Page 1

®

EPSON

LX-86

TM

PRINTER

User's Manual

Page 2

FCC COMPLIANCE STATEMENT

FOR AMERICAN USERS

This equipment generates

used properly, that is, in strict accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions,

may cause interference to radio and television reception. It has been type tested and

found to comply with the limits for a Class B computing device in accordance with

the specifications in Subpart J of Part 15 of FCC rules, which are designed to

provide reasonable protection against such interference in a residential installation.

However, there is no guarantee that interference will not occur in a particular

installation. If this equipment does cause interference to radio or television

reception, which can be

is encouraged to try to correct the interference by one or more of the following

measures:

-Reorient the receiving antenna

-Relocate the printer with respect to the receiver

-Plug the printer into a different outlet so that printer and receiver are on

different branch circuits.

If necessary, the user should consult the dealer or an experienced radio/ television

technician for additional suggestions. The user may find the following booklet

prepared by the Federal Communications Commission helpful:

“How to Identify and Resolve Radio-TV Interference Problems. ”

This booklet is available from the U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington

DC

20402.

Stock No.

and

uses radio frequency energy and if not installed and

determined by turning the equipment off and on, the user

004-000-00345-4.

WARNING

The connection of a non-shielded printer interface cable to this printer will

invalidate the FCC Certification of this device and may cause interference levels

which exceed the limits established by the FCC for this equipment. If this

equipment has more than one interface connector, do not leave cables connected

to unused interfaces.

Apple is a registered trademark of Apple Computer, Inc.

Applesoft is a trademark of Apple Computer, Inc.

Centronics is a registered trademark of Centronics Data Computer

Corporation.

Epson is a registered trademark of Seiko Epson Corporation.

LX-80

is a trademark of Epson America, Inc.

IX-86 is a trademark of Epson America, Inc.

IBM is a registered trademark of International Business Machines

Corporation.

Microsoft is a trademark of Microsoft Corporation.

NOTICE:

l

All rights reserved. Reproduction of any part of this manual in any form

whatsoever without EPSON’s express written permission is forbidden.

l

The contents of this manual are subject to change without notice.

l

All efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy of the contents of this

manual. However, should any errors be detected, EPSON would greatly

appreciate being informed of them.

l

The above notwithstanding, EPSON can assume no responsibility for any

errors in this manual or their consequences.

© Copyright 1986 by SEIKO EPSON CORPORATION

Nagano, Japan

Page 3

Contents

List

of Figures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . , . . . . .

vii

List of Tables. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Introduction

LX-86 Features

About This Manual

1

Setting Up Your LX-86 Printer

Printer Parts..

Printer Location

Paper Feed Knob Installation.

Ribbon Installation

Ribbon Replacement

................................

..............................

..........................

.................

..............................

.............................

..................

..........................

.........................

Paper Loading...............................

Control Panel

Lights

...............................

...................................

Buttons..................................

Test Pattern.

Connecting the LX-86 to Your Computer

First Printing Exercise

SelecType . . . . . . . . . . . .

2

SelecType Operation . . .

Turning SelecType on .

Selecting typestyles. . .

SelecType exercise . . . .

SelecType Tips . . . . . . . .

................................

.........

.........................

......

. . . .

. . . .

. . . .

. . . . . . . .

. . . .

. . . .

. . . *

. . . .

. . . .

. . . .

. . . .

......

......

......

......

......

. . .

. . .

. . .

. . .

. . .

Viii

1

1

2

3

3

4

4

5

8

9

10

11

11

12

13

14

15

15

15

16

17

19

Elements of Dot Matrix Printing

3

The Print Head

Bidirectional Printing.

Changing Pitches

NLQ Mode

4

Printer Control Codes

ASCII Codes

ESCape Code

Printer Codes

Embeddedcodes

Inserted codes.

.............................

........................

............................

.................................

........................

................................

...............................

...............................

..........................

............................

Programming Languages

................

......................

21

21

22

22

24

27

27

28

29

30

30

31

iii

Page 4

IX-86 Features

5

Demonstration Programs

Pica Printing.

Changing Pitches

Cancelling Codes

Resetting the Printer

Pitch Comparison.

Near Letter Quality Mode

......................

..............

.......................

....................

....................

.................

...................

.............

.......

.......

.......

.......

.......

.......

.......

.......

33

33

34

35

35

36

36

37

Print Enhancements and Special Characters

6

Bold Modes

Emphasized mode

Master program

Double-strike

Double-width Mode.

Mode Combinations.

Italic Mode..

Underline Mode

Master Select.

Superscript and Subscript

Special Characters.

................................

.........................

...........................

.............................

.........................

.........................

...............................

.............................

...............................

.....................

...........................

Epson character graphics set

International characters

Graphics character set.

Page Formatting

7

Margins

....................................

Justification with NIQ

Skip Over Perforation

Line Spacing

Paper-Out Sensor

User-Defined Characters

8

.............................

................................

............................

.....................

......................

........................

.........................

......................

Defining Your Own Characters

Designing Process.

First definition program.

Running the program.

...........................

....................

......................

Second definition program

Running the program.

Defining NLQ Characters.

NIQ grid

................................

......................

.....................

First NLQ definition program

Second NLQ definition program

.......

..................

.................

..................

................

..............

39

39

39

40

41

42

43

43

44

45

47

47

47

48

51

53

53

54

55

55

57

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

65

68

69

iv

Page 5

Introduction to Dot Graphics

9

Dot Patterns

Print Head

................................

.................................

..................

Graph&Mode ..............................

Pin Labels

First Graphics Program.

Multiple-Line Exercise

Density Varieties.

Reassigning Code

Column Reservation Numbers

WIDTH Statements

Design Your Own Graphics

Graphics Programming Tips

..................................

.......................

........................

............................

............................

..................

..........................

....................

...................

Semicolons and command placement

String variables

Graphics and low ASCII codes

............................

................

Appendixes

..........

71

72

73

73

74

76

76

78

79

79

80

81

84

84

86

87

A

LX-86 Characters

Epson Character Graphics

B

Commands in Numerical Order

Control Key Chart

C

Command S

Near Letter Quality

Character Width

Print Enhancement

Mode and Character Set Selection

Special Printer Features

............................

.....................

......

...........................

ummary

.........................

..........................

............................

..........................

...............

.......................

Line Spacing ................................

Forms Control.

Page Format..

User-defied Characters

Dot Graphics

Miscellaneous Codes.

The DIP Switches

D

E

Using the Optional Tractor Unit

Printer Location

Tractor Unit Installation

Loading Continuous Paper.

..............................

..............................

.......................

...............................

.........................

............................

................

.............................

.......................

....................

.........

:

A-l

A-3

B-l

B-4

c-1

c-1

c-2

c-4

C-6

c-9

c-11

c-13

C-16

c-19

c-20

C-23

D-l

E-l

E-l

E-2

E-4

V

Page 6

F

Troubleshooting and Advanced Features

Problem / Solution Summary

Setting print styles

Tabbing

Graphics

.................................

.................................

Paper-out sensor

.........................

...........................

Beeper Error Warnings

Data Dump Mode

Coding Solutions

...........................

............................

Solutions for Specific Systems

Applesoft BASIC solutions.

Apple II solutions.

IBM-PC solutions

.........................

..........................

...................

........................

..................

..................

..........

F-l

Fl

F-l

Fl

Fl

F3

F-3

F-3

F5

F6

F6

F-6

F7

Printer Maintenance.

G

Always

....................................

Now and Then

Rarely

Technical Specifications

H

Printing

.....................................

.....................

Character size

Characters per line

........................

Paper

Printer.

......................

Dimensions and Weight.

Environment.

Interface

I

The Parallel Interface

.....................

Data Transfer Sequence

Interface timing

Signal relationships

.

........

................

..............................

.........

...............

...........

........

.................

...........

.........

.............

..........

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

...... ......

. . . . . .

. . . . , .

. . . . . .

. . . . . .

. . . . . . H-2

. . . . . *

. . . . . .

. . . . . *

. * . . . .

......

......

......

G-l

G-l

G-l

G-l

H-l

H-l

H-l

H-2

H-2

H-2

H-3

H-3

I-l

I-3

I-3

I-3

vi

Page 7

List

of

Figures

l-l Printer parts

l-2

Paper feed knob installation

l-3

Ribbon cassette.

l-4 Print head assembly

l-5

Ribbon cassette installation

l-6 Ribbon placement

l-7 IX-86 ready for paper loading

l-8 Control panel

l-9

Test patterns

l-10 Cable connection

2-l Turning SelecType on . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3-l

A capital T

3-2

The three pitches of the LX-86

3-3

IX-86 dot matrix characters

6-l Emphasized and standard print.

6-2

Double-strike and standard print.

6-3

Double-width and standard characters

6-4

Italic and pica.

6-5

The underline mode

6-6 Special graphics characters

7-1

Standard line spacing. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

................................

...................

.............................

..........................

....................

...........................

..................

...............................

................................

............................

.................................

.................

....................

...

.......

.......

.......

.......

.......

.......

........

.......

......................

.................

.............

3

5

6

7

8

9

10

12

13

16

21

23

24

39

41

42

44

45

51

56

8-l Grid for designing draft characters

8-2

Correct and incorrect designs

8-3

Design for character

8-4

Using the bottom eight rows

8-5

Grid for NLQ characters

8-6

Data numbers for one column

8-7

Arrow design and data numbers

9-l Pin labels

9-2

Calculating numbers for pin patterns

9-3

Designing in different densities

9-4

Arrow design

9-5

First line of arrow figure

9-6

Result of incorrect program

9-7

Pin patterns of incorrect program

D-l DIP switch location

..................................

..........................

...............................

..........................

...................

...................

.......................

..................

.......................

....................

..............

................

............

.................

...............

60

61

62

63

66

67

68

75

75

81

82

82

84

85

D-l

vii

Page 8

Continuous paper with printer stand.

E-l

Continuous paper without stand

E-2

Tractor placement.

E-3

E-4

Paper separator and paper guide

Tractor release levers

E-5

Pin feed holder adjustment

E-6

Open pin feed cover

E-7

Top of page position.

E-8

...........................

..........................

..........................

.........................

............

................

................

....................

E-l

E-2

E-2

E-3

E-4

E-5

E-5

E-6

I-l

Parallel interface timing

.......................

List of Tables

2-l

SelecType modes

Summary of LX-86 pitches.

5-1

6-1

International characters in NLQ mode.

6-2

International characters in draft mode.

International characters in draft italic

6-3

Graphics modes

9-l

DIP switch functions

D-l

International DIP switch settings

D-2

Pins and signals

I-l

Signal interrelations

I-2

............................

.............................

.........................

.............................

..........................

....................

...........

...........

............

................

I-3

17

38

49

49

50

78

D-2

D-2

I-l, I-2

I-4

. . .

Vlll

Page 9

Introduction

The Epson IX-86

printer combines low price with the high quality

and advanced features formerly available only on more expensive

printers.

LX-86 Features

In addition to the high performance and reliability you’ve come

to expect from Epson printers, the LX-86 offers:

l Draft mode for quick printing of ordinary work

l Near Letter Quality mode for top quality printing

l Selection of typestyles with the control panel

l Fast printing (120 characters per second in draft pica)

l A variety of print styles, including Roman, italic, six widths,

and two kinds of bold printing

l User-definable characters so you can create and print your own

symbols or characters

l High-resolution graphics for charts, diagrams, and illustrations

l Easy paper loading

l Ribbon cassette for quick and clean ribbon changing

l Epson Standard Character Graphics set, which includes char-

acter graphics that are used on IBM@ and compatible

computers as well as international characters used by IBM

software. These characters are shown below:

1

Page 10

About This Manual

We’re not going to waste your time with unnecessary information,

but we won’t neglect anything you need to know about the Ix-86

and its many features.

