Page 1

®

Not Going to Waste

The role of food waste disposers as part of a total waste management solution

Page 2

Introduction

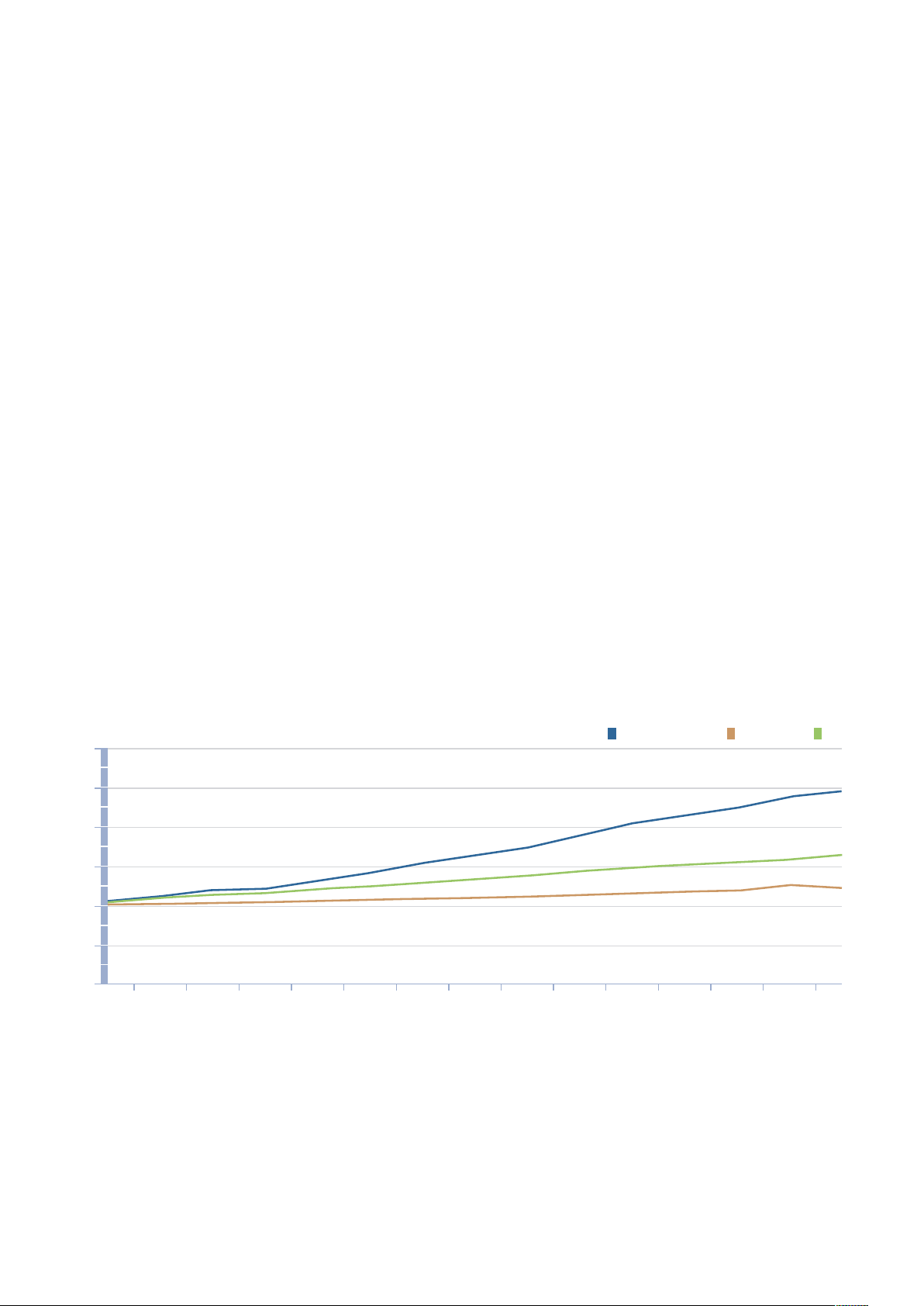

Waste generation, Population & GVA, 1997-2012

INDEX WASTE GENERATED POPULATION GVA

300

250

200

150

100

50

0

1997-98 1998-99 1999-00 2000-01 2001-02 2002-03 2003-04 2004-05 2005-06 2006-07 2007-08 2008-09 2009-10 2010-11 2011-12

In the face of a rapidly growing population, nding an

appropriate method of dealing with household waste

continues to be a matter of heightened importance. Food

waste accounts for more than 30% of the total rubbish

in household garbage bins therefore suitable treatment

reduce their dependency on unpredictable price uctuations

of fuels. From a waste management and environmental

impact perspective, state and local governments are

committed to the issue of climate change and proving

measures to avoid methane emissions from landlls.

options for this organic component could help alleviate a

global waste problem.

Therefore alternative methods of food disposal would

potentially impact signicantly. Food waste disposers while

At a global level countries are keen to reduce their reliance

on fossil fuels and provide alternatives to wood fuel. At a

national level, residents, commerce and industries want to

serving a practical function in terms of household hygiene

and convenience have the potential to provide a number of

benets on a far broader scale.

What happens to food that is thrown away?

Australia is heavily dependent on landll as a means of

waste management. In fact, the majority of non-recycled

waste will end up in landll sites.

Estimates suggest each household produces close to 1.5

tonnes of waste each year. And nearly half (47% in 2009-

10) of all household waste is organic – namely food scraps.

