Page 1

GE

LISTED

Grid Solutions

Multilin™ EPM 2200

Power Meter

Instruction Manual

Software Revision: 1.0x

Manual P/N: 1601- 9111-A5

Manual Order Code: GEK-113575D

*1601-911-A5*

Page 2

Copyright © 2016 GE Multilin Inc. All rights reserved.

EPM 2200 Power Meter Instruction Manual for product revision 1.0x.

The contents of this manual are the property of GE Multilin Inc. This documentation is

furnished on license and may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the permission

of GE Multilin. The manual is for informational use only and is subject to change without

notice.

Part number: 1601-9111-A5 (June 2016)

ii

Page 3

Note

GENERAL SAFETY PRECAUTIONS - EPM 2200

• Failure to observe and follow the instructions provided in the equipment manual(s)

could cause irreversible damage to the equipment and could lead to property

damage, personal injury and/or death.

• Before attempting to use the equipment, it is important that all danger and

caution indicators are reviewed.

• If the equipment is used in a manner not specified by the manufacturer or

functions abnormally, proceed with caution. Otherwise, the protection provided by

the equipment may be impaired and can result in Impaired operation and injury.

• Caution: Hazardous voltages can cause shock, burns or death.

• Installation/service personnel must be familiar with general device test practices,

electrical awareness and safety precautions must be followed.

• Before performing visual inspections, tests, or periodic maintenance on this device

or associated circuits, isolate or disconnect all hazardous live circuits and sources

of electric power.

• Failure to shut equipment off prior to removing the power connections could

expose you to dangerous voltages causing injury or death.

• All recommended equipment that should be grounded and must have a reliable

and un-compromised grounding path for safety purposes, protection against

electromagnetic interference and proper device operation.

• Equipment grounds should be bonded together and connected to the facility’s

main ground system for primary power.

• Keep all ground leads as short as possible.

• At all times, equipment ground terminal must be grounded during device

operation and service.

• In addition to the safety precautions mentioned all electrical connections made

must respect the applicable local jurisdiction electrical code.

• Before working on CTs, they must be short-circuited.

• To be certified for revenue metering, power providers and utility companies must

verify that the billing energy meter performs to the stated accuracy. To confirm the

meter’s performance and calibration, power providers use field test standards to

ensure that the unit’s energy measurements are correct.

This product cannot be disposed of as unsorted municipal waste in the European

Union. For proper recycling return this product to your supplier or a designated

collection point. For more information go to www.recyclethis.info.

iii

Page 4

Safety words and definitions

NOTE

The following symbols used in this document indicate the following conditions

Note

Indicates a hazardous situation which, if not avoided, will result in death or serious

injury.

Note

Indicates a hazardous situation which, if not avoided, could result in death or serious

injury.

Note

Indicates a hazardous situation which, if not avoided, could result in minor or

moderate injury.

Note

Note

Indicates practices not related to personal injury.

Indicates general information and practices, including operational information, that

are not related to personal injury.

For further assistance

For product support, contact the information and call center as follows:

GE Solutions

650 Markland Street

Markham, Ontario

Canada L6C 0M1

Worldwide telephone: +1 905 927 7070

Europe/Middle East/Africa telephone: +34 94 485 88 54

North America toll-free: 1 800 547 8629

Fax: +1 905 927 5098

Worldwide e-mail: multilin.tech@ge.com

Europe e-mail: multilin.tech.euro@ge.com

Website: http://www.gegridsolutions.com/multilin

Warranty

For products shipped as of 1 October 2013, GE warrants most of its GE manufactured

products for 10 years. For warranty details including any limitations and disclaimers, see

our Terms and Conditions at

https://www.gegridsolutions.com/multilin/warranty.htm

For products shipped before 1 October 2013, the standard 24-month warranty applies.

iv

Page 5

Table of Contents

1: THREE-PHASE POWER

MEASUREMENT

2: OVERVIEW AND

SPECIFICATIONS

3: MECHANICAL

INSTALLATION

THREE PHASE SYSTEM CONFIGURATIONS ........................................................................... 1-1

WYE CONNECTION ..........................................................................................................................1-1

DELTA CONNECTION ......................................................................................................................1-3

BLONDEL’S THEOREM AND THREE PHASE MEASUREMENT ......................................... 1-4

POWER, ENERGY AND DEMAND ............................................................................................... 1-6

REACTIVE ENERGY AND POWER FACTOR ............................................................................. 1-9

HARMONIC DISTORTION ..............................................................................................................1-11

POWER QUALITY .............................................................................................................................. 1-13

HARDWARE OVERVIEW ................................................................................................................. 2-1

V

OLTAGE AND CURRENT INPUTS ...................................................................................... 2-2

O

RDER CODES ..................................................................................................................... 2-2

M

EASURED VALUES ............................................................................................................ 2-3

U

TILITY PEAK DEMAND .......................................................................................................2-3

SPECIFICATIONS ............................................................................................................................... 2-4

COMPLIANCE ..................................................................................................................................... 2-8

ACCURACY .......................................................................................................................................... 2-9

INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 3-1

ANSI INSTALLATION STEPS .......................................................................................................... 3-2

DIN INSTALLATION STEPS ...........................................................................................................3-3

4: ELECTRICAL

INSTALLATION

5: COM OPTION S:

MODBUS/KYZ OUTPUT

CONSIDERATIONS WHEN INSTALLING METERS ................................................................. 4-1

CT L

EADS TERMINATED TO METER ...................................................................................4-2

CT L

EADS PASS-THROUGH (NO METER TERMINATION) ................................................ 4-3

Q

UICK CONNECT CRIMP CT TERMINATIONS ................................................................... 4-5

V

OLTAGE AND POWER SUPPLY CONNECTIONS .............................................................. 4-6

G

ROUND CONNECTIONS ....................................................................................................4-6

V

OLTAGE FUSES .................................................................................................................. 4-6

ELECTRICAL CONNECTION DIAGRAMS ..................................................................................4-7

D

ESCRIPTION ........................................................................................................................ 4-7

(1) W

YE, 4-WIRE WITH NO PTS AND 3 CTS, NO PTS, 3 ELEMENT ............................ 4-8

(2) W

YE, 4-WIRE WITH NO PTS AND 3 CTS, 2.5 ELEMENT ........................................ 4-11

(3) W

YE, 4-WIRE WITH 3 PTS AND 3 CTS, 3 ELEMENT .............................................. 4-12

(4) W

YE, 4-WIRE WITH 2 PTS AND 3 CTS, 2.5 ELEMENT ...........................................4-13

(5) D

ELTA, 3-WIRE WITH NO PTS, 2 CTS ....................................................................... 4-14

(6) D

ELTA, 3-WIRE WITH 2 PTS, 2 CTS ......................................................................... 4-15

(7) D

ELTA, 3-WIRE WITH 2 PTS, 3 CTS ......................................................................... 4-16

(8) C

URRENT-ONLY MEASUREMENT (THREE-PHASE) .................................................... 4-17

(9) C

URRENT-ONLY MEASUREMENT (DUAL-PHASE) ...................................................... 4-18

(10) C

URRENT-ONLY MEASUREMENT (SINGLE-PHASE) ................................................ 4-19

CONNECTING TO THE RS485/KYZ OUTPUT PORT ............................................................. 5-1

EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL TOC–1

Page 6

6: USING THE METER PROGRAMMING USING THE FACEPLATE ...............................................................................6-1

M

ETER FACE ELEMENTS ..................................................................................................... 6-2

M

ETER FACE BUTTONS ....................................................................................................... 6-2

S

TART UP .............................................................................................................................. 6-3

M

AIN MENU ........................................................................................................................6-4

R

ESET MODE .......................................................................................................................6-4

E

NTER PASSWORD (IF ENABLED) .......................................................................................6-5

C

ONFIGURATION MODE ......................................................................................................6-6

C

ONFIGURING THE SCROLL FEATURE ............................................................................... 6-8

C

ONFIGURING THE CT SETTING ........................................................................................6-9

C

ONFIGURING THE PT SETTING ........................................................................................6-10

C

ONFIGURING THE CONNECTION (CNCT) SETTING ......................................................... 6-11

C

ONFIGURING THE COMMUNICATION PORT SETTINGS .................................................. 6-12

O

PERATING MODE ...............................................................................................................6-14

% OF LOAD BAR ...............................................................................................................................6-15

WATT-HOUR ACCURACY TESTING (VERIFICATION) ...........................................................6-15

I

NFRARED & KYZ PULSE CONSTANTS FOR ACCURACY TESTING ................................. 6-16

GE COMMUNICATOR PROGRAMMING OVERVIEW ............................................................ 6-17

F

ACTORY INITIAL DEFAULT SETTINGS ............................................................................... 6-17

H

OW TO CONNECT USING GE COMMUNICATOR SOFTWARE ......................................6-17

D

EVICE PROFILE SETTINGS ................................................................................................. 6-20

7: COM OPTION B:

BACNET MS/TP WITH

MODBUS TCP/IP

A: EPM 2200

NAVIGATION MAPS

B: MODBUS MAPPING

FOR EPM 2200

BACNET MS/TP .................................................................................................................................. 7-1

EPM 2200 METER BACNET OBJECTS ....................................................................................... 7-2

CONFIGURING COM OPTION B: BACNET MS/TP WITH MODBUS TCP/IP ................. 7-4

R

ESETTING THE ETHERNET CARD ...................................................................................... 7-11

USING THE EPM 2200 METER’S WEB INTERFACE ..............................................................7-11

H

OME WEB PAGE ................................................................................................................. 7-11

BAC

NET OBJECTS STATUS WEB PAGE ............................................................................. 7-13

C

HANGE PASSWORD WEB PAGE ....................................................................................... 7-14

S

TATISTICS WEB PAGE ......................................................................................................... 7-14

R

ESET CONFIGURATION WEB PAGE ...................................................................................7-15

USING THE EPM 2200 IN A BACNET APPLICATION ........................................................... 7-15

INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ A-1

NAVIGATION MAPS (SHEETS 1 TO 4) ........................................................................................ A-1

EPM 2200 N

AVIGATION MAP TITLES: ............................................................................A-1

INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ B-1

MODBUS REGISTER MAP SECTIONS ........................................................................................ B-1

DATA FORMATS ............................................................................................................................... B-2

FLOATING POINT VALUES ........................................................................................................... B-2

MODBUS REGISTER MAP .............................................................................................................. B-3

C: MANUAL REVISION

RELEASE NOTES ................................................................................................................................C-1

HISTORY

TOC–2 EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL

Page 7

GE

Grid Solutions

EPM 2200 Power Meter

Chapter 1: Three-Phase Power

Measurement

Three-Phase Power Measurement

This introduction to three-phase power and power measurement is intended to

provide only a brief overview of the subject. The professional meter engineer or meter

technician should refer to more advanced documents such as the EEI Handbook for

Electricity Metering and the application standards for more in-depth and technical

coverage of the subject.

1.1 Three Phase System Configurations

Three-phase power is most commonly used in situations where large amounts of

power will be used because it is a more effective way to transmit the power and

because it provides a smoother delivery of power to the end load. There are two

commonly used connections for three-phase power, a wye connection or a delta

connection. Each connection has several different manifestations in actual use.

When attempting to determine the type of connection in use, it is a good practice to

follow the circuit back to the transformer that is serving the circuit. It is often not

possible to conclusively determine the correct circuit connection simply by counting

the wires in the service or checking voltages. Checking the transformer connection will

provide conclusive evidence of the circuit connection and the relationships between

the phase voltages and ground.

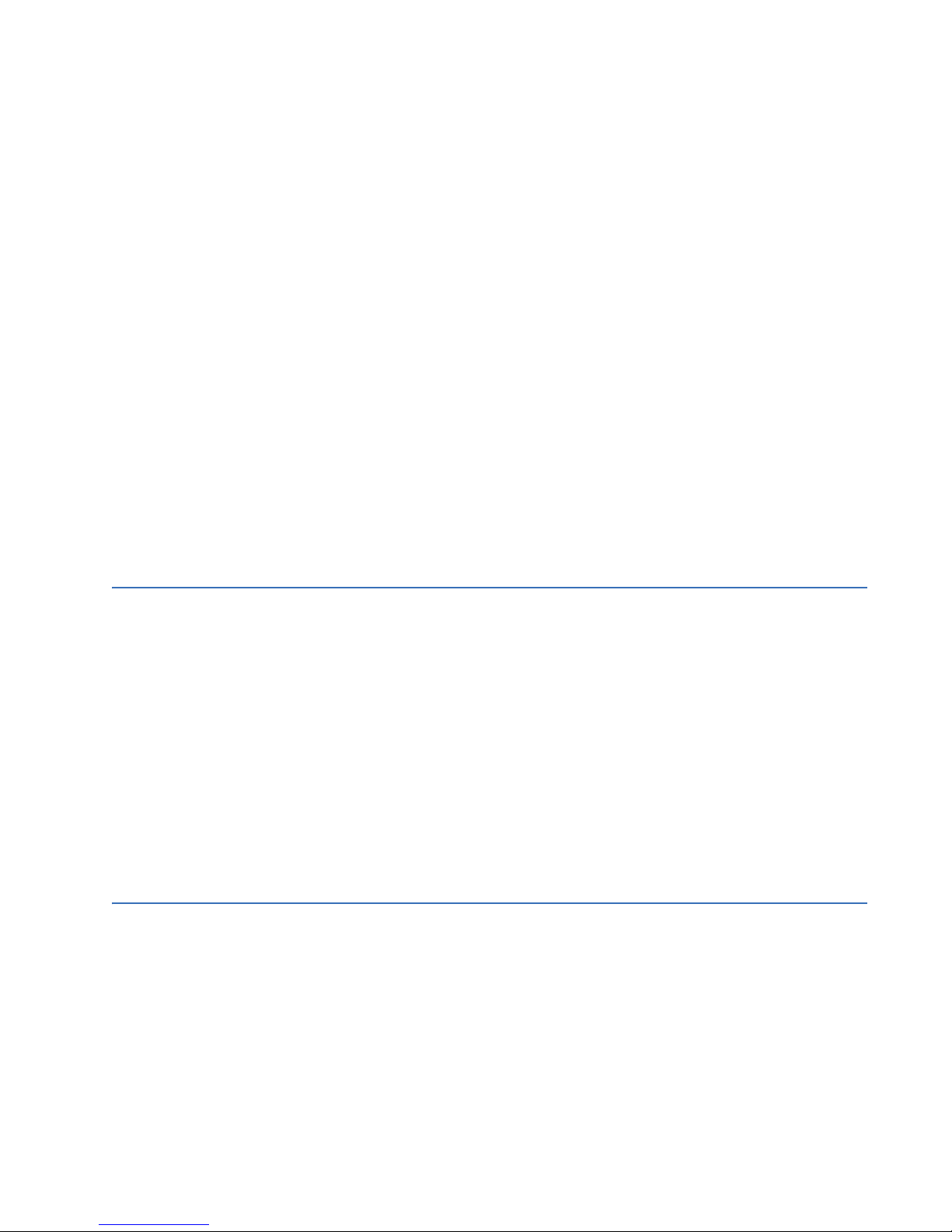

1.2 Wye Connection

The wye connection is so called because when you look at the phase relationships and

the winding relationships between the phases it looks like a Y. Figure 1.1 depicts the

winding relationships for a wye-connected service. In a wye service the neutral (or

center point of the wye) is typically grounded. This leads to common voltages of 208/

120 and 480/277 (where the first number represents the phase-to-phase voltage and

the second number represents the phase-to-ground voltage).

EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL 1–1

Page 8

WYE CONNECTION CHAPTER 1: THREE-PHASE POWER MEASUREMENT

Phase 2

V

A

V

B

V

C

Phase 3

Figure 1-1: Three-phase Wye Winding

The three voltages are separated by 120o electrically. Under balanced load conditions

the currents are also separated by 120

conditions can cause the currents to depart from the ideal 120

phase voltages and currents are usually represented with a phasor diagram. A phasor

diagram for the typical connected voltages and currents is shown in Figure 1.2.

N

Phase 1

o

. However, unbalanced loads and other

o

separation. Three-

The phasor diagram shows the 120o angular separation between the phase voltages.

The phase-to-phase voltage in a balanced three-phase wye system is 1.732 times the

phase-to-neutral voltage. The center point of the wye is tied together and is typically

grounded. Table 1.1 shows the common voltages used in the United States for wyeconnected systems.

1–2 EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL

Figure 1-2: Phasor Diagram Showing Three-phase Voltages and Currents

Table 1.1: Common Phase Voltages on Wye Services

Phase to Ground Voltage Phase to Phase Voltage

120 volts 208 volts

277 volts 480 volts

2,400 volts 4,160 volts

7,200 volts 12,470 volts

Page 9

CHAPTER 1: THREE-PHASE POWER MEASUREMENT DELTA CONNECTION

V

A

V

B

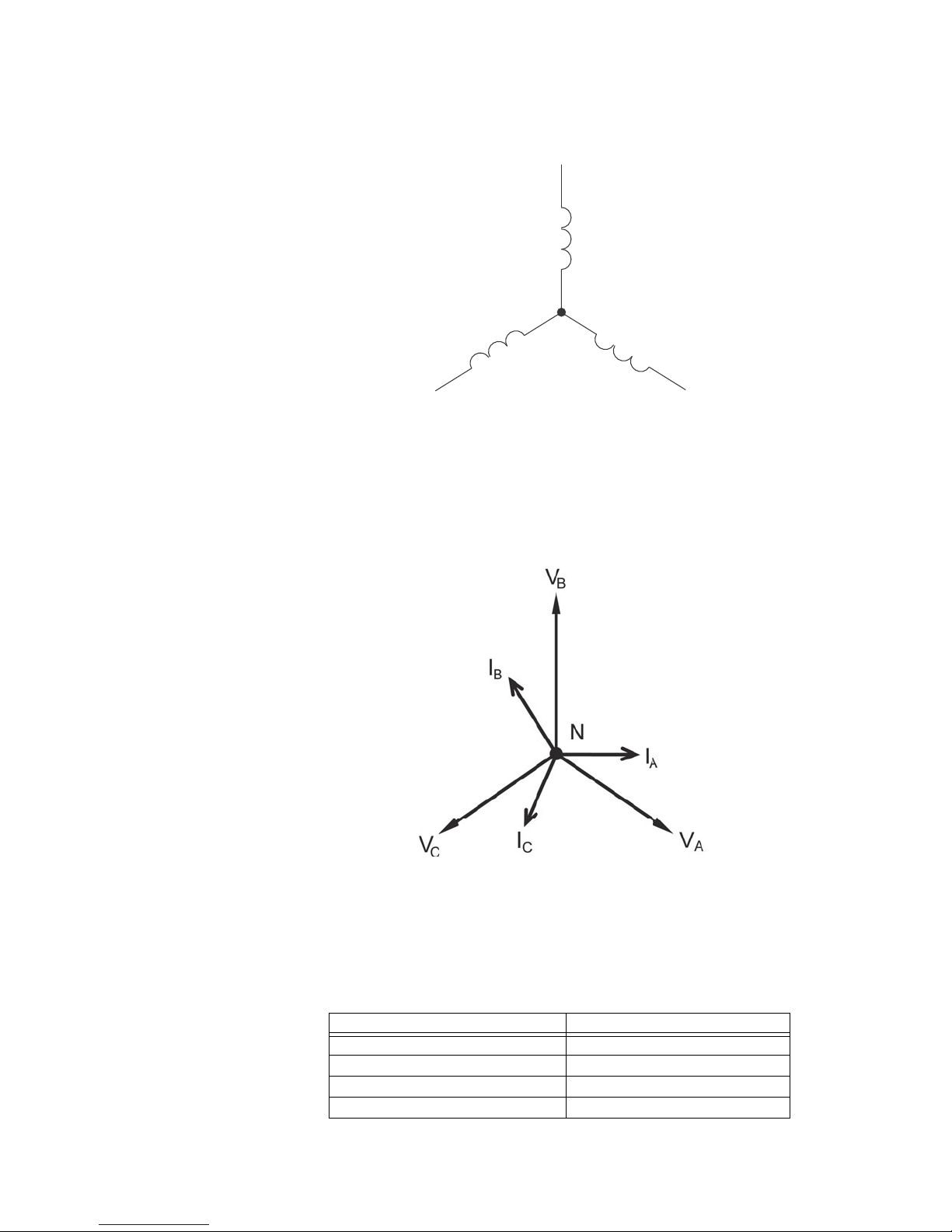

Table 1.1: Common Phase Voltages on Wye Services

Phase to Ground Voltage Phase to Phase Voltage

7,620 volts 13,200 volts

Usually a wye-connected service will have four wires: three wires for the phases and

one for the neutral. The three-phase wires connect to the three phases (as shown in

Figure 1.1). The neutral wire is typically tied to the ground or center point of the wye.

In many industrial applications the facility will be fed with a four-wire wye service but

only three wires will be run to individual loads. The load is then often referred to as a

delta-connected load but the service to the facility is still a wye service; it contains

four wires if you trace the circuit back to its source (usually a transformer). In this type

of connection the phase to ground voltage will be the phase-to-ground voltage

indicated in Table 1, even though a neutral or ground wire is not physically present at

the load. The transformer is the best place to determine the circuit connection type

because this is a location where the voltage reference to ground can be conclusively

identified.

1.3 Delta Connection

Delta-connected services may be fed with either three wires or four wires. In a threephase delta service the load windings are connected from phase-to-phase rather

than from phase-to-ground. Figure 1.3 shows the physical load connections for a

delta service.

V

C

Phase 2

Phase 1

Figure 1-3: Three-phase Delta Winding Relationship

In this example of a delta service, three wires will transmit the power to the load. In a

true delta service, the phase-to-ground voltage will usually not be balanced because

the ground is not at the center of the delta.

Phase 3

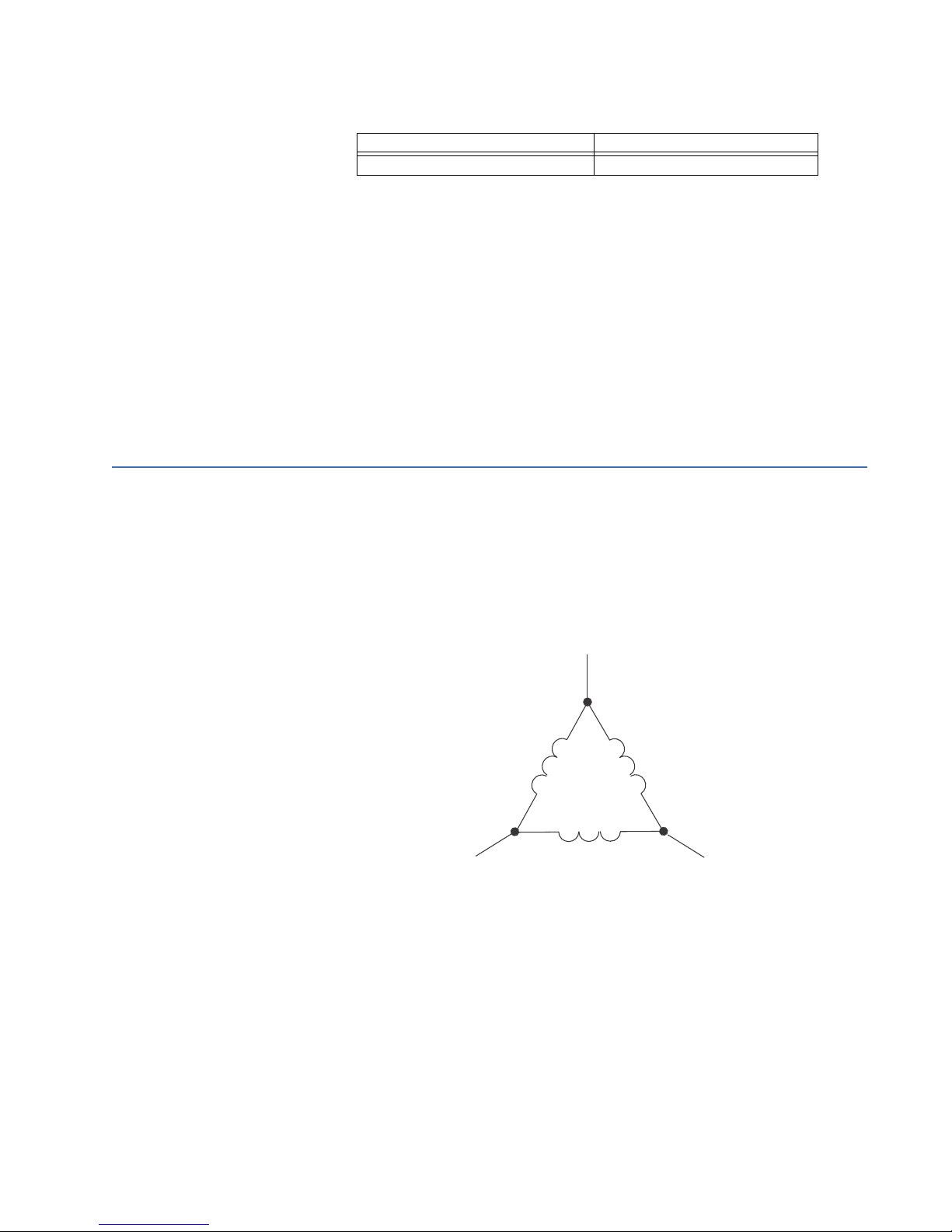

Figure 1.4 shows the phasor relationships between voltage and current on a threephase delta circuit.

In many delta services, one corner of the delta is grounded. This means the phase to

ground voltage will be zero for one phase and will be full phase-to-phase voltage for

the other two phases. This is done for protective purposes.

EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL 1–3

Page 10

BLONDEL’S THEOREM AND THREE PHASE MEASUREMENT CHAPTER 1: THREE-PHASE POWER MEASUREMENT

V

A

V

BC

Figure 1-4: Phasor Diagram, Three-Phase Voltages and Currents, Delta-Connected

Another common delta connection is the four-wire, grounded delta used for lighting

loads. In this connection the center point of one winding is grounded. On a 120/240

volt, four-wire, grounded delta service the phase-to-ground voltage would be 120

volts on two phases and 208 volts on the third phase. Figure 1.5 shows the phasor

diagram for the voltages in a three-phase, four-wire delta system.