You can read as much or as little of this manual as you wish. If you

have used printers before and have a specific program that you want

to use with the LX-86, a quick reading of the first chapter may be all

you need. If, on the other hand, you are new to computers and

printers, you will find this manual easy to follow and the LX-86 easy

to use. No matter what your background, if you want to learn about

and experiment with all the advanced features of the LX-86, the

information you need is here.

For a preview of what your LX-86 can do, look at the following

samples of a few of its typestyles.

*

NEAR LETTER QUALITY

NLQ standard

NLQ

*DRAFT MODE

Pica

Elite

Condensed

Italic

Underlined

Emphasized double-width

emphasized

ABCDEFGHIJKLMnopqrstuvwxyz

ABCDEFGHIJKLMnopqrstuvwxyz

ABCDEFGHIJKLMnopqrstuvwxyz

ABCDEFGHIJKLMnopqrstuvwxyz

ABCDEFGHIJKLMnopqrstuvwxyz

ABCDEFGHI.JKLMnopqrstuvwxyz

ABCDEFGHIJKLMnopqrstuvwxyz

2

Page 11

Chapter

1

Setting Up Your LX-86 Printer

Setting up your LX-86 printer is a simple matter of attaching two

parts, putting in the ribbon and paper, and connecting the printer to

your computer.

This chapter will have you printing a test pattern within fifteen to

twenty minutes and doing more complicated work not long after.

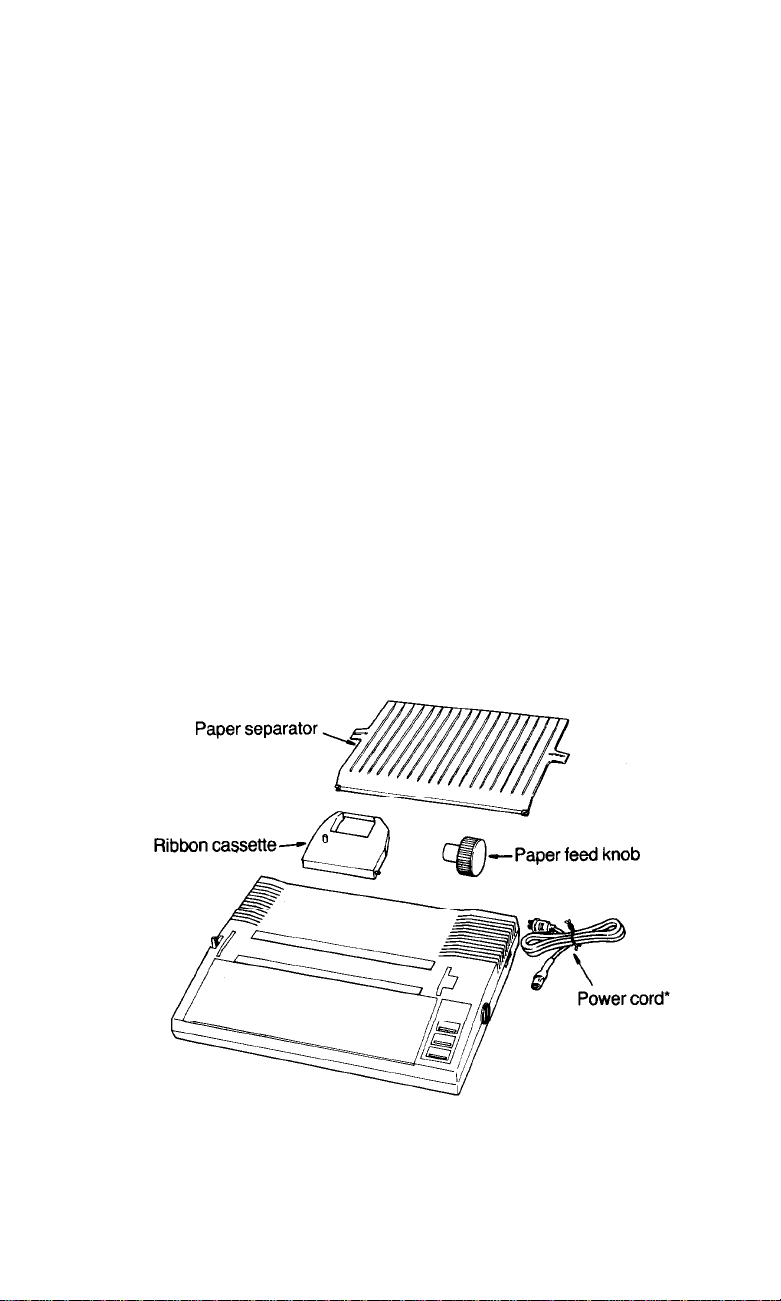

Printer Parts

First, see that you have all the parts you need. In addition to this

manual, the printer box should contain the items shown in Figure 1-l.

* In the United States, the printer is delivered with the power

cord attached.

Figure l-l. Printer parts

3

Page 12

In addition to the items in the box, you need a cable and possibly

an interface board. The cable connects the printer to your computer,

and the interface board is necessary only for those computers that

can’t use the LX-86’s Centronics® paralle1 interface. Your computer

manual or your dealer will tell you which cable you need and whether

or not you need a special interface.

Printer Location

Now that you have unpacked your printer, you should choose a

suitable location for it. The main requirement, of course, is that the

printer be close enough to your computer for the cable to reach. Also

remember the following:

l Use a grounded outlet, and do not use an adapter plug.

l Avoid using electrical outlets that are controlled by wall switches.

Accidentally turning off a switch can wipe out valuable information in your computer’s memory and disrupt your printing.

l Avoid using an outlet on the same circuit breaker with any large

electrical machines or appliances. These can cause disruptive power fluctuations.

l Keep your printer and computer away from base units for cordless

telephones.

l Protect the printer from direct sunlight, excessive heat, moisture,

and dust. Make sure that it is not close to a heater or other heat

source.

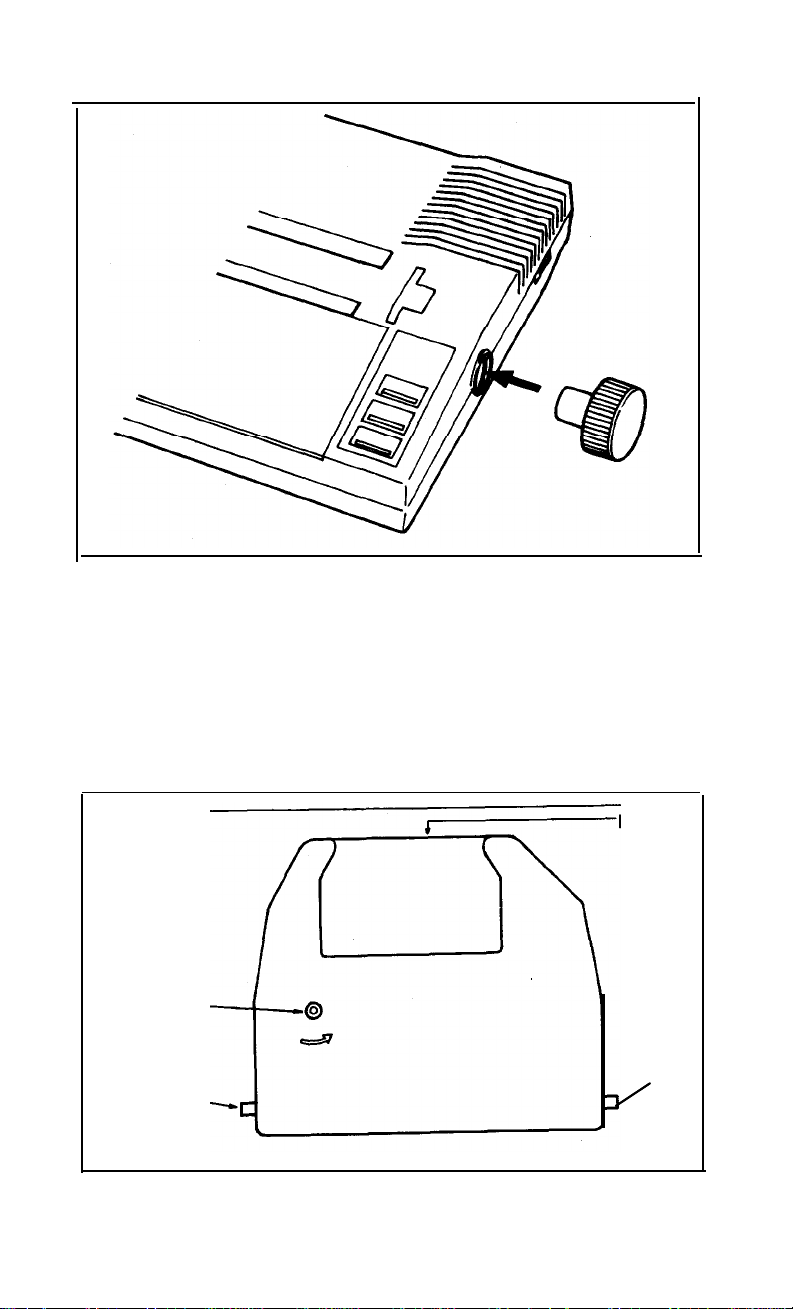

Paper Feed Knob Installation

Now that you have chosen where to set up your LX-86, the first

and simplest piece to install is the paper feed knob, which you use to

manually advance the paper-lust as you do on a typewriter. To

install the knob, merely push it onto the shaft found in the hole on the

right side of the printer. (See Figure l-2.) The shaft has one flat side

that must be matched with the flat side of the hole in the knob.

4

Page 13

Figure 1-2. Paper feed knob installation

Ribbon Installation

The LX-86 printer uses a continuous-loop, inked fabric ribbon,

which is enclosed in a cassette that makes ribbon installation and

replacement a clean and easy job. The parts of this cassette are labelled

in Figure

l-3.

Ribbon

Knob

Pin

Figure

l-3.

