Walthers Cornerstone 933-2926 Reference Book

VALLEY CITRUS PACKERS

HO Structure Kit

933-2926

Thanks for purchasing this Cornerstone

Series®kit. Please take a few minutes to read

these instructions and study the drawings

before starting. All parts are styrene plastic,

so use compatible glue and paint to finish

your model.

Whether it’s a glass of orange juice and a

grapefruit half for breakfast or ice-cold

lemonade on a hot summer afternoon, citrus

fruits are among our favorite foods. Once

considered a rare treat, the growth of the citrus industry was fueled by the development

of railroads.

Citrus fruits are believed to be native to

Asia’s subtropical and tropical regions, especially the Malay Archipelago. Ancient sailors

prized them for their ability to prevent

scurvy (a disease caused by lack of vitamin

C) on long voyages along the spice routes.

As a result, citrus fruits gradually spread into

China and across Europe. On his second trip

to the Americas in 1493, Christopher

Columbus brought citrus seeds to the first

settlements. Early Spanish explorers introduced citrus to Florida around 1565.

California’s citrus came by way of the

Spanish padres who brought orange and

lemon seeds from Mexico as they moved

north establishing their mission system. The

first California orange grove was planted at

Mission San Gabriel about 1804. After

Spain’s cession of Florida to the United

States in 1821, a commercial citrus industry

began to grow there as well. The first commercial grapefruit grove was planted near

Tampa in 1823. These small early groves

were situated along rivers, the only means of

shipping at the time.

California’s citrus industry took off during

the Gold Rush of 1849. Hunter and trapper

William Wolfskill planted California’s first

commercial grove in 1841 in what is now

downtown Los Angeles. During the lucrative

Gold Rush years he sold his oranges to miners for $1.00 apiece.

In 1873 the U.S. Department of Agriculture

sent a pair of navel orange trees to a farmer

in Riverside as an experiment; ideal soil and

weather conditions produced excellent fruit.

As word of the success spread, California’s

second Gold Rush began with the development of large-scale citrus ranches. In 1877,

when railroads reached the area, Wolfskill’s

son Joseph tried shipping a carload of

oranges to St. Louis via the Southern Pacific

and Union Pacific. The trip took a month

and required numerous stops for ice, but

more than half the fruit survived.

Within a few years, the successful development of refrigerated cars and a network of

icing stations made

it possible to ship perishables long distances by train. However, since

citrus was only available in season, first-crop

fruits would fetch high prices in eastern markets. Time was literally money and to speed

the cargo on its way, solid trains of reefers

were rushed eastward, often with priority

over flagship passenger trains! This also

required an efficient way to get fruit from

groves to the railroads for loading, and the

packinghouse was born.

When a crop was ready for harvest, growing

regions became beehives of activity. The

work began in the groves where the fruit was

picked by hand and loaded in tough wooden

“orchard boxes.” Filled boxes were stacked

between the rows of trees where they could

easily be loaded aboard wagons (and later on

flatbed trucks) for the trip to town and the

local packinghouse.

On arrival, workers exchanged filled boxes

for empties, which were trucked back to the

groves to prevent delays. Loaded boxes were

dumped at the start of the production line

where the fruit was then washed, sorted by

size and graded. Fruit that didn’t meet certain standards was shipped off to make juice

or simply dumped. As the final step, the fruit

was packed in shipping crates featuring

brilliantly colored paper labels (crates and labels

were used until World War II when they

were replaced by preprinted cardboard

boxes; today, original citrus labels are prized

collectibles) identifying the grower and the

grade of the fruit. A single packinghouse

would usually ship several grades of fruit,

each under a different brand name. Workers

loaded the shipping crates in reefers spotted

alongside the packinghouse.

Loaded cars were picked up quickly by local

trains and moved to the nearest yard. If

needed, the ice would be topped off, and the

cars moved out on the next available train.

While cars moved in solid trains of reefers,

many were handled as blocks of cars on fast

freights, where they were coupled right

behind the engine to make them easy to

switch out upon arrival at the next division

point or icing station.

The years following World War II brought

significant changes in the citrus industry.

Post-war housing developments began to

encroach on orchards forcing growers and

packinghouses out of business. At the same

time, the development of frozen concentrated citrus juices led to more demand.

Growers responded by planting new groves

in rural areas and marketing the new frozen

and hot pack juices, which required different

processing operations.

T

oday, a handful of early packinghouses are

still standing, but some are still processing

citrus fruit.

ON YOUR LAYOUT

This “wooden” structure is patterned after a

prototype built in Santa Anna, California,

around 1900, which was probably destroyed

in the 1960s. Like the prototype, the model

features a mission-style facade common to

structures built in citrus growing states —

since the work was nearly identical, your finished model can handle other fruits or vegetables in almost any growing area.

As built, these small facilities often had two

or more parallel spur tracks. Cars on the far

track were loaded using a metal bridge plate

placed in the open doorways between the

first and second string. During the picking

season, colorful wood and later steel reefers

would be spotted here for loading. First-crop

fruits might also be loaded aboard express

reefers such as Walthers R50b (#932-5880

series), GACX 50’ wood cars (#932-5470 or

5478 series), or REA 50’ Riveted Steel cars

(#932-6240 series) for priority shipment on

fast passenger trains. And since certain fruits

mature in summer and others in winter, your

citrus packinghouse could keep crews busy

year ’round.

