Page 1

Environment

INFORMATION FROM KODAK

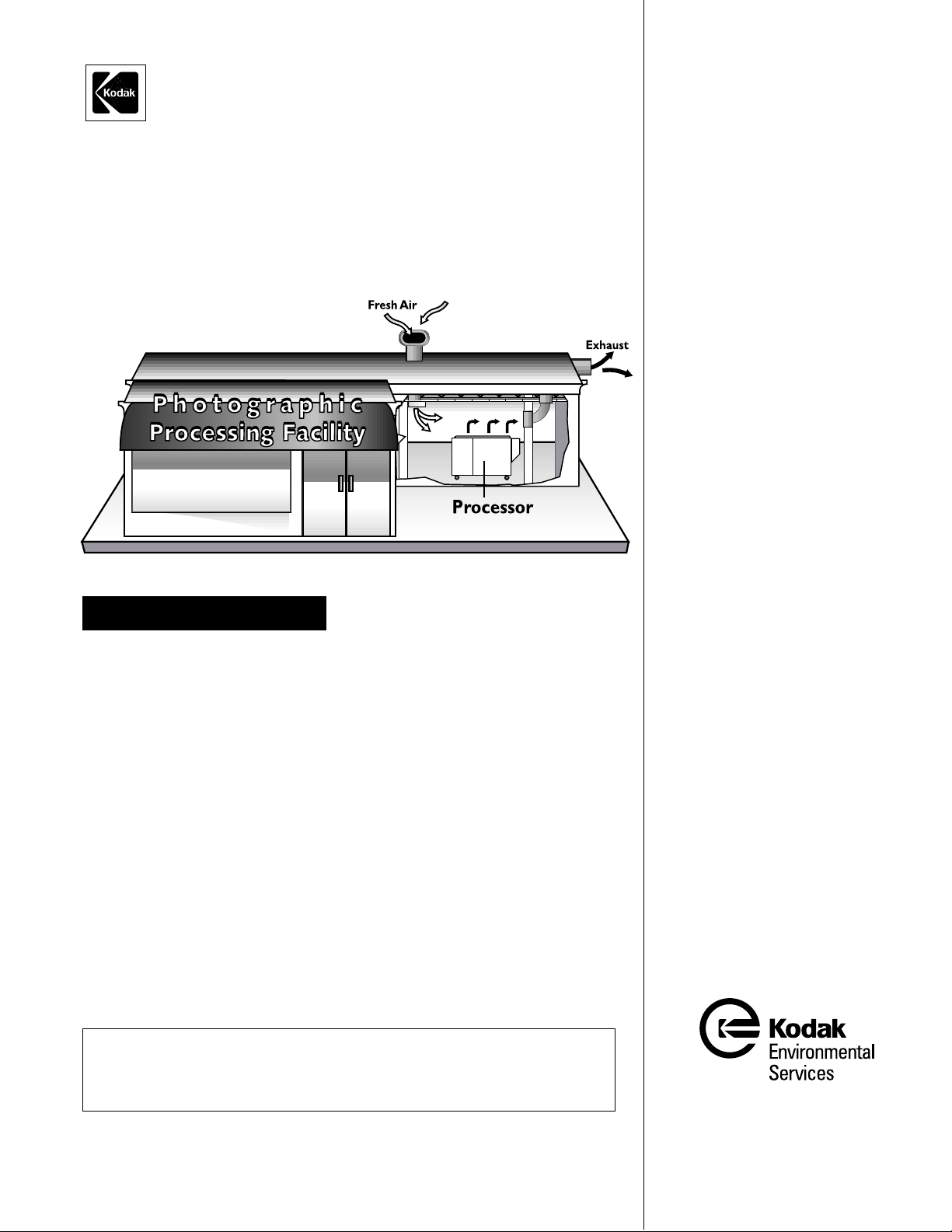

Indoor Air Quality and Ventilation in

Photographic Processing Facilities

J-314(ENG) $10.00

Kodak’s health, safety,

and environmental

publications ar e avai l ab l e

to help you manage your

photographic proce ssin g

operations in a safe,

environmentally sound

and cost-effective manner

INTRODUCTION

The Occupational Safety and

Health Administration (OSHA)

presents a framework of federal

regulations that set chemical

exposure standards for the

workplace environment. These

standards outline allowable limits

that employees may be safely

exposed to during the work day.