Ribbon cassette

Pin

5

Page 14

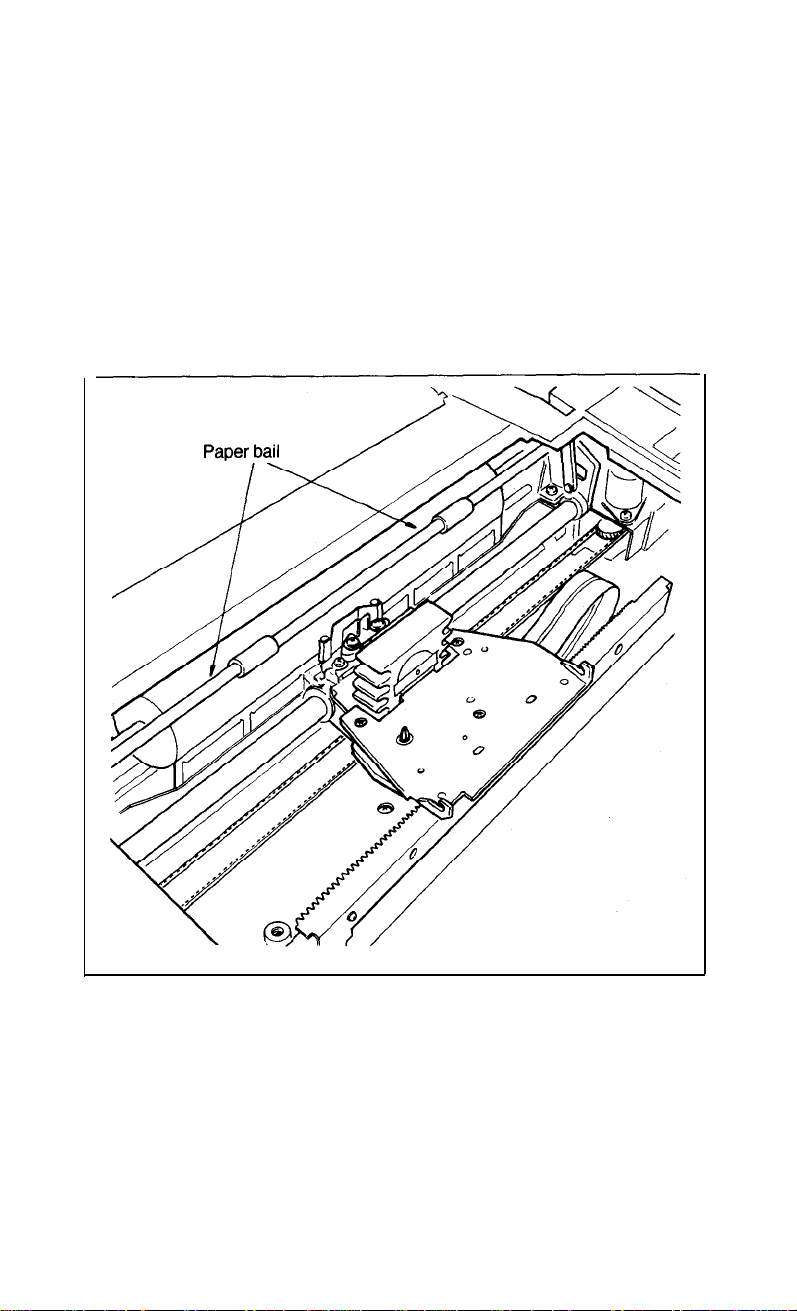

To install the ribbon, first open the lid at the front of the LX-86 so

that you can see the print head assembly shown in Figure

the assembly by hand to the center of the printer so that the other

parts of the printer will not get in your way. Also be sure that the

paper bail is against the black roller so it too will not be in your way.

Note: Moving the print head by hand when the printer is turned on

can harm the printer. Always be sure that the printer is turned

off before you move the print head.

l-4.

Move

Figure 1-4. Print bead assembly

6

Page 15

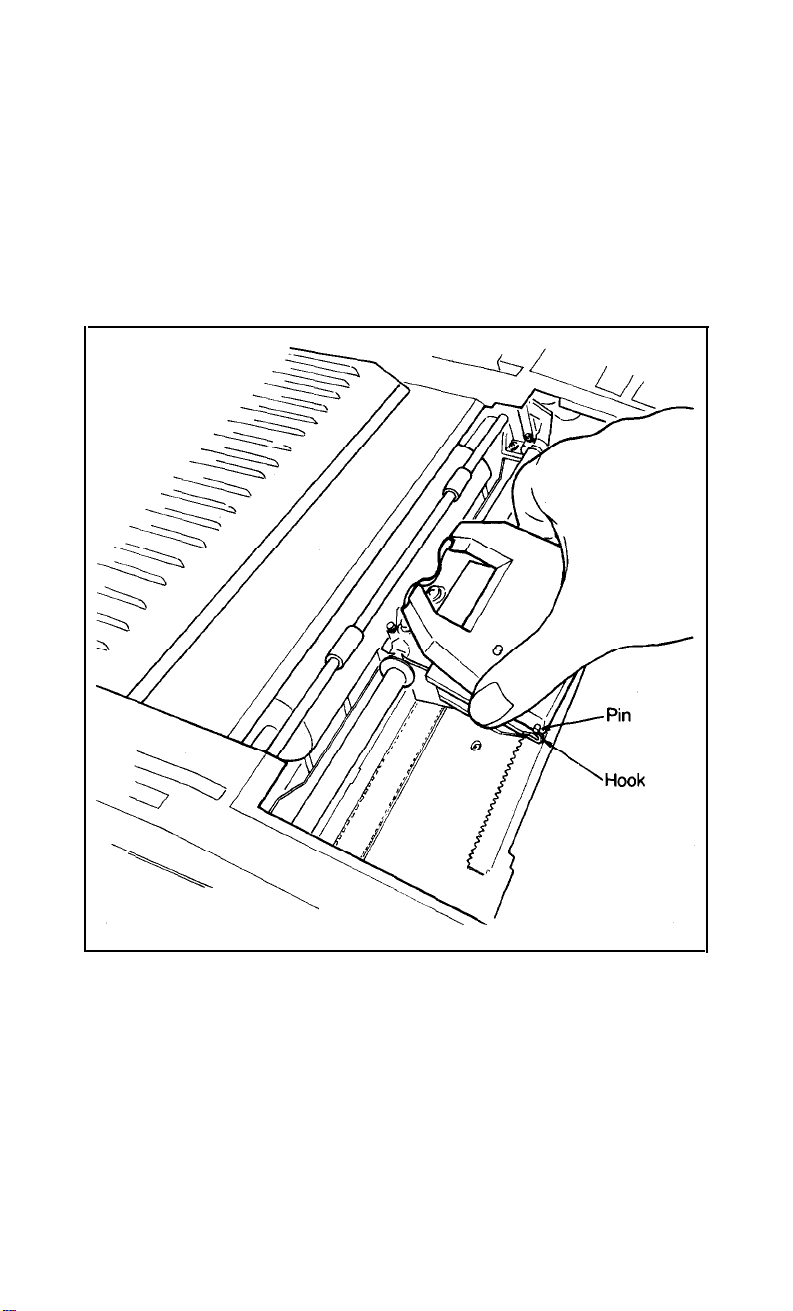

Then hold the ribbon cassette so that the small knob is on top and

the exposed section of ribbon is away from you. Insert the cassette in

its holder by first sliding the pins at the back of the ribbon cassette

under the small hooks on the holder. (See Figure l-5.) Then lower the

front of the cassette so that the exposed section of ribbon can fit

between the print head nose and the silver ribbon guide. Push down

until the cassette fits firmly in place.

Figure 1-5. Ribbon cassette installation

7

Page 16

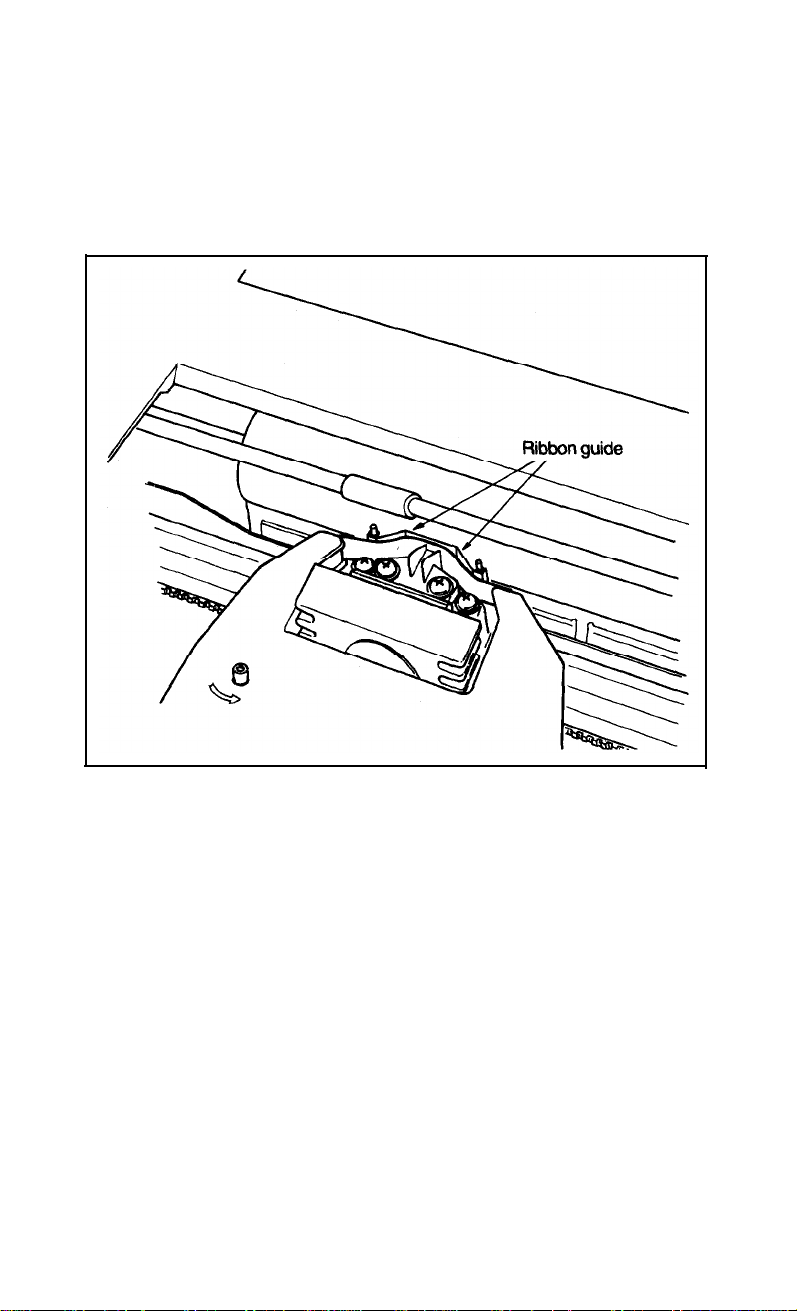

Now turn the knob on the cassette in the direction of the arrow to

tighten the ribbon. As you turn the knob, see that the ribbon slips

down into its proper place between the print head nose and the silver

ribbon guide (Figure l-6). If it doesn’t, guide it with a pen or a pencil.

Figure l-6. Ribbon placement

Ribbon Replacement

When your printing begins to become light and you need to re-

place the ribbon, lift the front of the cassette to remove it and then

follow the above instructions with a new cassette. If you have been

using your printer just before you change cassettes, be aware that the

print head becomes hot during use. Be careful not to touch it. Also

remember never to move the print head by hand when the printer is

turned on.