V

BC

N

V

I

C

I

B

V

AB

C

V

CA

I

A

V

CA

Figure 1-5: Phasor Diagram Showing Three-phase Four-Wire Delta-Connected System

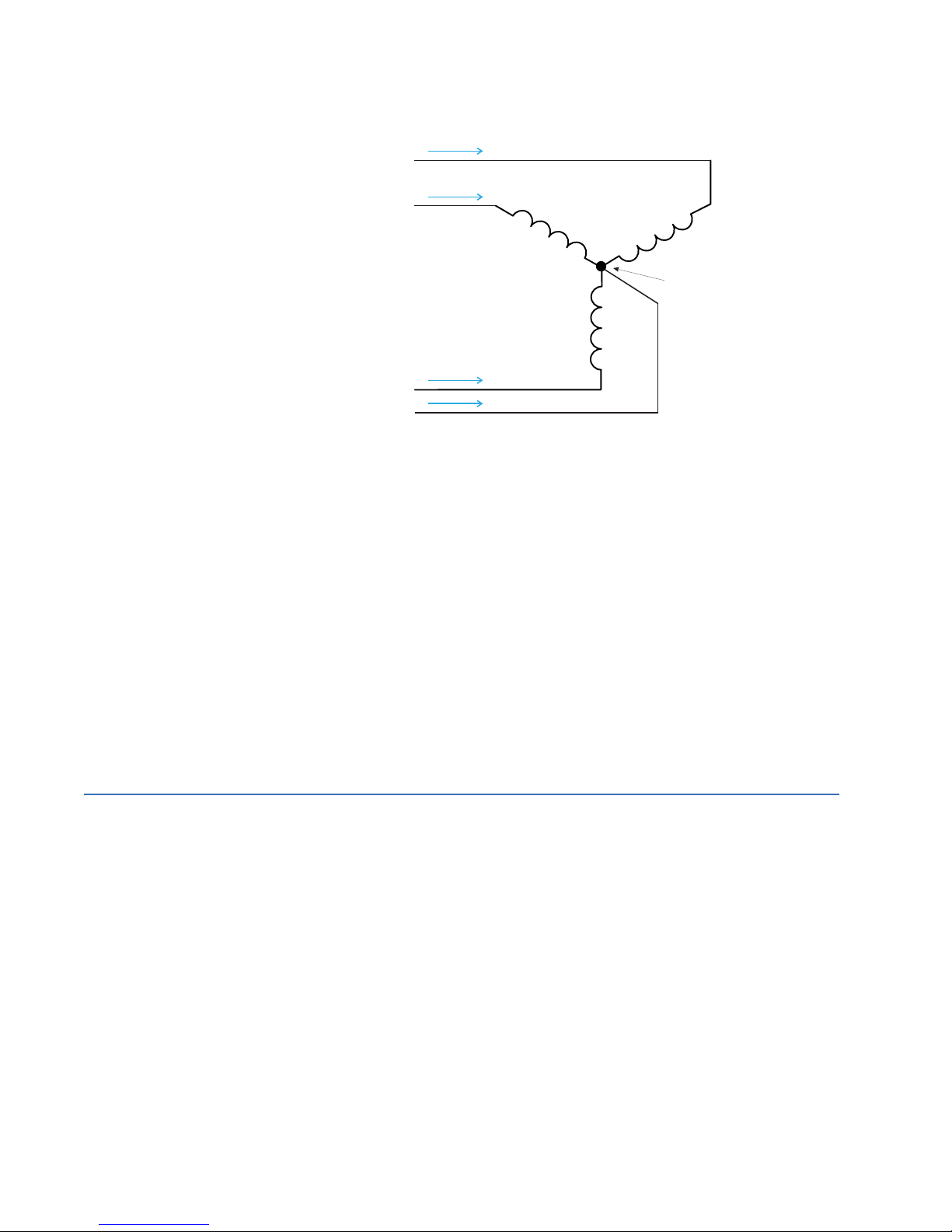

1.4 Blondel’s Theorem and Three Phase Measurement

1–4 EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL

In 1893 an engineer and mathematician named Andre E. Blondel set forth the first

scientific basis for polyphase metering. His theorem states:

If energy is supplied to any system of conductors through N wires, the total power in

the system is given by the algebraic sum of the readings of N wattmeters so arranged

that each of the N wires contains one current coil, the corresponding potential coil

being connected between that wire and some common point. If this common point is

on one of the N wires, the measurement may be made by the use of N-1 Wattmeters.

V

V

AB

B

Page 11

CHAPTER 1: THREE-PHASE POWER MEASUREMENT BLONDEL’S THEOREM AND THREE PHASE MEASUREMENT

The theorem may be stated more simply, in modern language:

In a system of N conductors, N-1 meter elements will measure the power or energy

taken provided that all the potential coils have a common tie to the conductor in

which there is no current coil.

Three-phase power measurement is accomplished by measuring the three individual

phases and adding them together to obtain the total three phase value. In older

analog meters, this measurement was accomplished using up to three separate

elements. Each element combined the single-phase voltage and current to produce a

torque on the meter disk. All three elements were arranged around the disk so that the

disk was subjected to the combined torque of the three elements. As a result the disk

would turn at a higher speed and register power supplied by each of the three wires.

According to Blondel's Theorem, it was possible to reduce the number of elements

under certain conditions. For example, a three-phase, three-wire delta system could

be correctly measured with two elements (two potential coils and two current coils) if

the potential coils were connected between the three phases with one phase in

common.

In a three-phase, four-wire wye system it is necessary to use three elements. Three

voltage coils are connected between the three phases and the common neutral

conductor. A current coil is required in each of the three phases.

In modern digital meters, Blondel's Theorem is still applied to obtain proper

metering. The difference in modern meters is that the digital meter measures each

phase voltage and current and calculates the single-phase power for each phase. The

meter then sums the three phase powers to a single three-phase reading.

Some digital meters measure the individual phase power values one phase at a time.

This means the meter samples the voltage and current on one phase and calculates a

power value. Then it samples the second phase and calculates the power for the

second phase. Finally, it samples the third phase and calculates that phase power.

After sampling all three phases, the meter adds the three readings to create the

equivalent three-phase power value. Using mathematical averaging techniques, this

method can derive a quite accurate measurement of three-phase power.

More advanced meters actually sample all three phases of voltage and current

simultaneously and calculate the individual phase and three-phase power values. The

advantage of simultaneous sampling is the reduction of error introduced due to the

difference in time when the samples were taken.

EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL 1–5

Page 12

POWER, ENERGY AND DEMAND CHAPTER 1: THREE-PHASE POWER MEASUREMENT

Phase B

Phase C

Phase A

A

B

C

N

Node "n"

Figure 1-6: Three-Phase Wye Load Illustrating Kirchoff’s Law and Blondel’s Theorem

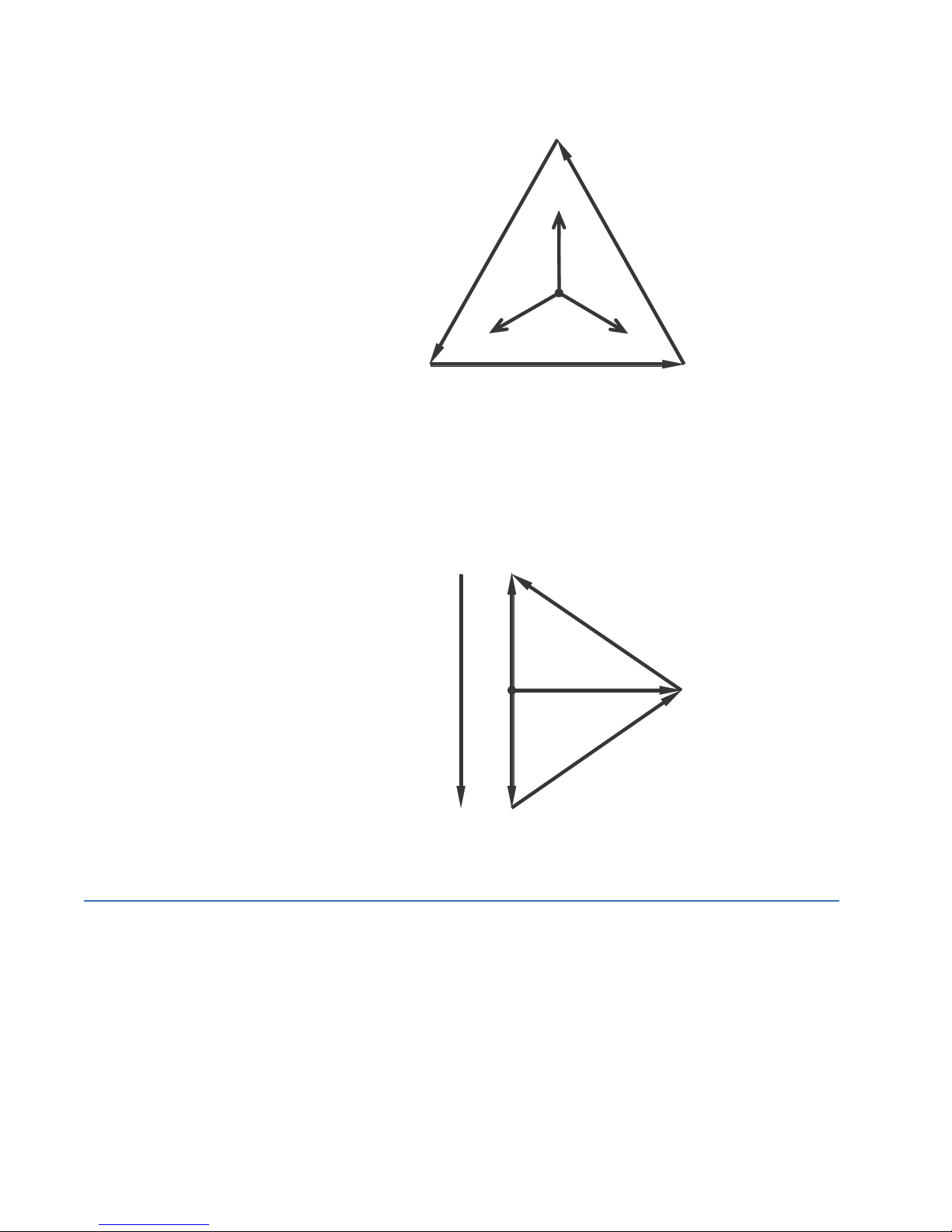

Blondel's Theorem is a derivation that results from Kirchoff's Law. Kirchoff's Law states

that the sum of the currents into a node is zero. Another way of stating the same thing

is that the current into a node (connection point) must equal the current out of the

node. The law can be applied to measuring three-phase loads. Figure 1.6 shows a

typical connection of a three-phase load applied to a three-phase, four-wire service.

Kirchoff's Law holds that the sum of currents A, B, C and N must equal zero or that the

sum of currents into Node "n" must equal zero.

If we measure the currents in wires A, B and C, we then know the current in wire N by

Kirchoff's Law and it is not necessary to measure it. This fact leads us to the

conclusion of Blondel's Theorem- that we only need to measure the power in three of

the four wires if they are connected by a common node. In the circuit of Figure 1.6 we

must measure the power flow in three wires. This will require three voltage coils and

three current coils (a three-element meter). Similar figures and conclusions could be

reached for other circuit configurations involving Delta-connected loads.

1.5 Power, Energy and Demand

It is quite common to exchange power, energy and demand without differentiating

between the three. Because this practice can lead to confusion, the differences

between these three measurements will be discussed.

Power is an instantaneous reading. The power reading provided by a meter is the

present flow of watts. Power is measured immediately just like current. In many digital

meters, the power value is actually measured and calculated over a one second

interval because it takes some amount of time to calculate the RMS values of voltage

and current. But this time interval is kept small to preserve the instantaneous nature

of power.

Energy is always based on some time increment; it is the integration of power over a

defined time increment. Energy is an important value because almost all electric bills

are based, in part, on the amount of energy used.

1–6 EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL

Page 13

CHAPTER 1: THREE-PHASE POWER MEASUREMENT POWER, ENERGY AND DEMAND

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

Time (minutes)

sttawolik

Typically, electrical energy is measured in units of kilowatt-hours (kWh). A kilowatthour represents a constant load of one thousand watts (one kilowatt) for one hour.

Stated another way, if the power delivered (instantaneous watts) is measured as 1,000

watts and the load was served for a one hour time interval then the load would have

absorbed one kilowatt-hour of energy. A different load may have a constant power

requirement of 4,000 watts. If the load were served for one hour it would absorb four

kWh. If the load were served for 15 minutes it would absorb ¼ of that total or one

kWh.

