Page 1

No. 61

Restoration Log

&

Instruction Manual

Andrew LaBounty, 2002

1

Page 2

Waterbury

Regulator

No.61

Andrew LaBounty, Apprentice Clockmaker;

Sophomore, Olathe North High School, 2002

2

Page 3

Table of Contents

A History of the Waterbury Clock Company

The Process

To Begin – The Take Down.....................................................................................3

At the Shop – Cleaning it up....................................................................................4

On Paper – Making a Map.......................................................................................5

Taking It Apart – And Determining Beats per Hour...............................................6

Polishing Pivots – The Dreary Part..........................................................................7

Major Project – The Escape Wheel “Nut”...............................................................8

Bushing – For Real Now..........................................................................................9

Polishing the Pivot Holes – Everything’s so Shiny!..............................................10

The Escapement – Theory, Practice, and Math .....................................................10

Beat and Rate Adjustments – Nuts and Knobs......................................................11

Refitting the Second Hand – Found in the Case....................................................12

Conclusion – And Thanks......................................................................................13

Care and Maintenance..................................................................................................14-17

Winding..................................................................................................................14

Setting to Time.......................................................................................................14

Rating.....................................................................................................................15

Cleaning.................................................................................................................15

Moving the Clock ..................................................................................................16

Setup After Moving ...............................................................................................16

Setting the Beat......................................................................................................17

Bibliography ......................................................................................................................18

Attachments ................................................................................................................. 19-22

A: Repair Itemization.............................................................................................19

B: Tooth Count ......................................................................................................20

C: Original Sketch..................................................................................................21

D: Other Sketches..................................................................................................22

....................................................................................................................3-13

..................................................................1-2

3

Page 4

A History of the Waterbury Clock Company

(1857 – 1942)

The Waterbury Clock Company, founded in March 5, 1857, began as a venture

into the lucrative clock market by the ambitious Benedict & Burnham Corporation,

heretofore the “B&B Corp.” Being a company specializing in the production of brass,

and with clock movements being made of brass, the B&B Corp. made its first attempt at

utilizing its goods for the measurement of time by investing heavily in the business of a

clockmaker named Chauncey Jerome with the understanding that Jerome would buy

brass from no other brass company. Thus began a short cooperation that ended with

Jerome striking out upon his own business with $75,000 of B&B’s brass, which they sold

to Jerome at a profit. Having only begun to satisfy the needs of impatient people waiting

for, and trying to catch trains, B&B began their own clock company: The Waterbury

Clock Company!

It started in an old mill, very near to the main factory of the B&B Corp. Strapped for

good clockmakers, the corporation decided to honor Jerome’s brother, Noble Jerome,

with the title “chief foreman of movement production.” So began the famous clock

making business in Waterbury, CT on March 5, 1857 as a company of the Benedict &

Burnham Corporation. The Waterbury Clock Company was described in its time by

Chauncey Jerome in his autobiography as being a company of famous “first citizens of

that place” including a senator and one of the richest men in the country. He also spoke

of his brother, the chief movement mechanic, as being “as good a brass clock maker as

can be found.” A great grief struck the Company in 1861, however, when Noble Jerome

was killed by a falling balustrade while strolling in the merry month of May. Silus B.

Terry replaced Noble as master clockmaker. Silus B. Terry, apprenticed by his father Eli

Terry, later founded the Terry Clock Company with his sons. Incidentally, Eli Terry also

apprenticed the famous clock maker Seth Thomas who created his own company when

Silus B. was but two years old.

After the Civil War, in which most of Waterbury’s employees participated on the Union

side, the Company erected two large case-building shops. They were hardly used,

though, before both caught fire and caused $25,000 damage, equaling about $270,000 in

2002 currency. Half of that was safely insured, and another case shop was built upon the

same site. From here, the Waterbury Clock Company kept getting larger and more

flushed with employees. In 1867, the first known catalogue of Waterbury clocks was

released by the New York Sales Agency. Waterbury clocks occupied only a small

fraction of the myriad of companies represented by the catalogue but that was soon to

change. The company continued to grow and by 1875, had opened several offices in

Chicago and San Francisco. By 1881, their own catalogue contained 94 of their own

clocks on 122 pages. Ten years later they had grown to a full 175 pages offering 304

models of their own design.

1

Page 5

Until this point, Waterbury had been offering chiefly commonplace clocks. Their fame

was truly made, however, when Waterbury, in 1892, began to build watches for the

Ingersoll Company, who sold them as dollar watch alternatives to the expensive watches

of the time. These became known as Ingersoll Watches, and were produced by an

offshoot of the Waterbury Clock Company, the Waterbury Watch Company. This

became an extremely profitable venture for both parties, yet when Ingersoll went

bankrupt due to several mistakes involving the purchase of “defunct” watch companies,

Waterbury lost its most valuable customer. During the time in which Waterbury was

producing the Ingersoll-Waterbury watch, clock production held, but did not increase

much. A few new clocks were added, but their catalogue was very much standard as it

always had been.

Waterbury continued on its way, eventually creating the “Mickey Mouse clock” and the

“Timex”, though by 1942 it had already ceased to be its own corporation, having been

bought out by Norwegian investors and moved to Middlebury, CT. Now, the Waterbury

Clock Company lives on in its legacy of vintage antique timepieces and in the Timex

Corporation which it birthed.

As for a brief history of the Waterbury Regulator No. 61 and its long

ancestry of precision regulators...

The Waterbury Regulator No. 61 was produced during Waterbury’s business peak from

1903 to 1917 because of demand that stemmed greatly from the advancements made in

the railroad. With the railroad came schedules, and people needed to know what the time

was to a greater accuracy than simply night or day. As such, precision regulators were

found chiefly in train stations, banks, and hotels, yet demand grew for smaller timepieces,

such as precision watches, in large cities. In addition, people began to move to those

cities where time became important in one’s work place instead of generalized on one’s

farm. As the world became more modernized and in effect, smaller, time became a

necessity not only to keep trains from colliding and economy running, but also for the

common man who simply wanted the time of day.

