Page 1

INSTALLATION & OPERATING TIPS

1. CLEAN FLUIDS. Abrasives in the pumped fluid

may damage cylinder and piston surfaces and

should, therefore, be avoided. Carbon cylinder liners and stainless steel pistons are particularly susceptible to abrasion by particulate matter in the

pumped stream. Ceramic piston/cylinder components are more tolerant of suspended solids, except solids that tend to flock and impede the

movement of the piston in the cylinder.

2. COMPATIBLE FLUIDS. Pump only fluids compatible with materials of construction of the pump

head you have selected.

3. WET OPERATION. The pumped fluid provides

surface cooling and lubrication to the piston and

cylinder of your FMI PUMP. Therefore, avoid dry

operation (except pumps specifically designated

“gas pump”).

4. FLOW VOLUME AND DIRECTION. Angular deflection of the cylinder with respect to the zero

point on the calibration scale of your FMI “Q”

PUMP controls flow magnitude and direction e.g.,

with the cylinder pointer at 10 on the left scale, fluid

will be passed from the right port to the left port at

100% of the maximum rated volume; with the

pointer at 10 on the right scale, fluid will pass from

the left port to the right port at maximum rate. Set

at 5 on the scale, flow rate will be 50% of maximum; at 4, it will be 40%; at 3, 30%, etc., etc. The

flow control setting may be changed (including flow

reversal) at any time while the pump is operating or

idle. Slightly loosen the two thumb screws and turn

the STROKE LENGTH ADJUSTMENT KNOB.

Retighten thumb screws once the desired setting

is reached.

5. PISTON SEALS. The R408 seals that keep your

PUMP piston dry are not “just ordinary plastic

discs.” They are precisely cut and hot formed from

sheets of a chemically inert fluorocarbon, specifically formulated for resistance to wear, abrasion,

heat and chemical attack.

Each R408 seal possesses an exceptional mechanical memory which allows it to maintain a relatively constant wiping pressure on the piston,

compensating for seal wear as it occurs. Properly

maintained in clean condition, the original seals on

a FMI PUMP may be expected to last the life of

the pump. If they are removed for any reason,

they should be carefully cleansed of all foreign particles prior to re-assembly. Seal seats must also be

free of particles. (please see para 18)

6. DIAL INDICATOR. (optional) The Dial Indicator

Kit is for fine adjustment and continuous monitoring of your “Q” pump flow rate settings.

To adjust Dial Indicator equipped pumps:

1.Loosen thumb screws, turn STROKE LENGTH

ADJUSTMENT KNOB, moving cylinder assembly

to neutral (zero-flow position).

2. Adjust indicator pointers until they read zero on

both dials.

3.You are now ready for fine setting by turning

STROKE LENGTH ADJUSTMENT KNOB until

you achieve desired flow rate on dial. To prevent

system backlash always turn STROKE LENGTH

ADJUSTMENT KNOB two turns or one full revolution of large dial beyond desired setting, then adjust back.

7. 4-20 mA CONTROL for automatic response to

remotely generated 4-20 milliamp signals is standard on V300 controllers. The input can be either

grounded or ungrounded. The current source connects to terminal posts mounted on front cover assembly of the STROKE RATE CONTROLLER. Be

sure to observe correct polarity. For complete

hook-up and operating information see page 10.

8. PRESSURE. Do not operate pump against

head pressures in excess of design specification.

Drive arm on piston may bend or break under

overload and other irreparable damage may be

suffered. Check your fluid circuit before apply-

ing power to the pump!

9. ELECTRICAL PROTECTION. All FMI PUMPS

are positive displacement in struments and should

be protected by lowest possible “slo blow” fuse or

circuit breaker electrical arrangements. “QV” units

come equipped with .75 amp fuses.

10. NOISE AT HIGH PUMP RATES. A metallic

hammering noise during operation of your pump

1

IN-Q431-09A

Before using any Fluid Metering, Inc. product read the following safety instructions as well as specific product

specifications and operating instructions.

Warning!

Fire, electrical shock or explosion may occur if used near combustibles, explosive atmosphere, corrosive air,

wet environment or submerged in fluid.

!

Caution! Fire, electrical shock, injury and damage may

occur if not used in accordance with Fluid Metering, Inc.

specifications and operation instructions.

Do not put wet fingers into power outlet of unit.

Do not operate with wet hands.

Do not operate drive assemblies that require a hard mount

(to be bolted down) unless they are mounted per Fluid Metering, Inc.

specifications. If not, injury may occur and/or damage to unit.

Do not touch any rotating pump or motor components: injury may

occur.

Do not run pump dry, unless designed for that service.

Running dry is harmful to the pump, and will cause excessive heating

due to internal friction.

Check pump rotation and inlet/outlet pump port orientation before

connecting power to pump. If not, injury may occur.

When pulling out cords from outlets do not pull cord, grasp plug to

prevent plug damage or electrical shock.

Fluid Metering, Inc. Drive Motors become HOT and can cause

a burn

. DO NOT TOUCH!

Turn off the electrical power before checking pump for any problems.

Connect motor, speed controllers, or any other electrical devices

based on Fluid Metering Inc. specifications. Any unauthorized work

performed on the product by the purchaser or by third parties can impair product functionality and thereby relieves Fluid Metering, Inc.

of all warranty claims or liability for any misuse that will cause

damage to product and/or injury to the individual.

Power cables and leads should not be bent, pulled or inserted by excessive force. Otherwise there is a threat of electrical shock or fire.

Replace any inline fuses only with fuse rating as specified by Fluid

Metering, Inc.

When pump/drive is under operation, never point discharge tubing

into face or touch any rotating components of pump.

In a power down thermal overload cut-in condition, unplug or turn off

power to pump. Always allow a cool down period before restarting:

otherwise, injury or damage may occur.

For 30 seconds after power is removed from pump/drive: do not

touch any output terminals. Electrical shock may occur because of

residual voltage.

!

SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS

“Q” PUMP INSTRUCTIONS

CeramPump

®

!