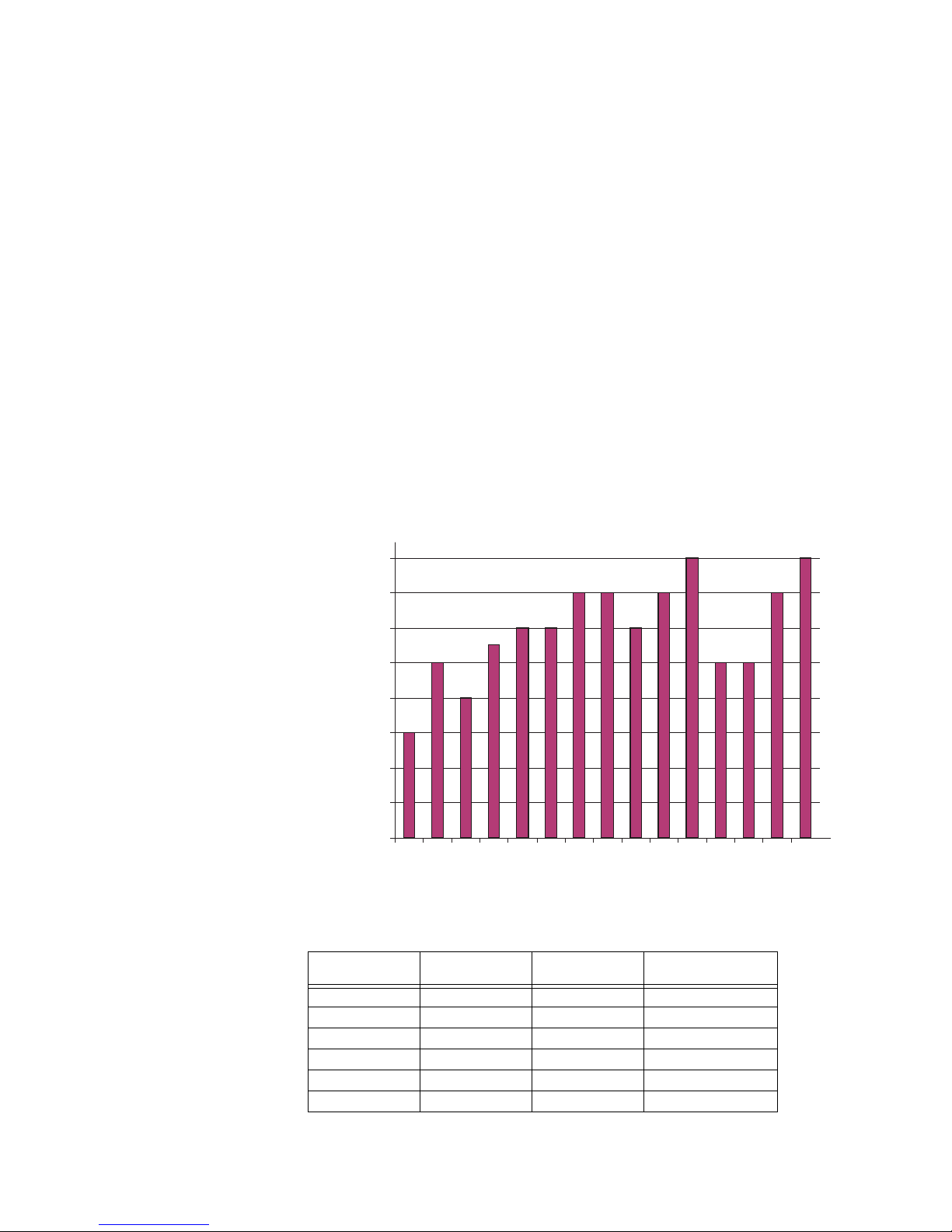

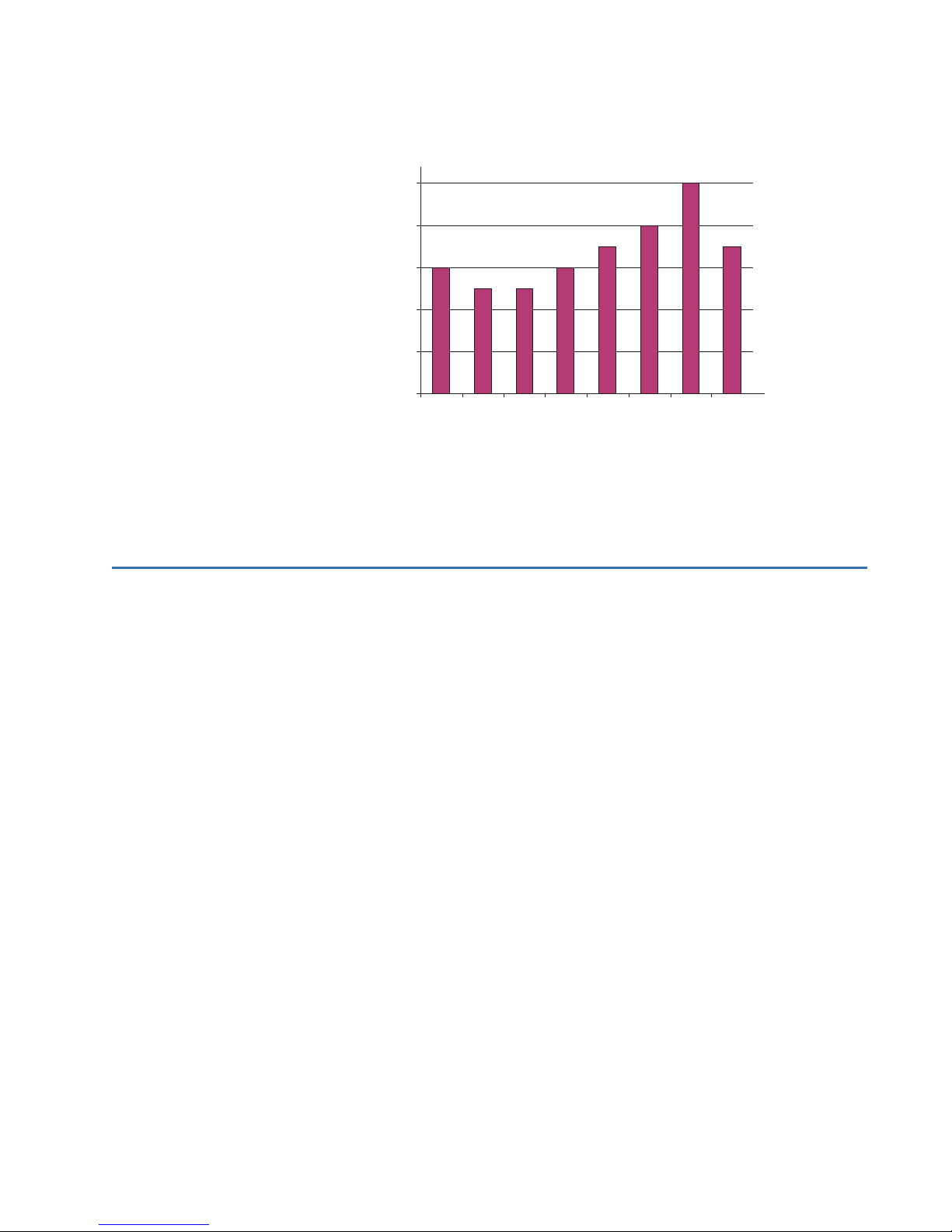

Figure 1.7 shows a graph of power and the resulting energy that would be transmitted

as a result of the illustrated power values. For this illustration, it is assumed that the

power level is held constant for each minute when a measurement is taken. Each bar

in the graph will represent the power load for the one-minute increment of time. In

real life the power value moves almost constantly.

The data from Figure 1.7 is reproduced in Table 1.2 to illustrate the calculation of

energy. Since the time increment of the measurement is one minute and since we

specified that the load is constant over that minute, we can convert the power

reading to an equivalent consumed energy reading by multiplying the power reading

times 1/60 (converting the time base from minutes to hours).

Time Interval

EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL 1–7

(minute)

Figure 1-7: Power Use over Time

Table 1.2: Power and Energy Relationship over Time

Power (kW) Energy (kWh) Accumulated Energy

(kWh)

1300.500.50

2500.831.33

3400.672.00

4550.922.92

5601.003.92

6601.004.92

Page 14

POWER, ENERGY AND DEMAND CHAPTER 1: THREE-PHASE POWER MEASUREMENT

Table 1.2: Power and Energy Relationship over Time

Time Interval

(minute)

7701.176.09

8701.177.26

9601.008.26

10 70 1.17 9.43

11 80 1.33 10.76

12 50 0.83 12.42

13 50 0.83 12.42

14 70 1.17 13.59

15 80 1.33 14.92

Power (kW) Energy (kWh) Accumulated Energy

(kWh)

As in Table 1.2, the accumulated energy for the power load profile of Figure 1.7 is

14.92 kWh.

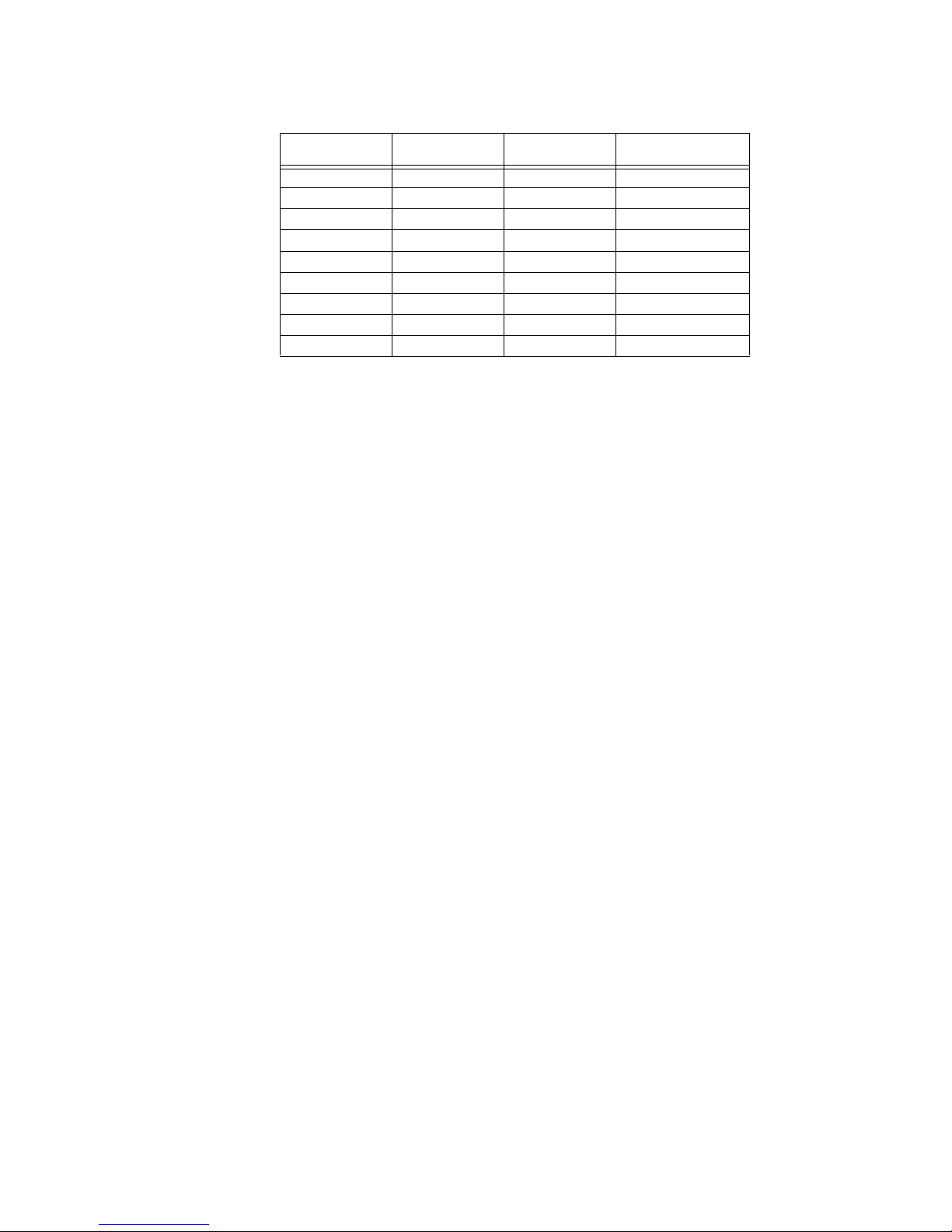

Demand is also a time-based value. The demand is the average rate of energy use

over time. The actual label for demand is kilowatt-hours/hour but this is normally

reduced to kilowatts. This makes it easy to confuse demand with power, but demand

is not an instantaneous value. To calculate demand it is necessary to accumulate the

energy readings (as illustrated in Figure 1.7) and adjust the energy reading to an

hourly value that constitutes the demand.

In the example, the accumulated energy is 14.92 kWh. But this measurement was

made over a 15-minute interval. To convert the reading to a demand value, it must be

normalized to a 60-minute interval. If the pattern were repeated for an additional

three 15-minute intervals the total energy would be four times the measured value or

59.68 kWh. The same process is applied to calculate the 15-minute demand value.

The demand value associated with the example load is 59.68 kWh/hr or 59.68 kWd.

Note that the peak instantaneous value of power is 80 kW, significantly more than the

demand value.

Figure 1.8 shows another example of energy and demand. In this case, each bar

represents the energy consumed in a 15-minute interval. The energy use in each

interval typically falls between 50 and 70 kWh. However, during two intervals the

energy rises sharply and peaks at 100 kWh in interval number 7. This peak of usage

will result in setting a high demand reading. For each interval shown the demand

value would be four times the indicated energy reading. So interval 1 would have an

associated demand of 240 kWh/hr. Interval 7 will have a demand value of 400 kWh/

hr. In the data shown, this is the peak demand value and would be the number that

would set the demand charge on the utility bill.

1–8 EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL

Page 15

CHAPTER 1: THREE-PHASE POWER MEASUREMENT REACTIVE ENERGY AND POWER FACTOR

0

20

40

60

80

100

12345678

Intervals (15 mins.)

sruoh-ttawolik

Figure 1-8: Energy Use and Demand

As can be seen from this example, it is important to recognize the relationships

between power, energy and demand in order to control loads effectively or to monitor

use correctly.

1.6 Reactive Energy and Power Factor

The real power and energy measurements discussed in the previous section relate to

the quantities that are most used in electrical systems. But it is often not sufficient to

only measure real power and energy. Reactive power is a critical component of the

total power picture because almost all real-life applications have an impact on

reactive power. Reactive power and power factor concepts relate to both load and

generation applications. However, this discussion will be limited to analysis of reactive

power and power factor as they relate to loads. To simplify the discussion, generation

will not be considered.