Effective ventilation systems are an

important tool that will help

minimize employee exposure to

photographic processing

chemicals. While photographic

processing facilities are typically

considered to be a low hazard

workplace, indoor air quality

environment can be improved if

well engineered ventilation

systems are installed.

This publication will provide

information on the following

topics:

• Indoor air quality

• Exposure concepts

• Air contaminants

• Exposure standards and

guidelines

• Methods of evaluation

• Ventilation and work practice

control measures

This publication is a part

of a series of publications

on health and safety

issues affecting photographic

processing facilities.

It will help you understand

the role and proper use of

ventilation systems in the

workplace.

This publication is meant to assist others with their compliance programs. However, this is

not a comprehensive treatment of the issues. We cannot identify all possible situations and

ultimately it is the reader’s obligation to decide on the appropriateness of this information to

his/her operation.

©Eastman Kodak Company, 2002

Page 2

INDOOR AIR QUALITY (IAQ)

The quality of the air in our homes,

schools, and places of business is an

important environmental health

issue. It is estimated that we spend

over 90% of our time indoors. It is

also important to note that the

design of buildings and ventilation

systems has changed dramatically

over the last 50 years as we have

moved toward more energy

efficient, climate controlled

environments. New or remodeled

buildings are more air tight, which

leads to less air exchange between

indoor air and fresh outdoor air. To

ensure good indoor air quality,

adequate fresh outdoor air must be

brought indoors. You can no longer

rely on leaking windows or other

pathways for outdoor air

infiltration. Indoor air quality (IAQ)

depends upon the ability of a

ventilation system to remove or

control the contaminants generated

within a space to acceptable levels.

When there is insufficient fresh

dilution air, IAQ problems can occur

which may result in a variety of

symptoms in building occupants

including:

• headache

• sinus congestion

• nausea

• eye, nose and throat irritation

• sneezing

• a metallic or sweet taste in mouth

• dizziness

Two terms are used to describe

IAQ health-related problems.

Sick Building Syndrome (SBS):

describes cases in which building

occupants experience acute health

and comfort effects that are

apparently linked to the time they

spend in the building, but in which

no specific illness or cause can be

identified. Basically, people enter

the building and experience

symptoms which clear up after they

leave the building.

Building Related Illness (BRI):

refers to symptoms of diagnosable

illness that can be directly attributed

to environmental agents (chemical,

biological or physical) in the

building air. In other words, people

enter and become ill from a known

agent in the building air but do not

necessarily get better after they

leave the building (examples:

Legionnaire’s disease, respiratory

infections, and humidifier fume

fever).

The causes of poor IAQ continue

to be studied extensively. In the

1980s the National Institute of

Occupational Safety and Health

(NIOSH) studied over 600 buildings

and identified the following as

potential causes of poor IAQ:

Inadequate ventilation 52%

Inside sources 17%

Outside sources 11%

Biological 5%

Building fabric 3%

Unknown 12%

Recent studies have lead some

experts to believe that biological

contamination (molds, fungi,

bacteria) may account for up to 30%

of the IAQ problems in buildings.

To help prevent IAQ problems,

we recommend that you assemble a

comprehensive program that is

preventive in focus. Specific

performance elements of your IAQ

program should include:

1. Developing and maintaining an

IAQ profile for each building

(year built, tenant operations,

number of people, type of

HVAC).

2. Developing and maintaining a

thorough understanding of

your IAQ requirements and

processes.

3. Maintaining up-to-date line

drawings and equipment

schedules for each HVAC

system.

4. Documenting the operational

parameters for each HVAC

system including scheduled

time of operation, temperature

and humidity set points,

seasonal variations, outside air

requirements, air flow

parameters.

5. Providing a process to identify,

investigate, track and respond

to IAQ-related complaints.

6. Maintaining a written

maintenance program and

relevant history of each HVAC

unit.

7. Providing a process to review all

major projects in or near the

building for their IAQ

implications.

8. Ensuring that HVAC systems

are commissioned and

periodically balanced.

9. Ensuring that the performance

of local exhaust systems are

periodically assessed.

10. Providing a process to review

health, safety and

environmental implications of

maintenance and housekeeping

chemicals used in the facility for

remodeling or construction

activities that may impact IAQ.

11. Requiring compliance with local

regulations or company

standards regarding smoking in

the workplace.