One concern is that waste generation has been growing

at a disproportionate rate. Between 1997 and 2012 – when

overall population growth was 22% – the volume of waste

production jumped by 145%.

3

The problem here is that landlls are effectively an ‘out of sight,

out of mind’ solution. They potentially have a detrimental impact

on surrounding air, water and land quality. There are, however,

better ways of managing wastes, especially food waste.

A by-product of anaerobic organic waste decomposition is

2

a gas which consists of around 50% methane. Methane in

the atmosphere is a strong contributor to climate change,

being over 20 times more potent in this regard than carbon

dioxide.

4

harnessed as a valuable renewable energy source. Using

a food waste disposer can facilitate just that without the

social dis-amenity associated with landlling.

1

However, if captured and ‘cleaned’, it can be

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics Waste Generation, Population & GVA 1997-2012

Food waste and renewable energy

Instead of piling food waste into bins and, ultimately, landll,

food waste disposers can be used to grind food scraps

which is then sent via the sewerage system to a wastewater

treatment plant. Here appropriate facilities use a process

called ‘anaerobic digestion’, to convert waste to biogas.

Anaerobic digestion is a collection of processes by which

microorganisms break down biodegradable material such as

organic food waste in the absence of oxygen.

5

The anaerobic

digestion process produces a biogas methane.

When cleaned, the methane fraction can be stored,

pressurised and used to generate on-site power and heat.

The power can be used on-site with surplus fed into the

electricity grid. Methane can also be upgraded to natural

gas-quality biomethane, and a by-product of the digestion

process is a nutrient-rich digestate which can be used as

fertiliser

6

for areas such as golf courses, playing elds

and pasture lands.

5

Page 3

Anaerobic Digestion in Australia

The concept of using anaerobic digestion to produce

valuable biogas and hence renewable energy has actually

existed for many years. However the technology has

continued to be rened and countries such as Denmark,

Sweden and the UK are now championing a true paradigm

shift in waste management. With that said, Australia’s

commitment to wastewater treatment is also growing.

Sydney Water is just one of many wastewater treatment

companies employing the process of anaerobic digestion,

boasting 14 plants with anaerobic digestion facilities. Eight

of the plants have cogeneration (biogas burned in engines

to generate electric power), producing over 53,000MWh of

electricity per year. Sydney Water aims to harness the natural

anaerobic digestion process to maximise its renewable energy

generation and possibly expand its services to customers

beyond traditional water industry services.

Anaerobic digester systems in Australia are continuing to

be embraced due to further understanding of their benets

and the development of technologies. Over and above the

7

numerous wastewater treatment plants currently employing

anaerobic digestion there are several organisations

providing grants for construction of biogas plants and

installation of digester systems. These organisations include

Low Carbon Australia and the Australian government’s

Clean Technology Investment Program.

Yarra Valley Water has this year completed designs on its

rst dedicated Waste to Energy facility in the northern

suburbs of Melbourne.

Maxcon, an Australian Company specialising in industrial

wastewater treatment and building is set to commence by

the end 2014.

Other Anaerobic Digestion plants processing food waste in

Australia include TPI/Veolia digestor at Camellia, Biogas

plant at Richgrow in Perth, plus several others. With more

and more companies announcing their plans to invest in the

construction of anaerobic digestion plants, adopting wasteto-energy technology, the way we view food waste disposal

is set to change.

8

They have partnered Aquatec-

Slurry and manure

Anaerobic

digester

Food and amenity waste

Digestate

Crops and residues Heat

InSinkErator® Food Waste Disposers

InSinkErator offers a quicker and more efcient way of

dealing with food waste. On a household level, food waste

disposers improve the convenience and hygiene of dayto-day kitchen function. Eliminating organic waste from

bins can improve household comfort and reduce the risk

of attracting vermin or causing odours, particularly when

temperatures climb in the summer.

On a broader scale, however, they can reduce the amount

of waste that goes into landll, with the potential to convert

food waste into renewable energy through anaerobic

digestion processes which capture the gas generated. As

we continue to embrace this technology as a nation, food

waste disposers will play an increasingly pivotal role in a

total waste management solution.

Power

Gas grid

BiomethaneBiogas

Transport fuel

Page 4

®

1

ABS – Waste Disposed to Landll (1370.0 – Measures of Australia’s Progress, 2010)

http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/1370.0~2010~Chapter~Landll%20(6.6.4)

2

Anaerobic Digestion of Biowaste in Developing Countries

http://www.eawag.ch/forschung/sandec/publikationen/swm/dl/biowaste.pdf

3

ABS – Waste Account, Australia, Experimental Estimates, 2013 – Waste Generation by Industry and Households

http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/4602.0.55.005Main%20Features42013?opendocument

4

The Role of Methane

http://earthguide.ucsd.edu/virtualmuseum/climatechange1/03_3.shtml

5

Biogass – Anaerobic Digestion

http://www.biogass.com.au/anaerobic-digestion.html

6

Anaerobic Digestion of Biowaste in Developing Countries

http://www.eawag.ch/forschung/sandec/publikationen/swm/dl/biowaste.pdf

7

Water – Journal of the Australian Water Association

“Codigestion with Glycerole for Improved Biogas Production” M Dawson & S Fitzerald

8

Yarra Valley Water Turning Your Waste to Energy

http://www.yvw.com.au/Home/Aboutus/Ourprojects/Currentprojects/WastetoEnergyfacility/index.htm

Loading...

Loading...