Precision movements before the railroad, however, existed primarily as scientific

advancements quite beyond the public’s field of use. The early clock began with but one

hand, the hour hand, which showed the time within about 30 minutes the time of day. As

people became more and more interested in keeping track of time, a minute hand was

added allowing ease of time measurement to within approximately 30 seconds. Precision

clocks were those with a second hand, which measured to the second and finer,

dependant upon the clock. Today, in such a time-based world, the common clock has a

minute hand and most often a second hand. In 1903, The Waterbury Regulator No. 61

was among those clocks with a second hand and probably considered nearly extraneous

in its accuracy. At that time, no one needed to know the time to within a second, except

perhaps in the railroad’s case and those persons servicing the precision watches.

Presently, the Waterbury Regulator No. 61 remains a superbly accurate clock even by

today’s standards of a precision movement.

2

Page 6

The Process

To Begin – The Take Down

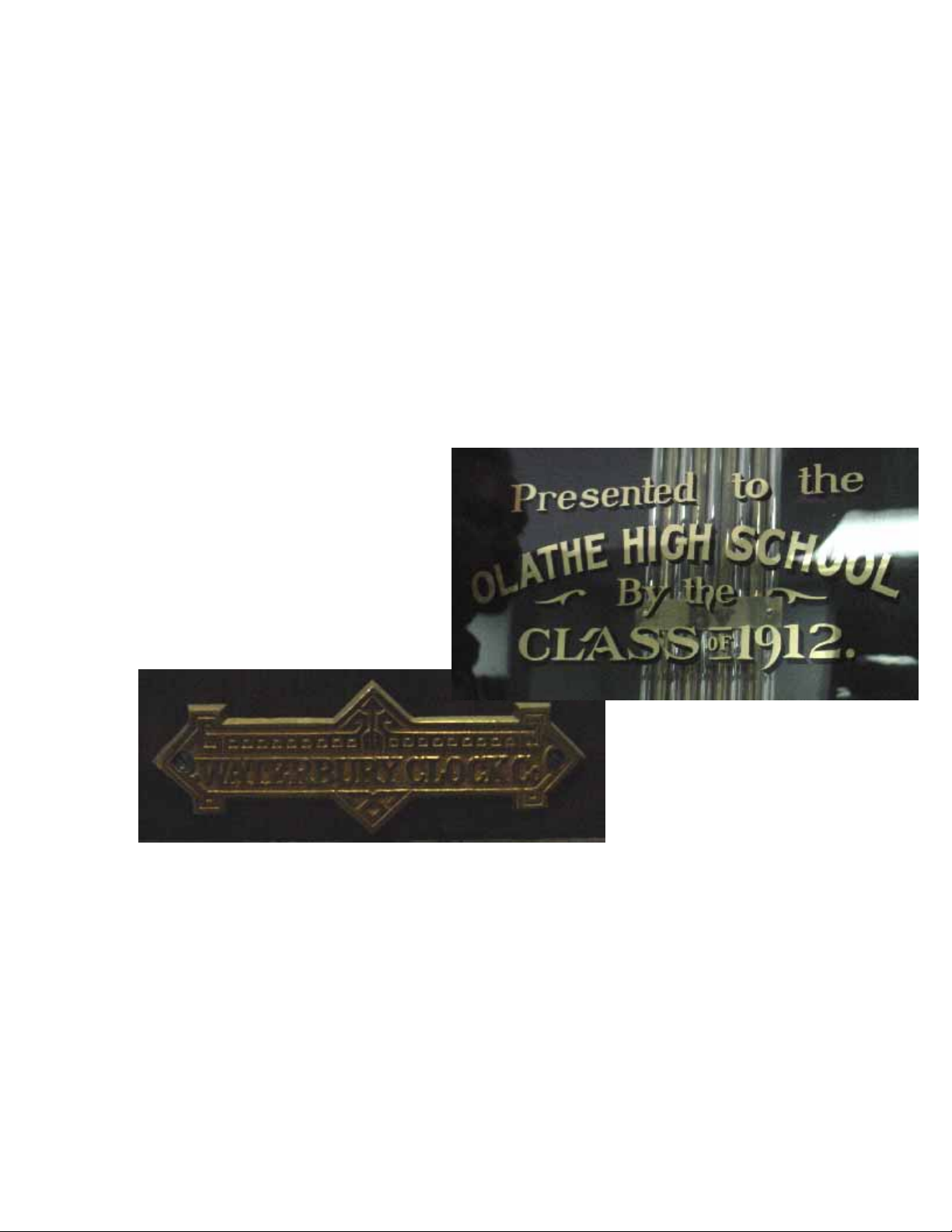

The first day of work began on the morning of February 27, 2002; ninety years after the

presentation of the clock to the school by the class of 1912. We [David LaBounty CMC,

FBHI and Andrew LaBounty, Apprentice] received permission from Asst. Principal Mr.

Carmody to remove the clock’s movement, dial, weight, and pendulum from the case and

take it to our shop (then operating from home) for restoration. First, the pendulum was

removed and placed to the side. Next, the weight was detached and placed with the

pendulum. Finally, to take the clock movement and dial out of the case, it was necessary

to loosen the seat board screws that held the metal box encasing the movement. After

doing so, the metal box and movement, attached with the dial, were easily transported as

a unit. The work had begun that would take place everyday during seventh hour for

about a month.