1

Page 2

(particularly high speed units such as QB, QD,

QDX, and QV) when pumping liquids indicates

presence of gas bubbles in the pumping chamber

which are reducing pumping capacity and may be

damaging cylinder walls. Such bubbles may be

traced to 1) a poor seal at the suction fitting, 2) fluid

vaporization (cavitation) or, 3) degassing of the

fluid.

a) To correct suction fitting leaks in stainless steel

pump heads, remove fitting and wrap two layers of

Teflon tape (standard Lab plumbing variety, 1 to 2

mil thick x 1/2" wide) tightly into the threads of the

fitting. Replace fitting in cylinder port, drawing

threads tightly on the Teflon tape. (see para 16).

b) To eliminate vaporization and degassing noise,

reduce suction load. This may be accomplished

by: 1) Using the 3/8" dia. TUBE ADAPTER R4122 supplied with each pump on the suction line of

the pump head to increase inside diameter of the

suction line (use 1/2" dia. TUBE ADAPTER R4126K on -3 PHM’s.); 2) reduction of suction lift height;

3) pressurization of suction supply container; 4) locating pump below supply source to permit gravity

flow aid; 5) reduce viscosity of fluid by heating or

thinning; 6) reduce flow rate by adjusting pump to

lower setting on flow scale; 7) install FMI PD-HF

PULSE SUPPRESSORS in suction and discharge

lines.

Improvements in noise abatement and pump life

can be gained by putting pulse suppression hardware in the plumbing circuits adjacent to the pump

suction and discharge ports - particularly with high

speed pumps that are plumbed with rigid tubing.

Theory holds that if part of a generated pulse is resiliently stored, the part not stored is smaller and

thus easier to get into motion; the stored part of the

pulse dissipating behind the part that is in motion

sustains motion, causing an undulating flow to be

transmitted rather than a series of pulses. Result:

less noise, less energy used and less agitation of

the pumped fluid. So for pulse noise and vibration

problems, put a little resilience in your circuit.

There are a number of rather easy ways to do it:

c) The simplest method is to use resilient tubing

between the pump and the fluid circuit. Experiment

a bit with standard elastomers - viton, hypalon,

gum rubber, soft vinyl or other. Use only unreinforced tubing (reinforcement takes away the resilience). Always shield this type of arrangement

so that a possible tube rupture will not endanger

people or equipment.

d) Another popular pulse suppression arrangement involves a gas bubble trap as described in

the final sentences of para. 12. A bubble in such a

vertical trap will suppress pulse shock and noise

temporarily. However, since gas and a liquid in

contact under agitated conditions seldom stabilize,

the trapped gas may absorb into the passing liquid

and disappear leaving no pulse suppression or the

fluid may contribute to the gas quantity, overload

the trap and cause random pumping errors as occasional bubbles enter the flow stream. This can

be overcome by fitting a soft slug of closed-cellplastic foam or a soft pillow of thin-wall plastic tubing (ends sealed) into the vertical dead end

extension of the fluid line. The gas trapped in the

foam or pillow will provide the required resilience

but will not be absorbed by the flow stream.

e)Since each fluid and circuit exhibits differing

characteristics, a bit of experimentation may be

necessary. The results are usually worth the effort.

11. FOR BEST LOW FLOW PUMPING RESULTS:

Use a pump having a maximum flow rating as near

to the desired flow rate as possible and keep suction and discharge pressures essentially constant

(see para 13). FMI pumps using R479 Low Flow

Kits or designated LF are specifically designed for

low flow/low dead volume, 1/4-28 flat bottom fittings.

12. LOW FLOW BUBBLE PROBLEMS.

A common cause of trouble in metering pump applications requiring low flow rates - a few milliliters

per minute or less - is the seemingly inevitable gas

bubble trapped in the pumping head of the metering pump. It expands on the suction stroke and

contracts on the discharge stroke, allowing little, if

any, liquid to pass through the pump. Such bubbles, though often attributed to leaks in pump

seals, can usually be traced to gases released by

the pumped fluid in response to pumping agitation

or pressure/temperature changes. When so identified, this potential source of metering pump error

can be effectively controlled in most fluid circuits.

The familiar bubbles that form on the inside walls

of a tumbler of tap water after it stands for a period

of time at room temperature demonstrate the typical liquid degassing that results from pressure reduction (water line pressure to atmospheric) and/or

temperature elevation (from ground ambient to air

ambient). In this case, the bubbles contain air, hydrogen, carbon dioxide or other gaseous materials

carried in the water; only small quantities of vaporized water are present. Some liquids respond to

agitation and/or pressure/temperature changes by

chemically separating into liquid and gas fractions;

others simply vaporize, physically changing from

liquid to gaseous form. Examples of liquids releasing gas or changing from liquid to gaseous form in

response to agitation and temperature/pressure

changes are numerous in the modern technical environment and many techniques have been devised to compensate for or correct their presence.

The most common practices for bubble control employ:

a) pressure on the suction side of the pump circuit

to encourage gas retention in the liquid or,

b) employ natural buoyancy of the bubbles to carry

them away from or through the pump head.

To apply pressure on the suction side of the pump,

locate the pump physically below the supply vessel. Each two feet of elevation difference represents pressure of approximately one pound per

square inch (psi). Bubbles that do occur will return

to the supply vessel by buoyant lift. This is called

a positive suction or flooded suction arrangement.

If it is necessary to draw liquid up from the supply

vessel to the pump head, negative suction pressure must be contemplated - again, approximately

1 psi per two feet of lift. Most liquids will release

some gas when held at negative pressure and

since the volume of gas released is generally proportionate to the volume of liquid subjected to the

negative pressure, suction line diameter should be

kept small for small flows (except heavy, viscous or

tacky liquids which require large flow area for mobility). A vertical dead-end extension of the suction

line can be provided above the pump suction port

to trap line-generated bubbles before they enter

the pump. This extension should be liquid filled at

the start of a pumping period. Stand the pump vertically by loosening the screws and repositioning

the Multi-Position Tilt Stand Q650 so that pump is

in standing position, or hang the pump vertically by

its base key slots. The discharge port should now

be above the suction port allowing bubbles that

enter the pump head to pass directly through with

buoyant assist. Discharge lines should be inclined

upward from pump head and bubble traps should

be purged as often as necessary to assure liquid

flow continuity.