8

Page 17

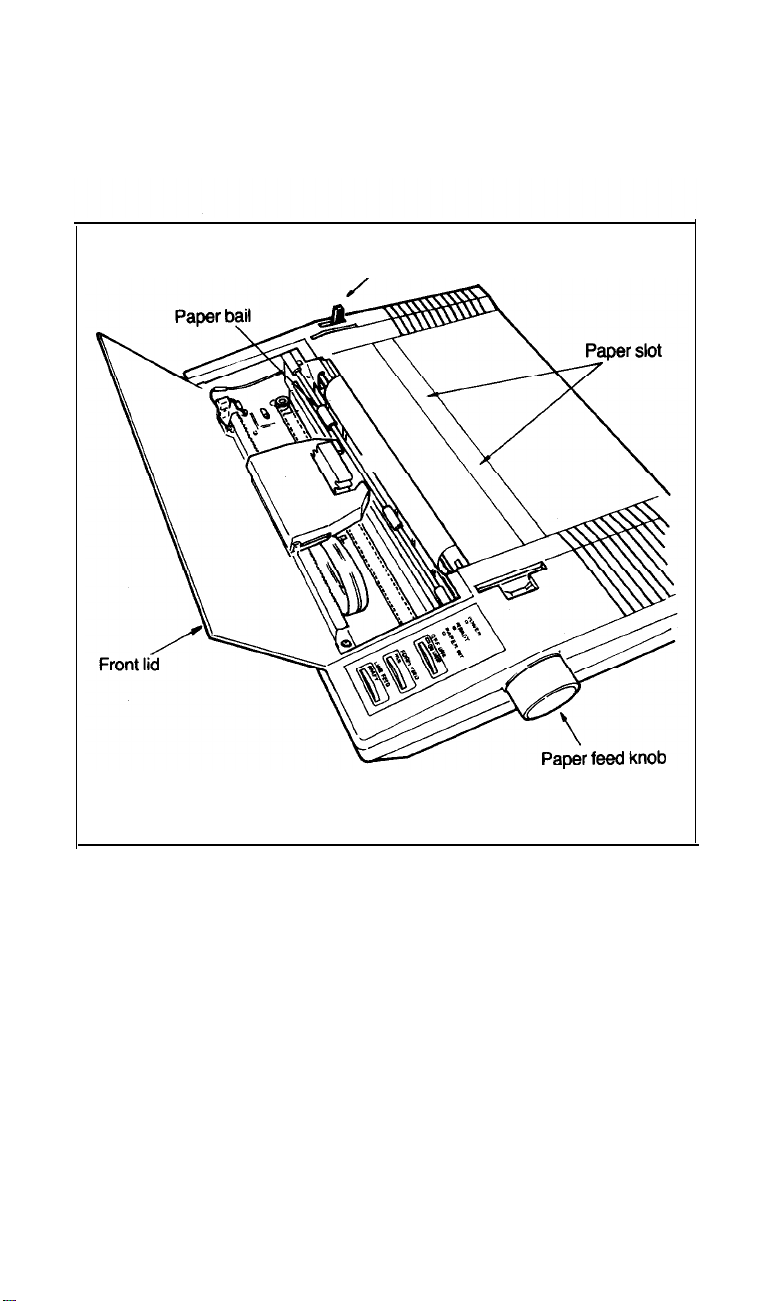

Paper Loading

Now put a sheet of paper in your LX-86 so you can test it. Figure

l-7 shows the names of the parts

that you need to know.

Friction lever

Figure l-7. LX-86 ready for paper loading

9

Page 18

See that the printer is turned off, open the front lid, and push the

friction lever back and the paper bail forward. Then move the print

head by hand to the center of the printer and feed the paper into the

paper slot in the top of the printer.

When the paper will not go any farther, turn the paper feed knob

to advance it as you would with a typewriter. Turn the knob until the

top of the paper is at least 3/4-inch above the ribbon guide. Then push

the paper bail against the paper. If the paper becomes crooked, pull

the friction-release lever forward, straighten the paper, and push the

friction lever back.

If you have the optional tractor unit for continuous pin-feed paper,

see Appendix E for instructions on its use.

Control Panel

Now that your paper is loaded, it is time to plug in the printer

and see what the buttons on the control panel do. First, see that

the power switch on the right side of the printer is off. Then plug

in the power cord. Now turn on the power switch and look at the

control panel.

10

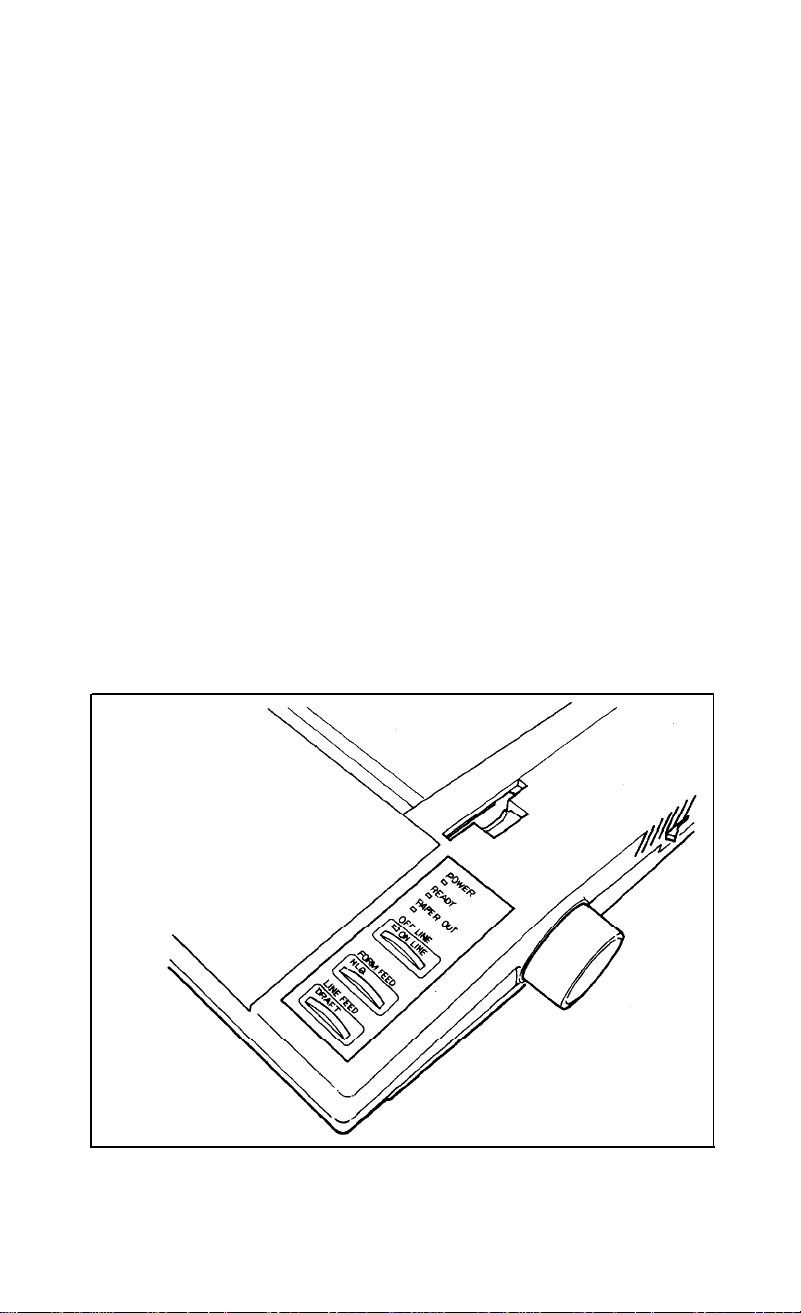

Figure l-8. Control panel

Page 19

There are three buttons and four indicator lights on the control panel.

Lights

l

The POWER light glows green when the power is on.

l

The READY light glows green when the printer is ready to accept data.

This light flickers somewhat during printing.

• The PAPER OUT light glows red to indicate that the printer is out of

paper or the paper is loaded incorrectly.

• The ON LINE light glows green when the printer can receive data.

Buttons

The buttons have several functions, including selecting draft or NLQ

(Near Letter Quality) printing. Draft is good for quick printing of

ordinary work, and NLQ has more fully-formed characters for final

copies or special purposes.

This is high-quality NLQ printing.

This is fast

l

ON LINE/OFF LINE. This button switches the printer between

draft

printing.

on-line and off-line status. When the printer is on line, the ON

LINE light glows and the printer is ready to accept data.

l FORM FEED/NLQ. When the printer is on line, pressing this

button turns on NLQ. When the printer is off line, this button

advances the paper to the top of the next page.

l LINE FEED/DRAFT. When the printer is on line, this button

turns on draft printing. When the printer is off line, this button

advances the paper one line at a time.

11

Page 20

Test Pattern

Now you’ll see your Lx-86 print something even though it’s not

connected to a computer yet. Make sure that your printer has paper in it

and that the power switch is off. Now, hold down the LINE FEED button

on the control panel while you turn the printer on with the power switch.

The Lx-86 will begin printing all the letters, numbers and other

characters that are stored in its ROM (Read Only Memory) for the draft

mode. When the printing starts, you can release the LINE FEED button;

the printing will continue until you turn the printer off or until the print

head gets near the end of the page. To see the same test in the NLQ (Near

Letter Quality) mode, turn the printer on while holding down the

FORM FEED button. Partial results of both tests are shown in Figure 1-9.

<Draft>

123456789 : <=>

23456789:;<=>

3456789:;<=>

456789:;<=>

56789:;<=>

6789:'<=> ?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[\]ˆ

789 : ;<=>

89:;<=>

9 : ;<=>

: ; <=>

?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[/]ˆ_`ab

;<=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQTRSTUVWXYZ[\]ˆ_’abc

<=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQTRSTUVWXYZ[\]ˆ._'

?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[\]ˆ_

?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[\]ˆ_`

?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[\]ˆ_`a

<NLQ>

123456789: ; <=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMOPQPSTUVWXY

23456789: ; <=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMHOPQRSTUVWXYZ

3456789: ; <=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[

456789: ; <=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[\

56789: ; <=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMHOPQRSTUVWXYZ[\]

6789: ; <=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[\]ˆ

789: ; <=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQESTUVWXYZ[\]ˆ89: ; <=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQESTUVWXYZ[\]ˆ_'

9: ; <=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMHOPQRSTUVWXYK[\]ˆ_'a

: ; <=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQESTUVWXYZ[\]ˆ_' ab

; <=>?BABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[\]ˆ

<=> ?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQESTUVWXYZ[\]ˆ ‘abed

?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXY

?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ

?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[

?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[\

?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[\]

abcd

’ abc

12

Figure l-9. Test patterns

Page 21

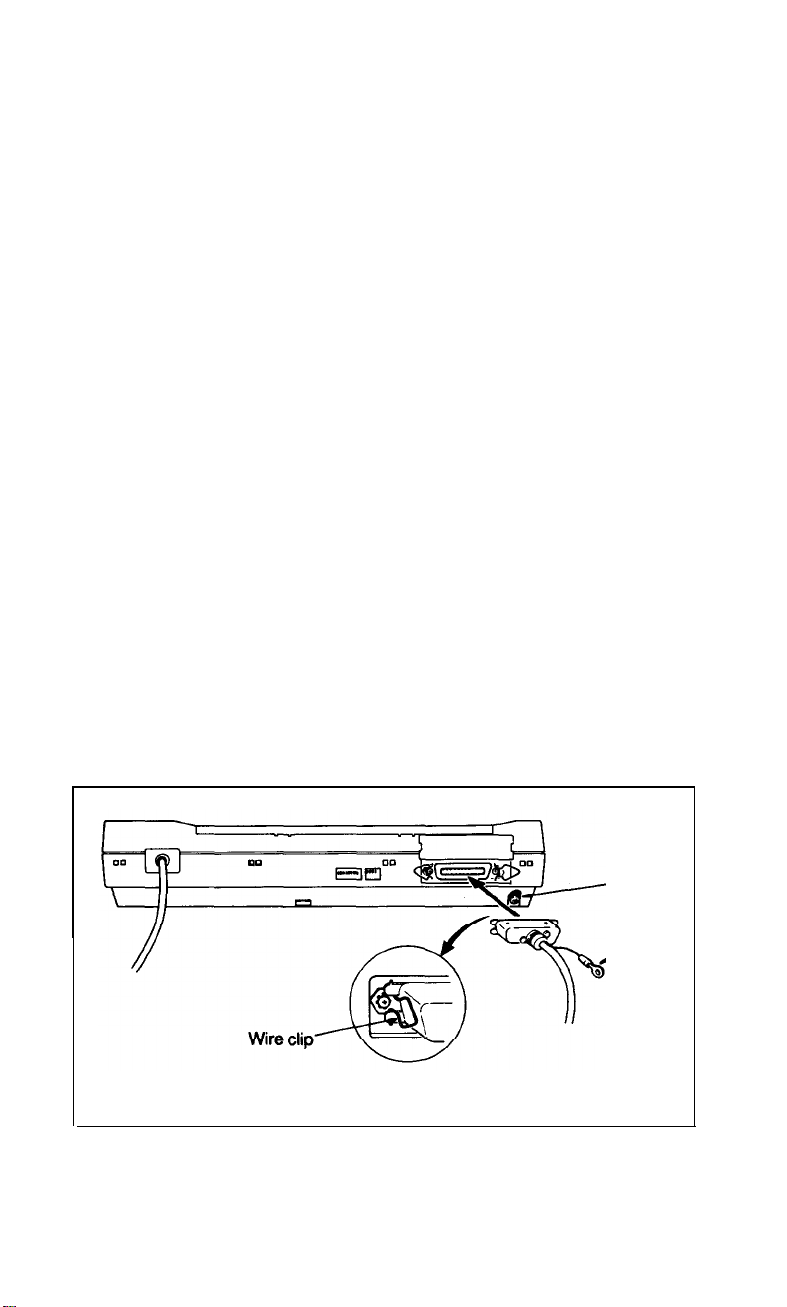

Connecting the LX-86 to Your Computer

Now that the test pattern has shown that your printer is working

well, it’s time to hook it up to your computer. It is best to have both

the printer and the computer turned off when you do this.