From Tran Duy Ly’s

“Waterbury” Reference

Book

3

Page 7

At the Shop – Cleaning it up

The first step in restoring the movement was obviously to remove it from both the dial

and the metal box that encased it. To achieve this, the taper pins that held the dial to the

box and the screws affixing the movement to the box were all removed. In addition, the

hands were removed to take the dial off. After the

movement was taken out, several observations

were made concerning the general state of the

movement. It had indeed, been restored

previously. It was obvious that it had been bushed

(discussed later) in some places that were not

entirely necessary and not bushed in places where

it would have been more helpful. It was also

painfully obvious why the piece kept bad time, or

more likely no time. Several pivot holes were

Removing the Dial Pins

worn, the pendulum was badly adjusted with the

beat adjuster set far to the left, the escapement had

far too much entrance drop and little to no exit drop, and it was probably set up

incorrectly. All of the problems with performance are easily taken care of with no cost to

the school, yet there is an aesthetic scar on the

escape pallet arm placed there purposely by an

unknown repairman. Unfortunately, it serves no

cause for good or ill but to mar the otherwise

gorgeous workings of a Waterbury Regulator 61,

and it is irreparable. Apparently, someone took

a punch and a hammer and beat consistently 16

times on the edge of the steel pallet arms.

Again, it is

senseless, useless,

and obscene, so of

course I’d like to point it out as a previous injury and not a

recent one. Everything else seems to be in order and original,

making for a beautiful timepiece. Having made these

observations and taken pictures, the movement was then off

to the ultrasonics to be cleaned. An ultrasonic tank is used

because the ultrasonics agitate the liquid, causing small implosions, and knock off more

dirt and grease than is possible any other way. First the

movement was placed in an ultrasonic tank filled with

ammoniated clock cleaning solution to remove the grease

and dirt, as well as to brighten the brass. Then, it was

rinsed in water to take off the ammonia solution and

placed in an ultrasonic rinse solution of 50% xylene, 50%

mineral spirits to bond with and remove the water.

Finally, it was put in the dryer for several minutes at

o

about 125

F to evaporate the rinse solution. When it was

finished, it was photographed again and ready to be

disassembled.

4

Page 8

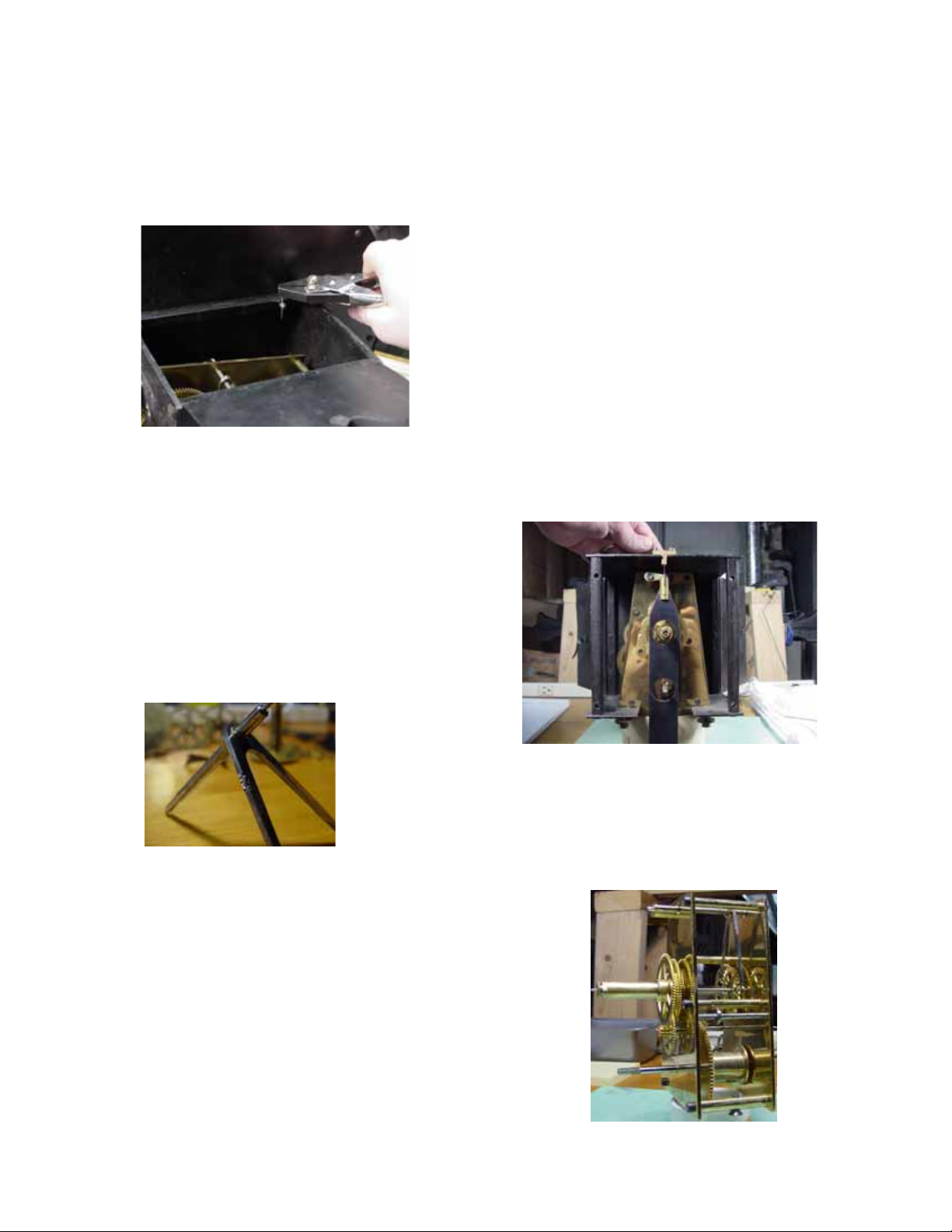

On Paper – Making a Map

Before I could take the movement entirely apart, it had to be drawn so I would be able to

put it together again with the gears in their proper places.

To do this, I drew circles and numbered them in a

hierarchy to display the order in which they went, then

drew each individual gear to show “which way was up”.