12. Requiring that personnel

involved in the design,

operation, evaluation and

maintenance of HVAC systems

are properly trained and aware

of new IAQ regulations and

trends.

Indoor Air Quality and Ventilation in Photographic Processing Facilities • J-314(ENG) 2

Page 3

EXPOSURE CONCEPTS

ROUTES OF EXPOSURE

In a work environment where

chemicals are used, an individual

may potentially be exposed in three

ways:

• inhalation

• skin and eye contact

• ingestion

Inhalation is the most common

route of exposure for airborne

particulates, gases, and vapors.

Inhalation exposures are important

because many chemicals that enter

the lungs can pass directly into the

blood stream and be transported to

other areas of the body.

Skin contact can also be a

significant source of exposure which

can lead to adverse health effects.

Some chemicals can be absorbed

into the body through the skin while

others may cause irritation or rashes

(dermatitis). In addition, some

chemicals are potential eye irritants.

Ingestion is not con sidered to be a

significant problem in the

workplace. Inadvertent ingestion of

chemicals may occur if food or

beverages are consumed in chemical

handling areas or if good personal

hygiene practices are not followed,

i.e., washing hands before eating,

drinking, smoking, etc.

Air contaminants: are chemicals

that may be present in the air that

could be inhaled and may produce

adverse effects. These effects can be

divided into two classes:

• acute

health effects—an adverse

effect resulting from a single

exposure with symptoms

developing almost immediately

or shortly after exposure; the

effect is usually of short duration.

Symptoms may include irritation,

headache, dizziness, or nausea.

• chronic health effects—adverse

effects resulting from repeated

low level exposure, with

symptoms that develop slowly

over a long period of time. These

may affect target organs such as

the liver, kidney, or lungs or cause

cancer.

Dose Response: All chemicals are

toxic if taken into the body by the

right route of exposure and at a high

enough dose. As the dose increases,

there is a corresponding effect or

response.

Chemicals that require large doses

or exposure concentrations to

produce an adverse effect have a

low toxicity, while chemicals that

require smaller doses to produce an

adverse effect are considered more

toxic. For example, acetic acid is

irritating to the eyes and upper

respiratory system at low

concentrations, about 10 ppm.

Isopropyl alcohol is not irritating to

the eyes until concentrations reach

over 400 ppm. Based on this

comparison, acetic acid causes an

irritation at much lower

concentrations than isopropyl

alcohol.

AIR CONTAMINANTS

The air within buildings usually

contains a variety of air

contaminants. These contaminants

can originate from outside sources

(car/truck exhaust) or emissions

from inside sources (office

equipment, furnishings, carpet,

people, kitchens, janitorial

activities).

Whatever the source,

contaminants in the air fall into one

of two physical states of matter.

They are either:

• gases and vapors, or

• solids (particulates)

Gases/Vapors: The difference

between gases and vapors is their

physical state at standard

temperature and atmospheric

pressure (STP, 22.5°C, and 760 mm

Hg). A gas is in the gaseous state at

STP (examples: nitrogen, carbon

dioxide, sulfur dioxide). A vapor is a

gas from a substance that at STP is a

liquid (example, acetic acid).

Particulates: There are several

forms of particulate matter that can

be airborne. These include:

• dust

• fumes

• smoke

• mists

Dust results from the application

of energy to matter, by grinding,

sifting pouring solids, paper cutting,

etc. Dust particles have to be small

enough and light enough to be

airborne.

Fumes are generated by the

condensation of particles in the

vapor state from heated metals.

Fumes are typically smaller than

dust, more soluble, and are more

physiologically active. Fumes are

not generated during normal

photographic processing

operations.

Smoke results from incomplete

combustion and is made up of

extremely fine particles, even

smaller than fumes. Smoke is

extremely complex chemically,

containing thousands of chemical

substances. Unless something is

burning, smoke is not generated

during photographic processing

operations.

Mists result from the dispersion

of fine droplets by aerosolization of

any liquid (spray cans, nitrogen

agitation of tanks, electroplating).

Mists can be formed during the

mixing, recirculation or pouring of

liquids. Mist can also be generated

from foam on the surface of a liquid.

Indoor Air Quality and Ventilation in Photographic Processing Facilities • J-314(ENG) 3

Page 4

As the bubbles burst, tiny droplets

of the liquid are released into the air.