Remember that each computer system has its own way of com-

municating with a printer. If your computer expects to communicate

through a Centronics parallel interface, all you need is a cable. If your

computer requires any other kind of interface, you will also need an

interface board.

If you don’t know what a Centronics parallel interface is, your

computer manual or your dealer will tell you what you need. Then,

once you have plugged your printer cable into your printer and

computer, you will probably never think about interfaces again. (If

you do want the technical specifications, however, you can find them

in Appendix I.)

The first three steps in connecting your printer and computer are

shown in Figure l-10. Plug one end of your printer cable into the

cable connector of your LX-86 printer. The plug is shaped so that

there is only one way it will fit the connector. Now secure the plug to

the printer with the wire clips on each side of the connector. These

clips insure that your cable will not be loosened or unplugged

accidentally. If your cable has a grounding wire, fasten it to the

grounding screw below the connector.

Figure I-10. Cable connection

Grounding

screw

Grounding

wire

13

Page 22

Next connect the other end of the printer cable to your computer.

On most computers you can easily find the correct connector for the

printer cable, but if you are not sure, consult your computer manual

or your dealer.

First Printing Exercise

Now it is time to see something more interesting than the test

pattern from your LX-86 printer. Your next step depends upon what

kind of printing you plan to do. If you have a word processing or

other commercial software program, just load the program in your

computer, follow its printing instructions, and watch your Lx-86

print. If you plan to use your LX-86 for printing program listings,

load a program and use your computer system’s listing command

(LLIST for Microsoft

Note: If all the lines of your first printing exercise are printed on top

of each other, don’t worry. There is nothing wrong with your

printer. All you have to do is change the setting of a small

switch in the back of your printer. See the section on automatic line feeds in Appendix D.

TM

BASIC, for example).

14

Page 23

Chapter 2

SelecType

The LX-86’s SelecType feature can produce four special

typestyles:

This is emphasized printing.

This is

This is condensed printing.

This is in the elite mode.

SelecType Operation

Using SelecType is easy. You turn on SelecType and select a type-

style, then turn off SelecType and print.

Note: Each button has two names. For convenience, this chapter

uses the top names of the buttons.

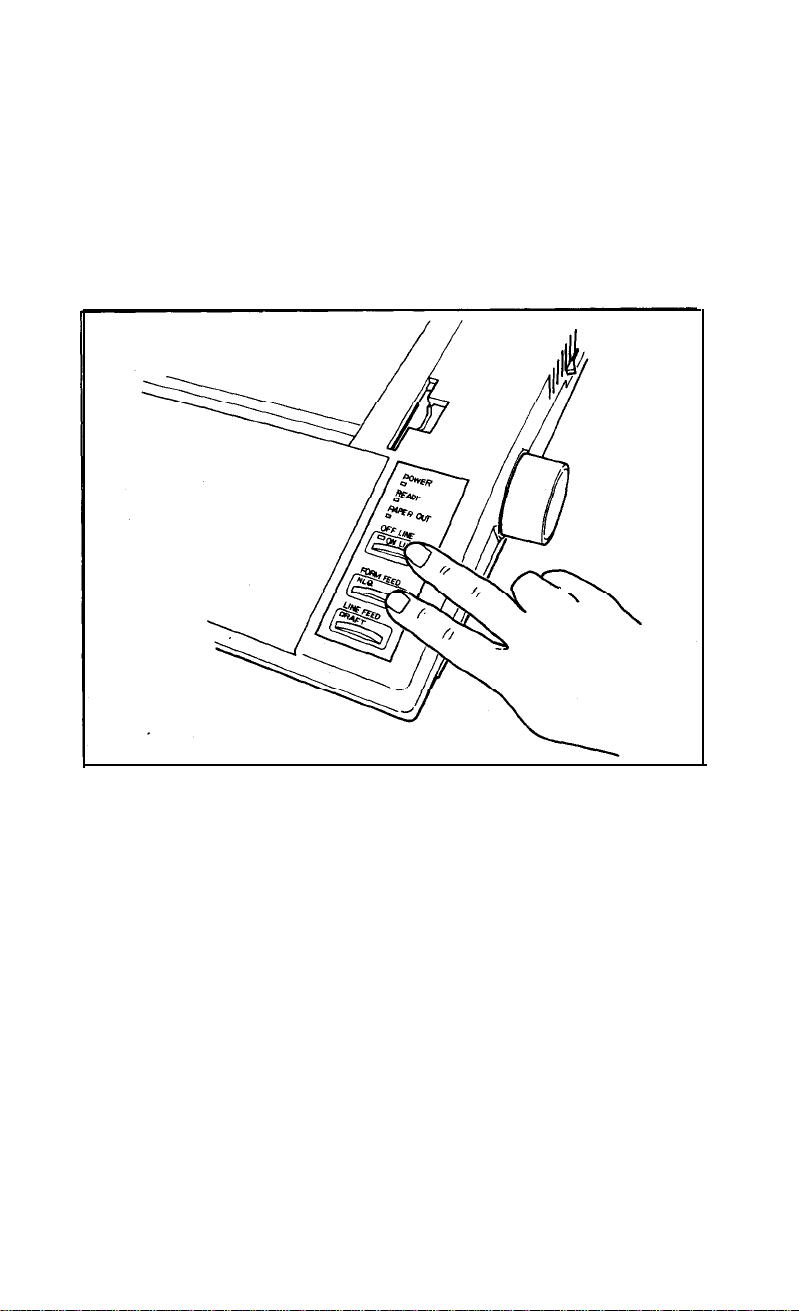

Turning SelecType on

1. Make sure that the printer is on and that the POWER, READY,

and ON LINE lights are all on.

in the double-strike mode.

2.

Press both the OFF LINE and FORM FEED buttons at the same

time, as illustrated in Figure 2-l. Hold them down for at least a

second, then release them.

15

Page 24

Note: If the printer beeps twice before you release the buttons,

you have pressed the FORM FEED button before the OFF

LINE button instead of at the same time and the LX-86 is

in the NLQ mode. Press the OFF LINE button to put the

printer back on line and press the DRAFT button if you do

not want NLQ. Then press both the OFF LINE and FORM

FEED buttons to turn on SelecType.

Figure 2-1. Turning SelecType on

When you release the OFF LINE and FORM FEED buttons,

the LX-86 signals in three ways that SelecType is on.

• The printer beeps.

l

The READY light turns off.

• The ON LINE light begins flashing.

Selecting typestyles

In SelecType, each button has a function:

• OFF LINE selects typestyles.

*FORM FEED sets the styles.

•LINE FEED turns SelecType off.

16

Page 25

After turning on SelecType, follow these three steps to select

a typestyle:

1. Find the typestyle you want in Table 2-1.

Table 2-l. SelecType modes

Mode

1

2

3

4

Emphasized

Double&trike

condensed

Elite

Typestyle or Function

ABCDEFGHIJKLMnopqrstuvwxyz

ABCDEFGHIJKLMnopqrstuvwxyz

ABCDEFGHIJKLMnopqrstuvwxyz

ABCDEFGHIJKLMnopqrstuvwxyz

2. Press the OFF LINE button the number of times indicated in

the mode column. Be sure that the printer beeps each time you

press the OFF LINE button.

3. Press the FORM FEED button to set the typestyle.

4. Press the LINE FEED button to turn SelecType off. The control

panel returns to its normal functions, but the printer is off-line.

5. Press the OFF LINE button, and you are ready to print.

SelecType exercise

You don’t need to know anything about programming for this

exercise because it is merely for practice. If you would rather not use

BASIC, use your word processing or business program to create a

short file or document of the type you will usually print.

If you do want to use BASIC for this exercise, simply turn on your

computer and printer and load BASIC. Then type the short

program listed below. Only the words inside the quotation marks

are printed. You can put anything you want there. (If your version of

BASIC does not use LPRINT, consult your BASIC manual.)

10 LPRINT “This is an example”

20 LPRINT ” of LX printing. ”

17

Page 26

Now, run the program by typing RUN and pressing RETURN, or

print your file or document by following the printing instructions of

your software. The LX-86 will print your example in standard singlestrike printing, as shown below:

This is an example

of LX printing.

Now that you have created a sample, follow these steps to print it

in condensed mode:

1.

See that both the ON LINE and READY lights are on.

2. Press the OFF LINE and FORM FEED buttons at the same time,

then release them. You hear a beep to signal that SelecType is on.

3. As shown in Table 2-1, the code for condensed is three. Therefore,

press the OFF LINE button three times. (Remember to make sure

you hear a beep each time you press the OFF LINE button when

you are in SelecType mode.)

4. Now that you have selected the condensed mode, push the

FORM FEED button once to set it.

5. Push the LINE FEED button once to return the panel to its standard operation.

6. Press the OFF LINE button so the IX-86 is ready to print.

Now you have set the LX-86 to print in condensed mode. Print

your sample once more. It should appear in condensed mode just as

you see below:

This is an example

of LX printing.

Turn off your printer to cancel the condensed setting, and-

if you wish-try this exercise with other modes.

Note: Some applications programs are designed to control all

typestyle functions. These programs cancel all previous

typestyle settings by sending an initialization signal before

printing. Because this signal cancels SelecType settings, you

will have to use the program’s print options function

instead of SelecType to select your typestyles. Therefore, if

SelecType does not work with a particular applications

program, consult its manual on how to select typestyles.

18

Page 27

SelecType Tips

Once you have learned the simple technique for controlling print

styles with SelecType, you can use it whenever you wish.

You should be aware of a few restrictions, however.

l

SelecType is designed to control the printing of an entire file or

document, not an individual line or word.

l If you are using the NLQ mode, remember that the following

SelecType modes are not available in NLQ: condensed, double-

strike, and elite.

l

If there are print codes in the document or file you are printing,

those codes will override your SelecType settings. This seldom

happens, since you usually won’t use SelecType with files that have

such codes, but if your IX-86 follows the SelecType instructions for

only part of a document, print codes in the document may

conflict with the SelecType modes.

l

After you turn on a mode with SelecType, it stays in effect until the

printer is turned off. If, for example, you use SelecType to print a

document in emphasized, anything you print after that will be

emphasized unless you first turn the printer off and back on.