Since there are two plates, it is very easy to put a gear’s

opposite end in the wrong hole, so not only did I have to

know their order, but also the relationship of their pinions

to wheels, which end went “down”, and the

characteristics of each individual gear. The difference

between pinions and gears should be explained. A wheel

is, of course, a toothed disk that drives other gears. A

pinion is a smaller portion of the gear, either in the shape

of a lantern or a cut, smaller wheel that mates with the

wheel of an adjacent gear. The pinion is the driven and

My Drawing (see attachment C)

the wheel is the driver. Another difference is that pinions

have fewer “teeth” than a wheel, but they’re called

“leaves” instead. In fact, if a wheel has less than 20 teeth, it is considered a pinion, and

the teeth are then called leaves. Both a wheel

and a pinion together on a steel shaft is

representative of a gear. At any rate, I had to

know where the wheels and pinions were

positioned on each gear, and where each gear

was positioned between the plates. In

addition to drawing the

movement, I also examined

it for any damage I hadn’t

already noticed. One thing

that made itself apparent was

the warped condition of the hand nut. Placing it in a hole on an

otherwise flat block, I pounded it gently flat with a brass hammer so as not to mar the

surface. Thus, I straightened the hand nut.

5

Page 9

Taking it Apart – And Determining Beats per Hour

Finally, real work could begin with the gears themselves outside of the movement. To

take the movement apart was a simple matter of taking out five screws and pulling the

front plate straight upward to avoid bending any

pivots or shafts. This done, the gears were exposed

and could be removed and replaced as needed

according to the drawing which showed which pivot

hole was which. Once it was apart, I had to count

teeth to determine the beats per hour (BPH) of this

particular clock. The BPH of a clock is the number

of “tick-tocks” a clock makes in one hour. If the

clock isn’t set to its specific BPH, it doesn’t keep

time. Some BPHs can be looked up in a book, but

most must be calculated using a “gear train calculation”. To make a gear train

calculation, one only uses the gears in-between the minute hand and the escapement

(from which issues forth the “tick-tock” noise). You want to find the number of “ticktocks” in an hour caused by the passing of escape teeth through the escape pallets, and

the only constant you know is the minute hand, which invariably makes one revolution in

an hour. With the minute hand as your beginning point and the escapement as the ending

point, you simply engage in a series of conversions from wheel teeth to pinion leaves

until you find the number of teeth on the escapement that pass a single point in exactly

one hour. The Waterbury Regulator No. 61 happens to have a “seconds pendulum”

which I knew from the beginning meant that it had to have 60 beats in one minute times

60 minutes in one hour for a total of 3600 BPH. Happily, my gear train calculations

reflected that exactly, as shown below:

80

___

12

x

72

___

x (30 x 2) = 3600 BPH

8

There are 80 teeth on the center wheel (which drives the minute hand), 12 leaves on the

pinion that mates with the center wheel, 72 teeth on the “3rd wheel” (that shares the shaft

with the above pinion), eight leaves on the escape pinion that mates with the “3

rd

wheel”,

and 30 teeth on the escape wheel. The tooth count of the escape wheel is multiplied

times two due to the fact that there are two noises, tick and tock, that occur when each

escape tooth enters and exits the pallets (for a total of two beats per tooth).

6

Page 10

Polishing Pivots – The Dreary Part

Next, it was time to polish the bearing surfaces of the clock, called the pivots. The pivots

are the ends of the gears that turn in the plate, and if they’re not polished, the clock will

be sluggish and possibly stop. This is mostly due to the dirt that

will be trapped in the scratches on the pivot plus the high amount

of friction caused by the rough surface. In addition, the pivot

holes will wear more quickly into oblong holes causing gears to

mate improperly and perhaps come into a locking situation.

Needless to say, the pivots must be polished and clean before the

clock can achieve maximum efficiency, so that is what I set out to

do. To accomplish this, I used a tool

A Jeweler’s Lathe

called a jeweler’s lathe, which holds the

shaft of the gear and turns it on its axis so that the pivot is spun

and can then be polished using a file, burnisher, and other tools.

First, the file is used to dress the surface uniformly, and remove

any deep gouges. Next, a cutting burnisher is used to lessen the

scratches further, and acts as a very smooth file and technically

File – The First Step

isn’t really a burnisher at all. Finally, a true burnisher is used.

A burnisher is a piece of metal, usually very hard, that has very

small consistent ridges on the surface whose design is to “grab” the steel of the pivot and

stretch it to create a perfect polish. This must be done at high

speeds and with a good amount of pressure, yet not so much of

either to burn the steel. When done correctly, burnishing

produces not only a beautiful shine upon the pivot, but also

hardens the surface as the steel is worked and compressed.

There are several things to keep in mind when polishing a pivot

as well: it must be flat, straight, and the shoulder must be

perpendicular and polished as well. If it

isn’t flat, it could trap foreign materials in

File from above

the pivot hole and score both the pivot and

the hole. To straighten a pivot, one must heat it gently then chuck it

up in the lathe. This done, it can be carefully straightened until the

whole gear turns true upon the pivot. Once straightened it may be

polished. This entire process is the typical way to straighten and

A burnisher

polish a pivot, and must be repeated for all the pivots, two to each

gear. In all, I had to polish eight pivots this way, which is a

minimum number for most clocks, since many contain upwards of twenty pivots.

Fortunately for my patience, the Waterbury Regulators are time only, and have no extra

gears to drive a chime or strike. In regards to this clock, there were no terribly deep

gouges in any of the gears, however the main wheel had noticeable scratches on the

surface, and all of the pivots were scratched in one way or another. Since the steel was of

good hardness and quality, it was no surprise that there were no horrible gouges, but it

also made it harder to polish at times.

7

Page 11

Major Project – The Escape Wheel “Nut”

After the pivot polishing process was complete for all eight pivots, I progressed to

“bushing” the pivot holes. A bushing is a small cylinder of brass with a hole in the

middle designed to replace a worn hole. To replace a

worn hole, one uses a hand reamer (a

small handheld tool that when twisted,

can cut a hole quickly to an exact size)

to ream the original hole into a larger

one while keeping it centered and round

Hand Reamer vs.