The composition of a mist is usually

the same as the liquid from which it

was generated.

ANTICIPATED AIR

CONTAMINANTS

FROM PHOTOGRAPHIC

PROCESSING

OPERATIONS

Potential air contaminants

associated with photographic

processing operations will be

determined by the specific process

chemistry and the operating

conditions of the equipment. Some

photographic processing solutions

release small amounts of vapors

such as acetic acid and benzyl

alcohol or gases such as ammonia, or

sulfur dioxide. High-temperature

processing and nitrogen-burst

agitation of tank solutions may

increase the release of chemicals

into the air and generate mists from

the photographic processing

solutions. Depending on the

concentration in the air, these

chemicals could be irritating to the

eyes and respiratory tract, or create

odors. Although odor does not

always indicate safe versus unsafe

conditions, strong odors or the

presence of eye and/or respiratory

irritation can indicate that there is

not sufficient general dilution

ventilation or that the local exhaust

systems may not be capturing the air

contaminants effectively at their

source.

In order to assess whether or not

exposure to airborne chemicals

presents a health and safety hazard,

several exposure standards and

guidelines are available for

comparison.

EXPOSURE STANDARDS AND GUIDELINES

THE OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY AND HEALTH ADMINISTRATION (OSHA)

In 1970, OSHA reviewed existing

exposure guidelines and consensus

standards in the workplace, and

adopted these as OSHA regulations.

These exposure standards set

airborne concentration limits and

are legally enforceable. Two of the

major references used by OSHA at

that time were the 1968 Threshold

Limits Values (TLVs) published by

the American Conference of

Governmental Industrial H ygienists

(ACGIH) and Acceptable

Concentrations of Toxic Dusts and

Gases published by the American

National Standards Institute (ANSI).

Since 1970, OSHA has established

approximately 28 new chemicalspecific standards. These new

standards such as the one for

formaldehyde, are much more

comprehensive and detailed. These

new standards include additional

requirements for written programs,

training, personal protective

equipment, control measures,

medical surveillance, etc.

The airborne exposure limits

established by OSHA include:

Permissible Exposure Limit

(PEL): The allowable limit that is

representative of a worker’s

exposure, averaged over an 8-hour

day.

Short-term Exposure Limit

(STEL): The allowable limit that is

representative of a worker’s

exposure, averaged over 15 minutes.

Ceiling Limit (C): The airborne

concentration that is representative

of a worker’s exposure that should

not be exceeded.

Action Level (AL): For the

comprehensive standards

established by OSHA, an Action

Level may be specified. The Action

Level is typically

the concentration at which you may

have to address certain compliance

requirements such as employee

monitoring, training, or medical

surveillance.

1

⁄

of the PEL and is

2

AMERICAN CONFERENCE OF GOVERNMENTAL INDUSTRIAL HYGIENISTS (ACGIH)

ACGIH is a professional

organization whose members work

within the government or academia.

This organization annually

publishes a booklet entitled

Threshold Limit Values (TLVs) for

Chemical Substances and Physical

Agents and Biological Exposure

Indices (BEIs). ACGHI TLVs are

exposure guidelines and do not

have the effect of law. These values

change in response to new data and

are usually more rapidly updated

than OSHA limits.

The Threshold Limit Value (TLV)

refers to airborne concentrations of

substances and represents

conditions under which it is

believed that nearly all workers may

be repeatedly exposed day after day

without adverse health effects.

The ACGIH TLVs include:

Threshold Limit Value-TimeWeighted Average (TLV-TWA):

The time-weighted average

concentration for a normal 8-hour

workday and a 40-hour work week,

to which nearly all workers may be

repeatedly exposed, day after day,

without adverse effect.

Indoor Air Quality and Ventilation in Photographic Processing Facilities • J-314(ENG) 4

Page 5

Threshold Limit Value-Short-

Term Exposure Limit (TLV-STEL):

The 15-minute TWA concentration

which should not be exceeded at any

time during a workday even if the 8hour TWA is within the TLV-TWA.

Exposure above the TLV-TWA up to

the STEL should not be longer than

15 minutes and should not occur

more than four times per day with at

least 60 minutes in between

exposures in this range.

Threshold Limit Value-Ceiling

(TLV-C): The concentration that

should not be exceeded during any

part of the working exposure.