19

Page 28

Chapter 3

Elements of Dot Matrix Printing

This chapter is for those of you who want to know something

about how your printer works. It’s a simple, non-technical explanation of the basics of dot matrix printing that will help you understand

some of the later chapters.

The Print Head

The IX-86 uses a print head with nine pins or wires mounted

vertically. Each time a pin is fired, it strikes the inked ribbon and

presses it against the paper to produce a dot. This dot is about 1/72nd

of an inch in diameter. The size varies slightly depending upon the age

of the ribbon and the type of paper used. As the head moves horizontally across the page, these pins are fired time after time in different

patterns to produce letters, numbers, symbols, or graphics.

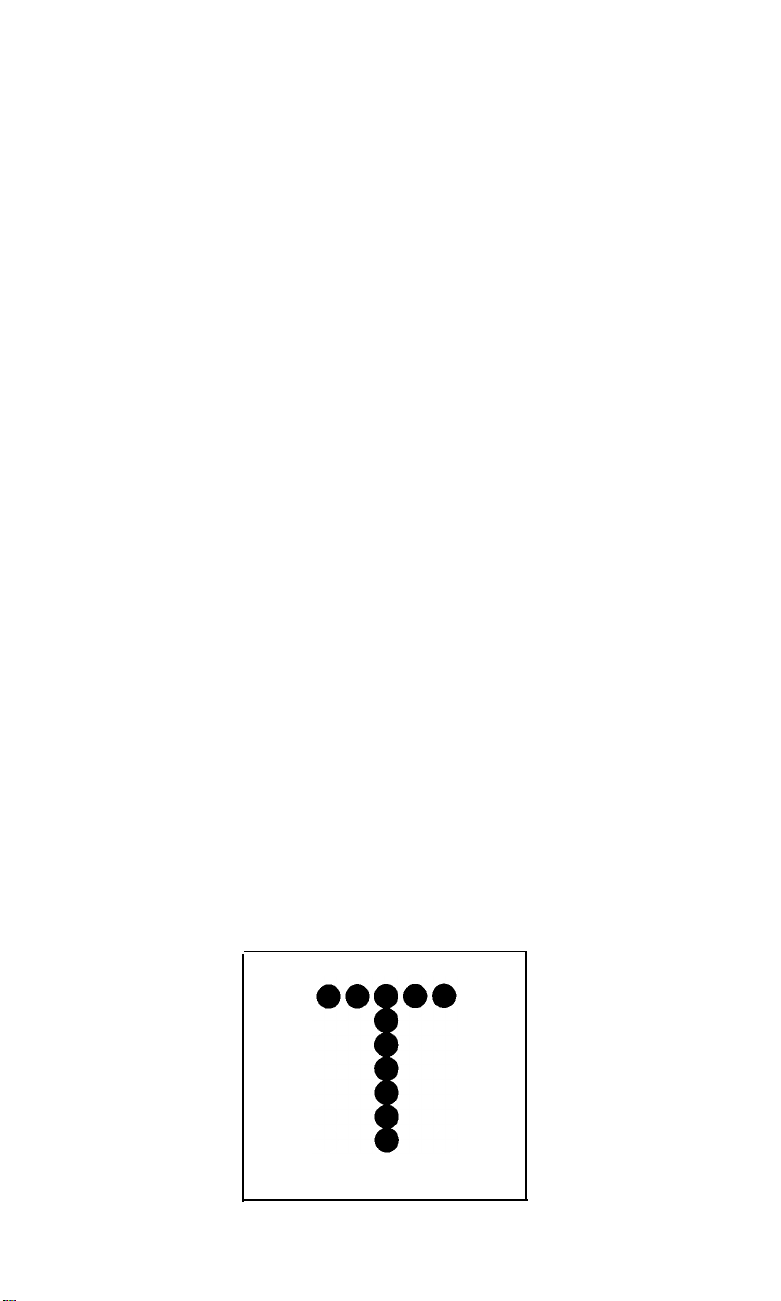

For example, to print a pica capital T, the head fires the top pin,

moves 1/60th of an inch, fires the top pin again, moves 1/60th of an

inch, fires the top seven pins, moves 1/60th of an inch, fires the top

pin, moves another 1/60th of an inch, and fires the top pin once more

to finish the letter.

Figure 3-l. A capital T

21

Page 29

Bidirectional Printing

In nearly all of our discussions in this manual, we describe the

action of the LX-86 print head as moving from left to right, as a

typewriter does. During its normal operation while printing in the

draft mode, however, the LX-86 prints bidirectionally. That is, the

print head goes from left to right only on every other line. On the

other lines it reverses everything and prints right to left.

By reversing both the dot patterns and the printing direction, the

LX-86 produces a line that is correct and looks no different from a

line printed from left to right. It does this to save time. Otherwise, the

time the print head takes to go from the right margin back to the left

would be wasted.

The intelligence of the printer takes care of all the calculations

necessary for this bidirectional printing, so you don’t have to be

concerned about it. You simply do your part of the work as if the

printer will be printing from left to right on each line and let the

LX-86 do all the necessary calculations so that you can enjoy the

increased speed.

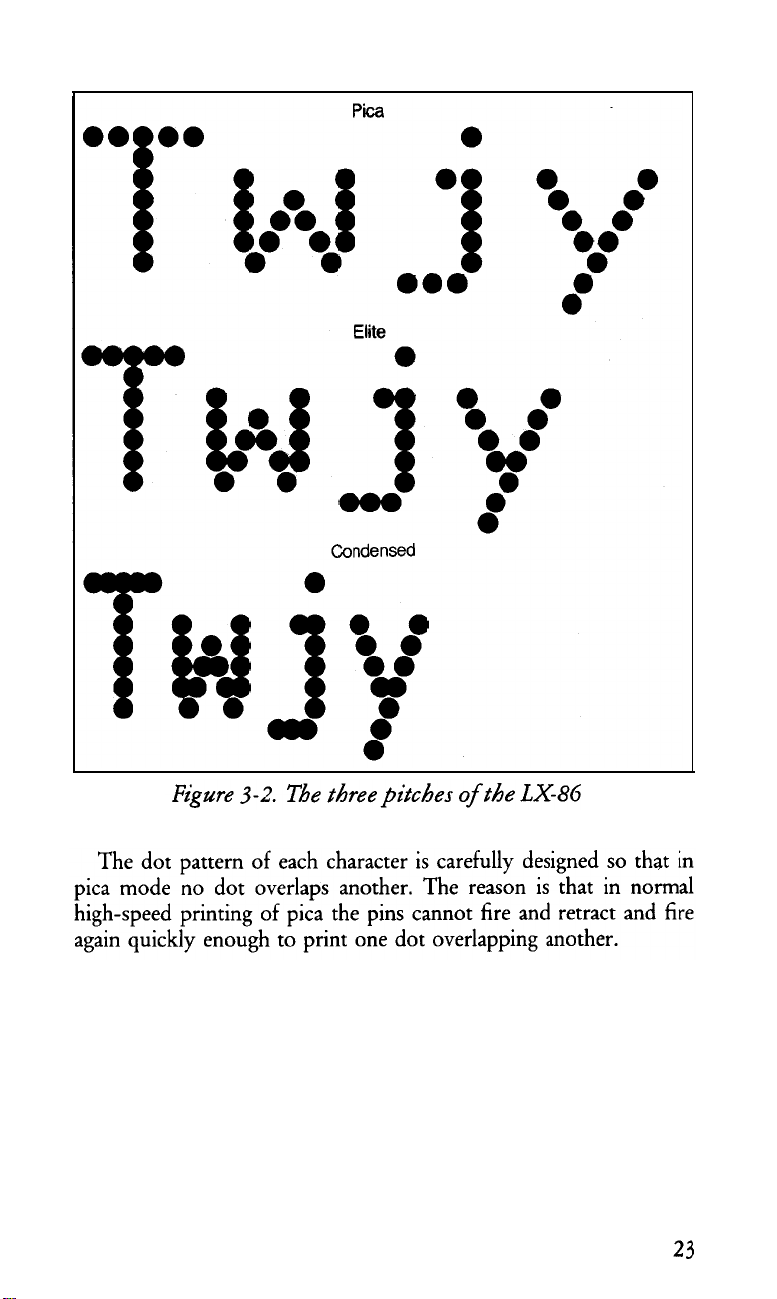

Changing Pitches

In addition to pica, in which there are 10 characters per inch,

the LX-86 can also print in other widths, or pitches. It does so by

reducing the distance between pin firings. In the elite mode it

prints 12 characters per inch and in the compressed mode it prints

17 characters per inch. The pattern of the dots is not changed, but

the horizontal space between them is reduced.

In Figure 3-2 are enlargements of four sample letters in each of the

three pitches. These letters are chosen to show how the LX86 prints

letters that are uppercase and lowercase, wide and narrow, and with

and without descenders (the bottom part of the y).

22

Page 30

Page 31

In Figure 3-3 there is a grid of lines behind the pica characters so

that you can more easily see how they are designed. As you look at

these characters you can see three rules that govern their design: the

column on the right side is always left blank so that there will be

spaces between the characters on a line; no character uses both the top

and the bottom row; and a dot can be placed on a vertical line only

when the columns next to that line are not used.

Figure 3-3. LX-86 dot matrix characters

NLQ Mode

The preceding examples are in the LX-86’s draft mode, but the

LX-86 also has the high-quality NLQ (Near Letter Quality) mode

that you have seen in previous chapters.

The NLQ letters are more fully formed than the draft letters because they are made up of many more dots. Two differences between

draft and NLQ printing enable the IX-86 to print such a large number of dots for each character. In the NLQ mode, the head moves

more slowly, so that dots can overlap horizontally, and each character

is printed with two passes of the print head.

To further ensure the quality of NLQ characters, both passes of the

print head are in the same direction so the alignment of the dots is

exact.

Because the NLQ mode uses two passes for each line and prints

only in one direction, your printing does take longer in this mode.

With the two modes, draft and NLQ, the IX-86 lets you choose

high speed or high quality each time you print. You can print your

ordinary work or preliminary drafts quickly in the draft mode and

use the NLQ mode for final copies or special purposes.

24

Page 32

The panel buttons make it especially easy to change from draft

to NLQ, but you can also select and cancel the NLQ mode with a

software command which you can find in Chapter 5.

25

Page 33

Chapter 4

Printer Control Codes

The LX-86 printer is easy to use, especially with commercial software that has print control features. This chapter explains some of the

basics of printer control and communications to help you understand

how a computer communicates with your printer. This information

should also help you understand the terms used in your software or

computer manual.

If you are an advanced user or a programmer, you may want to

turn to Appendix C, which has a full summary of all the Ix-86

commands.

ASCII Codes

When you write a document with a word processing program, you

press keys with letters on them. When you send the document to a

printer, it prints the letters on paper. The computer and the printer,

however, do not use or understand letters of the alphabet. They

function by manipulating numbers. Therefore, when you press the A

key, for example, the computer sends a number to its memory. When

the computer tells the printer to print that letter, it sends the number

to the printer, which must then convert the number to a pattern of

pins that will fire to print the dots that make up that letter.

The numbers that computers and printers use are in binary form,

which means that they use only the digits 0 and 1. In this manual,

however, we use decimal numbers in our explanations because most

users are more familiar with these numbers and because most programming languages and applications programs can use decimal numbers. The computer system or the program takes care of changing the

decimal numbers to binary form for you.