Cutting Broach

to accommodate the bushing. The bushing is tapped into the newly

A Bushing

expanded hole using a punch and a hammer, which secures it, assuming

the hole was reamed to a size slightly smaller than the diameter of the

bushing. Now, with the bushing secured in the original pivot hole, the replacement hole

in the bushing should be centered where the original hole was. With

a cutting broach (a tool similar to the reamer, yet provides more

control and a slower cutting rate) the hole can be resized to the pivot,

which creates a round, true, and centered hole where the old, worn

hole was. With this process in mind, I checked the gears by feeling

their tightness when placed in their pivot holes. If the gears were too

loose and “flopped” around too much, I put them back in the plate

That ol’ Hand Nut Again

to signify that those holes were worn or too loose, and needed

bushing. When I came around to the escape wheel, however, I found that it became

impossible to continue with out first repairing that pseudo

hand nut that acts as the pivot hole for the escape wheel.

The threads were bad, and the nut couldn’t be screwed on

tightly or far enough to determine how loose the escape

wheel pivot actually was, so it had to be fixed immediately.

The first step to repairing the threads was to discover what

the pitch, or number of threads per inch, was for that

particular screw and the diameter of the threads. With this in

Pitch Finder

mind, we consulted the Machinery’s

Handbook for the proper tap and die set

to use in order to create the new threads. We determined the diameter

to be nearly the equivalent of a size 6 die, with a pitch of 40 threads

per inch. This meant that the optimum set to use was the 6-40 die, but

the diameter of the screw was still slightly too small for the hole it

screwed into. This forced us to use a split round die, which allowed

Split, Round 6-40 Die

us to create an oversized 6-40. After discovering the correct die and

the diameter of the new screw, I chose a piece of round brass stock and filed it down to

the correct diameter. Then, I took the oversized 6-40 die and essentially screwed the

piece of brass into the die. When it was unscrewed again, the die had cut threads into the

brass. Now, with the new threads on the end of the brass, I set about cutting them off of

the rod so I could use them in the nut. I cut the threads off successfully, so we were left

with the old nut and new threads. First, I had to cut off the old threads from the nut.

Then, we drilled a hole as though we were bushing the nut itself. Having done this, I

8

Page 12

inserted the smaller end of the threads (which I filed down) into the rim of brass that was

the head of the nut and peened the end down by hammering it flat so that it wouldn’t slip

when it was screwed in. After the new threads were stuck tight in the rim, I drilled a hole

through them, creating a threaded bushing, and eventually sized that hole to fit the escape

wheel pivot. When I drilled the hole, I chucked up on the threads

instead of the rim so that I could drill the hole centered in the

threads. This was important since the escape wheel turned in that

hole and it was necessary that it be in the center of the threads so

the escape wheel wouldn’t wobble.

Before I sized the hole to the pivot, I

polished the head of the mostly original

Shaving off the end for

End-Shake

nut and countersunk it to give the

impression that it was made entirely out

of one piece of brass, as the original nut was. Magnificently, it

looks entirely original, and I’m very proud of it! We actually

had to solder the threads to the hole, because they kept falling

out during the sizing process, but it’s not visible and makes the

Repaired Hand Nut

nut a good deal stronger but softens the brass somewhat. After

sizing the hole, we had to shave off the end of the nut so it would screw down tightly and

completely and still allow the escape wheel some end shake, or space between the plate

and the shoulder of the pivot. Now, the escape wheel can move freely and securely, as

opposed to being sloppy and inaccurate as it undoubtedly was with such a bad nut. In

passing, there was another screw I had to create so that the plates

would screw down correctly and fully. This was done in a very

similar fashion, except it was done

with steel and not brass. My goal

was to make a longer screw to

bypass a stripped upper portion of

one of the pillar posts. With skill

and care, I fashioned a screw out of a piece of O-1 tool steel, polished it, and blued it with

gentle heating. According to the Machinery’s Handbook, heating the steel gently, creates

an oxidization of the steel resulting in a colored coating that not only matches the other

screws on the clock, but also acts as a rust preventative. To my equal pride and dismay,

it looks noticeably newer, shinier, and better polished than the original screws. The old

screw is included with the clock upon set-up in the school.

Bushing – For Real Now

With the escape wheel secured and happy, I was ready to do standard bushings as

planned. After sizing the new pivot holes of two gears, I countersunk them to the plate.

This means I created a “bowl” with the pivot hole at its base, as shown in the picture of

the repaired hand nut. This is done so that pivots better receive oil, but it also hides the

bushing since the plate and bushing are both on the same plane after countersinking, to

the effect that they’re indistinguishable from each other. It only serves to look more

professional when a movement appears entirely original and unaltered. I countersunk not

only my own bushings, but also the bushings that were inserted by other repairmen at

various times.

9

Page 13

Polishing the Pivot Holes – Everything’s so Shiny!

Since most of the hard part was completed, I was happy to move on to polishing pivot

holes, as it meant the pivots would soon be in them and turning again. Unfortunately, the

pivot holes take a little while to clean, though they go much faster if the bushings are

done right. To polish a pivot hole, one takes a smooth broach just like the cutting broach

except not faceted, and “burnishes” the inside of

pivot holes with oil as though one were burnishing a

pivot. With enough pressure and rotation of the hand,

Smooth Broach

the holes will look as good as the pivots, but it gets

tiring to do all ten holes (which now include the two

escape pallet pivots). Actually, it’s only hard the first time one does it, and only if the

bushings are so loose that they come out during the polishing process. This is especially

unfortunate because then one must go back and rebush it. I was terribly glad when none

of mine fell out, and neither did any of the previously bushed holes. Having done this

with oil on the smooth broach, there was now oil in the holes. To remove it, I used the

xylene/mineral spirits mixture to rinse the movement and then used toothpicks to clean

out any extra contamination from the holes. If contamination is present, it could react

with the lubricating oils used later and cause the clock parts to become sticky and stop.

