Dolby 53 evolutionofsound schematic

G

oing to the movies

today is more

exciting and

involving than ever before,

thanks in large part to a

continuing effort to improve

film sound undertaken by

Dolby Laboratories in the

early 1970s. Indeed, the

history of cinema sound over

the past two decades closely

mirrors the history of Dolby

film sound technologies.

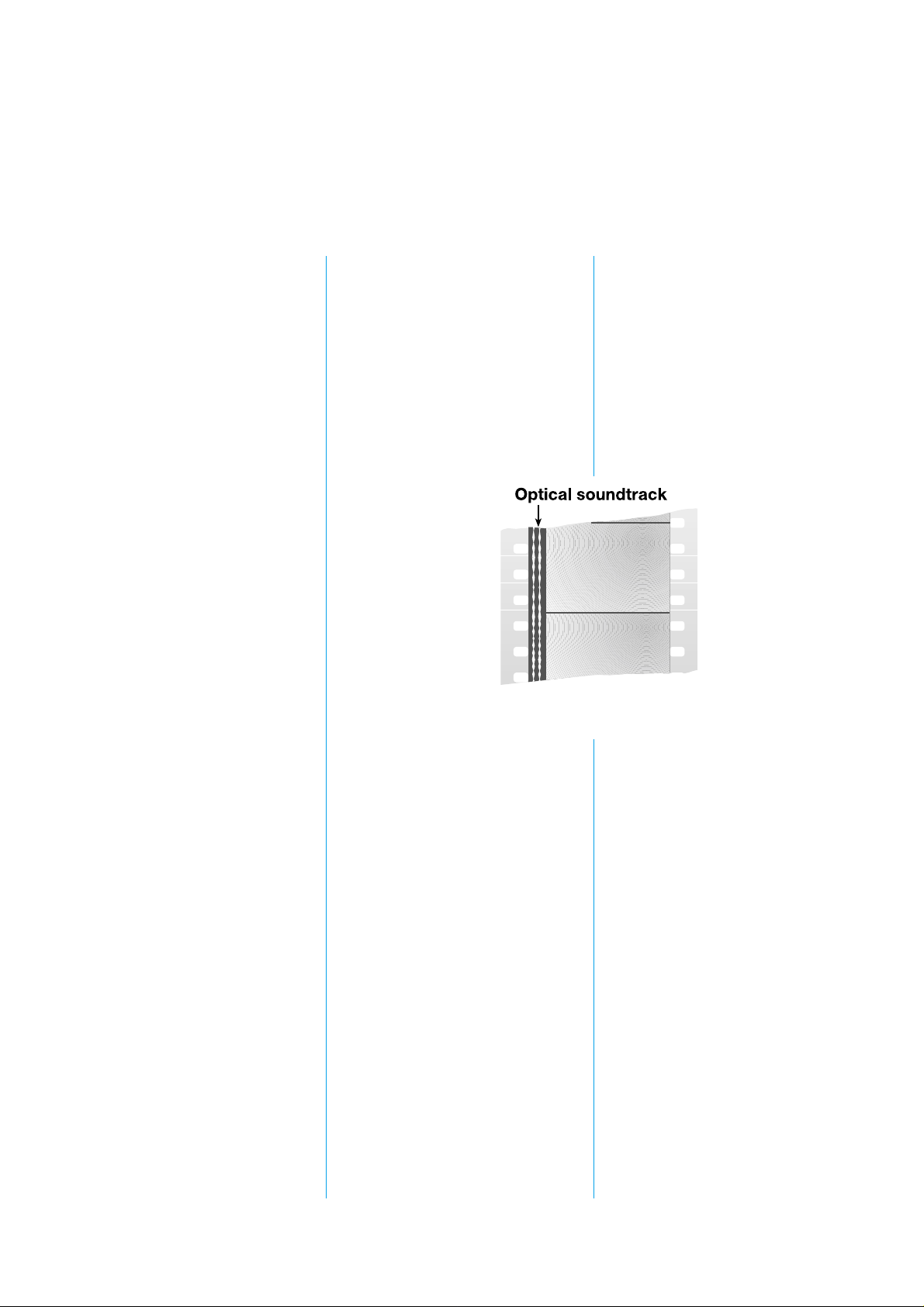

Optical

soundtracks

The photographic, or

“optical,” soundtrack was the

first method of putting sound

on film. Today it remains the

standard, in both analog and

digital forms.

The classic analog optical

soundtrack consists of an

opaque area adjacent to the

picture containing narrow,

clear tracks that vary in

width according to variations

in the sound (Figure 1). As

the film is played, a beam of

light from an exciter lamp or

LED in the projector’s

soundhead shines through

the moving tracks.

Variations in the width of the

clear tracks cause a varying

amount of light to fall on a

solar cell, which converts

the light to a similarly

varying electrical signal.

That signal is amplified and

ultimately converted to

sound by loudspeakers in

the auditorium.

Economy, simplicity, and

durability are among the

advantages that have

contributed to optical sound’s

universal acceptance. The

soundtrack is printed

photographically

on the film at the

same time as

the picture and

can last just as

long, which—

with care—can

be a long time

indeed. And the

optical soundhead within the

projector is itself

economical and

easily maintained.