27

Page 34

Computer and printer interaction would be terribly confusing if

different kinds of computers and printers used different numbers for

the same letter of the alphabet. Therefore, most manufacturers of

computers, printers, and software use the American Standard Code

for Information Interchange, usually referred to as ASCII (pronounced ASK-Key). The ASCII standard covers the decimal numbers from 0 through 127 and includes codes for printable characters

(letters, punctuation, numerals, and mathematical symbols) and a few

control codes, such as the codes for sounding the beeper and performing a carriage return.

Although other codes are not standardized in the computer industry, the ASCII system means that at least the alphabet is standardized.

A programmer or engineer knows, for example, that 72 is the decimal

code for a capital H and 115 is the code for a lowercase s no matter

what system he or she is using.

ESCape Code

Although the original ASCII standard was designed to use the

decimal numbers 0 through 127, computer and printer manufacturers soon extended this range (to 0 through 255) in order to

make room for more features. On the IX-86, for example, the

codes from 160 through 254 are used for italic or character

graphics characters. Because even this extended range is not

enough for all the features used on modern printers, the range is

further extended with a special code called the Escape code. This

code is often printed with the first three letters capitalized

(ESCape) or abbreviated as ESC or <ESC> .

With the ESCape code, for which decimal 27 is used, printers and

computers are not restricted to only 256 instructions. The ESCape

code is a signal that the next code will be a printer control code

instead of text to print. For example, if the printer receives the number 69, it prints a capital E because 69 is the ASCII code for that letter.

If, however, the printer receives a 27 just before the 69, it turns on

emphasized mode, because ESCape “E” is the code for emphasized.

You can see how important the ESCape code is by looking at

Appendixes B and C. There you will see that nearly every code the

LX-86

uses is an ESCape code.

28

Page 35

Printer Codes

To take advantage of the many print features of the IX-86, you

can use a software program that sends the correct codes or you can

use another method to send codes. It’s not possible to be as precise

and specific as we would like in the rest of this chapter because the

IX-86 works with so many different applications programs and computer systems. If we gave precise instructions on how to use your

LX-86 with every one of them, this manual would fill at least four

volumes and would have to be updated every month.

We will, therefore, give you the general principles of how software

communicates with your printer, plus several ways the codes of the

LX-86 are used by applications programs such as word processing

and business programs. With this information and possibly some help

from your dealer or the manual for your applications program, you

can take advantage of all the features of the LX-86 that you want to

use. Incidentally, there is no standard terminology for software

codes; thus, the terms in your software manual may be different from

the ones we use here.

In general there are three ways you send printer codes with com-

mercial software:

l Using SelecType, the feature described in Chapter 2.

l Instructing the program during an installation or setup procedure

so that you can then use codes that are typed in along with your

text or numbers; we call these embedded codes.

l Inserting LX-86 printer codes in your text along with a special

code that tells the printer that the inserted codes are not text or

data.

There are three common formats for sending printer codes. Your

applications software or its manual should tell you which one to use.

l Decimal numbers-for example, 27 is the decimal number for the

ESCape code, and 13 is the decimal number for a carriage return.

l Hexadecimal numbers, in which the ESCape code is 1B and a

carriage return is OD. You don’t have to understand hexadecimal

numbers to use them. If your software calls for hex numbers, just

consult Appendix B or the Quick Reference Card for the

appropriate number.

29

Page 36

l The ESCape and control keys on your computer’s keyboard. With

this system you send the ESCape code by pressing the ESCape

key and a carriage return by pressing the control key and the M at

the same time. (See Appendix B or the Quick Reference Card for

the control key codes.)

Embedded codes

A program that uses embedded codes usually has its own set

of codes that you type into your document or file. When the program receives one of these codes, it sends the proper code to the

LX-86. For example, one popular word processing program has

you turn italic mode on and off by pressing the control key and P

and then pressing the Q. So if you want to italicize a word, you type

Control-PQ before it and after it. When the program reaches the first

Control-PQ, it sends the code to turn italic mode on, and when it

reaches the second, it sends the code to cancel italic. Please note that

these are not the same as the control key codes mentioned above.

Once you tell such a program that you are using an Epson printer,

it will know which codes to send. (Often you don’t even need to

specify which Epson printer you are using.) You usually tell the

program what printer you are using through an installation or set-up

procedure. The instructions should be in your software manual. In

addition, your software or computer dealer may be able to help you.

Many programs that use embedded codes also have a few commands that the user can define. If you are new to using printers, don’t

worry about these yet. Just use the standard features. Later, when

you are more familiar with your software and with your LX-86, you

may want to investigate the user-defined commands and customize

your program.

Inserted codes

To take advantage of some of the advanced features of the IX-86,

some programs require inserted codes. Those codes allow you to send

commands to the printer in the middle of text or data. In most of

these programs one code signals that the next numbers are printer

instructions, not text or data. In one such program, for example, you

type Control-V (pressing V while holding down the control key) to

signal the beginning of printer instructions. Then you enter your

print codes and type Control-V again to signal the end of the printer

instructions.

30

Page 37

If your word processing program allows inserted codes, it will

probably do standard printing without such codes. It is only for

special features that you will need to use inserted codes. For

example, if you want to have headings in wide bold printing

(called double-width emphasized), you would probably have to

use inserted codes. For the program we mentioned above you

would type Control-V, then the code for double-width empha-

sized, Control-V again, and then the text of the heading. The

codes for double-width emphasized are in Chapter 6 and

Appendix C.

Again, if this sounds terribly complicated, don’t worry. Use your

LX-86 with the standard features of your word processing program

until you become more familiar with both of them. Then you can

decide whether or not you need or want to learn to use inserted

codes.

See your software documentation for further information.

Programming Languages

If neither of the methods described above seems appropriate for

your application, you can write a program in BASIC or any other

programming language to send control codes to your printer. In the

chapter on page formatting you will find examples of such programs.

Just remember that with this method your printer control code stays

in effect for the whole document you print. This method is good for

setting margins, for example, but does not work for italicizing a word.

Now you have some background on how printers work and how

software can communicate with them. Turn to the next chapters to

learn about the specific features of your LX-86 printer.

31

Page 38

Chapter 5

IX-86 Features

Beginning with this chapter we describe many of the printing features of the LX-86. Although we include programs that demonstrate

these features, you don’t have to be a programmer to learn about the

features from these chapters. How much of the rest of this manual

you use depends upon your expertise, your interest, and the software

you plan to use.

(Demonstration Programs

Along with our discussion and examples of the LX-86 features, we

include demonstrations in the BASIC programming language so that

you can see these features in action. Although we know that you will

probably not do much of your printing using BASIC, we chose it for

our demonstrations because most computer systems include some

form of BASIC, so our examples are ones that almost every one of

you can try.

You don’t need to know anything about BASIC to type in and run

these programs. Just check your BASIC manual to see how to load

BASIC in your computer and how to run a program. As you run the

programs (or even as you read the explanations and look at the

printed examples), you learn how the LX-86 responds to the messages your computer sends it by printing letters, numbers, symbols,

and graphics in various print modes.

Even if you never use BASIC again, you will know the capabilities of your printer, capabilities that can often solve your printing

problems. For example, if you need a special symbol you will know

that you can turn to the chapter on user-defined characters and

create such a character.

33

Page 39

If you don’t want to do the exercises in

Many users are quite happy with their printers without ever learning

any more about them than how to turn them on and off and how to

load paper. Therefore, you shouldn’t be intimidated by the information in this manual. In most cases the software that you use for word

processing, business, or graphics does the calculating and communicating with the printer for you.

In fact, because of Epson’s long-standing popularity, many programs are designed to use Epson printers quite easily. Often all you

need to do is specify in an installation program that you are using an

Epson printer. Then the program sends the correct codes for the

various printing functions. The installation process, if there is one, is

explained in the manual for your software program.

BASIC,

you don’t have to.

We have designed these chapters so that you can concentrate on

using the features of the LX-86 instead of on programming, but

a few instructions are necessary. Because the examples in this

manual are in Microsoft BASIC (MBASIC), one of the most widely

used types of BASIC in personal computers, most users can enter

and run the programs exactly as they appear in these pages.

If your computer system uses any other kind of BASIC, you may

have to make a few changes. Probably the only item you will need to

change is the instruction LPRINT, which is the MBASIC command

to send something to the printer. Some forms of BASIC use PR#l at

the beginning of a program to route information to the printer and

PR#O at the end to restore the flow of information to the screen. If

you have such a system, just put PR#l at the beginning of your

program and then use PRINT instead of LPRINT in the programs. If

you have any other system, consult its manual to see if any modifications to our programs are necessary.

In Chapter 3 you saw the enlargements of the three LX-86 pitches.

Now you’ll learn how to produce them.

Pica Printing

The first exercise is a simple three-line program to print a sample

line of characters in pica, the standard pitch. Just type in this program

exactly as you see it:

40

FOR X=65 TO 105

50 LPRINT CHR$(X);

60 NEXT X: LPRINT

34

Page 40

Now run the program. You should get the results you see below,

10

pica characters per inch.

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQTRSTUVWXYZ[\]ˆ_`abcdefghi

Changing Pitches

Now you can try other pitches. As we explained in Chapter 3, the

IX-86 uses the same pattern of dots for pica, elite, and condensed

characters, but it changes the horizontal spaces between the dots to

produce the three different widths.

In elite mode there are 12 characters per inch, and in condensed

there are

“M” command and prints in condensed when it receives the

ASCII 15 command. Print a sample line of elite characters by

adding this line to your previous program:

20 LPRINT CHR$ (27) “M” ;

This line uses the command for elite, ESCape “M”, to turn on that

mode. Your printout should look like the one below.

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[\lˆ_`abcdefghi

17.

The LX-86 prints in elite when it receives the ESCape

The next addition to the program cancels elite with ESCape “P” and

turns on condensed with ASCII

15:

30 LPRINT CHR$ (27) “P” CHR$ (15) ;

Now run the program to see the line printed in condensed mode.

ABCDEFHIGKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[\]ˆ_`abcdefghi

Cancelling Codes

As you saw in the third version of the print pitch program, you

must cancel a code when you do not want it any more. With very

few exceptions, the LX-86 modes stay on until they are cancelled.

It is important to remember this because an

on even if you change from BASIC to another type of software. For

example, if you print a memo with a word processing program

after you run the program above, the printer will still be in

condensed mode; therefore, the memo will be in condensed

print. To cancel, use ASCII

18.

LX-86

mode can stay

35

Page 41

To avoid having one program interfere with the printing modes of

another, you can cancel a mode one of two ways:

l With a specific cancelling code, such as the ESCape “P” that we

used above to cancel elite. Each mode has a cancelling code, which

you can find in the discussion of the code and in Appendix B. Pica

is an exception to this rule. To cancel pica, turn on elite.

l By resetting the printer, a method explained in the next section.

Resetting the Printer

Resetting your LX-86 cancels all modes that are turned on. You

can reset the printer with one of two methods:

l Sending the reset code (ESCape “@”)

l Turning the printer off and back on.

Either one of these methods returns the printer to what are

called its defaults, which are the standard settings that are in effect

every time you turn the printer on. The two effects of resetting the

printer that you should be concerned with are: it returns the

printing to single-strike pica, thus cancelling any other pitches or

enhancements you may have turned on with control codes or

SelecType, and the current position of the print head becomes the

top of page setting.

Some of our demonstration programs end with a reset code so that

the commands from one program will not interfere with the commands in the next one. After you run a program with a reset code in

it, remember to change the top of page setting before you begin

printing full pages.

Pitch Comparison

Now that you have used three short programs to produce samples

of the main pitches, you can choose the pitch that you prefer or the

one that best fits a particular printing job. Most people use either

pica or elite for printing text and condensed for spreadsheets or

other applications in which it is important to get the maximum

number of characters on a line.