Toothpick cleaning averted a disaster, however, and in no time at all, the holes were

bushed and polished and the gears were free to be put back between the plates!

The Escapement – Theory, Practice, and Math

At this point, with the gears in their rightful places within the clock, it was time to

calibrate the time keeping by adjusting the escape pallets. Some necessary terms are:

entrance/exit pallet, entrance/exit drop, entrance/exit lock, and the lift/lock face of each

pallet. The entrance pallet is the side of the pallets that allows teeth to enter between the

pallets, and the exit

obviously releases them.

Entrance drop is defined by

the amount of distance the

escape wheel rotates after

being let off of the entrance

pallet. It is easily visible as

the distance between a tooth

and the inside edge of the

entrance pallet as lock

occurs. Conversely, the exit

drop is the distance the

escape wheel rotates after

A labeled diagram of a Graham deadbeat escapement

being let off of the exit pallet

and is visible as the distance

between a tooth and the outside edge of the exit pallet as lock occurs. The entrance/exit

lock is the amount of pallet face that “catches” the escape wheel tooth when stopping the

10

Page 14

rotation of the escape wheel. The lock face is the portion of the pallet that stops an

escape tooth. There are also lift angles on the ends of the pallets (the lift faces) that drive

the pendulum sufficiently to keep the clock running, and are subject to wear (as are the

lock faces). My first goal was to measure the lift angles. To do so, I measured the pallets

from the center of the pivot to the mid-point of the pallet thickness. Dividing this by two

gave a value of half of the length of the pallet arm. Knowing that measurement, I drew a

circle with an equal radius and drew a tangent line on that circle. This represented 2o of

lift when the pivot of the escape pallets was placed through the center of the circle and

the lift faces were lined up with the tangent line. For clocks with small, light pendulums,

2o is an optimum lift angle. The Regulator has a large, heavy pendulum, however, and

1.5 degrees is most desireable for such clocks. To draw a 1.5-degree circle, I divided the

original measurement by two to achieve one degree, and added half again to that for a

total of 1.5 degrees. After checking the pallets, I found that the lift faces were rather well

angled. I carefully filed off the wear, making sure to keep the angles as they were, then

polished the faces using a buff stick and white rouge on the “buffer polisher” machine.

Once the minimal wear was disposed of and the pallets were nice and shiny, I also filed

off some of the burrs created by the punch marks on the exit pallet arm. It looks better,

but to fully remove the punch marks would be to recreate the pallets, which is extremely

difficult. Finally, I put the escape pallets back into the clock and we checked the entrance

drop, which is always adjusted before the exit drop. We found

the entrance drop to be too large (due to the fact that material

was removed in the polishing process), so we put the pallets in a

vice and heated them gently while squeezing, being careful not

to break them. This achieved the desired effect of decreasing

the entrance drop. Having done that, we next checked exit

drop, which is adjusted by changing the distance from the

pallets to the escape wheel instead of opening or closing the pallets themselves. After

both sides had equal drop and sufficient lock (to ensure the wheel didn’t slip past or hit

the lift face), it was time to adjust beat rate and time keeping!

Beat and Rate Adjustments – Nuts and Knobs

With the movement ticking, the time had come to check the performance of the clock.

First, however, I had to set it up properly on the movement stand and adjust it to keep

time. The first thing I adjusted was the beat, or the consistency of the “tick-tocks” with

the goal of making the time between the beats equal. In other words, I wanted the escape

teeth to lock at the same relative point on each side of pendulum’s

arc. To do this, I loosened the screw where the leader attaches to

the pallet arbor, which is the part of the clock that connects the

pendulum to the escape pallets, and rotated it slightly so that it

drove the escape pallets the same distance on each side of the

pendulum’s swing. To make sure the beat was correct, I used a

Timing Machine

timing machine (also used to measure the rate). This machine

picks up the sound made by the clock and measures how much time passes between the

beats. Then it calculates the difference. After getting the beat nearly perfect,

11

Page 15

I used the finer adjustment knob nearer to

the bottom of the leader to finish the

adjustment. After setting the beat, I set

the rate, or the quickness of the tick-tocks.

This was done using the nut at the bottom

of the pendulum. I used the same timing

machine to measure how many beats the

Fine Beat Adjuster

clock made per hour, which I found above

to be 3600. I tweaked the nut until the

Rate Adjuster

measurement was just that or very close to 3600. Now, the clock was

adjusted to keep time and our job was to watch it and record how well it performed!

Refitting the Second Hand – Found in the Case

To put the second hand back on, it was first necessary to “poise” it, or balance it so that it

would not hinder the clock in any way. When we

received it, it was too heavy on one side. To poise

it, I pounded a piece of lead flat and super-glued it

to the back and bottom of the second hand to offset

the heavier “long” side. I then put it on a smooth

broach and checked its balance. Obviously, it was

imbalanced at this point, so I carefully shaved off

bits of lead first around the edges so it wouldn’t be seen,

then carefully evened it on either side until it was perfectly

Out of poise

balanced and static on the broach. After it was poised, I

colored the lead with a magic marker to disguise its

presence. Such methods as super-glue and markers can be

used on the second hand because they work well, will not

interfere with the inner workings of the movement, won’t

be seen, and are removable. Having poised the second

hand, we now had to re-affix it to the movement. To do

that, it was necessary to close the hole in the second

hand slightly with a round-head punch so that it would

stay on. Then, it was reamed open slightly with a

cutting broach until it just fit. After the hole was sized

to the escape pivot, the second hand was attached solidly

to it and works fine now. Remember that the clock

has a beat rate of 3600 beats per hour, or 60 beats

per minute. For this reason, the second hand is

directly affixed to the escape wheel since each tooth

represents one second exactly. One of the unusual

features of this clock is the fact that the escape

wheel front pivot, which has the second hand attached, comes out in

the middle of the dial, through the center of the hands. This

characteristic makes the Waterbury Regulator No 61 a “center

seconds” clock.