OSHA Limits vs ACGIH

Guidelines: OSHA limits are legally

enforceable, whereas ACGIH limits

are guidelines. In most cases, the

ACGIH guidelines are the same or

lower than OSHA limits (there are a

few exceptions). When the values

are not the same, it is prudent to

follow the lower, more conservative

value.

Examples:

Chemical

Acetic acid 10 ppm 10 ppm

Ammonia 50 ppm 25 ppm

Formaldehyde 0.75 ppm 0.3 ppm

Sulfur dioxide 5 ppm 2 ppm

OSHA

PEL 8-hour

ACGIH

TLV 8-hour

(ceiling)

METHODS OF EVALUATION

THE PURPOSE OF COLLECTING AIR SAMPLES

Air samples are sometimes collected

to evaluate potential worker

exposure levels for comparison to

published exposure standards or

guidelines. The purpose of the

measurement may vary depending

on whether you are interested in

short-term exposure, full shift

exposure, or the exposure incurred

during a specific step or process. The

measurements represent a sampling

of the actual working conditions at

the time of sampling. Generally, the

more sampling data that are

available for a certain job/process/

task under a variety of conditions,

the better understanding and

confidence you will have in the

exposure measurements during that

process. As illustrated in Figure 1,

actual exposure can vary

substantially during the day. In

some cases, full-shift monitoring

may be the goal while in others, the

goal may be to understand shortterm exposure.

Figure 1

Typical Exposure Scenario

Actual

OSHA PEL

Concentration (ppm)

Basic Definitions

Sensitivity or Precision: how

reproducible is the sampling

method.

Accuracy: how close to the true value

is the sampling method.

8-hr

Avg.

4pm2pmNoon10am8am

MEASUREMENT TECHNIQUES

Direct Reading

These are measurement techniques

that can immediately indicate the

concentration of aerosols, gases, or

vapors by some means such as a dial

or meter or noting the color change of

an indicator chemical.

Colorimetric Detector Tubes

Several colorimetric, direct reading

detector tubes are useful for quick

assessments of airborne

contaminants associated with

photographic processing. A special

pump draws a specific volume of

room air through a detector tube. If

the contaminant is present, a color

change occurs along the length of the

tube that is directly proportional to

the concentration of the contaminant

in the air. Tubes are available for

acetic acid, sulfur dioxide, ammonia,

and many other gases and vapors.

The tubes are easy to use and

generally have an accuracy of ± 25%.

Other chemicals in the air may

interfere with the accuracy and

sensitivity of the tubes.

Indoor Air Quality and Ventilation in Photographic Processing Facilities • J-314(ENG) 5

Page 6

Direct Reading Instruments

Many different direct reading

instruments are available for air

sampling measurements. Some of

these can be very specific to a

chemical (e.g., sulfur dioxide

analyzers) while others are

nonspecific (e.g., organic vapor

analyzer with photoionization [PID]

or flame ionization [FID] detectors).

Calibrate all instruments before and

after making any measurements.

Samples with Subsequent Laboratory Analysis

There are many air sampling

techniques that rely on collecting a

known volume of air followed by

laboratory analysis.

Passive diffusion badges are easy

to use and excellent for measuring

many volatile organic compounds.

This method is most useful for

measuring (quantifying) known

airborne contaminants. Although

passive badges are commonly

employed for measuring full shift

average exposures, they also can be

useful for short-term exposure

measurements.

Solid sorbent/tubes/bubblers are

similar in many ways to passive

badges except that air must be

actively drawn through the

sampling device using a calibrated

sampling pump. Numerous

laboratory techniques are available

for specific chemical analysis

following sample collection.

Grab samples refer to collecting a

volume of air at a certain point in

time. This technique can be useful

for assessing short-term exposures.

New canister samplers allow for the

sample to be drawn in over a much

longer period of time, if desired.

This technique is most useful for

volatile organic hydrocarbons.

VENTILATION AND WORK PRACTICE CONTROL MEASURES

Proper ventilation is important to

assure a safe and comfortable indoor

environment for photographic

processing areas. Several common

potential indoor air contaminants

can be associated with photographic

processing. These include: acetic

acid, sulfur dioxide, and ammonia.

These chemicals may be eye and

respiratory tract irritants depending

on their airborne concentrations.