Real power (and energy) is the component of power that is the combination of the

voltage and the value of corresponding current that is directly in phase with the

voltage. However, in actual practice the total current is almost never in phase with the

voltage. Since the current is not in phase with the voltage, it is necessary to consider

both the inphase component and the component that is at quadrature (angularly

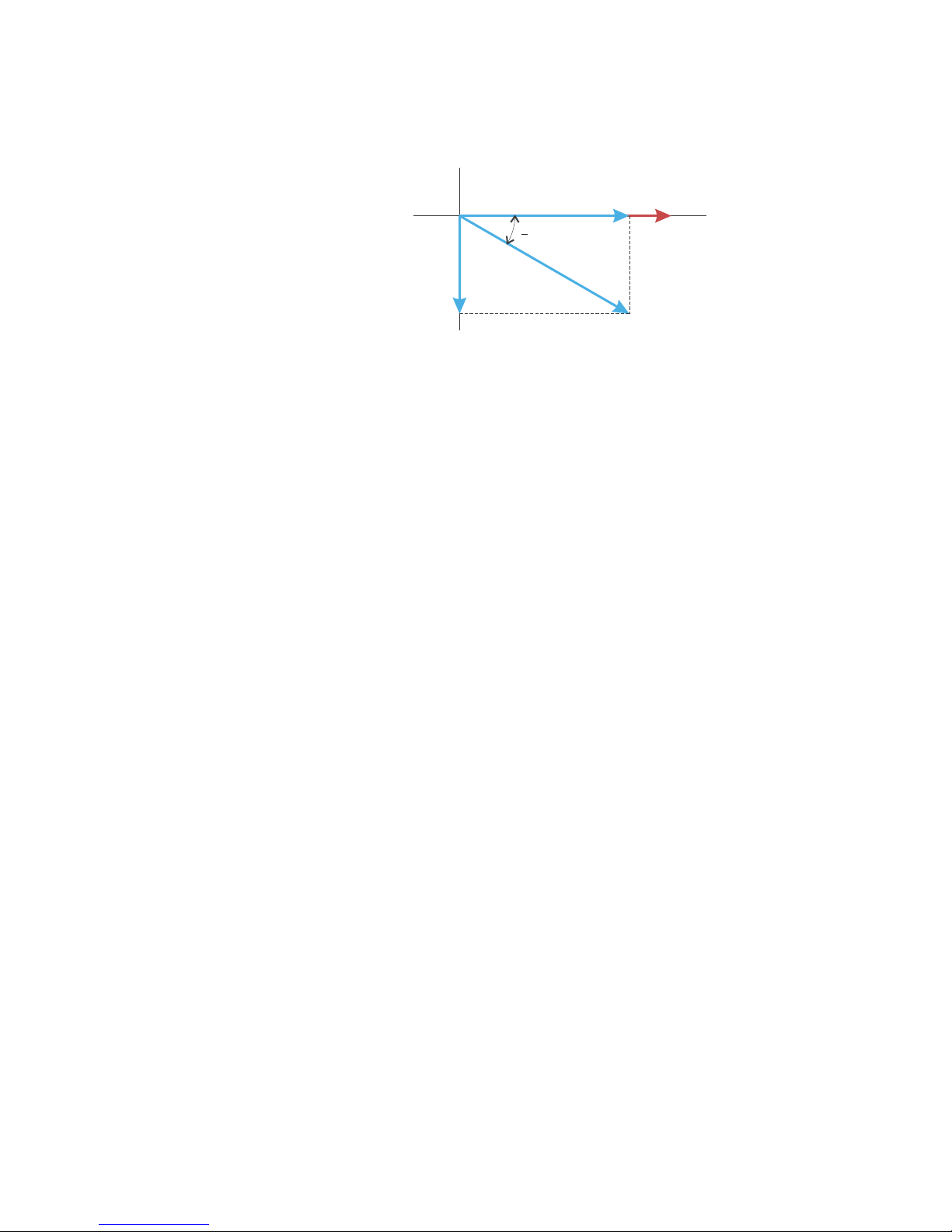

rotated 90o or perpendicular) to the voltage. Figure 1.9 shows a single-phase voltage

and current and breaks the current into its in-phase and quadrature components.

EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL 1–9

Page 16

REACTIVE ENERGY AND POWER FACTOR CHAPTER 1: THREE-PHASE POWER MEASUREMENT

V

I

I

R

I

X

0

Figure 1-9: Voltage and Complex Current

The voltage (V) and the total current (I) can be combined to calculate the apparent

power or VA. The voltage and the in-phase current (IR) are combined to produce the

real power or watts. The voltage and the quadrature current (IX) are combined to

calculate the reactive power.

The quadrature current may be lagging the voltage (as shown in Figure 1.9) or it may

lead the voltage. When the quadrature current lags the voltage the load is requiring

both real power (watts) and reactive power (VARs). When the quadrature current leads

the voltage the load is requiring real power (watts) but is delivering reactive power

(VARs) back into the system; that is VARs are flowing in the opposite direction of the

real power flow.

Reactive power (VARs) is required in all power systems. Any equipment that uses

magnetization to operate requires VARs. Usually the magnitude of VARs is relatively

low compared to the real power quantities. Utilities have an interest in maintaining

VAR requirements at the customer to a low value in order to maximize the return on

plant invested to deliver energy. When lines are carrying VARs, they cannot carry as

many watts. So keeping the VAR content low allows a line to carry its full capacity of

watts. In order to encourage customers to keep VAR requirements low, some utilities

impose a penalty if the VAR content of the load rises above a specified value.

A common method of measuring reactive power requirements is power factor. Power

factor can be defined in two different ways. The more common method of calculating

power factor is the ratio of the real power to the apparent power. This relationship is

expressed in the following formula:

Total PF = real power / apparent power = watts/VA

This formula calculates a power factor quantity known as Total Power Factor. It is

called Total PF because it is based on the ratios of the power delivered. The delivered

power quantities will include the impacts of any existing harmonic content. If the

voltage or current includes high levels of harmonic distortion the power values will be

affected. By calculating power factor from the power values, the power factor will

include the impact of harmonic distortion. In many cases this is the preferred method

of calculation because the entire impact of the actual voltage and current are

included.

1–10 EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL

Page 17

CHAPTER 1: THREE-PHASE POWER MEASUREMENT HARMONIC DISTORTION

Displacement PF θcos=

Time

Amps

– 1000

– 500

0

500

1000

A second type of power factor is Displacement Power Factor. Displacement PF is

based on the angular relationship between the voltage and current. Displacement

power factor does not consider the magnitudes of voltage, current or power. It is solely

based on the phase angle differences. As a result, it does not include the impact of

harmonic distortion. Displacement power factor is calculated using the following

equation:

where

θ is the angle between the voltage and the current (see Fig. 1.9).

In applications where the voltage and current are not distorted, the Total Power

Factor will equal the Displacement Power Factor. But if harmonic distortion is present,

the two power factors will not be equal.

1.7 Harmonic Distortion

Harmonic distortion is primarily the result of high concentrations of non-linear loads.

Devices such as computer power supplies, variable speed drives and fluorescent light

ballasts make current demands that do not match the sinusoidal waveform of AC

electricity. As a result, the current waveform feeding these loads is periodic but not

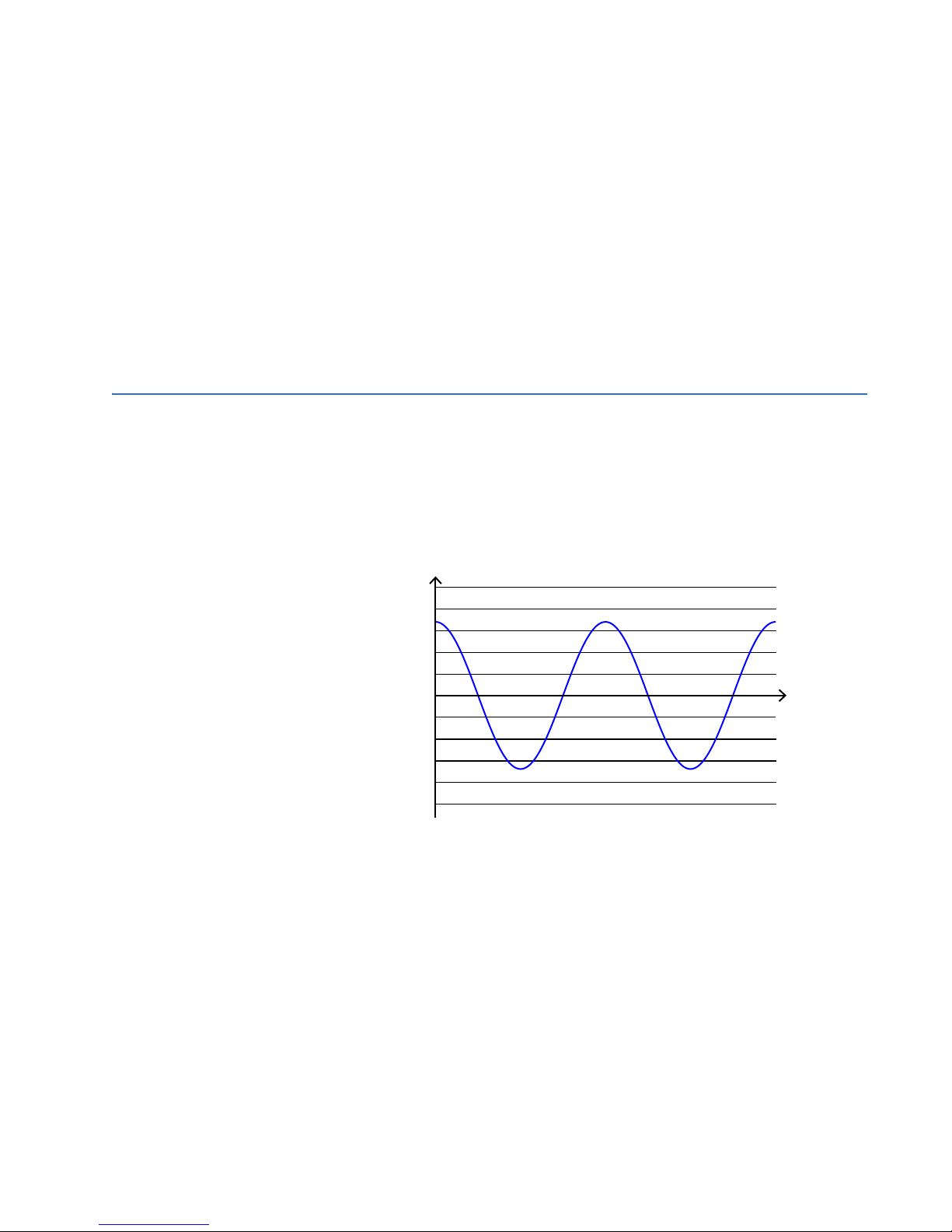

sinusoidal. Figure 1.10 shows a normal, sinusoidal current waveform. This example

has no distortion.

Figure 1.11 shows a current waveform with a slight amount of harmonic distortion.

The waveform is still periodic and is fluctuating at the normal 60 Hz frequency.

However, the waveform is not a smooth sinusoidal form as seen in Figure 1.10.

EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL 1–11

Figure 1-10: Nondistorted Current Waveform

Page 18

HARMONIC DISTORTION CHAPTER 1: THREE-PHASE POWER MEASUREMENT

–1000

–500

0

500

1000

t

)s

p

m

a(

tner

r

u

C

a

2a

–1500

1500

Time

Amps

3rd harmonic

5th harmonic

7th harmonic

Total

fundamental

– 500

0

500

1000

Figure 1-11: Distorted Current Waveform

The distortion observed in Figure 1.11 can be modeled as the sum of several

sinusoidal waveforms of frequencies that are multiples of the fundamental 60 Hz

frequency. This modeling is performed by mathematically disassembling the distorted

waveform into a collection of higher frequency waveforms.

These higher frequency waveforms are referred to as harmonics. Figure 1.12 shows

the content of the harmonic frequencies that make up the distortion portion of the

waveform in Figure 1.11.

The waveforms shown in Figure 1.12 are not smoothed but do provide an indication of

1–12 EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL

the impact of combining multiple harmonic frequencies together.

When harmonics are present it is important to remember that these quantities are

operating at higher frequencies. Therefore, they do not always respond in the same

manner as 60 Hz values.

Figure 1-12: Waveforms of the Harmonics

Page 19

CHAPTER 1: THREE-PHASE POWER MEASUREMENT POWER QUALITY

Inductive and capacitive impedance are present in all power systems. We are

accustomed to thinking about these impedances as they perform at 60 Hz. However,

these impedances are subject to frequency variation.

XL = jwL and

XC = 1/jwC

At 60 Hz, w = 377; but at 300 Hz (5th harmonic) w = 1,885. As frequency changes

impedance changes and system impedance characteristics that are normal at 60 Hz

may behave entirely differently in the presence of higher order harmonic waveforms.

Traditionally, the most common harmonics have been the low order, odd frequencies,

such as the 3rd, 5th, 7th, and 9th. However newer, non-linear loads are introducing

significant quantities of higher order harmonics.

Since much voltage monitoring and almost all current monitoring is performed using

instrument transformers, the higher order harmonics are often not visible. Instrument

transformers are designed to pass 60 Hz quantities with high accuracy. These devices,

when designed for accuracy at low frequency, do not pass high frequencies with high

accuracy; at frequencies above about 1200 Hz they pass almost no information. So

when instrument transformers are used, they effectively filter out higher frequency

harmonic distortion making it impossible to see.

1.8 Power Quality

However, when monitors can be connected directly to the measured circuit (such as

direct connection to a 480 volt bus) the user may often see higher order harmonic

distortion. An important rule in any harmonics study is to evaluate the type of

equipment and connections before drawing a conclusion. Not being able to see

harmonic distortion is not the same as not having harmonic distortion.

It is common in advanced meters to perform a function commonly referred to as

waveform capture. Waveform capture is the ability of a meter to capture a present

picture of the voltage or current waveform for viewing and harmonic analysis.

Typically a waveform capture will be one or two cycles in duration and can be viewed

as the actual waveform, as a spectral view of the harmonic content, or a tabular view

showing the magnitude and phase shift of each harmonic value. Data collected with

waveform capture is typically not saved to memory. Waveform capture is a real-time

data collection event.

Waveform capture should not be confused with waveform recording that is used to

record multiple cycles of all voltage and current waveforms in response to a transient

condition.

Power quality can mean several different things. The terms “power quality” and

“power quality problem” have been applied to all types of conditions. A simple

definition of “power quality problem” is any voltage, current or frequency deviation

that results in mis-operation or failure of customer equipment or systems. The causes

of power quality problems vary widely and may originate in the customer equipment,

in an adjacent customer facility or with the utility.

EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL 1–13

Page 20

POWER QUALITY CHAPTER 1: THREE-PHASE POWER MEASUREMENT

In his book Power Quality Primer, Barry Kennedy provided information on different

types of power quality problems. Some of that information is summarized in Table 1.3.

Table 1.3: Typical Power Quality Problems and Sources

Cause Disturbance Type Source

Impulse transient Transient voltage disturbance,

sub-cycle duration

Oscillatory

transient with decay

Sag/swell RMS voltage, multiple cycle

Interruptions RMS voltage, multiple

Under voltage/over

voltage

Voltage flicker RMS voltage, steady state,

Harmonic distortion Steady state current or voltage,

Transient voltage, sub-cycle

duration

duration

seconds or longer duration

RMS voltage, steady state, multiple

seconds or longer

duration

repetitive condition

long-term duration

Lightning

Electrostatic discharge

Load switching

Capacitor switching

Line/cable switching

Capacitor switching

Load switching

Remote system faults

System protection

Circuit breakers

Fuses

Maintenance

Motor starting

Load variations

Load dropping

Intermittent loads

Motor starting

Arc furnaces

Non-linear loads

System resonance

It is often assumed that power quality problems originate with the utility. While it is

true that power quality problems can originate with the utility system, many problems

originate with customer equipment. Customer-caused problems may manifest

themselves inside the customer location or they may be transported by the utility

system to another adjacent customer. Often, equipment that is sensitive to power

quality problems may in fact also be the cause of the problem.