13. SYSTEM ACCURACY FACTORS.

Several interrelated factors are involved in the exceptional operating accuracy possible in systems

using FMI PUMPS. Of primary concern are the following:

a) FMI PUMP DISPLACEMENT precision is based

on a simplified positive stroke mechanism which

has no secondary linkages to produce stroke to

stroke mechanical errors and has no gravity actuated or spring loaded valves to introduce random

valve seating errors. The single mechanical linkage component between the PUMP piston and its

drive elements is a precision spherical bearing

which transforms circular drive motion into elliptical

thrust motion (reciprocation). The total mechanical

clearance of this linkage is less than 0.1% of the

maximum pump stroke length or, approximately

0.0003". Thus it may be said that PUMP displacement precision (stroke to stroke) is in the order of

the mechanical linkage clearance; that is to say,

stroke to stroke displacement is reproducible to

less than 0.5% within the rated capacity of a given

pump model.

b) FMI PUMP VALVING is performed by a flat in

the piston which is mechanically aligned with one

cylinder port during the suction portion of each

stroke and with the other cylinder port during the

discharge portion of each stroke. The flat alignment is controlled by the single drive bearing discussed in the preceding sentences. The valve

action is therefore mechanically precise, and free

of random closure variations.

c) FLUID SLIP, a term commonly used to describe

the migration of fluid around the internal moving

parts of gear, lobe and vane pumps, is the volumetric difference between physical component displacement and fluid through-put of a pump system.

In the FMI PUMP, slip loss refers to the fluid which

passes through the clearance space (approx.

.0002") between the piston and the cylinder wall.

Since this clearance represents a restrictive passage of essentially constant dimension, it will be

readily seen that the slip rate is determined by viscosity, pressure and time: e.g. assuming constant

fluid viscosity and pressure, slip will be a smaller

factor in a high repetition rate pump (short time per

stroke) than in a low repetition rate pump. As viscosity increases and pressure decreases, time (or

repetition rate) becomes less a significant contributor to slip loss.

d) STROKE REPETITION RATE is directly related

to drive motor speed which in turn is influenced by

work load and electrical supply voltage, i.e., motor

speed decreases when work load increases and

when electrical supply voltage (115 Volts AC) decreases. This motor speed variation may amount

to as much as 15% for work load variations between zero discharge pressure and maximum

rated discharge pressure. A 10% voltage drop may

2

IN-Q431-09A

Page 3

result in as much as 20% motor speed reduction

when the pump is operating against a significant

head pressure.

e) THE FLOW STABILITY (precision) of an FMI

PUMP is therefore principally related to consistency in fluid slip rate and stroke repetition rate and

these functions in turn are related to external system load factors such as viscosity, differential pressure and electric line voltage; i.e., when load

factors remain essentially constant, slip rate and

repetition rate remain essentially constant; when

viscosity increases, fluid slip rate and stroke repetition rate both decrease; when differential pressure increases fluid slip rate increases and stroke

repetition rate decreases. In short, FMI PUMP

PRECISION is influenced by fluctuations of fluid

differential pressures, fluid viscosity and electric

line voltage. When these factors are controlled predictably reproducible pumping precision better

than 0.5% may be expected.

MAINTENANCE & REPAIR

INSTRUCTIONS

14. LUBRICATION. Pump drive elements are pro-

vided with oil fittings at all appropriate points. Use

high grade machine oil at regular intervals. A dab

of good grease on PISTON DRIVE PIN just before

it is inserted into the RADIAL BEARING in the

SPINDLE ASSEMBLY does a world of good for the

bearing and pin.

15. CHANGING THE LIQUID END OF YOUR FMI

“Q” PUMP. (figures 1,2).

a) To remove “Q” Pump Head Module (QPHM):

1. Turn power off.

2. Rotate STROKE LENGTH ADJUSTMENT

KNOB to position PUMP HEAD CARRIER Q4102 all the way to the extreme right or left of scale

(fig. 1).

3. Rotate SPINDLE ASSEMBLY Q424 to place

PISTON DRIVE PIN at 3 or 9 o’clock position (facing cylinder head).

4. Loosen two KNURLED NUTS.

5. Lift QPHM and draw gently away from Q424

SPINDLE ASSEMBLY(fig. 2).

6. Move QPHM up and to the left while slipping

DRIVE PIN out of RADIAL BEARING.

b) To replace QPHM:

1. With PISTON ASSEMBLY R423 extending approximately 1-1/4" from CYLINDER NUT R406K

and DRIVE PIN in the 3 or 9 o’clock position, insert PIN into the RADIAL BEARING in the SPINDLE ASSEMBLY.

2. Slide QPHM into position on BASE making sure

locator on bottom of CARRIER Q410-2 drops into

slotted portion of FOLLOWER Q454-2 on base.

3. Tighten KNURLED NUTS on Q616 assembly

16. CHANGING FITTINGS ON STAINLESS

STEEL PUMP HEADS

IMPORTANT!

Fittings screwed too tightly into stainless steel

pump heads will contact port seals and may cause

piston/cylinder damage. Use extra layers of Teflon

tape on threads when necessary to avoid such excessive penetration.

17. CLEANING PUMP HEAD. Routine flushing

with solvent before shut-down will suffice for most

applications - set pump for maximum stroke and

operate until solvent appears clear at discharge

port. If periodic teardown for detail cleaning is required, remove parts with care to avoid damage to

piston, cylinder and gland. Wipe all parts with lintless oil saturated cloth. Operate by hand after reassembly to assure free movement of parts prior to

application of power.

17.1 CAUTION! Ceramic piston/cylinder sets are

particularly sensitive to neglect and may “freeze”

if allowed to dry out without adequate cleansing.

Some users actually remove the piston from the

cylinder after solvent cleaning and store the component parts in disassembled condition until the

pump is again required. Others fill a loop of flexible

tubing with fluid that will thin or neutralize the last

fluid pumped. They then connect one end of the

tube to the pump suction port, the other to the discharge port. With this loop positioned above the

pump head, the ceramic surfaces and seal areas

will stay moist and mobile for extended idle peri-

ods. If, however, a piston (ceramic or stainless

steel) does freeze in the cylinder, DO NOT TRY

TO FORCE IT FREE! Be gentle. Try to remove

the pump head (refer para 15) from the base assembly so that the whole assembly can be soaked

in a suitable solvent. If the head is not conveniently removable, the tube loop discussed in the

prior paragraph may permit solvent to dissolve the

“frozen” residue in reasonable time. Having a

spare pump head on hand in case of emergency is

always a good idea.

17.2 SANITARY SERVICE. FMI sanitary pump

heads, designated SAN are designed to conform

with the cleansing standards of the U.S. Food and

Drug Administration.