Exposure guidelines and standards

for these chemicals have been

established to prevent significant

eye or respiratory tract irritation in

most workers. Significant eye or

respiratory tract irritation during

normal photographic processing or

maintenance operations may

indicate elevated levels of these

materials and the need for better

control.

General control strategies in order

of preference include:

• chemical substitution (where

possible)

• engineering controls (ventilation,

enclosures, process isolation)

• work practices or administrative

controls (operating procedures,

employee rotation)

• personal protective equipment

(safety glasses, gloves,

respirators)

Engineering controls that have

proven to be effective in minimizing

airborne levels of photographic

processing chemicals include:

• Good design and layout for

process flow and ergonomic

considerations

• Using dilution and local exhaust

ventilation

• Providing covers for processing

equipment tanks and chemical

storage tanks

GOOD FACILITY DESIGN

The proper location and layout of

photographic processing operations

is an important element in designing

a safe and healthy workplace.

General ventilation systems have

the potential to recirculate a

significant percentage of the air

returning from the photographic

processing areas. If the general

ventilation system also supplies

non-photographic processing work

areas, it is possible that the

photographic processing odors may

also impact these areas.

VENTILATION

Kodak studies of potential worker

exposure during automated

photographic processing operations

have indicated that vapors and

gases can be controlled to acceptable

levels through good general room

ventilation (dilution ventilation).

However, in some cases, local

exhaust for enclosed and/or open

tanks may be recommended.

Indoor Air Quality and Ventilation in Photographic Processing Facilities • J-314(ENG) 6

Page 7

DILUTION VENTILATION

Dilution or general ventilation is

simply bringing in and distributing

enough fresh, uncontaminated air

(preferably outdoor air) to dilute the

indoor air contaminants to an

acceptable level.

Minimum recommendations for

general ventilation for buildings and

processes are provided by the

American Society of Heating,

Refrigeration and Air Conditioning

Engineers (ASHRAE).

For photographic processing

operations, ASHRAE Standard 621989 recommends:

• 0.5 cubic feet per minute (cfm) of

fresh outside air, per square foot

2

(ft

) of floor area (0.5 cfm/ft2),

assuming a maximum occupancy

of 10 persons/1000 ft

darkrooms.

For example, if the room where

photoprocessing takes place is 10 ft

x 20 ft x 8 ft, the floor area is 200 ft

and the room volume is 1600 ft

Based on 0.5 cmf/ft

need to supply at least 200 x 0.5 or

100 cfm of fresh outside air to the

space.

The number of “room air changes

per hour” is determined by the fresh

air supply rate. In the example, in

one hour 6000 ft

3

min) of fresh air entered the space

(room volume: 1600 ft

the room air changes per hour, you

divide the total amount of fresh air

that has entered the space by the

volume of the room:

3

6000 ft

/hr/1600 ft3 room volume =

3.75 air changes per hour.

It is important to note that the

ASHRAE recommendations

represent the minimum amount of

fresh air that should be supplied to

the space. Past recommendations

from Kodak have been as high as ten

air changes per hour.

2

in

3

2

, you would

.

(100 ft3/min x 60

3

). To calculate

2

When using dilution ventilation,

airborne contaminants are not

captured at the source. Instead, the

contaminated air is turned over and

replaced quickly enough to

minimize potential exposure and

related odors. To be most effective,

make sure you properly position the

supply air inlets and return air

outlets for good mixing/dilution of

the room air. Their placement must

minimize the potential for “short-

circuiting” or direct flow of supply

air to return with minimum room air

mixing (Figure 2). For a large room,

you may need supply air inlets and

return air outlets throughout the

room. Do not position the inlet and

outlets too close together.

Figure 2

Open tank processor with general room

dilution ventilation

LOCAL EXHAUST

VENTILATION

Local exhaust ventilation is used to

capture air contaminants close to the

source of generation, before they can

enter the general work room air.

This type of ventilation can be very

effective at controlling airborne

contaminants. A general room

exhaust system will reduce airborne

Supply Fresh Air

levels but is not considered local

exhaust ventilation. A local exhaust

system may be more expensive to

install than a general dilution

ventilation system, but requires less

air (and energy) to effectively

control the airborne contaminants.

When designing local exhaust

systems, the objective is to capture

contaminants close to the source and

draw the contaminated air stream

away from the air you breathe.

Avoid placing workstations

between the source (photographic

processor) and the inlet to the

exhaust hood.