If a power quality problem is suspected, it is generally wise to consult a power quality

professional for assistance in defining the cause and possible solutions to the

problem.

1–14 EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL

Page 21

GE

Grid Solutions

Note

EPM 2200 Power Meter

Chapter 2: Overview and

Specifications

Overview and Specifications

In European Union member state countries, this meter is NOT certified for revenue

metering. See the Safety Precautions section for meter certification details.

2.1 Hardware Overview

The EPM 2200 multifunction power meters is designed for use with and/or within Industrial

Control Panels in electrical substations, panel boards, and as a power meter for OEM

equipment. EPM 2200 meters provide multifunction measurement of all electrical

parameters.

The EPM 2200 monitor is a 0.5% class electrical panel meter. Using bright and large 0.56”

LED displays, it is designed to be used in electrical panels and switchgear. The meter has a

unique anti-dither algorithm to improve reading stability. The EPM 2200 meter uses highspeed DSP technology with high-resolution A/D conversion to provide stable and reliable

measurements. UL 61010-1 does not address performance criteria for revenue generating

watt-hour meters for use in metering of utilities and/or communicating directly with

utilities, or use within a substation. Use in revenue metering, communicating with utilities,

and use in substations was verified according to the ANSI and IEC standards listed in the

Compliance Section (2.3).

The EPM 2200 meter is a meter and transducer in one compact unit. Featuring an optional

RS485 port, it can be programmed using the faceplate of the meter or through software.

ANSI or DIN mounting may be used.

EPM 2200 meter features that are detailed in this manual are as follows:

• 0.5% Class Accuracy

• Multifunction Measurement including Voltage, Current, Power, Frequency, Energy, etc.

• Percentage of Load Bar for Analog Meter Perception

• Easy to Use Faceplate Programming

• One Communication Option:

• RS485 Modbus/KYZ output (Option S)

EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL 2–1

Page 22

HARDWARE OVERVIEW CHAPTER 2: OVERVIEW AND SPECIFICATIONS

• BACnet MS/TP Serial Multifunction Meter with Modbus TCP/IP Internet (Option B)

2.1.1 Voltage and Current Inputs

Universal Voltage Inputs

Voltage Inputs allow measurement to 416 Volts Line-to-Neutral and 721 Volts Line-to-Line.

One unit will perform to specification when directly connected to 69 Volt, 120 Volt, 230

Volt, 277 Volt, 277 Volt and 347 Volt power systems.

Current Inputs

The EPM 2200 meter Current Inputs use a unique dual input method:

Method 1: CT Pass Through

The CT passes directly through the meter without any physical termination on the meter.

This insures that the meter cannot be a point of failure on the CT circuit. This is preferable

for utility users when sharing relay class CTs.

Method 2: Current “Gills”

This unit additionally provides ultra-rugged Termination Pass Through Bars that allow CT

leads to be terminated on the meter. This, too, eliminates any possible point of failure at

the meter. This is a preferred technique for insuring that relay class CT integrity is not

compromised (the CT will not open in a fault condition).

2.1.2 Order Codes

The order codes for the EPM 2200 are indicated below.

Table 2–1: EPM 2200 Order Codes

PL2200

Base Unit PL2200

Enclosure Option ENC120 | | NEMA1 Rated - Indoor, Single Meter Enclosure, 120V

Software Option*

Communications Option

– * – * – *

|||

EPM 2200 Meter

ENC277 | | NEMA1 Rated - Indoor, Single Meter Enclosure, 277V

A1 |

B1 |

C1 |

BN |

Volts and Amps Meter

Volts, Amps, Power and Frequency Meter

Volts, Amps, Power, Frequency and Energy Counters Meter

BACnet Volts, Amps, Power, Frequency and Energy Counters

meter

RS485 Serial/KYZ Pulse

S

None

X

BACnet MS/TP Serial and Modbus TCP/IP Internet

B

* Software Options are only available with Communications Option S.

For example, to order an EPM 2200 to measure Volts, Amps, Power & Frequency, with

Modbus/KYZ output communications, use PL2200-XXXXXX-B1-S.

Accessories available for the EPM 2200 are indicated below.

2–2 EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL

Page 23

CHAPTER 2: OVERVIEW AND SPECIFICATIONS HARDWARE OVERVIEW

Table 2–2: EPM 2200 Accessory Order Codes

PL2200 –

DIN Bracket PL2200 –

*

ACC

–

*

–

EPM 2200 Meter DIN Mounting Bracket

DIN

2.1.3 Measured Values

The following table lists the measured values available in real time, average, maximum,

and minimum.

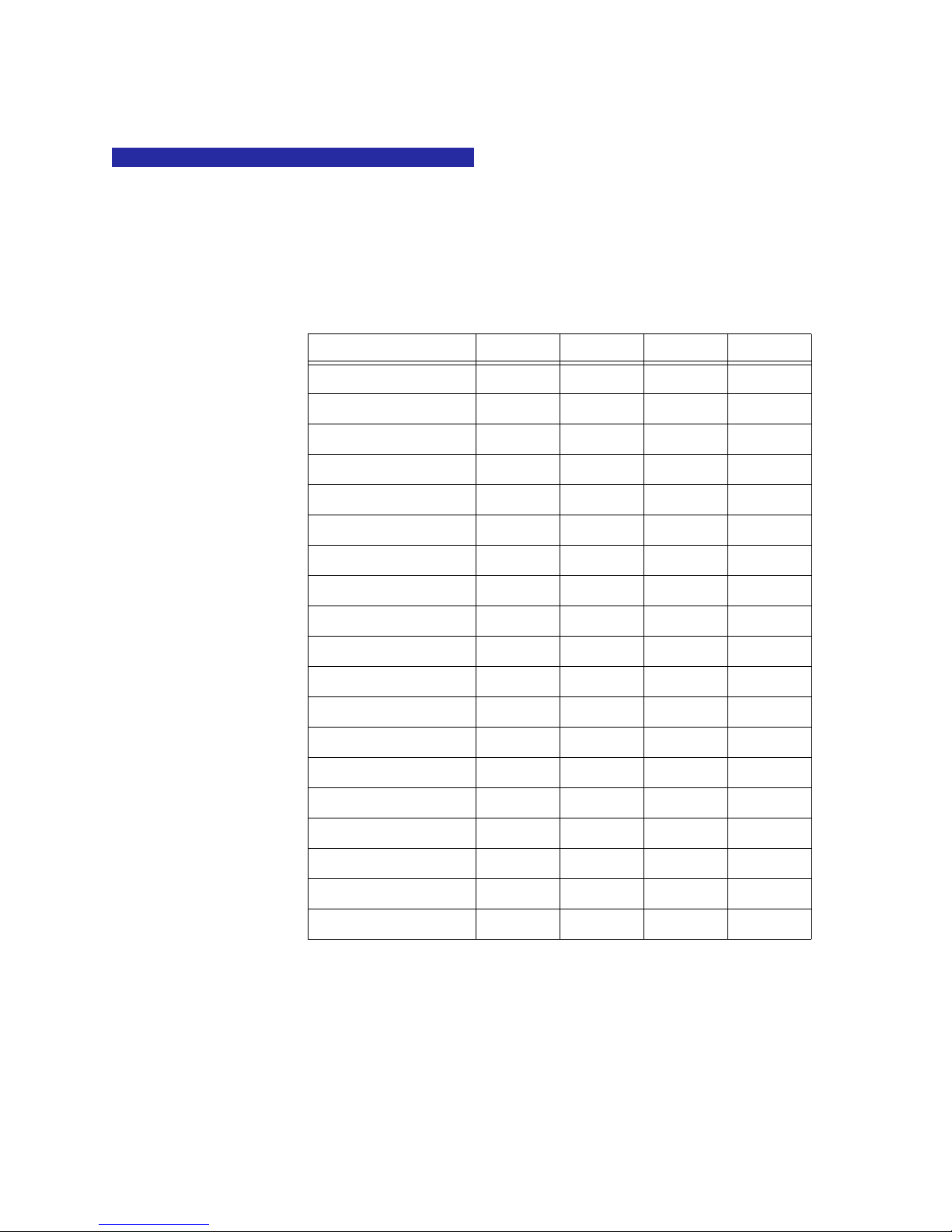

Table 2–3: EPM 2200 Measured Values

Measured Values Real Time Average Maximum Minimum

Voltage L-N XXX

Voltage L-L XXX

Current per phase XXXX

Current Neutral X

Watts XXXX

VARs XXXX

VA XXXX

Power Factor (PF) XXXX

Positive watt-hours X

Negative watt-hours X

Net watt-hours X

Positive VAR-hours X

Negative VAR-hours X

Net VAR-hours X

VA-hours X

Frequency XXX

Voltage angles X

Current angles X

% of load bar X

2.1.4 Utility Peak Demand

The EPM 2200 provides user-configured Block (fixed) window, or Rolling window demand.

This feature allows you to set up a customized demand profile. Block window demand is

demand used over a user-configured demand period (usually 5, 15, or 30 minutes). Rolling

EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL 2–3

Page 24

SPECIFICATIONS CHAPTER 2: OVERVIEW AND SPECIFICATIONS

window demand is a fixed window demand that moves for a user-specified subinterval

period. For example, a 15-minute demand using 3 subintervals and providing a new

demand reading every 5 minutes, based on the last 15 minutes.

Utility demand features can be used to calculate kW, kVAR, kVA and PF readings. All other

parameters offer maximum and minimum capability over the user-selectable averaging

period. Voltage provides an instantaneous maximum and minimum reading which

displays the highest surge and lowest sag seen by the meter.

2.2 Specifications

POWER SUPPLY

Range:.................................................Universal, (90 to 265) VAC @50/60Hz

Power consumption: ....................5 VA, 3.5 W

VOLTAGE INPUTS (MEASUREMENT CATEGORY III)

Range:.................................................Universal, Auto-ranging up to 416 V AC L-N, 721 V AC L-L

Supported hookups:.....................3-element Wye, 2.5-element Wye,

2-element Delta, 4-wire Delta

Input impedance: ..........................1 MOhm/phase

Burden:...............................................0.0144 VA/phase at 120 Volts

Pickup voltage:................................10 V AC

Connection: ......................................Screw terminal

Maximum input wire gauge: ...AWG #12 / 2.5 mm

Fault withstand:..............................Meets IEEE C37.90.1

Reading:.............................................Programmable full-scale to any PT ratio

CURRENT INPUTS

Class 10:.............................................5 A nominal, 10 A maximum

Burden:...............................................0.005 VA per phase maximum at 11 A

Pickup current:................................0.1% of nominal

Connections:....................................O or U lug;

Pass-through wire, 0.177" / 4.5 mm maximum diameter

Quick connect, 0.25" male tab

Fault Withstand (at 23°C):..........100 A / 10 seconds, 300 A / 3 seconds, 500 A / 1 second

Reading:.............................................Programmable full-scale to any CT ratio

ISOLATION

All Inputs and Outputs are galvanically isolated to 2500 V AC

ENVIRONMENTAL

Storage:..............................................–20 to 70°C

Operating: .........................................-20 to 70°C

Humidity:...........................................up to 95% RH, non-condensing

Faceplate rating:............................NEMA 12 (water resistant), mounting gasket included

METER ENCLOSURE ENVIRONMENTAL

Storage:..............................................–20 to 70°C

Operating: .........................................-10 to 50°C

Humidity:...........................................up to 95% RH, non-condensing

Faceplate rating:............................NEMA 1 (Indoor Use)

Pollution degree.............................II

Overvoltage Category.................III (this product is designed for indoor use only)

MEASUREMENT METHODS

Voltage and current: ....................True RMS

Power: .................................................Sampling at 400+ samples/cycle on all channels measured; readings

simultaneously

A/D conversion: ..............................6 simultaneous 24-bit analog-to-digital converters

2

2–4 EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL

Page 25

CHAPTER 2: OVERVIEW AND SPECIFICATIONS SPECIFICATIONS

UPDATE RATE

All parameters:...............................Up to 1 second

COMMUNICATIONS FORMAT

Types: ................................................. RS485 port through back plate plus KYZ Pulse (Com Option S)

RS485 serial port and RJ45 Ethernet port through backplate (Com

Option B)

COMMUNICATIONS PORTS

Protocols:.......................................... Modbus RTU, Modbus ASCII (Com Option S)

Modbus TCP/IP, BACnet MS/TP Serial (Com Option B)

Baud rate:.........................................9600 to 57600 bps

Port address:................................... 001 to 247

Data format:....................................8 bits, no parity

MECHANICAL PARAMETERS

Dimensions:..................................... 4.25" × 4.85" × 4.85" (L × W × H)

105.4 mm × 123.2 mm × 123.2 mm (L × W × H)

Mounting:.......................................... mounts in 92 mm square DIN or ANSI C39.1, 4-inch round cut-out

Weight:............................................... 2 pounds / 0.907 kg

METER ENCLOSURE MECHANICAL PARAMETERS

Dimensions:..................................... 8.08" × 11.06" × 13.50" (L × W × H)

205.23 mm × 280.92 mm × 342.9 mm (L × W × H)

Weight:............................................... 25 pounds / 11.4 kg

KYZ/RS485 PORT SPECIFICATIONS

RS485 Transceiver; meets or exceeds EIA/TIA-485 Standard:

Type: .................................................. Two-wire, half duplex

Min. Input Impedance: ............... 96kΩ

Max. Output Current: .................. ±60mA

EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL 2–5

Page 26

SPECIFICATIONS CHAPTER 2: OVERVIEW AND SPECIFICATIONS

WH PULSE

KYZ output contacts (and infrared LED light pulses through face plate):