To clean individual component parts:

a)Unscrew 2 CYLINDER NUTS R406-S and 2

PORT NUTS 110348-P.

b)Remove piston and seal components released

by step a) above;

c)Use fingers to wiggle LINER R407-C slipping it

from CYLINDER CASE R405-SAN;

d)Cleanse and sterilize component parts as per

government regulations for parts manufactured of

Alumina Ceramic, Type 316 Stainless Steel and

Teflon. After cleaning, reassemble the components

as follows:

e)Assemble piston/seal components as per instructions para 18 a,b,c;

f)Orient CYLINDER LINER R407-C in CYLINDER

CASE R405-SAN in such a manner that the side

port flats on CYLINDER LINER R407-C should be

visible through the side port openings on CYLINDER CASE R405-SAN.

g)Place one each port seal component R412-T

into each side port of CYLINDER CASE R405SAN using finger pressure across the two ports

to assure flush seating of the seal surfaces on

the cylinder liner flats.

h)Apply PORT NUT 110348-P to each port, finger

tight.

i)Carefully insert piston into cylinder liner until

threads of CYLINDER NUT

R406-S meet threads of CYLINDER CASE R405SAN. Tighten NUT R406-S finger tight.

Continued on Page 12

3

IN-Q431-09A

For maximum pump performance, mount

the pump with motor at 12 o’clock and

pump head at 6 o’clock position. This orientation will allow air bubbles that enter

the pumping chamber to directly exit thru

buoyant assist. Discharge lines should be

inclined upward from pump head.

