambitions and pretensions seriously.

They said he worked miracles. Yitzkhak didn’t

know the details; he didn’t want to know the details.

Sabbatai had preached in Asia Minor, and in the Holy

Land, and in Egypt. Some from Europe who’d heard

him believed his claims as firmly as the folk in the Ottoman Empire.

Finally, in the year the Christians called 1666, Sultan

Mehmet IV summoned Sabbatai to Istanbul to hear at

first-hand what he had to say. The canny Turk listened

to the man who called himself the Messiah . . . and declared that he was changing his name to Sabbatai I.

The new faith exploded through the vast Ottoman

domain, and out into Europe as well. Sabbatai Tzevi

lived another ten years after converting Mehmet to his

cause. Mullahs, cardinals, patriarchs, rabbis—every religious authority called curses down on his head. It did

them little good. When people were ready for something, they grabbed at it whether their leaders approved

or not. Christianity and Islam had spread the same way.

And when people were ready for something, they

were also ready—eager!—to ram it down their neighbors’ throats, regardless of whether the neighbors were

ready, too.

37

Page 42

EUROPA UNIVERSALIS IV: ANTHOLOGY OF ALTERNATE HISTORY

“Sabbatai!” the haidamacks roared. “Sabbatai!” They

danced around the fires like…like Yitzkhak didn’t

know what. He vaguely knew there was a New world

beyond the ocean far to the west (he only vaguely knew

there was an ocean far to the west), but tales of its natives had never reached his ears.

He turned to the grizzled veteran who ordered the

defenders around. “We ought to go out there while

they’re drinking and yelling and carrying on—take

them by surprise.”

“Another Jew who thinks he’s a general.” The Pole

sounded more amused than annoyed. He waved toward the fires. “Go ahead, Jew—be my guest. If you

guys were real soldiers, not odds-and-sods, I might try

it. But they’d chop you to bits if I did. You don’t know

how to hold together. No, our best chance is staying

where we’re at and making them come to us.”

“All right.” Yitzkhak had no idea whether it was or not.

But the gray-haired Pole understood more of war than he

did. He pulled his black coat tighter around him, lay down

on the ground behind a barrel, and tried to sleep.

He didn’t think he would, but he managed a light,

on-and-off doze. He was dozing when a haidamack rode

out of the gray predawn light in the east and shouted,

“You misbelievers there! Give your souls to Sabbatai

Tzevi, God’s great light on earth, and we’ll leave you

alone! Otherwise, you’ll pay for your wickedness in this

world and the next!” He sounded like a Little Russian

trying to speak Polish, but no one in Kolomija would

have trouble following him.

“Go away! Leave us alone! Let us worship the way

we want to!” Yitzkhak shouted as he grabbed his spear

and scrambled to his feet. Other men yelled variations

on the same theme.

38

Page 43

THE MORE IT CHANGES – HARRY TURTLEDOVE

“On your heads be it—and it will.” The haidamack

turned his horse and rode back to his encampment.

Sabbatai’s followers, like those of Muhammad and Jesus before them, were sure they knew the one right answer and had the right, even the duty, to inflict it on

everyone else. Jews didn’t proselytize—which was, no

doubt, why there were so few of them.

The drums began to pound again. When the sun

rose, the haidamacks came trotting toward the town and

its homemade barriers. Some bore lances, some short

muskets, some pistols. They wore fur hats; their capes

streamed out behind them. As they came, they shouted

Sabbatai’s name.

One of the defenders steadied his musket on a

board and fired. The shot missed anyhow. Yitzkhak

was too excited to be afraid—till a pistol ball smashed

Casimir’s face. The burly stonecutter wailed and gobbled at the same time. Bright blood poured out between his fingers as he clapped his hands to the wound.

Then he fell, and it puddled and steamed under him.

He never got to use his fearsome club.

A raider’s horse went down. The haidamack howled—his

leg was broken or crushed beneath the thrashing animal.

The others kept pushing forward, though. They had more

guns and less fear than Kolomija’s amateur defenders.