Perfectly Poised and Static

12

Page 16

Conclusion – And Thanks

I really enjoyed working on this lovely clock, and I’m honored to be a part of the history

begun by the esteemed Class of 1912. Olathe North truly has one of the great clocks in

existence today, and I trust it will be around for another 90 or 100 years. I would like to

thank Mrs. Dorland and Mr. Carmody for their support in allowing me to restore the

clock, and I’d also like to thank Ms. Reist for being so impressed and interested! The

next section talks about the care and maintenance of the clock, as well the procedure

taken in setting it up, if ever one should decide to relocate the clock.

13

Page 17

Care and Maintenance

This Section by:

David LaBounty, Certified Master Clockmaker AWI, Fellow BHI

Winding

This clock should be wound on a regular basis and once per week is acceptable. The

clock may run for twelve to fourteen days but it is important to avoid having the weight

settle on the bottom of the case. Damage to the escape wheel teeth could occur if all

power is off of the train (as in the weight resting on the bottom of the case) and the

pendulum continues to swing. If winding the clock before it stops is not a possibility, it

is preferable to stop the pendulum by gently touching it and bring it to rest rather than

letting the clock run down.

Great care should be taken when winding the clock to be sure none of the hands will

interfere in the winding process. This may require winding in stages to avoid the second

hand which will get in the way every 20 seconds or so. Letting the second hand come

into contact with the wind key will have the same results as letting the clock run

down…i.e. damaged escape wheel teeth.

When winding, be sure the key is completely and securely on the wind arbor before

turning the crank. Rotate the crank clockwise until the top of the weight starts to pass

behind the dial. This is fully wound and quite preferable to “cranking until it stops”

which causes the dents and dings found in the weight cap and may also cause the cable to

break. If it is necessary to pause in the winding process be careful to gently let the crank

back against a stop before letting go or removing the key.

Setting to Time

When setting the clock to time it is only possible to move the minute hand. The hour

hand is set by rotating the minute hand until the proper hour is indicated. This may be

done either forwards or backwards, being careful not to catch and drag the second hand in

the process. Never move the hour hand or the second hand! It is also advisable to

move the minute hand from close to the center of the dial rather than the tip of the hand.

This will avoid any chance of bending the hand due to accidentally catching the tip on

something.

Sometimes it is necessary to set up the clock so that it is synchronized to the second.

This may be accomplished by stopping the pendulum and then restarting it so the second

hand is synchronized with the other device.

One point of perfectionism is having the minute hand reach a minute mark at the same

instant the second hand reaches the twelve position.

14

Page 18

Rating

Rating the clock means adjusting the time keeping so the clock neither gains nor loses

time while it is running. This is done by raising or lowering the pendulum bob using the

rating nut on the bottom of the pendulum. Stop the pendulum to make all adjustments

and then gently start the pendulum swinging when done. Minimize the amount of contact

with the polished brass since the oils on a person’s hands will leave dark splotches.

Touch the edges when at all possible or use a rag over the hand. Rotating the nut to the

right speeds up the clock by raising the bob. Rotating the nut to the left slows the clock

by lowering the bob. One complete revolution of the rating nut will change the time

keeping by one minute per day. It is important to know how long the clock has run

without being reset before making any changes to the rate. If the clock is seven minutes

off in one week, it will be necessary to make one complete turn of the rating nut. If it is

seven minutes off in one month, ¼ of a turn is all that is necessary!

1 complete turn = 1 minute per day rate change

Cleaning

All cleaning of the mechanism (movement) should be done by a professional. It is

recommended to have the movement serviced every 5-7 years or sooner if the time

keeping becomes erratic. At the time of this restoration, LaPerle clock oil was used

throughout.

The glass may be cleaned on the outside with the usual care given to prevent soaking the

wood. The inside of the lower glass shouldn’t be cleaned unless absolutely necessary.

The gold leaf lettering is very delicate and could be wiped away with nothing more than

Windex. If it is necessary to clean the lower inside glass, spray the cleaning solution on a

cloth rather than directly on the glass and avoid the lettering during the cleaning process.

The upper glass may be cleaned on the inside using the same care as the outside with the

exception that time be given to allow the fumes to dissipate so they are not trapped in the

case with the movement. Ammonia will break down the oils causing them to fail.

15

Page 19

The wood case may be dusted with a slightly damp cloth and it is generally not advisable

to apply a dusting agent. Wax buildup and dirt will darken the case with years of use and

could destroy the original finish.

Moving the Clock

At some point it may become necessary to relocate the clock. This may be done safely if

certain measures are taken.

1. Allow the clock to run until the weight is well down in the case but not touching the

bottom.

2. Remove the pendulum by: Stop the pendulum from

swinging; remove the screw at the top; get a good grip

(the pendulum is pretty heavy); with a finger on the

leader, gently lift the pendulum up and away (it is held

on with a pin); replace the screw in the leader to prevent

it from being lost.

3. Remove the weight by lifting

up on the weight cover cap and

then unhooking the weight from

the cable.

4. Remove the movement from the case by loosening the two seat board screws located

behind the dial and under the movement. The movement will slide off of the seat board.

Once 1-4 have been accomplished successfully, the clock case may be moved like a nice

piece of furniture.

Setup After Moving

Stability of the case is the most important part of setting up the

clock. The case must be back against the wall in such a manner

that the top touches on both sides. A good test is to push against

the top to see if there is any give. If there is, it may be necessary

16

Page 20

to place shims under the front of

the clock to force it to lean back

against the wall. If this isn’t

done, the clock may sway or

worse yet, fall over!

The case must also be leveled

side-to-side. Place a bubble

level in the bottom of the case

and shim one side or the other

until the case is leveled.

The case must be back against the wall and level side-to-side before the movement is

reinstalled.

Reinstall the movement, weight, and pendulum using the instructions for “Moving the

Clock” as a guide.