36

Page 42

In fact, if you need even more than the

that condensed gives you, you can combine elite and condensed

for a mode we call condensed elite. It is not really another pitch,

because the size of the characters is the same as in the condensed

mode; only the space between the characters is reduced. You can

see this mode, which allows 160 characters to fit on a line, if you

replace line 30 in your last program with this line:

132

characters per line

30 LPRINT CHR$(l5);

With this addition, the program turns on condensed but doesn’t

turn off elite, giving you the printout below:

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[\]ˆ_`abcdefghi

If your printout is different, you may need a

such as the one below:

WIDTH

statement

5 WIDTH LPRINT 255

The format for your system will probably be different. Consult

your

BASIC

manual.

Near Letter Quality Mode

The examples so far in this chapter are in the draft mode, and

you have already learned how to turn on the NLQ mode with a

panel button, but you can also see the NLQ mode with the

following program:

10 LPRINT CHR$ (27) “x” CHR$ (1) ;

20 FOR X=65 TO 105

30 LPRINT CHR$ (X);

40 NEXT X: LPRINT

Note that you use a lowercase x, not a capital X, in line 10.

Because of the high resolution of the NLQ mode, it prints only in

pica, not in elite or condensed.

37

Page 43

All the modes demonstrated in this chapter are compared in Table

5-l.

Table 5-1, Summary of LX-86 pitches

Print sample

1 inch

Near Letter Quality

Pica print

Elite print

Condensed print

Condensed elite print

CPI

10.00

10.00

12.00

17.16

20.00

Codes

on

ESC "x" 1

ESC "P" ESC "M"

ESC "M" ESC "P"

ESC "P" 15

ESC "M" 15 ESC "P" 18

oft

ESC "x" 0

18

Remember that you don’t have to use BASIC to change modes;

you can use any method that sends the printer the proper codes.

38

Page 44

Chapter 6

Print Enhancements and Special Characters

Now that you have seen how you can change the pitch of your

IX-86 printing, we can show you many more ways to vary and

enhance your printing. So that you won’t have to type in dozens of

programs to try all the features, we give you just one master program

that can demonstrate any feature.

Bold Modes

Besides the pitches (pica, elite, and condensed) that we covered

in Chapter 5, the LX-86 offers many other typestyles, including

two for bold printing-emphasized and double-strike.

Emphasized mode

In the emphasized mode the IX-86 prints each dot twice, with the

second dot slightly to the right of the first. In order to do this, the

print head must slow down so that it has time to fire, retract, and fire

the pins quickly enough to produce the overlapping dots. As you can

see in Figure

formed characters that are darker than single-strike ones.

6-1,

this method produces better-looking, more fully-

Standard Print

Figure 6-l. Emphasized and standard print

Emphasized Print

39

Page 45

Emphasized works only in draft pica and NLQ modes. In elite

and condensed the dots are already so close together that even

with the reduced print speed, the LX-86 cannot fire, retract, and

again fire the pins quickly enough to print overlapping dots.

You do sacrifice some print speed and ribbon

because the print head slows down and prints twice as many dots, but

the increase in print quality is well worth it. Indeed, you may want to

use emphasized instead of the NLQ mode for some purposes because

emphasized printing is faster. than NLQ printing.

Now that you have seen our example of emphasized printing, we

will give you

the ESCape codes, including the ESCape code to turn on emphasized: ESCape “E”.

Master program

First, type in the program below. If you have some programming

experience, you can see that the program asks you what codes

you want to test and then prints a sample of what the codes do. Be

sure to ty

Applesoft

20 PRINT “Which ESCape code do you ”

30 INPUT “want to test” ; A$

40 PRINT .“What kind of printing ”

50 INPUT “does it produce” ; B$

60 LPRINT CHR$(27)A$

70 LPRINT “This sample uses ESCape “;A$

80 LPRINT “to produce “;B$; ” printing. ”

90 LPRINT CHR$(27)“@”

a master program that allows you to test almost any of

e in the blank spaces in lines 70 and 80. If you are using

™,

BASIC, see Appendix F.

life with emphasized,

Now run the program. When the first question appears on the

screen, type a capital E and then press the RETURN key. Type

“emphasized” and press the RETURN key in answer to the second

question. The program is easy to use. Just remember to press the

RETURN key after the answer to each question and to use a capital

letter in the answer to the first question unless we tell you to use a

lowercase letter for a specific code.

40

Page 46

You should get the following printout when you run this program

and type “E” and “emphasized” in answer to the questions.

This sample Uses ESCape E

to produce emphasized printing.

The code to turn off emphasized is ESCape “F”.

Double-strike

The other bold mode on the LX-86 is double-strike. For this mode

the printer prints each line, then moves the paper up slightly and

prints the line again. Each dot is printed twice, with the second one

slightly below the first as you can see in Figure 6-2.

Standard Print

Double-strike print

Figure 6-2. Double-strike and standard print

Unlike emphasized, double-strike combines with any draft pitch

(but not with NLQ) because it does not overlap dots horizontally.

Since each line in this mode is printed twice, the speed of your

printing is slowed. The code for double-strike is ESCape “G”. Try it

in the the master program if you wish. The code to turn off doublestrike is ESCape “H”.

41

Page 47

Double-width Mode

Perhaps the most dramatic mode on the LX-86 is double-width.

It produces extra-wide characters that are good for titles and

headings. For this mode, the dot pattern of each character is

expanded and a duplicate set of dots is printed one dot to the

right. You can see the difference between pica and double-width

pica in Figure 6-3.

Standard Print

Figure G-3. Double width and standard characters

You can try double-width yourself by using the code

the master program. Notice that double-width uses an ESCape

code format that is slightly different from the previous ones. You

must use the numeral one as well as a capital W to turn on doublewidth. For this mode the letter and the numeral one together turn

on the mode and the letter and the numeral zero together turn it

off. Thus ESCape “Wl” turns on double-width and ESCape

"Wo”

another form of double-width. In this alternate form, called one-

line double-width, the printing is the same as that in Figure 6-3,

but it is turned on by ASCII 14 and is turned off by a line feed,

ASCII

turns it off.

Those of you who are programmers may be interested in

20,

or ESCape

Double-width

“WO”.

“W1”

in

42

Page 48

Mode Combinations

You can combine nearly all of the print modes on the LX-86.

Indeed, your Ix-86 printer can print such complicated combinations as double-strike emphasized double-width underlined italic

subscript, although we’re not sure that you would ever want to use

such a combination. The point is, however, that the LX-86 has the

ability to produce almost any combination you can think of; it’s

up to you to decide which ones you want to use.

To see a few combinations, remove line

ram. (In MBASIC simply type

90

and press RETURN to delete the

90 from

the master prog-

line.) Now run the program once and enter “E” and “emphasized” in

response to the questions on the screen. This will give you the same

results as the first time you ran the program, but it will leave the

printer in emphasized mode so that you can add another mode. Then

run the program again (without turning off the printer). The second

time enter “W1” and “emphasized double-width.”

Your printout should be in the typestyle below, showing that the

two modes combine with no trouble. You can experiment with other

combinations if you wish or you can wait for the section later in this

chapter that explains a special ESCape code, Master Select, which

allows you to combine as many as seven features with one ESCape

code.

emphasized

When you are through trying combinations, be sure to replace line

90 in the master program so that you can again try one feature at a

time.

double-wid

Italic Mode

You may occasionally want to print italic words for emphasis,

titles, or other uses. The LX-86 has italic mode to enable you to use

italic characters for any purpose. Although characters produced by

the previous modes in this manual are modifications of the standard

pica characters, the LX-86 uses completely different characters for the

italic mode. In the printer’s Read Only Memory (ROM) is a complete

set of draft italic characters. You can see the difference between standard and italic draft characters in Figure 6-4.

43

Page 49

Standard Pica Print

Italic Pica Print

Figure 6-4. Italic and pica

The code to turn italic mode on is ESCape “4”. Try it in the master

program if you wish. When you use this code in the master program,

enter “4” in answer to the first question just as if it were a letter of the

alphabet instead of a number. ESCape “5” turns off italic mode.

Those of you who use this code in an applications program should

remember that any character in quotation marks in our discussions of

ESCape codes is an alphanumeric character, not a numerical value.

Underline Mode

The LX-86 also has a mode that will underline characters and

spaces. You turn it on with ESCape “-1” and off with ESCape “-0".

Note that the underline code is like the expanded code in that it uses a

character, in this case the hyphen or minus sign, combined with

numeral one to turn it on and a character combined with the numeral

zero to turn it off. As you can see in Figure 6-5, this mode prints a dot

in the bottom row of each column, thus producing a continuous

underline.

44

Page 50

This uses the underline mode.

Figure 6-5. The underline mode

As shown in Figure 6-5, the underline mode is continuous, but

some word processing and other applications programs produce an

underline that leaves spaces between characters as demonstrated in the

printout below.

This uses the under-line character

If your software prints this type of underline, it is using the

LX-86’s underline character (ASCII %), not the underline mode.

Because the underline character is only five dots wide, it does not fill

the spaces between characters. If you prefer a continuous underline,

you may be able to use the underline mode through one of the

methods we discussed in Chapter 4.

Master Select

The LX-86 has a special ESCape code called Master Select that

allows you to choose any possible combination of eight different

modes: pica, elite, condensed, emphasized, double-strike,

double-width, italic, and underline. The format of the Master

Select code is ESCape ‘!” followed by a number that is calculated

by adding together the values of the modes listed below:

underline

italic

double-width 32

double-strike

emphasized

condensed

elite

pica

128

64

16

8

4

1

0

45

Page 51

For any combination,. just add up the values of each of the modes

you want and use the total as the number after ESCape “!“. For

example,

add the following numbers together:

to calculate the code for double-width italic underlined pica,

underline

italic

double-width 32

pica

To print this combination, therefore, you use ESCape "!” followed

by the number 224. In BASIC the command is CHR$(27)“!”

CHR$(224).

To try this number or any other, enter and run this short program,

which will ask you for a Master Select number and then give you a

sample of printing using that code. Again, if you are using Applesoft

BASIC, see Appendix F.

10 INPUT “Master Select number” ;M

20 LPRINT CHR$ (27) ”!“ CHR$(M)

30 LPRINT “This sample of printing uses ”

40 LPRINT

50 LPRINT CHR$(27) “@”

In this program, you can use any number you calculate with the

formula above, but remember that emphasized can’t combine

with condensed or elite. If you try to combine emphasized with

either of the two narrow pitches, you won’t harm your printer; it

will simply use a priority list in its memory to determine which

mode to use. This priority list causes a corn bination of emphasized

and elite to produce elite only, a combination of emphasized and

condensed to produce emphasized only, and a combination of all

three to produce condensed elite.

"Master Select number";M

128

64

0

224

Master Select is a powerful code that gives you an easy way to

produce multiple combination's with a single command. To see

double-strike emphasized italic printing, for example, you need only

one ESCape code instead of three.

46

Page 52

Indeed, Master Select is such a powerful feature that it may occasionally be more powerful than you want it to be. Because it controls

eight different modes, a Master Select code will cancel any of those

eight that are not selected. For example, suppose that you have a page

in elite and want part of it printing in italic. If you use ESCape “!” 64

to turn on italic, your LX-86 will begin printing in italic pica instead

of italic elite because the 64 code does not include elite. Use 65 for

italic elite.

Superscript and Subscript

Your LX-86 can also print superscripts and subscripts, which you

can use for mathematical formulas, footnotes, and other items that

require numbers or letters above or below the usual print line.