A typical town would have several packinghouses, each serving a different co-op or

processing company. Other trackside businesses

might include an Icehouse and

Platform (#933-3049) to re-ice loaded or

empty cars. A local oil dealer like Interstate

Fuel & Oil #933-3006) would be busy handling tank car loads of gasoline to keep the

trucks rolling, along with smudge oil, burned

by growers in smudge pots to keep citrus

trees from freezing during frosts. Many

towns also had a box factory that received

carloads of lumber by rail, and made both

orchard boxes and shipping crates.

To complete your scene, add Stake Flatbed

Trucks (433-1618), stacks of wooden

orchard boxes, groves of Orange Trees

(#433-1909) and dockworkers. For additional figures, vehicles and other accessories, see

your dealer, check out the latest Walthers

HO Scale Model Railroad Reference Book

or visit waltherscornerstone.com for

more ideas.

© 2012 Wm. K. Walthers, Inc., Milwaukee, WI 53218 waltherscornerstone.com I-933-2926

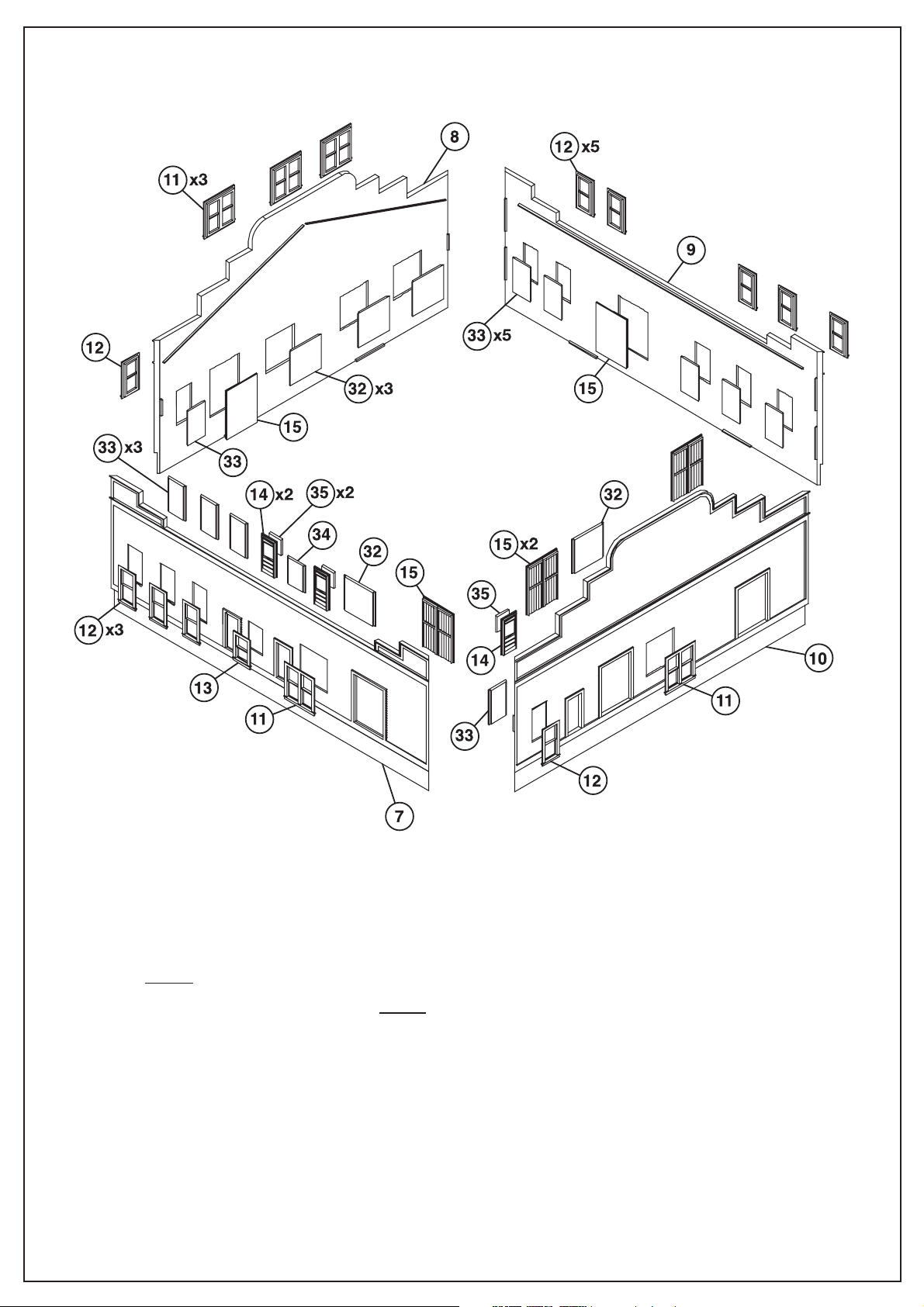

1. Glue the windows (11, 12, 13) into the appropriate openings in

the frontof the walls (7, 8, 9, 10). Next glue the doors (14,15) into

the wall openings in the back

of the walls. Then glue the “glass”

(32, 33, 34, 35) on the backs of the windows and doors as shown.

Loading...

Loading...