IMPORTANT

RECOMMENDED FMI PUMP MOUNTING FOR MAXIMUM

PERFORMANCE

GOOD

BETTER

BEST

NOT

RECOMMENDED

figure 1

figure 2

KNURLED

NUTS

Q424

R408

R409

figure3

figure 4

DRIVE PIN

R423

R406

Page 4

4

IN-Q431-09A

Page 5

5

IN-Q431-09A

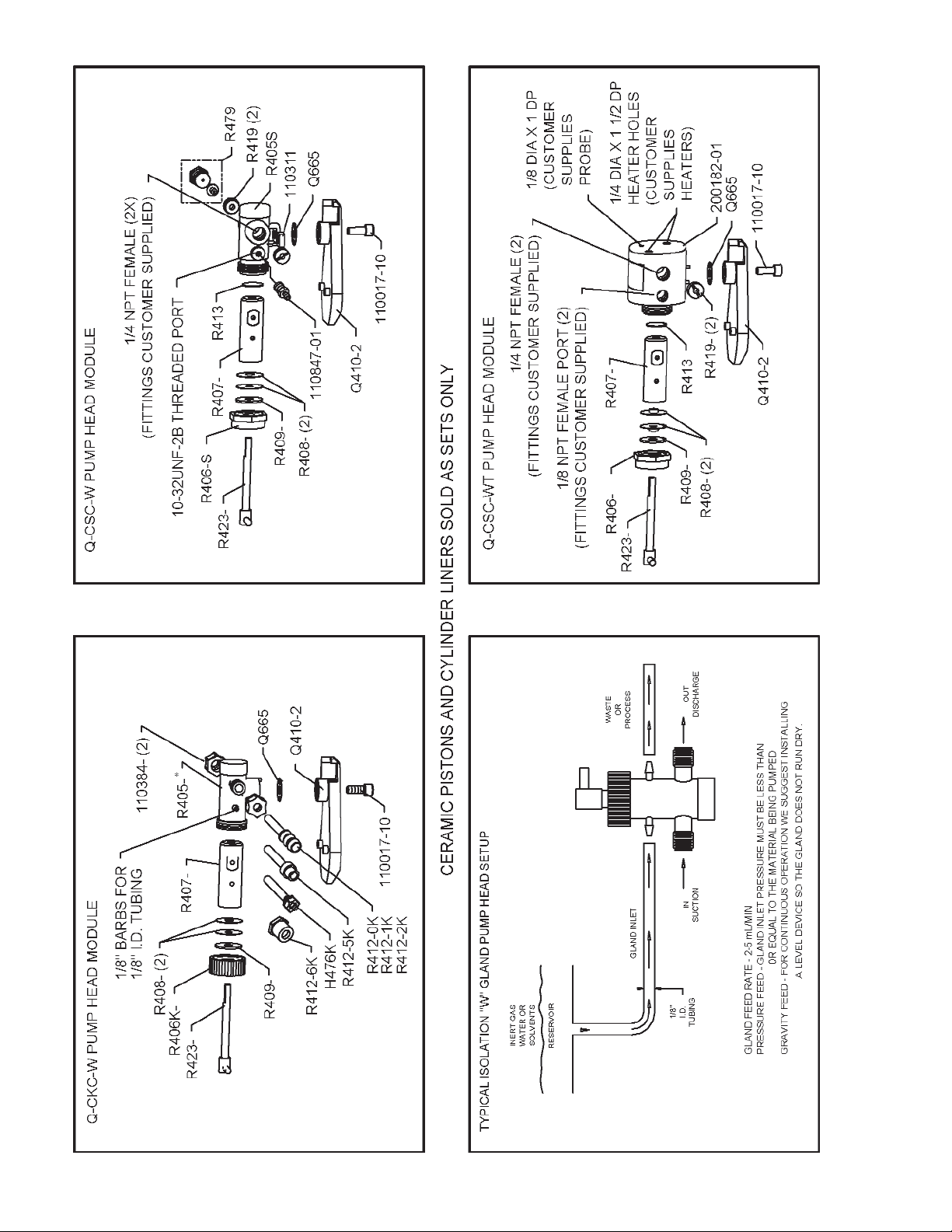

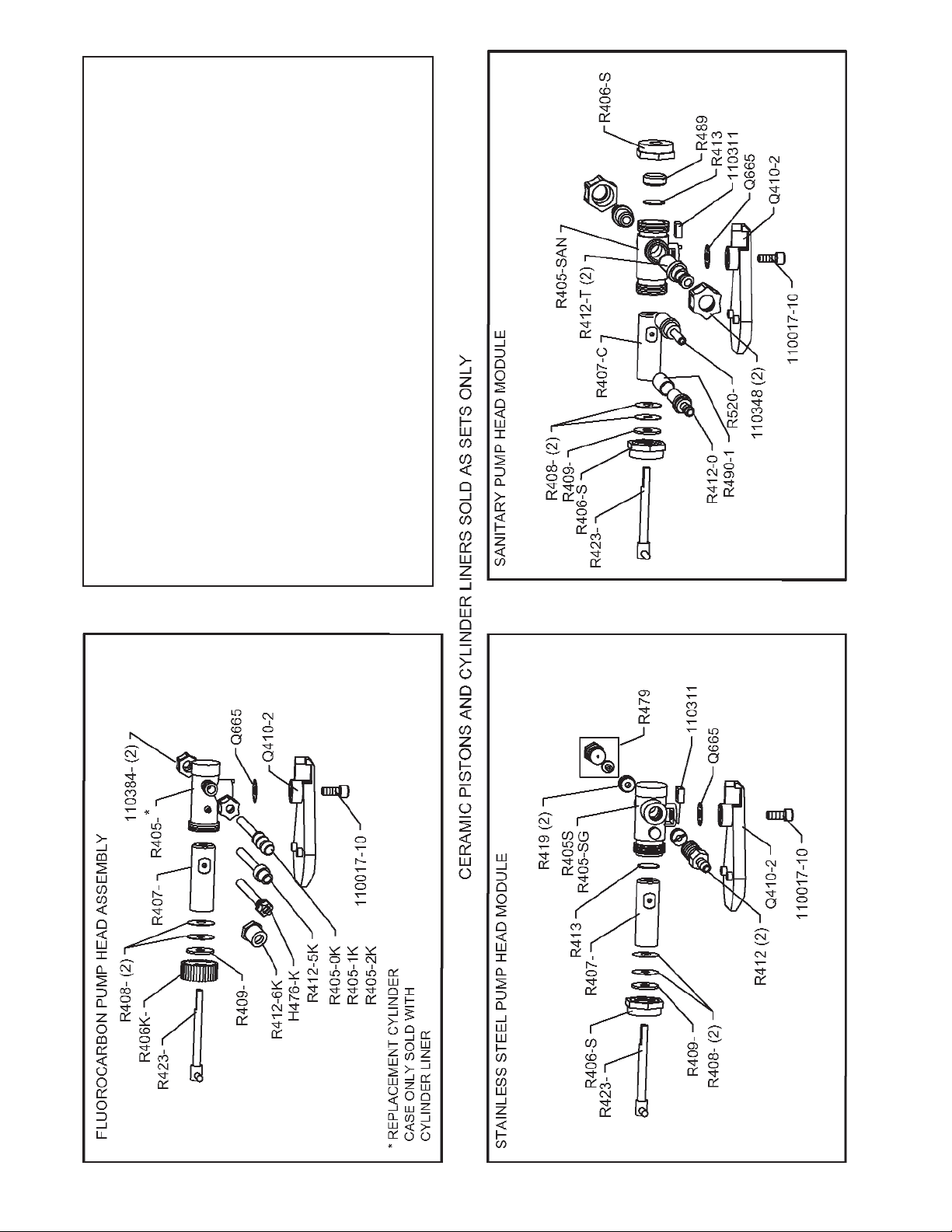

IMPORTANT!

WHEN ORDERING REPLACEMENT PARTS PLEASE MEN-

TION MODEL AND SERIAL NUMBERS OF THE PUMP ON

WHICH THEY WILL BE USED.

REPLACEMENT CYLINDER CASE (R405-K) ONLY SOLD

WITH CYLINDER LINER

CERAMIC PISTONS & CYLINDER LINERS SOLD AS SETS

ONLY

PLEASE NOTE: FMI will PROVIDES A REPAIR ESTIMATE

WITHIN 48 HOURS (SEE PAGE 7 FOR DETAILS)