You can find information on the

proper design of local exhaust

systems in the ACGIH Industrial

Ventilation Manual (ACGIH 2001).

The design must also consider the

required “make-up” air system

you’ll need to replace and condition

the air that is exhausted from the

building. In addition, it is also

important to review local laws and

ordinances regarding local exhaust

and any permit requirements with

local, state, or federal regulators.

RECOMMENDATIONS

MINILABS

General dilution ventilation

following the minimum fresh air

recommendations from ASHRAE

(0.5 cfm/ft

effective at controlling air

contaminants associated with

minilab processes. In some cases,

venting the dryer section of the

processor to outdoors may be

appropriate to prevent excessive

humidity (greater than 60% relative

humidity) and odors in the

workplace. Consult with the

processor manufacturer for specific

venting requirements.

2

of floor area) should be

Indoor Air Quality and Ventilation in Photographic Processing Facilities • J-314(ENG) 7

Page 8

S

LARGE PHOTOGRAPHIC PROCESSING FACILITIES

The most effective controls for

minimizing potential airborne

exposures and odors related to large

photographic processing operations

are a combination of both local

exhaust and dilution ventilation

(Figure 3). Fresh dilution air

be supplied to the darkroom at a rate

of 150 cfm per machine. If a machine

extends through a barrier into

another room, supply fresh dilution

air to both rooms. Depending on the

process chemistry, you may need

local exhaust at uncovered stabilizer

tanks or at the bleach fix tanks at a

rate of 170 cfm per machine

(Figure 4). In many cases, exhaust is

also provided at the dryer section to

help control heat and humidity in

the room. An exhaust rate slightly

greater than the supply rate results

in a negative room air pressure

which reduces the potential for air

contaminants and odors for

escaping from the photographic

processing area to any adjacent

areas.

Open-machine, general room

Supply Fresh Air

150 cfm

Figure 3

exhaust ventilation

1

should

Exhaust to Outdoors

170 cfm

Figure 4

Open-machine with a

slot hood ventilation

upply Fresh Air

150 cfm

Exhaust to Outdoors

170 cfm

If solution tanks are enclosed or covered, the fresh air supply rate may be

reduced to 90 cfm and the exhaust rate to 100 cfm per machine (Figure 5).

1. Means “uncontaminated air” which includes

the ASHRAE recommendation of 0.5 cfm/ft

2

.

Indoor Air Quality and Ventilation in Photographic Processing Facilities • J-314(ENG)8

Page 9

Figure 5

Enclosed-machine

ventilat i on

Supply Fresh Air

90 cfm

Exhaust to Outdoors

100 cfm

In addition, it is important to

follow the processing equipment

manufacturer’s recommendations

regarding venting of the dryer

section of the processor. Whenever

possible, dryer vents should be

ducted to the outdoors to prevent

the build up of excessive

temperature and humidity in the

workplace.

Install all local exhaust systems

that vent to the outdoors in

accordance with local, state, and

federal regulations.

EFFECTIVE COVERS FOR PROCESSING EQUIPMENT AND CHEMICAL STORAGE TANKS

Covers on photographic processing

equipment and chemical storage

tanks can effectively minimize the

amount of gases, vapors or mists

that may enter the work area. In

addition, covers also reduce the

potential for contamination of the

processing solutions. Covers should

be fabricated from durable, nonreactive materials and should cover

as much of the open surface of the

tank as possible. In many cases,

effective tank covers combined with

good general room ventilation, and

proper operation and maintenance

may be all that is needed to control

odors and airborne exposure to

photographic processing chemicals.

In situations where local exhaust is

needed for a covered tank, 25 - 30

cubic feet per minute (cfm) per

square foot of tank area is adequate.

Work practices controls:

• Proper operation and

maintenance of photographic

processing equipment;

• Prudent techniques for handling

chemicals.

PROPER OPERATION AND MAINTENANCE OF PHOTOGRAPHIC PROCESSING EQUIPMENT

The level of airborne contamination

generated from photographic

processing solutions can be affected

by how the processing equipment is

operated. It is important to follow

the manufacturer’s recommended

operating procedures for operating

temperature, the agitation of

processing solutions, and

processing speeds.

In addition, draining and flushing

processing equipment tanks with

cold water prior to rack removal or

maintenance operations can also be

effective at controlling short-term

exposures to processing solutions.