Success gets

in the way

of progress

Motion pictures with sound

were first shown to significant

numbers of moviegoers in

the late 1920s. Within a few

years, many thousands of

theatres were equipped to

show “talking pictures” with

optical soundtracks.

This phenomenally rapid

acceptance of a new,

sophisticated technology was

not without drawbacks,

however. Equipment was

installed in cinemas so

rapidly that there was no time

to take advantage of the

improvements that occurred

almost daily.

A good example is

loudspeaker design. The first

cinema loudspeakers had

very poor high-frequency

response. Speakers with

superior

response

became

available within

just a few years,

but there was no

time to retrofit

the original

systems with

new units.

Engineers were

too busy

equipping other

cinemas with their first sound

installations.

This caused a dilemma for

soundtrack recordists. Should

the tracks be recorded to

take advantage of the

improved speakers, or should

they be prepared to sound

best on the many older

installations already in place?

Given that it was impractical

to release two versions of a

given title, the only

alternative was to tailor

soundtracks to the older

speakers. The result was to

ignore the improved highfrequency response of the

newer, better units.

The Evolution of

Dolby Film Sound

Figure 1: 35 mm

optical print

2

To forestall compatibility

problems, in the late 1930s a

de facto standardization set

in, the cinema playback

response that today is called

the “Academy” characteristic.

Cinema owners knew what

to expect from

the films, and

therefore what

equipment to

install. Directors

and sound

recordists knew

what to expect

from cinema

sound systems,

and thus what

kind of

soundtracks to

prepare. The

result was a

system of sound recording

and playback that made it

possible for just about any

film to sound acceptable in

any cinema in the world. The

problem was that the system

lacked the flexibility to

incorporate improvements

beyond the limitations that

existed in the 1930s.