Page 6

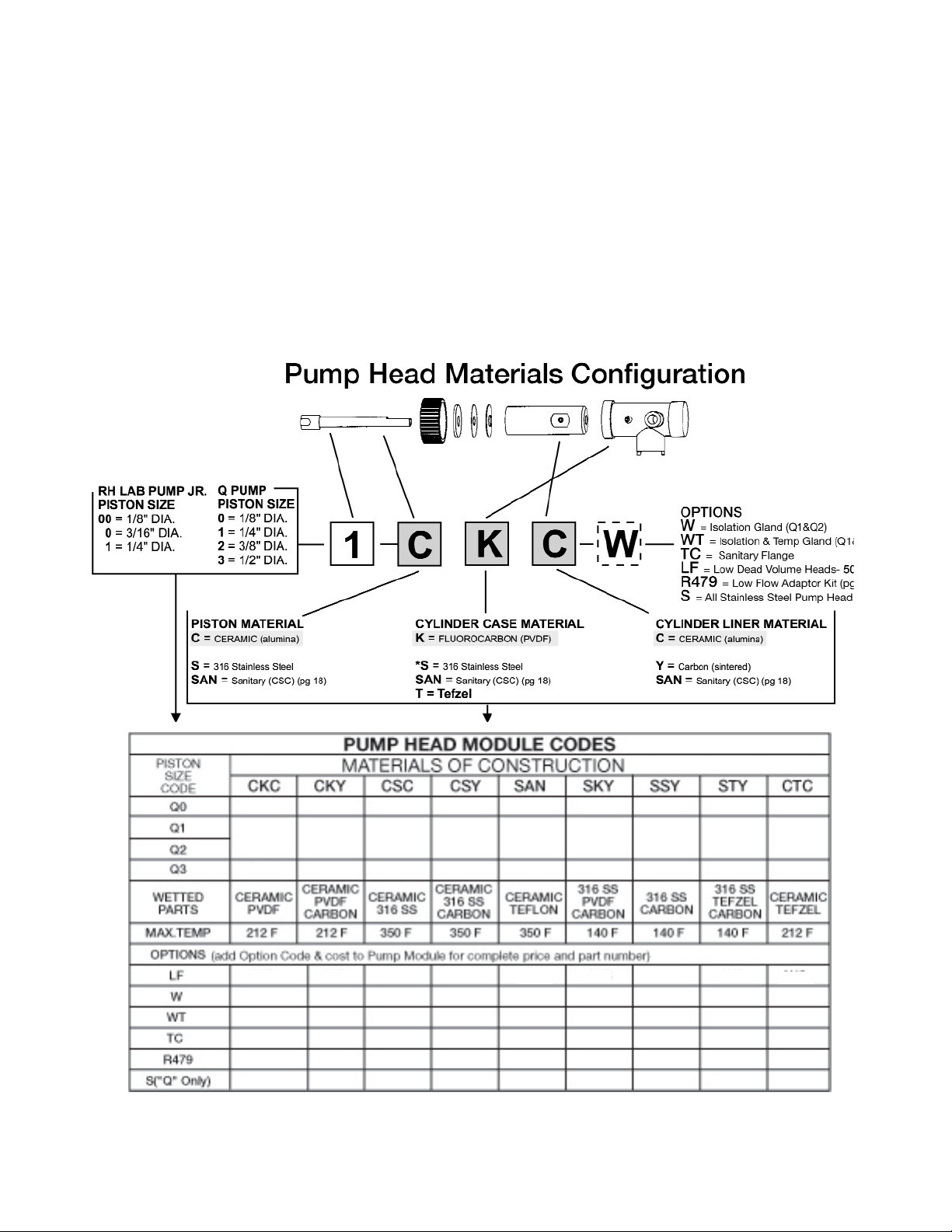

PUMP HEAD INFORMATION

THINGS YOU SHOULD KNOW BEFORE ORDERING THE FLUID HANDLING PORTION (or

parts thereof) OF AN FMI MODEL Q PUMP, i.e.

the removable assembly that is often referred to

as the liquid end, the piston/cylinder set, or the

Pump Head Module (PHM) assembly.

To accommodate the diverse demands of laboratory and industrial pumping applications, FMI’s QPumps are arranged to accept interchangeable

PHM’s with differing chemical and mechanical

characteristics. There are a number of these assemblies from which the pump user may select in

solving difficult fluid pumping problems.

To simplify the selection process, each individual

type of fluid handling assembly (piston/cylinder

set) is designated by an alpha-numeric code which

permits direct identification of pertinent factors.

Q-PUMP DESIGNATIONS

Example:

Q-1-SAN denotes a sanitary construction pump

head assembly having a 1/4” diameter ceramic

piston, ceramic cylinder liner and a 316 stainless

steel cylinder case.

PLEASE NOTE:

1. When the last three of the above shown categories are not called out, standard materials and

construction are implied (CKC).

2. If SAN is designated in the last category, the

preceding three categories will be designated CSC

as required by FDA specifications.

3. Piston seals made of an inert material, Rulon

AR, are used in all FMI type Q Pump Heads except

high speed pumps fitted with stainless steel pistons (these use Rulon J seals) and sanitary (SAN)

pump heads which require virgin Teflon (T) seals.

Specify AR, J or T after the pump head code designation to order pump heads assembled with

other than standard seals.

4. Ceramic cylinder liners should be used with ceramic piston only.

6

IN-Q431-09A

See Materials of Construction section in the Fluid Metering catalog for more information on wetted parts *316 Stainless Steel

cylinder cases accept ¼ NPT male fittings.

When ordering specify: Piston Size Code + Material of Construction + Option Code (Q1+CKC+W = Q1CKC-W

*CF = Consult factory for details

CF CF CF CF

CF

CFCF

CF

Page 7

7

IN-Q431-09A

Q PUMP HEAD MODULE - PARTS PRICE LIST

PUMP HEAD REPAIR SERVICE

Should your FMI PUMP or PUMP SUBASSEMBLY need repairs, you should first contact the Customer Service

Department for a SERVICE SAFETY ASSURANCE FORM and a RETURN AUTHORIZATION NUMBER, you

may then ship it to us post-paid. You will be charged a flat service fee for each Pump Head Module returned plus

the cost of parts used and the postage required to return it to you. The Pump Head Module service fee includes

inspection, clean and test to agreed specifications and the replacement of Lip Seals and Gland Washer.

After examining a returned pump or subassembly by FMI Service Department, you will be requested to approve

the charges before repair work is started.

PARTS ORDERS

MINIMUM ORDER APPLIES FOR DOMESTIC or FOREIGN (Invoice price exclusive of shipping)

SHIPPING

Parts and repair orders will be shipped via United Parcel Service or U.S. Postal Service unless other

means are specified.

ALL PRICES ARE QUOTED IN U.S. DOLLARS, FOB SYOSSET, NY - Subject to change without no

tice.

For Additional Information Call - Toll Free 800-223-3388 or email us at: pumps@fmipump.com

* CERAMIC PISTONS & CYLINDER LINERS SOLD AS SETS ONLY

PART NO. DESCRIPTION

Q410-2 CARRIER

Q410-3 CARRIER STAINLESS STEEL

Q665 SPACER

R405-S CYL CASE, STAINLESS STEEL

R405-1S CYL CASE, SS, TEMP GLAND

R405-SAN CYL CASE, SANITARY STAINLESS STEEL

R405-SG CYL CASE, SS ISOLATION GLAND

R406-K GLAND NUT, FLUOROCARBON

R406-0K GLAND NUT, FLUOROCARBON 1/8” PISTON

R406-1K GLAND NUT, FLUOROCARBON 1/4” PISTON

R406-2K GLAND NUT, FLUOROCARBON 3/8” PISTON

R406-3K GLAND NUT FLUOROCARBON

R406-S CYLINDER NUT R405-S, R405-SAN

R407-0 CYLINDER LINER

R407-1 CYLINDER LINER

R407-2 CYLINDER LINER

R407-1C* CYLINDER LINER

R407-2C* CYLINDER LINER

R407-3C* CYLINDER LINER

R408-1A LIP SEAL, RULON AR 1/4”

R408-2A LIP SEAL, RULON AR 3/8”

R408-0J LIP SEAL, RULON J 1/8”

R408-1J LIP SEAL, RULON J 1/4”

R408-2J LIP SEAL, RULON J 3/8”

R408-1T LIP SEAL, TEFLON 1/4”

R408-2T LIP SEAL, TEFLON 3/8”

R408-3A LIP SEAL, RULON AR 1/2”

R408-3T LIP SEAL, TEFLON 1/2”

R409-0 GLAND WASHER, TEFLON 1/8”

R409-1 GLAND WASHER, TEFLON 1/4”

R409-2 GLAND WASHER, TEFLON 3/8”

R409-3 GLAND WASHER TEFLON 1/2”