The health, comfort, and

efficiency of personnel, as well as the

proper conditions for processing,

handling and storage of

photographic materials depends on

a suitable indoor air environment.

Modern ventilation techniques

include several factors: air supply,

air movement; air distribution; air

conditioning or control of

temperature and humidity; air

pressure adjustment; and air

cleaning or filtration. If you plan a

photographic plant of considerable

size, consult a ventilation and air

conditioning engineer as early as

possible in the planning stages. If the

designer has the opportunity to

make suggestions in the early stages

of planning, the result may be a

better overall design, and lower

installation and operating costs.

Indoor Air Quality and Ventilation in Photographic Processing Facilities • J-314(ENG) 9

Page 10

REGULATORY AND ASSOCIATED REFERENCES

Subject Resource

Exposure Standard OSHA, 29 CFR 1910.1000, Tab le Z1, Z2, and Z3

Formaldehyde Standa rd OSHA, 29 CFR, 11910.1000-1048

Design of Ventilation System s ACGIH Industrial Ventilat ion Manual (ACGIH 2001)

Design of Ventilation Systems

(Ventilation Recommendations)

Theshold Limit Values Threshold Limits Values (lat est edition), American Conferen ce of G ov ernmental Industrial Hygien ist s

Indoor Air Quality Building Air Quality, A Guide for Building Owners and Facility Managers, U.S. Environmental Protection

Indoor Air Quality Indoor Air Quali t y and H VAC Sy st em s, D av i d W. Bea rg , Lew is Publishers, 1993

American Society of Heating, R efr ig er at ion and Air Condition Engineers Sta ndard 62-1989

Agency

Indoor Air Quality and Ventilation in Photographic Processing Facilities • J-314(ENG) 10

Page 11

MORE INFORMATION

If you have environmental or safety questions about

Kodak products, services, or publications, contact

Kodak Environmental Services at 1-585-477-3194, or

visit KES on-line at www.kodak.com/go/kes.

Kodak also maintains a 24-hour health hotline to

answer questions about the safe handling of

photographic chemicals. If you need health-related

information about Kodak products, call

1-585-722-5151.

For questions concerning the safe transportation of

Kodak products, call Kodak Transportation Services at

1-585-722-2400.

Additional information is available on the Kodak

website and through the Canada faxback system.

The products and services described in this

publication may not be available in all countries. In

countries other than the U.S., contact your local Kodak

representative, or your usual supplier of Kodak

products.

J-311 Hazard Communication for Photographic

Processing Facilities

J-312 Personal Protective Equipment Requirements in

Photographic Proces sing Facilities

J-313 Occupational Noise Exposure Requirem en ts for

Photographic Proces sing Facilities

J-315 Special Materials Management in Photograp hi c

Processing Facilities

J-316 Emergency Preparedness for Photographic

Processing Facilities

J-317 Injury and Illness Management for Photographic

Processing Facilities

Indoor Air Quality and Ventilation in Photographic Processing Facilities • J-314(ENG) 11

Page 12

For more information about Kodak Environmental Services,

visit Kodak on-line at:

www.kodak.com/go/kes

Many technical suppo rt publications for

Kodak products can be se nt to you r f ax m ac hi ne

from the Kodak Information Center. Call:

Canada 1-800-295 -55 31

—Available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week—

If you have questions about KODAK product s, call Kodak.

In the U.S.A.:

1-800-242-2424, Ext . 19, Mo nday–Friday

9 a.m.–7 p.m. (Eastern time)

In Canada:

1-800-465-6325, Monday–Friday

8 a.m.–5 p.m. (Eastern time)

This publication is a guide to the Federal Health and Safety Regulations

that apply to a typical photographic processing fac ility . Local or state

requireme nt s ma y al so ap pl y . Ver i fy th e s pec if i c r eq ui re ment s fo r y our

facility with your legal counsel.

Indoor Air Quality and Ventilation in

Photographic Processing Facilities

KODAK Publication No. J-314(ENG)

CAT No. 184 9298

This publication is printed on recycled paper that contains

50 percent recycled fiber and 10 percent post-consumer material.

EASTMAN KODAK COMPANY • ROCHESTER, NY 14650

Kodak and “e" mark are trademarks.

Revised 9/02

Printed in U.S.A.

Loading...

Loading...