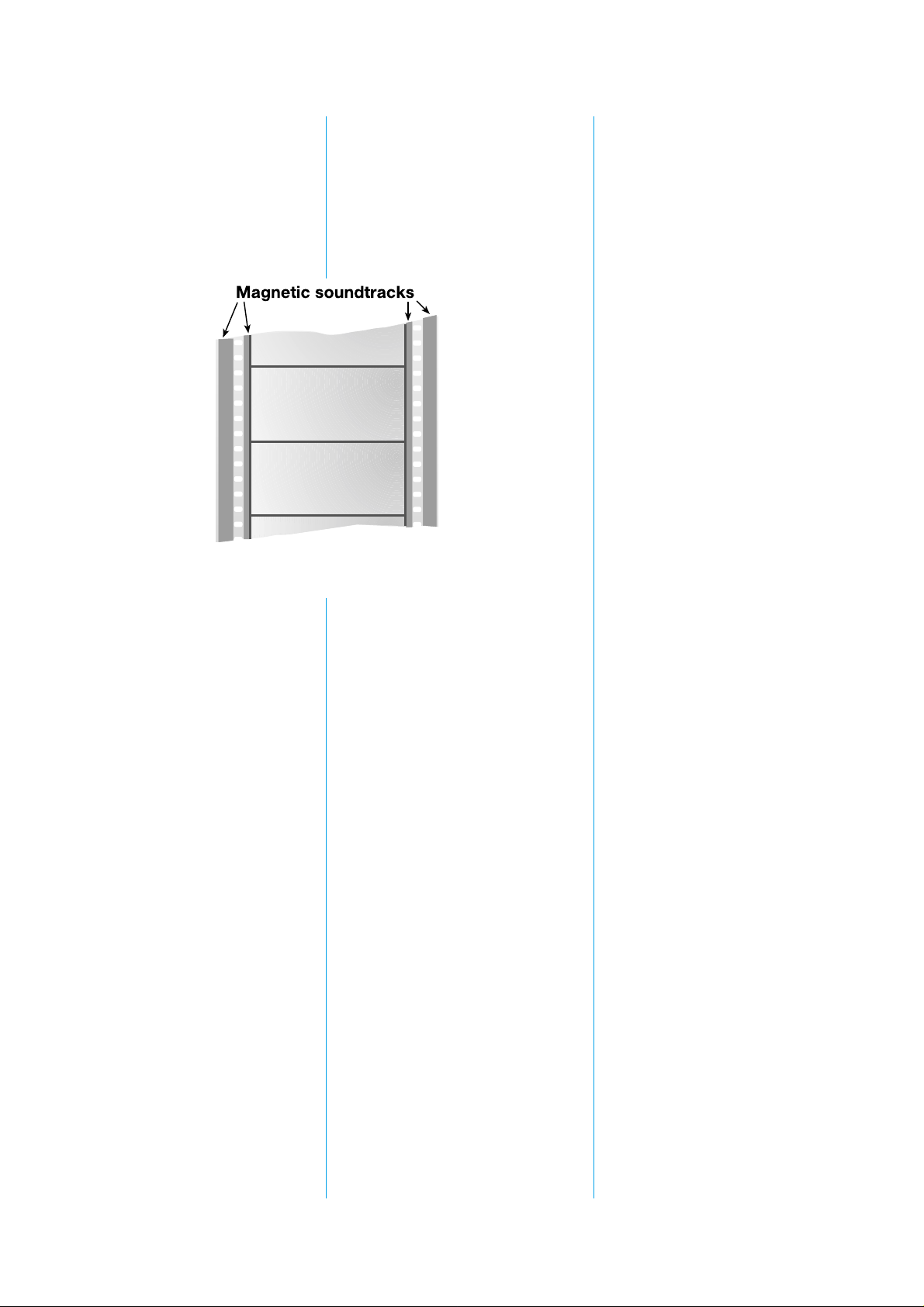

Magnetic striping

and multichannel

sound

In the early 1950s, as the

film industry sought to woo

viewers away from their

fascinating new television

sets, a new method of putting

sound on film was

introduced. After the picture

was printed, narrow stripes of

iron oxide material (similar to

the coating on magnetic

recording tape) were applied

to the release print

(Figure 2). The sound was

then recorded on the

magnetic stripes in real time.

In the cinema, magnetic

prints would be played back

on projectors equipped with

magnetic heads

similar to those

on a tape

recorder,

mounted in a

special

soundhead

assembly called

a “penthouse.”

Magnetic

sound was a

significant step

forward, and at

its best provided

much-improved

fidelity over the conventional

optical soundtrack. It also

enabled the first multichannel

sound reproduction, dubbed

“stereophonic sound,” ever

heard by the public. The

voice of an actor appearing

to the left, center, or right of

the picture could be heard

coming from speakers

located at the left, center, or

right of the new wide screens

also being introduced at this

time. Music took on a new

dimension of realism, and

special sound effects could

emanate from the rear or

sides of the cinema. The two

main magnetic systems

adopted were the four-track

35 mm CinemaScope

system, introduced with

The Robe, and the six-track

70 mm Todd-AO, first used

for Oklahoma!

Magnetic falls

into disuse

Magnetic sound was widely

adopted in the 1950s. By the

1970s, however, when the

film industry experienced an

overall decline, the expense

of magnetic release prints,

their comparatively short life

compared to optical prints,

and the high cost of

maintaining the playback

equipment led to a massive

reduction in the number of

magnetic releases and

cinemas capable of playing

them. Magnetic sound came

to be reserved for only a

handful of first-run

engagements of “big”

releases each year.

By the mid-1970s, then,

movie-goers were again

hearing low-fidelity, mono

optical releases most of the

time, with only an occasional

multitrack stereo magnetic

release. Ironically, just as the

industry was reverting to

mono optical, more and more

moviegoers were enjoying

better sound at home over

superior hi-fi stereo systems.

Dolby gets

involved

By the late 1980s, the

situation that prevailed in the

mid-1970s had completely

changed. Thanks to new

technology and a turnaround

in the financial decline of the

industry, almost all major

titles by that time were being

released with wide-range

multichannel stereo

Figure 2: 70 mm

magnetic print

very little maintenance was

required. The result was

multichannel capability

equaling that of four-track

magnetic 35 mm (which

soon became obsolete), with

consistently higher fidelity,

greater reliability, and far

lower cost.

The next step:

Dolby SR

In 1986, Dolby Laboratories

introduced a new

professional recording

process called Dolby SR

(spectral recording). Like

Dolby noise reduction, it was

a mirror-image, encodedecode system used both

when a soundtrack is

recorded and when it is

played back. It provided

more than twice the noise

reduction of Dolby A-type,

and, moreover, permitted

loud sounds with wider

frequency response and

lower distortion.

The 35 mm optical

soundtracks treated with

3

soundtracks, as is the

case today.

The breakthrough was the

development by Dolby

Laboratories of a highly

practical 35 mm stereo

optical release print format

originally identified as Dolby

Stereo. In the space allotted

to the conventional mono

optical soundtrack are two

soundtracks that not only

carry left and right

information as in home

stereo sound, but are also

encoded with a third centerscreen channel and—most

notably—a fourth surround

channel for ambient sound

and special effects

(Figure 3).

This format not only

enabled stereo sound from

optical soundtracks, but

higher-quality sound as well.

Various techniques were

applied to the soundtrack

during both recording and

playback to improve fidelity.

Foremost among these was

Dolby A-type noise reduction

to lower the hissing and

popping associated with

optical soundtracks, and

loudspeaker equalization to

adjust the cinema sound

system to a standard

response curve.

As a result, stereo optical

prints could be reproduced

in cinemas installing Dolby

cinema processors with far

wider frequency response

and much lower distortion

than conventional

soundtracks. In fact, the

Dolby optical format led to a

new worldwide playback

standard (ISO 2969) for

wide-range stereo prints.

An important advantage of

the Dolby optical format was

that the soundtracks were

printed simultaneously with

the picture, just like mono

prints. Thus four-channel

stereo optical release prints

cost no more to make than

mono prints, and far less

than magnetic prints. In

addition, conversion to

stereo optical proved

relatively simple, and once

the equipment was installed,

Figure 3: Dolby analog 35 mm playback

Loading...

Loading...