PART NO. DESCRIPTION

R412-1 ADAPTER, S.S. 1/4 NPT TO 1/4” I.D. TUBE

R412-2 ADAPTER, S.S. 1/4 NPT TO 3/8” I.D. TUBE

R412-0K ADAPTER, FLUOROCARBON 1/8” I.D. TUBE

R412-1K ADAPTER, FLUOROCARBON 1/4” I.D. TUBE

R412-2K ADAPTER, FLUOROCARBON 3/8” I.D. TUBE

R412-5K ADAPTER, FLUOROCARBON 1/4-28 THD

R412-6K ADAPTER, FLUOROCARBON 1/2” I.D. TUBE

R412-07 ADAPTER, S.S. 1/4” I.D. TUBE, SAN

R412-08 ADAPTER, S.S. 3/8” I.D. TUBE, SAN

R412-1T ADAPTER, TEFLON 1/4” I.D. TUBE, SAN

R412-2T ADAPTER, TEFLON 3/8” I.D. TUBE, SAN

R413 CYLINDER HEAD SEAL

R413-1 CYLINDER HEAD SEAL, R405-1K

R419 CYLINDER PORT SEAL, R405-S

R423-1C* PISTON

R423-2C* PISTON

R423-3C* PISTON

R423-0S PISTON

R423-1S PISTON

R423-2S PISTON

R479 LOW FLOW KIT (FITS R405-S)

R489 SPACER, SANITARY CYLINDER GROUP

R490-1 PORT SLEEVE, SANITARY CYLINDER GROUP

R520-1T ADAPTER, TEFLON 1/4” O.D. STRAIGHT, SAN

R520-2T ADAPTER, TEFLON 3/8” O.D. STRAIGHT, SAN

H476-K SML TUBE ADAPTER SET, 1/8” O.D. (OPTL)

110017-10 SCREW, SKT HD CAP 1/4-20 X 5/8”

110311 NUT, SQUARE 1/4-20

110348-P SAN PORT NUT, PLASTIC

110348-S SAN PORT NUT, STAINLESS STEEL

110384-K FERRULE NUT 1/4, KYNAR

110384-T FERRULE NUT 1/4”, TFE

110847-01 BARBED FITTING 10-32 UNC-2B 1/8” ID TUBING

200182-01 CYL CASE, SS HIGH TEMP GLAND

500074 LIP SEAL INSTALLATION TOOL,1/8”

500071 LIP SEAL INSTALLATION TOOL,1/4”

500080 LIP SEAL INSTALLATION TOOL,3/8”

500081 LIP SEAL INSTALLATION TOOL,1/2”

Please

call for Pricing

Please

call for Pricing

Page 8

8

IN-Q431-09A

FMI MODEL Q PUMPS

PARTS IDENTIFICATION SHEET Q431-05

Page 9

9

IN-Q431-09A

FMI MODEL Q PUMPS

PARTS IDENTIFICATION SHEET Q431-05

IMPORTANT!

WHEN ORDERING REPLACEMENT PARTS,

PLEASE MENTION MODEL & SERIAL NUMBERS OF PUMP ON WHICH THEY WILL BE

USED.

FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION CALL

TOLL FREE 800-223-3388 or

516-922-6050 / FAX 516-624-8261

email: pumps@fmipump.com

110522/200635

IVSP1 PUMP DRIVE MODULE

Special order

Page 10

General Description

The V300 Stroke Rate Controller provides precision flow control for FMI variable speed "V" Series

pumps. The V300 accomplishes this by varying

the pump stroke rate from 5% to 100% of the

drive’s rated speed range of 90 to 1800 Strokes

per Minute (SPM) or 5-50 strokes. The complete

pump system consists of the V300 Controller and

a variable speed "V" Series Pump. The V300 and

pump are connected via a single cable (standard

length is 4 meters while optional extension cables

up to 20 meters are readily available).

The pump is comprised of a 90 volt DC pump drive

module (PDM) with integrally mounted pump head

module (PHM), and is available in two configurations, QV and RHV, to accommodate FMI's full

range of pump head sizes.

V300 Features:

• 3 1/2 Digit LCD displays percent of Flow/Speed.

• Selectable Manual or Analog flow rate control.

• Manual setting of flow rate with 0.1%

adjustability

• Analog Input selectable 4-20 mA, 0-5 VDC, and

0-10 VDC input for communication with proces instrumentation.

• Start, Stop, and Reverse Flow while maintaining

flow settings.

• Current fold back eliminates stalled motor/ electronics damage.

• Universal Power accepts 100-240 VAC 50/60 Hz

• Quick connections for power, analog input, and

pump modules.• Rugged, An odized Aluminum

Enclosure designed for bench-top or wall

mounting.

10

IN-Q431-09A

V300 STROKE RATE FOR

CONTROLLER

FOR

MODELS QV, Q2V, QVG50, & RHV

For more information refer to our W300 Instruction manual available at our website at www.fmipump.com under literature.

Page 11

11

IN-Q431-09A

PART NO. DESCRIPTION

Q421-1 BASE ASS’Y QP

Q421-3 BASE ASS’Y QB, QD,QV, QBG

Q421-4 BASE ASS’Y QSY

Q421-5 BASE ASS’Y QSYX

Q421-6 BASE ASS’Y QG, QVG50

Q421-7 BASE ASS’Y QDX

Q424 SPINDLE ASSEMBLY QP, QDX

Q447 BUSHING, FLOW CONTROL

Q454-3 FOLLOWER

Q464 STROKE LENGTH ADJUSTMENT KNOB

Q485 DIAL INDICATOR KIT

Q616 RETAINER ASSEMBLY

Q647 BASE MOUNTING KIT

Q662 TILT STAND KIT

R424-1 SPINDLE ASSEMBLY QD, QG, QB, QV, QVG

R424-6 SPINDLE ASSEMBLY QSY, QSYX

R475 FOOT QSYX

P56C FACE MOTOR ADAPTER KIT

V109 MOTOR ASSEMBLY QV

V109G MOTOR ASSEMBLY QVG50

110049 WASHER #8 INT. LOCK

110258 FOOT, RUBBER

110262 MOTOR, QD PUMP 115V, 60Hz

110262-2 MOTOR, QD PUMP 230V , 50/60 Hz

110286-6A MOTOR, QG 6 RPM 115V, 60Hz

110286-20A MOTOR, QG 20 RPM 115V, 60 Hz

110286-50A MOTOR, QG 50 RPM 115V, 60 Hz

110286-150A MOTOR, QG 150 RPM 115V, 60 Hz

110286-400A MOTOR, QG 400 RPM 115V, 60 Hz

110290-8 SCREW, SKT HD 8-32 X 1/2”