Yitzkhak awkwardly thrust his improvised spear at a

horse. The rider didn’t get close enough to let the weapon

bite. He shot at Yitzkhak, missed, and cursed horribly.

Another haidamack skewered a Jew with his lance at

the same time as his comrade shot the Catholic next to

that Jew. Their horses chested planks aside. Whooping,

the haidamacks poured through the breach in the miserable barricade and into Kolomija. A couple of them

went down, but most rode on.

39

Page 44

EUROPA UNIVERSALIS IV: ANTHOLOGY OF ALTERNATE HISTORY

Some made for the Catholic church, others for the

synagogue. That split the defenders: the Poles tried to

save the one, the Jews the other. The fire in the synagogue started first.

Aaron lay in the street, bleeding from the head.

“No!” Yitzkhak shouted. He tried to skewer on of the

raiders. Laughing, the man yanked the spear from his

startled hands. “No!” he shouted again. “Your Sabba-

tai, he was a Jew, the same as we are!”

“He got over it.” The haidamack aimed a musket at

Yitzkhak’s belly. “Will you, fool? Admit that Sabbatai

was the Lord’s chosen, the Messiah, and you can have

your worthless life.”

Yitzkhak grabbed for the kitchen knife on his belt.

“It isn’t true,” he said. Even as the words came out of

his mouth, he wished he had them back. Why would

you condemn yourself like that? Because I am a Jew, he

thought. Because I can’t be anything else.

Laughing still, the raider pulled the trigger. Maybe

the gun would misfire. If it didn’t, maybe he would

miss. Maybe—

Flame and smoke burst from the muzzle. The bullet

caught Yitzkhak square in the chest. It didn’t hurt.

Then it did, horribly. He crumpled, blood filling his

mouth. Through it, he managed to choke out, “Hear,

O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is one” before

darkness swallowed him.

The synagogue burned. A couple of hundred yards

away, so did the church. “Sabbatai!” the haidamacks

cried, over and over again. “Sabbatai!” Like the smoke

from the houses of God, the name mounted to the uncaring heavens.

***

40

Page 45

THE MORE IT CHANGES – HARRY TURTLEDOVE

IN ACTUAL HISTORY

The real career of Sabbatai Tzevi (1626–1676) is the

same as that described in the story up to the point

where he met Mehmet IV. The Jewish mystic began to

preach that he was the Messiah in 1648, and was aided

by a man in Istanbul who said that he had heard a proclaiming that Sabbatai was truly the Redeemer. He was

a man of rare personal magnetism. He always fascinated children, and the way he sang the Psalms helped

draw men to him. He travelled to Jersualem and to

Cairo, where he married a beautiful young girl. From

the Middle East, the belief in Sabbatai’s Messianic nature spread to the leading trading cities of Western Europe through merchants, many of them Jews. Most of

the turmoil he created, though, was centered in the Ottoman Empire, where he lived. In early 1666, the Ottoman sultan, Mehmet IV, summoned him to Istanbul

for questioning. In September of that year, he was

brought before the sultan and, instead of being accepted as the Messiah as he was in the story, was offered the choice of conversion to Islam or death. He

converted. Naturally, that threw his movement into a

tailspin from which it never recovered. Sabbatai Tzevi

lived out the rest of his life in obscurity in Albania,

abandoned by most of those who had followed him. A

handful of believers refused to accept his apostasy, and

continued to think he truly was the Messiah. A tiny

remnant of them survives to this day.