Pulse Width: ....................................40ms

Full Scale Frequency: ..................6Hz

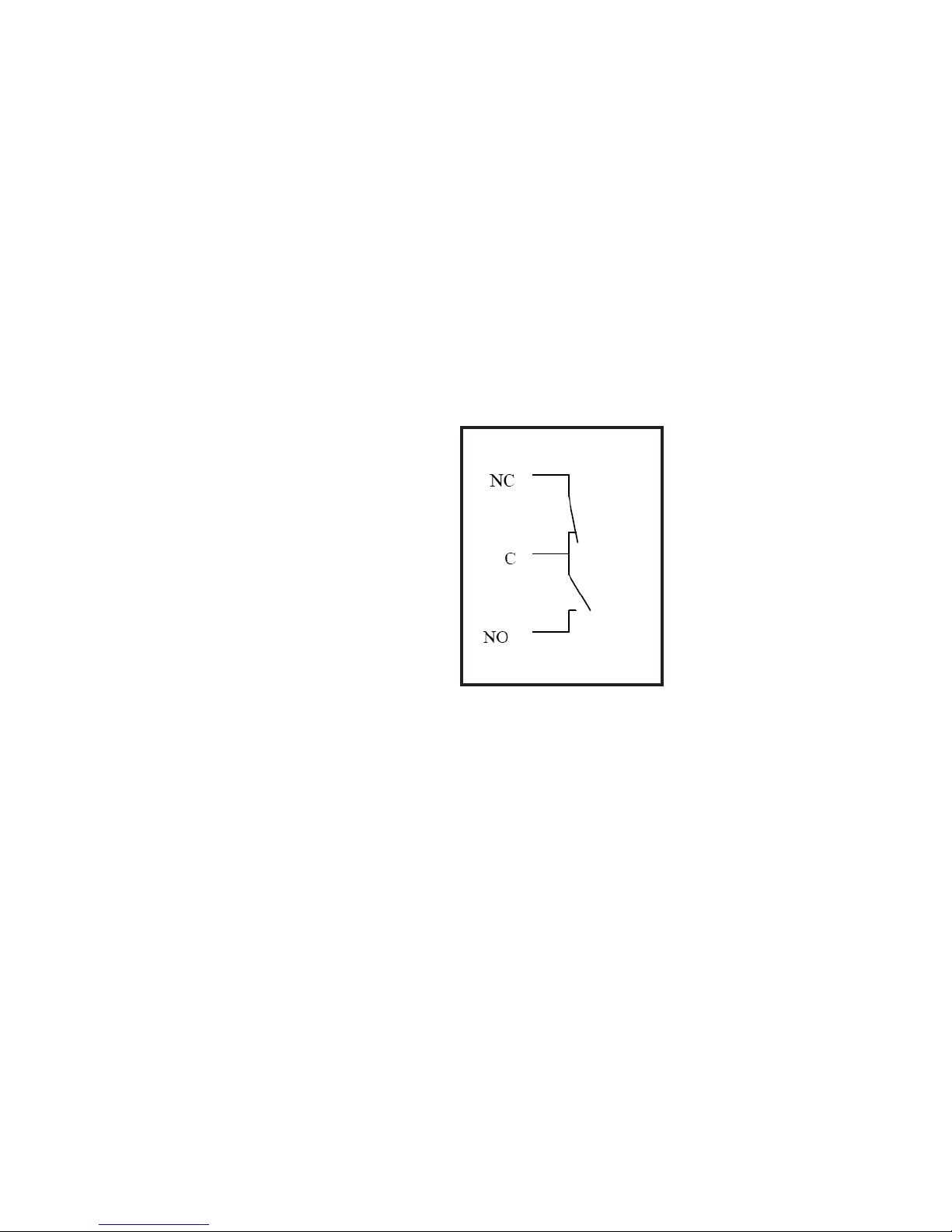

Contact type: ..................................Solid State – SPDT (NO – C – NC)

Relay type: .......................................Solid state

Peak switching voltage: .............DC ±350V

Continuous load current: ..........120mA

Peak load current: ........................350mA for 10ms

On resistance, max.: ....................35Ω

Leakage current: ...........................1μA@350V

Isolation: ...........................................AC 3750V

Reset State: ......................................(NC - C) Closed; (NO - C) Open

Infrared LED:

Peak Spectral Wavelength: ......940nm

Reset State: ......................................Off

Figure 2-1: Internal Schematic (De-energized State)

2–6 EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL

Page 27

CHAPTER 2: OVERVIEW AND SPECIFICATIONS SPECIFICATIONS

Figure 2-2: Output Timing

EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL 2–7

Page 28

COMPLIANCE CHAPTER 2: OVERVIEW AND SPECIFICATIONS

2.3 Compliance

Test Reference Standard

IEC62053-22 (0.5% Accuracy)

ANSI C12.20 (0.5% Accuracy)

CE Compliant

REACH Compliant

RoHS Compliant

Surge Withstand ANSI (IEEE) C37.90.1

Burst ANSI C62.41

Electrostatic Discharge IEC61000-4-2

RF Immunity IEC61000-4-3

Fast Transient IEC61000-4-4

Surge Immunity IEC61000-4-5

Conducted Disturbance Immunity IEC61000-4-6

Magnetic Field Immunity IEC61000-4-8

Voltage Dips and Sags Immunity IEC61000-4-11

Immunity for Industrial Environments EN61000-6-2

Emission Standards for Industrial

EN61000-6-4

Environments

EMC Requirements EN61326-1

APPROVALS

Applicable Council Directive According to:

North America UL Recognized

ISO Manufactured under a registered

quality program

UL61010-1

C22.2. No 61010-1 (PICQ7)

File e200431

ISO9001

2–8 EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL

Page 29

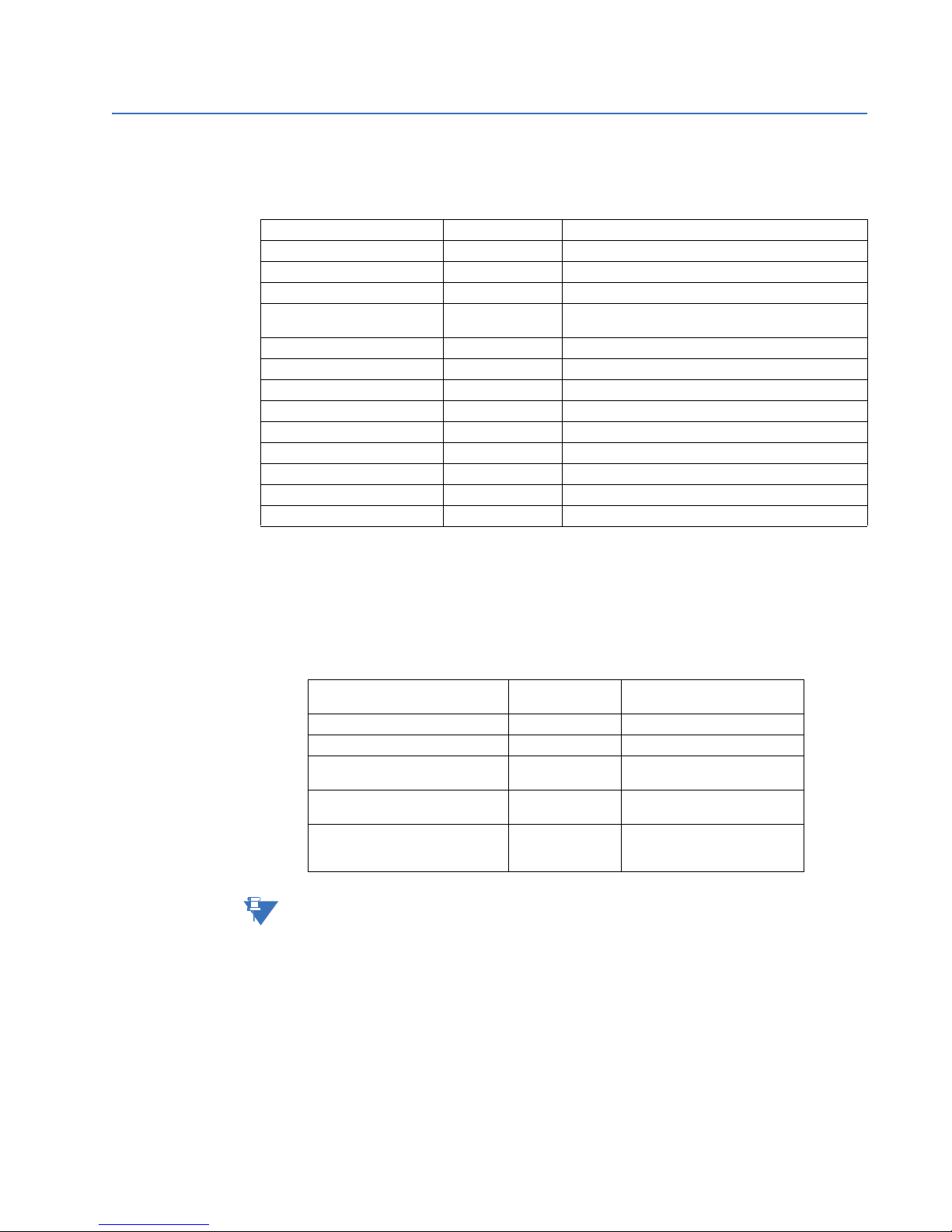

CHAPTER 2: OVERVIEW AND SPECIFICATIONS ACCURACY

NOTE

2.4 Accuracy

For 23 °C, 3 Phase balanced Wye or Delta load.

Parameter Accuracy Accuracy Input Range

Voltage L-N [V] 0.2% of reading

Voltage L-L [V] 0.4% of reading (120 to 600)V

Current Phase [A] 0.2% of reading

Current Neutral (calculated)

2% of Full Scale

[A]

Active Power Total [W] 0.5% of reading

Active Energy Total [Wh] 0.5% of reading

Reactive Power Total [VAR] 1.0% of reading

Reactive Energy Total [VARh] 1.0% of reading

Apparent Power Total [VA] 1.0% of reading

Apparent Energy Total [VAh] 1.0% of reading

Power Factor 1.0% of reading

Frequency +/- 0.01Hz (45 to 65)Hz

Load Bar +/- 1 segment

1

For 2.5 element programmed units, degrade accuracy by an additional 0.5% of reading.

2

For unbalanced voltage inputs where at least one crosses the 150V auto-scale threshold

(for example, 120V/120V/208V system), degrade accuracy by additional 0.4%.

2

(69 to 480)V

1

(0.15 to 5)A

1

(0.15 to 5)A @ (45 to 65)Hz

1,2

(0.15 to 5)A @ (69 to 480)V @ +/- (0.5 to 1) lag/lead PF

1,2

(0.15 to 5)A @ (69 to 480)V @ +/- (0.5 to 1) lag/lead PF

1,2

(0.15 to 5)A @ (69 to 480)V @ +/- (0 to 0.8) lag/lead PF

1,2

(0.15 to 5)A @ (69 to 480)V @ +/- (0 to 0.8) lag/lead PF

1,2

(0.15 to 5)A @ (69 to 480)V @ +/- (0.5 to 1) lag/lead PF

1,2

(0.15 to 5)A @ (69 to 480)V @ +/- (0.5 to 1) lag/lead PF

1,2

(0.15 to 5)A @ (69 to 480)V @ +/- (0.5 to 1) lag/lead PF

1

(0.005 to 6)A

EPM 2200 accuracy meets the IEC62053-22 Accuracy Standards for 0.5% Class Meters.

This standard is shown in the table below.

Value of Current Power Factor Percentage Error Limits for

0.01 I

n ≤ I < 0. 05 In 1 ±1.0

0.05 I

n ≤ I ≤ Imax 1 ±0.5

0.02 I

n ≤ I < 0.1 In 0.5 inductive

0.8 capacitive

0.1 I

n ≤ I ≤ Imax 0.5 inductive

0.8 capacitive

When specially requested by the

user, from:

0.1 I

n ≤ I ≤ Imax

Note

In the table above:

I

n = Nominal (5A)

max = Full Scale

I

0.25 inductive

0.8 capacitive

Meters of Class 0.5 S

±1.0

±1.0

±0.6

±0.6

±1.0

±1.0

EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL 2–9

Page 30

ACCURACY CHAPTER 2: OVERVIEW AND SPECIFICATIONS

2–10 EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL

Page 31

GE

Grid Solutions

3.1 Introduction

EPM 2200 Power Meter

Chapter 3: Mechanical Installation

Mechanical Installation

The EPM 2200 meter can be installed using a standard ANSI C39.1 (4" Round) or an IEC

92mm DIN (Square) form. In new installations, simply use existing DIN or ANSI punches. For

existing panels, pull out old analog meters and replace with the EPM 2200 meter. The

various models use the same installation. See Chapter 4 for wiring diagrams.

POTENTIAL ELECTRICAL EXPOSURE - The EPM 2200 must be installed in an electrical

enclosure where any access to live electrical wiring is restricted only to authorized

service personnel.

EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL 3–1

Page 32

ANSI INSTALLATION STEPS CHAPTER 3: MECHANICAL INSTALLATION

DIN

Mounting

Brackets

ANSI Mounting

Rods (screw-in)

Recommended Tools for EPM 2200 Meter Installation:

• #2 Phillips screwdriver, small wrench and wire cutters.

• Mount the meter in a dry location free from dirt and corrosive substances. The meter

is designed to withstand harsh environmental conditions. (See Environmental

Specifications in 2.2 Specifications on page 2–4.)

3.2 ANSI Installation Steps

3–2 EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL

Figure 3-1: EPM 2200 Mounting Information

1. Insert 4 threaded rods by hand into the back of meter. Twist until secure.

2. Slide ANSI 12 Mounting Gasket onto back of meter with rods in place.

3. Slide meter into panel.

Page 33

CHAPTER 3: MECHANICAL INSTALLATION DIN INSTALLATION STEPS

NEMA12 mounting

gasket

threaded rods

lock washer

and nut

4. Secure from back of panel with lock washer and nut on each threaded rod.

Use a small wrench to tighten. Do not overtighten. The maximum installation

torque is 0.4 Newton-Meter.