PART NO. DESCRIPTION

110290-10 SCREW, SKT HD #8-32 X 5/8”

110290-22 SCREW, #8-32 X 1 3/8”

110297-6 DRIVE SCREW , 8-32 X 3/8”

110306-1 MOTOR, QSY 115V, 60Hz

110306-2 MOTOR, QSY 230V, 50/60Hz

110314 WASHER, #10 INT. LOCK

110336-2 MOTOR 230 VAC 50/60Hz QSYX

110337-2 RESISTOR (110336-2 230V, 50/60Hz)

110338-2 CAPACITOR (110336-2 230V, 50/60Hz)

110355-1 MOTOR, 12 VDC QB

110373 DRIVE COUPLING

110376-16 BOLT, HEX HD 3/8 -16 X 1”

110417-4 STANDOFF, HEX 8-32 X 1/4Ó FEM.

110454 CAP NUT 8-32

110471 LOCK NUT 1/4-20

110491 WASHER, FLAT 1/4” STD

110505 WASHER, SHOULDER, NYLON

110506-8 SCREW, SKT HD CAP 10-32 X 1/2”

110509 ADAPTER, PC56C

110522 MOTOR, X-PROOF QDX 115/230 VAC 60 HZ

110542-6 SCREW, HEX HD NYLON 8-32 X 3/8”

110544 SPEED KNOB

110579 WASHER, FLAT 3/8”

110580 WASHER, LOCK INT. 3/8”

110608 SPRING AND BRUSH SET, QVG50

110609 BRUSH CAP , QVG50

110671-4 SCREW, SET 8-32 X 1/4”

110837-01 SPRING BRUSH SET 12 VDC - GRAY MOTOR

110838-01 SPRING BRUSH SET 90 VDC - GRAY MOTOR

110839-01 BRUSH CAP 12, 90 VDC - GRAY MOTOR

110877 SPACER

200635 Motor + Cable ASS’Y, 1/2HP,230 VAC

Q PUMP DRIVE MODULE - PARTS PRICE LIST

PUMP DRIVE REPAIR SERVICE

Should your FMI PUMP DRIVE or SUBASSEMBLY need repairs, you should first contact the Customer

Service Department for a RETURN AUTHORIZATION NUMBER; you may then ship it to us post-paid.

You will be charged a flat service fee for each Pump Drive Module or subassembly returned plus the

cost of parts used and the postage required to return it to you.

After examining a returned pump or subassembly by FMI Service Department, you will be requested

to approve the charges before repair work is started.

PARTS ORDERS

MINIMUM ORDER APPLIES FOR DOMESTIC or FOREIGN (Invoice price exclusive of shipping)

SHIPPING

Parts and repair orders will be shipped via United Parcel Service or U.S. Postal Service unless other

means are specified.

ALL PRICES ARE QUOTED IN U.S. DOLLARS, FOB SYOSSET, NY - Subject to change without

notice.

For Additional Information Call - Toll Free 800-223-3388 or email us at: pumps@fmipump.com

Please

call for Pricing

Page 12

Continued from page 3

j) Place head seal components R413 and R489

into the head end of CYLINDER CASE R405SAN, apply CYLINDER NUT R406-S..

k) Wrench tighten each PORT NUT 110348-P 1/6

turn.

l) Wrench tighten each CYLINDER NUT R406-S

1/2 turn, piston end first.

18. PISTON SEAL REPLACEMENT (please see

para 5.) When R408 SEALS are replaced, the

following procedure should be followed: (please

see figs. 3,4)

a) Place GLAND NUT R406 and GLAND

WASHER R409 on PISTON ASSEMBLY R423.

b) Place the lip seal installation tool over the end

of the piston. Slide the tool until piston is seated

in tool. (See lip seal insertion tool table bellow).

c) First “Form” lip of lip seal by gently placing a

lip seal R408 on tool, lip side last. Carefully rotate the seal on the tool while sliding the seal

over the tool’s neck to avoid damage to the lip.

Then remove seal and reverse lip direction

(FIG.3)

d) Gently place one “formed” LIP SEAL R408 on

piston, lip side first, carefully rotating the seal on

the tool until it is past the tool and on the piston

e) Gently place one LIP SEAL R408 on piston,

lip side last. Carefully rotate the seal on the tool

to avoid damage to the lip while passing over the

tool to the piston (fig. 4).

f) Remove installation tool from the piston.

g) Insert piston into cylinder approximately one

inch.

h) Apply GLAND NUT R406 to cylinder threads,

seat gland nut, then tighten to 1/3 turn maximum.

19. PISTON SEAL SETTING. After installing

new

lip seals (part R408) in pump head it is recommended that the seals be set (formed in place)

by fluid pressures generated by pump action. To

accomplish this:

a) Operate the pump spindle clockwise for 10 or

20 strokes at maximum setting, handling water

(left to right mode facing pump head) with suction

line blocked or pinched off. This will create a

vacuum in the pump head, permitting atmospheric pressure to shape the outer seal member

tightly around the piston.

b) Reverse the pumping direction (pump head

angle reversal) and intermittently block the line

leading from the left hand port. This will generate

pressure in the seal area of the pump head,

causing the inner seals to form intimately around

the piston.

12

IN-Q431-09A

WHEN ORDERING REPLACEMENT PARTS PLEASE MENTION MODEL AND SERIAL NUMBERS OF

THE PUMP ON WHICH THEY WILL BE USED.

Record your Model and Serial Numbers below. This will be useful when ordering replacement parts.

PUMP HEAD MODULES (PHM) PUMP DRIVE MODULE (PDM)

PHM MODEL NUMBER PHM SERIAL NUMBER PDM MODEL NUMBER PDM SERIAL NUMBER

_____________________ QB__________________ _____________________ QA__________________

_____________________ _____________________ _____________________ ____________________

_____________________ _____________________ _____________________ ____________________

_____________________ _____________________ _____________________ ____________________

PLEASE NOTE:

Pistons and cylinders are dimensionally mated. For most satisfactory performance, they should be ordered

as mated sets.

Loading...

Loading...