41

Page 46

EUROPA UNIVERSALIS IV: ANTHOLOGY OF ALTERNATE HISTORY

ABOUT HARRY TURTLEDOVE

Harry Turtledove lives in Los Angeles, California. He

earned a doctorate in Byzantine history from the University of California, Los Angeles, and taught at UCLA,

Cal State Fullerton, and Cal State Los Angeles. At

about the same time, he began selling science fiction

and fantasy. Because of his training and interests, much

of what he has written is based on history. He worked

as a technical writer to support himself and his growing

family until 1991, when he began to write full-time. He

has won the Hugo, the Sidewise for alternate history

(twice), the John Esthen Cook award, and the Hal

Clement award for young-adult science fiction, and has

been a Nebula finalist. His books include the four novels of The Videssos Cycle (modeled after the history of

the Byzantine Empire), The Guns of the South (set in the

American Civil War), the Worldwar books (in which aliens invade in 1942), Ruled Britannia (set in a world

where the Spanish Armada succeeded and Shakespeare

is brought into an English uprising), and In the Presence

of Mine Enemies (in which the last Jews in Berlin struggle

to survive a lifetime after a German victory). He is married to fellow writer Laura Frankos. They have three

daughters, one granddaughter, and the inevitable writers’ cat.

42

Page 47

A SINGLE SHOT – ROD REES

A SINGLE SHOT

By Rod Rees

September 11, 1777: Brandywine Creek, near

Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania

“That’s a Frog ‘Ussar, that is, Captain,” whispered Ser-

geant Hopkins.

A cautious Captain Ferguson eased back a branch of

the bush he was cowering behind to give himself a better

sighting of the two horsemen who were taking such an

infernally close interest in the disposition of the British

Army. Hopkins was right: the flamboyant uniform of

the nearer of the two men was unmistakable. Only

French Hussars favoured so much gold braid.

“The other bloke’s a Yankee.”

Ferguson nodded. The blue and buff uniform and

tricorn hat were typical of those sported by Colonial

officers.

“Shall we let ‘em ‘ave it, Captain?’ Hopkins asked as

he brought his rifle up to his shoulder. ‘Easy pickings

at this distance.”

43

Page 48

EUROPA UNIVERSALIS IV: ANTHOLOGY OF ALTERNATE HISTORY

That was true. The horsemen were only fifty yards

from where Ferguson and his three men were hidden,

well within range of their rifles. And they were enemy

officers…

Something made Ferguson hesitate. In truth he was

sick of how brutish the war in the American Colonies

had become, disgusted by the atrocities he had seen

perpetrated by both sides. He judged himself to be a

gentleman, possessed of Christian sensibilities, and

Christian gentlemen did not sneak up on their enemies

and blast them in ambuscade. Anyway, there was a

family tradition of Fergusons—all staunchly Episcopalian—sympathising with rebels: his father had been a

resolute supporter of the Jacobite cause.

“Hold your fire,” Ferguson ordered and with that

he rose to his feet and hallooed the two horsemen.

“Gentlemen, I am Captain Patrick Ferguson, officer

commanding the Rifle Corps attached to the army of

Sir William Howe. I would most respectfully request

you to surrender yourselves—”

The Colonial didn’t even have the courtesy to

acknowledge Ferguson’s demand, instead he hauled

the head of his bay around and made to gallop away.

There was a crack of a rifle to Ferguson’s left. Hopkins

had fired.

“Damn your eyes! I said hold your fire,” snarled

Ferguson as he watched the American stiffen in his

saddle and then tumble from his horse to the ground.

“Beggin’ your pardon, Captain, but ‘e wos disobeying your order,” answered an unapologetic Hopkins.

“Got the bugger anyways, and like the General says,

the best sort ov Reb is a dead Reb, wot wiv them all

bin traitors to the King and such.”

Biting back a rebuke, Ferguson fired a warning shot

44

Page 49

A SINGLE SHOT – ROD REES

over the head of the hussar who had dismounted to

tend to his fallen comrade. The hussar, seeing the four

British riflemen advancing towards him, decided that

discretion was the better part of valour, climbed back

on his horse and rode away.

When they came up to the fallen man, Ferguson

could see that Hopkins’s shot had taken the Colonial

square in the back and now he lay, dead as mutton, in

a puddle of blood. In life he must have been an imposing individual, lean of build and topping six feet in

height; a man, if Ferguson wasn’t mistaken, more used

to giving orders than receiving them. Trying to disguise

his distaste of such an unnecessary death, Ferguson