Setting the Beat

One final adjustment will be necessary once the clock has

been relocated and properly set up. The clock must “ticktock” evenly; like a metronome. This is accomplished by

turning the knob on the beat adjuster small amounts (while

the pendulum is stopped) until the tick and tock occur on

equal sides of the center of the pendulum’s swing. The

adjuster is located just behind and below the dial, where the

pendulum attaches to the leader.

17

Page 21

Bibliography

French Clocks: The World Over, Part One, by Tardy. Paris, 1949. pp. 10-30

Machinery’s Handbook 24

Robert E. Green. New York: Industrial Press Inc., 1992. pp. 1706-1707

Seth Thomas Clocks and Movements

Company, 1996. pp. 20-21

Waterbury Clocks

, by Tran Duy Ly. Virginia: Arlington Book Company, 1989.

pp. 13-20, pp. 289

th

Edition, by Oberg, Jones, Horton, Ryffel. Edited by

, by Tran Duy Ly. Virginia: Arlington Book

18

Page 22

Attachment A

Repair Itemization:

• Polish eight pivots

• Clean four shafts

• Straighten six escape wheel teeth

• Draw (stretch) escape wheel teeth

• Tip (machine) escape wheel teeth to true escape wheel

• Straighten two pivots

• Replace threads on hand nut

• Install three bushings

• Make one new movement screw (extra long and blued to match)

• Realign (true) pillar posts

• Close escape pallets to decrease entrance drop

• Poise second hand

• Tighten second hand on front escape wheel shaft

19

Page 23

Attachment B

Tooth Count:

• Hour Pipe = 80 teeth

• Minute Wheel = 54 teeth

• Minute Wheel Pinion = 10 leaves

• Hour Wheel = 80 teeth

• Cannon Pinion = 36 leaves

• Main Wheel = 84 teeth

• Second Wheel = 80 teeth

• Second Wheel Pinion = 8 leaves

• Third Wheel = 72 teeth

• Third Wheel Cut Pinion = 12 leaves

• Third Wheel Lantern Pinion = 8 leaves

• Escape Wheel = 30 teeth

• Escape Wheel Pinion = 8 leaves

20

Page 24

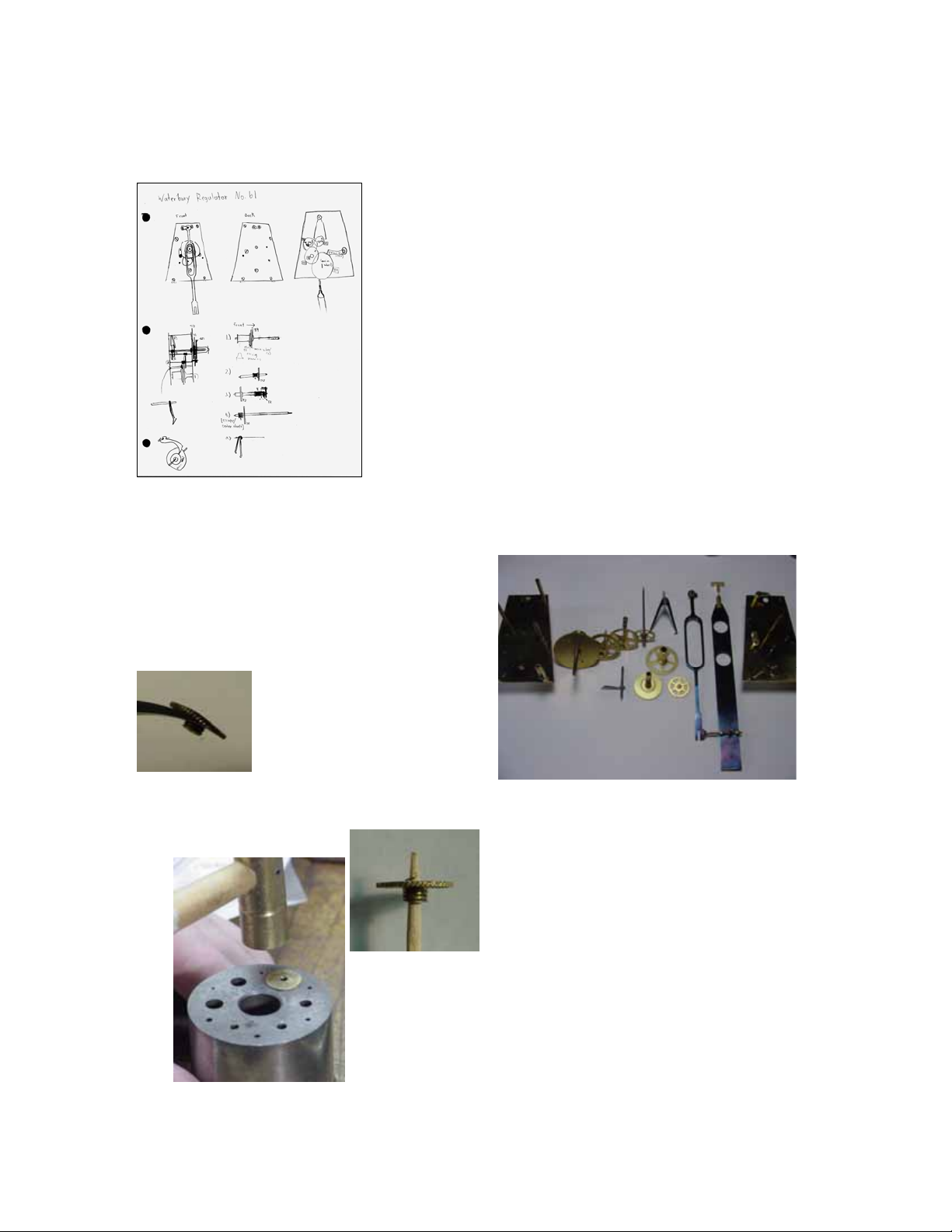

Attachment C

Original Sketch

21

Page 25

Attachment D

Other Sketches

22

Page 26

23

Loading...

Loading...