Figure 3-2: ANSI Mounting Procedure

3.3 DIN Installation Steps

1. Slide meter with NEMA 12 Mounting Gasket into panel. (Remove ANSI Studs, if

in place.)

2. From back of panel, slide 2 DIN Mounting Brackets into grooves in top and

bottom of meter housing. Snap into place.

3. Secure meter to panel with lock washer and a #8 screw through each of the 2

mounting brackets. Tighten with a #2 Phillips screwdriver. Do not overtighten.

The maximum installation torque is 0.4 Newton-Meter.

EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL 3–3

Page 34

DIN INSTALLATION STEPS CHAPTER 3: MECHANICAL INSTALLATION

DIN mounting

bracket

top-mounting

bracket groove

bottom mounting

bracket groove

#8 screw

EPM 2200 meter

with NEMA 12

mounting gasket

Remove (unscrew)

ANSI studs for DIN

Installation

Figure 3-3: DIN Mounting Procedure

3–4 EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL

Page 35

GE

Grid Solutions

EPM 2200 Power Meter

Chapter 4: Electrical Installation

Electrical Installation

4.1 Considerations When Installing Meters

POTENTIAL ELECTRICAL EXPOSURE - The EPM 2200/6010T must be installed in an

electrical enclosure where any access to live electrical wiring is restricted only to

authorized service personnel.

• Installation of the EPM 2200 Meter must be performed by only qualified personnel

who follow standard safety precautions during all procedures. Those personnel should

have appropriate training and experience with high voltage devices. Appropriate

safety gloves, safety glasses and protective clothing is recommended.

• During normal operation of the EPM 2200 Meter, dangerous voltages flow through

many parts of the meter, including: Terminals and any connected CTs (Current

Transformers) and PTs (Potential Transformers), all I/O Modules (Inputs and Outputs)

and their circuits. All Primary and Secondary circuits can, at times, produce lethal

voltages and currents. Avoid contact with any current-carrying surfaces.

• Do not use the meter or any I/O Output Device for primary protection or in an

energy-limiting capacity. The meter can only be used as secondary protection.

• Do not use the meter for applications where failure of the meter may cause harm or

death. Do not use the meter for any application where there may be a risk of fire.

• All meter terminals should be inaccessible after installation.

• Do not apply more than the maximum voltage the meter or any attached device can

withstand. Refer to meter and/or device labels and to the Specifications for all devices

before applying voltages. Do not HIPOT/Dielectric test any Outputs, Inputs or

Communications terminals.

EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL 4–1

Page 36

CONSIDERATIONS WHEN INSTALLING METERS CHAPTER 4: ELECTRICAL INSTALLATION

• GE requires the use of Fuses for voltage leads and power supply and Shorting Blocks

to prevent hazardous voltage conditions or damage to CTs, if the meter needs to be

removed from service. CT grounding is optional, but recommended.

Note

The current inputs are only to be connected to external current transformers provided

by the installer. The CT's shall be Listed or Approved and rated for the current of the

meter used.

If the equipment is used in a manner not specified by the manufacturer, the protection

provided by the equipment may be impaired.

Note

There is no required preventive maintenance or inspection necessary for safety.

However, any repair or maintenance should be performed by the factory.

DISCONNECT DEVICE: A switch or circuit-breaker shall be included in the end-use

equipment or building installation. The switch shall be in close proximity to the

equipment and within easy reach of the operator. The switch shall be marked as the

disconnecting device for the equipment.

4.1.1 CT Leads Terminated to Meter

The EPM 2200 is designed to have Current Inputs wired in one of three ways. Figure 4-1: CT

leads terminated to meter, #8 screw for lug connection below, shows the most typical

connection where CT Leads are terminated to the meter at the Current Gills.

This connection uses Nickel-Plated Brass Studs (Current Gills) with screws at each end. This

connection allows the CT wires to be terminated using either an “O” or a “U” lug. Tighten

the screws with a #2 Phillips screwdriver. The maximum installation torque is 1 NewtonMeter.

Other current connections are shown in Figures 4-2 and 4-3. A Voltage and RS-485

Connection is shown in Figure 4-4: Voltage Connection on page 4–6.

4–2 EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL

Page 37

CHAPTER 4: ELECTRICAL INSTALLATION CONSIDERATIONS WHEN INSTALLING METERS

Current gills

(nickel-plated

brass stud)

Figure 4-1: CT leads terminated to meter, #8 screw for lug connection

Wiring diagrams are detailed in the diagrams shown below in this chapter.

Communications connections are detailed in Chapter 5.

4.1.2 CT Leads Pass-Through (No Meter Termination)

The second method allows the CT wires to pass through the CT Inputs without terminating

at the meter. In this case, remove the current gills and place the CT wire directly through

the CT opening. The opening will accommodate up to 0.177" / 4.5 mm maximum diameter

CT wire.

EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL 4–3

Page 38

CONSIDERATIONS WHEN INSTALLING METERS CHAPTER 4: ELECTRICAL INSTALLATION

Current gills

removed

CT wire passing

through the meter

Figure 4-2: Pass-Through Wire Electrical Connection

4–4 EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL

Page 39

CHAPTER 4: ELECTRICAL INSTALLATION CONSIDERATIONS WHEN INSTALLING METERS

Crimp CT

terminations

4.1.3 Quick Connect Crimp CT Terminations

For quick termination or for portable applications, a quick connect crimp CT connection

can also be used.

EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL 4–5

Figure 4-3: Quick Connect Electrical Connection

Page 40

CONSIDERATIONS WHEN INSTALLING METERS CHAPTER 4: ELECTRICAL INSTALLATION

Power supply

inputs

Voltage

inputs

RS485 outputs

(do not place voltage

on these terminals!)

4.1.4 Voltage and Power Supply Connections

Voltage Inputs are connected to the back of the unit via a optional wire connectors. The

connectors accommodate up to AWG#12 / 2.5 mm wire.

Figure 4-4: Voltage Connection

4.1.5 Ground Connections

The EPM 2200 ground terminals ( ) should be connected directly to the installation's

protective earth ground. Use 2.5 mm wire for this connection.

4.1.6 Voltage Fuses

GE requires the use of fuses on each of the sense Voltages and on the control power.

• Use a 0.1 Amp fuse on each voltage input.

• Use a 3.0 Amp fuse on the Power Supply.

4–6 EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL

Page 41

CHAPTER 4: ELECTRICAL INSTALLATION ELECTRICAL CONNECTION DIAGRAMS

4.2 Electrical Connection Diagrams

4.2.1 Description

Choose the diagram that best suits your application and maintains the CT polarity.

(1) Wye, 4-Wire with no PTs and 3 CTs, no PTs, 3 Element on page 4–8.

(1a) Dual Phase Hookup on page 4–9.

(1b) Single Phase Hookup on page 4–10.

(2) Wye, 4-Wire with no PTs and 3 CTs, 2.5 Element on page 4–11.

(3) Wye, 4-Wire with 3 PTs and 3 CTs, 3 Element on page 4–12.

(4) Wye, 4-Wire with 2 PTs and 3 CTs, 2.5 Element on page 4–13.

(5) Delta, 3-Wire with no PTs, 2 CTs on page 4–14.

(6) Delta, 3-Wire with 2 PTs, 2 CTs on page 4–15.

(7) Delta, 3-Wire with 2 PTs, 3 CTs on page 4–16.

(8) Current-Only Measurement (Three-Phase) on page 4–17.

(9) Current-Only Measurement (Dual-Phase) on page 4–18.

(10) Current-Only Measurement (Single-Phase) on page 4–19.

EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL 4–7

Page 42

ELECTRICAL CONNECTION DIAGRAMS CHAPTER 4: ELECTRICAL INSTALLATION

lc

HI

LO

lb

HI

LO

la

HI

LO

Earth Ground

L(+)

Power

Supply

Connection

N(-)

L(+)

GND

N(-)

Vref

Va

Vb

Vc

LINE

LOAD

CT

Shorting

Block

FUSES

3 x 0.1A

FUSE

3A

C

C

B

B

A

A

N

N

4.2.2 (1) Wye, 4-Wire with no PTs and 3 CTs, no PTs, 3 Element

For this wiring type, select 3ELWYE (3-element Wye) in the meter programming setup.

4–8 EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL

Figure 4-5: 4-Wire Wye with no PTs and 3 CTs, 3 Element

Page 43

CHAPTER 4: ELECTRICAL INSTALLATION ELECTRICAL CONNECTION DIAGRAMS

lc

HI

LO

lb

HI

LO

la

HI

LO

Earth Ground

x

L(+)

Power

Supply

Connection

N(-)

L(+)

GND

N(-)

Vref

Va

Vb

Vc

LINE

LOAD

CT

Shorting

Block

FUSES

2 x 0.1A

FUSE

3A

C

C

B

B

A

A

N

N

Figure 4-6: (1a) Dual Phase Hookup

EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL 4–9

Page 44

ELECTRICAL CONNECTION DIAGRAMS CHAPTER 4: ELECTRICAL INSTALLATION

lc

HI

LO

lb

HI

LO

la

HI

LO

Earth Ground

x

L(+)

Power

Supply

Connection

N(-)

L(+)

GND

N(-)

Vref

Va

Vb

Vc

LINE

LOAD

CT

Shorting

Block

x

FUSE

0.1A

FUSE

3A

C

C

B

B

A

A

N

N

Figure 4-7: (1b) Single Phase Hookup

4–10 EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL

Page 45

lc

HI

LO

lb

HI

LO

la

HI

LO

Earth Ground

L(+)

Power

Supply

Connection

N(-)

L(+)

GND

N(-)

Vref

Va

Vb

Vc

LINE

LOAD

CT

Shorting

Block

FUSES

2 x 0.1A

FUSE

3A

C

C

B

B

A

A

N

N

CHAPTER 4: ELECTRICAL INSTALLATION ELECTRICAL CONNECTION DIAGRAMS

4.2.3 (2) Wye, 4-Wire with no PTs and 3 CTs, 2.5 Element

For this wiring type, select 2.5EL WYE (2.5-element Wye) in the meter programming setup.

EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL 4–11

Figure 4-8: 4-Wire Wye with no PTs and 3 CTs, 2.5 Element

Page 46

ELECTRICAL CONNECTION DIAGRAMS CHAPTER 4: ELECTRICAL INSTALLATION

lc

HI

LO

lb

HI

LO

la

HI

LO

Earth Ground

Earth Ground

L(+)

Power

Supply

Connection

N(-)

L(+)

GND

N(-)

Vref

Va

Vb

Vc

LINE

LOAD

CT

Shorting

Block

FUSES

3 x 0.1A

FUSE

3A

C

C

B

B

A

A

N

N

4.2.4 (3) Wye, 4-Wire with 3 PTs and 3 CTs, 3 Element

For this wiring type, select 3ELWYE (3-element Wye) in the meter programming setup.

4–12 EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL

Figure 4-9: 4-Wire Wye with 3 PTs and 3 CTs, 3 Element

Page 47

CHAPTER 4: ELECTRICAL INSTALLATION ELECTRICAL CONNECTION DIAGRAMS

lc

HI

LO

lb

HI

LO

la

HI

LO

Earth Ground

Earth Ground

L(+)

Power

Supply

Connection

N(-)

L(+)

GND

N(-)

Vref

Va

Vb

Vc

LINE

LOAD

CT

Shorting

Block

FUSES

2 x 0.1A

FUSE

3A

C

C

B

B

A

A

N

N

4.2.5 (4) Wye, 4-Wire with 2 PTs and 3 CTs, 2.5 Element

For this wiring type, select 2.5EL WYE (2.5-element Wye) in the meter programming setup.

EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL 4–13

Figure 4-10: 4-Wire Wye with 2 PTs and 3 CTs, 2.5 Element

Page 48

lc

HI

LO

lb

HI

LO

la

HI

LO

Earth Ground

L(+)

Power

Supply

Connection

N(-)

L(+)

GND

N(-)

Vref

Va

Vb

Vc

LINE

LOAD

CT

Shorting

Block

FUSES

3 x 0.1A

FUSE

3A

C

C

B

B

A

A

ELECTRICAL CONNECTION DIAGRAMS CHAPTER 4: ELECTRICAL INSTALLATION

4.2.6 (5) Delta, 3-Wire with no PTs, 2 CTs

For this wiring type, select 2CtdEL (2 CT Delta) in the meter programming setup.

4–14 EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL

Figure 4-11: 3-Wire Delta with no PTs and 2 CTs

Page 49

CHAPTER 4: ELECTRICAL INSTALLATION ELECTRICAL CONNECTION DIAGRAMS

4.2.7 (6) Delta, 3-Wire with 2 PTs, 2 CTs

For this wiring type, select 2CtdEL (2 CT Delta) in the meter programming setup.

LINE

B

A

C

CT

Shorting

Block

Earth Ground

HI

lc

LO

FUSES

2 x 0.1A

lb

Power

Supply

Connection

GND

FUSE

HI

HI

la

LO

LO

L(+)

N(-)

Vref

Va

Vb

Vc

3A

L(+)

N(-)

B

A

C

LOAD

EPM 2200 POWER METER – INSTRUCTION MANUAL 4–15

Earth Ground

Figure 4-12: 3-Wire Delta with 2 PTs and 2 CTs

Page 50

ELECTRICAL CONNECTION DIAGRAMS CHAPTER 4: ELECTRICAL INSTALLATION

lc

HI

LO

lb

HI

LO

la

HI

LO

Earth Ground

Earth Ground

L(+)

Power

Supply

Connection

N(-)

L(+)

GND

N(-)

Vref

Va

Vb

Vc

LINE

LOAD

CT

Shorting

Block

FUSES

2 x 0.1A

FUSE

3A

C

C

B

B

A

A